Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

2Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia

Email: desheva@mail.ru

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9794-3520

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

2Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5130-5000

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2156-1635

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3342-5828

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7495-446X

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-0045-4886

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9999-089X

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

2Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1963-0333

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9045-0683

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

2Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-8530-8059

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-1680-399X

Affiliation:

1Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine”, 197022 Saint Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2801-1508

Explor Immunol. 2025;5:1003230 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2025.1003230

Received: May 22, 2025 Accepted: November 12, 2025 Published: November 28, 2025

Academic Editor: Vladimir N. Uversky, University of South Florida, USA

The article belongs to the special issue Old and New Paradigms in Viral Vaccinology

Aim: Develop A/H1N1pdm09-based live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIVs) presenting chimeric hemagglutinin (HA) fused to fragments of Streptococcus pneumoniae (PspA, Spr1875) or S. agalactiae (ScaAB) to elicit combined anti-influenza and anti-bacterial immunity.

Methods: Recombinant LAIVs were generated by reverse genetics. Replicative fitness was measured in embryonated chicken eggs (CE; log10 EID50/0.1 mL, n = 5 per delution) and MDCK cells (log10 TCID50/mL, n = 5). BALB/c mice (n = 20 per group; serology n = 6 per group; lung titers n = 5 per group) received intranasal 106 EID50. Systemic IgG and mucosal IgA to influenza and to the recombinant pneumococcal peptide were quantified by ELISA (GMT ± SD). Early cytokine responses were profiled in THP-1 cells.

Results: All recombinant strains replicated in CE at 33°C but were temperature-sensitive at 39°C. H1-ScaAB retained relatively high replication and exhibited a cold-adapted phenotype despite a large N-terminal insert. In MDCK cells, H1-PspA showed significantly reduced replication compared with the parental LAIV. In mouse lungs, replication on day 3 post-immunization was significantly lower for H1-ScaAB and H1-PspA compared with the parental LAIV strain (p < 0.05). The parental LAIV induced robust systemic anti-influenza IgG and, uniquely for H1-ScaAB, significant mucosal anti-influenza IgA (p < 0.05). H1-Spr generated stronger antibody responses to the inserted pneumococcal peptide (p < 0.05). THP-1 assays revealed construct-specific cytokine patterns (unmodified H1N1: highest IFN-α; H1-Spr: elevated IL-6; H1-ScaAB: greatest MCP-1).

Conclusions: Multiple A/H1N1pdm09-based recombinant LAIVs with chimeric HA can replicate in eggs and murine respiratory tract and induce dual influenza/pneumococcal antigen responses. Expanded biophysical validation, functional antibody assays and challenge studies are needed to optimize insert design without compromising viral fitness.

Infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the most common causes of secondary bacterial infections following influenza. In particular, it can lead to sepsis, otitis, meningitis, and pneumonia [1]. Approximately 30–40% of patients hospitalized with influenza develop additional bacterial infections [2]. Pneumococcal infection can be fatal, especially in individuals with weakened immune systems. Vulnerable groups include people with chronic diseases, patients after splenectomy, transplant recipients, pregnant women, children under five years of age, and adults over 65 years [3]. Therefore, preventive measures against secondary bacterial infections following influenza are of great importance.

A number of studies in mice have shown that increased pneumococcal adhesion occurs not only during coinfection with influenza viruses but also after recovery from influenza [4, 5]. This may be due to influenza virus-induced damage to the respiratory epithelium, which disrupts mucociliary clearance and enhances bacterial adhesion [4]. In addition, influenza virus suppresses innate immunity, promoting uncontrolled growth of S. pneumoniae [1]. It also activates receptors required for bacterial attachment [6, 7].

Another mechanism involves the action of viral neuraminidase (NA) on the respiratory epithelium. NA cleaves sialic acids, thereby allowing pneumococci to adhere to the trachea and spread to the lungs [8]. Furthermore, influenza virus infection complicated by secondary S. pneumoniae infection is associated with increased production of neutrophil extracellular traps, which can exert cytopathic effects in the lungs [9].

Currently, vaccines against S. pneumoniae based on bacterial cell wall polysaccharides are widely used and have prevented numerous deaths from bacterial infection [10]. However, studies indicate that the proportion of serotypes not included in these vaccines is gradually increasing [11]. The most pronounced rise in non-vaccine pneumococcal serotypes has been observed among adults aged 45 years and older, particularly those over 65 years, who also exhibit the highest incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease [11, 12]. These trends have prompted researchers to focus on protein-based bacterial antigens—such as virulent surface proteins, enzymes, and adhesins—which represent more conserved and immunogenic targets [13, 14].

For the prevention of respiratory tract infections, mucosal vaccines that induce both systemic and local immune responses are of particular importance [15, 16]. Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) strains represent a promising platform for delivering bacterial antigens into the host [17]. Advantages of LAIV strains as vectors include a needle-free mucosal route of administration, the ability to modify antigenic properties to overcome pre-existing vector immunity, the large-scale annual production of influenza vaccines, the availability of efficient reverse genetics systems, and an RNA genome that strongly induces innate immunity and ensures safety due to its inability to integrate into the host genome [18]. The main limitations of the influenza vector include its low genome capacity (less than 1.5 kb) and certain safety considerations.

Attenuated LAIV viruses replicate efficiently at 25–33°C (in the upper respiratory tract and nasopharynx) but poorly at 37–39°C (in the lower respiratory tract and lungs). The genetic basis of cold adaptation lies in mutations within several internal genes of the Master Donor Strains (MDS). By genetic reassortment, the two genes encoding hemagglutinin (HA) and NA are replaced with those from circulating influenza strains to comply with annual WHO recommendations [19].

Previously, a recombinant LAIV strain of the A/H1N1pdm09 subtype expressing a fragment of the surface protein S. pneumoniae Spr1875 was shown to stimulate the production of virus-specific serum antibodies and to induce an increase in IgG against the recombinant pneumococcal peptide [20].

In the present study, recombinant LAIV strains of the A/H1N1pdm09 subtype expressing fragments of several conserved S. pneumoniae surface proteins, such as Spr1875 and PspA, as well as an immunogenic fragment of the ScaAB lipoprotein from group B streptococcus (S. agalactiae), were investigated. The S. pneumoniae surface protein Spr1875 (which contains a LysM domain) is a pneumococcal virulence factor. It has been shown that Spr1875 participates in the interaction of pneumococci with microglial cells, possibly contributing to the development of pneumococcal meningitis [13]. Spr1875 exhibits immunogenic properties and is expressed on the surface of multiple strains belonging to different serotypes [21]. The Spr1875 fragment used in this study corresponds to 69 amino acids (residues 94–162 in the original protein) and lacks the C-terminal region containing putative immunodominant epitopes that are not associated with immunoprotection [21]. PspA is a surface choline-binding protein that binds human lactoferrin and inhibits complement activation both in vivo and in vitro, thereby reducing opsonization and bacterial clearance by the host immune system [22]. The fragment corresponding to residues 160–262 of the original PspA protein belongs to the central α-helical domain, which plays a key role in immunogenicity and interaction with innate immunity factors [14, 23].

The ScaAB protein, found in S. agalactiae, belongs to the family of metal transporter proteins and is a homologue of the highly immunogenic PsaA protein of S. pneumoniae, which protects mice against influenza and pneumococcal infections upon immunization [24].

The aim of this study was to investigate the molecular structure and biological properties of recombinant influenza A/H1N1pdm09 vaccine viruses expressing fragments of S. pneumoniae surface proteins or the S. agalactiae lipoprotein fused via a flexible linker to the viral surface protein HA.

All animal procedures were conducted at the vivarium of the Institute of Experimental Medicine in full compliance with GOST 33216–2014 “Rules for working with laboratory rodents and rabbits.” The study was approved by the Local Committee on Ethics of Animal Care and Use at the Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine,” St. Petersburg (protocol No. 1/21, dated January 28, 2021). The study also complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Recombinant influenza virus strains were generated by reverse genetics using the 8-plasmid system as described previously [25]. The backbone virus was based on the attenuation donor strain A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) carrying the HA and NA surface antigens from A/South Africa/3626/13 (H1N1)pdm09. The HA gene was modified to express antigenic regions of the Spr1875, PspA, or ScaAB proteins.

The LAIV strain A/17/South Africa/2013/01 (H1N1)pdm09, identical in genome composition but containing an unmodified HA gene, was used as the control. The genome compositions of all vaccine strains are shown in Table 1.

Genome composition of vaccine strains.

| Vaccine strain | HA gene origin | NA gene origin | Internal genes origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1N1 | A/South Africa/3626/13 (H1N1)pdm09 | A/South Africa/3626/13 (H1N1)pdm09 | A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) |

| H1-Spr | H1-Spr-69 | A/South Africa/3626/13 (H1N1)pdm09 | A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) |

| H1-ScaAB | H1-ScaAB-202 | A/South Africa/3626/13 (H1N1)pdm09 | A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) |

| H1-PspA | H1-PspA-103 | A/South Africa/3626/13 (H1N1)pdm09 | A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) |

The viruses were obtained from the collection of the A.A. Smorodintsev Virology Department of the Institute of Experimental Medicine, St. Petersburg, Russia, and propagated in embryonated chicken eggs (CE).

Sequencing of the modified HA regions was performed using an automated capillary sequencer ABI Prism 3130xl (Applied Biosystems, USA) and the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit v3.1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Viral RNA was isolated using the MagJET™ Viral DNA and RNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Amplification of gene fragments prior to sequencing was performed using the SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR System with Platinum Taq (Invitrogen, USA) and the primers listed in Table 2. Primers were synthesized by (Alcor Bio, Russia).

Primers used in the study of bacterial fragments PspA, Spr, ScaAB.

| Primer (position, orientation) | Sequence (5'→3') | Fragment with insert (bp) | HA fragment only (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| F18 (Forward) | GCAACAAAAATGAAGGCAATACTA | PspA: 537;Spr: 429;ScaAB: 825 | 183 |

| R174 (Reverse) | TAGTTTCCCGTTATGCTTGTC | PspA: 537;Spr: 429;ScaAB: 825 | 183 |

PCR products were purified from agarose gels using a DNA purification kit (Diaem, Moscow, Russia).

Multiple alignment of nucleotide and amino acid sequences was performed using UGENE software (Unipro, Russia) [26].

Spatial modeling of the HA structure was carried out using AlphaFold Server (AlphaFold3) with homology modeling algorithms. Visualization of the resulting models was performed in Mol* Viewer [27, 28].

Potential N-linked glycosylation sequons were predicted with NetNGlyc, and per-site solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) was evaluated using GetArea [29, 30]. NetNGlyc sites with a jury score ≥ 6/9 were marked as sequence-predicted; sites with strong NetNGlyc support (jury ≥ 8/9) and relative exposure ≥ 60–70% were considered likely to be glycosylated in the modeled conformation.

To determine infectious activity, tenfold serial dilutions of virus stocks were inoculated into 10-day-old embryonated CE. Eggs were incubated at 33°C (optimal), 25°C (suboptimal), or 38–40°C (elevated) for 48 h (33–40°C) or 120 h (25°C). The 50% embryonic infectious dose (EID50) was calculated using the Reed–Muench method and expressed as log10 EID50/0.1 mL [31].

For each dilution, five eggs were used (n = 5 per dilution), and titrations were performed in three independent experiments.

Viruses were classified as temperature-sensitive (ts+) if the titer at 39°C was ≤ 5.0 log10 EID50/0.1 mL and lower than the corresponding titer at 33°C.

They were classified as cold-adapted (ca+) if the difference between titers at 33°C and 25°C did not exceed 3.0 log10 EID50/0.1 mL.

Virus replication in MDCK II cells (ATCC CCL-34) was determined by endpoint titration in 96-well plates seeded at 5 × 104 cells per well. When monolayers reached approximately 90% confluence, the wells were washed and inoculated with 25 µL of ten-fold virus dilutions (4–6 wells per dilution). After 1 h of virus adsorption, the inoculum was removed, and 150 µL of maintenance medium containing 1 µg/mL TPCK-trypsin was added. Cells were incubated at 33°C with 5% CO2 for 72 h, after which viral replication was assessed by hemagglutination of the supernatant. Infectious titers were calculated using the Reed–Muench method and expressed as log10 TCID50/mL [31]. MDCK titrations were performed with 4–6 replicate wells per dilution in each independent experiment, and three independent experiments were carried out in total. All titrations were conducted at 33°C to evaluate in vitro replication competence and were not used for determining ts/ca phenotypes.

Female BALB/c mice aged 6–8 weeks (20 animals per group) were immunized intranasally with H1N1, H1-ScaAB, H1-PspA, or H1-Spr strains at a dose of 106 EID50 in a 50 μL volume. Control animals received the same volume of PBS.

Euthanasia was performed according to the Rules for Conducting Work Using Experimental Animals by direct cervical dislocation.

To evaluate viral replication, lungs were collected from five mice per group on day 3 post-immunization and individually homogenized in 1 mL of cold phosphate-buffered saline using a TissueLyser LT homogenizer (QIAGEN, USA). Homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm to remove debris and stored at −70°C. Viral titers in lung homogenates were determined by titration in 10-day-old embryonated CE and expressed as log10 EID50/0.1 mL. Titers were calculated according to the Reed–Muench method [31].

Serum IgG antibody levels to influenza virus were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using high-capacity 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) pre-coated with 20 agglutinating units (AU) of the wild-type A/South Africa/3626/13 (H1N1)pdm09 virus. To detect antibodies against pneumococcal inserts, plates were coated with recombinant Psp peptide (2 μg/mL) containing the Spr1875 sequence. The Psp protein, composed of three immunodominant fragments of pneumococcal surface virulence factors (PsaA, PspA, and Spr1875), was kindly provided by the Molecular Microbiology Department of the Institute of Experimental Medicine. For assays, plates were coated with Psp in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6, 100 μL per well), incubated overnight at 4°C, and ELISA was performed as described previously [14]. The antibody titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution yielding an optical density at 490 nm exceeding the mean control value by more than three standard deviations.

The human monocyte–macrophage cell line THP-1 was used to assess early cytokine production in vitro. Cells were maintained in RPMI medium (Roswell Park Memorial Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. THP-1 cells were seeded at 0.6 × 106 cells per well in 24-well plates and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48 h. Viability (> 90%) was confirmed microscopically prior to infection.

Cells were then infected with 1 × 106 EID50/0.1 mL of the A/17/South Africa/2013/01 (H1N1)pdm09 vaccine virus or recombinant vaccine candidates H1-ScaAB, H1-PspA, and H1-Spr. Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly I:C; Sigma, St. Louis, USA) at a final concentration of 1 μg/mL served as a positive control, and RPMI medium alone was used as a negative control. Plates were incubated for 24 h, after which supernatants were collected for cytokine analysis. Levels of TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, and IFN-α were measured using commercial ELISA kits (Vector-Best, Novosibirsk, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or geometric mean ± SD for titer measurements. Reciprocal viral titers (EID50) and ELISA antibody titers (IgG, sIgA) were log10-transformed prior to analysis. Data normality and variance homogeneity were assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. When parametric assumptions were met, group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test; otherwise, the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post-hoc test was applied. All tests were two-tailed, and differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Sample sizes (n), statistical tests used, and multiple-testing corrections are indicated in the respective figure legends.

The Spr1875 insert exhibited an instability index of 34.97, indicating that the protein is relatively stable. Secondary structure predictions show that more than 50% of the sequence remains in unstructured coil regions. A single α-helical segment of three residues was identified, while the rest of the sequence remains as a flexible coil region interspersed with occasional β-fragments. Thus, the overall structure of this fragment appears sparse and flexible, without features of a stable, compact core. Spr1875 lacks distinct linear endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) motifs, which lowers the likelihood of retention and degradation of newly synthesized HA in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [32].

At the same time, neither complete RX-[K/R]-R↓ furin motifs (typical of HA0) nor other known cleavage sites within the Golgi lumen were identified, suggesting a low probability of unintended proteolysis. Overall, the Spr1875 insert preserves the native HA0 profile: It is relatively stable and does not contain ERAD-related degradation motifs or protease recognition sites that could compromise HA folding or transport through the ER–Golgi pathway.

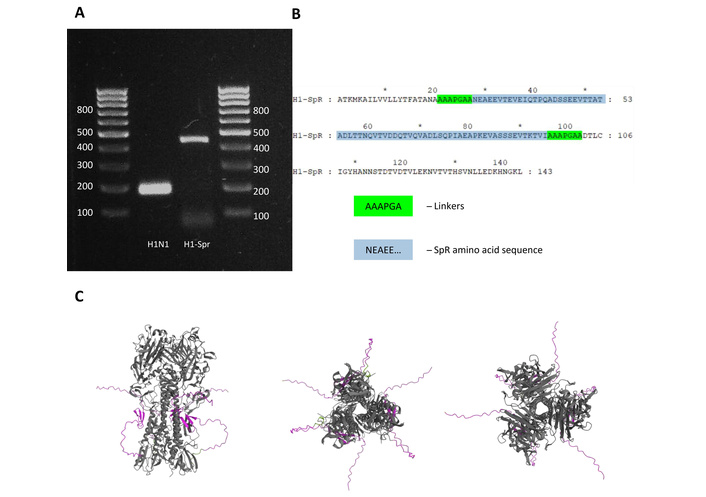

The HA-insert PCR product and the amino-acid sequence of the Spr1875 insert are shown in Figure 1A and 1B, respectively. Comparison of the HA model containing the Spr1875 insert with the unmodified A/H1N1 HA structure in PyMOL (Figure 1C) revealed a high degree of structural identity. Superimposition of atomic coordinates yielded a final root mean square deviation (RMSD) of only 0.206 Å, confirming preservation of the overall three-dimensional organization of the protein.

Molecular characterization of H1-Spr. (A) Agarose electrophoresis of the HA-insert PCR product. (B) Amino-acid sequence of the Spr1875 insert (linker indicated). (C) AlphaFold3 model (side/bottom/top views). Flexible linker = green; Spr1875 insert = pink; HA = grey. Model metrics: ipTM = 0.84, pTM = 0.85; final RMSD vs. reference HA = 0.206 Å. No clear furin-like cleavage motifs were identified in the insert.

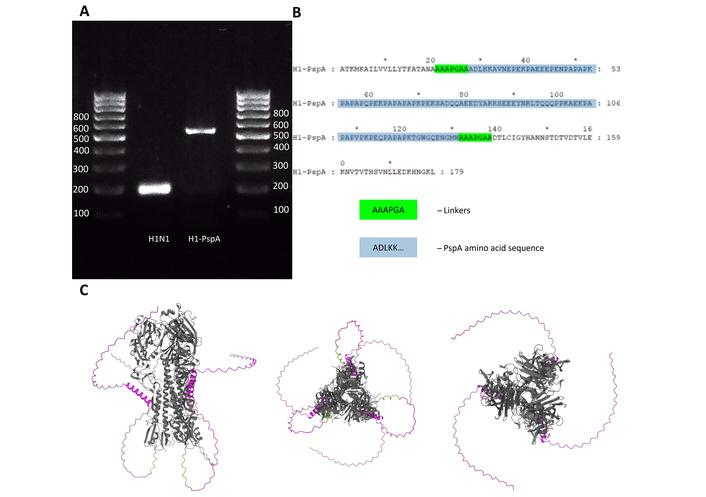

The PspA insert, comprising 103 amino acids (Figure 2A, B), has an estimated isoelectric point (pI) of approximately 5.0 and a very high instability index of 96.28, suggesting a strong tendency toward proteolysis. Its pronounced hydrophilicity (Grand Average of Hydropathicity, GRAVY = –1.32) reflects the predominance of polar and charged residues, which reduces the likelihood of forming a compact hydrophobic core and renders these regions predisposed to an unstructured or flexible conformation.

Molecular characterization of H1-PspA. (A) Agarose electrophoresis of the HA + PspA PCR product. (B) Amino-acid sequence of the PspA insert (linker annotated). (C) AlphaFold3 model (side/bottom/top views). Flexible linker = green; PspA insert = pink; HA = grey. Model metrics: ipTM = 0.81, pTM = 0.80; final RMSD = 0.283 Å (note: Early alignment cycles rejected ~267 atoms, indicating local conformational distortions). The insert is predicted to be highly disordered and contains potential processing motifs.

The PspA insert comprises three short α-helical segments and one β-sheet region, while over 75% of the sequence remains as unstructured coil fragments. Pronounced hydrophilicity and intrinsic instability create a flexible, non-compact region that could be recognized as a misfolded domain and targeted for degradation via the ERAD (HRD1/gp78) pathway. The ELM database identifies RRS (64–66) and RKS (89–91) as potential Nardilysin sites; however, in the context of HA0, furin specificity (RX-[K/R]-R↓) is more relevant, with cleavage of mature HA occurring on the cell surface by TMPRSS2-like proteases [33]. Therefore, the functional relevance of these ELM predictions within the ER/Golgi remains uncertain.

To assess the impact of the PspA insertion on global HA conformation, structural superposition of the model containing the insertion with the native HA model was performed in PyMOL (Figure 2). The final RMSD between 10,869 atoms was 0.283 Å, indicating overall structural conservation. However, during early alignment cycles up to 267 atoms were excluded (RMSD = 0.42 Å at cycle 2), revealing local conformational distortions.

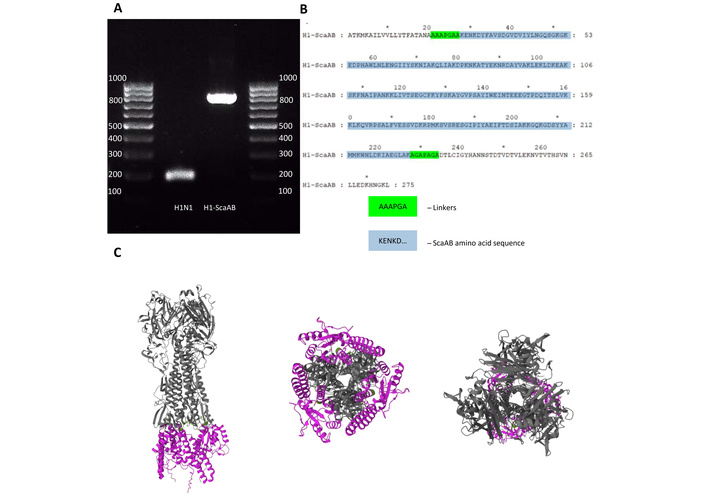

The ScaAB insertion consists of 202 amino acids (Figure 3A, B).

Molecular characterization of H1-ScaAB. (A) Agarose electrophoresis of the HA + ScaAB PCR product. (B) Amino-acid sequence of the ScaAB insert (linker marked). (C) AlphaFold3 model (side/bottom/top views). Flexible linker = green; ScaAB insert = pink; HA = grey. Model metrics: ipTM = 0.73, pTM = 0.72; reported RMSD ≈ 18.08 Å with an alignment warning, consistent with extensive local and global rearrangements induced by the extended insertion. Putative dibasic/furin-like motifs were identified at positions 81–85, 136–140, and 154–156.

The high pI (~9.1) of the ScaAB insertion indicates a predominance of basic residues, imparting a positive charge to the HA N-terminus at physiological pH. Combined with an instability index of 31.01 and moderate GRAVY (–0.56), this may perturb signal-peptide recognition and translocation across the ER membrane. PSIPRED predicts a predominance of α-helical structures, accounting for more than half of the sequence, suggesting formation of a partially ordered core. In contrast, β-sheet elements constitute < 15% of the sequence and appear as short, discontinuous fragments within unstructured regions.

The presence of dibasic RX-[KR]-R motifs in ScaAB (positions 81–85 and 136–140) and an additional RRX motif at 154–156 matches furin-like cleavage patterns. However, their activity in the HA context requires experimental confirmation, as the proximity to the N-terminus may prevent proper exposure for proteolytic processing [34].

The large RMSD (18.08 Å) obtained in PyMOL analysis (Figure 3), even after excluding ≈ 600 atoms, together with the alignment warning, indicates substantial global perturbation of the HA-H1-ScaAB structure. Although part of this discrepancy may reflect the size of the inserted domain, the result suggests that ScaAB can markedly alter HA folding and topology.

When assessing potential N-linked glycosylation sites by integrating sequence-based NetNGlyc predictions with per-residue SASA values from GetArea applied to AlphaFold3 models, the following patterns were observed. Despite the N-terminal insertions, canonical HA sequons were retained but renumbered. Notably, stalk-region glycan exposure varied among constructs:

In H1-Spr, the stalk Asn (Asn366) was highly exposed (SASA = 134.51 Å2, 96.2% exposure);

In H1-PspA, the corresponding Asn (Asn401) was partially exposed (SASA = 56.93 Å2, 46.5%);

In H1-ScaAB, the stalk Asn (Asn494) was fully exposed (SASA = 149.25 Å2, 100%).

By contrast, principal head sequons remained highly predicted and consistently exposed across all constructs. These findings indicate that the composition and length of N-terminal inserts can locally modulate stalk glycan exposure without affecting canonical head sites.

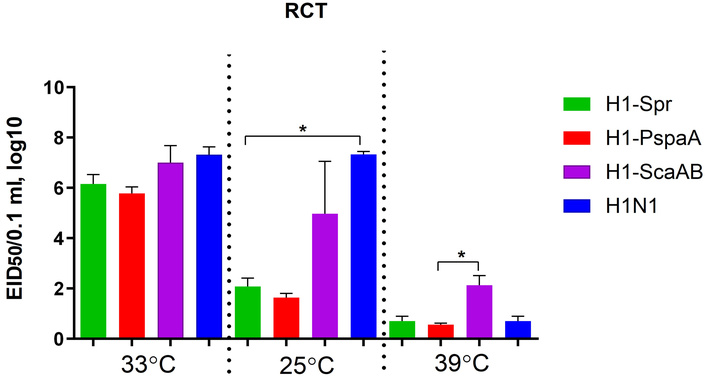

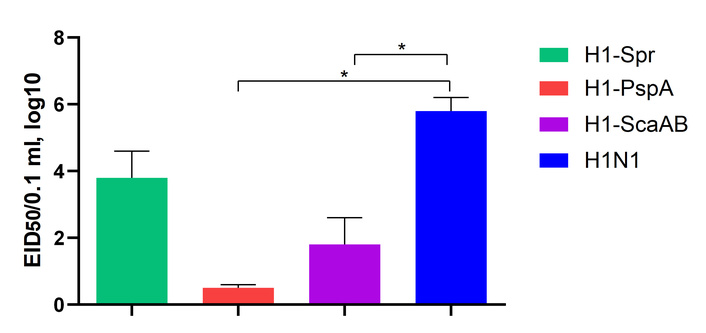

Based on the results of the evaluation of the replication efficiency of chimeric vaccine candidates H1-Spr 1875, H1-PspA, and H1-ScaAB in chicken embryos (CE) at different incubation temperatures, their phenotypes were characterized (Figure 4).

Reproductive activity of vaccine candidates at different incubation temperatures (log10 EID50/0.1 mL). Data are mean ± SD, n = 5 per group. Statistical test: Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc. *: p < 0.05.

At the optimal temperature (33°C), the highest titer was observed for the parental H1N1 vaccine strain. The recombinant viruses showed slightly lower levels of infectious activity (Figure 4). At low incubation temperatures, however, replication rates differed significantly (Kruskal–Wallis test, p = 0.017). Pairwise comparisons revealed that vaccine candidates carrying the H1-Spr HA were significantly less efficient in replication at low temperatures compared to the original unmodified H1N1 strain (Figure 4).

All viruses exhibited the ts+ phenotype, confirming temperature sensitivity consistent with the requirements for live attenuated vaccines. The H1N1 vaccine strain displayed ts–/ca– phenotypes—it did not replicate at 39°C but retained active replication at 25°C (Figure 4). In contrast, the H1-Spr and H1-PspA strains showed markedly reduced replication at 25°C relative to 33°C, indicating the absence of cold adaptation while maintaining temperature sensitivity. The H1-ScaAB virus, however, exhibited a ca+ phenotype and replicated more efficiently than the other recombinant candidates at elevated temperature (Kruskal–Wallis test, p = 0.004).

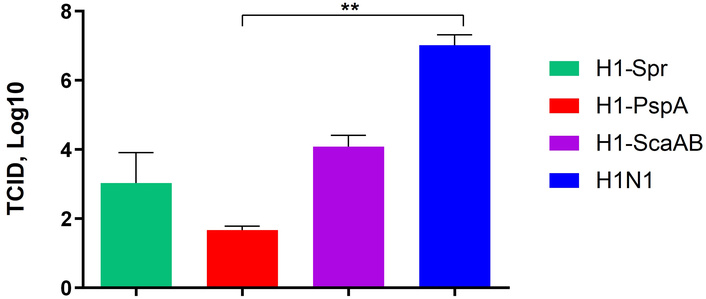

The growth characteristics of the recombinant vector vaccines were analyzed in MDCK cell culture under optimal incubation conditions (33°C) for cold-adapted viruses (Figure 5). Replication of the H1-PspA virus was significantly reduced compared with the parental H1N1 strain, whereas H1-Spr and H1-ScaAB showed slightly lower replication levels, though the differences were not statistically significant.

Replication of vaccine candidates in MDCK cells (log10 TCID50/mL). Data are mean ± SD, n = 5. Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc. **: p < 0.01.

Replication levels of the studied viruses in mouse lungs were assessed on day 3 after intranasal immunization (Figure 6).

Viral titers in mouse lungs on day 3 after intranasal immunization (log10 EID50/0.1 mL). Data are mean ± SD, n = 5 mice/group. Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc. *: p < 0.05.

All three recombinant candidates exhibited reduced replication in mouse lungs compared with the parental H1N1 strain on day 3 post-immunization. The reductions were statistically significant for H1-ScaAB and H1-PspA (Figure 6).

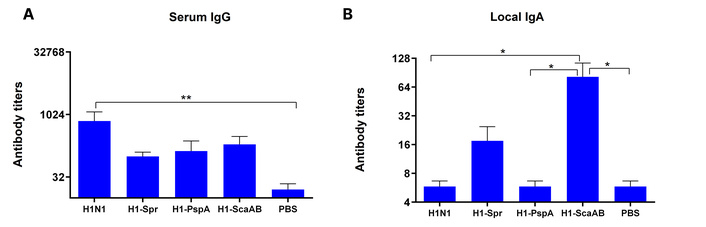

The immunogenicity study demonstrated that only the unmodified H1N1 vaccine strain induced a statistically significant increase in serum IgG antibodies to A/South Africa/3626/13 (H1N1)pdm09 three weeks post-immunization (Figure 7A). In contrast, a significant increase in local antiviral IgA was observed only after administration of the recombinant H1-ScaAB strain (Figure 7B).

Serum IgG (A) and nasal IgA (B) to A/South Africa/3626/13 (H1N1)pdm09, day 21 post-immunization (log10 titers, geometric mean ± SD). n = 6 mice/group. Tests: ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01.

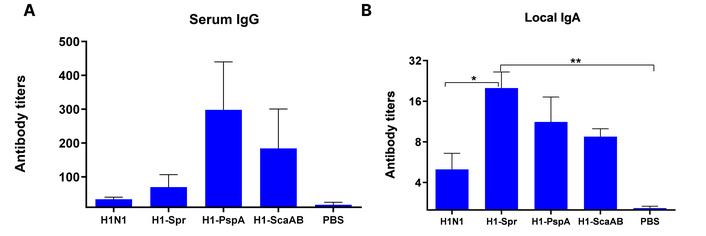

No statistically significant increase in local IgA was detected following immunization with the other recombinant candidates. However, the highest average serum antibody level to the recombinant pneumococcal peptide was observed in the H1-PspA group (Figure 8A). In addition, the H1-Spr candidate induced a statistically significant increase in antibodies specific to the recombinant pneumococcal peptide Psp (Figure 8B).

Serum (A) and local antibodies (B) to the recombinant peptide of Streptococcus pneumoniae on day 21 after intranasal administration of vaccine candidates to mice. Antibody responses to the recombinant pneumococcal peptide, day 21 (log10 titers, geometric mean ± SD). n = 6 mice/group. Tests: ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01.

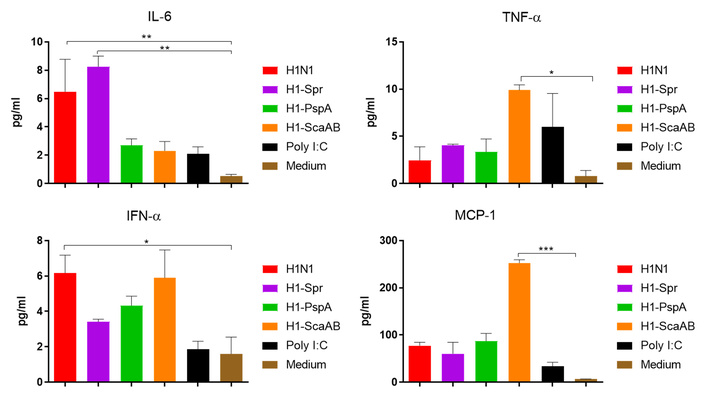

In THP-1 monocyte–macrophage cultures, early cytokine production varied among constructs (Figure 9).

Early cytokine production in THP-1 cells (ELISA at 24 h). Data are mean ± SD. Test: Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01.

Exposure to the unmodified H1N1 strain resulted in the highest IFN-α production, IL-6 levels were elevated following exposure to H1N1 and H1-Spr, while MCP-1 concentrations were highest after H1-ScaAB exposure. Given the limited number of independent experiments, these observations are preliminary and require confirmation in additional biological replicates and more physiologically relevant models.

Table 3 summarizes the main biological characteristics of the recombinant vaccine candidates A/H1N1pdm09 with modified HA, compared to the parental H1N1 strain.

Summary table of identified features of recombinant vaccine strains.

| Characteristic | H1N1 | H1-Spr | H1-PspA | H1-ScaAB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stability of chimeric HA structure | n/a | +++ | + | +++ |

| Reproduction in chicken embryos | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++++ |

| Reproduction in MDCK cell line | ++++ | +++ | + | ++ |

| Reproduction in mouse lungs | ++++ | +++ | + | ++ |

| Systemic IgG to influenza virus | ++++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Local IgA to influenza virus | + | +++ | + | ++++ |

| Systemic IgG to Psp protein | n/a | ++ | ++++ | +++ |

| Local IgA to Psp protein | n/a | ++++ | +++ | ++ |

| In vitro cytokine induction | +++ | + | ++ | +++ |

Symbols reflect intensity of indicators: “n/a” = not applicable; “+” = low; “++” = moderate; “+++” = notable; “++++” = high.

The unmodified H1N1 vaccine strain replicated efficiently in chicken embryos, MDCK cells, and mouse respiratory tissues, and induced a robust systemic immune response to influenza virus. The H1-ScaAB candidate also showed high replication efficiency in chicken embryos and induced a local antibody response to influenza virus. In contrast, the recombinant strains H1-Spr and H1-PspA exhibited lower replication in chicken embryos, MDCK cells, and mouse lungs, resulting in a comparatively weaker immune response to influenza virus. However, these constructs elicited the most pronounced local and systemic antibody responses to the pneumococcal Psp peptide, respectively.

Recombinant viral vectors represent a promising platform for delivering heterologous antigens, combining the advantages of live antiviral and genetically engineered vaccines. Such vectors ensure efficient antigen presentation and induction of both humoral and CD8+ T-cell responses without the need for exogenous adjuvants, which is critical for preventing infectious diseases [35]. When influenza virus is used as a vector system, insertions of foreign genetic information can be introduced into several viral RNA segments. Most commonly, the HA, NA, and NS genes serve as insertion sites [17, 36, 37]. Insertions into NS and into the NA stalk region preferentially stimulate cellular immunity, whereas NA modifications tend to enhance humoral responses [38].

In this work, we investigated three insert variants derived from S. pneumoniae proteins (Spr1875, PspA) and S. agalactiae (ScaAB) to assess their impact on the biological characteristics of recombinant influenza viruses. Mutations or modifications within HA can alter its spatial structure and thereby affect receptor binding [39]. If a newly introduced antigen does not conform to the HA scaffold or interferes with proper folding, this can impair viral infectivity and reduce replication capacity [40].

Based on three-dimensional structural modeling and experimental data, we propose that pneumococcal peptides fused to the N-terminus of HA influence its conformation and, consequently, viral growth properties and temperature sensitivity. The H1-Spr strain, carrying a relatively compact insert, showed only minor reductions in replication in chicken embryos, suggesting minimal distortion of HA trimer organization and preservation of native folding. Structural predictions likewise indicated that the Spr1875 insertion did not substantially disrupt HA architecture or assembly.

By contrast, we observed construct-specific variation in stalk glycan exposure, which may contribute to some of the functional differences observed among the chimeric viruses. These differences could influence multiple aspects of HA behavior. For instance, altered sequon accessibility might affect HA folding, trimerization, or incorporation efficiency into virions—factors that could, among others, underlie the reduced replication of H1-PspA and the pronounced cold-adapted phenotype of H1-ScaAB. In addition, local glycan packing could modulate antigenic masking: greater stalk glycan exposure (H1-Spr, H1-ScaAB) might limit access to conserved epitopes and reduce binding of broadly neutralizing stalk antibodies, whereas lower exposure (H1-PspA) could facilitate recognition of stalk or insert epitopes, possibly contributing to the stronger systemic anti-Psp responses elicited by H1-PspA. Overall, glycan-related effects are likely to act together with insert-intrinsic properties (such as charge, disorder, or lipoprotein motifs in ScaAB) and other structural factors may collectively contribute to or be associated with the observed differences in replication, mucosal IgA induction, and cytokine responses.

Further structural analysis suggested that the PspA insert carries an increased risk of ERAD and defective proteolysis in the Golgi. Although the ELM motifs detected are unlikely to function in the ER, the combination of high flexibility and spurious processing sites makes this construct the least favorable for maintaining HA integrity. Local structural disruptions in H1-PspA may therefore impair folding and trafficking in cellular expression systems. In the case of ScaAB, the insertion introduces potential competition with the HA1 region and susceptibility to proteolysis, although its motifs only weakly resemble furin sites. Additional in vitro assays will be required to confirm the impact on HA cleavage and trimer assembly.

Replication studies highlighted that bacterial insertions differentially affected viral growth. The H1-ScaAB strain replicated at levels comparable to the parental A/H1N1pdm09 strain at 33°C, while H1-Spr and especially H1-PspA displayed reduced replication in eggs, MDCK cells, and mice. The particularly severe restriction in H1-PspA likely reflects conformational interference with HA folding and receptor interactions. Importantly, the relationship between insert size and replication was not linear: Despite its larger insert, H1-ScaAB maintained replication competence and cold-adaptation, suggesting possible structural stabilization under these conditions.

Beyond replication, immune profiling revealed that recombinant strains induced distinct cytokine patterns in monocyte–macrophage cultures. Cytokine production measured in the THP-1 monocytic cell line provides a useful comparative readout of early innate activation by our constructs but is not a surrogate for mucosal immune responses in vivo. THP-1 cells differ from primary human alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells in receptor expression and signalling thresholds and do not recapitulate epithelial–immune cell crosstalk that shapes mucosal immunity. Therefore, while increased IFN-α, IL-6 or MCP-1 in THP-1 cultures suggests differential innate activation between constructs, these data should be interpreted cautiously and validated in more physiologically relevant systems. Such differences are consistent with previous reports that HA structural variation can modulate innate immune signaling [41]. In addition, our earlier work demonstrated that ScaAB, a major lipoprotein, triggered type I interferon production comparable to that of live influenza virus and exerted a protective effect in murine models [42]. This likely explains the enhanced cytokine responses observed for H1-ScaAB. Notably, mucosal anti-influenza IgA levels were significantly higher in the H1-ScaAB group than in unmodified H1N1. Although upper respiratory replication was not directly measured, H1-ScaAB was the only recombinant strain classified as cold-adapted in eggs. Differences in cold adaptation may therefore increase local antigen availability and favor IgA induction. Additional explanations include altered HA epitope display or adjuvant-like activation of mucosal innate receptors by lipoprotein motifs.

Taken together, our findings emphasize that each recombinant strain occupies a distinct position along the replication-immunogenicity spectrum. H1-PspA and H1-Spr, while effective at presenting pneumococcal antigens, exhibited reduced replication and failed to elicit systemic influenza IgG responses comparable to parental H1N1, raising concerns about their suitability as standalone LAIV candidates. In contrast, H1-ScaAB combined relatively higher replication with structural stability and uniquely induced robust mucosal IgA against influenza—characteristics that may partially compensate for its lower systemic IgG. This construct may therefore represent a more balanced prototype, though confirmatory studies remain essential. Overall, our results highlight a trade-off: Reduced replication can enhance heterologous insert immunogenicity, but often at the expense of systemic influenza antibody titers. Future optimization may involve engineering inserts to restore HA stability, adjusting vaccine dose or regimen, or deploying recombinant strains as components of heterologous prime-boost strategies rather than as single-agent vaccines.

Finally, several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. We did not measure viral replication kinetics in the upper respiratory tract, performed only limited functional antibody assays, and did not conduct challenge/protection experiments. Structural characterization relied primarily on in silico modeling and therefore requires experimental validation. Addressing these gaps will be essential for optimizing vaccine formulations and for comprehensive preclinical evaluation.

ca+: cold-adapted

CE: chicken eggs

EID50: 50% embryonic infectious dose

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ER: endoplasmic reticulum

ERAD: endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

GRAVY: Grand Average of Hydropathicity

HA: hemagglutinin

LAIV: live attenuated influenza vaccine

NA: neuraminidase

pI: isoelectric point

RMSD: root mean square deviation

SASA: solvent-accessible surface area

ts+: temperature-sensitive

YD: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. IM: Investigation, Writing—original draft. AR: Writing—review & editing. PK: Investigation, Formal analysis. AT: Investigation. DP: Investigation, Validation. TK: Investigation, Validation. NK: Investigation. AM: Investigation. DS: Investigation. DG: Investigation. IIS: Conceptualization, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This study complies with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The work was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “IEM” (Institute of Experimental Medicine), protocol No. 1/21 dated January 28, 2021.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

The work was carried out at the expense of budgetary funds of the Federal State Budgetary Institution “IEM” within the framework of the research project - FGWG-2025-0015. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 896

Download: 28

Times Cited: 0

Marc H.V. Van Regenmortel

Christine Jacomet

Vladimir N. Uversky

Brent Brown ... Ingo Fricke

Chittaranjan Baruah ... Bhabesh Deka

Brent Brown ... Enrique Chacon-Cruz

Om Saswat Sahoo ... Subhradip Karmakar

Mikolaj Raszek ... Alberto Rubio-Casillas

Ankit Kumar ... Vijay Mishra