Affiliation:

1Department of Industrial Chemistry, Faculty of Physical Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin 240003, Nigeria

2Quality Assurance Department, Biomedical Limited, Ilorin 240211, Nigeria

Email: ayuba.mustapha@biomedicalng.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-5529-0759

Affiliation:

3Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin 240003, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-0363-4186

Affiliation:

4Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Applied Science, KolaDaisi University, Ibadan 200212, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1886-6475

Affiliation:

1Department of Industrial Chemistry, Faculty of Physical Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin 240003, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9626-012X

Affiliation:

5Department of Chemistry and Industrial Chemistry, Kwara State University, Malete 241104, Nigeria

Explor Drug Sci. 2026;4:1008140 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2026.1008140

Received: October 20, 2025 Accepted: December 04, 2025 Published: January 09, 2026

Academic Editor: Kamal Kumar, Aicuris Anti-infective Cures AG, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Physiology, Germany

The article belongs to the special issue Discovery and development of new antibacterial compounds

Aim: The prevalence of multidrug-resistant “superbugs”, particularly Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae, is a menacing phenomenon in society, rendering last-resort antibiotics increasingly suboptimal and ineffective. Carbapenemase enzymes play a major role in this resistance by hydrolysing carbapenem antibiotics. This study aims to identify and characterize potential non-covalent carbapenemase inhibitors using multiscale computational approaches.

Methods: A focused library of 245 compounds, comprising pharmacopeial derivatives and chemogenomic molecules, was screened using a hierarchical virtual screening workflow. Top-ranked hits were further evaluated by rescoring for thermodynamic affinity. The most promising candidate was subjected to a 100 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to assess binding stability, followed by Well-Tempered Metadynamics (WTMetaD) to characterise the free energy landscape and binding behaviour. Pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles were predicted using SwissADME and ProTox 3.0.

Results: Three compounds, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, and EUB0000226b, emerged as potential carbapenemase inhibitors. EUB0000226b demonstrated the most favourable binding affinity and structural novelty. MD simulations showed protein stability, while ligand RMSD fluctuations (2.4–5.6 Å) suggested flexible binding. WTMetaD analysis revealed a solvent-separated metastable state that increased ligand residence time within the active site. ADME and toxicity predictions indicated acceptable drug-likeness, good gastrointestinal absorption, and a generally safe profile.

Conclusions: Multiscale computational analysis identified EUB0000226b as a promising non-covalent carbapenemase inhibitor with favourable binding energetics, dynamic stability, and drug-like properties. These findings support its further experimental validation and potential development for combating carbapenem-resistant bacterial pathogens.

Multidrug resistance (MDR) remains a formidable barrier to the successful treatment of cancer and infectious diseases, often leading to therapeutic failure, relapse, and high mortality rates in humans and animals [1, 2]. A primary contributor to MDR is the overexpression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp), AcrAB-TolC, which actively efflux chemotherapeutic agents out of target cells [3, 4]. Other genes in bacteria responsible for MDR include gyrA, gyrB, CmeDEF, MDR1, and MDP1, commonly by enhancing drug efflux, modifying drug targets, or inactivating drugs [5, 6].

The increasing antibiotic resistance observed across several microorganisms, especially in Helicobacter pylori, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, Campylobacter, and Salmonella enterica, poses a severe threat to public health in relation to food-borne and nosocomial (hospital-related) infections [7]. This concern is underscored by the World Health Organisation’s WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL) (2024), which prioritises and categorises pathogens based on their criticality, aimed to guide research, development, and public health responses [8, 9]. These pathogens are major threats to public health, causing several million deaths worldwide. WHO labelled these pathogens “superbugs” owing to their ability to resist multiple antibiotic classes. Among these, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacteriaceae are dubbed critical priority pathogens. These organisms are known to cause life-threatening infections, including ventilator-associated pneumonia and bloodstream infections [10].

Despite intensive research, the rise of MDR in bacteria remains a significant clinical challenge and is mostly due to improper use and overuse of antibiotics, which results in the emergence of a variety of mechanisms that could be intrinsic or acquired [11, 12]. These mechanisms categorised by biological function are (a) drug efflux such as the AcrAB-TolC [13], (b) drug inactivation, e.g., beta-lactamases such as KPC-2 causing the deactivation of antimicrobials by enzymes such as mutations in gyrA of Escherichia coli (E. coli) [13], (c) altered drug targets from mutations of structural conformation of the target protein [14], (d) DNA damage repair enhancement [15, 16] and (e) epigenetic alterations such as DNA methylation changes in Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) [17]. Existing strategies to combat these superbugs include the use of combination therapy (like antibiotic + inhibitor), inhibition of drug efflux pumps [Verapamil inhibiting P-gp and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP)], neutralisation of virulence factors, blockage of biofilm formation or epithelial clinging, etc. [18–20].

Several studies have investigated the prevalence of MDR in clinical settings, showing dominance of Acinetobacter baumannii amongst the class [21–23]. Acinetobacter baumannii, an ESKAPE pathogen, is a gram-negative bacterium known to cause fatal nosocomial infections [24]. It is a non-motile aerobic coccobacillus known to be highly drug-resistant [25]. Identified as one of the most drug-resistant organisms with a prevalence rate up to 89.5% [26], Acinetobacter baumannii’s resistant genes can spread across different geographical regions. MDR-Acinetobacter baumannii (MDRAB) prevalence has been recorded in parts of Africa, especially Nigeria, Europe, Asia, and the Americas [27, 28].

Klebsiella pneumoniae, family Enterobacteriaceae, also an ESKAPE pathogen, according to Teklu et al. (2019) [29], was recorded to have a very high prevalence in clinical settings, with a record mortality second to E. coli in 2019 [30]. This organism has been found to colonise different systems in the human body. These systems include the gastrointestinal, urinary, and respiratory systems. It is known to cause community and hospital-related infections [31]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous and opportunistic environmental bacterium that also causes infection in humans [32].

Current MDR inhibitors often exhibit suboptimal efficacy, off-target toxicity, or poor bioavailability, necessitating the development of novel, selective compounds with improved pharmacological profiles [33]. A wide range of molecular scaffolds, including natural products, nanoparticles, coordination compounds, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), and plant-derived phytochemicals, are being investigated as potential MDR modulators, each leveraging diverse mechanisms to overcome bacterial resistance [34–36].

This study aims to identify potential inhibitors of MDR bacteria from compound libraries using in silico techniques, including a structure-based virtual screening approach, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and pharmacokinetic profiling to assess the stability, efficacy, and druglikeness of promising hits. This study was conducted from May 2025 to September 2025.

Whole Genome Sequence (WGS) raw reads were obtained from NCBI Sequence Reads Archive (SRA) following WHO BPPL 2024 classifications search parameter (Table 1). The quality of the reads was initially assessed using FASTQC and validated using FALCO on the Galaxy platform (https://usegalaxy.eu) [37].

Carbapenem-resistant search parameter.

| No. | Key description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) | WHO BPPL, 2024 |

| 2 | Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) | WHO BPPL, 2024 |

| 3 | Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA) | WHO BPPL, 2024 |

Assembly and annotation were carried out on BV-BRC (version 3.55.17, https://www.bv-brc.org/) using the default protocol. Assembly quality metrics, gene counts, and content analysis were computed, with special focus on identifying MDR-associated genes. Carbapenem resistance profiles were inferred; genes and plasmid replicons were identified using ResFinder v4.7.2 [38, 39], PlasmidFinder2.0 [40, 41], and Bakta (useGalaxy) [37].

Homology models were identified using NCBI BLASTp to identify protein templates, retrieved from RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/), and then assimilated to their sequences. The models were validated via Ramachandran plots, and stereochemical quality was evaluated. Thereafter, the targets were prepared using the Schrödinger preparation wizard, utilising OPLS4 [42].

Two compound libraries were used: 97 pharmacopeial derivatives (British Pharmacopoeia 2024) and 148 chemogenomic compounds from the MolPort repository (https://www.molport.com/shop/libraries/chemogenomics). Ligands were prepared using Schrödinger LigPrep (release 2024) at pH 7.4 ± 2, allowing for stereoisomeric and protonation state generation. The two libraries were selected to balance clinical relevance with chemical diversity. The pharmacopoeial derivatives represented pharmaceutically established compounds or known by-products of approved active pharmaceutical ingredients. These molecules have well-characterised safety, physicochemical properties, and exposure profiles, making them suitable candidates for repurposing against carbapenemases. Repurposing such compounds can accelerate translational potential because their ADME and toxicity characteristics are already defined.

The MolPort chemogenomic library was included to broaden the search space toward novel scaffolds that are structurally distinct from classical beta-lactamase inhibitors. Chemogenomic libraries contain compounds pre-enriched for biological activity and mechanistic diversity, increasing the likelihood of identifying non-beta-lactam chemotypes capable of engaging the carbapenemase active site through alternative interaction modes. In the context of carbapenemase inhibition, this dual-library strategy supports both the identification of repurposable agents and the discovery of chemically novel inhibitors with favourable energy profiles.

Protein-ligand docking was conducted using Glide (Schrödinger Release 2024) in HTVS, SP, and XP modes, followed by Prime molecular mechanics-generalised Born surface area (MM-GBSA) rescoring [43, 44]. Grid boxes were centered on co-crystallized ligands (meropenem for 4jf4_A and avibactam for 4s2j_A). Binding free energies (ΔG_bind) were estimated to prioritize hit compounds.

The top-scoring hit was simulated for 100 ns using Desmond (Schrödinger). The complex was solvated in a TIP3P water box (10 Å × 10 Å × 10 Å), neutralized with Cl– ions, and simulated under physiological and NPT conditions (300 K, 1.01325 bar). Protein and ligand Root Mean Square Deviation/Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSD/RMSF) and persistent contacts were monitored [45, 46].

WTMetaD was performed post hoc to explore the free energy landscape (FEL). Two collective variables (CVs) were defined using distances to generate a 2D free energy surface (FES) map to study ligand-protein unbinding and associated events for up to 12 Å. Gaussians (1 kcal/mol with kTemp 2.4 at 300 K) were deposited to reconstruct the FEL and identify bound and metastable states while monitoring the bias potential for convergence [47].

SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) was used to evaluate pharmacokinetic properties and rule-of-five compliance [48]. Toxicity profiling with precalculated probabilities was performed using ProTox 3.0 (https://tox.charite.de/protox3/) for organ-specific and mechanistic toxicities, including hepatotoxicity, mutagenicity, and immunotoxicity [49].

Gaussian 09 [50] was used for geometry optimization and descriptor calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory [51, 52] with IEFPCM solvation (water) [53]. Descriptors computed include the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)-lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy gap, dipole moment, chemical hardness (η), chemical potential (μ), electronegativity (χ), electrophilicity (ω), and global softness (S) to assess the reactivity profile of the ligand [54]. Table 2 gives the formula for the descriptors.

Global reactivity descriptor formula.

| No. | Descriptor | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Electron affinity (A) | A = –ELUMO [55] |

| 2 | Ionisation potential (I) | I = –EHOMO [55] |

| 3 | Energy gap (ΔE) | ΔE = ELUMO – EHOMO [55] |

| 4 | Electronegativity (χ), chemical potential (μ) | χ = (I + A)/2 = –μ [55] |

| 5 | Chemical hardness (η) | η = (I – A)/2 [55] |

| 6 | Softness (S) | S = 1/η [56] |

| 7 | Electrophilicity (ω) | ω = μ2/2η [57] |

HOMO: highest occupied molecular orbital; LUMO: lowest unoccupied molecular orbital.

Table 3 gives gene content and quality metrics from the assembly and annotation of the reads. The GC content for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB), carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP), and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA) genomes was approximately 38.99%, 57.15%, and 66.38%, respectively, with corresponding genome lengths of ~3.8 Mbp, 5.4 Mbp, and 6.5 Mbp. These values are consistent with known genomic characteristics of the respective species [58–61], thereby validating the suitability of the selected SRA sequences for downstream analysis.

Gene content metrics obtained.

| No. | Description | CRAB | CRKP | CRPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accession number | SRR19723078 [62] | SRR32133156 [63] | SRR31701364 [64] |

| 2 | Assembler | Unicycler v0.4.8 | ||

| 3 | Trimmer | Trim_galore v0.6.5dev | ||

| 4 | Contigs | 128 | 72 | 121 |

| 5 | Total length (Mbp) | 3,810,118 | 5,419,404 | 6,462,780 |

| 6 | Largest contig | 189,859 | 683,806 | 657,782 |

| 7 | GC (%) | 38.99 | 57.15 | 66.38 |

| 8 | N50 | 68,896 | 245,718 | 219,243 |

| 9 | L50 | 17 | 7 | 9 |

| 10 | Completeness (%) | 100 | 96.4 | 99.3 |

| 11 | Contamination (%) | 0 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| 12 | rRNA | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 13 | tRNA | 64 | 56 | 56 |

| 14 | CDS | 3,670 | 5,383 | 6,120 |

CRAB: carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii; CRKP: carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae; CRPA: carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

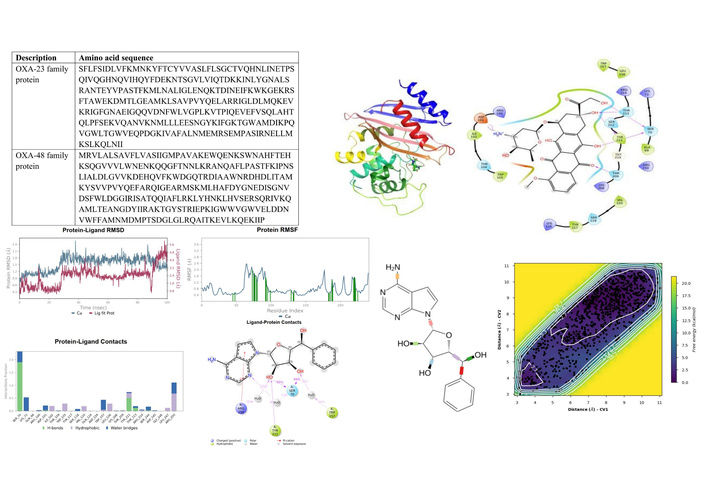

An overview of the genes associated with MDR identifies membrane transport and stress response genes as the mechanism to escape antibiotics. These genes are in the form as antibiotic targets in DNA processing, cell wall biosynthesis, metabolic pathways, protein synthesis, transcription, arsenic resistance, bacitracin resistance, beta-lactamases ambler class C and class D, efflux ABC, ABC transport system, MDR tripartite system, MDR RND efflux system, mupirocin resistance, polymyxin resistance, daptomycin resistance, triclosan resistance, tetracycline resistance and MFS/RND tripartite MDR efflux system. However, carbapenem resistance genes were identified as class D beta-lactamases (OXA-23 family, carbapenem hydrolysing in CRAB, and OXA-48 family, carbapenem hydrolysing in CRKP) with sequences as depicted in Table 4.

Carbapenemase protein sequences.

| Description | Amino acid sequence |

|---|---|

| OXA-23 family protein | SFLFSIDLVFKMNKYFTCYVVASLFLSGCTVQHNLINETPSQIVQGHNQVIHQYFDEKNTSGVLVIQTDKKINLYGNALSRANTEYVPASTFKMLNALIGLENQKTDINEIFKWKGEKRSFTAWEKDMTLGEAMKLSAVPVYQELARRIGLDLMQKEVKRIGFGNAEIGQQVDNFWLVGPLKVTPIQEVEFVSQLAHTQLPFSEKVQANVKNMLLLEESNGYKIFGKTGWAMDIKPQVGWLTGWVEQPDGKIVAFALNMEMRSEMPASIRNELLMKSLKQLNII |

| OXA-48 family protein | MRVLALSAVFLVASIIGMPAVAKEWQENKSWNAHFTEHKSQGVVVLWNENKQQGFTNNLKRANQAFLPASTFKIPNSLIALDLGVVKDEHQVFKWDGQTRDIAAWNRDHDLITAMKYSVVPVYQEFARQIGEARMSKMLHAFDYGNEDISGNVDSFWLDGGIRISATQQIAFLRKLYHNKLHVSERSQRIVKQAMLTEANGDYIIRAKTGYSTRIEPKIGWWVGWVELDDNVWFFAMNMDMPTSDGLGLRQAITKEVLKQEKIIP |

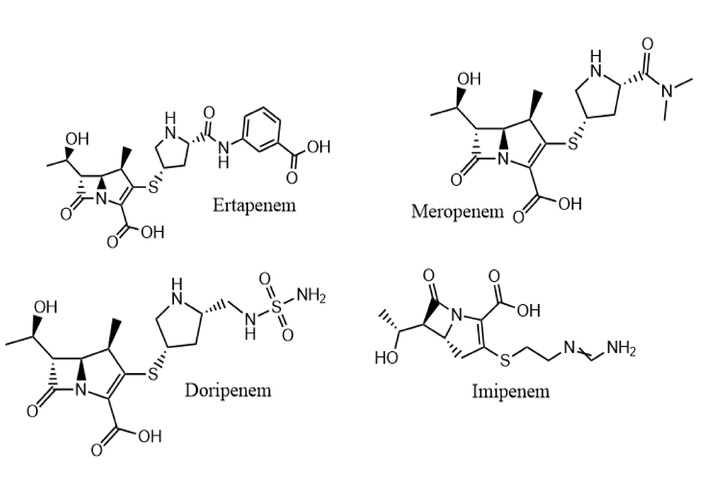

These OXA family genes belong to a group of class D beta-lactamases, known as oxacillinases. These enzymes are clinically significant because they hydrolyse or break down beta-lactam antibiotics, in this case, carbapenems, thus conferring resistance [65]. Their significance is noteworthy because carbapenems are often used to treat infections caused by bacteria resistant to other beta-lactam antibiotics like penicillin and cephalosporins. OXA-23 is primarily found in Acinetobacter baumannii, and OXA-48 is more common in Enterobacterales. While both enzymes hydrolyse carbapenems, they exhibit different substrate profiles. OXA-48 has a higher hydrolytic activity against carbapenems like OXA-23 but a lower activity against antibiotics with bulkier side-chain substituents [66]. Figure 1 shows a structural profile of some clinically approved carbapenems in circulation.

Some clinically approved carbapenems drawn in ChemDraw from PubChem SMILES [67]. Ertapenem (CID 150610) accessed from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/150610; Meropenem (CID 441130) accessed from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/441130; Doripenem (CID 73303) accessed from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/73303; and Imipenem (CID 104838) accessed from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/104838.

In contrast, Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified the presence of the OXA-50 family gene. Although this gene encodes an oxacillinase, it is not typically attributed to hydrolysing carbapenems. It is considered a background resistance determinant and may contribute to MDR when combined with other resistance mechanisms. Using ResFinder v4.7.2 with native protocols, no acquired beta-lactamase genes associated with carbapenem were detected in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome. However, chromosomally encoded resistance determinants related to amoxicillin, ampicillin, cefepime, ceftazidime, fosfomycin, and chloramphenicol were identified. These findings are corroborated by Schäfer et al. (2019) [68] in “molecular surveillance of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa at three medical centres in Cologne, Germany”, who showed that, unlike Acinetobacter baumannii complex or carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, carbapenemases are detected less frequently in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, where susceptibility is mainly mediated by intrinsic mechanisms [68]. Although carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa exists, its distribution is majorly geographical, with prevalence as low as about 2% from the USA and 30–69% from south to central America, China, Singapore, Australia and the middle east drawn from Reyes et al. (2023) [69] in “global epidemiology and clinical outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and associated carbapenemases (POP): a prospective cohort study”.

In CRKP genomes, acquired resistance genes were detected and plasmid replicons identified, including the Col-type (100%), Inc-type (≥ 99.65%), and repB (99.2%), with ColKP3 attributed to carbapenem resistance as blaOXA-181 using PlasmidFinder2.0. However, PlasmidFinder accessed from “Center for Genomic Epidemiology”, did not detect plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae (gram-negative). Using useGalaxy Bakta, the blaOXA-23 gene was detected.

Using NCBI BLASTp, homologous targets 4jf4_A and 4s2j_A were obtained for OXA-23 and OXA-48, respectively, with a pairwise identity of 100% for both sequences to the homologous. However, cross identities for both sequences yielded 49.5% between these classes.

Assessment of the assimilated models places the overall quality factor of 4jf4_A and 4s2j_A at 97.8448% and 100% respectively, using PROCHECK [70], with Ramachandran plots given in Figure 2.

The stereochemical quality of the modelled protein structures represented in the Ramachandran plots gave 100% residues located in favourable and allowed regions with no outliers for 4s2j_A (OXA-48). The 4jf4_A (OXA-23) model showed a slightly lesser quality, with 99.5% of residues in favourable and acceptable regions. These results indicate that the backbone dihedral angles are well within acceptable limits [71], confirming that the models possess accurate secondary structure geometries suitable for downstream computational studies.

The screen consists of 97 pharmacopeial derivatives or by-products of APIs obtained from The British Pharmacopoeia 2024, some of which are known to be active pharmaceutical ingredients, i.e., clinically approved therapeutic ingredients [72] (see Table S1).

A second library of 148 chemogenomic compounds obtained from the Molport compound library was added to evaluate possible inhibition or modulation (see Table S2).

The models of 4jf4_A and 4s2j_A complexed with meropenem and avibactam, respectively, were prepared, and a grid box was generated around the ligands with coordinates (10.67, –5.27, 3.89) Å and (–45.09, –41.78, –14.04) Å, and and edge lengths of 15 Å and 12 Å to encapsulate the binding pocket of the centroid co-crystallised ligand of the protein.

The virtual screening was performed using a scaling factor of 0.80 and a partial charge cutoff of 0.15 under Glide HTVS, SP, XP precision, and a Prime MM-GBSA post-processing to score the top-ranked hits and their respective poses with a screen of 100%, 50%, and 10% respectively.

Under the virtual screening workflow, static interactions between the carbapenemase targets and libraries were assessed in an attempt to find potential inhibitors. The binding affinities are as depicted in Table 5 for the compound-target combinations.

Compound-target binding affinities.

| No. | Compound ID | Target | Classification | Docking score (kcal/mol) | MM-GBSA (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 443939a | 4jf4_A | Pharmacopoeial | –8.952 | –30.93 |

| 30323a | –8.535 | –33.96 | |||

| 11082a | –8.382 | –14.17 | |||

| 2 | 443939a | 4s2j_A | –8.447 | –46.79 | |

| 30323a | –7.598 | –64.57 | |||

| 3 | EUB0000226bb | 4jf4_A | Molport | –8.603 | –54.63 |

| –7.487 | –59.35 | ||||

| 4 | EUB0000226bb | 4s2j_A | –6.468 | –63.48 | |

| –6.457 | –61.82 |

a: PubChem ID; b: EUbOPEN Compound ID. MM-GBSA: molecular mechanics-generalised Born surface area. 443939: doxorubicin hydrochloride; 30323: daunorubicin; 11082: 6-aminopenicillanic acid.

Among the pharmacopoeial compounds, doxorubicin hydrochloride (443939) demonstrated the most favourable docking score against 4jf4_A (–8.952 kcal/mol) and a moderate MM-GBSA binding energy (–30.93 kcal/mol), suggesting an appreciable binding strength and stability. However, daunorubicin (30323) recorded the most negative MM-GBSA value (–33.96 kcal/mol) among the pharmacopoeial group for 4jf4_A, despite a slightly less favourable docking score (–8.535 kcal/mol), indicating a potentially more stable binding interaction post-refinement.

Interestingly, for the 4s2j_A target, the binding energy profile differed. 30323 showed a significant MM-GBSA score (–64.57 kcal/mol), surpassing all other candidates, suggesting a particularly stable interaction, despite its relatively lower docking score (–7.598 kcal/mol). This highlights a recurring observation where MM-GBSA rescoring reveals stronger binding energies than initially suggested docking scores alone, likely due to entropic contributions.

The EUB0000226b ligand consistently displayed strong binding affinities across both targets. For 4jf4_A, it achieved a docking score of –8.603, –7.487 kcal/mol and a highly favourable MM-GBSA score of –54.63, –59.35 kcal/mol, outperforming the pharmacopoeial group. For 4s2j_A, despite lower docking scores (–6.468, –6.457 kcal/mol), the MM-GBSA results (–63.48, –61.82 kcal/mol) indicated very strong and consistent binding stability. This observation underscores EUB0000226b as a promising hit compound with high affinity and structural compatibility towards both targets.

While docking scores prioritise 443939 and 30323 for 4jf4_A, MM-GBSA may suggest EUB0000226b may form thermodynamically favourable complexes with the receptors. Taken together, these findings prioritise EUB0000226b and 30323 as lead candidates for validation as potent inhibitors.

Doxorubicin hydrochloride (443939) and daunorubicin (30323), both anthracycline-based drugs, showed significant MM-GBSA scores. These are known clinically validated classical anticancer drugs with established pharmacological relevance and behaviour [73, 74], which make them ideal reference ligands for evaluating novel interactions and binding potential of EUB0000226b, identified as (2R,3R,4S,5R)-2-(4-amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-7-yl)-5-((S)-hydroxy(phenyl)methyl)tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol.

Emerging evidence reveals that certain anticancer drugs influence bacterial mechanisms. Especially those with cytotoxic effects, these agents can increase the mutation rate, which can accelerate the development of resistance mechanisms, including those that may affect carbapenem resistance [75]. Zhang et al. (2024) [76] attested that 5-fluorouracil, an anticancer agent, reversed the resistance of meropenem in carbapenem-resistant gram-negative pathogens. These organisms included E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter spp. This study corroborates the potential inhibitory or modulatory effect of 443939 and 30323 in Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Figures 3, 4, 5, and 6 show the binding interactions between doxorubicin hydrochloride and daunorubicin.

Although molecular docking provides valuable insights and preliminary estimates, its limitations in accurately capturing receptor flexibility, conformational adaptability, interaction persistence, and solvent effects in a time-resolved environment necessitate further validation through MD simulations [77, 78]. For this reason, we selected the compound EUB0000226b for advanced evaluation due to its high binding stability (MM-GBSA), consistent energetic profile across conformations and targets, and chemical novelty due to its structurally distinct disposition with a Tanimoto coefficient of 0.3119 to avibactam and 0.4661 to meropenem. Existing beta-lactamase inhibitors like clavulanic acid, avibactam, relebactam, and vaborbactam are typically beta-lactam or diazabicyclooctane-based while EUB0000226b features a pyrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine core, suggesting resemblance to a nucleoside analog. This unique scaffold gives a departure from established chemotypes, potentially offering new interaction modes with class D beta-lactamases.

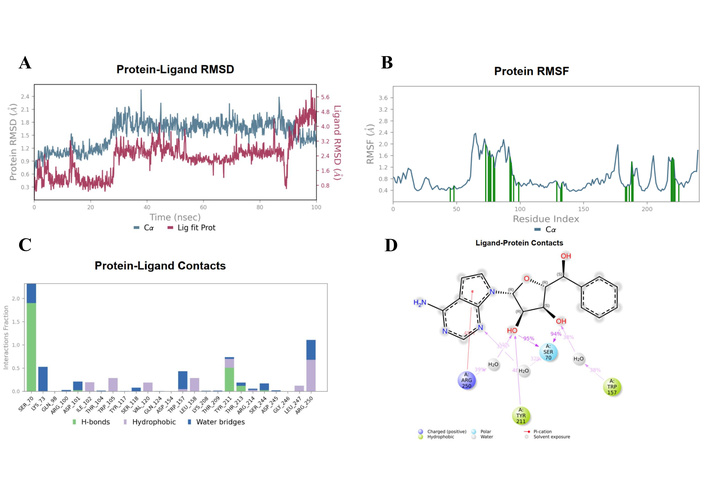

Figure 7 shows the dynamic profile of ligand EUB0000226b. The protein RMSD stabilised at 1.5 ± 0.5 Å after 20 ns, alluding to structural convergence. After 20 ns, the ligand fluctuated between 2.4–5.6 Å, suggestive of instability.

EUB0000226b-4s2j_A dynamic profile. (A) Time evolution of protein and ligand RMSD during the simulation. (B) Per-residue RMSF of the protein backbone, highlighting flexible and rigid regions upon ligand binding. (C) Protein-ligand interaction profile showing the fraction and type of contacts maintained throughout the simulation. (D) Two-dimensional interaction map illustrating key ligand-protein interactions. RMSD: Root Mean Square Deviation; RMSF: Root Mean Square Fluctuation.

However, critical insights (contacts and RMSF) reveal that this stems from ligand flexibility as it remained anchored in the binding pocket with the scaffolds remaining conformationally rigid, as shown in Figure 8. The protein RMSF (Figure 7C) indicated that most residues fluctuated below 1.5 Å, denoting a stable structure. Higher fluctuations were associated with inherent flexibility. Notably, residues (SER70, TYR211, TYR157, and ARG250) showed low to moderate fluctuation, supporting a stable interaction environment during the simulation.

To resolve the ligand RMSD ambiguity, we performed a two-dimensional WTMetaD analysis post hoc using distance-based CVs. The CVs were defined as the distances between SER70 and the ligand centroid atoms 9 and 15, which bracketed the molecular scaffold (Figure 8). WTMetaD was run with a kTemp of 2.4, hill height of 1 kcal/mol, a Gaussian width of 0.3 Å, and an upper wall at 12 Å, under conditions of 300 K and 1.01325 bar using the OPLS4 forcefield. SER70 was selected as a CV anchor due to its spatial relevance and frequent interaction with the ligand (> 90%), as shown in Figures 7C and 7D. Consistent interactions with SER70 were also observed for ligands 30323 and 443939 (Figures 3 and 6).

The FEL as given in Figure 9 along these CVs revealed global minima approximately at 2.7 kcal/mol (CV1 = 3.5–4.5 Å/CV2 = 3.5–5.5 Å, and CV1/CV2 > 9, purple region). This deep energy well corresponds to the fully bound state, where these ligand-atoms remain closely associated with SER70, consistent with persistent interactions observed with unbiased MD. The surrounding sloped valley extends diagonally across the FES, indicating a continuum of metastable states in which one end of the ligand remains anchored while the other undergoes conformational displacement due to flexible rotatable bonds at both ends of the ligand, as shown in Figure 9A (represented as the blue region in Figure 9B). This tracks with partial unbinding or internal reorientation that showed at higher ligand RMSD, and as highlighted in Figure 7D, the presence of a solvent-separated event between the ligand and the interacting amino acids lining the pocket.

The mediation of the solvent-separation interactions in the hydrogen bond was consistent with observations in the unbiased MD, allowing for a longer residence time of the ligand, thereby enhancing contact durability [79, 80]. This interaction stabilises the hydrogen bond network, thereby remaining in the proximity of the pocket, mimicking the real biophysical environment (see Movie S1—WTMetaD video).

To assess the validity of the reconstructed FEL for the phenomena, the evolution of accumulated bias potential for convergence was monitored. The evolution exhibited an initial rapid growth as the complex explored new conformational space, followed by a gradual plateauing after 20 ns with minimal fluctuations, especially after 25 ns, indicating convergence.

The SwissADME was used to assess the druglikeness of EUB0000226b via Lipinski’s rule of pharmacokinetics. Table 6 provides an array of druglikeness metrics of EUB0000226b.

Pharmacokinetic profile of EUB0000226b.

| No. | Parameter | Optimal range | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Size | 150–500 g/mol | 342.35 g/mol |

| 2 | Lipophilicity (consensus) | –0.7 to +5.0 | 0.09 |

| 3 | Polarity | 20 to 130 Å2 | 126.65 Å2 |

| 4 | Water solubility (ESOL) | –6 to 0 | –2.48 (soluble) |

| 5 | Insaturation | 0.25 to 1.0 | 0.29 |

| 6 | Flexibility | 0 to 9 | 3 |

| 7 | Pharmacokinetics | Gastrointestinal (GI) absorption | High |

| Blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeant | No | ||

| P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate | No | ||

| 8 | Druglikeness | Lipinski | Yes, 0 violations |

| Bioavailability score | 0.55 | ||

| 9 | Medicinal chemistry | Synthetic accessibility | 4.20 |

| Leadlikeness | Yes |

The physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of EUB0000226b were evaluated to assess its druglikeness and suitability as a carbapenemase inhibitor. The molecular weight falls within the optimal range for druglike molecules, facilitating efficient permeation across biological membranes. Its consensus lipophilicity of 0.09 suggests a balanced lipophilic-hydrophilic profile, which is advantageous for both passive membrane diffusion and solubility, critical for interacting with the periplasmic bacterial beta-lactamases. The solubility also confirms its amenability to systemic administration through the oral or intravenous route.

The compound possesses an optimal cell permeability (126.65 Å2), which may be beneficial for forming specific hydrogen bonding, marking the degree of polarity. The prediction also revealed high gastrointestinal absorption, which is favourable for oral bioavailability. Its behaviour of not being a P-gp substrate allows for the compound to escape the efflux-mediated resistance mechanism. As a non-blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeant, it reduces the risk of central nervous system-related side effects.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the compound possesses favourable properties, warranting its consideration for lead-like molecules [48].

Protox 3.0 predicted the toxicity of the molecule with a prediction accuracy of 69.26% and an average structural similarity of 75.56%. The molecule was ranked to have a predicted toxicity class II with an LD50 of 11 mg/kg. Class II is characterised by an LD50 of 5–50 mg/kg body weight, typically assessed as fatal if swallowed [49]. The toxicity of EUB0000226b is as given in Table 7.

Toxicity profile of EUB0000226b.

| No. | Target | Classification | Prediction | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hepatotoxicity | Organ toxicity | Inactive | 0.50 |

| 2 | Nephrotoxicity | Organ toxicity | Inactive | 0.63 |

| 3 | Respiratory toxicity | Organ toxicity | Active | 0.82 |

| 4 | Cardiotoxicity | Organ toxicity | Inactive | 0.89 |

| 5 | Immunotoxicity | Toxicity endpoints | Inactive | 0.72 |

| 6 | Carcinogenicity | Toxicity endpoints | Inactive | 0.53 |

| 7 | Mutagenicity | Toxicity endpoints | Inactive | 0.62 |

| 8 | Cytotoxicity | Toxicity endpoints | Inactive | 0.73 |

| 9 | Phosphoprotein (tumour suppressor) p53 | Tox-21-stress response pathways | Inactive | 0.78 |

| 10 | GABA receptor (GABAR) | Molecular initiating events | Inactive | 0.77 |

| 11 | Voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) | Molecular initiating events | Inactive | 0.64 |

The in silico toxicity predictions revealed that EUB0000226b exhibits a favourable safety profile across multiple organ toxicity and molecular endpoints. It was predicted to be inactive for hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, and immunotoxicity with high confidence probabilities (0.50–0.89), where 0 and 1 indicate varying degrees of pre-calculated likelihood of toxicity, with higher values indicating a higher likelihood of the compound exhibiting respective toxic effects [81]. Notably, respiratory toxicity was predicted to be active with high probability, suggesting that potential off-target respiratory effects should be investigated further during preclinical evaluation [46, 82]. No predicted activity against p53 pathway, GABAR, and voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC), further supporting its low risk of central nervous system and pro-arrhythmic liabilities.

To assess the structural and electronic behaviour of EUB0000226b, Density Functional Theory calculations were carried out using Gaussian 09 software. Optimisation calculations ran the valence double zeta polarising basis set, 6-31G* and Becke3-Lee-Yang-Parr, B3LYP in IEFPCM (water) to elucidate the behaviour in implicit solvent.

Table 8 depicts the computed descriptors obtained to provide structural insights into the reactivity of EUB0000226b.

Global reactivity descriptors of EUB0000226b.

| No. | Parameter | Descriptors |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Formation energy | –1,178.43 au |

| 2 | Dipole moment | 9.00 Debye |

| 3 | EHOMO | –5.5427 eV |

| 4 | ELUMO | –1.1848 eV |

| 5 | Energy gap (ΔE) | 4.3579 eV |

| 6 | Electronegativity (χ) | 3.3638 eV |

| 7 | Chemical hardness (η) | 2.1790 eV |

| 8 | Chemical potential (μ) | –3.3638 eV |

| 9 | Electrophilicity (ω) | 2.5960 eV |

| 10 | Softness (S) | 0.2295 eV–1 |

HOMO: highest occupied molecular orbital; LUMO: lowest unoccupied molecular orbital.

Quantum chemical descriptors derived from DFT calculations provided insights into the reactivity and stability of EUB0000226b. The molecule displayed a relatively large HOMO-LUMO gap (ΔE = 4.3579 eV), consistent with good kinetic stability and a low likelihood of nonspecific reactivity. The calculated dipole moment (9.00 Debye) indicated a highly polar compound, favouring solvent interaction and potential interactions with charged or polar residues in the binding site, as seen in both docking and metadynamics. The electronegativity (χ = 3.3638 eV) and electrophilicity index (ω = 2.5960 eV) placed the compound within a reactivity range typical of bioactive molecules [54, 83], supporting its potential as a lead candidate. These findings complement the compound’s favourable ADME, toxicity, and conformational stability profiles observed in previous simulations.

The virtual screening workflow identified daunorubicin, doxorubicin, and EUB0000226b as strong candidates. Among these, EUB0000226b demonstrated the most favourable binding energies and a structurally distinctive profile relative to clinically used beta-lactamase inhibitors. Although EUB0000226b showed elevated ligand RMSD values during MD, the protein backbone remained stable. The RMSD fluctuations reflected the presence of flexible rotatable bonds at both ends of the ligand, which allowed alternative orientations inside the binding pocket rather than complete dissociation.

To clarify these observations, WTMetaD was performed. This approach provided a more detailed understanding of the FEL that governs ligand behaviour. The reconstructed landscape displayed a deep global minimum that represented a fully bound state. A connected sloped valley contained several metastable states in which one region of the ligand remained anchored while other regions adopted different orientations. These states were consistent with the solvent-separated interaction seen in the unbiased MD simulation. Such behaviour suggests that intermittent water-mediated contacts can prolong the residence time of the ligand in the active pocket. Residence time is an important predictor of inhibitory performance.

The convergence of the metadynamics bias potential after approximately 20 to 25 ns indicated that the free energy profile was reliable. Together, these observations show that EUB0000226b can adopt multiple low-energy configurations while maintaining meaningful interactions with key residues.

Pharmacokinetic and toxicity predictions further strengthened the potential of EUB0000226b as a drug-like candidate. The compound demonstrated good gastrointestinal absorption, acceptable physicochemical properties, and compliance with major drug likeness criteria. Toxicity predictions were generally favourable. The only alert involved respiratory toxicity, which should be examined in early in vivo testing.

Quantum chemical descriptors gave additional support for the stability and reactivity profile of the compound. A large HOMO-LUMO energy gap suggested good kinetic stability and a low probability of nonspecific reactivity. The high dipole moment indicated a strong potential for polar interactions with residues in the active site. The calculated electrophilicity and electronegativity values were within typical ranges for bioactive molecules and were consistent with the interaction patterns observed.

The integrated computational approaches used in this study identify EUB0000226b as a promising noncovalent carbapenemase inhibitor. Its binding characteristics, metastable conformations that favour prolonged residence time, and favourable ADME and toxicity predictions indicate strong potential for further optimisation and experimental validation. This compound represents a viable lead for addressing carbapenem-resistant bacterial pathogens and merits additional biological investigation. Although the present study provides valuable insight into the interaction profile and inhibitory potential of EUB0000226b, several limitations should be acknowledged. The work relies exclusively on computational approaches, and the absence of in vitro or in vivo validation means that the predicted inhibitory behaviour remains to be confirmed experimentally. A further limitation is that the simulation time used may not have been sufficiently long to capture the full extent of potential unbinding events, since certain slow dissociation processes require extended sampling to be observed with confidence. Finally, the ADME and toxicity predictions were based on probabilistic computational models, and the flagged respiratory toxicity risk for EUB0000226b requires empirical investigation before firm conclusions can be drawn. In conclusion, the EUB0000226b compound, (2R,3R,4S,5R)-2-(4-amino-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-7-yl)-5-((S)-hydroxy(phenyl)methyl)tetrahydrofuran-3,4-diol, exhibits a pharmacophore with favourable binding energetics, conformational stability, and physicochemical properties against carbapenemase. Quantum chemical descriptors affirm the chemical stability and reactivity of EUB0000226b, and ADME and toxicity models predicted good oral bioavailability and a safety profile, supporting its further development potential, pending respiratory toxicity validation. Together, these in silico findings highlight EUB0000226b as a promising non-covalent lead for drug design in carbapenemase inhibition, meriting in vitro and preclinical confirmation and possible structure-based optimisation.

ABC: ATP-binding cassette

BPPL: Bacterial Priority Pathogens List

CRAB: carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

CRKP: carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae

CVs: collective variables

E. coli: Escherichia coli

FEL: free energy landscape

FES: free energy surface

HOMO: highest occupied molecular orbital

LUMO: lowest unoccupied molecular orbital

MD: molecular dynamics

MDR: multidrug resistance

MM-GBSA: molecular mechanics-generalised Born surface area

P-gp: P-glycoprotein

RMSD: Root Mean Square Deviation

RMSF: Root Mean Square Fluctuation

SRA: Sequence Reads Archive

WTMetaD: Well-Tempered Metadynamics

The supplementary tables for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1008140_sup_1.xlsx and https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1008140_sup_2.xlsx. The supplementary movie for this article is available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1008140_sup_1.mp4.

AOM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Investigation, Writing—original draft. AJA: Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. MEA: Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. SOI: Visualization, Resources, Writing—review & editing. YOA: Software, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Data generated from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 548

Download: 16

Times Cited: 0

Irina Tiganova ... Yulia Romanova

Ebenezer Aborah ... Manuel F. Varela

Daniel Buldain ... Laura Marchetti

Monika I. Konaklieva ... Balbina J. Plotkin