Affiliation:

Department of Clinical Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, Jiangsu Province, China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-8209-2478

Affiliation:

Department of Clinical Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, Jiangsu Province, China

Affiliation:

Department of Clinical Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, Jiangsu Province, China

Affiliation:

Department of Clinical Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, Jiangsu Province, China

Email: zhxh@cpu.edu.cn

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6375-4497

Explor Drug Sci. 2026;4:1008141 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2026.1008141

Received: October 18, 2025 Accepted: December 21, 2025 Published: January 09, 2026

Academic Editor: Fernando Albericio, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, Universidad de Barcelona, Spain

Immunotherapy has transformed oncology, yet has only been marginally effective in prostate cancer (PCa), which is a malignancy with a low mutational load and a highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). This critical review is a reflection on the changing position of the innovative immunotherapies in PCa that extends beyond the description stage to synthesize the synergies and constraints of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, and next-generation modalities such as bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs). We assess the mechanistic reasoning of combination therapies, comprising androgen receptor signaling communicators, PARP communicators, and radioligand therapies, which seek to modulate the immunogenicity of the immune-cold PCa TME. Also, we combine new knowledge to novel resistance pathways, including the newly discovered thrombospondin-1-CD47 axis, in the process of T cell exhaustion through calcineurin-NFAT signaling. Although some preclinical data and initial clinical indicators in biomarker-selected subpopulations are promising, the vast majority of Phase III trials of ICIs in unselected populations with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) have failed. This review reveals that the next generation of PCa immunotherapy would not be sequential monotherapies but rather rationally designed multimodal combinations guided by profound molecular and immune profiling to overcome inherent resistance mechanisms.

Immunotherapy against prostate cancer (PCa) is a daunting challenge. In contrast to immunogenic cancers (like melanoma), PCa is an immune-cold tumor, intrinsically resistant to immunotherapy, which is the basis of the poor checkpoint inhibitor and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy efficacy in this cancer [1].

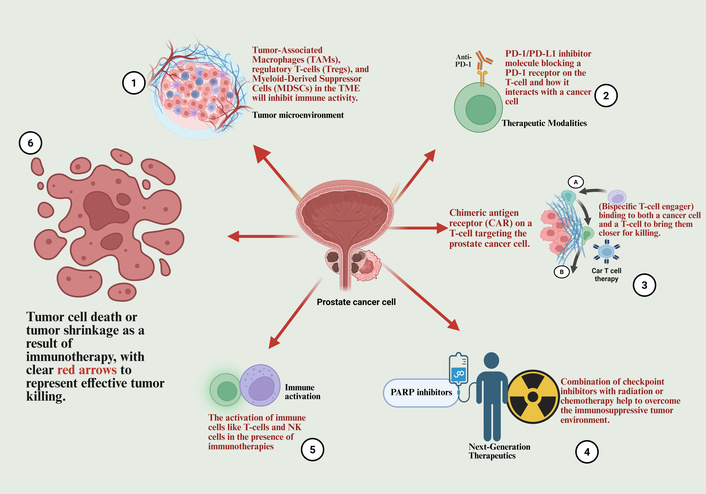

Importantly, PCa presents unique challenges for immunotherapy due to its low mutational burden and limited T cell infiltration [2]. Consequently, these factors contribute to immunological difficulties, since tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) suppress immune activation, reducing the efficacy of therapies like immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [3]. Moreover, the unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway, specifically the IRE1alpha-XBP1s axis, contributes to the creation of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) by supporting the persistence of these suppressive cell types [4]. The immunosuppressive microenvironment and therapeutic strategies are summarized in Figure 1.

Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in prostate cancer. This schematic illustrates the key cellular and molecular mediators that drive immune suppression within the prostate tumor microenvironment. Key immunosuppressive cells—including Tregs, TAMs, MDSCs, Th2 cells, ILC2s, NKT2s, and N2 neutrophils—secrete a repertoire of immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β, IL-13, IL-5, IL-6, CCL28). These cytokines collectively suppress the activation and infiltration of cytotoxic T-cells, facilitating immune evasion and promoting tumor progression. Furthermore, the IRE1alpha-XBP1s signaling axis within the tumor cells is highlighted as a critical pathway that reinforces this immunosuppressive network, further limiting the efficacy of immunotherapeutic interventions. Created in BioRender. Nyame, D. (2026) https://BioRender.com/viu0fez.

Although a few extensive reviews compiled lists of immunotherapeutic agents in PCa [5, 6], this review aims to improve the current conversation by examining specifically the synergistic opportunities of various modalities. We will critically evaluate the rationale of such combinations of checkpoint inhibitors, cellular therapies, and novel agents such as bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) to overcome unique immunological barriers of PCa. This article is not a mere list of trials, but is a prospective view of the integrative rationale of next-generation immunotherapy, whereby a special focus is placed on biomarker-based approaches and TME restructuring.

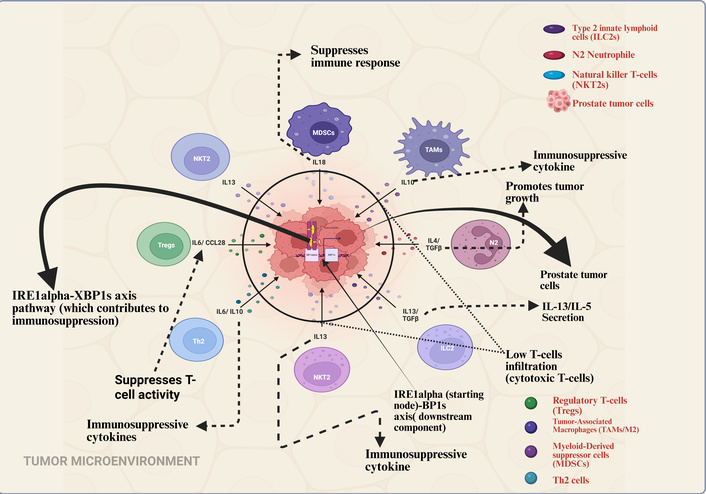

This review goes beyond the listing of immunotherapies and offers a critical analysis of their synergies. We postulate that PCa immune resistance consists of a triad of: (1) low tumor mutational burden (TMB) that results in poor neoantigen presentation [7]; (2) myeloid-dominated TME [8]; and (3) androgen receptor signaling that represses immune gene expression [9, 10]. We state that rational combinations are needed in order to overcome these barriers and remodel the TME. One of the most recent studies by Weng et al. (2025) [11] has shown the thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1)-CD47 signal as a new mediator of T cell exhaustion in cancer, which initiates a calcineurin-NFAT-TOX pathway. The identification of this discovery has shown that there is a mechanism that was previously not considered in the TME that can lead to the dysfunctional state of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in PCa and forms a new vulnerability for therapeutic opportunities. This discovery will be incorporated into the wider scope of PCa immunotherapy in this review, and the most promising directions toward effective patient outcomes will be analyzed. Figure 2 gives a conceptual map of this combinatorial paradigm of how key immunotherapeutic modalities have evolved since the first monotherapies through to current rational combination studies.

Timeline of pivotal clinical trials in prostate cancer immunotherapy (2010–2025). This chronological overview highlights key clinical trials grouped by therapeutic modality in the development of immunotherapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). The illustrated modalities include therapeutic vaccines (e.g., sipuleucel-T), immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., pembrolizumab, nivolumab/ipilimumab), BiTEs, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies, and novel combination regimens. The timeline captures the evolution of treatment strategies, from early vaccine approvals to contemporary investigations into targeted immunotherapies and combinations with other agents like PARP inhibitors. Selected trials are placed according to a significant publication or clinical milestone year (e.g., primary results, regulatory approval. Created in BioRender. Nyame, D. (2026) https://BioRender.com/cdkp2m6.

The breakthrough against these resistances may rely on combined treatment strategies that modify the TME, predict individual-specific antigens, including radiation therapy or PARP inhibitors, to create more immunogenic potential.

In order to achieve a comprehensive, reproducible, and systematic synthesis of the existing landscape, a clear literature search strategy was used. PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus were the main databases that were searched. To achieve the search strategy, a combination of keywords and Boolean operators was used, i.e., prostate cancer OR prostatic neoplasms AND immunotherapy OR immune checkpoint inhibitor OR ICI OR CAR-T-cell OR chimeric antigen receptor OR bispecific T-cell engager OR BiTE OR therapeutic vaccine. To cover the recent period of cancer immunotherapy, articles published since January 2010 until November 2025 in English were searched. Abstracts of major oncology meetings (e.g., ASCO, ESMO, AACR) have been included in the most recent trial outcomes but are specifically mentioned as such. Even the reference lists of the reviewed articles that had been retrieved were hand-searched to detect any other potentially relevant studies. Owing to seminal pre-clinical studies, Phase I–III clinical trials, and meta-analyses directly pertaining to novel immunotherapies of PCa, inclusion criteria were developed. Research papers that were not peer-reviewed (the exception being the mentioned conference abstracts), had non-immunotherapy treatments as a subject of study, and were not published in English were excluded.

The initial significant immunologic resistance in PCa is the non-selective exclusion and functional immobilization of T-cells in the microenvironment around the tumor, a condition that is usually referred to as immune-cold. This non-inflamed landscape has minimal infiltration of T-cells and has high concentrations of suppressive cues that actively suppress cytotoxic functions. ICIs came up as a guiding principle to overcome this particular obstacle by inhibiting inhibitory signals on T-cells, hence, unleashing the brakes on any pre-existing anti-tumor immunity. But such is the very nature of the cold prostate TME that is the main cause of the limited success of such an approach.

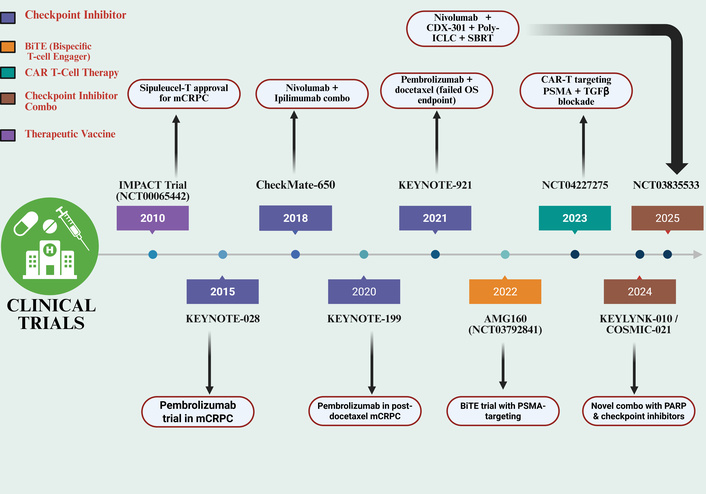

The immune checkpoint pathways, which include CTLA-4 and PD-1, have produced durable clinical responses for multiple cancers. However, the response rates have remained disappointing in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) because the tumors exhibit a low mutational burden, immunosuppressive conditions, and a lack of T-cell infiltrates due to immune evasion [12].

Additionally, checkpoint inhibitors show limited success against PCa because the tumor environment contains few immune cells and many regulatory T-cells (Tregs), which suppress cytotoxicity [13–15]. Using combination therapies that create tumor inflammation through methods like radiation and cryoablation has been found to address this barrier. However, the potential for increased toxicity necessitates careful patient selection and close monitoring. The immune checkpoint pathways targeted by inhibitors in cancer immunotherapy are illustrated in Figure 3.

Mechanism of action of immune checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and ipilimumab. Nivolumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, blocks the interaction between the PD-1 receptor on T-cells and PD-L1 on tumor cells. This prevents the PD-1 pathway from suppressing T-cell activity, thereby enhancing T-cell-mediated tumor cell killing. Ipilimumab, a CTLA-4 inhibitor, blocks the interaction between CTLA-4 on T-cells and B7 molecules on APCs. This prevents an early inhibitory signal, promoting T-cell activation and priming. Together, these checkpoint inhibitors facilitate a more robust anti-tumor immune response by overcoming key mechanisms of tumor immune evasion. Created in BioRender. Nyame, D. (2026) https://BioRender.com/db5f3sx.

In addition, resistance could go beyond PD-1 and CTLA-4; new pathways such as TSP-1-CD47, which induce T cell exhaustion via calcineurin-NFAT signaling, are new avenues that promote the dysfunctional T cell state in the PCa TME and have not been exploited therapeutically [11].

This has limited efficacy that is supported by clinical evidence. Initial PD-1-based trials (e.g., KEYNOTE-028, KEYNOTE-199) showed objective response rates (ORRs) of 3–17% in mCRPC with limited activity being observed primarily in biomarker-enriched populations, e.g., patients with DNA damage response (DDR) deficiencies or high PD-L1-expression [16–18]. Equally, Phase III clinical trials of the CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab (CA184-043, CA184-095) did not extend overall survival as compared to placebo, even with plans to precondition the TME with radiation [19–21]. These findings demonstrate the inadequacy of targeting a single pathway of the checkpoint in an unselected, immune-cold population.

This has led to the exploration of ICI combinations, although with varying success. ICIs’ Phases III trials with androgen receptor pathway inhibitors (e.g., KEYNOTE-641 with enzalutamide, IMbassador250 with atezolizumab) or chemotherapy (e.g., KEYNOTE-921, CheckMate-7DX) have all failed their overall survival endpoints [22–25]. These setbacks imply that merely the introduction of an ICI to conventional-of-care agents is not enough to conquer the excessive immunosuppression in mCRPC and could even lead to unexpected antagonism. Highly selected populations are therefore the major success of ICIs in PCa to date. High TMB, microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H), or mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) tumors, although only a small minority, are of great benefit to patients, prompting the tumor-agnostic approval of pembrolizumab [26–29]. Such a remarkable difference between failure in unselected populations and success in biomarker-defined subgroups demonstrates in a critically important manner the non-redundancy of immune resistance to PCa and the need for predictive biomarkers. The key design parameters and efficacy outcomes of these pivotal Phase III trials are detailed in Table 1. Despite preclinical rationale, Phase III trials of ICIs as monotherapy in unselected mCRPC populations have largely failed to demonstrate a significant overall survival benefit. This Table outlines the design and outcomes of these pivotal studies, informing future combination strategies and patient selection.

Analysis of pivotal Phase III immunotherapy trials in mCRPC: efficacy outcomes and future implications.

| NCT number | Trial name | Phase | Description | Updated results | Key insight & implication for future development | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NCT00861614 | CA184-043 | III | Ipilimumab + RT vs. placebo + RT in mCRPC | Median OS: 11.5 months vs. 10.3 months. HR: 0.88, p = 0.049 | The narrow survival benefit, which barely missed statistical significance, suggests CTLA-4 inhibition may only be effective in a subset with more favorable prognoses (e.g., no visceral disease, normal ALP). Future efforts require robust biomarkers for patient selection. | [19] |

| 2 | NCT01057810 | CA184-095 | III | Ipilimumab vs. placebo in mCRPC | Median OS: 29.1 months vs. 28.0 months. HR: 1.09, p = 0.34 | Lack of efficacy in an earlier-line, less heavily pretreated population indicates that a mere “cold” TME is not the only barrier. Intrinsic resistance mechanisms or the immunosuppressive role of continuous androgen signaling may need concurrent targeting. | [19] |

| 3 | NCT02312557 | Single-Arm Phase II Study | II | Pembrolizumab + enzalutamide in mCRPC progressing on enzalutamide alone | Primary endpoint (ORR): Limited activity observed in this biomarker-unselected, post-enzalutamide population | Demonstrated that PD-1 inhibition after ARSI progression has minimal efficacy without patient selection, highlighting the need for biomarkers and questioning combination timing. | [15] |

| 4 | NCT03834519 | KEYLYNK-010 | III | Pembrolizumab + olaparib vs. NHA in mCRPC | Median OS: 16.0 months vs. 14.7 months. HR: 0.95, p = 0.24 | The failure in a biomarker-unselected population confirms that the immunogenic potential of PARP inhibition is likely restricted to tumors with HRR deficiencies. Future trials must be strictly biomarker-driven. | [30] |

| 5 | NCT03834506 | Keynote-921 | III | Pembrolizumab + docetaxel vs. docetaxel in mCRPC | Median OS: 20.1 months vs. 18.9 months. HR: 0.89, p = 0.15 | Unlike in NSCLC, chemo-immunotherapy synergy is not universal. In mCRPC, docetaxel may not induce sufficient immunogenic cell death or may concurrently deplete immune cells, negating the benefit of PD-1 blockade. | [31] |

| 6 | NCT03016312 | IMbassador250 | III | Atezolizumab + enzalutamide vs. placebo + enzalutamide in mCRPC | Median OS: 15.8 months vs. 16.7 months. HR: 1.14, p = 0.21 | The trend toward worse survival in the combination arm raises a critical safety flag. It suggests the potential for antagonism between PD-L1/PD-1 blockade and enzalutamide, necessitating a deeper investigation into their interplay on the immune landscape. | [32] |

| 7 | NCT03338790 | CheckMate 9KD (Cohort B) | II | Nivolumab + docetaxel in chemotherapy-naive mCRPC | Primary endpoint (ORR): Encouraging anti-tumor activity and acceptable safety, warranting further investigation. | This Phase II signal contrasted with subsequent Phase III failures, suggesting chemotherapy combination efficacy may be context-dependent and not sufficient as a broad strategy in mCRPC. | [33] |

NCT: National Clinical Trial; NHA: next-generation hormonal agent monotherapy; OS: overall survival; ORR: objective response rate; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; RT: radiotherapy; ARSIs: androgen receptor signaling inhibitors; HR: hazard ratio; TME: tumor microenvironment; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; HRR: homologous recombination repair. Adapted from Meng et al. [6] with added critical analysis (CC-BY).

These collective failures of the checkpoint blockade have driven the construction of alternative therapies that are much more specific and actively engineer the immune responses of this anti-tumor cell surveillance, including CAR T-cell therapy. Additionally, pembrolizumab led to PSA50 reductions [defined as a ≥ 50% decline in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels] in 53% of MSI-H mCRPC patients, although the small sample size limits the generalizability of these findings [34].

The TME in PCa is typically complex and heterogeneous and might result in resistance towards single-agent immunotherapies. Tumors use several mechanisms, which are overlapping and redundant to avoid immune surveillance, which comprise T cell exhaustion, activation of other checkpoints, recruitment of immunosuppressive cells, and the loss of target antigen expression. As a result, the unimodal option is often not effective in producing long-lasting clinical effects. Consequently, the future of immuno-oncology lies in rationally designed multimodal strategies that can inhibit various stages of the cancer-immunity cycle at once. It may include the integration of immunotherapies with complementary modalities of action (e.g., BiTEs and checkpoint inhibitors) or sequencing them with established treatment modalities (e.g., chemotherapy, radiation, or androgen receptor pathway inhibitors) to precondition the TME, counter resistance, and enhance the anti-tumor immune response.

Cancer vaccines represent a specialized treatment paradigm designed to induce robust tumor-reactive CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses to antigens associated with PCa [35]. An illustrative example of this is sipuleucel-T, a personalized dendritic cell vaccine that pairs prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). The Phase III IMPACT trial (NCT00065442) demonstrated that sipuleucel-T significantly improved overall survival in patients having asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic metastatic castration-resistant PCa compared to a control group, leading to FDA approval in 2010 [36].

Biomarker studies have shown that sipuleucel-T is associated with accelerated systemic immune responses and antigen dissemination, correlating with extended overall survival [37].

Moreover, research groups have explored peptide- and virus-based vaccine platforms in addition to dendritic cell-based approaches through early-stage clinical trials for PCa development [38–40]. While the available evidence shows immune activation, clinical outcomes, and stability remain elusive as well as most procedural uses fall under the investigational category. A notable example is a vaccine targeting Rho-related GTPase C, which has shown the ability to induce a prolonged T-cell immune response in a substantial group of patients following radical prostatectomy in trial NCT03199872 [41]. These developments highlight the ongoing promise of immunotherapy approaches in treating PCa.

The strategy of developing DNA and RNA vaccines offers emerging potential for PCa immunotherapy, which focuses on the antigens PSA and PAP [38]. Recombinant DNA vaccines producing human PAP underwent early-phase clinical trial evaluation (NCT04090528) that showed immune response activation among specific patients. The current clinical benefits of these approaches are restricted because more research is required with biomarker-based individual treatment approaches [42]. A comparative analysis of the composition, mechanism, and clinical status of leading therapeutic vaccine platforms is provided in Table 2. This Table compares the composition, mechanism of action, and antigenic targets of leading therapeutic vaccine platforms, including dendritic cell, viral vector, and DNA/RNA-based vaccines, evaluated in advanced PCa, contextualizing their clinical development status.

Analysis of therapeutic vaccine platforms in advanced prostate cancer: mechanisms and clinical context.

| Vaccine name | Trial phase | NCT number | Biomarkers/Target | Description | Sponsor | Mechanistic insight & developmental context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sipuleucel-T | Phase III (led to FDA approval) | NCT00065442 | PAP | A dendritic cell vaccine that primes the immune system to target prostate cancer cells expressing PAP. | Dendreon Pharmaceuticals | First-in-class cellular immunotherapy. Demonstrates that activating the immune system against a single, non-mutated self-antigen (PAP) can yield a survival benefit, though its modest effect size highlights the challenge of breaking immune tolerance. |

| RhoC anticancer vaccine | Phase I/II | NCT03199872 | RhoC (Rho family GTPase) | RhoC-targeted vaccine to stimulate T-cell immunity against cancer. | RhoVac APS | Targets RhoC, a protein involved in cancer metastasis. Represents a strategy to prevent recurrence by targeting a driver of progression, moving beyond targets like PSA/PAP. |

| PROSTVAC-V/F + GM-CSF | Phase III | NCT01322490 | PSA | A poxvirus-based vaccine designed to activate an immune response against prostate cancer cells. | Bavarian Nordic | Despite strong immunogenicity and positive early-phase results, this well-designed poxviral vaccine failed in Phase III, underscoring the difficulty of achieving clinical efficacy with vaccine monotherapy in advanced, immunosuppressive mCRPC. |

| PAP plus GM-CSF | Phase II | NCT01341652 | PAP | Peptide vaccine with GM-CSF for immune boost. | University of Wisconsin, Madison | Highlights the importance of patient selection; efficacy may be confined to a specific, more immunologically responsive disease state (e.g., rapid PSA-DT indicating higher disease burden/antigen exposure). |

| DC vaccine with tumor mRNA | Phase I/II | NCT01197625 | Tumor-associated antigens | A personalized dendritic cell vaccine using mRNA from individual tumors to enhance immune response. | Oslo University Hospital | A highly personalized approach that bypasses the need for predefined tumor antigens. It leverages the full spectrum of a patient’s tumor mutations to generate a polyclonal T-cell response, though manufacturing complexity is a barrier. |

| Prodencel | Phase I | NCT05533203 | Tumor-associated antigens | A therapeutic vaccine using dendritic cells to prime the immune system against prostate. | Shanghai Humantech Biotechnology Co. Ltd | Represents the continued development of the autologous dendritic cell platform pioneered by sipuleucel-T, exploring its application with potentially different antigen-loading or maturation protocols. |

| GVAX® prostate cancer vaccine | Phase III | NCT01436968 | PSMA | Vaccine based on oncolytic viruses combined with radiation therapy to target prostate cancer cells. | Candela Therapeutics, Inc. | Combines in situ vaccination (oncolytic virus lysing cells and releasing antigens) with standard radiotherapy. The goal is to convert the tumor into an immunogenic hub, a strategy distinct from pre-manufactured vaccines. |

| TENDU vaccine | Phase I | NCT04701021 | Tumor-specific neoantigens | A personalized DNA neoantigen vaccine for patients post-prostatectomy (status: Completed). | Ultimovacs ASA | A neoantigen-targeting DNA vaccine. This represents the cutting edge of vaccine technology, aiming to elicit responses against truly tumor-specific mutations (neoantigens) to avoid tolerance and maximize safety. |

NCT: National Clinical Trial; DC: dendritic cell; GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PAP: prostatic acid phosphatase; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; PSMA: prostate-specific membrane antigen; PSA-DT: PSA doubling time. Adapted from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ and Meng et al. [6] (CC-BY).

Ultimately, although cancer vaccines are a conceptually feasible approach to priming anti-tumor immunity, their clinical effect outside sipuleucel-T has been generally poor. The unsuccessful results of PROSTVAC highlight the fact that the development of potent de novo T-cell responses within advanced, immunosuppressive mCRPC is difficult. It is probable that future success will be based on the ability to target neoantigens, integrate vaccines with powerful immune modulators (including checkpoint inhibitors), and use them in minimal residual disease domains.

Studies are devoted to the development of new methods of improving the treatment of PCa by using immunotherapy in conjunction with other types of therapy. Combination Clinical trials are examining the use of checkpoint inhibitors with other modalities to enhance immune activation since monotherapy of checkpoint inhibitors has limited efficacy in PCa. The major plans underway in multimodal immunotherapy of PCa include:

The synergistic immunotherapies are being tested in numerous combinations of immunotherapeutic agents with complementary mechanisms of action (e.g., vaccines to prime the responses, then checkpoint inhibitors to sustain the responses).

The fundamental scientific rationales and biological hypotheses under investigation in new checkpoint-based combination approaches are summarized in Table 3. This table details novel combination strategies that pair ICIs with other therapeutic classes in metastatic PCa. It outlines the scientific rationale for each approach, the specific biological hypothesis being tested (e.g., overcoming T-cell exhaustion, modulating the TME, targeting alternative immunosuppressive pathways), and the resulting clinical implications.

Analysis of novel immune checkpoint inhibitor combination strategies in metastatic prostate cancer: rationale and scientific hypotheses.

| Combination agents | Mechanism | Clinical phase | Trial ID | Indication | Primary endpoints | Scientific hypothesis & rationale for combination | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ipilimumab + nivolumab | Dual checkpoint blockade | II | NCT02985957 (CHECKMATE-650) | Metastatic CRPC | ORR and rPFS | Hypothesis: Concurrent CTLA-4 (priming) and PD-1 (effector) blockade can overcome the “cold” TME of mCRPC by promoting deeper T-cell infiltration and sustained activation, where single-agent therapy fails. | [43] |

| Ipilimumab + GVAX | Vaccination + immunotherapy | I | NCT01510288 | Metastatic CRPC | AE | Hypothesis: The GVAX vaccine provides a broad antigen source to prime and expand tumor-specific T-cells, which are then protected from exhaustion and inhibition by CTLA-4 blockade, creating a synergistic immune cycle. | [44] |

| Ipilimumab + nivolumab | Dual checkpoint blockade | II | NCT02601014 (STARVE-PC) | Metastatic CRPC with detectable AR-V7 transcript | PSA response | Hypothesis: AR-V7 positive tumors represent a more aggressive, treatment-resistant disease state that may harbor a distinct immune contexture, potentially making it more susceptible to intense dual immune checkpoint blockade. | [45] |

| Ipilimumab + nivolumab | Dual checkpoint blockade | II | NCT03061539 (NEPTUNES) | Metastatic CRPC with TMB | CRR | Hypothesis: High TMB generates more neoantigens, creating an intrinsically “hotter” TME. This pre-existing immune infiltration is predicted to be highly responsive to the powerful amplification provided by dual checkpoint inhibition. | [46] |

| Pembrolizumab + enzalutamide | Checkpoint blockade + ADT | 1b/II | NCT02861573 (KEYNOTE-365) | Metastatic CRPC | AE, PSA response, ORR | Hypothesis: Androgen receptor signaling inhibition can remodel the immunosuppressive TME and delay T-cell exhaustion. Combining it with PD-1 blockade may simultaneously remove suppressive signals (androgen & PD-1) to unleash a more potent anti-tumor response. | [47] |

| Pembrolizumab + enzalutamide | Checkpoint blockade + ADT | III | NCT03834493 (KEYNOTE-641) | Metastatic CRPC | OS and rPFS | Hypothesis: In a broad mCRPC population, the TME-remodeling effects of enzalutamide will convert a sufficient number of “cold” tumors to “hot”, allowing them to respond to PD-1 inhibition and thereby demonstrating a survival benefit at the population level (this primary hypothesis was not confirmed). | [48] |

| Nivolumab + CDX-301 + Poly-ICLC + SBRT | Immune activation + checkpoint + radiotherapy | I | NCT03835533 (PORTER) | Metastatic CRPC | CRR, 6-month DCR, rPFS, OS | Hypothesis: A multi-pronged “immunogenic primer” regimen—SBRT (in-situ vaccination), CDX-301 (dendritic cell expansion), and Poly-ICLC (TLR3 agonist)—will create a robust, inflamed TME that is then maintained and amplified by PD-1 blockade (nivolumab), overcoming profound immune ignorance. | [49] |

CRPC: castration-resistant prostate cancer; ORR: objective response rate; rPFS: radiographic progression-free survival; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; AE: adverse event; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; AR-V7: androgen receptor splice variant 7; TMB: tumor mutational burden; CRR: composite response rate; ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; OS: overall survival; DCR: disease control rate; SBRT: stereotactic body radiotherapy; Poly-ICLC: polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid stabilized with poly-L-lysine and carboxymethylcellulose; CDX-301: Flt3 ligand; TME: tumor microenvironment; TLR3: Toll-like receptor 3. Adapted from Meng et al. [6] and Kim & Koo [5] with added strategic analysis (CC-BY).

The combination of immunotherapies is undergoing clinical trials in many combinations of agents with complementary mechanisms of action (e.g., vaccines to prime the responses, followed by checkpoint inhibitors to maintain the responses). The main current research, its scientific basis, and the stage of disease are presented in Table 4. Table 3 summarizes the fundamental scientific arguments and biological hypotheses under investigation in these new combination strategies, which are checkpoint-based. On the basis of these reasons, Table 4 gives a syntactic perspective of the key clinical research initiatives, including the individual agents, disease phase, and trial numbers of such combination therapies. This table outlines rational combination immunotherapy strategies, detailing the scientific premise for synergy between agents (e.g., checkpoint inhibitors with vaccines, BiTEs with cytokines) and their current or proposed application across different stages of PCa, from localized to metastatic disease.

Analysis of rational combination immunotherapy strategies in prostate cancer: scientific premise and disease stage.

| NCT number | Phase | Description | Combination rationale & scientific premise | Disease stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03532217 | I | Neoantigen DNA vaccine in combination with nivolumab/ipilimumab and PROSTVAC in hormone-sensitive mCRPC | “Prime, expand, sustain”: Neoantigen & PROSTVAC vaccines prime diverse T-cell clones; dual checkpoint blockade (Ipi/Nivo) expands and sustains their activity, creating a powerful, multi-pronged immune attack. | Metastatic (mCRPC) |

| NCT02649855 | II | Docetaxel and PROSTVAC for mCRPC | Sequential modality: Tests if chemotherapy-induced immunogenic cell death provides an antigen source to enhance the efficacy of a subsequent vaccine, or if concurrent administration is feasible and synergistic. | Metastatic (mCRPC) |

| NCT02325557 | I/II | ADXS31-142 alone and in combination with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors | Innate + adaptive activation: Attenuated Listeria induces potent innate immunity and delivers tumor antigens (e.g., PSA). Checkpoint inhibitors prevent exhaustion of the activated T-cells, aiming to convert a strong immune response into a clinical benefit. | Metastatic (mCRPC) |

| NCT04382898 | I/II | PRO-MERIT in mCRPC | mRNA precision + checkpoint blockade: An mRNA vaccine encoding multiple prostate-associated antigens (PAP, PSA, PSMA, etc.) precisely directs the immune response. Combined with PD-1 blockade to overcome the adaptive resistance that often follows vaccination. | Metastatic (mCRPC) |

| NCT04989946 | I/II | ADT, +/– pTVG-AR, and +/– nivolumab in newly diagnosed, high-risk prostate cancer | Early intervention & AR targeting: Tests a “chemo-free” immuno-hormonal combination in high-risk localized disease. ADT remodels the TME; an AR-targeting vaccine primes anti-tumor immunity; and nivolumab prevents T-cell exhaustion, aiming for curative-intent synergy. | High-risk localized |

| NCT04090528 | II | PIVG-HP DNA vaccine, +/– pTVG-AR DNA vaccine, and pembrolizumab in mCRPC | Dual-antigen vaccination + checkpoint blockade: Combines vaccination against two key prostate antigens (PAP and AR) to broaden immune targeting, supported by PD-1 inhibition to maintain the functionality of the activated T-cell pools. | Metastatic (mCRPC) |

| NCT03600350 | II | pTVG-HP and nivolumab in non-metastatic PSA-recurrent prostate cancer | Early biochemical recurrence: Intervenes at a minimal disease state where the immune system is likely more competent. Aims to delay metastatic progression by inducing anti-PAP immunity and blocking its eventual exhaustion. | Non-metastatic (BCR) |

| NCT03315871 | II | Combination immunotherapy in biochemically recurrent prostate cancer (CRPC) | Platform for early intervention: A biomarker-driven umbrella study testing various immunotherapies in BCR, recognizing this as a critical window to eradicate micrometastatic disease before the TME becomes overwhelmingly immunosuppressive. | Non-metastatic (BCR) |

NCT: National Clinical Trial; ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; AR: androgen receptor; BCR: biochemical recurrence; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PAP: prostatic acid phosphatase; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; TME: tumor microenvironment. Adapted from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ and Meng et al [6] (CC-BY).

BiTEs are a powerful and off-the-shelf type of immunotherapy that bridges cytotoxic T-cells to tumor cells without regard to the restriction of MHC. These engineered antibodies normally have two binding domains, one of which binds a T-cell surface receptor (usually CD3) and the other binds a tumor-associated antigen (TAA), which is forced to form a cytolytic immune synapse [50–53]. Such a direct-targeting mechanism has theoretical benefits compared to checkpoint inhibitors in the immune-cold TME of PCa.

The most developed clinical candidates are those that are anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). There is evidence of PSMA × CD3 BiTEs in an early-phase trial (e.g., AMG160): preliminary evidence of proof-of-concept has been obtained with a pronounced fraction of patients experiencing > 50% PSA reductions and circulating tumor cell clearance [54–58]. Nonetheless, a strong efficacy is associated with the high prices of serious and class-altering toxicities, which pose a significant problem to clinical translation. The most common is cytokine release syndrome (CRS), which arises in most patients and often progresses to grade 3 and more severe reactions in a significant proportion of the patients (e.g., 25 percent in one AMG160 cohort), often requiring inpatient care to monitor and manage [54, 55, 59, 60]. The IL-6 receptor blocker tocilizumab prophylaxis is not always sufficient, and CRS persists in the majority of patients, which points to the challenges in fully avoiding this on-target effect [61–63]. Moreover, regarding CRS, the toxicity profile of BiTEs is changing to a broader range of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which resemble those produced by checkpoint inhibitors, including gastrointestinal toxicity, cutaneous toxicity, and endocrine toxicity, suggesting a broad immune activation [64, 65]. The complicated safety profile highlights the fact that BiTE therapy involves complex clinical infrastructure and protocols that may restrain its use across the board and create a major impediment to its use in standard practice. Next-generation T-cell engagers are considering a number of strategies to enhance the therapeutic window. These involve the ability to target other antigens to be able to overcome heterogeneity and escape, including STEAP1 (e.g., AMG509), PSCA, and kallikrein 2 (KLK2) [52, 60, 66]. One of the most promising candidates is AMG509 (STEAP1 × CD3), which showed a significant response in mCRPC with an apparently more convenient safety profile, which led to the start of a pivotal Phase III study [67–69]. Additional advances are engineered costimulation (e.g., CD28 engagement), subcutaneous delivery, and recruitment of other immune cells (such as gamma-delta T cells) [70, 71].

Irrespective of these developments, there are still great obstacles. The low half-life of early BiTE preparations requires continuous infusion, which prompts work on half-life prolonged and sustained-release preparations [72–74]. Moreover, antigen-loss is one of the central resistance mechanisms, like other types of immunotherapies, and the entire repertoire of irAEs continues to be defined [52, 75, 76]. To determine the clinical usefulness of BiTEs in the future, it is likely that these engineering capabilities should be optimized, the biomarkers that predict best should be understood, and they should be rationally used with other modalities to maintain T-cells and overcome an adaptive immunosuppressive reaction. Table 5 summarizes the most important engineering characteristics, target profiles, and clinical status of next-generation BiTE platforms under development. This table catalogs the next-generation BiTEs in development for metastatic PCa, detailing their structural engineering innovations—such as extended half-life, conditional activation, or costimulatory domains—alongside their target antigen pairs and current clinical status.

Analysis of next-generation BiTEs in metastatic prostate cancer: engineering innovations and target profiles.

| NCT number | Phase | Sponsor | Recruitment status | Description | Unique feature/Strategic advantage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NCT04104607 | I | University Hospital Tuebingen | Recruiting | Anti-PSMA × CD3 CC-1 | A foundational PSMA × CD3 construct used to establish safety profiles and manage CRS with IL-6 blockade prophylaxis, providing a benchmark for next-generation molecules. |

| 2 | NCT04221542 | I | Amgen | Recruiting | AMG 509/anti-STEAP1 × CD3 | Pivots to STEAP1, an antigen highly expressed in mCRPC, to overcome tumor heterogeneity and potential resistance to PSMA-targeted therapies. A leading candidate with a dedicated Phase III program. |

| 3 | NCT04702737 | I | Amgen | Completed | AMG 757/anti-DLL3 × CD3 | Targets DLL3, a key marker for NEPC, addressing a highly aggressive, treatment-resistant subtype with limited options. |

| 4 | NCT05125016 | I/II | Regeneron Pharmaceuticals | Recruiting | REGN4336/anti-PSMA × CD28 + cemiplimab | Dual-costimulatory strategy: Engages CD28 for potent “Signal 2” T-cell activation alongside CD3 (“Signal 1”), and is rationally combined with a PD-1 inhibitor to prevent subsequent exhaustion. |

| 5 | NCT04740034 | I | Amgen | Terminated | AMG 340 anti-PSMA × CD3 | Developed as a next-generation anti-PSMA BiTE, likely incorporating optimizations in affinity, stability, or manufacturing over earlier constructs like AMG 160. |

| 6 | NCT04898634 | I | Janssen Research & Development | Recruiting | JNJ-78278343 anti KLK2 | Explores KLK2 as a novel target, diversifying the antigen landscape beyond PSMA and STEAP1. Features subcutaneous administration, a significant improvement in patient convenience over IV infusion. |

| 7 | NCT05369000 | I | Lava Therapeutics | Terminated | LAVA-1207 anti-PSMA × γδ | Innovative mechanism: Engages Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, which have inherent tumor-homing and MHC-independent cytotoxicity, potentially offering a safer and more effective alternative to αβ T-cell redirection. |

| 8 | NCT06691984 | III | Amgen | Recruiting | Bispecific STEAP1 × CD3 TCE | This pivotal Phase III trial positions STEAP1-targeting BiTEs as a potential new standard of care in mCRPC, directly testing their efficacy against established therapies like cabazitaxel. |

NCT: National Clinical Trial; BiTEs: bispecific T-cell engagers; CRS: cytokine release syndrome; DLL3: delta-like ligand 3; KLK2: kallikrein 2; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; NEPC: neuroendocrine prostate cancer; SMA: prostate-specific membrane antigen; STEAP1: six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 1; TCE: T-cell engager. Adapted from Meng et al. [6] with added technical and strategic analysis (CC-BY).

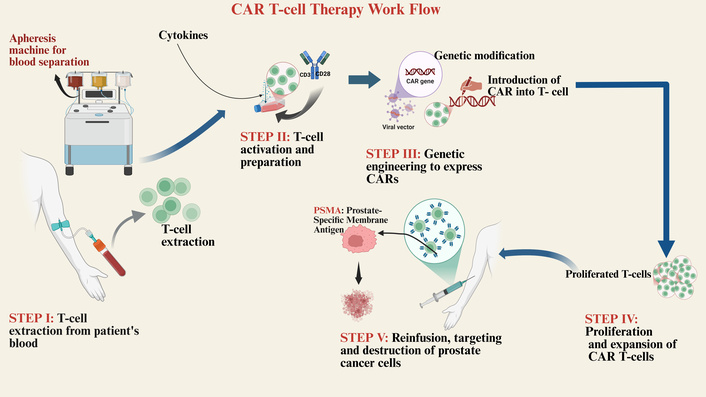

CAR T-cell therapy represents a paradigm in cancer practice, and the use of a pharmaceutical agent is replaced by the delivery of a living drug. The process is genetically engineered to create synthetic T-lymphocytes of a patient, which express an antibody antigen-binding domain with a powerful T-cell signaling complex. This will allow independence of MHC recognition and destruction of tumor cells, which may overcome a major shortcoming of immunotherapy of PCa. Figure 4 shows a stepwise production and therapeutic process of the generation of autologous PSMA-targeted CAR T-cells.

Workflow for the production and administration of CAR T-cell therapy in prostate cancer. The process begins with the extraction of T-cells from a patient via leukapheresis (Step I). The isolated T-cells are activated and genetically engineered ex vivo to express chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) specific for the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) (Steps II–III). Following expansion to sufficient numbers (Step IV), the functional CAR T-cells are reinfused into the patient (Step V), where they recognize, target, and destroy PSMA-expressing tumor cells. Created in BioRender. Nyame, D. (2026) https://BioRender.com/g4mwyem.

Preclinical development has aimed at overcoming both the barriers of the immunosuppressive prostate TME and tumor antigen heterogeneity. The most important strategies are to arm CAR-T cells to overcome the suppressive effect, which can be done by incorporating dominant-negative TGF-β receptors (e.g., in PSMA and STEAP2-targeting CARs) or by using IL-12 to stimulate local cytokine production (e.g., by incorporating IL-12-promoters) [77–81]. The heterogeneity should be overcome by using multiple antigens (e.g., PSMA, PSCA, STEAP1) and optimizing costimulatory domains (e.g., 4-1BB to enable persistence) [80, 82–84]. Although these genetically engineered cells have resulted in improved activity of murine models, the challenge is in translating these cells into consistent clinical activity.

Preclinical trials, which are an early phase CAR-T in mCRPC, have provided a disheartening experience. Although there have been exceptional cases of profound (> 98%) PSA responses (biologic proof-of-concept), the responses have been associated with severe, potentially fatal, toxicities such as CRS and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) [77, 85, 86]. The clinical experience has highlighted the non-negotiable conditions of success, and lymphodepleting chemotherapy is essential to facilitate engraftment, according to this argument, and there is a narrow therapeutic index that prevails with current constructs [87–89]. These shortcomings of the initial generation of CAR-T cells and their ability to persist effectively in this solid tumor model underscore the significantly high barrier of the TME, which explains why the armored designs currently under preclinical trials are needed. Table 6 gives an overview of major clinical trials and their designed characteristics. This table catalogs advanced engineering strategies for CAR T-cells being developed for advanced PCa. It details specific modifications—such as cytokine armoring, dominant-negative receptors, and logic-gated targeting—designed to overcome key barriers in the hostile TME, including immunosuppression, antigen heterogeneity, and metabolic constraints.

Analysis of CAR T-cell therapy engineering strategies in advanced prostate cancer: innovations to overcome the hostile TME.

| NCT number | Phase | Sponsor | Recruitment status | Description | Engineering innovation/Armoring strategy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NCT01140373 | I | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | Active, not recruiting | Adoptive transfer of autologous T cells targeted to PSMA in mCRPC | A foundational, first-generation PSMA CAR-T study that established early proof-of-concept and safety benchmarks for the field. |

| 2 | NCT04633148 | I | AvenCell Europe GmbH | Terminated | UniCAR02-T cells and PSMA target module in mCRPC with progressive disease after systemic therapy | Modular “universal” CAR-T system. The CAR-T cells are inert until a soluble PSMA-targeting module is administered, allowing for precise, on-demand control of CAR-T activity to manage toxicity. |

| 3 | NCT04222725 | I/II | Tarsier Pharma | Completed | CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN in mCRPC | Armored CAR-T design. Co-expression of a dominant-negative TGF-β receptor (TGFβRDN) renders the cells resistant to a key immunosuppressive cytokine in the prostate TME, aiming to improve persistence and efficacy. |

| 4 | NCT03873805 | I | City of Hope Medical Center | Active, not recruiting | PSCA-CAR T-cells in treating patients with PSCA + mCRPC | Targets PSCA to address tumor heterogeneity and provides an alternative for PSMA-low or -negative tumors. Utilizes a 4-1BB co-stimulatory domain for potentially improved persistence. |

| 5 | NCT03089203 | I | University of Pennsylvania | Active, not recruiting | CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells in mCRPC | Pioneering study of the TGF-β “armored” CAR strategy in prostate cancer, providing critical early-phase safety and efficacy data for this resistance mechanism. |

| 6 | NCT05022849 | I | Janssen Research & Development, LLC | Active, not recruiting | KLK2 CAR-T/JNJ-75229414 in mCRPC | Explores KLK2 as a novel target antigen, diversifying the therapeutic arsenal beyond the more common PSMA and PSCA. |

| 7 | NCT04249947 | I | Poseida Therapeutics, Inc. | Terminated | P-PSMA-101 CAR-T in mCRPC and advanced salivary gland cancers | Utilizes a non-viral piggyBac® transposon system for manufacturing, aiming to produce a high proportion of Tscm, which are associated with superior persistence and durability in vivo. |

| 8 | NCT05805371 | I | City of Hope Medical Center | Recruiting | PSCA-targeting CAR-T plus or minus radiation in PSCA + mCRPC | Tests a rational combination with radiotherapy, hypothesizing that radiation will induce immunogenic cell death and remodel the TME to enhance CAR-T cell infiltration and function. |

| 9 | NCT05732948 | I | Shanghai Unicar-Therapy Bio-medicine Technology Co., Ltd. | Unknown status | PD-1 silent PSMA/PSCA targeted CAR-T for prostate cancer | Dual-targeting (PSMA/PSCA) CAR-T with a “PD-1 silent” domain. This aims to prevent T-cell exhaustion within the TME by blocking endogenous PD-1 signaling, effectively combining CAR-T with intrinsic checkpoint inhibition. |

| 10 | NCT00664196 | I | Roger Williams Medical Center | Suspended | PSMA CAR-T + IL-2 in advanced prostate cancer after non-myeloablative conditioning | An early landmark trial exploring the role of lymphodepletion and exogenous IL-2 support to enhance the expansion and persistence of first-generation CAR-T cells. |

| 11 | NCT06236139 | I/II | Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center | Recruiting | STEAP2-targeted CAR T-cell with TGF-β resistance in mCRPC | Introduces STEAP2 as a new target and combines it with the validated TGFβRDN armoring strategy, representing a next-generation approach targeting a novel antigen while countering a key resistance pathway. |

| 12 | NCT06267729 | I/II | AstraZeneca | Recruiting | PSMA-targeted CAR T-cell therapy in advanced prostate cancer | A contemporary PSMA-targeted CAR-T candidate, likely incorporating lessons learned from prior generations regarding co-stimulation and manufacturing. |

| 13 | NCT04637503 | I/II | Shenzhen Geno-Immune Medical Institute | Unknown status | PSMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy (P-PSMA-101) in mCRPC | (See NCT04249947) Highlights the ongoing development of this non-viral, Tscm-enriched product candidate. |

CAR: chimeric antigen receptor; CRS: cytokine release syndrome; ICANS: immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome; IL-2: interleukin-2; KLK2: Kallikrein 2; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; NCT: National Clinical Trial; PSCA: prostate stem cell antigen; PSMA: prostate-specific membrane antigen; STEAP2: six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 2; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta; TGFβRDN: transforming growth factor-beta receptor dominant negative; TME: tumor microenvironment; Tscm: T stem cell memory. Adapted from Meng et al. [6] with added analysis of engineering features.

Among the major safety challenges in CAR-T cell treatment are CRS and ICANS [90, 91]. CRS is graded by widely used clinical ASTCT (American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy) criteria that range from mild fever up to conditions that are life-threatening, including hypotension and respiratory failure. Research shows that ICANS leads to neurological problems and cognitive difficulties, which currently cause most deaths during the early stages of CAR-T treatments in all trials, including PCa investigations [92]. The severity of CRS varies depending on factors such as fever intensity, hypotension, and hypoxia. Symptoms may include high fever, vomiting, headaches, rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, and breathing difficulties [90].

ICANS represents another significant risk, manifesting as both neurological and psychological complications following immunotherapy infusion. It is closely associated with immune effector cells (IECs) and T cell-engaging treatments, making it a serious concern [93]. ICANS and CRS are the leading causes of mortality in early-phase CAR-T cell therapy trials.

CAR-T cell therapy’s success rate depends largely on identifying specific antigens on cancer cells that can be precisely targeted. While the therapy has shown promising outcomes, its effectiveness is not universal, emphasizing the need for continued research to optimize antigen targeting and improve overall therapeutic success [94].

The therapeutic effect of CAR-T cell therapy can be limited if, for any reason, the modified cells do not express the appropriate antigens or develop mechanisms for immune escape. In preclinical and early clinical trials for PCa treatment, CAR-T cell therapy has shown promising results, with ongoing studies evaluating its feasibility, safety, and potential efficacy in targeting specific PCa antigens. To improve clinical outcomes, it will be crucial to optimize the development and production of CAR-T cells, as well as to incorporate diverse strategies and prognostic biomarkers.

Ultimately, despite the initial success in CAR T-cell therapy, its partial efficacy in PCa means that treatment needs to include other methods to outwit immune avoidance and the hindering microenvironment present in PCa. Looking forward, combining CAR T-cell therapy with ICIs, androgen receptor inhibitors, and other specific/targeted drugs has the potential to optimize therapeutic impact or hormonal agents. This section summarizes the current clinical trials and new evidence in using combination therapy for PCa, which may improve the outcomes due to exposure to multiple mechanisms of action.

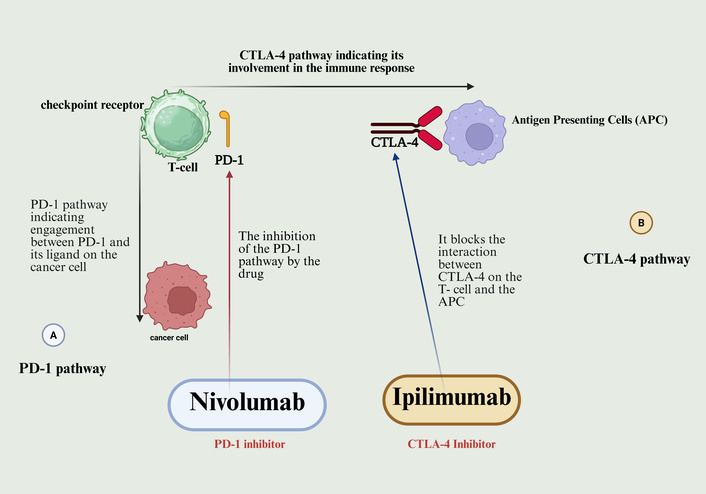

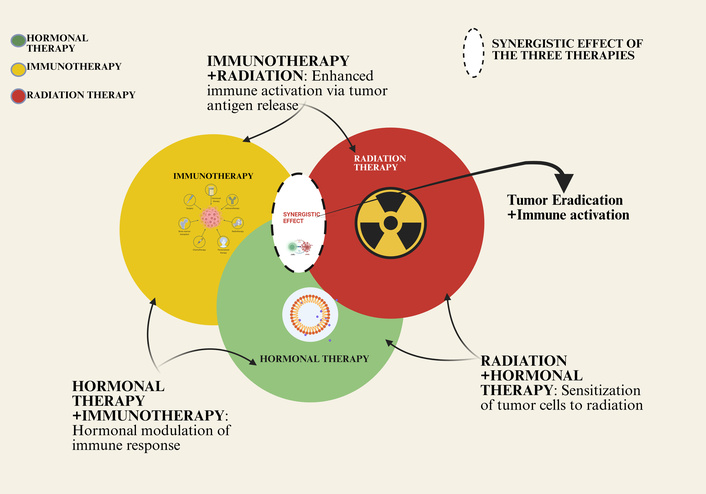

The limited efficacy of single-agent immunotherapies highlights the importance of concerted action on several fronts to achieve a powerful defeat against the profound immunosuppression of PCa. Figure 5 shows the conceptual framework of this strategy, which demonstrates a proposed multimodal therapy that is intended to be used to achieve synergistic tumor eradication and immune activation.

Synergistic interactions between hormonal therapy, immunotherapy, and radiation therapy in prostate cancer. This Venn diagram illustrates the conceptual framework for combining major treatment modalities. Immunotherapy (yellow) directly activates the immune system against tumor cells. Radiation therapy (red) induces direct tumor cell killing and can enhance immune activation through mechanisms like antigen release. Hormonal therapy (green) modulates the tumor microenvironment, sensitizing cells to radiation and immunotherapy. The overlapping areas highlight the synergistic benefits of dual and triple combinations, where the interplay of these mechanisms—such as enhanced immune activation and tumor cell sensitization—leads to more effective tumor eradication and represents a comprehensive strategy for advanced disease. Created in BioRender. Nyame, D. (2026) https://BioRender.com/bdfi3ur.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib acts as a small molecule against MET and VEGFR2 receptors, showing clinical effectiveness in mCRPC. The COMET-1 trial did not demonstrate an improvement in overall survival in CRPC patients previously treated with cabozantinib monotherapy, although it demonstrated an increased progression-free survival in Phase II trials [95, 96].

Research into atezolizumab (an anti-PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor) in combination with cabozantinib for advanced PCa treatment became the focus of COSMIC-021 trials. The clinical trial data showed effective PSA outcomes of disease suppression when combining therapies of target kinase therapy and checkpoint inhibitor therapy [97, 98]. However, the high occurrence of severe adverse events of grade 3–4, specifically with pulmonary thrombosis, requires better treatment strategies and methods for patient selection. The combination shows promise for the improvement of immune responses against PCa tumors since they typically show poor immunogenicity. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors work to improve tumor environment conditions by disrupting disease-related vascular barriers that impede immune cell infiltration, which results in stronger checkpoint inhibitor effects. Future trials focusing on biomarkers will develop the ability to predict immune responsiveness as well as minimize adverse effects for this combined therapy.

The collective clinical experience of PCa immunotherapy shows that there is a common pattern to monotherapies, be it in the form of checkpoint, CAR T-cells, or BiTEs, that lack the ability to overcome the multifaceted resistance of the TME. This has been a wake-up call that has led to a resolute move towards rationally conceived multimodal regimens. The next-generation paradigm is not linear but rather combined to the extent that it layers the therapies primarily performing different and complementary activities: priming the immune reactions (vaccines, immunogenic cell death inducers such as PARPi/radiotherapy), engaging the effector cells directly (BiTEs, CAR-T), and eliminating the immunosuppressive barriers (ICIs, ARSIs, TGF-β blockade).

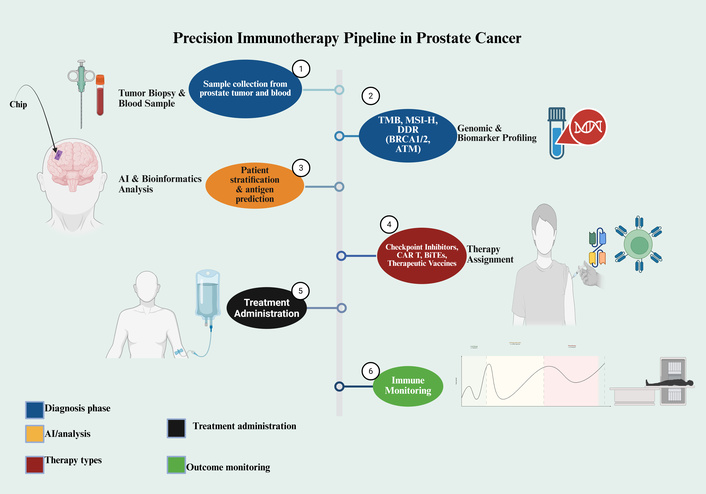

Nevertheless, mere combinations of agents have been found insufficient as the failure of ICI combinations in unselected populations with standard-of-care therapies has been repeated. These failures point to the conclusion that the future generation of combinations ought to be biologically informed, to focus on the non-redundant resistance pathways, like the newly understood TSP-1-CD47 axis, and it should be directed by profound biomarker profiling. This will require the end of a one-size-fits-all approach to a precision immuno-oncology strategy, which is dynamically directed to the specific immunological state of the tumor of a particular individual. This envisioned pipeline that fuses the extensive molecule profiling, AI analytics, and longitudinal immune monitoring to guide and inform therapeutic selection, as depicted in Figure 6.

A precision medicine pipeline for personalized immunotherapy in prostate cancer. The framework outlines a multi-step process for tailoring immunotherapeutic strategies. It begins with (1) the collection of tumor tissue and blood samples, followed by (2) comprehensive genomic and biomarker profiling (e.g., TMB, MSI-H, DDR genes). (3) AI-driven bioinformatic analysis then facilitates patient stratification and neoantigen prediction. (4) Based on this integrated profile, a specific immunotherapy is assigned, such as checkpoint inhibitors, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells, bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), or vaccines. (5) The selected treatment is administered to the patient, and (6) immune responses are systematically monitored to assess clinical outcomes. This approach aims to enhance treatment efficacy through personalized, data-driven decision-making. Created in BioRender. Nyame, D. (2026) https://BioRender.com/7d4fka3.

The process of effectively exploiting the immune system in curing PCa has gone through a transition from the early stages of failure in using single-agent treatments to a more complicated realization of how immunosuppressive nature of the prostate disease. This review has critically analyzed the landscape and has shown that although there are isolated results in the biomarker-selected patients that validate immunology as a therapeutic pillar, broad efficacy has not been achieved. The fundamental obstacles, namely, a low-mutational-burden landscape, an androgen receptor-mediated immunosuppressive axis, and a redundant, inhibitory TME require an integrated fight, but not a directed attack.

Consequently, it is indisputable that the future of immunotherapy of PCa lies irreparably in multimodal regimens that are designed rationally. Within the paradigm, it is necessary to go beyond the simple combination of drugs to rationalize the intelligent combination of mechanisms: one modality to prime the immune system (e.g., vaccines, radioligand therapy), another to directly arm the effector cells (e.g., BiTEs, CAR-T), and another to support the effector cell activity by disrupting immunosuppressive networks (e.g., ICIs, TGF-β blockade). Recent discoveries of new pathways, such as the TSP-1-CD47 axis, are an example of how therapeutic vulnerabilities have yet to be discovered in the TME.

Ultimately, such a combinatorial promise is reproducible as a benefit to survival, but will have to be introduced with a precise immuno-oncology framework. This requires the transition to dynamic integrative profiling that captures the individual, genomic, and immunologic setting of the tumor of individual patients. Proving that immunotherapy is going to be effective in PCa is no longer the paramount challenge, but rather a systematic identification of who, in what order, and combination, immunotherapy will be the most effective. The effectiveness of this project will create a new level of care and revolutionize the treatment of progressive PCa with truly personalized therapeutic plans.

BiTEs: bispecific T-cell engagers

CAR: chimeric antigen receptor

CRS: cytokine release syndrome

ICANS: immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome

ICIs: immune checkpoint inhibitors

irAEs: immune-related adverse events

mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

MSI-H: microsatellite instability-high

PAP: prostatic acid phosphatase

PCa: prostate cancer

PSA: prostate-specific antigen

PSMA: prostate-specific membrane antigen

TMB: tumor mutational burden

TME: tumor microenvironment

TSP-1: thrombospondin-1

DKN: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Software, Methodology. VB: Investigation, Software. IJK: Visualization, Investigation. XZ: Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1374

Download: 31

Times Cited: 0