Affiliation:

1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata 1900, Argentina

2Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), La Plata 1900, Argentina

Email: dbuldain@fcv.unlp.edu.ar

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7772-2453

Affiliation:

1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata 1900, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6761-8372

Affiliation:

1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata 1900, Argentina

2Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), La Plata 1900, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8958-0459

Affiliation:

1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata 1900, Argentina

2Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), La Plata 1900, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3690-4180

Affiliation:

1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata 1900, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9500-8771

Affiliation:

1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata 1900, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6139-5884

Affiliation:

3Instituto de Dermatología Veterinaria (IDV), Malvinas Argentinas 1615, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7359-0875

Affiliation:

1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata 1900, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-0678-5757

Affiliation:

1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata 1900, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-5186-8937

Affiliation:

1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata 1900, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9162-8834

Explor Drug Sci. 2026;4:1008138 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2026.1008138

Received: October 07, 2025 Accepted: December 02, 2025 Published: January 05, 2026

Academic Editor: Fernando Albericio, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, Universidad de Barcelona, Spain

The article belongs to the special issue Discovery and development of new antibacterial compounds

Aim: This study aimed to establish the in vitro efficacy of chlorhexidine (CHX)-silver nanoparticles (AgNP) based preparation, against Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) in planktonic cultures, biofilms, and on inert stainless-steel surfaces.

Methods: The in vitro antimicrobial activity of the CHX-AgNP formulation (Dermosedan MRSA Nano AG®) was evaluated against reference and multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa by determining the minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentrations (MIC and MBC), as well as the minimum biofilm inhibitory and eradication concentrations (MBIC and MBEC). Also, the residual bactericidal activity on inert stainless-steel surfaces was evaluated.

Results: MIC against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and MDR P. aeruginosa (MDR-PA) isolates ranged between 5/2.5–20/10 µg/mL, up to 8,000 times lower than the manufacturer’s recommended concentration, while MBC ranged from 500 to 2,000 times lower. MBIC matched the MBC, while higher concentrations were needed to eradicate preformed biofilms. On stainless-steel surfaces, high antimicrobial activity was observed for both pathogens. No bacterial survival was detected even after 6 hours at 4% CHX + 2% AgNP concentration. The CHX-AgNP combination demonstrated strong antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa.

Conclusions: These results support the potential application of Dermosedan MRSA Nano AG® as a strategy for managing topical resistant infections and for environmental disinfection in both veterinary and clinical settings.

The increase in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become a great concern all over the world. Since 2015, a global plan for the control of bacterial resistance was agreed by the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH), and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) [1, 2]. In 2022, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) became part of this quadripartite alliance [2, 3]. Bacterial resistance is a problem that affects worldwide health, causing failure in human and animal therapy.

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) are two microorganisms classified as high-priority pathogens in 2024 by the WHO due to their global threat to public health [4]. They belong to the ESKAPE group (acronym that includes Enterococcus faecium, S. aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.), six genera of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria that are of global concern due to their resistance to multiple antibiotics and their ability to cause serious infections, especially in hospital settings [5]. P. aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen found both in the environment and in patients (humans and animals), which constitutes a significant threat due to its high antibiotic resistance (natural and acquired) and its virulence. In veterinary medicine, P. aeruginosa is frequently found in dogs, and multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotypes are mainly reported in cases of chronic otitis externa [6]. S. aureus is a major opportunistic pathogen in humans and one of the most important in veterinary medicine. It can be transmitted not only from animals to humans but also from humans to animals [7, 8]. This microorganism can select resistance to several antibiotics, and the methicillin-resistance phenotype has been identified and increasingly reported in dogs since 2006 in S. aureus [methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)], and in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) species [9]. This last fact has been associated with colonization and infections due to close interaction between humans and pet dogs, which is a great concern [10]. Both Staphylococcus spp. and P. aeruginosa possess multiple virulence factors, including the ability to produce biofilms. Biofilms are composed of microorganisms embedded in an extracellular matrix of exopolysaccharides, proteins, and nucleic acids. This protective barrier hinders the entry of molecules, such as antimicrobials or disinfectants, into the microorganism, as well as the effect of the immune system itself, and they can be formed on animal and human bodies, and on inert surfaces [11].

Consequently, environmental biosecurity is a key tool to reduce the spread of resistant bacteria. Several studies have shown that hygiene practices in clinical and hospital settings, along with the proper use of disinfectants, are essential in preventing bacterial resistance and its spread [12].

Dermosedan MRSA Nano AG® (Instituto de Dermatología Veterinaria, Argentina) is a topical preparation formulated to prevent and treat skin infections caused by resistant bacteria such as MRSA. Its composition includes silver nanoparticles (AgNP) (monodisperse nanoparticle size between 20–30 nm) combined with chlorhexidine (CHX). CHX is a cationic molecule belonging to the biguanide group, composed of two 4-chlorophenyl rings and two biguanide units linked by a hexamethylene chain [13, 14]. It is widely used as an antiseptic, disinfectant, and preservative in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, as well as for the control of bacterial plaque in dentistry, both in human and veterinary medicine. Due to its positive charge, CHX binds to the negatively charged extracellular components of the bacterial membrane, causing its destabilization and altering osmotic balance. This leads to the loss of essential intracellular substances, such as ions, nucleic acids, and proteins, and, consequently, the emptying of cellular contents. It also inhibits the activity of key enzymes such as the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system and ATPase. At high concentrations, it can precipitate bacterial cytoplasm, causing cell death [15]. This substance has a broad antimicrobial spectrum, being effective against numerous microorganisms, including gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, as well as fungi and yeasts [16].

AgNPs have garnered significant attention for their antimicrobial capabilities, which have been recognized since ancient medicine and are currently utilized in various commercial products containing silver in ionic or nanoparticulate form. AgNP exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, viruses, and mycobacteria. Additionally, they can enhance the effectiveness of certain antibiotics through synergistic interactions. Their antimicrobial mechanisms involve the production of reactive oxygen species, interference with DNA, disruption of microbial cell membranes, and inhibition of protein synthesis [17]. These antimicrobial mechanisms are based on the formation of Ag+ ions in aqueous solution, which are also responsible for the bactericidal activity of other silver-based compounds such as silver oxide [18]. These are highly reactive and capable of interacting with various bacterial structures such as nucleic acids, cell membranes, and proteins. Ag+ ions can bind to thiol groups of proteins and enzymes, altering the structure of the bacterial cell wall [19]. The use of AgNP has advantages over the direct use of Ag+ solutions such as silver nitrate, allowing for a prolonged and controlled release of Ag+ through gradual dissolution, thus maintaining antimicrobial efficacy over time [20]. Recent studies have highlighted the efficacy of AgNP against various clinically relevant bacterial strains, including S. aureus and P. aeruginosa [21].

All these challenges have driven the search for new strategies to combat AMR, developing new antimicrobial alternatives to treat infections and control environmental transference of AMR genetic determinants. Several reports have shown that combining CHX with AgNP results in synergistic antimicrobial effects, enhancing membrane disruption and bactericidal activity compared to each agent alone. Such synergy has been demonstrated against S. aureus, Escherichia coli (E. coli), and Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) biofilms [22–24], supporting the potential of CHX-AgNP formulations, although studies focusing on S. aureus and P. aeruginosa biofilms remain scarce. The aim of this work was to determine the in vitro efficacy on planktonic forms, biofilm, and inert surface of a disinfectant/antiseptic Dermosedan MRSA Nano AG® (Instituto de Dermatología Veterinaria, Argentina), against reference strains of S. aureus ATCC 29213 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and multi-resistant isolates [MRSA, and MDR P. aeruginosa (MDR-PA)].

Antimicrobial susceptibility test for reference strains and MDR isolates was determined by the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) method, quantitative microdilution broth test based on the determination of the growth of the microorganism in the presence of increasing concentrations of the antimicrobial drug in 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (Deltalab SL, Argentina), according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines CLSI VET01S-ED7 [25] using Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) (Britania, Argentina) as culture media. These tests were carried out against the reference strains S. aureus ATCC 29213, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, MRSA isolated from human samples, and MDR-PA strain isolated from the external auditory canal of a dog with otitis externa, both MDR isolates belonging to our laboratory strain collection. The inoculum used contained a final concentration in the microplates of 5 × 105 CFU/mL. The commercial product containing 4% (or 40,000 µg/mL) CHX and 2% (or 20,000 µg/mL) AgNP (Dermosedan MRSA Nano AG® suspension, Instituto de Dermatología Veterinaria) was prepared. The total series of concentrations evaluated contained 5,000–0.07 µg/mL for AgNP in combination with CHX, 10,000–0.15 µg/mL. Positive (MHB and inoculum) and negative controls (MHB) were included in the microplate design. Also, a quality control was added using gentamicin according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines CLSI VET01S-ED7 [25]. Microplates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours in aerobic conditions. The MIC was established as the lowest concentration that inhibits bacterial growth visually and spectrophotometrically at 625 nm (Eon Biotek, United States).

The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was established after MIC determination [26]. Microtiter wells without visible bacterial growth were plated on MH agar (MHA) plates (Britania, Argentina), spreading 100 µL for bacterial count and incubating for 24 hours at 37°C. This was also performed in duplicate. MBC is defined as the lowest concentration of a drug able to kill most viable organisms (> 99.9% of the initial inoculum) after 24 hours of incubation aerobically at 37°C.

Prior to antibiofilm activity tests, the microorganisms’ ability to form biofilms in vitro was evaluated. The isolates were cultured in trypticase soy broth (TSB) (Britania, Argentina) supplemented with 1% (w/v) glucose (Anedra, Argentina) and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Bacterial inoculum was adjusted to a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL using the same enriched medium. A volume of 200 μL of this bacterial suspension was plated onto 96-well flat-bottom plates (Deltalab SL, Argentina) and incubated under static conditions at 37°C for 24 hours, allowing biofilm formation. Then, the contents of the wells were removed, rinsed with distilled water, and dried in an oven at 60°C for 30 minutes. A volume of 200 μL of 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet (Anedra, Argentina) was added to each well and left to stand for 10 minutes at room temperature. Excess dye-stuff was removed by two washes with water. To release the crystal violet retained by the biofilm, 200 μL of 96% ethanol (Anedra, Argentina) was added to each well and left to stand for 15 minutes. The contents were then transferred to a new plate to measure absorbance at 595 nm by spectrophotometry (Eon BioTek, United States). Biofilm formation was assessed by comparing the results with the negative control. The critical optical density cutoff (ODc) was established as the average of the negative controls plus three times the standard deviation (SD).

According to this value, the strains were classified as follows: non-biofilm forming [optical density (OD) ≤ ODc], weak forming (ODc < OD ≤ 2 × ODc), moderate forming (2 × ODc < OD ≤ 4 × ODc), and strong forming (OD > 4 × ODc) [27].

The ability of CHX-AgNP formulations to inhibit biofilm formation was evaluated in vitro. The 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates (Deltalab SL, Argentina) were loaded with TSB (Britania, Argentina) containing 1% (w/v) glucose (Anedra, Argentina), with bacterial inoculum (5 × 105 CFU/mL) and the corresponding dilution of each formulation, repeating the range of concentrations evaluated in quadruplicate. The concentrations evaluated of the formulation CHX-AgNP were similar to those mentioned for MIC and MBC. They were incubated statically at 37°C for 24 hours. Subsequently, the culture medium was removed, and each well was washed with physiological solution to eliminate planktonic cells. The formed biofilm was stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet (Anedra, Argentina) and solubilized with 96% ethanol (Anedra, Argentina) to measure its absorbance at 595 nm spectrophotometrically (Eon BioTek, United States). Negative controls and untreated positive controls (bacterial inoculum and TSB culture medium with 1% w/v glucose) were used. The percentage of inhibition for each treatment was calculated using the formula:

Where IBF% is the inhibition of biofilm formation percentage, and A595 is the absorbance determined at a wavelength of 595 nm.

The minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) was defined as the minimum concentration that inhibited biofilm formation by IBF% ≥ 90% compared to the untreated controls in 90% of the isolates [28].

The formulation’s antibiofilm effect was also determined by preformed biofilm eradication analysis, assessing the minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC), defined as the minimum concentration that prevents visible growth of the microorganism after exposing an already formed biofilm to an antimicrobial agent [29]. The 96-well flat-bottom microplates (Deltalab SL, Argentina) were loaded with bacterial inoculum at a concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL in TSB (Britania, Argentina) containing 1% w/v glucose (Anedra, Argentina) and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours to allow biofilm formation. Each well was then washed with sterile saline solution, and decreasing dilutions of the formulation were loaded onto the formed biofilms in quadruplicate, completing a range of 10,000/5,000–0.15/0.07 µg/mL of CHX-AgNP. They were incubated statically at 37°C for 24 hours, and then the culture medium was removed from each well and washed with sterile saline solution to eliminate planktonic cells. Finally, TSB (Britania, Argentina) containing 1% glucose (Anedra, Argentina) was added to each well to resuspend the treated bacterial biofilm. Each well was seeded by taking 20 µL in drops onto CHROMagar™ Orientation plates. The MBEC was determined as the level that produced total eradication of the previously formed bacterial biofilm, i.e., no growth after seeding each well.

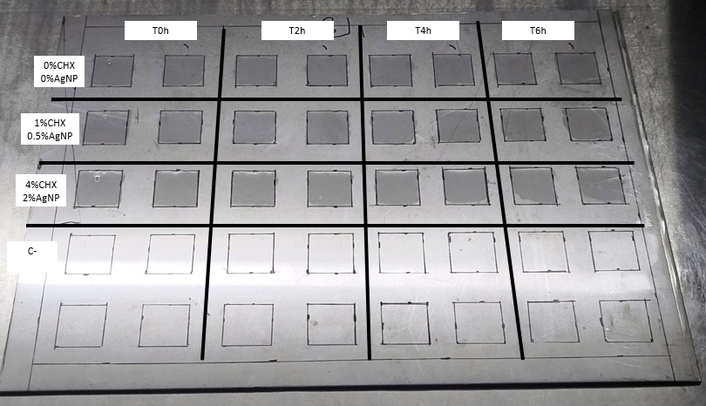

To evaluate the residual bactericidal effect of disinfectant products on non-porous surfaces, the UNE-EN 13697 standard was adapted [30]. The strains used were MRSA and MDR-PA. Two concentrations of the formulation were used: the manufacturer-recommended concentration of use (40,000 µg/mL of CHX with 20,000 µg/mL of AgNP) and a 25% dilution of the pure formulation, obtaining a final concentration of 10,000 µg/mL of CHX with 5,000 µg/mL of AgNP. Briefly, the test procedure consisted of streaking the inoculum onto a sterile stainless-steel plate previously marked in 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm squares (Figure 1), and exposing the microorganisms to known concentrations of the formulation in order to evaluate the persistence effect and the bactericidal activity. A volume of 100 μL of two formulation concentrations (40,000/20,000 μg/mL; 10,000/5,000 μg/mL) and an untreated control were placed in these quadrants and exposed to the bacterial inoculum at different times (0, 2, 4, and 6 hours after application of the formulation on the plate).

Biosafety cabinet with stainless-steel plates. Each plate had 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm square markings to evaluate the formulation against MRSA and MDR-PA strains at 0, 2, 4, and 6 hours after product application. CHX: chlorhexidine; AgNP: silver nanoparticles; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MDR-PA: multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

The plates were kept throughout the test in a sterile environment (Biosafety Cabinet Class II, Biobase, China) at a temperature between 18°C and 25°C. The selection of the concentrations evaluated arose from the results obtained in the previous MIC, MBC, MBIC, and MBEC evaluation, and considering the concentrations recommended by the manufacturer. After 30 minutes of placing the formulation (time zero) on the surface to be evaluated, 50 μL of a bacterial suspension of the MDR isolates (MRSA and MDR-PA) was inoculated at 0, 2, 4, and 6 hours after the initial application of the formulations on the surface at a concentration of 1 × 108 CFU/mL. After applying the bacterial inoculum, it was left in contact for 30 minutes. Subsequently, 100 μL of neutralizing solution [0.3% lecithin + 3% tween 80 (Biopack, Argentina)] was added to each quadrant to inactivate the effect of the formulation, leaving it in contact for 10 minutes. Each quadrant of the surface was swabbed with a sterile swab, scraping it completely in three directions. The swab contents were suspended by twirling the swab in physiological solution, and 6 serial 10-fold dilutions were made to count colonies after plating 100 μL of each one onto nutrient agar plates. To obtain a homogeneous colony count after plating, sterile 2-mm diameter glass beads were used per plate, and the plates were moved in three directions for 1 minute to allow inoculum dispersion across the entire agar surface. They were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Finally, bacterial counts were performed under each condition in duplicate.

Based on the information presented in the literature and considering the possible residual bactericidal activity of dry disinfectant solutions, the residual bactericidal effect was established when the disinfectant showed a bactericidal activity greater than or equal to 3 Log10 at each time tested [31].

Values obtained for the determination of persistence time on an inert surface were graphed, including ± SD, using the program GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.1; GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). A two-way ANOVA with interaction was performed using the program STATGRAPHICS® Centurion XVII (Statpoint Technologies, Inc.) to assess the effects of different concentrations of CHX-AgNP and application time of the formulation on Log10-transformed bacterial counts (CFU/mL). Type III sums of squares were used. When significant effects were detected, Fisher’s Least Significant Difference test was applied for multiple comparisons (α = 0.05).

The MIC for S. aureus was 5/2.5 µg/mL (CHX/AgNP) for both the reference strain and MRSA, meaning that in vitro efficacy is observed at concentrations 8,000 times lower than the recommended concentration. For reference, P. aeruginosa and MDR-PA, the MIC was slightly higher, 20/10 µg/mL (CHX/AgNP) for both. After seeding each well to determine the MBC, bacterial death was observed at concentrations close to the MIC: 40/20 µg/mL for the ATCC reference strain of P. aeruginosa, 80/40 µg/mL for MDR-PA, and 20/10 µg/mL for the reference S. aureus and MRSA (Table 1). These results demonstrate a bactericidal behavior of CHX-AgNP against those microorganisms.

MIC and MBC values of CHX-AgNP against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa reference strains and MDR isolates.

| Microorganism | MIC CHX/AgNP (µg/mL) | MBC CHX/AgNP (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| SA ATCC | 5/2.5 | 20/10 |

| MRSA | 5/2.5 | 20/10 |

| PA ATCC | 20/10 | 40/20 |

| MDR-PA | 20/10 | 80/40 |

MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; MBC: minimum bactericidal concentration; CHX: chlorhexidine; AgNP: silver nanoparticles; S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus; P. aeruginosa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; MDR: multidrug-resistant; SA ATCC: S. aureus ATCC 29213; MRSA: methicillin-resistant S. aureus; PA ATCC: P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853; MDR-PA: MDR P. aeruginosa.

Regarding antibiofilm activity, it was observed that against S. aureus bacteria, the concentration that inhibited biofilm formation was 10/5 µg/mL (CHX/AgNP).

Regarding the P. aeruginosa, the concentrations that inhibited biofilm formation for the ATCC reference strain were 40/20 µg/mL (CHX/AgNP). However, in the MDR strain, a concentration of 80/40 µg/mL (CHX/AgNP) is required (Table 2).

MBIC and MBEC values of CHX-AgNP against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa reference strains and MDR isolates.

| Microorganism | MBIC CHX/AgNP (μg/mL) | MBEC CHX/AgNP (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| SA ATCC | 10/5 | 2,500/1,125 |

| MRSA | 10/5 | 2,500/1,125 |

| PA ATCC | 40/20 | 10,000/5,000 |

| MDR-PA | 80/40 | 10,000/5,000 |

MBIC: minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration; MBEC: minimum biofilm eradication concentration; CHX: chlorhexidine; AgNP: silver nanoparticles; S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus; P. aeruginosa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; MDR: multidrug-resistant; SA ATCC: S. aureus ATCC 29213; MRSA: methicillin-resistant S. aureus; PA ATCC: P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853; MDR-PA: MDR P. aeruginosa.

The ability of the formulations to eradicate preformed biofilms was studied for the reference strains S. aureus ATCC 29213, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, MRSA, and MDR-PA. The MBEC values (Table 2) were considerably higher than the MIC, MBC, and MBIC values. P. aeruginosa presented higher MBEC values than S. aureus.

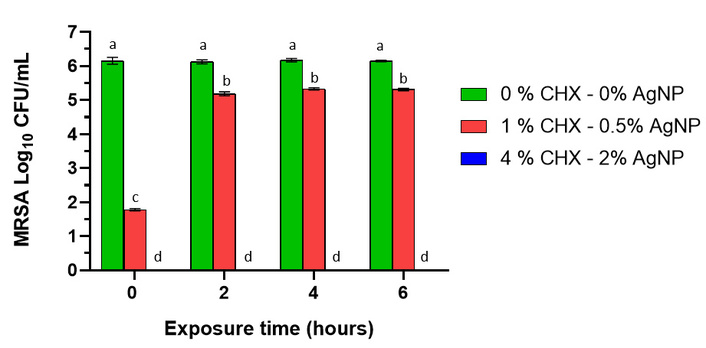

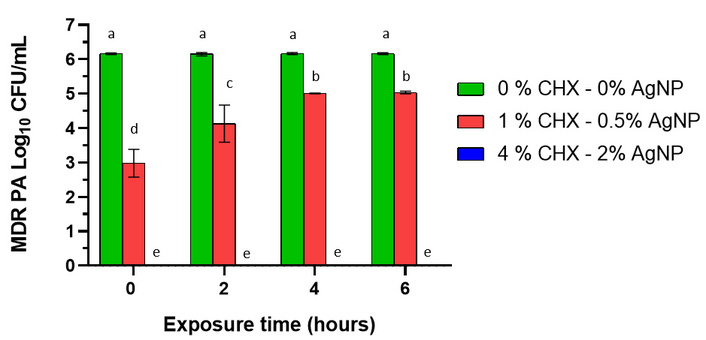

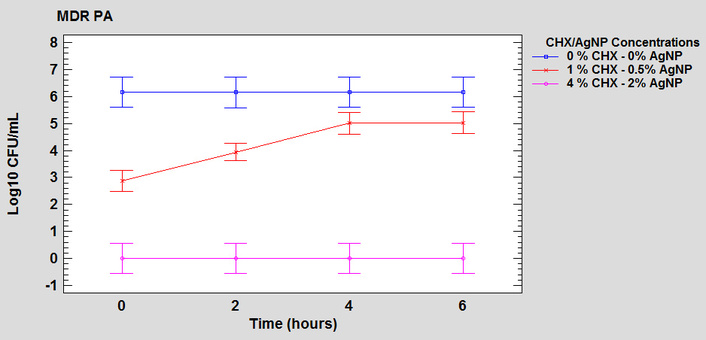

The evaluation of antimicrobial activity on an inert stainless-steel surface showed a significant decrease in bacterial load compared to the positive control due to the application of the formulation for both MRSA and MDR-PA (Figures 2 and 3, respectively). In the case of the pure formulation (4% CHX-2% AgNP or 40,000 µg/mL CHX-20,000 µg/mL AgNP), bacterial survival was zero for both microorganisms, even after 6 hours post-application of the product on the metal surface. However, efficacy for a 1/4 dilution of the formulation (1% CHX-0.5% AgNP or 10,000 µg/mL CHX-5,000 µg/mL AgNP) was lower and decreased with increasing residence time, but even so, the bacterial count was significantly lower than for the untreated control (p < 0.05) for 6 hours. At 0 hours, for this concentration, the microorganism count was significantly lower than the control, and remained so for both bacterial species at higher times (p < 0.05). At 4 and 6 hours, the 1/4 dilution had similar efficacy against MRSA and MDR-PA.

Effect of chlorhexidine (CHX) with silver nanoparticles (AgNP) against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), expressed as percentage of bacterial survival (%) at 0, 2, 4, and 6 hours post-treatment on an inert metal surface. No viable bacteria were obtained with the 4% CHX-2% AgNP treatment (blue bar). Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean, and there are no statistically significant differences between bars that share the same letter after a significant (p < 0.05) two-way ANOVA (p < 0.05, Fisher’s Least Significant Difference).

Effect of chlorhexidine (CHX) with silver nanoparticles (AgNP) against multi-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MDR-PA), expressed as percentage of bacterial survival (%) at 0, 2, 4, and 6 hours post-treatment on an inert metal surface. No viable bacteria were obtained with the 4% CHX-2% AgNP treatment (blue bar). Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean, and there are no statistically significant differences between bars that share the same letter after a significant (p < 0.05) two-way ANOVA (p < 0.05, Fisher’s Least Significant Difference).

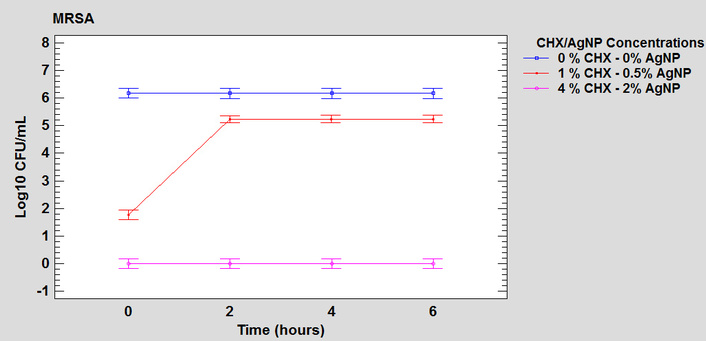

For both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, a significant interaction was demonstrated between the two factors, time and concentration of the formulation (F = 265.78 and F = 12.02, respectively; both corresponding to a p-value < 0.0001), indicating in the overall analysis that bactericidal activity varies according to exposure time. However, examination of individual single effects showed that the time factor is a determinant of the bacterial count only at the 1% CHX-0.5% AgNP concentration (Figures 4 and 5), demonstrating an initial impact with a significant reduction in bacterial load and lower efficacy over the 6-hour evaluated interval. In contrast, the other concentrations, 0% CHX-0% AgNP and 4% CHX-2% AgNP, did not show statistically significant variations between the evaluated times (Figures 4 and 5). This discrepancy confirms that the effect of time is actually conditioned by the concentration of the formulation evaluated, which is consistent with the statistically significant interaction detected in the overall analysis between both factors.

Graph of interaction between the factors of time and concentration of the formulation in the antimicrobial activity on the steel surface against MRSA. MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; CHX: chlorhexidine; AgNP: silver nanoparticles.

Graph of interaction between the factors of time and concentration of the formulation in the antimicrobial activity on the steel surface against MDR-PA. MDR-PA: multi-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa; CHX: chlorhexidine; AgNP: silver nanoparticles.

This study evaluated the antimicrobial activity of a combined formulation, Dermosedan MRSA Nano AG®, which contains 4% CHX and 2% AgNP, considering its efficacy against several microorganisms in different conditions: planktonic cultures, biofilms, and inert metal surfaces. CHX is commonly used in concentrations ranging from 0.5% to 4%, depending on the specific clinical use. For example, hand sanitizers typically contain concentrations within this range, adjusting for antimicrobial efficacy needs [15].

The formulation showed similar MIC and MBC values against most of the microorganisms tested, which means similar efficacy. In the case of S. aureus, both for the reference strain and for the MRSA, the formulation showed a slightly lower MIC (5/2.5 µg/mL CHX/AgNP) compared to that obtained for P. aeruginosa (20/10 µg/mL CHX/AgNP), demonstrating greater intrinsic resistance and tolerance to the formulation, which could be due to its great adaptive capacity. P. aeruginosa shows strong intrinsic resistance to biocides due to the lack of membrane permeability, presence of efflux pumps, and other intrinsic mechanisms of natural and acquired resistance [32].

For both microorganisms, the MBC/MIC ratio was equal to 4, with the formulation behaving as a bactericidal agent [33]. Ivanova et al. [23] showed that the combination of AgNP with CHX has a MIC of 8.8 µg/mL CHX and 5.5 µg/mL AgNP against S. aureus and E. coli, showing a synergistic activity. Other authors have also demonstrated synergism between CHX and AgNP against microorganisms like E. coli and S. aureus [22].

Regarding the ability to MBIC, for the reference S. aureus strain and the MRSA strain, the MBIC values were similar, being 10/5 µg/mL of CHX/AgNP for both. For P. aeruginosa, there was a slight difference between the ATCC reference strain (40/20 µg/mL of CHX/AgNP) and MDR-PA isolate (80/40 µg/mL of CHX/AgNP). Although the antibacterial effect of AgNP on planktonic bacteria is largely attributed to the release of Ag+ ions through dissolution, their role in biofilm disinfection appears particularly advantageous [34]. As individual nanoparticles penetrate deeper into the biofilm, they can gradually dissolve and emit thousands of silver ions, resulting in potent antibacterial activity even in the innermost biofilm layers [35].

Regarding the eradication of already formed biofilms (MBEC), the values were considerably higher than the MBIC, reflecting the greater structural resistance of biofilms once built on the polycylinder surface against both microorganisms. P. aeruginosa again required higher concentrations compared to S. aureus. This is expected due to the complexity of the biofilm already formed. In line with our results, a report informs that CHX was also significantly less effective against P. aeruginosa biofilm bacteria compared to S. aureus, likely due to differences in their cell wall structures [36]. However, it is important to note that the concentrations mentioned for each of the susceptibility tests on planktonic forms or biofilms are clearly lower than those recommended for commercial use (40,000/20,000 µg/mL or 4%/2% of CHX/AgNP), demonstrating that the desired chemotherapeutic effect will be achieved at the manufacturer’s recommended doses. Abbaszadegan et al. [24] found loading AgNP with CHX significantly enhanced its antibacterial activity against E. faecalis biofilms.

CHX had presented in other studies a lower activity in biofilms with respect to planktonic cultures, probably being unable to penetrate biofilm [37]. On the other hand, there are studies in which the activity of AgNP against bacterial biofilms was high and established as concentration-dependent. Biofilms are structures that provide a protective environment to bacteria that improves survival, facilitates nutrient acquisition, and increases resistance to antimicrobial agents and the host immune response [38]. It has been reported that this type of nanoparticle interferes with bacterial quorum sensing by altering the signaling mechanisms that control bacterial communication [39]. This alteration of the quorum-sensing system can weaken bacterial pathogenicity, making AgNP an important tool to control bacterial infections and reduce the effectiveness of bacterial communication mechanisms, particularly in the treatment of topical infections or the coating of medical implants to prevent bacterial adhesion and biofilm development [40].

On stainless-steel surfaces, antimicrobial activity against MRSA and MDR-PA was high. Comparing the 4%/2% (CHX-AgNP) and 1%/0.5% (CHX-AgNP) formulations, the latter was less effective. However, the diluted formulation showed a significant decrease in bacterial count compared to the untreated control. Regarding the formulation’s efficacy after being placed on the metal surface and exposed to microorganisms, we observed that the formulation maintained its efficacy against MRSA and MDR-PA even after 6 hours. In the case of the diluted formulation, efficacy decreased over time, being highest at shorter times; however, even after 6 hours, the recovered bacterial colonies were lower than in the untreated control. The literature on the use of AgNP combined with CHX on inert surfaces is scarce; no works have been found on the subject. CHX is commonly used in the form of a solution for disinfecting skin and mucous membranes, although it is also applied to inert, non-porous surfaces, such as metals, making it a valuable tool for environmental biosecurity. It can adsorb to these surfaces and maintain its antibacterial action for an important period of time, helping to prevent the presence of microorganisms. AgNP can act in different ways. One of the mechanisms of antimicrobial action reported in the literature is based on the formation of Ag+ ions in aqueous solution. These are highly reactive and are capable of interacting with various bacterial structures such as nucleic acids, cell membranes, and proteins. Ag+ ions can bind to thiol groups of proteins and enzymes, altering the structure of the bacterial wall [19], a mechanism that also underlies the potent bactericidal activity described for other silver-based compounds such as silver oxide [18].

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. All experiments were performed under controlled in vitro conditions, which may not fully represent the complexity of clinical or environmental settings. The antimicrobial activity observed on inert stainless-steel surfaces could vary in the presence of organic matter such as blood, exudates, or tissue debris, where protein binding and pH fluctuations can interfere with disinfectant efficacy. In addition, although S. aureus is a relevant zoonotic and opportunistic pathogen, its use as a model organism may not completely reflect the behavior of strictly animal-associated species, such as S. pseudintermedius, that are commonly isolated in veterinary infections. Future studies should therefore include in vivo evaluations in animal models and clinical cases, as well as testing under conditions that simulate organic contamination. Further research will also focus on the efficacy of CHX-AgNP formulations on diverse veterinary surfaces and materials, their long-term persistence, and their integration into hygiene protocols for clinical and environmental disinfection in veterinary practice.

AgNP: silver nanoparticles

AMR: antimicrobial resistance

CHX: chlorhexidine

E. coli: Escherichia coli

E. faecalis: Enterococcus faecalis

MBC: minimum bactericidal concentration

MBEC: minimum biofilm eradication concentration

MBIC: minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration

MDR: multidrug-resistant

MDR-PA: multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

MHB: Mueller Hinton Broth

MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration

MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

OD: optical density

ODc: optical density cutoff

P. aeruginosa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa

S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus

SD: standard deviation

TSB: trypticase soy broth

WHO: World Health Organization

WOAH: World Organization for Animal Health

The authors thank to National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) for their collaboration in funding Ph.D Scholarships and researchers. We would like to thank the students of the Laboratory of Pharmacological and Toxicological Studies, Faculty of Veterinary Science, La Plata University of La Plata, for their assistance with the experiments.

DB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AB: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. LGC: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. KJL: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. FA: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. JdF: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. GC: Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources. GB: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. AP: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. LM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration. All authors contributed to the revision and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the findings of this study will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and authorship of this article. This work was partially financed by the Laboratory of Pharmacological and Toxicological Studies (LEFyT) and the National University of La Plata [UNLP, I+D V323]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 882

Download: 31

Times Cited: 0

Irina Tiganova ... Yulia Romanova

Ebenezer Aborah ... Manuel F. Varela

Ayuba Olanrewaju Mustapha ... Yusuf Oloruntoyin Ayipo

Monika I. Konaklieva ... Balbina J. Plotkin