Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, American University, Washington, DC 20016-8014, USA

Email: mkonak@american.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1068-8326

Affiliation:

2Tuberculosis Research Section, Laboratory of Clinical Immunology and Microbiology, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4373-0367

Affiliation:

2Tuberculosis Research Section, Laboratory of Clinical Immunology and Microbiology, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4333-206X

Affiliation:

3Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Midwestern University, Downers Grove, IL 60515, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0564-3975

Explor Drug Sci. 2026;4:1008145 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2026.1008145

Received: October 17, 2025 Accepted: December 23, 2025 Published: February 01, 2026

Academic Editor: Kamal Kumar, Aicuris Anti-infective Cures AG, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Physiology, Germany

The article belongs to the special issue Discovery and development of new antibacterial compounds

Aim: To design, synthesize, and test small molecules and fragment-based compounds with putative selective anti-mycobacterial activity.

Methods: Standard chemosynthetic processes were used to synthesize 42 compounds. A cell-based phenotypic screen for inhibitors of mycobacterial growth was used to identify several fragments and small molecules as representatives of urea-, carbamothioate-, and α,β-unsaturated systems (Michael acceptors) chemotypes.

Results: All 42 compounds exhibited selective toxicity for mycobacteria as demonstrated by their lack of activity against various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and acid-fast Corynebacterium glutamicum. A thiadiazole compound, similar to (3-((5-(methylthio)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile), which activates the human lecitin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT), exhibits growth-inhibitory activity [0.6 μg/mL in bovine serum albumin (BSA)-free media] against drug-susceptible Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). From the urea class, a 1,2,4-triazole-containing urea demonstrated anti-Mtb activity (4.7 μg/mL in BSA-free media). Several carbamothioate-based fragments demonstrated activity against Mycobacterium marinum [with a best minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 6.25 μg/mL in minimal BSA-free media].

Conclusions: This foundational study demonstrates the utility of these newly designed and synthesized low molecular-weight compounds and fragments as potential antimycobacterials.

Fragment-based ligand use in drug discovery has proved to be an efficacious methodology for identifying new leads in the development of biologically active compounds [1–3]. This methodology is based on the possibility of modulating the comparatively specific binding of fragments to their molecular targets by controlling fragments’ lipophilicity and selectivity. Approaches that utilize phenotypic screening, including high-throughput methods, have once again become prominent tools for identifying new antibiotics.

The identification of hit compounds with suitable functionalities can be achieved rapidly, and in addition, can provide information about their early biological activity profiles and the extent to which protein binding to media components such as bovine serum albumin (BSA) affects access to putative cellular targets.

The distinct advantage of phenotypic drug screening is that it provides an approach to the identification of biochemical targets in the pathogen in model systems without requiring prior knowledge of the essential metabolites or pathways. Furthermore, this method can be used to detect inhibitors under in vivo-relevant conditions while being conducted using in vitro cell-based experiments. Although this approach is labor-intensive, it has several advantages over alternative fragment-based drug discovery methods, including the potential for targeting not only protein targets but also potentially detecting those that interfere with the function of multiple classes of molecules, such as nucleic acids, lipids, or carbohydrates. An additional advantage of this drug screening approach is that by modulating their LogP and testing environment, the fragment binding specificity can be controlled [4–6].

Since we are interested in exploring the modulation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) lipid metabolism, we screened fragments and low-molecular-weight compounds that were prepared based on four chemotypes [ureas, amides, carbamothioates, and Michael acceptors (MA)] that have demonstrated ligand efficiency (LE) against Mtb-associated lipid metabolism enzymes. InhA, enoyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) reductase, is an essential enzyme in Mtb cell wall biosynthesis [7–9]. The InhA reductase is inhibited by the drug isoniazid (INH) as well as Mtb enzymes involved in cholesterol catabolism. While InhA, a part of the type II fatty acid synthase (FAS-II) complex involved in NADH-dependent reduction of long-chain fatty acids [10], is an established Mtb drug target, the development of inhibitors of the catabolic pathway of Mtb towards the host’s lipids, specifically cholesterol, has been much less explored [11–18]. The identification of several small molecules as inhibitors of the Mtb enzymes involved in the host’s cholesterol catabolism in the last decade has been accomplished by high-throughput screening of currently available libraries representing different chemotypes, which in some instances have been followed by focused libraries [13, 14, 18]. The focus of our study was on a chemistry-driven exploration of the space around fragments and low-molecular-weight compounds based on the aforementioned chemotypes, with a wide range of fragment lipophilicity, coupled with phenotypic evaluation of their antimycobacterial/antibacterial activity.

Both hydrophilic and hydrophobic small molecules have been identified in phenotypic screens. For example, the rationally designed fragment 3 (Figure 1), as an inhibitor of CYP125 (KD = 0.04 μM) and CYP142 (KD = 0.08 μM), is lipophilic (LogP predicted 3.89) [18]. The small molecule, GSK2556286 (1, Figure 1), an anti-Mtb drug candidate (LogP predicted 0.93), inhibits growth within human macrophages [50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) = 0.07 μM], and has demonstrated activity both in vitro and in vivo [19, 20]. Its mechanism of action is not yet fully established; it has been determined that this compound blocks the growth of Mtb in cholesterol media and increases intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels almost 50-fold [20].

Small polar anti-Mtb compounds are exemplified by the well-established clinically relevant drugs INH and pyrazinamide (PZA) [21–23]. These drugs are characterized as hydrophilic (CLogP < 2.5), with a low molecular weight (MW < 250 g/mol) that places them within the definition of fragments, and they can cross Mtb’s cell wall. Their ability to do so appears to be facilitated by the presence of hydrophilic channels, allowing the entry of polar nutrients in Mtb [24]. Therefore, library fragments and small MW compounds with a very broad range of lipophilicity (from negative LogP –2.27 to positive LogP > 5.00) were included in the current study for testing.

Anhydrous solvents, reagent-grade solvents for chromatography, and starting materials were obtained from various sources (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA; Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI; Matrix Scientific, Columbia, SC; Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium) and used without further purification. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out using Silicycle plates with a fluorescence indicator (SiliaPlate™ TLC glass-backed, 250 μm thickness, F-254); the compounds were detected under UV light (254 nm). Products were purified by flash chromatography, gradient elution from silica gel columns [SiliaSep™ C18 (17%), particle size 40–63 μm, 60 Å], and/or recrystallization. Unless stated otherwise, solutions in organic solvents were dried with anhydrous magnesium sulfate at room temperature (RT) and concentrated under vacuum conditions using rotary evaporation.

All compounds were characterized by 1H and 13C NMR spectra (25°C). Spectra were obtained at 400 and 600 MHz for 1H NMR, 100 MHz and 125 MHz for 13C NMR, respectively, in CDCl3 or DMSO-d6 at 25°C (Bruker 400, Billerica, MA, and 600 MHz Varian spectrometers). All chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million (ppm) and referenced to tetramethyl silane (TMS); coupling constants (J) are reported in hertz (Hz). All compounds tested were 98% pure by elemental analysis and LC-MS (Figures S1–14 and Table S1). Elemental analyses (C, N) were performed by Atlantic Microlab, Inc. (Norcross, GA). LC-MS spectra were obtained from Agilent 6150 and Shimadzu LC-MS 2050 using a solvent gradient from 4% to 100% acetonitrile (0.05% TFA) over 7 minutes, column Luna C18 (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA), 3 µm, 3 mm × 75 mm. IR spectra were obtained from thin films (NaCl plates) and solid samples (KBr standard) using a Bruker ALPHA II FT-IR spectrometer and reported as C=O values in cm–1 (Figures S1–14 and Table S1). Other instruments used include Teledyne Isco, HPLC, and a Kimble-Chase Melting Point Apparatus. Compounds were stored at RT and checked periodically (1–2 months) for stability by MS.

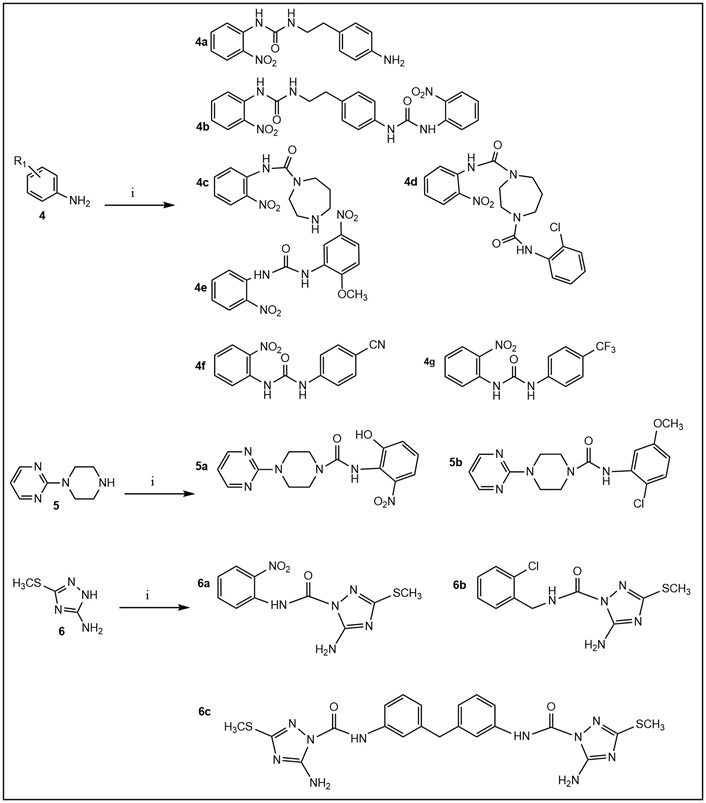

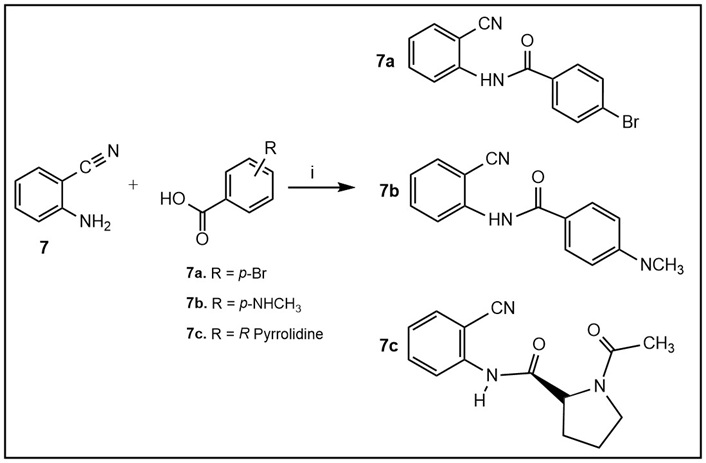

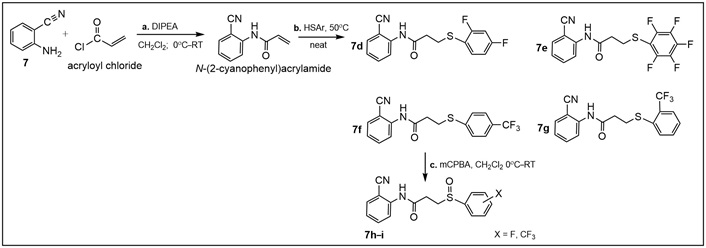

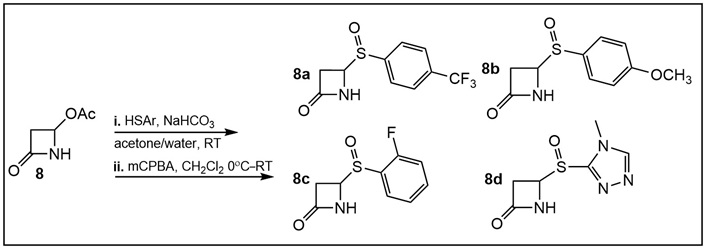

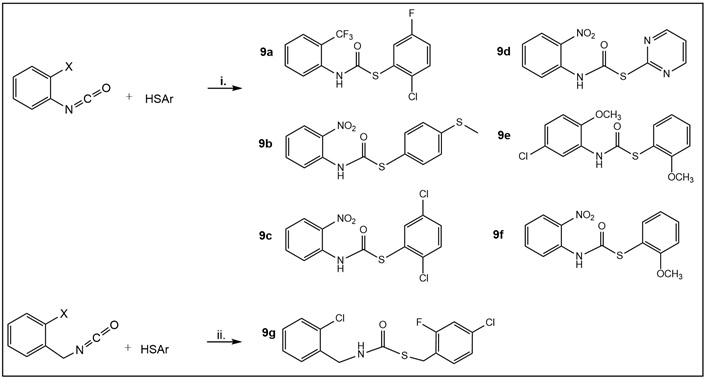

All compound representatives of different chemotypes were synthesized via previously described methods, which are briefly described below (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) [25, 26]. Representative examples of the syntheses of the compounds in Tables 1 and S2 are given below.

Synthesis of ureas. Ureido derivatives (Tables 1 and S2) were prepared from the commercially available amines 4–6 (step i) and the corresponding commercially available isocyanates in CH2Cl2 (or CH3CN) at room temperature for 60 min or overnight; yield 50–90% (after flash chromatography purification).

Amides were prepared by established procedures using HATU (hexafluorophosphate azabenzotriazole tetramethyl uronium) [27].

Synthesis of amides 7a–c (Tables 1 and S2). Step i: Commercially available amine 7 was dissolved in a minimal amount of dimethylformamide (DMF) and stirred with the corresponding commercially available carboxylic acids and hexafluorophosphate azabenzotriazole tetramethyl uronium (HATU; both starting compounds and HATU in equimolar amounts), with a catalytic amount of DMAP, at room temperature for 12–24 h to give the desired 7a–c in moderate yields. Upon completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed under vacuo, and the remaining residue was extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc). The crude product was separated via column chromatography using mobile phase ratios of 0–100% EtOAc:MeOH.

The general procedure for the preparation of acyclic amides 7d–f and sulfoxides 7h–i (Figure 4, Tables 1 and S1) was adapted from previously reported methodology [28–31].

Synthesis of amides 7d–f (Tables 1 and S2). Step i: for the synthesis of N-(2-cyanophenyl)acrylamide, commercially available amine 7 (2.45 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (8.0 mL) and cooled to 0°C with stirring, followed by the addition of N, N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA; 0.70 mL, 4.00 mmol). Acryloyl chloride (0.16 mL, 2.00 mmol) was then added dropwise. After 5 min, the reaction was warmed to room temperature (RT) and stirred for one hour to obtain N-(2-cyanophenyl)acrylamide. Step ii: to the latter (0.17 g, 1.00 mmol), the appropriate thiophenol (0.22 mL, 2.00 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 50°C for 30 min to obtain amides 7d–f. The purified products were obtained in 60–75% yields after column chromatography [28, 29]; Step iii: sulfides 7d–f were oxidized with meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA), at 0°C for about 10–15 min, then at RT for 45 min to give sulfoxides 7h–i using standard procedures [30, 31].

Synthesis of N-substituted C-4 arylthio-β-lactams (Table S2). Step i: C-4 phenylthio β-lactams were prepared from the commercially available β-lactam 8 in the presence of NaHCO3 in acetone/water by an established procedure [25, 26]; Step ii: oxidation to sulfoxides 8a–d (Table S2) was accomplished using meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA) at 0°C for 10–15 min, then at room temperature (RT) for 45 min using standard procedures [30, 31]. The crude product was separated via column chromatography using mobile phase ratios of 0–100% ethyl acetate (EtOAc):MeOH.

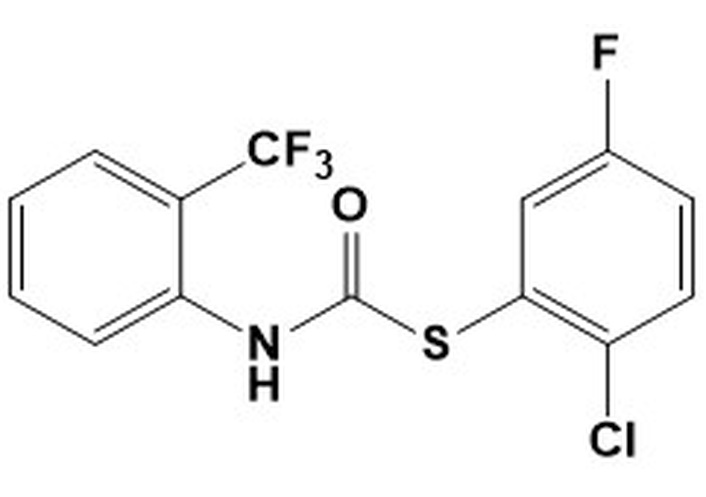

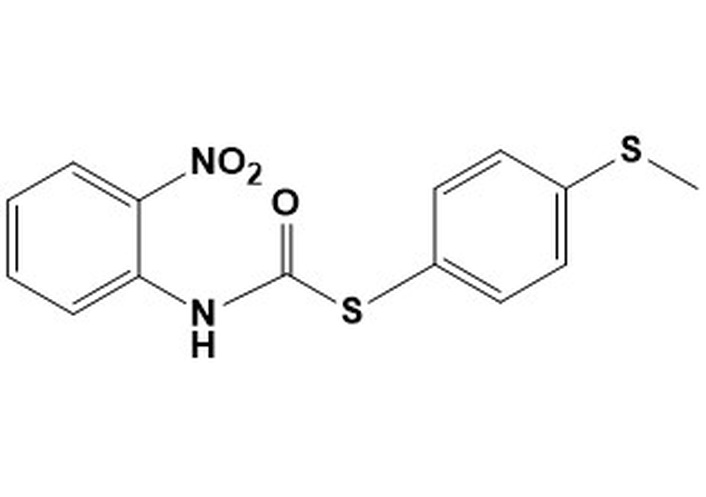

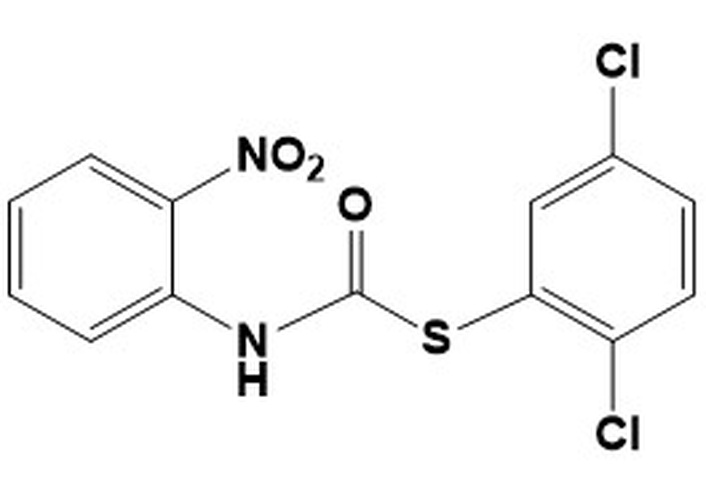

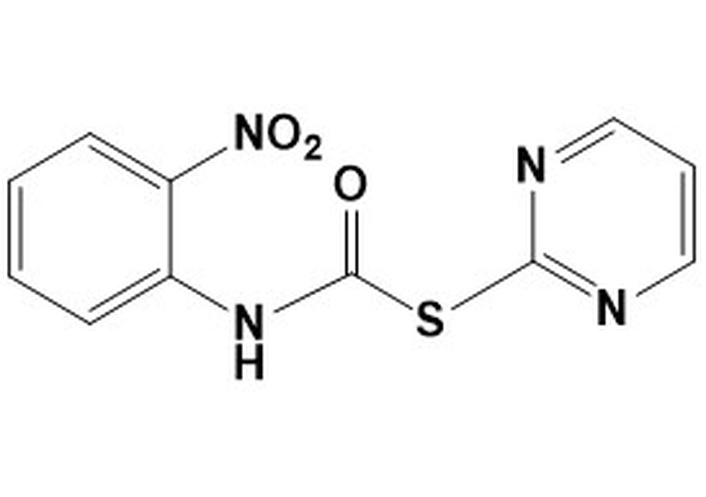

Synthesis of carbamothioates 9a–d (Table 1) and 9e–g (Table S2). Step i: commercially available ortho-substituted phenyl- and benzyl-isocyanates, respectively, were dissolved in CH2Cl2 or dimethylformamide (DMF) and stirred in a flask with the corresponding thiophenols, ArSH (in equimolar ratio in 1 mL of solvent per 1 mmol of reactant), at room temperature without a base for 1–24 h to give the desired 9a–g (30–70% yields) [32]. The crude products in most cases were above 90% pure; thus, whenever necessary, titration with hexane led to the isolation of pure products.

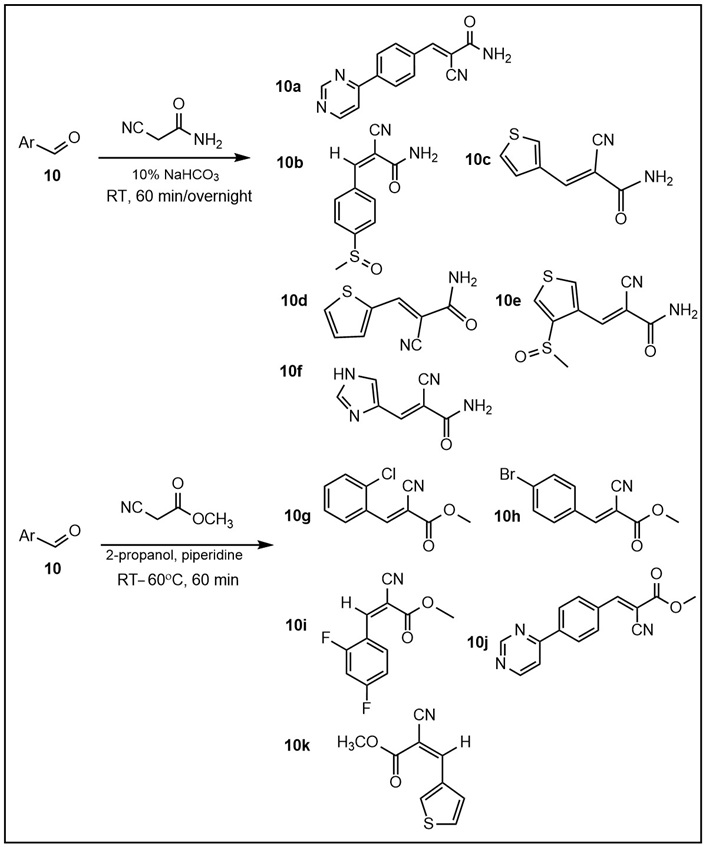

Illustrative examples of Michael acceptor syntheses using known procedures [33] (Table S2). Briefly, cyanoacetamide (80 mg, 1 mmol) was dissolved in 10% NaHCO3 (3 mL). To the solution was added the corresponding commercially available aldehyde 10 (0.9 mmol), and the reaction was stirred for 3 h to overnight at room temperature (RT). The product was isolated by filtration, washed with water, dried in vacuo, and, in most cases, used without further purification based on its purity (MS). Using methyl cyanoacetate requires the use of alcohol (e.g., ethanol or 2-propanol) and an organic base (e.g., piperidine). The molar ratios of aldehyde:methyl cyanoacetate are the same as those for the aldehyde:cyanoacetamide; piperidine is added in the same molar equivalents as the aldehyde, in 3 mL of an alcohol.

Compounds from our library with antimycobacterial activity.

| StructureName (#) MW/LogP | M. marinum (µg/mL)Day 7 | Mtb (µg/mL)Day 14 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAST-Fe | 7H9 | GAST-Fe | 7H9 | 7H9aMedia A | 7H9bMedia B | 7H9cMedia C | |

| Ureas | |||||||

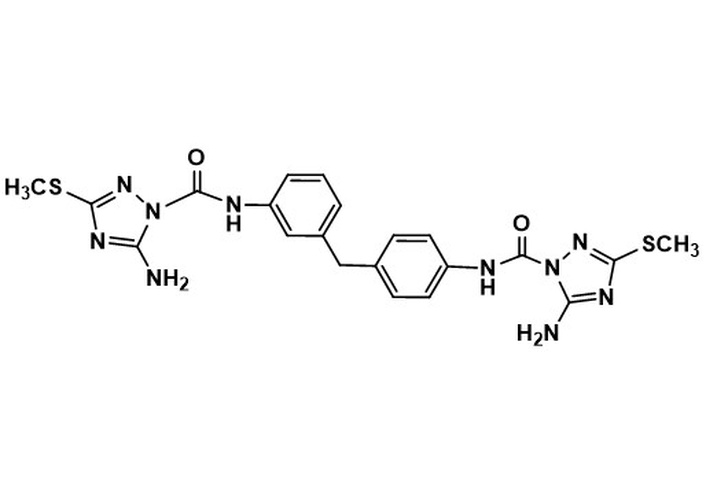

6c. 5-amino-N-(3-(4-(5-amino-3-(methylthio)-1H-1,2,4-triazole-1-carboxamido)benzyl)phenyl)-3-(methylthio)-1H-1,2,4-triazole-1-carboxamideMW 510.60LogP 2.68 5-amino-N-(3-(4-(5-amino-3-(methylthio)-1H-1,2,4-triazole-1-carboxamido)benzyl)phenyl)-3-(methylthio)-1H-1,2,4-triazole-1-carboxamideMW 510.60LogP 2.68 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 19.0 | 12.5 | 4.7 |

| Carbamothioates | |||||||

9a. S-(2-chloro-5-fluorophenyl) (2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)carbamothioateMW 349.73LogP 5.39 S-(2-chloro-5-fluorophenyl) (2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)carbamothioateMW 349.73LogP 5.39 | 9.375 | > 50 | 6.25 | 50 | nd | nd | nd |

9b. S-[4-(methylsulfanyl)phenyl] (2-nitrophenyl) carbamothioateMW 320.38LogP 4.54 S-[4-(methylsulfanyl)phenyl] (2-nitrophenyl) carbamothioateMW 320.38LogP 4.54 | > 50 | > 50 | 12.5 | 50 | nd | nd | nd |

9c. S-(2,5-dichlorophenyl)(2-nitrophenyl) carbamothioateMW 343.18LogP 4.95 S-(2,5-dichlorophenyl)(2-nitrophenyl) carbamothioateMW 343.18LogP 4.95 | 25 | 50 | 6.25 | 50 | nd | nd | nd |

9d. S-pyrimidin-2-yl (2-nitrophenyl) carbamothioateMW 276.27LogP 1.96 S-pyrimidin-2-yl (2-nitrophenyl) carbamothioateMW 276.27LogP 1.96 | > 50 | > 50 | 12.5 | > 50 | nd | nd | nd |

| Michael acceptors | |||||||

11. Compound A-analog 3-((5-(methylthio)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio)pyrazine-2-carbonitrileMW 267.34LogP 3.53 3-((5-(methylthio)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio)pyrazine-2-carbonitrileMW 267.34LogP 3.53 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 4.7 | 19.0 | 0.6 |

| Positive controls | |||||||

| Rifampicin | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.002 | 0.01 | nd | nd | nd |

Isoniazid MW 137.17LogP –0.64 MW 137.17LogP –0.64 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

7H9: Middlebrook 7H9-based medium supplemented with glucose/glycerol/BSA/Tween; in 7H9a with glucose/BSA/tyloxapol; in 7H9b with cholesterol/BSA/tyloxapol and in 7H9c with dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine/BSA/tyloxapol. Mtb: Mycobacterium tuberculosis; MW: molecular weight; GAST-Fe: glycerol-alanine-salts-Tween-iron; BSA: bovine serum albumin; nd: not determined.

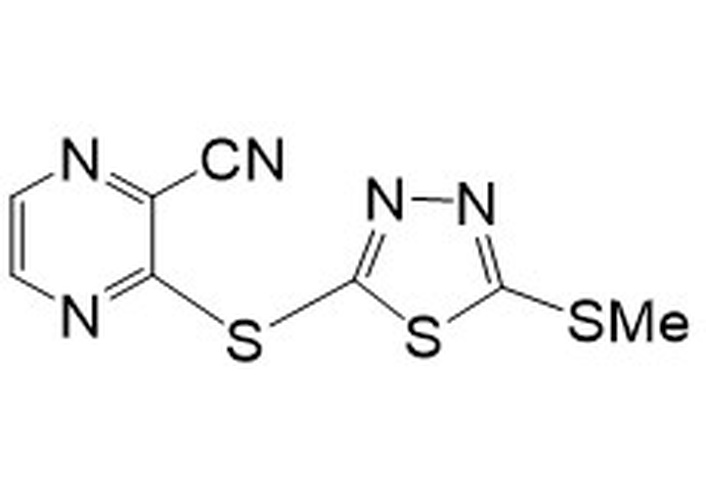

Compound 11 (Table 1, Figure 8) was prepared by the procedure described for the preparation of compound A, using 5-(methylthio)-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-thiol instead of 5-(ethylthio)-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-thiol [34, 35].

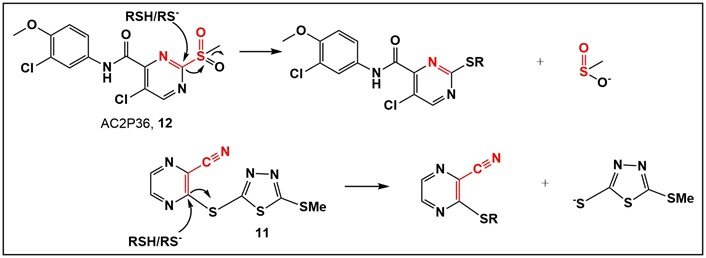

Comparison between the mechanism of action of AC2P36 (12, Table S2) and 11 (Table 1), upon nucleophilic attack of a thiol with departure of leaving groups, which are expected to be protonated at physiological pH. It appears that for both compounds with the best activity of either the urea or MA chemotype, compounds 6c and 11 (Table 1), lipophilicity plays an important role in addition to azole functionality.

Bacteria glycerol stocks were stored frozen at –80°C until use. Laboratory strains used for small compound fragment screening included: Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Enterococcus faecium, Proteus vulgaris, Mycobacterium marinum, and Mtb (Tables S3–6).

Antimicrobial testing: The ability of the synthesized small compounds and fragments to inhibit the growth of the microbes, i.e., minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), was determined. C. glutamicum (control for acid-fast susceptibility), as well as the Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, were grown overnight [Muller Hinton broth (MHB); 37°C]. These overnight cultures were then diluted in fresh MHB and regrown to early logarithmic phase [optical density of ~0.2 at 600 nm (OD600)]. The specific OD600 of the strains used for MIC testing is available in Table S3. MIC was determined using standard microdilution antibiotic testing methodology. Briefly, the test compounds were added to MHB (100 μL; 96-well clear, round-bottom plates) and then serially diluted (2-fold dilutions). This resulted in test compound concentrations that ranged from 100 μg/mL to 0.1 μg/mL, with the last column being drug-free. Logarithmic bacteria (50 μL) were then added to each well. Rifampicin was used as the positive control. All compounds were tested in biological duplicates, and MICs were noted on Days 1 and 3 as the lowest concentration that caused complete inhibition of growth as observed visually with the use of an inverted enlarging mirror.

All Mtb microbiology assays were conducted as previously described [25]. Mtb cultures were incubated (37°C) in the biosafety level 3 laboratory, while M. marinum was grown as described for Mtb, with the exception that M. marinum cultures were incubated at 30°C in the biosafety level 2 laboratory. M. marinum and M. tuberculosis H37Rv cultures were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth medium (Difco) supplemented with 0.2% (v/v) glycerol, 0.05% (v/v) Tween 80, and ADC supplement (BSA 5 g/L; dextrose 2 g/L; and NaCl 0.81 g/L). As needed, these organisms were also cultured in glycerol-alanine-salts-Tween-iron (GAST-Fe) medium consisting of 0.3 g/L bacto-casitone, 4 g/L dibasic potassium phosphate, 2 g/L citric acid, 1 g/L L-alanine, 1.2 g/L magnesium chloride hexahydrate, 0.6 g/L potassium sulfate, 2 g/L ammonium chloride, 0.05 g/L ferric ammonium citrate, 1% glycerol (v/v) and 0.05% Tween 80 (v/v), (pH 6.6).

For MIC testing, Mtb or M. marinum was grown to an optical density at 650 nm (OD650) of 0.2–0.3 in 7H9-based or GAST-Fe medium (Tables S4–6). Cells were diluted to a final OD650 of 0.0002 (1:1,000 of parent culture) in the desired medium. Two-fold serial dilutions of the test compounds were made in homologous medium (50 μL/well; clear round-bottom 96-well plate; from 50–0.012 μM). An equal volume of cells was then added to all the wells of the 96-well plate. The assay was performed in duplicate for each growth condition. The plates were incubated at 37°C (Mtb) or 30°C (M. marinum) in sealed ziplock bags, and MIC was recorded on Days 7 and 14 (Mtb) or Days 3 and 7 (M. marinum). MIC was noted as the lowest concentration of the test compound that inhibited visible growth at the given time point. INH and rifampicin were used as positive controls for Mtb, and rifampicin was used as the positive control for M. marinum MICs.

A focused library of 42 fragments and small molecules was assembled to identify a representative of each chemotype (if any) for anti-Mtb activity. Amide and urea chemotypes were chosen based on known compounds that demonstrated anti-mycobacterial activity [36] as well as inhibitors specifically of InhA (Mtb) [37, 38]. Trifluoromethylated derivatives of cinnamic acid as direct InhA inhibitors have been identified through a fragment-based screen against Mtb, M. smegmatis, and M. marinum [9, 39, 40]. While several analytical techniques, such as ligand-based NMR, X-ray crystallography, and molecular modeling, demonstrate that the fluorinated cinnamic acids bind to InhA, they do not demonstrate anti-Mtb activity [9]. These cinnamic acid fragments, although having the α,β-unsaturated functionality, do not appear to act as MA [39, 40]. These compounds’ interaction with the enzyme has similarity in binding to the known InhA inhibitor 2-(o-Tolyloxy)-5-hexylphenol (PT70) [40]. Thiocarbamates have also been reported to have anti-Mtb activity [41, 42]. Thiocarbamates (carbamothioates) have also demonstrated inhibition of the Mtb β-carbonic anhydrase 3 [42].

From the compounds derived from urea and amide chemotypes (both acyclic and cyclic), only one compound, the 1,2,4-triazole-containing urea 6c (Table 1), demonstrated activity against Mtb in all three media tested, i.e., glucose, cholesterol, and BSA-free dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPPC)-containing media. This compound showed the best anti-Mtb activity (4.7 μg/mL) in BSA-free medium. The measured differences in anti-Mtb activity in the presence vs. absence of BSA suggest an interaction between these compounds and BSA (Tables S3–5). Incorporating the azole moiety in these two chemotypes was based on the activity of the azoles as anti-Mtb agents [37, 38]. Of the three triazole-containing ureas, 6c (Table 1) and 6a, 6b (Table S2), the two that demonstrated activity, 6a (in all media tested), 6b (25 μg/mL only in BSA-free media), have similar lipophilicity. However, only the azole-containing urea 6c (Table 1) has promising anti-Mtb activity. It has been shown that azole-containing compounds inactivate the azole-efflux transporters [12, 43]. The presence of the azole in 6c, if active, would allow for its intracellular accumulation. The preparation of the cyclic amide chemotype represented by monocyclic β-lactams 8a–d (Table S2) was intended to evaluate the effect of the lactam ring (as compared to acyclic counterparts) on the antimicrobial activity. Oxidation of the sulfur atom was expected to increase the electrophilicity of the carbonyl carbon of the amides (8a–d, Table S2). However, none of the amides tested demonstrated activity.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria are also causative agents of various opportunistic human infections, which have been on the rise over the last decade. Unfortunately, current treatment has limited efficacy [44, 45]. In the literature, the term “thiocarbamate” is used to describe both thiocarbamate and carbamothioate functionalities. We focused on evaluating compounds with carbamothioate in their structure. Compounds 9a–d (Table 1) and 9e–g (Table S2) are representatives of the carbamothioate chemotype. Compounds with this functionality that are based on the salicylanilide scaffold have been identified as anti-Mtb and anti-nontuberculous mycobacteria (M. avium and M. kansasii) agents [41].

All carbamothioates in our library are diaryl-substituted, featuring either electron-withdrawing groups (EWG) or electron-donating groups (EDG) on the aryl substituents. Of the compounds prepared by us, those tested against M. marinum demonstrated modest anti-mycobacterial activity as compared to their benzyl-substituted carbamothioates. Of the di-phenyl substituted carbamothioates, those with the best MIC for M. marinum are compounds having EWG groups as the phenyl substituents. These are carbamothioate 9a (Table 1, with activity in all media tested, with the best MIC 6.25 μg/mL in GAST-Fe media); compound 9b and 9d (Table 1, activity shown only in GAST-Fe media, MIC 12.5 μg/mL); compound 9c (Table 1, with activity in all media tested, having the best MIC 6.25 μg/mL in GAST-Fe media). Both carbamothioates 9a and 9c (Table 1) feature a powerful EWG at the ortho position to the carbonyl carbon and at least one Cl atom on the thiophenyl substituent. This structural feature indicates the necessity for the carbonyl carbon to be electrophilic enough to facilitate a nucleophilic attack and also to render the aromatic thiol a suitable leaving group. Their mechanism of action most likely involves the release of aromatic thiolate upon nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon. In contrast, none of the di-phenyl carbamothioates with EDG demonstrated anti-mycobacterial activity.

The α,β-unsaturated systems, acting as reversible sulfhydryl binders 10a–k (Table S2) [34, 35], and the irreversible binder 11 (Table 1, Figure 8) [35], all of which act as MA, were prepared to evaluate their anti-Mtb activity. None of the reversible binders have anti-Mtb activity. However, the 1,3,4-thiadiazole-containing compound 11 (Table 1, Figure 8) demonstrated promising anti-Mtb activity in all three media, with the best (0.6 μg/mL) in casitone-containing media. Compound 11 (Table 1, Figure 8) differs from the known activator of human LCAT (lecitin: cholesterol acyltransferase) compound A by one methyl group (in the S-alkyl substituent of the thiadiazole; compound A has an S-ethyl group) [34]. LCAT catalyzes plasma cholesteryl ester formation and is defective in familial LCAT deficiency (FLD), an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by low high-density lipoprotein, anemia, and renal disease [35]. The activity of the MA acceptor 11 (Table 1, Figure 8) could be due to the presence of a thiadiazole substituent, similarly to the triazole-containing compound 13 (Table 1), the only active compound of the urea class. Thiadiazole-containing compounds have been demonstrated to act both as anti-Mtb/antibacterials [46–48] and antivirals [49].

It is possible that compound 11 (Table 1, Figure 8), regardless of being an MA, behaves similarly to the aforementioned trifluoromethyl cinnamic acids, i.e., not acting as an MA [39]. A potential mechanism of action of 11 (Table 1, Figure 8) may reside in its similarity to sulfone-substituted pyrazine AC2P36 (12; Table S2, Figure 8). The latter has been demonstrated to bind to thiols via nucleophilic attack on the pyrimidine, with the sulfone as the leaving group [50]. Compound AC2P36 (12; Table S2, Figure 8) is reported to directly deplete Mtb thiol pools, with enhanced depletion of free thiols at acidic pH [50]. The similarity in this activity for both compounds 11 and 12 is depicted in Figure 8.

In summary, of the compounds from our library, all 42 compounds tested exhibited good selective toxicity since they had no effect on the Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms or a non-mycobacterial acid-fast microbe screened in this study. In contrast, two compounds exhibited activity against Mtb. The two that demonstrated the best activity against Mtb (6c and 11, Table 1) possess an azole group; thus, our focus will be on their further evaluation as potential anti-mycobacterial agents.

While antibiotic resistance is increasing, there are only a limited number of selective inhibitors of mycobacteria [51, 52]. To address this need, we designed, synthesized, and tested a library (42 members) that included fragments and small molecules from various chemotypes. The focus of compound design was on the exploration of scaffolds with demonstrated promise as anti-Mtb agents, via their activity as direct and indirect InhA enzyme inhibitors. For example, INH, a mainstay in Mtb treatment, is an indirect modulator of InhA activity. InhA is a key enzyme in the FAS-II system, which is responsible for the elongation of very-long-chain fatty acids, specifically the meromycolic acids found in mycobacterial species, but absent in other acid-fast actinomycetes, i.e., C. glutamicum [53]. With this focus, the compounds synthesized were tested for their selective ability to inhibit M. marinum and Mtb, while not affecting C. glutamicum, a negative control for non-mycobacterial acid-fast cell wall synthetic pathways, as well as Gram-positive and negative bacteria.

The two compounds that displayed the most promising anti-Mtb activity, di-urea 6c (Table 1, LogP 2.68, MIC 4.7 μg/mL in BSA-free media) and compound 11 (Table 1, LogP 3.53, MIC 0.6 μg/mL, in BSA-free media), have an azole in their structures, i.e., 5-amino-3-(methylthio)-1H-1,2,4-triazole and 5-(methylthio)-1,3,4-thiadiazole, respectively. Future work on di-urea 6c will include determination of its toxicity profile and the preparation of several other (di)ureas containing the azole scaffold to attempt improving anti-Mtb activity. Since compound 11 (Table 1) is an LCAT activator, it could potentially act as a dual enzyme modulator, promoting the efflux of cholesterol from host cells, followed by its elimination from the body, and by inhibiting a crucial enzyme for Mtb. In addition to its promising anti-Mtb activity, studies on compound A (which has an S-ethyl group, rather than an S-methyl group, as in compound 11, Table 1) have demonstrated that it is non-toxic to mammalian hosts [34]. Therefore, compound 11 also appears promising for further development. In addition, future studies will be directed toward determining the mechanism of action of compounds 6c and 11 (Table 1) in Mtb. Furthermore, since Mtb and host cells compete for the same nutrients, anti-mycobacterial therapies that include both bacteria-directed and host-directed drugs will likely aid efforts to reduce the burden of Mtb infections globally.

BSA: bovine serum albumin

EDG: electron-donating groups

EWG: electron-withdrawing groups

FAS-II: type II fatty acid synthase

GAST-Fe: glycerol-alanine-salts-Tween-iron

INH: isoniazid

InhA: enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase

MA: Michael acceptors

mCPBA: meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid

MHB: Muller Hinton broth

MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration

Mtb: Mycobacterium tuberculosis

RT: room temperature

TLC: thin-layer chromatography

The supplementary materials for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1008145_sup_1.pdf.

The contributions of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) author(s) were made as part of their official duties as NIH federal employees, are in compliance with agency policy requirements, and are considered Works of the United States Government. However, the findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The authors would like to thank the American University and the Midwestern University Offices of Research and Sponsored Programs, as well as the Midwestern University College of Graduate Studies, for their support. MIK would like to thank the following students who participated in synthesizing the library of compounds: Alex Lutz, Marika Cohen, and Jason Corsbie.

MIK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. KA: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. HIMB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. BJP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Data available upon request. Requests for accessing the datasets should be directed to mkonak@american.edu.

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 337

Download: 15

Times Cited: 0

Irina Tiganova ... Yulia Romanova

Ebenezer Aborah ... Manuel F. Varela

Daniel Buldain ... Laura Marchetti

Ayuba Olanrewaju Mustapha ... Yusuf Oloruntoyin Ayipo