Affiliation:

Department of Pneumology and Allergology, “Nicolae Testemitanu” State University of Medicine and Pharmacy of the Republic of Moldova, MD-2004 Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3278-436X

Affiliation:

Department of Pneumology and Allergology, “Nicolae Testemitanu” State University of Medicine and Pharmacy of the Republic of Moldova, MD-2004 Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

Email: cristina.toma@usmf.md

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3075-7429

Explor Asthma Allergy. 2025;3:1009104 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eaa.2025.1009104

Received: September 24, 2025 Accepted: December 01, 2025 Published: December 22, 2025

Academic Editor: Giovanni Paoletti, Humanitas University, Humanitas Research Hospital, Italy

The article belongs to the special issue The Era of Biologics in Allergy

Background: The diversity of physiological actions and pharmacological effects of glucocorticoids (GCs) allows their use in a large group of diseases and pathological conditions. However, this treatment can be accompanied by a multitude of more or less severe side effects. As the mainstay of treatment for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) dramatically reduce morbidity and mortality. This research aims to examine the safety considerations associated with glucocorticoid therapy in patients with COPD and asthma.

Methods: The search was performed in PubMed, EBSCO, UpToDate, Medline, and Google Scholar for pertinent English-language articles published between 1990 and 2025, using the following keywords: glucocorticoids, asthma, COPD, management, and side effects.

Results: GCs stand out as one of the most widely prescribed classes of drugs globally, with well-established effectiveness in addressing acute or chronic inflammation, allergic conditions, and acute pathological situations. The undeniable efficacy of GCs, however, comes with a range of reported side effects. These include but are not limited to immunosuppression, cardiovascular issues, manifestation of Cushingoid features, development of diabetes, osteoporosis, suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and adverse effects on the gastrointestinal and dermatologic systems. However, the majority of these events are associated with systemic drug administration, which is less commonly indicated in the treatment of COPD and asthma. There are several factors and specific considerations when deciding on GC treatment in COPD. In the context of corticosteroid treatment for asthma, the overarching impact involves the suppression of inflammatory genes, leading to reduced transcription of genes responsible for cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, inflammatory enzymes, and receptors.

Discussion: GCs are associated with fewer side effects in both COPD and asthma treatment. It’s crucial to take into account factors such as the patient’s overall health, the severity of symptoms, the presence of comorbidities, and the responsiveness of specific features to GCs therapy.

The diversity of physiological actions and pharmacological effects of glucocorticoids (GCs) allows their use in a wide range of diseases and pathological conditions. With a proven track record of success in treating acute or chronic inflammation, allergic reactions, and acute pathological conditions, GCs are one of the most commonly prescribed drug classes worldwide. However, GCs are not without flaws, as their use is often accompanied by a variety of adverse effects, which can range from mild to severe. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the foundation of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) management, as they significantly improve the quality of life of patients, alleviate respiratory symptoms, promote lung function, prevent exacerbations, and reduce mortality [1]. The collected negative outcomes of systemic corticosteroids (SCS) in asthma are well-documented and involve cardiovascular disease (CVD), osteoporosis, cataracts, adrenal suppression, corpulence, and diabetes [2]. Even brief use of oral corticosteroids has been linked with considerable adverse results [3]. While little data exist on the systemic effects of ICS, emerging evidence suggests substantial systemic absorption. Two recent investigations have underscored this worry: one meta-analysis of hypothalamic-pituitary axis information from numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) estimated that roughly two-thirds of high-dose ICS achieve systemic uptake [4], while another large-scale metabolomic profiling study identified significant adrenal suppression even with low-dose ICS therapy in asthma [5]. Although the potential adverse effects of ICS use have been extensively investigated in COPD, with particular focus on diabetes, pneumonia, and bone density loss, data specific to asthma remain limited and conflicting [3, 6].

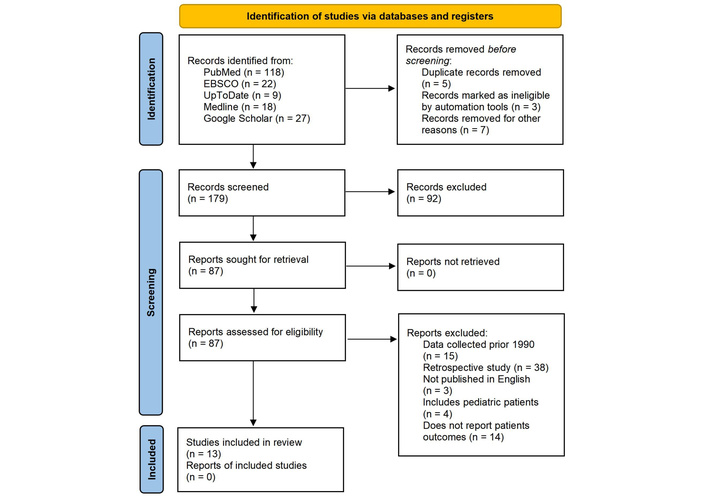

We performed the search in PubMed, EBSCO, UpToDate, Medline, and Google Scholar. Studies that examined the association between COPD and/or asthma and corticosteroid therapy, including its side effects, were included. Articles had to be written in English, with no restrictions on the year of publication, country of publication, or study design (Figure 1).

Flow diagram of the screening process. Reprinted from https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71.short without modification. Accessed November 20, 2025. © 2021 The Author(s). Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Characteristics of the main included studies are presented in Table 1.

Characteristics of the main included studies.

| First author (reference) | Participants (n) | Primary efficacy outcome | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipson et al. [7] | 10,355 | The frequency of moderate to severe treatment-related worsening events per year. | The combination of fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol demonstrated superior effectiveness in reducing the frequency of serious COPD flare-ups compared to either fluticasone furoate and vilanterol alone, or umeclidinium and vilanterol together. Furthermore, this triple therapy regimen led to fewer hospital admissions for COPD-related reasons compared to the umeclidinium-vilanterol combination. |

| Yang et al. [8] | 49,982 | The associations between ICS treatment and the risk of pneumonia in COPD patients. | ICS therapy elevates the likelihood of pneumonia development among COPD sufferers. This heightened risk is particularly noticeable with ICS formulations that include fluticasone, whereas budesonide-based ICS appear to have a lesser impact. |

| Calverley et al. [9] | 6,112 | Mortality rates across all causes were evaluated, along with the incidence of flare-ups, overall health conditions, and lung function measurements, when comparing the combined treatment to a placebo. | Although the combination therapy group showed a decrease in deaths across all causes, this decline was not statistically significant enough when contrasted with the placebo group, failing to reach the established threshold. During the 3 years of the study, treatment with the combination regimen resulted in significantly fewer exacerbations and improved health status and lung function, as compared with placebo. |

| Beech et al. [10] | 75 | This research explores the distribution of COPD subtypes, determined by analyzing sputum samples for both inflammatory cell types and the presence of specific bacteria using qPCR technology. A key area of interest is understanding the frequency of the COPD subtype characterized by high levels of H. influenzae bacteria and neutrophils, as well as investigating if the eosinophilic subtype exists separately from H. influenzae colonization. | The rate of H. influenzae colonization was roughly 25%, compared to low colonization for other bacterial species. H. influenzae colonization is associated with sputum neutrophilia, while eosinophilic inflammation and H. influenzae colonization rarely coexist. |

| Lea et al. [11] | 20 | The objective is to determine the responses of COPD macrophages to H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, and S. pneumoniae, with a focus on the release of chemotactic mediators and the expression of proteins that regulate apoptosis. | Differential cytokine secretion by macrophages in response to common bacterial species associated with COPD may elucidate the pronounced neutrophilic airway inflammation linked to H. influenzae, while not accounting for that associated with S. pneumoniae. Additionally, the regulation of macrophage apoptosis may serve as a significant mechanism contributing to the ongoing colonization of H. influenzae in individuals with COPD. |

| Yang et al. [12] | 23,139 | To assess the advantages and disadvantages of ICS administered alone compared to a placebo in individuals with stable COPD, focusing on both objective and subjective outcomes. | The use of inhaled ICS as a standalone treatment for COPD is likely to lead to a decrease in the rates of clinically significant exacerbations. It may also contribute to a reduction in the decline of FEV1, although the clinical significance of this effect remains uncertain. Additionally, ICS is likely to produce a modest enhancement in health-related quality of life, though this improvement does not reach the threshold for a minimally clinically important difference. |

| Janson et al. [13] | 9,893 | Yearly pneumonia event rates, admission to hospital related to pneumonia, and mortality. | There is an intraclass difference between inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist regarding the risk of pneumonia and pneumonia-related mortality in the treatment of patients with COPD. |

| Morjaria et al. [14] | 5,992 | The objective is to assess the incidence and frequency of pneumonia episodes and exacerbations of COPD among patients who are enrolled in the study, categorized by their use of no ICS, fluticasone propionate (FP), and other ICS formulations. | The use of ICS was linked to a rise in the rates of respiratory adverse events; however, it remains unclear whether this was a result of more severe illness at the time of entry. Subgroup analysis indicated that the increased morbidity in the ICS group was primarily associated with participants receiving FP at randomization. |

| Rabe et al. [15] | 8,509 | The estimated average number of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations experienced by each patient per year, based on on-treatment data from the modified intention-to-treat analysis. | Patients receiving triple therapy with twice-daily budesonide (at 160 μg or 320 μg), glycopyrrolate, and formoterol experienced a reduced rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations compared to those on glycopyrrolate-formoterol or budesonide-formoterol. |

| Pu et al. [16] | 1,375 | This study aims to conduct a meta-analysis and an indirect treatment comparison to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of various systemic corticosteroid (SCS) dosages in individuals experiencing COPD exacerbations. | For patients experiencing COPD exacerbations, a low-dose SCS regimen (starting at or below 40 mg prednisone equivalents per day) proved both adequate and safer compared to higher doses (starting above 40 mg PE/day). Furthermore, the lower dose was no less effective in improving lung function (FEV1) and preventing treatment failure. |

| Papi et al. [17] | 1,532 | A comparison was conducted between a single inhaler delivering beclometasone dipropionate, formoterol fumarate, and glycopyrronium (BDP/FF/G) and another single inhaler containing indacaterol and glycopyrronium (IND/GLY), assessing the frequency of moderate-to-severe COPD exacerbations over 52 weeks. | When compared to IND/GLY, extrafine BDP/FF/G offered a significant reduction in the rate of moderate-to-severe exacerbations for patients with symptomatic COPD, severe or very severe airflow limitation, and a history of exacerbations despite maintenance therapy, without an associated increase in pneumonia risk. |

| Patel et al. [6] | 5,102 | To review the latest scientific evidence of adverse systemic effects associated with ICS use in asthma (excluding adrenal insufficiency, which was recently reviewed elsewhere). | There are limited studies that suggest ICS use increases the risk of respiratory infections, cataracts, and loss of BMD in people with asthma; there were several biases and limitations associated with the studies. This review emphasizes the urgent need for further, carefully designed longitudinal cohort studies to better understand the risk of systemic adverse effects. These studies must be detailed enough to determine the specific ICS drugs, patient characteristics, and dosages that contribute most significantly to each adverse outcome. |

| Ekbom et al. [18] | 7,340 | The study aims to identify factors that increase the likelihood of pneumonia-related hospital admissions within the general population, with a particular focus on asthma and the role of inhaled ICS use in individuals with this condition. | There is a notable disparity in pneumonia risk across different ICS drugs, and FP stands out as a contributor to increased risk. |

ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PE: pulmonary embolism; BMD: bone mineral density; PE/day: prednisone equivalent/day; H. influenzae: Haemophilus influenzae.

Managing COPD involves ongoing, long-term therapy. The objectives of stable COPD therapy revolve around alleviating symptoms, minimizing the frequency and intensity of exacerbations, enhancing exercise tolerance, impeding disease progression, and enhancing overall health. Crafting the right drug regimen involves a thorough assessment of numerous factors: the degree of symptom manifestation, the probability of disease flares, any absolute or relative contraindications, essential precautions, the potential for adverse drug events, the practicalities of drug procurement and expense, and the patient’s individual inclinations and capacity for utilizing alternative therapeutic strategies.

The influence of ICS on a range of COPD-related outcomes, including lung function, mortality, airway inflammation, respiratory symptoms, and exacerbations, has been the subject of considerable scientific inquiry. Nevertheless, the data derived from these studies are characterized by conflicting evidence and a diversity of conclusions.

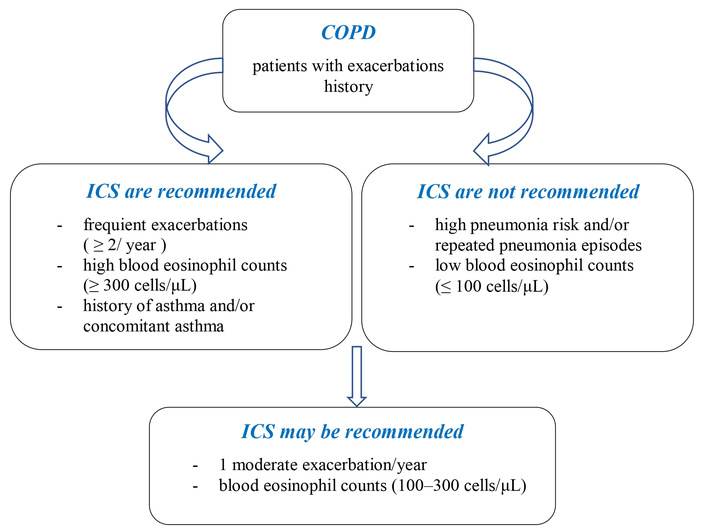

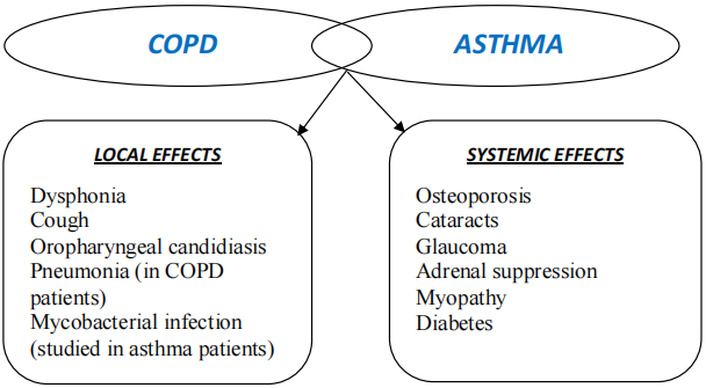

Nevertheless, when considering the collective evidence, it indicates that ICS therapy predominantly reduces exacerbations, has a modest impact on slowing the progression of respiratory symptoms, and may marginally contribute to an improvement in COPD mortality. Based on the current evidence at hand, there are several factors to consider when deciding on GC treatment in COPD. These factors may include the patient’s overall health, the severity of COPD symptoms, the presence of comorbidities, and the responsiveness of specific COPD features to GCs therapy [19, 20] (Figure 2). The combination therapy of LABA (long-acting beta-agonist) or LABA/LAMA (long-acting muscarinic antagonist) with ICS in COPD primarily aims to reduce the risk of exacerbations [21]. Conversely, ICS treatment in COPD can bring about several positive effects, including an increase in health-related quality of life [22, 23], improvement in dyspnea [23] and sleep [24, 25]. While some research suggests that COPD patients on ICS might benefit from a reduced risk of CVD [26] and lung cancer [27, 28], it’s equally important to be aware of the potential downsides. These include side effects such as oropharyngeal candidiasis, thinning of the skin or increased bruising [29], and an elevated risk of pneumonia (Figure 3) [8, 30–32].

Some clinical considerations for ICS treatment in COPD. ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The common local and systemic side effects of corticosteroids in asthma and COPD. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

When assessing the effectiveness of GCs and other anti-inflammatory medications in the management of COPD, the key clinical outcomes typically focus on exacerbation-related metrics. These include the exacerbation rate, the percentage of individuals who experience at least one exacerbation, and the interval until the first exacerbation occurs [33]. Certain inflammatory factors in COPD seem to respond to GCs, which significantly influence the onset and intensity of exacerbations. This understanding leads to the hypothesis that ICS therapy might help prevent or lessen the severity of COPD exacerbations, a concept reinforced by findings from numerous studies.

A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Yang et al. [12] revealed that ICS therapy significantly decreased the relative risk of exacerbations in comparison to a placebo [rate ratio (RR): 0.88; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.82–0.94, involving 10,097 participants]. This finding aligns with results from other publications [14, 15, 23, 34]. Lipson et al. [23] concluded that in contrast to the fluticasone furoate-vilanterol group (RR with triple therapy, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.90; 15% difference; P < 0.001) and the umeclidinium-vilanterol group (RR with triple therapy, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.81; 25% difference; P < 0.001). In the umeclidinium-vilanterol group, the annual rate of severe exacerbations leading to hospitalization was 0.19, while in the triple-therapy group it was 0.13 (RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.78; 34% difference; P < 0.001) [23]. Another study from 2020 reveals that the 320 μg budesonide triple-therapy group had an annual rate of moderate or severe exacerbations of 1.08, the 160 μg budesonide triple-therapy group of 1.07, the glycopyrrolate-formoterol group of 1.42, and the budesonide-formoterol group [15].

The Toward a Revolution in COPD Health (TORCH) trial, involving 6,112 patients with moderate to severe COPD, revealed that ICS therapy significantly lowered the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations (RR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.76–0.89) as well as the frequency of exacerbations necessitating systemic GCs (RR 0.65; 95% CI, 0.58–0.73) when compared to placebo [30]. However, it’s worth noting that ICS therapy in the TORCH trial did not show a significant reduction in the rate of severe exacerbations necessitating hospitalization.

The IMPACT [35], ETHOS [15], and TRIBUTE [17] trials undertook comparisons between a single, once-daily inhaler containing ICS, a LABA, and a LAMA with a combined LABA/LAMA inhaler and other therapies. Across all trials, the ICS/LAMA/LABA group demonstrated a reduced annual rate of moderate to severe exacerbations compared to the LAMA/LABA group. This reduction translated to an absolute improvement of roughly 0.1 to 0.3 events per year, with a relative risk around 0.80. The IMPACT trial additionally observed a reduction in hospitalizations due to exacerbations (0.13 versus 0.19 per year, RR 0.66).

Patients who may gain the greatest advantage from ICS treatment are typically those who face exacerbations unresponsive to other inhaled therapies or those presenting with high eosinophil counts (Figure 1). Post-hoc analyses of IMPACT, ETHOS, TRIBUTE, and other trials [30–32] suggest that the advantages of ICS tend to increase in patients with higher, rather than lower, markers of eosinophilic inflammation [8].

COPD is widely recognized for its accelerated deterioration of lung function compared to normal aging. Early assumptions suggested that ICS could slow down this progression. To evaluate the effect of ICS therapy on the advancement of the disease, researchers often examine the yearly decrease in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). The largest randomized trial [9] and a meta-analysis of trials longer than two years [36] have both indicated that ICS therapy does have a modest effect in slowing the decline of lung function. The meta-analysis reported a slight slowing of the decline by 7.3 mL/year (95% CI 3.2–11.4 mL/year) in a sample involving 12,502 participants.

Historically, COPD was often characterized as a “corticosteroid-resistant” condition [30, 31]. However, RCTs have contradicted this notion, demonstrating that the clinical benefit of ICS treatment can be predicted by blood eosinophil count [8, 32, 37]. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) strategy recommends that patients on a single bronchodilator, who typically have one COPD exacerbation per year and a blood eosinophil count of ≥ 300 cells/μL, may benefit from opting for a LAMA/LABA/ICS combination therapy as an alternative to the standard LAMA/LABA combination [33]. On the other hand, blood eosinophil counts below 100 cells/μL suggest a minimal chance of benefiting from ICS. In cases where patients experience recurrent COPD exacerbations despite treatment with LAMA/LABA and have blood eosinophil levels of 100 cells/μL or higher, the GOLD guidelines advise advancing to triple therapy using LAMA/LABA/ICS. This approach has been linked to a decrease in exacerbation rates.

In the pathophysiology of COPD, a pivotal role is played by macrophages, which exhibit varying degrees of pro-inflammatory, regulatory, and phagocytic abilities [11]. COPD patients typically show an increased number of alveolar macrophages compared to control subjects [31, 32, 38, 39]. These cells, together with pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, produce the neutrophil-attracting interleukin (IL)-8 [8]. Nonetheless, macrophages in cases of COPD exhibit dysfunction, characterized by a diminished capacity to engulf and eliminate bacteria [11, 38].

A study conducted by Culpitt et al. [38] found that GCs were less effective in suppressing the release of IL-8 triggered by cigarette smoke and IL-1β in lung macrophages from COPD patients when compared to lung macrophages from smoking controls. A study conducted by Cosio and colleagues revealed that corticosteroids similarly inhibited the release of IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) triggered by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in lung macrophages from individuals with COPD and smoking controls. However, the inhibition observed in both groups was reduced compared to non-smokers [36]. Another study found that LPS-induced IL-8 release from COPD lung macrophages was more corticosteroid-insensitive compared with smoking and non-smoking controls, but the corticosteroid sensitivity of IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 was similar between groups [39]. Analyses of these studies frequently emphasize the idea that macrophages in COPD patients exhibit resistance to corticosteroids. Nevertheless, some recurrent findings stand out: the modest scale of any disparities between COPD patients and controls, the lack of universal differences across all cytokines, and the inconsistent corticosteroid responsiveness among pro-inflammatory mediators. Notably, IL-8 suppression displays relatively low sensitivity, even in control samples [38].

Researchers have investigated the reduced responsiveness of macrophage-derived IL-8 secretion to corticosteroids by examining lung macrophages exposed to Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae). The study revealed that IL-8 release was entirely unaffected by corticosteroid treatment in both healthy individuals and those with COPD [36, 39]. Macrophage exposure to H. influenzae induces prolonged production of IL-8 [11]. This exposure further leads to an increase in glucocorticoid receptor (GR) S226 phosphorylation, hinting that enhanced nuclear export of the GR might serve as a mechanism through which bacteria modulate the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids [10, 36]. This suggests the presence of a corticosteroid-resistant pulmonary macrophage-IL-8-neutrophil pathway in COPD. This is particularly evident in COPD patients colonized by H. influenzae, who typically exhibit increased levels of airway neutrophils [10]. The rise in neutrophils may stem from IL-8 secretion by macrophages that is unresponsive to corticosteroids. Additionally, pulmonary neutrophils in COPD exhibit reduced sensitivity to corticosteroid suppression of TNF-α and IL-8 when compared to blood neutrophils [10, 40].

A key observation from these studies is the heightened corticosteroid sensitivity found in non-smokers, while no significant differences were noted between smokers and COPD patients. This indicates that oxidative stress caused by smoking plays a crucial role in diminishing the effectiveness of corticosteroids in suppressing cytokine production by epithelial cells. Overall, most research has concentrated on the macrophage-driven innate immune response, highlighting that specific pro-inflammatory mediators display a certain degree of corticosteroid sensitivity. In summary, the majority of studies have primarily focused on the macrophage innate immune response, revealing that certain pro-inflammatory mediators exhibit relative corticosteroid sensitivity. However, the production of IL-8 appears to be more corticosteroid-insensitive, highlighting an IL-8-neutrophil recruitment axis that responds poorly to corticosteroids in COPD [40] (Table 2).

A summary of key corticosteroid-sensitive and corticosteroid-resistant pathways in COPD.

| ICS-resistance inflammatory pathways | ICS-sensitive inflammatory pathways |

|---|---|

|

|

TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor α; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The influence of ICS on mortality in COPD is generally modest. Evidence indicates that patients with severe forms of the condition, frequent exacerbations, and heightened eosinophilic inflammation are the ones who derive the most significant benefit. A meta-analysis encompassing 60 randomized trials and including more than 100,000 participants revealed a slight mortality advantage with ICS use when compared to regimens without GCs. Specifically, the odds ratio (OR) was 0.90 (95% CI 0.84–0.97), with the greatest benefits observed in individuals with elevated blood eosinophil levels and higher rates of exacerbations [41]. In the IMPACT trial, mortality rates were slightly lower in the ICS/LAMA/LABA (fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol) group (2.4%) compared to the LABA/ICS (fluticasone furoate/vilanterol) group (2.6%) and the LABA/LAMA (umeclidinium/vilanterol) group (3.2%) [35]. Another population-based cohort study found that new users of the combination of LABA and ICS had a slightly reduced risk of death compared with new users of LABAs alone [hazard ratio (HR) 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.97] [42]. Beyond COPD itself, cardiovascular events are a leading cause of mortality in patients with COPD, often surpassing respiratory-related deaths [43]. CVD is a highly prevalent comorbidity in COPD, affecting between 5% and 46% of patients, depending on the specific cardiovascular condition [44, 45]. The association between ICS and cardiovascular events in COPD remains a topic of debate. Post hoc analyses of RCTs [46], observational studies [47], and meta-analyses [48] suggest that ICS use may be associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events and cardiovascular-specific mortality in patients with COPD. Conversely, other meta-analyses have reported no significant association between ICS use and cardiovascular outcomes [49]. These conflicting findings likely stem from heterogeneity in study populations and designs, including variations in ICS dosage, drug class, and treatment duration, as well as the complex and potentially nuanced role of ICS in cardiovascular health. For instance, ICS has demonstrated a protective effect against all-cause mortality, though this effect appears more pronounced after six months of treatment, at low-to-moderate doses, and when using budesonide specifically [41]. Furthermore, a patient’s cardiovascular history may influence the ICS-CVD relationship, with some evidence suggesting that ICS use in COPD may reduce cardiovascular risk among patients with preexisting CVD, whereas no such benefit is observed in CVD-naive individuals [48]. A study from England concluded that ICS use did not reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), with the exception of heart failure (HF), likely due to a reduction in misclassified COPD exacerbations [50]. A study conducted by Ioannides et al. [50], involving 113,353 individuals with COPD (average age 67.9 years, 53.3% male), found no significant link between ICS prescriptions and a reduced risk of MACE (adjusted HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.95–1.02; p = 0.41). On the other hand, ICS use was associated with a lowered incidence of HF, particularly during the first six years of follow-up (average adjusted HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86–0.96; p < 0.001). The observed reduction in HF was primarily driven by ICS formulations containing mometasone furoate, beclomethasone, budesonide, or ciclesonide (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84–0.94; p < 0.001). Conversely, incident ICS use was associated with an increased risk of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.09–1.47; p < 0.001), though this association was not sustained beyond initial ICS exposure. No significant relationship was observed between triple therapy and MACE, and the results remained consistent regardless of patients’ cardiovascular history [50].

Patients with COPD face a greater susceptibility to pneumonia, particularly among those of older age and those whose condition is more severe. ICS have been associated with a higher likelihood of respiratory infections, potentially as a result of their influence on monocyte chemotaxis, bactericidal function, and cytokine synthesis [36, 39, 51], thereby increasing the risk of pneumonia [32], oropharyngeal candidiasis [52–54], mycobacterial [55–57] and upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs). Disparities in study methodologies and the criteria for defining pneumonia cases have led to significant fluctuations in risk assessments, indicating that the likelihood of pneumonia may vary depending on the particular ICS administered.

Findings from the Swedish PATHOS study [58] showed that COPD patients treated with fluticasone propionate (FP)/salmeterol had a higher incidence of pneumonia compared to those treated with the budesonide/formoterol regimen, with a RR (95% CI) 1.73 (1.57–1.90). Similarly, a large Canadian study reported a significantly increased risk of pneumonia with the use of FP, with a RR (95% CI) of 2.01 (1.93–2.10), while the association was less pronounced for budesonide, with a RR (95% CI) of 1.17 (1.09–1.26) [59]. The 2008 UPLIFT trial analysis also indicated a higher incidence of pneumonia in patients using FP compared to other ICS [60]. With an OR of 1.86 (95% CI 1.04 to 3.34), one of the meta-analyses from 2014 continuously emphasized the higher risk of pneumonia with fluticasone compared to budesonide [61]. Notably, caution is advised in interpreting these findings due to possible variations in pneumonia assignment across studies. Several studies have indeed reported a higher risk of pneumonia in patients using fluticasone furoate [41, 62, 63]. ICS and concomitant asthma are independent risk factors for pneumonia in COPD patients, according to the “ARCTIC” study, which was published by Janson et al. [31] in 2018. ICS use raised the risk of pneumonia by 20–30% in patients with a FEV1 ≥ 50%, according to the study, which indicated that COPD patients had a higher risk than controls [31]. Based on 38 studies (29 RCTs and 9 observational studies), Festic et al. [32] observed that pneumonia fatality and overall mortality were found to be lower in observational studies and not to be raised in RCTs, despite a substantial and significant rise in the unadjusted risk of pneumonia linked to inhaled corticosteroid usage.

Additionally, comparisons between treatment with fluticasone furoate/vilanterol/umeclidinium and budesonide/formoterol over 24 weeks showed a higher prevalence of pneumonia in the fluticasone furoate group [23]. Suissa et al. [59] found that the risk of pneumonia for patients using beclomethasone, flunisolide, or triamcinolone fell between that of FP and budesonide, with a RR (95% CI) of 1.41 (1.33–1.51). Despite these findings indicating a discrepancy between FP and budesonide in terms of pneumonia risk, a review by the European Medicines Agency in 2016 did not find evidence of a difference between different ICS drugs [64]. As of the present day, a variety of ICS options are available for the treatment of COPD. However, a notable limitation exists in the form of a lack of RCTs directly comparing these different ICS options in the context of COPD. Most of the existing data stems from observational studies primarily focused on evaluating the effectiveness and safety of budesonide in comparison to FP. However, there is a notable lack of research directly contrasting these two ICS with alternatives like fluticasone furoate or beclomethasone [22].

The best formulation, dosage, and treatment schedule for ICS in managing COPD are still unclear. Numerous large-scale clinical trials examining the effects of ICS in COPD patients have often employed comparatively high doses, such as 400 μg of budesonide administered twice daily or 500 μg of fluticasone taken twice daily [29, 65]. Other studies, such as ETHOS and IMPACT, have highlighted the advantages of incorporating a moderate dose of ICS-budesonide at 160 μg or 320 μg administered twice daily, or fluticasone furoate at 100 μg once daily—alongside dual bronchodilator therapy [15, 35]. Experts in North America suggest opting for low to moderate doses of ICS, except in cases where the patient exhibits both asthma and COPD. In cases where patients continue to experience exacerbations, they suggest the possibility of increasing the ICS dose [24, 29]. Individualized treatment plans and regular monitoring are crucial to adjusting doses based on the patient’s specific needs and responses.

ICS are favored over orally administered GCs due to having fewer and less severe adverse effects. This makes them a widely used treatment option for asthma and COPD. However, concerns persist regarding the systemic effects of ICS, particularly in specific populations such as older patients, infants, children, or when used over extended periods [2, 3, 16]. It is crucial for healthcare providers to carefully assess and monitor the risks and benefits of prolonged ICS use in these populations to ensure patient safety. The use of ICS alongside LABA or LABA/LAMA offers notable clinical benefits but is also associated with certain adverse effects. It is essential to thoroughly evaluate the advantages in comparison to the potential drawbacks. Insights from the PATHOS study revealed that the occurrence of exacerbations was roughly tenfold higher than that of pneumonia. This indicates that preventing exacerbations holds significantly greater importance than the heightened risk of developing pneumonia [13]. A 2018 analysis by Agusti et al. [37] determined that certain individuals with COPD experience advantages from incorporating ICS into their long-acting bronchodilator therapy, whereas others may not derive the same benefit. They underscored the importance of meticulously weighing the risks and benefits of ICS use for each patient on a case-by-case basis [37]. Key factors advocating for the use of ICS include frequent exacerbations, a blood eosinophil count (B-Eos) of ≥ 0.3 × 109/L, and the presence of concomitant asthma. Conversely, considerations favoring the avoidance of ICS involve recurrent pneumonia, a history of mycobacterial infections, and a B-Eos level of 0.1 × 109/L. Individualized treatment plans should take into account these factors to optimize patient outcomes [37].

The use of SCS in the treatment of COPD exacerbations has been a longstanding practice. However, the optimal dose and duration of SCS in this context remain controversial, and there has been a lack of head-to-head RCTs directly comparing different dosage regimens. Various guidelines offer varying recommendations regarding the appropriate dosage and duration of SCS for managing COPD exacerbations. For example, the Japanese Respiratory Society suggests administering oral prednisolone at a daily dose of 30–40 mg over a course of 7–10 days, while the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand suggests a 5-day course of 30–50 mg oral prednisolone [66, 67]. The GOLD 2017 guideline recommends a 40 mg/day oral prednisolone for 5 days. A comprehensive meta-analysis from China [16] concluded that low-dose SCS (initial dose ≤ 40 mg prednisone equivalent/day (PE/day) was sufficient and safer for treating subjects with COPD exacerbation, being non-inferior to higher doses of SCS (initial dose > 40 mg PE/day) in terms of improving FEV1 and reducing the risk of treatment failure. The authors highlighted the importance of validating these findings through direct comparisons in head-to-head RCTs.

Adverse effects resulting from the local accumulation of ICS in the oropharynx and larynx may arise, with the likelihood of such complaints being influenced by factors including the type of medication, dosage, administration frequency, inhalation technique, and the choice of delivery device [68]. In oral drug therapy, some medications are breathed, but the majority stay in the mouth or oropharynx. Only 10–20% of the medications were found to enter the lungs. The normal physiology of the oral mucosa deteriorates when drugs stay in the mouth [69]. Reduced salivary flow results in tooth decay and damage to the oral mucosa. One significant contributing factor to the development of tooth abnormalities is low oral pH. Oral pH is lowered when inhalers are used. Thirty minutes after using an inhaler, saliva’s pH falls below 5.5 [70]. Patients’ taste is altered by the combination of saliva and the pharmacological content of inhaled medications [52]. Additionally, inhaler treatments cause alterations to the oral mucosa and oral ulcers. Specifically, corticosteroid-containing inhaler medications lead to an increase in dry mouth and cough, as well as erythema and the development of candidiasis in the buccal mucosa, oropharynx, and lateral regions of the tongue. Dry mouth is one of the issues that inhaler users face. Dry mouth can be brought on by beta-2 agonists, anticholinergics, and inhalers containing corticosteroids. Dry mouth causes issues like burning and soreness in the mouth, trouble swallowing, and instability of oral prostheses. In the future, a dry mouth may result in ulcers, oral fissures, and a reduction in epithelial tissue [71].

Between August 2020 and January 2021, 208 patients with COPD who were receiving treatment at a university hospital and using inhaler medications—ipratropium bromide/salbutamol, budesonide, salbutamol administered via nebulization, and budesonide administered as dry powder inhalers (DPI)—were included in the study. Of the patients, 37.5% experienced oral redness, 15.4% had oral mucosal degradation, and 70.2% had dry mouth. The use of medications containing ipratropium bromide/salbutamol and combined treatment of ipratropium bromide/salbutamol and drug with budesonide effect showed a positive significant correlation with the deterioration of the oral mucosa (p < 0.05; p < 0.01), but there was no correlation between dryness in the oral mucosa and inhaler drugs (p > 0.05) [72].

Dysphonia, characterized by a hoarse voice, is a frequent issue observed among individuals using ICS. The prevalence rates fluctuate significantly, spanning from 1% to 60%, influenced by variables such as the demographic studied, type of device, dosage, duration of observation, and methods of data recording [53, 73–75]. There is limited data on hydrofluoroalkane (HFA)-based metered-dose inhalers (MDIs). However, HFA-based inhalers appear to present a reduced risk of dysphonia in comparison to the older chlorofluorocarbon (CFC)-based MDIs [75]. Using a spacer with the MDI may sometimes reduce the risk of dysphonia, although results vary [74, 75]. Budesonide DPI might pose a reduced risk of dysphonia compared to CFC-MDIs or FP DPIs [53]. A study on patients utilizing FP DPI revealed an overall dysphonia rate of 20%, which increased to 36% in women aged over 65 [76].

The development of ICS-associated dysphonia is influenced by multiple factors, such as laryngeal muscle myopathy, characterized by incomplete closure or bowing of the vocal cords during adduction, mucosal irritation, and laryngeal candidiasis. Dysphonia caused by myopathy or mucosal irritation is typically reversible once treatment is discontinued. Although this condition can be particularly debilitating for individuals like singers and lecturers who rely heavily on their voice, it may not substantially affect the majority of patients [77].

Oropharyngeal candidiasis, commonly known as thrush, can be problematic for patients using inhaled GCs [52–54]. Oral candidiasis is thought to result from the suppression of regular host defense processes at the oral mucosal surface [78]. It is more prevalent in elderly patients, those on concomitant oral GCs, immunosuppressants, or antibiotics, and individuals using high doses or frequent ICS administration [79, 80]. A systematic review of ICS trials for COPD found a higher risk of oropharyngeal candidiasis among ICS users compared to placebo (OR 2.65, 95% CI 2.03–3.46; 5,586 participants) [80]. Large-volume spacer devices for MDIs can help reduce oropharyngeal drug deposition, and rinsing the mouth and throat with water post-ICS use is an effective preventive measure.

Laryngeal candidiasis is an uncommon complication of ICS therapy, though it has been observed in up to 15% of patients experiencing dysphonia during treatment. In a large study conducted by Dekhuijzen et al. [52], patients receiving ICS/LABA had a greater incidence of oral thrush during the outcome period than patients provided non-ICS treatment (5.5% vs. 2.7% patients; adjusted OR 2.18 [95% CI 1.84–2.59]). During the outcome period, 72.2% and 17.3% of the total patients with oral thrush had one or two episodes, respectively [52]. A group from the Netherlands [81] found that in the first year following the start of ICS treatment, there was a noteworthy and clinically significant rise in the number of patients taking medication for oral candidiasis with ICS. The first three months are when the relative risk is highest, but it stays elevated for at least a year following the start of ICS.

In some case reports, isolated laryngeal candidiasis, which manifests as dysphonia and occasionally throat discomfort, has been associated with the use of ICS [74, 82, 83]. Rare cases of esophageal candidiasis have also been associated with high-dose ICS [84]. Regular monitoring and preventive measures are essential to minimize these risks.

Allergic contact dermatitis has been occasionally reported with ICS use, particularly with budesonide [85–88]. This condition usually appears as a red, eczema-like rash surrounding the mouth, nose, or eyes. Occupational contact hypersensitivity cases have been observed among individuals administering ICS [88]. Diagnosis is confirmed via patch testing, and most patients can switch to a non-cross-reactive ICS, such as beclomethasone, mometasone, or fluticasone [85].

Cough and throat irritation, sometimes linked to reflex bronchoconstriction, can arise when using ICS through MDIs. However, these effects are less frequent with HFA formulations compared to the older CFC versions. Transitioning to a DPI often mitigates these issues. Nonetheless, a small percentage of patients (1–9%) may continue to experience cough or dysphonia with DPI-based ICS, and in rare cases, individuals sensitive to milk might react to lactose residues present in some DPI formulations [68]. Other uncommon local ICS complications include perioral dermatitis, tongue hypertrophy, and increased thirst [73]. Regular monitoring and awareness of potential complications are critical for effective management.

The risk of systemic adverse effects from ICS depends on various factors, including the dose, delivery site, delivery system, individual glucocorticoid response, and comorbidities (e.g., age, sex, smoking status, dietary calcium and vitamin D, and activity level). Sporadic case reports of severe systemic effects from ICS are typically attributed to idiosyncratic pharmacokinetic handling of the drug [68].

Corticotropin (ACTH) production is reduced by systemic GCs, which results in suppressing the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, subsequently decreasing adrenal cortisol secretion. ICS therapy is unlikely to cause symptomatic adrenal suppression or acute adrenal crisis, especially within recommended doses [68]. For example, the Lung Health Study observed no effects of ICS on adrenal function over three years [89]. Regular monitoring and adherence to dosages are essential to mitigate systemic risks.

Long-term systemic glucocorticoid use can increase intraocular pressure and cataract risk. Although few studies focus on ICS-specific effects, long-term COPD studies found no difference in cataract occurrence between ICS and placebo [90–92]. Over 3,000 patients were studied in a population-based cross-sectional study to report an increase in the frequency of nuclear and posterior subcapsular cataracts with higher cumulative ICS doses [91]. Follow-up analysis ten years later showed significant cataract risk only for patients using both ICS and oral corticosteroids [92].

The effects of oral GCs on bone metabolism and osteoporotic fractures are well-documented. Studies on ICS-associated osteoporosis and fractures show conflicting results, as heavy ICS users often use oral or parenteral GCs. Most studies suggest that ICS doses below 800 μg/day (budesonide equivalent) minimally affect fracture risk, while higher doses may accelerate bone mineral density (BMD) decline and increase fracture risk [80, 89, 93–95]. Osteoporosis is a systemic characteristic of COPD, with a rate of 2–5 times higher than that of those without airflow obstruction in the same age group [96]. Current recommendations advise intermittent BMD assessments and treatment for patients with significantly reduced BMD [97].

SCS treatment is known to have psychiatric adverse effects. However, whether ICS causes psychological adverse effects in COPD patients is unknown. SCS use has been linked to psychiatric side effects, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and panic disorder; euphoria and mania are more likely with short-term use, whereas depression is more common with long-term use [98]. According to several studies, the incidence of mood or anxiety problems associated with SCS administration ranges from 13% to 67% [99]. Manic symptoms have been associated with corticosteroid use through a number of potential mechanisms. Increased dopamine activity, a neurotransmitter imbalance that has been linked to manic episodes, is one significant factor. Additionally, long-term cortisol elevation brought on by corticosteroid therapy can interfere with the HPA axis, which can lead to mood instability. Inflammation also plays a part since changes in inflammatory markers can affect mood and trigger manic episodes [100, 101]. Both systemic and ICS have been linked to executive cognitive impairment and an increased risk of mood and anxiety problems in adults. In one study, electronic medical records were examined for the existence of a concomitant mental condition in 3,138 individuals who had been taking oral corticosteroids for longer than 28 days [102]. Furthermore, after using oral corticosteroids for an extended period of time, 142 out of 3,138 experienced a mental illness. Anxiety was the most often reported mental illness, followed by depressive disorders and psychological sexual dysfunction. The development of psychiatric adverse events was significantly correlated (p < 0.001) with age, gender, and the type of steroid given. The likelihood and severity of irritability, sleeplessness, mood changes, and anxiety vary depending on the dosage and length of treatment. Compared to people with COPD alone, those with asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) may be more susceptible to anxiety and mood-related symptoms [103]. In contrast to COPD, where oral GCs are primarily used to treat acute exacerbations of COPD in order to shorten recovery times, improve lung function, and lower hospitalization rates, while GCs are indicated for long-term management of chronic inflammation and symptom prevention in asthma and patients will have a higher risk of side effects.

Although hot flashes from ICS are not frequently reported adverse effects, they could be an indirect result of systemic consequences, especially adrenal insufficiency, which can happen with long-term or high-dose use. The HPA axis suppression, which lowers the body’s own cortisol production and can cause an adrenal crisis under stress, is most likely the mechanism. Hot flushes and other problems with controlling body temperature are only two of the ways that this hormonal imbalance can show up [104].

Studies on ICS withdrawal show mixed results regarding its effects on lung function, symptoms, and exacerbations. The ISOLDE trial [105], conducted by Jarad N.A. in 1999, reported increased exacerbations following acute ICS withdrawal in previously treated patients compared to those never treated with ICS. Similar results, including FEV1 declines, were observed in other studies, such as COPE [106], COSMIC [107], and a UK primary care clinical trial, which reported a 50% increased COPD exacerbation risk within one year of ICS withdrawal [108].

The WISDOM study [109, 110] investigated the effects of stepped ICS withdrawal on exacerbations and FEV1 decline in severe COPD patients. Patients receiving triple therapy during a 6-week run-in period showed no increased risk of moderate or severe exacerbations with ICS withdrawal but experienced reduced FEV1. Notably, FEV1 loss (~ 40 mL) and exacerbation frequency were higher among patients with baseline blood eosinophil counts ≥ 300 cells/µL [111]. The SUNSET study confirmed these findings, linking FEV1 loss and increased exacerbations to higher baseline eosinophil counts in patients on dual bronchodilator therapy (Indacaterol/Glycopyrronium).

In Australia and New Zealand, the initial asthma management guidelines were published in the mid-1980s. In the interim, the British Thoracic Society, the Canadian Thoracic Society, the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) have all issued guidelines concerning the use of GCs in the treatment of asthma [112].

Inhaled GCs reduce airway inflammation, inhibit inflammatory cells, activate anti-inflammatory genes, and stop the expression of inflammatory genes. By boosting beta 2-receptor expression and function, they also improve beta 2-adrenergic signaling. For the majority of patients, the ultimate result is the management of asthma symptoms and indicators. Achieving effective symptom control, reducing the risk of asthma-related death and exacerbations, avoiding long-term airway restrictions, and addressing potential therapeutic adverse effects are the long-term objectives of asthma management.

Several studies [113–115] suggest that the majority of patients can achieve maximum clinical benefit with low-dose ICS. However, there is data indicating a significant increase in the number of adults with asthma being prescribed medium-dose or high-dose ICS [116–118]. A large portion of the oral corticosteroid-sparing effect linked to high-dose ICS is probably caused by their systemic absorption, according to studies comparing the dose equivalency of oral corticosteroids to ICS in terms of systemic effects [4, 119] have found that much of the oral corticosteroid-sparing effect associated with high-dose ICS is likely due to their systemic absorption. This highlights how crucial it is to understand this bioequivalency while prescribing high-dose ICS. Osteoporosis and bone fractures, cataracts, opportunistic lung infections and pneumonia, obesity, and diabetes are well-known adverse consequences of oral corticosteroid use (Figure 3) [2].

ICS exert their anti-inflammatory effects in asthma through various mechanisms. These mechanisms involve the activation of anti-inflammatory genes and the suppression of inflammatory gene expression, leading to changes in the expression of various molecules involved in inflammation.

There are two types of GR, GR alpha and GR beta, that play a role in glucocorticoid action. GR alpha facilitates the action of GCs, while GR beta potentially inhibits it [120]. The binding of the glucocorticoid/GR alpha complex to glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) within the promoter of glucocorticoid-responsive genes stimulates gene transcription, often encoding anti-inflammatory proteins [121]. For instance, GCs increase the expression of proteins that block the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways, such as secretory leukoprotease inhibitor and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) [122]. However, this interaction with GREs also contributes to many of the side effects of GCs [123], such as reduced bone synthesis due to interference with the transcription of genes like osteocalcin.

GR beta may act as an inhibitor of glucocorticoid action by antagonizing the binding of GR alpha dimers to DNA [124]. However, the amounts of GR beta are thought to be too small to cause significant inhibition of glucocorticoid effects. Familial glucocorticoid resistance [125, 126], resulting from a missense mutation of the GR hormone binding domain, causes global insensitivity to glucocorticoid action and leads to hyperandrogenism but is not associated with glucocorticoid resistance in asthma.

The overall effect of GCs is the suppression of inflammatory genes, leading to decreased transcription of genes encoding cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, inflammatory enzymes, and receptors. ICS primarily impacts inflammatory genes locally, making them effective in controlling asthma with relatively few adverse effects.

Certain patients, especially those with severe asthma, may exhibit insufficient response to GCs, including both inhaled and systemic formulations. Patients with severe asthma demonstrating inadequate response to high doses of GCs, in the absence of confounding factors such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), cardiac disease, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, COPD, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), or tobacco smoke exposure, are classified as “glucocorticoid-resistant” [127]. High doses of GCs, in this context, typically refer to a daily dose of 1,000 μg or more of inhaled FP, or 2,000 μg or more of triamcinolone, or their equivalents. The term “steroid-resistant” asthma implies a reduced anti-inflammatory response to GCs rather than issues related to drug absorption, metabolism, or compliance. Nonadherence to treatment may be assessed by checking serum levels of prednisolone or morning serum cortisol.

Glucocorticoid resistance in asthma is likely multifactorial, involving a combination of heterogeneous mechanisms. These could include things like infection [128–130], oxidative stress (directly or indirectly from cigarette smoking) [131], exposure to allergens (which causes Th2 cytokine expression), inflammation (such as Th17 and other cells producing IL-17), and a lack of vitamin D3. A person’s level of resistance may change over time due to things including exposure to allergens, viral infections, and cigarette smoking [132]. Understanding and managing glucocorticoid resistance in asthma pose significant challenges due to its complex and multifaceted nature.

Patients with glucocorticoid-resistant asthma typically exhibit a severe asthma phenotype, necessitating high-dose ICS and sometimes the chronic use of oral GCs to maintain asthma control [127]. Data from research programs such as the Severe Asthma Research Program and the Unbiased BIOmarkers in PREDiction of respiratory disease outcomes indicate that at least 30% of patients with severe asthma may require regular use of oral GCs to effectively manage and control their asthma symptoms [133]. This highlights the challenge of treating severe asthma cases that do not respond well to standard glucocorticoid therapies and underscores the need for alternative treatment strategies and personalized approaches for these patients.

Adverse effects associated with glucocorticoid resistance in people with asthma may largely emerge in the skin but tend not to be prominent in other extrapulmonary locations, such as the adrenal and bone. For example, a research by Brown et al. [134] found that the cutaneous vasoconstrictor response to beclomethasone dipropionate is considerably reduced in individuals with GC-resistant asthma, indicating a deficiency in the anti-inflammatory effects of GCs rather than in metabolic or endocrine effects. Despite this, patients with GC-resistant asthma may still develop Cushingoid symptoms. Furthermore, levels of urinary free cortisol and plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) remain within normal ranges among individuals with GC-resistant asthma, showing normal function of the HPA axis. Changes in bone metabolism produced by GCs in both GC-sensitive and GC-resistant patients appear to be comparable [135].

It is essential to note that the diagnosis of GC-resistant asthma should be made only after excluding other conditions that may be in the differential diagnosis of severe asthma. Patients should undergo a thorough evaluation for compliance with therapy, and other potential contributing factors should be considered before concluding that resistance to GCs is the primary issue [132, 136].

Assessment of sputum eosinophils or exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels may provide insights into predicting which patients are likely to respond to increased glucocorticoid doses [136]. Conflicting data exist regarding the correlation between these biomarkers and GC responsiveness. A percentage of FeNO higher than 50 parts per billion (ppb) in relation to FeNO levels indicates GC-responsive airway inflammation. Conversely, a FeNO level of less than 25 ppb indicates that there is little eosinophilic airway inflammation and therefore GC therapy is unlikely to be effective [137, 138]. These measurements can aid in tailoring treatment strategies for patients with asthma, helping clinicians make informed decisions about adjusting GC doses based on the individual’s inflammatory profile.

Resistance to inhaled and systemic GCs in asthma is often relative rather than absolute. This means that some patients who are less responsive to standard doses may still respond to higher doses or more prolonged courses of systemic GCs [127]. Systemic GCs remain the preferred treatment for asthma exacerbations. Early administration of SCS for severe asthma exacerbations is regarded as the standard of care and is globally recommended within the first hour of patient presentation [139], but efforts should be made to avoid their long-term use in asthma management [140]. Although SCSs are highly accessible and sometimes available over the counter, and thus frequently self-administered at home as rescue medication, it is noteworthy that their use extends beyond severe exacerbations to include moderate and even mild cases. Emergency SCS are often prescribed as part of asthma self-management plans for patients at risk of exacerbations. However, when not properly implemented, this strategy can result in inappropriate medication use and increase the risk of adverse events. Over-prescription of SCS may also reflect poor asthma control, often linked to factors such as inadequate adherence to ICS or incorrect inhaler technique. In addition, patients may use SCS not only for asthma but also for comorbidities commonly associated with the disease, including rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps, atopic dermatitis, urticaria, and conjunctivitis. Beyond asthma, SCS are widely prescribed for various conditions, sometimes even in the absence of strong supporting evidence [141]. For example, an analysis of U.S. national claims data showed that more than one in five adults received at least one outpatient prescription for short-term (< 30 days) SCS within a 3-year period [3]. These findings highlight the perception among prescribers that SCS are effective, inexpensive, and relatively safe medications. Interestingly, individuals with asthma often utilize SCS in combination with nasal corticosteroids and medium-or high-dose ICS, all of which have systemic bioavailability. Patients using both ICS and SCS may be at higher risk of steroid-related adverse outcomes because cumulative side effects of ICS treatment have been described [142].

The lack of response to GCs is thought to be caused by a variety of processes, including inflammation. This process is thought to be influenced by elevated levels of IL-2 and IL-4 as well as increases in the pro-inflammatory transcription factor activation protein (AP)-1. According to the theory, early glucocorticoid usage may reduce inflammation and maintain glucocorticoid sensitivity [143]. A course of systemic GCs may also successfully lower airway inflammation, increasing the patient’s sensitivity to inhaled GCs.

The bioavailability of inhaled GCs varies depending on the physical properties of the particular agent. Approximately 80% of ICS are swallowed, with the remaining portion deposited in the lungs. Lipophilic compounds, such as fluticasone and beclomethasone, are retained longer in lung tissue.

The absorption of ICS also varies among specific agents. Highly lipophilic drugs are relatively poorly absorbed orally (˂ 11%). On the other hand, non-lipophilic agents, such as budesonide, are somewhat better absorbed orally (˂ 20%). Given that all of the drug deposited in the lung eventually enters the systemic circulation, the overall absorption of ICS ranges from 20 to 40% of the administered dose [144]. A recent study from the United Kingdom concluded that short-term use of low-dose ICS was not associated with adverse effects. However, moderate to high daily ICS doses were linked to an increased, albeit infrequent, risk of cardiovascular events, pulmonary embolism (PE), and pneumonia [6]. Among 162,202 patients in the primary cohort, an association was observed between medium-to-high daily ICS doses and all studied outcomes. At medium doses (201–599 μg), the HR were as follows: MACE, 2.63 (95% CI, 1.66–4.15); arrhythmia, 2.21 (95% CI, 1.60–3.04); PE, 2.10 (95% CI, 1.37–3.22); and pneumonia, 2.25 (95% CI, 1.77–2.85). At high doses (> 600 μg), the HRs increased further: MACE, 4.63 (95% CI, 2.62–8.17); arrhythmia, 2.91 (95% CI, 1.72–4.91); PE, 3.32 (95% CI, 1.69–6.50); and pneumonia, 4.09 (95% CI, 2.98–5.60). No associations were observed with lower ICS doses. Patients with severe asthma may exhibit relative refractoriness to ICS, and achieving asthma control in these cases might require high doses of inhaled GCs. When asthma remains poorly controlled on a high dose of inhaled GCs, typically around 1,000 μg/day, and shows responsiveness to GCs, clinicians may consider further increasing the inhaled GC dose or switching to an inhaled GC with a smaller particle size. While evidence supporting the efficacy of doses above 1,000 μg/day is limited, some patients may benefit from higher doses of inhaled GCs. For example, in a double-blind study involving 671 patients with severe asthma [145], slightly greater efficacy was observed with fluticasone at 2 mg/day compared to fluticasone at 1 mg/day or budesonide at 1.6 mg/day. Individual patient responses can vary, and the decision to increase the dose should be carefully considered based on the specific needs and characteristics of the patient. Some research has indicated that GC sensitivity may fluctuate over time, leading to the clinical recommendation of instituting a trial of a higher dose of inhaled GC at regular intervals, even if previous attempts were not effective [146].

The systemic adverse effects associated with inhaled corticosteroid use in asthma have been a subject of limited and conflicting research [6]. While oral corticosteroid use is known to increase the risk of systemic adverse effects such as osteoporosis, bone fractures, diabetes, ocular disorders, and respiratory infections, the extent of these risks with ICS use remains less clear. Studies evaluating the dose equivalence of oral corticosteroids to ICS in terms of systemic effects have suggested that much of the oral corticosteroid-sparing effect observed with high-dose ICS is due to systemic absorption [4]. Even while long-term ICS treatment may result in systemic adverse effects, the advantages of ICS clearly exceed the dangers when administered in clinically appropriate doses [147]. Both short-term intermittent and long-term use of SCS carry significant risks [148]. A recent report estimated that 93% of patients with severe asthma had at least one comorbidity attributable to SCS exposure [149, 150]. Beyond morbidity, regular SCS use has been linked to increased all-cause mortality [150, 151]. For example, a countrywide Swedish cohort research found that asthma patients who regularly used SCS had a 1.34-fold increased chance of dying compared to those who did not [150]. Therefore, even with brief courses, SCS can quickly alleviate asthma symptoms; nevertheless, these advantages must be carefully balanced against any potential drawbacks.

The medical profession still believes that short, sporadic rounds of SCS are generally safe, despite the fact that the detrimental side effects of long-term SCS use are well known. But according to a nationwide French cohort research, 59% of patients with severe asthma got SCS in 2012, with an average of 3.3 courses per patient year [152]. According to a 4-year longitudinal study by Matsumoto et al. [153], patients with asthma who received more than 2.5 short courses of SCS (3–14 days) annually had lower Z-scores and significantly more BMD loss than those who received ≤ 2.5 courses. This suggests that more than two courses annually may have a detrimental effect on bone health. The risk of adverse events, such as pneumonia, osteoporosis, fracture, type II diabetes, CVD, cataracts, sleep apnea, renal impairment, depression/anxiety, and BMI increase, was significantly higher among those exposed to SCS, according to a matched cohort study by Price et al. [154] involving 48,234 SCS-naive patients. Importantly, risk increased in a dose-dependent manner, with as few as four lifetime SCS courses (0.5–1 g cumulative exposure) associated with harm. Similar findings were reported in a U.S. retrospective cohort study of 1.5 million insured adults, where 21.1% received at least one outpatient short-course SCS prescription within 3 years, and 8.8% received three or more. Patients with respiratory conditions who received SCS had significantly higher rates of sepsis, venous thromboembolism, and fractures [3]. Sullivan et al. [155] also showed that patients with ≥ 4 intermittent SCS prescriptions per year had a 1.29-fold higher risk of adverse events, including osteoporosis, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, gastrointestinal bleeding, and cataracts. Notably, even 1–3 courses per year were associated with increased risk, and cumulative exposure across years amplified toxicity. Type II diabetes is one of the most frequent adverse outcomes of SCS. Patients with an average daily dose ≥ 0.5 mg had a 15-year incidence of 37.5%, five times higher than those receiving < 0.5 mg/day [156]. Repeated steroid bursts (≥ 3 per year) further increased diabetes risk. Weight gain associated with SCS may worsen glycaemic control and contribute to diabetes-related comorbidities, including cancer, gastrointestinal and liver disease, osteoarthritis, kidney disease, sleep apnoea, respiratory disease, and depression [157]. In children, short-course SCSs are widely used despite limited safety data. A systematic review of 3,200 patients < 18 years found vomiting, mood/behavioral changes, and sleep disturbances as the most common adverse events, with significant HPA axis suppression in several trials [148]. This suppression increases the risk of adrenal crisis and impaired growth. Boys receiving at least five SCS courses during a seven-year period had a greater risk of osteopenia and a sex-specific, dose-dependent decrease in bone mineral accretion, according to the Childhood Asthma Management Program follow-up [158]. Biochemical studies also reported transient but significant decreases in osteocalcin, a bone growth marker, following SCS treatment, suggesting lasting effects on bone metabolism [159, 160]. Pharmacokinetic studies further indicate that repeated or higher-dose SCS can overwhelm 11β-HSD2 enzyme capacity, enhancing mineralocorticoid receptor activation and contributing to additional adverse outcomes. Collectively, these findings highlight the cumulative toxicity of short-course SCS and the need for careful risk-benefit evaluation in both adults and children [161].

The systemic adverse effects of long-term SCS use are well established. The most common serious comorbidities include osteoporosis and osteopenia, type II diabetes, obesity, CVD, and adrenal suppression. SCS use has also been linked to psychiatric manifestations such as insomnia, mania, anxiety, and aggressive behavior, as well as gastrointestinal disorders, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, infections, muscle atrophy, cataracts, glaucoma, bruising, changes in physical appearance, skin striae, and altered appetite [154]. A study from 2014 [162] concluded that compared to patients with severe non-prednisone dependent or mild-moderate asthma, those with prednisone-dependent asthma were 3.4 (95% CI: 1.0–10.8, p = 0.04) and 3.5 (95% CI: 1.3–9.6, p = 0.01) times more likely to have significant depressive symptoms, and 1.6 (95% CI: 0.7–3.7, p = 0.2) and 2.5 (95% CI: 01.1–5.5, p = 0.02) times more likely to have anxiety symptoms. The causality of the connection between prednisone-dependent asthma and anxiety and depression might be bidirectional. The most likely reason is that depression and possibly anxiety are a direct result of corticosteroid medication. Alternatively, people with asthma may become dependent on prednisone due to psychological stress. The failure to control asthma with inhaled medications alone or to stop taking oral corticosteroids after an acute exacerbation may be due to psychological stress, which is thought to increase perception of asthma symptoms or even more severe airway inflammation.

Regarding bone density studies, six studies focused on measuring BMD as the primary outcome [142, 163–167]. Direct comparisons between these studies were challenging, with three studies indicating a decrease in BMD [142, 164, 165], while the remaining three reported no change [163, 166, 167]. One study suggested an increased risk of fractures but no loss of BMD.

In terms of respiratory infection studies, specifically pneumonia, four observational studies considered pneumonia as a primary outcome [18, 168–170]. A higher risk of pneumonia was seen in all four investigations, but one study only found a higher risk with fluticasone and not budesonide [18].

Overall, while the benefits of ICS in managing asthma symptoms are well-established, the potential for systemic side effects with long-term use needs careful consideration. It is important to weigh the risks and benefits, and individual patient characteristics should guide the decision-making process. Studies examining the systemic adverse effects associated with ICS use in asthma have explored various outcomes. Here are the findings from studies on mycobacterial infections, ocular disorders, and other potential systemic effects.

The probabilities of mycobacterial infection in asthmatic patients using ICS were compared to those without asthma and not on ICS in two case-control studies. The odds of tuberculosis (TB) were studied in one study from South Korea (n = 2,779 patients over 20 years) [57], and the risk of TB and non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) was evaluated in another study from Canada (n = 1,091 patients over 66 years) [56]. Both studies found an approximately 50% increase in the odds of TB. The study by Brode et al. [56] established a significant increase in the odds of NTM-PD associated with fluticasone, but not budesonide.

The effect of ICS on cataract formation in a primary care population of more than 30,000 patients over 40 years of age was examined in a single case-control study [171]. Patients using an ICS had a substantially 5% higher chance of getting cataracts, according to the adjusted results. Oral corticosteroid use was taken into consideration in the study; however, cumulative ICS use was not.

The Fukushima group assessed the incidence of oral candidiasis in asthmatic patients receiving beclomethasone against fluticasone [54]. There were 86 healthy volunteers, 143 asthmatic patients receiving inhaled steroid treatment, and 11 asthmatic patients not receiving such treatment. Patients with asthma who used inhaled steroids had far higher levels of Candida spp. than those who did not. Additionally, it was significantly higher in asthmatic patients receiving fluticasone than in those receiving beclomethasone, and it was significantly higher in individuals with oral symptoms than in asymptomatic patients. The presence of Candida increased with the dose of fluticasone, but it did not correspond with the inhaled dose of beclomethasone.

Reduced salivary flow is the primary mechanism underlying oral disorders in asthmatic individuals. Other reasons include gastric reflux, poor oral hygiene, increased consumption of sweet and acidic liquids, impaired local immunity, and acid pH in the oral cavity caused by inhaled medications, especially dry powder.

Depending on many buffering processes, including bicarbonate, phosphate, urea, and amino peptides, saliva can help maintain a neutral pH in the oral cavity, occasionally reaching levels as high as 7.67 [172]. Oral clearance is correlated with the rate of secretion, and salivary flow permits a mechanical cleaning against food particles or microbiological agents. Because many inhalers have a low pH and beta 2 agonists have been shown to have a detrimental influence on the pace of salivary production, both parameters are compromised in asthma [173]. There was no decrease in salivary flow, according to three studies done between 1991 and 1998 regarding the effects of beta 2 short-acting agonists administered over a seven-day period. Salmeterol 50 μg + FP 100 μg twice daily for one month was administered to 15 patients with moderate persistent asthma. The results showed a decrease in salivary flow rate linked to an increase in dental plaque index and no change in salivary IgA [174]. In a different 2,001 trial, salmeterol, either by itself or in conjunction with beclomethasone, was used to treat thirty individuals with moderate to severe asthma for six weeks. It showed that both treatments caused damage to the oral mucosa without altering salivary flow, suggesting that gingivitis was not only prevented by it [175].

Patients with asthma and COPD may experience adverse effects from GCs, such as dry mouth, irritability, and insomnia. ICS are more likely to cause these adverse effects, whereas long-term or high-dose oral steroid treatment increases the risk of systemic side effects like anxiety and mood changes. The similarities are found in the possibility of these adverse effects because of how the medications function. The distinction is that each disease has a distinctive inflammatory mechanism, which affects the effectiveness of GCs and, thus, the necessity of these side effects.

The mainstay of anti-inflammatory treatment for asthma and, to a lesser degree, COPD is still GCs. Despite their widespread use, significant safety issues with both inhaled and SCS can overshadow their therapeutic value. With a focus on treatment rationale, patient selection, and the range of possible side effects, the current review aimed to provide an integrated, comparative, and clinically focused synthesis of current information addressing corticosteroid use in asthma and COPD. Our objective was to give clinicians a comprehensive resource that supports safer and more individualized treatment decisions by combining the results of the biggest and most recent studies.

Corticosteroids continue to offer significant therapeutic benefit in asthma, especially in eosinophilic or type 2-high endotypes. ICS continues to be the cornerstone of long-term management while lowering exacerbation rates and improving lung function. Reliance on repeated SCS bursts or extended courses is still problematic, though. Even with sporadic “short” courses that are typically thought to be innocuous, an increasing amount of research shows that SCS-related morbidity builds up over time. Repetitive SCS exposure is now linked to higher risks of metabolic problems, bone fragility, cardiovascular events, infections, and psychiatric disorders, as well as lower quality of life and functional ability-according to observational cohorts and pharmacoepidemiologic investigations.

This emerging understanding has shifted the focus toward steroid stewardship in asthma management. Strategies such as optimizing inhaled therapy, improving adherence and inhaler technique, using objective biomarkers (e.g., blood eosinophils, FeNO), and early introduction of biologic therapies in eligible patients have become essential components of reducing unnecessary corticosteroid exposure. The current review reiterates that while corticosteroids remain highly effective for many patients, minimizing cumulative SCS exposure is now viewed as a critical therapeutic goal.

In contrast to asthma, the role of ICS in COPD has evolved from broad application toward targeted use in specific subgroups. Although ICS can modestly reduce exacerbation risk in patients with eosinophilic inflammation or frequent exacerbator phenotypes, widespread use, especially in those without asthma-COPD overlap or without type 2 inflammatory signatures, confers little benefit and a clear increase in adverse events. High-quality evidence consistently demonstrates increased risk of pneumonia, nontuberculous mycobacterial infections, fractures, hyperglycemia, and systemic effects, particularly with long-term or high-dose ICS regimens.

This has prompted renewed emphasis on precision medicine in COPD. Biomarkers such as blood eosinophil counts, exacerbation history, symptom burden, and comorbidity profile are now integral to ICS decision-making, including both initiation and withdrawal. By synthesizing these data, our review provides a consolidated rationale for selective ICS prescribing and highlights the clinical scenarios in which corticosteroids are most likely to be beneficial or harmful.