Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Kolkata 700054, West Bengal, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-5037-7593

Affiliation:

2Department of Pharmacology, Sister Nivedita University, Kolkata 700156, West Bengal, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-4773-3817

Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Kolkata 700054, West Bengal, India

Email: somasundaram.niperk@nic.in

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2096-2552

Explor Asthma Allergy. 2026;4:1009105 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eaa.2026.1009105

Received: October 08, 2025 Accepted: December 25, 2025 Published: January 07, 2026

Academic Editor: Torsten Zuberbier, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany

The article belongs to the special issue Atopic Dermatitis – Pathology and Treatment Modalities

The symptoms of atopic dermatitis (AD), a chronic, recurrent inflammatory skin condition, include immunological dysregulation, severe pruritus, and malfunctioning of the epidermal barrier. Recent developments in our understanding of AD’s molecular and immunological pathways have shed light on the functions of cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, IL-31, and IL-22, as well as the impact of genetic mutations in filaggrin and other barrier proteins. Inflammation and barrier dysfunction are further aggravated by microbial dysbiosis, especially colonisation of Staphylococcus aureus. Treatment options include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, targeted biologics, and small-molecule inhibitors that alter the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) and phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) pathways, as well as Mn- and Fe-porphyrin ring-based topical formulations. Even with these advancements, tailored treatment and long-term illness control are still challenging to achieve. New strategies that emphasise gene therapy and microbiome restoration can potentially improve the accuracy and comprehensiveness of AD treatment.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a multifactorial, chronic and inflammatory skin disorder [1]. The abnormality is characterised by epidermal barrier dysfunction, immune dysregulation leading to triggered immune responses, neuro-immune modulation, gut dysbiosis, and mutations of genes such as filaggrin (FLG), or can be triggered by environmental factors [2]. It causes dry eczematous skin, itch, rashes, and blisters. The disease features include relapsing or recurrent clinical heterogeneity, concerning the onset of disease, lesion morphology, distribution, and severity of lesions, as well as their long-term persistence [3]. There are three distinct phases of AD: acute, subacute, and chronic, with symptoms ranging from vesicular eruptions to lichenification of the skin due to persistent itching [4]. It typically affects flexures, neck, eyelids, and extremities [5]. The disease prevalence is higher in children, at about 15–20% compared to 7–10% among adults [6]. The eczematous skin condition develops due to defects in the skin barrier’s integrity, often resulting from reduced lipid production, which leads to trans-epidermal water loss, making the skin easily permeable to microbes [7]. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) plays a crucial role; its toxins exacerbate inflammation, disrupt keratinocyte function, and accelerate barrier breakdown [7]. Conversely, an exaggerated type 2 helper T (Th2) cell response drives the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, and IL-31, which intensify itch and further compromise the barrier [8]. The NF-κB pathway plays a significant role in increasing inflammation in AD. The transmembrane protein 79 (Tmem79) gene, also referred to as matrin, and the FLG gene, encode proteins that play a central role in protecting epidermal barrier integrity. The mutations in these genes further weaken the immune defence, increasing susceptibility to allergic diseases and asthmatic conditions later in life [9, 10]. Several studies have also reported that AD has a negative impact on the quality of life, causing self-consciousness, sleep disturbances, concentration issues, and affecting development in children [11].

Reducing pruritus is one of the most critical goals in patient care, thereby improving the quality of life for individuals affected by AD. Conventional therapy options include topical corticosteroids (TCS) and antihistamines, which temporarily relieve itching, as AD is a non-histamine-triggered condition [12]. With the advancement of understanding of the pathogenesis, small-molecule inhibitors and targeted biologics have emerged as newer options for treating AD [13]. Current treatment guidelines for mild AD include basic skin care, such as moisturising the skin with moisturiser or emollients to prevent the intensity and frequency of flares. Emollients, such as collagen and shea butter, fill the gaps between the cracked corneocytes and smooth the skin texture [14]. Usage of TCS, topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), or topical phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors is the main treatment option for patients suffering from mild to moderate AD. Crisaborole 2% ointment is a PDE4 inhibitor formulation approved for use in patients 3 months or older [15]. For patients with widespread or severe AD, several other treatment options are considered. One of these is systemic therapeutic agents, such as corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and anti-metabolites, which are administered orally or in injectable biologics or immunomodulators [16]. Ultraviolet (UV)-based phototherapies are also recommended, depending on availability and disease severity [17]. In this review, we focus on covering the pathology of AD and various treatment modalities.

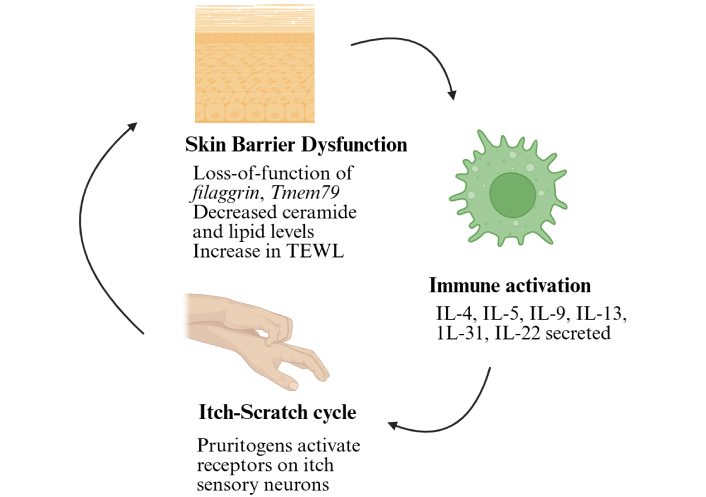

One of the key characteristics of AD is the compromised integrity of the skin barrier. The outermost layer of the skin, known as the epidermis, is rich in lipids, including cholesterol, cholesterol esters, ceramides, acyl ceramides, and free fatty acids. The outermost section of the epidermis, called the stratum corneum, consists of 15 to 25 layers of corneocytes. In this layer, surface proteins are cross-linked to ω-hydroxy ceramide, creating a lipid envelope around the cells. Beneath this, the stratum granulosum is the innermost layer of the epidermis. It contains secretory lamellar granules that release sphingomyelin, phospholipids, and glucosylceramides, which are then transported to other layers of the epidermis [18]. The skin’s stratum corneum typically contains ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids. With a decrease in ceramide and lipid levels, the epidermal layer is weakened, and the transepidermal water loss (TEWL) increases [19]. Alterations in FLG and other structural proteins, such as loricrin, involucrin, keratins, desmoglein, and desmocollins, further disrupt the epidermal layer, as illustrated in Figure 1 [20]. The FLG gene, a crucial component in skin health, consists of two introns and three exons. A loss-of-function nonsense mutation in the FLG gene, located in the third exon, has a profound impact on the FLG protein. This mutation results in a reduction in the number of FLG protein copies, depending on whether the mutation is homozygous or heterozygous. The severity of the resulting phenotype is influenced by the position of the gene on the third exon and the number of copies of tandem repeats encoding the FLG protein [10]. A frameshift nonsense mutation in the Tmem79 gene disrupted the lamellar granule secretion process, leading to alterations in stratum corneum formation and a spontaneous dermatitis phenotype. This damaged barrier allows allergens, microbes, and irritants to enter, triggering an immune response [9].

Mechanistic overview of atopic dermatitis. Various factors, such as loss-of-function mutations of filaggrin, Tmem79, or other structural proteins, a decrease in lipid and ceramide levels, and microbial colonisations, trigger immune activation, leading to the itch-scratch cycle. Tmem79: transmembrane protein 79; TEWL: transepidermal water loss; IL: interleukin. Created in BioRender. Arumugam, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/iodrcxa.

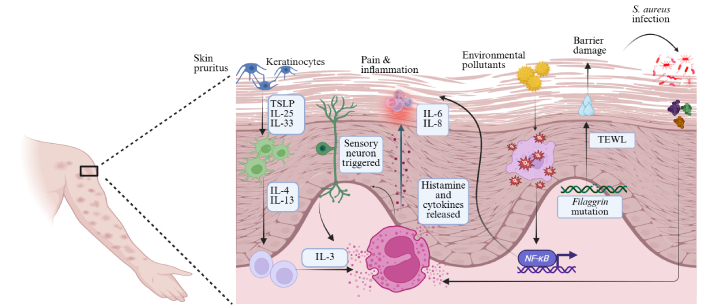

During the early stages of AD, Th2-mediated cytokines, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31, are elevated. As the disease progresses, acute lesions appear on the skin, resulting in an increased secretion of chemokines, including C-C motif ligand (CCL)-17 and CCL-22 [2]. These regulate and increase the production of IL-25 and IL-33, which are members of the IL-1 family. They further activate the ILC-2 and Th2 cells, where ILC-2 cells secrete IL-5 and IL-13, and the Th2 cells secrete the TSLP, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and IL-31 [21]. The cytokine superfamily, a key regulator of immune responses, governs various interactions between immune and non-immune cells, including keratinocytes, skin fibroblasts, and other cell types. Alarmins, a subset of cytokines, act as cytokine mediators or signalling molecules that activate immune responses by secreting TSLP, IL-33, and IL-25. Therefore, they act as central regulators of cutaneous immunity [22]. Children with AD show elevated oxidative stress markers, suggesting a disruption in the balance between oxygen and nitrogen radicals. Environmental pollutants, such as tobacco smoke and particulate matter, contribute to oxidative stress, causing inflammation and immune dysregulation. Oxidative stress activates the NF-κB pathway, which upregulates antioxidant enzymes but also induces proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, IL-9, and IL-33), thereby increasing dermal inflammation and worsening AD symptoms [23]. Fibroblasts, when the canonical NF-κB pathway is blocked by Ikkb gene deletion, exhibit a skin phenotype that closely resembles human AD-like skin lesions. These lesions are characterised by eosinophilia and a high number of type 2 immune cells. Our research reveals that skin fibroblasts, in addition to their traditional role in skin repair, play a critical regulatory role in immune homeostasis during early perinatal growth. They achieve this by modulating the activity of type 2 immune cells, a function regulated by Ikkb under normal physiological conditions [24]. These mechanisms have been illustrated in Figure 2. In the later stages of chronic AD, Th17 and Th22 cells are activated, suppressing the FLG expression, thus creating a disrupted skin barrier. The IL-4 and IL-13 also lead to the suppression of anti-microbial peptide formation, allowing microbes to enter the system. Both Th17 and Th22 cells actively secrete IL-22, which induces epidermal thickening, resulting in acanthosis, parakeratosis, and inflammation [25].

Cellular crosstalk in atopic dermatitis. Schematic representation of the complex cellular interactions in atopic dermatitis skin. The keratinocyte-immune-neuro crosstalk sustains pain, inflammation and itch. The gene mutations also create a self-perpetuating loop of barrier dysfunction, infection, inflammation and chronic pruritus. TSLP: thymic stromal lymphopoietin; IL: interleukin; TEWL: transepidermal water loss; S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus. Created in BioRender. Arumugam, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/iodrcxa.

AD is characterised by an increased sensitivity to itch, including alloknesis and hyperknesis. Alloknesis is where harmless touch stimuli, like light touches from clothing, trigger itching sensations, while hyperknesis refers to an amplified itch response to stimuli that usually provoke itch [26]. IL-31 is known to cause itching directly and is found in elevated levels in the lesional skin and serum of individuals with AD. Neurons that express IL-31 receptor (IL-31R) indicate a notable role in the perception of itch. Nerve elongation factors (NEFs), such as nerve growth factor (NGF), facilitate the growth of nerve fibres, whereas nerve repulsion factors (NRFs), like semaphorin 3A (Sema3A), inhibit this growth. In healthy skin, NRF levels are higher than those of NEF, which helps maintain a balance and restricts nerve fibre infiltration into the epidermis. However, in the affected skin of AD, there is an increase in NEF levels relative to NRF, facilitating the penetration of nerve fibres into the epidermis. It implies that a careful balance between NEF and NRF regulates the density of epidermal nerves. Thus, a balance between NEF and NRF16 regulates epidermal nerve density [27]. External and internal itch-inducing substances interact with and activate various receptors on itch sensory neurons. When activated, these receptors, including cytokine receptors, G-protein coupled receptors, and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, trigger action potentials. This activation leads to the immediate secretion of inflammatory substances, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P, highlighting the rapid response to itch-inducing substances [28].

AD is usually characterised by the dominance of a single species of microorganism, S. aureus. It has been reported in several studies that the presence of the bacterium S. epidermidis restricts the growth and colonisation of S. aureus. These bacterial colonies cause improper regulation of genes that play a role in epithelial barrier function, immune response, leukocyte movement, tryptophan degradation, and changes in metabolism [29]. Several studies also suggest that gut microbiota dysbiosis causes AD. The skin undergoes a process of renewal and turnover known as skin regeneration. After stem cells differentiate into epidermal cells, these cells undergo a process called keratinisation, which is governed by specific transcriptional mechanisms. The gut microbiome affects the signalling pathways that support epidermal differentiation, thereby impacting skin homeostasis [29]. Thus, this proves a correlation between gut microbes and skin health.

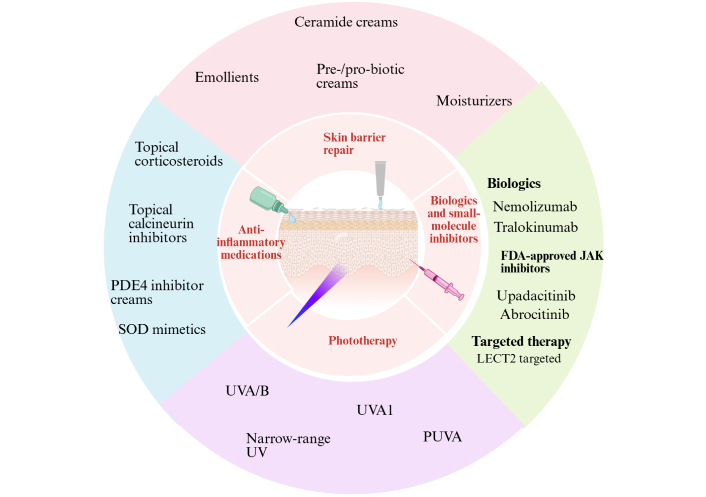

Various treatment modalities for AD are discussed below, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Various treatment modalities for AD. AD: atopic dermatitis; PDE4: phosphodiesterase 4; SOD: superoxide dismutase; UVA: ultraviolet A; PUVA: psoralen plus UVA; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; JAK: Janus kinase; LECT2: leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2. Created in BioRender. Arumugam, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/iodrcxa.

Repairing damaged skin is one of the most important goals in providing patient care in AD. Cocoa butter, shea butter, beeswax, olive oil, and grapeseed oil are a few natural alternatives for providing a physical barrier to the skin [30]. Daily usage of emollients reduces the dependency on TCS. Emollients, consisting of cholesterol, free fatty acids, and ceramides, are incorporated into lamellar bodies through topical administration, which enhances lipid synthesis and subsequent secretion into the intercellular lipid matrix. When compared with petrolatum-based occlusive moisturisers, an emollient containing a trio of lipids and a higher ceramide component (3×) was shown to promote hydration and decrease TEWL in AD patients. Honey, topical pre- and pro-biotics, thermal spring water, and vitamin E are a few natural alternatives to restore the skin and help in the growth of healthy microbiota [30, 31].

TCS are used as first-line treatment for mild to severe AD. TCS works by binding to and inhibiting the glucocorticoid receptors in skin cells. This action leads to the migration of these receptors to the nucleus, where they play a pivotal role in regulating the gene expression of key inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes [32]. The downregulation of transcription factors such as NF-κB is a crucial part of this process, thereby decreasing the secretion of downstream pro-inflammatory factors. Low-potency TCS, moderate-potency TCS, high-potency TCS, and very high-potency TCS formulations are available. Low- or moderate-potency TCS, such as 0.05% fluticasone propionate or 0.1% hydrocortisone butyrate cream, are prescribed for daily application for approximately 4 weeks. Meanwhile, high- or very high-potency TCS, such as betamethasone propionate and clobetasol propionate, are usually recommended for application only twice a week due to the risk of atrophy. TCIs are also a safe anti-inflammatory therapy and are typically recommended if there is concern about adverse events. Antiseptics or antimicrobials are also recommended if skin infections are present, in addition to AD. Topical PDE4 inhibitor, crisaborole 2% ointment, is approved for use in patients 3 months or older with AD. Topical Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, ruxolitinib 1.5% cream, is used in patients 12 years or older [12]. Leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 (LECT2) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several immune-mediated diseases. It plays a role in aggravating AD by downregulating skin barrier proteins and activating the NF-κB signalling pathway. Its modulation of inflammatory pathways identifies LECT2 as a potential therapeutic target in AD management, offering a ray of hope for future treatments [33]. Multiple metalloporphyrin-based superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetics, such as MnTE-2-PyP5+ (BMX-010, AEOL10113), MnTnBuOE-2-PyP5+ (BMX-001), MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, and FeTnHex-2-PyP5+, have demonstrated the ability to improve oxidative stress and itch in preclinical models. Among them, BMX-001 and BMX-010 have advanced to stage 2 clinical trials [34, 35].

Anti-metabolites, such as methotrexate, are administered orally. Systemic corticosteroids, such as prednisone, cyclosporine A, and azathioprine, are also administered for shorter durations, as prolonged use carries a risk of side effects [36]. Systemic immunosuppressants are usually given to moderate to severe AD patients. In a phase 3 clinical trial, nemolizumab, an IL-31R antibody, was administered to pediatric patients (aged 6–12 years) for 16 weeks and was found to be effective against pruritus from day 2 onwards [11]. Dupilumab, an antibody targeting IL-4 and IL-13, and tralokinumab, an antibody targeting IL-13, are both Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved biologics currently available. Lebrikizumab (Ebglyss) is also a biological agent approved by the FDA in September 2024 for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. It serves as a target for IL-13, which causes inflammation, itching and skin damage. Adults and children above 12 years of age can take it [37]. Upadacitinib and abrocitinib are FDA-approved JAK-1 inhibitors recommended for use if other systemic therapies fail to work to manage chronic AD [38]. Systemic corticosteroids and anti-metabolites are generally less expensive than biologics or targeted therapies.

For treatment of flares and xerosis, topical or systemic therapy is given alongside phototherapy. Thus, it is considered a second-line therapy. Various types of phototherapies are UV A (UVA)/B phototherapy, narrow band UVB phototherapy, UVA1 phototherapy, and psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) phototherapy [17]. UVA1 phototherapy facilitates the apoptosis of Th cells, thereby reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interferons. Phototherapy is usually recommended for adults over 12 years, considering the potential long-term risks associated with UV exposure. Studies have reported sunburn-like injuries and the dangers of skin cancers from prolonged exposure to UVA light. Also, the non-accessibility of phototherapy is a significant drawback. There is actually little evidence on different administrations of phototherapies [39]. Therefore, it is challenging to determine the most effective type of phototherapy currently.

AD is a complex condition; a universal strategy is ineffective. The frequency of AD in pediatric patients is a challenge for management and rescue. The correct kind of rapid diagnosis remains a challenge. As our understanding of disease pathophysiology has improved, several therapy options have emerged [40]. Systemic corticosteroids are one of the therapy options; however, long-term use might have adverse effects. Flares relapse after short-term use. Targeted biologics are not affordable to all patients [41]. Phototherapy is a second-line treatment to explore, and its dangers and benefits have yet to be investigated in significant numbers in clinical settings. Dual cytokine blockades in antibody therapy would help control the disease’s severity. Reports suggest that bivalent antibodies are currently being tested for AD. Several studies have demonstrated that restoring skin microbial diversity would help manage AD. Pro-biotic creams and bacterial lysates are being examined for their efficacy in inhibiting the growth of S. aureus colonies and balancing the skin microbiota flora [19]. Novel formulations, such as nanoparticles carrying ceramides or natural molecules like flavonoids, are being tested in vitro to understand their potency. Flavonoids such as quercetin and chrysin are naturally anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and have anti-allergic properties [42]. Nanocarriers containing natural lipid moieties are also screened. In cases of gene mutations, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas system can be tested to improve disease outcomes in individuals with very severe AD. Lastly, individualised treatment according to disease severity should be tailored to each patient to achieve the full benefit of the treatment modality [10].

AD: atopic dermatitis

CCL: C-C motif ligand

FDA: Food and Drug Administration

FLG: filaggrin

IL: interleukin

IL-31R: interleukin-31 receptor

JAK: Janus kinase

LECT2: leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2

NEFs: nerve elongation factors

NRFs: nerve repulsion factors

PDE4: phosphodiesterase 4

S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus

TCIs: topical calcineurin inhibitors

TCS: topical corticosteroids

TEWL: transepidermal water loss

Th2: type 2 helper T

Tmem79: transmembrane protein 79

TSLP: thymic stromal lymphopoietin

UV: ultraviolet

UVA: ultraviolet A

AS: Writing—original draft, Visualization. RS: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization. SA: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Somasundaram Arumugam, who is the Guest Editor of Exploration of Asthma & Allergy, had no involvement in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1694

Download: 36

Times Cited: 0

Gael Tchokomeni Siwe ... Stefan Barth

Serap Maden

Perpetua U. Ibekwe ... Bob A. Ukonu

Luis Angel Hernández-Zárate ... Víctor González-Uribe

Antara Baidya, Ulaganathan Mabalirajan