Affiliation:

1Laboratory of Morphophysiology, Multidisciplinary Institute of Biological Research—San Luis (IMIBIO-SL), National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET), San Luis D5700HHW, Argentina

2Faculty of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Pharmacy (FQByF), National University of San Luis (UNSL), San Luis D5700HHW, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7522-7208

Affiliation:

2Faculty of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Pharmacy (FQByF), National University of San Luis (UNSL), San Luis D5700HHW, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2620-0559

Affiliation:

1Laboratory of Morphophysiology, Multidisciplinary Institute of Biological Research—San Luis (IMIBIO-SL), National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET), San Luis D5700HHW, Argentina

2Faculty of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Pharmacy (FQByF), National University of San Luis (UNSL), San Luis D5700HHW, Argentina

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-3607-3248

Affiliation:

1Laboratory of Morphophysiology, Multidisciplinary Institute of Biological Research—San Luis (IMIBIO-SL), National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET), San Luis D5700HHW, Argentina

2Faculty of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Pharmacy (FQByF), National University of San Luis (UNSL), San Luis D5700HHW, Argentina

Email: gomez.nidia@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9549-1575

Explor Asthma Allergy. 2025;3:1009103 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eaa.2025.1009103

Received: September 30, 2025 Accepted: December 01, 2025 Published: December 11, 2025

Academic Editor: Pasquale Caponnetto, University of Catania, Italy

The article belongs to the special issue Asthma and its Relationship with Psychological and Psychopathological Factors

Asthma is one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases worldwide, traditionally defined as airway inflammation, reversible obstruction, and hyperresponsiveness. While this framework has guided decades of research and treatment, it fails to capture asthma as a heterogeneous and systemic condition. This pathology is shaped by complex interactions among genetic, epigenetic, immunological, neuroendocrine, metabolic, and environmental factors. Its coexistence with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in overlapping syndromes further complicates diagnosis and therapeutic decision-making. Asthma etiology involves oxidative stress, genetic susceptibility, and epigenetic regulation, along with age- and sex-dependent hormonal influences that modulate immune responses. Emerging evidence shows that structural and functional changes in the respiratory epithelium, airway smooth muscle (ASM), and alveoli extend the pathology beyond acute inflammation, involving processes such as epithelial barrier dysfunction, airway remodeling, and impaired mucociliary clearance (MCC). Neuro-immune-endocrine interactions have emerged as central contributors to asthma pathogenesis. Endocrine regulation shapes inflammatory activity and treatment responsiveness. Metabolic factors such as obesity introduce additional complexity by generating low-grade systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, adipokine imbalance, and steroid resistance, resulting in a distinct and often more severe asthma phenotype. Parasympathetic and sensory neural pathways amplify bronchoconstriction and inflammation through reciprocal communication with eosinophils, mast cells, innate lymphoid cells, and pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (PNECs). Neurotrophins and neuropeptides further promote airway hyperreactivity and remodeling. Current management integrates inhaled corticosteroids, bronchodilators, and targeted biologics—such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) inhibitors—alongside emerging non-pharmacological strategies. Psychological interventions, particularly mindfulness-based approaches, have demonstrated improvements in quality of life, stress reduction, and patient-reported asthma control, supporting the relevance of addressing the psychosocial dimensions of chronic disease. Understanding asthma as a systemic disorder underscores the need for personalized, multidimensional treatment strategies that integrate pharmacological, behavioral, and lifestyle components. This paradigm provides a more comprehensive framework for improving long-term outcomes and reducing the global burden of asthma.

Asthma is one of the most prevalent chronic respiratory diseases worldwide, affecting more than 300 million individuals and contributing significantly to morbidity, healthcare costs, and diminished quality of life.

Along with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the most common chronic obstructive pathologies, which represent a challenge for health systems due to their high prevalence. Although both diseases have different pathophysiological characteristics, they can coexist in the same individual, which complicates diagnosis and the choice of therapeutic strategies. This overlap of both pathologies is known as an overlapping syndrome. These complex and dynamic interactions underscore the importance of recognizing overlapping syndromes in clinical practice [1].

Asma is usually defined as a condition of airway inflammation, reversible obstruction, and hyperresponsiveness, and has been extensively studied through the lens of immunology. A new paradigm in chronic asthma suggests that the damaged respiratory epithelium is not fully repaired, leading to persistent structural and functional alterations. The consequence of this situation is a chronically damaged mucosa characterized by the secretion of secondary growth factors by epithelial cells and fibroblasts, capable of producing structural changes associated with remodeling of the airways.

Asthma has been studied in traditional terms, but it does not offer a complete view of the multidimensionality of this pathology. For this reason, systems-oriented medicine emerges, where transdisciplinary analytical strategies are applied based on the data generated by the omics sciences, allowing, in the long run, to predict the dynamic behavior of the disease. This leads to the view of asthma as a systemic process, underscoring the necessity of adopting a new paradigm for its understanding and management.

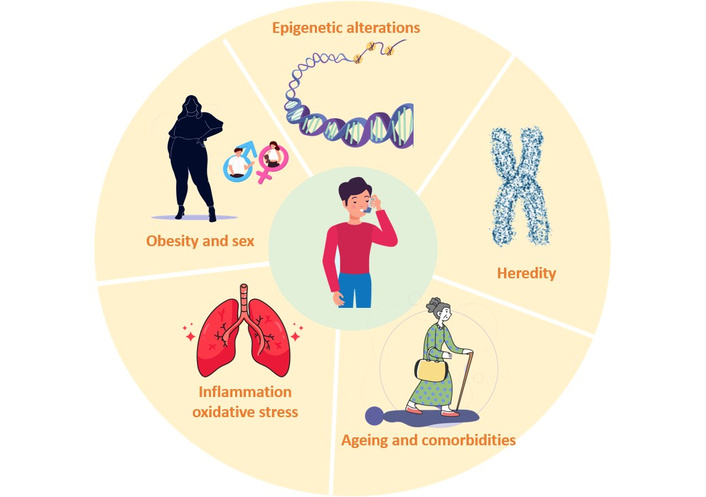

Asthma etiology encompasses interconnected pathophysiological mechanisms that contribute to the airways’ inflammatory state and bronchial hyperresponsiveness (see Figure 1). This disease has key factors that induce its development and progression that begin with oxidative stress and are continued plus amplified by the inflammatory cascade in the airways. Genetic components are now recognized in asthma susceptibility. With the advancement of technology, scientific efforts were made to understand asthma as a complex and heterogeneous disease with multiple phenotypes. In recent decades, genetic markers and loci associated with susceptibility to asthma, atopic asthma, and childhood-onset asthma have been identified. In addition, the most recent advances in this pathology focus on epigenetics, hereditary characteristics that affect gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. Epigenetic markers could be used to improve therapies and treatment guidelines [2, 3]. On the other hand, it has been found that it is more common in prepubertal boys but shifts toward a female predominance after puberty, where women experience higher morbidity in adulthood. Sex hormones modulate the immune responses, contributing to the disease progression. Estrogen enhances type-2 inflammation, increasing eosinophilic infiltration, and upregulates interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 expression, leading to greater airway hyperreactivity in women. Also, progesterone fluctuations correlate with perimenstrual asthma exacerbations, while testosterone appears to exert a protective effect, decreasing T helper 2 cells (Th2)-driven inflammation and airway remodeling [4]. Our laboratory showed that the latter would decrease in elderly men when testosterone levels go down [5]. Therefore, hormonal influences contribute to sex-specific asthma development and treatment responses.

Etiology of asthma: it is a complex and multifactorial disease that affects millions of individuals in the world. Within the host factors, we can include family history, genetics and epigenetics, sex, age, comorbidities, pulmonary inflammatory status, and oxidative stress. In addition to this, there are environmental factors that add greater complexity to the situation and that lead to the treatment of this multifactorial pathology being complex and requiring follow-up and individual treatments, with a high social cost.

In summary, the etiology of asthma reflects a multifactorial interplay in which oxidative stress, genetic susceptibility, epigenetic regulation, age, and sex-related hormonal influences converge to shape disease onset, progression, and clinical expression, and also molecular regulation when designing therapeutic and preventive strategies.

The epithelial barrier lines the inner surface of the airway wall, serving as the interface between the external environment and the respiratory tree. Consequently, the epithelium plays a vital role in pathologies such as asthma, a severe chronic condition characterized by structural damage and functional impairment. In this context, the structural integrity of the epithelium is maintained through cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions. Disruption of the pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium allows tissue-damaging agents and infectious particles to penetrate the airway wall, thereby facilitating toxic, immune, and inflammatory responses that lead to further tissue injury.

In the mucosal inflammatory response of asthma, airway components—including the epithelium, smooth muscle, vasculature, and nerves—interact with environmental factors such as allergens, fungi, bacteria, viruses, smoke, and pollutants. In developed countries, most cases of asthma are associated with atopy. To explain this paradox, key factors must translate the atopic phenotype into the lower airways, where it manifests as Th2-type airway inflammation. Type-2 inflammation is now recognized as the dominant immune response driving allergic asthma. The Th2 paradigm, emphasizing the role of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, as well as eosinophils, mast cells, and IgE, has shaped therapeutic approaches for decades. However, despite advances in immunomodulatory therapies and inhaled corticosteroid use, many patients continue to experience exacerbations or remain refractory to conventional treatment. By contrast, type-1 immunity is regulated by CD4+ Th1, which secrete IL-2, interferon-gamma (IFNγ), and lymphotoxins, thereby promoting a type-1 immune response characterized by pronounced phagocytic activity [6].

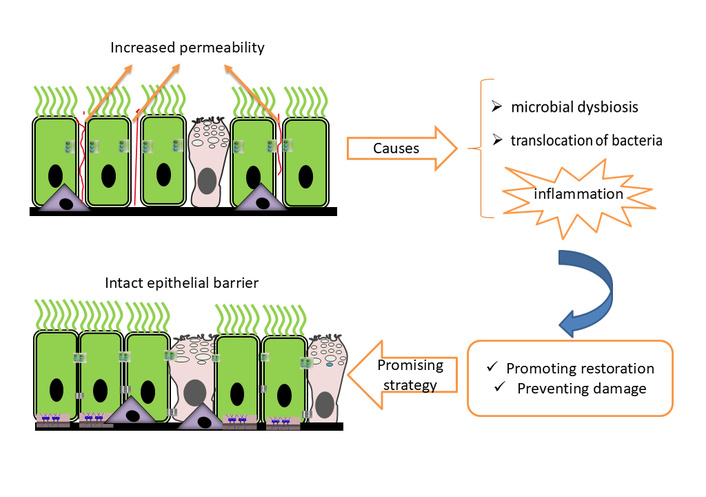

The epithelial barrier hypothesis has gained interest in the scientific community, particularly regarding diseases such as asthma. A permeable epithelial barrier allows microbial dysbiosis and bacterial translocation and contributes to epithelial inflammation. Therefore, promoting restoration or preventing damage to the airway epithelial barrier becomes a promising strategy for asthma treatment. Understanding the mechanisms leading to epithelial barrier dysfunction—induced by allergens, environmental pollutants, and other factors—is essential [7] (see Figure 2).

Respiratory epithelial barrier integrity and dysfunction. The epithelial barrier of the respiratory tree can be damaged in pathologies such as asthma, leading to increased permeability and facilitating the entry of pathogens, aeroallergens, and toxic substances. This is difficult to assess without the use of invasive methods, which highlights the importance of identifying biomarkers of respiratory epithelial damage.

In adults with persistent asthma, especially in severe and uncontrolled forms, chronic airway inflammation induces structural alterations that compromise long-term pulmonary function. Key processes include bronchial wall thickening, ASM hyperplasia, subepithelial fibrosis, and extracellular matrix remodeling. These changes are exacerbated when immune responses remain dysregulated.

Recent studies have identified the pivotal role of alveolar macrophages in this process. Their polarization toward M2 phenotypes, induced by cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13, promotes myofibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition, contributing to fibrogenic airway remodeling [8]. In this context, the NAVIGATOR clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of tezepelumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cytokine that activates multiple inflammatory pathways. The trial showed a significant reduction in asthma exacerbations, even in patients with low eosinophil counts, along with improvements in lung function and quality of life [9].

Morphological investigations have shown that ASM thickening and basement membrane enlargement may occur independently of granulocytic inflammation, as observed in paucigranulocytic asthma phenotypes [10, 11]. These findings suggest that certain components of airway remodeling are not exclusively linked to active inflammation. The respiratory epithelium also plays a significant role in asthma pathophysiology. Beyond its barrier function, it actively regulates immune responses through the secretion of cytokines such as TSLP, IL-33, and IL-25, which promote type-2 inflammation [12]. Epithelial dysfunction contributes to chronic inflammation, subepithelial remodeling, and disruption of pulmonary homeostasis.

Additionally, the MCC system, including ciliated cells, mucins, and periciliary fluid, serves as a critical innate defense mechanism for removing inhaled particles and pathogens. Its impairment, seen in chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma and cystic fibrosis, contributes to bronchial obstruction, persistent inflammation, and epithelial damage [13, 14].

Recent clinical and histopathological findings suggest that chronic asthma may also affect pulmonary alveoli, particularly in severe and prolonged cases. Autopsy studies and animal models have revealed features consistent with diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), including alveolar septal thickening, intra-alveolar exudate accumulation, type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia, and interstitial infiltration by lymphocytes and eosinophils [15, 16]. These alterations show that the inflammatory process in asthma may extend beyond the conducting airways, disrupting the alveolar-capillary barrier and impairing gas exchange. While not universally present, alveolar involvement may represent a continuum of tissue injury in severe asthma phenotypes, especially those with poor corticosteroid response or persistent environmental exposure.

The reviewed evidence highlights asthma as a heterogeneous disease with multiple pathophysiological mechanisms. These include type-2 inflammation, inflammation-independent structural remodeling, epithelial dysfunction, mucociliary impairment, and potential alveolar involvement. The recognition of remodeling processes that persist beyond granulocytic inflammation, as well as the emerging understanding of alveolar vulnerability, underscores the need for therapeutic strategies that go beyond symptom control. Targeting immune mediators such as TSLP and restoring epithelial integrity may offer promising avenues for mitigating long-term pulmonary damage and improving clinical outcomes.

Over the past two decades, new insights have revealed that asthma cannot be fully understood by immune processes alone. The nervous system, both central and peripheral, plays an essential role in sensing the environment, regulating airway tone, and communicating with immune cells. Similarly, the endocrine system, through glucocorticoids, sex hormones, neuropeptides, and neurotrophic factors, exerts a powerful influence on inflammation, remodeling, and responsiveness to therapy. The convergence of these systems (nervous, immune, and endocrine) has given rise to a multidisciplinary framework: neuro-immuno-endocrinology. This approach acknowledges asthma as a systemic disorder, in which the airway is a stage where deeper physiological interactions take place.

The airways are richly innervated by both autonomic and sensory nerves. Parasympathetic fibers of the vagus nerve exert powerful control over broncho motor tone through acetylcholine release, leading to smooth muscle contraction via muscarinic M3 receptors. Sympathetic input is more indirect, mediated through circulating catecholamines such as adrenaline, which activate β2-adrenergic receptors and promote bronchodilation. Sensory nerves, especially those arising from the vagal ganglia, detect irritants and inflammatory mediators, releasing neuropeptides like substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), and neurokinin A.

These neural pathways are not passive bystanders but active participants in asthma pathogenesis. For example, eosinophil-derived major basic protein can damage M2 muscarinic receptors on parasympathetic nerves, impairing their inhibitory function. The result is exaggerated acetylcholine release and heightened bronchoconstriction [17]. Similarly, mast cells, strategically located near nerve endings, can be activated by neuropeptides and, in turn, release histamine, tryptase, and leukotrienes that further stimulate nerves, creating a vicious cycle of neurogenic inflammation [18].

Recent attention has focused on PNECs, a rare but influential population of epithelial cells. PNECs function as airway sensors and secrete bioactive amines, peptides, and growth factors. Experimental work in mice demonstrated that PNEC deficiency reduces allergen-induced eosinophilia, goblet cell hyperplasia, and type-2 cytokine responses, implicating these cells as amplifiers of asthma [19]. Trpv1+ neurons, the ablation of which led to reduced airway hyperreactivity in allergen-challenged mice [20], expressed multiple receptors for PNEC-secreted ligands. Moreover, Trpv1+ neurons have been shown to contact the basal side of individual PNECs [21]. Thus, PNECs may interact with Trpv1+ neurons, and PNEC hyperplasia might exacerbate airway hyperreactivity in asthma. Their strategic location at the epithelial interface positions them as key integrators of environmental stimuli and immune activation.

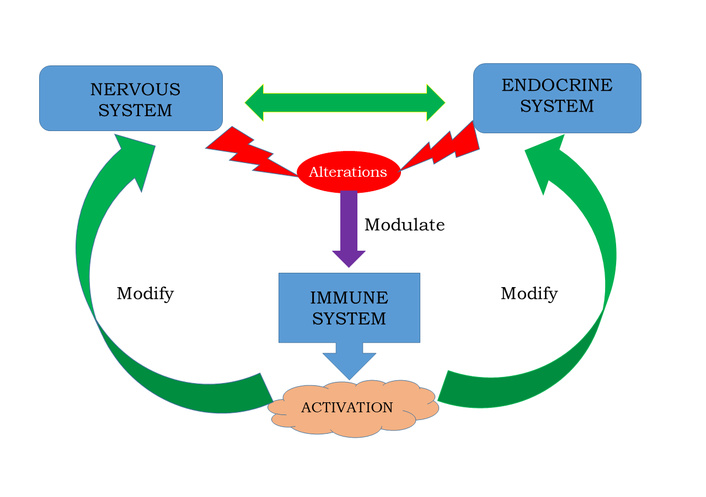

Psychoneuroimmunoendocrinology is the field that examines the complex interactions among psychological processes, neural activity, endocrine signaling, and immune responses. Bidirectional communication occurs when alterations in neural and endocrine function can modulate immune activity, while immune activation can, in turn, reshape endocrine regulation and central nervous system function (see Figure 3).

Nervous, endocrine, and immune systems interactions. Bidirectional interactions between nervous, endocrine, and immune systems integrate a complex structure with multidirectional functions and interfaces that allow for responding to internal and external threats. Such response is mediated by cytokines, hormones, and neurotransmitters, involved in different physiologic mechanisms of the organism’s homeostasis.

The immune system of the asthmatic airway is dominated by type-2 inflammation, with Th2 cells, type-2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), eosinophils, and mast cells as central actors. Yet these cells operate in constant communication with neural structures.

Eosinophils, beyond releasing cytotoxic granule proteins and cytokines, directly interact with nerves. Adhesion molecules such as vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) mediate eosinophil attachment to airway neurons, while their extracellular traps and mediators alter neuronal excitability. This process not only enhances parasympathetic reflexes but also contributes to long-term remodeling of the airway nerve network [22].

Asthma and COPD are pathologies with complex conditions and a wide range of phenotypes, which in many cases present as diseases refractory to treatments. It is necessary to identify biomarkers for monitoring these conditions. Therefore, although there is still a greater number of studies to be done, blood eosinophils are described as biomarkers [23, 24].

Mast cells also serve as intermediaries between nerves and immunity. They can be triggered by acetylcholine, neuropeptides, and even direct electrical signals from nerves. Once activated, mast cells secrete serotonin, which feeds back to sensory neurons, stimulating further acetylcholine release. Early in development, mast cell-derived neurotrophin-4 influences airway innervation, producing changes that persist into adulthood [25]. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) from mast cells further modifies β2-adrenergic receptor function on ASM, contributing to reduced responsiveness to bronchodilators.

ILC2s, increasingly recognized as pivotal drivers of asthma, are also modulated by neural inputs. Neuropeptides such as neuromedin U (NMU) and CGRP can directly activate or inhibit ILC2s, shaping the cytokine milieu in the lung [26]. These findings blur the boundaries between immune and neural regulation and suggest that ILC2s are not solely immune cells but participants in a neuro-immune circuit.

The endocrine system exerts broad control over inflammation and airway physiology through hormonal mediators. Chief among these is the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates glucocorticoid release. Cortisol, in physiologic concentrations, exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines, stabilizing mast cells, and promoting regulatory T cell function. In asthma, however, the HPA axis may be dysregulated. Chronic stress, circadian disruption, and repeated exacerbations can blunt cortisol responses, leaving the airway vulnerable to unchecked inflammation [27].

Paradoxically, the therapeutic use of inhaled corticosteroids, while lifesaving for many patients, introduces the risk of adrenal suppression when doses are high or prolonged. This iatrogenic endocrine complication underscores the delicate balance between leveraging and disturbing the body’s hormonal regulation [28].

Sex hormones add another dimension. Epidemiological data show that asthma prevalence is higher in boys before puberty, shifts toward higher rates in women during reproductive years, and fluctuates with menstrual cycles and pregnancy. Estrogen and progesterone appear to enhance type-2 immune responses by promoting ILC2 activation and inflammasome signaling, whereas androgens exert inhibitory effects on airway inflammation [29]. This hormonal influence provides a plausible explanation for sex-specific phenotypes and offers a potential avenue for targeted therapy.

Obesity is increasingly recognized as a systemic condition that amplifies asthma pathophysiology through intertwined metabolic, endocrine, and inflammatory pathways. Adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat, is not inert but an active endocrine organ that secretes adipokines such as leptin, resistin, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α), while reducing protective adiponectin levels. This profile promotes a state of low-grade systemic inflammation that interacts with airway immune responses, contributing to asthma severity and treatment resistance [30–33].

Beyond cytokine imbalance, obesity induces oxidative stress. Adipocyte hypertrophy and local hypoxia increase mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress, elevating the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Lipid peroxidation products, such as F2-isoprostanes, act as both biomarkers and mediators of inflammation, amplifying airway hyperresponsiveness and diminishing the protective effects of corticosteroids [34]. This oxidative-inflammatory milieu aggravates bronchial remodeling and lowers responsiveness to conventional anti-inflammatory therapies.

Mechanistically, the “obese-asthma” phenotype is characterized by adipokine dysregulation where leptin promotes Th1/Th17 polarization, while low adiponectin reduces anti-inflammatory buffering; oxidative stress amplification where ROS and isoprostanes impair airway epithelial integrity and worsen bronchial hyperreactivity; altered endocrine signaling characterized by modified HPA axis responsiveness and sex hormone effects by obesity, compounding airway inflammation, and mechanical and comorbid factors such as reduced lung compliance, obstructive sleep apnea, and insulin resistance that additively impair respiratory function.

Research in experimental animals fed obesogenic diets over prolonged periods has shown that these models not only exhibit increased body mass index (BMI) but also increased oxidative stress in the lungs and a state of low-grade systemic inflammation. When combined with a disease such as asthma, these factors create a much more complex pathophysiological scenario. Clinically, obesity is associated with poorer asthma control, more frequent exacerbations, and reduced responsiveness to inhaled corticosteroids [35, 36]. Weight reduction strategies, whether behavioral or surgical, have demonstrated significant improvements in lung function, quality of life, and exacerbation rates, highlighting obesity as a modifiable determinant of asthma outcomes [30–33]. Future therapeutic approaches may also consider targeting adipokine signaling, oxidative stress pathways, and metabolic inflammation as adjunctive strategies for this complex phenotype.

Among the most fascinating findings in the neuro-immuno-endocrinology of asthma are the roles of neurotrophins and neuropeptides. Neurotrophins such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are traditionally studied in the context of neural survival and plasticity, yet in asthma, they are increasingly recognized as mediators of inflammation and remodeling. Elevated levels of NGF and BDNF have been detected in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and serum of patients with asthma, correlating with both eosinophil counts and disease severity [37]. These factors extend the survival of eosinophils and mast cells, stimulate the proliferation of ASM, and promote the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins, thereby contributing directly to airway remodeling.

Neuropeptides released by sensory nerves, including substance P, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), CGRP, and NMU, modulate immune function and vascular tone. Substance P increases vascular permeability and mucus secretion while promoting mast cell degranulation. VIP, in contrast, has complex effects: although it can act as a bronchodilator, in certain contexts it stimulates type-2 inflammation. CGRP, abundantly released by C-fibers in the lung, has been shown to influence the activity of ILC2s, serving as both a pro- and anti-inflammatory signal depending on timing and local context [26]. These mediators illustrate the nuanced and sometimes paradoxical nature of neuro-immune crosstalk in the asthmatic airway.

Airway remodeling, a hallmark of chronic asthma, reflects the cumulative effects of this neuro-immune dialogue. Smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia, thickening of the basement membrane, goblet cell hyperplasia, and increased airway innervation are consistently observed in long-standing disease. NGF and TGF-β, together with serotonin, substance P, and neurotrophin-4 (NT4), orchestrate these changes. The remodeling process not only worsens airflow limitation but also reduces the reversibility of bronchoconstriction, explaining why patients with severe asthma often respond poorly to bronchodilators and corticosteroids [25].

Asthma management is primarily aimed at reducing airway inflammation and preventing obstruction through medications that control symptoms and improve long-term outcomes (Global Initiative for Asthma [GINA], 2021) [38]. According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NHLBI/NAEPP, 2020) [39], the central objective is achieving and maintaining asthma control, defined as the extent to which symptoms and disease-related risks are effectively minimized in the individual.

The airways are a crucial location in the pathophysiology of numerous inflammatory respiratory disorders. It is well-documented that patients may concurrently exhibit two or more distinct nosologically entities. Consequently, the implementation of an integrated diagnostic framework that accounts for the coexistence of multiple airway diseases is imperative for optimizing diagnostic accuracy. These complex interrelationships exert a significant impact not only on disease prevalence but also on clinical management strategies and patients’ prognosis, manifesting as a bidirectional phenomenon commonly referred to as overlapping syndromes [1].

First-line therapies include inhaled corticosteroids, often combined with long-acting bronchodilators, and leukotriene receptor antagonists, which have proven efficacy in controlling airway inflammation and preventing exacerbations.

Given that psychological factors contribute significantly to asthma morbidity, interventions that address stress and affective reactivity have become increasingly relevant. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation training, and mindfulness-based techniques have been tested in clinical trials and generally demonstrate positive effects on health-related quality of life, psychosocial outcomes, and, in some cases, lung function [40, 41]. These approaches highlight the importance of integrating psychosocial care into routine asthma management.

Mindfulness techniques, which cultivate non-judgmental awareness and acceptance of bodily sensations and thoughts, have received growing attention. In a 12-month randomized controlled trial, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) produced lasting improvements in asthma-related quality of life and stress reduction, even in the absence of significant changes in lung function [42]. More recent evidence supports these findings: an 8-week MBSR intervention in adults with persistent asthma resulted in significantly improved asthma control, increased self-reported mindfulness, and reduced psychological distress compared with wait-list controls [43].

Digital adaptations have also been explored. A randomized feasibility trial of an online mindfulness program for primary care patients demonstrated improvements in asthma-related quality of life in the intervention group compared to baseline, though between-group differences were not statistically significant [44]. Nonetheless, more participants in the intervention group achieved clinically meaningful improvements, and favorable trends in anxiety and depression outcomes were observed.

Specific mindfulness skills may also influence asthma outcomes. For instance, the ability to accurately describe internal experiences was associated with better asthma-related quality of life, although not with asthma control itself [44]. These findings suggest that mindfulness may exert its main benefits by altering patients’ appraisal and coping with symptoms, rather than by directly improving physiological measures.

Taken together, the evidence positions mindfulness as a promising adjunctive treatment in asthma. While its effects on physiological symptoms remain inconsistent, mindfulness reliably improves psychological resilience, reduces distress, and enhances quality of life in patients with chronic asthma. As such, incorporating psychological interventions alongside pharmacological treatments represents a comprehensive strategy for addressing both the biological and psychosocial dimensions of asthma.

Asthma, long conceptualized as a disease of airway inflammation and reversible obstruction, is now recognized as a heterogeneous and systemic disorder. Advances in immunology, pulmonary physiology, neurobiology, endocrinology, and systems medicine reveal that its pathophysiology extends far beyond the conducting airways. Structural remodeling, epithelial barrier dysfunction, alveolar involvement, and impaired MCC illustrate how persistent injury shapes chronic disease progression. At the same time, neuro-immune-endocrine interactions highlight the airway as a dynamic interface where environmental, metabolic, and psychological factors converge.

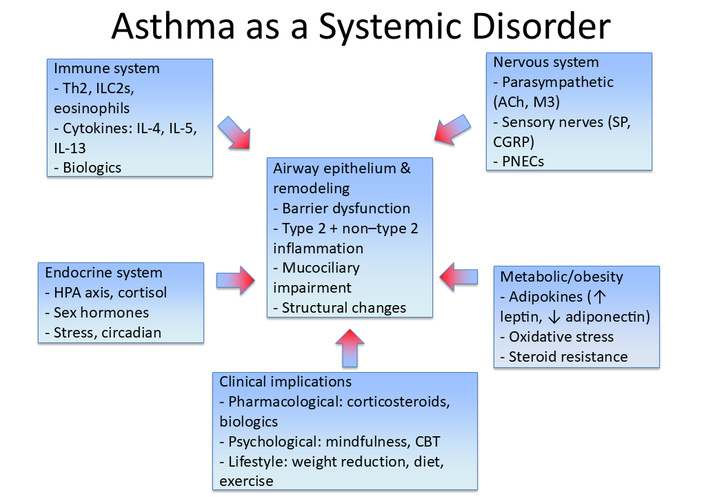

Systemic comorbidities such as obesity and metabolic inflammation further complicate disease expression, contributing to treatment resistance and poorer outcomes. Likewise, hormonal influences and stress responses underscore the importance of endocrine regulation and psychosocial resilience in asthma control. Recognition of these multidimensional drivers has spurred new therapeutic avenues, from biologics targeting epithelial cytokines to integrative interventions such as mindfulness that address the psychological burden of chronic illness (see Figure 4).

Asthma as a systemic disorder. Asthma involves complex interactions across multiple biological systems beyond the airways. The central role of airway epithelium and remodeling (barrier dysfunction, type-2 and non-type-2 inflammation, mucociliary impairment, and structural changes) is modulated by immune mechanisms (Th2 cells, ILC2s, eosinophils, cytokines), neural regulation (parasympathetic and sensory nerves, PNECs), endocrine influences (HPA axis, cortisol, sex hormones, circadian factors), and metabolic/obesity-related pathways (adipokines, oxidative stress, steroid resistance). These interconnected processes shape clinical implications, highlighting the need for integrative therapeutic strategies that combine pharmacological, psychological, and lifestyle-based interventions. CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; CGRP: calcitonin gene-related peptide; HPA: hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; ILC2s: type-2 innate lymphoid cells; PNECs: pulmonary neuroendocrine cells; SP: substance P; Th2: T helper 2 cells.

By reframing asthma as a systemic condition, a more comprehensive and personalized approach to management becomes possible. One that integrates pharmacological therapies with behavioral and lifestyle strategies, while accounting for the patient’s broader physiological and psychosocial context. Such a paradigm shift not only deepens our understanding of asthma’s complexity but also paves the way for improved long-term outcomes, enhanced quality of life, and reduced societal burden.

ASM: airway smooth muscle

BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor

CGRP: calcitonin gene-related peptide

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

HPA: hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

IL: interleukin

ILC2s: type-2 innate lymphoid cells

MBSR: Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

MCC: mucociliary clearance

NGF: nerve growth factor

NMU: neuromedin U

PNECs: pulmonary neuroendocrine cells

ROS: reactive oxygen species

TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β

Th2: T helper 2 cells

TSLP: thymic stromal lymphopoietin

VIP: vasoactive intestinal peptide

SMA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. MEC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. VSB: Investigation, Writing—original draft. NNG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 2109

Download: 43

Times Cited: 0

Amar P. Garg ... Bajeerao Patil

Graziella Chiara Prezzavento

Jim E. Banta ... James M. Banta

Nassiba Bahra ... Samira El Fakir

Alberto Vidal, Marcela Matamala