Affiliation:

Department of Biology, QuantX Biosciences Inc., Princeton, NJ 08540, United States

Email: joy.zhou@quantxbio.com

Explor Immunol. 2025;5:1003232 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2025.1003232

Received: August 20, 2025 Accepted: November 05, 2025 Published: December 23, 2025

Academic Editor: Sofia Kossida, The International ImMunoGeneTics Information System, France

The article belongs to the special issue Advances in Cellular and Molecular Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), consisting of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract with significant clinical impact, leading to debilitating symptoms, impaired quality of life, and an increased risk of complications such as colorectal cancer. This review provides a comprehensive overview of current and emerging therapeutic strategies for IBD. We conducted a narrative review to explore therapeutic advances in IBD treatment, focusing on mechanisms of action, clinical development, and current therapeutic challenges. We analyzed existing knowledge on clinical drug development for IBD, up to July 2025. Our search encompassed databases including PubMed, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Google Scholar, using keywords such as “Inflammatory bowel disease”, “Crohn’s disease”, “Ulcerative colitis”, “therapeutics”, and relevant drug names. We delve into key progress in approved drugs in recent years, including biologic and targeted small molecule therapies, which have advanced the treatment paradigms by offering more precise targeting of inflammatory pathways. This review also covers investigational drugs in clinical development, including biologics and small molecules against novel molecular targets, cell and gene therapies, precision medicine approaches, and microbiome-based interventions. Those novel therapies could potentially address unmet medical needs by achieving deeper and more durable responses, inducing remission, preventing disease progression, and ultimately improving long-term patient outcomes. This review summarizes the latest progress in IBD treatment, outlines the advantages, pitfalls, and research prospects of various drugs and therapies, aiming to provide a foundational understanding for both clinical decision-making and future IBD research.

First described in the Western population in 1859 [1, 2], inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) represents a class of chronic, relapsing-remitting inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract that include two major types: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [3, 4]. IBD now reflects a significant and growing global burden. In 2023, the global prevalence of UC alone was estimated at 5 million cases [5]. In the US, age- and sex-standardized data revealed a higher prevalence of UC compared to CD, with 378 vs. 305 cases per 100,000 population, respectively [6]. Since 1990, the number of IBD prevalent cases has risen by 47%. This upward trend is especially notable in newly industrialized countries, where westernization and lifestyle shifts are contributing factors to the increasing prevalence of IBD [7].

The therapeutic landscape for IBD has undergone a remarkable expansion in recent years. Conventional treatments—including aminosalicylates, corticosteroids (CSs), immunomodulators, and biologics, along with general measures or surgical resection, have long aimed to control symptoms [8]. A major development arrived in 1998 with the approval of infliximab, the first anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) biologic for CD. This innovation started a new era, shifting the therapeutic framework from mere symptomatic clinical remission toward the more ambitious goal of sustained deep remission. Treatment strategies evolved in parallel, now prioritizing the early introduction of effective therapy, combined with tight and frequent control of inflammatory activity, and adjustments based on those assessments—a true treat-to-target strategy [9, 10].

In response, a wave of new therapeutic strategies is emerging, encompassing small molecules, apheresis therapy, approaches to improve intestinal microecology, cell therapy, and even exosome therapy [8]. Beyond medication, patient education on diet and psychology has also proven beneficial for IBD management. This recent progress, particularly the emergence of biologics, has not only reshaped IBD treatment modalities but also expanded the overall perspective of IBD therapy. Today, treatment decisions for IBD are multifaceted, considering not only disease activity and severity but also patient risk tolerance, co-existing conditions, the potential for treatment-related complications, and payer considerations. Ultimately, the objective of treatment is to control symptoms and mitigate inflammation to avert disease progression and complications [11, 12].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the therapeutic landscape in IBD by delving into the mechanisms of action (MoAs), efficacy, and safety profiles of established drug classes, highlighting their key milestones in development. We will also discuss novel therapeutic targets and approaches currently under investigation, aiming to address the unmet medical needs in IBD therapeutics.

In this review, a narrative search was performed on PubMed, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Google Scholar. The search utilized individual and combined terms such as “Inflammatory bowel disease”, “Crohn’s disease”, and “Ulcerative colitis”, along with “therapeutics”, “pathogenesis”, and specific drug names. Publications between January 2001 and July 2025 were considered, with no language restrictions. Our selection prioritized the most recent and relevant articles for IBD therapeutics. For approved targeted drugs, we focused on landmark Phase 3 clinical trials that led to their regulatory approval, while for drugs in the pipeline, we included those in Phase 2 or higher. For novel therapies, our focus was on preclinical evidence and Phase 1 clinical trials. Relevant older or broader publications on immune pathogenesis were also included if applicable to IBD therapeutics.

IBD is characterized by a variety of diverse clinical manifestations, commonly including GI pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, weight loss, exhaustion, and fever. Since these symptoms are often not exclusive to IBD, a comprehensive diagnosis involving colonoscopy, computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and blood/stool tests is crucial [4, 10, 13]. CD can affect any part of the GI tract, most often the terminal ileum and colon. The hallmark of CD is transmural inflammation, frequently leading to complications like strictures, fistulas, and abscesses, along with extra-intestinal symptoms such as joint pain, skin rashes, and eye irritation. UC primarily affects the colon and rectum, with inflammation typically starting in the rectum and extending continuously [13, 14]. A typical distinguishing feature of UC is that its inflammation is confined to the mucosal layer. Patients commonly experience bloody diarrhea, urgency, tenesmus, and stomach cramps [15–17].

The pathogenesis of IBD is an interplay of genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, a dysregulated immune response, and dysbiosis of the gut microbiota.

Genetics: Genetic factors play a critical role in IBD susceptibility, especially for CD [18, 19]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified approximately 240 genetic variants associated with IBD risk [20–22]. Key gene variants such as nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2), autophagy related 16 like 1 (ATG16L1), and interleukin (IL)-23 receptor (IL-23R) contribute to the dysregulated immune response and impaired mucosal barrier function of IBD [21, 23, 24]. These variations include polymorphisms in genes encoding regulatory receptors at the intestinal epithelial barrier, pro-inflammatory cytokines or their receptors, and cell death pathway proteins. The impact of each risk locus can vary with patient ethnicity. It was reported that these established risk loci account for only an estimated 13.6% of disease variance in CD and 7.5% in UC. This suggests that other factors beyond genetics, such as environmental influences, the gut microbiome, and immune responses, likely also play crucial roles in IBD [20, 25–28].

Environmental factors: Environmental factors are increasingly recognized for their crucial role in its rising global prevalence by influencing the gut microbiome, immune system, and intestinal barrier [28]. Diet significantly impacts IBD: while anti-inflammatory foods may help reduce flare-ups, diets heavy in sugar, unhealthy trans-fats, and low fiber are recognized risk factors [29]. Additionally, the industrialization of food and the inclusion of microparticles such as titanium dioxide are concerns, as they might compromise the intestinal barrier and immune system [30, 31]. Vitamin D deficiency is linked to a higher risk of CD, and supplementation can reduce relapses, possibly explaining the geographical variation in IBD [32, 33]. Appendectomy offers protection against UC but may increase CD risk [34, 35]. Smoking is a strong risk factor for CD, worsening its course and complications, while it paradoxically appears protective against UC [36, 37]. Furthermore, physical activity shows a protective effect against CD, but not UC, and a higher body mass index (BMI) at diagnosis is associated with a later onset and less severe IBD [38–40]. Beyond these, stress, childhood infections, and the consumption of regular coffee or well/spring water have also been identified as influencing IBD risk [41].

Gut microbiota dysbiosis: The gut microbiota plays a critical role in the development and progression of IBD [32, 42, 43]. Dysbiosis is an imbalance in this microbial ecosystem, which is characterized by reduced diversity, a loss of beneficial bacteria, or an overgrowth of harmful microbes, and contributes to chronic inflammation and a compromised intestinal barrier. For example, patients with CD can exhibit an increase in Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria and a decrease in Firmicutes and overall bacterial diversity [44, 45]. Conversely, a reduction in protective microorganisms like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Bacteroides fragilis, both known for anti-inflammatory properties, is also observed in IBD [46, 47]. While it’s debated whether dysbiosis is a cause or a consequence of inflammation, evidence suggests both. Host genetics, environmental factors (such as infections, antibiotics, or diet), and inflammation itself can all induce dysbiosis [48–50]. However, microbial alterations alone may not be sufficient to cause IBD, often requiring a combination with environmental or immune abnormalities. Overall, gut dysbiosis in IBD signifies a disrupted equilibrium between the microbiota and its host, contributing to a dysfunctional mucosal immune response and prolonged inflammation [51, 52].

Intestinal barrier impairment: The intestinal barrier is a critical boundary separating the mucosal immune system from luminal contents like microorganisms, pathogens, and toxins. It consists of a physical barrier (intestinal epithelial cells and specialized junctions) and a chemical barrier (mucins, antimicrobial peptides, secretory IgA) [51, 53–55]. Damage to these components leads to a “leaky gut”, initiating immune activation central to IBD pathogenesis and promoting both local and systemic inflammation [53–55]. In IBD, this barrier is compromised across all intestinal cell types, including goblet and Paneth cells, leading to reduced production of important mediators such as WAP four-disulfide core domain protein 2 (WFDC2) and defensins, which exacerbates dysbiosis. Inflammatory processes also impair leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5)-expressing stem cells, hindering epithelial regeneration, while single-cell analyses reveal new epithelial subtypes like LCN2, NOS2 and DUOX2-expressing (LND) cells that indicate profound cellular changes [56–59]. Ultimately, chronic IBD inflammation is largely driven by this compromised barrier or thinned mucin layer, originating from genetic and environmental factors. This breach increases intestinal permeability, allowing microbial antigens to perpetuate the aberrant immune response, making restoring intestinal barrier integrity a critical therapeutic target for IBD management [60, 61].

Immune dysregulation: While a healthy gut maintains immune homeostasis through mediators such as IL-10, transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), IBD represents a profound deviation of these innate and adaptive signaling pathways to preserve tolerance. This breakdown begins with an impaired intestinal mucosal barrier, allowing microbial pathogens to invade and trigger a strong pro-inflammatory immune response [55, 60, 61]. Innate immune cells, particularly hyperactivated mucosal macrophages, engulf microbes and release a cascade of pro-inflammatory cytokines [e.g., TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, IL-23, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2)] [60–62]. This cytokine environment promotes the differentiation and expansion of T helper 1 (Th1), Th2, and Th17 cells, overwhelming Tregs and perpetuating local inflammation [55, 60, 61, 63–66]. Effector T cell subsets and group 1 and 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) further amplify this inflammatory feedback loop by secreting cytokines like IL-17, IL-22, and interferon (IFN)-γ, while anti-inflammatory mechanisms are profoundly diminished. This sustained activation leads to epithelial damage, impaired barrier function, dysbiosis, and the perpetuation of gut inflammation, with primed circulating lymphocytes also contributing to extra-intestinal manifestations [67, 68].

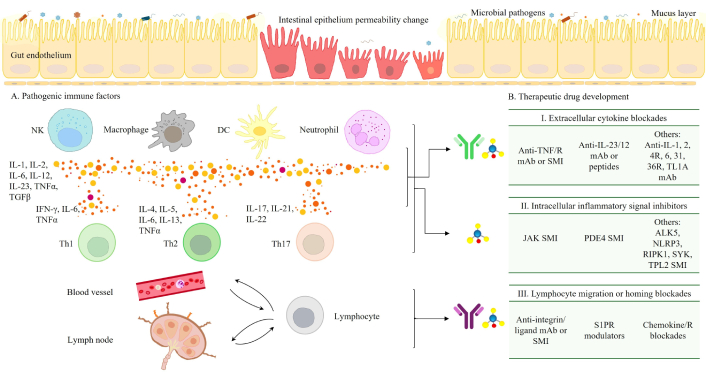

Key therapeutic targets in IBD directly reflect the underlying pathogenic mechanisms. The clinically validated targets can be broadly categorized as: (I) Extracellular inflammatory cytokines: This category features TNFα, a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine critically involved in driving tissue destruction, and the IL-12/IL-23 cytokines, which are pivotal in mediating the differentiation of Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes and their subsequent pro-inflammatory effects. Additionally, cytokines such as TNF-like ligand 1A (TL1A), IL-6, IL-36, and IL-1 further amplify inflammation by activating specific signaling pathways that exacerbate immune cell activation, cytokine production, and the acute phase response [69–75]. (II) Intracellular signaling molecules: Exemplified by the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway, which acts as a crucial transducer of signals initiated by a multitude of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Other critical intracellular elements in intestinal immune cell signaling are also included, such as tumor progression locus 2 (TPL2), spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), and so on [69–72, 76–79]. (III) Lymphocyte trafficking molecules: This group encompasses integrins, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1PR), various adhesion molecules and chemokines, all of which are essential mediators of leukocyte transmigration and retention within inflamed intestinal tissues [80–83]. As visually represented in Figure 1, the strategic targeting of these distinct cellular and cytokine interactions forms the foundation for disrupting the chronic inflammatory cycle in IBD.

Intestinal immune pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets in IBD. The pathogenesis of IBD involves a complex interaction of multiple factors. Gut microbiota dysbiosis largely contributes to chronic inflammation and compromised intestinal barrier. This dysbiosis is often associated with impaired intestinal barrier function, where the gut lining becomes “leaky”, allowing luminal contents to trigger immune responses. This leads to immune dysregulation (A), marked by an overactive innate and adaptive immune system with increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production (e.g., TNFα, IL-12/23) and overactivated immune cells [macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells (DCs), T cells, etc.]. Therapeutic drug development (B) for IBD involves the use of monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and small molecule inhibitors (SMI) and modulators to target these pathological processes and restore immune homeostasis. These agents focus on three primary pathological areas: I) extracellular inflammatory cytokines; II) intracellular signaling molecules, such as JAK-STAT pathways; and III) lymphocyte trafficking molecules, including integrins and S1PR. IL: interleukin; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; TGFβ: transforming growth factor β; IFN: interferon; Th1: T helper 1; IL-4R: IL-4 receptor; TL1A: TNF-like ligand 1A; JAK: Janus kinase; PDE4: phosphodiesterase 4; ALK5: activin receptor-like kinase 5; NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; RIPK1: receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1; SYK: spleen tyrosine kinase; TPL2: tumor progression locus 2; S1PR: sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; STAT: signal transducer and activator of transcription.

Effective therapies for IBD were absent until the 1930s. The first pharmacological attempt to control IBD emerged with Nanna Svartz’s development of sulfasalazine. From that point forward, through the 1990s, the introduction of glucocorticoids and immunomodulators forms the foundation of IBD management, particularly for inducing remission in mild to moderate disease. These agents now constitute what is termed “conventional therapy” in IBD management [84, 85].

Aminosalicylates: Medications like mesalamine are primarily recommended for UC, particularly for mild to moderate manifestations. While their exact mechanism is not fully elucidated, they possess anti-inflammatory actions. High doses are often more effective, especially in extensive UC, and oral single daily doses can improve adherence. Despite being considered a first-line treatment for mild to moderate UC, 5-aminosalicylic acids (5-ASAs) have not definitively shown efficacy in inducing or maintaining remission in CD [86–88].

CSs: CSs, such as prednisone and methylprednisolone, have long been a cornerstone for rapidly inducing remission during acute IBD flares due to their potent anti-inflammatory effects. However, their utility is significantly limited by a wide array of systemic side effects, including obesity, hypertension, glaucoma, adrenal insufficiency, increased risk of diabetes, cataracts, skin thinning, GI ulcers, osteopenia, and increased susceptibility to infections. These considerable risks, coupled with the potential for steroid dependency or resistance, render them unsuitable for long-term maintenance therapy [89, 90]. While newer, second-generation glucocorticoids like budesonide and beclomethasone dipropionate aim to mitigate systemic side effects by targeting the GI tract, the overall challenges associated with CSs highlight the pressing need for novel and sustainable long-term treatment strategies for IBD [90, 91].

Immunomodulators: Immunomodulators, including thiopurines (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine) and methotrexate (MTX), are vital for maintaining remission in moderate IBD, and are often used with CSs or other therapies [92, 93]. Thiopurines inhibit DNA/RNA synthesis and promote T cell apoptosis, effectively sustaining steroid-free remission, preventing postoperative CD recurrence, and potentially enhancing biologic efficacy by reducing anti-drug antibody (ADAb) formation. Before starting thiopurines, it’s crucial to assess thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) activity due to genetic variations affecting metabolism and myelosuppression risk. MTX is a viable option for steroid-dependent patients, effective in maintaining CD remission, and may also reduce ADAb formation. Despite their benefits, these agents have a slow onset and carry risks such as hepatotoxicity and myelosuppression. Thiopurines also increase lymphoma risk, and MTX is contraindicated in pregnancy due to teratogenic effects [92–95].

Antibiotics: Agents such as fluoroquinolone and metronidazole are generally reserved for septic complications like perianal fistulas and abscesses, often used short-term and sometimes as adjuvant therapy with anti-TNF drugs to reduce drainage and improve symptoms [96, 97]. While limited evidence suggests a modest benefit in certain active CD cases, these antibiotics are not considered primary therapy for inducing or maintaining remission in luminal CD due to their restricted efficacy and significant risk of side effects with prolonged use. Long-term or widespread antibiotic use in IBD is discouraged owing to concerns about fostering antibiotic resistance, potential adverse effects (AEs; e.g., GI issues, neuropathy, tendon complications), and disrupting the gut microbiome, which is increasingly recognized as crucial in IBD pathogenesis [97, 98].

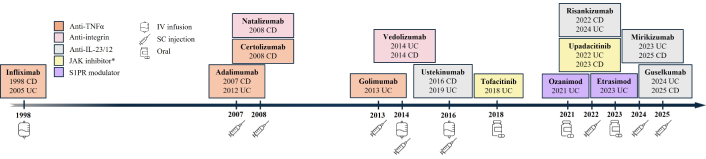

The contemporary pharmacological management of IBD has undergone a profound evolution, transitioning from broad symptomatic control to highly targeted interventions. These advanced therapies (ATs) precisely modulate the multi-step pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammation by inhibiting crucial processes such as recruitment, differentiation, proliferation, and activation of inflammatory immune cells in the gut mucosa [84]. An overview timeline of FDA-approved targeted IBD therapeutics is presented in Figure 2. Their landmark Phase 3 clinical trials for UC and CD are summarized in Table 1.

FDA-approved targeted drugs for IBD. FDA-approved targeted drugs for IBD are generally categorized into large molecules [biologics, e.g., anti-TNFα, anti-integrins, anti-interleukins (ILs)], administered via intravenous (IV) or subcutaneous (SC) injection during induction and maintenance phases, and small molecules (e.g., JAK inhibitors, S1PR modulators), administered orally. *: JAK inhibitor, filgotinib, was approved for UC in EU, UK, and Japan. TNF: tumor necrosis factor; JAK: Janus kinase; S1PR: sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor; CD: Crohn’s disease; UC: ulcerative colitis; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

Selected landmark clinical trials of FDA-approved targeted drugs for IBD.

| Class | Agent | Indication | Study | Patients | Treatment | Primary outcome&,# | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-TNFα | Infliximab | CD | ACCENT I | 573 | IFX vs. placebo |

| [99] |

| CD fistulizing | ACCENT II | 306 | IFX vs. placebo |

| [100] | ||

| UC | ACT 1 | 364 | IFX vs. placebo |

| [101] | ||

| UC | ACT 2 | 364 | IFX vs. placebo |

| [101] | ||

| Adalimumab | CD | CLASSIC I | 299 | ADA vs. placebo |

| [102] | |

| CD | CLASSIC II | 276 | ADA vs. placebo |

| [103] | ||

| CD | CHARM | 854 | ADA vs. placebo |

| [104] | ||

| CD | GAIN | 325 | ADA vs. placebo |

| [105] | ||

| CD | EXTEND | 135 | ADA vs. placebo |

| [106] | ||

| CD | ADAFI | 76 | ADA vs. ADA + ciprofloxacin |

| [107] | ||

| UC | ULTRA 1 | 576 | ADA vs. placebo |

| [108] | ||

| UC | ULTRA 2 | 494 | ADA vs. placebo |

| [109] | ||

| Certolizumab pegol | CD | PRECISE 1 | 662 | CZP vs. placebo |

| [110] | |

| CD | PRECISE 2 | 668 | CZP vs. placebo |

| [111] | ||

| Golimumab | UC | PURSUIT-SC induction | 1,064 | GLM vs. placebo |

| [112] | |

| UC | PURSUIT-Maintenance | 464 | GLM vs. placebo |

| [113] | ||

| Anti-integrin | Natalizumab | CD | ENACT-1 | 905 | NTZ vs. placebo |

| [114] |

| CD | ENACT-2 | 339 | NTZ vs. placebo |

| [114] | ||

| CD | ENCORE | 509 | NTZ vs. placebo |

| [115] | ||

| Vedolizumab | UC | GEMINI 1 | 895 | VDZ vs. placebo |

| [116] | |

| CD | GEMINI 2 | 1,115 | VDZ vs. placebo |

| [117] | ||

| CD | GEMINI 3 | 315 | VDZ vs. placebo |

| [118] | ||

| CD | VISIBLE 2 | 410 | VDZ vs. placebo |

| [119] | ||

| UC | VARSITY | 769 | VDZ vs. ADA |

| [120] | ||

| UC | VISIBLE 1 | 216 | VDZ vs. placebo |

| [121] | ||

| Anti-IL-12/23 (p40) | Ustekinumab | CD | UNITI-1 | 741 | UST vs. placebo |

(intolerance or inadequate response to TNF blockade) | [122] |

| CD | UNITI-2 | 628 | UST vs. placebo |

(intolerance or inadequate response to conventional therapy) | [122] | ||

| CD | IM-UNITI | 397 | UST vs. placebo |

| [123] | ||

| UC | UNIFI | 961 | UST vs. placebo |

| [124] | ||

| Anti-IL-23 (p19) | Risankizumab | CD | ADVANCE | 931 | RZB vs. placebo |

(intolerance or inadequate response to approved biologics or conventional therapy) | [125] |

| CD | MOTIVATE | 618 | RZB vs. placebo |

(intolerance or inadequate response to approved biologics) | [125] | ||

| CD | FORTIFY | 542 | RZB vs. placebo |

| [126] | ||

| UC | INSPIRE | 975 | RZB vs. placebo |

| [127] | ||

| UC | COMMAND | 548 | RZB vs. placebo |

| [127] | ||

| CD | SEQUENCE | 527 | RZB vs. UST |

| [128] | ||

| Mirikizumab | CD | CD-1 | 679 | MIRI vs. placebo |

| [129] | |

| UC | LUCENT-1 | 1,162 | MIRI vs. placebo |

| [130] | ||

| UC | LUCENT-2 | 1,073 | MIRI vs. placebo |

| [130] | ||

| Guselkumab | CD | GRAVITI | 340 | GUS vs. placebo |

| [131] | |

| CD | GALAXI-2 | 508 | GUS vs. placebo or UST |

| [132] | ||

| CD | GALAXI-3 | 513 | GUS vs. placebo or UST |

| [132] | ||

| UC | ASTRO | 418 | GUS vs. placebo |

| [133] | ||

| UC | QUASAR | 701 | GUS vs. placebo |

| [134] | ||

| JAKi | Tofacitinib | UC | OCTAVE Induction 1 | 598 | TOF vs. placebo |

(intolerance or inadequate response to conventional therapy) | [135] |

| UC | OCTAVE Induction 2 | 541 | TOF vs. placebo |

(intolerance or inadequate response to TNF blockade) | [135, 136] | ||

| Upadacitinib | CD | U-EXCEL | 526 | UPA vs. placebo |

| [137] | |

| CD | U-EXCEED | 495 | UPA vs. placebo |

| [137] | ||

| CD | U-ENDURE | 502 | UPA vs. placebo |

| [137, 138] | ||

| UC | U-ACHIEVE induction | 474 | UPA vs. placebo |

| [139] | ||

| UC | U-ACHIEVE maintenance | 451 | UPA vs. placebo |

| [139] | ||

| UC | U-ACCOMPLISH | 522 | UPA vs. placebo |

| [139] | ||

| S1PR modulator | Ozanimod | UC | J-TRUE NORTH | 198 | OZA vs. placebo |

| [140] |

| UC | TRUE NORTH | 1,012 | OZA vs. placebo |

| [141] | ||

| Etrasimod | UC | ELEVATE UC 12 | 354 | ETR vs. placebo |

| [142] | |

| UC | ELEVATE UC 52 | 433 | ETR vs. placebo |

| [142] |

&: Primary clinical outcomes observed at FDA-approved doses and administration, or as otherwise indicated; #: clinical remission defined as Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score < 150, or total score of ≤ 2 on the Mayo scale and no subscore > 1 on any of the four Mayo scale components; or as a stool frequency score < 1 and not higher than baseline, rectal bleeding score of 0, and endoscopic subscore < 1 without friability. Clinical response defined as a reduction from baseline in the complete Mayo score of ≥ 3 points and ≥ 30%, and a reduction from baseline in the rectal bleeding subscore (RBS) of ≥ 1 point or an absolute RBS of ≤ 1 point. Mucosal healing defined as an absolute subscore for endoscopy of 0 or 1. Endoscopic response defined as > 50% improvement from baseline in Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) score. Endoscopic remission defined as SES-CD ≤ 4 and a ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline and no subscore greater than 1 in any individual component. Endoscopic improvement defined as subscore of 0 to 1 on the Mayo endoscopic component; ∆: difference between the treatment group and the placebo group. IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; CD: Crohn’s disease; IFX: infliximab; UC: ulcerative colitis; ADA: adalimumab; CZP: certolizumab pegol; GLM: golimumab; NTZ: natalizumab; VDZ: vedolizumab; IL: interleukin; UST: ustekinumab; RZB: risankizumab; SC: subcutaneous; MIRI: mirikizumab; GUS: guselkumab; JAKi: Janus kinase inhibitor; TOF: tofacitinib; UPA: upadacitinib; S1PR: sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor; OZA: ozanimod; ETR: etrasimod.

The pharmacological landscape of IBD treatment is largely shaped by biologic therapies, including large molecules targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines and integrins [143–145]. Their efficacy and safety in managing IBD have been demonstrated or are currently assessed by extensive research, as summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Drug development pipeline for IBD: antibody therapies*.

| MoA | Drug name | Indication | RoA | Highest clinical stage | Clinical trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-TL1A | RO7790121 (afimkibart, PF-06480605, RVT-3101) | UC, CD | IV, SC | UC: two Ph3 recruitingCD: two Ph3 recruiting | NCT06588855; NCT06589986; NCT06819891; NCT06819878 |

| Anti-TL1A | Tulisokibart (MK-7240, PRA023) | UC, CD | IV, SC | UC: two Ph3 recruitingCD: two Ph3 recruiting | NCT06052059; NCT06430801; NCT06651281 (joint for UC and CD) |

| Anti-TL1A | Duvakitug (TEV-48574) | UC, CD | SC | UC, CD: Ph2 completed | NCT05499130; NCT05668013 (ongoing) |

| IL-1α/β | Lutikizumab (ABT-981) | UC, CD | IV, SC | UC: Ph2 ongoingCD: Ph2 recruiting | NCT06257875; NCT06548542 |

| Anti-α4β7 | Abrilumab (AMG 181, MEDI7183) | UC, CD | SC | UC: Ph2 completedCD: Ph2 completed | NCT01959165; NCT01694485; NCT01696396 |

| Anti-α4β7 | ABBV-382 | CD | IV, SC | Ph2 recruiting | NCT06548542 |

| Anti-OSMRβ | Vixarelimab (RG6536) | UC | SC | Ph2 terminatedPh1/2 recruiting | NCT06137183; NCT06693908 |

| MAdCAM-1 | Ontamalimab (PF-00547659) | UC, CD | SC | UC: Ph3 completed or terminatedCD: Ph3 completed or terminated | NCT03290781; NCT03283085; NCT03627091; NCT03566823; NCT03259308; NCT03259334 |

| Anti-CCR9 | AZD7798 | CD | SC, IV | Two Ph2 recruiting | NCT06681324; NCT06450197 |

| IL-36R | Spesolimab (BI655130) | UC, CD | IV | UC: Ph2/3 completedCD: Ph2 completed | NCT03482635; NCT03752970 |

| PSGL-1 agonist | ALTB-268 | UC | SC | Ph2 recruiting | NCT06109441 |

| Anti-IL-4Rα | Dupilumab | UC | SC | Ph2 recruiting | NCT05731128 |

| CXCR1/2 blockade | Eltrekibart (LY3041658) | UC | SC | Ph2 recruiting | NCT06598943 |

| IL-2 blockade | Aldesleukin | CD | SC | Ph1/2 recruiting | NCT04263831 |

| TNFRII-Fc | OPRX-106 | UC | PO | Ph2 unknown | NCT02768974 |

| gp130Fc (IL-6 trans) | Olamkicept (TJ301) | UC | IV | Ph2 completed | NCT03235752 |

*: The search on ClinicalTrials.gov was completed by July 1st, 2025. IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; MoA: mechanism of action; RoA: route of administration; TL1A: tumor necrosis factor-like ligand 1A; UC: ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; IV: intravenous; SC: subcutaneous; IL: interleukin; OSMR: oncostatin M receptor; MAdCAM-1: mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule-1; CCR9: C-C chemokine receptor 9; IL-36R: IL-36 receptor; PSGL-1: P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1; CXCR1/2: C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 1/2; TNFRII-Fc: tumor necrosis factor receptor II fused to the Fc region of IgG1; PO: oral administration.

TNFα, a key member of the TNF superfamily, plays important roles in inflammation, apoptosis, proliferation, and tissue invasion. The overexpression of TNFα can be associated with chronic inflammation and tissue damage. Initially synthesized as a transmembrane TNF (tmTNF) precursor, TNFα precursor can be cleaved by TNFα converting enzyme (TACE) to release a soluble form (sTNF) [146–148]. Both tmTNF and sTNF are biologically active, binding to two distinct receptors: TNF receptor (TNFR)1 and TNFR2 [149, 150]. It was reported that sTNFα primarily activates TNFR1, and tmTNFα can activate both. Research suggests that neutralizing tmTNFα might be more beneficial for IBD efficacy, and some hypothesize that selectively inhibiting TNFR1 in autoimmune diseases could reduce inflammation by retaining TNFR2 signaling. However, the specific advantages of targeting sTNF vs. tmTNF forms, and the individual roles of TNFR1 vs. TNFR2, still require further investigation [151, 152].

The introduction of anti-TNFα therapy in the late 1990s marked a significant advancement in managing CD and UC. The anti-TNFα landscape includes infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira), certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), and golimumab (Simponi) [153–156]. While all approved anti-TNFα agents work by blocking TNFα binding to TNFR, they exhibit differences in their molecular mechanisms, clinical efficacy profiles, and side effect considerations. Infliximab is a chimeric antibody with a murine variable region, which leads to substantially higher immunogenicity and more risk of ADAbs development in humans compared to other fully human antibodies. Adalimumab and golimumab are fully human monoclonal antibodies. These three antibodies have human IgG1 Fc capable of Fc receptor binding and complement activation. In contrast, certolizumab pegol is a PEGylated Fab' fragment that lacks the Fc region and lacks the Fc receptor binding or complement activation. Infliximab is given intravenously, while adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol are administered subcutaneously, offering more convenience for patients [157–160].

Infliximab demonstrated significant efficacy for both induction and maintenance therapy phases for moderate-to-severe UC and CD. The ACT 1 and ACT 2 trials for UC showed significantly higher clinical response rates with Infliximab compared to placebo at Week 8, sustained through Week 30 and even Week 54 [101]. For CD, the ACCENT I and ACCENT II trials confirmed infliximab’s effectiveness in achieving remission and allowing CS withdrawal for both luminal and fistulizing disease, with prolonged response through maintenance therapy [99, 100]. Beyond infliximab, other TNFα monoclonal antibodies such as adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol also proved efficacious and safe in their respective Phase 3 clinical trials (with primary endpoints summarized in Table 1), leading to their approval for patients with moderate-to-severe UC or CD who were refractory to conventional treatments.

Infliximab and adalimumab are considered highly effective for both inducing and maintaining remission in CD and UC, substantially easing the need for surgery and hospitalization [161, 162]. Despite molecular differences, retrospective studies and network meta-analyses suggest that infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab pegol generally demonstrate similar therapeutic efficacy in CD, especially regarding CS reduction and quality of life [163, 164]. For UC, infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab all showed good efficacy in inducing and maintaining remission. The treatment selection is often guided by insurance, administration, and patient preference. Nevertheless, some analyses indicate infliximab may be more effective than adalimumab for inducing remission in anti-TNFα naive patients with UC, whereas golimumab appears less effective than infliximab and adalimumab in UC [165, 166]. Additionally, it’s hypothesized that infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab may offer superior efficacy for IBD compared to certolizumab pegol due to their ability to induce apoptosis in tmTNF-expressing immune or tissue cells via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), mechanisms that are not associated with certolizumab pegol [167, 168]. However, it is important to note that direct head-to-head clinical trials comparing all TNFα inhibitors are limited, making direct comparisons challenging due to variations in clinical trial design, patient populations, and endpoints.

Despite their pivotal role, anti-TNF therapies are not universally effective. Up to 40% of patients exhibit primary non-response (PNR), characterized by no initial response to treatment, while approximately 23–46% experience secondary loss of response (LOR) within one year of initiating anti-TNFα therapy [169, 170]. This can be attributed to factors such as low trough serum drug concentrations and/or the presence of ADAbs, which may result in suboptimal drug concentrations or impaired TNF neutralization. Given the dose-related therapeutic benefit of anti-TNF agents, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), which involves measuring serum trough levels and ADAbs, is widely advocated to optimize treatment [171, 172]. Other mechanisms, such as a shift in the pathogenesis to alternative cytokine pathways, may also contribute. For patients exhibiting low drug concentrations who are either ADAb-negative or have low ADAb levels, a dose escalation or shorter intervals between infusions of the current anti-TNF may be considered. If high ADAb levels are observed and the patient has a history of benefiting from anti-TNF therapy, switching within the TNF class (cycling) could be a viable option, given that ADAbs are typically molecule-specific. However, if a patient does not achieve a robust therapeutic response with an initial anti-TNF despite adequate drug trough levels, or if an inadequate response persists after TDM-guided dose escalation or cycling (suggesting PNR, alternative pathogenesis, or different pathways), clinicians may consider switching to another class of targeted drug with a different MoA (swapping), such as JAK inhibitors, anti-integrins, or anti-ILs [172, 173].

Moreover, anti-TNF therapies generally share comparable safety profiles, and they can be associated with several serious AEs. A primary concern is the increased risk of severe infections, including reactivation of latent tuberculosis (TB) [174, 175]. Consequently, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends comprehensive TB screening, including medical history, physical examination, and either a tuberculin skin test (TST) or an IFN-γ release assay (IGRA), along with a chest X-ray if indicated, prior to treatment initiation [176]. Furthermore, anti-TNF agents carry a black box warning from the FDA due to an increased risk of malignancies, particularly lymphoma, and a potentially doubled risk of non-melanoma skin cancer. Therefore, caution is advised when prescribing these agents to patients with a history of malignancy or other risk factors [177–179].

Additionally, to further enhance their efficacy and mitigate immunogenicity, anti-TNF agents are often administered as combination therapy with an immunomodulator. For instance, combining thiopurines with TNF blockades is generally more efficacious than monotherapy for both inducing and maintaining remission in CD and UC. This approach leads to higher rates of CS-free clinical remission and improved mucosal healing. It may also help reduce the development of ADAbs against TNF inhibitors, such as infliximab, thereby preserving their long-term effectiveness [180, 181]. However, the risks and benefits of such combination therapy, particularly in older individuals, require careful consideration due to an elevated risk for serious infections and lymphomas. Moreover, the incidence of the other side effects, including serious infections and psoriasiform eczematous skin reactions, has also highlighted the need for ongoing drug development efforts of newer therapeutics with potentially improved safety profiles [180, 181].

IL-12 and IL-23 are critical pro-inflammatory cytokines that are primarily produced by antigen-presenting cells [APCs; e.g., macrophages or dendritic cells (DCs)]. IL-12 is composed of p35 and p40 subunits, while IL-23 consists of p19 and p40 subunits. Despite sharing the p40 subunit, they have distinct functions: IL-12 drives Th1 cell differentiation and antimicrobial responses, whereas IL-23 is important for Th17 cell polarization and activation, which are key to chronic inflammation [182, 183]. Preclinical studies reported that both IL-12 and IL-23 are responsible for IBD pathophysiology via intestinal inflammation [182–185]. This has led to the development of IL-12/23 targeted therapies. FDA-approved anti-IL-12/23 or IL-23 IBD therapeutics include ustekinumab (Stelara; FDA approved in 2016 for CD, and 2019 for UC), an earlier anti-IL-12/23p40 agent, and a newer class of IL-23p19-specific antagonists such as risankizumab (Skyrizi; 2022 for CD and 2024 for UC), mirikizumab (Omvoh; 2023 for UC and 2025 for CD), and guselkumab (Tremfya; 2024 for UC and 2025 for CD) (Figure 2). By selectively targeting p19, these newer anti-IL-23 agents offer a more precise approach that spares IL-12-mediated pathways, leading to improved efficacy and a better balance of immune responses. Given their proven effectiveness in both biologic-naive and biologic-experienced patients, these anti-IL-12/23 and IL-23 agents are often recommended as first- or second-line therapies for IBD [8, 186].

Ustekinumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to the common p40 subunit shared by IL-12 and IL-23. This binding prevents the interaction of these cytokines with the IL-12R (IL-12Rβ1) on the surface of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, thereby inhibiting downstream inflammatory signaling cascades crucial for intestinal inflammation [187, 188]. Ustekinumab is approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe CD and UC. Its efficacy in CD was demonstrated across the UNITI clinical program (Table 1). The UNITI-1 trial assessed ustekinumab in CD patients with prior anti-TNF failure, while UNITI-2 focused on a conventional therapy failed or intolerable cohort. Significant outcomes were observed at Week 6, with clinical response rates of 33.7% (UNITI-1) and 55.5% (UNITI-2), respectively [122, 123]. Furthermore, 53.1% patients from these two trials maintained clinical remission by Week 44 during the maintenance trial (IM-UNITI) [123]. For UC, the UNIFI induction trial showed that patients receiving ustekinumab achieved significantly higher clinical remission rates at Week 8 (15.5%) compared to placebo (5.3%, P < 0.001) [124]. The maintenance trial demonstrated sustained clinical remission, with 43.8% of patients on ustekinumab maintaining remission compared to 24.0% of those on placebo (P < 0.001) [124]. Importantly, the incidence of serious adverse events with ustekinumab was similar to that observed with placebo. Furthermore, extensive pooled safety analyses of ustekinumab from six clinical trials (T07, CERTIFI, UNITI-1, UNITI-2, IM-UNITI, and UNIFI), with up to five years of follow-up in CD and four years in UC, revealed its comparable safety profile to placebo. No significant differences were observed in major safety events, including major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), malignancies, or opportunistic infections [189].

Risankizumab is a humanized IgG monoclonal antibody that precisely targets the p19 subunit of IL-23, thereby inhibiting the IL-23/Th17 pathway, a key driver of inflammation in IBD [190]. This specific targeting is hypothesized to enhance safety by preserving crucial IL-12-mediated Th1 immune responses vital for host defense, potentially offering greater efficacy in more advanced stages of IBD compared to anti-IL-12/23p40 antibodies (e.g., ustekinumab) [183, 184]. Risankizumab was approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe CD and UC. Risankizumab’s efficacy in CD was demonstrated in the ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials [125]. In ADVANCE, 42% of patients intolerant or with inadequate response to prior biologics or conventional therapy achieved clinical remission by Week 12 (vs. 25% placebo, P ≤ 0.0001) [125]. The MOTIVATE trial, which focused on patients who had failed or were intolerant to prior biologic therapy, showed a 40% clinical remission rate and 34% endoscopic response [125]. For the maintenance phase, the FORTIFY study confirmed sustained clinical remission at Week 52 in 52% of patients [126]. Furthermore, in the SEQUENCE head-to-head trial, risankizumab demonstrated superiority over ustekinumab (an anti-p40 antibody) in inducing endoscopic remission, with significantly more patients achieving this outcome by Week 48 (31.8% vs. 16.2%, P < 0.001) [128]. Both treatments showed a similar incidence of adverse events. The COMMAND study also highlighted risankizumab’s efficacy in UC, with clinical remission rates at Week 52 reaching 40% (180 mg) and 38% (360 mg) compared to 25% with placebo (both P < 0.001) [127]. Furthermore, risankizumab is associated with a low incidence of ADAbs and currently has no malignancy-related warnings in its prescribing information, with a favorable safety profile supported by nearly nine years of real-world clinical experience across approved indications in patients [191].

Mirikizumab is another humanized anti-p19 monoclonal antibody, thereby selectively inhibiting the IL-23 signaling pathway. The efficacy of mirikizumab in UC was reported in LUCENT-1 induction trial and LUCENT-2 maintenance trial [130]. Significantly higher percentages of patients in the mirikizumab group than in the placebo group had clinical remission at Week 12 (24.2% vs. 13.3%, P < 0.001) and at Week 52 (49.9% vs. 25.1%, P < 0.001) [130]. For CD patients, the Phase 3 CD-1 trial demonstrated mirikizumab’s significant efficacy [129]. At Week 52, patients treated with mirikizumab achieved substantially higher rates of endoscopic response (46% vs. 23% for placebo; P < 0.001) and clinical remission by Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI; 53% vs. 36% for placebo; P < 0.001) [129]. Sequentially, the long-term efficacy and safety of mirikizumab in CD patients were further assessed for up to five years in VIVID-2, the Phase 3 extension trial. The trial demonstrated robust long-term outcomes: 79.0% of patients showed a clinical remission by CDAI and 72.5% achieved endoscopic remission by three years [192].

Guselkumab also selectively targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. Guselkumab received US FDA approval for UC and CD [193]. The efficacy of guselkumab in UC was demonstrated in the QUASAR clinical program [134]. The QUASAR induction study demonstrated that guselkumab significantly improved clinical remission (23% vs. 8% for placebo; P < 0.001) and response rates by Week 12 in patients with moderate-to-severe UC. Furthermore, the QUASAR maintenance study confirmed sustained clinical and endoscopic remission through Week 44. Notably, in the QUASAR maintenance study, guselkumab demonstrated significant rates of objective disease remission, specifically achieving endoscopic and histologic remission. Attaining these endpoints is crucial for complete mucosal healing and improved long-term patient outcomes. Across the entire QUASAR program, guselkumab’s safety profile remained consistent with its established safety in all approved indications [134]. Guselkumab has demonstrated strong efficacy in CD across multiple clinical trials. The GRAVITI trial showed significant clinical remission (56% vs. 22% placebo) and endoscopic response (34% vs. 15% placebo) at Week 12 [131]. Additionally, a prespecified exploratory endpoint in GRAVITI revealed that deep remission (clinical and endoscopic remission) at Week 48 was achieved in 26% to 35% of guselkumab-treated patients, compared to 4% on placebo [131]. Furthermore, the 48-week GALAXI-2 and GALAXI-3 trials established guselkumab’s superiority over ustekinumab for moderately to severely active CD [132]. These identically designed studies consistently showed guselkumab achieved significantly higher rates of endoscopic healing and deep remission (Table 1). Pooled data from these trials also highlighted guselkumab’s outperformance over ustekinumab across several endoscopic endpoints at Week 48, with a comparable safety profile [132]. These findings suggest guselkumab could be a more effective treatment option for CD patients than ustekinumab.

In IBD, the over-accumulation of lymphocytes in the gut is the consequence of their dysregulated movement from secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs). Lymphocytes enter the bloodstream from bone marrow and travel to lymph nodes via high endothelial venules (HEVs), where they are primed by APCs. This priming can also occur locally within the gut’s lamina propria or Peyer’s patches. Once primed, these lymphocytes re-enter the bloodstream and are led to the intestine by specific surface receptors such as integrins. This process is further supported by upregulated chemokines and selectins that facilitate firm adhesion to HEVs and subsequent transmigration into intestinal tissue. The homing of lymphocytes to gut mucosal tissues is tightly regulated by chemokines, adhesion molecules, and gut-specific metabolites [194, 195]. Thus, a key therapeutic strategy in IBD is to inhibit this leukocyte trafficking by targeting adhesion molecules and their pathways. The α4β7 integrin is specifically relevant, as it is preferentially expressed on gut-activated lymphocytes and binds to its ligand, mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1), expressed on the gut vascular endothelium. Targeting the integrin-ligand axis can offer a gut-selective approach to immune modulation, effectively preventing pathogenic T lymphocytes from excessively entering the intestinal lamina propria from SLOs [194–196].

Natalizumab, an anti-α4 monoclonal antibody, is the first integrin antagonist approved for IBD [196]. The ENCORE CD trial demonstrated its efficacy, with 48% of natalizumab recipients achieving clinical response at Week 8 sustained through Week 12 compared to 32% on placebo (P < 0.001), and 26% achieving sustained remission vs. 16% on placebo [115]. Despite its efficacy, natalizumab can lead to an increased risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a severe brain infection caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV) due to the suppressed immune cell migration and surveillance. Given these safety concerns, the use of natalizumab is largely restricted to JCV-negative patients. Initially approved for multiple sclerosis (MS) in 2004, natalizumab was voluntarily withdrawn in 2005 due to safety concerns, but later reinstated in 2006 for MS and in 2008 for CD under strict monitoring programs [197, 198].

As a notable advancement over natalizumab, the integrin blockade vedolizumab selectively targets the α4β7 integrin expressed on B and T lymphocytes [196]. By blocking its interaction with MAdCAM-1, predominantly expressed in the digestive tract vasculature, vedolizumab precisely prevents inflammatory cell migration into the gut while preserving central nervous system (CNS) immune cell function [196]. Vedolizumab has shown robust efficacy in IBD. In the GEMINI 1 trial for UC, vedolizumab demonstrated a significant clinical response rate of 47.1% at Week 6, compared to 25.5% in the placebo group [116]. Notably, at Week 52, 41.8% of patients who continued vedolizumab therapy remained in clinical remission, a substantial improvement over the 15.9% of patients who switched to placebo (P < 0.001) [116]. In CD, vedolizumab demonstrated its efficacy in the GEMINI 2 trial, which notably included a significant proportion of patients (67.7%) with prior anti-TNF exposure. At Week 6, vedolizumab achieved a clinical remission rate of 14.5% compared to 6.8% with placebo (P = 0.02) [117]. By Week 52, vedolizumab continued to show significant benefits: 39.0% of patients on induction therapy achieved clinical remission compared to 21.6% observed in the placebo group (P < 0.001) [117]. Long-term safety data from the GEMINI LTS program have consistently revealed no new safety signals and, notably, no cases of PML [199]. The overall risk of infection remains low, with non-serious upper respiratory symptoms being the most common [199]. Furthermore, network meta-analyses have indicated that vedolizumab is associated with a lower risk of serious infections in UC compared to anti-TNF therapies [200]. Vedolizumab was approved as a second-line treatment for both moderate-to-severe UC and CD, specifically indicated for patients who haven’t adequately responded to, or are intolerant of, prior therapies such as steroids, immunomodulators, or TNF inhibitors.

Etrolizumab is another humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the β7 subunit common to both α4β7 and αEβ7 integrins [201, 202]. By concurrently inhibiting their interactions with MAdCAM-1 and E-cadherin, etrolizumab aims to reduce the infiltration of inflammatory T cells and cytotoxic intraepithelial lymphocytes within the gut mucosa [201, 202]. Etrolizumab has shown mixed results in clinical trials for both UC and CD [203, 204]. During the HIBISCUS I induction study, etrolizumab met its primary endpoint, while the treatment did not meet the primary endpoint in the HIBISCUS II induction study [203]. The drug was also studied in the HICKORY trial in patients with prior anti-TNF treatment, where it met the primary endpoint as an induction therapy but not as maintenance [205]. Its development has been abandoned due to disappointing trial results. Adding to the therapeutic landscape, ABBV-382, a novel investigational anti-α4β7 antibody, is now in Phase 2 clinical development for CD (NCT06548542).

Beyond a4β7 integrin, researchers have investigated other adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors as therapeutic targets for gut inflammation in IBD. For example, alicaforsen, an antisense oligonucleotide targeting intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1; the ligand for integrin αLb2), did not induce clinical remission in active UC [206, 207]. However, a small retrospective study indicated potential efficacy in treating pouchitis, inflammation of the surgically created pouch after proctocolectomy in IBD patients [207]. This suggests that while αLb2-mediated adhesion may not be broadly critical in active UC, it could play a specific role in localized inflammatory conditions like pouchitis.

An early investigational drug, vercirnon, blocks C-C chemokine receptor 9 (CCR9). CCR9 and its ligand, CCL25, are essential for recruiting immune cells, particularly T lymphocytes, to the small intestine [208, 209]. Despite initial promise in preclinical and early-phase clinical trials for reducing inflammation and maintaining remission, vercirnon was not superior to placebo in inducing clinical remission in Phase 3 trials for CD. This lack of efficacy may be associated with redundancy of immune cell homing pathways, where other chemokines or adhesion molecules compensate for CCR9 blockade, or insufficient inhibition of all CCR9-mediated effects [209, 210]. The intricate and often redundant nature of chemokine-mediated immune responses in IBD suggests that suppressing a single chemokine pathway might be insufficient if alternative pathways for immune cell recruitment exist [210]. Other investigational antibodies (e.g., AZD7798) involve depleting the CCR9-expressing lymphocytes and preventing them from homing to the small bowel for a better reduction of inflammation in IBD.

In a related approach, eltrekibart (LY3041658), a monoclonal antibody, is currently in Phase 2 development for treating moderate-to-severe UC (NCT06598943). Eltrekibart works by neutralizing all seven Glu-Leu-Arg motif positive (ELR+) CXC chemokines (CXCL1–3 and CXCL5–8), which are known to drive inflammation by signaling through the C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CXCR1) and CXCR2 [211].

TL1A protein is encoded by the TNFSF15 locus (a strong genetic variant linked to IBD in GWAS) and mainly produced by APCs. TL1A plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of IBD through its binding with death receptor 3 (DR3), which activates downstream pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). This signaling promotes the activation of pro-inflammatory T cells, including Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells, thereby exacerbating the inflammatory response in IBD [212, 213]. Beyond inflammation, TL1A is also implicated in driving fibrosis, a process of excessive tissue scarring that can lead to severe complications such as strictures in IBD, especially in CD. Given its dual role in promoting both inflammation and fibrosis, TL1A has emerged as a promising therapeutic target for treating IBD. Consequently, anti-TL1A monoclonal antibodies are an emerging class of therapeutics in clinical development, showing encouraging efficacy in trials for both UC and CD. These TL1A antibodies have demonstrated significant improvements across key endpoints, including clinical remission rates, endoscopic healing, and histologic outcomes [212, 213].

An investigational anti-TL1A antibody, RVT-3101, also known as afimkibart (or PF-06480605, RG6631, RO7790121), has shown promise in downregulating tissue Th1 and Th17 cytokine responses and achieving significant endoscopic improvements in moderate-to-severe UC in Phase 2 trials TUSCANY and TUSCANY-2 [214, 215]. In the Phase 2a TUSCANY trial, Week 14 endoscopic improvement was observed in a statistically significant proportion of participants [38.2% (uniformly minimum-variance unbiased estimator, per protocol population)] receiving PF-06480605 500 mg intravenous (IV) Q2W. Sustained target engagement was also reported through treatment dependent accumulation in soluble TL1A (sTL1A) concentration [214]. The sequential Phase 2b TUSCANY-2 also demonstrated improved efficacy from the induction to the chronic period. Specifically, at Week 56, RVT-3101 (formerly PF-06480605) treatment led to 36% clinical remission, 50% endoscopic improvement, and 21% endoscopic remission. These results represent a notable increase compared to the Week 14 figures of 29% clinical remission, 36% endoscopic improvement, and 11% endoscopic remission, respectively [215]. Furthermore, the reported safety profile remained well-tolerated throughout the 56-week period, with no observable impact of immunogenicity on clinical efficacy or safety results [215]. Two Phase 3 trials for afimkibart (RVT-3101) in UC began in 2024 to assess its long-term efficacy and safety. Additionally, two more Phase 3 trials for moderate-to-severe CD recently started in 2025 (Table 2).

Another promising anti-TL1A agent, tulisokibart (MK-7240, PRA023), also demonstrated positive results in the Phase 2 ARTEMIS-UC trial, showing significant clinical remission in patients with moderately to severely active UC, including those who had failed other therapies [216]. A 12-week treatment trial evaluated IV tulisokibart (1,000 mg on day 1, followed by 500 mg at Weeks 2, 6, and 10). The results showed that a significantly higher percentage of patients receiving tulisokibart achieved clinical remission compared to those on placebo (32% vs. 11%; P = 0.02). The incidence of adverse events was similar in the tulisokibart and placebo groups (46% vs. 43% in placebo) [216]. Interestingly, this trial also incorporated a novel genetic-based diagnostic test, developed using a machine-learning approach, to identify patients with an increased likelihood of response to treatment. However, this Phase 2 trial ultimately didn’t provide evidence that this genetic test successfully identified patients more likely to respond to TL1A inhibition. This outcome might have been influenced by a higher incidence of remission in the placebo group among patients with a “positive” test result for likelihood of response compared to the unstratified cohort (11% vs. 1%) [216]. A recently published proof-of-concept Phase 2a APOLLO-CD trial suggests that tulisokibart may be efficacious in patients with moderately to severely active CD, with 26% of those receiving the drug achieving a response at Week 12 [217]. However, randomized controlled trials of longer duration are needed to confirm these preliminary results. Tulisokibart is currently undergoing investigation in three Phase 3 clinical trials (ATLAS-UC, ARES-CD, MK-7240-011) for the treatment of moderately to severely active UC and CD (Table 2).

Duvakitug (TEV-48574/SAR447189), another investigational IgG1-λ2 TL1A antibody, is currently in Phase 2 clinical development for IBD. The Phase 2b RELIEVE trial showed promising clinical efficacy for duvakitug in both UC and CD. In the UC cohort, 36% of patients on the 450 mg dose and 48% on the 900 mg dose achieved the primary endpoint of clinical remission at Week 14, compared to 20% on placebo. Similarly, in the CD cohort, 26% of patients receiving 450 mg and 48% receiving 900 mg reached the primary endpoint of endoscopic response, vs. 13% on placebo [218]. Notably, higher clinical remission rates were observed for duvakitug compared to placebo in both AT-experienced and AT-naive patient subgroups across both cohorts [218]. A Phase 3 program for duvakitug is anticipated to begin in the second half of 2025 [219].

Anti-IL-36R: The IL-36 cytokine family (IL-36α, β, γ) is significantly upregulated in intestinal inflammation in IBD [220]. IL-36α and γ are mainly produced by gut-resident cells, proteolytically activated by neutrophil enzymes, enabling them to bind to the IL-36R, a heterodimer of IL-1Rrp2 and IL-1RAcP. This binding triggers pro-inflammatory signaling in immune cells such as DCs, macrophages, and T lymphocytes, driving inflammatory responses. Conversely, natural antagonists such as IL-36Rα and IL-38 inhibit IL-36R activation, demonstrating anti-inflammatory effects [220, 221]. Spesolimab is a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting IL-36R. Despite its hypothesized anti-inflammatory role in IBD, spesolimab has not shown significant efficacy in clinical trials for IBD [222, 223]. A Phase 2 trial for moderate-to-severe UC did not demonstrate improved clinical remission rates compared to placebo at Week 12. Similarly, studies in fistulizing CD have lacked conclusive evidence of spesolimab’s effectiveness, leading to the termination of a Phase 2 long-term treatment study for fistulizing CD in 2022 [222, 223].

Anti-IL-1α/β: IL-1α and IL-1β are important pro-inflammatory cytokines in IBD pathogenesis. While IL-1β acts primarily as a soluble mediator, IL-1α has a dual function, serving as both a ligand for the IL-1R1 and an intracellular transcription factor. After being released from necrotic cells, IL-1α can also act as an alarmin to initiate inflammation. Given the distinct roles of IL-1α and β, simultaneously targeting both cytokines may offer a therapeutic advantage [224]. Lutikizumab (ABT-981) is a novel dual variable domain immunoglobulin (DVD-Ig) designed to neutralize both IL-1α and β [225, 226]. This investigational drug is currently in Phase 2 clinical development for both UC and CD (Table 2).

Anti-IL-4/13: IL-4 and IL-13 are important Th2 cytokines traditionally linked to allergic reactions and parasitic infections [227]. They were also reported to be involved in the inflammatory cascade in IBD, especially UC. IL-13 has been identified as a key effector cytokine in UC, potentially acting directly on epithelial cells to increase barrier permeability and promote inflammation [228, 229]. While dual blockade of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling has shown success in multiple allergic conditions (e.g., atopic dermatitis, asthma, etc.), the precise role of IL-4 and IL-13 cytokines in IBD remains an active area of investigation, with ongoing research exploring their potential as therapeutic targets. Dupilumab, the antagonist targeting the shared alpha subunit of the IL-4R and IL-13R (IL-4Rα), is currently undergoing Phase 2 clinical assessment in the LIBERTY-UC SUCCEED trial (NCT05731128, Table 2) for moderately to severely active UC with an eosinophilic phenotype.

Beyond established treatments, a broader range of biologic agents are currently in development, targeting diverse mechanisms to modulate the immune response. These include therapies focused on cytokine or receptor blockade (such as IL-2, IL-6, and IL-31 pathways) and immune checkpoint enhancers like P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) [230–232].

Small molecule drugs represent a significant advance in IBD therapeutics due to their ability to readily penetrate cellular membranes and modulate intracellular signaling pathways. These orally bioavailable, chemically synthesized compounds offer several advantages over injectable biologics: convenient oral administration for improved patient compliance, lower manufacturing costs for enhanced accessibility, non-immunogenicity, and superior tissue penetration for effective intracellular targeting [233, 234]. Clinical studies on small molecules like JAK inhibitors, phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors, and S1PR modulators are detailed in Table 3 for IBD treatment.

Drug development pipeline for IBD: small molecule therapies*.

| MoA | Drug name | Indication | RoA | Highest clinical stage | Clinical trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JAK1-biased inhibitor | Filgotinib (Jyseleca; GLPG0634) | UC, CD | PO | UC: EU, UK, and Japan approvedCD: Ph3 completed | NCT02914522; NCT06865417; NCT02914535; NCT06964113; NCT02914561 |

| JAK1-biased inhibitor | Ivarmacitinib (SHR0302) | UC, CD | PO | UC: Ph3 unknown statusCD: Ph2 completed | NCT05181137; NCT03675477; NCT03677648 |

| Pan JAK inhibitor | Izencitinib (TD-1473) | UC, CD | PO | UC: Ph2/3 terminatedCD: Ph2 terminated | NCT03920254; NCT03758443; NCT03635112 |

| Pan JAK inhibitor | Peficitinib (JNJ-54781532) | UC | PO | Ph2 completed | NCT01959282 |

| TYK2/JAK1 inhibitor | Brepocitinib (PF-06700841) | UC, CD | PO | UC: Ph2 completedCD: Ph2 completed | NCT02958865; NCT03395184 |

| JAK3/TEC family inhibitor | Ritlecitinib (PF-06651600) | UC, CD | PO | UC: Ph2 completedCD: Ph2 completed | NCT02958865; NCT03395184 |

| TYK2 inhibitor | Zasocitinib (TAK-279) | UC, CD | PO | UC: Two Ph2 recruitingCD: Two Ph2 recruiting | NCT06254950; NCT06233461; NCT06764615 (joint for UC and CD) |

| TYK2 inhibitor | Deucravacitinib (BMS-986165) | UC, CD | PO | UC: Ph2 completedCD: Ph2 completed | NCT04613518; NCT03934216; NCT04877990 |

| JAK1/TYK2 inhibitor | TLL018 | UC | PO | Ph2 withdrawn | NCT05121402 |

| JAK3/TYK2/Ark5 inhibitor | OST-122 | UC | PO | Ph1/2 completed | NCT04353791 |

| S1PR1 modulator | Tamuzimod (VTX002) | UC | PO | Ph2 ongoing | NCT05156125 |

| TNFα inhibitor | Balinatunfib (SAR441566) | CD, UC | PO | UC: Ph2 recruitingCD: Ph2 recruiting | NCT06867094; NCT06637631 |

| PDE4 inhibitor | Mufemilast (Hemay005) | UC | PO | Ph2 ongoing | NCT05486104 |

| PDE4 inhibitor | Apremilast | UC | PO | Ph2 completed | NCT02289417 |

| PDE4 inhibitor | Tetomilast (OPC-6535) | UC, CD | PO | UC: Ph3 completedCD: Ph2/3 completed | NCT00092508; NCT00064454; NCT00064441; NCT00989573 |

| α4β7 inhibitor | GS-1427 | UC | PO | Ph2 recruiting | NCT06290934 |

| α4 inhibitor | AJM300 (carotegrast methyl) | UC | PO | Ph3 completed | NCT03531892 |

| α4β7 inhibitor | MORF-057 | CD, UC | PO | UC: Ph2b ongoingCD: Ph2 recruiting | NCT05611671; NCT05291689; NCT06226883 |

| SYK inhibitor | Lanraplenib (BI 3032950) | UC | IV, SC | Ph2 ongoing | NCT06636656 |

| TPL2 inhibitor | Tilpisertib fosmecarbil (GS-5290) | UC | PO | Ph2 recruiting | NCT06029972 |

| RIPK1 inhibitor | SAR443122 (DNL758) | UC | PO | Ph2 recruiting | NCT05588843 |

| Renin inhibitor | SPH3127 | UC | PO | Ph2 completed | NCT05019742; NCT05770609 |

| NLRP3 inhibitor | Usnoflast (ZYIL1) | UC | PO | Ph2 completed | NCT06398808 |

| ALK5 inhibitor | AGMB-129 | CD | PO | Ph2 ongoing | NCT05843578 |

| IL-23 inhibitor | Icotrokinra (JNJ-77242113) | UC | PO | Ph2 ongoing | NCT06049017 |

*: The search on ClinicalTrials.gov was completed by July 1st, 2025. IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; MoA: mechanism of action; RoA: route of administration; JAK1: Janus kinase 1; UC: ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; PO: oral administration; TYK2: tyrosine kinase 2; Ark5: AMP-activated protein kinase-related protein kinase 5; S1PR1: sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; PDE4: phosphodiesterase 4; SYK: spleen tyrosine kinase; IV: intravenous; SC: subcutaneous; TPL2: tumor progression locus 2; RIPK1: receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 1; NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; ALK5: activin receptor-like kinase 5; IL: interleukin.

Dysfunctional cytokine-JAK-STAT pathway activities have been demonstrated as hallmarks of numerous autoimmune disorders, including IBD [233–235]. JAK inhibitors are a class of small molecules designed to target the JAK/STAT pathways and treat inflammatory cytokine-mediated diseases [233–235]. JAK inhibitors work through binding and inhibiting the activation of JAK enzymes [JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2)], thus disrupting the inflammatory signaling cascade and controlling immune responses [234, 235].

Tofacitinib, a pan JAK inhibitor, was the first oral targeted therapy approved for UC (2018) [236, 237]. In the OCTAVE 1 and 2 induction trials, patients receiving 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily achieved clinical remission rates of 19% and 17%, respectively, compared to 8% and 4% for those on placebo (P = 0.007 and P < 0.001) [135, 136]. The therapeutic effect was similar regardless of TNFi-exposure status [135, 136]. In the OCTAVE sustain maintenance trial, Week 52 clinical remission rates were 34% (5 mg group) and 41% (10 mg group), significantly higher than 11% in the placebo group (P < 0.001 for both). However, tofacitinib carries an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, particularly in patients aged over 65 years, those with previous TNFα agent failure, and individuals of Asian ethnicity [135, 136].

A more selective JAK inhibitor, upadacitinib, has also been assessed in Phase 3 trials in patients with moderate-to-severe active CD and UC [236, 237]. In two Phase 3 induction trials for CD (U-EXCEL and U-EXCEED), upadacitinib demonstrated significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic response compared to placebo in patients with CD. Furthermore, in the U-ENDURE maintenance trial, upadacitinib showed superior clinical remission and endoscopic response rates at Week 52 compared to placebo. All these improvements were statistically significant (P < 0.001) [137]. The subsequent U-ENDURE long-term extension study demonstrated that upadacitinib maintenance therapy provided sustained CS-sparing effects over two years in CD patients [138]. In the U-ACHIEVE [139] and U-ACCOMPLISH [139] induction trials for UC, upadacitinib achieved clinical remission in 26% and 34% of patients, respectively, compared to 5% and 4% for placebo (P < 0.0001 for both) [139]. In the U-ACHIEVE maintenance trial, 15 mg and 30 mg upadacitinib achieved clinical remission rates of 42% and 52% respectively, vs. 12% for placebo (P < 0.0001 for both) by Week 52 [139]. Upadacitinib gained approval for UC in 2022 and CD in 2023, further expanding the oral therapeutic options for IBD patients.

First-generation non-selective JAK inhibitors are linked to an increased risk of infection, particularly herpes zoster, for which the recombinant zoster vaccine is recommended [238]. The ORAL surveillance study highlighted serious safety concerns with JAK inhibitors, reporting higher rates of MACE and cancers in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tofacitinib compared to anti-TNF agents. These findings led to a black box warning for all JAK inhibitors, including upadacitinib, regarding malignancies and venous thromboembolism (VTE), specifically pulmonary embolism and increased mortality [239, 240]. Prescribing information advises monitoring for new malignancies and considering patient history, with periodic skin evaluations recommended for non-melanoma skin cancer. Furthermore, these drugs can affect laboratory values, including dose-dependent increases in lipid levels (tofacitinib), elevated aminotransferase levels (tofacitinib and upadacitinib), and changes in blood counts such as anemia (tofacitinib), neutropenia, and lymphopenia (upadacitinib) [239, 240].

Second-generation JAK inhibitors aim to overcome the limitations of pan JAK inhibitors and improve their safety profile by achieving greater selectivity within the JAK family. Several of these highly selective agents are currently undergoing clinical development for both UC and CD, including filgotinib (JAK1-biased; approved for UC in EU), ivarmacitinib (JAK1-biased), brepocitinib (JAK1/TYK2-biased), deucravacitinib (TYK2-selective), etc. [236, 237].

Filgotinib (GS-6034, GLPG0634; Jyseleca) is an oral, JAK1-biased inhibitor [237]. The SELECTION trial demonstrated that filgotinib 200 mg effectively induced and maintained clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe UC, regardless of their prior biologic exposure. At Week 10, 26.1% of filgotinib-treated patients achieved clinical remission compared to 15.3% on placebo (P = 0.0157). This efficacy extended to Week 58, with 37.2% in remission vs. 11.2% on placebo (P < 0.0001) [241]. Importantly, serious adverse event rates were similar across treatment and placebo groups [241]. Despite its efficacy in UC, filgotinib 200 mg did not meet the co-primary endpoints for clinical remission and endoscopic response at Week 10 in the Phase 3 DIVERSITY trial for CD [242]. While approved for moderate-to-severe UC in the EU, UK, and Japan, the US FDA has withheld approval in the US due to concerns about potential testicular toxicity at the 200 mg dose, particularly its impact on sperm parameters, as indicated by preclinical studies.

The oral JAK1-biased inhibitor, ivarmacitinib (SHR0302), also shows promise for moderate-to-severe active UC, as demonstrated in the Phase 2 AMBER2 trial [243]. At Week 8, ivarmacitinib groups consistently exhibited significantly higher clinical response (e.g., 46.3% vs. 26.8% for placebo) and clinical remission rates (e.g., 22.0–24.4% vs. 4.9% for placebo) across various dosages. The drug was well-tolerated, with predominantly mild treatment-emergent adverse events comparable to placebo, and no major cardiovascular, thromboembolic events, or deaths reported [243]. A Phase 3 trial for UC has begun to further assess its efficacy and safety (NCT05181137).

Among the second-generation JAK inhibitors, deucravacitinib (Sotyktu) stands out as a highly selective TYK2 inhibitor, allosterically binding to TYK2 regulatory pseudokinase domain to inactivate its kinase activity. Deucravacitinib effectively inhibits signaling of pro-inflammatory cytokines that are crucial in inflammatory diseases, such as IL-23, IL-12, and type I IFNs. The high selectivity of deucravacitinib offers a differentiated safety profile compared to traditionally designed JAK kinase inhibitors [237]. However, clinical trials for deucravacitinib in IBD have shown mixed results: the Phase 2 LATTICE-UC study failed to meet the primary and secondary endpoints for UC, and the LATTICE-CD study in CD was terminated early after not meeting the co-primary endpoints, although some positive trends were observed [244, 245]. Deucravacitinib remains in Phase 2 development for UC (Table 3). Another TYK2 selective inhibitor, zasocitinib (TAK-279), is also being investigated in ongoing Phase 2 trials for both UC and CD (Table 3).

S1P is a bioactive lipid mediator with important functions in the immune system. The levels of S1P are regulated by the balance between its synthesis through sphingosine kinases and its degradation by the S1P lyase. S1P signals through plasma membrane G protein-coupled receptors (S1PR1–5) or directly acts on intracellular targets. S1PR1 plays an essential role in controlling the egress of lymphocytes from primary (thymus, bone marrow) and secondary (lymph nodes, spleen) lymphoid organs [246, 247]. The research of S1P/S1PR signaling in inflammation has led to the development of novel oral small molecule therapies for IBD. An S1PR1 and S1PR5 modulator, ozanimod (Zeposia), and a S1PR1, S1PR4, S1PR5 modulator, etrasimod (Velsipity), are two such agents approved for the treatment of UC [248].

Ozanimod acts by inducing the internalization and degradation of S1PR1, effectively preventing peripheral blood lymphocytes from egressing the lymph nodes. This mechanism reduces the number of activated lymphocytes circulating to inflammatory sites within the intestinal mucosa [249]. Pivotal TRUE NORTH trials in patients with moderate-to-severe UC demonstrated a significant clinical benefit. Clinical remission rates were markedly higher with ozanimod compared to placebo in both the induction phase (Week 10: 18.4% vs. 6.0%, P < 0.001) and the maintenance phase (Week 52: 37.0% vs. 18.5%, P < 0.001) [140, 141]. However, the first of two Phase 3 YELLOWSTONE induction studies evaluating ozanimod in moderate-to-severe CD did not meet its primary endpoint of clinical remission at Week 12 [250]. A comprehensive evaluation of the full YELLOWSTONE trial data is currently underway.

Regarding its safety profile, ozanimod is reported to be contraindicated in patients with cardiac arrhythmias, a history of myocardial infarction, concurrent monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) use, and untreated, severe sleep apnea [251]. While bradycardia increased during the TRUE NORTH study induction phase following ozanimod treatment, no new cardiac safety signals emerged in the 3-year extension study [140, 141]. To mitigate cardiac risks, current guidelines advise avoiding ozanimod in patients with significant cardiovascular disease, screening for conduction abnormalities with electrocardiogram (ECG), and using titration dosing. Healthcare providers should also assess for concomitant use of MAOIs or other medications that could potentially cause bradycardia, QTc prolongation, or arrhythmias, and monitor cardiovascular vitals. Another on-target side effect of ozanimod is reduced circulating lymphocytes, necessitating close monitoring for infections, with nasopharyngitis and herpes zoster being frequently reported [251]. Varicella immunity confirmation is recommended before starting ozanimod [251].

Etrasimod is an oral S1PR modulator with selectivity for S1PR1, S1PR4, and S1PR5 [248]. The ELEVATE UC programs notably highlighted its efficacy in moderate-to-severe UC patients [142]. At Week 52, clinical remission was achieved in 32% of patients treated with etrasimod, significantly outperforming placebo (7%) with a P value of < 0.0001 [142]. While etrasimod is approved for UC, there are currently no reported studies detailing its treatment effects in CD.