Affiliation:

1Department of Life, Health & Environmental Sciences, University of L’Aquila, 67100 L’Aquila, Italy

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7146-3852

Affiliation:

2Department of Clinical Disciplines, University ‘Alexander Xhuvani’ of Elbasan, 3001 Elbasan, Albania

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3212-3633

Affiliation:

1Department of Life, Health & Environmental Sciences, University of L’Aquila, 67100 L’Aquila, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5757-8346

Affiliation:

1Department of Life, Health & Environmental Sciences, University of L’Aquila, 67100 L’Aquila, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7027-2691

Affiliation:

1Department of Life, Health & Environmental Sciences, University of L’Aquila, 67100 L’Aquila, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5907-7078

Affiliation:

2Department of Clinical Disciplines, University ‘Alexander Xhuvani’ of Elbasan, 3001 Elbasan, Albania

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6661-8116

Affiliation:

1Department of Life, Health & Environmental Sciences, University of L’Aquila, 67100 L’Aquila, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9923-5445

Affiliation:

1Department of Life, Health & Environmental Sciences, University of L’Aquila, 67100 L’Aquila, Italy

Email: benedetta.cinque@univaq.it

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4510-9416

Explor Immunol. 2025;5:1003233 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2025.1003233

Received: July 22, 2025 Accepted: December 15, 2025 Published: December 30, 2025

Academic Editor: Francois Niyonsaba, Juntendo University, Japan

The article belongs to the special issue Immunology and Pain

Aim: The benefit of topical application of probiotics on pain and itching associated with skin disorders has become an increasingly intriguing topic in recent years. These effects are mainly associated with the anti-inflammatory activity of probiotics. Given the crucial role of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) in skin pathophysiology, here, the ability of Streptococcus thermophilus was evaluated, in comparison with Lactobacillus acidophilus, to inhibit two enzymes involved in endocannabinoid (eCB) degradation: fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL).

Methods: Bacterial lysates were obtained from both probiotics. FAAH and MAGL activities were assayed using fluorometric and colorimetric methods. The effect of probiotic lysates on FAAH and MAGL activities was also evaluated on human keratinocytes stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

Results: S. thermophilus inhibited both FAAH and MAGL, although to varying extents. In comparison, L. acidophilus had a minimal effect on FAAH and did not influence MAGL activity.

Conclusions: Although preliminary, our findings suggest that S. thermophilus may exert both potential analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects by modulating the ECS and reducing the degradation of EC, known to play a key role in immune regulation and inflammation. Results presented confirm the selective actions of probiotics and propose a novel mechanism that may contribute to the beneficial effects of S. thermophilus in alleviating signs and symptoms associated with inflammatory skin conditions. Our evidence shows significant inhibitory activity of S. thermophilus on FAAH and MAGL activity, suggesting its ability to influence skin conditions by modulating ECS and preventing the eCB degradation.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in proper amounts, improve host health [1]. Emerging evidence supports the effectiveness of specific probiotic strains and combinations in treating a wide range of disorders, including gastrointestinal and kidney diseases, dermatological conditions, bacterial vaginosis, mental disorders, and oral diseases [2–7]. Additionally, oral or topical probiotics have been shown to have beneficial effects in treating various inflammatory skin conditions, including acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and ichthyosis [8–13].

Recently, we reported in vitro evidence supporting the beneficial role of the lactic acid bacterium S. thermophilus in counteracting oxidative stress-induced cellular aging [14], accelerating the wound-healing process [15], and antagonizing skin fibrosis [16]. In a previous in vivo study, our group showed that the topical application of a cream containing S. thermophilus effectively alleviated symptoms and signs of atopic dermatitis, including inflammatory signs and itching [8]. Additionally, we conducted another in vivo study focusing on fractional CO2 laser resurfacing, where we evaluated the effectiveness of the same probiotic-containing cream in managing the inflammatory response associated with the laser treatment [17]. The results indicated a significant and quicker reduction in post-operative erythema and swelling compared to the standard treatment. Moreover, the same formulation tested in older subjects was also found to improve the lipid barrier and enhance resistance against age-related xerosis [18]. The mechanisms underlying these effects may be attributed, at least in part, to the increase in ceramide concentrations in the stratum corneum generated by sphingomyelinase activity derived from S. thermophilus [8, 18, 19].

In recent years, the use of probiotics in topical application for managing pain and itching associated with skin diseases has received increasing attention [20–22]. Current research, including both preclinical and clinical studies, highlights the pain-relieving properties of probiotics. These effects are primarily attributed to their ability to reduce inflammation, modulate the immune system, and produce compounds that alleviate pain [23–29]. Topical probiotic therapy has also been investigated in both animal and human models of skin injuries [30]. Overall, the results support the ability of certain probiotics to improve wound healing by promoting granulation tissue formation, improving collagen levels, and stimulating angiogenesis. Additionally, probiotics have been shown to reduce the concentration of pathogenic bacteria through species-specific antagonism and increase the production of antimicrobial peptides in various cells, including mast cells, epithelial cells, and adipocytes, thereby helping to maintain skin integrity [31].

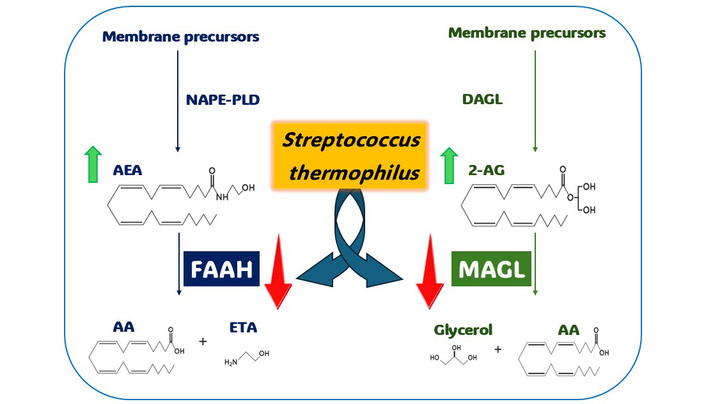

Recently, it has become clear that the endocannabinoid system (ECS) plays an important role in both healthy and diseased skin. Dysregulation of the ECS has been linked to various dermatological disorders, including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, scleroderma, and skin cancer [32, 33]. The ECS is composed of cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2), which are expressed by most skin-resident cells, endogenous cannabinoid ligands known as endocannabinoids (eCBs), enzymes that synthesize the eCBs, namely N-acyl-phosphatidylethanolamine-hydrolyzing phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD) and diacylglycerol lipase α (DAGLα), and catabolic enzymes, specifically, fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL).

eCBs are natural compounds that interact with cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2, which are crucial proteins throughout the body [34, 35]. The most studied eCBs are two types derived from arachidonic acid (AA): N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). Additionally, palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) and oleoylethanolamide (OEA) are important compounds classified as N-acylethanolamines (NAEs). These NAEs influence the processing of AEA and can interact with specific receptors, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α) and transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1).

The skin ECS involves several cell types, including keratinocytes, melanocytes, mast cells, fibroblasts, sebocytes, sweat gland cells, and hair follicle cells [36, 37]. This system plays a crucial role in maintaining skin homeostasis, regulating immune function, and influencing pigmentation. Some researchers have suggested a “C(ut)annabinoid” system for the skin, which is associated with skin fibrosis and wound healing in animals [38]. Interestingly, mitochondria also express CB1, and its activation appears to down-modulate mitochondrial activity. This mechanism may help limit excessive production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) [39]. Overall, the ECS serves to maintain an overall anti-inflammatory environment and inhibits proliferation, counteracting issues such as hypertrophic wound healing [40], excessive angiogenesis, and tumor growth [41–43].

Given the immunomodulatory properties of probiotics and the crucial role played by ECS in regulating inflammatory responses, particularly in relation to skin inflammatory pain, this preliminary study aims to investigate the potential of selected probiotic strains, particularly focusing on S. thermophilus, to directly inhibit two key enzymes involved in eCB degradation: FAAH and MAGL [44, 45]. The actions of these enzymes result in decreased availability and activity of eCB at their receptors, thereby impacting pain thresholds, among other effects. This highlights the increasing interest in novel and safe treatment strategies that can effectively inhibit FAAH and MAGL, with the potential to address conditions such as inflammatory pain and neuropathy.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate whether a probiotic can directly influence the activity of these key enzymes in the ECS, specifically FAAH and MAGL.

Two bacterial strains were used: S. thermophilus CNCM I-5570 and L. acidophilus CNCM I-5567 (kindly provided by Prof. Claudio De Simone). The bacterial lysates were obtained as previously described [14, 46]. Briefly, 1 g of lyophilized probiotics containing ~3.5 × 1011 CFU of S. thermophilus or L. acidophilus, was suspended in 10 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Euro Clone, West York, UK), centrifuged at 8,600 × g, washed twice, and then sonicated (30 min, alternating 10 s of sonication and 10 s of pause) using a Sonicator XL2020 (Misonix Incorporated, New Highway, Farmingdale, NY, USA). To verify bacterial cell disruption, the sample’s absorbance was measured at 590 nm (6132, Eppendorf Hamburg, Germany) before and after every sonication step. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 17,949 × g, and the supernatants were collected. The total protein content was measured using the DC Protein Assay (#5000116, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard (A3294, Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). For the FAAH and MAGL activity screening analyses, bacterial lysates were added to the assay systems to obtain final concentrations equivalent to 2, 5, or 10 mg/mL.

For cell treatments, based on our previous experience [14–16], the probiotic lysates were added to cell cultures at final concentrations of 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg protein/mL, which correspond to 0.3, 0.6, 1.2, and 2.4 mg/mL.

The influence of the bacterial strains on FAAH activity was evaluated using an in vitro fluorometric assay kit (No. 10005196, FAAH Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit, Cayman Chemical, MI, USA). FAAH hydrolyzes 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC)-arachidonoyl amide, releasing AMC as a fluorescent product measured by VICTORX4TM fluorometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) with excitation wavelength of 355 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm. The amount of fluorescence generated by the FAAH enzyme was considered as 100% activity (control). Each probiotic lysate was mixed in a 96-well black plate with assay buffer and FAAH. The reaction was initiated by adding the substrate solution to a final volume of 200 µL, followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min. FAAH enzyme inhibitory assay was evaluated using 100% initial activity and calculated with the following equation:

% inhibition = [(corrected 100% initial activity – corrected inhibitor activity)/corrected 100% initial activity] × 100

where corrected 100% initial activity and corrected inhibitor activity were calculated by subtracting the average absorbance of the background wells from the absorbance values of the 100% initial activity and the inhibitor wells. FAAH inhibitor, JZL195 [47] (provided by the kit), was added to the reaction mix at the final concentration of 1 µM, as suggested by the manufacturer’s instructions.

The influence of the bacterial strains on MAGL activity was evaluated using an in vitro colorimetric assay kit (No. 705192, Cayman’s Monoacylglycerol Lipase Inhibitor Screening Assay Kit). MAGL hydrolyzes 4-nitrophenylacetate, releasing a yellow product, 4-nitrophenol. The absorbance was detected at 405 nm by a spectrophotometer (Eppendorf). The levels of absorbance measured in the presence of MAGL enzyme were considered as 100% activity (control). Each probiotic lysate was mixed in a 96-well plate with assay buffer and MAGL for 15 min. Afterward, the reaction was initiated by adding the substrate solution to a final volume of 180 µL, followed by incubation at 37°C for 10 min. MAGL enzyme inhibitory assay was evaluated using 100% initial activity and calculated with the following equation:

% inhibition = [(corrected 100% initial activity – corrected inhibitor activity)/corrected 100% initial activity] × 100

where corrected 100% initial activity and corrected inhibitor activity were calculated by subtracting the average absorbance of the background wells from the absorbance values of the 100% initial activity and the inhibitor wells. MAGL inhibitor, JZL195 [47], included in the kit, was added to the reaction mix at the final concentration of 4.4 µM, as suggested by the manufacturer’s instructions.

The spontaneously immortalized human keratinocyte HaCaT cell line, acquired from Cell Lines Service GmbH (Eppelheim, Germany), was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (NO. ECS0180L), 2 mM L-glutamine (NO. ECB3000D), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (NO. ECB3001D, Euro Clone, West York, UK). Culture conditions were kept constant at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. The cell cultures were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination (N-GARDE Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit, BioCat, Heidelberg, Germany; EMK090020-EUC). The cells used have been verified by STR analysis and have been confirmed to be free of any issues. To evaluate the effect of the bacterial lysates on cell MAGL and FAAH activity, cells were plated at 18,000 cells/cm2 in a 12-well plate. After 24 h of cell growth, the medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS and incubated for 24 h. HaCaT cells were treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli O111:B4 (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a concentration of 5 µg/mL, in the presence or absence of bacterial lysate at 25, 50, 100, or 200 µg protein/mL, using DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS. After 24 h, cells from each treatment condition were collected, centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min, and then stored at –80°C.

All concentrations of the bacterial lysates showed no significant impact on cell viability compared to untreated cells, with cell viability remaining above 90% in all experimental conditions.

The activity of FAAH in HaCaT cells was assessed using a commercially available FAAH Activity Assay Kit (Fluorometric) (Item No. ab252895, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, after treatment, the cells were lysed and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. FAAH activity was measured by detecting the fluorescent metabolite, AMC, which is generated by the cleavage of a non-fluorescent substrate. Fluorescent signals were recorded using a VICTORX4TM fluorometer in kinetic mode for 60 min, with excitation and emission filters set to 360 and 465 nm, respectively. The values obtained were interpolated using a standard curve created from known concentrations of the fluorescent metabolite. Data were normalized for total protein content, as determined by the DC Protein Assay (BioRad), and expressed as units of FAAH activity/mg protein. The kit also includes a specific inhibitor that can be utilized to account for potential non-specific background signals in unknown samples.

The activity of MAGL in HaCaT cells was assessed using a commercially available MAGL Activity Assay Kit (Fluorometric) (Item No. ab273326, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, after treatment, the cells were lysed and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min. MAGL activity was evaluated by measuring the fluorescent metabolite umbelliferon, which is generated by the cleavage of a fluorescent substrate. The fluorescent signal was measured by a VICTORX4TM fluorometer with excitation and emission filters set to 360 and 460 nm, respectively. Measurements were taken in kinetic mode for 60 min. The values were interpolated using a standard curve from known concentrations of the fluorescent metabolite. The data were normalized for total protein content, which was evaluated using a DC Protein Assay (BioRad), and were expressed as units of MAGL activity/mg protein. The kit includes a specific inhibitor that can be used to account for potential non-specific background in unknown samples.

All data were assessed using Prism version 6.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For the comparison of mean values between groups, one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, was used. Data were expressed as mean ± SD as specified in the figure legends. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

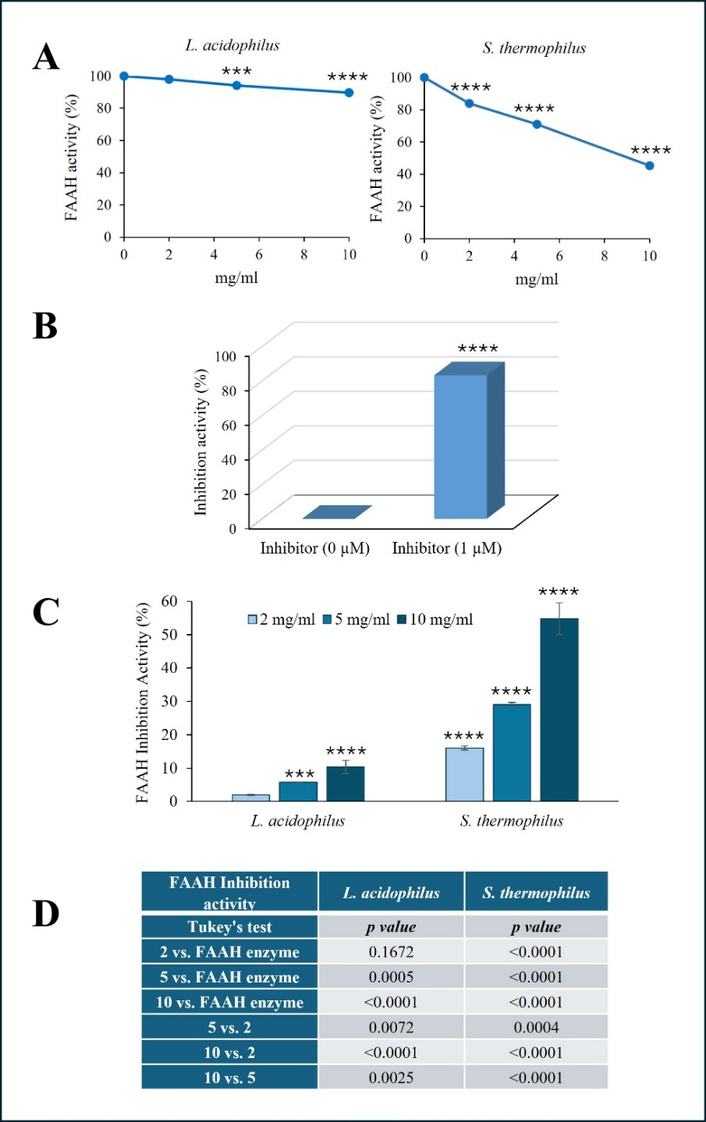

To evaluate the effect of the probiotic lysates on FAAH activity, we conducted several assessments using an in vitro fluorometric assay in a cell-free system. We tested the probiotic lysates derived from L. acidophilus CNCM I-5567 and S. thermophilus CNCM I-5570, at concentrations of 2, 5, or 10 mg/mL (weight/volume). Figure 1A displays the percentage of FAAH activity in the presence of probiotic lysates. FAAH activity was affected only slightly by L. acidophilus, while it appeared significantly and dose-dependently inhibited in the presence of S. thermophilus lysate. The specificity of the assay was verified using JZL195 [47], a specific FAAH inhibitor, which was used at 1 µM and completely abrogated the enzymatic activity under our experimental conditions (Figure 1B).

Effect of probiotic lysates on FAAH activity. The activity of human recombinant FAAH was evaluated in the presence of increasing concentrations of L. acidophilus and S. thermophilus lysates (2, 5, or 10 mg/mL) using an in vitro fluorometric assay kit and expressed as a percentage of enzymatic activity (A). The effect of FAAH inhibitor JZL195, used at 1 µM, on enzymatic activity is expressed as a percentage of inhibition and shown in (B). The % inhibition level of FAAH activity evaluated in the presence of probiotic lysates was reported in (C). P values for FAAH inhibition activity obtained by comparing probiotic lysate groups vs. each other and vs. enzyme alone, using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, are reported in (D). The results, expressed as the mean ± SD, are representative of one of three separate experiments in triplicate. SD < 10% of the mean values are omitted for clarity. (***P ≤ 0.0005; ****P < 0.0001 vs. enzyme alone). FAAH: fatty acid amide hydrolase.

The effect of probiotic lysates on FAAH activity was also expressed as % FAAH inhibition activity (Figure 1C). In the presence of S. thermophilus, the enzymatic activity of FAAH was inhibited by approximately 20% at the lowest concentration and exceeded 50% inhibition at the highest dose. On the contrary, under the experimental conditions used, L. acidophilus appeared to have a slight influence on FAAH activity, even at the highest concentrations, reaching a maximum inhibition of approximately 5% and 10% at a concentration of 5 and 10 mg/mL, respectively. The P values from the statistical analysis comparing groups, shown in Figure 1C, are listed in panel D (Figure 1D). Overall, we can conclude that L. acidophilus exhibited a slight, yet statistically significant, ability to inhibit FAAH activity at concentrations of 5 and 10 mg/mL. On the other hand, S. thermophilus demonstrated a significant and remarkable inhibitory effect even at lower concentrations.

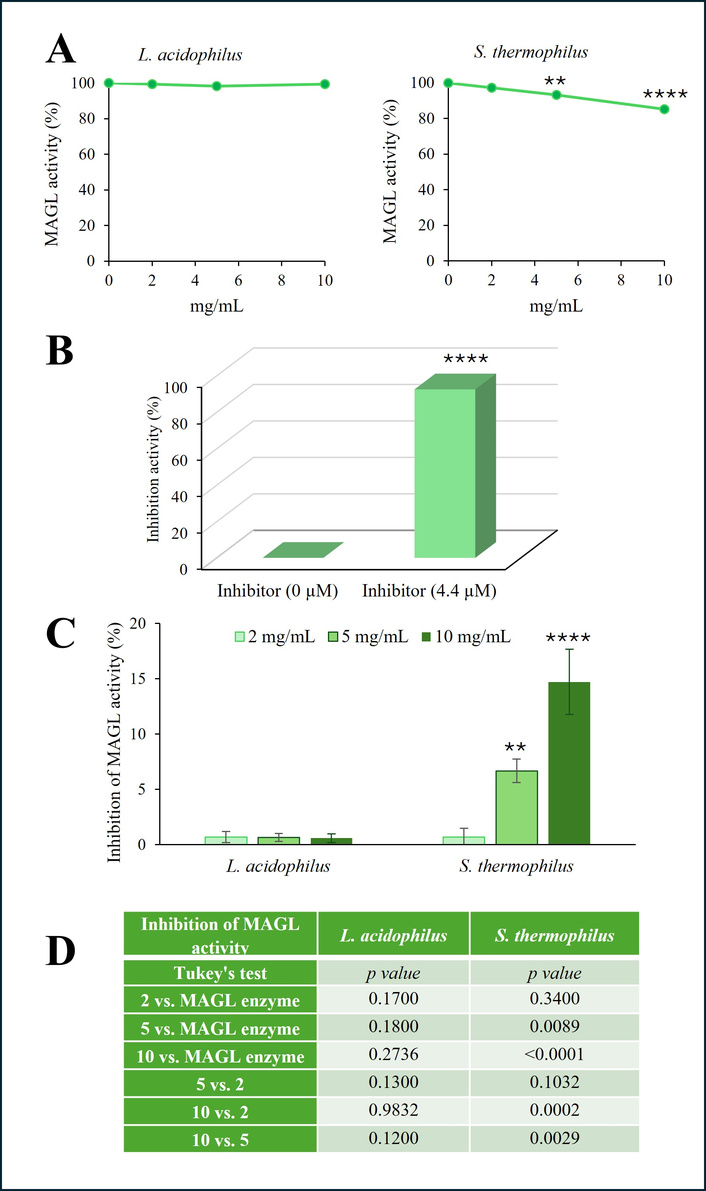

To investigate whether probiotic lysates inhibit MAGL activity, we employed an in vitro colorimetric assay in a cell-free system. The effect of L. acidophilus and S. thermophilus lysates at the concentrations of 2, 5, or 10 mg/mL is shown in Figure 2 and expressed as % MAGL activity (Figure 2A). S. thermophilus demonstrated an inhibitory effect on MAGL enzymatic activity, although it appeared less relevant than its inhibition on FAAH. The inhibition became statistically significant at the concentration of 5 mg/mL and continued to increase further at 10 mg/mL. To ensure the specificity of our analysis, we used a specific MAGL inhibitor. As depicted in Figure 2B, the presence of JZL195 [47], a MAGL inhibitor at a concentration of 4.4 µM, completely abrogated MAGL enzymatic activity. The results, shown in Figure 2C, indicate the % inhibition of MAGL activity in the presence of probiotics. The inhibitory activity of S. thermophilus was found to be statistically significant at both 5 and 10 mg/mL, though it did not exceed, averagely 7% and 15%, respectively. The table in panel D lists the P values for MAGL inhibition activity obtained by comparing the mean values between groups (Figure 2D). These results suggest that L. acidophilus did not significantly influence MAGL activity at the tested concentrations. Conversely, MAGL was inhibited in the presence of S. thermophilus lysate at 5 and 10 mg/mL. Although the effect on MAGL appeared statistically significant, MAGL was less sensitive than FAAH to the inhibitory action of S. thermophilus.

Effect of probiotic lysates on MAGL activity. The activity of human recombinant MAGL was evaluated in the presence of increasing concentrations of L. acidophilus and S. thermophilus lysates (2, 5, or 10 mg/mL) using an in vitro colorimetric assay kit and expressed as enzymatic activity % (A). The effect of MAGL inhibitor JZL195, used at 4.4 µM, on enzymatic activity is expressed as a percentage of inhibition and shown in (B). The % inhibition level of MAGL activity evaluated in the presence of probiotic lysates is reported in (C). P values for MAGL inhibition activity obtained by comparing treatment probiotic lysate groups vs. each other and enzyme alone, using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, are reported in (D). The results, expressed as the mean ± SD, are representative of one of three separate experiments performed in triplicate. SD < 10% of the mean values are omitted for clarity (**P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 vs. enzyme alone). MAGL: monoacylglycerol lipase.

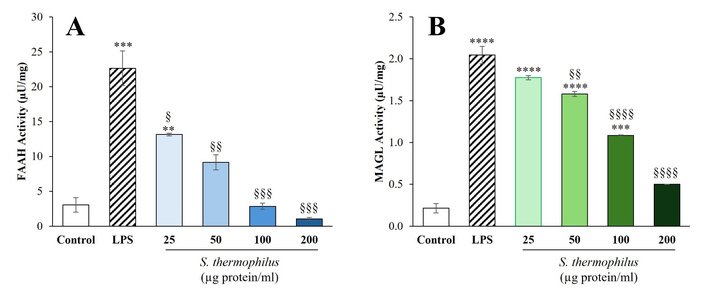

The ability of S. thermophilus to inhibit the enzymatic activity of FAAH and MAGL prompted us to verify whether probiotic lysate could exert this effect at the cellular level as well. To achieve this, we used an experimental model involving inflamed human keratinocytes, following the methodology proposed in previous studies [48, 49]. Specifically, HaCaT cells were treated with LPS (5 μg/mL) for 24 h, either in the presence or absence of bacterial lysate at various concentrations. Following this treatment, we measured the enzymatic activity of FAAH and MAGL in the cell extracts.

As expected, LPS treatment significantly increased the levels of FAAH and MAGL activity in HaCaT cells compared to untreated controls (P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001, respectively) (Figure 3). The addition of S. thermophilus lysate alone to the cell cultures, even at the highest concentrations, did not affect the baseline activity of FAAH and MAGL (not significant vs. control; results not shown). Notably, the presence of probiotic lysate in the culture for 24 h resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of both FAAH and MAGL activity.

Effect of S. thermophilus lysate on activity of eCB-degrading enzymes in HaCaT cells: (A) FAAH and (B) MAGL. HaCaT cells were incubated for 24 h with LPS at a concentration of 5 μg/mL, either with or without probiotic lysate at the specified concentrations. Enzymatic assays were performed using cell extracts, as detailed in the Materials and methods section. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM from two independent experiments in triplicate. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, with significance levels indicated as follows: **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared to control; §P < 0.05, §§P < 0.01, §§§P < 0.001, §§§§P < 0.0001 compared to LPS. eCB: endocannabinoid; FAAH: fatty acid amide hydrolase; MAGL: monoacylglycerol lipase; LPS: lipopolysaccharide.

In detail, as shown in Figure 3A, treatment with S. thermophilus lysate led to a relevant and dose-dependent inhibition of FAAH enzyme activity in the inflammatory model of LPS-stimulated HaCaT cells, which was evident and statistically significant at the concentration of 25 μg protein/mL (P < 0.05 vs. LPS). As the concentration of the probiotic lysate increased, the inhibitory effect on FAAH activity intensified significantly and, in a dose-dependent manner. Importantly, FAAH enzymatic activity in HaCaT treated with S. thermophilus at concentrations of 50 μg protein/mL or higher was not significantly different from that of the untreated control.

Regarding the effect on MAGL in LPS-stimulated HaCaT cells, a dose-dependent inhibition of enzyme activity was also observed, with statistically significant reductions at concentrations of probiotic lysate of 50 μg protein/mL or higher. Notably, after treatment with S. thermophilus lysate at a concentration of 200 μg protein/mL, the activity of MAGL in LPS-stimulated HaCaT cells was not significantly different from that of untreated control cells.

In this study, we present evidence that the lactic acid bacterium S. thermophilus can directly inhibit two crucial enzymes involved in the degradation of eCB: FAAH and MAGL. To our knowledge, these preliminary results provide the first evidence of a probiotic lysate’s ability to directly inhibit enzymes that degrade eCB.

Notably, the probiotic lysate has also demonstrated this inhibitory effect at the cellular level. Specifically, when HaCaT cells were treated with the inflammatory stimulus LPS for 24 h in the presence of S. thermophilus lysate, the enzymatic activity of FAAH and MAGL was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner. Collectively, these findings suggest a novel mechanism by which this probiotic may positively influence skin physiology by modulating the ECS. In a broader perspective, it is essential not to overlook that the probiotics are widely recognized as microorganisms with immunomodulatory properties and a positive impact on health [50].

The immunomodulatory activity considered the main beneficial feature of probiotics can be mediated through multiple mechanisms involving the production of several molecules such as peptides, bacterial DNA, short chain fatty acids, and components of microbial membrane [51] as well as the interaction between probiotic surface proteins and molecules with immune cells (T and B cells, monocytes, dendritic cells, intestinal epithelial cells) [52]. The probiotic-immune cell interactions may yield a variety of outcomes, depending on the context, including an improvement in intestinal barrier function associated with the induction of anti-inflammatory cytokine expression, recruitment of different immune cells, and regulation of several signaling pathways involved in the mucosal and systemic immune response, as well as competitive exclusion of pathogens [53].

The proposed approach, which aims to increase cannabinoid levels by reducing their degradation, offers an alternative to the common use of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-like compounds [54]. In general, maintaining adequate levels of cannabinoids is crucial for the proper functioning of the ECS, which plays a key role in preserving homeostasis by regulating various bodily processes, including immune, reproductive, neurological, and metabolic functions.

Previous research clearly documented that the topical application of S. thermophilus enhances the production of endogenous epidermal ceramide due to its intrinsic sphingomyelinase activity [8, 18, 19]. Ceramides are essential lipid components of the stratum corneum, which play a critical role in maintaining skin barrier integrity, hydration, and protection against irritants and pathogens [55]. A deficiency in ceramide levels is commonly observed in various dermatological conditions, including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and eczema, as well as in individuals with sensitive or compromised skin barriers [56, 57].

In addition to the previously established activity on skin ceramide levels, our study now identifies a novel complementary action by S. thermophilus, namely the inhibition of FAAH and MAGL, and subsequent potential elevation of local eCB concentrations, such as AEA and 2-AG. eCB, acting primarily through cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2, have been widely recognized for their roles in modulating skin inflammatory responses, synthesizing epidermal lipid, keratinocyte differentiation, and influencing pain perception [33, 36, 38].

The eCB, as well as the phyto- and synthetic cannabinoids, exert an important anti-inflammatory effect by interacting with their respective receptors, which are coupled to the Gi/o family of G-proteins. The signal transduction pathway, when triggered primarily by the CB2 receptor, which is considered as a regulator of inflammation [58], led to reduced adenylyl cyclase activity and, consequently, decreased cAMP levels, with consequent lower protein kinase A (PKA) activity and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation that is responsible for the expression of pro-inflammatory genes through transcription factors NF-κB and CREB [59]. In this way, cannabinoids can modulate inflammatory signaling, with consequent reductions in the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis, and increases in T-regulatory cells [54]. Several publications have reported the action of phytocannabinoids in skin inflammation by downregulating pro-inflammatory genes and inhibiting NF-κB activity [60–63].

The combined integration of these two distinct yet complementary mechanisms, direct elevation of ceramides and indirect modulation of eCB signaling, may provide unique and enhanced therapeutic benefits. Moreover, it is essential to consider that AEA can also exert its effects by interacting with selective membrane lipids, such as cholesterol and ceramides, independently of receptor mechanisms. Notably, findings show that when AEA binds to ceramide derived from sphingomyelinase activity, the molecular complex is stable and efficient thanks to the ability of ceramide to improve the stability of AEA, thereby preserving it from enzymatic degradation. In particular, its polar head group is completely hidden by ceramide, making the AEA-ceramide membrane complex inaccessible to FAAH [64, 65]. Moreover, research indicates that the simultaneous presence of AEA and ceramides delays ceramide metabolism, likely due to the high level of hydration of the AEA/ceramide complex, which limits the accessibility of ceramide to the degradative enzyme ceramidase. Both molecular mechanisms can block their respective degradation pathways, suggesting that each of these lipids mutually inhibits the catabolism of the other, thus leading to their stabilization in the plasma membrane and protection from enzymatic hydrolysis [64–66]. Based on this evidence, we hypothesize that the potential elevation of AEA caused by FAAH inhibition could have the ability to maintain epidermal ceramides at high levels and, consequently, better barrier function beyond what is achieved by sphingomyelinase activity alone. Additionally, the anti-inflammatory and antipruritic properties associated with eCB could significantly reduce the inflammatory symptoms often linked to compromised skin barriers [38].

In a future clinical perspective that needs to be appropriately confirmed by in vivo studies, combining these two beneficial mechanisms of action in a single probiotic-based topical formulation may open promising therapeutic pathways for managing chronic inflammatory skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, eczema, psoriasis, or neuropathic cutaneous disorders. In this regard, our team has provided clinical evidence on the efficacy of a cream containing S. thermophilus [17].

Such a dual approach could offer potential mechanisms that need to be supported to reduce dependence on corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents, thereby minimizing adverse effects and improving patient adherence to topical treatments. It is known that FAAH/MAGL inhibition by reversible and irreversible inhibitors may have off-target effects. For instance, data from the literature reported that the irreversible inhibitor JZL184 resulted in unwanted central nervous system (CNS)-mediated side effects such as pharmacological tolerance, physical dependence, impaired synaptic plasticity, and CB1 receptor desensitization in the nervous system in rodents [67]. Moreover, the FAAH inhibitor BIA 10-2474, which acts on various lipases, can alter the lipid networks in human cortical neurons, leading to subsequent metabolic dysregulation in the nervous system [68].

Nonetheless, given the preliminary nature of these results, several important considerations and limitations must be acknowledged. While we have evidence of the ability of S. thermophilus to enhance ceramide levels either in cellular models or in humans [8, 17–19], the findings presented here are based exclusively on in vitro tests on eCB-degrading enzymes, as well as on the HaCAT cell line. Studies to explore the effects of S. thermophilus on eCB-degrading enzymes are planned using 3D skin models, considered a suitable alternative to animal models in industrial applications and experimental research, as they provide a more accurate representation of the in vivo environment [69]. Additionally, through in vivo studies, detailed skin lipidomic analyses will be performed using advanced technologies, including measurements of eCB levels [70, 71], before and after treatment with an S. thermophilus-based topical formulation.

Our study supports the ability of S. thermophilus to positively impact skin health by inhibiting eCB-degrading enzymes, in addition to increasing the production of endogenous ceramide. This dual-action mechanism is promising as a novel approach to treating skin disorders associated with ceramide deficiency, barrier dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and discomfort. In addition, we would like to emphasize the safety of the proposed probiotic, generally recognized as a safe (GRAS) species [72], as also evidenced by the absence of side effects on in vivo studies [8, 17–19]. In conclusion, this study contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the immunomodulatory role of probiotics. By demonstrating the ability of S. thermophilus to inhibit FAAH and MAGL, enzymes involved in regulating inflammatory mediators, our findings suggest a novel anti-inflammatory mechanism that may be relevant for treating immune-mediated skin disorders.

2-AG: 2-arachidonoylglycerol

AEA: N-arachidonoylethanolamine

AMC: 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

eCBs: endocannabinoids

ECS: endocannabinoid system

FAAH: fatty acid amide hydrolase

FBS: fetal bovine serum

LPS: lipopolysaccharide

MAGL: monoacylglycerol lipase

NAEs: N-acylethanolamines

SA: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. ED: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. FL: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. PP: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. FRA: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. ST: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. MGC: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. BC: Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This research received no external funding.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1326

Download: 14

Times Cited: 0

Rucha A. Kelkar ... Giustino Varrassi

Marco Cascella ... The TRIAL Group

Mariateresa Giglio ... Filomena Puntillo

Antonella Ciaramella, Giancarlo Carli