Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 162-8601, Japan

Affiliation:

2Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife 220282, Nigeria

Email: taiyelabola@oauife.edu.ng

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8283-1243

Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 162-8601, Japan

Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 162-8601, Japan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9566-0674

Affiliation:

3Department of Chemistry, Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University, Makurdi 970001, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8389-6786

Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo 162-8601, Japan

Email: akitsu2@rs.tus.ac.jp

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4410-4912

Explor Drug Sci. 2025;3:1008137 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2025.1008137

Received: September 29, 2025 Accepted: November 27, 2025 Published: December 15, 2025

Academic Editor: Prasat Kittakoop, Chulabhorn Graduate Institute, Thailand

Aim: One of the causes of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the structural change and aggregation of target proteins due to the binding of metal ions. In this study, we investigated where copper(II) ions bound to the protein egg white lysozyme crystals in a hydrophilic buffer solution after ions were synthesized from an amino acid Schiff base copper(II) complex with a hydrophobic azobenzene group.

Methods: X-ray crystallographic studies of the complexes and egg white lysozyme were then studied. Molecular docking studies for the binding of copper(II) ion with egg white lysozyme were also carried out.

Results: The results suggest that the hydrophobicity of the introduced complex affected how deeply the resultant copper(II) ion penetrated into the protein. It has been revealed that when metal complexes are soaked into protein crystals, the metal complexes act as carriers, and metal ions tend to dissociate and bind to appropriate functional groups on certain specific residues of the protein. His15 and Glu35 were the more common binding residues of the protein that bound to the metal ion.

Conclusions: An anti-Irving-Williams behaviour was observed for the interaction of the copper(II) complex with the lysozyme. Docking studies revealed various potential binding sites of copper(II) ion with the lysozyme.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive decline and impairment in other intellectual abilities. It represents the leading cause of dementia worldwide. AD poses a significant and escalating public health challenge worldwide. AD imposes a significant societal and economic burden. Currently, millions of individuals live with AD. Mortality attributed to AD has also increased. In 2018 alone, deaths attributed to AD positioned it as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and fifth among older adults. This pervasive impact underscores the urgency for investigation into novel therapies targeting its multifactorial pathology [1–6].

The pathological hallmarks of AD include the accumulation of extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles formed by hyperphosphorylated tau protein. These aggregates disrupt neuronal function and synaptic communication, contributing to neurodegeneration. Oxidative stress is also a central feature in the progression of AD, exacerbating neuronal damage by promoting lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and DNA damage within vulnerable brain regions. This oxidative stress is often linked to metal ion imbalances in the brain, notably involving copper, zinc, iron, and calcium ions, which can catalyze the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). However, metal chelators are recently being investigated as inhibitors against repeat region tau aggregation and the formation of Aβ plaques, which are pathological hallmarks of AD.

In view of the foregoing, it is evident that the development of multifunctional agents will offer a holistic strategy against AD pathology. Given copper’s pivotal yet dualistic role in AD—as an essential metal and a catalyst for neurotoxicity—therapeutic strategies have focused on modulating copper-mediated toxicity while preserving physiological metal functions [6–8].

Reports have shown that copper(II) complexes hold significant promise as multifunctional agents in AD diagnosis and treatment. A bifunctional copper complex, [Cu(TE1PA-ONO)], was tested in vitro for detecting amyloid plaques. The copper complex, in comparison with anti-amyloid antibodies, on brain sections from AD patients showed similar distribution and density of amyloid plaques. Similarly, bis(thiosemicarbazonato) copper complexes have demonstrated efficacy in preclinical AD models with favorable pharmacokinetic profiles and CNS penetration. These multifaceted roles suggest copper complexes offer therapeutic benefits beyond metal chelation, including modulation of metal trafficking, inflammation, and synaptic repair [9–11].

The azobenzene functionalization in the azobenzene Schiff base offers a sophisticated platform to engineer multifunctional complexes with controlled and enhanced therapeutic efficacy [12]. Previous reports have shown the potential of azobenzene amino acid Schiff base copper(II) complexes to effectively decrease ROS levels, thereby suggesting their potential to reduce oxidative stress in neuronal cells [13]. Such findings underscore the potential of these complexes as neuroprotective agents targeting oxidative pathology in AD [14, 15]. These complexes have demonstrated the ability to conjugate with proteins such as lysozyme, potentially facilitating biological targeting and transport. These protein interactions can modulate copper transport within the brain, affecting copper availability and distribution critical in AD [4, 5, 16, 17].

Molecular docking and computational modeling play indispensable roles in guiding the design of Schiff base copper complexes with optimized binding affinities toward biological targets such as Aβ, enzymes, and nucleic acids. These in-silico approaches elucidate structure-activity relationships, predicting interaction modes and identifying modifications that enhance specificity and efficacy [18–20]. Integration of computational data with experimental validation accelerates the development process and refines ligand design. Such studies also provide insight into the potential off-target interactions and pharmacokinetic profiles before laborious in vivo testing [21, 22].

Previously, it has been revealed that when metal complexes are soaked into protein crystals, the metal complexes act as carriers, and metal ions tend to dissociate and bind to appropriate functional groups on certain specific residues of the protein (lysozyme) [23]. One hypothesis is that metal ions remain near the protein surface and bind when the hydrophobicity of the complex increases. The interaction with proteins of metal-based drugs plays a crucial role in their transport, mechanism, and activity. Information on these factors is quite useful in drug delivery designs. Therefore, to enrich the current repertoire of information on the binding of metal ions with proteins and the potential binding sites of the metal ions with the protein, this research work was undertaken. In this study, we investigated where copper(II) ions bound to the protein egg white lysozyme crystals in a hydrophilic buffer solution after ions were synthesized from an amino acid Schiff base copper(II) complex with a hydrophobic azobenzene group using X-ray crystallographic studies. In addition to this, molecular docking of the egg white lysozyme with copper(II) ion was also studied.

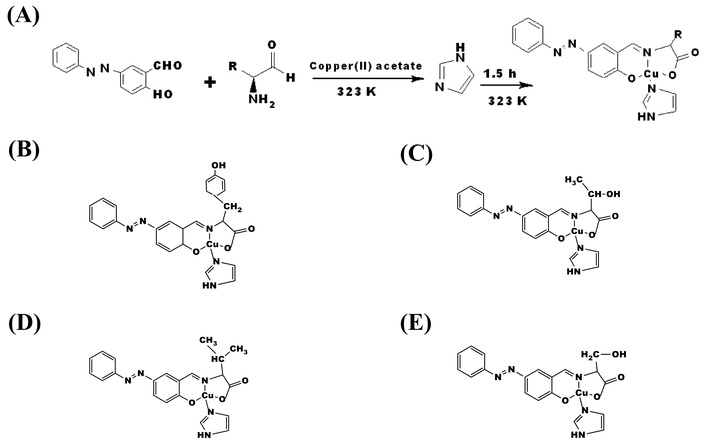

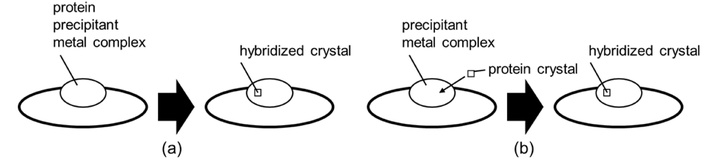

The binding of copper(II) ion with egg white lysozyme was studied. Four mixed ligand azobenzene Schiff base complexes were synthesized (Figure 1A) using established methods [24, 25]. The amino acids used were tyrosine, valine, threonine, and serine. Azobenzene-salicylaldehyde (226 mg, 1.00 mmol) and each amino acid (1.00 mmol) were dissolved in methanol (200 mL) and stirred at 313 K for 1.5 hours to give a red solution. Copper(II) acetate-hydrate (199 mg, 1.00 mmol) was added and stirred for 1 hour, and imidazole (68 mg, 1.0 mmol) was added and stirred for another hour to give each complex. The reaction solution was allowed to stand at 298 K for 4 days to obtain colored needle crystals (Figure 1A). Conventional spectra were then confirmed for the complexes obtained (Figures 1B–E). Complexes can be introduced into lysozyme by co-crystallization or immersion (Figure 2), and in this study, the soaking method was employed.

The azo-benzene amino acid Schiff base copper(II) complexes and the synthetic route of obtaining them. (A) Typical synthetic procedures for azo-amino acid Schiff base copper(II) complexes. Illustration of the structures of the complexes: (B) CuTyr; (C) CuThy; (D) CuVal; (E) CuSer. Structures were drawn using ChemDraw.

Schematic drawings of (a) the co-crystallization method, and (b) the soaking method.

Commercially available egg-white lysozyme (Wako-Fujifilm). Single crystals were grown, and the data collection of X-ray diffraction was carried out at High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK)-Photon Factory (PF) BL-5A as an automatic measurement.

Crystallized lysozyme was introduced into egg white lysozyme using the soaking method. Specifically, 2 μL of lysozyme solution (100 mg/mL lysozyme in acetate buffer) and precipitant solution (3–7% NaCl in acetate buffer) were dropped onto a cover glass. The cover glass was then placed over each well of a 24-well plate containing 200 μL of precipitant solution. The gap between the cover glass and the plate was sealed with grease, and the setup was left at room temperature for 3 to 12 hours to allow crystallization.

For soaking, 2 μL each of the precipitant solution and saturated complex solution (in acetate buffer) was dropped onto the cover glass. The crystallized lysozyme was placed in this solution, sealed in the same manner on the 24-well plate, and soaked at temperatures below 0°C for 2 to 12 hours.

The crystals obtained were then analyzed by protein crystallography at the KEK-PF to collect diffraction data. The data were analyzed using the molecular replacement method in the CCP4 software package, allowing determination of the protein structure and coordination of copper(II) ions.

Docking studies were then carried out using AutoDock and MIB2 to determine the potential binding sites of copper(II) ion with egg white lysozyme [26–28]. The ability of the copper(II) ion to bind with egg white lysozyme was investigated by molecular docking calculations. The egg white lysozymes were retrieved as crystal coordinates [Trametes versicolor laccase (protein data bank (PDB) ID: 1GYC)] from the protein database. The crystal structure was prepared for docking with the PyMol software, water molecules were removed, and the stripped egg white lysozyme was resaved in the pdb format. Egg white lysozyme (without associated water molecules) was loaded into the AutoDock tools, where polar hydrogens as well as Gasteiger charges were added. A grid box with dimensions (Angstrom units), x = 40, y = 40, z = 40, and center coordinates (0.375) was set up around the egg white lysozyme, which was saved in pdbqt format for the docking calculations. The egg white lysozyme was then loaded into the AutoDock program and used for the docking calculations. The parameter file for the AutoDock program was edited by including the parameters for the copper(II) ion before the docking run. The binding affinity estimates for different positions of the copper(II) ion with egg white lysozyme were retrieved after the docking calculations.

A similar process was carried out using the M1B2 program.

Predicting the formation of metal ion-residue coordination bonds is generally not easy, given steric and thermodynamic considerations. Previous reports have shown that when docking calculations of lysozyme and Schiff base copper complexes are predicted using computational chemistry simulations, Ala and His exhibit high docking scores. This time, an experimental research method was adopted in order to compare with the previous study. Hydrophobic amino acid-derivative Schiff base copper(II) complexes containing azo moieties were introduced into egg white lysozyme, and X-ray crystal structure analysis was used to confirm the binding of copper(II) ions and dissociable ligands in these copper(II) complexes.

The results for the binding sites of copper(II) with egg white lysozyme obtained from X-ray crystallographic studies are summarized and presented in Table 1. A total of twelve single crystals were grown and studied. Seven of these involved the use of the tyrosine derivative of the azo benzene Schiff in introducing the copper(II) ion into the lysozyme. Two crystals were obtained using the threonine and valine derivatives of the Schiff base, each and one from the serine functionalized derivative. The results obtained indicated that copper(II) ion bound with egg white lysozyme with varying coordination numbers ranging from one to four. This is not totally unexpected, as the probability of this exists due to the procedure employed for the introduction of the metal ion to the lysozyme. The complex comprising the tyrosine amino acid Schiff base derivative was the most hydrophobic of all four synthesized complexes. On its usage in introducing the copper(II) ion into egg white lysozyme, the copper(II) ion had the highest coordination number and the highest number of binding sites for two of the samples.

Summary of binding sites.

| Entry | Data set (complex used) | Coordination number | Binding sites (residues) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CuTyr | 4 | Arg21, Arg14, His15, Thr89, Leu129, Glu35 |

| 2 | CuTyr | 4 | Asn52, Ser72, Ser60, His15, Thr89, Leu129 |

| 3 | CuTyr | 2 | Asp101, Glu35 |

| 4 | CuTyr | 2 | Asp52, His15 |

| 5 | CuTyr | 3 | Thr69, Ser72, His15, Asp101 |

| 6 | CuTyr | 2 | Asp101, Ser91, Tyr53 |

| 7 | CuVal | 1 | Glu35 |

| 8 | CuVal | 2 | Glu35, His15 |

| 9 | CuTyr | 3 | Leu129, Cys64, Ser72, His15 |

| 10 | CuThr | 2 | Asp52, His15 |

| 11 | CuThr | 1 | Ser72, Asn65 |

| 12 | CuSer | 2 | Glu35, Arg14 |

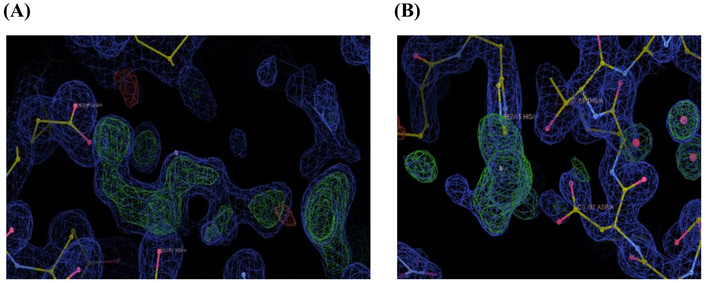

The result further revealed that in addition to the active site residues Asp52 and Glu35 of egg white lysozyme, the copper(II) ions were coordinated to Ser72, Ser91, Leu129, and His15. Electron density corresponding to the metal complex ligands was observed around His15 (Thr89), Glu35, and Asp52 together with copper(II) ions, while only copper(II) ions were observed bound to Asp101, Leu129, Ser91, and Ser72, without additional ligand density. For example, electron density was observed around the complex coordination of Glu35, while the ion binding (focused in this study) was around His15, Arg21, Arg14, and Thr89, as depicted in Figure 3.

Binding sites of copper(II) complex as a preliminary experiment (A) and copper(II) ion (B).

In previous experiments using less hydrophobic copper(II) Schiff base complexes derived from amino acids without azo groups, copper(II) ions were observed to penetrate into the interior of the protein, binding to residues such as Asn59, Ile58, Trp108, and Val109. For example, the Val-derivative Schiff base copper(II) complexes containing no azo moieties weakly bind to Arg114 of egg white lysozyme. Furthermore, in other copper(II) complexes, binding of the copper(II) ion and dissociable ligands to various residues was observed [23]. It has been shown that in some cases copper(II) ions dissociate from the ligand and are incorporated into hen egg lysozyme, and that dissociation of copper(II) ions from the ligand is facilitated by the dissolution of some copper(II) acetate into the protein crystal rather than the free copper(II) ions.

In contrast, in the present experiment, using a more hydrophobic Schiff base complex containing an azo group, copper(II) ions were more frequently observed binding at specific surface residues such as His15 and Asp101. Furthermore, it was confirmed that the copper(II) ion at Leu129 is deconjugated so that the electron density of the copper(II) ion is connected between the two lysozymes (Figure 3).

These results suggest that the hydrophobicity of the introduced complex affects how deeply it penetrates into the protein. A more hydrophobic complex may have limited access to the interior and preferentially binds to surface-exposed regions.

Furthermore, by introducing metal complexes with different hydrophobicity and molecular sizes, it may be possible to control the binding sites of copper(II) ions within the protein. This implies that while highly hydrophobic molecules may have strong transport capabilities and the potential to deliver copper atoms to various sites, more hydrophobic complexes may actually have lower delivery efficiency, instead showing selective transport only to sites with higher binding affinity.

Furthermore, comparison with docking calculations between egg white lysozyme and copper(II) ions predicted binding to the side chains of Ala11, Arg14, His15, Cys76, Asp87, Thr89, Asn93, and Lys96.

When compared with the side chains that actually bound in this experiment, copper(II) ions were confirmed to bind to His15, Arg14, and Thr89 as predicted. However, no electron density other than that of the protein was observed around the other side chains predicted to bind. In contrast, binding was frequently observed at Asp101, Leu129, and the active site residues Glu35 and Asp52, which had not been predicted to bind.

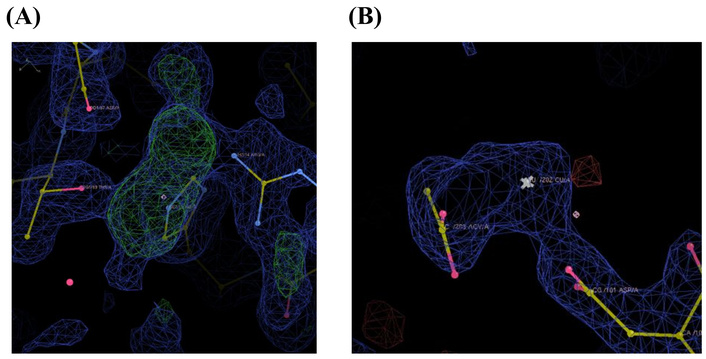

No correlation was found between the docking scores and the side chains that actually bound. For example, in His15 and Thr89, which had high docking scores and were also confirmed to bind, copper(II) ions were coordinated with multiple side chains and solvent molecules, as shown in the figures, likely leading to stable binding (Figure 4). On the other hand, for side chains where no binding was observed, despite having high docking scores, there were no other binding molecules nearby, resulting in unstable coordination with copper(II) ions and consequently no binding.

Copper(II) ion binding at (A) His15, Thr89, and Asp 87; (B) Asp101 and solvent coordinated to copper(II) ions.

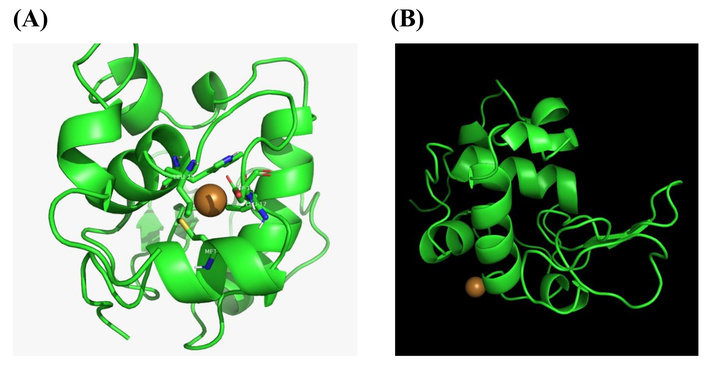

In an effort to further understand the binding of copper(II) ion with egg white lysozyme, in-silico studies were carried out on the binding of copper(II) with egg white lysozyme using molecular docking. Two programs were used: AutoDock and MIB2. The predicted binding sites are presented in Table 2, and the docking poses assumed are presented in Figure 5.

Binding predictions of copper(II) with egg white lysozyme.

| Binding site (MIB) | Binding site (AutoDock) | Binding site (MIB2) |

|---|---|---|

| Ala11, Arg14, His15, Cys76, Asp67, Thr89, Asn93, Lys96 | Met12, Leu17, Asp18, Leu25, Trp28 | Ala11, His15, Cys30, Asp87, Thr89, Ala90, Cys115, Asp119, Val120, Gln121 |

Structure of egg white lysozyme in the presence of copper(II) ion using (A) AutoDock and (B) MIB2.

This research provides an important foundation for future research into metal ions, metal complexes, and drug design aimed at combating AD, focusing on metal ion-protein conformations and interactions. The binding mechanism between certain metal ions and proteins is believed to depend on binding affinity values and strength limits. In particular, among first-transition series metal ions, the labile copper(II) ion also exhibits redox properties, which are relevant to controlling the coordination environment of copper(I)/(II) ions.

Beyond model systems, it will also be important to clarify the metal ion dissociation process and dissociation mechanism in vivo. Enzyme-catalyzed metal ion dissociation is a common phenomenon in living organisms. There are mechanisms by which specific enzymes specifically dissociate metal ions. Metal ion dissociation is also related to intracellular transport processes. If specific proteins or chelates are involved, interactions with these must also be taken into account. In order to achieve accurate metalation of proteins in vivo for their biological roles, cells have specifically evolved intracellular metal-sensing mechanisms to regulate their internal metal concentrations, which may deviate from the conventional pattern [29, 30]. The specificity of a protein binding site is predominantly influenced by the electronic characteristics of the amino acid residue within the primary coordination sphere arranged in a manner that suits the preferred coordination geometry of the metal ion [31, 32]. Additionally, the secondary coordination sphere and the overall structure of the protein matrix have been reported to play crucial roles in determining the metal selectivity of a protein [31, 33].

As methods for introducing ligands (metal complexes or organic molecules rather than metal ions) into crystals, co-crystallization and soaking methods are often considered, selected, or compared. In this hypothesis verification, the soaking method was suitable for the purpose, but co-crystallization, which is likely to be close to that in the living body, may be able to introduce metals deep enough that the soaking method cannot. However, the co-crystallization method has the disadvantage of requiring a re-exploration of crystallization methods [34].

The results obtained from the crystallographic studies indicated that the binding of copper(II) with egg white lysozyme exhibited anti-Irving-Williams behaviour. The Irving-Williams series describes the standard order of coordination stability for transition metal ions: Mn2+ < Fe2+ < Co2+ < Ni2+ < Cu2+ > Zn2+ [34, 35]. It is known that the metal-binding affinities of biological proteins largely follow this series. Where this expected trend is violated, such as copper(II) binding demonstrating lower affinity or stability compared to other metals in the series, it is referred to as anti-Irving-Williams behavior. In the context of copper(II) binding with egg white lysozyme, the canonical Irving-Williams trend would predict strong binding affinity due to the copper(II) ion’s typically high complex stability. However, an anti-Irving-Williams behavior was observed in this study, and this can be accounted for by the unique coordination environment and protein structural constraints affecting copper coordination. Copper(II) prefers a distorted octahedral geometry, differing from the tetrahedral coordination favored by zinc(II). It is suggested that the binding sites imposed geometrical constraints incompatible with copper(II) ion preferred coordination, leading to less favorable binding [36, 37]. Additionally, earlier studies have shown that the nature and spatial arrangement of potential binding residues determine metal binding affinity and selectivity [38]. In this study, the copper(II) bound with the nitrogen atoms of His15 and Glu35 the most. The positions of these residues indicate that interactions with the copper(II)ion may not be at an optimum, resulting in potentially lower stability or affinity. Long-range electrostatic effects modulating metal binding have been reported for other metalloproteins. This may apply to egg white lysozyme as well, potentially destabilizing copper(II) binding compared to expected Irving-Williams trends [36]. This therefore suggests that non-covalent interactions, electrostatics, and potential allosteric structural changes upon metal binding can influence the effective affinity of copper(II) to the lysozyme, leading to the anti-Irving-Williams behaviour. Kinetic barriers to forming particular binding modes or slow conformational changes in egg white lysozyme may also lead to apparent anti-Irving-Williams behaviour. Although hydrophobic ligands were used in the synthesis of the complexes, this may have assisted in the movement of the complexes to the protein. However, the ease of the displacement of the ligand, in addition to conformational changes as a result of the flexibility of the protein, may lead to apparent anti Irving-Williams behavior in the binding observed [39, 40].

Choi and Tezcan [41] designed a flexible protein dimer that selectively binds zinc(II) over copper(II) and other first-row transition metals, effectively displaying anti-Irving-Williams behavior. This selectivity was achieved through a unique trinuclear zinc coordination motif involving histidine and glutamate residues arranged in a tetrahedral geometry, leveraging protein flexibility to counter the usual Irving-Williams preference for copper(II) [40, 41]. This, therefore, presents a pathway to achieve selective binding of metals like zinc(II) over copper(II) through precise coordination geometry and structural flexibility. This knowledge can inform the modification or exploitation of egg white lysozyme metal-binding sites for similar selective functions. Therefore, considering application to Alzheimer’s model systems, it is expected that a similar anti-Irving-Williams design can be introduced to amyloid beta and tau, leading to the development of complex protein complexes that selectively initialize the required metal while avoiding Cu2+-dependent toxicity [41, 42].

It should be noted, from the results obtained, that although complete dissociation of the ligands from the copper(II) ion occurred to give the free metal ion, fragments were also obtained. The fragments consist of copper(II) ion bound with some of the carrier ligands. Interestingly enough, these were also observed bound to the protein. This is typified by the tyrosine derivative of the azo benzene amino acid Schiff base complex (Table 1). Copper(II) ions were observed bound to residues His15, Arg21, Arg14, and Thr89 with a coordination number of four, in a tetrahedral fashion (Figure 3). Additionally, fragments from the complex were observed, bound to residue Glu35. This is consistent with a previous report by Ferraro and co-workers [43, 44]. They demonstrated the fact that complexes can lose their carrier ligand(s), forming fragments, before and upon interaction with egg white lysozyme. Further collaborating our findings is the fact that the fragments obtained by Ferraro and co-workers [44] also bound with Glu35 of egg white lysozyme. Based on the results obtained as well as those from earlier reports, it is proposed that the carrier ligands, in this case, the azo benzene amino acid Schiff bases and imidazole molecule, dissociated from the copper(II) ion in a stepwise fashion. The monodentate ligand, the imidazole molecule, is the first to dissociate. It is further suggested that this is dependent on the reactants, metal ion, carrier ligands, and the reaction conditions as well. Further studies are to be carried out in order to fully understand the mechanism of dissociation of the carrier ligands and their efficiency. These findings therefore serve as evidence corroborating the complete dissociation of the carrier ligands to obtain the free copper(II) ion for interaction with the protein.

Earlier workers have investigated metal complexes as promising therapeutic agents for AD. Copper is an essential trace element, and its homeostasis is related to the pathogenesis of AD. Therefore, copper complexes are considered to be potential therapeutic agents for AD [45]. Metal complexes and metal-protein attenuating compounds (MPACs) primarily work through several mechanisms, one of which is the inhibition of Aβ aggregation. They interfere with the binding of metal ions to the Aβ peptide, which prevents the formation of toxic oligomers and plaques. They also act by restoring metal homeostasis. Rather than simply removing metals, these compounds aim to redistribute and balance essential metal levels in different brain regions and cellular compartments, ensuring enough are available for normal function while preventing pathological accumulation [45]. Another reported mechanism of activity of copper(II) ion in the treatment of AD involves reducing oxidative stress, this is done by modulating metal-Aβ interactions, they decrease the production of ROS, which are responsible for significant neuronal damage in AD. They have also been reported to interfere with tau hyperphosphorylation [45]. Some complexes can also affect the phosphorylation of the tau protein, another hallmark of AD pathology. Zhang et al. [46] identified a new copper(II) binding peptide (S-A-Q-I-A-P-H, PCu) from the heptapeptide library displayed by phages and used it as a copper ligand. Subsequently, they found that PCu could chelate copper(II) ion and inhibit the Aβ aggregation induced by copper(II) ion in vitro. It also attenuated copper(II)-mediated oxidative stress in N2a-sw cells. In addition, PCu inhibited levels of the β-secreting enzymes BACE1 and sAPPβ, thereby inhibiting the production of Aβ aggregates [46]. Despite promising results in preclinical and early clinical studies, challenges have remained in the use of metal complexes for the treatment of AD. This includes ensuring the complexes can effectively cross the blood-brain barrier, selectively target the pathological metal ions without depleting essential metals, and avoid systemic toxicity. This has necessitated the need for developing multifunctional ligands that target several aspects of the disease simultaneously and have better safety profiles. In a similar vein to that obtained by Zhang and co-workers [46], we propose the selective binding of copper(II) ion with the lysozyme, in such a way that there is a balance in the coordinated metal ions and the non-coordinated metal ion. As such, it inhibits Aβ aggregation. The hydrophobicity of the carrier ligands may also assist in crossing the blood-brain barrier for utilization. On this basis, it is proposed that the hydrophobicity of the carrier ligand may be further exploited and investigated towards the ability of copper(II) in locating its target molecule, towards effective and efficient drug delivery potential.

The results for the molecular docking using AutoDock revealed binding affinities of copper(II) ion with the following residues: Met12, Leu17, Asp18, Leu25, and Trp28. Binding affinity was observed at Ala11, His15, Cys30, Asp87, Thr89, Ala90, Cys115, Asp119, Val120 and Gln121, using M1B2 program (Table 2). These results indicated that there was no correlation in the predicted binding sites of the protein for each of the programs used. This therefore corroborates the fact that metal selectivity with three-dimensional proteins may be challenging. As a result of the varied structural changes that such proteins undergo. However, a comparison with earlier reports obtained for the binding of copper(II) with egg white lysozyme using MIB indicated a correlation of two binding sites, His15 and Ala11. This may be accounted for based on the fact that the MIB2 program is an updated version of MIB. Interestingly enough, His15 was the residue to which copper bound with the most experimental evidence. This lends further credence that His15 residue was found at the surface and was readily available for binding with the copper(II) ion [26–28].

In conclusion, this study successfully demonstrated the binding sites of copper(II) ions for the tested systems. Aiming to clarify the essential characteristics of binding in metal-binding proteins, we have synthesized copper(II) complexes with various amino acid derivatives and explored metal complexes and ligands by focusing on the uptake of copper(II) ions into egg white lysozyme using the transport effect of the ligands. In an experimental study comparing Schiff base copper(II) complexes of derivatives with various amino acids, in which azobenzene was introduced in the hope of improving hydrophobicity, it was revealed that copper(II) ions dissociate from the ligand and bind to several specific sites (functional groups available for coordination) of lysozyme. However, no clear, consistent tendency could be determined from the differences in ligand properties, and further research is required to determine the properties of the metal ion carrier. Furthermore, the conformational changes of proteins induced by metal ions are limited to the coordination environment and do not necessarily indicate metal ion coordination on the protein surface, which increases intermolecular interactions. This suggests for the first time that the mechanism by which metal ions induce protein aggregation is likely to be protein-dependent.

AD: Alzheimer’s disease

Aβ: amyloid-β

KEK: High Energy Accelerator Research Organization

PF: Photon Factory

ROS: reactive oxygen species

This work was performed under the approval of the Photon Factory Program Advisory Committee (Proposal No. 2022G012 and No. 2024G024).

AO: Resources, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. TOA: Writing—review & editing. SA: Data curation. DN: Writing—review & editing. PDI: Writing—review & editing. TA: Supervision, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Project administration, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) KAKENHI [24K00912]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1008

Download: 34

Times Cited: 0