Affiliation:

1Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Akure 704, Nigeria

2Chemical and Food Engineering Department, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianopolis 88040-970, Brazil

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6127-5206

Affiliation:

1Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Akure 704, Nigeria

Email: dsajewole247@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-4332-0639

Explor Foods Foodomics. 2026;4:1010115 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eff.2026.1010115

Received: August 23, 2025 Accepted: January 22, 2026 Published: February 13, 2026

Academic Editor: José Pinela, National Institute of Agrarian and Veterinary Research, Portugal; Polytechnic Institute of Bragança, Portugal

Aim: Malabar chestnut seed from Nigeria is an underutilized seed in Africa that possesses different nutritional, functional, and medicinal characteristics. Nevertheless, there is no quality information on the antioxidant properties of the embryo, the whole seed, and the seed coat of the Pachira glabra. This research investigated the nutritional composition and antioxidant properties of the Malabar chestnut embryo (MCE), whole Malabar chestnut (WMC), and Malabar chestnut seed coat (MCSC).

Methods: The nuts were sorted, and the seed coat was separated from the embryo. This was processed to get the WMC, MCE, and MCSC flours, and they were analyzed for proximate composition, minerals, amino acid profiles, antinutrients, and antioxidant properties.

Results: The proximate composition (g/100 g) showed high protein and fat content, total ash (2.50–3.50), crude fiber (2.04–11.43), moisture (3.62–7.93), and carbohydrate (13.29–37.92). The results also showed higher deposition of minerals in the seed coat, with phosphorus (2.82–5.26) and potassium (2.77–4.90) being the most abundant. This indicates that the seed can be used as a supplement for these nutrients. Low lead content was recorded in all samples. The antinutritional compositions were relatively lower in the embryo compared to the seed coat and whole seed. Furthermore, the high ratio of essential amino acids to non-essential amino acids (0.63–0.87), particularly in MCE, positions the seed as a potential high-quality protein source. The antioxidant properties demonstrated a high scavenging power, with a viable level of total phenol (198.65–330.41) mg GAE/g, total flavonoid (30.74–86.49) mg QE/g, as well as ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) and DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl).

Conclusions: The seed coat and the embryo of the Malabar chestnut showed superior nutritional composition and antioxidant properties; therefore, they can be used for medicinal purposes and as an antioxidant in the management of chronic diet-based diseases.

Edible seeds are part of the human diet and contain important macronutrients and bioactive compounds responsible for promoting metabolic health. Intake has been linked to improved glycaemic regulation, cholesterol reduction, and blood pressure [1]. These medicinal effects are largely caused by plant secondary metabolites such as phenolic compounds, which exhibit high antioxidant activities that may inhibit oxidative stress and chronic disease threats [2–4]. Besides physiological benefits, antioxidants are also universally utilized in food technology for the preservation of foods owing to their capacity to inhibit lipid oxidation, hence enhancing product stability and shelf life [5].

Even though antioxidants are ubiquitous in fruits, vegetables, and beverages, nuts and seeds are an under-exploited but a potential source [6]. Being rich in nutrients and lipid content, they are good materials for making a functional food. Among them, chestnuts are nutritionally and economically significant in certain regions. Malabar chestnut (Pachira glabra) or “money plant” in Nigeria, is attracting attention due to its high concentration of sugars, minerals, lipids, and phenolic acids such as caffeic, ferulic, and 4-hydroxybenzoic acids, which have been reported to be responsible for its antioxidant activity [7, 8].

Malabar chestnut was reported to have positive effects in the management of cardiovascular and metabolic ailments due to its richness in phytochemical variety and activity [9]. It can be taken in raw, roasted, or processed form, depending on procedures that highly affect its nutritional as well as antioxidant activity. Akinyede et al. [10] reported that roasting significantly improved the protein and antioxidant levels, while Ayodele and Badejo [11] reported that germination and defatting significantly increased the nutritive value of the nut flour. The findings indicate the potential for nutrition-enhanced products and industrial mixtures of the nut.

Notwithstanding such inherent merits, the use of Malabar chestnut remains limited, particularly as its seed coat, which tends to be wasted during processing, is hardly researched scientifically. This underutilization results in the primary problem of nutrient wastage and a secondary problem of climatic instability. At a time when sustainable food systems and waste valorization are becoming of utmost importance, such fractions of underutilization deserve solid attention. Almond shells and other seed coats were identified as composition-rich by previous work and as value-added food products [12]. Thus, an investigation of Malabar chestnut seed fractions for their biochemical and antioxidant constituents could be a key towards sustainable exploitation of the resource and improved food security.

The present study, therefore, investigates the nutrient composition and antioxidant activity of the whole Malabar chestnut (WMC), Malabar chestnut (Pachira glabra) seed coat (MCSC), and embryo (MCE). The objective is to assess their potential for application as functional food ingredients, to promote greater utilization of the nut, and to increase waste minimization in a cleaner food processing environment.

Malabar chestnut samples were acquired from the Federal University of Technology, Akure (FUTA) community and authenticated at the Department of Crop, Soil, and Pest Management of the same institution with voucher number FUTACSP20/116. All solvents and reagents, obtained from various suppliers, were of the highest required purity and were sourced from a reputable chemical store in Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria.

Using the modification of the method described by Ajala and Taiwo [13], mature Malabar chestnut pods were collected and allowed to burst open, and the seeds were collected. The coat was separated from the embryo. Samples were collected and processed as follows: WMC, MCSC, and MCE, which were dried separately at 50°C for 24 h in a hot air oven. After drying, the samples were milled into powder form separately.

The proximate composition of the flour samples, including moisture content, crude fiber, crude fat, total ash, and crude protein, was determined using standard AOAC methods [14].

The mineral constituents of the samples were analyzed using the solution obtained by dry ashing the samples at 550°C and dissolving the ash in 50 mL of 10% HCl using deionized distilled water for the preparation. The minerals [magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), zinc (Zn), phosphorus (P), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), copper (Cu), and lead (Pb)] were analyzed using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer [14]. However, for both sodium and potassium, flame photometer (Sherwood Flame Photometer 410; Sherwood Scientific Ltd., Cambridge, UK) was used.

The method described by Wheeler and Ferrel [15] was used for the phytate content determination, and saponin was determined using the gravimetric method adopted by Adeleye et al. [16]. Alkaloid qualitative determination was done by the alkaline precipitation gravimetric method described by Harborne [17]. The oxalate content was determined following the procedure described by Day and Underwood [18]. For tannin determination, 0.2 g of each finely ground sample was weighed into four separate 50 mL sample bottles. Then, 10 mL of 70% aqueous acetone was added to each bottle, which was then properly covered. The bottles were placed in a water bath shaker and shaken for 2 h at 30°C. After shaking, each solution was centrifuged, and the supernatant was stored on ice. Next, 0.2 mL of each solution was pipetted into a test tube, and 0.8 mL of distilled water was added. Standard tannic acid solutions were prepared from a 0.5 mg/mL stock solution, and each solution was made up to 1 mL with distilled water. To both the samples and the standard solutions, 0.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was added, followed by 2.5 mL of 20% Na2CO3. The solutions were then vortexed and incubated for 40 min at room temperature. The absorbance of the solutions was measured at 725 nm against a reagent blank, and the tannin concentration was determined using a standard curve.

The method of Benzie and Devaki [19] was used in the determination of ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP). Total flavonoid content was determined using the method of Chang et al. [20]. DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities were determined using the methods described by Blois [21] and Re et al. [22], respectively. Fe2+ chelating activity was measured using a 2,2'-bipyridyl competition assay as outlined by Re et al. [22]. Total phenolic content (TPC) was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. For TPC analysis, 1 g of Malabar chestnut powder was extracted in 20 mL of distilled water and placed in a shaker for 4 h. The absorbance of the solution was measured at a wavelength of 765 nm using a Hewlett-Packard 8435 ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer. The analysis was performed in triplicate for the extract. A gallic acid standard solution (80–170 μg/mL) was used to create a calibration curve. The TPC was expressed as the milligrams gallic acid equivalent per g of extract (mg GAE/g).

The Malabar chestnut flour samples were digested using 6 mol/L HCl for 24 h [14]. The Beckman Amino Acid Analyzer (model 6300; Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, California, USA) was used to analyze amino acids using the cation exchange post-column ninhydrin derivatization process and sodium citrate buffers as step gradients. The data was estimated as grams of amino acid per 100 g of crude protein of the flour samples.

All results were reported as the means of three replicate analyses. The data obtained were subjected to one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) using SPSS version 16 to determine significant differences (p < 0.05). Differences between the means derived from the ANOVA were further analyzed using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT).

The proximate compositions of MCE, WMC, and MCSC are presented in Table 1. Moisture content varied significantly across samples (p < 0.05). Sample MCSC possesses a moisture content of 6.33%, which is 68% higher than that of MCE but 19% lower than that of WMC. The protein content of the samples ranges from 10.99% to 20.60%, with the seed coat being inferior to both sample MCE and WMC. Like the protein content of both MCE and WMC, there is no significant difference in the level of their carbohydrate content (p > 0.05), with values of 17.14% and 14.91%, respectively, both of which are significantly lower than that of the sample MCSC, with a value of 37.18%. The result also showed that the fat content of the embryo is 52.33%, while that of the seed coat and the whole seed were 18.67% and 43.33%, respectively. The result also shows that the value of total ash for samples MCSC, MCE, and WMC is 2.50%, 4.17%, and 3.50%, respectively. The energy level showed a strong, positive linear correlation with the level of crude fat, with values ranging from 360.71 to 621.93 kcal.

Proximate composition (g/100 g) of whole, embryo, and seed coat of Nigerian Malabar chestnut.

| Samples | Crude protein | Total ash | Crude fibre | Crude fat | Moisture | Carbohydrates | Energy (kcal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCSC | 10.99 ± 0.36b | 2.50 ± 0.00c | 24.33 ± 0.29a | 18.67 ± 0.58c | 6.33 ± 0.06b | 37.18 ± 0.74a | 360.71 |

| MCE | 20.60 ± 0.31a | 4.17 ± 0.29b | 2.00 ± 0.00c | 52.33 ± 0.58a | 3.76 ± 0.14c | 17.14 ± 1.13b | 621.93 |

| WMC | 20.24 ± 0.11a | 3.50 ± 0.00a | 10.17 ± 1.26b | 43.33 ± 0.58b | 7.85 ± 0.08a | 14.91 ± 1.62b | 530.57 |

Values represent the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Mean values followed by different superscripts within columns are significantly different according to Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (p < 0.05), represented with a–c. Repeated superscript letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). MCSC: Malabar chestnut seed coat; MCE: Malabar chestnut embryo; WMC: whole Malabar chestnut.

The mineral composition of WMC, MCE, and MCSC is presented in Table 2. The mineral concentration of the samples ranged from 0.01 to 5.29 mg/100 g across all the assessed minerals. In terms of the assessed minerals, the seed coat has the highest total mineral content of 18.38 mg/100 g for all reported minerals; meanwhile seed coat is attributed to a higher deposition and retention of the minerals [23]. The lead content is 0.01 mg/100 g in the embryo, but 0.02 mg/100 g in both the whole seed and the seed coat. Phosphorus is the most abundant mineral in the seed coat and the embryo, while potassium is the most abundant in the whole seed, with values 5.29 mg/100 g, 2.90 mg/100 g, and 4.88 mg/100 g, respectively.

Mineral composition (mg/100 g) of whole, embryo, and seed coat of Nigerian Malabar chestnut.

| Minerals/Samples | MCSC | MCE | WMC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorus | 5.29 ± 0.02a | 2.90 ± 0.02b | 2.84 ± 0.02c |

| Potassium | 4.47 ± 0.02b | 2.80 ± 0.02c | 4.88 ± 0.03a |

| Sodium | 2.55 ± 0.02b | 1.57 ± 0.02c | 3.07 ± 0.02a |

| Calcium | 2.18 ± 0.02a | 1.45 ± 0.02c | 1.64 ± 0.02b |

| Magnesium | 1.16 ± 0.02a | 1.13 ± 0.01b | 0.98 ± 0.02c |

| Iron | 1.88 ± 0.02a | 1.50 ± 0.02b | 0.85 ± 0.02c |

| Zinc | 0.46 ± 0.01a | 0.16 ± 0.01c | 0.32 ± 0.01b |

| Manganese | 0.26 ± 0.01b | 0.47 ± 0.01a | 0.09 ± 0.01c |

| Copper | 0.11 ± 0.01b | 0.10 ± 0.01c | 0.20 ± 0.01a |

| Lead | 0.02 ± 0.00a | 0.01 ± 0.00a | 0.02 ± 0.00a |

Values represent the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Mean values followed by different superscripts within columns are significantly different according to Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (p < 0.05), represented with a–c. Repeated superscript letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). MCSC: Malabar chestnut seed coat; MCE: Malabar chestnut embryo; WMC: whole Malabar chestnut.

Sodium ranged from 1.57 to 3.07 mg/100 g, with a minimum in the embryo and a maximum in the whole chestnut. Calcium levels varied across seed components, with the seed coat exhibiting the highest concentration at 2.18 mg/100 g. Magnesium was very uniform in all fractions. Iron content was highest in the coat (1.88 mg/100 g) and lowest in the whole seed (0.85 mg/100 g). Expectedly, manganese was most abundant in the embryo (0.47 mg/100 g) compared to the coat (0.26 mg/100 g) and entire seed (0.09 mg/100 g). Zinc levels were generally low but significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the coat (0.46 mg/100 g) than in the embryo (0.16 mg/100 g). Copper content was reasonably uniform (0.1–0.2 mg/100 g), with the whole chestnut a little higher.

Mineral ratios also provide another picture of the nutritional composition of the seed components (Table 3). The Na/K ratios < 1 for all the samples (0.57 in MCSC, 0.56 in MCE, and 0.63 in WMC) are desirably low. Ca/P ratios ranged from 0.41 to 0.58 for all the samples. The Zn/Cu ratios (1.6–4.18) were low.

Mineral ratio of the whole, embryo, and seed coat of Nigerian Malabar chestnut.

| Mineral ratio | MCSC | MCE | WMC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na/K | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.63 |

| K/Na | 1.75 | 1.79 | 1.59 |

| Ca/P | 0.41 | 0.5 | 0.58 |

| P/Ca | 2.43 | 2 | 1.72 |

| Ca/Mg | 1.88 | 1.28 | 1.67 |

| Mg/Ca | 0.53 | 0.78 | 0.6 |

| Fe/Zn | 4.09 | 9.38 | 2.66 |

| Zn/Cu | 4.18 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Fe/Cu | 17.09 | 15 | 4.25 |

| K/(Ca + Mg) | 1.34 | 1.09 | 1.86 |

MCSC: Malabar chestnut seed coat; MCE: Malabar chestnut embryo; WMC: whole Malabar chestnut.

The amino acid profile of samples MCSC, MCE, and WMC is given in Table 4. The total essential amino acids in the seed coat, embryo, and the whole seed of the Malabar chestnut are 19.90 g/100 g, 30.25 g/100 g, and 21.40 g/100 g, respectively. Of all the essential amino acids assessed, leucine has the highest value across the samples, with 4.70 g/100 g, 6.68 g/100 g, and 4.88 g/100 g for MCSC, MCE, and WMC, respectively. From the results, glutamic acid and arginine have the highest concentrations, at 12.89 g/100 g and 10.21 g/100 g, respectively. The tryptophan values of the seed are 0.62 g/100 g, 1.24 g/100 g, and 0.81 g/100 g for seed coat, embryo, and whole seed, respectively. The aspartic acid of the samples is significantly different (p ˂ 0.05). This is the same with every other amino acid across the samples, except histidine, where the values of the seed coat (1.11 g/100 g) and the whole seed (1.08 g/100 g) are statistically the same (p ˃ 0.05). The total non-essential amino acids are 22.96 g/100 g, 48.29 g/100 g, and 24.65 g/100 g for the seed coat, embryo, and the whole seed of the Malabar chestnut.

Amino acid profile (g/100 g) of whole, embryo, and seed coat of Nigerian Malabar chestnut.

| Amino acid | MCSC | MCE | WMC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Essential amino acids (EAA) | |||

| Leucine | 4.70 ± 0.02c | 6.68 ± 0.03a | 4.88 ± 0.02b |

| Lysine | 2.10 ± 0.02c | 2.95 ± 0.03a | 2.60 ± 0.02b |

| Isoleucine | 2.91 ± 0.03c | 4.37 ± 0.02a | 3.10 ± 0.02b |

| Phenylalanine | 2.99 ± 0.02c | 4.46 ± 0.03a | 2.64 ± 0.03b |

| Tryptophan | 0.62 ± 0.01c | 1.24 ± 0.02a | 0.81 ± 0.02b |

| Valine | 2.36 ± 0.02c | 3.60 ± 0.03a | 2.61 ± 0.02b |

| Methionine | 0.82 ± 0.02c | 2.38 ± 0.02a | 1.09 ± 0.02b |

| Histidine | 1.11 ± 0.02b | 2.09 ± 0.02a | 1.08 ± 0.02b |

| Threonine | 2.29 ± 0.01c | 2.52 ± 0.02b | 2.59 ± 0.02a |

| TEAA | 19.90 | 30.25 | 21.40 |

| Non-EAA | |||

| Tyrosine | 1.91 ± 0.02c | 3.08 ± 0.02a | 2.22 ± 0.02b |

| Cystine | 0.81 ± 0.02b | 3.08 ± 0.03a | 0.75 ± 0.02c |

| Alanine | 3.20 ± 0.02c | 4.08 ± 0.02a | 3.51 ± 0.02b |

| Glutamic acid | 5.27 ± 0.03c | 12.89 ± 0.02a | 5.88 ± 0.02b |

| Glycine | 2.01 ± 0.02c | 3.83 ± 0.02a | 2.31 ± 0.02b |

| Arginine | 3.29 ± 0.02b | 10.21 ± 0.03a | 3.04 ± 0.03c |

| Serine | 1.86 ± 0.02c | 3.28 ± 0.02a | 2.15 ± 0.02b |

| Aspartic acid | 4.61 ± 0.02c | 7.85 ± 0.03a | 4.79 ± 0.02b |

| TNEAA | 22.96 | 48.29 | 24.65 |

Values represent the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Mean values followed by different superscripts within columns are significantly different according to Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (p < 0.05), represented with a–c. Repeated superscript letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). MCSC: Malabar chestnut seed coat; MCE: Malabar chestnut embryo; WMC: whole Malabar chestnut; TEAA: total essential amino acids; TNEAA: total non-essential amino acids.

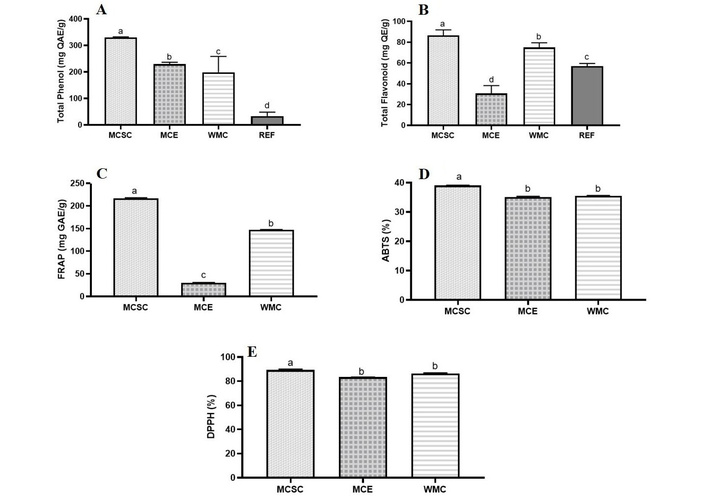

The results of the total phenol of the samples are presented in Figure 1A below. The results showed that the TPC of the samples was 330.41 mg GAE/g, 229.39 mg GAE/g, and 198.65 mg GAE/g for the seed coat, embryo, and whole seed, respectively. Despite the significant differences observed among the samples, all three samples exhibited higher phenolic contents than the standard reference (gallic acid). The total flavonoid content of the whole, embryo, and seed coat of Nigerian Malabar chestnut was presented in Figure 1B. The extracts were evaluated at concentrations ranging from 100 to 200 μg/mL, with the TFC varying accordingly, and the TFC ranged from 30.74 to 86.49 mg QE/g in the samples. The reducing power of the embryo, the whole seed, and the seed coat of the chestnut seed are shown in Figure 1C below. The FRAP assay tends to show the ability of a particular sample to undergo reduction processes. The reducing ability of the samples is 30.30 mg GAE/g, 147.48 mg GAE/g, and 216.84 mg GAE/g for the embryo, whole seed, and the seed coat, respectively. The result of the ABTS radical scavenging ability of chestnut extracts, as shown in Figure 1D, showed that the free radical scavenging ability of all chestnut extracts analyzed was 35.53%, 35.16%, and 39.05% for samples WMC, MCE, and MCSC, respectively. The result, according to Figure 1E, also shows that the sample MCSC (chestnut seed coat) exhibited a maximum DPPH scavenging ability of 89.26%, and the embryo exhibited a minimum of 83.37%, whereas that of the whole chestnut is 86.40%. Fe2+ chelation is presented in Table 5. The samples possess a high iron chelating ability ranging from 44.01 to 89.61% at different concentrations. The iron chelation decreased steadily in both MCSC and WMC at higher concentrations.

Antioxidant properties and activities. (A) Total phenol (mg GAE/g); (B) total flavonoid (mg QE/g); (C) ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) (mg GAE/g); (D) ABTS scavenging ability (%); (E) DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) of the whole, embryo, and seed coat of Nigerian Malabar chestnut. Each bar represents the mean of three replicates ± standard deviation. Mean values followed by different letters on each bar are significantly different according to Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (p < 0.05), represented with a–c. Repeated letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). MCSC: Malabar chestnut seed coat; MCE: Malabar chestnut embryo; WMC: whole Malabar chestnut.

Fe2+ chelation (%) of the whole, embryo, and seed coat of Nigerian Malabar chestnut.

| Concentration/Samples | 20 μg/mL | 40 μg/mL | 60 μg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCSC | 65.26 ± 2.32b | 44.01 ± 2.48c | 30.59 ± 8.23c |

| MCE | 81.55 ± 0.40a | 89.61 ± 4.63a | 75.94 ± 1.04a |

| WMC | 81.23 ± 0.80a | 63.82 ± 5.83b | 60.16 ± 5.83b |

Values represent the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Mean values followed by different superscripts within columns are significantly different according to Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (p < 0.05), represented with a–c. Repeated superscript letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). MCSC: Malabar chestnut seed coat; MCE: Malabar chestnut embryo; WMC: whole Malabar chestnut.

Table 6 shows some of the anti-nutritional properties of the whole, embryo, and seed coat of Nigerian Malabar chestnut. From the results, phytate concentrations for the embryo, whole seed, and seed coat are 0.56 g/100 g, 0.75 g/100 g, and 0.36 g/100 g, respectively. Tannin is 2.44 g/100 g, 5.22 g/100 g, and 3.66 g/100 g for MCE, WMC, and MCSC, respectively, while Saponin is 4.57 g/100 g, 5.91 g/100 g, and 3.95 g/100 g for embryo, seed coat, and whole seed, respectively. The oxalate content varied significantly at a 95% level of confidence, with values of 0.24 g/100 g, 0.74 g/100 g, and 1.27 g/100 g for the embryo, the whole seed, and the seed coat, respectively.

Antinutritional and phytochemical properties (g/100 g) of the whole, embryo, and seed coat of Nigerian Malabar chestnut.

| Parameters | MCE | WMC | MCSC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tannin | 2.44 ± 0.06c | 5.22 ± 0.02a | 3.66 ± 0.02b |

| Oxalate | 0.24 ± 0.02c | 0.74 ± 0.01b | 1.27 ± 0.01a |

| Phytate | 0.56 ± 0.02b | 0.75 ± 0.03a | 0.36 ± 0.01b |

| Saponin | 4.57 ± 0.20b | 5.91 ± 0.15a | 3.95 ± 0.16c |

| Alkaloids | 0.39 ± 0.02c | 0.54 ± 0.03b | 1.02 ± 0.01a |

Values represent the means of three replicates ± standard deviation. Mean values followed by different superscripts within columns are significantly different according to Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (p < 0.05), represented with a–c. Repeated superscript letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). MCSC: Malabar chestnut seed coat; MCE: Malabar chestnut embryo; WMC: whole Malabar chestnut.

Desirably, the low moisture content observed in all the samples is below the maximum moisture content of flour (15%) according to the FDA and USDA, which implies that all the samples have the potential to keep for long under favorable storage conditions. Significantly, the moisture content of all the samples is lower than the one (3.67–6.05%) reported by Alabi et al. [24] for sorghum ogi samples with the inclusion of ginger and garlic. The superiority of sample MCE and WMC over sample MCSC, in terms of protein content observed in the results could be linked to the fact that the embryo is one of the important sites for protein storage in cereals [25], indicating that the embryo can serve as a substitute source of protein, especially to induce enzymatic activities, with gene regulation in the body [26]. This observation supports earlier reports that seed coats primarily serve structural and protective roles, rather than acting as major nutrient reservoirs [27]. Meanwhile, the protein content of the samples could be improved by subjecting the seeds to germination and processing [10, 11]. This is further substantiated by the findings of Kamda et al. [28], who reported an increased protein content in yoghurt produced from germinated tiger nuts. The crude fat content of sample MCE and WMC falls in the range presented by Akinyede et al. [10] and Ayodele and Badejo [11]. The level of fat in sample MCE shows that a reasonable amount of oil can be extracted from the embryo using the hydraulic method of oil extraction, i.e. hydraulic press can be used to extract oil if the oil content is above 50% [29].

The carbohydrate level shows that other macronutrients relative to carbohydrates are lower in the seed coats compared to the embryo. This could also be linked to the fact that the level of crude fiber in the seed coat is higher than the rest of the sample, since the FDA [30] stated that the total carbohydrate count in food includes dietary fiber in the food material, even though they cannot be absorbed and do not contribute to the overall sugar level in the body.

The opposite trend between carbohydrate and fat contents suggests a natural balance in how energy is distributed within the seed, a pattern common in oil-rich crops. The remarkably high lipid level in MCE (52.33%) points to its promise as a good source of edible oil. It reflects the seed’s tendency to store energy in the form of triacylglycerols during development.

The higher fiber in MCSC indicates the presence of more structural carbohydrates and fiber-associated cell wall materials. Although these components may lower the digestible energy of the sample, they can provide valuable functional benefits such as improved gut health and glucose regulation. Since the FDA [30] includes dietary fiber in total carbohydrate estimation despite its low digestibility, the higher carbohydrate level observed in MCSC likely results from these non-digestible polysaccharides.

The potassium dominance of WMC corresponds with Alabi et al. [24] and Shakpo et al. [31], who recorded high levels of potassium compared to other minerals. Potassium plays a critical role in protein maintenance, controlled glucose uptake, and in nerve and muscle excitability control through offering osmotic equilibrium in body fluids [32]. Such physiological benefits may make the whole seed particularly useful in ensuring electrolyte stability as well as muscle function.

Phosphorus and potassium contents in each fraction, however, were much lower than those determined by Farinde et al. [33] for Lima beans, likely due to differences in species and seed physiology. Phosphorus is responsible for bone formation, protein synthesis, and cell regulation of energy, and dynamic equilibrium of the gut, kidney, and other tissues [34]. The relatively higher phosphorus content in the seed coat, otherwise lost during processing, suggests its potential utilization as a feed supplement in human and animal nutrition.

Lead is a potentially toxic element, and its levels were very low across all fractions, far below the maximum permissible limit of 0.1 mg/100 g set by Codex Alimentarius [35]. This confirms the safety of Malabar chestnut seeds for human consumption in terms of heavy metals. Iron deposition within the seed coat is reflective of its antioxidant and protective roles against oxidative stress and microbial infection. Its occurrence also signifies potential use in the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia, though bioavailability might be interrupted by antinutritional factors such as phytates [36].

Copper and zinc, superoxide dismutase antioxidant enzyme cofactors, were present at nutritionally relevant levels, positing a potential function of the seed in oxidative stress regulation [37, 38]. Ca and Mg are critical for bone structure, neuromuscular function, and enzyme control. Equilibrium of Ca and Mg is required for metabolic disease prevention [39]. The higher level of manganese within the embryo supports earlier findings by Mandizvo and Odindo [23] that manganese has a tendency to be sequestered in the cotyledons, where it plays a role in germination and energy metabolism.

WHO/FAO [40] documents that Na/K < 1 diets are ideal for cardiovascular health. Sodium intake at high levels can elevate blood pressure, while potassium can prevent this syndrome. The associated K/Na ratios also indicate that Malabar chestnut seeds inherently have higher levels of potassium than sodium, consistent with their potential use in blood pressure management and electrolyte balance. Ca/P ratios were below the minimum standard requirement of 1.0 suggested by NRC [41] to provide maximum bone mineralization. This suggests that the bioavailability of calcium might be compromised, particularly in the coat (MCSC = 0.41) and embryo (MCE = 0.50). Despite the relatively high phosphorus in all fractions, its contribution to energy metabolism and nucleic acid synthesis still exists. Low Ca/P ratios mean that such seeds must be eaten with foods rich in calcium to rectify existing imbalances. Ca/Mg ratios, however, were within the optimal range (1–2) proposed by Costello et al. [42], which reflects an ideal balance between calcium and magnesium for metabolic functions and bone growth. The values also fall within the overall range (0.6–11.3) presented by Ostrowska and Porębska [43] for food plant materials.

The Fe/Zn ratios (4.24–9.67) were higher than the critical value of 2 recommended by WHO [44] for optimal zinc absorption, which suggests that the relatively higher iron content may impede zinc bioavailability, especially in the embryo. The Zn/Cu ratios were similarly lower than the recommendation of 5–10, suggesting less risk of copper accumulation. Similarly, Fe/Cu ratios (4.3–19.0) were higher in the coat, suggesting greater availability of iron relative to copper in that fraction.

The potassium-to-(calcium + magnesium) ratio [K/(Ca + Mg)] is a critical measure of mineral balance, and it was highest in WMC (1.88), then in MCE (1.21), and lastly in MCSC (1.17). Since a ratio of more than 2 reflects mineral antagonism [45], such values less than the same being observed reflect the fact that the seed elements possess marvelous cationic balance and are perfect as nutritionally healthy food material.

Essential amino acids have multifunctional roles in protein synthesis, tissue repair, and nutrient absorption that are pivotal to human development and metabolic homeostasis. The high arginine content in Malabar chestnut suggests strong neurological and cardiometabolic effects. Arginine is a biochemical precursor to nitric oxide production and hence enables enhanced neural transmission, vascular tone, and immune response. Its occurrence suggests that the seed would be valuable for neuroprotection and circulation if incorporated into functional foods.

The relatively low content of tryptophan in all seed fractions points to metabolic safety. Although tryptophan is necessary for serotonin production and for sleep regulation, in excess, it has been linked to heartburn, restlessness, and metabolic aberration. The moderate levels reported here confirm that Malabar chestnut seeds are safe for consumption without the risk of tryptophan-induced negative effects and validate their use as a common dietary supplement.

Leucine, the most abundant essential amino acid in all the samples, confirms previous reports on the amino acid profile of Malabar chestnut and aligns with findings for African locust bean [46]. Dominance by leucine has significant nutritional implications because it activates the mTOR signaling pathway, which activates muscle protein synthesis, regulates glucose homeostasis, and promotes recovery from oxidative stress [47, 48]. The high leucine composition, therefore, identifies the seedʼs potential role in enhancing metabolic well-being and food functionalization.

The high content of non-essential amino acids, particularly glutamic acid, contributes additionally to the biochemical richness of the seed. Glutamic acid is a participant in neurotransmission, cellular energy metabolism, and detoxifying pathways. Non-essential amino acids also play diverse regulatory functions in cancer metabolism, immune protection, and oxidative homeostasis [49]. These findings suggest that Malabar chestnut not only forms an equilibrated protein food but also a bioactive amino acid reservoir of physiological and therapeutic interest.

Generally, the amino acid composition indicates that the embryo is better off metabolically with higher levels of essential and non-essential amino acids. This distribution attests that the embryo has a significant function in the nutritional and functional integrity of the seed, validating the worth of Malabar chestnut as an excellent plant protein source for food and nutraceutical applications.

Phenolic phytochemicals prevent the autoxidation of unsaturated lipids to avoid the formation of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL), a causative factor of cardiovascular diseases [50]. The free phenolic contents of the samples being studied were lower compared to those previously reported, combined free and bound phenolics by Oboh and Ademosun [51]. Except for the seed coat, phenolic content in the samples was similarly lower than that observed in some green leafy vegetables consumed conventionally in Nigeria [52]. The three samples, nonetheless, had higher phenolic content than the control standard reference compound, gallic acid. The phenol content is higher than the result presented by Sukrasno et al. [53], where TFC ranged from 0.251 to 0.359 mg QE/g.

Among the samples, MCSC (seed coat) exhibited the highest absorbance at 700 nm, which, according to Subramanian et al. [54], indicates a greater reducing power. This would mean that part of the bioactive constituents, such as tocopherols, acted as electron donors. The readings were less than those reported in edible mushrooms [55].

The antioxidant capacity of the extracts was also examined using DPPH• and ABTS•+ radical scavenging assays, robust methods to quantify the ability of bioactive compounds, plant extracts, and food matrices to scavenge reactive species. The DPPH• assay measures the antioxidant capacity to neutralize the stable purple DPPH radical through electron transfer [56], whereas the ABTS•+ assay measures the scavenging of the blue-green ABTS•+ cation radical, exhibiting intense absorption at 734 nm [57].

Results of the DPPH• assay (Figure 1E) showed that compounds present in the chestnut extracts were able to donate electrons and hydrogen atoms to terminate radical chain reactions. The FRAP values obtained were in agreement with those of Akinyede et al. [10], showing that the seed coat was more active than the embryo. These findings were in agreement with Sultana et al. [58] but better than Sukrasno et al. [59], showing that the embryo had relatively lower DPPH• radical scavenging activity.

Iron chelation activity also points out the antioxidant value of the samples. Although iron is crucial in oxygen transport, respiration, and a great number of enzymatic processes, its heightened reactivity also predisposes it to oxidative lipid, protein, and cellular structure damage [59]. The significant Fe2+-chelating activity of the samples thus represents a crucial protective aspect against oxidative stress [60], highlighting their potential nutritional and functional value.

Antinutrients and plant toxins are known to interfere with the bioavailability of some nutrients [61]. Several antinutrients exist in plants, fruits, and seeds. Some of these antinutrients include phytate, saponin, tannin, oxalate, and alkaloids, among others. The utilization of these antinutrients may produce good or adverse effects [62]. The phytate values are higher than the results obtained by Arise et al. [63] for jack bean at 325.47 mg/100 g and 92.52 mg/100 g for raw and processed samples, respectively. This is also the same for the values (0.15–0.36 mg/g) reported by Odedeji et al. [64]. This shows that the samples are less likely to prevent absorption of important elements when compared to the assessed jackbeans. This is because phytate forms insoluble complexes with minerals in cereals and legumes, reducing their digestibility and limiting their absorption [33]. Phytate, however, is beneficial in some cases, as it was observed to slow carbohydrate digestion and reduce blood glucose levels, lipids, and carbohydrates, as highlighted by Pujol et al. [65]. Moreover, Thakur et al. [62] stated that it reduces blood clots and bad cholesterol. It was also noted by Upadhyay et al. [66] that some studies suggest low concentrations of phytates and phenolic compounds may help protect against cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Oxalate in plants forms complexes with essential trace metals, reducing their availability for physiological and biochemical functions [67]. The saponin level of the samples is high, and could potentially make the samples toxic, which requires effective processing before consumption. Generally, antinutritional factors are known to be potentially toxic. However, this antinutritional factor can be beneficial to the body, depending on the amount ingested [68]. Furthermore, subjecting some antinutrient-containing foods to a considerable amount of heat treatment renders them inactive [69], thereby making such food safer for consumption.

The study demonstrated that the seed coat of Malabar chestnut exhibits significantly higher antioxidant activity compared to the embryo. This finding suggests that the seed coat has potential for use in food applications, either as a standalone ingredient or in blends with other food materials. Maximizing the use of such underutilized plant components can contribute to reducing food waste and enhancing food security. Furthermore, the sustainable utilization of this seed aligns with global efforts to minimize waste and promote environmental conservation, thereby positively impacting climate resilience. Additionally, the moderate levels of antinutrients detected in the samples indicate that Malabar chestnut can be safely consumed with minimal risk to human health, further supporting its potential as a viable food source. It is important to check the activities of the chemical components of the samples, especially the seed coat, on living organisms. Therefore, the authors suggest an in vivo investigation of the study. The microbial analysis and the fatty acids of the products should also be investigated to analyze their safety. Additionally, the different parts of the Malabar chestnut should be subjected to processing techniques in order to show the impact of the processing techniques on the nutrient contents of the samples.

ANOVA: Analysis of Variance

FRAP: ferric reducing antioxidant power

FUTA: Federal University of Technology, Akure

MCE: Malabar chestnut embryo

MCSC: Malabar chestnut seed coat

TPC: total phenolic content

WMC: whole Malabar chestnut

AIA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. DSA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Both authors read and approved the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

All the raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

This research received no external funding.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 419

Download: 35

Times Cited: 0