Affiliation:

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

2Department of Public Health and Maritime Transport, Faculty of Medicine, University of Thessaly, 38221 Volos, Greece

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3809-4271

Affiliation:

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

3Department of Medical Laboratory Science, McPherson University, Seriki Sotayo 110117, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3587-9767

Affiliation:

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

4Department of Medical Laboratory Science, College of Basic Health Sciences, Achievers University, Owo 341104, Nigeria

Email: uthmanadebayo85@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-2000-7451

Affiliation:

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-2172-2866

Affiliation:

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-2544-7606

Affiliation:

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

5Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Basic Medical Science, Adeleke University, Ede 232104, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-6030-0061

Affiliation:

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-5495-806X

Affiliation:

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-6257-199X

Affiliation:

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8551-1465

Affiliation:

6Department of Nursing Science, College of Health Sciences, Bowen University, Iwo 232102, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-4698-1333

Affiliation:

7Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SIMAD University, Mogadishu 2526, Somalia

8SIMAD Institute for Global Health, SIMAD University, Mogadishu 2526, Somalia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5991-4052

Affiliation:

7Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SIMAD University, Mogadishu 2526, Somalia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7319-6153

Affiliation:

9Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, WC1E 7HT London, United Kingdom

10Research and Innovation Office, Southern Leyte State University, Sogod 6606, Philippines

11Center for Research and Development, Cebu Normal University, Cebu 6000, Philippines

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2179-6365

Explor Drug Sci. 2026;4:1008144 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2026.1008144

Received: September 01, 2025 Accepted: December 05, 2025 Published: January 28, 2026

Academic Editor: Xiqun Jiang, Nanjing University, China

Background: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) among Gram-positive bacteria has emerged as a significant global health threat, with pathogens such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE) exhibiting increasing resistance to conventional antibiotics. This systematic review evaluates new advances in nanomaterial-based antimicrobial agents as innovative solutions to combat AMR in Gram-positive bacteria.

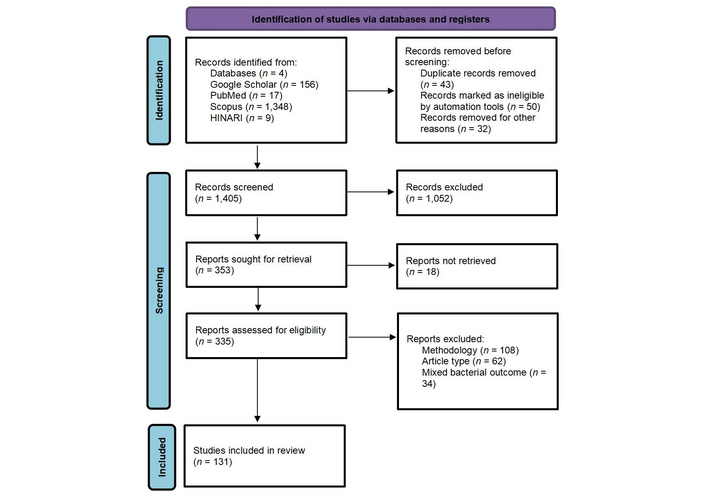

Methods: Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, studies published between 2014 and 2024 were systematically screened and analysed from databases including PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and HINARI. From an initial 1,405 articles, 131 experimental studies that met the inclusion criteria were systematically analysed to harness the advances in nanomaterial-based antimicrobial agents in combating AMR in Gram-positive bacteria.

Results: The included studies demonstrated that various nanomaterials, including silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs), copper and copper oxide nanoparticles (Cu/CuO NPs), as well as polymeric and hybrid systems, exhibited potent antibacterial and antibiofilm activities. Key mechanisms of action included bacterial membrane disruption, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, intracellular interference, and targeted drug delivery. Many nanomaterials showed enhanced efficacy and synergistic effects when combined with conventional antibiotics, effectively reducing bacterial load and inhibiting biofilm formation in resistant strains like MRSA.

Discussion: Nanomaterials offer a multifaceted approach to overcome the evolving resistance mechanisms in Gram-positive pathogens, showing significant preclinical and clinical success. Despite these substantial preclinical results, challenges such as cytotoxicity, environmental impact, scalability, and the potential for resistance adaptation remain unaddressed. Furthermore, important translational barriers persist, most notably insufficient pharmacokinetic data and unclear regulatory pathways. Future efforts must focus on standardized manufacturing, comprehensive toxicity studies, and robust clinical trials to bridge the gap between laboratory innovation and practical therapeutic application.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a major global health challenge, responsible for approximately 1.27 million deaths in 2019 and contributing to 4.95 million more globally [1, 2]. Overuse of antibiotics in humans, animals, and agriculture drives the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE), and β-lactam-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae [3–5]. Gram-positive bacteria readily acquire resistance via altered penicillin-binding proteins (e.g., PBP2a), thickened cell walls, efflux pumps, and biofilm formation, which hinder antibiotic efficacy [6–9]. Compounding the crisis, new antibiotic development is constrained by high research and development costs, regulatory hurdles, and limited profitability [10].

Nanomaterials offer a promising strategy to combat Gram-positive AMR pathogens due to their multimodal antimicrobial mechanisms, including membrane disruption, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, biofilm penetration, and intracellular delivery [11]. Among these, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) disrupt microbial membranes, while nanomaterials enhance solubility, stability, and controlled drug release [12]. Their activity is influenced by physicochemical properties such as size, shape, charge, and composition. For instance, CuO NPs disrupt membranes and generate ROS, and chitosan nanoparticles interact electrostatically with bacterial surfaces to inhibit biofilms [13, 14]. Broadly, antimicrobial nanoparticles can be metallic (e.g., silver, copper, zinc), polymeric [e.g., chitosan, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)], lipid-based (e.g., liposomes), or carbon-based (e.g., graphene oxide), each employing distinct mechanisms to overcome bacterial resistance [11, 15].

Despite promising preclinical results, most studies remain in vitro or in animal models, with limited data on long-term safety, biodistribution, or chronic toxicity [15, 16]. Translational challenges include standardization, manufacturing, and the potential impact on beneficial microbiota and ecosystems. Gram-positive pathogens are a critical focus due to their thick peptidoglycan walls and escalating resistance, which necessitate targeted nanomaterial strategies [17]. Emerging diagnostic and therapeutic technologies, including dual-function nanomaterials, hold potential but require careful evaluation to prevent resistance and mitigate ecological risks [18, 19]. This review aims to consolidate current preclinical nanomaterial-based strategies against Gram-positive AMR pathogens, emphasizing translational barriers and future research priorities.

This systematic review followed PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, covering article items including title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, and discussion. The study protocol included research questions, aims, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and a methodological approach. A PRISMA 2020 Checklist (S1) was used to ascertain that this systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines.

What is the efficacy of nanotechnology-based antimicrobial agents against AMR Gram-positive bacteria?

What types of nanomaterials have been used to target Gram-positive bacteria?

What are the mechanisms of action of these nanotechnology-based antimicrobials?

What are the limitations, toxicity concerns, and future potentials of these technologies?

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and HINARI to identify studies published between 2014 and 2024. This timeframe was chosen to capture a decade of significant advances in nanomaterial-driven antimicrobial research and its application against AMR pathogens. The search strategy employed precise Boolean strings, including combinations of keywords and MeSH terms such as “nanotechnology” OR “nanoparticle” OR “nanomaterial” AND “antimicrobial resistance” OR “AMR” OR “antibiotic resistance” AND “Gram-positive bacteria”. Boolean operators (AND, OR) and truncations were systematically applied to maximize the retrieval of relevant records, specifically evaluating the effectiveness of nanomaterial-based antimicrobials in combating AMR, specifically in Gram-positive bacteria, while filtering duplicates. Google Scholar results were filtered for quality by prioritizing peer-reviewed journal articles published in reputable and indexed journals. Studies from non-indexed or low-impact sources were excluded after assessing methodological rigor and citation relevance. In addition to database searching, manual screening and backward citation tracking were performed to identify additional studies referenced in the bibliographies of eligible articles. Two researchers (UOA and OJ Okesanya) independently conducted database searches and preliminary analyses to ensure consistency and completeness of retrieved data.

Included studies comprised experimental preclinical designs (in vitro, in vivo, or combined) and clinical observational or interventional studies that evaluated the antibacterial effects of nanomaterials against Gram-positive bacteria.

The following inclusion criteria were established using the population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) framework:

Population (P): Gram-positive bacteria exhibiting resistance to conventional antibiotics.

Intervention (I): Nanomaterial-based antimicrobial agents.

Comparison (C): Conventional antibiotics or untreated controls.

Outcome (O): Antimicrobial efficacy, bacterial load reduction, biofilm disruption, toxicity, and resistance modulation.

This review included studies that focused on utilizing nanomaterial-based antimicrobial agents to combat Gram-positive AMR bacteria. Eligible studies were published between 2014 and 2024 and in English. Studies that did not provide relevant data or focused solely on other microorganisms were excluded. Qualitative studies, preprints, narrative and systematic review articles, editorials, commentaries, conference abstracts, and data from grey and unpublished sources were excluded due to inconsistency in reporting. Data on nanomaterial-based agents, mechanisms of action, and key findings were extracted.

Study selection was conducted in a two-stage process by two independent reviewers (KBO and OBA) who screened titles and abstracts for relevance based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text screening was conducted for potentially eligible articles. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (CNC). Manual backward citation screening was also applied to ensure comprehensiveness. To minimize bias, no restrictions were placed on author affiliation, journal of publication, or study outcomes. Only studies that met the inclusion criteria were considered. Paper titles reported in tables were preserved or paraphrased for clarity and neutrality.

Data from eligible studies were independently extracted by two reviewers (AKY and KOT) using a standardized form that included nanomaterials used, pathogen targeted, antimicrobial mechanism of action, study type, key findings, advantages of nanomaterials over conventional agents, and limitations. Nanomaterials were categorized based on their chemical composition and synthesis origin into one of seven classes: metal-based, metal oxide-based, polymeric, lipid-based, carbon-based, biologically derived, or inorganic-based. This classification enabled clearer interpretation of mechanisms of action and antibacterial effectiveness across material types. All extracted data were verified for consistency against the original publication. Inconsistencies were resolved through consensus. Descriptive analysis was performed to summarize trends in nanomaterial types, pathogen types, and in vitro/in vivo outcomes. As this is a descriptive systematic review, no inferential statistical tests were applied.

The Joanna Briggs Instituteʼs Critical Appraisal Checklist was used to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies, with an 8-point rating system and a minimum score of 50% required.

A total of 1,530 articles were identified through database searches. After removing 125 duplicates, 1,405 records were screened by title and abstract, excluding 1,052 that did not meet the inclusion criteria. An additional 18 studies were excluded due to non-material interventions, focus on Gram-negative bacteria, review articles, or incomplete data. Of 335 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, a total of 204 were excluded, of which (n = 108) were for inappropriate methodology, article type (reviews/commentaries, n = 62), or mixed bacterial outcomes without separable Gram-positive data (n = 34). Ultimately, 131 studies were included in the final synthesis (Figure 1, Table 1 [20–150]). Included studies were primarily in vitro, with China and India accounting for the highest representation (16% each). Many studies utilized green-synthesized nanoparticles from plant extracts. Some employed composite or hybrid nanoparticles, including polymer-coated, drug-loaded, or biologically stabilized forms. Targeted Gram-positive pathogens included Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA and MSSA) [20, 22, 24], other Staphylococcus spp. [29, 45], Streptococcus spp. [61, 64], Listeria spp. [82], Clostridium perfringens [109], Bacillus spp. [39, 44], and Enterococcus spp. [93, 94], highlighting the broad-spectrum activity of nanomaterials against resistant strains.

PRISMA flowchart of included studies. Adapted from [151]. © 2024-2025 the PRISMA Executive. Licensed under a CC BY 4.0. PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Summary of nanomaterial-based antimicrobials targeting Gram-positive bacteria.

| S/N | Citation | Country | Nanomaterial type used | Nanomaterials class | Pathogen (s) targeted | Study type | Key findings | Mechanism of action | Advantages over conventional agents | Limitations | Translational stage/clinical phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [20] | China | Quercetin (Qu) and acetylcholine (Ach) to the surface of Se nanoparticles (Qu–Ach@SeNPs) | Metal-based | Staphylococcus (S.) aureus | Experimental | Efficient antibacterial and bactericidal activities against superbugs without resistance | Combined with theacetylcholine receptor on the bacterial cell membrane and increase the permeability of the cell membrane | Efficient antibacterial activity against MDR superbugs | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 2 | [21] | Pakistan | Ciprofloxacin-loaded gold nanoparticles (CIP-AuNPs) | Metal-based | Enterococcus (E.) faecalis JH2-2 | Experimental | Promising, biocompatible therapy for drug-resistant E. faecalis infections warrants further study | Disrupts membrane potential, inhibits ATPase, and blocks ribosome–tRNA binding, impairing bacterial metabolism | Exerted enhanced antibacterial activity compared with free CIP | Required further studies on its effects in animal models, which may aggregate and unload due to high salt concentrations | In vivo (animal model) |

| 3 | [22] | India | Copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) | Metal oxide-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Strong antifungal and antibacterial activity | Effective against Gram-positive bacteria | Low-cost and possesses a high surface area | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 4 | [23] | India | Platinum nanoparticles (Pt NPs) | Metal-based | Bacillus (B.) cereus | Experimental | Shows dose-dependent antibacterial activity | Denature critical bacterial enzyme thiol groups | Synthesized using eco-friendly biological methods | In vitro only; in vivo efficacy and toxicity not assessed | In vivo (animal model) |

| 5 | [24] | Australia | Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) | Metal-based | MRSA, E. faecalis | Experimental | Strong antibacterial effect against eight species, including drug-resistant strains | ATP depletion, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, membrane depolarization, and membrane disruption | Unlike the conventional antibiotic, kanamycin’s NP-ε-PL did not readily induce resistance | Further work is required to investigate use in a real clinical setting | Clinical |

| 6 | [25] | South Korea | Magnetic core-shell nanoparticles (MCSNPs) | Metal-oxide-based | MRSA | Experimental | Radiofrequency (RF) current kills trapped bacteria in 30 minutes by disrupting the membrane potential and complexes | RF stimulation of MCSNP-bound bacteria disrupts the membrane potential and complexes | - | Study performed in vitro; further in vivo validation is necessary | In vivo (animal model) |

| 7 | [26] | India | Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | < 50 nm AgNPs act against drug-resistant bacteria | - | - | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 8 | [27] | China | Nanoparticles functionalized with oligo(thiophene ethynylene (OTE) and hyaluronic acid (HA) (OTE-HA nanoparticles) | Polymeric | MRSA | Experimental | Bacterial hyaluronidase hydrolyzes OTE-HA NPs, releasing OTE fragments to kill bacteria | OTE fragments disrupt bacterial membranes by hydrophobic interactions and van der Waals forces | OTE-HA NPs prevent premature drug leakage and show superior biocompatibility | Potential cytotoxicity of OTE-based agents is a major concern. | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 9 | [28] | India | Biogenic copper nanoparticles (CuNPs) and zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) | Metal-and metal-oxide-based | S. aureus, including MRSA | Experimental | Exhibit strong low-dose antibiofilm activity and boost antibiotic efficacy | Nanoparticles interact closely with microbial membranes due to their small size | Synergistic enhancement with antibiotics | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 10 | [29] | India | AgNPs | Metal-based | B. subtilis, S. haemolyticus, and S. epidermidis | Experimental | AgNPs block bacterial growth and biofilms below the antibiotic minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), with minimal cytotoxicity to mammalian cells | Mislocalizes FtsZ/FtsA, damages membranes, and blocks cell division | Reduced cytotoxicity towards mammalian cells | Limited Ag+ release and hydrogel shielding reduce AgNP effectiveness | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 11 | [30] | Spain | Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) | Inorganic-based | S. aureus | Experimental | MSNEPL-Cin demonstrated excellent antimicrobial activity at very low doses | Microbial proteases trigger cinnamaldehyde release from MSNs for localized antimicrobial action | Enhanced antimicrobial efficacy via biocontrolled uncapping for targeted delivery | Raw data cannot be shared due to technical limitations | In vivo (animal model) |

| 12 | [31] | China | Curcumin-stabilized silver nanoparticles (C-Ag NPs) | Metal-based/biologically derived | S. aureus and MRSA | Experimental | Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)/citric acids (CA)/C-Ag nanofibers show sustained broad-spectrum activity, remove biofilms, and suppress MRSA resistance genes | Antimicrobial action via ROS and membrane damage; disrupts MRSA carbohydrate and energy metabolism | - | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 13 | [32] | India | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus (tetracycline-resistant) | Experimental | Strong antibacterial at 100 µg/mL, plus antioxidant and anti-HeLa/MCF-7 activity | Interrupt genes involved in the cell cycle | Enhanced antibacterial properties compared to conventional agents | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 14 | [33] | China | Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) decorated with AgNPs coated with mesoporous silica via TSD mediation (SWCNTs@mSiO2-TSD@Ag) | Carbon/Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Significantly enhanced antibacterial activity against S. aureus, with MICs below commercial AgNPs | Damages bacterial cell membranes and accelerates Ag+ release, boosting antibacterial activity | Outperformed commercial AgNPs and SWCNTs@mSiO2-TSD, enhancing bacterial clearance and wound healing in vivo | Grafting Ag NPs onto CNTs requires complicated procedures, risking structural damage | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 15 | [34] | China | AuNPs modified with 5-methyl-2-mercaptobenzimidazole (mMB-AuNPs) | Metal-based/organic-functionalized | MRSA | Experimental | Neutral MMB-AuNPs destroyed MRSA, unlike charged AMB- and CMB-AuNPs | Induce bacterial cell membrane damage, disrupt membrane potential, and downregulate ATP levels, leading to bacterial death | - | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 16 | [35] | Jordan | Silver, magnetite nanoparticles (Fe3O4/AgNPs), and magnetite/silver core-shell (Fe3O4/Ag) nanoparticles | Metal/Metal oxide-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Fe3O4/Ag NPs exhibited superior antibacterial activity compared to Fe3O4 or Ag NPs, strongly inhibiting pathogens | - | - | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 17 | [36] | USA | Polydopamine nanoparticles (PD-NPs) | Polymer-based | MRSA | Experimental | Composite nanoparticles fully eradicated MRSA and removed toxic heavy metals from water | Membrane captures pathogens; ε-poly-L-lysine kills bacteria. Metal is removed by active binding sites | Surface area for enhanced reactivity and effective capture of heavy metals and superbugs | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 18 | [37] | China | Mixed-charge hyperbranched polymer nanoparticles (MCHPNs) | Polymer-based | S. aureus (ATCC 6538), MRSA | Experimental | Highly selective (SI > 564), eradicates resistant bacteria, delays resistance, and blocks biofilms | Charge-targeted membrane disruption alters permeability, causing bacterial death | Offers greater bacterial selectivity and lower mammalian toxicity than other cationic materials | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 19 | [38] | - | Silver, copper oxide, and titanium dioxide nanoparticles (AgNPs, CuO NPs, and TiO2 NPs) | Metal/Metal oxide-based | S. aureus, MRSA | Experimental | Silver nanoparticle coatings achieved > 99% bacterial growth inhibition within 24 h | Nanoparticles disrupt bacterial cell membranes and produce ROS | The nanoparticles overcome biofilm barriers that conventional antibiotics struggle with | Needs further studies on long-term safety, biocompatibility, and large-scale trials; clinical data are lacking | Clinical |

| 20 | [39] | India | AgNPs | Metal-based | Bacillus licheniformis | Experimental | AgNP-treated cotton fabrics showed wash-durable antimicrobial activity with 93.3% inhibition | Induces higher ROS production inside bacterial cells | Offer improved wash durability compared to conventional agents | Limited exploration of AgNPs resistance in various bacterial strains | In vivo (animal model) |

| 21 | [40] | China | AuNPs | Metal-based | MRSA | Experimental | Showed strong antibacterial effects and enhanced wound healing against MDR bacteria | Disrupts bacterial membrane structure and cytoplasmic leakage | - | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 22 | [41] | China | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Showed strong bactericidal effects on MDR bacteria; biofilm formation was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner | Effectively hinders biofilm formation, with inhibition rising at higher AgNP concentrations | Significant bactericidal effect on a variety of drug-resistant bacteria | No regulation on AgNP morphology, size, surface, or antibacterial properties | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 23 | [42] | India | AgNPs stabilized with poloxamer (AgNPs@Pol) | Biologically derived | MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) | Experimental | Synergistic effect with methicillin was observed. ROS increased, and antimicrobial resistance (AMR)-related genes were downregulated | Induction of ROS and downregulation of AMR and adhesion genes | Significant 100% efficacy against MRSA and MSSA, reduction in colony-forming units (CFU) | Further primary cells and in vivo models are required for validation | In vivo (animal model) |

| 24 | [43] | India | Palladium nanoparticles (PdNPs) | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Showed MICs of 52–68 µg/mL against MDR S. aureus | - | PdNPs can be effective in the clinical management of MDR pathogens | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 25 | [44] | UAE | Cinnamic acid-coated magnetic iron oxide and mesoporous silica nanoparticles | Metal-based/biologically derived | MRSA, B. cereus | Experimental | Greatly enhanced destruction of MDR bacteria over drugs alone, with minimal cytotoxicity | - | Completely eradicated MRSA at much lower doses than antibiotics alone | Further in vivo and clinical studies are needed for validation | Clinical |

| 26 | [45] | Saudi Arabia | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus and S. epidermidis | Experimental | Exhibited strong antibacterial activity with an MIC of 9.375 μg/mL against MDR strains | Ag+ ions bind thiols, disrupt membranes, cause oxidative damage, and kill bacterial cells | Metal nanoparticles (m-NPs) bypass resistance mechanisms in bacteria | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 27 | [46] | Nigeria | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Exhibited antibacterial at 25 µg/mL; MIC 25–50 µg/mL, minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) 75–100 µg/mL | - | - | Need more studies on environmental effects, antibacterial mechanisms, and AgNP–antibiotic synergy | In vivo (animal model) |

| 28 | [47] | Mexico | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus ATCC 25923 | Experimental | Seasonal sample from winter (SPw)-AgNPs showed potent antibacterial/antibiofilm activity (MBC 25–100 µg/mL), driven by quercetin/galangin, and were non-cytotoxic to HeLa and ARPE-19 cells | - | Reduced cytotoxicity due to biosynthesis; effective at low concentrations compared to previous reports using chemically synthesized AgNPs | Future work should test strains with defined virulence and resistance to evaluate clinical relevance | Clinical |

| 29 | [48] | China | LL-37@MIL-101-Van (MIL-101 nanoparticles loaded with LL-37 peptide and Vancomycin) | Biologically derived | MRSA | Experimental | Showed strong antibacterial effects, enhanced wound healing, enabled near infrared (NIR) imaging, and synergistically killed MRSA via •OH, LL-37, and vancomycin | MIL-101 (Fe3+) drives Fenton-like •OH production from H2O2 in acidic sites; LL-37 disrupts membranes, vancomycin blocks cell wall synthesis | - | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 30 | [49] | India | Ag–Cu NPs | Metal-based | S. aureus and MRSA | Experimental | Effective at MIC 156.3–312.5 µg/mL. Inhibited growth rapidly, reusable, and eco-friendly synthesis | Membrane damage and ROS overproduction leading to lipid oxidation | Reusability, rapid action (30 min), green synthesis from agro-waste, stability for repeated use | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 31 | [50] | Iran | Silver chloride nanoparticles (AgCl NPs) | Metal-based | S. aureus and B. subtilis | Experimental | Showed strong antibacterial activity against drug-resistant strains and cytotoxicity to MCF-7 and HepG2; MIC 12.5–50 µg/mL | Disrupts bacterial membranes and binds to proteins and DNA; Ag+ inhibits replication and inactivates proteins; ROS contributes to cytotoxicity | The nanoparticles exhibit higher antioxidant activity than conventional agents | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 32 | [51] | Nigeria | Chitosan nanoparticles | Polymeric | S. aureus (haemolytic and clinical strains) and S. saprophyticus | Experimental | 39 mm inhibition zone against S. saprophyticus; MIC: 0.0781–0.3125 mg/mL | Increases bacterial membrane permeability and binds DNA, blocking mRNA synthesis | More effective than levofloxacin against S. saprophyticus; comparable efficacy for other tested strains | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 33 | [52] | China | ROS-responsive, bacteria-targeted moxifloxacin nanoparticle for moxifloxacin delivery (MXF@UiO-UBI-PEGTK) | Biologically derived | S. aureus, and MRSA | Experimental | ROS-responsive moxifloxacin (MXF) release improved biofilm penetration in vitro and treated endophthalmitis in vivo | ROS-cleavable poly (ethylene glycol)-thioketal (PEG-TK) triggers MXF release in high ROS; UBI29–41 targets bacteria/biofilms; MXF blocks DNA gyrase and topoisomerase | Outperformed free moxifloxacin in biofilm penetration, ROS-responsive targeted delivery, and in vivo infection resolution with reduced inflammation | - | In vivo (animal model) |

| 34 | [53] | India | Silver oxide (Ag2O) nanoparticles | Metal-oxide-based | MRSA | Experimental | Demonstrated potent antibacterial activity against MRSA, with a 17.6 ± 0.5 mm inhibition zone | Ag2O nanoparticle production may be enzyme-mediated | Ag2O nanoparticles are freely dispersed, enhancing their effectiveness | - | In vivo (animal model) |

| 35 | [54] | Egypt | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Showed strong activity vs. MDR bacteria (MIC 31–250 µg/mL, MBC 125–500 µg/mL) | Disruption of bacterial cell membrane structure, leakage of intracellular contents | AgNPs (S4) showed superior antibacterial activity compared to AgNO3 and ginger extract alone | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 36 | [55] | India | Iron oxide nanoparticles (FeONPs) | Metal-oxide-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Strong antibacterial/antifungal activity; rapid synthesis verified by UV-Vis, XRD, SEM, TEM | Act through direct contact with bacterial cell walls | Enhance membrane permeability and cell destruction | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 37 | [56] | India | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Produced 27 mm and 32 mm zones vs. MDR S. aureus | Disrupts the outer membrane, binds thiols, impairs replication, and generates ROS, causing damage and enzyme inhibition | AgNPs showed 27 mm (S. aureus), far exceeding antibiotics (≤ 5 mm) | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 38 | [57] | Malaysia | AgNPs | Metal-based | MRSA | Experimental | - | Phyto-AgNPs are antibacterial, and with antibiotics, greatly increase MRSA inhibition zones | AgNP-antibiotic combinations showed significantly larger inhibition zones compared to antibiotics or AgNPs alone | The precise mechanism of action for nanoparticles remains unclear | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 39 | [58] | Lithuania | Nisin-loaded iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (IONPs) | Metal oxide/biologically derived | B. subtilis ATCC 6633 | Experimental | Nisin-magnetic nanoparticles combined with pulsed electric field (PEF)/pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) boost antimicrobial action and resistance synergistically | Nisin resistance mechanisms were identified in Gram-positive bacteria | Nanomaterials enhance the stability and activity of antimicrobial agents | Mechanism not fully understood and requires further investigation | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 40 | [59] | Ethiopia | Copper oxide nanoparticles (CONPs) | Metal-oxide-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Active against Gram-positive diabetic foot isolates, with S. aureus showing the largest zone (16 mm) | CONPs adhere to bacterial surfaces and penetrate cells, destroying bacterial biomolecules and structures | CONPs possess strong antioxidant potential compared to conventional agents | Still needs some modifications on CONPs concerning ascorbic acid activity | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 41 | [60] | Iran | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Strong activity MIC ≈ 0.1 µg/mL for S. aureus and degraded pollutants photocatalytically | Membrane penetration/disruption, thiol binding, DNA replication inhibition, and ROS generation | AgNPs@SI had lower MICs than ciprofloxacin for some strains and were eco-friendly synthesized without toxic chemicals | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 42 | [61] | Egypt | AgNPs | Metal-based | Streptococcus agalactiae | Experimental | Showed antimicrobial activity against MDR mastitis pathogens | AgNPs act by disrupting microbial membranes, causing rupture and content leakage | Effective against MDR pathogens with lower cytotoxicity and an alternative to antibiotics in mastitis treatment | No in vivo studies support the clinical use of these compounds | Clinical |

| 43 | [62] | Iran | Chitosan-based nanofibrous mats embedded with silver, copper oxide, and zinc oxide nanoparticles (CS-nACZ) | Metal oxide-polymeric based | S. aureus | Experimental | Strong antimicrobial action, healed wounds in vivo, and were non-toxic to fibroblasts | - | Active against MDR bacteria (unlike single NPs), promoted healing, and was non-cytotoxic | - | In vivo (animal model) |

| 44 | [63] | Lithuania | Methionine-capped ultra-small gold (Au@Met) nanoparticles and methionine-stabilized magnetite-gold (Fe3O4@Au@Met) nanoparticles | Metal/biologically derived | MRSA, Micrococcus luteus | Experimental | Showed 89.1–75.7% against Gram-positive bacteria at 70 mg/L concentration | The presence of Au+ ions causes interaction with bacterial membranes and metabolic imbalance | High biocompatibility, non-toxicity, effective at low concentration, and activity against MDR pathogens | - | In vivo (animal model) |

| 45 | [64] | Iran | Chitosan NPs and TiO2 NPs | Polymer/Metal-based | Streptococcus mutans | Experimental | Experimental group showed marked Streptococcus mutans reduction at 1 day, 2 months, and 6 months, highest in the upper second premolars at 6 months | - | - | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 46 | [65] | Brazil | Tea tree oil and low molecular weight chitosan (TTO-CH) nanoparticles | Biologically derived polymeric-based | Streptococcus sanguinis | Experimental | TTO-CH showed strong antimicrobial activity and had synergistic effects, matching azithromycin against mono- and mixed biofilms | Attributed to terpinen-4-ol and terpinene in TTO, the mechanism involves membrane disruption and metabolic interference | TTO-CH combination matched azithromycin in activity against oral biofilms and offers a natural alternative to antibiotics | Further studies are required to confirm efficacy in vivo and explore potential clinical applications | Clinical |

| 47 | [66] | India | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Exhibited up to 92.41% inhibition of S. aureus biofilms; anti-adhesion and biofilm disruption effects | Disrupt bacterial cell membranes, generate ROS, and interfere with cellular functions to inhibit biofilm formation | Exhibit stronger biofilm inhibition and penetration against antibiotics; plant-based eco-synthesis improves biocompatibility | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 48 | [67] | China | Epigallocatechin gallate-gold nanoparticles (E–Au NPs) | Metal/Biologically derived | MRSA and S. aureus | Experimental | NIR-triggered, achieved > 90% MRSA biofilm destruction, strong antibacterial/antibiofilm effects, and promoted wound/keratitis healing with high biocompatibility | Combines mild photothermal therapy (PTT), ROS, quinoprotein formation, gene downregulation, and cell wall disruption | Highly biocompatible with minimal side effects; synergistic photothermal–polyphenol action boosts efficacy against MDR MRSA; suitable for eye and skin infections | - | In vivo (animal model) |

| 49 | [68] | China | Nano-Germanium dioxide (GeO2)/cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) complex (nano-GeO2/CTAB complex) | Biologically derived | S. aureus | Experimental | Nano-GeO2/CTAB complex showed stronger Gram+ antibacterial activity than the individual components | - | - | More research is needed on long-term efficacy and environmental safety before use | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 50 | [69] | Iran | α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles (α-Fe2O3-NPs) | Metal oxide/biologically derived | S. aureus and B. cereus | Experimental | Exhibited significant antibacterial activity with MIC values between 0.625–5 µg/mL and MBC values between 5–20 µg/mL | ROS generation causes membrane damage and cell death, with minimal metal ion release, distinguishing them from other metal NPs | - | Requires further clinical trials and safety evaluations before medical application | Clinical |

| 51 | [70] | India | Erythromycin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles (PLGA-Ery NPs) | Polymer-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Enhanced antibacterial activity (1.5–2.1× MIC) against S. aureus, biofilm inhibition | Provided sustained drug release, better cell penetration, disrupted cell walls, and lowered efflux activity | Improved efficacy against resistant strains, biofilm inhibition, sustained drug release, and reduced toxicity | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 52 | [71] | Iran | PEG-coated UIO-66-NH2 nanoparticles loaded with vancomycin and amikacin (VAN/AMK-UIO-66-NH2@PEG) | Biologically derived | Vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) | Experimental | Stronger antibacterial/antibiofilm effects downregulated mecA, vanA, icaA, icaD; showed potent antioxidant activity | Inhibits biofilm and MDR gene expression (mecA, vanA, icaA, icaD); PEGylation enhances drug retention and delivery | Lower MIC/MBC than free VAN/AMK or VAN/AMK-UIO-66; sustained release, better stability, encapsulation, and bioavailability | Future in vivo studies are needed to assess safety, efficacy, and clinical use of these nanoparticles | Clinical |

| 53 | [72] | Nigeria | AgNPs, AuNPs, and bimetallic gold-silver nanoparticles | Metal-based | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Experimental | Showed strong antibacterial activity against S. aureus, with a MIC of 1.953 μg/mL | Metal ions are liberated into the cells by oxidation and produce ROS that attack the bacterial cells and cause cell death | Offer a potential indigenous alternative to combat antibiotic resistance | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 54 | [73] | China | Copper-doped hollow mesoporous cerium oxide (Cu-HMCe) nanozyme | Biologically derived | S. aureus | Experimental | Exhibited strong antibacterial properties against S. aureus | HMCe reduces bacterial viability via oxidative stress and disrupted nutrient transport | Shows promise for treating acidified chronic refractory wounds with infections | Further research is needed on its biosafety and vascularization mechanism | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 55 | [74] | China | Bacteria-activated macrophage membrane coated ROS-responsive vancomycin nanoparticles (Sa-MM@Van-NPs) | Biologically derived | MRSA | Experimental | Efficiently targeted infected sites and released vancomycin to eliminate bacteria, facilitating faster wound healing | Targets infections via receptor interactions and releases antibiotics in high ROS to kill bacteria | ROS-responsive release of antibiotics improves antibacterial efficacy | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 56 | [75] | Iraq | AgNPs | Biologically derived | S. sciuri and S. lentus | Experimental | Strong Gram+ activity by disrupting membranes and causing nucleic acid/protein leakage | Damaged bacterial membranes cause DNA, RNA, and protein leakage | - | Studies are needed to clarify mechanisms and assess in vivo safety | In vivo (animal model) |

| 57 | [76] | China | Polypeptide-based carbon nanoparticles | Carbon-based | S. aureus, and MRSA | Experimental | Achieved 99%+ inhibition of S. aureus and ~99% healing in MRSA wound infections | Nanozyme’s peroxidase, oxidase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)-like activities regulate ROS for bacterial inhibition | Showed high inhibition against Gram-positive S. aureus planktonic bacteria | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 58 | [77] | Egypt | Vancomycin functionalized silver nanoparticles (Ag-VanNPs) | Metal/Biologically derived | MRSA | Experimental | Lowered MIC/MBC with fractional inhibitory concentration/ fractional bactericidal concentration (FIC/FBC) ≤ 0.5, indicating synergistic action and fewer side effects | - | Synergistic action, better targeting, and much lower MIC/MBC than pure vancomycin | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 59 | [78] | India | CuNPs | Metal | S. aureus | Experimental | CuNPs showed broad antimicrobial activity, with the strongest effect against Staphylococcus aureus (27 ± 1.00 mm). | - | Outperformed vancomycin with synergistic action, lower MIC/MBC, and better targeting | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 60 | [79] | India | Sarsaparilla root extract fabricated silver nanoparticles (sAgNPs) | Metal/Biologically derived | S. aureus and MRSA | Experimental | Showed MICs 125 μM S. aureus, MRSA, and protected zebrafish from infection | At 1× MIC, sAgNPs generate excess ROS and disrupt membranes, causing depolarization | Potential to act as nanocatalysts and nano-drugs in addressing key challenges in medical and environmental research | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 61 | [80] | Pakistan | ZnO NPs and aluminum-doped ZnO NPs (Zn1−xAlxO NCs) | Biologically derived | S. aureus | Experimental | Possess largest inhibition zones (notably vs. B. cereus), with strong antimicrobial effects, low toxicity, and high biocompatibility | Zn2+ and ROS damage membranes/DNA, inhibit enzymes, and block biofilm formation | Al-doping increases antimicrobial activity through enhanced ROS generation | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 62 | [81] | Iran | Chitosan, ZnO, and ZnO–Urtica. diocia (ZnO–U. diocia) NPs | Polymer and metal-oxide-based | S. aureus | Experimental | The zone of inhibition for was greater for aqueous leaf extract against S. aureus | Interact with microbial membranes, results in structural damage, protein denaturation, and generation of ROS leading to cell death | Showed enhanced antimicrobial efficacy over crude extracts and were environmentally friendly | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 63 | [82] | Italy | Surface active maghemite nanoparticles (SAMN), colloidal iron oxide NPs with oxyhydroxide-like surface | Biologically derived | Listeria spp. | Experimental | Captured 100% of bacteria in wastewater without agitation and bound stably, non-toxically to polysaccharides and cells | Bind peptidoglycan and polysaccharides via chelation and electrostatic interactions | Non-toxic, reusable, and highly stable, and enables physical removal of Gram (+) bacteria as an alternative to antibiotics | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 64 | [83] | China | Nickel oxide nanoparticles (NiOx NPs) | Metal oxide | MRSA | Experimental | Eradicated MRSA and biofilms in vitro and in vivo and promoted wound healing, collagen deposition, and tissue regeneration in animal models | Oxygen vacancies boost ROS and photothermal effects; NiOx mimics oxidase/peroxidase to generate •OH and damage membranes, DNA, and proteins | Non-antibiotic dual-action strategy; effective against drug-resistant biofilms with high biosafety, biocompatibility, and regenerative properties | The long-term effects of NiOx NPs were not addressed. | In vivo (animal model) |

| 65 | [84] | Nigeria | Green-synthesized AgNPs using Vitex grandifolia leaves extract | Biologically derived | Streptococcus pyogenes and S. aureus | Experimental | Significant antibacterial activity against MDR pathogens; inhibition zones up to 15 mm at 100 µg/mL; concentration-dependent response | Ag+ release disrupts membranes, inactivates enzymes, generates ROS, and blocks DNA/protein synthesis | - | Further research is needed to confirm safety and biocompatibility | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 66 | [85] | Thailand | Ag/AgCl-NPs | Metal/Metal oxide based | S. haemolyticus | Experimental | MIC/MBC 7.8–15.6 µg/mL; reduced biofilm biomass ~95% and viability ~78%; caused visible cell damage | ROS-driven membrane damage, morphological changes, and reduced viability in the biofilm strain | The synthesized Ag/AgCl-NPs show an enhanced antibacterial and antibiofilm agent against S. haemolyticus | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 67 | [86] | India | ZnO NPs | Metal oxide | S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes | Experimental | Inhibited bacterial growth and biofilms in a dose-dependent manner, confirmed by SEM and CFU reduction | Antibacterial and antibiofilm effects stem from membrane disruption and ROS-induced stress | Antibiotic-loaded ZnO NPs showed stronger antibacterial activity than Li-ZnO NPs or ciprofloxacin alone | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 68 | [87] | Iraq | AgNPs | Metal-based | MDR bacteria (not specified) | Experimental | AgNPs showed significant dose-dependent antibacterial activity | - | AgNPs exhibited antibacterial activity against MDR bacteria compared to conventional agents | Nanotoxicology studies are needed to find doses balancing antibacterial efficacy and low human toxicity | In vivo (animal model) |

| 69 | [88] | Saudi Arabia | Nickel ferrite nanoparticles (NiFe2O4 NPs) | Metal-oxide-based | MRSA | Experimental | MIC 1.6–2 mg/mL, reduced biofilm formation ~50%, eradicated mature biofilms 50–76% | Membrane disruption and structural damage, blocked biofilm adherence with visible membrane deformation | NiFe2O4 NPs not only prevent the formation of biofilm, but also eliminate existing mature biofilms by 50.5–75.79% | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 70 | [89] | Portugal | Photo-crosslinked chitosan/methacrylated hyaluronic acid nanoparticles (HAMA/CS NPs) | Polymer-based | S. aureus, MRSA, and S. epidermidis | Experimental | Showed strong antibacterial/antibiofilm effects and boosted mammalian cell growth | Inhibit growth via contact, cut biofilms, and improve delivery/diffusion for antibacterial action at 37°C | Strong antibacterial/anti-biofilm effects in wounds, supports cell growth, is non-cytotoxic, and enables targeted antibiotic delivery | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 71 | [90] | Germany | PLGA-based NPs | Polymer-based | MRSA | Experimental | The efficacy against MSSA and MRSA strains was demonstrated in vitro in several bacteria strains and in vivo in the G. mellonella model | SV7-loaded nanoparticles target intracellular MRSA infections effectively | SV7-loaded nanoparticles show a safe profile at all tested concentrations | Further in vivo mouse studies are needed to optimize post-infection regimens in complex environment | In vivo (animal model) |

| 72 | [91] | Egypt | ZnO NPs | Metal oxide | S. aureus | Experimental | Showed inhibitory percentages ranging from 12.0% to 39.1%, with extract ranging from 28.0% to 52.2% | GyrB inhibition stops bacterial DNA replication, leading to bacterial death | Zinc nanoparticles exhibit potential antibacterial and anticancer properties | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 73 | [92] | India | In situ aqueous nanosuspension of PPEF.3HCl (IsPPEF.3HCl-NS) | Biologically derived | MRSA | Experimental | Inhibited bacterial growth, showing promise against intracellular MRSA | Blocks DNA rejoining and disrupts enzymatic processes as a poison inhibitor | IsPPEF.3HCl-NS enhanced log CFU reduction in S. aureus-induced murine sepsis model | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 74 | [93] | Romania | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus (ATCC 29213), MRSA, E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) | Experimental | Exhibit strong antibacterial effects by damaging bacterial cell membranes and generating oxidative stress | Ag+ ions disrupt membranes, trigger ROS and oxidative stress, block ATP synthesis, alter gene expression, and inhibit respiration | Nanomaterials offer enhanced antibacterial efficacy against MDR bacteria | More in vivo studies are needed for satisfactory results | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 75 | [94] | China | Silver- and zinc-doped silica nanoparticles synthesized using the sol-gel [Ag/Zn–SiO2 NPs (sol-gel)] | Metal/Biologically derived | S. aureus, E. faecalis | Experimental | Demonstrated antibacterial and antifungal properties against all the tested strains | Released Ag+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ ions damage bacterial membranes and inhibit growth | Ag- and Zn-doped silica NPs were found effective against periodontitis microbe | - | In vivo (animal model) |

| 76 | [95] | China | DMY-AgNPs (silver nanoparticles synthesized using dihydromyricetin) | Metal/Biologically derived | MRSA | Experimental | Showed the highest antibacterial activity with inhibition zones of 1.92 mm (S. aureus) and 1.75 mm (MRSA) | - | The antibacterial efficacy of DMY-AgNPs surpassed that of other green-synthesized AgNPs | High AgNPs concentrations impacted zebrafish embryo development | In vivo (animal model) |

| 77 | [96] | Pakistan | Levofloxacin loaded chitosan and poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid nano-particles (LVX-CS-III PLGA-I NPs) | Polymer-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Better antibacterial potency against gram+ve bacteria | CS-NPs enhance antibiotic delivery and pharmacokinetic profiles | Improved antibiotic sensitivity without compromising patient safety; enhanced zone of inhibition compared to free LVX | Conflicting reports exist on mass ratios affecting nanoparticle characteristics | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 78 | [97] | Pakistan | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | AgNPs exhibited significant antibacterial and antifungal activities | - | Aqueous extract of AgNPs provides a safer alternative to conventional antibacterial agents | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 79 | [98] | India | AgNP-antibiotic combinations (SACs) synthesized using Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619 | Metal-based | Enterococcus faecium, S. aureus | Experimental | SACs synergized with antibiotics, cutting required doses up to 32× and showing growth inhibition and bactericidal effects | AgNPs in SACs boost local Ag+ release, forming membrane pores, causing leakage, and killing bacteria | Up to 32-fold enhanced antibacterial activity, effective against biofilms, non-cytotoxic to normal cells | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 80 | [99] | China | Epigallocatechin gallate-ferric (EGCG-Fe) complex nanoparticles | Biologically derived | S. aureus | Experimental | Uses photothermal conversion to enhance antibacterial effects on S. aureus, prevent/destroy biofilms, and aid wound healing in vivo | Photothermal effect disrupts bacterial membranes and enhances antibacterial performance upon NIR laser irradiation | Shows photothermal enhanced antibacterial and wound healing effects compared to conventional agents | - | In vivo (animal model) |

| 81 | [100] | Argentina | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | AgNPs with a diameter of around 11 nm exhibited high antibacterial activity against both tested bacteria | The AgNPs increased intracellular ROS levels in both bacteria and caused membrane damage | AgNPs showed high antibacterial activity against S. aureus | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 82 | [101] | Saudi Arabia | AuNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Strong antimicrobial activity, especially at 20 µg/vol; inhibited Gram-positive bacteria | Nilavembu choornam-gold nanoparticles (NC-GNPs) disrupt bacterial membrane integrity, leading to cell death | NC-GNPs enhance drug efficacy and combat antibiotic resistance | Variations in drug delivery rates limit therapeutic efficacy | In vivo (animal model) |

| 83 | [102] | Indonesia | AuNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus and MRSA | Experimental | Showed antibacterial activity; higher metal ion levels increased efficiency | Damaged bacterial cell walls, disrupted metabolism, and ROS generation | - | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 84 | [103] | Bangladesh | Green synthesized chitosan nanoparticles (ChiNPs) | Biologically derived | S. aureus strains | Experimental | Reduced zones of inhibition against methicillin-resistant (mecA) and penicillin-resistant (blaZ) S. aureus | Positively charged nanomaterials interact with negatively charged bacterial cell walls through electrostatic interaction | - | The antiviral as well as antifungal activity of the yielded nanoparticles needs to be verified before field application | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 85 | [104] | New Zealand | AuNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus (MRSA ATCC 33593) | Experimental | Showed strong antimicrobial activity (0.13–1.25 μM), inhibited 90% of initial biofilms, and reduced 80% of preformed biofilms | - | The conjugates were stable in rat serum and not toxic to representative mammalian cell lines in vitro (≤ 64 μM) and in vivo (≤ 100 μM) | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 86 | [105] | Iraq | AgNPs | Metal-based | Streptococcus mitis | Experimental | Synergistic effect in the inhibition when combining AgNPs with some antibiotics | - | Clear synergistic effect in the inhibition of Streptococcus mitis | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 87 | [106] | Egypt | Streptomycin (Str) and Moringa oleifera leaf extract (MOLe)-loaded ZnONPs (Str/MOLe@ZnONPs) | Biologically derived | E. faecalis | Experimental | Strongly inhibited E. faecalis growth and biofilm formation | Enhance delivery by bacterial binding, blocking efflux pumps, and disrupting membranes | Nanoparticles enhance antibiotic binding to bacteria, improving efficacy | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 88 | [107] | China | Phenylboronic acid-functionalized BSA@CuS@PpIX (BSA@CuS@PpIX@PBA; BCPP) nanoparticles | Biologically derived | S. aureus | Experimental | BCPP exhibited good bacteria-targeting properties for both S. aureus | Produces ROS, amplifying Str’s bactericidal action | BCPP shows good hemocompatibility and low cytotoxicity compared to conventional agents | Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is restricted by poor photosensitizer solubility and a short half-life | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 89 | [108] | Egypt | TiO2, magnesium oxide (MgO), calcium oxide (CaO), and ZnO nanoparticles | Metal/Metal oxide-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Showed significant antibacterial effects, particularly MgO- and ZnO-hydrogel types | Generated free radicals and ROS that damage membranes, proteins, and DNA, causing bacterial death | Embedding nanoparticles in hydrogels prevents aggregation and boosts antibacterial synergy | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 90 | [109] | Egypt | Myricetin-coated zinc oxide/polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposites (MYR-loaded ZnO/PVA NCs) | Biologically derived | Clostridium (C.) perfringens | Experimental | C. perfringens isolates were most sensitive to MYR-loaded ZnO/PVA, with MICs of 0.125–2 μg/mL | MYR inhibits α-hemolysin-induced cell damage without inhibiting bacterial growth | Nanomaterials exhibit enhanced antimicrobial activity compared to conventional agents | In vivo studies are needed for validation | In vivo (animal model) |

| 91 | [110] | Egypt | Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CIP) encapsulated in PLGA nanoparticles coated with chitosan (CIP-CS-PLGA-NPs) | Polymer-based | E. faecalis | Experimental | Enabled controlled release, boosted antibacterial/antibiofilm effects, and improved healing | - | Exhibited greater antibacterial and anti-biofilm activity than free ciprofloxacin and calcium hydroxide | There is a need to link current findings to short- and long-term periapical healing | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 92 | [111] | Iran | Silver nanoparticles and propolis (AgNPs@propolis) | Biologically derived | S. aureus and E. faecalis | Experimental | Possesses a low toxic effect on the cell and has a high effect in inhibiting the growth of various bacteria | Membrane damage, energy transfer disruption, ROS generation, and toxic element release | Green synthesis reduces toxic effects compared to conventional methods | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 93 | [112] | Czech Republic | TiO2 NPs | Metal-oxide-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Offer a promising alternative to antibiotics, particularly for controlling MDR | Disrupts cell wall integrity, leading to cell death | TiO2 NPs exhibit enhanced antimicrobial properties against resistant strains | More studies are required to explore full applications and possible hazards | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 94 | [113] | Algeria | Silver carbonate nanoparticles (BioAg2CO3NPs) | Biologically derived | S. aureus | Experimental | Displayed good antibacterial and antibiofilm activity | Protein inactivation, production of ROS, and formation of free radicals | Pathogens fail to develop resistance to BioAg2CO3NPs, unlike conventional antimicrobials | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 95 | [114] | Turkey | Biogenic AgNPs | Biologically derived | S. aureus | Experimental | Showed antibacterial activity against S. aureus | - | The synergistic effects increased antibacterial effectiveness | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 96 | [115] | USA | PVP- or PEG-coated Ga2(HPO4)3 nanoparticles | Biologically derived | S. aureus | Experimental | Exhibit potent antimicrobial activity that is comparable to Ga(NO3)3 | - | Showed no bacterial resistance after 30 days, unlike Ga(NO3)3 and ciprofloxacin | Ineffective against Gram-positive S. aureus even at high concentrations | In vivo (animal model) |

| 97 | [116] | Ethiopia | Silver and cobalt oxide nanoparticles (Ag/Co3O4 NPs) | Metal-metal oxide-based | S. aureus and E. faecalis | Experimental | Showed promising antibacterial activities, with Ag NPs exhibiting the best inhibition | Disintegration of bacterial cell membranes results in pathogen death | High specific surface area of the nanoparticles enhances antibacterial performance | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 98 | [117] | Saudi Arabia | Saponin-derived AgNPs (AgNPs-S) | Biologically derived | MTCC-121 (B. subtilis), MTCC-439 (E. faecalis), and MTCC-96 (S. aureus) | Experimental | Exhibited potent antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria | Damaged bacterial membranes, causing DNA, RNA, and protein leakage | - | Further investigations to elucidate the possible mechanism involved and safety concerns | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 99 | [118] | USA | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Kenaf-based activated carbon (KAC)-chitosan (CS)-AgNPs exhibited a strong bactericidal effect with an MIC of 43.6 µg/mL for S. aureus | Disruption of bacterial cell walls, generation of ROS, interaction with sulfur and phosphorus of DNA, and cell death | Environmentally friendly synthesis method compared to conventional agents | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 100 | [119] | United Arab Emirates | CuO, ZnO, and tungsten trioxide (WO3) nanoparticles | Metal-oxide-based | S. aureus and MRSA | Experimental | Exhibited significant antimicrobial effects under dark incubation, while photoactivated WO3 NPs reduced viable cells by 75% | Lipid peroxidation due to ROS generation and cell membrane disruption, as shown by MDA production and live/dead staining | Nanomaterials exhibit > 90% antimicrobial activity at low concentrations | Varying results based on the NPs size | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 101 | [120] | Spain | AuNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | The antibiotic as an enhancer of amoxicillin was demonstrated, causing the precursors and the NPs to act quickly, and favor microbial death with a small amount of antibiotic | Internalization into bacteria, damage to the bacterial surface, production of ROS, and disruption of biosynthetic machinery led to microbial death | Acts quickly, favoring microbial death with a small antibiotic, thereby combating resistance and avoiding side effects derived from high doses | Further investigations to identify possible long-term adverse effects | In vivo (animal model) |

| 102 | [121] | Spain | Silver, gold, zinc, and copper nanoparticles (Ag, Au, Zn, and Cu NPs) | Metal-based | Enterococcus spp. | Experimental | Effectively inhibit planktonic cells and biofilm formation at low concentrations, affects preformed biofilms, and destabilizes their structure | - | Represent a good alternative to avoid the spread of MDR bacteria and minimize the selective pressure by systemic antibiotics or disinfectants | Further studies are required to confirm the compatibility and cytotoxicity of the most successful combinations | In vivo (animal model) |

| 103 | [122] | Egypt | Liposomal nanoparticles (LNPs) | Lipid-based | MRSA | Experimental | Combination therapies (AuNPs/AgNPs) and traditional antibiotics, provided enhanced antimicrobial efficacy and inhibited biofilm formation | - | This combination may overcome resistance and restore sensitivity in MDR bacteria | Further investigations are necessary to establish the safety and cytotoxicity profiles of these nanocomplexes | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 104 | [123] | Egypt | ZnONPs | Metal-oxide-based | Enterococcus spp. and MRSA | Experimental | Exhibited a synergistic antibacterial effect, showing enhanced inhibition compared to individual NPs | Based on the generation of ROS, leading to lipid peroxidation and membrane damage | Offers a non-toxic, non-invasive, and cost-effective alternative to conventional antimicrobials | Further in vivo investigations are required to validate the safety and efficacy | In vivo (animal model) |

| 105 | [124] | Australia | (Rif)-loaded MSN and organo-modified (ethylene-bridged) MSN (MON) | Inorganic based | S. aureus | Experimental | The combined effects reduced the CFU of intracellular SCV-SA 28 times and 65 times compared to MSN-Rif and non-encapsulated Rif, respectively | Increased uptake of MON is five-fold compared to MSN | MON reduced CFU of intracellular SCV-SA significantly compared to MSN-Rif | Further in vivo validation would be required | In vivo (animal model) |

| 106 | [125] | Spain | Silica MSNs | Inorganic-based | S. aureus and E. faecalis | Experimental | Displayed antibacterial activity against S. aureus with Ag-containing materials, showing the highest effectiveness | Bacterial death, including interactions with the outer and inner membranes, and alterations in the cytoplasmic membrane | Act as carriers of antibiotics, increasing their ability to penetrate the biofilm bacteria often developed to conventional antibiotics | Further in vivo studies will be necessary to validate their biomedical application | In vivo (animal model) |

| 107 | [126] | Romania | ZnO NPs | Metal-oxide-based | S. aureus | Experimental | The hydrogels containing 4% and 5% ZnO NPs, respectively, showed good antimicrobial activity | Direct contact of ZnO NP with the cell wall results in the bacterial cell’s integrity destruction and the release of antimicrobial ions (Zn2+ ions) | - | The biocomposites present some degree of toxicity towards HSF normal cells, depending on the quantity | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 108 | [127] | USA | AgNPs | Metal-based | MRSA | Experimental | Promising clinical application as a potential stand-alone therapy or antibiotic adjuvant | - | Synergy with clinically relevant antibiotics reduced the MIC of aminoglycosides by approximately 22-fold | Exhibits cytotoxicity, which could limit its application as a broad oral antimicrobial | Clinical |

| 109 | [128] | India | ZnO NPs | Metal-oxide-based | B. cereus | Experimental | Exhibited high antibiofilm activity against B. cereus with minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) of ZnO NPs at 46.8 µg/mL. Exhibited high antibiofilm activity against B. cereus with MBIC of ZnO NPs at 46.8 µg/mL and 93.7 µg/mL | ZnO NPs target the cell membrane-induced ROS generation as a bactericidal mechanism | ZnO NPs reduced the bacterial cell viability and eradicate the biofilms | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 110 | [129] | Saudi Arabia | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Enhanced antibacterial activity by increasing inhibition zones and reducing MIC values compared to lincomycin or AgNPs alone | The ROS, along with free radicals, damaged the bacterial cell wall and also inhibited the respiratory enzymes | Enhanced antibacterial efficacy compared to lincomycin alone, reducing MIC and increasing inhibition zone diameters | Lincomycin has restricted Gram-positive antibacterial activity and is developing resistance | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 111 | [130] | Iran | Ag Np conjugated to chitosan (Ag Np and Chitosan Np | Inorganic metal-based | MRSA | Experimental | Ag Np-chitosan exhibits great antibacterial and anti-biofilm effects against CRAB and MRSA isolates | - | Ag Np-chitosan conjugation, an ideal alternative for ineffective antibiotics | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 112 | [131] | Saudi Arabia | CNPs | Polymer-based | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Experimental | Enhanced antibacterial activity compared to C3-005 alone | C3-005 reduces ATP generation in Streptococcus pneumoniae | Precise mechanism of haemolysis reduction by CNPs has not been determined | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 113 | [132] | Saudi Arabia | AgNPs | Metal-based | MRSA | Experimental | Exhibited high antimicrobial activity and a synergistic effect with penicillin against MRSA strains | AgNPs enhance antibiotic efficiency through synergistic effects with penicillin | AgNPs exhibited high antimicrobial activity and a synergistic effect with penicillin against MRSA strains | Phenotype from healthcare-associated (HA)-MRSA lacks plasmid DNA, limiting resistance understanding | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 114 | [133] | China | AgNPs | Metal-based | Streptococcus suis | Experimental | Significantly inhibited the growth of MDR Streptococcus suis, disrupted bacterial morphology and cell walls, and destroyed biofilm structures | ROS overproduction inhibited peptidoglycan biosynthesis, downregulated bacterial division proteins, and interfered with quorum sensing | AgNPs are effective against MDR bacteria, unlike conventional antibiotics | Insufficient antioxidant enzyme expression to eliminate excessive ROS effectively | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 115 | [134] | South Korea | C2-coated ZnONPs (C2-ZnONPs) | Inorganic based | S. aureus | Experimental | C2-ZnONPs inhibited biofilm and virulence of S. aureus | Lam-AuNPs disrupt mature biofilm structures in a dose-dependent manner | Lam-AuNPs effectively control biofilm and virulence in pathogens | The need to unravel the molecular mechanism of biofilm and virulence attenuation | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 116 | [135] | USA | Ag NPs | Metal based | S. aureus | Experimental | Ag NPs do not exhibit cytotoxicity up to 50 µg/mL in each solution | - | Ag NPs/methylene blue (MB) were shown to be more effective than MB and Ag NPs alone | To evaluate its effectiveness against pathogens that cause prosthetic joint infection | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 117 | [136] | China | Ti3C2Tx MXene loaded with indocyanine green nanoparticles (ICG@Ti3C2Tx MXene NPs) | Biologically derived | Streptococcus mutans | Experimental | ICG-MXene under NIR irradiation killed MRSA; no antibacterial effect without NIR | Combination of the photothermal effect of MXene and the photodynamic effect of ICG | ICG-MXene has a great synergistic PTT/PDT effect against MRSA | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 118 | [137] | India | Zn and Mg substituted β-tricalcium phosphate/functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotube (f-MWCNT) nanocomposites | Metal based | MRSA | Experimental | The in-vitro cell viability and anti-biofilm results of zinc (5%) rich nanocomposite confirmed that prepared nanocomposite has biocompatible and enhanced anti-biofilm property, which will be beneficial candidate for biomedical applications | - | Nanocomposites have the ability to enhance the bioactivity of commercial antibiotics by means of a decrease in drug resistance | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 119 | [138] | Jordan | Tryasine-AgNPs | Metal-based/biologically derived | MRSA | Experimental | More effective with MICs ranging from 30 to 100 µM, while at 100 µM caused only 1% haemolysis on human erythrocytes after 30 min of incubation | Tryasine enters the bacterial cell wall outer membrane, increasing its permeability, and the antibiotic impact of AgNPs | Strong activity against resistant bacteria while exhibiting low haemolytic activity and cytotoxicity | Potential toxicity not extensively evaluated beyond hemolytic assay | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 120 | [139] | Iraq | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus, S. epidermidis | Experimental | Broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. Synergistic effect with multiple antibiotics, increasing the inhibition fold area | Generation of ROS, disruption of the electron transport chain, decreased ATP levels, interference with the plasma membrane, and inhibition of DNA unwinding | Synergistic combination of AgNPs with conventional antibiotics enhances antibacterial efficacy against resistant strains | Further investigations (e.g., checkerboard assay, cytotoxicity, and blood compatibility studies) are required | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 121 | [140] | Saudi Arabia | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus, S. saprophyticus, S. sciuri, and S. epidermidis | Experimental | AgNPs (15–25 nm) were not effective against Gram-positive strains (MIC 256 μg/mL). | AgNPs mediate antimicrobial effects via the generation of ROS, direct interaction with and rupture of bacterial membranes | Enhances antimicrobial efficacy, reduces required antibiotic doses, and minimizes toxicity against AMR strains | To evaluate potential cytotoxicity and confirm in vivo effectiveness | In vivo (animal model) |

| 122 | [141] | Turkey | Ag–Pt nanoparticles | Metal based | S. aureus, B. subtilis, S. epidermidis | Experimental | Antimicrobial activity at 25, 50, and 100 µg/mL, with 100 µg/mL achieving low bacterial viability (22.58–29.67%) | Oxidative dissolution leads to the release of silver ions (Ag+), which initiates the antibacterial effect | Propolis in nanoparticle synthesis helps prevent industrial synthesis methods that consume more resources and induce side effects | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 123 | [142] | Brazil | Biogenically synthesized silver nanoparticles using Fusarium oxysporum (BioAgNP) | Biologically derived | MRSA | Experimental | BioAgNP and thymol exhibited synergistic antibacterial activity, inhibited biofilm, and prevented the development of MDR | Membrane disruption, leakage of intracellular contents, oxidative stress (ROS, lipid peroxidation) | Combination prevented resistance development, faster antibacterial action, and reduced MIC values | Limited to specific bacterial strains tested in the study. | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 124 | [143] | South Korea | Thymol-zinc oxide nanocomposite (ZnO NCs) | Metal oxide/biologically derived | Staphylococcus spp. | Experimental | Highly selective and bactericidal against S. epidermidis; MIC 2–32-fold lower than THO alone | Membrane rupture, suppression of biofilm, modulation of cell wall and protein synthesis pathways | Bioconjugation improves the efficacy of natural antibacterial compounds | Thymol has low antibacterial activity and non-selectivity | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 125 | [144] | Saudi Arabia | Chitosan silver and gold nanoparticles (CS-Ag-Au NPs) | Metal/Polymer-based | B. subtilis and S. aureus | Experimental | Chitosan (Ch)-AgNPs showed strong antibacterial and antibiofilm activities; ch-AuNPs showed moderate to weak activity | Biofilm formation aids bacterial colonization on surfaces | Biogenic nanoparticles do not require rigorous conditions for synthesis like conventional agents | - | In vivo (animal model) |

| 126 | [145] | Mexico | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Increased susceptibility to antibiotics by 20% (without efflux effect) and 3% (with efflux effect). Decreased isolates with efflux effect by 17.5% | Decreases the portion of bacterial isolates exhibiting efflux activity, indirectly restoring antibiotic susceptibility | AgNPs can restore antibiotic activity and reduce treatment duration | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 127 | [146] | India | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Best synergistic antibacterial activity against planktonic S. aureus despite lower drug release compared to AgNP-trisodium citrate (TSC)-tannic acid (TA) | AgNPs with mupirocin and antibiofilm agents enhance activity against S. aureus | Nanoparticles enhance antibiotic concentrations at infection sites | - | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 128 | [147] | Jordan | Tobramycin-chitosan nanoparticles (TOB-CS NPs) coated with zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) | Biologically derived | S. aureus | Experimental | Enhanced antimicrobial activity against S. aureus compared to TOB-CS NPs or ZnO NPs alone | Generated oxidative stress and damage bacterial membranes; TOB inhibits protein synthesis | Nanoparticles can improve drug entrapment efficiency significantly | No MIC data for S. aureus ATCC 29215 was found | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 129 | [148] | Saudi Arabia | Ceftriaxone-loaded gold nanoparticles (CGNPs) | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | Showed MIC50 values 2× lower compared to pure ceftriaxone and enhanced antibacterial potency | CGNPs increase ceftriaxone concentration by attachment | CGNPs showed two times better antibacterial efficacy compared to pure ceftriaxone | In vivo studies on CGNPsʼ fate and toxicity are needed | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 130 | [149] | Czech Republic | AgNPs | Metal-based | S. aureus | Experimental | TMPyP and AgNPs showed a synergistic antimicrobial effect, a promising alternative against MDR | Penetrate the bacterial cell and release Ag ions, which attack the respiratory chain, sulfur-containing proteins, and phosphorus-containing compounds such as DNA | Effective fight against MDR | lack of development in new molecules with antibacterial properties | Preclinical (unspecified) |

| 131 | [150] | Iran | Zinc sulfide (ZnS) nanoparticles | Metal-based | Streptococcus pyogenes | Experimental | Antibacterial effects dependent on concentration; 150 μg/mL had the highest antibacterial effect | - | Nanoparticles exhibit enhanced antibacterial effects compared to conventional agents | - | In vivo (animal model) |

-: No details. MDR: multidrug-resistant; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; XRD: X-ray diffraction patterns; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; TEM: transmission electron microscopy.

Nanomaterials were classified as metallic (AgNPs, AuNPs, CuO NPs, ZnO NPs), polymeric (chitosan, PLGA), lipid-based (liposomes, solid lipid NPs), and carbon-based (graphene oxide, CNTs) [11, 15]. AgNPs, often metal-based and being the most frequently reported in over 50 studies, exhibited strong bactericidal and antibiofilm activity via ROS production, membrane disruption, and interference with bacterial metabolism [26, 29, 31–34, 39, 57, 68, 114, 146]. AuNPs, frequently functionalized or combined with drugs, enhanced antimicrobial and wound-healing potential [21, 34, 40, 63, 67, 72, 101]. ZnO NPs and Cu/CuO NPs demonstrated ROS-mediated antibacterial and antibiofilm effects, often synergistic with antibiotics [73, 78, 94, 119, 121]. Some studies explored hybrid or functionalized nanomaterials with advanced properties. For example, MXF@UiOUBIPEGTK, a biologically derived ROS-responsive system, enabled targeted drug release in oxidative infection environments [52]. Polymeric nanoparticles, including chitosan and PLGA-based formulations, offered controlled antibiotic release and improved biofilm inhibition, supporting long-term antimicrobial therapy [108]. Collectively, these nanomaterials enhanced antibacterial effectiveness, often achieving substantial bacterial suppression at low antibiotic doses, thus mitigating resistance development, demonstrating broad-spectrum activity, and reducing high-dose side effects. Notably, biogenic CuNPs and ZnO NPs exhibited strong synergistic activity against MRSA, producing significantly larger inhibitory zones against Gram-positive pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, S. saprophyticus, S. sciuri, and S. epidermidis [28, 42, 46, 123, 127, 132, 142, 146, 149]. Biologically derived AgNPs, including CAgNPs, disrupted biofilms in both S. aureus and MRSA strains, highlighting their potential in treating chronic Gram-positive infections [30, 138].

Nanoparticles exert antimicrobial and therapeutic effects against Gram-positive bacteria through multiple physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms (Table 1). The most frequently reported mechanism is bacterial membrane disruption, which increases permeability, causes leakage of cytoplasmic components (e.g., DNA, ions, proteins), and ultimately leads to cell lysis [20, 29, 31, 37, 45, 60, 61]. ROS generation is another key mechanism, inducing oxidative stress that damages lipids, proteins, and DNA, resulting in significant bacterial mortality [24, 31, 42, 86, 93, 100, 113, 118, 140]. Intracellular interference by nanoparticles can inhibit replication, transcription, and protein synthesis, often through DNA interaction or ATP depletion [50, 69, 125]. Some nanoparticles disrupt bacterial enzymes and metabolic pathways, causing energy depletion and cell death [24, 139]. For biofilm prevention and eradication, particularly in persistent infections like MRSA, nanoparticles prevent surface adhesion, degrade the EPS matrix, and downregulate biofilm-associated genes [31, 47, 52, 133, 146]. Stimulus-responsive drug delivery allows nanoparticles to release therapeutic agents in response to bacterial cues such as enzymes, pH, enhancing specificity and minimizing side effects [30, 71, 74]. The release of metal ions (Ag+, Zn2+, Cu2+) further disrupts thiol-containing proteins, inhibits enzymes, and generates ROS, intensifying antibacterial activity [33, 80, 94, 98, 149]. Additionally, some nanoparticles cause localized physical damage via photothermal or electromagnetic effects, leading to protein denaturation and membrane rupture [60, 99, 136].