Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, Diponegoro University, Semarang 50275, Indonesia

Email: agustina.aminin@live.undip.ac.id

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3422-0872

Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, Diponegoro University, Semarang 50275, Indonesia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-4103-7796

Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, Diponegoro University, Semarang 50275, Indonesia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-2516-0062

Affiliation:

1Department of Chemistry, Diponegoro University, Semarang 50275, Indonesia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9786-124X

Affiliation:

2Department of Pharmacy, Hazara University, Mansehra 21120, Pakistan

Email: ajmalshah@hu.edu.pk

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3471-184X

Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2025;5:1004135 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2025.1004135

Received: September 15, 2025 Accepted: December 16, 2025 Published: December 30, 2025

Academic Editor: Marcello Iriti, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

The article belongs to the special issue Natural Products in Neurotherapeutic Applications

Aim: Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, are strongly associated with amyloid-β aggregation. This study aimed to explore bioactive metabolites from endophytic bacteria as potential anti-aggregation agents with relevance to neuroprotection, focusing on isolate D11 obtained from a geothermal fern at Gedong Songo hot springs.

Methods: Isolate D11 was characterized by Gram staining and 16S rRNA sequencing. Growth curve analysis was conducted to determine metabolite production phases. Phytochemical screening, bovine serum albumin (BSA) aggregation inhibition assays, liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy (LCMS) profiling, and molecular docking against amyloid-β were employed to evaluate bioactivity and metabolite composition.

Results: D11 was identified as a Gram-negative rod with 97.94% similarity to Stutzerimonas stutzeri. Metabolite production peaked during the stationary and death phases. Phytochemical tests revealed alkaloids and tannins in aqueous fractions. BSA aggregation inhibition assays demonstrated potent inhibitory activity, with IC50 values (2.40–3.29 µg/mL) significantly lower than quercetin. LCMS profiling identified diverse metabolites, dominated by flavonoid glycosides such as kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside, along with alkaloids, peptides, and diterpenoids. Molecular docking confirmed strong binding affinities of flavonoid glycosides to amyloid β (–7.6 kcal/mol), outperforming quercetin (–6.0 kcal/mol).

Conclusions: These findings suggest that isolate D11 Stutzerimonas produces bioactive metabolites with anti-aggregation activity and potential relevance to neuroprotection. However, since Stutzerimonas-derived metabolites remain poorly explored and the docking results are tentative, further in-depth characterization and in vivo validation are required to confirm their therapeutic relevance, and further validation using amyloid-β or α-synuclein models is required to confirm therapeutic implications.

Neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), represent a growing global health burden with limited therapeutic options. A central pathological hallmark of these disorders is protein aggregation, involving amyloid-β (Aβ), tau, and α-synuclein fibrils that drive neuronal dysfunction and progressive cognitive decline [1, 2]. Consequently, inhibiting or reversing aggregation has become a critical therapeutic strategy in the search for neuroprotective agents.

Natural products are widely recognized as valuable sources of amyloid aggregation inhibitors. Polyphenols such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and flavonoids from medicinal plants have demonstrated the ability to block fibrillation, remodel amyloid structures, and mitigate oxidative stress associated with neurodegeneration [3–5]. Recent studies have also highlighted peptide-based inhibitors and metal-chelating natural compounds as promising anti-aggregation candidates [6]. These findings suggest that structurally diverse metabolites from natural sources may provide leads for future anti-neurodegenerative therapies.

Beyond higher plants, endophytic microorganisms have emerged as underexplored reservoirs of bioactive metabolites with neuroprotective potential. For example, metabolites from endophytic Fusarium spp. were shown to disaggregate α-synuclein oligomers and alleviate oxidative stress in a yeast model of PD [7]. Comprehensive reviews have documented more than 468 metabolites from endophytic fungi with reported anti-Alzheimer’s activity, spanning alkaloids, polyketides, terpenoids, and peptides [8]. In parallel, endophytic bacteria isolated from medicinal plants such as Hoya multiflora and Rauvolfia serpentina have been reported to produce strong antioxidant and antibacterial metabolites, detectable by liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy (LCMS) profiling [9, 10].

Among potential host plants, ferns (pteridophytes) represent an ancient lineage of vascular cryptogams with global distribution (> 10,000 species) and remarkable ecological adaptability [11]. Unlike seed plants, ferns reproduce via spores and exhibit alternation of generations, with the sporophyte as the dominant phase and a free-living gametophyte [12]. Their evolutionary success in diverse and sometimes extreme habitats suggests a symbiotic reliance on microbial partners, including endophytes that may enhance stress tolerance and contribute bioactive metabolites [13, 14].

Despite the increasing recognition of endophytes as biofactories, geothermal ferns and their associated microbiota remain largely unexplored. Extreme environments such as hot springs exert selective pressures that may drive microorganisms to evolve unique biosynthetic pathways, leading to metabolites with enhanced or novel pharmacological activities [15].

Endophytic bacteria from plants inhabiting extreme ecosystems have attracted increasing attention due to their potential to produce unique secondary metabolites with ecological and biomedical relevance [16]. Ferns, as primitive vascular plants, represent an underexplored host group, particularly those thriving in geothermal environments, where oxidative and thermal stresses shape microbial adaptation. In our preliminary survey of geothermal fern endophytes of Gedong Songo hot springs, multiple isolates exhibited measurable protein anti-aggregation activity (unpublished data), with the D11 isolate showing the highest activity and selected for further study. Building upon these findings, the present study focuses on the detailed phylogenetic identification, secondary metabolites were assessed for anti-aggregation activity, supported by LCMS metabolite profiling and in silico molecular docking. This study aims to characterize geothermal fern-associated endophytic bacteria as a novel source of anti-aggregation metabolites, using a bovine serum albumin (BSA) denaturation model as an initial screening tool to indicate potential relevance toward neuroprotective applications.

The production of metabolites from isolate D11 was initiated by preparing an endophytic bacterial starter culture. A single bacterial ose was inoculated into 50 mL of nutrient broth and incubated in a rotary shaker at 125 rpm at room temperature until reaching the logarithmic growth phase. Subsequently, 0.5 mL of the starter culture was transferred into 250 mL of fresh nutrient broth and incubated at room temperature for an incubation period determined based on the previously established growth curve, resulting in an endophytic bacterial isolate culture. The culture was centrifuged at 4,227× g for 10 min to separate the supernatant from the cell pellet. The obtained supernatant was then concentrated at 70°C for approximately 54 h, yielding a concentrated extract of endophytic bacterial metabolites [17].

The extraction and fractionation of endophytic bacterial secondary metabolites were carried out. A total of 100 mL of concentrated metabolite extract was fractionated sequentially using solvents of different polarities, n-hexane, ethyl acetate, and distilled water, with a 1:1 solvent-to-extract ratio. The extract was first partitioned with n-hexane in a separatory funnel, shaken for 5 min, and allowed to separate into two phases; the process was repeated three times. The aqueous fraction was subsequently partitioned with ethyl acetate under the same conditions, also repeated three times. Each obtained fraction (n-hexane, ethyl acetate, and aqueous) was collected separately for further analysis [18].

Phenotypic characterization of isolate D11 was carried out based on a modified method of Nuritasari et al. [19]. Gram staining was performed using endophytic bacterial cultures previously isolated from geothermal plant samples. Microscope slides were cleaned with 70% ethanol and air-dried, after which a loopful of bacterial culture was smeared and heat-fixed over a Bunsen flame. The slides were then sequentially stained with crystal violet (1 min), rinsed with distilled water, treated with iodine (1 min), rinsed, decolorized with 96% ethanol (30 s), rinsed again, and counterstained with safranin (1 min) before a final rinse. The stained preparations were observed under a light microscope. Cells appearing purple to blue were classified as Gram-positive, while those appearing red were classified as Gram-negative.

Genotypic identification of the endophytic bacterial isolate D11 was carried out based on 16S rRNA gene analysis, which included DNA isolation and purification, quantification, amplification, sequencing, and phylogenetic tree construction [20]. Genomic DNA was extracted from bacterial culture using a modified protocol [21]. The purified DNA was quantified using an ultraviolet (UV)-Vis spectrophotometer at 260 nm and 280 nm to determine concentration and purity. Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was performed by PCR using universal primers 27F (5’-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3’) and 1492R, with cycling conditions consisting of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 45 s), annealing (54°C, 1 min), extension (72°C, 1.5 min), and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were confirmed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel stained with fluorosafe dye and visualized under UV illumination. The purified amplicons were then subjected to sequencing, and both forward and reverse reads were assembled to obtain a consensus sequence. Sequence identification was carried out using basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) against the NCBI database to determine the closest homologous taxa. For phylogenetic analysis, the obtained sequences were aligned with reference sequences using ClustalW in MEGA version 11 software, and phylogenetic trees were constructed with the Neighbor-Joining method supported by bootstrap analysis, providing an overview of the evolutionary relationship of isolate D11 with related bacterial species.

Qualitative phytochemical tests were carried out on crude and fractionated extracts to detect major secondary metabolites (alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, phenolics, terpenoids) following standard colorimetric protocols, followed method by Farnsworth [22]. All reagents used in phytochemical tests were sourced from Merck (Germany).

The presence of alkaloids was examined using Dragendorff’s (Merck, Cat. No. 44578, Germany) and Mayer’s reagents (Merck, Cat. No. 221090, Germany), with caffeine serving as the positive control. A total of 1 mL of extract solution was mixed with 1 mL of chloroform and 10 drops of 2 mol/L HCl. The mixture was gently shaken and allowed to separate. The upper aqueous layer was divided into two test tubes:

Dragendorff test:

Three drops of Dragendorff’s reagent were added. The formation of an orange precipitate, comparable to the caffeine control, indicated a positive result.

Mayer test:

Three drops of Mayer’s reagent were added. The appearance of a yellowish-white precipitate, matching the caffeine control, indicated a positive result.

Flavonoid detection was performed using the magnesium-HCl reduction test, with quercetin as the positive control. To 0.5 mL of extract, several milligrams of magnesium powder and 2–3 drops of concentrated HCl were added. After vigorous shaking, the development of red, yellow, or orange coloration, similar to the quercetin control, was interpreted as a positive result.

Tannin screening used tannic acid as the positive control. To 1 mL of extract, 2 drops of gelatin solution, and several drops of NaCl solution were added. The formation of a white precipitate, consistent with the tannic acid control, indicated the presence of tannins.

Phenolic compounds were tested using FeCl3, with gallic acid as the positive control. To 1 mL of extract, 3 drops of 1% FeCl3 solution were added. The appearance of a dark green coloration, similar to the gallic acid control, was taken as a positive result.

Terpenoid detection employed the Liebermann-Burchard reaction, with tartaric acid extract serving as the positive control. The extract was evaporated on a water bath to dryness. Then, 4 drops of anhydrous acetic acid and 2 drops of concentrated H2SO4 were added. The development of a brownish coloration, comparable to the positive control, indicated the presence of terpenoids.

Anti-aggregation activity of secondary metabolites derived from endophytic bacteria was evaluated following the procedure described by Truong et al. [23]. The assay was performed using turbidimetry by adding 200 μL of the bacterial secondary metabolite extract into the test vessel, followed by the addition of 1 mL of BSA (Merck, Cat. No. A7030, Germany) 1,000 ppm. The mixture was then incubated in a water bath at 70–80°C for 90 min to induce BSA denaturation. After incubation, absorbance was measured at 600 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to monitor changes in the optical spectrum. Inhibition (%) was calculated relative to the untreated control.

The anti-aggregation assay using turbidimetry was further supported by the Congo red dye (Merck, Cat. No. 75768, Germany) binding method followed Holm et al. [24]. A 20 μL of the Congo red 20 ppm solution was added to the BSA protein aggregation together with the sample used in the turbidimetric assay. The protein solution was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. This step was conducted to monitor optical spectrum changes resulting from the interaction between the secondary metabolite extract and Congo red within the protein solution.

Secondary metabolite analysis was performed using a liquid chromatography system coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS/MS) on an LC NEXERA X2 connected to an LCMS (Shimadzu, 8060, Japan) using an InertSustain C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 µm). The system was equipped with a single mass detector (MS) operating in positive ionization mode (E+). Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water, and solvent B was 0.1% formic acid in methanol. Solvents were set at a total flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. An isocratic elution system was run at 0–0.5 min with a ratio of 95:5; linear gradient of solvent A was from 95% to 5% in 15 min. Data acquisition was conducted by monitoring the total ion chromatogram (TIC) over an m/z range of 1–1,000, enabling the detection and characterization of metabolites based on retention time and mass-to-charge ratio (m/z).

Molecular docking was performed following a previously reported protocol with minor modifications [25]. The three-dimensional structure of Aβ42 fibril (PDB ID: 5OQV) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank, with a single chain selected for docking, water molecules removed, and polar hydrogens as well as Kollman charges added before saving in PDBQT format. Ligand structures identified from LCMS analysis were retrieved from PubChem in SDF format, converted to PDB using Open Babel. Docking was performed using AutoDock Vina (version 1.1.2) through PyRx (version 0.8). Blind docking has been used for this method. The grid box was centered at the coordinates (x = 38.6598, y = 60.0364, z = 53.5879) with dimensions (size x = 35.994 Å, size y = 46.7367 Å, size z = 15.5034 Å) covering all the surface of the protein and docked with AutoDock Vina in PyRx 0.8. Binding affinities (kcal/mol) were recorded, and interaction analyses in BIOVIA Discovery Studio (version 24.0.1) identified hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts, with ligands forming at least two hydrogen bonds and showing favorable binding energy, considered as potential amyloidosis inhibitors.

Gram staining and morphological characterization revealed that the endophytic bacterial isolate D11 was Gram-negative with a bacillus-like (rod-shaped) morphology (Figure S1). Under microscopic observation at 1,000× magnification, the cells appeared red, confirming their Gram-negative status, which is attributed to the high lipid content in the outer membrane. Macroscopic examination showed that isolate D11 produced yellow colonies with a streptobacillus form, wavy and small margins, and a flat elevation. These combined phenotypic characteristics provide a clear profile of isolate D11.

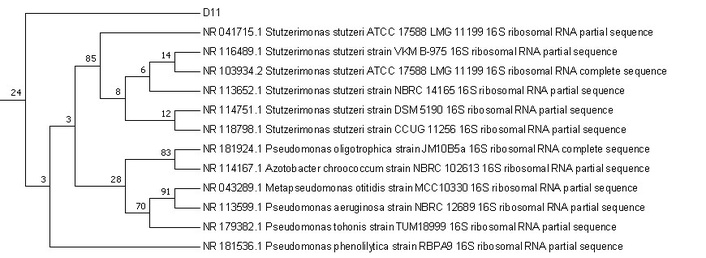

The 16S rRNA gene sequence (~1,450 bp) of isolate D11 showed 97.94% similarity to Stutzerimonas stutzeri (S. stutzeri) in NCBI BLAST analysis. Phylogenetic tree construction confirmed its clustering within the Stutzerimonas clade, supported by a bootstrap value of 99%, indicating high reliability of classification.

As shown in Figure 1, isolate D11 is similar to S. stutzeri ATCC. Stutzerimonas is a recently proposed genus within the family Pseudomonadaceae, delineated based on core-genome phylogeny and phenotypic characteristics [26]. This genus includes species that were previously classified under Pseudomonas, with S. stutzeri corresponding to the former Pseudomonas stutzeri group. S. stutzeri is an opportunistic pathogen widely distributed in diverse environments and is characterized by remarkable metabolic versatility, including denitrification and nitrogen fixation. These traits enable S. stutzeri to play an important role in the oceanic nitrogen cycle through the conversion of nitrogen oxides into atmospheric nitrogen [27]. Considering its ecological significance, studies have also highlighted the importance of investigating the phage genomics and ecology of S. stutzeri, although to date only two cultivated phages infecting this species have been reported [28].

Phylogenetic tree of isolate D11. Phylogeny based on 16S rRNA sequences obtained from isolates and the NCBI database, performed using the Maximum Likelihood method with the Jukes–Cantor model. Associated taxa were grouped in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates), and bootstrap values were greater than 50%. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA version 11 software.

The placement of isolate D11 within the genus Stutzerimonas suggests that it may share similar functional traits, particularly the ability to produce bioactive secondary metabolites. The yellow-orange pigmentation observed in D11 cultures further supports this, as pigment production in Stutzerimonas has been linked to ecological adaptation and secondary metabolism. Taken together, the genomic identification highlights D11 as a strain closely related to S. stutzeri, with potential ecological and biotechnological relevance.

The production of secondary metabolites was carried out at the stationary and death phases of bacterial growth to evaluate their bioactivity. These harvest times were selected based on the growth curve analysis of isolate D11, which showed that secondary metabolite production began at the stationary phase and reached its maximum during the death phase (Figure 2).

Figure 2 shows the growth curve of endophytic bacterium isolate D11. The logarithmic phase occurred from 0 to 8 h, characterized by rapid cell division supported by abundant nutrients. The stationary phase, observed from 8 h to 16 h, indicated a balance between cell division and death due to nutrient limitation and accumulation of metabolic byproducts, during which secondary metabolite production typically begins. A decline in absorbance after 16 h marked the death phase as nutrients were depleted. For this study, secondary metabolites were harvested at 12 h [extract 12 h (E12)] and 24 h [extract 24 h (E24)], representing the stationary and death phases, respectively. Although direct quantification of metabolite yield was not performed at each phase, the selection of E12 and E24 was based on preliminary observations showing increased absorbance intensity during these phases, which suggests enhanced secondary metabolite accumulation.

Based on Table 1, phytochemical screening was conducted to identify the types of secondary metabolites present in the extracts of endophytic bacterium D11 across different solvent fractions, namely aqueous, ethyl acetate, and n-hexane. The results (Table 1) revealed the presence of alkaloids in the aqueous fraction for both D11-E12 and D11-E24, indicating that polar alkaloids were predominantly extracted in this fraction. The ethyl acetate fraction showed the presence of tannins in both harvest times, reflecting their solubility in semi-polar solvents. In the n-hexane fraction, alkaloids were also detected in D11-E12 and D11-E24, suggesting the presence of non-polar alkaloids. Overall, the main metabolites detected were polar and non-polar alkaloids, with the aqueous fraction exhibiting a stronger alkaloid intensity compared to the n-hexane fraction. Since alkaloids and tannins are reported to possess neuroprotective and anti-aggregation activities, the aqueous fraction obtained was subsequently subjected to anti-aggregation assays to evaluate their biological potential.

Screening phytochemicals of D11.

| Fraction | Extract | Phytochemical | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloid | Flavonoid | Tannin | Terpenoid | Phenolic | ||

| Control | Not applicable | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Aquadest | D11-E12 | + | - | - | - | - |

| D11-E24 | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Ethyl acetate | D11-E12 | - | - | + | - | - |

| D11-E24 | - | - | + | - | - | |

| n-heksane | D11-E12 | + | - | - | - | - |

| D11-E24 | + | - | - | - | - | |

++: strong presence; +: weak presence; –: absence of the compound; E12: extract 12 h; E24: extract 24 h.

To quantitatively evaluate the anti-aggregation potency of each extract, IC50 values were determined using a dose-response analysis. The inhibition curves were fitted using a four-parameter logistic (4PL) nonlinear regression model in OriginPro 8.5 SR1 (OriginLab Corporation), which estimates the top response, bottom response, Hill coefficient, and the concentration required to achieve 50% inhibition (IC50). All assays were performed using three independent biological replicates (n = 3), and the resulting IC50 values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) to reflect true biological variability.

Based on Table 2, the anti-aggregation activity of the aqueous fractions (E12 and E24) was assessed using both turbidimetric and Congo Red assays. At concentrations of 1–5 ppm, the aqueous extract E12 inhibited BSA aggregation by 77.7 ± 0.396%, while E24 achieved 79.4 ± 0.606% inhibition at 5 ppm. The IC50 values were 3.00 ± 1.09 µg/mL (E12) and 2.40 ± 0.11 µg/mL (E24), which were significantly stronger than the quercetin control (IC50 = 28.37 µg/mL). This demonstrates that D11-derived compounds are more potent aggregation inhibitors compared to standard flavonoids.

Anti-aggregation assay of isolate D11.

| Extract/Control | Inhibition (turbidimetry)IC50 (µg/mL) | Inhibition (Congo Red)IC50 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| E12 | 3.00 ± 1.09 | 3.29 ± 0.06 |

| E24 | 2.40 ± 0.11 | 2.99 ± 0.06 |

| Quercetin (control) | 28.37 ± 2.15 | 47.06 ± 3.62 |

IC50 values were derived from four-parameter logistic (4PL) nonlinear regression in OriginPro and are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates); E12: extract 12 h; E24: extract 24 h.

Similarly, the Congo Red assay revealed that at 1–5 ppm, E12 inhibited fibril formation by 67.4 ± 0.837%, while E24 showed 66.1 ± 0.65% inhibition at 5 ppm. The IC50 values were 3.29 ± 0.06 µg/mL (E12) and 2.99 ± 0.06 µg/mL (E24), again substantially stronger than the quercetin control (IC50 = 47.06 µg/mL). These results further confirm that the extracts exert strong inhibitory effects against amyloid fibril formation, exceeding the activity of the flavonoid standard.

Analysis of the LCMS data revealed the presence of diverse secondary metabolites, including peptides, flavonoid glycosides, alkaloids, and diterpenoids.

Based on Table 3, LCMS analysis of the active fraction revealed several metabolites eluting between 13.494- and 16.782-min. Absolute quantification of each metabolite was not performed; however, peak area (%) based on TIC was included to represent comparative levels. The chromatographic profile showed distinct peaks corresponding to different molecular ions. The most prominent peak appeared at a retention time of 15.665 min with an experimental m/z of 494, corresponding to Hymenotamayonin F, a diterpenoid compound, with 10.67% relative abundance. Two additional peaks with experimental m/z values of 636 were detected at retention times of 14.517 min and 16.782 min, both tentatively identified as Kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside, classified as flavonoid glycosides, with 8.95% and 7.82% relative abundance, respectively. Other minor compounds were also detected, including Carmaphycin B [experimental m/z 533, theoretical m/z 532; retention time (RT) 13.494 min; 5.61%] from the peptide epoxyketone group, and Epicatechocorynantheine B (experimental m/z 658, theoretical m/z 657; RT 14.878 min; 4.03%), belonging to the flavo-alkaloid class. These findings indicate that the fraction consists of several secondary metabolites representing diterpenoid, flavonoid, peptide, and alkaloid classes.

LCMS profiling the metabolite of D11.

| Retention time (min) | m/z Experimental (base peak) | m/z Theoretical | Peak area (%) | Compound name | Compound class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13.494 | 533 | 532 | 5.606 | Carmaphycin B | Peptide epoxyketone |

| 14.517 | 636 | 635 | 8.949 | Kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside | Flavonoid glycoside |

| 14.878 | 658 | 657 | 4.028 | Epicatechocorynantheine B | Flavo-alkaloid |

| 15.665 | 494 | 493 | 10.672 | Hymenotamayonin F | Diterpenoid |

| 16.782 | 636 | 635 | 7.818 | Kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside | Flavonoid glycoside |

Molecular docking analysis of secondary metabolites derived from the endophytic bacterial extract D11 suggested potential interactions with the Aβ protein, a key target in amyloidosis.

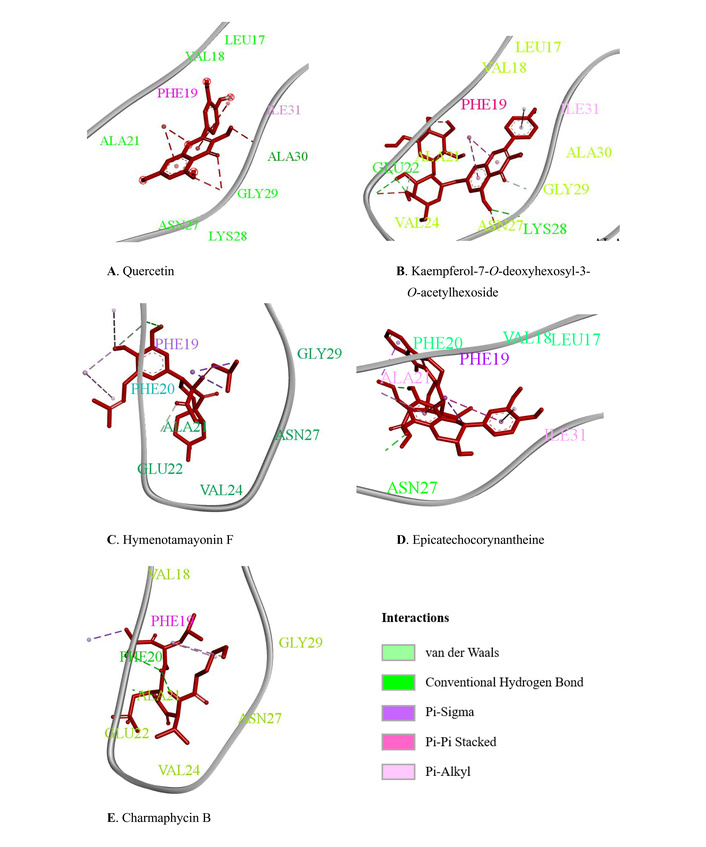

As shown in Table 4 and Figure 3, in silico molecular docking results demonstrated that the five ligands exhibited varying binding affinities toward the Aβ protein. Quercetin showed a binding energy of –6.0 kcal/mol with a hydrogen bond at ALA 30 and hydrophobic interactions with PHE 13 and ILE 31. The stability of the complex was further supported by van der Waals interactions involving LYS 28, GLY 29, ASN 27, ALA 21, VAL 12, and LEU 17. Carmaphycin B exhibited a binding affinity of –5.6 kcal/mol, forming a hydrogen bond with PHE 20 and hydrophobic interactions with PHE 19, which also suggests potential aromatic interactions. Additional van der Waals contacts were observed at VAL 18, ALA 21, GLY 29, ASN 27, VAL 24, and GLU 22, stabilizing the ligand within the binding pocket.

Molecular Docking analysis of metabolite D11.

| No. | Molecule | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen interaction | Hydrophobic interaction | Van der walls interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quercetin | (–6.0) | ALA 30 | PHE 13, ILE 31 | LYS 28, GLY 29, ASN 27, ALA 21, VAL 12, LEU 17 |

| 2 | Carmaphycin B | (–5.6) | PHE 20 | PHE 19 | VAL 18, ALA 21, GLY 29, ASN 27, VAL 24, GLU 22 |

| 3 | Kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside | (–7.6) | GLU 22, LYS 28 | PHE 19, ILE 31, | ALA 21, VAL 24, ASN 27, GLY 29, ALA 30, LEU 17, VAL 18 |

| 4 | Hymenotamayonin F | (–7.0) | VAL 18 | PHE 19,PHE 20 | ALA 21, VAL 24, GLY 29, ASN 27 |

| 5 | Epicatechocorynantheine B | (–6.7) | ASN 27 | ILE 31, ALA 21, PHE 19 | VAL 18, LEU 17, ALA 39, PHE 20 |

Docking performed using AutoDock Vina (version 1.1.2) via PyRx (version 0.8; http://pyrx.sourceforge.net/).

Ligand-beta amyloid binding visual. (A) Quercetin (Control positive), (B) Kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside, (C) Hymenotamayonin F, (D) Epicatechocorynantheine, (E) Charmaphycin B.

Kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside displayed the strongest binding energy of –7.6 kcal/mol, with hydrogen bonding interactions at GLU 22 and LYS 28. Hydrophobic interactions were found with PHE 19 and ILE 31, while van der Waals interactions included ALA 21, VAL 24, ASN 27, GLY 29, ALA 30, LEU 17, and VAL 18, indicating a strong binding orientation toward the target protein.

Hymenotamayonin F exhibited a binding affinity of –7.0 kcal/mol, forming a hydrogen bond at VAL 18. Hydrophobic interactions involved PHE 19 and PHE 20, with PHE 19 contributing to π–π stacking, which is important for stabilizing aromatic interactions. Additional van der Waals contacts with ALA 21, VAL 24, GLY 29, and ASN 27 further strengthened the ligand-protein complex.

Meanwhile, Epicatechocorynantheine B showed a binding energy of –6.7 kcal/mol with a hydrogen bond at ASN 27. Hydrophobic contacts were observed with ILE 31, ALA 21, and PHE 19, with PHE 19 again suggesting π–π stacking interactions. Van der Waals interactions with VAL 18, LEU 17, ALA 39, and PHE 20 contributed to the overall stabilization of the binding.

It should be noted that these in silico findings are still tentative, serving as preliminary predictions of ligand–protein interactions, and therefore require further experimental validation to confirm their biological relevance.

The anti-aggregation activity demonstrated in this study was based on a BSA denaturation model, which represents a generalized form of protein aggregation. While it provides a useful preliminary indication of anti-aggregation potential, it does not replicate the specific fibrillization process of Aβ or α-synuclein. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted as demonstrating general anti-aggregation capacity with possible relevance to neuroprotective mechanisms, pending validation in disease-specific models. The translation of these in vitro and in silico findings into therapeutic relevance in vivo remains to be established. Although the inhibitory effects observed here suggest potential neuroprotective activity, further studies are required to determine their biological efficacy and safety under physiological conditions. Evaluation of cytotoxicity on neuronal or glial cells, as well as assessment of pharmacological parameters in animal models, would be essential to confirm both the therapeutic potential and biosafety of D11-derived metabolites.

The characterization of isolate D11 as a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium with yellow pigmented colonies strongly suggested its affiliation with metabolically versatile environmental bacteria. Molecular identification through 16S rRNA analysis confirmed this, with isolate D11 showing 97.94% similarity to S. stutzeri. The phylogenetic clustering within the Stutzerimonas clade further validated this classification. This finding is significant since S. stutzeri is recognized for its ecological role in the nitrogen cycle and for its ability to synthesize diverse secondary metabolites [27]. The pigmentation observed in D11 cultures aligns with previous reports linking pigment production in Stutzerimonas to ecological adaptation and secondary metabolism [26].

The growth curve analysis of D11 demonstrated that secondary metabolite production coincided with the stationary and death phases, a common feature in bacterial metabolism where biosynthetic gene clusters are activated under nutrient limitation. Accordingly, extracts collected at 12 hours (E12, stationary phase) and 24 hours (E24, death phase) were screened for secondary metabolites. Phytochemical analysis revealed the predominance of alkaloids in both aqueous and n-hexane fractions, along with tannins in the ethyl acetate fraction. Alkaloids and tannins are well-documented for their neuroprotective and anti-amyloidogenic properties, making these metabolites particularly relevant for amyloid-related pathologies such as AD.

The anti-aggregation assays provided strong evidence of bioactivity. Both aqueous fractions (E12 and E24) demonstrated potent inhibitory effects against protein aggregation, with IC50 values significantly lower than that of the positive control quercetin in both turbidimetric and Congo Red assays. Notably, the activity was stronger at the death phase (E24), suggesting that extended culture may favor the accumulation of aggregation inhibitors. However, since the BSA-based system models general protein aggregation rather than amyloid-specific fibrillation, additional validation using Aβ or α-synuclein aggregation models would provide stronger mechanistic insight. In particular, fluorescence-based assays such as Thioflavin T (ThT) binding or morphological visualization through transmission electron microscopy (TEM) could directly demonstrate the suppression of fibril formation. Such analyses would be valuable for confirming whether D11-derived compounds act by preventing nucleation, elongation, or destabilization of amyloid aggregates. These results highlight the potential of D11-derived compounds as more effective aggregation inhibitors than conventional flavonoids, positioning this isolate as a promising source of anti-amyloidogenic metabolites.

LCMS profiling of D11 extracts identified a diverse set of secondary metabolites, including peptides (Carmaphycin B), flavonoid glycosides (Kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside), flavo-alkaloids (Epicatechocorynantheine B), and diterpenoids (Hymenotamayonin F). The predominance of flavonoid glycosides, particularly Kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside, with the largest peak area, suggests that flavonoid-derived compounds are the major bioactive constituents of D11. Given that flavonoids and alkaloids are repeatedly linked to neuroprotective effects, this chemical profile supports the observed anti-aggregation activity in vitro. Beyond flavonoids, other detected metabolites may also contribute to the observed bioactivity. Carmaphycin B, a peptide originally reported from marine actinomycetes, is known for its proteasome-inhibitory and cytoprotective properties, which could indirectly modulate protein homeostasis and aggregation pathways. Epicatechocorynantheine B, a flavo-alkaloid with both flavonoid and indole structural features, has been associated with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects that may further enhance neuronal resilience. Meanwhile, Hymenotamayonin F, a diterpenoid, could play a supporting role through membrane-stabilizing or radical-scavenging mechanisms. The coexistence of these structurally diverse compounds suggests a possible synergistic interaction in maintaining proteostasis and mitigating aggregation stress. Such chemical diversity highlights the metabolic versatility of S. stutzeri D11 and supports the potential for discovering multiple classes of neuroprotective metabolites within a single strain.

In silico molecular docking analysis further strengthened these observations. The Aβ42 fibrillar protein (PDB ID: 5OQV) was selected for molecular docking because Aβ42 is the most aggregation-prone and neurotoxic isoform of Aβ, and its fibrillar conformation represents the pathological structure predominantly found in Alzheimer’s plaques [6]. Using this well-characterized fibrillar model enables evaluation of ligand interactions with disease-relevant β-sheet surfaces and ensures consistency with the amyloid-specific Congo Red assay performed in vitro [29]. Kaempferol-7-O-deoxyhexosyl-3-O-acetylhexoside exhibited the strongest binding affinity (–7.6 kcal/mol) to Aβ, followed by Hymenotamayonin F (–7.0 kcal/mol) and Epicatechocorynantheine B (–6.7 kcal/mol). These interactions were stabilized by hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, and aromatic π–π stacking, which are critical for preventing amyloid aggregation. Although quercetin is widely recognized as a standard anti-aggregation flavonoid, its binding affinity was lower than that of D11-derived compounds.

This study was conducted using crude extracts, and the metabolites detected by LCMS were present only in trace quantities, precluding their isolation and direct biological evaluation. Accordingly, molecular docking was employed strictly as a predictive tool to identify metabolites that may plausibly contribute to the observed anti-aggregation activity, rather than as evidence of mechanistic confirmation. Future work will involve scaling up the cultivation of isolate D11, purifying the predominant metabolites (e.g., kaempferol derivatives, Hymenotamayonin F, and Epicatechocorynantheine), and subjecting each compound to amyloid-specific assays, including ThT fluorescence kinetics (Aβ42), α-synuclein aggregation models, Congo Red spectral analysis, and TEM. These efforts will enable direct verification of their putative anti-amyloidogenic properties.

Integration of LCMS profiling, in vitro aggregation assays, and molecular docking provides preliminary support for the hypothesis that S. stutzeri D11 produces bioactive flavonoid and alkaloid metabolites with anti-aggregation potential. Nevertheless, the attribution of biological activity to specific metabolites remains tentative and requires validation using purified compounds in established Aβ and α-synuclein assay systems. Collectively, these findings establish a conceptual framework for identifying the molecular constituents underlying the anti-aggregation effects of isolate D11 and guiding future neuroprotective investigations.

In summary, the endophytic bacterial isolate D11 was successfully characterized as a Gram-negative, rod-shaped strain closely related to S. stutzeri based on phenotypic traits and 16S rRNA gene analysis. Growth curve evaluation indicated that secondary metabolite production was initiated during the stationary phase and peaked in the death phase. Phytochemical screening revealed the presence of alkaloids and tannins, both known for their neuroprotective potential. Anti-aggregation assays demonstrated that aqueous fractions obtained from D11 exhibited potent inhibitory activity against protein aggregation, with IC50 values substantially lower than the standard quercetin control. LCMS profiling identified diverse secondary metabolites, predominantly flavonoid glycosides, alongside alkaloids, peptides, and diterpenoids, supporting the observed bioactivities. In silico docking further confirmed the strong binding affinities of key metabolites, particularly kaempferol derivatives, toward Aβ, suggesting their role in preventing amyloid fibril formation. these findings indicate that geothermal fern-associated endophytes can generate metabolites with potential neuroprotective relevance. However, the interpretation remains preliminary due to the nonspecific nature of the BSA model, necessitating validation in Aβ-based systems to establish direct neuroprotective effects.

AD: Alzheimer’s disease

Aβ: amyloid-β

BLAST: basic local alignment search tool

BSA: bovine serum albumin

E12: extract 12 h

E24: extract 24 h

LCMS: liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy

PD: Parkinson’s disease

S. stutzeri: Stutzerimonas stutzeri

TEM: transmission electron microscopy

ThT: Thioflavin T

TIC: total ion chromatogram

UV: ultraviolet

The supplementary figure for this article is available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1004135_sup_1.pdf.

We sincerely thank Universitas Diponegoro for its World-Class University Program and the Adjunct Professor Program 2025 for their valuable academic support. Finally, we extend our appreciation to the researchers and colleagues who contributed technical and intellectual assistance throughout this study.

ALNA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing—original draft. RS: Writing—original draft, Data curation, Investigation. BFAk: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. MA: Software, Writing—review & editing, Data curation. MAS: Writing—original draft, Data curation. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Faculty of Science and Mathematics, Universitas Diponegoro, Indonesia, through the research grant [25.I.A/UN7.F8/PP/II/2024]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 526

Download: 20

Times Cited: 0

Leonel Pereira, Ana Valado

Sharon Smith ... David Heal

Prerna Sarup ... Sonia Pahuja

Ekaterina P. Krutskikh ... Artem P. Gureev

Susmita Das ... Shylaja Hanumanthappa

Sneha Bagle ... Sadhana Sathaye

Luis Antonio Ramirez-Contreras ... Andrés Frausto de Alba