Affiliation:

1Department of Biomedical, Morphological and Functional Imaging Sciences, University of Messina, 98125 Messina, Italy

Email: rafabio@unime.it

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7065-1528

Affiliation:

2Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, 98125 Messina, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1860-8079

Affiliation:

1Department of Biomedical, Morphological and Functional Imaging Sciences, University of Messina, 98125 Messina, Italy

Affiliation:

2Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, 98125 Messina, Italy

Affiliation:

3Institute for Cognitive and Brain Sciences (ICBS), Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran 1983969411, Iran

Affiliation:

2Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, 98125 Messina, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9327-0119

Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2025;5:1004134 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2025.1004134

Received: October 10, 2025 Accepted: November 12, 2025 Published: December 30, 2025

Academic Editor: Michele Roccella, University of Palermo, Italy

The article belongs to the special issue Advances in the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Aim: This study examined differences in attentional control and awareness of interference among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), children with subthreshold ADHD (children showing some but not all symptoms required for diagnosis), and children with typical development. Specifically, we investigated how visual and auditory distractions affect behavioral performance and eye movements, to clarify the degree and nature of attentional control impairments associated with subthreshold versus clinically diagnosed ADHD.

Methods: One hundred and two children (mean age = 7.23 years, SD = 1.23; 34 per group) participated in three eye-tracking tasks involving a bouncing ball under no, visual, and auditory interference. Behavioral accuracy (number of correctly counted bounces), fixation duration on the target, gaze reorientation latency, and distractor awareness were analyzed using mixed-design analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and chi-square tests.

Results: Significant group differences were found in counting accuracy, F(2, 99) = 16.42, p = 0.00069, η2p = 0.245, with typically developing children performing best, followed by those with subthreshold and full ADHD. Eye-tracking indices showed a similar gradient: fixation duration decreased with symptom severity, F(4, 198) = 7.65, p = 0.00094, η2p = 0.134, while gaze reorientation latency increased, F(2, 99) = 12.18, p = 0.00093, η2p = 0.197 (typical development ≈ 480 ms; subthreshold ≈ 621 ms; ADHD ≈ 721 ms). Awareness of distractors also varied significantly across groups, χ2(2, n = 102) = 38.12, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.61, with detection rates of approximately 80% (typical development), 50% (subthreshold), and 25% (ADHD).

Conclusions: Both children with ADHD and children with subthreshold ADHD show measurable deficits in attentional control and awareness of interference, particularly under visual and auditory distraction. Children with subthreshold ADHD exhibited an intermediate profile, supporting a continuum rather than a categorical distinction in cognitive control impairments. These findings highlight the importance of early identification and interventions targeting attentional regulation and metacognitive monitoring across the ADHD spectrum.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition marked by persistent inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity, leading to learning, behavioral, and socio-emotional difficulties [1–7]. Beyond clinically diagnosed ADHD, subthreshold forms have been described, characterized by the presence of core ADHD symptoms that do not fully meet diagnostic criteria [8, 9].

Although less severe, subthreshold ADHD affects a larger proportion of children (approximately 17%) than clinical ADHD (about 9%) [10, 11], and is associated with similar but milder impairments in academic, social, and emotional functioning [12–14].

These findings suggest that core cognitive difficulties are shared between clinical and subthreshold ADHD, warranting further investigation of the underlying mechanisms [15, 16]. A central domain of impairment in ADHD is cognitive control—the set of executive processes regulating attention and behavior according to goals [17–20].

These functions depend on three attentional networks: alerting, orienting, and executive control, which respectively enhance sensitivity to stimuli, select relevant information, and resolve conflict [20–24]. Deficits in these systems increase susceptibility to interference and impair sustained attention, leading to poorer performance on both visual and auditory tasks compared with typically developing (TD) peers [25–28]. Some evidence suggests that children with subthreshold ADHD may also exhibit impairments in executive attentional control, though the extent and nature of these deficits remain unclear [12, 29]. A related aspect is interference awareness, defined as the ability to recognize distractors and modulate behavior adaptively [30]. In children with ADHD, interference awareness appears reduced [31–33], potentially explaining everyday difficulties in managing competing stimuli.

However, it remains unclear whether children with subthreshold ADHD show a similar pattern.

The Cumulative and Emergent Automatic Deficit (CEAD) model [34, 35] explains attentional and executive difficulties in ADHD as resulting from inefficient automatization of basic processes. Such inefficiency increases cognitive load and weakens higher-order control, leading to greater interference susceptibility and reduced interference awareness. Complementary models of cognitive control deficits emphasize impairments in executive functions such as working memory, response inhibition, and set-shifting [36, 37], which limit the ability to maintain task-relevant information and suppress irrelevant input [32]. Together, these frameworks describe attentional control as a continuum: children with ADHD show pronounced deficits, those with subthreshold ADHD exhibit intermediate difficulties [29, 38], and TD peers display efficient automatization and robust executive control [39].

Based on the theoretical framework and previous empirical findings on attentional control and interference processing in ADHD, the present study aimed to examine whether children with subthreshold ADHD exhibit deficits in attentional control and interference awareness under both visual and auditory interference, comparable to those observed in children with ADHD, using an eye-tracking paradigm.

Two main hypotheses were formulated.

Hypothesis 1. Consistent with prior research documenting attentional control deficits in children with ADHD, it was hypothesized that children with ADHD would exhibit greater susceptibility to interference compared with TD peers. Specifically, under conditions involving both visual and auditory distractors, children with ADHD were expected to demonstrate poorer behavioral performance, as indexed by a lower number of correctly counted ball bounces, less efficient allocation of attention—reflected by shorter mean fixation durations on the target—and slower reorientation of gaze following distractor onset, as measured by increased latency to return to the ball. Children with subthreshold ADHD were anticipated to show a similar but attenuated pattern, exhibiting intermediate levels of performance, fixation duration, and gaze reorientation latency, suggesting that attentional control difficulties exist along a continuum from TD children to clinical ADHD.

These predictions integrate both overt behavioral measures and underlying attentional allocation processes, providing a comprehensive assessment of interference susceptibility.

Hypothesis 2. It was further hypothesized that conscious awareness of interference—the ability to recognize the influence of distracting stimuli on one’s performance—would differ significantly across groups. Children with ADHD were expected to report the distractor correctly less frequently during the 15-s pauses following each trial, reflecting limited metacognitive monitoring of attentional lapses.

Children with subthreshold ADHD were anticipated to show intermediate awareness, identifying distractors more often than clinical ADHD participants but less consistently than TD children. TD children were predicted to display the highest levels of interference awareness, indicating more effective self-regulation and monitoring of attentional performance.

Together, these hypotheses link behavioral accuracy, eye-tracking indices, and self-reported awareness, providing a multidimensional understanding of interference processing across the ADHD continuum.

One hundred and two children (mean age = 7.23 years, SD = 1.23) participated in the study: 34 with ADHD, 34 with subthreshold ADHD, and 34 TD peers, matched for age, gender, and IQ. The study employed a cross-sectional design, comparing attentional and metacognitive performance across the three groups.

Participants were selected from a larger pool of 680 children attending two public primary schools in Calabria, Italy. Initial screening was based on teacher ratings using the ADHD Rating Scale–IV: School Version (SDAI) [40] and the Disruptive Behavior Disorder Rating Scale (SCOD) [41]. Children scoring above the clinical cutoff (> 14) on the hyperactivity and/or inattention subscales of the SDAI were considered at risk for ADHD. Comorbid conditions were excluded by ensuring SCOD scores were within the normal range and that participants had age-appropriate cognitive abilities, as assessed by the Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM) [42, 43]. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) confirmed no significant differences in IQ across groups, F(2, 99) = 0.06, p = 0.94, partial eta squared (η2p) = 0.001.

Following this screening, 102 children were divided into three groups: ADHD-combined subtype (ADHD-C) (n = 34; 19 males, 15 females), subthreshold ADHD (n = 34; 18 males, 16 females), and TD controls (n = 34; 18 males, 16 females).

Children with ADHD met full Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria for the combined presentation (ADHD-C), confirmed by a licensed clinician based on parent and teacher reports on the ADHD Rating Scale–5 [44] and a structured clinical interview.

The inclusion of only the combined type ensured a homogeneous clinical sample exhibiting both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, particularly relevant to the study’s focus on attentional control. Children with predominantly inattentive (ADHD-I) or predominantly hyperactive/impulsive (ADHD-H) presentations were excluded to reduce heterogeneity and avoid confounding the assessment of executive attentional control and interference awareness [36, 45]. Children in the subthreshold ADHD group exhibited clinically relevant symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity but did not meet full DSM-5 criteria. Specifically, subthreshold ADHD was defined by the presence of three to five symptoms in either domain on the ADHD Rating Scale–5, as reported by both parents and teachers, along with evidence of functional impairment in at least one major setting (home or school), indicated by elevated scores on the Child Behavior Checklist [46] or equivalent teacher report. This operationalization follows established research practices for identifying subthreshold ADHD [47–49].

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Psychological Research of the University of Messina (protocol n. 314/25, approved on March 12, 2025).

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all participants prior to testing.

An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 [50] to determine the minimum required sample size for the mixed-design ANOVAs (3 groups × 3 conditions). Following Cohen’s [51] (1988) conventions and previous ADHD research, a medium effect size (f = 0.25) was assumed, with α = 0.05 and power (1–β) = 0.80.

The assumption of a medium effect was based on two considerations.

First, Cohen [51] (1988) defines f = 0.25 as a medium effect size for ANOVA, which is a standard and conservative assumption in behavioral research when precise population estimates are unavailable. Second, meta-analytic findings on cognitive and attentional control in ADHD report group differences of medium magnitude [45], supporting the plausibility of effects in this range for behavioral and eye-tracking measures. Thus, f = 0.25 represents a theoretically and empirically grounded estimate for detecting clinically meaningful group differences.

Based on these parameters, the required total sample size was n = 84 (actual sample = 102, Table 1), indicating that the study was adequately powered to detect medium-sized effects.

Demographic characteristics of the three groups participating in the experiment.

| Groups (n = 102) | Measures | Values |

|---|---|---|

| ADHD-C (n = 34) | n, boys/girls | 19/15 |

| Age, M (SD) | 7.21 (1.24) | |

| IQ (Raven), M (SD) | 102.00 (5.24) | |

| SDAI–inattention, M (SD) | 19.60 (2.50) | |

| SDAI–hyperactivity, M (SD) | 18.10 (2.30) | |

| Subthreshold ADHD (n = 34) | n, boys/girls | 18/16 |

| Age, M (SD) | 7.25 (1.22) | |

| IQ (Raven), M (SD) | 102.10 (9.10) | |

| SDAI–inattention, M (SD) | 15.90 (2.50) | |

| SDAI–hyperactivity, M (SD) | 11.80 (1.60) | |

| TD (n = 34) | n, boys/girls | 18/16 |

| Age, M (SD) | 6.99 (1.20) | |

| IQ (Raven), M (SD) | 105.50 (7.95) | |

| SDAI–inattention, M (SD) | 2.00 (0.20) | |

| SDAI–hyperactivity, M (SD) | 3.00 (0.31) |

ADHD-C: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-combined subtype; SDAI: ADHD Rating Scale–IV: School Version; TD: typically developing.

Disattention and hyperactivity rating scale (SDAI). The Italian adaptation of SDAI [40] is used to screen for ADHD symptoms in school-aged children. It consists of two subscales, inattention (I) and hyperactivity (H), each comprising nine items.

Items are rated on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (never or rarely) to 3 (very often).

Total scores for each subscale range from 0 to 27, with a cutoff of 14.

Children exceeding the cutoff on the inattention subscale are classified as ADHD-I, those exceeding only the hyperactivity subscale as ADHD-H, and those exceeding both as ADHD-C. In the present sample, only ADHD-C was considered.

Psychometric evidence indicates high test-retest reliability over one month (r = 0.95) and high internal consistency (α = 0.98), supporting the scale’s reliability [40].

Aggressive behavior rating scale (SCOD). The Italian adaptation of SCOD [41] is used to assess disruptive behaviors and learning difficulties in school-aged children.

It comprises 13 items divided into a Disruptive Behavior Disorder index (8 items) and a Learning Problems index (5 items), covering both linguistic and mathematical areas.

Items are rated on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (never or rarely) to 3 (very often).

Total scores range from 0 to 24 for the Disruptive Behavior Disorder subscale (cutoff = 12) and 0 to 15 for the Learning Problems subscale (cutoff = 8).

Psychometric evidence indicates good test-retest reliability over one month (r = 0.92 for the Disruptive Behavior Disorder subscale and r = 0.89 for the Learning Problems subscale) and high internal consistency (α = 0.88 and 0.86), supporting the scale’s reliability [41].

RPM. The RPM test is a widely used tool for assessing cognitive abilities, primarily measuring fluid intelligence. Its utility stems from its relative insensitivity to socio-cultural factors, such as environmental context and educational level. The test consists of a sequence of diagrams or matrices composed of abstract geometric figures, each missing a specific element.

The standard version is divided into five sets (A to E), with increasing levels of complexity, totaling 60 items (12 per set). Participants are required to identify the underlying pattern or rule in the arrangement of figures and select the appropriate figure from the provided options to complete the series [42, 43].

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV). The DISC-IV is a structured diagnostic interview designed to assess psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents according to DSM-5 criteria [52]. Parallel versions exist: a parent version (children aged 6–17) and a youth version (9–17 years).

In this study, the parent version of the ADHD module was used, which includes two subsections: inattention (DISC-IA) and hyperactivity–impulsivity (DISC-HI).

Each subsection includes information on the age of onset and daily functioning.

The interview evaluates the presence of sufficient symptoms across two or more settings and their impact on daily activities.

Responses are processed by a scoring program to determine whether diagnostic criteria are met, reporting symptom counts, criteria met, and functional impairment.

For this study, the impairment criterion was defined as one severe or at least two moderate impairments across six domains of daily functioning [52].

Eye-tracking. Visual attention and reaction times were assessed using a Tobii Pro X3-120 remote eye tracker. This device records eye movements non-invasively, allowing natural interaction with stimuli [53]. It has a sampling rate of 120 Hz and monocular accuracy of approximately 0.34°, providing reliable measurements of fixations, saccades, and reaction times in brief visual tasks.

Individual calibration was performed using a nine-point protocol. Eye-tracking data were synchronized with experimental videos and distractors, enabling assessment of attentional control, selective attention, and distractor awareness [54].

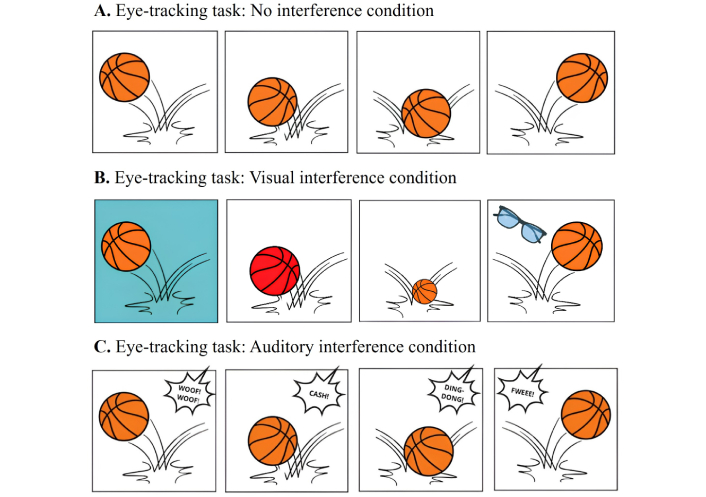

Task. Children’s attentional performance was assessed using a video-based eye-tracking task adapted from previous studies on attentional control in children with ADHD [55, 56]. Each participant was tested individually in a quiet, distraction-free room and seated comfortably in front of the display. Prior to data collection, the eye tracker was calibrated to ensure accurate gaze tracking. The task consisted of three short video clips depicting a bouncing ball, corresponding to three experimental conditions: no interference, visual interference, and auditory interference (Figure 1). Each trial contained 20 bounces, with each bounce lasting 1.5 s, for a total trial duration of 30 s. After each trial, a 15-s pause was introduced, during which the experimenter asked children whether they had noticed any changes in the stimuli, providing an index of distractor awareness (Figure 2).

Stimuli and experimental conditions in the eye-tracking task. Each trial displayed a short video of a basketball bouncing vertically, while participants’ gaze was recorded to assess attention tracking. The task included three conditions: (A) No interference, where the ball bounced against a plain background; (B) visual interference, where distracting visual elements (changes in background and ball color, ball size, or presence of objects such as glasses) appeared during the bounce; and (C) auditory interference, where concurrent environmental sounds (e.g., dog bark, glass breaking, bell ringing, whistle) were presented. Each trial consisted of 20 bounces occurring every 1.5 s. The figure illustrates the temporal structure of each trial and the types of interference introduced in each condition. This task aimed to measure participants’ ability to maintain visual attention on the moving target despite competing sensory distractions. Basketball icon made by Ahmad Yafie from https://www.flaticon.com/free-icon/basketball_10823177?term=basketball&page=1&position=19&origin=tag&related_id=10823177; glasses icon made by DinosoftLabs from https://www.flaticon.com/free-icon/glasses_1804202?term=glasses&page=2&position=79&origin=search&related_id=1804202.

Duration of each task in the experimental trial. The sequence of tasks was presented in a randomized order across participants.

In the visual interference condition, distractors included changes in background color, ball color, variations in ball size, and appearance of objects.

In the auditory interference condition, distractors included sounds such as a dog barking, a glass breaking, a bell ringing, and a whistle.

The no interference condition presented the ball bouncing without any additional visual or auditory stimuli.

Each participant completed one trial per condition, with the order of conditions randomized across participants. Eye-tracking data were collected throughout each trial to measure fixation duration on the ball, latency to return gaze to the ball after distractor onset, and overall attentional allocation.

Latency to return gaze to the ball after distractor onset represents the efficiency of attentional reorientation following distraction, measured from the onset of the distractor to the first fixation on the target. Distractors were presented for 500 ms, a duration consistent with previous studies on attentional reorientation in children [57], which reported mean gaze return latencies in the range of 400–750 ms under similar interference conditions.

This design allowed for the simultaneous assessment of behavioral performance (number of correctly counted bounces) and both implicit and explicit awareness of distractors.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants prior to data collection, which took place between February and May 2024.

All assessments were administered by a trained experimental psychologist during school hours (9:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.). Before beginning the experimental task, the examiner verified that all children could count to 100 and accurately track moving objects. Participants then received standardized instructions, and the eye-tracking system was individually calibrated. Following calibration, participants completed the three video trials according to the protocol described above. The order of the three conditions was counterbalanced across participants using a Latin-square design to control for potential order and fatigue effects.

After each trial, a brief post-trial interview assessed whether participants noticed any changes or unusual events, providing additional information on conscious detection of distractors. All procedures were standardized to ensure consistency across participants and to minimize potential confounding variables. The total session, including instructions, calibration, task completion, and pauses, lasted approximately 5 min per participant.

Eye-movement data were recorded using a Tobii Pro X3-120 remote eye tracker, sampling at 120 Hz. Raw gaze data were preprocessed and analyzed using Tobii Pro Lab software (version 1.230) [58]. Fixations were detected using a velocity-threshold identification (I-VT) algorithm with a velocity threshold of 30°/s and a minimum fixation duration of 60 ms, following standard recommendations for child samples [59]. Blinks and signal losses were automatically identified and removed by the software. Trials with more than 30% missing gaze samples (due to blinks or loss of tracking) were excluded from further analysis. All participants retained at least 70% of valid gaze data across the task, and thus no participant was excluded based on data quality criteria. Data quality was visually inspected to confirm accurate calibration and the absence of systematic drifts. Fixation metrics (e.g., fixation count, mean fixation duration, first fixation latency) were computed within predefined areas of interest (AOIs) corresponding to the target and distractor stimuli. These measures were exported to SPSS for subsequent statistical analyses.

Behavioral and eye-tracking data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.

To test Hypothesis 1 (interference susceptibility) and explore attentional allocation, a 3 (group: TD, subthreshold ADHD, ADHD) × 3 (condition: no, visual, auditory interference) mixed-design ANOVA was conducted separately for each dependent variable: the number of correctly counted ball bounces, mean fixation duration on the ball (ms), and latency to return gaze to the ball after distractor onset (ms). Group was treated as a between-subjects factor, and condition as a within-subjects factor. Sphericity was assessed using Mauchly’s test, and Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied when necessary. Significant main effects and interactions were followed up with Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons. Effect sizes were reported using η2p for ANOVA and Cohen’s d for post hoc comparisons. To address potential type I error inflation due to multiple correlated dependent variables (e.g., behavioral and eye-tracking measures), a multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) was conducted as a sensitivity analysis.

The dependent variables included the number of correctly counted bounces, mean fixation duration, proportion of trial time fixating the target, and latency to return gaze to the target following distractor onset. Multivariate effects were assessed using Wilks’ λ, and significant effects were followed by univariate ANOVAs with Bonferroni correction to examine the contribution of individual dependent variables. To examine Hypothesis 2 (interference awareness), the number of children correctly detecting distractors during the 15-s pause after each trial was analyzed using chi-square tests of independence. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction were conducted to identify differences between groups.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was determined using a p-value threshold of p < 0.05; Bonferroni-adjusted p-values were used for post hoc comparisons where applicable. Descriptive statistics (mean and SD) were reported for all dependent variables. When appropriate, post hoc tests were accompanied by effect sizes (Cohen’s d) to quantify the magnitude of group differences [53]. Eye-tracking data were preprocessed to remove blinks and invalid samples. Mean fixation duration on the ball was computed for each trial, and the proportion of the trial spent fixating on the ball was calculated as the total fixation time on the ball divided by the total trial duration, expressed as a percentage.

Latency to return gaze to the ball after distractor onset was measured from the onset of the distractor to the first fixation on the ball, exceeding 100 ms. These measures provided convergent evidence regarding attentional allocation and reorientation efficiency across groups and conditions.

A 3 (group: TD, subthreshold ADHD, ADHD) × 3 (condition: no, visual, auditory interference) mixed-design ANOVA was conducted to examine Hypothesis 1, evaluating both behavioral performance (number of correctly counted bounces) and attentional allocation via eye-tracking. There was a significant main effect of group on bounce counts, F(2, 99) = 16.42, p = 0.00069, η2p = 0.245. Post hoc comparisons indicated that TD children performed best, children with subthreshold ADHD showed intermediate performance, and children with ADHD performed lowest (Table 2).

Mean (± SD) of correctly counted ball bounces across groups and conditions.

| Conditions | TD(n = 34) | Subthreshold ADHD(n = 34) | ADHD(n = 34) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No interference | 18.5 (1.8) | 16.5 (2.0) | 15.8 (2.1) |

| Visual interference | 14.2 (1.5) | 11.5 (1.7)* | 10.8 (1.9)* |

| Auditory interference | 13.0 (1.6) | 9.8 (1.8)* | 8.5 (1.5)* |

*: p < 0.05 vs. TD. TD: typically developing; ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

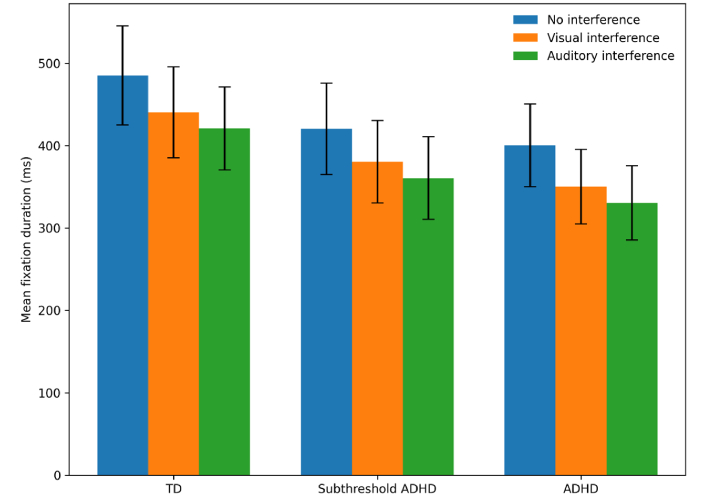

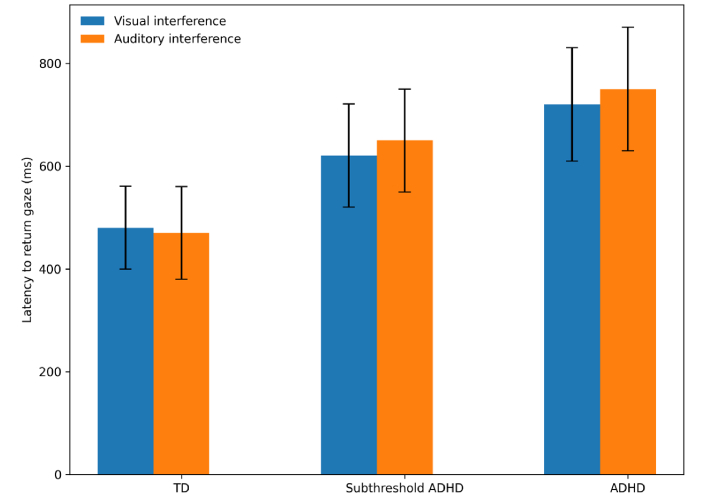

The main effect of condition was also significant, F(2, 198) = 182.55, p = 0.00016, η2p = 0.648, reflecting reduced performance under visual and auditory interference relative to no interference. The group × condition interaction was significant, F(4, 198) = 9.87, p = 0.00027, η2p = 0.167. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected comparisons indicated that under no interference, the three groups did not differ significantly (all p > 0.05; d ≤ 0.25). Under visual interference, ADHD children performed worse than TD children (p = 0.0004, d = 1.20) and subthreshold ADHD children (p = 0.021, d = 0.65), while subthreshold ADHD children performed worse than TD children (p = 0.010, d = 0.60). Under auditory interference, ADHD children were again most affected compared with TD children (p = 0.00011, d = 1.35) and subthreshold ADHD children (p = 0.01, d = 0.70), with subthreshold ADHD children showing intermediate performance relative to TD children (p = 0.02, d = 0.55). Eye-tracking data supported these behavioral effects. Mean fixation duration on the ball showed a significant group × condition interaction, F(4, 198) = 7.65, p = 0.00094, η2p = 0.134, with ADHD children displaying the shortest fixations under interference, subthreshold ADHD children intermediate, and TD children the longest. Latency to return gaze to the ball after distractor onset also differed across groups, F(2, 99) = 12.18, p = 0.00093, η2p = 0.197, with ADHD children showing the longest latencies, subthreshold ADHD children intermediate, and TD children the shortest, indicating graded differences in attentional control (Table 3). These results confirm Hypothesis 1, demonstrating that both overt performance and underlying attentional allocation are impaired in ADHD, with subthreshold ADHD children showing intermediate patterns. A supplementary MANOVA including all attentional and behavioral measures as dependent variables confirmed a significant multivariate main effect of group, Wilks’ λ = 0.64, F(8, 190) = 5.68, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.193, and condition, Wilks’ λ = 0.47, F(8, 190) = 19.85, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.455, as well as a significant group × condition interaction, Wilks’ λ = 0.71, F(16, 380) = 3.05, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.114. These multivariate effects corroborate the univariate ANOVA findings and support the robustness of the interference and group differences across behavioral and eye-tracking indices.

Eye-tracking metrics (mean ± SD) by group and condition.

| Condition | Group | Mean fixation duration on ball (ms) | Proportion of trial on ball (%) | Latency to return gaze to ball after distractor (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No interference | TD | 485.2 (60.1) | 86.3 (5.2) | - |

| Subthreshold ADHD | 420.5 (55.4) | 78.1 (6.3) | - | |

| ADHD | 400.3 (50.2) | 75.4 (6.0) | - | |

| Visual interference | TD | 440.6 (55.2) | 80.1 (6.0) | 480.3 (80.5) |

| Subthreshold ADHD | 380.4 (50.0)* | 72.2 (6.1)* | 620.7 (100.2)* | |

| ADHD | 350.2 (45.3)* | 68.0 (5.4)* | 720.5 (110.3)* | |

| Auditory interference | TD | 420.8 (50.3) | 78.4 (5.1) | 470.2 (90.4) |

| Subthreshold ADHD | 360.6 (50.2)* | 70.3 (6.2)* | 650.1 (100.1)* | |

| ADHD | 330.4 (45.1)* | 65.2 (5.0)* | 750.3 (120.2)* |

Mean fixation duration reflects the stability of visual focus on the target. Proportion of trial on the ball indicates sustained attentional engagement, expressed as the percentage of total trial time spent fixating on the target. Latency to return gaze to the ball after distractor onset represents the efficiency of attentional reorientation following distraction (measured only under interference conditions). Higher fixation duration and proportion values, along with lower reorientation latencies, indicate better attentional control. *: p < 0.05 vs. TD.

As illustrated in Figures 3, 4, and 5, eye-tracking measures revealed distinct patterns of visual attention across groups and conditions. Mean fixation duration on the ball reflected the stability of visual focus, proportion of trial time spent fixating on the ball indexed sustained attentional engagement, and latency to return gaze to the ball after distractor onset captured the efficiency of attentional reorientation. Overall, children with ADHD displayed shorter fixations, spent less time on the target, and were slower to reorient their gaze after distraction, with subthreshold ADHD children showing intermediate performance between ADHD and TD peers.

Group differences in mean fixation duration across interference conditions. Mean fixation duration on the target (in ms) across the no interference, visual interference, and auditory interference conditions for typically developing (TD) children, children with subthreshold ADHD, and children with ADHD. Between-group comparisons showed that, under both visual and auditory interference conditions, children with ADHD and children with subthreshold ADHD exhibited significantly shorter fixation durations than TD children (p < 0.05), with ADHD children showing the lowest values. No significant differences between groups were observed in the no interference condition (p > 0.05). Within-group comparisons indicated that, for all groups, fixation duration was significantly reduced in both visual and auditory interference conditions compared with the no interference condition (p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed between visual and auditory interference conditions within groups (p > 0.05). ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Group differences in gaze reorientation latency following distractor onset. Mean latency (in ms) to return gaze to the target after distractor onset under visual and auditory interference conditions only. ADHD children exhibited longer latencies compared to both TD and subthreshold ADHD participants, indicating slower attentional reorientation when interference was present. TD: typically developing; ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Group differences in time fixating on the target stimulus. Mean percentage of total trial time spent fixating on the target stimulus across the no interference, visual interference, and auditory interference conditions for typically developing (TD) children, children with subthreshold ADHD, and children with ADHD. Between-group comparisons revealed that, under both visual and auditory interference conditions, TD children spent a significantly greater proportion of time fixating on the target than both subthreshold ADHD and ADHD groups (p < 0.05), with the ADHD group showing the lowest fixation proportions. No statistically significant differences between groups were found in the no interference condition (p > 0.05). Within-group comparisons showed that, for all three groups, the proportion of time spent fixating on the target was significantly lower in both interference conditions compared with the no interference condition (p < 0.05). Differences between visual and auditory interference conditions within groups were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

To test Hypothesis 2 regarding interference awareness, children’s responses during the 15-s pause after each trial were analyzed separately for the visual and auditory interference conditions. For the visual interference condition, a chi-square test of independence revealed significant group differences in correct detection of the distractor, χ2(2, n = 102) = 20.34, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.45, indicating a large effect size. A similar pattern was observed for the auditory interference condition, χ2(2, n = 102) = 22.18, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.47.

In both modalities, TD children most frequently detected the distractor, subthreshold ADHD children showed intermediate detection rates, and ADHD children detected it least often, confirming Hypothesis 2. These findings suggest that reduced interference awareness in ADHD reflects a generalized deficit in attentional monitoring rather than modality-specific effects [38, 60, 61]. Table 4 reports the number of children correctly detecting the distractor in each condition.

Number of children correctly detecting the distractor during each interference condition.

| Condition | TD(n = 34) | Subthreshold ADHD(n = 34) | ADHD(n = 34) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual interference | 28 | 18 | 10 |

| Auditory interference | 26 | 16 | 8 |

TD: typically developing; ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

The present study investigated attentional control and interference awareness in children with ADHD, subthreshold ADHD, and TD peers using behavioral and eye-tracking measures under visual and auditory distractions. The results revealed a clear gradient of impairment across groups, with ADHD children exhibiting the most pronounced deficits, subthreshold ADHD children showing intermediate performance, and TD children performing best. These findings have important theoretical, empirical, and clinical implications, highlighting that attentional and metacognitive difficulties exist along a continuum rather than strictly within diagnostic boundaries.

Behavioral results demonstrated that ADHD children counted fewer ball bounces under interference conditions compared with both TD and subthreshold ADHD peers, whereas subthreshold ADHD children performed better than ADHD children but worse than TD children. Eye-tracking metrics revealed that ADHD children had shorter fixation durations on the target and longer latencies to return gaze following distractor onset, indicating reduced attentional stability and slower reorientation. Subthreshold ADHD children exhibited intermediate performance. These results provide robust evidence that attentional control deficits are present not only in clinical ADHD but also in subthreshold populations, supporting a dimensional rather than categorical view of cognitive control deficits [16, 29, 38].

Assessment of interference awareness further showed graded differences across groups. TD children most frequently detected distractors, ADHD children the least, and subthreshold ADHD children fell in between. This pattern suggests that deficits in metacognitive monitoring co-occur with attentional control impairments, consistent with prior studies showing reduced awareness of distractors in ADHD [31, 33]. Importantly, the partial awareness observed in subthreshold ADHD children indicates that even subclinical attentional difficulties can influence performance and everyday functioning, emphasizing the functional relevance of subthreshold symptomatology.

These findings align with and extend previous literature on ADHD and attentional control. Prior research has consistently reported heightened susceptibility to interference and slower attentional recovery in ADHD [25–28]. The intermediate performance of subthreshold ADHD children supports earlier suggestions that subclinical ADHD symptoms are associated with measurable cognitive difficulties, including deficits in executive control and attentional regulation [8, 9, 12]. Eye-tracking evidence in the present study provides direct, real-time confirmation of these impairments, demonstrating that both overt behavioral outcomes and underlying attentional allocation mechanisms are affected. The results are also consistent with theoretical frameworks integrating attentional encoding and executive control deficits. The CEAD model [34, 35] posits that early inefficiencies in attentional encoding disrupt the automatization of basic cognitive processes, overloading higher-order control and increasing distractibility. Our findings suggest these processes operate along a continuum, with subthreshold ADHD representing a moderate level of inefficiency that produces observable but less severe deficits compared with clinical ADHD. Cognitive control models emphasizing working memory, response inhibition, and set-shifting [36, 37] are also supported, as interference susceptibility and delayed gaze reorientation reflect limitations in maintaining task-relevant representations and suppressing irrelevant stimuli. Beyond confirming previous evidence, the present results refine both the CEAD and cognitive control models. Within the CEAD framework, our data suggest that deficits in automatization and attentional encoding are graded: subthreshold ADHD children exhibit partial automatization of attentional routines, leading to moderately increased cognitive load and interference susceptibility. This finding highlights a potential compensatory mechanism, whereby partial awareness of distraction supports adaptive regulation despite inefficient automatization. From the perspective of cognitive control theories, the current results indicate that executive inefficiencies (e.g., in inhibition and working memory) interact dynamically with perceptual encoding processes. This interplay demonstrates that attentional stability and metacognitive awareness are functionally linked rather than independent domains of deficit.

These findings have important implications for early identification and intervention. The demonstration that subthreshold ADHD is associated with measurable attentional and metacognitive deficits suggests that early support should not be limited to children meeting full diagnostic criteria. Interventions could include computerized attention training programs aimed at strengthening sustained and selective attention, mindfulness-based practices to enhance awareness of distraction and emotional regulation, and metacognitive therapy approaches focusing on self-monitoring, performance feedback, and strategic attentional shifting.

These methods may benefit children across the ADHD continuum by improving both automatic and controlled aspects of attention, potentially reducing the accumulation of functional difficulties over time.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The sample included only children aged 6–8 years, limiting generalizability to older age groups or adolescents. Interference awareness was measured using post-trial self-report, which may not fully capture real-time attentional monitoring. Future research should employ continuous measures, such as neurophysiological indices (e.g., electroencephalography, pupillometry) or concurrent eye-tracking metrics, to better assess attentional dynamics. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether subthreshold ADHD reflects a transient developmental stage, a stable intermediate phenotype, or a risk factor for progression to full ADHD. Replication across multiple cognitive tasks and in diverse cultural contexts would strengthen the generalizability of the findings. Another limitation concerns the cultural and contextual characteristics of the sample. All participants were recruited from primary schools in southern Italy, a context that may differ in educational practices, attentional demands, and classroom environments compared with other cultural settings. As cultural factors can influence attentional regulation and metacognitive development, cross-cultural replications are essential to determine whether the observed continuum of attentional control and interference awareness generalizes to children from different socio-educational systems.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that both ADHD and subthreshold ADHD are associated with deficits in attentional control and reduced interference awareness, with subthreshold ADHD children showing intermediate performance. These results support a continuum model of cognitive control impairments, highlighting the functional relevance of subclinical symptoms and the need for early detection and interventions targeting both attentional and metacognitive processes across the ADHD spectrum. While our findings underscore the presence of a graded continuum of attentional control and awareness, this perspective should be viewed as complementary to established diagnostic frameworks rather than as a substitute. Categorical classifications continue to serve critical functions in clinical assessment, diagnosis, and treatment planning.

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

ADHD-C: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-combined subtype

ADHD-H: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-predominantly hyperactive/impulsive

ADHD-I: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-predominantly inattentive

ANOVA: analysis of variance

CEAD: Cumulative and Emergent Automatic Deficit

DISC-IV: Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children

DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

MANOVA: multivariate analysis of variance

RPM: Raven’s Progressive Matrices

SCOD: Disruptive Behavior Disorder Rating Scale

SDAI: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale–IV: School Version

TD: typically developing

η2p: partial eta squared

RAF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. GP: Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. ST: Investigation. RV: Investigation. MHF: Investigation. PF: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Psychological Research of the University of Messina (protocol n. 314/25). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent to participation in the study was obtained from the parents/legal guardians of all participants prior to testing.

Not applicable.

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1150

Download: 22

Times Cited: 0

Montserrat Gerez-Malo ... Carlos Acosta