Affiliation:

1Doctoral Program in Biosciences, CUALTOS, University of Guadalajara, Tepatitlan de Morelos 47620, Mexico

Email: luis.ramirez3685@alumnos.udg.mx

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6063-8834

Affiliation:

2Center for Studies on Agriculture, Food, and the Climate Crisis, CUALTOS, University of Guadalajara, Tepatitlan de Morelos 47620, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9194-1719

Affiliation:

1Doctoral Program in Biosciences, CUALTOS, University of Guadalajara, Tepatitlan de Morelos 47620, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-3389-6663

Affiliation:

1Doctoral Program in Biosciences, CUALTOS, University of Guadalajara, Tepatitlan de Morelos 47620, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0482-7165

Affiliation:

3Department of Pharmacobiology, CUCEI, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44430, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8742-6247

Affiliation:

4Department of Physiology, CUCS, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara 44340, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8570-5848

Affiliation:

5Institute for Medical Science Research, CUALTOS, University of Guadalajara, Tepatitlan de Morelos 47620, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0853-9396

Affiliation:

6Doctoral Program in Science and Technology, CULAGOS, University of Guadalajara, Lagos de Moreno 47463, México

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-8790-3319

Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2025;5:1004132 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2025.1004132

Received: September 17, 2025 Accepted: December 16, 2025 Published: December 25, 2025

Academic Editor: Marcello Iriti, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

The article belongs to the special issue Natural Products in Neurotherapeutic Applications

Aim: Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) represent critical neurological disorders that have emerged as significant health concerns in the 21st century. The pharmacological interventions currently employed to manage these diseases demonstrate limited efficacy and some adverse side effects. Historically, natural products have been used to develop therapeutic agents targeting neurodegenerative disorders. This study aimed to apply in silico techniques to investigate the pharmacological mechanisms of capsaicin as a possible alternative treatment or coadjutant phytotherapy for PD and AD.

Methods: We obtained target genes for capsaicin, PD, and AD from the HERB database, the Swiss Target Prediction database, the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database, and the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform, and matched them. Subsequently, we constructed a protein-protein interaction network and performed enrichment analysis of the common targets. Then, the interactions of capsaicin with the proteins with the highest degree were tested using molecular docking. The stability of the complexes was verified using molecular dynamics techniques.

Results: A total of 25 targets were found in common from the databases for capsaicin, AD, and PD. The enrichment analysis revealed that proteins from these targets influenced integrin activity in the IGF1-IGF1R complex, cholinesterase activity, and dopamine neurotransmitter receptor activity, all of which are coupled via protein Gi/Go, among other cellular processes. From the protein-protein interaction network, we identified the hub proteins IL6, GSK3B, CASP, BCL2, ESR1, SIRT1, NGF, IGF1, and HMOX1. Furthermore, molecular docking studies between hub proteins and capsaicin showed strong binding affinity. Finally, molecular dynamics simulations support a stable interaction between capsaicin and SIRT1, ESR1, HMOX1, and NGF.

Conclusions: This work contributes to understanding the neuroprotective activity of capsaicin in PD and AD. However, these bioinformatic predictions require further experimental validation.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are the most rapidly increasing neurological disorders globally, posing significant management challenges owing to the progression of motor and cognitive disabilities in affected individuals [1]. Both neurodegenerative disorders are characterized by intricate molecular mechanisms that impede the development of effective treatments. Aβ plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, gliosis, and neuronal loss are the primary pathological features of AD. Eventually, individuals with AD experience severe memory loss, hallucinations, disorientation, and loss of autonomy [2]. In contrast, α-synuclein aggregation, ferroptosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction are hallmarks of PD. Bradykinesia, rest tremors, rigidity, and loss of postural reflexes are the motor symptoms caused by this molecular process. Furthermore, non-motor symptoms, such as hypotension, constipation, urinary disturbances, sleep disorders, and a spectrum of neuropsychiatric symptoms, further complicate the treatment of PD [3, 4]. Although synthetic agents have shown promise as multifunctional drugs for AD and PD, key limitations, such as pharmacokinetics and safety concerns, persist. Unfortunately, the medications currently available for AD and PD only alleviate symptoms and do not halt neurodegeneration, underscoring the significance of novel drug discovery. Natural products may offer efficient and safe pharmacodynamic properties for the treatment of these challenging neurodegenerative disorders. Consequently, plants and their bioactive compounds have been extensively investigated for their therapeutic potential in various neurodegenerative diseases, including AD and PD [5, 6].

In the last few years, capsaicin (CAP), a prominent constituent of chili peppers and member of the vanilloid family, has gained significant attention within the scientific community due to its wide array of pharmacological effects and diverse biological properties, including pain management, cardiovascular health, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic regulation [7]. Daily CAP consumption worldwide is estimated to be 1.5 mg per person in the United States and Europe, 25 mg per person in India, and 200 mg per person in Mexico [8]. In addition, CAP has been shown in animal studies to have oral bioavailability of 50–90% and to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [8]. This phytochemical compound activates the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptor, which is implicated in nociception, offers neuroprotection against aggregation of misfolded proteins, and improves mitochondrial function [9]. However, CAP toxicity within the central nervous system may result in seizures, increased activity, confusion, and compromised motor function [10]. Thus, the efficacy of plant-derived chemical compounds is often complicated by their interactions with target molecules, both synergistic and antagonistic [11]. Computational biology and bioinformatics tools, such as pharmacological networks, molecular dynamics simulations, and molecular docking, have emerged as effective methodologies for elucidating these interactions and assessing drug likeness and pharmacokinetic properties [12–14]. Recent advancements in computational biology have further enabled the refinement of in silico study processes through the application of machine learning and deep learning, thereby enhancing the quality of biomedical data interpretation [15, 16]. Although the potential neuroprotective effects of CAP have been previously investigated in vitro and in vivo, this study introduces an innovative approach by employing network pharmacology to identify shared mechanisms between AD and PD. Furthermore, it validates the stability of CAP interactions with its primary targets [sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1), heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1), and nerve growth factor (NGF)] through 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations and Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) calculations. Therefore, this network pharmacology study aimed to explore the molecular mechanism of CAP and its targets using bioinformatic tools, to suggest CAP as a possible alternative treatment for AD and PD.

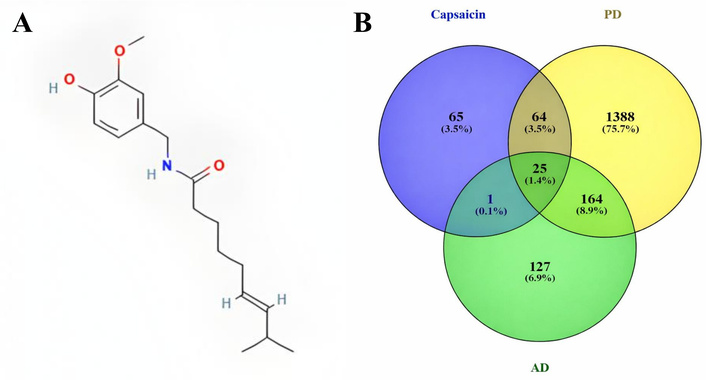

The chemical structure and SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry Specification) notation of CAP were sourced from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/1548943; accessed on 26 September 2024) [17]. Subsequently, molecular targets associated with CAP were acquired from the Swiss Target Prediction database (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/; accessed on 26 September 2024) [18], Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD; http://ctdbase.org/; accessed on 26 September 2024) [19], Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology and Analysis Platform (TCMSP) (https://tcmsp-e.com/molecule.php?qn=2579; accessed on 26 September 2024) [20]. Genes related to AD and PD were then retrieved from the HERB database (http://herb.ac.cn/; accessed on 26 September 2024) [21]. It is important to note that TRPV1 was not identified as a gene associated with AD in the HERB database; therefore, it was excluded from subsequent analyses. Finally, the intersection between CAP targets and AD and PD genes was determined and visualized using Venny 2.1.0. (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/; accessed on 26 September 2024) [22], where the TRPV1 was not identified in the common genes between AD, PD, and CAP.

SMILES: CC(C)/C=C/CCCCC(=O)NCC1=CC(=C(C=C1)O)OC

The 25 common genes for AD, PD, and CAP were identified as therapeutic targets and analyzed using the ShinyGO 0.85 database (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/; accessed on 31 October 2025). This analysis aimed to perform gene ontology (GO) enrichment for biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MFs), and cellular components, as well as Reactome pathway enrichment [23–26]. The cut-off criterion with a False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05 was applied, and results were limited to Homo sapiens (TaxID 9606).

Afterwards, the list of proteins was examined using Cytoscape v3.10.3 software (accessed on 31 October 2025). The STRING network file was downloaded to create a protein-protein interaction network and determine the degree of connectivity between proteins and known hub genes [27]. For this analysis, a confidence limit (score) of 0.7 was considered and restricted to Homo sapiens (TaxID 9606).

The topological characteristics of the protein-protein interaction network were examined using the Network Analyzer plugin [28] in Cytoscape. In this context, parameters such as highest degree (HD), closeness betweenness (CB), and closeness centrality (CC) were used to select the hub genes. However, only genes that met all three criteria (HD, CC, and CB) were recognized as hub genes for further evaluation.

Before conducting molecular docking between CAP and the target proteins, the .pdb files of the proteins were downloaded from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/; accessed on 30 October 2024) [29]. In addition, only entries that were reviewed and structured and had pLDDT scores between 70 and 100 (high confidence) were selected. The .sdf file of the CAP was obtained from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; accessed on 30 October 2024) [17]. Finally, molecular docking was performed using CBDOCK, and the results were visualized using BIOVIA Discovery Studio [30].

To assess the stability of the ligand-receptor complex, molecular dynamics simulations were performed on the four proteins with the lowest binding energies from the molecular docking test. The molecular dynamics simulation was performed with Gromacs v. 2024.1, while the Charmm-GUI base (https://www.charmm-gui.org/; accessed on 7 September 2025) was used to generate the input files [31]. Proteins were preprocessed using the PDB reading tool [32]. The docking ligand was converted to .mol2 format using OpenBabel (https://openbabel.org/index.html; accessed on 7 September 2025) [33]. The Ligand Reader & Modeler tool (from Charm-GUI base) was used to generate the topology and parameter files from the ligands’ .mol2 [34]. The ligand-receptor complexes (CAP-protein) were combined into a single .pdb file to create the system inputs for Gromacs, utilizing the ‘Solution Builder’ tool [35]. The protein was placed in a cubic water box with an edge distance of 10 Å to match its dimensions. Using the Monte Carlo method, the systems were neutralized with K+ and Cl– ions at a concentration of 0.15 M. Finally, before running the process, some requirements were considered:

To eliminate steric overlap, the steepest descent method was applied to subject the systems to 5,000 energy-minimization steps [36].

Using the V-rescale temperature coupling method, maintaining a constant coupling of 1 ps at 303.15 K, all systems underwent an NVT (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) equilibrium phase for 125,000 steps [36].

The molecular dynamics simulations were conducted for 100 ns using the CHARMM36m force field [37].

Additionally, GROMACS tools were used to evaluate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the complexes, root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg), and hydrogen bonds. The GnuPlot program (v. 5.4) was used to plot data [38].

The MM/PBSA method was employed to determine the binding free energy of CAP-protein complexes supported by the gmx_MMPBSA (v.1.6.4; extension tool to visualize in GROMACS, obtained from https://valdes-tresanco-ms.github.io/gmx_MMPBSA/dev/; accessed on 7 September 2025) [31]. This outcome allows for the comparison of the relative free energies of the same ligand when binding to different proteins, offering valuable insights into how CAP influences protein conformation and binding strength. This technique was utilized to estimate the binding free energy from molecular dynamics simulation trajectories in explicit solvent, by separately considering three components: the complex, the receptor, and the ligand. The binding free energy (ΔGbinding) of the lead compounds in complex with the protein was calculated using the following Equation 1:

In the equation above, Gcomplex signifies the energy of the protein-ligand complex, whereas Gprotein and Gligand denote the energies of the protein and ligand in an aqueous environment, respectively. To ensure a valid MM/PBSA analysis, the binding free energy (ΔGbinding) was calculated using the last 40 ns (after reaching convergence from 60 ns to 100 ns) of the production trajectory. A total of 100 snapshots were extracted from this time window (one every 400 ps) for the final MM/PBSA calculations.

The binding free energy (ΔGbind) for each component can be determined using Equation 2, which takes into account the contributions from both the gas-phase term (ΔGgas) and the solvation term (ΔGsolv). The ΔGgas contribution is comprised of van der Waals energy (ΔEvdw) and electrostatic energy (ΔEele), as illustrated in Equation 3. Additionally, the ΔGsolv contribution is made up of two parts: the electrostatic solvation energy, calculated via the Poisson-Boltzmann model (ΔGpol), and the non-polar solvation energy, estimated from the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) (ΔGnonpol), as detailed in Equation 4.

Figure 1A presents the CAP structure as obtained from PubChem. Using the Swiss Target Prediction database, CTD, and TCMSP, a total of 155 targets were obtained. Furthermore, the HERB database facilitates the identification of 317 and 1,641 genes associated with AD and PD, respectively.

Chemical structure of capsaicin in 2D with PubChem CID: 1548943 (A); and a Venn diagram illustrating the matched targets between capsaicin and targets associated with PD and AD (B). AD: Alzheimer’s disease; PD: Parkinson’s disease.

The Venn diagram (Figure 1B) shows that 25 genes are shared between the AD and PD genes and the CAP-related targets. These shared genes were selected as potential targets for CAP’s therapeutic effects in AD and PD.

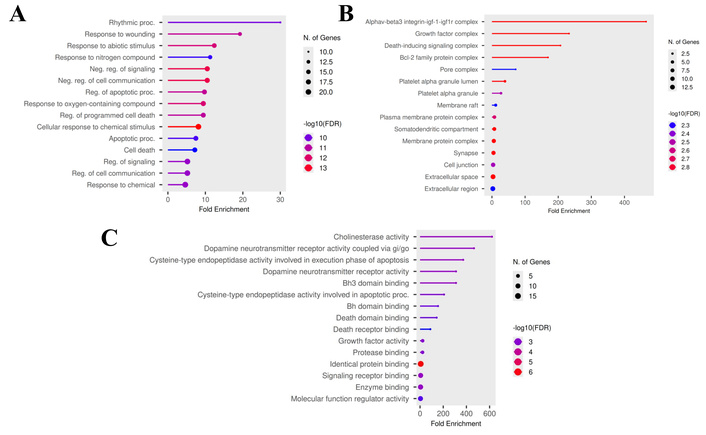

GO and pathway enrichment analyses for the 25 significant genes [VEGFA, BCL2 (apoptosis regulator Bcl-2), HMOX1, ABCB1, BAX, CASP3 (caspase 3), CASP7, FAS, GSK3B (glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta), IGF1 (insulin-like growth factor 1), IGF1R (IGF1 receptor), IL6 (interleukin-6), KNG1, NGF, NOS3 (nitric oxide synthase 3), SIRT1, CNR2, BCHE, ACHE, DRD2, DYRK1A, VCP, DRD3, ESR1, SLC6A4] were conducted using ShinyGO 0.85. The study showed that CAP is primarily involved in BP related to the rhythmic process and the response to wounding (Figure 2A). Conversely, the cellular components ontology primarily encompasses genes encoding proteins found in the IGF1R and growth factor complexes (Figure 2B). Regarding the MF ontology, the genes were associated with cholinesterase and dopamine neurotransmitter receptor activities (Figure 2C).

Gene ontology enrichment analysis for target genes (top 15). (A) Biological process; (B) cellular component; (C) molecular functions.

The results of the Reactome pathway enrichment analysis (Figure 3) indicated that the principal targets have a significant effect on dopamine receptors and on caspase activation via the apoptosome.

The STRING database for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins was utilized to construct the protein-protein interaction network, which was subsequently introduced and visualized in Cytoscape (Figure 4). In this network, nodes represent target proteins, and edges indicate interactions between them. Furthermore, through topological network analysis, the hub genes BCL2, SIRT1, CASP3, IL6, HMOX1, ESR1, IGF1, NGF, and GSK3B were determined. However, IGF1R and NOS3 were not present in all three groups (Table 1); therefore, they were excluded from subsequent evaluations.

Target-target interaction network between AD and PD hub targets with a confidence limit of 0.7. BCL2: apoptosis regulator Bcl-2; SIRT1: sirtuin 1; CASP3: caspase 3; IL6: interleukin-6; HMOX1: heme oxygenase 1; ESR1: estrogen receptor 1; IGF1: insulin like growth factor 1; NGF: nerve growth factor; GSK3B: glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; PD: Parkinson’s disease.

The top 10 highest degree, CB, and CC genes of the target-target interaction network between AD and PD targets.

| No. | Gen name | Degree | Gen name | CB | Gen name | CC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BCL2 | 11 | BCL2 | 0.239455782 | BCL2 | 0.75 |

| 2 | SIRT1 | 9 | CASP3 | 0.182369614 | SIRT1 | 0.714285714 |

| 3 | CASP3 | 9 | GSK3B | 0.133333333 | CASP3 | 0.714285714 |

| 4 | IL6 | 8 | SIRT1 | 0.112981859 | IL6 | 0.652173913 |

| 5 | HMOX1 | 6 | NGF | 0.079365079 | IGF1 | 0.6 |

| 6 | ESR1 | 6 | NOS3 | 0.056349206 | HMOX1 | 0.6 |

| 7 | IGF1 | 6 | IL6 | 0.045918367 | ESR1 | 0.6 |

| 8 | NOS3 | 5 | ESR1 | 0.024546485 | NGF | 0.576923076 |

| 9 | NGF | 5 | HMOX1 | 0.022505668 | IGF1R | 0.555555555 |

| 10 | GSK3B | 4 | IGF1 | 0.015476190 | GSK3B | 0.555555555 |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; PD: Parkinson’s disease; CB: closeness betweenness; CC: closeness centrality; BCL2: apoptosis regulator Bcl-2; SIRT1: sirtuin 1; CASP3: caspase 3; IL6: interleukin-6; HMOX1: heme oxygenase 1; ESR1: estrogen receptor 1; IGF1: insulin-like growth factor 1; NOS3: nitric oxide synthase 3; NGF: nerve growth factor; GSK3B: glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; IGF1R: IGF1 receptor.

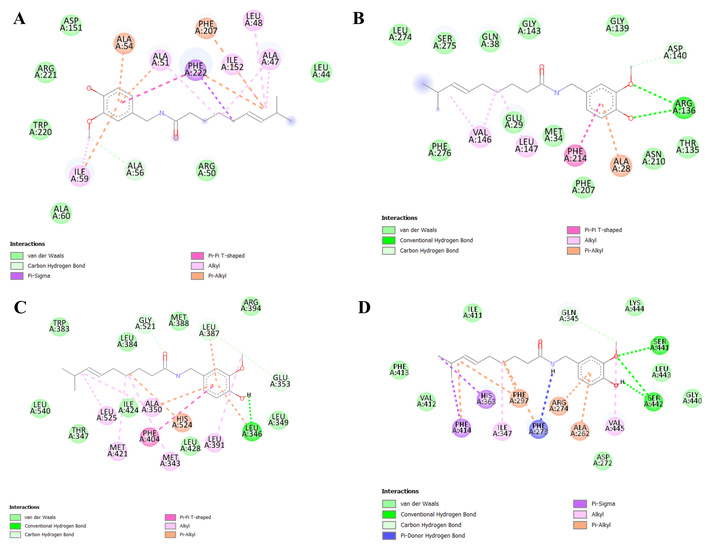

Utilizing cavity detection-guided blind docking CB-DOCK2, a molecular docking simulation between CAP and the 9 hub proteins screened from the protein-protein interaction network was conducted (Table 2). Affinity functioned as the scoring criterion in molecular docking, where a reduced score signified a greater binding affinity to the target protein. The estimated binding energy varied from –4.0 to –8.7 kcal/mol for the CAP and their corresponding target proteins.

The detailed molecular docking information of CAP with hub proteins.

| Gene symbol | Protein | Functiona | ∆Gb (kcal/mol) | Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL6 | Interleukin-6 | The protein is a potent inducer of the acute phase response. | –5.8 | GLU87-LEU90-ASN91-LEU92 PRO93-LYS94-MET95-PHE102-PHE122-LEU193-ILE194-ARG196-SER197-PHE198-LYS199-GLU200-PHE201-LEU202-GLN203-SER204-ARG207 |

| GSK3B | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta | Active protein kinase that acts as a negative regulator in the hormonal control of glucose homeostasis. | –4.0 | ARG6-THR7-THR8-SER9 PHE10-ALA11-GLU12-VAL17-GLN18-GLN19-PRO20-SER21-ALA22-PHE23-ASP49-SER66-PHE67-GLY68-LYS85-VAL87-LEU88-GLN89-ASP90-LYS91-ARG92-PHE93-LYS94-ASN95-ARG96-GLU97-LEU98-GLN99-ARG102-PHE115-TYR117-VAL126-PHE201-GLY202-ALA204 |

| CASP3 | Caspase 3 | The protein plays a central role in the execution phase of cell apoptosis. | –6.5 | MET61-THR62-SER63 HIS121-GLY122-GLU123-PHE128-CYS163-LEU168-TYR204-SER205-TRP206-ARG207-ASN208-SER209-TRP214-SER249-PHE250-SER251-PHE252-ASP253-PHE256 |

| BCL2 | Apoptosis regulator Bcl-2 | An integral outer mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks the apoptotic death of some cells. | –5.1 | SER97 ARG98 SER99-ALA100-PRO101-PRO102-ASN103-LEU104-TRP105-ALA106-ALA107-GLN108-ARG109-TYR110-GLY111-ARG112-GLU113-ARG115-ARG116 |

| ESR1 | Estrogen receptor 1 | An estrogen receptor and ligand-activated transcription factor. | –8.4 | MET343-LEU345-LEU346-THR347-LEU349-ALA350-GLU353-TRP383-LEU384-LEU387-MET388-GLY390-LEU391-ARG394-LEU402-LEU403-PHE404-MET421-ILE424-PHE425-LEU428-GLY521-MET522-HIS524-LEU525-LEU540 |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 | Studies suggest that the human sirtuins may function as intracellular regulatory proteins with mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. | –8.7 | GLY261-ALA262-GLY263-ASP272-PHE273-ARG274-SER275-TYR280-GLN294-PHE297-GLN345-ASN346-ILE347-HIS363-GLY364-ILE411-VAL412-PHE413-PHE414-GLY415-GLU416-LEU418-GLY440-SER441-SER442-LEU443-LYS444-VAL445-ARG446-PRO447-ASN465-ARG466-GLU467 |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor | Protein involved in the regulation of growth and the differentiation of sympathetic and specific sensory neurons. | –6.8 | LEU44-ALA47-LEU48-ARG50-ALA51-ALA54-PRO55-ALA56-ALA57-ALA58-ILE59-ALA60-ARG81-LEU82-ARG83-SER84-ASP151-ILE152-LYS153-THR206-PHE207-VAL208-LYS209-ASP214-GLN217-ALA219-TRP220-ARG221-PHE222 |

| IGF1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 | Protein is involved in mediating growth and development. | –6.4 | LEU35-LEU37-CYS38-LEU39-THR41-PHE42 SER45-LEU53-GLU57-LEU58-ASP60-ALA61-PHE64-VAL65-CYS95-CYS96-ARG98-SER99-CYS100-ASP101-LEU102-LEU105 |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase 1 | An enzyme in heme catabolism. | –7.1 | LEU17-LYS18-GLU19-THR21-LYS22-HIS25-THR26-ALA28-GLU29-MET34-GLN38-VAL50-LEU54-TYR58-TYR114-TYR134-THR135-ARG136-TYR137-LEU138-GLY139-ASP140-SER142-GLY143-GLY144-VAL146-LEU147-ILE150-PHE166-PHE167-ARG183-PHE207-ASN210-PHE214-LEU272-LEU274-SER275-PHE276 |

a: Information is taken from the National Library of Medicine (NIH) page; b: the outcomes represent the values with a high binding activity.

Finally, the four combinations with the lowest docking values were chosen to elucidate the various bond types between the proteins and the active compound (Figure 5).

Favorable interactions of capsaicin with target proteins. (A) NGF-CAP; (B) HMOX1-CAP; (C) ESR1-CAP; (D) SIRT1-CAP. NGF: nerve growth factor; CAP: capsaicin; HMOX1: heme oxygenase 1; ESR1: estrogen receptor 1; SIRT1: sirtuin 1.

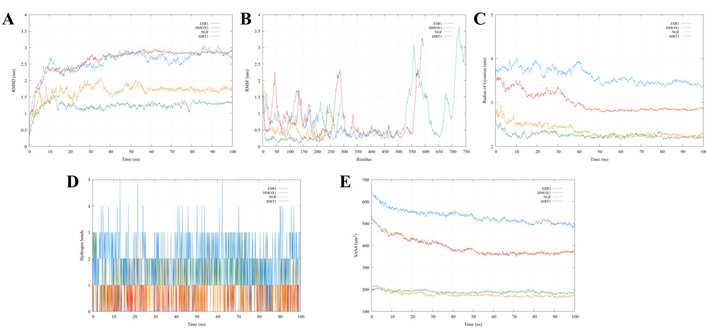

Based on the molecular docking results, molecular dynamics simulations were performed to elucidate the dynamic behavior and stability of the four target proteins with the lowest binding energies. In this context, the proteins SIRT1, ESR1, HMOX1, and NGF were selected for the 100 ns analyses. The RMSD results indicated that all systems progressively stabilized after structural reorganization over time, suggesting that the interaction with CAP did not cause significant disturbances in the overall protein conformation (Figure 6A). Based on the convergence check, defined as the point at which the RMSD plots stabilized and fluctuated around an average value, all systems reached a stable equilibrium after approximately 60 ns. The RMSF analysis facilitated the identification of local flexibility within the residues along the polypeptide chain and the impact of CAP binding on this flexibility. In all analyzed complexes (NGF-CAP, HMOX1-CAP, ESR1-CAP, SIRT1-CAP), residues directly interacting with the ligand exhibited RMSF values below 0.5 nm (Figure 6B), signifying low fluctuation and, consequently, favorable conformational stability within the binding site region. Thus, the stability of the active site residues serves as an additional indicator of the potential efficacy of ligands as modulators of their respective target proteins. The Rg serves as an indicator of the three-dimensional compactness of a protein structure. A reduction in Rg typically correlates with a more compact and potentially more stable structure, whereas elevated values suggest expansion or increased conformational flexibility. In this study, the proteins experienced an initial phase of structural reorganization during the first 50 ns (Figure 6C), characterized by oscillations, indicative of an adjustment process induced by the binding of the CAP compound. Subsequently, the Rg tended to decrease progressively, indicating a transition to a more compact conformation. Figure 6D presents the results of the hydrogen bonds for interactions between the ligand and protein. These interactions vary during molecular dynamics, with SIRT1 achieving up to five interactions, conferring high stability to the molecule. Subsequently, HMOX1 (3 interactions), NGF (3 interactions), and ESR1 (1 interaction) were observed. Evaluation of the SASA revealed a trend across all complexes (Figure 6E), supporting the hypothesis of progressive compaction. Notably, complexes with SIRT1 and ESR1 exhibited a more pronounced reduction in SASA, which was associated with a significant conformational change and a potential gain in structural stability. In contrast, the HMOX1 and NGF complexes showed smaller fluctuations in both Rg and SASA, suggesting a more stable structure from the early stages of the simulation, possibly with less ligand influence on their conformational dynamics.

Molecular dynamics analysis for ESR1, HMOX1, NGF, and SIRT1. (A) Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD); (B) root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF); (C) radius of gyration; (D) hydrogen bonds; (E) solvent-accessible surface area (SASA). ESR1: estrogen receptor 1; HMOX1: heme oxygenase 1; NGF: nerve growth factor; SIRT1: sirtuin 1.

Ultimately, the binding affinity of the protein-CAP complexes was calculated using the MM/PBSA method, and the results are presented in Table 3, including the standard deviation for each system. The values of ΔEvdw were higher than the electrostatic contribution. On the other hand, the highest ΔGbind value was obtained by ESR1-CAP (–38.94 kcal/mol), followed by HMOX1-CAP (–26.83 kcal/mol), SIRT1-CAP (–26.54 kcal/mol), and NGF-CAP (–26.45 kcal/mol). All values were calculated using 100 snapshots extracted from the 60–100 ns production time window.

Binding free energies and energy components of protein-CAP complexes calculated using the MM/PBSA approach.

| Complex | Average binding energy (kcal/mol) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔEvdw | ΔEele | ΔGpol | ΔGnonpol | aΔGbind | |

| ESR1 | –48.69 | –6.57 | 20.32 | –4.00 | –38.94 ± 3.38 |

| HMOX1 | –33.73 | –14.06 | 25.47 | –4.50 | –26.83 ± 4.99 |

| NGF | –36.58 | –8.60 | 22.82 | –4.10 | –26.45 ± 3.93 |

| SIRT1 | –38.77 | –7.80 | 24.68 | –4.65 | –26.54 ± 7.76 |

aΔGbind represents the total binding free energy calculated as the sum of all individual energy components (ΔGbind = ΔEvdw + ΔEele + ΔGpol + ΔGnonpol), and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. CAP: capsaicin; MM/PBSA: Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area; ESR1: estrogen receptor 1; HMOX1: heme oxygenase 1; NGF: nerve growth factor; SIRT1: sirtuin 1.

CAP is the primary pungent compound in chili peppers and has been used extensively in traditional medicinal practices for centuries. On the other hand, AD and PD are neuropathological conditions primarily characterized by the accumulation of misfolded proteins: alpha-synuclein in PD and tau protein, along with beta-amyloid peptides, in AD. The presence of these misfolded proteins initiates other pathophysiological processes common to both disorders, including mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and neuroinflammation. These processes contribute to neuronal loss and synaptic disconnection in the hippocampus in AD, and the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra in PD [2, 3]. Thus, investigating the mechanisms of CAP in AD and PD requires a thorough understanding of its molecular interactions and biological mechanisms. This understanding can be facilitated through advanced in silico methodologies.

In this context, although the neuroprotective potential of CAP has been previously investigated [39, 40], this study introduces an innovative approach by incorporating molecular mechanisms and network pharmacology analysis. This approach identifies 25 common targets and 9 hub proteins, with rigorous validation via molecular dynamics simulations for 100 ns and binding free energy (MM/PBSA) calculations. This dynamic validation is essential, as it confirms the structural feasibility and stability of CAP interactions with key therapeutic protein targets such as SIRT1 and ESR1, thereby providing robust structural evidence that was previously unavailable in the literature.

Pharmacological networks represent a multidisciplinary research domain encompassing genomics, proteomics, and biological systems. These methodologies facilitate the integration of data regarding interactions among biological molecules, signaling pathways, and disease networks, thereby elucidating the mechanisms by which natural compounds exert their effects [41, 42]. In this study, we delineated and analyzed the interactions between CAP and its 25 targets within the contexts of the PD and AD pathways. Our GO analysis revealed that these targets are predominantly associated with BP, including rhythmic processes. Previous research has shown that CAP can affect and regulate circadian rhythms and brain activity [43, 44], primarily through the TRPV1 channel; however, TRPV1 was not identified among the 25 genes included in the GO analyses (see Table S1, Table S2, Table S3, and Table S4). Rohm et al. [45] found that CAP regulates the expression of genes such as DRD2, independently of the TRPV1 signaling pathway. In a recent bioinformatic study, DRD2 has been identified as a pivotal gene linking PD to the circadian rhythm [46]. GSK3B is another target implicated in these processes, particularly in neural activities. Moreover, Xu et al. [47] observed that CAP appears to prevent tau protein hyperphosphorylation by enhancing PI3K/AKT activity and inhibiting GSK3B in the hippocampus of a type 2 diabetes rat model, contingent upon the TRPV1 signaling cascade. Thus, it is essential to note that CAP’s impact might be dependent or independent of the TRPV1 signaling pathway. The αvβ3 integrin-IGF1-IGF1R complex and growth factor complex were identified as the principal cellular components affected by CAP in our analysis. There is a paucity of information regarding CAP’s influence on integrins within the IGF1-IGF1R complex; thus far, it is only postulated that CAP can elevate IGF-I levels [48]. Regarding the development factor complex, CAP may promote VEGFA expression and be involved in angiogenesis [49]. In the context of neurodegenerative diseases like AD and PD, this target holds significant importance. VEGFA is directly linked to neuronal excitability, neurotransmission, and synaptic plasticity. Nonetheless, elevated levels of VEGFA can compromise the integrity of the BBB and increase microvascular permeability [50]. These findings underscore the importance of accounting for variables such as dosage, physiological state, and formulation when administering CAP.

Cholinesterase activity and dopamine neurotransmitter receptor activity, coupled with the protein Gi/Go, are MFs implicated in the CAP mechanism. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) are members of the cholinesterase enzyme family, with BChE’s role being less well-defined compared to AChE. While AChE is primarily recognized for degrading acetylcholine in neural synapses, it has also been reported to participate in bone growth and remodeling [51, 52]. Mansalai et al. [53] found that CAP and hydrocapsaicin exert a mixed inhibitory effect on AChE, as indicated by both in vitro and in silico experiments. This has led to the consideration of CAP and its derivatives (capsaicinoids) as possible therapeutic agents for AD [53–55]. Conversely, CAP does not directly interact with dopamine receptors, such as DRD2 and DRD3; however, it can influence dopamine release via TRPV1 [45].

In this research, Reactome pathway enrichment analysis identified that AD and PD genes are associated with dopamine receptors and activation of caspases through the apoptosome. This result matches the previously obtained outcome for MFs. In cancer cells, it is well known that CAP can activate caspases, such as CASP3 and CASP7, which trigger programmed cell death [56, 57]. In this neurological framework, CASP3 has been implicated in the conversion of amyloid precursor protein into amyloidogenic fragments and the early-stage accumulation of caspase-cleaved amyloid precursor protein in AD [58]. In addition, both caspases are integral to the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons, a hallmark of PD [59]. Some studies demonstrated the capacity of CAP to decrease CASP3 expression [60, 61], although there are no studies regarding CASP7. On the other hand, although CAP can inhibit cell death in neurons, some studies suggest that it can also activate the caspase cascade to promote apoptotic processes [62].

Analysis of the protein-protein interaction network identified nine potential proteins (IL6, GSK3B, CASP3, BCL2, ESR1, SIRT1, NGF, IGF1, and HMOX1) for molecular docking with CAP. Molecular docking, also referred to as computationally simulated ligand binding, is a robust technique for predicting interactions between a ligand (small molecule) and a protein at the atomic level. This method holds significant potential in nutraceutical research and has evolved into a powerful tool for drug development. Prior in vitro studies have employed molecular docking analyses in nutraceutical research to provide critical insights [63, 64]. All interactions of CAP with the nine proteins exhibited low Gibbs free energy (∆G) values; however, SIRT1, ESR1, HMOX1, and NGF showed the highest affinity binding. SIRT1 is a member of the sirtuin family of proteins, which are found in subcellular compartments. These proteins are involved in various processes within the nervous system, including axon development, neuronal differentiation, and neurite outgrowth [65]. Moreover, in AD and PD, SIRT1 overexpression may exert a neuroprotective effect by regulating neuroinflammation and autophagy [66, 67]. In a murine model, CAP administration at 2 μg/h for 28 days can induce SIRT1 expression, thereby reducing ROS and decreasing inflammatory cytokines in the paraventricular nucleus [68]. Conversely, CAP can enhance SIRT1 expression by activating TRPV1, thereby facilitating Ca2+ influx into human umbilical vein endothelial cells [69]. It has been reported that a moderate and well-regulated increase in calcium influx can serve as a neuroprotective mechanism. Still, it could result in a neurotoxic condition, in AD and PD, when the influx is prolonged and excessive [70]. Additionally, the induction of SIRT1 expression via CAP might promote axon development in embryonic hippocampal neurons [71]. The ESR1 gene encodes estrogen receptor 1, which binds estrogen and helps regulate mood and cognitive function [72]. This protein has been implicated in the neuroprotective process against PD and AD by mediating estrogen to support the lifespan of dopamine neurons and reduce neuroinflammation [73, 74]. Recently, an in vitro study by Pietrowicz and Root-Bernstein [75] showed that CAP directly interacts with ESR1, increasing its binding to estradiol via a TRPV1-independent mechanism at CAP concentrations of 0.001–0.1 mg/mL. Heme oxygenase 1 is an enzyme associated with the expression of the HMOX1 gene, which catalyzes the conversion of heme to carbon monoxide, biliverdin, and free iron [76]. Evidence suggests that the administration of CAP in a murine model reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress factors in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus via activation of the Nrf2/HMOX1 pathway [77]. Furthermore, a CAP diet (0.0015%) in a diabetic type 2 murine model has been shown to inhibit ferroptosis by activating TRPV1 and the Nrf2/HMOX1 signaling pathway. Nonetheless, there is a notable lack of experimental studies directly evaluating HMOX1 expression in neurodegenerative models treated with CAP [78]. NGF is a gene that encodes a neuropeptide, the nerve growth factor, which is produced during injury or inflammation and increases thermal sensitivity [79]. It has been implicated in the growth and survival of mammalian peripheral sensory and sympathetic nerve cells [80]. A study conducted on neonatal murine neurons demonstrated that NGF interacts with CAP, thereby enhancing the Ca2+ influx mediated by TRPV1 [81]. Furthermore, this neuropeptide has been proposed (in a narrative review) as a therapeutic target in AD to enhance cholinergic neuronal survival and plasticity in the brain [82].

Finally, we validated the molecular docking results for SIRT1, ESR1, HMOX1, and NGF using molecular dynamics simulations. Notably, SIRT1 and ESR1 underwent structural adjustments, resulting in increased compaction and stability, as evidenced by reduced Rg and SASA. This was further corroborated by the RMSD evolving towards constant values. Conversely, the HMOX1 and NGF complexes exhibited sustained structural stability throughout the simulation with minimal fluctuations, indicating a more passive interaction with CAP. As part of the molecular dynamics analysis, MM/PBSA data indicate that the ESR1-CAP complex exhibits the highest binding affinity, suggesting a remarkably stable interaction between ESR1 and CAP. As previously indicated, CAP can directly interact with ESR1 and facilitate estradiol binding to these receptors. In a murine model, 17β-estradiol has been identified as a highly potent agent against neuroinflammation, synaptic loss, and neurodegeneration [83]. One study found that elevated estrogen levels throughout life confer protection against PD [84]. Additionally, research conducted by Adams and Kumar [85] in 2013 documented the beneficial effects of 17β-estradiol in a male patient with PD who experienced motor fluctuations and dyskinesia. In this context, CAP could be considered as a possible adjunct to hormonal therapies for the treatment of AD and PD. However, further studies are warranted.

The energy differences among the NGF-CAP, HMOX1-CAP, and SIRT1-CAP complexes were minimal, approximately 0.30 kcal/mol. This suggests that, aside from ESR1, these systems exhibit comparable binding affinities and are equally favorable. In addition, the intermolecular van der Waals and electrostatic interactions are favorable for binding [86]. However, in this study, the high values of ΔEvdw reflect that the term ΔEvdw constitutes the main stabilizing force in the complexes, exceeding the electrostatic contribution ΔEele. These findings propose the structural viability of the formed complexes and suggest that CAP can interact favorably within the protein environment. Moreover, these findings suggest that although CAP can activate some of these targets in a TRPV1-dependent manner, it may also act through direct interactions.

In summary, the in silico results position CAP as a compound capable of interacting with different targets involved in AD and PD (independently of positive and negative effects). This fact opens future directions for research aimed at standardizing the administration of safe doses, exploring the role CAP may play in conjunction with pharmacological therapies used for the treatment and management of AD and PD, and understanding at which stages of these neurodegenerative disorders it may have a significant effect. Additionally, it is important to note that our findings were derived exclusively from network pharmacology, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics, indicating interactions between CAP and targets involved in AD and PD. Thus, these in silico predictions necessitate systematic experimental validation. We propose a rigorous evaluation of neuroprotective activity in AD and PD models using iPSC-derived or SH-SY5Y neurons that simultaneously explore the targets analyzed in this work. Subsequently, a thorough evaluation of its safety and efficacy should be conducted in animal models. Toxicological and pharmacokinetic analyses should be performed to corroborate its translational potential. Furthermore, we recognize the limitations inherent in the in silico approach, including reliance on databases with limited coverage, the inflexibility of docking models, the limited duration of molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns), and inaccurate entropy estimates from the MM/PBSA method.

In this study, a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis was conducted to elucidate and substantiate the anti-neurodegenerative properties of CAP. By constructing a pharmacological network, we identified IL6, GSK3B, CASP3, BCL2, ESR1, SIRT1, NGF, IGF1, and HMOX1 as potential therapeutic targets for CAP treatment. The exploration of GO functions indicated that CAP is involved in BP, such as the response to abiotic stimuli and the negative regulation of cell death; in cellular components, it is associated with genes encoding proteins present in the IGF1R complex and the death-inducing signaling complex; and in MFs, it is linked to cholinesterase activity and dopamine neurotransmitter receptor activity.

Molecular docking analysis demonstrated that CAP exhibits strong binding affinity to proteins associated with SIRT1, ESR1, HMOX1, and NGF. Furthermore, molecular dynamics studies on proteins revealed that SIRT1, ESR1, HMOX1, and NGF maintain stable interactions with CAP.

These findings suggest that these proteins could be therapeutic targets for AD and PD and that CAP could be a therapeutic agent. However, these bioinformatic predictions require further in vitro and in vivo experimental validation.

AChE: acetylcholinesterase

AD: Alzheimer’s disease

BBB: blood-brain barrier

BChE: butyrylcholinesterase

BCL2: apoptosis regulator Bcl-2

BP: biological processes

CAP: capsaicin

CASP3: caspase 3

CB: closeness betweenness

CC: closeness centrality

CTD: Comparative Toxicogenomics Database

ESR1: estrogen receptor 1

GO: gene ontology

GSK3B: glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta

HD: highest degree

HMOX1: heme oxygenase 1

IGF1: insulin-like growth factor 1

IGF1R: insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor

IL6: interleukin-6

MFs: molecular functions

MM/PBSA: Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area

NGF: nerve growth factor

PD: Parkinson’s disease

Rg: radius of gyration

RMSD: root-mean-square deviation

RMSF: root-mean-square fluctuation

ROS: reactive oxygen species

SASA: solvent-accessible surface area

SIRT1: sirtuin 1

SMILES: Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry Specification

TCMSP: Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology and Analysis Platform

TRPV1: transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

The supplementary tables for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1004132_sup_1.pdf.

Luis Antonio Ramirez-Contreras (CVU: 1319432), Luis Alfonso Hernández-Villaseñor (CVU: 629990), and Salvador Hernández-Estrada (CVU: 1319414) gratefully acknowledge the financial support for the scholarship from SECIHTI-México for Doctoral studies in the Biociencias program from the Centro Universitario de Los Altos (CUALTOS) of the University of Guadalajara. Andrés Frausto de Alba (CVU: 1272002) gratefully acknowledges the financial support for the scholarship from SECIHTI-México for Doctoral studies in the Ciencia y Tecnología program from the Centro Universitario de Los Lagos (CULAGOS) of the University of Guadalajara. Thanks to the Instituto de Investigación en Ciencias Médicas from CUALTOS for the infrastructure support, the Molecular Modelling and Materials area from Centro Universitario de Los Lagos (CULAGOS), and the University of Guadalajara’s Data Analysis and Supercomputing Centre (CADS) for the computational and technical support provided through the Leo Atrox supercomputer.

LARC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. LMAE: Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. SHE: Validation, Investigation, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. LAHV: Validation, Investigation, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. JMSJ: Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. LHH: Validation, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Supervision. GCH: Validation, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Supervision. AFdA: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Data related to capsaicin targets, Parkinson’s disease targets, and Alzheimer’s disease targets, among other data, supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 753

Download: 29

Times Cited: 0

Leonel Pereira, Ana Valado

Sharon Smith ... David Heal

Prerna Sarup ... Sonia Pahuja

Ekaterina P. Krutskikh ... Artem P. Gureev

Susmita Das ... Shylaja Hanumanthappa

Sneha Bagle ... Sadhana Sathaye

Agustina Lulustyaningati Nurul Aminin ... Muhammad Ajmal Shah