Affiliation:

1National Research Council, Institute for System Analysis and Computer Science “A. Ruberti”, 00185 Rome, Italy

2Experimental Neuroscience and Neurological Disease Models, Santa Lucia Foundation IRCCS, 00143 Rome, Italy

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7362-8307

Affiliation:

3Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Neuroscience, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198, USA

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4792-0416

Affiliation:

4Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3, Canada

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4796-140X

Affiliation:

5PeQuiM - Laboratory of Research in Medicinal Chemistry, Institute of Chemistry, Federal University of Alfenas, Alfenas 37133-840, MG, Brazil

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7799-992X

Affiliation:

5PeQuiM - Laboratory of Research in Medicinal Chemistry, Institute of Chemistry, Federal University of Alfenas, Alfenas 37133-840, MG, Brazil

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0324-2435

Affiliation:

6Instituto de Farmacologia e Neurociências, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa, 1649-028 Lisboa, Portugal

7Centro Cardiovascular da Universidade de Lisboa, CCUL (CCUL@RISE), Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa, 1649-028 Lisboa, Portugal

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4258-9397

Affiliation:

6Instituto de Farmacologia e Neurociências, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa, 1649-028 Lisboa, Portugal

7Centro Cardiovascular da Universidade de Lisboa, CCUL (CCUL@RISE), Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa, 1649-028 Lisboa, Portugal

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9030-6115

Affiliation:

8Neuroscience Theme, School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney NSW 2006, Australia

9Laboratory of Neurobiology and Pathological Physiology, Institute of Animal Physiology and Genetics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 602 00 Brno, Czech Republic

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9564-2799

Affiliation:

10Chief Medical Officer for Lutroo Imaging, LLC and Norroy North America, Ltd., Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1651-4212

Affiliation:

11Department of Neuroscience and Laboratory of Neuroscience, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, 20149 Milano, Italy

12Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, “Dino Ferrari” Center, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20122 Milano, Italy

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3977-6995

Affiliation:

11Department of Neuroscience and Laboratory of Neuroscience, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, 20149 Milano, Italy

12Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, “Dino Ferrari” Center, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20122 Milano, Italy

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7698-3854

Affiliation:

13Department of Biochemistry, Institute of Chemistry, University of São Paulo, Cidade Universitária, São Paulo CEP 05508-000, SP, Brazil

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3217-4166

Affiliation:

14International Joint Research Center on Purinergic Signalling, School of Health and Rehabilitation, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu 611137, Sichuan, China

15Tianfu Jincheng Laboratory, Chengdu 610212, Sichuan, China

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2543-066X

Affiliation:

13Department of Biochemistry, Institute of Chemistry, University of São Paulo, Cidade Universitária, São Paulo CEP 05508-000, SP, Brazil

14International Joint Research Center on Purinergic Signalling, School of Health and Rehabilitation, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu 611137, Sichuan, China

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

Email: henning@iq.usp.br

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2114-3815

Affiliation:

16Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CiberNed), National Institute of Health Carlos iii, 28031 Madrid, Spain

17Departament de Biochemistry and Molecular Biomedicine, University of Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain

18Institut de Química Teòrica i Computacional (IQTCUB), School of Chemistry, University of Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

Email: rfranco123@gmail.com; rfranco@ub.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2549-4919

Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2026;6:1004136 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2026.1004136

Received: August 17, 2025 Accepted: November 24, 2025 Published: January 04, 2026

Academic Editor: Shile Huang, Louisiana State University Health Science Center, USA

Neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, are characterized by multifactorial pathologies that extend beyond neuronal loss to include neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and glial dysregulation. Despite extensive research, disease-modifying therapies remain elusive, hindered by late diagnosis, limited availability of specific biomarkers, and the persistent dominance of reductionist, single-target strategies. This comprehensive and informative review provides a critical synthesis of integrated neuroprotective strategies, with particular focus on glial mechanisms and biomarker-guided interventions. Therapeutic emphasis is placed on coordinated mechanisms targeting both neurons and non-neuronal cells, such as astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. Emerging strategies are reported to include modulation of synaptic plasticity and neurotransmission, delivery of neurotrophic factors, activation of intrinsic cytoprotective pathways (e.g., Nrf2 signaling), restoration of proteostasis, and induction of regeneration via cellular reprogramming. Glial cells are discussed as therapeutic targets involved in inflammation, metabolism, myelination, and neuronal survival. Advances in predictive, preventive, personalized, and participatory (P4) medicine, supported by genomics, multi-omics, imaging, and real-world data, are presented as accelerating biomarker discovery and enabling earlier and more precise stage-specific interventions. Future success in combating neurodegeneration will depend on integrated approaches that combine protective, supportive, and regenerative strategies, appropriate for disease stage and patient profile. By reframing neuroprotection as a systemic, multicellular endeavor, this review highlights the potential to not only extend life expectancy, but also preserve meaningful quality of life in individuals affected by neurodegenerative diseases.

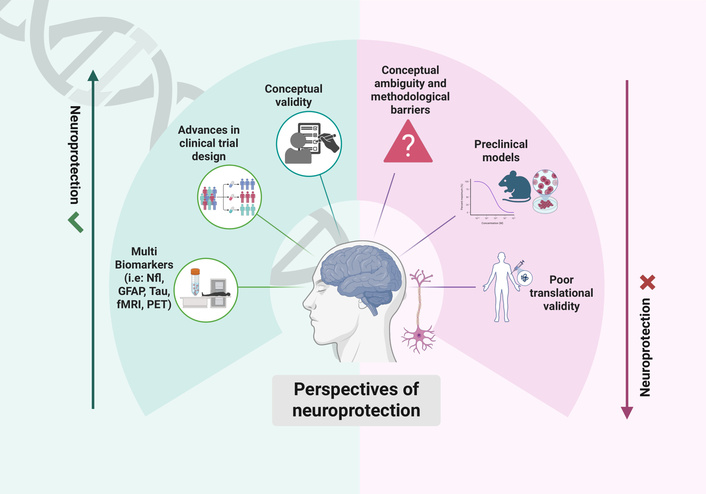

Neuroprotection remains a formidable challenge, as every central nervous system (CNS) insult, be it stroke, trauma, or neurodegenerative disease, activates multiple, overlapping injury pathways. This mechanistic complexity, coupled with the translational gap between animal models and clinical practice, has repeatedly undermined single-target strategies and continues to limit the development of effective therapies.

Factors such as age, genetic background, and pre-existing health conditions can significantly influence not only an individual’s response to CNS injury but also the efficacy of neuroprotective interventions. Despite promising outcomes in animal models, only a few neuroprotective treatments have gained approval for clinical use in humans. This underscores the urgent need for improved research strategies, careful selection of drugs, and suitably designed clinical trials. Moreover, the absence of reliable biomarkers to assess neuroprotection in humans further complicates progress in this field.

While every strategy has an intrinsic and often unavoidable limitations, at present we should keep focusing on the overall realization of our commitment to neuroprotection by: i) further enhancing the natural repair mechanisms and regenerative capacity of the CNS; ii) intervening earlier in the course of CNS injury to limit damage and improve outcomes; iii) adopting simultaneous application of a range of selective agents instead of single-targeted strategies, or by the provision of a single multi-target agent; iv) providing comprehensive supportive care crucial for neuroprotection beyond pharmacological interventions.

Under this perspective, as reported in a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 [1, 2], the age-standardized rates of deaths per 100,000 individuals attributed to 37 unique conditions affecting the nervous system that now include neurodevelopmental disorders, late-life neurodegeneration, and emergent conditions such as cognitive impairment following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has decreased by 33.6% from 1990 to 2021; age-standardized rates of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) attributed to these conditions has decreased by 27%. Nevertheless, the medical community and the society continue to face a staggering burden: In 2021, an estimated 3.4 billion people, representing 43.1% of the global population, were living with a neurological condition, which accounted for 11.1 million deaths and 443 million DALYs, making neurological diseases the leading cause of disability worldwide.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of major neurological disorders, moving beyond a neuron-centric view to incorporate the critical part that glial cells play in disease mechanisms and treatment. Additionally, we discuss emerging biomarkers, current challenges, and future directions in research. The structure of the text progresses from an analysis of specific diseases and their common pathways to a discussion of rationally designed neuroprotective strategies, aiming to bridge scientific knowledge and clinical applications and, hopefully, contribute to better patient outcomes in the future.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is primarily characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and subsequent depletion of dopamine in the nigrostriatal pathway. Clinically, PD presents with hallmark motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, resting tremor, rigidity, and postural instability. However, non-motor symptoms, ranging from cognitive impairment, mood disorders, sleep disturbances, autonomic dysfunction, to anosmia, are increasingly recognized as integral to the disease and often precede motor onset by years. This complex symptomatology reflects the widespread and multisystem nature of PD pathology, which extends far beyond the basal ganglia to involve cortical, limbic, and peripheral autonomic structures [3, 4].

Despite decades of research, PD remains incurable, and currently approved treatments are largely symptomatic. Dopaminergic therapies such as levodopa, dopamine agonists, and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors provide meaningful relief, particularly during the early stages of the disease, but their efficacy wanes over time [5]. Long-term use is frequently associated with debilitating motor complications, such as dyskinesias and fluctuations in symptom control [6]. Importantly, none of the available treatments address the underlying neurodegeneration, and disease progression continues unabated.

This lack of disease-modifying therapies highlights an urgent and unmet need for effective neuroprotective strategies capable of halting or slowing the loss of vulnerable neuronal populations. Multiple molecular mechanisms have been implicated in PD pathogenesis, including mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, impaired protein degradation pathways (ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosomal systems), excitotoxicity, calcium dysregulation, neuroinflammation, and abnormal alpha-synuclein aggregation. These processes do not act in isolation but instead converge and amplify one another in a complex interplay that underlies neuronal vulnerability and death. Parkinsonism can be linked to genetics in only a small subset of patients (for a recent review and examples of such conditions, see [7]). The synaptic accumulation and misfolding of alpha-synuclein is considered a pathological hallmark and propagates in a prion-like fashion through interconnected neural circuits [8, 9]. Except for a few isolated cases, no definitive factors capable of triggering the pathological process have been identified. Potential suspects, including environmental or industrial toxins, heavy metals, and illicit drugs, have been considered, but none have been conclusively implicated.

Neuroinflammation plays a key role in the progression of PD. Activated microglia release reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and other neurotoxic mediators that exacerbate oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage. In parallel, astrocytes and peripheral immune cells contribute to a sustained pro-inflammatory environment within the CNS. These chronic inflammatory responses are now understood not simply as bystanders but as active drivers of neurodegeneration. Targeting dysfunctional glial responses, restoring microglial homeostasis, and modulating peripheral immune infiltration represent promising avenues for intervention. Similarly, enhancing endogenous mechanisms of neuronal resilience, such as antioxidant defenses, trophic support, and mitochondrial biogenesis, may provide additional protection against ongoing insult [10–12].

Mitochondrial impairment also occupies a central role in PD. Dysfunction of mitochondrial complex I in the electron transport chain has been observed in post-mortem PD brains and in several experimental models. This dysfunction compromises cellular energy metabolism, increases oxidative stress, and triggers apoptotic cascades. In genetic forms of PD, mutations in genes such as PINK1, PARKIN, DJ-1, and LRRK2 further highlight the vulnerability of mitochondrial and proteostatic systems, offering potential therapeutic targets [7, 13, 14].

However, attempts to develop neuroprotective treatments have so far met with limited success. Several promising compounds have failed in clinical trials due to a range of challenges, including inadequate disease models, late intervention timing, insufficient biomarker validation, and difficulty in distinguishing symptomatic from neuroprotective effects. Furthermore, the clinical heterogeneity of PD, along with the absence of definitive diagnostic biomarkers in early stages, complicates patient stratification and endpoint definition in trials (see details in [15]).

Given these challenges, there is a growing consensus around the need for multimodal approaches to neuroprotection in PD. Rather than targeting isolated mechanisms, future therapies must consider the convergence of mitochondrial stress, protein aggregation, and neuroinflammation. Combination therapies, or single agents with pleiotropic actions, are increasingly being explored to interrupt the pathological cascade at multiple levels. In parallel, efforts are underway to identify early biomarkers, including those based on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), peripheral blood, imaging modalities, and multi-omic signatures, to enable earlier intervention, before extensive neuronal loss has occurred.

In sum, PD exemplifies the critical importance of neuroprotection in chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Its multifactorial pathophysiology, progressive trajectory, and lack of disease-modifying treatments underscore the need for early, multi-targeted, and personalized approaches. Advancing neuroprotective therapies in PD will not only impact millions of patients worldwide but also yield valuable insights applicable to other disorders marked by neuronal loss. This review will comprehensively explore these multifaceted pathological features from the perspective of neuroprotection.

Like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is marked by progressive neuronal degeneration, but with distinct molecular signatures and therapeutic challenges. AD is the most common cause of dementia worldwide and a leading contributor to disability and dependency among the elderly. It is clinically defined by progressive cognitive decline, particularly in memory, language, executive function, and orientation, which in time culminates in significant loss of independence and diminished quality of life. Behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms, including apathy, agitation, depression, and hallucinations, often accompany the cognitive decline and contribute significantly to disease burden [2].

Neuropathologically, AD is characterized by extracellular accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. These hallmark lesions appear years, if not decades, before symptom onset and are associated with synaptic dysfunction, progressive neuronal loss, and widespread cortical and hippocampal atrophy. However, AD pathology extends beyond amyloid and tau, encompassing a multifaceted array of pathophysiological mechanisms, including chronic neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired proteostasis (the homeostasis of protein folding, stability, and degradation), calcium dysregulation, excitotoxicity, and breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [16, 17].

Despite substantial advances in our understanding of these mechanisms, effective therapeutic options remain extremely limited. Current approved treatments, including acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antagonist memantine, offer only modest symptomatic relief without altering disease progression. Even recent anti-amyloid immunotherapies, while targeting one of the core pathologies of AD, have shown limited clinical benefit and raised concerns regarding safety, efficacy, and applicability across the disease spectrum. These limitations reinforce the urgent need for neuroprotective strategies that can preserve neuronal integrity, delay progression, and extend the functional lifespan of patients [18, 19].

A recent metallomic study has found significantly lower cortical lithium (Li) in mild cognitive impairment and AD with selective sequestration of Li within amyloid plaques, implying an early disturbance of endogenous Li homeostasis in vulnerable cortex while serum levels remain unchanged; this shift is supported across cohorts and fractionation analyses that show reduced Li in non-plaque parenchyma and correlations with memory performance [20]. In mouse models, dietary Li deficiency accelerates Aβ deposition, tau phosphorylation, microglial reactivity, synaptic and myelin loss, and memory decline; single-nucleus RNA-seq indicates broad, cell-type–specific transcriptomic changes that overlap human AD signatures, and several of these effects are partly mediated by increased GSK3β activity, as pharmacologic GSK3β inhibition reverses Li-deficiency phenotypes. As a replacement strategy, lithium orotate (LiO), reported to bind Aβ less avidly than lithium carbonate, raised parenchymal Li, reduced Aβ and phospho-tau, and improved synaptic/myelin markers and behavior at physiological Li levels in AD mice, though these salt-specific advantages and translational implications remain preclinical [21–23]. Despite mechanistic interest and some preliminary signals, clinical trials in AD have not provided evidence of therapeutic benefit from lithium, and its toxicity profile limits its practical use in patients. Taken together, disturbed Li homeostasis may contribute to early AD biology (potentially via GSK3β/β-catenin signaling and microglial/myelin vulnerability), but lithium is not an established AD therapy; rigorous human validation of brain target engagement, salt selection, and risk-benefit evaluation at clinically practical exposures is still required before efficacy claims are warranted.

The need for neuroprotection in AD is underscored by the disease’s long preclinical phase, during which silent pathological processes accumulate before any measurable symptoms emerge. This extended prodromal window offers a critical opportunity for early intervention, provided reliable biomarkers and predictive tools are in place. Neurodegeneration in AD follows a characteristic trajectory, starting in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus and gradually spreading to the associative neocortex. The degeneration of neurons in the ventral tegmental area, accompanied by reduced dopamine release and impaired connectivity in target regions, is recognized as a key feature of the early stages of AD, preceding even the formation of Aβ plaques. These alterations contribute to cognitive decline as well as to neuropsychiatric symptoms such as apathy and depression, which are frequently observed in patients [24–26]. Targeting early degenerative changes, such as synaptic loss, axonal transport disruption, mitochondrial compromise, and glial dysfunction, may prove more effective than attempting to reverse advanced neuronal death [27, 28].

Chronic inflammation, mediated by microglia and astroglia, is now recognized as a central driver of neuronal damage in AD. Notably, several risk genes associated with AD, including TREM2, CD33, CD36 and CR1, encode immune-related proteins, suggesting that immune dysfunction is not merely secondary but causally linked to disease pathogenesis. There is also increasing interest in neuroimmune modulation, with therapeutic strategies aiming to rebalance microglial activation states, prevent astrocyte-induced neurotoxicity, and limit peripheral immune cell infiltration. Additionally, efforts to enhance intrinsic neuronal protective mechanisms, through upregulation of neurotrophic factors, restoration of calcium homeostasis, or stabilization of synaptic plasticity, offer further promise [29, 30].

Neurons rely heavily on mitochondrial energy production, and in AD, early defects in mitochondrial dynamics, respiratory chain activity, and calcium buffering impair synaptic function and render neurons more vulnerable to stress. These deficits are compounded by oxidative damage, reduced antioxidant capacity, and accumulation of oxidized lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Protein misfolding and failure of clearance systems, including the autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome pathways, further compromise the cellular environment and lead to toxic intracellular accumulations [31, 32].

Despite the intricate interplay of pathological mechanisms in AD, therapeutic efforts have long prioritized Aβ targeting as a singular strategy. However, the consistent clinical failures of these reductionist approaches have prompted a paradigm shift toward multi-target interventions designed to concurrently modulate multiple facets of neurodegeneration. Therapy approaches include: i) novel small molecules and biologics with designed polypharmacology; ii) strategically repurposed drugs with established pleiotropic benefits; and iii) optimized lifestyle interventions. Particularly promising are agents that integrate complementary mechanisms, simultaneously mitigating neuroinflammation, counteracting oxidative stress, and preserving synaptic integrity, to address the disease’s multifactorial nature [33, 34].

One major challenge in advancing neuroprotective therapies in AD lies in trial design. Patient heterogeneity, long disease course, and variability in clinical presentation complicate recruitment, stratification, and outcome measurement. Furthermore, distinguishing genuine neuroprotective effects from symptomatic improvement requires the use of robust, disease-relevant biomarkers and long-term longitudinal studies. Nevertheless, advances in neuroimaging, fluid and blood-based biomarkers, and multi-omic profiling are beginning to enable more accurate staging, prognosis, and therapeutic targeting [35].

In conclusion, AD exemplifies the complexity and unmet clinical needs of neurodegenerative disorders. The progressive neuronal loss, limited treatment efficacy, and enormous social and economic burden underscore the critical importance of early, targeted, and multi-mechanistic neuroprotective approaches. A shift in focus from end-stage pathology to early intervention and neuronal preservation will be essential to transform the management of AD and improve outcomes for millions of affected individuals. Later, we will provide an in-depth analysis of these complex mechanisms, always from the perspective of neuroprotection.

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a rare, inherited neurodegenerative disorder with a known genetic etiology: the production of mutant huntingtin (mHTT) protein. Onset typically occurs in mid-adulthood, presenting a complex clinical picture. The motor syndrome encompasses involuntary choreiform movements, dystonia, and impaired coordination, often evolving into bradykinesia. This is accompanied by a range of psychiatric symptoms, including depression, irritability, and apathy, as well as progressive cognitive deficits in attention, executive function, and memory. Collectively, these symptoms lead to a progressive decline in the ability to perform daily activities and a significant deterioration in quality of life [36, 37].

The expansion of CAG trinucleotide repeats in the HTT gene results in the production of an mHTT protein containing an expanded polyglutamine sequence. Misfolded mHTT forms intracellular aggregates, disrupts cellular homeostasis, and triggers widespread neuronal dysfunction. The striatum, particularly the medium spiny neurons of the caudate nucleus and putamen, is the earliest and most severely affected brain region. As the disease progresses, cortical atrophy and white matter loss become more pronounced. Beyond the toxic gain-of-function effects of mHTT, HD pathogenesis involves a range of interconnected mechanisms, including mitochondrial dysfunction, transcriptional dysregulation, impaired autophagy, proteostasis failure, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and chronic neuroinflammation [38–43].

Despite a detailed understanding of the genetic basis of HD, effective therapeutic options remain extremely limited. Currently approved treatments such as tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine target only chorea and offer symptomatic relief without altering disease progression. Antisense oligonucleotides and gene-silencing approaches that directly target HTT expression are under investigation, yet have shown mixed results in clinical trials, with concerns about efficacy, safety, and delivery. These limitations highlight the need for broader neuroprotective strategies that can delay neurodegeneration, support neuronal survival, and preserve motor and cognitive function [44–46].

The need for neuroprotection in HD is particularly urgent given the protracted presymptomatic phase, during which subtle cognitive and psychiatric changes may precede overt motor symptoms by years. This long prodromal window presents a crucial opportunity for early therapeutic intervention, especially in individuals with a known genetic diagnosis. Neurodegeneration in HD follows a relatively stereotyped progression, beginning in the striatum and extending to other cortical and subcortical structures. Early changes include synaptic loss, dendritic spine retraction, mitochondrial fragmentation, and alterations in gene expression, all of which contribute to neuronal dysfunction before irreversible cell death [39, 41, 43].

Chronic neuroinflammation is increasingly recognized as a significant contributor to HD pathogenesis. Microglia in HD adopt a reactive, pro-inflammatory state, releasing cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and complement proteins that exacerbate neuronal injury. Astrocytes also exhibit dysfunctional phenotypes, including impaired potassium and glutamate buffering, which further compromise neuronal health. Notably, mHTT expression in glial cells may independently drive inflammatory responses and metabolic disturbances. Peripheral immune system alterations, including increased cytokine levels and immune cell infiltration, suggest a systemic component to the inflammatory process in HD [47–49].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is another hallmark of HD. mHTT impairs mitochondrial biogenesis, disrupts calcium handling, and promotes fission over fusion, leading to fragmented and inefficient mitochondria. These alterations reduce ATP production, increase oxidative damage, and render neurons more vulnerable to metabolic stress. In parallel, defective autophagic clearance and ubiquitin-proteasome system dysfunction result in the accumulation of toxic protein species and damaged organelles, perpetuating cellular toxicity [50–52].

Although much of the therapeutic focus in HD has centered on reducing mHTT levels, single-target approaches have yielded limited success, prompting interest in multi-modal strategies. These include i) small molecules with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, or neurotrophic properties, ii) lifestyle interventions such as exercise and diet and iii) cell-based therapies aimed at restoring lost neuronal populations or modulating the disease environment. Neuroprotective compounds that enhance mitochondrial function, reduce oxidative stress, and support proteostasis are also being explored in preclinical and early clinical studies [39, 53, 54].

A major barrier to progress in HD treatment development is the lack of robust biomarkers for disease progression and therapeutic response. However, recent advances in neuroimaging, body fluid biomarkers (such as neurofilament light chain—NfL), and digital phenotyping are beginning to enable more precise tracking of disease dynamics and individualized treatment approaches. Additionally, gene editing and RNA-targeting technologies offer hope for transformative therapies, though challenges remain in ensuring specificity, safety, and long-term efficacy [55–58].

In conclusion, HD illustrates the devastating consequences of single-gene mutations triggering a cascade of pathological events. The convergence of synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial failure, neuroinflammation, and impaired protein clearance underscores the complexity of the disease and the need for early, multi-mechanistic neuroprotective interventions. As research advances, integrating genetic, molecular, and clinical insights will be critical to developing effective therapies that not only alleviate symptoms, but also modify the course of the disease and improve the lives of patients and their families.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is a devastating multisystem neurodegenerative disease characterized by the degeneration of both upper (cortical) and lower (brainstem and spinal) motor neurons, leading to progressive voluntary muscle weakness and paralysis. Despite its rarity, ALS represents the most prevalent and studied motor neuron disease, with clinical onset and progression varying significantly across individuals. Symptoms typically begin with muscle weakness, cramping, or dysarthria, and progressively extend to involve swallowing and respiratory muscles. Both familial (fALS, 5–10% of cases) and sporadic (sALS) forms show similar clinical and pathological features, with overlapping cognitive and behavioral changes, particularly frontotemporal-like symptoms, as well as progressive bulbar and limb motor dysfunction.

Pathologically, ALS is characterized by motor neuron degeneration and a constellation of co-occurring molecular abnormalities, including excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, necrosis, altered proteostasis, impaired cytoskeletal trafficking, DNA damage, and dysfunctional RNA metabolism. Neuroinflammation may have an important role, sustained by aberrant crosstalk between neurons and glial cells. Microglia, astrocytes, and infiltrating macrophages remain chronically activated and secrete neurotoxic factors, while dysfunctional oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells fail to uphold myelin and metabolic support. This glial dysregulation perpetuates motor neuron death, contributing to the rapid and irreversible nature of the disease [59, 60].

Potential triggers range from environmental and industrial toxins [61] to the confluence of factors such as strenuous physical exercise and intermittent, high-intensity sound [62]. Associations with certain occupations (farmers, truck drivers, airline pilots/cabin crew, professional soccer players) have been proposed, though none are particularly strong [63–68]. Epidemiological studies are limited by small sample sizes and uncertain outcomes. It has recently been noted [69] that researching ALS faces formidable challenges, and overcoming these barriers will be essential for developing truly effective strategies for prevention and treatment.

Genetically, over 40 risk genes have been associated with ALS, with key mutations including those in C9ORF72, SOD1, TARDBP, and FUS. These mutations result in toxic gain- and loss-of-function effects, which impair essential cellular processes. Still, the initial molecular trigger, or “primum movens”, remains undefined, and it is likely that no single causative mechanism can account for the clinical and molecular heterogeneity observed in ALS patients. This multifactorial etiology supports the view of ALS as a “point of no return” disease, where the failure of therapies to halt disease progression reflects the deep complexity of its biology [59, 60].

Epidemiologically, the burden of ALS is rising worldwide. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021, ALS prevalence has increased by nearly 68% between 1990 and 2021, with incidence rising by 74.5% and associated DALYs by 105.5% [1]. Bayesian models forecast that although prevalence may plateau or modestly decline by 2040, mortality and overall disease burden will continue to rise, driven largely by population aging, especially in high-income countries [1] and increased environmental toxic compounds. This rising global impact underlines the urgency for better treatments and earlier diagnosis.

From a therapeutic standpoint, current interventions are limited. Riluzole remains the main approved therapy for ALS, despite yielding only modest survival gains through partial attenuation of glutamatergic excitotoxicity [70–73]. Edaravone (RADICAVA®), a free-radical scavenger, was approved in several countries after showing efficacy in a specific subgroup of early-stage ALS patients [74, 75]. More recently, tofersen (QALSODY®), an antisense oligonucleotide targeting mutant SOD1, has shown potential in reducing NfL levels and slowing functional decline, though concerns remain regarding inflammatory side effects and the failure of initial phase III trials [76–78].

Emerging candidates such as PrimeC, a combination of ciprofloxacin and celecoxib, have shown promising results in slowing progression and improving survival in phase II trials [79, 80]. Similarly, dazucorilant, a selective glucocorticoid receptor modulator, was granted “fast track” status after showing improved survival despite missing its primary endpoint [81]. Another promising molecule, Usnoflast (previously ZYIL1), targets the NLRP3 inflammasome, a key component of neuroinflammation, and has been successfully tested in phase IIa trials for ALS [82, 83]. The compound is currently being evaluated in phase IIb trials.

Altogether, ALS exemplifies the profound complexity of neurodegenerative diseases characterized by neuronal loss. It underscores the limitations of single-targeted treatments and highlights the urgent need for multi-target approaches, search for clinical markers to enable early diagnosis, and robust clinical trial designs. Continued advances in omics technologies and biomarker discovery are essential to understand the intricate pathophysiology of ALS and to develop more effective and personalized neuroprotective strategies.

Stroke, particularly ischemic stroke, is a leading cause of adult disability and death worldwide, characterized by the sudden interruption of cerebral blood flow and the subsequent cascade of energy failure, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and neuronal death [84–87]. Unlike chronic neurodegenerative diseases such as PD, AD, HD or ALS, which involve slowly progressive and multifactorial neuronal loss, stroke represents an acute insult where the timing of intervention is critical. In this context, neuroprotection primarily depends on the rapid restoration of cerebral perfusion, typically through thrombolytic or endovascular therapies. Time-sensitive management is therefore the most effective strategy to limit irreversible damage and preserve neuronal integrity [84]. Given these distinct pathophysiological dynamics and therapeutic priorities, stroke will not be discussed further in this review, which focuses instead on chronic neurological diseases characterized by progressive neuronal loss, complex molecular interactions, and the need for sustained neuroprotective strategies.

While reshaping our way to connect basic science to clinical needs, we are currently witnessing new trends in drug discovery, sustained by several recent achievements obtained, for instance, in the field of “predictive-preventive-personalized-participatory (P4) medicine”. These trends have profound roots dating back to antiquity and the philosopher and skillful physician of the classical Greek period, Hippocrates, sometimes considered the father of Western medicine. In his “Hippocratic Corpus”, compiled centuries before the advent of precision medicine, Hippocrates had set up the foundations of what we would now call a personalized approach to healthcare, having done so even in the absence of the sophisticated diagnostic tools that are available today. Hippocrates was indeed the first to emphasize concepts such as individual patient needs, the role of lifestyle, and the body’s natural functions and development. Maintaining that diseases are a combination of environmental factors, diet, and living habits, Hippocrates appears to have anticipated the four principles of P4 medicine [88], which seeks to individualize care according to each patient’s distinctive biological and sociocultural profile.

P4 medicine strives to improve treatment effectiveness and clinical outcomes by a more holistic approach that carefully considers individual differences that contrasts with more traditional “one size fits all therapy”. The ongoing transformation is already evident; in 2020, 42% of the clinical trials in the USA were biomarker-based, compared to only 5% in 2005. The accelerated drug approval introduced by the FDA in 2024 was probably made possible by growing acceptance of precision medicine and genetic screening in targeted therapies, for instance, those for non-small-cell lung cancer and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, by approving zenocutuzumab-zbco (brand name Bizengri®, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-zenocutuzumab-zbco-non-small-cell-lung-cancer-and-pancreatic), and for transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis causing cardiomyopathy and heart failure, by approving acoramidis (brand names Attruby and Beyonttra, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-drug-heart-disorder-caused-transthyretin-mediated-amyloidosis).

The P4 medicine paradigm continues to demonstrate its value across chronic diseases, even as attention increasingly shifts toward rare disorders. Common conditions such as diabetes, obesity, mental health disorders, and metabolic dysfunctions are poised to reap the greatest rewards from this new era in drug discovery. At the same time, rapid advances in genomics, electronic health records, digital health technologies, and data-driven research are leading a parallel surge in neurotherapeutics, an area with many urgent but unmet needs.

Neuroscientists can use genomic and proteomic data to identify individuals at risk long before the appearance of symptoms. Research continues for identifying molecular triggers and environmental factors that could predict the risk of developing diseases such as AD, PD, HD, ALS, Multiple Sclerosis (MS), epilepsy and others. Using predictive data, P4 medicine [88] can guide lifestyle changes and tailor treatments to each patient’s genetic background, environment, medication response, and disease course. These personalized strategies aim to prevent or slow neurological decline, improve symptom control, reduce adverse effects, and enhance overall outcomes. Looking ahead, patients will be better informed, encouraged to provide feedback, and closely monitored to optimize therapeutic results.

In addition to genetic data, large studies should look at the expression of relevant genes (proteomics) and the molecular pathways/processes in which the gene products are involved (e.g., metabolomics, receptor-associated cascades, growth factor effects, kinases, and many more), thus constantly improving our understanding of the neuropathological mechanisms and uncovering novel targets.

The future of clinical research in neuroscience, therefore, lies in collecting real-world data and using them as catalysts for clinical trial design and in further development of individually-tailored treatment procedures.

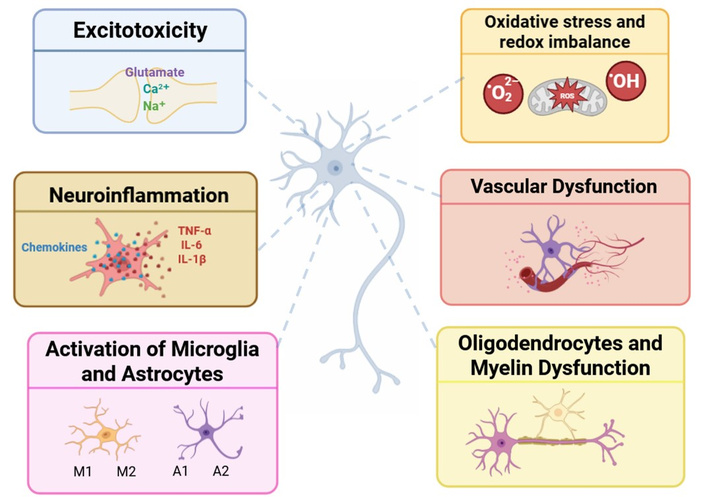

The nervous system is susceptible to diverse disruptions that impair homeostasis, whether locally or systemically. Below, we examine key mechanisms underlying neuronal degeneration, highlighting how they drive cellular damage (Figure 1). Like the entire review, this section concentrates on chronic, progressive diseases.

Schematic representation of the integrated mechanisms contributing to neuronal damage in neurodegenerative diseases. This diagram illustrates the main cellular and molecular mechanisms of primary neuronal damage in neurodegenerative conditions. Excitotoxicity: Excessive glutamate release resulting in sodium and calcium influx, which impairs neuronal viability. Neuroinflammation: Release of chemokines and cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. Activation of Microglia and Astrocytes: These cells can adopt phenotypes with distinct functions. Microglia M1 promotes inflammation and neurotoxicity, while the M2 phenotype supports tissue repair and anti-inflammatory signaling. A1 astrocytes show a neurotoxic profile, contributing to synaptic loss, whereas A2 astrocytes exhibit neuroprotective properties. Oxidative stress and redox imbalance: Accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a decrease in antioxidant activity disrupts mitochondrial functions and promotes cellular damage. Vascular Dysfunction: Compromise of the blood-brain barrier integrity leads to impaired nutrient and oxygen supply, contributing to neuronal dysfunction. Oligodendrocytes and Myelin Dysfunction: Degeneration of oligodendrocytes disrupts myelin sheath integrity, leading to impaired axonal action potential conduction and neural integrity. Altogether, these interrelated mechanisms create a pathological environment and further progressive neuronal damage, forming the biological basis of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell illustrations were generated with the assistance of Sora, an AI-based image generation platform.

Excitotoxicity was one of the first mechanisms of neuronal damage that was identified. The word, allegedly coined by John Olney, refers to neuronal injury caused by excessive excitatory stimulation, particularly prolonged cellular depolarization [89]. This process commonly involves the main excitatory neurotransmitter of the nervous system, glutamate. This overstimulation results in excessive sodium and calcium influx, causing persistent neuronal depolarization [90]. Excitotoxicity may occur when, for instance, extracellular glutamate accumulates due to impaired uptake by astrocytes or excessive synaptic release. The glutamate-induced persistent depolarization affects mitochondrial membrane polarization, impairing mitochondrial function and energy metabolism (see section Oxidative stress and redox imbalance in the CNS, and [91]).

Three primary ionotropic glutamate, NMDA, alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isooxazole-propionate (AMPA), and kainate receptors [92], can trigger excitotoxic cascades. While overstimulation of any of these receptors may contribute to excitotoxicity, excessive calcium influx via NMDA and AMPA receptors is particularly harmful. Ion influx activates enzymes such as endonucleases, phospholipases, and proteases, damaging both the plasma and mitochondrial membranes of the neuron. Excitotoxic mechanisms are implicated in various conditions, including ALS, AD, PD, epilepsy, and traumatic brain or spinal cord injury [91]. Other triggers include hypoglycemia that may affect brain energy metabolism [93].

β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), a naturally occurring weak agonist of glutamate receptors, has been implicated in age-related neurological disorders, though its exact role remains debated due to insufficient evidence [94, 95]. Similarly, dietary intake of β-N-oxalyl-amino-L-alanine (BOAA), a plant-derived excitotoxin and potent agonist of ionotropic glutamate receptors, induces lathyrism, a neurodegenerative disease characterized by irreversible motor dysfunction due to spinal cord damage [96]. In ALS, the dysfunctional uptake of glutamate by astrocytic transporters contributes to excitotoxicity at least in a subset of ALS patients [97], however, simple inhibition of glutamate transport failed to produce an ALS-like condition in animals (see section The classical view: microglia as engines of inflammation for more details).

Experimental models frequently employ the natural neurotoxin kainic acid to trigger excitotoxic neuronal death, providing a well-established paradigm for studying neurodegeneration [98].

Notably, emerging evidence suggests that excitotoxicity may synergize with immune dysregulation, exacerbating neuronal vulnerability and accelerating disease progression [99].

Although present at appreciable levels in the brain, the role of aspartate remains poorly understood [100]. This amino acid is a potent excitatory agent acting primarily through NMDA receptors [101]. However, the risk of aspartate-induced excitotoxicity has not been fully evaluated. A critical gap is that aspartate does not appear to have been tested directly at metabotropic G protein-coupled glutamate receptors (mGluRs) [100]. Because activation of mGluRs is known to confer neuroprotection by limiting glutamate-induced excitotoxicity [102–107], aspartate’s apparent failure to activate these receptors would leave this protective mechanism unengaged. This absence of mGluR-mediated buffering could make aspartate a particularly potent excitotoxin, underscoring the need for further investigation.

Although excitotoxicity results from exacerbated excitatory transmission, it is important not to forget the relevance of GABAergic transmission and how GABAergic system modulators may affect neuronal plasticity and/or protect against cognitive decline after brain insults. Recent reviews have highlighted this issue [108, 109].

Inflammation is a protective immune response to infection or tissue injury. However, in the CNS, this process, termed neuroinflammation, differs fundamentally from peripheral inflammation. Unlike classical inflammation (characterized by heat, redness, and pain), neuroinflammation primarily involves the release of pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g., cytokines, chemokines, and ROS) by resident immune cells, particularly microglia, the CNS’s innate immune effectors [110, 111]. Notably, astrocytes also contribute by amplifying inflammatory signaling under pathological conditions.

In certain neurological disorders, T lymphocytes can infiltrate the CNS by crossing the BBB, where they exacerbate neuroinflammatory responses through pro-inflammatory cytokine release and glial cell activation. While this mechanism is most prominent in MS, growing evidence implicates T cell involvement in other neurodegenerative diseases as well [112].

Chronic neuroinflammation arises when persistent stimuli, including genetic mutations, pathological protein aggregates (e.g., Aβ and α-synuclein), traumatic injury, or neurotoxic exposure, convert an otherwise transient, protective inflammatory response into a sustained and maladaptive state. This chronic activation impairs neuronal homeostasis, worsens synaptic dysfunction, and ultimately accelerates neurodegenerative processes [113–116].

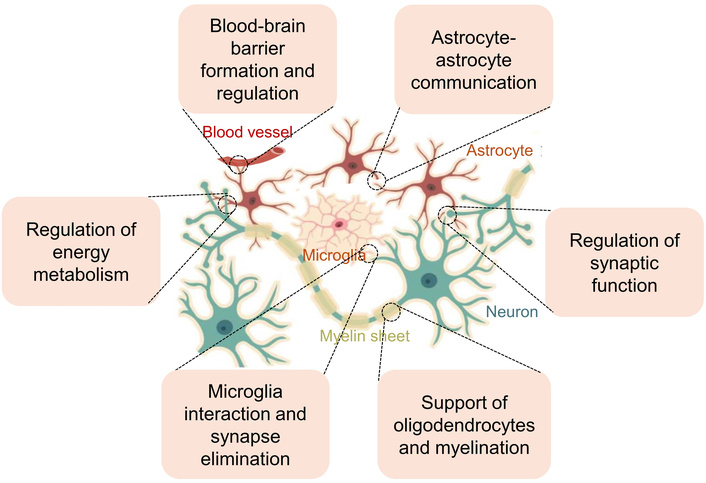

Glial cells, i.e., microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, are essential for supporting and modulating neuronal function [117, 118]. Recent single-cell transcriptomic studies have revealed unexpected heterogeneity within glial populations [119]. Though traditionally viewed as immune-privileged, the CNS possesses its own immune defenses, with microglia acting as the primary immune effectors and constituting the predominant “immune” population in the CNS [120]. These cells constantly monitor the local environment and initiate inflammatory signaling in response to disruption [121]. Depending on stimuli, microglia can adopt distinct phenotypes: the M1 pro-inflammatory state (induced by lipopolysaccharide and characterized by production of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and the M2 anti-inflammatory state (induced by IL-4 or IL-13, promoting repair) [122, 123]. While this M1/M2 classification oversimplifies microglial diversity, it remains useful for distinguishing functional profiles [124, 125]. More recent transcriptomic studies have described additional phenotypes, including disease-associated microglia (DAM), which are characterized by downregulated homeostatic genes and upregulated inflammatory ones [126]. The possibility of M2 microglia has led to new therapeutic opportunities that are covered in another section of this review.

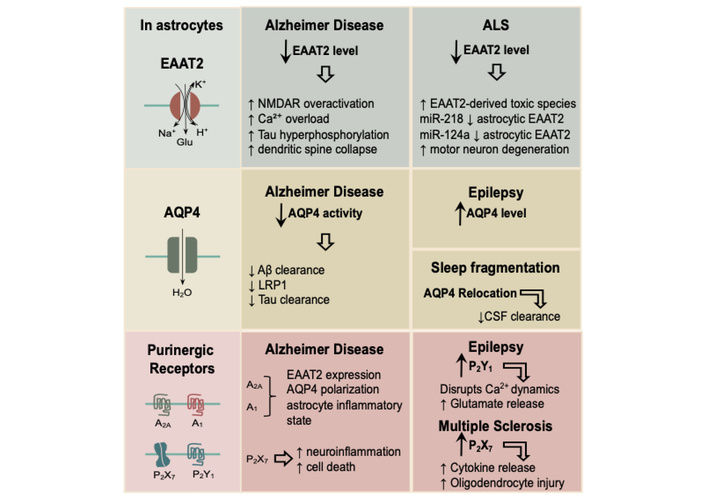

Astrocytes are star-shaped glial cells critical for neuronal support, ionic homeostasis, neuroprotection, and synaptic regulation [127]. Despite being discovered alongside neurons, astrocytes remained understudied for decades. More recent advances have revealed their essential roles in CNS development, physiology, and disease pathogenesis [128]. These cells display intricate arborization patterns and form extensive gap junction-coupled networks that dynamically regulate synaptic activity, pH balance, and cerebral microcirculation. Astrocytes are fundamental components of both the BBB and the glymphatic waste clearance system [129–131]. In pathological conditions, astrocytes undergo significant molecular and morphological remodeling, adopting either a detrimental A1 (neurotoxic) or beneficial A2 (neuroprotective) reactive state that, respectively, drives injury progression or promotes tissue repair [132, 133]. The identification of these dichotomous astrocytic states, particularly the reparative A2 phenotype, has revealed promising therapeutic targets that will be examined in later sections of this review.

Astrocytes participate in glutamate clearance, converting it into glutamine, and play a key role in antioxidant defense. Under stress conditions, astrocytes may release toxic factors that amplify neuronal damage [134]. Dysfunctional microglia may fail to eliminate pathogens or apoptotic cells and may trigger maladaptive inflammatory responses [135, 136].

Oligodendrocytes, which make up about 20% of brain cells, produce and maintain myelin. Their dysfunction has been implicated in AD, where notable myelin alterations are reported [137]. Additionally, oligodendrocytes contribute to regulation of neuroinflammation, neuronal metabolic support, and stress response. They are active participants in neurodegenerative pathophysiology, as evidenced by transcriptomic studies [138].

Oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells ensure proper signal conduction by maintaining myelin and providing trophic support to axons. Damage or degeneration of oligodendrocytes is directly implicated in MS [139], and in ALS and frontotemporal dementia [140].

A critical initiating event in neuroinflammation is the detection of homeostatic disturbances within the CNS. This recognition is mediated by specialized molecular sensors, including pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), activated by damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecules produced upon exogenous threats and endogenous danger signals, subsequently activating inflammatory cascades [141, 142].

While glial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases (AD, PD, HD) primarily emerges as a consequence of underlying pathology, it nevertheless creates a self-perpetuating cycle that exacerbates disease progression. Through sustained release of pro-inflammatory mediators and impaired neuroprotective functions, dysfunctional glia amplify neuronal damage, effectively accelerating the neurodegenerative process [143].

Glial cells and neurons maintain dynamic communication via signaling molecules (cytokines, neurotransmitters, ROS, NO, glutamate) and extracellular vesicles containing proteins, mRNA, and miRNA. These vesicles can propagate toxic proteins like tau and β-amyloid and influence the progression of neurodegenerative diseases [144, 145].

Crosstalk between astrocytes and microglia has neuroprotective potential. In PD models, suppressing microglia-induced conversion of astrocytes to the A1 neurotoxic phenotype preserved dopaminergic neurons [146]. In vitro, astrocyte-to-microglia transfer of protein aggregates improved clearance [147]. However, in disease states, this interaction may turn maladaptive, promoting inflammation and neurodegeneration.

Neuronal death in neurodegeneration occurs via multiple mechanisms: apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis. Apoptosis involves caspase-3-mediated protein degradation without inflammation [148]. Necroptosis, triggered when apoptosis is impaired, involves receptor-interacting protein kinases (RIPK) 1 and 3, and the mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL), resulting in membrane rupture and inflammatory signaling [149]. Pyroptosis, in contrast, involves caspase-1 activation by inflammasomes like NLRP3, leading to cytokine release and membrane permeability increase [150, 151]. In PD and AD, pyroptosis is associated with elevated inflammatory cytokines and Aβ-mediated inflammasome activation [152, 153]. Ferroptosis is increasingly recognized as a distinct mechanism of regulated cell death contributing to age-related neurodegenerative disorders. Its involvement adds an epigenetic layer to neuronal vulnerability, potentially driving the progressive neuronal loss observed in conditions such as AD [154, 155]. Pathways leading to cell death release DAMPs, fueling further neuroinflammation. Modulating glial activity and these death pathways may offer therapeutic avenues. Current research is focused on targeting inflammasomes, glial signaling, and regulated cell death as strategies to mitigate neurodegeneration [156].

Oxidative stress is a key pathological feature of neurodegenerative diseases. It arises from an imbalance between the production of ROS and the body’s antioxidant defenses [157]. The CNS is particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage due to its high oxygen consumption, abundance of polyunsaturated fatty acids, and relatively low levels of antioxidant enzymes [158]. Understanding how oxidative stress contributes to disease mechanisms is essential for developing effective neuroprotective strategies [159], targeting neurons and glial cells.

Molecular oxygen is vital for energy production and cellular signaling. However, its metabolism can generate ROS, which include both radical (e.g., superoxide O2•–, hydroxyl radical •OH) and non-radical species (e.g., hydrogen peroxide H2O2) [160]. Nitrogen species such as the nitric oxide radical (NO•) and the peroxynitrite (ONOO–) also contribute to oxidative damage [161].

ROS are mainly produced in mitochondria during aerobic respiration, especially at complexes I and III of the electron transport chain [162, 163]. Other sources include nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases, xanthine oxidase, peroxisomes, and enzymes associated with the endoplasmic reticulum [164, 165].

Physiologically, ROS act as signaling molecules involved in proliferation, immunity, and plasticity. They modulate redox-sensitive pathways such as those mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and some tyrosine phosphatases. For example, during infection, ROS activate immune cells and stimulate cytokine release [166]. Nitric oxide plays roles in blood flow regulation, neurotransmission, and immune responses [167]. Dysregulation of redox homeostasis leads to ROS accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, disrupted iron metabolism, and DNA damage, ultimately contributing to oxidative stress [168–170].

ROS can induce lipid peroxidation, particularly in the presence of iron, triggering ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death [171]. Aβ oligomers exacerbate this process, producing reactive aldehydes like 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) that damage proteins and contribute to neurodegeneration [172]. Iron, though essential for mitochondrial respiration and neurotransmitter synthesis, can generate ROS when dysregulated. Excess iron accumulation is linked to oxidative damage in AD, PD, and other neurodegenerative diseases [173, 174]. Compared to other organs, the brain has reduced levels of catalase and glutathione peroxidase activity, impairing its ability to neutralize H2O2 and other electrophilic compounds [175, 176]. DNA damage caused by ROS, such as base oxidation and strand breaks, disrupts genomic stability. When repair mechanisms fail, neuronal apoptosis may ensue [177]. Indeed, oxidative DNA damage markers like 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) are elevated in AD [178–180].

This vulnerability is compounded by an age-dependent decline in endogenous antioxidant defenses, contributing significantly to neuronal dysfunction and neurodegenerative pathogenesis. Critical roles in maintaining redox are exerted by antioxidant systems, including the thioredoxin/peroxiredoxin systems and the nuclear erythroid related transcription factor 2 (Nrf2), which regulates the expression of detoxification proteins such as Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) [181].

Notably, Nrf2 plays a dual protective role by both repressing neuroinflammatory signaling and promoting the transcription of antioxidant genes, establishing it as a compelling therapeutic target in neurodegenerative disorders [182, 183]. Intriguingly, antioxidant defense mechanisms in the CNS diverge substantially from those in peripheral tissues such as erythrocytes, where the glutathione–NADPH system is well characterized and robust. In contrast, the CNS’s antioxidant architecture remains only partially understood, and its complexity is heightened by neuronal heterogeneity and limited regenerative capacity. As highlighted elsewhere [184], neurons rely heavily on astrocytes for redox balance, creating a compartmentalized and interdependent defense system. This cell-specific reliance introduces unique vulnerabilities during oxidative stress episodes. Moreover, while the glutathione system is present in neural cells, its relative importance compared to other detoxification strategies remains unclear. Current therapeutic approaches aim to modulate these pathways, including direct Nrf2 activation and glial-targeted interventions, although significant challenges persist in delivering antioxidant agents across the BBB and in validating neuroprotection markers. These limitations underscore the need for further mechanistic insights and innovative delivery strategies to fully harness neuroprotective potential of targeting Nrf2-mediated pathways.

Although oxidative stress constitutes a unifying pathological feature among major neurodegenerative diseases, the molecular pathways through which it drives neuronal injury appear to be disease specific. A striking and still unresolved observation is that the most vulnerable neuronal populations differ markedly across disorders, affecting distinct brain regions such as the hippocampus in AD, the substantia nigra in PD, or the motor cortex and spinal cord in ALS. These differences likely reflect complex interactions among region-specific neuronal subtypes, glial responses, genetic predispositions, and disease-specific triggers, each contributing to unique patterns of redox imbalance. Deciphering these divergent mechanisms is essential for developing targeted, pathology-specific antioxidant therapies [185].

The defining pathological feature of PD is the selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta [4, 186]. While the precise mechanisms remain incompletely understood, these neurons exhibit particular vulnerability to oxidative stress due to their high basal metabolic activity, autonomous pacemaking requiring intense calcium cycling, and ROS generation during dopamine metabolism [187]. This susceptibility is compounded by impaired redox homeostasis and multiple pathogenic factors: i) dysfunctional protein clearance mechanisms involving PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), Parkin, and α-synuclein proteostasis; ii) mitochondrial impairment leading to ROS accumulation; and iii) environmental exposures to toxins like pesticides and heavy metals [188–190]. Together, these elements create a self-reinforcing cycle of oxidative damage, protein aggregation, and neuronal degeneration that characterizes PD progression.

In AD, oxidative stress also plays a central role promoting Aβ accumulation and tau phosphorylation [191] and impairing proteostasis (the homeostasis of protein folding, stability, and degradation), synaptic plasticity and other processes critical for learning and memory [188, 192]. Based on findings from the CRND8 mouse model, in which amyloid deposits are associated with neuropathological changes, it is conceivable that similar mechanisms, potentially involving the accumulation of metal ions such as copper, iron, or zinc, could also occur within amyloid plaques in human patients [193, 194].

An informative account of the causes of neuronal-death-vulnerability that can be deduced from familial cases of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases has been described elsewhere [195].

HD is due to a CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene. While huntingtin folds and functions normally, the mutant form exhibits aberrant folding, leading to aggregation and neuronal toxicity. The mHTT protein interacts improperly with other cellular proteins, disrupting normal biological functions. ROS exacerbate the misfolding process, promoting the accumulation of protein aggregates near neuronal axons and dendrites, ultimately impairing synaptic communication [196]. Mitochondrial Ca2+ handling is also disrupted, leading to the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and the release of cytochrome c, which triggers apoptosis. This imbalance is also associated with excessive superoxide production and mitochondrial DNA damage [197].

Cytoplasmic protein aggregates, a pathological feature of ALS, disrupt key cellular degradation mechanisms, including both the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy pathways, resulting in catastrophic failure of protein homeostasis. Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from accumulation of trans-activation response element DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43) increases the production of ROS, causing oxidative stress and establishing a vicious cycle that contributes to disease progression. Thus, oxidative stress emerges as a central mechanism in the disease pathogenesis, interconnected with proteostatic and mitochondrial dysfunction [198, 199].

A detailed understanding of the distinct pathophysiological mechanisms and redox imbalances underlying each neurodegenerative disorder is crucial for advancing personalized therapeutic strategies, enabling interventions tailored to the specific cellular vulnerabilities and molecular drivers of each disease.

Disruptions in cerebral perfusion, whether due to trauma, ischemia, or hemorrhage, are well-established drivers of acute neuronal injury. The neurovascular unit, composed of endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytic end-feet, and vascular smooth muscle cells, plays a central role in regulating cerebral blood flow and maintaining the integrity of the BBB. These components are essential for ensuring nutrient delivery and shielding neural tissue from circulating toxins and inflammatory mediators [200]. Loss of BBB integrity in prodromal or early symptomatic phases may exacerbate neuroinflammation and accelerate neuronal loss [201].

However, despite this contributory role, it is not reasonable to propose direct therapeutic targeting of vascular dysfunction or BBB endothelial cells as a primary strategy for treating neurodegenerative disorders. These structures, while involved in disease progression, are not the root cause of neuronal degeneration and remain challenging to modulate without risking systemic side effects or impairing essential barrier functions. Therefore, therapeutic efforts are better directed toward neuronal and glial targets, which more directly govern disease onset and progression.

Independent of the trigger of neurodegeneration leading to AD, PD, HD or ALS, common pathological themes emerge: excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, glial and vascular dysfunction, often interacting in complex, cascading patterns. Understanding these interconnected processes is vital for developing strategies to halt or reverse neurodegeneration and protect neuronal integrity in aging and disease.

The convergence of excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and immune dysregulation highlights the multifactorial nature of neuronal damage. A key advancement in addressing these mechanisms is the shift from a neuron-centric to a holistic view that encompasses the critical role of glial cells, a perspective that informs the diverse therapeutic toolkit explored in the following sections.

Neurons are the principal cellular targets in most neurodegenerative diseases, and their progressive loss accounts for the irreversible nature of clinical decline in conditions such as AD, PD, HD, and ALS. Neuron-focused therapeutic strategies seek to prevent degeneration, enhance survival, and restore function. However, these approaches face inherent challenges: Neurons have limited regenerative capacity, are highly susceptible to metabolic stress, and require preservation of precise synaptic connectivity for proper network integration.

This section presents current neuron-targeted therapeutic strategies, organized along a conceptual axis from extracellular modulation (e.g., receptor activation and trophic signaling) to intracellular mechanisms (e.g., signal transduction, transcriptional regulation and metabolic support). Particular attention is given to interventions that enhance synaptic plasticity, activate intrinsic neuroprotective pathways, and promote functional network regeneration (Figure 2).

Neuron-targeted therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases. This diagram summarizes four key classes of neuron-directed interventions designed to counteract neurodegeneration and support functional recovery. Enhancing Synaptic Plasticity (top left, blue): Modulation of AMPA and NMDA receptors boosts excitatory synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation (LTP). These strategies aim to restore synaptic strength essential for memory, learning, and network dynamics. Neurotrophic Factor Delivery (top right, orange): Administration of trophic molecules like BDNF and CDNF, either via receptor activation (e.g., TrkB) or exosome-based delivery, promotes neuronal survival, synaptic stability, and overall network resilience. Activating Intrinsic Neuronal Defense (bottom left, blue): Engaging cellular pathways such as Nrf2 and SIRT1 enhances antioxidant capacity, mitochondrial function, and autophagic clearance. These self-defense mechanisms help shield neurons from oxidative damage and protein misfolding. Stimulating Regeneration and Connectivity (bottom right, orange): Techniques like PTEN inhibition and neuromodulation (e.g., deep brain stimulation or chemogenetics) promote axonal growth and reconstitution of neural circuits. Together, these therapeutic domains represent a multifaceted approach to treating neurodegenerative conditions such as AD, PD, and ALS. Neuron icon by Vecteezy (https://www.vecteezy.com/).

One of the earliest consequences of neurodegeneration is the loss of synaptic strength and plasticity. Synaptic plasticity is a fundamental process underlying cognitive functions such as learning and memory [202]. Synaptic alterations are a hallmark of numerous neurological and psychiatric disorders, making the restoration of synaptic efficacy a central therapeutic goal [203, 204]. Enhancing plasticity can help stabilize circuit function, compensate for neuronal loss, and delay clinical deterioration. This subsection explores therapeutic strategies designed to boost synaptic adaptation, including receptor modulation, epigenetic tuning, and activity-based interventions.

Among pharmacological approaches, positive allosteric modulation of AMPA receptors using AMPAkines (e.g., aniracetam, CX516) has shown promise. AMPA receptors mediate fast excitatory neurotransmission, and their potentiation enhances excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs), promoting long-term potentiation (LTP), the cellular correlate of learning and memory [205, 206]. AMPAkines increase channel open time without directly activating the receptor, and may also elevate neurotrophic factors such as BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), contributing to neuronal survival and synaptic remodeling [207]. Consequently, AMPA receptor potentiation is being investigated as a therapeutic strategy for cognitive dysfunction in AD, schizophrenia, and depression.

NMDA receptors are likewise critical for calcium-dependent synaptic plasticity. Their activation permits calcium influx and initiates intracellular signaling cascades involving calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII), cAMP Response Element Binding Protein (CREB) and MAPK, culminating in the transcription of genes required for long-lasting synaptic enhancement [208]. Nonetheless, overstimulation of NMDA receptors can trigger excitotoxic damage, necessitating tightly controlled modulation. Therapeutic strategies under investigation include partial agonists (e.g., D-cycloserine) and modulators of the glycine co-agonist site, which may enhance plasticity while minimizing toxicity. NMDA receptor dysfunction seems implicated in schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, autoimmune cognitive syndromes, and age-related cognitive decline. In AD, subtype-specific NMDA receptor antagonists or allosteric modulators may protect against excitotoxic injury and support synaptic integrity [209–211]. Memantine, a currently approved NMDA receptor modulator, has demonstrated modest symptomatic benefit in AD patients but does not significantly alter disease progression [212–214].

In addition to receptor modulation, epigenetic regulation of plasticity-related genes offers another therapeutic frontier. Expression of key genes such as BDNF and Arc is governed by histone acetylation and DNA methylation, processes controlled by enzymes like histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [215, 216]. Pharmacological or behavioral modulation of these pathways may reactivate transcriptional programs essential for synaptic restructuring.

Physical interventions such as aerobic exercise and intermittent fasting promote synaptic plasticity via metabolic reprogramming and increased BDNF expression [217–219]. Furthermore, non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), have demonstrated potential in reversing cortical atrophy and enhancing plasticity [220–222].

While synaptic plasticity defines the adaptability of neural circuits, neurotransmission ensures signal fidelity and integration across brain networks. Neurodegenerative diseases often disrupt neuromodulatory pathways, further impairing cognitive and motor functions. This section focuses on pharmacological strategies that enhance neurotransmitter signaling and modulate network activity to support function and recovery.

Neuromodulatory systems constitute key therapeutic targets for cognitive enhancement [223]. The cholinergic system, essential for attention, learning, and cortical plasticity, is profoundly disrupted in AD [224]. Early therapeutic efforts using muscarinic receptor agonists like xanomeline were limited by peripheral side effects. However, recent approaches that pair xanomeline with trospium, a peripherally acting muscarinic antagonist, have improved tolerability and clinical efficacy, leading to regulatory approval [225, 226]. Additionally, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., donepezil) and both muscarinic and nicotinic receptor agonists support cholinergic tone and enhance cognitive performance [227].

Dopaminergic signaling plays a central role in working memory, motivation, and goal-directed behavior. Dopamine D1 receptor agonists and reuptake inhibitors such as methylphenidate are used to enhance prefrontal cortex function and are effective in conditions such as PD and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [228]. The noradrenergic system, particularly through α2A-adrenergic receptor signaling, modulates executive function and emotional regulation. Agents such as guanfacine (an α2A adrenergic agonist) and atomoxetine, a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, have demonstrated clinical efficacy in improving attention and working memory, and are used in the treatment of ADHD and post-traumatic stress disorder [223, 229].

In summary, the therapeutic modulation of neuromodulatory systems provides a diverse toolkit to enhance synaptic function. These approaches, ranging from receptor-targeted pharmacology to systemic neuromodulation, can be integrated with molecular and epigenetic interventions. Future strategies will likely emphasize combinatorial regimens, optimized in terms of target hierarchy, temporal dynamics, and dosage to maximize benefit while minimizing adverse effects.

Building on the modulation of neurotransmitter systems, another crucial dimension of neuroprotection involves sustaining the cellular environment that allows neurons to survive, adapt, and thrive. This includes not only neurotransmission but also the support of neurotrophic factors that promote neuronal health and synaptic maintenance. The section explores how such trophic support, alongside intrinsic resilience mechanisms and regenerative capacity, can be leveraged therapeutically.

BDNF plays a pivotal role in enhancing synaptic efficacy and promoting neurogenesis, particularly in glutamatergic circuits [230, 231]. BDNF signaling is frequently downregulated in neurodegenerative conditions, and strategies to restore its levels have demonstrated improvements in synaptic integrity and cognitive outcomes [129, 130]. Cleavage of the signaling receptor for BDNF, the tropomyosin receptor kinase B-full length (TrkB-FL), occurs in human tissue and in animal models of brain diseases [232]. Prevention of that cleavage may, therefore, prove a way to go towards novel therapies to halt neurodegeneration. Important in this context is the recent development of drug, a small TAT-TrkB peptide, that prevented TrkB-FL cleavage, improved cognitive performance, ameliorated synaptic plasticity deficits and prevented Tau pathology progression in vivo in a mouse model of AD [233].

Another key neurotrophic factor, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), has demonstrated significant neuroprotective effects in preclinical models of PD. GDNF exerts its protection by binding to the GDNF family receptor α-1 (GFRα) and c-Ret receptor complex, thereby maintaining the function and survival of dopaminergic neurons [234–236]. More recently, endoplasmic reticulum stress-regulating neurotrophic factors such as mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor (MANF) and cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor (CDNF) have emerged as promising agents. These proteins help maintain proper proteostasis and attenuate endoplasmic reticulum stress, thereby supporting dopaminergic neuron viability [237, 238].

Additional neurotrophic factors, including insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and nerve growth factor (NGF), exert complementary effects by regulating cellular metabolism, promoting anti-apoptotic pathways, and enhancing myelination [239, 240]. Despite their therapeutic promise, clinical translation has been hindered by the difficulty of achieving effective delivery into the brain. The BBB remains the major obstacle, and even molecules capable of crossing it often do so inefficiently or without reaching therapeutically relevant concentrations. To overcome this limitation, new delivery platforms are under development. Extracellular vesicles, constituted by exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells, can encapsulate BDNF, GDNF, and related factors, facilitating their transport across the BBB with minimal immunogenicity [241, 242]. In parallel, vectors consisting of adeno-associated viruses (AAV) provide a gene therapy-based approach for sustained, localized expression of neurotrophic factors in target brain regions [243, 244]. Other approaches include small-molecule mimetics and lifestyle interventions, such as phenolic-rich diets, which may enhance endogenous neurotrophin production [245–247].

A novel and increasingly compelling area of research involves the neuroimmune interface, particularly the role of regulatory T cells (Tregs). In preclinical neurodegeneration models, Tregs provide dual benefits: Suppression of neuroinflammatory cascades and induction of neurotrophic factor release, including CDNF, via crosstalk with neural substrates [248–250]. This immunomodulatory mechanism highlights a promising therapeutic avenue that bridges the immune and nervous systems.

Emerging paradigms consist of a convergence of molecular, cellular, and systemic strategies aimed at optimizing neurotrophic support. The integration of gene therapy, targeted delivery vehicles, and immune-based modulation offers a sophisticated framework to counteract neuronal loss and functional decline in neurodegenerative disorders.