Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacology, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal 576104, Karnataka, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3287-1332

Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacology, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal 576104, Karnataka, India

2Independent Researcher, Bengaluru 560060, Karnataka, India

Email: glv_000@yahoo.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9944-4888

Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacology, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal 576104, Karnataka, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6653-4660

Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacology, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal 576104, Karnataka, India

Email: Anoop.kishore@manipal.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8116-8408

Affiliation:

2Independent Researcher, Bengaluru 560060, Karnataka, India

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-9368-2672

Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2025;5:1004125 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2025.1004125

Received: July 16, 2025 Accepted: October 28, 2025 Published: December 05, 2025

Academic Editor: Marcello Iriti, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy

The article belongs to the special issue Natural Products in Neurotherapeutic Applications

Background: This study aims to assess oral alpha lipoic acid’s (ALA’s) safety and effectiveness in managing diabetic neuropathy.

Methods: A thorough search of the literature was conducted using PubMed, Google Scholar, and Embase databases, and the study was performed as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results: Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, nine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comprising 1,345 subjects were selected. The results showed that ALA has shown significant reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) [inverse variance (IV): –0.66, (–0.81 → –0.51) at 95% CI, p < 0.00001, I2 = 92%], neuropathy impairment score (NIS) [IV: –1.19, (–2.28 → –0.09) at 95% CI, p = 0.03, I2 = 58%], along with improving the neuropathy symptoms and change (NSC) number [IV: –0.18, (–0.35 → –0.01) at 95% CI, p = 0.04, I2 = 0%], NSC severity score [IV: –0.65, (–0.83 → –0.48) at 95% CI, p < 0.00001, I2 = 89%], total severity score (TSS) [IV: –0.43, (–0.59 → –0.27) at 95% CI, p < 0.00001, I2 = 98%], neurological disability score (NDS) [IV: –0.72, (–1.03 → –0.40) at 95% CI, p < 0.00001, I2 = 98%], vibration perception threshold (VPT) [IV: –0.35, (–0.50 → –0.19) at 95% CI, p < 0.0001, I2 = 96%] and global satisfaction [Mantel-Haenszel (M-H) odds ratio (OR): 3.51, (1.06 → 11.61) at 95% CI, p = 0.04, I2 = 72%] when compared to the control or placebo group. However, ALA has not shown significant changes in motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV) score [IV: 0.26, (–0.44 → 0.96) at 95% CI, p = 0.47, I2 = 49%] and NIS-low limb (NIS-LL) [IV: –0.58, (–1.35 → 0.19) at 95% CI, p = 0.14, I2 = 0%] when compared to the placebo group.

Discussion: Based on the available moderate to high-quality evidence, we can conclude that oral administration of ALA at doses of 600–1,800 mg may be beneficial in improving/alleviating the symptoms resulting from diabetic neuropathy.

Diabetic neuropathy (DN) is a common diabetes complication, resulting in peripheral nerve dysfunction from prolonged hyperglycemia [1]. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimates that over 475 million people worldwide have diabetes, and more than half of them are affected with DN [2]. In India, diabetes prevalence is 8.9%, with DN affecting 18.9–61.9% of diabetics [3]. Globally, DN impacts ~132 million people, which is ~1.9% of the world’s population [4].

DN is a major cause of diabetic mortality and economic burden, leading to 50–70% of non-traumatic amputations [5]. It progresses silently, causing delayed detection. Symptoms include lower limb pain, numbness, paraesthesia, burning sensations, motor dysfunction, and muscle weakness [6].

Managing DN is challenging due to a lack of curative treatments. Current therapies focus on diabetes control and symptom relief but lead to financial burden and side effects [7, 8]. Oxidative stress from hyperglycemia damages nerves, highlighting the potential of plant-derived compounds [5]. Among these, alpha lipoic acid (ALA) has demonstrated potential in alleviating neuropathic symptoms via antioxidant properties and improved microcirculation [5].

Furthermore, Hsieh et al. (2023) [9] published a meta-analysis (MA) on this topic; however, we identified several limitations: (1) Their inclusion criteria specified only studies using the oral route of ALA, yet they included Ametov et al. (2003) [10], which used the intravenous route. (2) Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were to be included, yet they accepted Garcia-Alcala et al. (2015) [11], a randomized withdrawal open-label study that lacked a proper placebo/control group. (3) They excluded the ALADIN II trial by Reljanovic et al. (1999) [12], a 2-year multicentric double-blind RCT that met their criteria. (4) Their analysis was limited to four parameters [total severity score (TSS), neurological disability score (NDS), neuropathy impairment score (NIS), and global satisfaction], ignoring several other relevant assessments available in the included studies.

Additionally, Baicus et al. (2024) [13] conducted an MA on ALA’s effects on diabetic peripheral neuropathy, but based their conclusions on only three RCTs. Notable limitations of their study included a minimum ALA intervention duration of six months and a restriction to studies published before September 11, 2022.

Given these significant shortcomings in the existing meta-analyses, there is a clear need for a more robust and thorough systematic review (SR) and MA aimed at evaluating the safety and efficacy of orally supplemented ALA in alleviating DN.

Keywords like “diabetic-neuropathy” AND “alpha lipoic acid” OR “ALA” OR “thioctic acid” AND “randomized controlled trials” were used to search the literature for research published up until December 2022 in a number of online databases, including PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar. The emphasis was only on published RCTs related to the topic. The publications that satisfied the inclusion criteria were taken into consideration for an SR/MA after all of the articles were reviewed at the abstract and full-length article levels. SD and GLV have performed a literature search, and co-authors were consulted prior to the final selection of articles for the SR and MA.

The population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design (PICOS) framework was used to define the inclusion and exclusion criteria, summarized in Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Category | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Patients with type II diabetes (both men and women), the age group of 18 years and above, and patients with established diabetic neuropathy are included | Severe neuropathy, myopathy, vascular disease, hepatic or renal disease, antioxidant therapy, alcoholism, drug abuse, hypothyroidism, neoplastic disorders, Parkinsonism, uremia, acute or chronic musculoskeletal disorders, foot ulcers, pregnancy, lactation, or child-bearing age without birth control devices, cardiovascular disorder |

| Intervention | Stand-alone oral ALA (dosage: 600–1,800 mg/day) | A combination of drugs, routes other than oral, and combination routes is not included |

| Comparator | Placebo-controlled group | Other than in the inclusion criteria |

| Outcome | Efficacy and safety parameters | Other than in the inclusion criteria |

| Study type | Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | Preclinical studies, systematic reviews, observational studies, retrospective clinical trials, conference proceedings, book chapters, review articles |

| Language | Only English | Other than in the inclusion criteria (all other languages other than English are excluded from the study) |

ALA: alpha lipoic acid.

Primary outcomes included glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), NIS, NIS-low limb (NIS-LL), neuropathy symptoms and change (NSC), TSS, motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV), neuropathy symptom score (NSS), NDS, vibration perception threshold (VPT), and global satisfaction. The secondary outcomes, which are adverse drug reactions, are summarized to conclude the safety of ALA.

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Revman version 5.4.1), which identifies six potential bias issues. Biases were classified as high, low, or unknown for each item, with studies considered to have poor quality if they presented three or more significant risks of bias. Three reviewers (SD, GLV, and AK) independently assessed each study’s profile, and a fourth reviewer was consulted to resolve any discrepancies in the bias rankings.

Evidence quality for each parameter was assessed using the GRADE Profiler version 3.6 and the consensus of SD and GLV [14]. Initially rated as high, RCT quality could be downgraded based on factors like inconsistency, publication bias, imprecision, indirectness, and risk of bias. The system classifies evidence into four levels: high, moderate, low, and very low [14–16].

Numerical data was extracted directly from tables, while data from graphs was obtained using the built-in measurement tool in Adobe Acrobat XI. Additionally, a default standard deviation of 10% of the mean was applied for both the ALA and control when the standard deviation was unavailable.

MA was conducted using RevMan version 5.4.1, with a fixed/random effects model and mean difference (MD)/standardized MD (SMD) for continuous variables, estimating inverse variance (IV). The pooled prevalence was calculated at a 95% CI, and I2 was used to assess heterogeneity. A sensitivity analysis was performed, incorporating only high-quality studies to enhance the robustness of the conclusions.

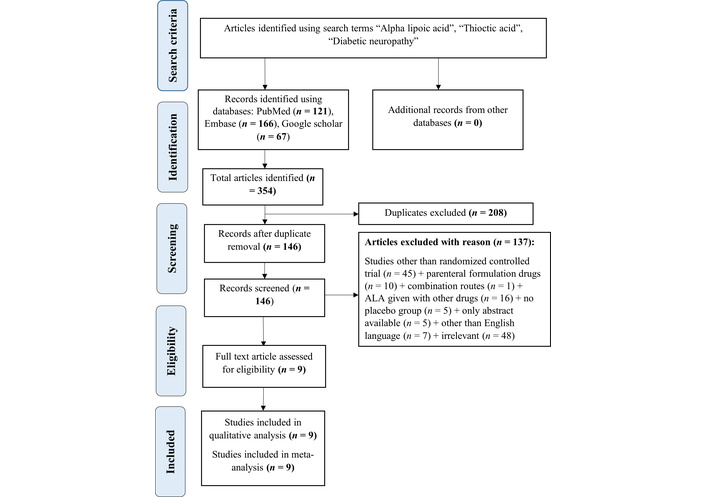

After removing duplicates, 146 articles were retained from a total of 354, sourced from databases such as PubMed (121), Embase (166), and Google Scholar (67). Of these, 137 articles were excluded for various reasons, including parenteral routes (10), combination routes (1), studies other than RCTs (45), other than English language (7), ALA given with other drugs (16), irrelevant topics (48), and no placebo group (5). Additionally, only abstracts were available (5). Ultimately, 9 RCTs involving 1,345 participants were included for this MA. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is depicted in Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart. From 354 initially identified articles (PubMed: 121, Embase: 166, Google Scholar: 67), 208 duplicates were removed. After screening, 137 articles were excluded, resulting in 9 randomized controlled trials. Source: https://www.prisma-statement.org/. This work is licensed under CC BY. PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; ALA: alpha lipoic acid.

The SR and MA comprised nine RCTs comparing intervention and placebo groups; the sample sizes ranged from 20 to 460. Participants aged 18 to 74 were included, with studies published between 1999 and 2021 from the USA, India, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Germany. The review focused on individuals with DN, excluding other conditions listed in Table 1. The attributes of the included studies are shown in Table 2.

Description of included studies.

| Sl. No. | Author name | Dose, route, duration (number of subjects) | Sample size (number of subjects) | Intervention | Parameters | Safety | Outcomes and conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ziegler et al., 2011 [29] | 600 mg, oral route, 4 years | Control = 224ALA = 230 | ALA, once daily | HbA1C, NIS-LL, NIS, MNCV, NSC, VPT, TSS | Adverse effects were more common with ALA, yet the placebo group had a higher incidence of deaths. | ALA shows improvement in NIS and NIS-LL, but MNCV and SNAP are seen. ALA slows the progression of DSPN but doesn’t improve the condition. |

| 2 | Ziegler et al., 2006 [26] | 600 mg, 1,200 mg, 1,800 mg, oral route, 5 weeks | Control = 43ALA 600 = 45ALA 1,200 = 47ALA 1,800 = 46 | ALA, once daily | HbA1C, NIS, NIS-LL, NSC, TSS, global satisfaction | Adverse events in the treatment group were dose-dependent, with the highest incidence observed in the 1,800 mg group. | ALA shows improvement in TSS, NSC, NIS, and NIS-LL parameters when compared with the placebo group. |

| 3 | Reljanovic et al., 1999 [12] | 600 mg, 1,200 mg, oral route, 24 months | Control = 20ALA 600 = 27ALA 1,200 = 18 | ALA | HbA1C, MNCV | Treatment-related adverse effects were noted. But the overall tolerability assessment was rated as very good or good. | Improvement in MNCV is seen in the ALA 1,200 mg group. |

| 4 | El-Nahas et al., 2020 [30] | 600 mg, two times daily (1,200 mg/day) oral route for 6 months | Control = 100ALA = 100 | ALA | HbA1C, NSS, NDS, VPT, VAS | Nausea. | ALA is effective, safe, and tolerable for the treatment of DPN. |

| 5 | Ruhnau et al., 1999 [31] | 600 mg, three times daily, oral route (1,800 mg/day) for 3 weeks | Control = 12ALA = 12 | Thioctic acid (ALA) | HbA1C, TSS, NDS | No adverse effects seen. | Short-term treatment with oral ALA ameliorates neuropathic symptoms. |

| 6 | Vijayakumar et al., 2014 [18] | 600 mg, oral route, 3 months | Control = 10ALA = 10 | ALA | HbA1C, MNCV | No data available. | Oral ALA improves MNCV in DN patients. |

| 7 | Siddique et al., 2021 [28] | 600 mg, oral route, 6 months | Control = 55ALA = 55 | ALA | HbA1C, TSS | No data available. | Significant improvement in TSS was seen. ALA improved symptoms of neuropathy pain and enhanced QOL. |

| 8 | Millan-Guerrero et al., 2018 [37] | 1,200 mg, oral route, 4 weeks | Control = 49ALA = 51 | ALA | MNCV | No adverse effects seen. | No clinically significant improvement was seen. |

| 9 | Tang et al., 2007 [27] | 600 mg, 1,200 mg, 1,800 mg, oral route, 5 weeks | Control = 43ALA 600 = 45ALA 1,200 = 47ALA 1,800 = 56 | ALA | Global satisfaction | Nausea, vomiting, and vertigo. | ALA is effective in reducing neuropathic symptoms in DSPN. |

ALA: alpha lipoic acid; HbA1C: glycated hemoglobin; NIS: neuropathy impairment score; NIS-LL: NIS-low limb; MNCV: motor nerve conduction velocity; NSC: neuropathy symptoms and change; TSS: total severity score; SNAP: sensory nerve action potential; VPT: vibration perception threshold; NDS: neurological disability score; NSS: neurological symptom scale; VAS: visual analogue scale; DSPN: diabetic distal symmetric polyneuropathy; DPN: diabetic peripheral neuropathy; DN: diabetic neuropathy; QOL: quality of life.

Two studies, Ametov et al. (2003) [10] and Ziegler et al. (1999) [17], were excluded from the analysis because Ametov et al. (2003) [10] was an intravenous route study, while Ziegler et al. (1999) [17] administered ALA intravenously for an initial 3 weeks followed by oral route exposure up to 6 months (combination of oral and intravenous routes).

Among the included trials, Reljanovic et al. (1999) [12] involved an initial 5-day intravenous course followed by 24 months of oral treatment. As the oral phase represented the primary intervention period, the study was included to capture one of the longest-duration RCTs of oral ALA.

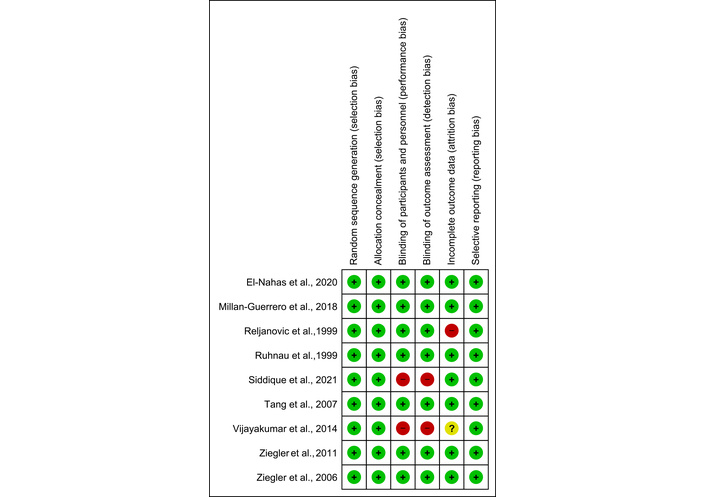

The risk of bias assessment indicated that only 1 out of the 9 studies included had low-quality evidence [17]. The risk of bias has been illustrated in Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph. The risk of bias assessment indicated that only 1 out of the 9 studies included had low-quality evidence.

The GRADE analysis revealed that the included studies ranged from moderate to high quality, and the analysis is presented in Table 3.

GRADE evidence profile: ALA compared to placebo/control.

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | ALA | Control | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| HbA1C (follow-up 3 weeks to 48 months; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | Serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong association2 | 377 | 364 | - | SMD 0.66 lower (0.81 to 0.51 lower) | High | Critical |

| Neuropathy impairment score (NIS) (follow-up 5 weeks to 48 months; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Randomised trials | Serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong association3 | 276 | 267 | - | MD 1.19 lower (2.28 to 0.1 lower) | High | Important |

| Neuropathy impairment score-lower limbs (NIS-LL) (follow-up 5 weeks to 48 months; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Randomised trials | Serious4 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 275 | 267 | - | MD 0.58 lower (1.35 lower to 0.19 higher) | Moderate | Important |

| Motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV) (follow-up 4 weeks to 48 months; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | Serious5 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 318 | 303 | - | MD 0.26 higher (0.44 lower to 0.96 higher) | Moderate | Important |

| Neuropathy symptoms and change (NSC) number (follow-up 4 weeks to 48 months; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Randomised trials | Serious | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 276 | 267 | - | SMD 0.18 lower (0.35 to 0.01 lower) | Moderate | Critical |

| Neuropathy symptoms and change (NSC) severity (follow-up 4 weeks to 48 months; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Randomised trials | Serious4 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 276 | 267 | - | SMD 0.65 lower (0.83 to 0.48 lower) | Moderate | Critical |

| Total severity score (TSS) (follow-up 3 weeks to 48 months; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomised trials | Serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Very strong association2 | 343 | 334 | - | SMD 0.43 lower (0.59 to 0.27 lower) | High | Critical |

| Neurological disability score (NDS) (follow-up 3 weeks to 6 months; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Randomised trials | No serious risk of bias | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 112 | 112 | - | MD 0.72 lower (1.03 to 0.4 lower) | High | Critical |

| Visual perception threshold (VPT) (follow-up 6 months to 48 months; better indicated by lower values) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Randomised trials | Serious4 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | Strong association2 | 324 | 330 | - | SMD 0.35 lower (0.5 to 0.19 lower) | High | Critical |

| Global satisfaction (follow-up mean 5 weeks) | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Randomised trials | Serious4 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 57/102 (55.9%) | 24/86 (27.9%) | OR 3.51 (1.06 to 11.61) | 297 more per 1,000 (from 12 more to 539 more) | Moderate | Critical |

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence: high quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. 1: Two of the included studies have a high risk of bias; 2: the outcomes are highly significant and large; 3: the outcomes are significant and large; 4: one of the included studies has a high risk of bias; 5: three included studies have a high risk of bias. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; CI: confidence interval; HbA1C: glycated hemoglobin; OR: odds ratio; MD: mean difference; SMD: standardized MD.

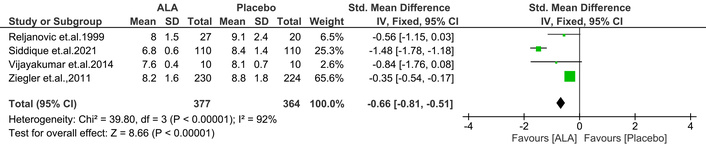

This test measures glucose control over the past three months, aiding in diabetes diagnosis and monitoring glycemic control [18, 19]. Maintaining controlled HbA1C levels reduces the likelihood of DN. In this context, ALA was linked to a significant reduction in HbA1C levels [IV: –0.66, (–0.81 → –0.51) at 95% CI, p < 0.00001, I2 = 92%] compared to placebo (Figure 3).

Effect of ALA on glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) levels in diabetic patients. ALA supplementation significantly reduced HbA1C compared to placebo (IV: –0.66; 95% CI: –0.81 to –0.51; p < 0.00001; I2 = 92%), indicating improved glycemic control. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

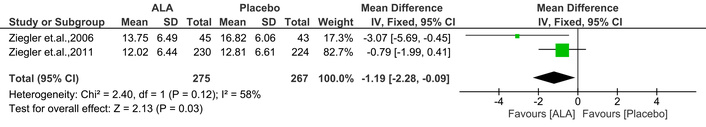

NIS evaluates neuropathy progression, with scores ranging from 0 to 244, where higher scores reflect more impairment [20]. The current MA found that ALA significantly reduced the NIS score [IV: –1.19, (–2.28 → –0.09) at 95% CI, p = 0.03, I2 = 58%] compared to placebo (Figure 4).

Effect of ALA on neuropathy impairment score (NIS) in diabetic patients. ALA treatment significantly reduced NIS compared to placebo (IV: –1.19; 95% CI: –2.28 to –0.09; p = 0.03; I2 = 58%), indicating improvement in neuropathic symptoms. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

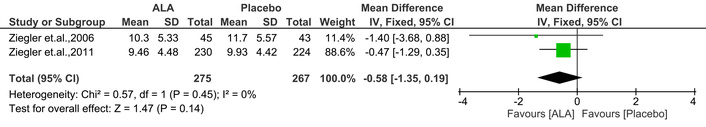

NIS-LL assesses lower limb neuropathy with 14 evaluations, scoring from 0 to 88, where higher scores denote more impairment [20]. This MA indicated that ALA administration showed a trend toward reducing NIS-LL scores, but the effect was not statistically significant [IV: –0.58, (–1.35 → 0.19) at 95% CI, p = 0.14, I2 = 0%] compared to placebo (Figure 5).

Effect of ALA on neuropathy impairment score-lower limb (NIS-LL) scores assessing lower limb neuropathy. ALA treatment showed a non-significant trend toward score reduction compared to placebo (IV: –0.58; 95% CI: –1.35 to 0.19; p = 0.14; I2 = 0%), suggesting limited impact on lower limb neuropathy. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

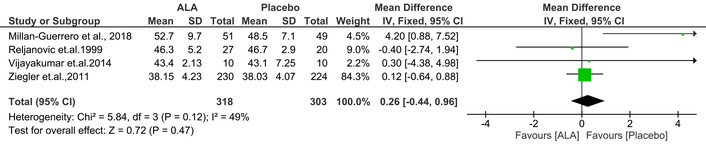

This test evaluates nerve conduction capacity by passing the electric impulses through the nerves. In general, the slower and weaker signal indicates that there is damage in the nerve. The available evidence suggests that ALA is not beneficial in improving the MNCV [IV: 0.26, (–0.44 → 0.96) at 95% CI, p = 0.47, I2 = 49%] compared to placebo [21] (Figure 6).

Effect of ALA on motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV). ALA showed no significant improvement in MNCV compared to placebo (IV: 0.26; 95% CI: –0.44 to 0.96; p = 0.47; I2 = 49%), indicating limited impact on nerve conduction function. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

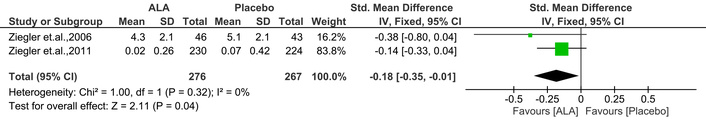

This score is derived based on the responses given by the patients to a questionnaire containing 38 items. A higher score indicates more severity [22]. This MA found that ALA significantly reduced the NSC number [IV: –0.18, (–0.35 → –0.01) at 95% CI, p = 0.04, I2 = 0%] compared to placebo (Figure 7).

Effect of ALA on neuropathy symptoms and change (NSC) number. ALA significantly reduced NSC scores compared to placebo (IV: –0.18; 95% CI: –0.35 to –0.01; p = 0.04; I2 = 0%), suggesting a modest improvement in patient-reported neuropathic symptoms. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

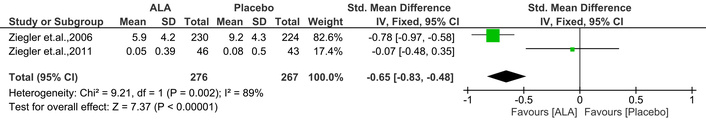

It is another parameter related to NSC, where severity is assessed. In this study, ALA significantly improved the NSC severity score [IV: –0.65, (–0.83 → –0.48) at 95% CI, p < 0.00001, I2 = 89%] compared to placebo. The outcomes are shown in Figure 8.

Effect of ALA on neuropathy symptoms and change (NSC) severity. ALA significantly reduced NSC severity scores compared to placebo (IV: –0.65; 95% CI: –0.83 to –0.48; p < 0.00001; I2 = 89%), indicating an improvement in symptom severity. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

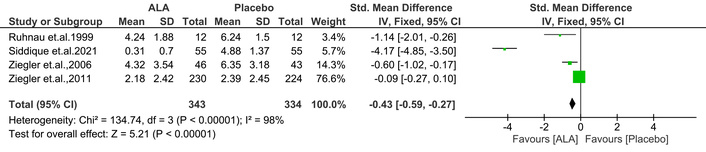

The TSS is a questionnaire used to assess the frequency and severity of sensory neuropathy symptoms [23]. Notably, ALA significantly improved the TSS [IV: –0.43, (–0.59 → –0.27) at 95% CI, p < 0.00001, I2 = 98%] compared to placebo (Figure 9).

Effect of ALA on total symptom score (TSS) for sensory neuropathy. ALA significantly reduced TSS compared to placebo (IV: –0.43; 95% CI: –0.59 to –0.27; p < 0.00001; I2 = 98%), indicating a notable improvement in symptom frequency and severity. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

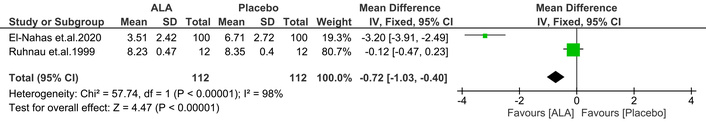

The NDS is a common tool for screening DN, evaluating vibration, pain, temperature perception, and ankle reflex, with scores from 0 to 10. Scores of 3–5 indicate mild symptoms, 6–8 moderate, and 9–10 severe [24]. This MA found that ALA significantly improved NDS compared to placebo [IV: –0.72, (–1.03 → –0.40) at 95% CI, p < 0.00001, I2 = 98%] (Figure 10).

Effect of ALA on neuropathy disability score (NDS). ALA significantly improved NDS compared to placebo (IV: –0.72; 95% CI: –1.03 to –0.40; p < 0.00001; I2 = 98%), indicating reduced neuropathic disability in diabetic patients. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

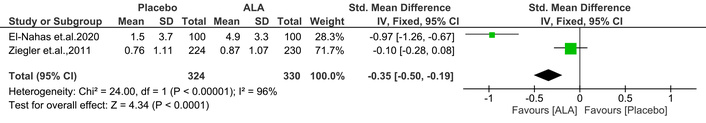

It is a common method for evaluating large fiber function in diabetic patients is the VPT. Serious DN problems are indicated by a high VPT [25]. Notably, ALA treatment significantly improved VPT compared to placebo [IV: –0.35, (–0.50 → –0.19) at 95% CI, p < 0.0001, I2 = 96%] (Figure 11).

Effect of ALA on visual perception threshold (VPT). ALA treatment significantly improved VPT compared to placebo (IV: –0.35; 95% CI: –0.50 to –0.19; p < 0.0001; I2 = 96%), indicating enhanced large fiber nerve function in diabetic patients. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

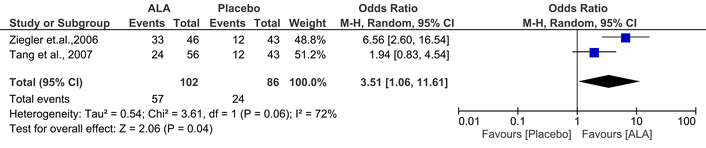

Global satisfaction was considered an important parameter for assessing ALA’s therapeutic benefits. Two studies [26, 27] collected global satisfaction ratings from participants using a 3-point scale: insufficient, satisfactory, and good/very good. Our analysis focused on the percentage of ratings categorized as “good/very good” as reported in the sources. These percentages were used to determine the number of occurrences of “good/very good” ratings relative to the total number of subjects. Interestingly, the ALA treatment has shown significant improvement in global satisfaction rate when compared to placebo [Mantel-Haenszel (M-H): 3.51, (1.06 → 11.61) at 95% CI, p = 0.04, I2 = 72%] (Figure 12).

Effect of ALA on Global satisfaction ratings. ALA treatment significantly increased the proportion of participants rating their experience as “good/very good” compared to placebo (M-H: 3.51; 95% CI: 1.06 to 11.61; p = 0.04; I2 = 72%), reflecting enhanced perceived therapeutic benefit. ALA: alpha lipoic acid; M-H: Mantel-Haenszel; CI: confidence interval.

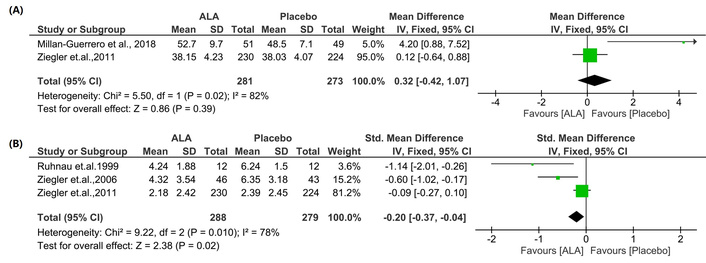

To enhance the robustness of our analysis, the MA was re-performed, excluding studies identified as having a high risk of bias. Specifically, the studies by Reljanovic et al. (1999) [12], Vijayakumar et al. (2014) [18], and Siddique et al. (2021) [28] were deemed to have a high risk of bias. Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the parameters MNCV and TSS to evaluate the influence of these high-risk studies on the study’s overall outcomes. However, sensitivity analysis cannot be performed for HbA1C because only four studies are available.

The sensitivity analysis revealed minor changes in effect magnitudes when comparing the MA results excluding vs. including high-risk studies for MNCV [IV: 0.32, (–0.42 → 1.07) at 95% CI, p = 0.39, I2 = 82% vs. IV: 0.26, (–0.44 → 0.96) at 95% CI, p = 0.47, I2 = 49%], and TSS [IV: –0.20, (–0.37 → –0.04) at 95% CI, p = 0.02, I2 = 78% vs. IV: –0.43, (–0.59 → –0.27) at 95% CI, p < 0.00001, I2 = 98%]. Therefore, the overall conclusions for the parameters HbA1C, MNCV, and TSS remain unchanged. Particularly for TSS, the sensitivity analysis revealed a reduced effect size for TSS when high-risk studies were excluded (IV: –0.20 vs. –0.43). While the p-value changed from p < 0.00001 to p = 0.02, the result remains statistically significant. Additionally, the heterogeneity was notably reduced from 98% to 78%, indicating improved consistency among the included studies. Sensitivity analyses were not conducted for the remaining parameters (NIS, NIS-LL, NSC number, NSC severity, NDS, VPT) because each of these parameters had only two high-quality studies (Figure 13).

Sensitivity analysis excluding high-risk bias studies for MNCV and TSS. (A): MNCV; (B): TSS. Results showed minor changes in effect sizes between analyses, excluding vs. including high-risk studies, MNCV (IV: 0.32 vs. 0.26), and TSS (IV: –0.20 vs. –0.43), remaining consistent in direction and significance, indicating robustness of the overall findings. Sensitivity analyses were not performed for other parameters due to either the limited number of available studies or the high quality of the included studies. MNCV: motor nerve conduction velocity; TSS: total severity score; ALA: alpha lipoic acid; IV: inverse variance; CI: confidence interval.

Five of the eight studies in this SR reported on safety outcomes. In Ziegler et al. (2011) [29], serious side effects were documented in both placebo (n = 63) and treatment (n = 88) groups; the treatment arm (n = 3) showed fewer deaths than the placebo (n = 6). Ziegler et al. (2006) [26] found that doses of ALA 1,200 mg (n = 5) and ALA 1,800 mg (n = 6) led to an increased incidence of nausea in a dose-dependent manner compared to the placebo group. Reljanovic et al. (1999) [12] reported no significant differences in treatment-related side effects or lab results between ALA and placebo/control, with overall tolerability rated as very good. In El-Nahas et al. (2020) [30], six participants in the treatment group experienced minor nausea, suggesting that ALA at 600 mg taken orally two times daily for six months is a safe and efficacious regimen for diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN). Ruhnau et al. (1999) [31] found no adverse effects when ALA was administered at 600 mg three times daily for three weeks. Due to limited data, an MA of safety outcomes could not be conducted.

This article includes most studies focusing on diabetic polyneuropathy, a common complication in diabetics that can lead to foot ulcers and amputations [10]. While no definitive treatment exists to halt neuropathy progression, management options are available [5]. Literature shows significant improvements in various parameters with ALA administered at 1,200 mg or 600 mg daily over 6 months to 4 years. ALA is noted for its antioxidant properties and its ability to boost levels of reduced glutathione, thereby potentially delaying or reversing peripheral DN symptoms. Previous clinical trials have demonstrated that ALA improves neuropathic deficit symptoms [32, 33].

Further, Hsieh et al. (2023) [9] endeavored to conduct a comprehensive analysis and draw conclusions regarding the favourable function of ALA in managing DN. Though the published MA by Hsieh et al. (2023) [9] is noted to have several methodological flaws, as highlighted in the introduction section. This provides an opportunity for a robust and comprehensive SR and MA.

This SR/MA aims to assess the effectiveness of oral ALA in treating DN through available RCTs [5], while also evaluating its efficacy and safety profile.

This study used parameters like HbA1C, NIS, NIS-LL, MNCV, NSC number and severity, TSS, NDS, VPT, and global satisfaction to highlight the benefits of ALA in managing DN.

The HbA1C that assesses glucose control over the past 90 days and serves as a diagnostic tool for diabetes [19] and neuropathy severity. HbA1C > 6.5% markedly heightens the risk and offers a quantitative measure of neuropathy severity in diabetic individuals [34]. Furthermore, a 1% increase in HbA1C is correlated with a roughly 10–15% elevation in the occurrence of DN [1]. In a previous multivariate analysis study, a significant association was discovered between elevated 3-year mean HbA1C levels and the presence of DPN in patients [35]. Studies have shown that ALA aids in reducing HbA1C levels by increasing the GLUT-4 transportation to muscle and fat, suppressing gluconeogenesis, and enhancing specific proteins within the insulin signaling pathway. Thus, ALA was classified as an insulin-mimetic agent. Hence, oral ALA supplementation has improved overall DN [36]. In this MA, ALA has significantly alleviated the elevated HbA1C levels compared to placebo/control.

Further, NIS is used to evaluate the neuropathy progression through 37 bilateral assessments covering cranial nerves, muscle weakness, reflexes, and sensation loss. Ratings range from 0 to 4 for muscle weakness and cranial nerves (0 being normal and 4 indicating paralysis) and 0 to 2 for reflexes or sensation (0 for normal and 2 for absence). The total score ranging from 0 to 244 for both sides of the body indicates the degree of neuropathic impairment; the higher scores imply higher significant impairment [10, 20]. This SR and MA revealed that ALA is favorable in ameliorating the NIS compared to placebo.

The NIS-LL is specifically designed to evaluate lower limb neuropathy with parameters such as weakness of muscle, reflexes, and sensation. A high NIS-LL score signifies greater impairment [20]. This MA found that ALA ameliorated the NIS-LL compared to placebo/control. This MA observed a numerical improvement in NIS-LL scores among ALA-treated patients compared to placebo; however, the difference did not reach statistical significance, indicating that ALA may have a limited impact on lower limb neuropathic impairment.

The MNCV is a test that assesses the flow of electrical signals via the nerves. The treated group didn’t show any significant changes in this parameter, which indicates nerve damage. A slower and weaker signal indicates nerve damage. The ALA-treated group showed no substantial changes in this parameter [20, 37]. The MA concluded that ALA is not helpful in improving the MNCV compared to placebo/control.

The NSC number and severity are used to rate muscle weakness, nerve sensitivity, and autonomic symptoms. These are subject-based assessments carried out using a standard questionnaire. A higher score indicates more neuronal injury and pain [22]. This MA revealed that ALA has the capability to correct the NSC number and severity compared to placebo/control.

The TSS questionnaire asks patients to rate the intensity (absent, mild, moderate, severe) and frequency (occasional, often, continuous) of four symptoms: pain, burning, paresthesia, and numbness. The score ranges from 0, indicating no symptoms, to 14.64, signifying severe and nearly constant presence of all four symptoms [38]. This MA exposed that ALA has a beneficial role in improving the TSS when compared to placebo/control.

The NDS encompasses assessments of vibration sensation, temperature sensation, pinprick, and ankle reflex on both sides of the great toes, with a highest score of 10 [39]. Neuropathy severity is classified into three categories: mild (scores 3–5), moderate (scores 6–8), and severe (scores 9–10) [24]. This MA revealed that ALA could significantly improve the NDS when compared to placebo/control.

The VPT is a testing tool used to screen for DN, despite being somewhat painful. It assesses the function of large myelinated nerve fibers, which often exhibit poor vibration sensation in DN patients. Higher VPT values indicate DN symptoms [25]. Testing is usually performed on the tips of the great toes using a neurothesiometer or a 128-Hz tuning fork [11]. Responses are categorized as abnormal (no vibration perception), present (vibration perceived within 10 seconds after the patient reports loss of perception), or reduced (vibration perceived after more than 10 seconds) [9]. VPT is crucial for early DN detection, helping to mitigate related complications. VPT values are classified as severe (> 25 V), moderate (20–25 V), and mild (15–20 V) [40]. This study demonstrated that ALA significantly improved NSC and VPT compared to placebo.

Global satisfaction scores in DN trials often involve asking participants to rate their satisfaction with treatment using a scale that ranges from “insufficient” or “poor” to “satisfactory” and “good” or “very good”. This assessment provides insights into how well the treatment alleviates symptoms, improves the quality of life, and meets patients’ expectations [5, 26, 27, 29]. Researchers analyze these scores to understand the broader impact of the treatment beyond specific clinical measures. They help gauge patient-reported outcomes and satisfaction levels, crucial for evaluating the effectiveness and acceptance of therapeutic interventions in managing DN [27, 29]. This MA shows that ALA has significantly improved global patient satisfaction compared to placebo/control.

Our analysis indicates a dose-dependent trend in both efficacy and tolerability outcomes. Trials utilizing higher ALA doses (1,200–1,800 mg/day) demonstrated more pronounced improvements in neuropathic symptom scores such as TSS, NIS, and NSC compared to lower doses (600 mg/day). However, higher doses were also associated with increased gastrointestinal side effects, particularly nausea, as reported in Ziegler et al. (2006) [26]. These findings suggest that while the therapeutic benefits of ALA increase with dose, 600–1,200 mg/day represents an optimal balance between efficacy and tolerability for most patients. Future studies should further clarify the dose-response relationship and long-term safety implications of high-dose ALA therapy.

In conclusion, based on the available moderate-high-quality evidence, the outcomes of this MA state that ALA is beneficial in improving HbA1C, NIS, NSC, TSS, NDS, VPT, and global satisfaction. However, ALA has not shown a significant effect on NIS-LL and MNCV when compared to the placebo/control. Hence, ALA can be a promising adjuvant in managing DN. Improvements in HbA1C, TSS, and NDS were supported by high-quality GRADE evidence, whereas outcomes such as global satisfaction and NSC severity were rated as moderate in quality. Thus, while ALA demonstrates consistent benefits in glycemic control and symptom reduction, conclusions regarding patient-reported and exploratory measures should be interpreted with greater caution until confirmed by further trials.

ALA’s possible synergistic effects when combined with other DN treatments have attracted a lot of attention. According to the literature currently in publication, ALA may improve treatment effectiveness when combined with other therapeutic drugs by taking advantage of their complementary modes of action. Vitamin B12 and ALA together reduce oxidative stress and improve nerve myelination, making them a strong therapeutic option for DN, according to an SR and MA on their combined use in diabetes mellitus (DM) and DN. Similar to this, the MAINTAIN study showed that patients with type 2 diabetes-associated peripheral neuropathy benefit greatly from the addition of methylcobalamin (a type of vitamin B12) and ALA to pregabalin in terms of pain management and nerve function, as indicated by increased nerve conduction velocity [41, 42].

A 12-month study on the combination of superoxide dismutase, ALA, vitamin B12, and carnitine reported significant improvements in various peripheral neuropathy indices, including pain, quality of life, sensory nerve action potential (SNAP), and sensory nerve conduction velocity (SNCV). However, some measures, like CARTs and MNSIE, did not show improvement [43].

The combination of ALA with epalrestat, an aldose reductase inhibitor, has also been explored. This combination was found to increase motor and SNCVs and improve neuropathic symptom scores more effectively than epalrestat monotherapy. The MA of 20 RCTs confirmed the superiority of ALA plus epalrestat combination therapy over monotherapies in clinical efficacy and nerve conduction velocities [44, 45].

Methylcobalamin plus ALA for 2–4 weeks produced superior results in NCV and neuropathic symptoms than methylcobalamin alone, according to another MA. A promising treatment approach was also suggested by a study on the effects of baicalin capsules combined with ALA, which found that patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy experienced significant improvements in nerve conduction velocity, oxidative stress, and inflammatory injury without an increase in adverse reactions [46, 47].

However, not all combination therapies show added benefits. The PAIN-CARE trial indicated that while pregabalin alone was superior to ALA in treating neuropathic pain, there was no added benefit of combining ALA with pregabalin for this purpose [48].

In summary, while there is compelling evidence supporting the synergistic effects of ALA with other treatments in improving clinical outcomes for DN, further research is needed to optimize these combinations and understand their mechanisms fully. Future studies should focus on long-term effects, potential adverse reactions, and the comparative efficacy of different combination therapies to establish comprehensive treatment protocols.

The study’s focus on English-language publications may have excluded important data from non-English sources. Moreover, the inclusion of only RCTs led to some studies being of lower quality due to a lack of blinding and insufficient outcome data. The limited number of studies and varying parameters caused inconsistent assessments. Factors such as HbA1C, NSC severity, TSS, NDS, and VPT exhibited significant heterogeneity, indicating varied results. While study designs were consistent, there were differences in sample sizes and age groups. The primary source of heterogeneity appeared to be the variability in ALA dosage (ranging from 600 to 1,800 mg/day) and treatment duration (from 3 weeks to 4 years). Moreover, the analysis was restricted by excluding studies that combined ALA with other treatments. Thus, further well-designed, randomized, placebo-controlled trials are needed to assess the long-term effects of oral ALA on DN and improve data reliability.

The potential of ALA as a cost-effective treatment for nerve issues in diabetics has generated interest and hope. Our study aimed to thoroughly evaluate the safety and effectiveness of oral ALA for DN. The results supported ALA’s use in this context; however, the lack of documented side effects in the selected studies limited our ability to conduct a definitive quantitative safety analysis, despite a systematic evaluation of safety criteria. Nine RCTs were included based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. This review demonstrated ALA’s effectiveness in improving neuropathic impairment, although improvements in MNCV and NIS-LL were not conclusive. Notably, we found a relationship between ALA’s effects, duration, and dosage, with significant benefits seen at higher short-term doses or shorter extended regimens. Our findings enhance understanding of ALA’s potential in treating DN and underscore the importance of balanced administration. To validate these results further, larger, long-term clinical trials are needed to explore the synergistic effects of ALA with other treatments, determine optimal dosages and durations, and investigate its mechanisms of action for more targeted therapies.

The findings of this MA suggest that oral ALA can significantly improve parameters such as HbA1C, NIS, NSC, TSS, NDS, global satisfaction, and VPT. No significant effects were noted on MNCV or NIS-LL, reflecting ALA’s limitations in reversing structural nerve damage. Improvements in individuals with DN occur with higher doses, such as 1,800 mg/day for at least three weeks, or lower doses (600–1,200 mg/day) over extended periods ranging from three weeks to four years. Our SR indicates that a daily dose of 600 mg for up to 24 months is considered safe, as no adverse effects were reported at this level. However, specific side effects were noted when ALA was administered at doses between 1,200 and 1,800 mg/day for five weeks or longer. Overall, ALA appears to be a promising adjuvant therapy for DN, but larger and more standardized trials are needed to confirm its long-term efficacy, optimal dosing, and safety profile [A preprint of this manuscript has previously been published in Research Square for peer review and feedback from the research community (https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3897905/v1)].

ALA: alpha lipoic acid

DN: diabetic neuropathy

HbA1C: glycated hemoglobin

IV: inverse variance

MA: meta-analysis

MNCV: motor nerve conduction velocity

NDS: neurological disability score

NIS: neuropathy impairment score

NIS-LL: neuropathy impairment score-low limb

NSC: neuropathy symptoms and change

RCTs: randomized controlled trials

SNCV: sensory nerve conduction velocity

SR: systematic review

TSS: total severity score

VPT: vibration perception threshold

SD: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. GLV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. KN: Supervision; Writing—review & editing. AK: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. SH: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. All authors have read and approved the submitted version.

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 8279

Download: 55

Times Cited: 0

Leonel Pereira, Ana Valado

Sharon Smith ... David Heal

Prerna Sarup ... Sonia Pahuja

Ekaterina P. Krutskikh ... Artem P. Gureev

Sneha Bagle ... Sadhana Sathaye

Luis Antonio Ramirez-Contreras ... Andrés Frausto de Alba

Agustina Lulustyaningati Nurul Aminin ... Muhammad Ajmal Shah