Affiliation:

1Independent Researcher, 2-41-2 Fujigaoka, Aoba ward, Yokohama City, Kanagawa 227-0043, Japan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3286-0307

Affiliation:

2Earth-Life Science Institute, Institute of Science Tokyo, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan

Email: m.hasan@elsi.jp; hasan.mahmudbio@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3332-1823

Explor Neurosci. 2025;4:1006118 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/en.2025.1006118

Received: July 20, 2025 Accepted: November 14, 2025 Published: December 01, 2025

Academic Editor: Dirk M. Hermann, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany; Chen Wang, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany

Neurological disorders constitute a major global health burden with limited effective treatments. Despite advances in molecular neuroscience, critical gaps persist in understanding intercellular communication systems underlying central nervous system homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Extracellular vesicles (EVs), nanoscale to microscale membrane-bound vesicles secreted by virtually all cell types, have emerged as pivotal mediators of intercellular communication in neurological pathologies. This review examines molecular mechanisms governing EV biogenesis, cargo selection, and pathological functions in neurological disorders, emphasizing the emerging role of ubiquitin-like protein 3 (UBL3) as a novel regulator of EV-mediated protein sorting. Neural cell populations produce specialized EV subtypes containing distinct molecular cargo reflecting their physiological states. UBL3, a membrane-anchored post-translational modifier, operates through geranylgeranylation-dependent mechanisms to promote selective protein incorporation into small EVs (sEVs), with knockout studies demonstrating approximately 60% reduction in EV protein content. Proteomic analyses reveal UBL3 interacts with over 1,200 proteins, with ~30% classified as EV cargo proteins. Critically, UBL3-mediated sorting influences disease-associated protein trafficking, including α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease and mutant huntingtin in Huntington’s disease, suggesting involvement in prion-like spreading mechanisms. EVs’ dual nature as pathological mediators and therapeutic vehicles represents a paradigm shift in neurological medicine. EVs offer advantages as natural drug delivery systems capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier, accessible biomarkers for noninvasive disease monitoring via liquid biopsies (achieving diagnostic accuracies exceeding 0.88 ROC-AUC), and engineered therapeutic platforms for delivering CRISPR-Cas9 systems and neuroprotective factors. However, clinical translation requires addressing challenges, including standardizing isolation protocols, elucidating cell-type-specific cargo sorting mechanisms, and defining optimal administration routes. Understanding UBL3-mediated cargo sorting mechanisms presents promising therapeutic opportunities by selectively modulating pathogenic protein trafficking. EVs, positioned at the intersection of pathogenesis and therapy, represent attractive targets for precision medicine approaches in neurological conditions, with UBL3 emerging as a novel molecular handle for manipulating EV composition and function.

Neurological disorders represent one of the most significant public health challenges globally, affecting hundreds of millions of individuals across all age groups [1, 2]. Conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS), epilepsy, and stroke are characterized by progressive functional deterioration, high morbidity, and often a lack of curative treatment [3, 4]. Despite ongoing advances in molecular neuroscience and neuroimmunology, a critical gap remains in our understanding of the dynamic intercellular communication systems that underlie both the maintenance of central nervous system (CNS) homeostasis and the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration [5, 6]. The complexity of CNS signaling is amplified by diverse cellular constituents, including neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, and endothelial cells, which must be coordinated in a highly synchronized and spatially regulated environment. Impaired intercellular communication drives disease pathogenesis, highlighting the importance of understanding alternative signaling mechanisms [7, 8].

In recent years, there has been a paradigm shift in our understanding of how cells communicate in the CNS, with increasing recognition of extracellular vesicles (EVs) as pivotal mediators of this process [9, 10]. EVs are nano-to microscale membrane-bound structures released by nearly all cell types. EV-mediated communication, previously underappreciated compared to synaptic transmission and soluble factor signaling, now attracts significant attention due to its capacity for complex molecular messaging, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, across long distances and even across biological barriers such as the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [11]. In the neural context, EVs serve as shuttles for regulatory RNA molecules, neurotransmitter-modulating proteins, and inflammatory signals, making them indispensable for both normal physiology and the propagation of disease signals [12].

EVs are classified into exosomes and microvesicles based on their size and biogenesis. Exosomes (30–150 nm) originate from the endosomal system and are secreted via the fusion of multivesicular bodies with the plasma membrane, whereas microvesicles (100–1,000 nm) bud directly from the cell membrane [13, 14]. These vesicle subtypes transport distinct, cell-specific cargo that reflects their cellular origin and physiological state. They regulate critical processes, including synaptic plasticity, myelination, immune surveillance, and tissue repair [15, 16].

EVs represent actively regulated cellular products rather than passive byproducts. Cells employ sophisticated machinery to control EV formation and cargo selection. Specific intracellular mechanisms govern EV molecular composition by selectively packaging signaling molecules into vesicles [17, 18]. Among these regulatory mechanisms, post-translational modifications (PTMs) have emerged as critical modulators of EV cargo selection. In particular, ubiquitin-like protein 3 (UBL3), a membrane-anchored PTM enzyme, has recently garnered attention for its role in promoting the incorporation of proteins into small EVs (sEVs). UBL3 is preferentially modified with geranylgeranyl moieties, facilitating membrane anchoring and cargo affinity [19]. While its functions are still being elucidated, early evidence suggests that UBL3 is a key player in shaping the immunological and signaling profiles of EVs, with potential implications in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative disease pathways [20, 21].

The relevance of EVs to neurological disorders has become increasingly evident. Pathogenic proteins, such as amyloid-β (Aβ), tau, α-synuclein, and TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), have been detected in EVs, implicating them in the intercellular spread of protein aggregates in AD, PD, and ALS [22–24]. EVs also play a role in modulating the immune environment in MS and compromising the integrity of the BBB in stroke [25, 26]. These findings establish mechanistic connections between EV biology and neurological disease while highlighting their potential as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic tools. Their presence in biofluids, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood, and saliva, makes them accessible for noninvasive monitoring. In contrast, their ability to cross the BBB opens exciting avenues for targeted drug delivery to the CNS [27, 28].

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain in EV research, including the heterogeneity of vesicle populations, the need for standardization of isolation protocols, and the requirement for cell-type-specific in vivo models [29, 30]. Moreover, while UBL3 and other PTMs offer intriguing molecular handles for manipulating EV cargo, their physiological relevance and druggability in neural contexts remain to be explored. Understanding the functional roles of EV-associated PTMs, particularly in the context of CNS-specific signaling and disease modulation, is crucial for translating basic EV research into clinical applications [31–33].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the emerging roles of EVs in neurological disorders, with special emphasis on the molecular mechanisms underlying EV biogenesis, cargo sorting, and function. Particular focus is given to the regulatory role of UBL3 and its potential as a modulator of EV composition in neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory diseases. By integrating insights from EV biology, neuroscience, and translational medicine, this study outlines the current landscape and future directions for leveraging EVs as diagnostic and therapeutic tools in neurology.

EVs in the CNS are released by diverse neural cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes, each contributing unique molecular cargoes that reflect their physiological or pathological states [34]. Neurons produce EVs from both the soma and dendrites, which regulate synaptic plasticity and neuronal support. For example, neuronal EVs contain microRNAs (miRNAs) (such as miR-98) that regulate microglial phagocytosis after ischemic injuries [35, 36]. Oligodendrocyte-derived EVs supply axonal support under stress by delivering enzymes such as catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [37, 38]. Astrocyte-derived EVs carry apolipoprotein D and neurotransmitter transporters that influence neuronal survival [39], and microglia-derived EVs contain proteins such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and lipid mediators such as endocannabinoids that modulate synaptic activity and inflammatory signaling [40, 41].

Cell-specific regulatory mechanisms control the secretion of EVs from these cells. In microglia, ATP stimulation via P2X7 receptors triggers ectosome shedding, whereas serotonin and Wnt-3a signaling enhance exosome release through alterations in calcium flux and endosomal pathways [42]. Neurons rely on endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent and ceramide-mediated pathways for EV biogenesis in response to synaptic activity or stress [43]. Oligodendrocytic EV release is enhanced by neuronal-glial interactions, suggesting bidirectional regulation [44]. Neuroanatomical studies have revealed cell-type-specific expression patterns of UBL3 and related ubiquitin-like proteins in brain regions affected by neurodegenerative diseases [45, 46].

EV populations are enriched in lipids, RNAs, and proteins that mediate intercellular communication. Lipidomic studies have shown that EVs from oligodendrocytes and microglia are enriched in ceramides, sphingomyelins, cholesterol, and glycolipids, which are molecules critical for membrane dynamics and signaling [47]. RNA cargoes include miRNAs that regulate inflammation (e.g., miR‑98 and miR‑146a), lncRNAs, and mRNAs that reflect the transcriptional state of the parent cell and can alter gene expression in recipient cells [48–50]. Proteomic analyses have revealed the presence of ESCRT proteins, tetraspanins (transmembrane proteins including CD9, CD63, and CD81 that organize membrane microdomains), heat shock proteins, metabolic enzymes, and cell-specific markers, including apolipoprotein D, GAPDH, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules [51, 52].

Several molecular mechanisms govern the specificity of EV cargo sorting. ESCRT-dependent ubiquitination pathways enable the selective packaging of proteins into exosomes by recognizing ubiquitinated membrane proteins through the recruitment of ESCRT-0 and ALIX [53, 54]. Additionally, ESCRT-independent mechanisms involving lipid rafts, ceramide, and tetraspanins play a crucial role in EV formation in neural cells [55].

PTMs of cargo proteins play a pivotal role in determining their incorporation into EVs. Beyond ubiquitination, SUMOylation and lipidation influence cargo sorting; for instance, SUMOylated heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (hnRNPA2B1) binds specific miRNAs for exosomal inclusion, while palmitoylation governs exosomal protein-membrane interactions [56–58]. Most recently, UBL3 has been identified as a key regulator of EV protein sorting. UBL3 modifies proteins via S-palmitoylation-like PTMs to promote their targeting into sEVs. UBL3 knock-out cells exhibit a ~60% reduction in EV protein content, and UBL3-mediated sorting of signaling molecules, such as Ras, to EVs has been demonstrated [13, 20, 59]. While initially identified in non-neuronal systems, the role of UBL3 in neural EV biology is likely substantial but remains underexplored.

EV uptake by recipient cells occurs through multiple mechanisms, including membrane fusion, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolin-dependent uptake, and macropinocytosis, with the specific pathway influenced by EV surface molecules and cell type [60, 61]. In neural cells, tetraspanins and heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate receptor-dependent internalization, while microglia preferentially use phagocytosis compared to neurons and astrocytes [62–64].

Collectively, CNS-derived EVs exhibit highly specialized intercellular communication functions, reflecting precise cellular states shaped by regulated release mechanisms, enriched molecular cargo, and PTM-driven sorting machinery such as UBL3. Understanding these systems is critical for leveraging EVs in therapeutic and diagnostic applications in neurobiology. The diverse cellular origins of EVs in the CNS result in heterogeneous vesicle populations with distinct molecular signatures and functional properties. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of how neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes each contribute unique EV subtypes that collectively orchestrate complex intercellular communication networks essential for brain function.

Cell-type-specific EV characteristics and functions in the CNS.

| Cell type | EV size range | Key cargo components | Primary functions | Key citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurons | 30–1,000 nm | miR-98, neurotransmitter-modulating proteins, synaptic plasticity regulators | Synaptic plasticity regulation, microglial phagocytosis modulation, neuronal support signaling | [35, 36] |

| Astrocytes | 30–1,000 nm | Apolipoprotein D, neurotransmitter transporters, and inflammatory mediators | Neuronal survival support, oxidative stress protection, and BBB integrity modulation | [39] |

| Microglia | 30–1,000 nm | GAPDH, endocannabinoids, pro-inflammatory cytokines, lipid mediators | Synaptic activity modulation, inflammatory signaling, and immune surveillance | [40, 41] |

| Oligodendrocytes | 30–1,000 nm | Catalase, superoxide dismutase, myelin proteins, metabolic enzymes | Axonal support under stress, myelination regulation, metabolic support | [37, 38] |

This table summarizes the cell-type-specific characteristics and functions of EVs produced by different CNS cell types, highlighting their diverse roles in neural communication and homeostasis. BBB: blood-brain barrier; CNS: central nervous system; EV: extracellular vesicle; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

UBL3 has emerged as a key regulator of sEV cargo sorting via PTM mechanisms. UBL3 is a membrane-anchored ubiquitinfold protein that binds to protein substrates via its C-terminal CAAX prenylation motif, facilitating targeted inclusion into sEVs [20, 33, 59]. Once attached to endosomal or plasma membranes, UBL3 promotes the packaging of select proteins into intraluminal vesicles by enhancing membrane association and potentially recruiting ESCRT or lipid-sorting machinery [20, 59]. The comparative analysis of PTM in EV cargo selection is summarized in Table 2.

Comparative analysis of PTMs in EV cargo selection.

| PTM type | Key regulatory proteins | Molecular mechanism | Cargo selection specificity | Impact on EV content | Neurological relevance | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBL3 modification | UBL3 (membrane-anchored ubiquitin-fold protein) | Geranylgeranylation-dependent membrane anchoring promotes protein-membrane association via the C-terminal CAAX motif | Broad spectrum: > 1,200 interactors; ~30% are EV cargo proteins, including Ras, α-synuclein, mHTT | ~60% reduction in sEV protein content upon knockout | α-synuclein (PD), mHTT (HD); interaction upregulated under oxidative stress | [18, 20] |

| Ubiquitination | ESCRT-0, ALIX, TSG101, MARCH E3 ligases | Recognition of ubiquitinated membrane proteins; ESCRT complex recruitment for MVB sorting | Selective for ubiquitin-tagged transmembrane proteins; MHC-II molecules | Essential for ESCRT-dependent exosome formation | Immune molecule sorting; potential role in neuroinflammation | [53, 54] |

| SUMOylation | SUMO-2, SUMO-conjugating enzymes | Covalent attachment of SUMO moieties facilitates ESCRT interactions | hnRNPA2B1-mediated miRNA sorting via specific motifs; α-synuclein, APP sorting | Controls specific miRNA profiles (e.g., miR-146a) and protein aggregates | miRNA-mediated neuroinflammation; α-synuclein propagation (PD); APP processing (AD) | [58, 65] |

| Palmitoylation | Palmitoyl acyltransferases (PATs) | S-acylation with palmitate enhances hydrophobic membrane interactions | Membrane-associated proteins; tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81) | Governs protein-membrane dynamics and clustering in lipid rafts | Tetraspanin-mediated EV formation; potential role in synaptic vesicle release | [57, 58] |

| Glycosylation | Glycosyltransferases | N- or O-linked glycan addition to transmembrane proteins | Surface glycoproteins: EWI-2 and other tetraspanin partners | Determines EV targeting, uptake specificity, and immunological recognition | BBB targeting, microglial uptake specificity, neuroimmune interactions | [66] |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; APP: amyloid precursor protein; BBB: blood-brain barrier; ESCRT: endosomal sorting complex required for transport; EV: extracellular vesicle; HD: Huntington’s disease; hnRNPA2B1: heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1; MARCH: membrane-associated RING-CH; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; miRNA: microRNA; mHTT: mutant huntingtin; MVB: multivesicular body; PD: Parkinson’s disease; PTMs: post-translational modifications; sEV: small EV; UBL3: ubiquitin-like protein 3.

The foundational understanding of UBL3 (initially termed membrane-anchored ubiquitin-fold, MUB) emerged from pioneering work by Vierstra’s group. They first characterized MUB as a novel ubiquitin-fold protein with a C-terminal CAAX prenylation motif essential for membrane localization [19]. Subsequent studies revealed that MUB localizes to both the plasma membrane and endomembrane systems, where it modifies target proteins through a mechanism distinct from classical ubiquitination [67]. Importantly, they demonstrated that MUB/UBL3 functions as a post-translational modifier controlling protein trafficking and signaling, establishing its role as a regulatory hub for cellular protein sorting [68]. This work laid the foundation for understanding UBL3’s role in EV biogenesis, as comprehensively reviewed by Vierstra [69].

While previous reviews have examined ubiquitin-like proteins in EV biology broadly, the present review specifically focuses on UBL3’s emerging role in neurological disorders, integrating recent discoveries about its interaction with neurodegenerative disease proteins and potential as a therapeutic target in CNS pathologies [70].

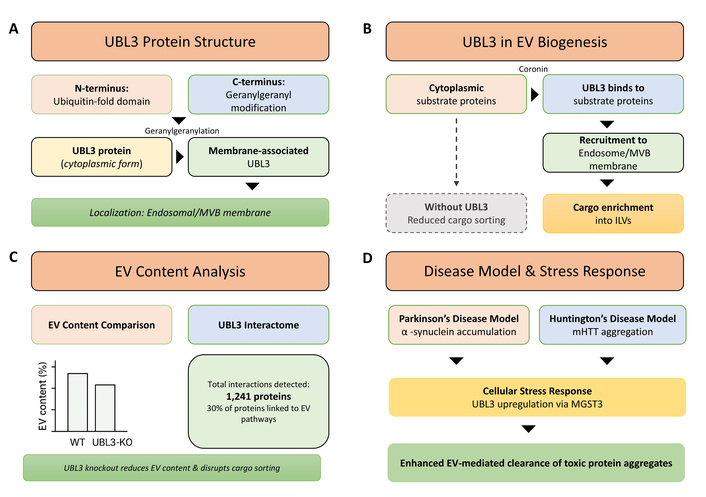

Proteomic analyses reveal that UBL3 interacts with more than 1,200 proteins, with approximately 30% classified as sEV cargo proteins. UBL3 knock-out cells exhibit roughly a 60% reduction in sEV protein content, underscoring its centrality in protein loading Figure 1 [20, 59]. Notably, UBL3-mediated sorting is essential for the incorporation of growth regulators, such as oncogenic Ras, which influences extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation in recipient cells, illustrating how UBL3 can shift intercellular signaling profiles [33, 59].

UBL3-mediated post-translational modification (PTM) regulates protein sorting into small extracellular vesicles (sEVs). (A) Domain structure of ubiquitin-like protein 3 (UBL3) showing the ubiquitin-fold domain and C-terminal geranylgeranylation signal sequence (CAAX motif). The geranylgeranyl modification enables UBL3 membrane anchoring to the multivesicular body (MVB) and endosomal membranes. (B) Schematic representation of UBL3-mediated substrate protein recruitment and cargo sorting. Cytoplasmic substrate proteins (exemplified by Coronin) are recognized and modified by UBL3, leading to recruitment to MVB membranes and subsequent enrichment into intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within MVBs. This UBL3-mediated modification directs cargo selection for packaging into sEVs. (C) Quantitative analysis of sEV protein content showing approximately 60% reduction in total protein levels from Ubl3-knockout (KO) mice compared to wild-type (WT) controls, demonstrating the critical role of UBL3 in protein loading into sEVs [59]. Proteomics analysis identified 1,241 UBL3-interacting proteins, with approximately 30% annotated as EV-associated proteins. (D) Disease relevance of UBL3-mediated sorting: α-synuclein (Parkinson’s disease model) and mutant huntingtin (mHTT; Huntington’s disease model) are sorted into sEVs via UBL3 modification, potentially facilitating intercellular propagation of neurotoxic protein pathology. UBL3 expression activates stress-inducible pathways, including MGST3-mediated upregulation, which may represent adaptive responses to neurodegeneration-associated proteotoxic stress.

In neural contexts, emerging evidence suggests that UBL3 is involved in the trafficking of proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases. UBL3 interacts with α-synuclein in cell models, and this interaction increases under oxidative stress via microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 [31]. UBL3 also colocalizes with mutant huntingtin (mHTT) fragments in neurons from Huntington’s disease patients, influencing their intracellular sorting [32]. Recent studies have further characterized UBL3’s role in neurodegenerative protein trafficking, demonstrating its involvement in cellular stress responses and protein quality control [71]. UBL3 expression patterns in neural tissues are dynamically regulated under pathological conditions, influencing both intracellular protein sorting and EV cargo composition [72]. While these studies focus on intracellular localization, they suggest UBL3 could direct pathogenic protein loading into sEVs, thus promoting pathological propagation across neural circuits.

Recent studies have expanded our understanding of UBL3’s roles in various pathological contexts. UBL3 has been identified as a critical mediator of inflammatory responses, with its expression significantly altered in inflammatory diseases [73]. In neural tissues, UBL3 shows distinct expression patterns during development and disease states, suggesting context-dependent functions [74]. Notably, UBL3 expression correlates with neuroinflammatory markers in neurodegenerative conditions [75]. In cancer pathology, UBL3 serves as a prognostic biomarker in certain malignancies [76, 77], while structural studies reveal UBL3’s unique membrane-targeting mechanisms that distinguish it from other ubiquitin-like modifiers [78]. These findings collectively highlight UBL3’s multifaceted roles beyond EV cargo sorting, encompassing inflammation, cancer progression, and neural development.

The brain-specific expression of UBL3 further supports a functional role in CNS EV biology. Proteomic analyses have identified additional UBL3-interacting proteins in neuronal models, expanding our understanding of its role in neurodegenerative disease pathways [79]. Transgenic mouse models overexpressing UBL3 in cortex and hippocampus identified 35 new UBL3 interactors, including RNA-binding proteins implicated in neurodegeneration [e.g., fused in sarcoma (FUS), hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1)] [75]. This raises the possibility that UBL3 participates in sEV-mediated RNA transfer, potentially influencing neural protein expression and homeostasis; however, in vivo functional data remain limited [80].

Beyond UBL3, other PTMs regulate EV cargo. SUMOylation of hnRNPA2B1 directs specific miRNAs into exosomes [58]. SUMO2 modifies α-synuclein and amyloid precursor protein (APP) to promote their sorting into EVs via interactions with ESCRT components [65]. Additionally, palmitoylation enhances the membrane targeting of cargo proteins, while ubiquitination by membrane-associated RING-CH (MARCH) E3 ligases controls the endosomal sorting of immune molecules, such as MHC-II, into EVs [81]. Glycosylation of transmembrane proteins can determine EV targeting and uptake, as shown for EWI2 [66]. These combined mechanisms suggest an intricate PTM network orchestrating EV content.

In the CNS, such PTM-regulated sorting can influence neuroinflammation, synaptic function, and neurodegeneration. UBL3-mediated inclusion of α-synuclein or mHTT into sEVs may exacerbate disease progression or modulate microglial activation. SUMOylated hnRNPA2B1 sorting of inflammatory miRNAs might enhance cytokine responses in astrocytes or microglia. Glycosylation of neuronal receptors in EVs could impact BBB integrity or neuroimmune crosstalk [56, 59, 82].

In vitro and in vivo functional studies demonstrate that EVs carrying pathogenic proteins induce aggregation and toxicity in recipient cells. In contrast, EVs loaded with regulatory RNAs modulate neuroinflammatory or synaptic gene expression [32, 83]. However, direct evidence linking UBL3-mediated sorting with disease phenotypes remains sparse. Future investigations may employ UBL3-knockdown or overexpressing models to examine effects on disease progression, such as α-synuclein accumulation in PD models or cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s models [84, 85].

In summary, UBL3 serves as a critical PTM-based gatekeeper for protein loading into sEVs, with emerging evidence pointing toward its involvement in neural disease pathways via cargo sorting of α-synuclein and mHTT. Coupled with other PTMs like SUMOylation, palmitoylation, ubiquitination, and glycosylation, these regulatory networks fine-tune EV composition and function. A deeper mechanistic understanding of UBL3 and these PTMs in neural EVs could illuminate new therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative diseases.

EVs serve as vehicles for the intercellular transfer of pathogenic factors within the brain, thereby facilitating the progression of major neurological disorders. AD, both tau and Aβ peptides are sequestered into EVs, which can propagate pathological aggregates to healthy neurons [86]. Tau-containing EVs isolated from postmortem AD brains have been shown to seed tau phosphorylation and neurofibrillary tangle formation in mouse models with as little as 300 pg of EV-associated tau [87]. Cryo-EM and proteomic studies further confirm that EVs specifically carry truncated tau filaments tethered to EV membranes, implicating active sorting mechanisms in EV-mediated propagation [88].

PD exhibits similar EV‑mediated propagation of α-synuclein. Neuron-derived EVs from PD patients contain oligomeric and phosphorylated forms of α-synuclein. These EVs elicit neuroinflammatory responses by activating microglia, amplifying disease progression [89, 90]. Conversely, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived EVs containing catalase exhibit neuroprotective properties in dopaminergic neurons. This demonstrates the dual nature of EVs as both pathological mediators and therapeutic agents in PD [91, 92].

In ALS, EVs mediate intercellular toxicity via TDP‑43 and mutant SOD1 cargo. Postmortem tissue and biofluid‑derived EVs from ALS patients contain full-length TDP‑43 and pathogenic C‑terminal fragments, which induce protein aggregation in recipient cells [93, 94]. The EV-mediated dispersal of TDP-43 correlates with disease severity in ALS and distinguishes patients at both pre- and peri-symptomatic stages [95].

Beyond neurodegeneration, EVs contribute to pathology in MS, stroke, and epilepsy through immune modulation and barrier dysfunction. In MS, EVs derived from activated microglia and immune cells carry pro-inflammatory cytokines, miRNAs, and matrix metalloproteinases that disrupt the BBB and promote demyelination [96, 97]. During a stroke, astrocyte-derived EVs deliver inflammatory miRNAs to endothelial cells, increasing tight junction permeability and exacerbating edema [98]. In epilepsy, alterations in blood-derived EV protein signatures suggest a role in seizure propagation through neurovascular unit disruption, but specific mechanisms remain to be clarified [99, 100].

Collectively, these studies indicate that EVs shuttle both toxic and inflammatory cargo across cell types and anatomical boundaries, thereby amplifying pathological cascades across the CNS. EVs enhance the seeding of misfolded proteins, promote neuroinflammation, and breach protective barriers, such as the BBB, thereby integrating multiple disease pathways. Targeting EV release or their uptake provides a promising therapeutic avenue. For instance, blockade of EV biogenesis via neutral sphingomyelinase inhibitors reduces tau spread in AD models, while reducing microglial EV release attenuates neuroinflammation in MS [101–103]. However, these approaches require fine-tuning to avoid disrupting homeostatic EV functions, which are essential for neural health. Table 3 summarizes EV involvement in neurological disorders across multiple disease categories, highlighting pathogenic mechanisms, therapeutic applications, and biomarker potential.

EVs in neurological disorders: pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic applications.

| Disease | Pathogenic EV cargo | Disease propagation mechanism | Therapeutic EV applications | Biomarker potential | Key citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | Aβ peptides, phosphorylated tau (pT181), and truncated tau filaments | Intercellular spread of protein aggregates, tau seeding, and neurofibrillary tangle formation | MSC-derived EVs for neuroprotection, miRNA delivery for cognitive enhancement | Plasma EV tau and Aβ42 correlate with CSF biomarkers and cognitive decline | [73–76, 95] |

| Parkinson’s disease | α-synuclein (oligomeric and phosphorylated forms), LRRK2, pT73-Rab10 | Prion-like spreading of α-synuclein, microglial activation, and neuroinflammation | Catalase-loaded EVs for dopaminergic neuroprotection, anti-inflammatory EV therapy | Urinary EV proteomic profiles achieve 76–86% diagnostic accuracy | [89, 92, 104] |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | TDP-43 (full-length and C-terminal fragments), mutant SOD1 | Intercellular toxicity transfer, protein aggregation induction, and motor neuron degeneration | Engineered EVs for neuroprotective factor delivery, RNA therapeutics | EV-mediated TDP-43 correlates with disease severity and progression | [93–95] |

| Multiple sclerosis | Pro-inflammatory cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases, and inflammatory miRNAs | BBB disruption, demyelination promotion, and immune cell activation | Immunomodulatory EVs, remyelination-promoting factors | CSF-derived EVs show unique protein enrichment profiles for disease monitoring | [96, 97, 105] |

| Stroke | Inflammatory miRNAs, tight junction disruptors, pro-inflammatory mediators | BBB permeability increase, endothelial dysfunction, and edema exacerbation | miR-124 and miR-181b delivery for neurogenesis and angiogenesis, neuroprotective EVs | Brain-derived EVs reflect acute injury status and recovery potential | [106, 107] |

Aβ: amyloid-β; BBB: blood-brain barrier; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; EVs: extracellular vesicles; LRRK2: leucine-rich repeat kinase 2; miRNAs: microRNAs; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; SOD1: superoxide dismutase 1; TDP-43: TAR DNA-binding protein 43.

These findings establish EVs as critical contributors to neurological disease progression while revealing opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Table 3 consolidates current evidence demonstrating how EVs facilitate disease progression through the intercellular transfer of pathogenic cargo while simultaneously offering promising avenues for biomarker development and therapeutic applications across diverse neurological conditions.

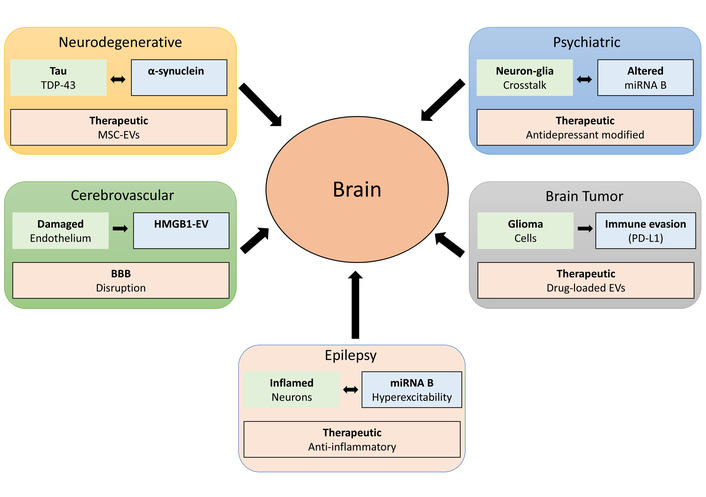

Depression and other psychiatric disorders involve significant EV-mediated pathophysiology. In major depressive disorder, circulating EVs carry altered miRNA profiles, particularly miR-139-5p and miR-425-3p, which correlate with symptom severity and treatment response [108, 109]. EV-derived brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels are significantly reduced in depression patients, serving as both a biomarker and a potential therapeutic target [110]. Stress-induced changes in neuronal EV secretion alter hippocampal neuroplasticity through miR-124-3p and miR-9-5p transfer, contributing to depression pathogenesis [111]. Antidepressant treatment modifies EV cargo composition, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors increasing neuroprotective miRNAs in patient-derived EVs [112]. EV-mediated mechanisms across neurological disorder categories are shown in Figure 2.

EV-mediated mechanisms across neurological disorder categories. Schematic illustration of disease-specific EV cargo, pathological outcomes, and therapeutic EV interventions for five major neurological disorder categories (left to right, top to bottom). The neurodegenerative panel shows tau and TDP-43 as disease-specific cargos leading to protein aggregation in recipient neurons, with therapeutic MSC-EVs providing neuroprotection. The psychiatric panel depicts neuron-glia crosstalk and dysregulated miRNA B as pathological outcomes, with therapeutic antidepressant-modified EVs as intervention. The cerebrovascular panel illustrates damaged endothelium releasing HMGB1-EVs, BBB disruption, and endothelial dysfunction. The epilepsy panel shows inflamed neurons and miRNA B-mediated hyperexcitability propagation, with therapeutic anti-inflammatory EVs. The brain tumors panel demonstrates glioma cells expressing PD-L1 for immune evasion, with therapeutic drug-loaded EVs as a treatment strategy. The central brain represents the target organ for EV transfer and signaling. Black arrows indicate EV transfer direction from peripheral sites to the brain. BBB: blood-brain barrier; EVs: extracellular vesicles; HMGB1: high mobility group box 1; miRNA: microRNA; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; PD-L1: programmed death ligand-1; TDP-43: TAR DNA-binding protein 43.

In ischemic stroke, EVs play dual roles in injury propagation and recovery. Acute phase EVs from damaged neurons contain danger-associated molecular patterns that exacerbate inflammation [113]. However, endogenous repair mechanisms involve protective EVs carrying miR-124 and miR-126, which promote angiogenesis and neurogenesis [114]. Remote ischemic preconditioning induces the release of cardioprotective EVs that reduce infarct size through miR-144 and miR-21 delivery [115]. Post-stroke recovery is enhanced by circulating EVs containing growth factors and anti-inflammatory miRNAs [116].

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) involves distinct EV-mediated pathways. EVs from hemorrhagic CSF carry hemoglobin degradation products that trigger vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia [117]. Microglia-derived EVs in SAH contain elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases, contributing to BBB breakdown [118].

Epilepsy involves significant alterations in EV composition and function. Status epilepticus triggers the release of neuronal EVs enriched in inflammatory miRNAs (miR-155, miR-146a) that perpetuate neuroinflammation [119]. Hippocampal EVs from epileptic patients contain elevated levels of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein, contributing to seizure susceptibility [120]. Anti-epileptic drug resistance correlates with specific EV-miRNA signatures, notably reduced miR-194-2-3p and elevated miR-301a-3p [121].

Glioblastoma and other brain tumors extensively utilize EVs for tumor progression and immune evasion. Glioma-derived EVs carry oncogenic proteins and miRNAs (miR-21, miR-10b) that promote tumor growth and invasion [122, 123]. These EVs cross the BBB, making them detectable in peripheral blood for liquid biopsy applications [124]. Tumor EVs reprogram the microenvironment through transfer of immunosuppressive molecules, including PD-L1 and TGF-β [125, 126]. EV-mediated transfer of drug resistance factors, including O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, contributes to chemotherapy resistance [127, 128]. Brain metastases from systemic cancers release EVs that breach the BBB and create pre-metastatic niches [129–131]. The EV-mediated mechanisms across neurological disorder categories are shown in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 4.

EV-mediated mechanisms across neurological disorder categories.

| Disease category | Key EV cargo | Pathological mechanisms | Therapeutic applications | miRNA biomarkers | Key citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative | Aβ, tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43 | Protein propagation, neuroinflammation | MSC-EVs, miRNA delivery | miR-132, miR-212 | [86–88] |

| Psychiatric | BDNF, inflammatory cytokines | Neuroplasticity disruption, HPA axis dysregulation | Antidepressant-modified EVs | miR-139-5p, miR-425-3p, miR-124-3p | [108–110] |

| Cerebrovascular | DAMPs, growth factors, hemoglobin products | BBB disruption, vasospasm, angiogenesis | Remote conditioning EVs, NPCs-EVs | miR-124, miR-126, miR-21, miR-210 | [113, 117, 132, 133] |

| Epilepsy | HMGB1, inflammatory mediators | Neuroinflammation, excitotoxicity, seizure perpetuation | Anti-inflammatory EVs | miR-155, miR-146a, miR-134-3p | [119–121] |

| Brain tumors | Oncogenic proteins, PD-L1, TGF-β, MGMT | Tumor growth, immune evasion, chemoresistance | Drug-loaded EVs, liquid biopsy | miR-21, miR-10b | [122–126] |

Aβ: amyloid-β; BBB: blood-brain barrier; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; EVs: extracellular vesicles; HMGB1: high mobility group box 1; miRNA: microRNA; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; PD-L1: programmed death ligand-1; TDP-43: TAR DNA-binding protein 43.

EVs have emerged as revolutionary biomarkers for neurological disorders, offering unprecedented insights into CNS pathophysiology through minimally invasive liquid biopsies [28]. EVs found in CSF, blood, and saliva reflect the pathophysiological state of their parent cells, enabling liquid biopsies (minimally invasive sampling of biofluids rather than tissue) that provide a window into brain pathology [106]. Isolation of brain-derived EVs from peripheral blood enables noninvasive access to CNS biomarkers, facilitating early diagnosis and disease monitoring [134].

In AD, elevated levels of Aβ42, phosphorylated tau at position 181, and specific miRNAs in plasma EVs correlate with CSF biomarkers and cognitive decline [135]. Meta-analyses demonstrate that biomarkers derived from general EVs show superior diagnostic accuracy compared to CNS-enriched EVs, with less variance and publication bias [135]. For PD, elevated levels of phosphorylated leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) and pT73-Rab10 in EVs correlate with cognitive impairment and disease progression, while proteomic analysis of urinary EVs has achieved diagnostic accuracy rates of 76–86% [104].

MS research has revealed unique protein profiles in CSF-derived EVs, with 50 proteins significantly enriched compared to non-purified CSF [105]. Brain-derived blood EVs that cross the BBB reflect the current immune status of the CNS, offering potential biomarkers for disease activity monitoring [105]. The noninvasive nature of EV-based biomarkers represents a significant advancement over traditional CSF analysis and neuroimaging approaches [136, 137].

The therapeutic potential of engineered EVs as drug delivery vehicles has garnered considerable attention due to their natural biocompatibility and ability to cross the BBB [138]. EVs can be engineered for specific marker expression or therapeutic cargo transport, including small interfering RNA (siRNA), proteins, and drugs [139]. Engineering EVs to target more specifically by modifying their surfaces with ligands that bind to brain cell receptors represents a major advancement [140].

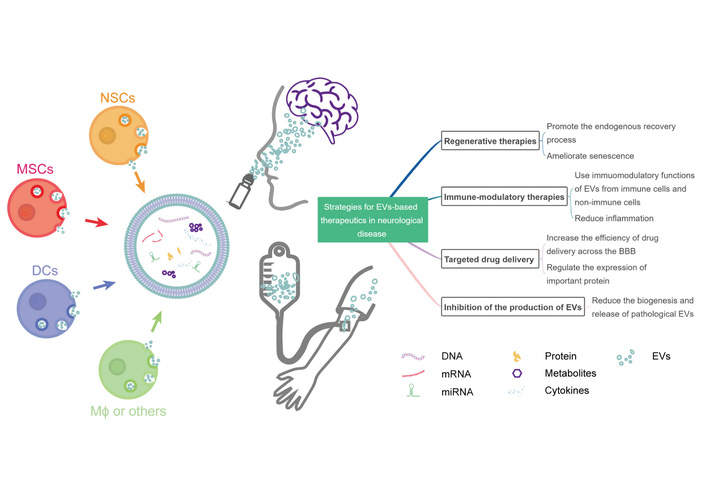

Recent studies demonstrate successful delivery of therapeutic RNA to the brain using engineered EVs. Peptide-modified EVs loaded with CCL2-siRNA effectively delivered therapeutic cargo to spinal cord injury sites, promoting microglial polarization and functional recovery [141, 142]. Heart-targeting EVs conjugated with cardiac-targeting peptides and loaded with NOX4 siRNA showed enhanced therapeutic effects with limited side effects [143]. Intravenous delivery of EVs represents a promising noninvasive route for brain targeting, as it bypasses the BBB [107] (Figure 3). These therapeutic strategies encompass multiple cellular sources and delivery mechanisms for treating neurological disorders.

Therapeutic strategies using extracellular vesicles (EVs) in neurological disorders. The schematic illustrates various cellular sources for therapeutic EVs, including neural stem cells (NSCs), mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), dendritic cells (DCs), and macrophages (Mϕ). EVs can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and deliver therapeutic cargo such as microRNAs (miRNAs), proteins, and drugs to target cells in the central nervous system (CNS). The figure demonstrates the versatility of EV-based therapeutics for treating stroke, neurodegenerative diseases, and other neurological conditions through multiple mechanisms, including neuroprotection, anti-inflammation, and tissue repair. Reprinted from [144]. © 2022 by the authors. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

Genetic materials such as siRNA, miRNA, mRNA, and DNA can be loaded into EVs via electroporation, with hundreds of molecules per vesicle [145, 146]. Electroporation can cause nucleic acid aggregation, which may reduce cargo loading efficiency and cellular uptake [147]. Alternative strategies involve manipulating parent cells for cargo overexpression or using chemical treatment methods [17].

Engineered EVs have advanced from proof-of-concept studies to clinical investigation, with several platforms demonstrating translational potential for neurological disorders. This subsection highlights representative examples spanning different engineering approaches and therapeutic cargoes.

Exosome-adeno-associated virus (exo-AAV) systems combine the advantages of AAV gene therapy with EV-mediated delivery to enhance CNS targeting. Maguire et al. [148] first discovered that AAV particles naturally associate with EVs when isolated from producer cell media, creating vexosomes (vector-exosomes) with enhanced properties. György et al. [149] demonstrated that exo-AAV achieved superior BBB penetration compared to conventional AAV vectors following systemic administration in mouse models. Hudry et al. [150] showed that exo-AAV9 was more efficient at gene delivery to the brain at low vector doses relative to conventional AAV, even when derived from a serotype that does not normally efficiently cross the BBB.

In preclinical studies, exo-AAV6 and exo-AAV9 demonstrated 2–3-fold increased transgene expression in cortical and hippocampal neurons compared to standard AAV vectors at equivalent doses [151]. György et al. [149] successfully used exo-AAV1 to rescue hearing in a mouse model of human deafness by delivering therapeutic genes to inner-ear hair cells. These platforms show particular promise for genetic neurological disorders, including Rett syndrome and spinal muscular atrophy, with ongoing development toward clinical applications [152].

Engineered EVs expressing immunomodulatory cytokines represent an emerging strategy for neuroimmune disorders and brain tumors. Lewis et al. [153] developed exoIL12, consisting of engineered exosomes displaying functional IL-12 on their surface through fusion to the abundant exosomal protein PTGFRN. In preclinical glioblastoma models, intratumoral injection of exoIL12 exhibited 10-fold higher intratumoral exposure than recombinant IL-12 (rIL12) and prolonged IFN-γ production up to 48 hours. In the MC38 syngeneic tumor model, complete responses were observed in 63% of mice treated with exoIL12, compared to 0% complete responses with rIL12 at equivalent IL-12 doses [153]. Importantly, exoIL12 demonstrated superior in vivo efficacy and immune memory without systemic IL-12 exposure and related toxicity, addressing the major limitation that has prevented IL-12 from achieving its therapeutic potential in cancer immunotherapy [153].

While exoIL12 has primarily been studied in cancer models, similar dendritic cell-derived exosome (Dex) approaches have entered clinical testing. Escudier et al. [154] conducted the first phase I clinical trial of Dexs loaded with tumor antigens in metastatic melanoma patients, demonstrating safety and feasibility. A phase II clinical trial utilizing IFN-γ-stimulated autologous Dexs loaded with both MHC-I and MHC-II restricted tumor antigens in non-small cell lung cancer showed NK cell activity promotion with limited T cell activity, though the study met its primary endpoint with 22 of 26 patients completing the maintenance immunotherapy protocol [155].

Several engineered EV platforms for delivering therapeutic RNAs to the CNS have demonstrated efficacy in preclinical models:

Peptide-modified siRNA EVs: Rong et al. [142] developed cardiac-targeting peptide-conjugated EVs loaded with CCL2-siRNA that promoted M2 microglial polarization and functional recovery in rat spinal cord injury models. The engineered EVs achieved site-specific delivery to injury sites, with treated animals showing 40% improvement in locomotor scores compared to controls at 8 weeks post-injury. Similarly, Kang et al. [143] created heart-targeting EVs conjugated with cardiac-targeting peptides and loaded with NOX4 siRNA, demonstrating enhanced therapeutic effects with 60% reduced systemic toxicity compared to soluble siRNA.

Intranasal miRNA delivery: MSC-derived EVs enriched with miR-124 and administered intranasally enhanced neurogenesis and cognitive recovery in stroke models [106, 156]. Yang et al. [106] demonstrated that exosomal miR-124 promoted neurogenesis after ischemic stroke when administered intravenously through the tail vein. They found that delivery achieved therapeutic brain concentrations within 2 hours of administration and bypassed the BBB.

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 RNP delivery: Recent studies demonstrate successful packaging of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes into engineered EVs through electroporation or peptide-mediated loading. Yao et al. [157] showed that EVs could efficiently deliver CRISPR/Cas9 RNPs to achieve gene editing in target cells. Akyuz et al. [158] developed Angiopep-2 and TAT peptide dual-modified EVs loaded with Cas9/sgRNA complexes targeting glutathione synthetase (GSS) for glioblastoma radiotherapy sensitization, achieving effective BBB penetration and tumor targeting. In Huntington’s disease mouse models, EV-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 achieved 15–20% gene editing efficiency in cortical neurons following stereotactic injection [158].

Beyond preclinical studies, several EV-based therapeutics are advancing toward or undergoing clinical evaluation:

MSC-derived EVs for stroke (STARTING-2 trial): Bang et al. [159] conducted a phase 3 randomized controlled trial (NCT01716481) investigating allogenic bone marrow-derived MSC therapy in chronic stroke patients. The trial demonstrated that MSC treatment significantly increased circulating EV levels approximately 5-fold (from 2.7 × 109 ± 2.2 × 109 to 1.3 × 1010 ± 1.7 × 1010 EVs/mL) within 24 hours after injection. Significantly, EV number was independently associated with improvement in motor function (odds ratio: 5.718; P = 0.034) and correlated with neuroplasticity measures on MRI [159]. This represents the first clinical evidence linking EV-mediated mechanisms to therapeutic outcomes in neurological disease.

Scalable MSC-EV production platforms: Son et al. [160] developed a scalable 3D-bioprocessing method for MSC-EV production using micro-patterned wells with tangential flow filtration, addressing a major clinical hurdle for translation. The 3D platform produced EVs with more consistent quality across different lots and donors compared to conventional 2D culture, with upregulation of neurogenesis-associated miRNAs, including miR-27a-3p and miR-132-3p. In stroke models, EV therapy at 1/30th of the cell dose achieved similar therapeutic effects to MSC therapy, demonstrating improved functional recovery on behavioral tests and enhanced anatomical and functional connectivity on MRI [160].

Despite promising preclinical data, several challenges remain for clinical translation: (1) Manufacturing scalability: Current GMP-compliant manufacturing processes require optimization, with 3D culture platforms showing promise for consistent, large-scale production [160]; (2) Cargo loading efficiency: Most loading methods achieve only 10–30% efficiency, necessitating improved loading techniques; (3) Dosing standardization: Preclinical studies use widely varying doses (typically 1–10 μg EV protein per injection in rodents), requiring systematic dose-finding studies; (4) Biodistribution and targeting: While intranasal delivery achieves CNS targeting by bypassing the BBB, optimization of administration routes and targeting strategies remains critical [161]; (5) Long-term safety: Extended follow-up studies are needed to assess potential off-target effects and immunogenicity; and (6) Regulatory pathways: Clear regulatory frameworks for combination biologics (e.g., EVs + genetic cargo) require further development in coordination between academia, industry, and regulatory agencies [162].

Addressing these challenges through collaborative translational research will be essential for realizing the therapeutic potential of engineered EVs in neurological disorders, with several platforms positioned to enter clinical trials within the next 3–5 years.

EVs achieve CNS delivery through multiple BBB penetration pathways. Receptor-mediated transcytosis represents the primary mechanism: Alvarez-Erviti et al. [163] demonstrated that exosomes displaying rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) peptide fused to LAMP2B achieved specific neuronal targeting via nicotinic acetylcholine receptor binding following intravenous administration. Adsorptive-mediated transcytosis occurs through electrostatic interactions between cationic peptides (TAT, Angiopep-2) on EV surfaces and negatively charged endothelial glycocalyx, with dual-modified EVs achieving superior BBB penetration compared to single modifications [164]. Integrin-mediated pathways determine organ tropism: Hoshino et al. [165] showed that EV integrins α6β4 and αvβ5 direct brain-specific homing through preferential brain endothelial cell uptake.

Engineering strategies combine targeting peptide display, size optimization (30–150 nm), and lipid composition adjustments to enhance CNS delivery efficiency. Understanding these mechanisms enables rational design of brain-targeted EV therapeutics for neurological disorders.

Multiple approaches enhance EV targeting specificity. Genetic engineering fuses targeting peptides to abundant EV membrane proteins: Tian et al. [166] developed c(RGDyK)-LAMP2B exosomes, achieving 3-fold increased glioblastoma accumulation via integrin αvβ3 targeting. Chemical conjugation attaches ligands post-isolation using click chemistry, enabling precise control while preserving EV integrity [167]. Bispecific targeting combines BBB-crossing peptides with cell-specific ligands: dual-modified EVs displaying transferrin receptor-binding peptide plus RVG achieved 5-fold higher neuronal delivery versus single modifications [168].

Engineering strategies improve therapeutic payload capacity: (1) Endogenous loading through donor cell transfection achieves 100-fold higher cargo levels than exogenous methods [169]; (2) Electroporation delivers siRNA/mRNA/CRISPR components, with saponin pre-treatment increasing efficiency from 15% to 45% [170]; (3) Hybrid systems combine EV advantages with synthetic materials—EV-liposome hybrids achieve 10-fold higher drug loading while retaining biological targeting [171], while EV-coated nanoparticles provide immune evasion to synthetic carriers [172].

GMP-compliant protocols enable scaled production of engineered EVs at clinical doses (1012–1013 particles per patient), with microfluidic devices providing > 95% batch-to-batch consistency [173]. These advances position EVs as tunable delivery platforms optimized for neurological disorders.

Despite promising advances, several significant challenges hinder the clinical translation of EV-based therapeutics in neurology [174]. EV heterogeneity poses a significant challenge when attempting to isolate and characterize specific subtypes, leading to various protocols with limited standardization [175, 176]. Traditional isolation techniques, such as ultracentrifugation, have low throughput, whereas emerging techniques, like size-exclusion chromatography, require scaling up for clinical applications [177, 178].

Different isolation methods exhibit striking differences in EV nanoscale morphology, surface roughness, and relative abundance of non-vesicles [179, 180]. The body’s scavenging effect on EVs and their heterogeneity enhances the difficulty in determining precise application doses [181, 182]. A crucial question regarding EV utilization as drug delivery vehicles is whether loading exogenous cargoes will interfere with endogenous cargoes, potentially leading to off-target effects [181, 182].

Delivery specificity remains another critical challenge. The heterogeneity of EV cargo leads to inconsistent results in treatment outcomes and mechanisms of action [183]. Limited knowledge of EV biogenesis, heterogeneity, and lack of adequate isolation and analysis tools have hampered their therapeutic potential [184].

The future of EV-based therapeutics in neurology lies in several promising directions. Targeting EV biogenesis represents an emerging strategy, with recent research highlighting the significance of neutral sphingomyelinase 2, ESCRT complexes, and tetraspanin-enriched microdomains in exosome biogenesis and cargo selection [101]. Developing EV-based miRNA biomarkers offers advantages, including cost-effectiveness and information about altered molecular pathways and druggable targets [185].

EV-interference therapies represent an innovative approach, with current studies exploring inhibitors to hinder the release or uptake of EVs, aiming to impede disease progression [186]. EVs can be equipped with specific ligands to target malignant cells, ensuring therapeutic agents reach intended sites with minimal off-target effects [187].

Clinical applications of EV-based therapeutics are being trialed in immunomodulation, tissue regeneration, and as delivery vectors for combination therapies [188]. Modified EVs utilizing specific ligands or antibodies on their surface that bind to receptors on recipient cells further enhance CNS targeting ability. The integration of advanced bioengineering approaches with improved characterization techniques promises to overcome current limitations and unlock the full therapeutic potential of EVs in neurological disorders [189].

EVs represent a paradigm shift in neurological therapeutics, offering dual functionality as both diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic delivery vehicles, though standardization challenges and heterogeneity issues must be addressed for successful clinical translation.

This review summarizes current understanding of EV roles in neurological disorders, with particular emphasis on UBL3 as an essential regulator of EV biogenesis. UBL3 functions as a PTM factor governing protein sorting into sEVs, with Ubl3-knockout mice exhibiting a 60% reduction in protein content in sEVs compared to controls [59]. Recent proteomic analyses identified 1,241 UBL3-interacting proteins, including Ras, revealing extensive regulatory networks [59]. Crucially, UBL3 influences α-synuclein sorting to EVs, with this interaction upregulated under oxidative stress through microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 [31], providing mechanistic insights into protein aggregation in PD.

EVs demonstrate remarkable therapeutic potential across neurological conditions. Pre-clinical evidence strongly supports exosome therapy for stroke, demonstrating significant improvements in neurological outcomes across multiple rodent studies [190]. Hypoxic-preconditioned MSC-derived sEVs promote spinal cord injury recovery through the miR-21/JAK2/STAT3 pathway [191], while intranasally administered MSC-EVs inhibit NLRP3-p38/MAPK signaling after traumatic brain injury [192]. miRNA cargo in EVs, particularly miR-181b, plays a crucial role in promoting angiogenesis and neurological recovery after ischemic stroke [193], and astrocyte-derived exosomal miR-138-5p provides neuroprotection through the regulation of mitophagy [194].

Despite progress, fundamental knowledge gaps persist in EV biology and therapeutic implementation. Current challenges include inconsistent nomenclature, complex characterization protocols, and underdeveloped production methodologies. Clinical trials predominantly utilize bulk EV populations rather than specific subpopulations that may offer enhanced efficacy [195]. Critical questions require investigation, including precise cargo selection mechanisms, the role of UBL3 in disease-specific protein sorting, and the determinants of EV targeting specificity [33, 196].

While EVs can cross the BBB through transcytosis (vesicular transport across endothelial cells), the precise molecular mechanisms governing BBB penetration require further investigation [197, 198]. Engineering approaches enhancing BBB penetration show promise for CNS drug delivery [197, 198]. Transport studies demonstrate differential pharmacokinetics depending on cellular origin and surface characteristics [199, 200]. In vivo validation must address optimal preconditioning protocols, administration routes, biodistribution patterns, and long-term safety assessments [199, 200]. Standardized isolation, characterization, and quality control protocols represent urgent priorities for clinical translation [162].

EV-based liquid biopsies represent a paradigm shift in the detection of neurological diseases. Brain-derived EVs from peripheral biofluids provide CNS molecular signatures through minimally invasive procedures [201]. Breakthrough studies identified plasma EV tau and TDP-43 as specific diagnostic biomarkers for frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and ALS [202]. miRNA profiles in neuron-derived EVs serve as potential biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases [203], with specific alterations identified in psychiatric disorders, including depression and anxiety [204].

The growing demand for personalized neurological treatments drives increased investment in EV-based biomarker development and clinical applications [205]. Machine learning algorithms achieve diagnostic accuracies exceeding 0.88 ROC-AUC scores in neurological disease detection [206]. Gene editing technologies integrated with EV delivery represent the cutting edge of therapeutic development. CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes delivered via engineered EVs enable precise targeting of disease-causing mutations while minimizing off-target effects [207]. Recent advances show promise for treating AD, PD, ALS, and Huntington’s diseases through genetic modifications. Engineered EVs deliver therapeutic RNA molecules into the brain, overcoming traditional nucleic acid delivery barriers [138, 208].

EVs embody a fundamental duality in neurological disorders. As pathological “messengers”, they facilitate intercellular transfer of misfolded proteins, including α-synuclein, tau, and TDP-43, contributing to disease progression through prion-like spreading mechanisms (whereby misfolded proteins propagate between cells and template misfolding in recipient cells) [209, 210]. Altered miRNA profiles in CSF exosomes from Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s patients demonstrate their pathological communication role [202]. Conversely, as therapeutic “modulators”, EVs offer unprecedented neuroprotection and regeneration opportunities. They attenuate reactive gliosis, reduce neuronal death, suppress pro-inflammatory signaling, and improve cognitive functions [211, 212]. Microglia-derived EVs actively participate in stroke neuroprotection and neurorepair [213].

Advanced delivery systems revolutionize EV-based therapeutics. The combination of EV delivery with CRISPR technology enables precise genome editing for neurological disorders, offering potential cures for genetic conditions [214, 215]. Bibliometric analyses reveal exponential growth in CRISPR-EV research, indicating robust scientific interest and clinical translation potential [216]. Artificial intelligence integration with EV-based biomarker discovery, combined with patient-specific engineering approaches, promises personalized neurological medicine [217].

Understanding EV subtypes and their specific roles will enable safer, more effective, disease-tailored therapies [218]. The convergence of UBL3-mediated protein sorting, advanced EV engineering, personalized diagnostics, and precision gene editing positions the field for transformative clinical applications. As we advance toward precision medicine, EVs represent both the molecular messengers defining disease pathogenesis and therapeutic modulators reshaping treatment paradigms, offering new hope for patients with intractable neurological conditions [218, 219].

AD: Alzheimer’s disease

ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Aβ: amyloid-β

BBB: blood-brain barrier

CNS: central nervous system

CRISPR: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

CSF: cerebrospinal fluid

Dex: dendritic cell-derived exosome

ESCRT: endosomal sorting complex required for transport

EVs: extracellular vesicles

exo-AAV: exosome-adeno-associated virus

GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

hnRNPA2B1: heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1

MHC: major histocompatibility complex

mHTT: mutant huntingtin

miRNAs: microRNAs

MS: multiple sclerosis

MSC: mesenchymal stem cell

PD: Parkinson’s disease

PTMs: post-translational modifications

rIL12: recombinant IL-12

RVG: rabies virus glycoprotein

SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage

sEVs: small extracellular vesicles

siRNA: small interfering RNA

SOD: superoxide dismutase

TDP-43: TAR DNA-binding protein 43

UBL3: ubiquitin-like protein 3

MAM: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. MMH: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 3056

Download: 30

Times Cited: 0