Affiliation:

NYU Department of Molecular Pathobiology, New York University, New York, NY 10010, USA

Email: amm9708@nyu.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-9568-6702

Explor Neurosci. 2025;4:1006119 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/en.2025.1006119

Received: September 14, 2025 Accepted: November 12, 2025 Published: December 09, 2025

Academic Editor: Mohamed Seghier, Khalifa University of Science and Technology, United Arab Emirates (UAE)

Although addiction is a complex and contextually embedded disorder that extends beyond individual pathology and neurobiological dysfunction, prevailing computational and clinical models often reduce addiction to a chronic brain disease. While such frameworks have shaped dominant approaches to treatment and theory, they remain poorly aligned with the lived experience and behavioral phenomena of addiction, ignoring its psychological, social, and systemic dimensions. This paper examines the limitations of various disease and compulsion models both critically and in-depth, highlighting their empirical and conceptual shortcomings. In doing so, it argues for the development of context-sensitive and psychologically grounded computational models, ones capable of capturing the nuanced realities of addiction and informing more effective, personalized interventions.

Addiction is an escalating global health crisis, affecting an estimated 296 million people worldwide (ages 15–64 in 2021) [1, 2]. Yet, despite its prevalence, only a small proportion of those affected receive adequate treatment [3]. The consequences of addiction extend far beyond the act of drug use. It affects nearly every aspect of a person’s life, damaging physical health, destabilizing emotions, rupturing relationships, and fueling economic hardship [3]. These burdens are compounded by systemic barriers to care. Stigma among health professionals and structural obstacles in care settings remain pervasive, contributing to physician reluctance to screen, initiate treatment, or support recovery planning [4, 5].

Currently, psychosocial interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and contingency management (CM) remain the cornerstone of treatment [6]. However, meta-analytic reviews suggest these therapies are only modestly effective on average, with some variation by therapy type and substance [7]. Additionally, many individuals need personalized treatment programs, which are often found through trial and error, which prolongs the search for effective care [1]. These limitations suggest a deeper problem, that our models of addiction may be fundamentally misaligned with the lived phenomenon.

The prevailing frameworks in both clinical and computational domains have long conceptualized addiction through the disease model, a chronic, relapsing brain disorder rooted in neurobiological dysfunction [8]. This view has shaped how addiction is studied, treated, and stigmatized. Reinforcement learning (RL)-based computational models, particularly those rooted in temporal-difference (TD) algorithms, are compatible with this framework. These models describe addiction as a pathological compulsion, the consequence of dopaminergic prediction errors that “hijack” value-based decision-making and reinforce maladaptive behaviors over time [9].

While this approach has illuminated important aspects of reward learning, it reduces addiction to a malfunction in brain signaling and neglects the psychological, social, and motivational dimensions that shape drug use. As a result, current models struggle not only to predict relapse or recovery but also to inform interventional and personalized treatments that resonate with the psychological and social dimensions of addiction. To advance both theory and care, we need models that move beyond reductive assumptions and are capable of integrating brain, behavior, and environment.

While the disease model and its computational counterparts, particularly those grounded in dopaminergic RL, have dominated addiction theory, they now face both empirical and conceptual challenges. At the core of these frameworks is the assumption that dopamine is both necessary and sufficient to drive addictive behavior, primarily through distorted reward prediction errors and the reinforcement of habitual use. But this assumption is increasingly untenable.

First, research shows that the reinforcing effects of many addictive substances are mediated through diverse neurobiological systems. Certain drugs, like cocaine, can activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling in parts of the brain, such as the hippocampus and hypothalamus, independently of dopamine D1 receptor subtype involvement, even as their effects in the striatum and prefrontal cortex remain D1-dependent [10]. These findings challenge models that rely exclusively on dopaminergic prediction error signals and underscore the need for frameworks that account for diverse drug-specific mechanisms. Further evidence comes from studies showing that dopamine-deficient mice still develop preferences for cocaine [11]. Additionally, for drugs like opioids, alcohol, cocaine, and nicotine, the opioid receptor was found to have rewarding properties [11]. These findings undermine the idea that dopamine is a universal substrate for reinforcement. Such findings call into question the biological sufficiency of dopamine-centric computational models.

More recent neuroimaging evidence supports this critique. Heinz et al. [12], 2024 argue that rather than a deterministic, ventral-to-dorsal striatal shift leading inevitably to a locked “compulsive” state, habitual behaviour in addiction should be regarded as dimensionally, not categorically, different from goal-directed decision-making and as modifiable by human cognition. The authors contend that compulsive behavior, as defined primarily from animal experimentation, falls short of the clinical phenomena and their neurobiological correlates. Similarly, Robbins et al. [13], 2024 conceptualize compulsivity as a dimensional trait rather than a binary outcome, examining how fronto-striatal systems, including the orbitofrontal, prefrontal, anterior cingulate, and insular cortices and their connections with the basal ganglia, underlie the interaction between goal-directed behaviour and habits across compulsive disorders, including addiction.

More critically, these models struggle to account for the psychological experience of addiction, particularly craving. Craving often persists despite pharmacological interventions aimed at reducing it, or sometimes after long periods of abstinence [14]. Furthermore, the desire to feel a drug’s effects has been shown to be a poor predictor of relapse [15]. This suggests that craving is not simply a function of expected reward, but may reflect a deeper psychological attachment to the act of using, a ritual embedded with emotional meaning and context. This challenges models that conceptualize craving as a simple scalar value tied to expected reward, rather than as a rich and dynamic psychological state. To modernize the evidence base, recent reviews highlight neuroadaptations underlying the incubation of drug craving after abstinence, showing how brain circuits, including limbic and striatal networks, evolve to increase relapse risk [16].

Additionally, drug craving is one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of relapse, yet it tends to be far more resistant to treatment than physical dependence [17]. This dissociation suggests that craving is rooted in psychological processes because, while physical withdrawal symptoms may subside, craving often persists. As such, understanding the mechanisms underlying craving is essential for developing more effective models of addiction and, ultimately, for designing better interventions and treatments.

Equally problematic is the idea that addiction is defined by compulsion, a total loss of control. Philosophers and neuroscientists such as Pickard [18, 19] have argued that addiction is more accurately understood as fragile agency, not its absence. What looks like compulsion may instead be temporal myopia, a tendency to prioritize short-term relief over long-term goals, especially in the context of chronic adversity [18, 19]. Rather than being caused by drugs themselves, this myopia is likely amplified by trauma, poverty, psychiatric comorbidity, and stress [20]. In this view, addiction becomes a coping strategy and a psychological adaptation to conditions that feel inescapable.

This reframing is supported by neuroimaging and empirical research showing that individuals with addiction retain functional goal-directed systems. Mood and stress induction studies show that negative affect can reverse prior devaluation of drugs [21]. Additionally, in concurrent choice tasks, people with greater dependence severity consistently choose drugs over alternative rewards in ways that reflect value-based tradeoffs sensitive to reward magnitude, delay, and effort. Moreover, studies reviewed by Doñamayor et al. [22] (2022) show that while activity in habitual circuits, such as the posterior putamen, increases under certain conditions like stress, negative mood, or high drug-use severity, goal-directed circuits, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and anterior caudate, remain largely intact. Rather than a wholesale shift to habitual control, these findings suggest context-sensitive imbalance between systems, with goal-directed processes still operative and modulated by psychological and situational factors. This explains why CM and cognitive-behavioral therapies, interventions that rely on decision-making and delayed gratification, can be effective. Addiction does not erase agency; it is itself a result of biased, yet conscious, choice.

Neuroimaging studies also reveal that brain regions involved in self-awareness and self-reflection, such as the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex, are active in addiction and most likely involved in decision-making processes [23]. This suggests that addiction is not solely driven by automatic or habitual mechanisms but also engages brain systems responsible for introspection, evaluation, and a sense of self.

Additionally, the existence and widespread commonality of natural recovery cases in addiction further undermine the notion of pure compulsion [24, 25]. Empirical research demonstrates that natural recovery is a widespread and legitimate phenomenon, often characterized by personal motivation, cognitive restructuring, and self-directed strategies [25]. If drug use were truly compulsive in a literal sense, this phenomenon would not be observed. The fact that recovery can occur spontaneously, particularly when environmental stressors are reduced or alternative sources of meaning are introduced, supports the view that addiction is a behavior embedded in context, not a behavior divorced from control [25].

In light of these findings, the disease and compulsion models appear insufficient. While they capture real aspects of drug-induced neuroplasticity and persistent behavior, they ignore the psychological meaning of drug use, impeding the ability to explain variability across individuals, craving, and the influence of the environment. This narrow view has also constrained the power of predictive models. Any computational model that seeks to accurately simulate addiction must therefore incorporate not just neurochemical mechanisms, but individual motivational goals, emotional landscapes, and social context.

Drawing on both empirical studies and her clinical work, Pickard [19, 26] argues that drug use serves as a means to psychological ends. Rather than being solely a pursuit of pleasure, substance use often operates as a coping mechanism—a way to express negative emotion, establish routine, achieve social status and connection, or construct a coherent sense of self when such resources are otherwise unavailable [19, 26]. In this framework, individuals may use drugs not to feel physical pleasure, but as a way to self-medicate in a high-risk environment.

Supporting this perspective, recent studies show that access to meaningful social interaction can suppress drug self-administration in rats, even after extended use or periods of abstinence. One such study found that when given the choice, rats consistently preferred social interaction over drug use, a protective effect that persisted across drug classes, doses, and addiction severity [27]. These findings underscore the role of social alternatives in reshaping motivation and emphasize that addictive behavior is sensitive to environmental conditions, not simply driven by pharmacological reinforcement.

Crucially, this framework does not dismiss the neurobiological effects of drugs. Instead, it highlights that these effects are interpreted through the lens of lived experience, personal meaning, and emotional need. Within this view, addiction emerges not from moral failure or irreversible brain dysfunction, but from attempts to navigate psychological distress in unsupportive environments.

This framework naturally extends from emotional to physical pain. Chronic pain, much like chronic emotional distress, alters how individuals attend to, evaluate, and cope with persistent aversive states. Both forms of suffering engage overlapping neural systems, most notably the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and anterior insula, the core hubs of the brain’s salience network, along with medial and dorsolateral prefrontal regions implicated in distress regulation and decision-making that can heighten attention to pain signals, amplify perceived salience, and bias choice behavior toward short-term relief [27].

In chronic pain, relief-seeking often includes or centers on opioid use, where the pursuit of analgesia and the regulation of emotional suffering intersect within shared motivational and affective circuits [28]. Over time, this process can evolve from adaptive pain management into a negative-reinforcement pattern, as the motivation to alleviate pain becomes conditioned to opioid-related cues and increasingly intertwined with the drug’s emotional and motivational effects [29].

Together, these findings suggest that the convergence of chronic pain and addiction reflects parallel adaptations to persistent distress, one primarily physical, the other emotional, rooted in shared salience-network and prefrontal control systems that mediate relief-seeking and dysregulated motivation [27, 28].

This reconceptualization carries important implications. It reframes addiction as a contextually embedded strategy for managing suffering, and in doing so, it challenges stigma, informs treatment, and lays the foundation for computational and clinical models that are both more explanatory and more humane.

Although the disease model and the compulsion model of addiction often reduce drug use to a malfunctioning brain or an involuntary compulsion, it would be equally misleading to treat addiction as purely psychological. Drug use is shaped not only by psychology and environment, but also by physiological constraints. A compelling illustration of this interaction is the compulsion zone model proposed by Norman and Tsibulsky [30] (2006), which demonstrates that drug-seeking behavior is not continuous or random, but emerges within a narrow physiological window.

In their rodent self-administration studies, Norman and Tsibulsky [30] found that cocaine-seeking only occurred when drug concentrations in the body fell between two thresholds: a priming threshold, below which no drug-seeking occurred, and a satiety threshold, above which behavior was also suppressed. Within this compulsion zone, the animals repeatedly self-administered the drug, but outside it, the behavior ceased. This pattern suggests that drug-taking is regulated by pharmacokinetics, not merely by subjective desire.

Importantly, animals adjusted their intake to maintain stable internal drug concentrations [30]. When the unit dose of cocaine was increased, rats simply waited longer between doses. This finding challenges classical RL models, which predict that larger rewards should increase response rates. Instead, these data suggest that internal physiological regulation, rather than escalating subjective desire, guides the structure of drug use.

However, while the compulsion zone model offers a valuable physiological account of drug-use timing, it should not be mistaken for a model of pathological compulsion. Drug-seeking within the zone is probabilistically modulated, not reflexively or irrationally compelled. For example, even drug-experienced rats consistently choose social interaction over drugs like methamphetamine and heroin when given the choice, indicating that pharmacokinetics shape motivation, but do not override volition [31]. What changes is not the presence of control, but the likelihood of certain behaviors under specific internal states.

Moreover, the compulsion zone model is directly contradicted by a well-documented phenomenon in addiction research called the incubation of craving. Grimm et al. [32] (2001) found that after a period of abstinence, rats exhibited increased drug-seeking behavior over time, even though no drug remained in their system. The growing intensity of craving in the absence of any pharmacological input challenges the premise of the compulsion zone model, that the physiological effects of the drug primarily drive drug-seeking behavior. Instead, incubation points to psychological processes, such as associative learning, expectation, and memory, as key contributors.

Rather than viewing biology and psychology as competing explanations, this understanding of addiction invites a more nuanced synthesis. Internal pharmacokinetics modulate motivational salience, but this salience is also shaped by internal contexts. Addiction is not merely a malfunction of homeostatic regulation, nor is it a failure of will. It is a dynamic, context-sensitive process in which biological constraints and subjective meaning continuously interact.

Computational models have become essential tools for formalizing theories of addiction, translating behavioral patterns into mechanistic explanations of learning and decision-making. Yet these models differ profoundly in what they prioritize, some emphasize habit formation, others focus on goal-directed planning, cue-driven motivation, or belief-based inference. Each framework offers valuable insights, but none offers a complete picture of addiction yet [33]. Most comparative efforts have focused on mechanistic detail rather than psychological plausibility, namely, how closely these models capture the emotional, cognitive, and contextual dynamics that define addiction. This gap is critical as addiction cannot be modeled without these components. A systematic comparison that foregrounds these dimensions highlights not only each model’s strengths, but also their blind spots, particularly in accounting for different facets of craving, recovery with and without intervention, and intra- and inter-individual variability.

To evaluate these frameworks consistently, the present section compares them according to four criteria: (1) the range of addiction phenomena they can explain (e.g., craving, relapse, incubation of craving, natural recovery); (2) their ability to account for both inter-subject variability (differences between individuals) and intra-subject variability (fluctuations within the same person over time); (3) the extent and type of empirical support they draw from behavioral, neuroimaging, and biological studies; and (4) their formal tractability and practical applicability to computational psychiatry. These criteria serve as a benchmark for assessing each model’s scope and limitations in the sections that follow.

The models are organized historically and conceptually, beginning with early reinforcement-learning accounts TDRL, then expanding through dual-system and incentive-sensitization frameworks, neurocognitive accounts such as impaired response inhibition and salience attribution (iRISA), and finally to Bayesian and active-inference approaches. This order reflects how the field has progressively incorporated motivation, cognition, and subjectivity into computational theories of addiction.

Key terms and phenomena in addiction modeling:

• Craving: An intense, often cue-triggered motivational state to seek the drug, independent of hedonic pleasure.

• Incubation of craving: A time-dependent increase in craving intensity during abstinence.

• Relapse: Return to drug use following abstinence, typically precipitated by cues, stress, or context.

• Natural recovery: Spontaneous remission without formal treatment, reflecting relearning.

• Inter-subject variability: Stable differences between individuals in addiction vulnerability or treatment response.

• Intra-subject variability: Fluctuations within the same person over time in craving, motivation, or control.

RL has long served as the dominant computational paradigm in addiction neuroscience, with MF-RL forming the foundational framework for many early theories, as it aligns with traditional concepts of addiction as an automatic, inflexible disorder of habit [34, 35]. In these models, agents learn through trial-and-error associations, with value assigned to actions based solely on experienced rewards. Cached values are updated through reward prediction errors, the discrepancy between expected and received rewards, and stored without representing causality or future consequences and planning [8]. This learning mechanism is implemented in computational models via TD learning, where midbrain dopamine signals are thought to encode reward prediction errors that reinforce preceding actions [36]. Therefore, TDRL is the type of MF-RL that is used in addiction modeling.

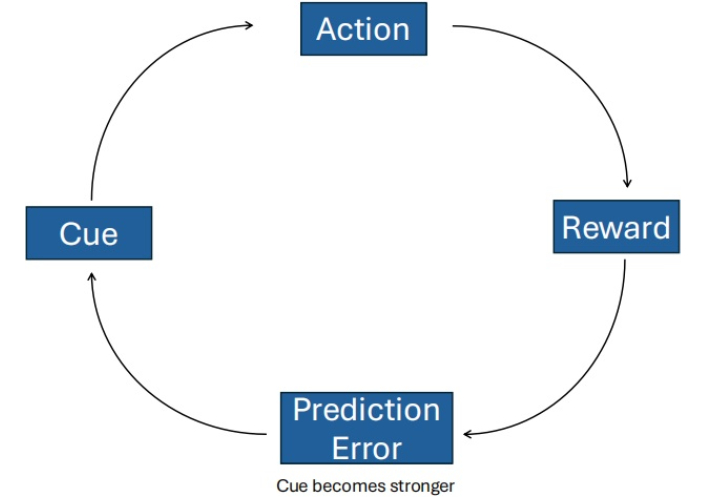

In TDRL models of addiction, it is theorized that the brain’s learning systems are hijacked, leading to the overvaluation of drug-related cues (see Figure 1). Repeated exposure produces drug-evoked dopaminergic signals that can mimic, co-opt, or dysregulate normal prediction errors within cortico-striatal circuits, particularly the ventral striatum, thereby strengthening the cached values of drug-related cues and actions [36]. Neuroimaging and lesion studies implicate the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and dorsolateral striatum in mediating the transition from goal-directed to habitual control in this process, suggesting a neural substrate for the shift modeled by TDRL [37]. Empirically, Groman et al. [38] (2019) found that chronic methamphetamine self-administration disrupted both model-based (MB) and MF-RL in rodents, supporting the core assumption that addiction involves dysregulated reinforcement-learning mechanisms.

Temporal-difference reinforcement learning (TDRL) model of addiction. Under normal conditions, midbrain dopamine signals encode the difference between expected and received rewards (reward prediction error), thereby updating the value of actions. In a drug-exposure scenario, repetitive and non-physiologic elevations of dopamine may mimic persistent positive prediction errors, driving exaggerated valuation of drug-paired actions or cues. Over time, this may bias the agent toward stimulus-response (habitual) responding and cue-driven drug-seeking, via strengthened cortico-striatal loops (particularly dorsal striatum) at the expense of goal-directed control.

Over time, associated cues can drive compulsive drug-seeking through habitual stimulus-response mechanisms, even if the drug no longer produces pleasure, as behavior becomes less responsive to outcome value [37]. These maladaptive associations, driven by habitual control, prove resistant to extinction or outcome revaluation, continuing to influence behavior even after the drug’s rewarding effects have diminished, and leading to the traditionally compulsive characteristics of addiction. This mechanism forms the basis of Redish’s influential TDRL computational model of addiction [9, 37].

Within this framework, TDRL models account for several hallmark features of addiction. They help explain the development of habitual drug use and the persistence of behavior despite negative consequences. These models also capture relapse after extinction through the assumption that relapse occurs due to the enduring influence of cue-triggered cached values that resist updating [39]. However, relapse has also been modeled through a modified TDRL framework to capture the steep relearning of relapse after true extinction [40]. Additionally, these models can be modified to account for inter-individual variability in addiction trajectories by adjusting parameters such as learning rate or reward sensitivity, reflecting how different individuals may be more or less vulnerable to developing addiction [9]. Currently, TDRL models have shown predictive power in preclinical studies, such as Groman et al. [38] (2019), finding that rats with initially weaker MF learning prior to drug exposure self-administered significantly more methamphetamine.

Yet, TDRL models fall short in several critical respects. They do not account for craving, a core feature of addiction. In particular, TDRL models struggle to capture phenomena such as incubation of craving, cue generalization, and outcome-specific craving [41]. They fail to capture the effects of psychology on craving, removed from any physiological effects, like dopamine levels. Furthermore, they fail to model intra-individual variability, the dynamic fluctuations in craving, motivation, and drug use that occur within the same individual over time [33]. This omission limits their ability to represent addiction as a temporally evolving, psychologically complex disorder and impedes their predictive power.

Additionally, TDRL models offer no account of relearning and, therefore, no account of recovery. Both natural recovery and therapeutic abstinence, through CBT or CM, require flexible learning, belief revision, and insight, capabilities that TDRL does not support [42]. As a result, TDRL cannot simulate why or how individuals stop using drugs. They cannot explain why some people quit spontaneously or change through therapy.

A common critique of this model lies with the fact that dopamine alone is insufficient to account for the full range of drug effects on the brain. As previously discussed, dopaminergic mechanisms, while central to many RL models, do not capture the complexity of addiction. Redish [9] (2004), in his influential paper, acknowledged that dopamine-based models are unlikely to explain all aspects of addictive behavior. While MF-RL provides valuable insights into certain addiction phenomena, its reliance on dopamine is increasingly challenged by evidence implicating non-dopaminergic systems. Furthermore, it remains uncertain whether dopamine alone is responsible for generating the reward prediction error signal that these models depend on [35].

Another caveat to these models is that they fail to explain the role of conscious deliberation or planning in drug use. They model behavior as unconscious and compulsive, but many individuals actively plan, strategize, and pursue drugs in goal-directed ways. Additionally, abstinence in the face of strong cues, such as in CM trials, likely depends on engaging MB, deliberative control processes, which are effortful and flexible, in contrast to the habitual responses of the MF system [43]. Thus, TDRL alone cannot account for the success of therapies that rely on cognitive, deliberative processes, or for drug-seeking behaviors that require flexible, goal-directed decision-making [44].

Finally, TDRL cannot explain why people initiate drug use. Initial drug use is often a rational, goal-directed behavior in response to emotional distress, trauma, or social context, not an unthinking response to cues. The model presumes prior exposure and offers no generative explanation of use as self-medication or emotional regulation.

Although MF-RL models explain habit formation and relapse, they misrepresent addiction as purely compulsive and dopamine-driven. They ignore introspection, internal context, and the meaning people assign to drug use. They cannot explain recovery or craving divorced from cues or pharmacology. And their explanatory gaps grow more glaring in light of research showing that addiction often involves conscious, biased decision-making, not pure habit.

TDRL models remain the most empirically supported, extensively studied, and widely adopted frameworks in the computational modeling of addiction. Their strength lies in modeling habitual behavior and elucidating core learning mechanisms. Despite their contributions, these models are fundamentally incomplete. Their continued dominance reflects a broader tendency toward mechanistic reductionism, offering elegant solutions to narrowly defined problems. Addiction is not solely a disorder of compulsion or dopamine, it is a complex, dynamic process. To truly understand addiction at its root, we must move beyond models that reduce behavior to reward and prediction error. Instead, we must begin with the psychological experience of addiction, thereby enabling a more targeted investigation into the underlying molecular and neurobiological mechanisms.

Dual-system models of RL first became prominent in addiction science in 2008. It proposes that behavior emerges from the interplay between two distinct learning systems, an MF and an MB system. The MF system relies on habitual stimulus-response associations based on cached rewards, and the MB system simulates future outcomes and guides behavior through internal planning and inference [27]. These systems differ in both computational cost and behavioral flexibility [35]. The MF system is fast and metabolically efficient but inflexible, relying on habitual stimulus-response associations. In contrast, the MB system is slower and more resource-intensive, but it enables planning, inference, and adaptive decision-making [35]. An arbitration mechanism, supported by prefrontal and striatal circuits, dynamically allocates control between MB and MF systems based on their relative reliability in a given context (see Figure 2) [45].

Empirical work has demonstrated this neural arbitration directly. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Lee et al. [45] (2014) identified distinct prefrontal and inferior lateral regions that track the reliability of MB vs. MF systems, dynamically modulating which system guides behavior. This finding provides a mechanistic foundation for the theoretical “switching” process postulated in dual-system accounts.

The dual-system framework posits that behavior results from competition between two interacting systems: a goal-directed (MB) system that plans and evaluates outcomes, and a habitual (MF) system that relies on cached stimulus-response associations. A central arbitration mechanism dynamically allocates control based on context and reliability. In addiction, chronic drug use and stress bias this arbitration toward habitual control, weakening prefrontal goal-directed processes and leading to automatic, cue-driven drug seeking.

In parallel, rodent work by Lesaint et al. [46] (2014) showed that dual-learning models with factored representations successfully reproduce individual differences in sign- vs. goal-tracking behavior, linking behavioral phenotypes to differential engagement of MF and MB mechanisms. Complementary human behavioral research has also found that individuals with substance use disorders exhibit reduced sensitivity to outcome devaluation (Byrne et al. [47], 2019), suggesting that substance use behavior biases the arbitration process toward habitual control.

This dual-process framework has been influential in computational psychiatry and has been widely applied to addiction research. It extends the habitual account offered by MF-RL by explaining both the onset and the persistence of drug use. In this framework, early drug use is often goal-directed, driven by specific emotional or social goals. Over time, with repeated training, control shifts from the MB to the MF system, rendering behavior more habitual and less sensitive to changes in outcomes or long-term consequences, due to differences in the speed and flexibility of value estimation between the systems [35, 48].

Critically, this framework explains why individuals may continue using substances despite negative outcomes. The goal-directed system becomes weakened by chronic drug use and stress, while the habitual system dominates. This helps explain the persistence of drug use even when individuals logically see the costs as a psychological conflict borne from simultaneously active systems with opposing goals [47].

Moreover, dual-system models offer several theoretical advantages over MF-RL frameworks. Account for outcome-specific motivation by positing a goal-directed system capable of forming expectations about drug outcomes and evaluating their current value, while also recognizing the additive influence of habit and Pavlovian processes in shaping craving and behavior [49]. Additionally, these models can address intra-individual variability. For example, Lesaint et al. [46] (2014) incorporated factored representations into a dual-system RL model to reproduce individual differences in sign- and goal-tracking behavior in rats, demonstrating that with the appropriate representational structure, dual-system models can account for both behavioral patterns and corresponding dopaminergic activity. These models also align with observed deficits in delayed discounting and executive function seen in addiction. Finally, they help explain why treatments such as working memory training, episodic future thinking, or potentially CBT and CM, which target and support deliberative control and goal-directed processing, can be effective for some individuals with addiction [50, 51]. Together, these features provide a more comprehensive and psychologically grounded model.

However, dual-system models also face important limitations. Like many computational models of addiction, they struggle to fully account for all facets of craving. For example, dual-system models fall short in accounting for incubation of craving, as they typically lack mechanisms for representing time-dependent increases in motivational value during abstinence, in the absence of ongoing reinforcement [16]. Additionally, dual-system models struggle to explain craving that emerges without explicit external cues, persisting after drug or dopamine administration. Or why the desire for sensation of a drug’s effects is a poor predictor of relapse. Furthermore, these models struggle to account for extreme or irrational emotional states, which may limit their ability to capture the affective and motivational complexity of craving and compulsive behavior in addiction [52]. Although they are closer to a psychologically integrated model, dual-system models are incomplete in their account of craving.

Finally, like the TDRL framework, dual system models struggle to explain natural recovery, providing no mechanism for how learned associations can change without intervention. While it could be argued that MB systems reassert control, dual-system models cannot specify how this occurs, nor can they model the deeper reappraisal and meaning-making processes that underpin long-term change.

Importantly, empirical research offers conflicting assumptions of the dual-system model of addiction, particularly the notion that addictive behavior arises from a simple dominance of habitual, MF control. While dual-system and disease models often depict addiction as a compulsive hijacking of behavior, numerous clinical and experimental studies indicate that individuals with substance use disorders frequently retain intact goal-directed decision-making capacity [22]. Behavioral evidence suggests that drug use is often a deliberate, outcome-sensitive choice made in response to negative affect, with substances valued for their anticipated ability to relieve distress rather than engaged through automatic habits alone [21]. This framing helps illuminate why dual-process models may struggle to fully capture certain patterns of addiction, such as binge drinking, which do not fit neatly into a simple habitual vs. goal-directed dichotomy and may instead involve complex imbalances between reflective and affective-automatic systems [53]. Instead, such episodic and emotionally triggered behaviors are better understood as forms of affect regulation, shaped by context and internal state, rather than by fixed learning systems alone.

This is further supported by findings from CM paradigms, where individuals with addiction are able to abstain when offered alternative rewards, indicating preserved MB function. Lastly, computational modeling of rodent decision-making demonstrates that methamphetamine disrupts both MB and MF learning processes independently, contradicting the common assumption that addiction entails a simple shift from goal-directed to habitual control [38]. Collectively, these findings suggest that addiction may reflect a pathological revaluation of drug-related outcomes under emotionally salient conditions, rather than a breakdown of control. This challenges the strict dichotomy between habitual and goal-directed systems and calls for more nuanced models that account for affective, motivational, and contextual influences on behavior.

Dual-system models have provided a valuable conceptual advancement over purely MF accounts by incorporating goal-directed planning, arbitration mechanisms, and behavioral variability. They offer a more psychologically nuanced view of addiction, accounting for partial treatment responsiveness and certain individual differences in drug-seeking behavior. Nonetheless, significant limitations remain. These include an inability to represent time-dependent processes like the incubation of craving, difficulty modeling natural recovery without external intervention, and insufficient mechanisms for integrating emotional and contextual factors that shape decision-making in addiction.

Critically, while influential in theory, many components of dual-system models, particularly the clean separation and competitive arbitration between systems, have limited empirical validation, leaving much of the framework speculative. These models require further empirical validation before they can serve as comprehensive explanatory frameworks. As such, these models currently function more as scaffolds than as fully grounded explanatory tools. Addressing these gaps will require computational frameworks that are more tightly integrated with affective neuroscience, contextual dynamics, and the lived psychological reality of addiction.

First proposed in 1993, the IST of addiction has remained an active and evolving framework, continually refined through ongoing empirical research. It advances addiction theory by introducing a fundamental distinction between “liking” (hedonic pleasure) and “wanting” (motivational salience) [54]. This framework challenges the assumption that drug use persists due to continued pleasure, proposing instead that repeated exposure sensitizes mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, especially the nucleus accumbens, leading to pathological “wanting” and disproportionate motivational salience assigned to drug-associated cues (see Figure 3) [55]. Conditioned reward cues can acquire strong motivational power, eliciting approach behavior and robust neural responses even after the reward is fully predicted, suggesting that cue-triggered motivation may persist independently of the reward’s hedonic impact (“liking”) [56].

Repeated drug exposure sensitizes the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, producing a pathological dissociation between “liking” (hedonic pleasure) and “wanting” (motivational salience). Over time, “wanting” continues to increase even as “liking” declines, driving craving and relapse. Drug-associated cues acquire excessive motivational power through this sensitization process, triggering compulsive pursuit even when the drug is no longer pleasurable.

This dissociation between “wanting” and “liking” has been demonstrated across multiple empirical studies. Electrophysiological recordings from the ventral pallidum show that neuronal firing intensifies as drug-predictive cues approach, even when the hedonic value of the reward remains constant [56]. Such firing patterns shift from prediction-error coding toward incentive-salience coding, supporting the notion of dynamic, cue-triggered “wanting” amplification, independent of value learning [56]. Moreover, individual variation in dopamine transporter (DAT) function and dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens core predicts the extent of cue-triggered reactivity in the nucleus accumbens, providing a mechanistic basis for differential vulnerability to addiction [57]. Together, these findings align with the incentive-sensitization hypothesis that mesolimbic sensitization amplifies cue-driven “wanting” independently of subjective pleasure, a distinction consolidated by Berridge and Robinson [55] (2016). These neural mechanisms correspond to clinical observations of individuals who continue to crave drugs they no longer find pleasurable, and who relapse in response to environmental cues through cue-triggered motivational states, rather than through deliberate, goal-directed planning [45].

Notably, this sensitization process is long-lasting, and once triggered, the motivational salience of cues can intensify even during abstinence, reflecting a form of persistent neuroplasticity that traditional RL frameworks cannot easily explain [55].

IST models also provide a good account for both inter- and intra-individual variability in addiction. First, broader IST literature highlights how fluctuating brain states, linked to emotional and physiological changes such as stress or intoxication, modulate craving intensity within the same person over time [55]. Secondly, trait-level differences in dopaminergic reactivity can shape how powerfully cues acquire incentive salience across individuals [57]. For example, the observed differences between sign-trackers and goal-trackers demonstrate that individuals who assign greater motivational value to drug-related cues are more prone to relapse triggered by those cues, supporting the idea that variability in how people’s brains attribute incentive salience to cues contributes to inter-individual differences in addiction vulnerability [57].

These models offer a more comprehensive account of craving than earlier theories, which attributed craving mainly to conditioned responses or fluctuating drug levels. The IST explains craving’s persistence well beyond withdrawal and its occurrence even in the absence of obvious external cues, by proposing that mesolimbic sensitization makes the brain’s motivational systems hyper-reactive to drug cues and contexts, including imagined ones [55]. As a result, craving can be triggered not only by drug-associated cues or physiological states, such as withdrawal or hunger, but also by internally generated imagery or emotions, factors that do not rely on external stimuli or pharmacological deprivation. This helps explain the experience of craving in the absence of immediate drug cues or withdrawal symptoms. Furthermore, IST suggests that sensitized “wanting” may intensify during abstinence, accounting for the incubation of craving and the long-term vulnerability to relapse, even after withdrawal [55].

However, despite its strengths, IST falls short in several areas. First, it offers little insight into recovery, particularly natural recovery [25]. The theory conceptualizes sensitization as a durable, possibly irreversible neuroadaptation, yet provides no mechanism for desensitization, compensatory learning, or the identity transformations that support long-term abstinence. Second, while IST is compatible with behavioral therapies aimed at reducing cue reactivity, it does not explain how psychotherapy induces internal psychological change. It lacks mechanisms for belief updating, cognitive reappraisal, or reflective narrative processes that psychotherapy emphasizes as central to lasting therapeutic change [58].

Critically, although IST casts craving into a new light, effectively explaining cue-triggered as well as state-triggered urges and incubation of craving, it fails to explain all craving phenomena. Although IST models move beyond framing craving as the desire to feel a drug’s effects or a physiological compulsion, IST does not fully capture the role of the symbolic meaning of the drug or the need to explain craving divorced from physiological stimulation [11]. This suggests the need for more psychologically integrated models, possibly those incorporating the default mode network or self-reflective properties, in order to properly model addiction and predict behavioral phenomena. Moreover, IST also lacks the capacity to model outcome-specific craving, such as selective urges for particular substances based on emotional or situational context, a feature better captured by goal-directed or MB frameworks.

Although IST moves beyond purely hedonic or pharmacological accounts of craving, it still centers dopamine as the key mechanism in its framework. However, craving has been shown to persist despite dopamine-targeted pharmacological interventions, and drug preference can still emerge in dopamine-deficient mice. This highlights that dopaminergic sensitization alone is insufficient to explain the full phenomenology. Finally, craving is dissociable from physical dependence, often outlasting withdrawal symptoms and remaining a stronger predictor of relapse, pointing to the need for models that incorporate explanations outside of physiological craving.

The iRISA model, first proposed by Goldstein and Volkow [59], offers a neurocognitive framework for understanding addiction as the product of two interacting dysfunctions, an impaired top-down executive control and exaggerated salience attribution to drug-related cues. These dual impairments result in heightened attentional and motivational responses to drug stimuli alongside a reduced capacity to inhibit maladaptive behavior, particularly in drug-related contexts [60, 61].

While not formally an RL model, iRISA has conceptual overlap with computational theories of valuation and decision-making. The model aligns with the concept that enhanced cue-reactive valuation processes, amplified by chronic drug use, can dominate over reflective, goal-directed decision-making, even when individuals consciously intend to abstain (see Figure 4) [62]. These effects are especially pronounced under conditions of cognitive load, drug cue exposure, or impaired metacognitive awareness [63].

iRISA is supported by robust empirical evidence. The top-down and salience attribution processes used in the iRISA model are thought to involve large-scale brain networks including the limbic-orbitofrontal reward system, the salience network, the prefrontal executive control network, the self-referential (default mode) network, and subcortical circuits involved in habit and memory. Systematic neuroimaging reviews have confirmed consistent abnormalities in exactly these networks across individuals with various substance use disorders [23, 60, 61]. In particular, meta-analytic evidence demonstrates reproducible patterns of dysregulation within the salience and executive control networks, marked by hyperactivation of the anterior insula and ACC during cue exposure, and hypoactivation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) during inhibitory control tasks [23]. These findings establish a neural signature of impaired response inhibition and excessive salience attribution that directly supports the iRISA framework.

The iRISA framework describes addiction as a dysfunction in the balance between exaggerated salience attribution and weakened inhibitory control. Drug cues excessively activate salience and limbic networks (insula, striatum, ACC), while prefrontal executive regions—DLPFC and ACC—fail to exert sufficient top-down regulation. This imbalance leads to enhanced cue-reactivity, impaired inhibition, and compulsive drug-seeking. Recovery may involve partial rebalancing of these systems through neuroplastic adaptation or treatment-induced restoration of prefrontal control.

Moreover, longitudinal work has shown that partial normalization of these network abnormalities predicts clinical recovery and treatment success, underscoring the model’s translational relevance [61]. The default mode network plays a crucial role in self-referential processing, introspection, and integrating past experiences, making it essential for understanding how addicted individuals process internal states and maintain maladaptive drug-related beliefs [23]. These disruptions have been empirically linked to addiction-related outcomes such as cue-reactivity, craving, escalation of drug use, and relapse, supporting the model’s core theoretical claims. Crucially, recent work shows that these networks can be modulated by abstinence, treatment, or neurostimulation, underscoring the model’s clinical relevance and its predictive validity regarding both dysfunction and recovery potential [61].

The iRISA model offers a compelling account of craving, particularly in explaining why it may persist after drug administration or during prolonged abstinence. This is attributed to enduring dysregulation in salience attribution and prefrontal inhibitory control, which renders drug cues disproportionately powerful even in the absence of hedonic drive [61]. It also accommodates the phenomenon of incubation of craving by implicating long-term neuroplastic changes in frontostriatal circuits [23]. Furthermore, the model recognizes that craving may emerge not from a desire to feel the drug’s effects, but from conditioned motivational states and compulsive urges to engage in drug-taking behavior.

This model also provides a solid account for inter-individual variability. The iRISA model explains both inter-individual and intra-individual variability in addiction by highlighting differences in the extent and pattern of dysfunction in prefrontal control and salience networks across individuals, influenced by genetics, drug history, and environment [23]. Although the literature has not yet explicitly addressed the iRISA model’s capacity to explain intra-individual variability, this variability can be understood through the model’s consideration of fluctuating emotional and brain states within an individual.

Although the iRISA model does not explicitly incorporate natural recovery, it provides a valuable neurobiological framework that can partially explain this phenomenon through its focus on neuroplasticity and individual variability [61]. Neuroimaging evidence shows that the neural processes incorporated in the iRISA model may recover over time, with sustained abstinence, or following environmental changes [61]. This implies that, under favorable conditions, brain circuits involved in addiction can reorganize and regain function even in the absence of formal treatment. However, the model currently lacks explicit mechanisms to account for how higher-order psychological and social factors, such as identity transformation from being an addict, long-term motivation, and meaning-making, initiate and maintain sustained recovery. Consequently, while iRISA offers a robust neurobiological foundation for understanding aspects of natural recovery, it remains incomplete without integration of these critical psychological dimensions. Future research should aim to extend the iRISA framework by incorporating psychological, social, and contextual factors to provide a more comprehensive account of self-initiated change and long-term recovery.

The iRISA model represents one of the most comprehensive and empirically grounded frameworks in addiction neuroscience. By integrating neurobiological, cognitive, and motivational components, it explains not only compulsive drug use and persistent craving but also the neural mechanisms underlying relapse and potential recovery. Its alignment with findings across multiple large-scale brain networks lends strong empirical and clinical support. The model also currently falls short of capturing the full psychological and social complexity of addiction, particularly in the context of natural recovery. Expanding the iRISA framework to incorporate identity, motivation, and other higher-order processes offers a promising direction for future research, potentially bridging the gap between brain-based dysfunction and the lived experience of recovery. Models like iRISA, when enriched with these dimensions, may ultimately pave the way for a holistic understanding of addiction, one that connects cognitive and behavioral symptoms to their molecular, cellular, and systems-level underpinnings.

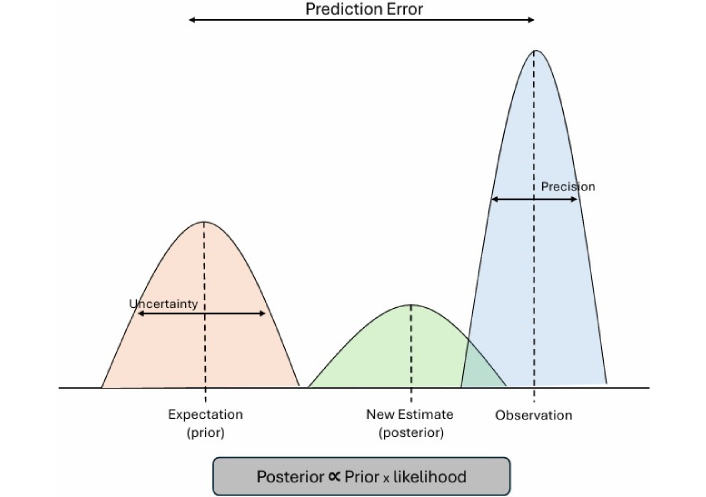

Bayesian models offer a transformative framework for understanding addiction, not as reflexive compulsion or rigid habit, but as an inferential, belief-driven process shaped by context, emotion, and uncertainty. The Bayesian brain theory (BBT) models the brain as a system that represents sensory information probabilistically and performs Bayesian inference by combining prior beliefs and incoming sensory data weighted by their relative uncertainty (precision) (see Figure 5) [62]. This allows the brain to continuously update its internal representations of the world in a statistically optimal manner. This process of belief updating, rather than simple RL, becomes the central mechanism of cognition and behavior. Addiction, in this view, is not merely a loss of control but a failure of inference, where deeply held, high-precision priors about drug relief, emotional regulation, or self-worth persist even in the face of contradictory evidence [63].

Bayesian and active inference models of addiction. Adapted from [64]. Copyright © 2019 Yanagisawa, Kawamata and Ueda. CC BY.

Recent extensions of Bayesian approaches, particularly the free energy principle and active inference frameworks, further expand this paradigm by formally unifying perception, learning, and action under a single predictive processing architecture [65]. In these models, addiction emerges when maladaptive priors dominate belief updating and action selection, leading to cycles of craving and relapse that minimize short-term uncertainty at the expense of long-term well-being. These active inference formulations complement Bayesian models by embedding them within a generative, embodied framework that links neural dynamics to behavior.

Addiction can be conceptualized as a failure of inference, where high-precision maladaptive priors (e.g., “using will relieve distress”) dominate the brain’s predictive hierarchy. Under this framework, drug cues and interoceptive states are misinterpreted through biased expectations, reducing sensitivity to prediction errors and preventing belief updating. Dopaminergic systems encode the precision, or confidence, of beliefs, meaning that chronic drug use amplifies pathological certainty in maladaptive priors. Recovery and therapy can be modeled as processes of revising these priors through new evidence and experiences that re-establish adaptive inference.

Bayesian models have found growing support across computational neuroscience and psychiatry, where they have been used to explain perception, decision-making, and learning, and increasingly, disorders like schizophrenia, anxiety, and substance use disorders [63]. In addiction, they provide elegant accounts of phenomena that traditional RL models struggle to explain. For example, they model craving even in the absence of drug-related cues, framing it as an internal inference based on high-confidence priors about drug efficacy and reframing the idea of craving as a predictive, belief-driven expectation [14].

These models capture the phenomenon of outcome-specific craving by demonstrating how prior beliefs about particular rewards selectively shape craving responses to those specific outcomes [41]. Using this same Bayesian framework, craving can be understood as a belief about internal physiological and emotional states (such as stress or discomfort) linked to performing an addictive action, exemplified by pathological priors like “I must gamble to feel good.” [14]. Furthermore, persistent craving after treatment can be understood as arising from hyper-precise prior beliefs that are resistant to extinction or updating by new evidence [14]. Finally, these models can explain incubation of craving by showing how, during abstinence, the brain increasingly infers the return of latent causes linked to drug use, causing craving to intensify even without direct drug cues [41]. Collectively, they reframe addiction as a fundamentally psychological process rather than one driven solely by hedonic pleasure or compulsive behavior.

Importantly, the BBT of addiction is increasingly supported by converging neurobiological evidence that grounds its computational principles in identifiable brain mechanisms. One line of support comes from predictive coding theory. This theoretical structure has gained empirical backing through studies of cortical microcircuits, which show that prediction and error signals are mediated by anatomically and pharmacologically organized signaling pathways [66]. Top-down predictions are carried from higher to lower cortical areas by N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated signaling in deep-layer pyramidal neurons, while bottom-up prediction errors are transmitted upward by α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor activity in superficial-layer pyramidal neurons [66]. These pathways correspond to the Bayesian process of belief updating, in which prior expectations are compared to incoming evidence and adjusted to reduce error over time.

Neuromodulators such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine play a fundamental role in encoding precision, the confidence assigned to prior beliefs and sensory inputs, in hierarchical Bayesian brain processing [17, 66]. This view of belief updating recognizes that dopamine is not the sole neuromodulator involved, but part of a broader system through which multiple transmitters collectively shape inference and behavior, offering a more biologically realistic account of how the brain operates. In this view, dopamine is not merely a scalar reward signal as in TD learning but functions as a key modulator of uncertainty and precision, influencing how strongly internal predictions or external data update beliefs [17, 66]. Dopamine, in this case, tunes the brain’s confidence in its interpretations of the world, a process that can be influenced by the effects of drugs.

Bayesian frameworks for addiction are not only conceptually rich but empirically predictive. A study demonstrated that neural responses to Bayesian prediction errors measured during a stop-signal task effectively differentiated methamphetamine-dependent individuals who relapsed within one year from those who maintained abstinence, indicating potential predictive biomarkers for relapse risk [67]. Likewise, Bayesian observer models of craving have successfully reproduced subjective urge dynamics in neuroimaging data, demonstrating that craving can be quantitatively modeled as belief updating about internal states [17]. More recently, Bayesian inference frameworks have also been applied to behavioral addictions such as gambling, where craving and compulsion emerge from maladaptive prior expectations about reward probability and uncertainty [14]. Together, these findings support the idea that addiction can be formally characterized as an inferential process shaped by precision-weighted priors, providing a bridge between neurocomputational mechanisms and subjective craving.

These models also offer a formal account of recovery as belief updating provides a natural explanation for how psychotherapies like CBT help patients revise maladaptive priors in response to new experiences or perspectives [68]. This same mechanism may also help explain natural recovery, where individuals adjust their beliefs and behaviors without formal treatment.

From a psychological perspective, Bayesian inference provides a powerful framework for modeling complex phenomena such as internal conflict and fragmented agency. In addiction, this often appears as a struggle between the desire to quit and the compulsion to continue using. Bayesian models capture this dynamic through the coexistence of multiple competing priors and continuously evolving belief states. This approach reframes drug-seeking behavior as rational within a distorted belief system, rather than purely irrational or compulsive, thereby preserving a sense of agency while accounting for its apparent impairment or “fragmentation”, as discussed by Neil Levy.

While these models remain less mature in terms of circuit-level specificity compared to other models, they are increasingly recognized as flexible, extensive, and predictive. Their current lack of detailed mapping onto addiction-relevant structures like the ventral tegmental area (VTA) or nucleus accumbens is a reflection of current empirical underdevelopment, not theoretical limitation [17].

Bayesian inference thus represents a significant shift in how we conceptualize addiction. It bridges neurobiology, psychology, and subjectivity in a way that neither dopamine-centric nor habit-based models can. Rather than seeing addiction as a binary of control vs. compulsion, Bayesian approaches see it as a dynamic process of belief formation and revision, shaped by uncertainty, prior experience, and context. While empirical integration remains ongoing, the theory’s predictive power, conceptual sophistication, and compatibility with craving, therapy, and other addiction phenomena make it a uniquely promising tool for advancing both our scientific and clinical understanding of addiction.

Taken together, the models trace a progression from mechanistic (TDRL) to psychologically integrated accounts (dual-system, IST, iRISA) and finally to inference-based frameworks (Bayesian/active inference). Each offers distinct strengths—empirical tractability (TDRL), psychological realism (dual-system, IST), neurocognitive specificity (iRISA), and integrative breadth (Bayesian). The section’s criteria and Table 1 clarify where each succeeds or falls short across the core phenomena and variability.

Comparative summary of major computational models of addiction, showing their key mechanisms, behavioral focus, empirical grounding, and limitations.

| Model | Key mechanism | Main brain systems | Behavioral focus | Strengths | Limitations | Empirical support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDRL/MF-RL | Dopaminergic reward-prediction error learning; cached stimulus-response values drive behavior. | VTA, ventral/dorsal striatum, OFC. | Habit formation, persistence, relapse. | Mechanistically precise; explains compulsion and habit strength. | Neglects craving, flexible thinking, emotion, recovery, intra-individual variability; dopamine-centric. | Rodent neurophysiology & RL behavior; ventral striatum (Keiflin and Janak [36] 2015); OFC & DLS, habit shift (Lucantonio et al. [37] 2014); Rodent RL (Groman et al. [38] 2019). |

| Dual-system (MB + MF) | Arbitration between goal-directed (MB) and habitual (MF) control. | Lateral PFC, OFC, ACC, striatum. | Transition from voluntary to compulsive use. | Captures flexibility vs. habit; links to CBT/CM. | Limited account of craving, emotion, and spontaneous recovery. | fMRI arbitration (Lee et al. [45] 2014); rodent modeling (Lesaint et al. [46] 2014); behavioral devaluation (Byrne et al. [47] 2019). |

| Incentive-sensitization theory (IST) | Sensitized mesolimbic dopamine amplifies cue-triggered “wanting” independent of pleasure. | Nucleus accumbens, VTA, ventral pallidum, PFC. | Craving, cue-reactivity, relapse. | Distinguishes “wanting” vs. “liking”; explains persistent cue-driven craving. | Lacks mechanisms for recovery, cognition, and symbolic meaning; dopamine-centric. | VP electrophysiology (Tindell et al. [56] 2004); DAT variation (Singer et al. [57] 2016); Review (Berridge and Robinson [55] 2016). |

| iRISA | Exaggerated cue salience + impaired executive inhibition. | Insula/ACC (salience), DLPFC/IFG (control), striatum, DMN. | Cue-reactivity, craving under weak control, and relapse. | Integrates cognition and motivation; strong imaging evidence; recovery correlates. | Limited modeling of belief/identity change or natural recovery. | Neuroimaging meta-analyses (Zilverstand et al. [23] 2018; Ceceli et al. [61] 2025; Zilverstand and Goldstein [60] 2020). |

| Bayesian/Active inference | Maladaptive high-precision priors bias inference about drug relief; craving as predictive belief. | Cortical predictive-coding circuits; dopamine/serotonin systems. | Cue reactivity, craving, relapse, and recovery as belief updating. | Unifies cognition, emotion, and context; models craving without cues. Accounts for natural recovery and identity change. | Abstract; limited circuit-level data; early empirical base. | Computational & imaging (Gu and Filbey [17] 2017; Harlé et al. [67] 2019; Kulkarni et al. [14] 2023). |

ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; CM: contingency management; DAT: dopamine transporter; DLPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; fMRI: functional magnetic resonance imaging; iRISA: impaired response inhibition and salience attribution; MB: model-based; MF: model-free; OFC: orbitofrontal cortex; RL: reinforcement learning; TDRL: temporal-difference RL; VTA: ventral tegmental area.

Addiction is a multifaceted, context-dependent disorder that traditional dopamine-centric models, such as TDRL and habit-based frameworks, only partially capture. These models notably fall short in explaining core aspects like craving, psychological motivation, therapeutic effects, and the mechanisms of recovery. Dual-system models advance the field by integrating the interplay between habitual and goal-directed control, emphasizing preserved decision-making flexibility that both initiates drug use and provides therapeutic targets. However, empirical support for these models remains limited, and they struggle to account for natural recovery or the dynamic nature of craving.

IST contributes a critical distinction between persistent, cue-triggered “wanting” and hedonic pleasure, illuminating how sensitized motivational circuits sustain craving beyond direct drug effects. While IST bridges the biological and psychological dimensions of craving, it does not adequately address outcome-specific craving or spontaneous recovery.

Furthermore, the iRISA model further enriches our understanding by highlighting impaired executive function and aberrant salience attribution as central drivers of addiction’s persistence. By incorporating the default mode network alongside flexible learning and memory processes, iRISA effectively explains many addiction phenomena and is supported by promising clinical predictive data. These models are presently under development, expanding to incorporate both macro-level psychological phenomena and further neurobiological mechanisms behind addiction. More research has to be done in order to bridge these levels.

Finally, Bayesian approaches represent a paradigm shift by conceptualizing addiction as a dynamic process of belief updating that seamlessly integrates craving, agency, and recovery into a unified computational framework. This approach excels at incorporating complex psychological functions and has demonstrated clinical predictive power, including the identification of neurobiological biomarkers, thus bridging behavior and internal beliefs with underlying brain mechanisms. Currently, these models remain neurobiologically underdeveloped and are therefore largely theoretical, although promising.

Looking ahead, the future of addiction science lies in developing integrative models that synthesize neurobiology, psychology, and environmental context. Such holistic frameworks will be crucial for accurately predicting individual addiction trajectories and tailoring personalized interventions, ultimately advancing both scientific insight and effective clinical care.

ACC: anterior cingulate cortex

BBT: Bayesian brain theory

CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy

CM: contingency management

DLPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

iRISA: impaired response inhibition and salience attribution

IST: incentive-sensitization theory

MB: model-based

MF: model-free

MF-RL: model-free reinforcement learning

RL: reinforcement learning

TD: temporal-difference

During the preparation of this work, the author used Grammarly for readability and language. After using the tool/service, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

AMM: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. The author read and approved the submitted version.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 2536

Download: 32

Times Cited: 0