Affiliation:

2Department of Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, University of Babylon, Hillah 51002, Babylon, Iraq

Explor Neurosci. 2025;4:1006117 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/en.2025.1006117

Received: July 14, 2025 Accepted: November 09, 2025 Published: December 01, 2025

Academic Editor: Dirk M. Hermann, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany

Primary central nervous system lymphoma is a rare form of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma that is confined to the brain, spinal cord, leptomeninges, or eyes, representing less than one percent of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas and approximately four percent of primary brain tumors. When the disease is truly isolated to the central nervous system, with no evidence of systemic spread, it poses unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, particularly in immunocompetent patients. We reviewed nine recently published cases from 2021 to 2024 that described isolated primary central nervous system lymphoma without extracranial involvement. Patients ranged in age from forty-four to eighty-five years, with both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed individuals represented. Presenting symptoms include focal neurological deficits, seizures, progressive confusion, cranial neuropathies, and neurolymphomatosis. Magnetic resonance imaging findings were diverse, including intra-axial masses, leptomeningeal and cranial nerve enhancement, and mass effect. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was variably positive for lymphoma cells. Histopathological analysis confirmed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in all cases, although initial biopsies were sometimes inconclusive, underscoring the importance of repeat tissue sampling and expert pathology review. Treatment strategies most often included high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy, monoclonal antibody therapy, and radiotherapy, with some patients undergoing surgical decompression or diagnostic craniotomy. Follow-up data revealed variable survival outcomes, with a subset of patients achieving disease-free survival beyond one year. These cases highlight the wide clinical spectrum and diagnostic complexity of isolated primary central nervous system lymphoma and reinforce the need for a high index of suspicion, timely advanced imaging, multidisciplinary discussion, and appropriate tissue diagnosis to guide individualized management.

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is an aggressive, rare, non-Hodgkin lymphoma occurring in the brain, spinal cord, leptomeninges, or eyes, with no involvement of a non-central nervous system (CNS) site at the time of presentation. PCNSL differs from secondary CNS lymphoma (SCNSL), which represents CNS dissemination from systemic lymphoma, typically multifocal and often leptomeningeal [1–3]. Accounting for fewer than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas and about 4% of all primary brain tumors, PCNSL predominantly occurs in immunocompetent adults and is almost uniformly the diffuse large B-cell type (90–95%) [4]. Incidence has increased three- to fourfold since the late 1970s, particularly among elderly, immunocompetent individuals [5–7]. Population-based data (Netherlands, SEER) show a steady rise unrelated to HIV infection, reflecting a true increase in isolated PCNSL cases [5, 6]. Immunocompetent PCNSL now accounts for > 90% of cases [6].

Immunocompromised PCNSL (HIV, transplant) has declined since ART introduction [6]. Its clinical presentation varies widely, in many cases featuring focal neurologic deterioration, changes in neuropsychiatric function, seizures, or signs and symptoms suggesting intracranial hypertension, often causing delayed or missed diagnoses [4, 7]. Symptom onset typically is subacute (days to weeks), reflecting mass effect and local infiltration [8, 9].

Radiographically, PCNSL presents as single or multiple homogeneously enhancing, often large, masses in the periventricular white matter, basal ganglia, or corpus callosum, simulating high-grade glioma, metastasis, or infections [3]. Although stereotactic biopsy is the procedure of choice, histopathological verification may be delayed as necrosis may obscure the tissue or sampling may be non-diagnostic.

Below is Table 1 with the most common features that somehow differentiate PCNSLs from SCNSLs [1–3].

Distinguishing features between PCNSL and SCNSL.

| Feature | PCNSL | SCNSL |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | De novo in CNS | Metastatic from systemic lymphoma |

| Number of lesions | Usually solitary or a few | Often multiple |

| Enhancement | Homogeneous | Meningeal/Dural involvement is common |

| Location | Deep parenchymal | Leptomeningeal, subependymal |

| Systemic disease | Absent | Present in staging (PET/BM biopsy) |

PCNSL: primary central nervous system lymphoma; SCNSL: secondary central nervous system lymphoma; CNS: central nervous system.

We report a case of isolated PCNSL. The diagnosis was established after the patient underwent three biopsies. The patient initially presented with gradual confusion and was ultimately diagnosed with an intramedullary mass in the medial temporal lobe. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). The consent to participate was waived because the data is anonymously reported. Hence, it was not required.

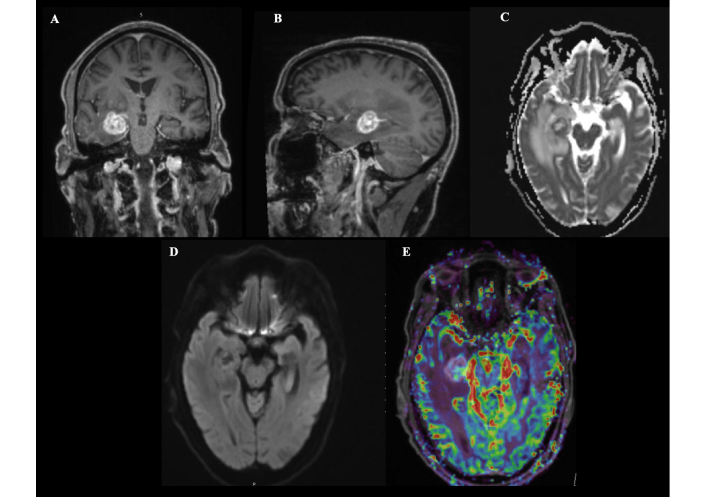

A 64-year-old male with a medical history significant for hypertension, a prior complicated left femoral fracture managed with hardware removal and a Girdlestone procedure, and a recent episode of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing urosepsis was admitted for evaluation of a right temporal brain lesion. He initially presented with progressive confusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a right medial temporal lobe intra-axial lesion with associated vasogenic edema and midline shift, with a differential diagnosis including lymphoma, tuberculoma, or abscess (Figure 1).

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging findings of a right temporal lobe lesion. Magnetic resonance imaging reveals a well-defined, rounded lesion in the deep medial right temporal lobe measuring approximately 20 mm × 18 mm × 20 mm (anteroposterior × transverse × craniocaudal) (A: coronal; B: sagittal). The lesion demonstrates contrast enhancement and is surrounded by significant vasogenic edema, causing mass effect on the temporal horn and mild compression of the adjacent basal cistern, without significant midline shift (C). Diffusion-weighted imaging shows peripheral restriction with central facilitation (D), and perfusion imaging reveals increased cerebral blood volume, suggestive of a high-grade lesion (E).

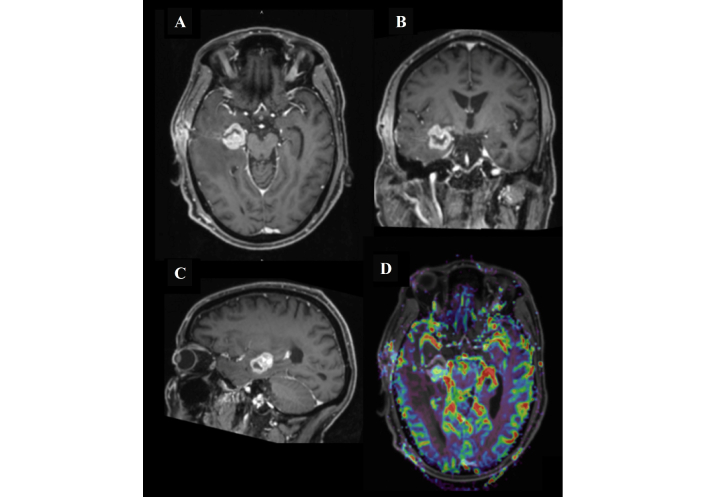

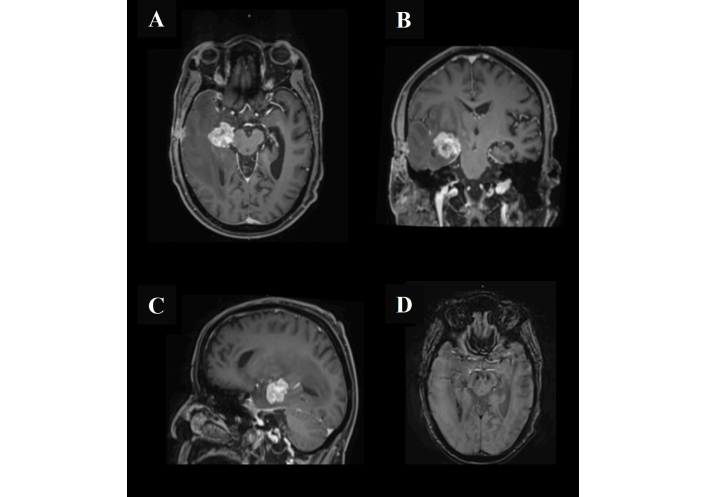

The patient underwent an initial stereotactic biopsy in November 2024 (Figure 2 is the post-operative MRI). A second biopsy was performed in December 2024 (Figure 3 is the post-operative MRI); however, both procedures were inconclusive, with histopathology demonstrating atypical lymphocytic proliferation with extensive necrosis. The first biopsy was (CD45+), and the second one immunohistochemical stains showed a positive cluster of differentiation 20 (CD20), paired box gene 5 (PAX-5), B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2), and multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM1); CD10 and BCL6 were negative, and cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene (C-MYC) was equivocal. External pathological consultation failed to yield a definitive diagnosis. Given the ongoing clinical suspicion of PCNSL, he received a single cycle of R-MP (rituximab, methotrexate, procarbazine) chemotherapy on 21 January 2025 but subsequently developed methotrexate toxicity. Hepatitis B core antibody testing returned positive, and entecavir prophylaxis was initiated. During this period, the patient developed a left lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and was started on therapeutic anticoagulation with enoxaparin, later transitioned to apixaban due to new-onset atrial fibrillation.

MRI of the head after the first surgical biopsy procedure. Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a right medial temporal lobe lesion measuring 2.5 cm × 2.2 cm × 2.3 cm (anteroposterior × transverse × craniocaudal). The lesion shows intense post-contrast enhancement with an open ring configuration laterally (A, B, and C), corresponding to the stereotactic biopsy tract extending to the right temporal bone, accompanied by postoperative changes in the subgaleal soft tissues. There is extensive surrounding vasogenic edema with associated effacement of the right lateral ventricle. MR perfusion (D) demonstrates a mild elevation in cerebral blood flow, and MR spectroscopy reveals a relative increase in the choline peak. Additionally, bilateral periventricular and left subcortical T2/FLAIR hyperintense foci are noted.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the head after the second biopsy. The lesion exhibits intense post-contrast enhancement with a characteristic open ring laterally, corresponding to the stereotactic biopsy tract extending to the right temporal bone. Associated postoperative changes are evident in the subgaleal region (A, B, and C). There is a clear progression of the surrounding vasogenic edema with resultant effacement of the right lateral ventricle (D). No other significant interval changes were observed.

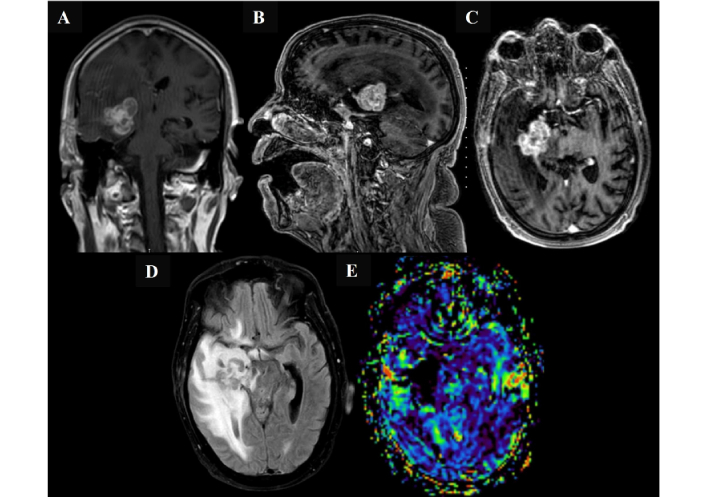

Following review by the multidisciplinary team (MDT) and given an unchanged lesion size on serial MRI (Figure 4), a third biopsy was performed via right temporal craniotomy and open biopsy on 12 March 2025. The lesion appeared intra-axial, firm, and greyish intraoperatively; debulking was limited to tissue sampling following diagnostic confirmation.

Magnetic resonance imaging findings following initial chemotherapy in March 2025, before the open biopsy surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrates a deep seated right medial temporal lobe intra-axial mass with interval progression in size, now involving the right gangliocapsular region. The lesion shows predominantly low signal intensity on both T2- and T1-weighted images, with corresponding low apparent diffusion coefficient values and intense heterogeneous post-contrast enhancement. The lesion measures 3.4 cm × 2.9 cm × 3.6 cm (anteroposterior × transverse × craniocaudal) (A, B, and C). Marked progression of adjacent vasogenic edema and regional mass effect are noted, including effacement of the right lateral and third ventricles with right temporal horn dilatation (D). A midline shift of 3.6 mm toward the left is also observed. No other significant interval changes were detected. There is no evidence of elevated relative cerebral blood volume on perfusion imaging (E).

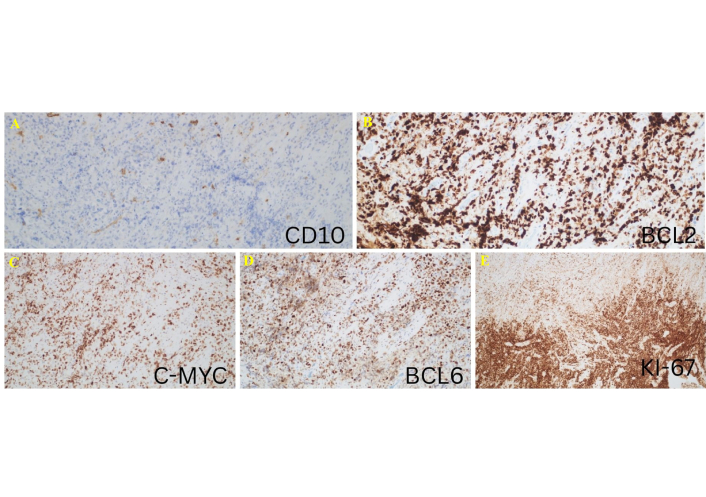

Intraoperative frozen section (Figure 5) and final histopathology confirmed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), establishing the diagnosis of PCNSL (Figures 6 and 7). Histopathological evaluation of a stereotactic biopsy from the right temporal region revealed classic features of primary CNS DLBCL (PCNS-DLBCL), a high-grade extranodal lymphoma known for its aggressive behavior and characteristic angiocentric growth pattern. This case demonstrated diffuse infiltration of large pleomorphic lymphoid cells with vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and irregular nuclear contours, embedded within the brain parenchyma. The tumor exhibited a predominantly angioinvasive architecture, with concentric perivascular cuffing and extension into the adjacent neuropil. Geographic necrosis, numerous apoptotic bodies, and brisk mitotic activity were evident. Frozen section analysis already suggested lymphoma, which was confirmed on permanent sections with strong immunoreactivity for B-cell markers, including CD20, CD79a, and PAX-5. The neoplastic cells showed positive staining for BCL2, BCL6, MUM1, and C-MYC (expressed in approximately 70% of cells), while being negative for CD10, CD5, and CD30-consistent with a non-germinal center B-cell (non-GCB) phenotype. Focal or disrupted CD21 staining indicated disturbed follicular dendritic cell meshwork. The Ki-67 proliferation index was markedly elevated (~90%), and Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA in situ hybridization (EBER-ISH) was negative. These findings align with the prototypical immunophenotype of PCNS-DLBCL, which frequently shows MUM1 and BCL6 co-expression and is driven by myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MYD88) and CD79B mutations in many cases, although molecular testing was not performed in this instance. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was negative for MYC rearrangement, thus excluding double-hit lymphoma despite the high expression of C-MYC. Taken together, these features support a final diagnosis of DLBCL, not otherwise specified (NOS), confined to the CNS.

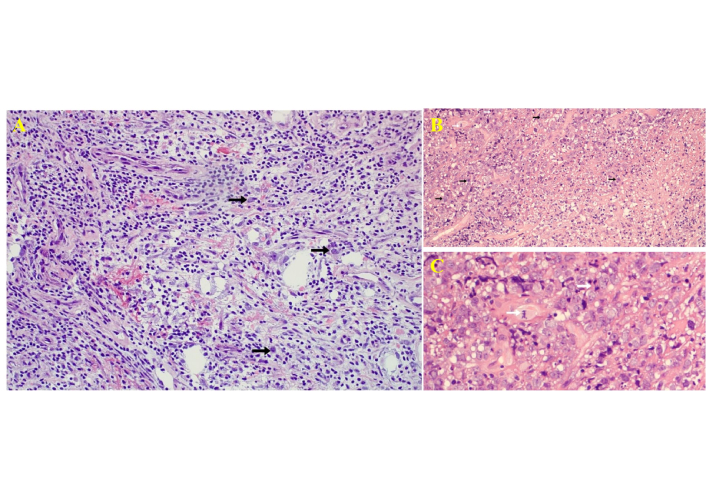

Histological images of the frozen section taken during the third biopsy procedure. (A) Frozen section showing infiltration of large atypical lymphoid cells in brain parenchyma with angiocentric distribution [hematoxylin and eosin (HandE) staining, low-power, ×200]. (B) Permanent section (HandE, ×100) showing diffuse infiltration by pleomorphic lymphoid cells with perivascular distribution. Black arrows indicate atypical lymphoid cells. (C) High-power magnification highlighting mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies (white arrows). HandE, ×400.

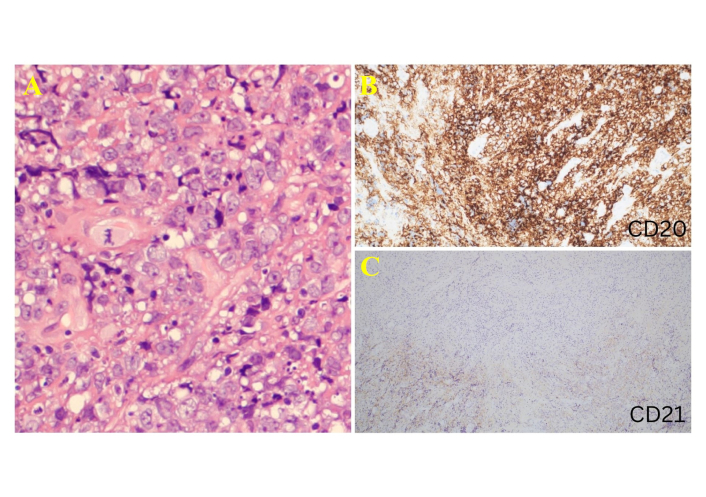

Histological images of the specimen taken during the third biopsy procedure. (A) High-power hematoxylin and eosin (HandE, ×600) staining image showing large pleomorphic cells with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli. This is an enlarged (higher-magnification) view of a region shown in Figure 5C. (B) CD20 immunostain showing strong diffuse positivity in neoplastic B cells (CD20 immunostaining, ×200). (C) CD21 highlights focal and disrupted follicular dendritic meshwork (CD21 immunostaining, ×100).

Histological images showing the staining characteristics of the specimen from the third biopsy procedure. (A) CD10 negativity supports a non-germinal center B-cell (non-GCB) phenotype. (B) Strong cytoplasmic B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) expression. (C) Cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene (C-MYC) is positive in approximately 70% of tumor cells. (D) BCL6 positivity in neoplastic cells. (E) Ki-67 proliferation index (Ki-67 PI) was approximately 90%, indicating high proliferative activity. Immunostaining, ×100.

Postoperatively, the patient developed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, managed with beta-blockers. He also experienced gram-positive bacteremia (Staphylococcus species) treated with intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam. His postoperative course was further complicated by transient confusion and drowsiness; however, no persistent focal neurological deficits were noted.

On 27 March 2025, he was admitted to the National Center for Cancer Care and Research (NCCCR) for radiation therapy and subsequently completed 10 whole-brain radiotherapy sessions by 9 April 2025. At the time of discharge on 24 April 2025, the patient was stable, awake and oriented, with no new focal neurological deficits. Apixaban, metoprolol, antihypertensive therapy, and prophylactic antimicrobials (valacyclovir, TMP-SMX, entecavir) were continued. Outpatient rehabilitation was planned in line with institutional policies regarding inpatient rehabilitation for patients with active malignancy.

PCNSL remains a rare but challenging entity, accounting for a small fraction of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas and primary brain tumors. This brief review of recent case reports highlights the heterogeneous presentations of isolated PCNSL, which can involve brain parenchyma, cranial nerves, spinal cord, or leptomeninges [1–3] (Table 2). This diversity often leads to diagnostic delays, particularly when initial biopsies are inconclusive or when imaging mimics other pathologies such as infections or inflammatory lesions [10, 11].

Summary of recently reported cases of isolated PCNSL.

| Article | Age (years) | Gender | Immune status | Site | Histology | CSF findings | Imaging | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. [12] | 53 | Male | Immunocompetent | Thoracic epidural (T7–T9) | DLBCL, CD20+ | Lymphoma cells present | MRI: epidural mass, T7–T9 | Decompressive laminectomy, chemo, RT |

| Chen et al. [13] | 65 | Female | Immunocompetent | Leptomeningeal (thoracolumbar) | DLBCL, CD20+ | WBC‚ Üë, lymphoma cells | MRI: meningeal enhancement T11‚ ÄìL3 | High-dose MTX + rituximab |

| Lobban et al. [14] | 67 | Female | Immunocompetent | Cranial nerves (trigeminal, facial) | DLBCL, CD20+, BCL2+, BCL6+ | Pleocytosis, inconclusive | MRI: cranial nerve enhancement | Steroid, rituximab, MTX, WBRT |

| Khanna et al. [15] | 85 | Male | Immunocompetent | Intraventricular | DLBCL, CD20+ | Negative | MRI: intraventricular masses | Rituximab-MTX ×8 cycles |

| Zayed et al. [10] | 64 | Female | Immunosuppressed (post-LT) | Right frontal lobe | DLBCL, CD20+ | Negative | MRI: frontal lesion, PET negative | R-MP chemo |

| Schuster Bruce and Grammatopoulou [11] | 66 | Female | Immunocompetent | Skull base (sphenoid, Meckel‚ Äôs cave) | DLBCL, CD20+, BCL6+, MIB1 high | Not reported | MRI/PET: skull base, dura | MATRIX regimen |

| Sheng et al. [16] | 63 | Female | Immunocompetent | Cranial nerves, neurolymphomatosis | DLBCL, CD20+ | Pleocytosis, no malignant cells | MRI: cranial nerves | CHOP ×2 cycles |

| Xue et al. [17] | 44 | Female | Immunocompetent | Frontal, parietal, periventricular | DLBCL, non-GCB | Negative | MRI: periventricular lesions | CHOP ×2 cycles |

| Cheng et al. [18] | 35–69 (mean 55) | 2 female, 6 male | Immunocompetent | Intraventricular system (lateral and fourth ventricles) | DLBCL | Not specified (pathology diagnosis) | Solitary, cluster-like, or diffuse ventricular lesions with hydrocephalus | Surgical resection in all; 3 received high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy and radiotherapy; others declined adjuvant therapy |

BCL2: B-cell lymphoma 2; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PCNSL: primary central nervous system lymphoma.

Consistent with established literature, these cases confirm that DLBCL is the predominant histological subtype, with immunohistochemical staining for B-cell markers such as CD20 serving as a critical diagnostic tool [16–18]. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis, while supportive in some cases, may be non-diagnostic and should not delay tissue confirmation.

Management typically requires a multidisciplinary approach involving neurosurgery, oncology, radiation therapy, and, when indicated, infectious disease consultation. High-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy remains the backbone of treatment, often supplemented with rituximab and, in selected cases, whole-brain radiotherapy [12, 13]. Recent case experiences also underscore the importance of vigilant supportive care, including infection prophylaxis and management of treatment-related complications [10].

These reports collectively reinforce the need for early suspicion of PCNSL in patients with atypical neurological presentations and focal CNS lesions. They also illustrate that despite therapeutic advances, the prognosis remains guarded, with outcomes dependent on factors such as lesion location, performance status, and timely initiation of appropriate therapy. Ongoing reporting of such cases contributes to improved recognition, diagnostic strategies, and the refinement of therapeutic protocols for this rare malignancy.

Isolated PCNSL remains a rare but diagnostically challenging entity that requires a high index of clinical suspicion, especially in patients presenting with atypical neurological symptoms and mass lesions confined to the CNS. These cases demonstrate that diagnosis often demands advanced neuroimaging, repeated tissue sampling when initial biopsies are inconclusive, and expert histopathological assessment to confirm DLBCL or other relevant subtypes. Management typically involves high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy, monoclonal antibody therapy, and when indicated, whole-brain radiotherapy or targeted surgical intervention for diagnostic or decompressive purposes. Early recognition and timely multidisciplinary discussion are crucial to improve outcomes, given the potential for variable treatment responses and disease progression despite initial therapy. Accumulating further well-documented cases will help refine best practices for diagnosis and management and may guide the development of standardized treatment protocols for this uncommon presentation.

BCL2: B-cell lymphoma 2

CD20: cluster of differentiation 20

C-MYC: cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene

CNS: central nervous system

DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

MUM1: multiple myeloma oncogene 1

PAX-5: paired box gene 5

PCNS: primary central nervous system

PCNSL: primary central nervous system lymphoma

SCNSL: secondary central nervous system lymphoma

A Msheik: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. MH: Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. AA: Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. A Mohamed: Investigation, Visualization, Data curation. AFAH: Resources, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. HS: Resources, Writing—review & editing. KM: Visualization, Writing—review & editing. AT: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval was not required for this study, in accordance with the guidelines of the Medical Research Committee at Hamad Medical Corporation. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

The consent to participate was waived because the data is anonymously reported.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1628

Download: 24

Times Cited: 0