Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Kuala Terengganu 20400, Malaysia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5219-7317

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Kuala Terengganu 20400, Malaysia

2Centre for Research in Infectious Diseases and Biotechnology (CeRIDB), Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Kuala Terengganu 20400, Malaysia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9644-6925

Affiliation:

3Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara 705018, Uzbekistan

Email: malikamonov@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8279-8471

Explor Immunol. 2026;6:1003236 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2026.1003236

Received: August 15, 2025 Accepted: December 25, 2025 Published: January 26, 2026

Academic Editor: Wenping Gong, The Eighth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital, China

The article belongs to the special issue Novel Vaccines development for Emerging, Acute, and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases

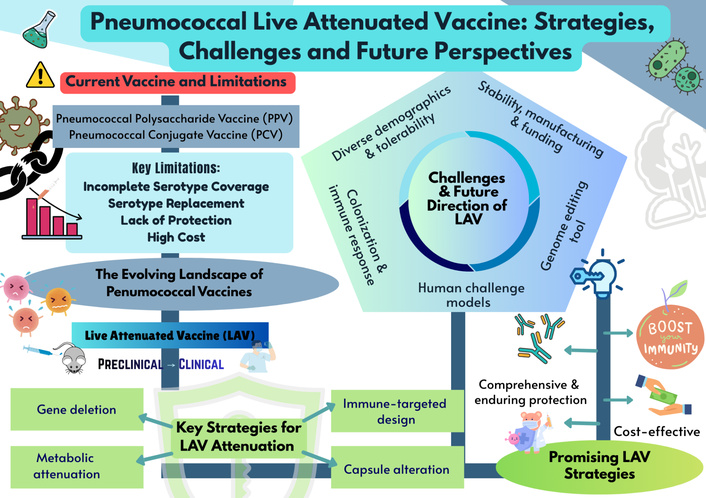

Pneumococcal disease remains a major global health challenge despite the availability of polysaccharide and conjugate vaccines. Although these platforms have reduced invasive disease, their limitations, such as poor immunogenicity in infants, lack of durable protection, and restricted coverage, highlight the need to explore innovative preventive strategies. Next-generation vaccines that provide comprehensive protection, sustained immunity, and cost-effectiveness are urgently required. Live attenuated vaccines (LAVs) represent a promising frontier in this effort, with recent advances focused on overcoming developmental and safety challenges. This review highlights the evolving pneumococcal vaccine landscape, with emphasis on LAV strategies. We summarize the strengths and shortcomings of current vaccines, examine recent advances in LAV development, including key aspects of attenuation, immune-protective mechanisms, and delivery approaches. LAVs demonstrate potential to induce balanced mucosal, humoral, and cellular immunity, addressing critical gaps left by existing platforms. Key challenges related to genetic stability, safety, and translational applicability are also discussed. By synthesizing established knowledge and highlighting advancements, this review underscores the promise of LAVs as next-generation candidates that can provide broader, longer-lasting protection against pneumococcal disease.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (Spn) remains a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality, responsible for both invasive and non-invasive diseases across diverse populations. While it is a frequent cause of community-acquired pneumonia, its capacity to trigger invasive sequelae like sepsis and meningitis drives its high fatality rates. This pathogenicity results in huge annual mortality figures, particularly in low-to middle-income countries where the burden of infection is exacerbated by limited access to vaccination and healthcare [1]. This high burden is complicated by the fact that Spn possesses over 100 known capsular serotypes, each expressing a structurally and antigenically distinct polysaccharide capsule [2]. While not all serotypes cause disease, the global diversity of pathogenic serotypes presents a major challenge for vaccine development, necessitating vaccines that can provide broad coverage.

In response to this burden, decades of research have culminated in the development of two major classes of vaccines that have reshaped pneumococcal prevention: pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines (PPVs) and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) [1, 3]. The PPV vaccine, licensed in the United States in 1983, includes 23 serotypes (namely serotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 19F, 20, 22F, 23F, and 33F) and is recommended for older adults (≥ 65 years) and individuals aged 2–65 with specific medical conditions [4]. PPVs elicit a T-cell-independent immune response, in which the repeating polysaccharide subunits directly stimulate B cells to produce serotype-specific IgG antibodies [4]. These antibodies enhance opsonization and complement activation, facilitating bacterial clearance, and in some cases provide cross-reactive protection against related serotypes with similar capsule structures [3].

Falkenhorst et al. [5] demonstrated that PPVs offer moderate protection against invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in adults aged 60 and above, with vaccine efficacy ranging from 45 to 73% across study designs. Similarly, Latifi-Navid et al. [6] confirmed PPV23’s effectiveness in reducing IPD incidence in randomized controlled trials. Their meta-analysis, which included observational studies, found no significant reduction in pneumococcal pneumonia or related mortality [7]. Nevertheless, subsequent evaluations have questioned the impact of PPV23 on non-invasive disease outcomes [8]. Public Health England reported an overall effectiveness of 24% [9], which declined from 48% within two years post-vaccination to only 15% after five years [10]. Protection dropped to as low as 5% in individuals aged 75 years and older [11]. This waning immunity reflects the T-cell-independent mechanism of PPVs, which elicits serotype-specific IgG responses without generating durable immunological memory [11–15]. Moreover, PPV23 has a limited impact on non-invasive pneumonia, remains costly and thus, inaccessible in many low- and middle-income countries [16, 17].

PCVs were engineered by covalently linking capsular polysaccharides (CPSs) to carrier proteins to address the suboptimal immunogenicity of pure polysaccharide vaccines in pediatric populations [18]. This chemical conjugation transforms the immune response from T-cell-independent to T-cell-dependent, enabling the generation of robust immunological memory and long-term protection [18, 19]. PCV7, licensed in 2000–2001 with seven serotypes (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, 23F), led to more than 70% decline in IPD among children under two years in the United States [20, 21] and an approximately 20% reduction in acute otitis media [22]. Unlike PPVs, PCVs elicit T-cell-dependent responses through polysaccharide-protein conjugation, which enables class switching, affinity maturation, and durable immunological memory [23, 24]. Subsequent expanded formulations PCV10 and PCV13, which include the addition of serotypes 1, 5, 7F, 3, 6A, and 19A [25], reduce nasopharyngeal colonization and induce herd immunity [26]. The selection of serotypes in PCV10 and PCV13 was guided not only by their disease burden but also by their association with antibiotic resistance [27]. Multiple studies have confirmed that these formulations are effective in reducing infections caused by drug-resistant pneumococcal strains [28].

More recently, PCV15 (Vaxneuvance, Merck) and PCV20 (Prevnar 20, Pfizer) extended the vaccine coverage to serotypes 22F, 33F, and seven additional serotypes [29–31], and showed promise in reducing non-invasive illnesses such as otitis media and pneumonia [32]. PCVs remain advantageous in infants [33] and have reduced vaccine-serotype disease in both vaccinated and unvaccinated populations. However, PCVs still cover only a subset of serotypes and face challenges, including serotype replacement through capsular switching [34], genetic recombination that drives resistance and virulence [35], and the indirect promotion of non-vaccine serotypes [36]. Beyond restricted serotype coverage, the production of polysaccharide-based conjugate vaccines presents significant technical and economic challenges [37]. Manufacturing requires costly containment for toxic bacteria, extensive purification steps that result in material losses, and yields heterogeneous products that may include free polysaccharides, which can impair immune responses [38]. The complexity of scaling up production while maintaining consistent vaccine characteristics further increases costs [39]. Consequently, the high manufacturing costs of multivalent PCVs remain a significant barrier to widespread adoption, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [40, 41].

Despite the substantial impact of PPVs and PCVs in reducing IPD, important limitations remain. Both vaccine classes depend on serotype-specific immunity, leaving populations vulnerable to non-vaccine strains and the phenomenon of serotype replacement [42]. The T-cell-independent response elicited by PPVs results in limited immunological memory and waning protection in older adults [9], while PCVs, though effective in infants and young children [10], cover only a subset of circulating serotypes and are associated with high production costs [38]. Moreover, neither vaccine type induces strong mucosal immunity, which is critical for preventing colonization and transmission [43].

Given the limitations of existing pneumococcal vaccine platforms, live attenuated vaccines (LAVs) have emerged as a promising alternative, offering the potential to elicit both systemic and mucosal immune responses, broaden serotype coverage, and thereby reduce the costs of manufacturing. This review aims to synthesize and critically evaluate current evidence on LAVs, highlighting their distinctive immunological advantages, strategies for enhancing safety and genomic stability, and progress toward clinical translation while outlining the challenges and opportunities that will shape their future development.

Pneumococcal vaccine guidelines continue to evolve in response to emerging serotypes, variable effectiveness, and the need to optimize protection across age groups and risk populations. For older adults, immunization strategies have shifted from a primary reliance on PPSV23 to a more integrated framework following the introduction of PCV13 for pediatric and subsequently adult use [40, 41]. In 2014, the Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices (ACIP) recommended sequential administration of PCV13 and PPSV23 for adults aged ≥ 65 years [42], with dosing intervals refined in 2015 to optimize immunogenicity [43]. The widespread success of pediatric PCV13 programs generated substantial indirect protection for older adults, leading ACIP in 2019 to conclude that routine PCV13 offered only marginal additional benefit for most healthy seniors [44]. Consequently, current guidelines emphasize ‘shared clinical decision-making’, reserving PCV13 primarily for high-risk cohorts rather than the general population aged ≥ 65 years [44]. This policy shift is further supported by immunological evidence linking vaccine-induced antibody concentrations to protection against pneumococcal colonization [45].

Several supplementary factors complicate the interpretation and application of pneumococcal vaccination recommendations. Firstly, the prevalence of pneumococcal disease varies regionally due to differences in surveillance, epidemiology, and PCV implementation, hindering direct geographical comparisons [46]. Secondly, the prevalence of risk factors for IPD, such as smoking, HIV infection, and other comorbidities, also exhibits regional variation, influencing susceptibility to the disease [47]. Additionally, the extent of herd protection and the remaining disease burden can differ significantly across regions. For instance, a cost-effectiveness analysis in South Africa favoured PCV13 over PPV23 for adult immunization in both public and private sectors, including individuals with HIV [48]. Moreover, herd protection remains incomplete in some European countries and South Africa, potentially allowing specific serotypes to cause infections in older children and adults even with existing vaccination programs [49, 50].

Pelton et al. [51] demonstrated that comorbidities and advanced age diminish the effectiveness of childhood PCV in older US adults, underscoring the need for updated adult recommendations with PCV15 and PCV20. Debate persists over whether adult vaccination should rely primarily on herd immunity from childhood programs or incorporate newer conjugate vaccines directly [52–55]. Additionally, key considerations in this debate include the persistence of vaccine-type diseases and the growing challenge posed by emerging non-vaccine serotypes [52, 53]. The residual disease burden and the degree of herd protection also vary across regions [46]; while serotype replacement is a notable concern in Europe and other parts of the world, it is not currently regarded as a significant issue in the United States [56]. Additionally, environmental factors play a significant role in shaping vaccine responses and influencing the overall burden of pneumococcal disease [56].

These challenges underscore the importance of robust surveillance and the exploration of serotype-independent strategies. Novel approaches based on conserved pneumococcal protein antigens [57–61] and LAVs [60–62] represent pivotal research directions, aiming to deliver broad and durable protection across diverse populations.

LAVs elicit stronger and more durable immune responses than conventional formulations. Early pneumococcal LAV candidates have shown the ability to reduce colonization and protect against lethal challenges across serotypes [63]. These genetically modified strains, rendered safe by deletion of pathogenic genes, provide broader antigen exposure and superior mucosal immunity compared to standard polysaccharide or conjugate vaccines [64]. To facilitate direct comparison across studies, Table 1 summarizes the attenuation strategies, protection outcomes, preclinical findings, and limitations with recommendations.

Pneumococcal live attenuated vaccine candidates: a comprehensive overview of attenuation strategies, animal models, protection, key findings, limitations, and recommendations.

| Attenuation strategy/Strain background | Animal model and immunization | Protection | Key findings | Limitations and recommendations | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single and combined mutations of the Δply, ΔpspA, and ΔpspC (cbpA) genes (serotype 2). |

| Reduced colonization in single and double mutants; triple mutant comparable to WT. | The single pspA knockout showed distinct effects compared with pspC and ply knockouts. | The pspA mutant is partially attenuated, retaining the ability to colonize and cause lung infection/bacteremia. Further studies are needed to clarify how pneumococcal virulence proteins contribute to colonization and systemic disease. | Ogunniyi et al., 2007 [65] |

| Targeted mutations in pspA, ply, and the cps locus (D39, type 4, 6A). |

| The cps mutant conferred independence for mucosal and systemic protection; the ply/pspA double mutant and pspA single mutant showed considerable attenuation, while the ply single mutant maintained virulence. | A two-dose regimen of combined cps and ply mutations is as effective as a single cps mutation, eliciting a strong immune response efficiently. | Cross-protection remains limited, and incomplete attenuation for ply/pspA. A combination of more than one attenuating mutation provides better safety and broad immunity. | Roche et al., 2007 [63] |

| Δpep27 gene mediates both LytA-dependent and LytA-independent lysis (lyt) (D39, type 4, type 6). |

| The Δpep27 gene protects against heterologous strains. | Induced antibody production and resistance to lethal challenge comparable to the cps mutant; unable to colonize the lungs, blood, and brain, prevented systemic disease. | The erythromycin resistance gene found in the pep27 mutant may be transferred to other commensal microbes in the nasopharynx. Further investigation is required to confirm the long-term safety and persistence. | Kim et al., 2012 [71] |

| Δpep27 without markers (D39). |

| Antisera cross-reactive; increased IgG titers; protected against lethal challenge; provided adequate protection. | Rapidly cleared colonization in vivo; cross-reactive with other serotypes; elicited mucosal immunity; shows inexpensive vaccine potential. | Inactivated THpep27 did not increase IgG or IgA; protection appears to be primarily cell-mediated and requires further clarification of immune mechanisms. | Choi et al., 2013 [73] |

| ΔHtrA protein (WT D39, WT TIGR4, D39 htrA–/htrA+). |

| The HtrA mutant retained its ability to colonize the nasopharynx, and this colonization significantly prolonged the survival of mice in a systemic bacteremia model. | Mutant colonization induced mucosal immunity and a strong humoral response, characterized by higher IgG titers, supporting the nasal route as a promising vaccination strategy. | The effectiveness and safety in humans remain uncertain; further studies are needed to investigate long-term immune persistence. | Ibrahim et al., 2013 [77] |

| ΔftsY and caxP genes [TIGR4 (serotype 4), D39, BHN54 (serotype 7F), ST191 (serotype 6A), BHN97 (serotype 19F)]. |

| The live vaccine candidate provided robust, serotype-independent protection against AOM, sinusitis, bacteremia, and pneumonia, including co-infection. | ftsY- and caxP- highlighted features of an optimal mucosal vaccine; BHN97ΔftsY showed prolonged colonization, higher pneumococcal-specific antibody titers, and a CD4+ T-cell-dependent isotype response. | Mucosal IgA levels were not assessed; further studies are required before human trials, including the deletion of the competence system to prevent recombination and reversion, as well as the evaluation of additional safety issues. | Neef et al., 2011 [68]; Rosch et al., 2008 [69]; Rosch et al., 2014 [70] |

| ΔSPY1 (erm cassette replacement) with deletion ply, teichoic acids, and capsule [SPY1 (WT D39), TIGR4, R6, 6B, 19F, 14, and 3]. |

| SPY1 long-term study showed i.n. immunization with 107 CFU D39 remained protective after three months, inducing both mucosal and systemic protection through antibody and cell-mediated immune responses. | SPY1 exhibited a stable capsular phenotype resulting from a cps locus mutation; mucosal and systemic immunization elicited antibody and cell-mediated protection, supporting it as a pneumococcal vaccine candidate. The adjuvants enhanced responses except with heat-inactivated SPY1. | SPY1 safety is supported by impaired reversion via phosphocholine-dependent competence. While heat-inactivated SPY1 conferred reduced protection, likely due to lower IgG and the absence of IgA titers. | Wu et al., 2014 [82] |

| A double mutant (Δpep27ΔcomD) (D39 and 6B). |

| Δpep27ΔcomD immunization provided long-lasting protection (up to 2 months) against type 2 and non-typeable NCC1 strains; the mutant eliminated transformability while maintaining protective efficacy. | Modified Δpep27ΔcomD strain persisted across infection routes; protection was associated with elevated IgG and reduced bacterial load; considered a feasible, cost-effective mucosal vaccine candidate. | A double mutant is unable to provide long-term protection against the type 6B strain only. Human trials are needed to assess efficacy changes in the challenge strain and its competition with nasopharyngeal commensals. | Kim et al., 2019 [72] |

| Δlgt gene [serotype TIGR4, ST2 (D39), ST3 (wu2), ST6B, ST9V, ST19F, and ST23F]. |

| Prolonged TIGR4Δlgt colonization promoted a Th1-biased response with the live vaccine, which conferred superior protection over the killed parental strain. | TIGR4Δlgt colonization induced robust mucosal and systemic immunity with IgG2b and Th1 dominance, cross-reactive across serotypes; strain safely colonized without significant inflammation or systemic spread, even at > 1,000× parental LD50. | Further studies are needed to clarify how lipoprotein-deficient pneumococci influence Th1-mediated host defense. | Jang et al., 2019 [88] |

| Serotype one strain (519/43) with recombinant new DNA into its genome [serotype 1, (519/43)]. |

| Haemolytic pneumolysin of strain 519/43 contributed to invasive disease; the Δply mutant of strain 519/43 showed reduced early bacteraemia and significantly lower blood bacterial loads. | Genetic modification of this serotype required a strain-specific, plasmid-based method. The pneumolysin D380N mutation did not increase red blood cell lysis; the strain maintained growth in lab media but exhibited impaired growth in serum compared to the WT. | Reduced early bacteraemia but did not prevent invasive disease due to Δply and WT strains showed similar burden; non-haemolytic pneumolysin did not abolish invasive potential of serotype 1 Spn; strain 519/43 disease capacity appeared independent of haemolytic activity; further studies are needed to clarify pneumolysin’s role in invasion. | Terra et al., 2020 [90] |

| Gene knockouts: endA and cpsE (D39). |

| SPEC strain immunization conferred the highest protection, with the most incredible survival rate and duration after lethal challenge, showing a 23-fold reduction in virulence compared to the WT. | cpsE knockout (SPC) reduced growth, colonization density, and duration but increased biofilm formation, while endA knockout (SPE) showed no effect on biofilm or growth, yet elicited the highest anti-pneumococcal IgG levels in mice; double knock-out (SPEC) gave better protection. | SPE strain elicited the highest anti-pneumococcal IgG but did not improve survival, indicating IgG alone is insufficient for protection. The single attenuation may reduce immunogenicity. The study lacked a heterologous challenge, and future work should compare immune responses with heat-inactivated bacteria and existing vaccines as well. | Amonov et al., 2020 [91] |

| Δcps/psaA: ΔpsaA gene; Δcps/proABC: ΔproABC gene (6B from clinical Spn isolate). |

| Induced sufficient anti-protein antibodies to protect and prevent septicemia after pneumonia rechallenge. | Induced sufficient antiprotein antibodies to prevent septicemia after pneumonia rechallenge. | Mutant strains elicited weaker serological responses than WT but were rapidly cleared, indicating high attenuation. The immune assessment was limited to a few antigens, with no CD4+ data or heterologous challenge, suggesting that CPS locus targeting alone may be insufficient for broad-spectrum vaccine design. | Ramos-Sevillano et al., 2021 [92] |

| The SpnA1 (Δfhs/piaA) and SpnA3 (ΔproABC/piaA) (Serotype 6B). |

| Clinical trial ISRCTN22467293: SpnA1 and SpnA3 conferred partial protection against recolonization (30% and 50% vs. 47% control) with protection assessed at 6 months by WT Spn challenge. | SpnA1 and SpnA3 live attenuated nasal vaccines were safe. The nasal IgG levels were similar across groups, while serum IgG was higher in SpnWT and SpnA1 than in SpnA3. | The study did not assess protection against heterologous strains or efficacy in vulnerable populations; a two-dose regimen poses a practical limitation. However, SpnA1 safety requires additional mutation to prevent reversion to virulence. | Hill et al., 2023 [94] |

The attenuation strategy for live attenuated vaccines, based on their major route of immunization, is whether it is intranasal (i.n.), intraperitoneal (i.p.), or intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection. Spn: Streptococcus pneumoniae; WT: wild-type; CFU: colony-forming unit; PBS: phosphate buffered saline; cps: capsular; ply: pneumolysin; pspA: pneumococcal surface protein A; pspC or cbpA: pneumococcal surface protein C; pep27: LytA-dependent and LytA-independent lysis; lyt: lipoprotein diacylglycerol transferase; HtrA: high-temperature requirement A protein; ftsY: disrupts nutrient uptake; caxP: proper protein delivery and hindering bacterial colonization; comD: protein essential for competence activation; endA: endonuclease A; cpsE: capsule synthesis gene; psaA: manganese uptake gene; proABC: proline biosynthesis gene; piaA: iron transporter required for systemic virulence; fhs/piaA: mutations affecting metabolic functions; AOM: acute otitis media; CPS: capsular polysaccharide.

An early effort by Ogunniyi et al. [65] examined the colonization and attenuation of ply, pspA, and pspC with single, double, and triple knockout variants. The colonization ability of single and double mutations was lower compared to the wild-type strain. However, the triple mutations exhibited colonization potential similar to the wild-type strain. According to Ogunniyi et al. [65], the pspA knockout showed significant differences from the pspC and ply knockouts in single knockouts and provides a compelling rationale for further enhancing the current reservoir of information about the involvement of characterized pneumococcal virulence proteins in both colonization and systemic disease produced by Spn. Additionally, the authors emphasized that the critical complexity of the dynamics of these processes requires further investigation. Regardless of the mutated genes, it appears that the colonization potential of the mutants remained variable [65].

A subsequent in-depth study was conducted by Roche et al. [63], who created Spn mutants lacking the CPS and/or key virulence factors Ply and PspA. The authors generated mutants significantly attenuated for disease transmission but capable of colonizing sufficiently to produce protective immunity by eliminating these determinants alone or in combination, as previously identified pneumococcal virulence factors [66, 67]. Their findings revealed that single mutants varied in attenuation, and combining deletions of virulence factors proved more promising. Interestingly, colonization density tests showed that while capsule-deficient and wild-type strains initially had lower colonization, mutants in the ply and pspA genes showed increased colonization later. Crucially, double mutants lacking CPS and Ply, or Ply and PspA, induced significant mucosal and systemic protection against the same and different pneumococcal strains. However, the protection also depended on both antibodies and CD4+ T cells, highlighting the potential of these rationally attenuated strains to elicit a comprehensive immune response [63].

Knocking out the caxP gene (encoding a calcium/magnesium transporter) and the ftsY gene (involved in protein transport) disrupts nutrient uptake and proper protein delivery, hindering bacterial colonization and invasive illness [68, 69], resulting in similar levels of attenuation but differing colonization capacities across serotypes. Rosch et al. [70] found that ftsY mutants exhibited prolonged colonization in the upper nasopharynx and enhanced expression of cbpA and pspA, while caxP mutants were rapidly cleared and did not cause invasive disease. Notably, the ftsY mutant demonstrated superior protection against otitis media and sinusitis in mice compared to heat-killed whole-cell pneumococci, highlighting that even with prolonged colonization, specific attenuating mutations can still elicit a strong protective immune response [70].

Kim et al. [71] established the role of pneumococcal LytA in autolysis and identified Pep27 as a LytA-dependent inducer of this autolysis process. The Spn pep27 knockout mutant conferred protection against lethal pneumococcal challenge in mice, suggesting a potential comparable to CPS mutants in antibody production and resistance. However, Kim et al. [71] noted a key difference: the pep27 mutant’s rapid clearance from the nasopharynx, potentially due to its propensity for aggregation, which hinders mucus survival and may contribute to its lower virulence. Further work demonstrated the pep27 mutant’s inability to adhere to or colonize key organs. Intranasal immunization without adjuvant provided long-lasting protection against heterologous strains, even preventing secondary colonization [72]. Nevertheless, the erythromycin resistance gene that was introduced in the pep27 mutant could be of concern as it may be passed to other commensal microbes in the nasopharynx through immunization [71].

Recognizing a safety concern with the erythromycin resistance gene in their initial mutant, Choi et al. [73] developed a marker-free pep27 mutant. Their findings were similar to those previously reported by Kim et al. [71], confirming the inactivated pep27 mutant’s ability to protect against a lethal challenge and elicit cross-reactive antisera, highlighting its rapid clearance within 48 hours and the induction of adjuvant-independent mucosal immunity. Additionally, vaccination against secondary pneumococcal infections was conferred by the pep27 mutant pneumococcus (designated Δpep27) [71], providing compelling evidence for the efficacy of the mutant as a potentially safe and effective mucosal vaccine strategy, with the marker-free approach used by Choi et al. [73] directly addressing a key safety hurdle for potential clinical translation.

Building upon their previous research, Kim et al. [71] refined their Δpep27 live attenuated pneumococcal vaccine candidate by deleting the comD gene to prevent reversion to virulence [72]. This double mutant (designated Δpep27ΔcomD) enhanced safety in healthy and immunocompromised mice while eliciting significant IgG responses against Spn serotype D39 and PspA-specific antibodies [71, 72, 74]. Immunization with this double mutant provided substantial protection (> 80% survival) against challenge with serotypes D39 and 6B, though sustained protection against the 6B strain remained limited [71, 72, 74]. The study suggests the Δpep27ΔcomD strain holds promise as a safe and effective pneumococcal vaccine, warranting further investigation into its efficacy against type 6B in humans and the impact of the host environment and nasopharyngeal microbiota on challenge strain dynamics [75, 76]. The robust long-term immunity offered by current commercial vaccines underscores the potential value of this double-mutant approach if these limitations can be addressed.

Ibrahim et al. [77] investigated the potential of a live-attenuated Spn strain deficient in the HtrA as a vaccine candidate. Deleting the htrA gene, which is essential for bacterial survival under environmental stresses such as oxidative stress and high temperatures [78–81], resulted in a significantly attenuated mutant. The rationale was that this attenuated strain, capable of nasopharyngeal colonization, could induce protective immunity. Indeed, intranasal immunization with the htrA-deficient strain elicited enhanced specific humoral immune responses at both systemic and mucosal levels [75]. Furthermore, immunized mice exhibited substantial protection against nasopharyngeal colonization and challenge with multiple pneumococcal strains at both mucosal and systemic sites [77, 81], highlighting the potential of targeting stress response pathways for live attenuation and offering a strategy to induce broad protection by leveraging mucosal immunity.

Another live attenuated pneumococcal vaccine development strategy involves deleting genes encoding essential proteins. Wu et al. [82] created the capsule-negative Spn strain SPY1 by deleting the SPD_1672 gene, which rendered defects in three key virulence factors: the capsule, teichoic acids, and pneumolysin [83]. Intranasal immunization with SPY1 protected mice against colonization and lethal challenge [82, 84]. Subsequent research demonstrated that mucosal and systemic immunization with SPY1 elicited protective humoral and cellular responses, highlighting its potential as a candidate vaccine [81]. SPY1 induced detectable cytokine levels in mice, including IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-10, and IL-4, but the specific roles of different CD4+ T cell subtypes in SPY1-mediated protection remained under investigation [85, 86]. This approach of targeting essential genes for attenuation, exemplified by SPY1, offers a promising avenue for developing LAVs that elicit broad protective immunity.

Xu et al. [87] further elucidated the protective mechanisms elicited by the SPY1 candidate LAV using an immunodeficient mouse model. Their findings revealed a collaborative role between T-cell and humoral immunity in mediating vaccine-specific protection. Specifically, protection against lethal pneumococcal challenge and colonization was attributed to Th2 immunological subsets and Th17-mediated phagocyte recruitment. Experiments in B-cell-deficient mice demonstrated the necessity of antibody-mediated immunity for the protective effects afforded by SPY1. Furthermore, studies in T cell-deficient mice highlighted the crucial role of T cell-mediated immunity, particularly the IL-17 response, in protecting SPY1-vaccinated mice [87]. The vaccine-specific Th17 cells facilitated neutrophil recruitment and activation against colonization, indicating that a Th2 response was required for protection against a lethal challenge. Notably, T regulatory (Treg) cells were found to counteract both pneumococcal colonization and lethal challenge. Consequently, Xu et al. [87] emphasized the importance of designing novel pneumococcal vaccines that can induce protective Treg cell responses, as strong Th1 or Th17 responses without Treg cell balance could lead to detrimental pathological consequences during both disease and colonization.

Jang et al. [88] adopted a different live attenuation strategy by deleting the lgt gene, responsible for lipoprotein synthesis, in the Spn strain TIGR4, which is crucial for various bacterial processes, including virulence and immune evasion. The TIGR4Δlgt mutant exhibited reduced virulence and inflammatory activity. Nasopharyngeal colonization with this strain in mice elicited robust mucosal IgA and systemic IgG2b-dominant antibody responses that showed cross-reactivity against other pneumococcal serotypes. Intranasal immunization with TIGR4Δlgt conferred protection against pneumococcal infection and challenge with heterologous strains. This immunogenicity profile suggests that targeting lipoprotein synthesis for live attenuation can generate a broad-spectrum pneumococcal vaccine candidate by inducing cross-reactive immunity.

Recent surveillance highlights Spn serotype 1 as a significant cause of invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa, despite its infrequent presence in asymptomatic individuals [89]. Terra et al. [90] engineered a serotype 1 strain (519/43Δply) with a specific mutation inactivating the ply gene, thereby abolishing its haemolytic activity. While intraperitoneal immunization of mice with this mutant reduced bacterial load in the bloodstream following challenge, it did not confer complete protection against pneumonia, suggesting that the ply gene in this serotype 1 strain may be a virulence factor with limited impact. The authors advocate for continued research to better understand the transformability of various serotype 1 strains, enabling the targeted genetic manipulation of relevant genes [90].

Our research group engineered a live attenuated pneumococcal vaccine candidate by creating a double mutant of Spn serotype 2 (strain D39) lacking genes for cpsE and endA. Mutation of cpsE is known to abolish capsule formation, reduce virulence, and enhance host immune responses [91]. Deletion of endA, strongly associated with natural transformation, aimed to minimize the risk of cpsE gene reintegration and capsule restoration [91]. Immunization of mice with this ΔcpsEΔendA double mutant resulted in a 56% survival rate following intranasal challenge, comparable to the 50% survival observed in mice challenged with the wild-type strain. Furthermore, mice immunized with the double mutant showed higher serum levels of D39-specific IgG and IgM antibodies than those exposed to the wild-type [91]. This dual-gene deletion strategy demonstrates a promising approach for live attenuation by combining reduced virulence and enhanced immunogenicity with a potential safety mechanism against reversion.

In another study, Ramos-Sevillano et al. [92] investigated the protective effects of nasal colonization in mice using two Spn serotype 6B mutant strains with disrupted cps genes, consistent with previous findings. Importantly, each strain also carried an additional mutation in either pspA or proABC, both of which are established pneumococcal virulence factors. Following a two-dose intranasal colonization regimen, the mice developed increased serum IgG antibodies against Spn antigens at lower levels than those observed in wild-type mice. While this colonization provided resistance against septicaemia, it failed to prevent subsequent recolonization by the wild-type strain [92, 93]. This study highlights the potential of using cps-deficient mutants to induce systemic protection. However, it suggests that additional modifications or strategies may be needed to achieve robust and persistent protection against colonization.

Building upon the promising safety and immunogenicity profiles demonstrated in numerous preclinical models, the development of pneumococcal LAVs has recently achieved a significant milestone. The first randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted by Hill et al. [94] in response to the discrepancy in their previous preclinical data, as reported by Ramos-Sevillano et al. [92]. Earlier research demonstrated that two double-mutant Spn strains (ΔproABC/piaA and Δfhs/piaA), which had mutations affecting virulence-related metabolic functions, were suitable vaccine candidates. In a mouse model, these strains induced significant protective immunity against subsequent colonization, pneumonia, and sepsis from the homologous wild-type strain [93]. Hill et al. [94] reported that 148 participants were randomly assigned to receive nasal inoculation of either wild-type Spn 6B (BHN418 strain, SpnWT), one of two specific double mutant attenuated strains [SpnA1 (Δfhs/piaA) or SpnA3 (ΔproABC/piaA)], and immune responses were monitored through regular nasal wash and blood sample collection. The Experimental Human Pneumococcal Challenge (EHPC) model was used to test whether the nasopharyngeal administration of the Spn6B Δfhs/piaA or Spn6B ΔproABC/piaA strain could prevent subsequent recolonization with wild-type Spn [94].

Collectively, these studies highlight the potential of LAVs in eliciting broad and durable immune responses, encompassing both systemic and mucosal protection. Preclinical work has provided valuable insights into genetic attenuation strategies and their immunological effects, though comparisons with established conjugate vaccines in real-world settings remain limited. The evidence highlights the need to refine attenuation approaches to ensure safety, stability, and broad-spectrum coverage. Building on this summary, the following section examines specific strategies deemed most promising, explaining why prior approaches introduced by different researchers are sensible and hold strong scientific potential.

Recent research has highlighted several promising approaches that not only enhance immunogenicity but also address critical concerns regarding immune-protective mechanisms induced by LAV, genetic stability, safety, and clinical applicability. These strategies include rational attenuation through multi-gene deletion or irreversible genomic modifications, optimization of immune-protective mechanisms to achieve broad-spectrum and durable responses, and careful evaluation of delivery routes and safety profiles in early human trials. Together, these advances provide a framework for developing next-generation LAVs, and the following subsections discuss each strategy in detail, supported by relevant scientific evidence from previous studies.

A comprehensive evaluation of pneumococcal LAVs has revealed several promising strategies, particularly aimed at managing the challenge posed by the inherent genetic adaptability of Spn, driven by natural competence and genomic flexibility. These traits pose a significant risk that rapid recombination could lead to vaccine strains reverting to virulence if not effectively controlled [66]. To mitigate this, technical approaches such as multiple gene deletions and irreversible genome editing are essential for generating stable, non-reverting strains. A key example is the Δpep27ΔcomD platform. The initial Δpep27 mutation conferred broad protection, as demonstrated by Kim et al. [71] and Seon et al. [74]. To ensure the strain was non-transformable, the comD competence gene was strategically excised [72]. This dual-target approach prevents the re-acquisition of virulence factors from wild-type strains via horizontal gene transfer, providing a critical safety mechanism against reversion in clinical and environmental settings [71, 72, 74]. In addition, targeting core metabolic functions has proven effective, as demonstrated by Jang et al. [88], who developed a stable LAV by deleting the lgt gene, thereby disrupting a pathway essential for survival and virulence. Similarly, Amonov et al. [91] proposed a universal vaccine strategy targeting endA, a gene strongly linked to transformation ability [95, 96]. Collectively, these approaches demonstrate that interference with key virulence proteins, coupled with irreversible attenuation, can diminish pathogenicity while crucially retaining immunogenicity [97–99].

In addition to ensuring genetic stability, promising LAV strategies must be evaluated for their ability to orchestrate protective immunity. Comparative evidence demonstrates that distinct mutant strains activate mucosal, cellular, and humoral pathways in different ways, making immune mechanisms a critical dimension of their promise. The fundamental advantage of LAVs lies in their ability to mimic natural infection, thereby sustaining antigen exposure and activating a broader range of functional immune responses. Evidence from murine and human studies indicates that even short-term colonization can induce comprehensive immunity, including mucosal IgA and systemic antibodies, which prevent the re-colonization of the nasopharynx and reduce the risk of invasive diseases, such as pneumonia and sepsis [99, 100].

Unlike polysaccharide or protein-based vaccines that primarily elicit systemic antibody responses, LAVs induce both mucosal and serum antibodies. Nasal delivery targets explicitly the primary colonization site, leading to the production of secretory IgA, a crucial component in blocking colonization and achieving serotype-independent protection [75]. Human data from Hill et al. [94] confirmed that LAVs elicit broad nasal and serum responses, including antibodies against diverse protein antigens. Double-mutant gene strategies further enhance this breadth, as reported by Kim et al. [72] and Ramos-Sevillano et al. [93], where antibodies against multiple pneumococcal proteins conferred extensive protection. Ibrahim et al. [77] demonstrated that deletion of the htrA gene produced a highly attenuated strain that retained colonization capacity, elicited strong systemic and mucosal antibody responses, and protected mice against multiple pneumococcal strains. Similarly, Wu et al. [82] developed the capsule-negative SPY1, which not only protects against colonization and lethal challenge but also elicits humoral responses at both mucosal and systemic levels [83, 84].

Transient replication of LAVs at mucosal surfaces stimulates robust T-cell responses, which are often absent in polysaccharide-based vaccines. They induce Th17 cells that produce IL-17 to recruit neutrophils for bacterial clearance, while Treg cells maintain immune homeostasis to prevent excessive inflammation. This coordinated balance distinguishes LAVs from subunit vaccines, which rarely achieve both effective Th17 activation and regulatory control [101, 102]. Attenuation strategies directly shape these responses by deleting metabolic or virulence genes that modulate inflammatory signals, producing strong protective immunity without pathological inflammation. Similarly, Xu et al. [87] further clarified the mechanisms of SPY1, demonstrating that protection against lethal challenge and colonization required both humoral and cellular immunity. Specifically, Th2 subsets mediated antibody-dependent protection against lethal disease, while Th17 cells recruited neutrophils to clear colonization. Importantly, Treg cells were found to counteract pneumococcal colonization and lethal challenge, underscoring the importance of balanced regulation in preventing pathological consequences.

Beyond direct immune activation, LAVs interact at their primary entry point with the nasopharyngeal microbiota [101] to enhance long-lasting immunity. This ecological interplay has been shown to strengthen mucosal memory responses and broaden protection [76]. Such mechanisms are absent in non-replicating vaccines, underscoring the comparative advantage of LAVs in preclinical models. Together, these findings demonstrate that LAVs uniquely integrate humoral, mucosal, and cellular immunity, with different mutant strains orchestrating distinct protective mechanisms. To further illustrate these findings, Table 2 systematically compares how different live attenuated mutant strains and conventional vaccine platforms orchestrate mucosal, humoral, and cellular immunity.

Comparative immune protection by LAVs and conventional vaccines.

| Immune component | LAVs | Polysaccharide vaccines | Protein/Subunit vaccines | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mucosal immunity | Secretory IgA induction via nasal colonization, for example, with a ΔhtrA strain, elicited potent mucosal antibodies and blocked recolonization. SPY1 induced mucosal IgA and protected against colonization. | Minimal mucosal response; poor induction of IgA at colonization sites. | Limited mucosal activation; mainly systemic antibody responses. | [77, 81, 82, 84] |

| Humoral immunity | Broad antibody repertoire against capsular and protein antigens. ΔhtrA induced systemic antibodies with cross-strain protection. SPY1 elicited systemic antibodies and cytokine responses (IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-10, IL-4). Double-mutant strains broaden protein antigen coverage. | Capsule-specific antibodies; narrow protection, serotype-dependent. | Protein-specific antibodies: moderate breadth but limited durability. | [74, 77, 82, 85, 86, 93] |

| Cellular immunity (Th17/Th2) | Strong IL-17 response recruits neutrophils for mucosal clearance. Δlgt and ΔendA mutants modulate inflammatory signals. SPY1 induced Th17-mediated phagocyte recruitment and Th2 subsets for protection against lethal challenge. | Weak T-cell activation; poor cellular memory. | Variable T-cell activation; depends on adjuvant use. | [87, 88, 91] |

| Regulatory balance (Treg) | Balanced immune regulation; Treg cells prevent excessive inflammation while maintaining clearance. | Minimal Treg modulation; risk of poor regulation. | Partial regulation; adjuvant-dependent. | [87] |

| Microbiota interaction | Enhances long-term immunity via ecological interplay with commensals. | No microbiota engagement. | Limited microbiota effects. | [76] |

LAVs: live attenuated vaccines; Treg: T regulatory.

Beyond general safety considerations, the successful clinical translation of LAVs requires stringent human safety data, particularly for novel mucosal delivery routes. A recent randomized controlled trial by Hill et al. [94] offered a vital initial human safety assessment for nasal administration of SpnA1 and SpnA3 in healthy adults. The study reported no serious adverse events and adhered to established Enhanced Human Participant Care safety guidelines. These guidelines involved rigorous volunteer screening to ensure good health, comprehensive participant training for early symptom identification and response (supplemented by a safety leaflet), continuous 24/7 clinical on-call support, and recording of adverse events according to protocol. This finding not only encourages but also significantly mitigates risk, reframing the safety challenge for further human trials.

Despite encouraging progress in pneumococcal LAV development, several interrelated challenges continue to constrain their translation into clinical practice. A critical synthesis of current evidence highlights five key domains that collectively define the future research agenda. First, safety profiles must be rigorously evaluated across diverse demographics to ensure tolerability and public confidence. Second, the variability in colonization outcomes and the absence of reliable immunological correlates of protection necessitate a deeper investigation into host and pathogen factors to better predict vaccine efficacy. Third, advancements in human challenge models offer opportunities to accelerate development; however, their inherent limitations, such as ethical considerations and the difficulty in mimicking natural disease progression, must be carefully addressed. Fourth, precision genome editing technologies like CRISPR provide novel attenuation strategies; yet, their potential is tempered by safety, regulatory, and ethical considerations. Finally, addressing concerns related to vaccine stability, manufacturing standards, and securing sustainable funding remains essential for ensuring the global feasibility and long-term implementation of pneumococcal LAVs. By critically assessing current evidence and highlighting these five priorities, this section provides a roadmap for advancing pneumococcal LAVs toward clinical reality.

Safety evaluation is a fundamental prerequisite in the development of pneumococcal LAVs, as regulatory approval and public acceptance depend on robust evidence of tolerability across diverse populations. Establishing a general safety profile provides the foundation upon which specific findings from initial studies can be interpreted. Initial studies in healthy adults, such as those reported by Hill et al. [94], have indicated a favourable safety profile for LAV candidates, with no serious adverse events. However, a critical requirement for vaccine licensure and widespread implementation is the comprehensive assessment of safety across varied demographics [102]. Future clinical trials must move beyond initial human challenge studies to rigorously demonstrate vaccine safety and efficacy in larger, more heterogeneous populations than the 148 participants in the previous report by Hill et al. [94]. Such extensive data are essential because vaccine responses and adverse event risks can vary significantly with age, comorbidities, genetic background, and nutritional status. This emphasis on diverse populations underscores the need for a holistic approach to safety evaluation, anticipating the complexities of real‑world application and ensuring that potential risks are adequately addressed.

In addition, the initial findings by Hill et al. [94] highlight the need to investigate whether nasal administration of attenuated Spn strains, such as SpnA1, can prevent colonization with heterologous Spn strains, particularly in participants with age‑related vulnerabilities or underlying comorbidities. Expanding beyond homologous challenge strains, such as serotype 6B, to evaluate cross‑protection against heterologous serotypes is essential not only for broad efficacy but also for ensuring that attenuation strategies do not compromise safety in high‑risk groups. This dual focus on broad protection and rigorous safety assessment demonstrates a commitment to maximizing public health impact while safeguarding vulnerable populations.

Understanding variability in colonization dynamics and the complexity of immune correlates is central to evaluating pneumococcal LAVs. Establishing protection requires not only consistent preclinical models but also reliable immunological predictors that capture the multifaceted nature of host responses. Amonov et al. [91] have identified a relevant concern regarding the variability observed in the length of host colonization across several vaccine experiments, proposing that this variability may be attributed to host-related factors, such as the specific strain of mice employed in these investigations, and to the use of distinct pneumococcal serotypes. For example, the BALB/c mouse strain is commonly employed for investigations related to immunity; however, it exhibits relatively higher resistance to mortality caused by Spn than CD1 and C57BL/6 mouse strains [103–105]. Therefore, when selecting an animal model’s genetic composition, it should be considered while investigating pneumococcal immunity to improve preclinical data.

Secondly, a persistent and critical challenge lies in definitively establishing precise correlates of protection in humans, which requires a comprehensive assessment that extends beyond traditional humoral responses, such as IgG antibody titers, to include multifaceted cellular (e.g., CD4+ T cell responses like Th17) and innate immune responses [106]. These diverse immune components are crucial for ensuring that the attenuated LAV strain effectively stimulates all arms of the immune system to generate robust, long-lasting protection [106, 107]. Unlike some conventional vaccines, where antibody titers can reliably predict protection, LAVs aim to mimic natural infection, which elicits a complex interplay of immune mechanisms at mucosal surfaces. Protection against colonization, a key goal for LAVs, involves intricate interactions between innate immune cells and adaptive T and B cell responses. A deeper understanding of these multifaceted cellular and innate responses is necessary to characterize the protective immunity induced by an LAV.

The successful execution of controlled human infection models (CHIMs), exemplified by the EHPC model highlighted in a recent 2023 randomized controlled trial, represents a critical advancement [94]. These models provide a crucial, ethically controlled environment for the early-stage assessment of LAV candidates, safety, immunogenicity, and initial protective efficacy, long before traditional field trials. The EHPC model has shown that it can safely colonize participants with attenuated Spn and provide protection against wild-type challenge. This approach accelerates the identification of promising vaccine candidates, offering a clear translational advantage over relying solely on preclinical animal studies. A notable example of this advancement is the feasibility study by Morton et al. [108] in 2021, which successfully transferred the Spn-CHIM to Malawi. Another SPN3 human challenge model, by Robinson et al. [109] in 2022, underscores the continuous evaluation and data crucial for broader implementation.

Expanding CHIMs into endemic regions represents a crucial step towards global health equity in vaccine development. It acknowledges that vaccine efficacy and host-pathogen dynamics can vary significantly across different epidemiological contexts and populations. Therefore, developing and testing the vaccines in the populations and environments where the disease burden is highest and where current strategies fall short is essential to demonstrate a commitment to developing context-specific and globally relevant vaccine solutions, moving beyond a “one-size-fits-all” approach.

Another key challenge in developing LAVs is achieving precise genetic manipulation while ensuring optimal safety. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology offers a significant advantage by enabling rational design of LAV candidates [110] with stable attenuation and targeted pathogenicity defects, while preserving robust immunogenicity. Precision genome editing with CRISPR/Cas systems has emerged as a promising attenuation strategy, bridging the gap between theoretical potential and practical application by providing unprecedented control over bacterial genomes [111–113]. In pneumococcal vaccine development, CRISPR/Cas enables the precise excision of virulence or replication-associated genes, providing a sophisticated and targeted approach to attenuation [114, 115].

Nevertheless, several challenges must be addressed before clinical translation. Off-target effects and unintended genetic alterations remain critical safety concerns, particularly for vaccines intended for widespread use. Regulatory frameworks for gene-edited organisms are still evolving, and ethical considerations regarding the release of genetically modified strains require careful evaluation [116]. In addition, the scalability and cost-effectiveness of CRISPR-based approaches must be demonstrated to ensure feasibility across diverse healthcare settings. Strengthening research on these cutting-edge technologies will be essential to balance innovation with safety, ultimately determining whether CRISPR-enabled attenuation strategies can complement or surpass traditional approaches in next-generation pneumococcal vaccines.

The transition from promising preclinical data to human clinical trials is fraught with significant translational hurdles. The stability and management of a candidate live vaccine must be considered in any potential further development. Culturing the bacteria is impractical due to the autolysis of pneumococcus upon entering the stationary phase, rendering it nonviable [117]. Besides, the establishment of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) for vaccine production and the successful navigation of complex regulatory requirements necessitate rigorous safety [102] and efficacy testing in animal models [118]. A substantial barrier to this process is securing adequate funding, as clinical trials, particularly those in Phase II and III, are expensive and time-consuming [119]. The financial bottleneck underscores a critical challenge, as economic realities and market dynamics continue to shape and constrain the trajectory of vaccine development. Overcoming this barrier requires scientific breakthroughs, strategic policy interventions, innovative funding models, and a clear articulation of the unique value proposition of LAVs.

In summary, the future of pneumococcal LAV development depends on addressing interconnected challenges that span safety evaluation, colonization variability, predictive immunology, human challenge models, precision genome editing, and translational feasibility. By critically synthesizing these domains, this review underscores that progress in one area alone will be insufficient; instead, coordinated advances across scientific, technological, and regulatory dimensions are required to achieve clinical translation.

The past two decades have firmly established the tantalizing promise of pneumococcal LAVs as a promising strategy to address the limitations of current vaccine options, offering the potential for improved efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Advances in attenuation methodologies, the identification of promising knockout mutants, and refined techniques for introducing multiple genetic modifications have significantly strengthened the scientific foundation for LAV development. Importantly, foundational preclinical work, now complemented by emerging clinical trial data, offers critical insights into the safety and efficacy of LAVs, signalling considerable progress in overcoming challenges related to attenuation safety, manufacturing, and the induction of broad immune protection. Despite this promising trajectory, significant challenges persist that must be actively addressed to ensure feasibility and scalability. These include optimizing manufacturing processes, securing sustainable funding, and refining predictive models of the immune response to guarantee consistent protection. On a primary impact level, ensuring robust safety across diverse populations and achieving durable, population-wide protection remain the pivotal hurdles that will ultimately determine the success of LAVs. The final realization of pneumococcal LAVs will depend on a collaborative and integrated effort among researchers, clinicians, industry partners, and key global health stakeholders. By overcoming these obstacles, LAVs are poised to play a crucial role in reducing the global burden of pneumococcal disease, providing effective and affordable protection, particularly in low-resource settings where current vaccine strategies are often insufficient.

ACIP: Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices

CHIMs: controlled human infection models

CPSs: capsular polysaccharides

CRISPR: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats

EHPC: Experimental Human Pneumococcal Challenge

IPD: invasive pneumococcal disease

LAVs: live attenuated vaccines

PCVs: pneumococcal conjugate vaccines

PPVs: pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines

Spn: Streptococcus pneumoniae

Treg: T regulatory

MY: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. CCY: Validation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. MA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—review & editing, Validation, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 833

Download: 25

Times Cited: 0

Imam Nurjaya ... Moh. Anfasa Giffari Makkaraka

Vijay Mishra ... Yachana Mishra