Affiliation:

1Interventional and Surgical Pain Management Unit, San Giovanni-Addolorata Hospital, 00184 Rome, Italy

Affiliation:

2Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Therapy, Sapienza University of Rome, 00185 Rome, Italy

Affiliation:

3Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences and Translational Medicine, Sapienza University of Rome, 00189 Rome, Italy

Email: matteolg.leoni@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5228-3733

Affiliation:

4Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Treatment, Università di Perugia, 06132 Perugia, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7760-9154

Affiliation:

1Interventional and Surgical Pain Management Unit, San Giovanni-Addolorata Hospital, 00184 Rome, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1356-1846

Affiliation:

5Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry, University of Salerno, 84081 Baronissi, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5236-3132

Affiliation:

6Fondazione Paolo Procacci, 00193 Rome, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3822-2923

Explor Immunol. 2026;6:1003235 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2026.1003235

Received: January 20, 2025 Accepted: December 19, 2025 Published: January 12, 2026

Academic Editor: Calogero Caruso, University of Palermo, Italy

Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) has emerged as a promising and versatile technology in pain management and immunological modulation. PRFʼs effects extend beyond pain modulation, demonstrating the ability to regulate inflammatory processes through cytokine modulation, reduction of microglial hyperactivity, and promotion of autophagy. These mechanisms position PRF as a potential therapeutic tool not only for neuropathic and musculoskeletal pain but also for conditions associated with neuroinflammation and immune dysfunction, including chronic inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Clinically, PRF has demonstrated potential in alleviating neuropathic pain in several clinical studies—including a limited number of small RCTs. However, most of the available evidence remains of low methodological quality, with many studies being observational, retrospective, or underpowered. Moreover, the lack of standardized protocols remains a barrier to its broader adoption. Establishing evidence-based guidelines and enhancing practitioner expertise are critical to ensuring consistent and optimal patient outcomes. Future research should focus on optimizing PRF technical parameters, elucidating molecular mechanisms, and expanding its clinical applications. Integrating PRF with emerging therapies, such as orthobiologics, biological drugs, and electrical stimulation, may further enhance its efficacy. Moreover, advancements in predictive biomarkers and device technologies hold promise for personalized treatments, improving the precision and effectiveness of PRF interventions. This narrative review explores the primary clinical applications, underlying biological mechanisms, and potential future directions of PRF, emphasizing its ability to address complex therapeutic challenges.

The management of chronic pain is one of the most significant challenges in modern medicine, as it involves physical, psychological, and social dimensions of patientsʼ lives [1]. Chronic pain arises from complex and overlapping mechanisms involving peripheral and central sensitization, neuroinflammation, and maladaptive neuroplasticity. Peripheral sensitization is triggered by tissue injury and inflammation, leading to increased excitability of nociceptors through mediators such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, and cytokines [2]. Central sensitization occurs when repeated nociceptive input amplifies synaptic transmission in the spinal dorsal horn, mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation, glial cell reactivity, and enhanced release of excitatory neurotransmitters [3]. Neuroimmune interactions further contribute to chronicity, with activated microglia and astrocytes releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines [interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)] that exacerbate neuronal hyperexcitability [4]. Moreover, descending pain modulatory systems—particularly serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways—may become dysfunctional, shifting from inhibition to facilitation of nociceptive transmission [5]. These mechanisms collectively explain why chronic pain persists beyond the resolution of initial tissue damage and highlight the rationale for exploring immunomodulatory approaches such as pulsed radiofrequency (PRF).

RF has emerged as a minimally invasive technology widely utilized across various therapeutic domains to manage pain through non-destructive neuromodulatory mechanisms. This technology relies on the emission of electromagnetic waves at specific frequencies, which modulate pain signal transmission along peripheral nerves or the spinal cord without causing permanent damage [6]. RF is applied across a broad range of pathological conditions. It is particularly effective in managing neuropathic pain, including postherpetic neuralgia, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), radicular pain, and chronic low back pain [7–10]. Additionally, it has been successfully employed in joint-related conditions, such as knee and hip osteoarthritis, to treat refractory joint pain [11]. Beyond musculoskeletal pain, RF has been explored for cancer pain management [12] and rarer conditions like trigeminal neuralgia [13], where it offers a valuable therapeutic option for patients unresponsive to conventional pharmacological treatments.

One of the most promising advancements is PRF, which differs from RF through its neuromodulative approach. Instead of reaching a temperature of 80°C, PRF delivers brief electrical impulses to modulate nerve circuits involved in pain transmission. PRF is defined by its delivery parameters, which include 20-millisecond bursts of 500 kHz RF energy administered at a frequency of 2 Hz [14]. A critical aspect of PRF is its temperature control, with a maximum threshold of 42°C, ensuring a non-destructive and neuromodulatory approach to the nervous tissue [15]. This technique has demonstrated prolonged analgesic effects while minimizing the risk of complications associated with RF [6, 14, 16]. Recently, it has been shown that PRF not only affects pain transmission but also influences underlying immunological mechanisms. In fact, both experimental and clinical studies have highlighted that PRF can modulate inflammatory responses by acting on cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10, as well as modulating the activity of microglia and macrophages [15, 17]. These immunomodulatory properties expand the potential applications of PRF beyond pain management to include conditions associated with chronic inflammation. In addition to cytokine and microglial regulation, hormonal and genetic factors also play an important role in shaping immune responses in chronic pain. Sex hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone modulate cytokine expression and glial reactivity, contributing to sex-specific immune phenotypes that influence susceptibility to pain chronification [18]. For instance, estrogen can enhance pro-inflammatory cytokine release and microglial activation, while testosterone exerts predominantly anti-inflammatory effects [4]. On the genetic side, polymorphisms in immune-related genes, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and COMT, have been associated with differential pain vulnerability and variable treatment responses [19]. These findings underscore the importance of considering both endocrine and genetic modulators when evaluating PRF’s immunological effects, as they may partially explain heterogeneity in clinical outcomes and could guide future patient stratification strategies.

The objective of this review was to explore in detail the role of PRF in modulating immunological processes. The mechanisms of action, major clinical applications, and future perspectives were analyzed, integrating current evidence with a critical view of emerging therapeutic opportunities.

The review was developed following the principles of the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) [20]. A comprehensive literature analysis was conducted using major scientific databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search targeted studies on the application of PRF in pain management, with a specific focus on its immunological effects. The search strategy included free-text terms and/or Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) associated with the following keywords: “radiofrequency”, “immune modulation”, “neuropathic pain”, “cytokines”, and “microglia”. Strict inclusion criteria were applied to select relevant studies. Articles were considered if they met the following criteria: (1) addressed the use of PRF in pain management, (2) explored the immunological mechanisms modulated by PRF, and (3) provided preclinical or clinical evidence related to cytokines, microglia, or other immunological components. The search was limited to English-language articles published up to January 2025. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance by two independent reviewers (FO, JM). Studies were excluded if they were: (1) conference abstracts without full text, (2) technical notes lacking clinical or immunological outcomes, (3) studies not involving PRF, or (4) non-peer-reviewed publications. The final selection included both preclinical studies investigating PRF’s immunological mechanisms and clinical studies assessing pain outcomes and inflammatory biomarkers. A narrative synthesis was chosen due to the heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and reported outcomes.

The initial bibliographic search identified a total of 126 articles. After removing duplicates, assessing titles and abstracts, and applying inclusion criteria, 37 articles were selected for full-text review. Among these, 12 studies [21–32] were identified as relevant to the topic and were included in the present narrative review. The selected articles comprised clinical studies, preclinical research, and reviews that collectively offer a broad perspective on the effects of PRF on the immune system (Table 1).

Studies investigating the immunological effects of PRF, along with key findings, emerged from these selected publications.

| Study | References | Study characteristics | PRF type | Summary of the evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sam et al., 2021 [21] | Narrative review | Low-voltage PRF | Modulation of immune activity and synaptic function |

| 2 | Vallejo et al., 2013 [22] | Experimental trial | PRF | Pain gene expression modulation |

| 3 | Yeh et al., 2015 [23] | Randomized trial | Immediate postoperative PRF administration | Reduction in allodynia via ERK inhibition |

| 4 | Cho et al., 2020 [24] | Animal model | Intra-articular PRF | Cartilage protection and pain reduction |

| 5 | De la Cruz et al., 2023 [25] | Systematic review | Low-voltage PRF | Neuromodulation mechanisms overview |

| 6 | de Moraes Ferreira Jorge et al., 2022 [26] | Review | Orthobiologic PRF | Synergy between PRF and orthobiologics |

| 7 | Sluijter et al., 2023 [27] | Exploratory study | PRF | Anti-inflammatory systemic effects |

| 8 | Liu et al., 2018 [28] | Controlled trial | DRG PRF | Reduced microglial activity and inflammation |

| 9 | Lin et al., 2021 [29] | Clinical evaluation | Lumbar PRF | MAPK activation and inflammatory pain |

| 10 | Chen et al., 2024 [30] | Experimental trial | High-voltage PRF | Enhanced autophagy, reduced neuroinflammation |

| 11 | Xu et al., 2024 [31] | Experimental trial | High-voltage PRF | GRK2 pathway modulation, reduced depression |

| 12 | Xu et al., 2019 [32] | Randomized trial | DRG PRF | Suppressed spinal microglial activity |

PRF: pulsed radiofrequency; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; DRG: dorsal root ganglia; GRK2: G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase.

PRF has proven to be a promising technology, offering significant potential not only for the treatment of chronic pain but also for regulating immune and inflammatory responses [22]. This effect, mediated by a series of molecular and cellular mechanisms, opens new perspectives for treating complex pathological conditions. One of the most studied effects of PRF is its ability to modulate the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Vallejo et al. [22] demonstrated that PRF was able to reverse mechanical allodynia within 24 h and modulate pain-related gene expression in the sciatic nerve, dorsal root ganglion (DRG), and spinal cord. Key findings included the normalization of pro-inflammatory markers such as TNF-α and IL-6 and the up-regulation of pain-modulatory genes such as GABAB-R1, Na/K ATPase, and 5-HT3r in the DRG. Moreover, Na/K ATPase and c-Fos were upregulated in the spinal cord following PRF therapy. Similarly, Yeh et al. [23] evaluated the analgesic effects of PRF applied immediately after nerve injury in a rat model of spared nerve injury (SNI). Rats treated with PRF at 45 V and 60 V showed significant reductions in mechanical and cold allodynia compared to untreated SNI rats, with effects lasting 28 days. Moreover, PRF was able to effectively inhibit the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) in the spinal dorsal horn, a critical intracellular kinase involved in the transmission of inflammatory signals. This inhibition attenuated central sensitization, a key driver of neuropathic pain chronicity. Liu et al. [28] demonstrated that PRF significantly reduced the expression of interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8), a key regulator of microglial activation and p38 hyperactivity, in the spinal cord of rats with chronic constriction injury (CCI), leading to a partial recovery of withdrawal thresholds lasting up to 14 days post-treatment. Peripheral nerve injury (PNI) induces IRF8 expression, which activates spinal microglia via the p38 pathway, contributing to central sensitization and neuropathic pain. This cited study highlighted the innovative role of PRF in influencing microglial autophagy. Furthermore, intrathecal administration of antisense oligodeoxynucleotide targeting IRF8 effectively reversed CCI-induced pain and spinal microglial hyperactivity. Importantly, PRF did not alter pain behaviors in normal rats, underscoring its selective effect in pathological conditions. These findings suggest that PRF provides long-lasting analgesia in CCI by modulating IRF8 expression, microglial activity, and the p38 pathway. Chen et al. [30] demonstrated in an SNI model that high-voltage PRF (HVPRF) stimulated autophagy in the dorsal column, facilitating the clearance of damaged cells and enhancing neuronal recovery. HVPRF alleviated SNI-induced pain, decreased ATF3 levels in the DRG, improved DRG ultrastructure, enhanced spinal microglial autophagy, and modulated neuroinflammation by reducing TNF-α and increasing IL-10 levels in the spinal cord. This dual mechanism of action, addressing both inflammation resolution and tissue regeneration, highlights PRFʼs potential as a versatile therapeutic tool for neuropathic pain management and tissue repair.

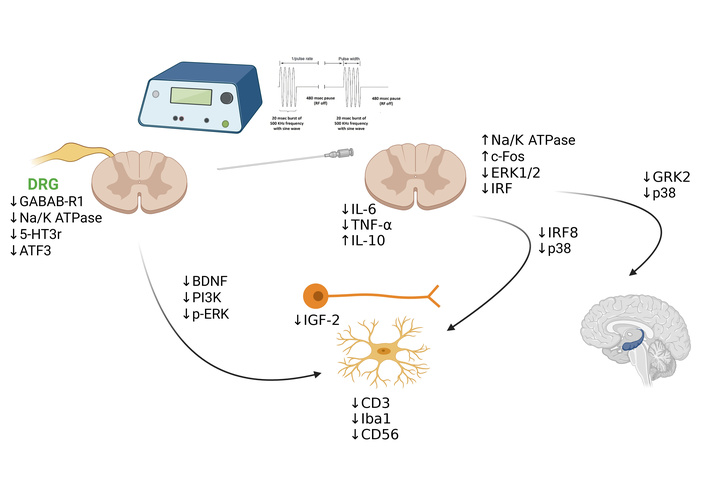

PRF also appears to impact the central immune system. Xu et al. [31] demonstrated that modulation of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2)/p38 signaling pathway in the dorsal column translates into reduced hippocampal inflammation, yielding benefits for both pain and associated depressive symptoms. This study underscores PRFʼs potential in treating complex comorbidities related to chronic pain, like depression [33], suggesting an integrative approach between neuromodulation and psycho-immunological interventions. While these results underscore the potential of PRF to reverse both behavioral and molecular changes associated with neuropathic pain, the study's limitations include a focus on short-term outcomes and the absence of protein expression analysis. In 2019, the same authors demonstrated that PRF applied to the DRG effectively alleviated neuropathic pain through the modulation of microglia, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) [32]. Using a SNI rat model, they showed that PRF treatment significantly reduced SNI-induced allodynia, decreased microglial hyperactivity, and downregulated the expression of BDNF, PI3K, and p-ERK in the spinal cord. These therapeutic effects persisted for 14 days following a single PRF application. Furthermore, intrathecal administration of minocycline, a microglial inhibitor, similarly reversed the elevation of these markers, underscoring the critical role of microglial modulation in achieving pain relief. From a broader systemic perspective, Sluijter et al. [27] proposed that PRF could act by modulating redox balance and reducing oxidative stress, which is recognized as an important factor in the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration [34]. The discovery of systemic anti-inflammatory effects of PRF began in 2013, when it was initially applied intravenously [35]. Subsequent findings revealed that PRF could also be delivered transcutaneously, leading to the hypothesis that very small magnetic fields generated by PRF might promote the recombination of radical pairs, contributing to its therapeutic effects [36]. Furthermore, it has become increasingly evident that epigenetic modifications in various immune-related cells play a crucial role in modulating inflammation [37]. This has led to the postulation that the PRF-induced cellular improvements are encoded in the epigenome, potentially explaining the prolonged periods of therapeutic benefit observed in clinical and experimental studies. Sam et al. [21] highlighted that PRF therapy influences immune activity by modulating key microglial markers (CD3, CD56, Iba1), inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-17, IRF8, IFN-γ, TNF-α), and intracellular proteins associated with immune-mediated neuropathic pain, such as BDNF, β-catenin, JNK, p38, and ERK1/2. In addition to these inflammatory factors, insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF-2), a gene involved in cellular proliferation, growth, and survival, has been linked to neuropathic pain. In neurons, IGF-2 is known to activate inflammatory pathways via ERK1/2 signaling. SNI models exhibited elevated IGF-2 levels compared to controls, while PRF treatment effectively normalized IGF-2 expression, alleviating neuropathic pain. Notably, PRF also inhibited ERK1/2 activation in this pathway, leading to a more pronounced reduction in allodynia in PRF-treated groups compared to controls [38]. The diverse mechanisms of action of PRF, including its neuromodulatory effects, immune modulation, and influence on inflammatory pathways, are comprehensively summarized in Figure 1.

PRF neuroimmune modulation. This figure provides an integrated overview of how PRF interacts with neural and immune systems, highlighting its ability to modulate cytokine levels, suppress microglial activation, and influence key signaling pathways such as PI3K and p-ERK. PRF: pulsed radiofrequency; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; p-ERK: phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase; IL: interleukin; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IGF-2: insulin-like growth factor 2; IRF: interferon regulatory factor; GRK2: G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Created in BioRender. Varrassi, G. (2026) https://BioRender.com/33tp3wv.

Among the molecular pathways implicated in chronic pain, autophagy has emerged as a critical regulator of neuroimmune homeostasis. Dysregulation of autophagy in neurons, glial cells, and immune cells can contribute to persistent neuroinflammation and maladaptive synaptic plasticity. In microglia, impaired autophagic flux promotes a sustained pro-inflammatory phenotype with increased release of cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, thereby amplifying pain sensitization [39, 40]. Similarly, in DRG neurons, defective autophagy disrupts mitochondrial quality control and increases reactive oxygen species production, both of which enhance nociceptor excitability [41]. Conversely, pharmacological or genetic enhancement of autophagy has been shown to suppress glial activation, reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine release, and attenuate pain behaviors in neuropathic pain models [42, 43]. These findings suggest that autophagy represents a potential therapeutic target, bridging immune regulation and neuronal plasticity in pain chronification.

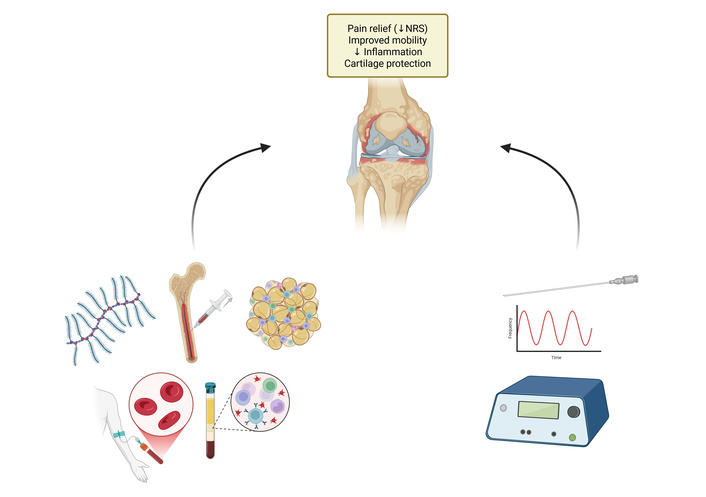

The integration of PRF with other therapies has been explored by de Moraes Ferreira Jorge et al. [26] in a review that highlighted a synergistic effect between PRF and orthobiologics. The combination of PRF with orthobiologics, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or hyaluronic acid (HA), has shown promising potential in enhancing pain management and tissue repair. PRF has demonstrated a role in neuromodulation and reducing inflammation, as evidenced in studies on knee osteoarthritis and supraspinatus injury, where PRF combined with PRP led to significant pain relief, improved joint mobility, and accelerated recovery [44, 45]. Additionally, PRFʼs ability to modulate inflammatory markers like TNF-α and IL-10 and promote autophagy in affected tissues provides a mechanistic basis for its therapeutic effects [46]. Clinical trials, such as those by Filippiadis et al. [47], indicate that combining PRF with HA further prolongs pain relief and enhances mobility in osteoarthritis patients, highlighting the complementary roles of PRF in pain modulation and HA in joint supplementation. The proposed synergistic effects of PRF combined with orthobiologics are summarized in Figure 2.

Proposed synergistic effects of PRF combined with orthobiologics. This figure summarizes injectable biological therapies and PRF targeting knee joint pathology. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) provides growth factors (PDGF, VEGF, TGF-β) that enhance cartilage repair and reduce inflammation. Stem cell therapies [bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC), adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSC)] exert immunomodulatory effects via secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Hyaluronic acid contributes to lubrication, oxidative stress reduction, and inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity. PRF induces neuromodulation and reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α). Collectively, these approaches aim to achieve pain relief, improved mobility, reduced inflammation, and cartilage protection. Created in BioRender. Varrassi, G. (2026) https://BioRender.com/c8v3618.

PRF has shown promising applications in specific contexts, such as rheumatoid arthritis. In fact, Cho et al. [24] demonstrated that intra-articular application of PRF reduced synovial inflammation and cartilage degradation, improving joint functionality and offering an effective treatment for conditions characterized by chronic inflammation and joint degeneration. De la Cruz et al. [25] documented ultrastructural changes in nerve fibers and microglia treated with PRF, highlighting reductions in oxidative stress and improvements in neuronal plasticity. Although the evidence is encouraging, high-quality randomized controlled trials are needed to validate these findings and optimize protocols for combining PRF with orthobiologics.

PRF is a pivotal technology in pain management, with vast potential to address both existing clinical challenges and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Despite considerable advancements and widespread clinical application over the past three decades, several critical aspects remain insufficiently explored, highlighting the need for ongoing research and innovation. In fact, although PRF is frequently used in clinical practice for managing chronic pain, results remain inconsistent. Several studies—particularly in radicular and joint pain—indicate that the evidence is limited and should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, PRF shows considerable promise for expanding its clinical applications. Importantly, its capacity to modulate inflammatory cytokines highlights its potential as a therapeutic option for conditions such as inflammatory arthritis. Despite these exciting possibilities, much remains unknown about the molecular mechanisms underlying PRFʼs effects. Further research is needed to elucidate pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), PI3K-Akt, and GRK2, which play pivotal roles in pain modulation and inflammation control. Additionally, identifying predictive biomarkers could optimize patient selection and facilitate more targeted and personalized treatment strategies. Integrating PRF with other therapeutic modalities, such as biological therapies, has the potential to enhance its efficacy and expand its applications to new domains. However, the widespread adoption of PRF continues to face barriers due to the lack of standardized protocols and evidence-based guidelines. Bridging these gaps through multicenter randomized controlled clinical trials and the development of comprehensive training programs for healthcare professionals is essential. Establishing globally recognized protocols would improve consistency, reliability, and trust in PRF, ensuring its effective implementation across different healthcare systems. Finally, the integration of PRF with artificial intelligence (AI)-based systems, such as machine learning algorithms, holds the potential to revolutionize its application and efficacy in pain management [48]. Machine learning can analyze large datasets from clinical and preclinical studies to identify patterns, optimize treatment parameters, and predict patient responses based on individual profiles. This approach could enable the customization of PRF settings, such as voltage, pulse duration, and frequency, tailored to the specific needs of each patient, thus enhancing therapeutic outcomes while minimizing complications [48, 49]. However, while the integration of PRF with AI offers promising potential advantages, several ethical concerns must be addressed before this approach can be adopted as a routine practice [50].

This review has several important limitations. First, the overall evidence base for PRF remains limited, with relatively few randomized controlled clinical trials available, and even fewer investigating its immunomodulatory effects in a controlled manner. Most mechanistic insights are derived from preclinical or observational studies, which limits the strength of conclusions that can be drawn. Second, a key limitation is the heterogeneity of patient populations included across PRF studies. Clinical outcomes and underlying mechanisms may differ substantially between conditions such as neuropathic pain, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. For instance, PRF appears to act predominantly through modulation of DRG excitability and microglial activation in neuropathic pain, whereas its potential benefit in osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis may be more closely linked to anti-inflammatory and cytokine-modulatory effects. Pooling these diverse conditions without careful stratification risks oversimplifying therapeutic efficacy and the biological pathways involved. In this review, we synthesized findings across populations to provide a broad mechanistic overview, but we acknowledge that condition-specific analyses are essential to delineate the precise neuroimmune and molecular targets of PRF. Another important methodological limitation of the available PRF literature is the marked heterogeneity in technical parameters used across studies. Voltage, pulse duration, and total application time vary considerably, with no consensus on the optimal settings. Furthermore, several clinical reports fail to provide sufficient detail on these parameters, particularly treatment duration and pulse width, which complicates reproducibility and inter-study comparison. Another underexplored factor is tissue impedance, which interacts with applied voltage and pulse width to determine the characteristics of the generated electric field and, consequently, the volume of neural tissue affected during PRF. Given this variability, no standardized protocol or “best practice” for PRF delivery can currently be defined, and practice often differs substantially between physicians and pain centers. Future trials should systematically report and compare stimulation parameters, while also investigating the influence of tissue impedance, to establish evidence-based technical guidelines that can enhance both clinical efficacy and reproducibility.

PRF has emerged as a pivotal technology in pain management, offering a minimally invasive, neuromodulatory approach to addressing chronic pain. Beyond its established efficacy in conditions like postherpetic neuralgia, CRPS, and osteoarthritis, PRFʼs immunomodulatory properties open promising avenues for treating inflammatory and degenerative diseases. This review highlights PRFʼs ability to influence key molecular pathways, including the modulation of cytokines, microglial activity, and autophagy, which underlie its therapeutic effects in reducing pain and inflammation. Furthermore, its combination with orthobiologics, such as PRP and HA, underscores its potential in promoting tissue repair and enhancing patient outcomes.

Despite its clinical success and versatility, significant gaps remain in fully understanding the molecular mechanisms of PRF, optimizing its technical parameters, and establishing standardized treatment protocols. Future research should aim to elucidate pathways such as MAPK and PI3K-Akt, identify predictive biomarkers for patient selection, and explore synergies with advanced therapies, including gene therapy and biological drugs. Additionally, multicenter randomized controlled clinical trials and uniform training programs for healthcare professionals are critical for ensuring the safe and effective application of PRF.

The integration of PRF into broader therapeutic frameworks represents a transformative opportunity in modern pain medicine. By addressing the challenges of standardization, personalization, and interdisciplinary collaboration, PRF can significantly advance its role in managing complex pain syndromes and beyond, ultimately improving patient quality of life and clinical outcomes.

The key conclusions are:

PRF has emerged as a minimally invasive and versatile technology with promising efficacy in managing chronic pain. Unlike traditional ablative RF, PRF offers a neuromodulatory approach that preserves tissue integrity while effectively reducing pain and inflammation.

This narrative review highlights the immunomodulatory properties of PRF, including its effects on pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, microglial activity, and pathways such as MAPK, PI3K-Akt, and GRK2. These mechanisms contribute to PRF’s dual role in pain relief and inflammation resolution.

The combination of PRF with orthobiologics, such as PRP and HA, has shown synergistic effects, enhancing pain relief, joint mobility, and tissue recovery. This integrative approach could represent a new frontier in personalized and multidisciplinary pain management strategies.

Despite its therapeutic promise, significant gaps remain in optimizing PRF technical parameters and establishing standardized protocols. Addressing these gaps through multicenter trials and the development of evidence-based guidelines is essential for broader clinical adoption.

The integration of PRF with AI systems, such as machine learning algorithms, holds transformative potential by enabling individualized treatment plans and optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

Future research should prioritize elucidating PRFʼs mechanisms of action, exploring its systemic applications, and investigating its potential role in managing comorbidities associated with chronic pain.

AI: artificial intelligence

BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor

CCI: chronic constriction injury

CRPS: complex regional pain syndrome

DRG: dorsal root ganglion

ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase

GRK2: G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2

HA: hyaluronic acid

HVPRF: high-voltage pulsed radiofrequency

IGF-2: insulin-like growth factor 2

IL: interleukin

IRF8: interferon regulatory factor 8

MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase

p-ERK: phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase

PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

PRF: pulsed radiofrequency

PRP: platelet-rich plasma

SNI: spared nerve injury

TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha

The authors extend their gratitude to the Fondazione Paolo Procacci for its invaluable support, which facilitated constructive discussions and revisions during the preparation of this review.

JM, MLGL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. RG: Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. FO, AP, MC: Validation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. GV: Validation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Visualization. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Giustino Varrassi and Matteo Luigi Giuseppe Leoni, who are the Guest Editors of Exploration of Immunology, had no involvement in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 897

Download: 69

Times Cited: 0