Affiliation:

School of Life Sciences, Anglia Ruskin University, CB1 1PT Cambridge, UK

Email: clett.erridge@aru.ac.uk

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2978-346X

Explor Immunol. 2026;6:1003234 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2026.1003234

Received: August 13, 2025 Accepted: December 14, 2025 Published: January 05, 2026

Academic Editor: Wenping Gong, The Eighth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital, China

The article belongs to the special issue Novel Vaccines development for Emerging, Acute, and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases

Vaccines can be highly safe and effective tools for disease prevention. However, improvements in the areas of cost, ease of manufacture, distribution, and administration are sought in the next generation of vaccine platforms. A promising candidate is the recombinant flagellin fusion protein platform, which comprises a protein antigen of interest genetically fused to the bacterial protein flagellin. As flagellin stimulates two distinct pattern recognition receptors of the human innate immune system (Toll-like receptor 5 and nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptor family apoptosis inhibitory protein) and contains helper T-cell epitopes, it is capable of serving as both a carrier and an adjuvant for the target antigen. Studies in animal models and human clinical trials have shown that flagellin fusion proteins can induce diverse humoral (including various subtypes of IgG), mucosal (including secreted IgA), and cell-mediated (TH1 and TH2 CD4+ helper T-cell and CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell) responses to the covalently linked antigen. Such fusions are also capable of eliciting protective immunity in diverse experimental models of infection and cancer. They are effective via numerous routes of administration, including intranasal delivery, without the requirement for adjuvant or complex delivery vehicles. This review aims to cover recent progress in the investigation of flagellin fusion proteins for their potential to stimulate humoral and cellular immune responses to partner antigens, and their prospects for the prevention or treatment of viral infections and cancer.

Vaccination has been pivotal to the dramatic improvements in human health and life expectancy over the past century [1]. The aim of vaccination is to induce immunological memory capable of recognising and responding to a specific pathogen, thereby conferring effective protection against infection or disease caused by that pathogen. This is achieved by exposing the recipient prophylactically to one or more antigens from the target pathogen, in combination with other molecules which stimulate both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system to promote perception of the relevant antigen as a target for elimination [1]. The resulting humoral (antibody) and cellular (T-lymphocyte) responses to these antigens confer the protective memory afforded by vaccination.

Vaccines are conventionally classified as either live or non-live. Live vaccines most often comprise genetically weakened strains of the target pathogen. Such attenuated strains contain essentially the same antigens as the more virulent wild-type organism, but do not cause overt disease. Examples include the oral polio vaccine, measles, mumps, rubella, and rotavirus vaccines. Live vaccines can also be considered to include the recently developed class of recombinant replication-defective viral vectors, which have been modified to express heterologous antigens, such as the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 in the chimpanzee adenovirus Y25 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) [2]. A key advantage of the live vaccine approach is that, because such vaccines comprise whole organisms, a large array of relevant antigens is presented to the immune system during vaccination to generate a broadly protective immune response against multiple targets. Moreover, by attempting to establish infection or replicate within target cells, live organisms trigger the specific innate immune signalling pathways that most effectively promote the correct form of adaptive response to defend against that type of pathogen [3]. These signals may also contribute to the longer-lived immune memory and protection conferred by live vaccines, which is generally seen in comparison with non-live vaccines [3].

However, while live vaccines pose very little risk of harm to healthy subjects, there is still a risk that they may cause illness in elderly or immunocompromised individuals. For some early forms of live vaccine, there is also a very small risk that the organism could revert to a more virulent genotype by mutation, thus causing a more serious infection. For example, the Sabin oral live attenuated polio vaccine was found to be capable of reverting to a more virulent form, causing disease in a very small proportion of recipients [4]. For these reasons, some live vaccines are not licensed for use in elderly or immunocompromised subjects.

By contrast, non-live vaccines pose no risk of causing an infection and may thus be administered to recipients of all ages, including immunocompromised individuals. This class of vaccine includes killed whole organisms (such as the whole-cell pertussis vaccine) and also subunit vaccines, which comprise isolated components of the target pathogen. Subunit vaccines often comprise recombinant proteins (such as the hepatitis B virus vaccine), or polysaccharides covalently attached to a carrier protein (so-called conjugate vaccines, such as the pneumococcal vaccine against S. pneumoniae). The chief advantage of subunit vaccines is their favourable safety profile. However, because they typically lack the innate immune receptor stimulants present in whole organisms, they are generally less immunogenic than live vaccines [5]. This necessitates the use of adjuvants, such as alum, to stimulate innate immune responses to the vaccine preparation, which in turn promote humoral and cellular immunity to the target antigens [6].

More recent additions to the group of non-live vaccines include the synthetic RNA and DNA vaccine platforms [7]. These have excellent potential for rapid development and deployment, particularly in response to emerging or rapidly mutating pathogens. However, they are expensive to manufacture, due to their requirement for complex formulations which are necessary to enable delivery of nucleic acid into the cytosol or nucleus of host cells [8]. RNA vaccines also frequently require a very low temperature cold chain during storage and transportation, and current formulations of nucleic acid vaccines can be given only by injection. Together, these limitations make the use of nucleic acid platforms challenging in low-income countries where issues with funding, cold chain integrity, distribution networks, or training of healthcare workers can be limiting factors.

There is therefore a requirement for improved vaccine platforms that address the limitations of existing vaccines. Ideally, next-generation vaccines should combine the immunogenicity of live vaccines with the excellent safety profile and ease of manufacture of subunit vaccines. They should also be more readily modified to target rapidly evolving threats, such as emerging pathogens or those with a rapid rate of mutation. Next-generation vaccines should also have greater potential to induce mucosal immunity—a trait currently lacking in most subunit vaccines—as this would enhance protection against pathogens entering via the respiratory or gastrointestinal tracts. Finally, improvements in the areas of cost of production, less reliance on low-temperature transport, and needle-free administration would be of much benefit to rollouts in low-income countries.

This review will focus on the potential of the flagellin fusion protein platform to address these limitations in the context of targeting viral infections and cancer.

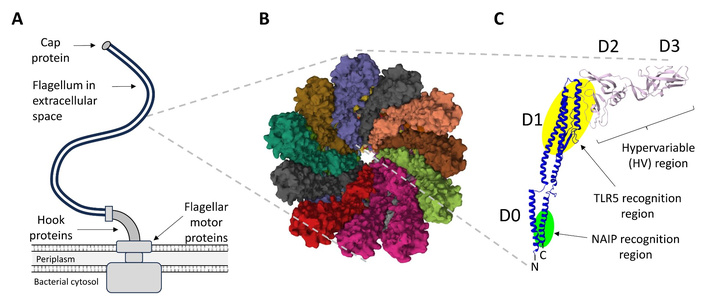

Motile bacteria are able to swim towards chemotactic stimuli, such as sources of nutrients, via the rotation of one or more long, flexible flagella [9]. These complex structures comprise three major functional domains: a cell-wall spanning motor, which is capable of providing torque in either direction; a “hook” structure, which serves as a flexible joint to transmit motor torque; and the filament, which acts as a whip-like propeller (Figure 1A). The filament, which forms the bulk of the flagellum, is a helical structure that comprises many thousands of identical flagellin protein monomers. From a structural perspective, the filaments of most species can be viewed either as a helix comprising approximately 11 flagellin subunits per 2 turns of the helix, or as a tube where the walls comprise 11 strands of protofilaments (Figure 1B). A single flagellar filament can reach up to 15 µm in length and contain up to 30,000 flagellin molecules [10].

Overview of structural properties of the bacterial flagellum and flagellin monomers. (A) The flagellum, which comprises up to 30,000 flagellin monomers, is typically attached to the flagellar motor proteins via a curved hook structure and bound by a terminal cap protein. (B) A cross-sectional view of the E. coli K12 flagellum, looking down the central channel (RCSB: 8CXM). (C) Structural features of a typical flagellin monomer, showing the locations of the highly conserved D0 and D1 domains, and the variable D2 and D3 domains. The regions responsible for recognition by TLR5 and NAIP/NLRC4 are shown in yellow and green highlight, respectively. For S. Typhimurium FljB, the N-terminal TLR5 recognition domain maps to positions 80–118 (GALNEINNNLQRVRELAVQSANSTNSQSDLDSIQAEITQ), the C-terminal TLR5 recognition domain maps to positions 420–451 (LQKIDAALAQVDALRSDLGAVQNRFNSAITNL), and the C-terminal NAIP/NLRC4 recognition domain maps to the final 35 amino acids of the protein (TEVSNMSRAQILQQAGTSVLAQANQVPQNVLSLLR). Those residues contributing most to receptor activation, as determined by alanine scanning, are shown in bold [11–13]. Example structure shown is S. Typhimurium FliC (RCSB: 1UCU). NAIP: nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptor family apoptosis inhibitory protein; NLRC4: NLR family caspase recruitment domain (CARD) domain-containing protein 4; TLR: Toll-like receptor.

The best studied flagellins in the context of vaccination are those of Escherichia coli, Vibrio vulnificus, and (especially) Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhimurium (hereafter abbreviated to S. Typhimurium) [14–16]. While most motile bacteria carry only one flagellin coding gene (e.g., fliC in E. coli), S. Typhimurium may express either of two distinct flagellin genes at any one time, fliC or fljB, as part of a process referred to as phase variation [17]. The two proteins share very similar conserved D0/D1 domains, but the hypervariable D2/D3 domains are quite different, which means they are antigenically distinct. The advantage for the organism is that during the course of a natural infection, switching expression from one flagellin type to another helps to evade the antibody responses of the host, which will have been raised to target the previously expressed flagellin. Phase variation can also change the functional properties of the flagellum. For example, the two types of flagellin may differ in their ability to support swimming, tumbling, or the capacity of the organism to attach to or invade host cells [17].

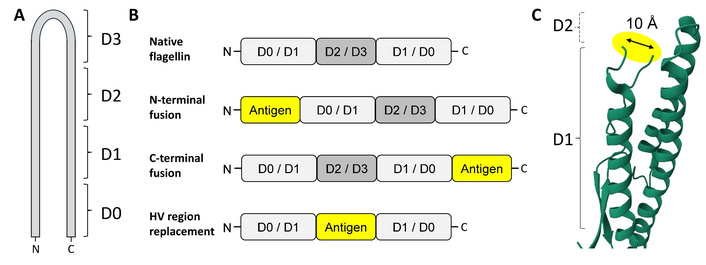

The majority of flagellin proteins generally range between 42 and 56 kDa in mass (e.g., 377 amino acids of V. vulnificus FlaB to 506 amino acids of S. Typhimurium FljB), and comprise four distinct domains (D0–D3, Figure 1C). However, recent studies have shown that some species can express much larger flagellins, some greater than 1,000 amino acids in length, and comprising additional domains (D4, D5) in the hypervariable region [18, 19]. The D0 and D1 domains are the most highly conserved, being present in all flagellins studied so far, and appear to be essential for polymerisation and filament assembly [9]. The D2 and D3 domains are less well conserved, with the D3 domain being particularly variable between species and strains of bacteria, and dispensable for the ability to form filaments. From a topological point of view, flagellin molecules can also be thought of as a hairpin, with both the C-terminal and N-terminal ends of the protein coming together to form the D0 and D1 domains (Figure 2). The more variable regions occur within the middle of the coding sequence. The conserved regions are the targets of innate immune receptors for flagellin, and the hypervariable D3 domain, which is exposed as a protrusion on the surface of the filament, is the immunodominant epitope for humoral immune responses to flagellin [12].

Topologies of commonly studied flagellin fusion proteins. (A) Cartoon indicating the locations of the D0–D3 domains with respect to the primary sequence and “hairpin” structure of flagellin. (B) Cartoon summarising the topologies of commonly studied flagellin fusion proteins in comparison to native flagellin. (C) The distance between the two ends of the “neck” preceding the hypervariable region, i.e., at the interface between D1 and D2, is approximately 10 Å. Insertion of antigens into this region may require the use of flexible, non-immunogenic linker sequences. Structure shown is S. Typhimurium FljB (RCSB: 1UCU). HV: hypervariable.

The full-length flagellin monomer is a boomerang-shaped molecule with a length of approximately 150 Å [9]. It is secreted from the bacterial cytosol through the hollow lumen of the filament (which has an internal diameter of approximately 30 Å), and polymerises, one unit at a time, beneath the cap at the distal end of the growing flagellum. In the laboratory, flagellin may be purified either from native flagella or via vector-driven overexpression in the cytosol, and in either the monomeric or multimeric form, depending on extraction conditions [20].

The mammalian immune system has two major arms: the innate and adaptive responses. The innate response is triggered by the detection of conserved molecular patterns that are present within pathogens (termed pathogen-associated molecular patterns, PAMPs), but absent from the cells of the host organism [21]. PAMPs are recognised by germ-line encoded pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), which serve primarily as an early warning system to raise the alarm and initiate inflammation and pathogen clearance. Key members of the PRRs include the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs), which have evolved to detect the presence of PAMPs outside host cells, and inside host cells, respectively [21]. The innate immune response is fast-acting, requires no prior exposure to a particular pathogen for effectiveness, and slows the progress of an infection, but it is unable to learn or improve substantially over time, and it is not by itself sufficient to clear some forms of infection.

Adaptive immunity is more complex and much slower to develop than innate immunity. However, it brings the crucial advantage of being able to learn how best to fight specific pathogens after encountering them, and the more powerful and specific mechanisms necessary to clear most types of infection from the host. Adaptive immunity relies on the actions of two types of lymphocyte: T-lymphocytes (T-cells) and B-lymphocytes (B-cells).

B-cells secrete antibodies, which are proteins that bind to specific molecules on the surface of a pathogen to aggregate them, label them for killing, or prevent their ability to infect or colonise the host [22]. Unlike PAMPs, the molecules that antibodies can bind to (termed antigens) are extremely structurally diverse, which means the antibody response can be highly specific to a particular type or strain of pathogen. Once an antibody response has been generated against a particular pathogen, the memory of that response is retained within long-lived B-cells, such that the host can respond much more quickly to infection with the same organism in the future [22]. The host is then said to have protective immunity against infection by that particular organism.

Different classes of antibodies have distinct functions in combating infection [22]. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies work primarily in the blood and tissues to label pathogens for clearance or destruction. IgM antibodies are produced early during the adaptive immune response to help slow an infection before more effective IgG antibodies develop, primarily by enhancing the deposition of complement onto the invading organism. IgA antibodies are secreted onto the mucosal surfaces, such as the gut and lung, to help prevent entry of pathogens into the body. IgE antibodies are involved in defence against helminths and also in the pathology of allergies.

T-cells have more diverse functions, in that they serve primarily as key orchestrators of the overall immune response (helper T-cells), or as those with the ability to kill host cells if that is necessary to combat an infection (cytotoxic T-cells, CTLs) [23]. Helper T-cells express the surface marker CD4, and CTLs express the surface marker CD8. Both types of T-cell recognise antigens, but not in the intact form as antibodies from B-cells do. Instead, small fragments of protein antigen must be displayed on the surface of antigen-presenting cells, such as macrophages or dendritic cells (DCs), on a presenting molecule called the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). MHC class 1 presents peptides for recognition by the highly variable T-cell receptor (TCR) of CD8+ T-cells, and MHC class II presents peptides to CD4+ T-cells [23].

Effective vaccines must comprise agents that engage both the innate and adaptive immune responses. Engaging the innate immune response is necessary to label the antigenic cargo of the vaccine as “foreign” or “dangerous”. This is the purpose of the adjuvant, which triggers innate immunity to begin the process of eliciting the more powerful and specific adaptive immune responses to the target antigen [1]. The chosen antigen should be one that is not only expressed by the pathogen of interest, but also abundant on the surface of the pathogen and critical for its survival or fitness. Depending on the type of pathogen targeted, vaccines should ideally elicit robust IgG and/or IgA antibodies to the target organism to help prevent the initial infection, CD4+ helper T-cells to orchestrate a robust defence against the organism, and in the case of intracellular pathogens such as viruses, a CD8+ T-cell response to eliminate reservoirs of infection [1].

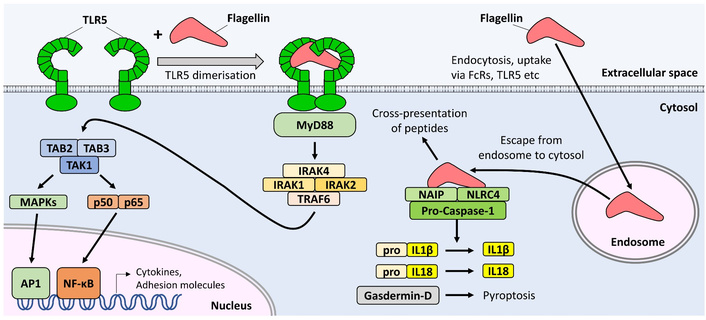

Flagellin is almost unique among bacterial proteins in that it is a bona fide PAMP. Most protein-coding genes of pathogens evolve too quickly for PRRs to co-evolve to target them. However, the D0 and D1 domains of the flagellin molecule have remained so well conserved over millennia that two distinct PRRs of the mammalian innate immune system have evolved to detect them. Specifically, TLR5 detects flagellin located outside of the cell, and nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor family apoptosis inhibitory protein (NAIP) detects flagellin that breaches the cell membrane to enter the cytosol [24] (Figure 3).

Recognition of flagellin by receptors of the innate immune system. Extracellular flagellin is detected by TLR5 in the plasma membrane, resulting in increased expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules via activation of NF-κB and AP1 transcription factors. Cytosolic flagellin is detected by the NAIP/NLRC4 complex, resulting in cleavage of pro-IL1β, pro-IL18, and gasdermin-D, which may in turn promote pyroptosis. AP1: activator protein 1; IL: Interleukin; IRAK: interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase; MAPK: mitogen-associated protein kinase; MyD88: myeloid differentiation factor 88; NAIP: NOD-like receptor family apoptosis inhibitory protein; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B; NLRC4: NLR family caspase recruitment domain (CARD) domain-containing protein 4; TAB: TAK1-binding protein; TAK1: transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1; TLR5: Toll-like Receptor 5; TRAF6: tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6.

The ten human TLRs are type I transmembrane receptors which can be subdivided into two major categories: Those which recognise bacterial cell wall components and signal mainly from the cell surface to regulate inflammatory cytokine production (TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 & 10), and those which recognise nucleic acid motifs and signal from the endosome to trigger mainly anti-viral responses (e.g., production of type I interferons, TLRs 3, 7, 8 & 9) [25]. Ligation of inflammatory TLRs with their respective ligand results in dimerisation of the cytosolic domain of the receptor, which in turn recruits the signalling adaptor myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88). This in turn recruits and activates interleukin (IL)-1R-associated kinases (IRAK) 1, 2, and 4, and tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6. This complex activates the p38 and Jnk mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, and enables release of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) to enter the nucleus, so upregulating expression of genes involved in inflammation, cytokine production, and DC maturation [25]. Notably, there is no induction of interferon-regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) signalling, and consequently no release of interferon-β downstream of TLR5 activation, as there is with the nucleic acid-sensing TLRs (3, 7, 8, 9) or TLR4. TLR5 is expressed on human monocytes, immature DCs, neutrophils, and epithelial cells of the lung and intestine [26]. A similar pattern of expression is seen in mice, although most murine macrophages and DCs express little or no TLR5 [27].

The site of the flagellin molecule recognised by TLR5 comprises regions from both the N- and C-terminal ends, in the D1 domain of the protein (for example, amino acids 80–118 and 420–451 of S. Typhimurium FljB flagellin, Figure 1C). As this region is typically buried within the core of the flagellar filament, monomeric flagellin is a much more potent activator of TLR5 than the filamentous form [12].

A number of flagellin-expressing pathogens, including S. Typhimurium, Legionella pneumophila, and Shigella flexneri, are able to enter the cytosol of macrophages or intestinal epithelial cells. As a result, the human NAIP protein (or NAIP5/NAIP6 in mice), and its signalling partner NLR family caspase recruitment domain (CARD)-containing protein 4 (NLRC4) are expressed in macrophages, DCs, and intestinal epithelial cells. The binding of cytosolic flagellin to NAIP allows it to cause a conformational change in its binding partner, NLRC4, which then oligomerises into an active spiral or wheel shape structure. This structure, called an inflammasome, then cleaves pro-caspase-1 to yield active caspase-1, which may in turn cleave pro-IL1β and pro-IL18 to promote inflammation, and the gasdermin-D protein, to trigger a lytic form of inflammatory cell death called pyroptosis. Only the C-terminal 35 residues of flagellin are necessary for activation of the NAIP/NLRC4 complex (Figure 1C) [13].

Systemic exposure to some TLR-stimulants, such as the TLR4 agonist lipopolysaccharide (LPS), can result in the damaging systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), caused mainly by the excessive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from myeloid cells. However, the systemic response to flagellin has been found to be less inflammatory in murine models, perhaps because expression of TLR5 is higher on epithelial cells than on myeloid cells, and generally induces lower levels of the key inflammatory cytokines IL1-β and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α [28]. Native and recombinant flagellin preparations have also been administered to human volunteers in dozens of small-scale trials since the 1960s, with either minor or no side effects reported [29, 30]. Instead, rather than triggering a SIRS-like response, numerous groups have reported induction of an unusual phenotype of heightened non-specific resistance to subsequent infection or radiation damage in mice [31, 32], which has been reviewed elsewhere [33].

Flagellin serves not only as a PAMP, but also as a prominent antigen during bacterial infection, provoking both humoral and cellular adaptive immune responses [34]. Antibody responses may also be generated to purified flagellin administered by the parenteral, intranasal (i.n.), or oral routes in mice [35]. Human volunteers given purified monomeric flagellin subcutaneously also generate a robust anti-flagellin antibody response without the requirement for adjuvant [29].

The primary target for humoral responses against the native flagellum is the D3 loop of flagellin [12]. Steric hindrance is likely to explain the immunodominance of this epitope, as it is exposed on the surface of the flagellar filament, obscuring the other domains beneath. Supportive of that notion, it has been shown that antibodies can be raised to other domains of the protein if it is administered in the monomeric form [36].

A range of antibody isotypes may be generated in response to purified flagellin in mice, including IgM [37], IgG1 [34, 37], IgG2a/IgG2c [34, 37], and IgA [34, 38]. However, they do not induce IgE [39]—a fortuitous property as this isotype can be a key player in the development of damaging allergies and anaphylaxis. Similar isotype profiles are also induced in antibody responses to epitopes of partner antigens fused to flagellin [5, 15, 40–43]. Most groups report a mixed serum IgG response to flagellin or fusion partner epitopes, but there does not seem to be a clear consensus as to whether the response is predominantly of the IgG1 or IgG2a/IgG2c isotype (which in mice reflects either a Th2 or Th1 bias, respectively, of the responding CD4+ T-cell population). Differences in the purity or polymerisation status of the flagellin used, time of sampling (IgG2c tends to increase more following boost injections [37]), or route of administration may explain some of the differences in isotype bias seen between these studies.

At least three distinct signalling pathways have been shown to contribute to the induction of humoral responses to flagellin. The MyD88 pathway (presumably downstream of TLR5) was found to be a major contributor to the IgG2c [34, 37] and IgA responses to FliC, with the latter also being shown to be independent of inflammasome signalling [34]. The IgG1 response to S. Typhimurium FliC appears to be less dependent on TLR5-MyD88 signalling [34], but robust IgG responses to flagellin were nevertheless reported in the absence of TLR5 or MyD88 in this and other studies, suggesting a contribution of other pathways [34, 37, 44].

One such candidate is the NAIP/NLRC4 pathway [41, 44]. Vijay-Kumar et al. [44] found that the immunisation of mice with a flagellin/ovalbumin (OVA) mixture resulted in high titers of total IgG to both flagellin and OVA in wild-type (WT), TLR5-knockout (KO), and NLRC4-KO mice, but the response was much lower in TLR5/NLRC4 double-KO mice, suggesting some redundancy between the two types of flagellin receptor. While this study did not distinguish between different IgG isotypes, Sanos et al. [41] found that IgG2c, but not IgG1, responses to a flagellin-OVA fusion protein delivered by modified vaccinia virus were also lower in NLRC4 KO mice.

Interestingly, work using recombinant FliC proteins lacking either the TLR5 or Naip5/6 stimulating domains confirmed the existence of a pathway of induction of FliC-specific antibodies that is apparently independent of both TLR5 and NLRC4 [45]. This may reflect the fact that particulate antigens are inherently more immunogenic than monomeric proteins [46], especially when repeating units of the same antigen are displayed on the surface of a particle, as they are on the flagellar filament [47, 48]. Indeed, antibody responses were found to be triggered in murine splenocytes cultured in vitro when exposed to polymerised, but not monomeric, flagellin without the requirement for T-cell help [49]. Thus, flagellin may enhance the immunogenicity of fusion partners not only by stimulating PRR-signalling, but also by polymerising to form particles capable of promoting efficient B-cell receptor (BCR) cross-linking.

It is generally thought that BCR cross-linking alone is not sufficient to trigger robust T-cell-independent activation of B-cells [50]. Such induction requires concomitant stimulation from either TLR-signalling in the responding B-cell, or exposure to inflammatory cytokines from neighbouring cells [51]. Although most studies report that naive B-cells express very little or no TLR5 [52], it has been reported that flagellin may induce TLR5-signalling in short-lived plasma cells, promoting their survival and activation [53]. B-cells are also capable of NLRC4 inflammasome activation [54]. Alternatively, other nearby cell types expressing TLR5 or NLRC4, such as splenic macrophages [52], may release cytokines in response to flagellin to support B-cell activation.

A key limitation of the antibody response generated by T-cell-independent B-cell activation is that it is generally short-lived, restricted to the IgM isotype, and does not undergo maturation to yield high-affinity antibodies. The induction of CD4+ helper T-cell dependent class-switching and affinity maturation is therefore clearly preferable in the context of vaccination [55].

Naive T-cell activation requires presentation of antigen-derived peptides on MHC molecules expressed on the surface of mature, activated DCs. TLR signaling is a well-established inducer of DC maturation, characterized by upregulation of surface antigens such as CD80 (B7-1), CD86 (B7-2), and CD40, and by enhanced migration to lymph nodes [56]. However, whether flagellin can activate DCs directly or not remains a subject of debate, as some groups report that murine DCs express TLR5 [52, 57, 58], and others report they do not [59]. Some reports indicate that murine bone marrow-derived DCs are activated by flagellin in vitro [58, 60], while another found that flagellin stimulates the maturation of human, but not murine, DCs [59]. Regardless of whether DC activation occurs in response to flagellin in vitro, there seems to be agreement that it does occur in vivo, as markers of DC activation are increased when flagellin is administered by injection to mice [61, 62].

Conveniently, the flagellin molecule itself is well-established to contain CD4+ T-cell epitopes, and numerous studies report the generation of robust CD4+ T-cell responses to native flagellin peptides [61, 63–65]. Notably, flagellin also stimulates CD4+ T-cell responses to peptides of its fusion partners [40, 66–68]. Evidence for the induction of both TH1 and TH2 biased responses has been reported. For example, the administration of flagellin to mice results in the induction of both IgG2a/c and IgG1 antibody isotypes (reflective of TH1- and TH2-dependent responses, respectively) targeting the partner antigen [5, 10, 39, 40]. Splenocytes or lymph node cells from flagellin-immunised mice also release TH1 and TH2 specific cytokines [interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-4, respectively] when re-stimulated with flagellin or fusion partner proteins ex vivo [40, 52, 67–69]. Accordingly, direct assays of CD4+ T-cell function reveal activation of clonal expansion by flagellin in vivo, and antigen-specific proliferation ex vivo, for example, in response to co-administered OVA peptides [61], or green fluorescent protein (GFP) protein fused to flagellin [66].

Several potential mechanisms have been put forward to explain how flagellin stimulates CD4+ T-cell responses. The activation of DCs by TLR5-signalling, directly or indirectly via bystander cells, is a likely contributor, as TLR5 was found to be necessary for the efficient induction of CD4+ T cell responses to flagellin immunisation [65]. Human T-cells have also been reported to express TLR5, and flagellin was shown to be capable of providing a co-stimulatory signal equivalent in potency to that of anti-CD28 signalling [70]. An interesting non-classical pathway of response potentiation has also been reported, in which TLR5 functions as an endocytic scavenger receptor, enhancing the delivery of flagellin to vesicles of the MHC class-II presentation pathway [65].

A desirable property for prospective anti-viral and anti-tumour vaccines is the ability to induce antigen-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell responses, since these should have the capacity to eliminate virally infected or transformed cells. Flagellin contains epitopes capable of eliciting such responses, and is a dominant antigen for the induction of CD8+ T cell activation during infection with Salmonella species [71]. Whole E. coli cells expressing a flagellin-OVA fusion protein also efficiently induce presentation of OVA peptides on MHC-I, and stimulate the activation of OVA-specific CD8+ T-cells in mice [72]. However, immunisation studies such as these using whole bacteria do not reveal whether signalling pathways induced by flagellin are alone sufficient to elicit CTL responses, as other PAMPs associated with the intact bacterial cell (particularly the TLR9 stimulant CpG DNA), could provide these signals [58, 73].

Numerous studies have sought to address this point by exploring the potential of isolated flagellin-fusion proteins to potentiate CD8+ T-cell responses, with most reporting positive results. For example, the immunisation of mice with flagellin fused to OVA peptides or GFP stimulated CD8+ T-cell responses to the partner antigens [42, 66, 74]. Likewise, immunisation of mice with influenza HA2 and M2 antigens fused to flagellin induced a ~120-fold increase in frequency of influenza virus-specific central memory CD8+ T-cells, in comparison to controls [40]. Similar studies found that flagellin fused to an H2d-restricted CTL epitope from the parasite Plasmodium yoelii stimulated robust CD8+ T-cell responses to the target antigen, which were absent when immunised with the same antigen lacking flagellin [73].

Diverse forms of experimental evidence support the induction of CTLs specific for partner antigens administered as flagellin fusion proteins. For example, enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays show increased IFN-γ secretion by murine CD8+ T-cells in response to CTL-specific peptides of the partner antigen, and such responses were sometimes comparable with, or superior to, a complete Freund’s adjuvant positive control [42, 73]. Likewise, flow cytometry of splenocytes from immunised mice confirms increased IFN-γ expression by various subsets of CD8+ T-cells after challenge with the partner antigen ex vivo [40]. Dilution experiments using the cell-staining dye carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) revealed a significant proliferation of OVA-specific CD8+ OT-I cells in response to immunisation of mice with a flagellin-OVA fusion protein, further supporting the notion that clonal expansion of CD8+ T-cells occurs in vivo in response to the partner antigen [74]. Finally, the capacity of such CTLs to recognise and lyse target cells presenting peptides of the partner antigen was confirmed by both 51Cr release assay (ex vivo) and CFSE dilution of labelled target cells (in vivo), following immunisation of mice with respective flagellin fusion proteins [66, 73].

However, not all studies utilising flagellin as an adjuvant have observed successful induction of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses. One study found that while the treatment of murine DCs with ligands of TLR3 or TLR9 in vitro induced the proliferation of OVA-specific OT-I CD8+ T cells when challenged with OVA protein, pre-treatment with flagellin did not do so [58]. Furthermore, a study of mice immunized with a lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus antigen expressed on virus-like particles (VLPs) found no significant improvement in antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses when admixing the particles with flagellin [62].

A likely explanation for the lack of effectiveness of CTL induction in the latter two studies may lie in the observation that direct physical linking of flagellin to the target antigen greatly increases the adjuvant activity of flagellin [16, 42, 63, 75], with this effect being particularly pronounced for the induction of cell-mediated immunity [76–78]. For example, it was shown that immunisation of mice with a flagellin-OVA fusion protein resulted in extensive CFSE dilution in CD8+ OVA-specific OT-I cells in vivo, whereas immunisation with OVA admixed with flagellin as separate proteins did not achieve the same result [74]. Accordingly, while the immunisation of mice with tumour cells genetically modified to express a flagellin-OVA fusion protein stimulated robust proliferation of OVA-specific CD8+ OT-I cells, administration of the same cells expressing OVA alone, with flagellin given separately as part of an admixture, did not induce such activation of OT-I cells [11]. Supportive of this notion, it has been shown that adjuvant and antigen must enter the same phagosome concurrently for efficient induction of adaptive immunity, since TLR-signalling from within the phagosome promotes the preferential presentation of peptides from proteins contained within that vesicle [79].

The activation of naive CD8+ T-cells requires presentation of peptides from the target antigen on MHC-I molecules by suitably activated DCs. If the antigen originates from within the cell, such as during viral infection, the constituent peptides are presented via the classical MHC-I loading pathway. This pathway involves the processing of cytosolic proteins into appropriately sized and anchored peptides by the proteasome. These peptides are then transported into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) complex, and loaded onto MHC-I molecules. After this, the intact complex traffics to the cell surface for presentation to CD8+ T-cells.

However, if the antigen originates from outside the cell—as would be the case for antigens from tumour cells or pathogens that do not infect antigen-presenting cells (APCs)—then the process of “cross-presentation” must be employed. This may occur via either of two major pathways. The cytosolic pathway requires the internalisation of extracellular proteins into an endosome or phagosome, and their subsequent translocation from the lumen of that vesicle to the cytosol. The proteins may then be processed for presentation via the same mechanisms as the classical pathway [72]. Alternatively, the vacuolar pathway utilises proteases already present in the endosome or phagosome to release peptides from internalised antigens, which can then be loaded directly onto MHC-I molecules present within the same vesicle, and may thus bypass requirements for cytosolic localisation, proteasomal degradation, or translocation via TAP [72].

Although abundant evidence supports that flagellin is capable of promoting cross-presentation of its fusion partners for the induction of CTL responses (see discussion above), the mechanisms by which it does so are still debated. In particular, while it is well-established that ligands of any TLR are sufficient to induce DC maturation in terms of their capacity to present peptides on MHC-II, it is not yet clear which PRR-signalling pathways are capable of triggering the cross-presentation of extracellular antigens on MHC-I.

For example, it was reported that while CpG ODN (a TLR9 stimulant) and poly (I:C) (a TLR3 stimulant) efficiently induced cross-presentation of OVA peptides in murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) cultured in vitro, LPS, peptidoglycan, and flagellin did not do so [58]. Another point arguing against a significant role for TLR5 in this process is the observation that type I interferon production by DCs appears to be necessary for efficient cross-presentation, since it is blunted in BMDCs from IFN-αβ receptor-deficient mice [80]. Although such cytokines are induced by ligands of TLR3 and TLR9, they are not induced by TLR5 signalling. However, while these observations raise doubts as to whether TLR5 signalling is sufficient to promote cross-presentation, it should be noted that these studies did not use flagellin covalently attached to the target antigen, which, as discussed earlier, may be necessary for effective cross-presentation [11, 74, 79].

An alternative potential mechanism by which flagellin could promote cross-presentation of attached proteins is by facilitating their escape from the endosome or phagosome into the cytosol. While potential mechanisms by which this could occur remain obscure, numerous forms of evidence suggest that this can occur. For example, the treatment of J774A.1 macrophages with extracellular flagellin stimulated caspase-1 activity and production of mature IL1β and IL18, all hallmarks of inflammasome activation by cytosolic flagellin, even in the absence of experimental transfection reagents [44]. Likewise, while WT and TLR5 KO mice given flagellin by intraperitoneal injection produced IL18, NLRC4 knockout mice did not do so, further supporting that extracellular flagellin can reach and stimulate the cytosolic NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasome in vivo [37, 44]. Taken together, these studies raise the possibility that flagellin has an inherent capacity to enter the cytosol of responding cells in significant quantities, consistent with its ability to license the cross-presentation of fusion partners.

A further possibility is that activation of the NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasome itself could promote cross-presentation. Supportive of this, both the TLR5 and NAIP/NLRC4 pathways were found to be equally necessary for priming antitumor CD8+ T cells and suppressing tumour growth in response to flagellin-expressing tumour cells in mice [11]. Moreover, unlike the generation of CD4+ T-cell responses, which appear to have greater dependence on signalling via TLR5 and MyD88 [76], signalling via these mediators is not necessary for the induction of CTL responses to flagellin-linked epitopes, as demonstrated by the induction of such responses in TLR5–/– and MyD88–/– mice [74]. Accordingly, flagellin fusion proteins genetically modified to lack NAIP/NLRC4 activity, while retaining TLR5-stimulating capacity, were found to have greatly diminished capacity to induce antigen-specific CTL responses [11]. Thus, the available evidence supports that there are multiple potential mechanisms by which flagellin can induce CTL responses to partner epitopes, and that these are most efficient when flagellin is fused to the target protein, as opposed to being a component of an admixture.

Early studies exploring flagellin as a potential immunogen focused on the concept of raising antibodies to flagellin itself, rather than partner antigens, with the aim of conferring immunity against specific strains of motile bacteria. As far back as 1969, it was shown that the subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of 5 μg of flagellin purified from Salmonella Adelaide was well tolerated in 108 healthy human volunteers [29]. Recipients saw increases in titres of both IgG and IgM specific for the flagellin, and these titres remained elevated for at least 10 weeks after the first dose. The response transitioned almost entirely to the IgG isotype after a second dose. Interestingly, this study saw no impact of age on peak titres, suggesting that flagellin-based vaccines may retain utility in older populations [29].

Flagellin purified from Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis was also found to induce systemic IgM and IgG responses when administered via the nasal, s.c., and oral routes in mice [35]. Splenocytes from mice immunised in this way produced IFN-γ and IL-2, but little IL-4 or IL-5, when challenged with flagellin in vitro, suggesting a Th1-biased CD4+ T-cell response [35]. When immunised via the oral or nasal routes, mice were substantially protected from infection by live Salmonella Enteritidis, indicating a useful potential of flagellin for mucosal administration and immunity [35].

Subsequent studies in cattle found that intramuscular (i.m.) administration of H7 flagellin purified from E. coli O157 was also capable of eliciting flagellin-specific IgG in serum, and IgA in nasal and rectal secretions [81]. When later challenged orally with live E. coli O157:H7, a reduced colonization rate was observed in immunised cattle, further supporting the potential utility of flagellin in the context of conferring protective immunity at mucosal sites [81].

Taken together, these studies confirm the potential of flagellin to act as a self-adjuvanting molecule, capable of inducing humoral responses in diverse mammalian species via diverse routes of administration.

The concept of partnering flagellin to protein epitopes of interest using gene cloning approaches arose in the early 1990s with the generation of plasmids coding for the Salmonella fliC gene, in which EcoRV restriction sites were conveniently located in the hypervariable region. These sites allowed the in-frame cloning and expression of short epitopes on the surface of the flagellar filament as extensions to the existing D3 domain, when expressed in flagellin-deficient recipient strains, such as the ΔaroA Salmonella Dublin live vaccine strain [75]. Animals could then be immunised by infection with the live vaccine strain.

Early studies found that the immunisation of mice with live S. Dublin cells expressing flagellin fused to an epitope of the cholera toxin subunit B, or the streptococcal M5 protein, generated antibodies specific to the toxin, and protection from streptococcal infection [82, 83]. Similar studies reported efficient induction of antibodies targeting a 21 amino acid epitope from the human immunodeficiency virus env gene [84], and a 16 amino acid epitope from moth cytochrome C was efficiently processed from its flagellin fusion protein and presented via the MHC class II pathway for recognition by CD4+ helper T cells [85]. Whole bacterial cells expressing modified flagella were also shown to promote efficient cross-presentation of the partner epitopes in vitro [72].

In each of these studies, the chosen epitope was compatible with the successful folding and secretion of the fusion protein to form extracellular flagella. However, fusion to some other epitopes or protein partners in the hypervariable (HV) region resulted in a lack of expression of flagella or recoverable fusion protein [75, 77, 82]. Sometimes the protein partner would fail to fold correctly, as shown by a lack of binding to antibodies that recognise the correctly folded antigen. Specific examples of this include various nanobody/linker inserts [86], the vaccinia L1R protein [87], and the OVA protein [74]. It is likely that such issues arise from interference of the fusion partner with the folding, transport, or polymerisation of one or more domains of the fusion protein.

This limitation, in combination with the slightly higher risks associated with use of live vaccines, has increased interest in the purification of recombinant flagellin fusion proteins from the well-established E. coli expression platform for use as subunit vaccines.

Expressing flagellin fusion proteins in the cytosol of E. coli brings numerous advantages over their expression as part of an extracellular flagellum. The principal benefit is that it enables partnering to epitopes that are not compatible with either the flagellar secretion apparatus or assembly into an intact flagellum [86]. Although this means such proteins can no longer be purified by the simple acid wash of bacterial pellets used previously, they may still be purified using other well-established techniques, such as immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) [5, 14, 47].

Cytosolic expression also brings several other advantages. For example, epitopes can be cloned not only in place of the HV region (which comprises the D2 and D3 domains), but also at the N- or C-terminus, which in turn permits the fusion of much larger protein partners (Figure 2). The fully recombinant approach also enables modification of the flagellin sequence to introduce amino acid substitutions, insertions, or deletions with the potential to alter reactogenicity, immunogenicity, multimerisation, or cleavage by lysosomal enzymes to enhance the processing and presentation of T-cell epitopes on MHC molecules [85]. Usefully, some proteins that are difficult to express in E. coli can become well expressed and soluble when fused to flagellin [15]. Finally, with respect to the core issues of safety and prospects for translation, a notable advantage is that the E. coli platform is very well established, with a long track record of use in the development of therapeutics, including in the generation of other subunit vaccines [88].

Fusion of the partner antigen in place of the HV region is an attractive cloning strategy, since this region is the immunodominant target of antibody responses to native flagellin, and its orientation permits, in theory at least, expression of a repeating epitope on the surface of self-assembling nanoparticles comprising multimers of flagellin subunits [20]. However, a mixed picture has emerged from studies exploring whether placement in the HV domain is always superior to placement at the N- or C-terminus, particularly in the context of humoral responses to partner antigens. Some studies have found largely similar immunogenicity of the resulting protein regardless of orientation, while others report a superior outcome with one orientation over another.

For example, placement of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) p24 antigen within the HV region was found to result in superior serum and mucosal antibody responses to the partner antigen, in comparison to placement at the C-terminus [16]. A study of the influenza HA1 antigen fused to flagellin at the C-terminus, HV region, or both, found that placing the antigen within the HV region resulted in the lowest reactogenicity, while the greatest immunogenicity was seen with placement at both the HV site and C-terminus of the same molecule [89].

On the other hand, it was reported that while expression of the vaccinia virus antigen L1R at the N-terminus of flagellin efficiently induced antigen-specific antibodies, no such antibodies were elicited when placed in the HV region [87]. Likewise, studies of the chicken OVA model antigen found that while fusion of the full-length protein at the C-terminus readily induced OVA-specific antibodies [42], no such antibodies were induced when full-length OVA was expressed within the HV region, in spite of robust induction of OVA-specific T-cell responses by the same immunogen [74].

It is likely that the unreliable induction of antibody responses to antigens placed in the HV region reflects improper folding of the target antigen when constrained at both ends by the highly stable flagellin molecule. This raises the possibility that N- or C-terminal cloning will be advantageous for some antigens, since these locations should be more likely to permit folding of the partner into its native configuration.

Alternatively, some evidence suggests that the HV folding constraint can be mitigated by the use of flexible linkers. Taking the S. Typhimurium FljB flagellin as an example, the distance between the ends of the “neck” at the D3/D2 interface is about 10 Å apart (Figure 2C). Partner antigens cloned into this location are therefore only likely to fold properly if their N- and C-terminal ends are no more than that distance apart. However, the “reach” for partner accommodation could be extended by approximately 3.8 Å per amino acid of a flexible linker sequence added to each end of the acceptor or epitope sequence, so permitting the fusion of larger proteins within the HV region. Examples of such linkers, which have been successfully used to fuse antigens to flagellin, include classical G4S sequences [40, 43, 90], the human IgG3 hinge region [16], and several others [14, 46, 48]. Thus, it is likely that antibody responses to HV-placed antigens could be improved by optimisation of such flexible linkers.

Approximately 1 billion people are infected with the influenza virus each year, and up to 5 million of these cases are severe, requiring hospitalisation [91]. Because the virus evolves slowly over time, the two major viral surface proteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), experience a continuous “antigenic drift”, which alters their structures. This necessitates the large-scale production of seasonal vaccines, each tailored specifically to the emerging strains. ~500–800 million influenza vaccines targeting these strains are given each year, largely to protect high-risk groups, such as healthcare workers, elderly individuals, and immunocompromised subjects [91].

Three major types of influenza vaccine are currently approved for use: inactivated viruses, live attenuated viruses, and recombinant proteins. Inactivated viruses (such as Fluzone) must be grown in chicken eggs or cell lines, and are typically given by i.m. injection. Live attenuated viruses (such as FluMist) can be given as a nasal spray, but are typically contraindicated for immunocompromised individuals. The recombinant vaccine Flublok (Sanofi) comprises the HA protein only and is produced in insect cells for i.m. administration. mRNA vaccines for influenza are also being studied, but have yet to progress from clinical trials [91]. Once approved, they will also be administered by injection.

As the market for influenza vaccines is large (estimated to be ~$4 billion in 2012 [91]), and since there is demand for vaccines that are more easily manufactured or with lower risk to immunocompromised subjects, the flagellin fusion platform has received significant interest with respect to its potential for influenza vaccination (Table 1).

Studies of flagellin fusion proteins for influenza vaccination.

| Ref | Antigen/epitope | Epitope location and adjuvant | Species/route of admin | Summary of observed immune responses and results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [92] | 11–15 a.a. B-cell, Th, and CTL epitopes from HA or NP | HV, none | Mice, i.n. | Flagellins containing viral T-cell epitopes induce T-cell proliferation ex vivo and confer 100% protection from a lethal dose of influenza in mice up to 7 months post vaccination |

| [93] | 11–15 a.a. B-cell, Th, and CTL epitopes from HA or NP | HV, none | Mice, i.n. | Pre-immunisation with unmodified flagellin to induce immunity to the carrier protein had no effect on the efficacy of flagellin fusion vaccines given subsequently |

| [69] | 11–15 a.a. B-cell, Th, and CTL epitopes from HA or NP | HV, none | Mice, i.n. | Induction of virus-specific IgG, splenocyte proliferation, and production of IL-2/IFN-γ, reduced viral titres in the lung, and protection from sub-lethal influenza challenge |

| [94] | 24 a.a. from matrix protein M2 ectodomain | C-term, none | Mice, s.c. or i.n. | M2e-specific antibody responses lasting at least 10 months protected mice from a lethal challenge with influenza A virus, with efficacy comparable between s.c. or i.n. delivery |

| [14] | 175–271 a.a. from HA globular head domains | C-term, none | Mice, s.c. | Induction of HA-specific antibodies and protection from lethal challenge with mouse-adapted influenza PR8 virus |

| [78] | 222 a.a. from HA1 globular head domain | C-term, none | Human, i.m. | A single dose up to 8 μg was well tolerated with no serious adverse events, increased titre of anti-HA1 antibodies lasting at least 6 months |

| [30] | 222 a.a. from HA1 globular head domain | C-term, none | Human, i.m. | A single dose of 5 μg was well tolerated and induced a > 10-fold increase in HA1 antibody levels and seroprotection in elderly subjects |

| [89] | 222 a.a. from HA1 globular head domain | C-term & HV, none | Human, i.m. | A single dose of 1.25 or 2.5 μg was well tolerated, inducing a 19-fold increase in anti-HA antibodies by day 21 in 97 subjects aged 18–64 |

| [95] | Various epitopes from HA1 globular head domain | C-term & HV, none | Human, i.m. | A single dose of any of 4 flagellin fusions with HA1 attached at either the D3 domain or the C-terminus increased anti-HA1 titres by day 21 in adults aged 18–40 |

| [5] | 222 a.a. from HA1-2 globular head domain | N-term, none | Mice, i.p. | Boosts at 14 and 28 days elicited robust HA1-2-specific serum IgG1 and IgG2a titers lasting for at least 3 months post-immunisation |

| [47] | Various epitopes from matrix protein 2 or HA2 domain | HV, none | Mice, i.n. | Three different flagellin fusion proteins were cross-linked to form nanoparticles, immunized mice were fully protected against lethal doses of viral challenge |

| [48] | 22 a.a. from M2e and 33 a.a. from helix C of HA stalk | N-term, none | Mice, i.m. | Flagellin was further modified with a coiled-coil domain to produce self-assembling nanoparticles, boosts at days 14 and 28, full protection from lethal viral challenge |

| [40] | Various epitopes from M2e and HA2-2 | C-term & HV, none | Mice, s.c. | Flagellins containing both M2e and MA2-2 epitopes induced strong IgG, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell responses to target antigens, and protection from lethal viral challenge |

All antigens reported in Table 1 were expressed in E. coli, indicating that glycosylation of the antigen is not necessary to elicit immunoprotection. There was no use of additional adjuvant beyond flagellin itself in these studies. C-term: C-terminus; CTL: cytotoxic T-cell; HA: hemagglutinin; HV: hypervariable; IFN: interferon; i.m.: intramuscular; i.n.: intranasal; i.p.: intraperitoneal; M2e: matrix protein 2 extracellular domain; NP: nucleoprotein; N-term: N-terminus; s.c.: subcutaneous.

Early studies focused on the expression of relatively short epitopes (11 to 15 amino acids) derived from the HA or nucleoprotein within the hypervariable region of S. Typhimurium flagellin [69, 92, 93]. Intranasal administration of flagellin fused to a B-cell epitope from the HA protein was sufficient to confer partial protection from influenza challenge in a murine model [92]. However, protection was significantly enhanced when two additional flagellins, displaying one helper T-cell and one CTL epitope from the influenza nucleoprotein, were also included in the immunisation protocol [92]. A similar degree of protection was observed when all three epitopes were combined within a single flagellin molecule [69]. Notably, these studies also found that pre-immunization with the flagellin carrier itself did not impair the protection afforded by subsequent immunisation with flagellin fusion proteins. This notion is further supported by the observations of earlier studies that pre-existing antibodies against flagellin, arising naturally or experimentally, do not impair the efficacy of such vaccines [30, 39, 93]. Likewise, many other studies report improved immune responses after subsequent administrations of the same flagellin fusion protein as part of a prime/boost vaccination strategy, suggesting that adjuvant activity is not neutralised by anti-flagellin antibodies [47, 89, 92, 94].

Further work then found that flagellin fused to a short sequence from the influenza matrix protein M2 induced antibody responses that were superior to those seen when the M2 peptide was delivered with alum as a comparator adjuvant [94]. Interestingly, the extent of protection from viral challenge was similar whether the protein was given by the i.n. or s.c. routes in mice [94]. Likewise, immunisation of mice with S. Typhimurium flagellin fused to a short section of the HA globular head conferred up to 100% protection from challenge with a lethal dose of virus [14]. A similar protein administered via the intraperitoneal route elicited robust HA-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibody responses, indicating a mixed Th1/Th2 response [5].

A series of small human trials (n = 48–100 subjects per study) then found that S. Typhimurium flagellin fused to the HA globular head domain was well tolerated at doses up to 8 μg (given i.m.) [30, 78, 89]. The side effects reported in these trials were minor, including fatigue, headache, and redness around the site of injection. Anti-HA antibodies were consistently raised in each of the trials to levels similar to those achieved by conventional influenza vaccines and lasting for up to 6 months. Notably, a > 10-fold increase in anti-HA titres was observed in a cohort of elderly subjects (mean age 71 years) [30]—a useful property, since immune responses to most other forms of vaccination typically decline with age [96]. A potential explanation for this may lie with prior observations that responsiveness to TLR5 ligands does not appear to diminish with age [87]. Studies to explore whether placement of the HA antigen at the C-terminus, HV region, or both, found that while immunogenicity is largely similar for the different orientations, HV placement appears to result in lower reactogenicity in comparison to C-terminal placement [89]. A larger study of 316 volunteers furthermore found that a quadrivalent mixture of flagellins fused to different HA domains induced seroprotection against all four of the target influenza type A and B viruses, with a tolerability similar to that of existing licensed vaccines [95].

Most of the above studies have focused on the induction of immune responses to immunodominant epitopes of the HA globular head domain, which is also the part of the virus most subject to antigenic drift and variation. More recent studies have explored vaccines targeting more highly conserved regions of the virus, such as the HA stalk domain and matrix protein 2 extracellular domain (M2e). For example, a fusion protein comprising epitopes from both the HA stalk domain and M2e elicited robust antibody, CD4+ T-cell, and CD8+ T-cell responses to the target antigens, particularly when placed in the HV region, after s.c. administration in mice [40]. A similar protein fused to M2e or the HA stalk domain conferred full protection from a lethal dose of virus after i.n. administration in mice [47]. A further innovation of this study was the use of a chemical cross-linker to covalently link multiple flagellins together into “nanocluster” particles, with the aim of increasing immunogenicity through repetitive antigen display [47]. Another group reported assembly of nanoparticles by recombinant modification of flagellin to include coiled-coil oligomerization domains, so allowing self-assembly into octamers similar in size to that of a small virus [48]. When these particles were engineered to present M2e and HA stalk domains, they conferred complete protection from lethal virus challenge after i.m. administration in mice [48].

Distinct forms of immune response are necessary to counter the five major classes of infectious organisms: namely viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and helminths. Broadly speaking, immunity to viruses, protozoa, and intracellular bacteria tends to benefit most from the induction of IgG antibodies, Th1 polarised CD4+ helper T-cells, and CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells. Responses to extracellular bacteria and yeast benefit most from Th1 and Th17 polarised CD4+ helper T-cells, together with opsonising or complement-activating antibodies, such as IgG1 and IgG3. Helminth defence benefits most from Th2-polarised CD4+ helper T-cell responses and IL-13-dependent mucous secretion. Defences against most pathogens at the mucosal surfaces additionally benefit from IgA and/or Th17 helper T-cell responses.

Studies have explored the potential of flagellin-based vaccines to confer protection against pathogens from most of these classes. For example, nasal administration of flagellin fused to the pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) antigen of the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae increased PspA-specific serum IgG and mucosal IgA, and conferred protection from a lethal challenge with live S. pneumoniae in mice [15]. Similarly, i.m. immunisation with flagellin fused to the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane protein OprI was found to lower bacterial burden in infected mice after experimental challenge, allowing them to recover more quickly than controls [97].

As P. aeruginosa can cause life-threatening lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis, and is itself a flagellated bacterium in which the flagellum is an immunodominant target for immune clearance, a clinical trial has been conducted to explore the effectiveness of immunisation with P. aeruginosa flagellin alone to prevent infections with this microbe [98]. 483 cystic fibrosis patients, age 2–18 years, received 40 μg of P. aeruginosa flagellin (without fusion partner), or placebo, i.m. on four occasions. The vaccine was well tolerated and induced robust and durable increases in IgG targeting P. aeruginosa flagellin [98]. Episodes of infection with the organism fell significantly (by 36%) in the group receiving all vaccine doses compared to the placebo group [98].

A further example of a bacterial pathogen successfully targeted by a flagellin vaccine is Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of bubonic plague. Intranasal administration of an admixture of flagellin and the Y. pestis F1 antigen induced robust IgG responses (but, notably, no IgE), and conferred protection against subsequent challenge with a lethal dose of live Y. pestis in mice [39]. A similar vaccine, given at 10 μg i.m., was then shown to induce strong Y. pestis F1-specific antibodies without severe reactogenicity in a human volunteer study [99].

In addition to the examples given in the previous section targeting the influenza virus, efforts have also been directed against other viruses, such as HIV, the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [16, 43, 100]. Intranasal immunisation of mice with flagellin covalently linked to the HIV p24 antigen induced both serum IgG and mucosal IgA to the target antigen [16]. A flagellin fused to glycoprotein 5 of PRRSV also induced robust antibody responses to the target antigen [43]. Notably, this study was performed using C3H/HeJ mice, which are unresponsive to bacterial endotoxin, so ruling out a potential adjuvant effect of contaminating endotoxins [43]. On the other hand, a study of the MERS-CoV surface subunit 1 (S1) domain fused to a TLR4 mimetic 7-mer peptide (RS09) and a short peptide sequence from within the TLR5 binding domain of S. Typhimurium flagellin found that the inclusion of the putative TLR ligands did not improve induction of specific antibodies in comparison to control fusion proteins [100]. However, this study did not test whether these short sequences, alone or as part of the fusion proteins, were capable of stimulating TLR4 or TLR5 [100].

Studies have also explored the potential of flagellin fusion proteins to promote immunity to the protozoan parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which is the causative agent of the most serious forms of malaria. Specifically, immunisation of mice with a self-assembling protein nanoparticle containing peptide sequences from various domains of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein, together with the TLR5 activating domain from flagellin, was found to induce high-affinity antibodies after three doses [46]. The construct also conferred greater protection against challenge with a lethal dose of a transgenic Plasmodium berghei sporozoite expressing PfCSP than control vaccines lacking flagellin [46]. Thus, current evidence supports the notion that flagellin fusion proteins have potential as vaccine platforms for diverse forms of infectious microorganisms.

One of the key limitations of vaccines that are given parenterally, regardless of their composition (i.e., whole organism, subunit, or nucleic acid-based vaccines), is that while they may induce robust systemic immunity, they do not induce significant immunity at the mucosal surfaces [101, 102]. This is a highly desirable property of most vaccines, as the majority of pathogens gain entry to the body via the mucosal surfaces—principally the respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and urogenital tract.

Unlike adaptive immune responses triggered elsewhere in the body, those at the mucosal surfaces confer two key additional protective properties that specifically aid in mucosal defence [103]. The first of these is the class switching of B-cells to promote expression of IgA, which may then be secreted onto the mucosal surface as secretory IgA (sIgA). The second is the fact that both B- and T-lymphocytes activated at the mucosal surfaces are programmed by the local cellular and cytokine environment to preferentially home back to the mucosal surfaces by chemoattraction after activation and proliferation. In this way, lymphocytes activated by mucosal pathogens return to populate the tissues just below the mucosal surfaces, thus conferring optimal protection at these sites.

The induction of sIgA responses is particularly valuable for mucosal defence since, unlike other antibody isotypes which are confined to the blood compartment, sIgA can coat the mucosal surfaces to limit the attachment of pathogens and their entry to host cells. In so doing, this lowers the potential for replication, risk of transmission between hosts, and the rate of emergence of new variants by mutation [16].

The induction of mucosal immunity is therefore a desirable property for vaccines targeting most pathogens. However, only a limited number of orally or intranasally administered vaccines have received approval for use in humans due to numerous technical challenges in their development. The primary difficulty is the establishment of a suitable adjuvant that works well at the mucosal surfaces while also avoiding excessive systemic or off-target effects. In particular, the adjuvants alum and MF59, which are commonly used in human vaccines, do not appear to work well for mucosal immunity [104]. DNA and RNA-based vaccines also do not elicit effective mucosal immunity [1]. As a result, almost all attempts to develop mucosal vaccines in man have focused on either live attenuated vaccines or inactivated whole-organism formulations, which are self-adjuvanting on the basis of their endogenous PAMP content [105]. Examples include the FluMist™ and Nasovac™ intranasal influenza vaccines [106].

However, as discussed above, there are limitations to the use of live attenuated vaccines, particularly with respect to safety in elderly or immunocompromised subjects. Moreover, growing large quantities of virus in eggs (for influenza) can be slow and cumbersome (especially in response to new challenges), relatively expensive, and potentially quite dependent on an effective cold chain for distribution, which limits utility in the developing world.

There is therefore much demand for a subunit-based vaccine that is suitable for the induction of mucosal immunity. However, soluble proteins are not normally immunogenic when delivered at the mucosal surfaces [107], and most antigens lack affinity for the nasal epithelium, so are prone to rapid clearance by mucociliary action [108]. Moreover, mucosal administration of unadjuvanted proteins can result in the induction of tolerance to those proteins via the activation of regulatory T-cells. One approach that has been attempted to circumvent these problems is to fuse the antigen of interest to bacterial toxins, such as E. coli heat-labile toxin or recombinant cholera toxin B-subunit (rCTB) [105]. Both act by binding to GM1 ganglioside receptors on APCs, which in turn facilitate antigen uptake across the mucosal surface and improve antigen presentation [109]. However, interest in the use of these toxoids as intranasal adjuvants has been somewhat reduced since it was observed that they may trigger Bell’s palsy in a small proportion of recipients [110]. The adjuvant CpG ODN is also capable of stimulating mucosal immunity, but it is not approved for human use due to the relatively high risk of induction of autoimmune disease [107].

In light of these challenges, a key advantage of the flagellin fusion protein platform is that it has been shown to work well as a mucosal adjuvant. In particular, there are many reports that i.n. administration of flagellin fusion proteins elicits protection against influenza infection in mice [47, 69, 92, 94]. Notably, these studies report that i.n. administration of flagellin fusion proteins can also trigger systemic induction of antigen-specific IgG [47, 69, 93, 94], splenocyte proliferation [69, 93], and IL2/IFN-γ production [47, 69] (consistent with T-cell responses), and secretion of IgA in the lung [69]. Further supporting broad induction of systemic immunity, i.n. administration of a vaccinia virus antigen fused to flagellin induced serum IgG, mucosal IgA, and CD8+ T-cells in mice [41]. Intranasal flagellin fused to pneumococcal surface protein A also induced IgA in both serum and mucosal secretions of mice [15].

Flagellin has also been shown to have adjuvant activity when given via the oral and rectal routes. For example, flagellin-specific serum IgG and splenocyte IL2/IFN-γ responses were induced to orally administered flagellin (without partner antigen) in mice [35], and rectal administration of flagellin induced local secretion of IgA in cattle [81].

Numerous potential mechanisms may explain the mucosal activity of flagellin. TLR5 is highly expressed by airway epithelial cells, which secrete the chemokine CCL20 (a chemoattractant for DCs) in response to flagellin [111]. TLR5 may also act as a scavenging receptor for flagellin [65], allowing uptake by microfold (M) cells for translocation of the protein to immune cells in the subepithelial layer, or by intraepithelial DCs that project dendrites into the mucosal lumen to sample antigens [112]. Consistent with this notion, radiolabelled flagellin given intranasally was shown to traffic to the cervical lymph nodes, where it then co-localises with CD11c-positive DCs [57]. Notably, in the nasal mucosa, resident cDCs tend to promote non-responsiveness to harmless inhaled antigens [113]. However, this can be overcome by the recruitment of monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs), more capable of mediating T-cell priming, in response to danger signals [113]. It is possible that TLR5 or NLRC4 activation could serve as suitable stimuli for such recruitment. Supportive of this notion, it was shown that CD8+ T-cell activation in response to i.n. flagellin was largely dependent on NLRC4 signalling, consistent with production of mature IL1β by lung DCs in response to flagellin fusion proteins [41].

In addition to the advantages of induction of mucosal immunity, there are numerous other benefits to nasal administration of vaccines. First, by being needle-free, such vaccines avoid biohazardous sharps waste or risk of needlestick injury, and often have higher acceptance by recipients [107]. As they do not require trained personnel to administer, self-administration may be possible, which could be of benefit in mass vaccination programmes [112].

It remains unclear whether i.n. administration of flagellin will be suitable for use in human subjects, since no such trials have been reported to date. However, studies in non-human primates suggest that the positive findings seen in mice are likely to also translate to humans. For example, i.n. immunisation of cynomolgus monkeys with flagellin fused to a Y. pestis antigen induced high levels of systemic antigen-specific IgG, with titres very similar to those of i.m. administration [39]. There was no induction of serum TNF-α or increased body temperature within 24 h of delivery, suggesting little or no induction of systemic inflammation by i.n. flagellin [39]. This observation, together with the promising safety profile of i.m. administration of flagellin in human subjects [30, 78, 89, 95], suggests that i.n. flagellin should also have a favourable safety profile in human trials.

The human immune system is capable of distinguishing cancer cells from healthy cells and eliminating them. Both humoral and cellular immune responses contribute to these functions, which are collectively termed “immune surveillance”. Antibodies can bind to specific antigens on the surface of cancer cells, promoting cell death in at least three distinct ways: (i) by promoting the deposition and activation of complement, (ii) by the activation of natural killer cells (antibody dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, ADCC) and (iii) by the phagocytosis of labelled tumour cells by macrophages (antibody dependent cellular phagocytosis, ADCP) [114]. CD8+ T-cells are also able to kill tumour cells directly, either by releasing perforin and granzyme, or by stimulating the Fas receptor (CD95) on the target cell [115]. Both processes may be enhanced by cytokines released from Th1 polarised CD4+ T-cells responding to tumour-derived antigens [116].

The effector mechanisms of immune surveillance are therefore very similar to those of anti-viral immune responses. However, several key differences explain why anti-tumour immunity is significantly more challenging to develop than anti-viral immunity.

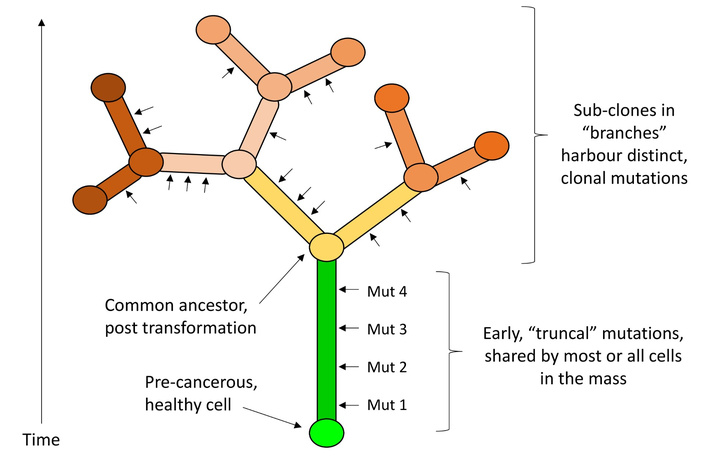

The first is that infectious organisms, including viruses, harbour gene sequences that are very different from those of the host genome. This means they express numerous proteins with low similarity to host proteins, which are therefore readily distinguished as foreign by T-cells and BCRs. By contrast, the majority of antigens expressed by tumour cells are identical to those of healthy cells, and the small proportion that differ from wild-type (so-called “neoantigens”) typically harbour relatively minor alterations, such as single amino acid substitutions [117]. Most T-cells and B-cells capable of responding to host proteins or peptides are either eliminated during negative selection in the bone marrow and thymus (central tolerance) or rendered non-functional by chronic exposure to self-antigens in the absence of danger signals (peripheral tolerance). These mechanisms make it difficult to generate B-cells or T-cells capable of recognising and responding to host proteins with only minor modifications to the native sequence.

A further challenge is that while infectious organisms express PAMPs, which are easily recognised as foreign by PRRs of the innate immune system, such markers of danger and “foreignness” are absent from tumour cells. Thus, even when antigens arise in tumour cells which differ greatly from the non-mutant form, they may fail to generate adaptive immune responses due to the lack of “danger signal” that would ordinarily arise from concurrent exposure to PAMPs.

Next, as tumour cells mutate and evolve rapidly, larger masses frequently discover means of expressing an immunosuppressive milieu in the local tumour environment, using mechanisms such as the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL10 and TGFβ), and recruitment of immunosuppressive cell-types, such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells [118]. Tumour cells can furthermore evade clearance by T-cells by increasing their expression of immune checkpoint proteins, such as PDL1, or downregulating expression of MHC-I, such as by allele loss [119].