Affiliation:

1Student Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz 5166/15731, Iran

2Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Nutrition & Food Sciences, Nutrition Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz 5166/15731, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7442-3685

Affiliation:

3Department of Endocrine Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz 5166/15731, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5664-1497

Affiliation:

4Department of Nursing, Golpayegan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Golpayegan 8773148389, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2270-1444

Affiliation:

5Institute of Nutrition and Functional Foods, Université Laval, Quebec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada

6Department of Food Science, Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences, Université Laval, Quebec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9807-3632

Affiliation:

2Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Nutrition & Food Sciences, Nutrition Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz 5166/15731, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9779-6911

Affiliation:

7Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan 81745, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6143-031X

Affiliation:

2Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Nutrition & Food Sciences, Nutrition Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz 5166/15731, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8294-8708

Affiliation:

2Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Nutrition & Food Sciences, Nutrition Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz 5166/15731, Iran

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6203-5223

Affiliation:

2Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Nutrition & Food Sciences, Nutrition Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz 5166/15731, Iran

Email: homayounia@tbzmed.ec.ir

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6766-0108

Explor Immunol. 2026;6:1003237 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2026.1003237

Received: July 10, 2025 Accepted: January 15, 2026 Published: February 13, 2026

Academic Editor: Roberto Paganelli, G. d’Annunzio University, Italy

For decades, vaccines have been a key tool against microbial infections. However, the high cost of production and purification renders vaccines largely inaccessible to many developing countries. The limitations of conventional vaccines can be overcome by edible vaccines. To produce an oral vaccine, favourable vectors, such as plants and probiotics, are used. Recent studies have revealed the immunomodulatory effects of probiotics. To improve the efficacy of these vaccines, several adjuvant approaches have been employed. Postbiotics can be used as promising therapy for preventing infections and enhancing the host immune system due to their unique biochemical and microbial-derived properties. In this review, we discuss the feasibility of postbiotics as adjuvants for oral vaccines, highlighting their mechanisms of action, safety profile, and potential to enhance both mucosal and systemic immune responses.

The immune system protects the body against various infections and stimuli. The immune system monitors molecules as they move throughout the body to detect and eliminate harmful compounds and pathogens [1]. Infectious diseases claim the lives of about 11 million individuals annually, and 50% of pathogens account for infecting the mucosal membrane [2]. The mucosa of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urinogenital tracts are the primary entrance points for microbial infections (such as human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and influenza). As a result, secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) generated by oral immunization can successfully prevent a wide range of infectious illnesses by creating a defensive network [3–5]. In the recent decade, numerous investigations have attempted to develop novel vaccines that can target viruses and bacteria at different stages. As a result, it is critical to develop new cost-effective vaccines with fewer side effects than those already available. The intestine, considered the longest immune organ, is home to 70–80% of the immune cells in the body [6]. Due to stimulation of immune responses via the mucosal surface, mucosal delivery is an appropriate technique of vaccination [7]. Hence, the new alternative approach of “edible vaccine”, referring to the consumption of plant parts or pro- and post-biotics, comes into the picture [8]. The concept of “edible vaccine” was introduced by “Charles Arntzen” back in 1990 [9]. In the current review, postbiotics are defined primarily as immunomodulatory adjuvants rather than antigen-delivery systems or standalone immunogens. Unlike engineered probiotics, which can act as vectors or carriers, postbiotics enhance oral vaccine (OV) responses indirectly by improving the gut environment and stimulating mucosal immunity. So, the aim of this review is to discuss the evolution of vaccines, mechanisms of action of OVs, factors influencing the OV efficacy, various vectors for edible vaccines, as well as possible future research and application of postbiotics as the next generation of OVs adjuvant.

These vaccines include a type of the living virus that has been weakened, thus it does not cause severe disease in people with healthy immune systems. Attenuated viruses are not able to replicate enough to cause illness but can protect people against future infection [10, 11]. These vaccines, as the closest models of natural infections, are suitable for training the immune system response against particular viruses. Live attenuated vaccines for certain viruses are relatively easily produced. This type of vaccine could become virulent for immunocompromised individuals, such as those with cancer or other immune system diseases. Live attenuated vaccines commonly have to be protected from light and refrigerated. This makes it hard to ship the vaccines overseas, particularly to places with no refrigeration [12].

Another technique of vaccine manufacturing is the inactivation of the pathogen by chemical treatment or by heat. Keeping the epitope structure on the epitope antigen during the inactivation method is critical. Chemical inactivation with formaldehyde has been more successful. For instance, formaldehyde inactivation is used to produce the Salk polio vaccine. Killed or inactivated pathogens do not replicate; the probability of those becoming virulent and causing a disease is zero [13]. Nearly a century ago, researchers reduced the toxicity of diphtheria toxin by formalin [14]. Furthermore, Ramon et al. [15] demonstrated the possibility of inactivating the toxins while keeping their structure intact. The influenza inactivated vaccine was the first vaccine that had been inactivated [16].

Toxoid vaccines have been sufficiently attenuated and can trigger a humoral immune response. Toxoid vaccines don’t give the recipient long-term immunity; therefore, like other kinds of vaccines may need a booster to provide ongoing defense against diseases.

Biosynthetic vaccines like the hepatitis B vaccine include man-made substances that are identical to fragments of the bacteria or virus. Biosynthetic vaccines induce a strong immune response targeting the key part of the bacterial and/or virus. These types of vaccines can safely be administered to immunocompromised individuals and those with chronic conditions [17, 18].

The encoded protein in the DNA vaccine is in its native form and has no denaturation or alteration. Thus, the immune response is similar to the antigen expressed by the pathogen. There are human trials underway with various DNA vaccines, like those for malaria, herpesvirus, and influenza. Currently, there is no human vaccine in use for defending against parasites; however, investigators are hopeful for the immunity of DNA vaccines against parasitic diseases [19].

These types of vaccines use attenuated microorganisms as vectors. A gene encoding the main antigen of a virulent microorganism can be introduced into an attenuated virus or bacterium. Upon the introduction of the modified virus to body, the immunogen is expressed, making an immune response against the immunogen that is derived. Human adenoviruses have been recognized as possible carriers for recombinant vaccines, mostly against diseases like acquired immune deficiency syndrome [19].

Injectable vaccines, aqueous products, usually are prone to extreme temperatures, yet the solid-dose formats, capsules and/or tablets, are fairly stable with less storage, handling, and transport requirements. In addition, the lyophilized form of injectable vaccines shall be reconstituted before use, thus limiting their application. Moreover, injectables may expose the recipient to contamination while requiring strict containment measures and disposal. Nevertheless, capsules, caplets, and tablets are easily transported. The administration of solid-doses of vaccines does not need professional skills, and can be used at home for self-administration [20]. Oral/edible vaccines offer numerous advantages compared with other vaccines. They are cheap, easy to utilize, and have the ability to stimulate local immunity in the intestinal mucosa [21]. Long-term follow-up studies have demonstrated that multiple vaccinations are generally safe and capable of inducing durable antibody responses over several years. Such real-world evidence supports the persistence of immunological memory and highlights the potential for sustained efficacy of OVs [22].

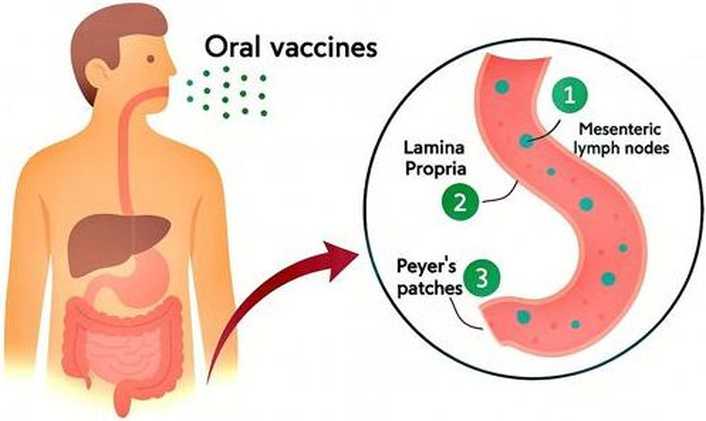

Routes for delivered antigens through the intestine are illustrated in Figure 1. These vaccines can access three parts of the immune system; (1) the lamina propria [that dendritic cells (DCs) and lymphocytes are distributed through the lymphatic drainage channels], (2) the Peyer’s patches (extremely structured lymphoid follicles specific for inducing of immune system responses) [12]; and (3) mesenteric lymph nodes [23]; the same lymphatics can also feed into the peripheral systemic blood circulation through the thoracic duct [24]. Recently, studies have revealed that antigens can be taken up by enterocytes by a phagocytic process [25]. The physicochemical properties of the antigen can control the route taken in the body. Water-soluble tiny particles can diffuse across the semipermeable membranes of blood microcapillaries, while large and lipidic compounds will be retained in the lymphatics and drain into the mesenteric lymph nodes [20].

Three primary pathways by which orally administered vaccine antigens are delivered through the intestine to stimulate the body’s immune system. (1) Mesenteric lymph nodes: Antigens or antigen-loaded immune cells migrate to the mesenteric lymph nodes, a key site for orchestrating adaptive immune responses and promoting systemic immunity. (2) Lamina propria: Antigens cross the intestinal epithelial barrier and enter the lamina propria, where they are captured by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), initiating local immune responses. (3) Peyer’s patches: Specialized lymphoid structures in the intestinal mucosa, Peyer’s patches directly sample antigens from the gut lumen via M cells, facilitating the induction of mucosal and systemic immune responses.

The evidence presented in this section demonstrates that factors such as gut microbiota composition, nutritional status, and mucosal immune regulation play a central role in determining the performance of OVs. By shaping antigen uptake, modulating intestinal immunity, and influencing tolerance or inflammation, these host and environmental determinants directly affect the magnitude and durability of vaccine-induced protection. Therefore, understanding how these variables interact within the gut microenvironment is essential for improving the design, efficacy, and consistency of oral vaccination strategies [26, 27]. General OVs are typically administered in multiple doses as liquid formulations to achieve effective immunity. For example, oral rotavirus vaccines are given in 2–3 doses starting at 6–15 weeks of age, with subsequent doses 4–10 weeks apart. Oral cholera vaccines usually require 2 doses spaced 1–6 weeks apart, with a possible booster after 6 months for high-risk areas, while oral polio vaccines (OPV) are given at birth and at 6, 10, and 14 weeks, sometimes with additional supplemental doses during campaigns. Oral typhoid vaccines generally involve a single primary dose, with a booster after three years in some regions. Timing between doses is critical, and schedules may vary depending on the vaccine type, manufacturer, and regional guidelines [28, 29]. Below, we will discuss the factors that influence OV efficiency, such as microbiota and diet, which affect oral vaccination directly and indirectly through different mechanisms of action.

The gut microbiota is intricately associated with the immune system; so it is possible that immune responses to all types of vaccines are modified depending on microbial communities [30]. It has been revealed that a lack of mucosal bacteria is linked with a reduction of antiviral T-cell responses [31]. Moreover, skin-resident DCs respond to skin microbes [32]. Toll-like receptor (TLR) sensing of bacterial compounds can also contribute to antibody responses. For example, research on the influenza vaccine exposes that interactions between host TLR and bacterial flagellin can trigger macrophages to enhance the production of factors like interleukin-6 (IL-6), a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), thereby resulting in increased plasma cell differentiation [33]. A study on oral typhoid vaccination has demonstrated that intestinal microbial diversity affects vaccine responses. Greater commensal richness and variety showed higher interferon gamma (IFNγ) induction by cluster of differentiation 8 (CD8+) T cells [34]. This results in greater antibody production, as T cell-derived IFN-γ induces IgG2a class [35]. In vaccinated Bengali infants, the frequency of Actinobacteria was positively related to strong T cell responses to OPV, while the presence of Pseudomonadales, Enterobacterales, and Clostridiales was negatively associated with the vaccine responses [36]. The probable effect of intestinal microbiota on OVs is not limited to enteric pathogens [37]. The ensuing cross-talk between the microbiota and mucosal immune cells is vital to the progress of the intestinal immune system [38]. In addition to these effects on the immune system, the microbiota appears to ease the uptake and replication of enteric viruses [39]. Several studies have shown that augmenting the infant microbiota with probiotic supplements has the ability to enhance OV efficacy [40]. However, daily administration of supplements of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG during a placebo-controlled trial provoked an improvement in Rotarix immunogenicity. The gut microbiota plays a critical role in shaping both innate and adaptive immune responses. These modulatory effects are particularly relevant for OVs, as a healthy and balanced microbiota can enhance antigen uptake, promote mucosal IgA production, and improve the efficacy of vaccine vectors delivered via the gastrointestinal tract [41].

Diet is perhaps the primary factor dictating the variety and composition/function of the gut microbiota [42]. A high fiber diet can help maintain a healthy gut microbiota [43]. Equally, disorders in the nutritional status of individuals are associated with impaired immune responses [44]. Malnutrition in children results in lower seroconversion rates of OVs [45]. Undoubtedly, nutrient deficits are related to the loss of OV efficacy. In the following sub-sections, we will discuss nutrition factors that influence the immune system and vaccine efficacy. Adequate nutrition is essential for the proper development and function of the immune system. In the context of OVs, optimal nutritional status can enhance antigen-specific immune responses, support mucosal barrier integrity, and improve the effectiveness of vaccine vectors, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful immunization [46].

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble alicyclic ring-containing category of unsaturated monohydric alcohols [47]. Green and Mellandy, back in 1928, discovered that vitamin A might boost organisms’ anti-inflammatory responses, coining the term “anti-inflammation vitamin” [48]. Retinol, retinal, and retinoic acid (RA) are all forms of vitamin A, with RA having the most biological action [49]. RA is a key regulator of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell intestinal homing in the intestinal lamina propria [50]. Although most data suggest that RA suppresses the formation of inflammatory cells and produces or extends regulatory T cells (Tregs) at pharmacological levels, current research suggests that RA may also reinforce T cell activation and T helper cell responses at low doses [51, 52]. Carotenoid-rich diet-fed rabbits had higher serum levels of IgG, IgM, and IgA, boosting the humoral immunity of the animals [53]. Further research in rats found a link between a lack of vitamin A in the diet and an increase in the number of DCs, as well as dramatically elevated expression of IL-12 and TLR2 in the intestinal mucosa. Rats with lower levels of secretory IgA had lower immunological function, implying that vitamin A is involved in the manufacture of immunoglobulins and has a vital effect on humoral immunity [54]. According to a study, RA effectively synergized with DC-derived IL-6 or IL-5 from gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT) to increase IgA production. Vitamin A plays a key role in maintaining mucosal integrity and supporting immune cell differentiation. These functions are particularly important for OVs, as sufficient vitamin A levels can enhance antigen uptake in the gut, promote IgA production, and improve both mucosal and systemic immune responses to vaccine vectors [55].

Immune cells, like DCs and macrophages, as well as T and B cells, express the vitamin D receptor and 1-hydroxylase. Recent studies have demonstrated a strong association between vitamin D deficiency and an increased incidence of inflammatory autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis [56, 57]. It has been established that monocytes, DCs, macrophages, T and B cells express vitamin D and vitamin D-activating enzyme. Vitamin D is crucial for modulating immune responses, including the activation of DCs and T-cell differentiation. In the context of OVs, adequate vitamin D levels can enhance mucosal immune responses and support the effectiveness of vaccine vectors by promoting balanced antigen-specific immunity [58].

The immune system response is sensitive to changes in zinc levels. Zinc deficiency causes the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-6, and TNF to be produced in higher amounts. Zinc significantly affects the immune system through Th lymphocytes. The lymphocytes are divided into two types: Th1 and Th2. Zinc deficiency in the cell disrupts the balance between Th1 and Th2, favoring Th2. Th1 and Th2 cells execute various functions; thus, the optimum balance must be maintained for a normal immune response [59–61]. As a result, zinc deficiency reduces the amount of T and B cells, making the body more susceptible to infections and weakening its defenses. Zinc is essential for the development and function of immune cells, including T and B lymphocytes, and for maintaining intestinal barrier integrity. These effects are highly relevant for OVs, as adequate zinc levels can enhance antigen uptake, improve mucosal immune responses, and increase the overall efficacy of vaccine vectors delivered via the gastrointestinal tract [62, 63].

Various OV carriers appropriate for the gut environment and their characteristics have been studied. Below, we will discuss their benefits and limitations.

Genetically modified plants are formed by introducing the anticipated gene into a plant to make the encoded protein. OVs against several diseases like cholera, measles, and hepatitis are formed in plants, namely tobacco, banana, potato, etc. [64]. Tobacco, formerly used as a model plant, is perennial and has many benefits, such as fast growth, and has been widely used as an edible vaccine candidate [65]. A main drawback of using the potato as a vector is that it needs to be cooked before use, denaturing the antigen [66]. Maize or rice are staple foods in most of the countries. The main reason why they are appealing as a candidate edible vaccine vector is that they can be kept without chilling for a longer period [67].

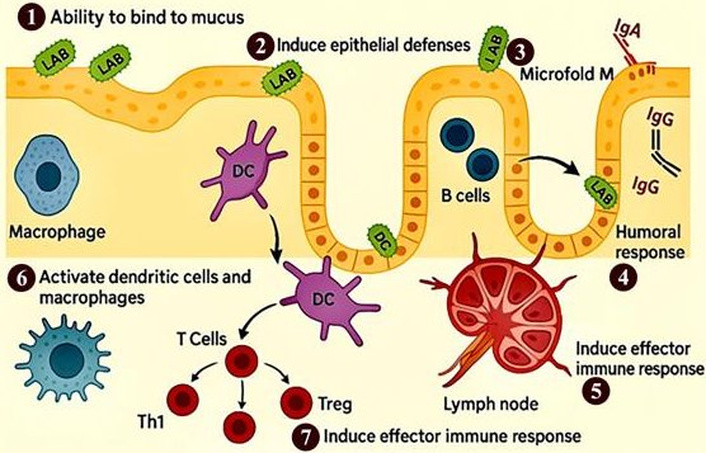

There has been interest in developing recombinant lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as the next class of OV vectors due to their stability at room temperature, natural acid and bile resistance, and endogenous activation of immune responses. LABs are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) and have long been used in food fermentation. Furthermore, they can improve the health of consumers when consumed in an adequate amount [68]. It is important to distinguish between LAB engineered as vaccine vectors and LAB or postbiotics functioning as immunostimulants. LAB vaccine vectors are genetically modified strains that express or deliver specific antigens and therefore act as part of the antigen-presentation pathway to induce targeted immune responses. In contrast, non-engineered LAB and postbiotics do not provide antigen specificity; instead, they enhance immunity through indirect mechanisms such as epithelial barrier reinforcement, cytokine modulation, and activation of mucosal immune cells. Thus, LAB vectors contribute directly to antigen presentation, whereas LAB and postbiotics primarily serve as immunostimulatory adjuvants that amplify or shape the host response to an external antigen [69]. General effects of LAB in the intestinal tract are recognized to include alteration of the intestinal microbiota, enhanced barrier function, and the modulation of the host immune system [70]. For decades, the use of probiotics as an OV vector has been developed against different viral and bacterial pathogens and toxins [71]. The typical LABs’ interactions with the mucosal immune system are shown in Figure 2. LABs can stimulate innate immune response via peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid that activate TLR2, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain NOD-like receptor (NLR) family, and C-type lectin receptors [72, 73].

Mechanism of action of probiotics in modulating the immune system. (1) Mucus binding: Probiotics adhere to the intestinal mucus layer, promoting colonization and competitive exclusion of pathogens. (2) Induction of epithelial defenses: Probiotics enhance the integrity of the intestinal barrier and stimulate the production of antimicrobial peptides. (3) Uptake through microfold (M) cells: Probiotics and their components are sampled by M cells in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, facilitating antigen presentation. (4) Stimulation of humoral responses: Probiotics trigger B cells to produce immunoglobulins, such as secretory IgA, contributing to mucosal immunity. (5) Transport to lymphoid tissues: Antigens and probiotic components are delivered to lymphoid organs, promoting immune cell activation. (6) Activation of macrophages and dendritic cells: These antigen-presenting cells are stimulated to initiate adaptive immune responses. (7) Induction of effector immune responses: Probiotics enhance T cell-mediated responses and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, supporting pathogen clearance and immune regulation. LAB: lactic acid bacteria; DCs: dendritic cells; Tregs: regulatory T cells.

The immunomodulatory effects of LABs are noted in Table 1. In addition, some LABs can bind to the mucosal epithelium or microfold (M) cells, resulting in mucosal colonization. LABs can interact with APCs like DCs and induce IgG. The mechanism of immune cell activation and the cause of immune responses are extremely dependent on the LAB strain. For instance, murine DCs can have different responses reliant on the strain of LAB [73–77].

Immunomodulatory effects of lactic acid bacteria.

| LAB Strain | Type of study | Immunomodulation mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. casei | In-vitro | ↑IL-10 and TGF-β | [74] |

| L. crispatus | In-vitro | ↑IL-10 and TGF-β | [75] |

| L. rhamnosus GG | In-vitro | ↓INF-γ | [76] |

| L. casei | Ex-vivo | ↓IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8 | [77] |

| L. reuteri LMG | In-vitro | ↑TLR2 expression and IL-10 | [78] |

| L. rhamnosusB. longumB. lactic | In-vitro | ↑IL-10↓IL-1β and IL-6 | [79] |

| L. bulgaricusS. thermophilus | RCT | ↑serum IFN-γ | [80] |

| L. bulgaricusS. thermophilus | RCT | ↑CD4/CD8 ratio↑IFN-γ production | [81] |

| B. lactisL. rhamnosus | RCT | ↑Phagocytic activity↑NK cell activity | [82, 83] |

| L. acidophilus | In-vivo | ↑IL-17, IL-23, TGFβ1 and TNF-α | [84] |

| L. reuteri | In-vivo | ↑IL-1β, IL-6 | [85] |

| L. rhamnosus | In-vivo | ↑IL-10/TNF-α ratio | [86] |

| B. breveL. acidophilusL. caseiS. thermophilus | In-vivo | ↓IL-6 and TNF-α | [87] |

| L. acidophilus | In-vivo | ↑Treg and IL-10↓IL-17 | [88] |

| L. fermentum | In-vivo | ↑IL-10↓TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12 | [89] |

| L. plantarum | In-vivo | ↓TNF-α and IL-6 | [90] |

| L. plantarum | In-vivo | ↓IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α and IFN-γ | [91] |

| E. durans | In-vivo | ↑Treg and IL-10 | [92] |

↑: increased; ↓: decreased; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha; NK: natural killer.

Genetically modified LAB, particularly Lactococcus lactis and various Lactobacillus species, have become attractive platforms for mucosal vaccine delivery due to their GRAS status, safety, and intrinsic immunomodulatory properties [93]. Modern vaccine engineering strategies allow LAB to express, secrete, or display antigens in ways that enhance uptake by mucosal immune tissues. Plasmid-based expression remains one of the most widely used approaches, employing strong promoters such as P170, PnisA (used in the nisin-controlled expression system), or constitutive promoters like Phelp to achieve robust intracellular antigen production. The NICE system, in particular, enables precise induction of antigen expression during fermentation, improving protein yields while minimizing the metabolic burden on the host strain [94]. Chromosomal integration strategies provide an alternative with greater genetic stability and improved biosafety, eliminating the need for antibiotic selection markers. Stable integration into loci such as upp, thyA, or neutral chromosomal regions in L. lactis has been shown to maintain antigen expression during gastrointestinal transit, which is essential for consistent mucosal delivery [95, 96]. Another key advancement is the surface display of antigenic proteins using anchoring domains such as LPXTG (for sortase-mediated covalent attachment), or LysM repeats (for non-covalent binding). Surface-anchored antigens are more efficiently recognized by intestinal DCs and M cells, leading to improved stimulation of the GALT and enhanced mucosal IgA responses [97]. Secretion-based systems also represent a critical component of LAB-based vaccine technology. Signal peptides such as Usp45 from L. lactis have been extensively employed to direct heterologous proteins into the extracellular environment [98]. Usp45-mediated secretion is one of the most efficient systems currently available for LAB and has been utilized to deliver cytokines, viral antigens, and bacterial toxins in mucosal immunization models [99]. Other secretion leaders, including SlpA from L. acidophilus, further expand the repertoire of antigens and enzymes that can be released into the culture medium or intestinal lumen [100]. Although whole-cell vaccine vectors such as probiotics and plant-based systems offer powerful platforms for oral antigen delivery, increasing evidence shows that many of their immunological benefits are mediated by the bioactive molecules they produce rather than by the living organisms themselves. This provides a natural transition toward postbiotics, non-viable microbial components and metabolites that retain these immunomodulatory properties while offering improved safety, stability, and mechanistic precision [101]. In the following section, we discuss these postbiotic components in greater detail and highlight their relevance as emerging OV adjuvants.

The term postbiotics refers to all products obtained from non-viable probiotic microorganisms, lysates, cell walls, fractions, secretions, and metabolites that, when received in adequate amounts, show health benefits [102–109]. They exhibit strong antibiofilm activity, helping to disrupt and prevent the formation of harmful microbial biofilms that contribute to chronic infections [110–113]. Certain postbiotic compounds, including organic acids and specific enzymatic metabolites, can also aid in the detoxification and removal of mycotoxins and pesticide residues [114, 115], thereby enhancing food safety and reducing toxic exposure. Postbiotics also could be synthesized in a laboratory through different kinds of methods, such as high pressure, ionizing radiation, thermal treatment, and sonication [116, 117]. Due to the related safety aspect, numerous clinical studies have been done to validate the metabolism and absorption of postbiotics. A handful of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have assessed the side effects of probiotics metabolite (postbiotics), including vomiting, diarrhea, and nausea in individuals consuming Lactobacillus acidophilus, but no side effects were revealed in the remaining RCTs [118, 119].

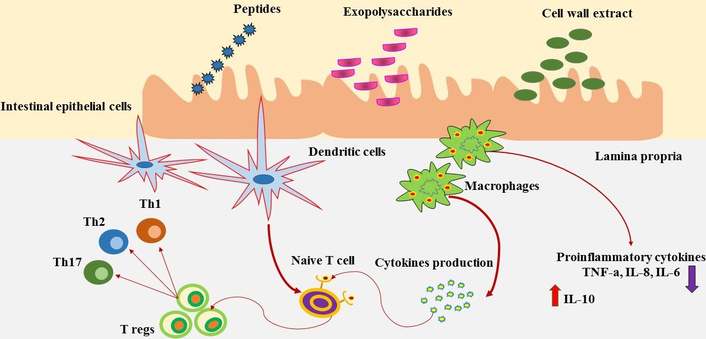

A key step in generating resistance to viral disease is to modulate the immune system [120, 121]. Studies have demonstrated that probiotic metabolites regulate the immune system in a variety of ways (Figure 3), particularly when it comes to seasonal and highly pathogenic influenza virus infections.

Postbiotics could induce activation of dendritic cells, afterward, its mediated differentiation of naïve T cells into Tregs, which would control the extreme T cell response. Furthermore, postbiotics could stimulate the production of cytokines via macrophages that might induce homeostasis through the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

The mechanism of immunomodulation by healthy gut microbiota is extremely associated with their derived postbiotics [122–124]. Some immunomodulatory effects of postbiotics are shown in Table 2.

Immunomodulatory effects of cell-free supernatant (postbiotics) derived from probiotic strains.

| Probiotic strain | Derived postbiotics | Type of study | Immunomodulation mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium | Peptides & proteines | In-vitro | ↑TNF-α, ↓IL-10 | [125] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Peptides & proteines | In-vitro | ↑IL-10, ↓IL-12 | [126, 127] |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Peptides & proteines | In-silico | ↑Th17, Th22 responses | [128] |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Peptides & proteines | In-silico | ↑Th17, Th22 responses | [128] |

| Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis | Exopolysaccharides | Ex-vivo | ↑IL10 | [129] |

| Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis | Exopolysaccharides | In-vivo | ↑Treg response | [130] |

| Lactobacillus reuteri | Exopolysaccharides | In-vitro | Anti-inflammatory | [131] |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | Exopolysaccharides | In-vitro/In-vivo | Treg/Th17 response modulation | [132] |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Exopolysaccharides | In-vivo | Inflammatory cytokine modulation, mucosal barrier reinforcement | [133] |

| Bifidobacterium bifidum | Cell wall extract | In-vitro | Treg differentiation | [134] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Cell wall extract | In-vitro | Immunostimulatory | [135] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Teichoic acids | In-vitro/In-vivo | IL10 production modulation | [136] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Lipoteichoic acids | In-vitro | Suppression of LPS-mediated inflammation | [137] |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Lipoteichoic acids | In-vitro | Proinflammatory, TLR-2/6 ligand | [138] |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Lipoteichoic acids | In-vitro/In-vivo | Radiotherapy protection | [139] |

| Lactobacillus paracasei | Lipoteichoic acids | In-vivo | ↓Leaky gut and inflammation | [140] |

↑: increased; ↓: decreased; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Postbiotics have potent antiviral properties against a variety of infections, especially viruses that cause respiratory illnesses [141, 142]. These molecules are used to prevent influenza A and respiratory syncytial virus infections by decreasing infectious symptoms, diminishing the duration of infection, lowering viral levels in the lungs or nasal washings, and boosting immune activity [143–145]. Lactobacillus plantarum L137, Lactobacillus plantarum 06CC2, and Lactobacillus gasseri TMC0356 soluble postbiotics can be used as possible antiviral agents in pharmaceutical products to treat virus infections [146]. Recently, it was postulated that gut dysbiosis in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) patients could be defined as a cytokine storm, explaining the proinflammatory status of the gut. This could be due to a decrease in bacterial metabolite synthesis [147]. Postbiotics’ anti-inflammatory attributes can reduce the severity of SARS-CoV-2 via decreasing the gut inflammation, activating Tregs, and reducing systemic inflammation by enhancing the gut barrier, thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 from spreading to other organs. To reduce cytokine storms, postbiotics also block several proinflammatory signaling pathways [148]. Balzaretti et al. [149] reported the immunostimulant properties of L. paracasei DG-derived exopolysaccharide by improving the gene expression of the proinflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-6, and particularly that of the chemokines IL-8 and CCL20, in the human monocytic cell line Tamm-Horsfall protein 1(THP-1). Postbiotics exert a broad spectrum of immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activities through well-characterized molecular and cellular mechanisms. These effects are largely mediated through interactions with pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), including TLRs and NLRs, which sense microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) derived from bacterial cell walls, metabolites, or secreted peptides. Components such as peptidoglycans, lipoteichoic acids, EPS, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) can bind to TLR2, TLR4, and NOD2, triggering downstream signaling through MyD88, NF-κB, and MAPK pathways. Activation of these pathways leads to balanced cytokine responses, including increased production of IL-10, IL-6, TGF-β, and IL-22, alongside controlled suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β [150, 151]. These immunomodulatory effects support enhanced IgA class switching in Peyer’s patches, improved antigen presentation by intestinal DCs, and modulation of Th1/Th2/Th17 differentiation, which collectively enhance mucosal immune responsiveness to orally delivered vaccines. Several postbiotic-derived metabolites also regulate antiviral and antibacterial immunity through cellular mechanisms. SCFAs such as acetate and butyrate enhance epithelial barrier integrity by upregulating tight junction proteins (ZO-1, occludin, claudins) via GPR41 and GPR43 signaling [152]. Indole derivatives generated by tryptophan metabolism act on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), stimulating IL-22 secretion and supporting mucosal epithelial repair [153]. Cell-wall fragments from Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium have been shown to increase DC maturation and M-cell transcytosis efficiency, improving the uptake of co-administered antigens. Additionally, bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs) can trigger type-I interferon responses via cGAS–STING and RIG-I pathways, offering synergistic adjuvant activity in OV formulations [154]. Although postbiotics are not antigen-specific vaccines, several experimental studies have explored their use as oral adjuvants in vaccine formulations and have reported indicative dosage ranges. In murine models, orally administered postbiotic preparations typically range between 10–200 mg/kg/day, depending on molecular composition and concentration of bioactive metabolites. For instance, heat-killed L. rhamnosus GG or its cell-wall fractions have been administered at 108–109 cell equivalents/day to enhance mucosal IgA responses [155]. SCFA-rich postbiotic extracts are commonly tested in the range of 50–150 mg/kg and have demonstrated increased antigen-specific IgA and balanced Th1/Th2 responses when co-administered with oral viral antigens [156–158]. Determining an appropriate treatment dose for postbiotics in humans requires a structured and evidence-based translational approach that moves systematically from preclinical data to clinical application. The first essential step is to establish the effective dose range in animal models by evaluating dose–response curves, pharmacodynamic markers (e.g., mucosal IgA levels, cytokine profiles, DC activation), and safety outcomes. The NOAEL (No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level) identified in animals can then be converted into a human equivalent dose (HED) using standard allometric scaling based on body surface area. This approach is widely recommended by regulatory agencies such as the FDA for biologically active compounds [159]. The HED is then typically reduced by a safety factor (commonly 10-fold for novel immunomodulatory agents) to calculate a conservative and ethically acceptable starting dose for early human trials. Currently, no standardized clinical dosing guidelines exist for oral postbiotic vaccine adjuvants, and dose-response evaluations remain one of the major research gaps that require future preclinical and human trials.

Despite substantial preclinical evidence demonstrating the immunomodulatory potential of postbiotics, several critical limitations currently constrain their direct translation into OV adjuvant applications. A major challenge is the pronounced heterogeneity of postbiotic preparations, which can vary considerably in molecular composition depending on the producing microbial strain, culture conditions, and downstream extraction or inactivation methods [160]. This variability complicates batch-to-batch reproducibility, hinders dose standardization, and presents obstacles for developing regulatory-compliant quality-control frameworks. Although postbiotics circumvent many safety concerns associated with live microorganisms, their molecular complexity makes it difficult to identify the specific metabolites or structural components responsible for immunological activity, and the absence of validated potency assays further limits consistent product evaluation [161]. Clinical translatability is further restricted by gaps in understanding how postbiotics behave under physiological conditions in the human gastrointestinal tract. Most existing evidence derives from murine or other animal models, which inadequately replicate human mucosal immunity, microbiome diversity, and metabolic processing of microbial metabolites [162]. Oral delivery imposes additional barriers, including degradation by gastric acidity and variable intestinal uptake, both of which may reduce the bioavailability and immunological efficacy of active compounds [163]. Moreover, the immunological effects of postbiotics are predominantly non-antigen-specific; they act as broad immunomodulators that enhance mucosal readiness rather than directly inducing antigen-specific adaptive immune responses [164]. While valuable for supporting mucosal homeostasis, this intrinsic non-specificity may limit their ability to generate robust and durable protective immunity when used alone. Nevertheless, several promising strategies exist for integrating postbiotics into next-generation OV platforms. In live mucosal vaccine systems based on engineered LAB or plant-derived vectors, postbiotics may be co-formulated to enhance antigen uptake by M cells, prime DC activation pathways, and increase secretory IgA responses [71]. In inactivated or subunit OVs, defined postbiotic molecules such as EPS, SCFA-rich extracts, or purified peptidoglycan fragments can be incorporated into encapsulation platforms, including alginate microspheres, lipid nanoparticles, or enteric-coated carriers to improve intestinal stability and controlled release [165]. Furthermore, combining postbiotics with established mucosal adjuvants such as cholera toxin B subunit, CpG oligonucleotides, or poly(I:C) may generate synergistic immune activation by engaging complementary PRR pathways [166]. Advancing these integrative approaches will require rigorous mechanistic studies linking postbiotic molecular profiles with antigen stability, formulation compatibility, and predictable pharmacodynamic responses, ultimately enabling their rational inclusion in clinically viable OV technologies.

New generations of prophylactic vaccines must be ones that can be kept and distributed easily, accepted by the world legislation, handled by non-medical personnel, and show strong evidence of efficiency. These are all fulfilled by OVs, and future initiatives designed to tackle the burden of infectious diseases, mostly in low- and middle-income countries, must make oral vaccination a high priority. Postbiotics, due to their unique characteristics, including safety profile, improving the immune system, and antimicrobial activity, can be used as promising tools for preventing infection and boosting the health of the host. Future research on postbiotics as OV adjuvants should prioritize establishing optimal dosing strategies, as current studies vary widely in their reported concentrations and lack standardized pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) correlations. Rigorous dose-response experiments are needed to determine the minimum immunologically effective dose, the ceiling dose beyond which no additional benefit occurs, and the safety limits for repeated oral exposure. Similarly, research should focus on formulation science, including encapsulation technologies, micro- or nano-delivery systems, and stabilization methods that protect bioactive metabolites from gastric degradation while ensuring targeted release in the small intestine or Peyer’s patches. Comparative studies evaluating different delivery platforms such as enteric-coated capsules, alginate beads, liposomes, or engineered BEVs are essential to identify which systems most effectively enhance mucosal antigen uptake, IgA secretion, and local immune memory. Another priority is understanding how postbiotics interact with existing vaccine components, including antigens, probiotic vectors, and mucosal adjuvants. Postbiotics may influence antigen stability, modify local cytokine microenvironments, or synergize with PRR-based adjuvants, but these interactions have not been systematically evaluated. Studies should explore how postbiotic metabolites modulate DC activation, T-cell polarization, and follicular helper T-cell responses when co-administered with OVs. Additionally, mechanistic research is needed to determine how specific postbiotic fractions, such as SCFAs, EPS, peptidoglycan fragments, or indole derivatives, shape mucosal immune trajectories during vaccination. Finally, well-designed preclinical-to-clinical translation pipelines, including standardized in vitro potency assays, validated biomarkers of mucosal immunogenicity, and early-phase human trials, will be critical to define evidence-based clinical guidelines for the safe and effective integration of postbiotics into future OV platforms as an adjuvant.

APCs: antigen-presenting cells

BEVs: bacterial extracellular vesicles

DCs: dendritic cells

EPS: exopolysaccharides

GALT: gut-associated lymphoid tissues

GRAS: generally recognized as safe

HED: human equivalent dose

IgA: immunoglobulin A

LAB: lactic acid bacteria

MAMPs: microbe-associated molecular patterns

M cells: microfold cells

NLR: NOD-like receptor

OPV: oral polio vaccines

OV: oral vaccine

PK/PD: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic

PRRs: pattern-recognition receptors

RCTs: randomized controlled trials

SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

SCFA: short-chain fatty acids

TLR: toll-like receptor

Tregs: regulatory T cells

JH, SV, and AAS: Investigation, Validation. RAS: Writing—original draft. AHR: Methodology, Supervision. SA and PGM: Writing—review & editing. MZ and NK: Visualization. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Since the present study is a review study and no animal or clinical studies have been conducted, this issue is not covered in the current study. However, all ethical considerations regarding the design and publication of this research have been observed, and its ethics code is IR.TBZMED.VCR.REC.1401.108.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The research protocol was approved and supported by the Student Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences [Grant number 69635]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 58

Download: 5

Times Cited: 0