Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacy, University of Salerno, 84084 Fisciano, Italy

2National Biodiversity Future Center—NBFC, 90133 Palermo, Italy

3Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra e del Mare, University of Palermo, 90133 Palermo, Italy

Email: mdelia@unisa.it

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5315-3055

Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacy, University of Salerno, 84084 Fisciano, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2887-5012

Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacy, University of Salerno, 84084 Fisciano, Italy

2National Biodiversity Future Center—NBFC, 90133 Palermo, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0718-5450

Explor Foods Foodomics. 2025;3:1010106 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eff.2025.1010106

Received: March 01, 2025 Accepted: November 18, 2025 Published: December 24, 2025

Academic Editor: Filomena Nazzaro, CNR, Italy

The ketogenic diet (KD) is increasingly recognized for its therapeutic benefits in managing metabolic disorders, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and epilepsy. However, adherence to KD can elevate the body’s acid load through ketone body production, potentially leading to metabolic acidosis. Alkalinizing salts, such as sodium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, magnesium, and calcium, play a crucial role in maintaining acid-base balance and mitigating complications associated with this dietary regimen. Evidence from studies published between 2000 and 2024 highlights that these interventions can reduce acidosis-related complications, including bone demineralization, muscle cramps, and fatigue, while improving mineral balance and metabolic stability. These findings suggest that incorporating alkalinizing strategies may enhance the safety and effectiveness of KDs. Further research is needed to define optimal dosing, assess long-term safety, and develop practical clinical guidelines, particularly for vulnerable populations.

The ketogenic diet (KD) has gained considerable attention for its therapeutic applications in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and epilepsy [1–5]. By limiting carbohydrate intake, the KD induces a metabolic state known as nutritional ketosis, characterized by elevated circulating ketone bodies such as β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate. These compounds serve as alternative energy substrates, particularly under glucose-deprived conditions [6].

Although the KD has demonstrated promising outcomes in metabolic regulation, prolonged adherence may increase the body’s acid load, as ketone bodies are weak organic acids that can shift systemic pH toward acidosis. This acid-base imbalance, particularly under conditions of sustained high ketosis, has raised concerns regarding long-term safety, especially in vulnerable populations such as those with pre-existing renal or skeletal conditions [7]. Emerging evidence suggests that chronic metabolic acidosis may contribute to bone demineralization, impaired muscle function, and nephrolithiasis [8–10]. However, the clinical significance of such outcomes in adults on KDs remains underexplored, as most available studies are short-term or extrapolated from non-ketogenic contexts. Importantly, few trials distinguish between the effects of low versus high degrees of ketosis, despite growing recognition that the severity of acidosis and associated risks may differ markedly between these states. To counteract potential acid stress, interest has grown in alkalinizing interventions, such as supplementation with sodium and potassium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, magnesium, and calcium salts. These agents can help restore acid-base homeostasis and support metabolic and skeletal health. While increasing the consumption of vegetables is a well-recognized strategy to reduce dietary acid load (DAL) and support acid-base balance in the general population, this approach by itself is not enough to mitigate the adverse effects of the acidic substances generated by KDs. In this context, bicarbonate- and calcium-rich mineral waters may represent a practical, non-carbohydrate-based alkalinizing intervention. These mineral waters offer an additional means of supporting systemic pH regulation, particularly when other base-forming dietary sources are restricted [11]. However, their use should be considered as part of a broader clinical strategy, and not as a substitute for individualized dietary planning. This narrative review synthesizes findings from clinical, observational, and mechanistic studies published between 2000 and 2024 to assess the role of alkalinizing strategies, both supplemental and dietary, in individuals adhering to KD, with a focus on adult populations. We highlight mechanisms of acidosis during ketosis, summarize evidence on acid-base buffering strategies, and offer preliminary clinical guidance based on literature and clinical experience. Special attention is given to the degree of ketosis as a relevant determinant of side effects and intervention needs.

The KD induces a metabolic state known as ketogenesis, characterized by the production of ketone bodies, including acetoacetate, β-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone [6]. While ketones provide an efficient alternative fuel source in the absence of glucose, they are inherently acidic [11]. As ketone body concentrations rise in the blood, they increase the systemic acid load, resulting in a physiological state called nutritional ketosis [12]. Although nutritional ketosis is often associated with therapeutic benefits in conditions such as epilepsy, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, sustained elevations in acidic metabolites can overwhelm the body’s natural buffering systems, including bicarbonate, phosphate, and protein buffers [13, 14]. When the acid load exceeds buffering capacity, systemic acidosis can occur, with several downstream effects on bone, muscle, renal, and metabolic health [15]. Bone demineralization may develop as the skeleton serves as a reservoir of alkaline minerals [16]; calcium is mobilized from bone to buffer excess hydrogen ions, increasing the risk of reduced bone mineral density and osteoporosis over time [17]. Muscle cramps and fatigue are common due to electrolyte disturbances, particularly losses of potassium and magnesium [18]. Renal function may also be adversely affected, as the KD can exacerbate metabolic acidosis by increasing the DAL and enhancing endogenous acid production through fatty acid oxidation. Moreover, it has been linked to a higher risk of kidney stone formation in patients [19]. In addition, chronic low-grade acidosis can impair enzymatic reactions and metabolic pathways, potentially compromising glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and overall cellular function [20]. The digestive system also responds negatively to an excess of unbuffered acidic substances, presenting with a variety of symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, heartburn, diarrhea, and halitosis. At the cardiac level, increased heart rate and alterations in cardiac rhythm may occur. Recent studies underscore the importance of monitoring acid-base balance in individuals on KD, not only to optimize metabolic benefits but also to prevent complications. Side effects such as nephrolithiasis, muscle cramps, and bone loss are among the most frequently reported and should be anticipated in clinical practice [15, 21].

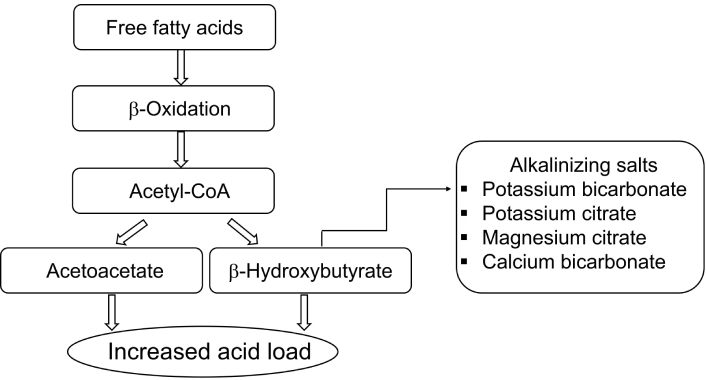

Ketone bodies, including acetoacetate, β-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone, are produced primarily in the liver during periods of carbohydrate restriction or prolonged fasting, such as those observed in KDs. When glucose availability is limited, the body increases fatty acid mobilization from adipose tissue, which is then transported to the liver. These fatty acids undergo β-oxidation to generate acetyl-CoA, the central molecule in ketone body synthesis. High levels of acetyl-CoA promote the condensation of two molecules of acetyl-CoA to form acetoacetate, which is subsequently converted into β-hydroxybutyrate under the influence of NADH [22]. Acetoacetate can also decarboxylate spontaneously to form acetone, which is exhaled. This shift towards ketone body production results in an increased production of acidic byproducts. Specifically, β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate are weak acids, and their accumulation leads to a decrease in plasma pH, contributing to a mild form of metabolic acidosis. This is particularly significant in individuals following KDs, where the ratio of ketone bodies to blood glucose increases substantially, driving the systemic acid load.

Alkalinizing salts, such as potassium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, and magnesium citrate, act to counteract this acidotic state by increasing the bicarbonate buffering capacity of the body [23]. This buffering mechanism helps to stabilize the pH, preventing a significant drop in blood pH (metabolic acidosis) [24].

The efficacy of alkalinizing salts in mitigating this acidosis has been supported by experimental studies. For example, studies examining the administration of potassium bicarbonate and potassium citrate have demonstrated their ability to reduce the systemic effects of chronic metabolic acidosis by enhancing the body’s buffering capacity [25, 26]. These studies suggest that alkalinizing salts can neutralize the excess acid generated during ketogenesis, thus preserving bone health and improving overall metabolic parameters. However, while these studies provide strong evidence for the general benefits of alkalinizing salts in mitigating systemic acidosis, the specific effects in ketogenic populations remain less well defined. The literature is currently limited by a lack of direct studies on the role of alkalinizing salts in KDs, particularly in terms of their ability to modulate blood pH and support acid-base balance in individuals undergoing ketosis, where pH tends to remain stable but at the expense of depleting alkaline reserves from bone and muscle tissues.

Given the potential impact of alkalinizing salts in counteracting the acidotic effects of ketone body production, further research is needed to establish their precise role in ketogenic populations. Clinicians should be aware of the potential for alkalinizing salts to act as adjunctive treatments in mitigating the mild metabolic acidosis often observed in individuals following KDs, particularly in populations at risk for osteoporosis, kidney stones, and other complications associated with chronic metabolic acidosis.

To counteract the acidogenic effects of KDs and modern Western dietary patterns, both supplementation and dietary strategies have been proposed. Alkalinizing salts, including sodium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, magnesium citrate, calcium carbonate, and potassium bicarbonate, play distinct roles in acid-base regulation.

Sodium bicarbonate is a highly soluble compound that rapidly neutralizes excess hydrogen ions in the extracellular space, restoring systemic pH toward normal [27]. Potassium citrate serves a dual function: it not only provides an alkaline load but also reduces urinary calcium excretion and acidification, lowering the risk of kidney stones [28]. Magnesium and calcium salts help correct acid-induced mineral losses; calcium, in particular, offsets bone resorption, while magnesium supports hundreds of enzymatic reactions essential for neuromuscular function [29–31]. Potassium, whether supplied as citrate or bicarbonate, is crucial for intracellular buffering and cardiac function, especially since KD increases urinary potassium losses [32, 33] (Figure 1).

Ketone body production and the role of alkalinizing salts in counteracting metabolic acidosis.

Clinical evidence suggests that alkalinizing salts can mitigate several KD-related complications, including bone demineralization, muscle cramps, and nephrolithiasis [8, 19, 34, 35]. They may also improve mineral balance and cardiovascular stability [36]. Natural sources such as bicarbonate-calcium mineral water provide additional alkalinity and calcium to support skeletal health [11, 37].

However, these interventions must be individualized. Excessive intake can lead to hypernatremia, hyperkalemia, alkalosis, gastrointestinal upset, or hypercalcemia [38–40]. Therefore, careful dosing and regular monitoring of electrolyte status are essential [41, 42].

To synthesize the evidence on alkalinizing salt use in ketogenic therapies, we conducted a comprehensive literature review covering studies published from 2000 to 2024 in PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Search terms included “alkalinizing salts”, “ketogenic diet”, “acid-base balance”, “mineral supplementation”, and individual compounds such as “sodium bicarbonate”, “potassium citrate”, “magnesium citrate”, and “calcium carbonate”. We prioritized peer-reviewed human studies that investigated the effects of mineral supplementation on acid-base balance, bone health, or kidney function. Studies were included if they involved adult populations and reported specific outcomes relevant to ketogenic dietary protocols. Exclusion criteria comprised pediatric studies, animal models, non-interventional reviews, and articles not addressing ketogenic or acid-base-related outcomes. After screening 48 articles, seven were selected for in-depth analysis and are summarized in Table 1.

Summary of reviewed articles on dietary acid load, alkaline interventions, and metabolic health.

| Ref. | Article type | Main focus | Population | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [20] | Narrative review | Chronic sub-clinical systemic metabolic acidosis | General adult | Mechanisms and clinical implications; diet’s role in acid load |

| [43] | Article commentary | Acid-forming properties of foods; PRAL/NEAP models | General population | Critiques current models; highlights the role of unaccounted dietary components |

| [29] | Systematic review | Bioavailability and metabolic role of magnesium supplements | General adult | Shows that magnesium forms with higher bioavailability (e.g., citrate) improve metabolic function and support physiological pH balance; highlights relevance of mineral supplementation for acid-base homeostasis |

| [21] | Review | Ketogenic diet in kidney disease management | Adults with CKD | Reno-protective potential; need for long-term studies |

| [46] | Case report | Ketone salts and metabolic alkalosis | Adult with MTPD | Reports metabolic alkalosis after ketone salts; clinical caution advised |

| [47] | Review | Recurrent calcium kidney stones; diet | Adults with nephrolithiasis | Dietary tailoring for stone prevention |

| [48] | Review | Diet and kidney stone disease | General adult | Acid load reduction lowers stone risk |

PRAL: potential renal acid load; NEAP: net endogenous acid production; CKD: chronic kidney disease; MTPD: mitochondrial trifunctional protein deficiency.

These studies collectively highlight the growing recognition of alkalinizing salt supplementation, particularly during KD therapies, as a vital strategy to maintain acid-base balance and prevent the metabolic complications that can arise due to the acidic nature of ketosis. Table 1 summarizes key narrative reviews, case report, and overview articles relevant to DAL, KD therapies, and metabolic health outcomes. The selected papers provide context for understanding the mechanisms of acid-base regulation, clinical consequences of acidogenic diets, and the potential role of alkalinizing interventions across different populations.

The regulation of physiological pH and its implications for human health, particularly regarding kidney function and metabolic disorders, have garnered significant attention in recent years. A growing body of research has highlighted the substantial impact of dietary patterns, especially those contributing to DAL, on systemic metabolic acidosis, kidney health, and overall metabolic function. This review synthesizes findings from several studies, focusing on the effects of acidogenic diets, potential therapeutic interventions, and the physiological mechanisms by which diet influences pH balance.

A comprehensive review of chronic sub-clinical systemic metabolic acidosis (CSSMA), published in 2022, discusses CSSMA, which is characterized by sustained low pH in arterial serum (~7.35). This condition is largely driven by the shift from traditionally alkaline diets (rich in fruits and vegetables) to the modern Western diet, which is high in animal proteins and low in base-forming minerals [20]. The author emphasizes that prolonged exposure to such acidogenic diets can induce low-grade, sub-clinical acidosis, which negatively impacts a variety of biological systems, including bone density, muscle function, and kidney health. The author further highlights that urinary pH could serve as an early biomarker for CSSMA, as reduced urinary pH in individuals with high DALs may indicate metabolic disturbances. Notably, CSSMA has been linked to dysregulated cortisol production, a pathway that can exacerbate its adverse effects, leading to systemic inflammation and contributing to diseases like osteoporosis, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Supporting these insights, McMullen [43] (2024) explored the acid-forming properties of foods, elaborating on how certain dietary components, particularly animal proteins, increase DAL and contribute to the development of metabolic acidosis. McMullen critically evaluated two key models for assessing DAL: potential renal acid load (PRAL) and net endogenous acid production (NEAP), which both evaluate the acidogenic or alkalinizing effects of foods based on protein and mineral content. However, the author pointed out that these models fail to account for other crucial components such as amino acids, taurine, fructose, and polyphenols, which may influence acid-base balance. He further notes that the Western diet, characterized by high animal protein intake and low fruit and vegetable consumption, exacerbates chronic acid retention and interstitial acidosis—a condition that can contribute to CKD, bone demineralization, and insulin resistance. The author suggests that these models should be refined to include a wider range of dietary components, especially for older populations, who are more susceptible to acid retention due to reduced kidney function.

Although the primary focus of this review is on the adult population, some findings from pediatric studies have been briefly referenced only when they offer broader insight into acid-base physiology. The systemic effects of DAL have been studied across various age groups, and emerging evidence suggests that high DAL may contribute to bone and muscle metabolism disturbances, as well as to chronic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, and CKD [44, 45]. In particular, alterations in interstitial fluid buffering, due to the relatively low capacity of this compartment, may play a key role in the pathophysiological consequences of acid retention. Increasing the intake of fruits and vegetables, while limiting dietary acidogenic components such as animal protein, has been proposed as an effective strategy to support renal buffering capacity and reduce the risk of metabolic acidosis [44].

A key area of interest in the management of metabolic disorders, including CKD, is the use of KDs. These diets have shown promise in improving metabolic function in conditions like type 2 diabetes. Athinarayanan et al. [21] (2024) reviewed the therapeutic potential of KDs in kidney disease, noting that ketones produced during ketosis may provide reno-protective effects. Ketones exhibit anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic actions that could be beneficial for kidney health. However, the review also cautions that the effects of KDs on kidney function remain underexplored, particularly regarding long-term safety and efficacy. The authors suggest that further studies should focus on evaluating the impact of KDs on individuals with impaired renal function to better understand their therapeutic potential in preventing or slowing the progression of CKD. In a similar vein, Stolwijk et al. [46] (2022) reported on a case involving an adult patient with mitochondrial trifunctional protein deficiency (MTPD), who was treated with ketone salts (KSs). The administration of KSs resulted in metabolic alkalosis, potentially due to increased extracellular sodium levels, which disrupted the acid-base balance. This case emphasizes the need for caution in the clinical use of KSs, particularly for individuals with compromised kidney function or metabolic stability. It suggests that alternative forms of ketone supplementation, such as ketone esters, may provide a safer option for these patients.

Dietary interventions also play a crucial role in preventing nephrolithiasis (kidney stones). Malieckal et al. [47] (2023) emphasize the importance of personalized dietary strategies in preventing recurrent calcium kidney stones. Similarly, Dai and Pearle [48] (2022) discuss evidence supporting dietary recommendations for stone prevention, including adequate fluid intake, reduced sodium, modest calcium, and limited animal protein. Both reviews stress the importance of reducing DAL, particularly by increasing fruit and vegetable intake, to prevent the formation of calcium oxalate stones and other types of renal calculi. Skrajnowska and Bobrowska-Korczak [49] (2024) add depth to this discussion by examining how urine pH, a key indicator of the body’s acid-base status, can be influenced by diet, hydration, and medications. Alterations in urine pH, often indicative of acid retention or metabolic acidosis, may serve as an early warning sign of kidney dysfunction, particularly in patients with existing renal or metabolic conditions. The authors highlight the importance of urine analysis for detecting metabolic acidosis or alkalosis early, facilitating the timely management of kidney disease and related complications.

The reviewed literature clearly demonstrates that DAL plays a central role in regulating metabolic health and kidney function and a multidisciplinary approach, combining dietary modifications, clinical monitoring, and personalized treatment strategies, is essential for improving outcomes in patients with CKD, metabolic acidosis, and nephrolithiasis. Continued research into the long-term effects of dietary interventions and the development of more refined models for assessing DAL is crucial for enhancing patient care and refining dietary recommendations.

Several studies have highlighted the significance of dietary and supplemental interventions to counteract the effects of CSSMA, particularly through the alkalinization of the body. The Western diet, often characterized by high consumption of acid-forming foods (such as animal proteins, refined sugars, and processed foods) and low intake of base-forming minerals (abundant in fruits and vegetables), has been strongly associated with chronic low-grade metabolic acidosis. As noted by Naude [20], one of the most effective strategies for neutralizing the effects of an acidogenic diet is increasing the intake of alkaline foods, such as fruits and vegetables, which are rich in base-forming minerals like potassium, magnesium, and calcium. This dietary modification helps shift the body’s acid-base balance toward a more alkaline state, counteracting the acidosis induced by modern eating habits.

Beyond dietary changes, supplementation with alkalinizing minerals such as potassium citrate, potassium bicarbonate, calcium carbonate, and magnesium citrate has shown considerable promise in reducing the systemic effects of metabolic acidosis, particularly in relation to bone health and kidney function. Numerous clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of these supplements in improving metabolic parameters and mitigating the negative effects of chronic acid load on the body.

Potassium citrate supplementation has been extensively studied for its ability to neutralize systemic acidity and support bone health. A landmark study by Sellmeyer et al. [25] administered 90 mmoL/day (approximately 9,733 mg/day) of potassium citrate to postmenopausal women and observed significant improvements in bone density. In line with these findings, Moseley et al. [32] tested higher doses of potassium citrate, ranging from 60–90 mmoL/day (6,480–9,733 mg/day), in older adults. This supplementation helped maintain bone mineral density and reduced urinary calcium excretion, suggesting that potassium citrate could be a therapeutic agent for populations at risk of osteoporosis and bone mineral loss. Potassium bicarbonate has also been shown to counteract bone demineralization. Frassetto et al. [26] and Dawson-Hughes et al. [33] found that doses of 30–90 mmoL/day were effective in preserving bone mineral density in postmenopausal women and older adults, while Sebastian et al. [50] reported that 60–120 mmoL/day significantly reduced DAL and helped prevent bone demineralization.

Magnesium and calcium supplementation also play an important role in mitigating the effects of acid retention. Magnesium, a critical cofactor in numerous enzymatic reactions, is essential for maintaining muscle function and electrolyte balance. Supplementation with magnesium citrate has been shown to alleviate symptoms such as cramps and fatigue, which are commonly experienced in ketogenic dietary regimens. Calcium carbonate, in turn, supports bone health by buffering systemic acidity and reducing the need for calcium mobilization from bone stores. Domrongkitchaiporn et al. [51] demonstrated that calcium supplementation, in combination with alkalinizing agents, helped preserve bone mineral density and reduced the risk of fractures in individuals experiencing chronic acidosis.

In a study by Maurer et al. [52], the administration of a combination of sodium bicarbonate and potassium bicarbonate at 0.55 mmoL/kg body weight resulted in improved metabolic parameters and significant reductions in the body’s acid load. These findings support the utility of sodium bicarbonate as an adjunct strategy to restore acid-base balance in patients with metabolic acidosis.

In addition to skeletal outcomes, potassium citrate has shown specific benefits for kidney health and the prevention of nephrolithiasis. For example, McNally et al. [53] evaluated the effects of 2 mEq/kg/day of potassium citrate in children undergoing KD therapy and observed a significant reduction in urinary acid excretion, a major risk factor for kidney stone formation. Carvalho et al. [54] reported that a dose of 55 mEq/day of potassium citrate, administered to adults after lithotripsy, reduced urinary acidity and significantly lowered the recurrence rate of kidney stones.

The collective evidence from these studies indicates that alkalinizing minerals, including potassium citrate, potassium bicarbonate, magnesium citrate, calcium carbonate, and sodium bicarbonate, are effective in neutralizing the systemic effects of chronic metabolic acidosis, preserving bone health, and supporting renal function. These supplements may serve as essential components of clinical strategies to manage acid-base disturbances, particularly in aging populations, individuals following KDs, and patients at risk for nephrolithiasis or osteoporosis. Moreover, increased consumption of fruits and vegetables rich in base-forming minerals is strongly recommended as a complementary dietary measure.

However, it should be noted that much of the available evidence derives from studies conducted in the general population rather than in individuals following KDs. Further research is needed to directly assess the efficacy and safety of alkalinizing salt supplementation within ketogenic dietary protocols. In addition to the narrative and clinical reviews summarized in Table 1, we also examined a series of experimental studies that directly investigated the effects of alkalinizing mineral supplementation on acid-base balance, bone health, and renal outcomes in adult populations. These studies, summarized in Table 2, provide quantitative evidence to support the proposed supplementation guidelines and contextualize the clinical recommendations discussed.

Summary of experimental studies on alkalinizing salt interventions and acid-base balance in adults.

| Ref. | Population | Intervention (dose) | Outcomes measured | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | Postmenopausal women | Potassium citrate 90 mmoL/day | BMD, urinary calcium | Improved BMD; reduced urinary calcium; neutralized acidity |

| [32] | Older adults | Potassium citrate 60–90 mmoL/day | BMD, urinary calcium | Maintained BMD; reduced urinary calcium |

| [26] | Postmenopausal women | Potassium bicarbonate 30–90 mmoL/day | BMD, bone resorption | Preserved BMD; reduced bone turnover |

| [33] | Older adults | Potassium bicarbonate 30–90 mmoL/day | BMD, bone turnover markers | Lowered calcium excretion; reduced bone resorption |

| [50] | Postmenopausal women | Potassium bicarbonate 60–120 mmoL/day | Net acid excretion, calcium balance | Decreased acid load; prevented bone demineralization |

| [51] | Adults with chronic metabolic acidosis (distal renal tubular acidosis) | Alkaline therapy (potassium citrate) | BMD, bone histology | Correction of metabolic acidosis improved bone histology and was associated with preservation and significant improvement of BMD |

| [52] | Healthy adults | Sodium + potassium bicarbonate (0.55 mmoL/kg BW) | Acid-base balance | Improved acid-base status; reduced dietary acid load |

| [54] | Adults post-lithotripsy | Potassium citrate 55 mEq/day | Kidney stone recurrence, urinary pH | Reduced acidity; lowered recurrence rate |

BMD: bone mineral density; BW: body weight.

Based on the above evidence and the authors’ clinical experience, we propose tentative guidelines for alkalinizing salt use in adults on KD (Table 3). These include recommended dosages, frequencies, and monitoring parameters for sodium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, magnesium citrate, calcium carbonate, and bicarbonate-calcium mineral water. These guidelines are preliminary and drawn primarily from general dietary studies, with supporting data from two pilot interventions in psoriasis and fibromyalgia patients undergoing ketogenic protocols [55, 56].

Preliminary clinical guidelines for alkalinizing salt supplementation in adults on ketogenic diets: suggested dosages and monitoring parameters.

| Alkalinizing salt | Suggested dosage range | Frequency | Clinical monitoring parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium bicarbonate | 500–1,000 mg per day | 1–2 times daily | Monitor for signs of alkalosis, serum sodium levels, blood pressure |

| Potassium citrate | 1,000–1,500 mg per day | 1–2 times daily | Monitor potassium levels, renal function, ECG for arrhythmias |

| Magnesium citrate | 750–1,500 mg per day | 1–2 times daily | Serum magnesium levels, renal function, signs of muscle weakness |

| Calcium carbonate | 750–1,500 mg per day | 1–2 times daily | Monitor serum calcium levels, kidney function, signs of hypercalcemia |

| Bicarbonate-calcium mineral water | 2,000–3,000 mL per day | 2–3 times daily | Monitor calcium levels, hydration status, renal function |

These dosages are for adults. The safety of these supplementation regimens for vulnerable populations (elderly, children, individuals with renal impairment) has not been well-established and requires further clinical evaluation. These preliminary guidelines are based on data from the interventional studies summarized in Table 2, previously published ketogenic interventions [55, 56], and the authors’ clinical experience in nutritional management.

The KD, widely recognized for its effectiveness in weight loss and metabolic health, is often associated with an increased acid load due to the production of ketone bodies. While nutritional ketosis offers several metabolic benefits, sustained ketone body production may contribute to metabolic acidosis, which may have detrimental effects on various physiological systems, including bone health, muscle function, and kidney health. The supplementation of alkalinizing salts, such as sodium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, magnesium, and calcium, has been identified as a key strategy to maintain the body’s acid-base balance and mitigate the adverse effects of acidosis.

In particular, sodium bicarbonate and potassium citrate play vital roles in neutralizing excess acidity, thus helping to prevent bone mineral loss and muscle fatigue associated with metabolic acidosis. Magnesium supplementation, particularly in the form of magnesium citrate, supports muscle function and prevents muscle cramps common in individuals on ketogenic regimens. Additionally, the use of bicarbonate-calcium mineral water provides a natural means to counterbalance metabolic acidosis, replenish calcium, and improve hydration, further contributing to metabolic stability. While the evidence supports the beneficial effects of these supplements, their use should be individualized, considering factors such as the severity of ketosis, the individual’s health status, and any pre-existing conditions. Monitoring is essential to ensure that supplementation does not lead to adverse effects, such as hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, or other electrolyte imbalances. Despite these promising findings, further research is necessary to establish comprehensive guidelines for mineral supplementation in the context of KDs. This is particularly important for vulnerable populations, including the elderly, children, and individuals with impaired renal function. Optimizing the dosages and combinations of alkalinizing salts will be crucial for maximizing their therapeutic potential and ensuring their safety.

By integrating alkalinizing salts and mineral-rich water into the ketogenic regimen, individuals can not only optimize their metabolic health but also minimize potential side effects such as osteoporosis, kidney stones, and systemic inflammation associated with sustained acidogenic dietary patterns.

Although the hypothesis that ketosis may lead to metabolic acidosis and its related complications is supported by physiological models and preliminary evidence, several important limitations persist in the current literature. First, there is a lack of direct clinical studies specifically assessing the impact of KDs on acid-base homeostasis and its consequences on bone, muscle, and renal health. Most of the available data come from observational or short-term interventional studies that are not exclusively conducted in ketogenic populations.

Additionally, the majority of existing trials evaluating the use of alkalinizing salts are of limited duration. Consequently, the long-term effects of these interventions, especially on skeletal integrity, muscular performance, and kidney function, remain insufficiently characterized. Compounding this issue is the small sample size of many published studies, which restricts the ability to generalize the findings to broader clinical populations. Furthermore, variability in supplementation protocols, such as inconsistent dosages and salt formulations, makes it difficult to determine the most effective strategies for mitigating acidosis in individuals adhering to KDs.

To advance the field and develop evidence-based recommendations, several areas warrant focused research. Well-designed, long-term randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to investigate the efficacy and safety of alkalinizing salt supplementation in people following KDs. These trials should evaluate comprehensive outcomes, including biochemical markers of acidosis, bone mineral density, muscular function, and renal parameters.

Future studies should also aim to include larger and more diverse populations, including individuals with metabolic comorbidities such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and early-stage renal impairment. This will enhance the external validity of findings and help identify subgroups that may particularly benefit from supplementation.

Equally important is the need for standardized supplementation protocols. Establishing optimal dosing regimens and selecting the most appropriate alkalinizing agents will allow for consistency across clinical studies and improve the formulation of practical clinical guidelines. Mechanistic studies should also be prioritized to elucidate how alkalinizing salts modulate acid-base regulation and influence physiological systems such as bone remodeling, electrolyte homeostasis, and renal filtration.

Finally, clinical research should incorporate structured monitoring strategies to assess the safety and effectiveness of supplementation. This includes tracking changes in mineral balance, acid-base biomarkers, kidney function, and patient-reported outcomes. The development of clear clinical protocols will support healthcare professionals in managing ketogenic regimens while minimizing risks associated with acid retention.

In conclusion, targeted, high-quality research is essential to clarify the role of alkalinizing salts in ketogenic therapy. Addressing these limitations will contribute to the development of robust, individualized supplementation guidelines aimed at optimizing metabolic outcomes and reducing complications in this growing patient population.

CKD: chronic kidney disease

CSSMA: chronic sub-clinical systemic metabolic acidosis

DAL: dietary acid load

KD: ketogenic diet

KSs: ketone salts

MD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. GC: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. LR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Resources, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Luca Rastrelli, who is the Associate Editor of Exploration of Foods and Foodomics, had no involvement in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 4000

Download: 93

Times Cited: 0