Affiliation:

1Department of Bacteriology, Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, Accra P.O. Box LG 581, Ghana

Email: vadjei@noguchi.ug.edu.gh

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7072-2947

Affiliation:

1Department of Bacteriology, Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, Accra P.O. Box LG 581, Ghana

Email: gmensah@noguchi.ug.edu.gh

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6499-5946

Affiliation:

2Institute for Environment and Sanitation Studies, University of Ghana, Accra P.O. Box LG 209, Ghana

Affiliation:

3Radiation Technology Centre, Biotechnology and Nuclear Agriculture Research Institute, Ghana Atomic Energy Commission, Accra P.O. Box LG 80, Ghana

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8602-8976

Affiliation:

1Department of Bacteriology, Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, Accra P.O. Box LG 581, Ghana

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5641-0274

Affiliation:

4Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire, Abidjan 01 BP 1303, Côte d’Ivoire

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4190-8202

Explor Foods Foodomics. 2025;3:1010105 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eff.2025.1010105

Received: November 06, 2025 Accepted: December 10, 2025 Published: December 21, 2025

Academic Editor: Gloria Sanchez Moragas, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Spain

Aim: Foodborne non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) infections are a major global health issue, frequently linked to animal source foods. However, there is limited data on NTS prevalence, distribution, and serotype diversity in common animal products and related food in Ghana. This study investigated the prevalence and serotype diversity of NTS in animal source foods, ready-to-eat (RTE) food, and animal fecal samples across six districts in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana.

Methods: A total of 696 samples were randomly collected from selected markets across the districts. These included unprocessed animal products: beef (16), chicken (21), eggs (185), and raw cow milk (40). Additionally, 50 samples of RTE street foods and 36 samples of locally produced soft cheese (“wagashie”) were obtained from vendors. Fecal samples consisted of chicken droppings (70) and pig feces (138), which were purposively collected from 11 poultry farms and two pig slaughter facilities in the region. Furthermore, 140 pork samples were purposively collected from the slaughter facilities. Standard microbiological methods, including pre-enrichment, selective enrichment, and plating on selective media, were used for Salmonella species isolation, with identification confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Serotyping followed the White-Kauffman Le-Minor classification scheme.

Results: Overall, 26 Salmonella isolates were recovered (3.7%). Prevalence was significantly higher in animal source foods (5.71%; 25/438) compared to fecal samples (0.4%; 1/208) (p = 0.0026). Salmonella contamination was highest in raw pork (13.6%), followed by “wagashie” (5.5%) and raw milk (5%). Nine distinct serotypes were identified. Among them, Salmonella Typhimurium was the most prevalent, accounting for 40.9%, followed by Salmonella Kaapstad at 13.6%. Additionally, pork samples contained seven of these serotypes.

Conclusions: These findings highlight a potential risk posed by NTS in commonly consumed animal source foods in Greater Accra and emphasize the need for targeted interventions to control contamination, particularly in pork products.

Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) is a predominant etiological agent of foodborne disease globally, contributing substantially to public health challenges and economic losses [1]. Globally, NTS is responsible for 93.8 million cases of foodborne illness each year, with an estimated 94% of salmonellosis cases attributed to contaminated food [2]. Unlike typhoidal strains, which are primarily associated with systemic infections in humans, NTS encompasses a diverse group of Salmonella enterica serotypes that cause self-limiting gastroenteritis but can also lead to invasive disease, particularly in vulnerable populations [3].

The primary reservoirs for NTS are animals, and transmission to humans occurs mainly through consumption of raw or contaminated food of animal origin, such as poultry, beef, pork, eggs, and dairy products [2, 4]. However, person-to-person contact, contact with pets, rodents, and amphibians, and environmental exposures have been reported [5–7].

The diversity of NTS serotypes is remarkable, with S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis being among the most prevalent worldwide [8]. In Africa, S. Typhimurium is the predominant strain, commonly associated with beef and poultry, whereas S. Enteritidis is more frequently linked to chicken and egg products. Other serotypes, such as S. Infantis, S. Newport, S. Dublin, S. Heidelberg, and S. Weltevreden, contribute significantly to the global burden of NTS, each exhibiting unique geographic and food source associations [2]. There is a significant knowledge gap regarding the distribution of Salmonella serotypes in Ghana, primarily due to limitations in serotyping capabilities. Consequently, most studies only identify Salmonella isolates at the species level, leaving detailed strain information largely unexplored.

In Africa, the burden of NTS is disproportionately higher compared to other regions, reflecting challenges in food safety, surveillance, and public health infrastructure [9]. A systematic review and meta-analysis covering 27 African countries highlight the widespread prevalence of NTS in food animals and animal-derived products, particularly in poultry, cattle and pigs, which are major sources of protein in many African diets [10]. The intensification of commercial meat production in Africa, while offering economic benefits, also increases the risk of foodborne outbreaks if food safety practices are not adequately enforced.

NTS remains a significant but underreported food safety issue in Ghana. Salmonella serotypes have been isolated from a variety of food sources, including beef, raw cow milk, poultry, and vegetables [4, 11]. Studies have reported Salmonella prevalence rates ranging from 1% to as high as 73% in different food matrices, with the highest rates observed in ready-to-eat (RTE) salads and raw animal products [11]. However, the true burden of NTS in Ghana is likely underestimated due to limited surveillance systems and underreporting of foodborne disease outbreaks [4, 11]. A substantial proportion of Ghanaians obtain meat from local open-air markets, where butchers and vendors display fresh meat under ambient conditions. This practice often results in prolonged exposure of meat to environmental contaminants and microbial agents. These markets are often central to the local economy and a place where people can find various goods and services. Market-based surveillance of food products for Salmonella is ideal for the identification of potential sources of contamination and tracking the prevalence of different Salmonella serotypes.

Continuous integrated surveillance of Salmonella serotypes using a One Health approach between animals and environment is vital for risk assessment, outbreak identification, tracking regional trends, and formulating targeted interventions [12]. Collectively, this information enhances the effectiveness of food safety and public health strategies, thus contributing to a reduction in the incidence of Salmonella infections within affected communities in the country. The study sought to determine the prevalence and distribution of Salmonella serotypes in various animal-source food and products, RTE foods that contained animal products, as well as fecal samples from informal markets, farm environments and slaughter facilities within selected districts in Accra, Ghana to provide a baseline data on the Salmonella serotypes.

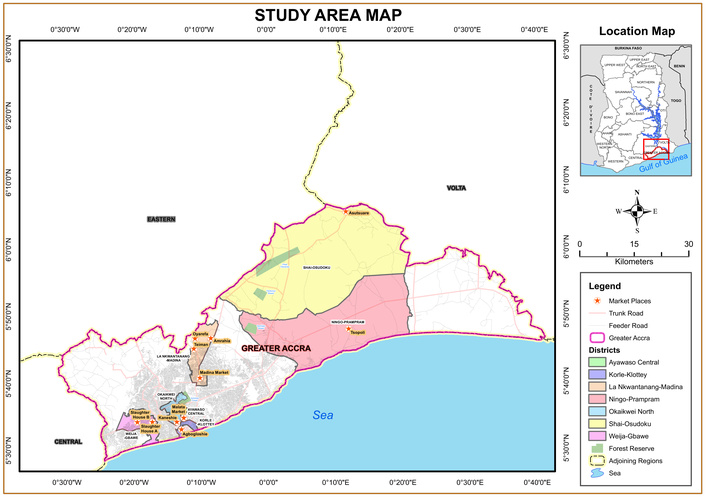

This study was conducted across nine selected markets, 11 livestock farms, and 2 slaughter facilities in six Metropolitan, Municipal and District assemblies (MMDAs) in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana, namely: Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA-Kaneshie and Agbogbloshie market), Ayawaso Central Municipal Assembly (Mallam Atta market), Weija/Gbawe Municipal Assembly (Gbawe slaughterhouse), La Nkwantanang Madina Municipal Assembly (LaNMMA), Shai-Osudoku (Asutsuare and Akuse markets), and Ningo-Prampram Districts (Tsopoli and Ningo Ahwiam market) (Figure 1). The Municipal Assemblies were chosen based on the popularity of the market, population density, and foodborne disease outbreak reports where these districts recorded a significant number of cholera and other diarrhoea cases [13].

Map of the Greater Accra Region, indicating the selected markets, farms, and slaughter sites where samples were collected. Source of map: University of Ghana.

The study was cross-sectional and included microbiological analysis of food and fecal samples. Samples of unprocessed animal source foods (beef, pork, chicken, eggs, raw cow milk), locally produced soft cheese referred to as ‘wagashie’ and RTE street food containing animal products were sampled from various market vendors. Fecal samples were collected from poultry farm environments and pig slaughter facilities in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana.

Six hundred and ninety-six (696) food and fecal samples were collected between January 2020 and June 2022. Sample size was calculated to estimate the prevalence of Salmonella with 95% confidence and a margin of error of ± 5%, using the Cochran formula; n = Z2p(1 − p)/d2, (Z = 1.96, d = 0.05). In the absence of directly comparable prevalence for animal-sourced foods in the study area, we used a previously reported prevalence of 44% [14], which sampled chicken and farm environments, as the best available estimate. This yielded an initial required sample size of 379. To account for the clustered sampling design (assumed design effect = 1.5) and an anticipated 10% sample loss, the final target sample size was increased to 696. Per the sampling plan of Ghana Standards Authority (GSA) microbiological criteria for food sampling, which is accredited to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission, ISO/IEC 17025 [15], at least five sample units were collected from each site. Unprocessed animal source food included beef (16), pork (140), chicken (21), egg (185), and raw cow milk (40). A total of 50 RTE street foods including mixed vegetable and meat salad, locally made millet porridges served with milk or fried “wagashie”, noodles with fried or boiled egg, packaged food such as chicken, beef, fish wrap, sandwiches, waakye (cooked rice with beans and served with meat), and jollof rice (cooked rice in tomato stew with species and meat) as well as “wagashie” (36) were purchased from randomly selected vendors. Fecal samples consisting of chicken droppings (70) and pig feces (138) were collected from 11 poultry farms and two slaughter facilities, respectively.

The composite fecal grab method was used to collect chicken fecal samples. For caged birds, approximately 10 g of fresh feces from a cage housing 10–15 birds were pooled using gloved hands into a sterile 50 mL Falcon tube and labeled. For floor-reared chickens, individual droppings were collected from multiple locations using a sterile cotton swab, pooled, and labeled accordingly. Approximately 5 g of pig fecal matter were aseptically collected from the rectum using a sterile swab immediately after the intestinal tract was opened post-slaughter. All food and fecal samples were transported in cold boxes to the Department of Bacteriology of the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, for microbiological analysis.

Samples were cultured on standard microbiological media to isolate and identify Salmonella spp. The specific laboratory procedures performed were pre-enrichment, enrichment, and culture on selective agar. Identification of Salmonella spp. was done using the matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI–ToF) mass spectrometry. Serotyping of isolates was conducted to determine the serotypes of Salmonella identified.

Pre-enrichment and selective enrichment cultures, and isolation of Salmonella were performed following ISO 6579: 2017 protocol. Briefly, 25 g of solid samples, such as meat and vegetables, and 25 mL of raw milk were homogenized in 225 mL sterile buffered peptone water (BPW) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK, CM1049) using a stomacher (Enizer 400) for 3 minutes. A pool of five eggs was collected into a sterile stomacher bag and washed gently with 225 mL of BPW to obtain a homogenate. For fecal samples, swabs were inserted into 9 mL of selenite fecal broth (Oxoid, CM0395). The homogenate and broth were incubated at 37 ± 1°C for 18 to 24 hours to obtain pre-enriched cultures. A 100 µL loopful of the enriched culture was transferred to 10 mL Modified Semi solid Rappaport Vassiliades (MSRV) agar, and 10 µL selective Müller-Kauffmann tetrathionate novobiocin enrichment broth (MKTTn) (Oxoid, CM0343) supplemented with iodine iodide and incubated at 40.5–42.5°C and 37°C for 24 h, respectively. A ten (10) µL loopful of the enrichment broth was streaked on Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD) agar (Oxoid, CM0469) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

Approximately four to five distinct presumptive Salmonella colonies, exhibiting a slightly transparent red halo with a black center surrounded by a pink-red zone, observed on each XLD agar plate, were identified. These colonies were then streaked onto nutrient agar (Oxoid, CM0003) and incubated for 24 hours at 37 ± 1°C to obtain pure isolates. The urease test was conducted on all pure isolates by inoculating five well-isolated colonies of presumptive Salmonella into urea broth (HiMedia, Kennett Square, PA, USA, M111) and incubating at 37 ± 1°C for 24 hours. All isolates that displayed a negative urease reaction were selected for confirmation using MALDI–TOF.

Fresh overnight pure colonies of presumptive Salmonella isolates, obtained by subculturing on Nutrient Agar and incubating at 37 ± 1°C, were used for MALDI–ToF identification. Briefly, a single colony from each isolate was applied directly to a MALDI–ToF target plate (MSP 96 polished steel plate) using a sterile wooden applicator. The sample was allowed to air-dry for approximately 10 minutes, after which 1 µL of matrix solution (10 mg/mL α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, CHCA) was overlaid and allowed to air-dry again. The prepared target plate was then inserted into the MALDI–ToF vacuum chamber (Bruker, Biotyper 3.1 software, Germany), where the charge-to-mass ratio of ribosomal proteins was measured to generate a unique spectral profile. The resulting spectra were compared against a reference database to predict isolate identification. Results were interpreted according to the manufacturers’ guidelines: a score ≥ 2.3 indicated a reliable species-level identification, 2.0–2.29 indicated a probable species-level identification, 1.7–1.9 indicated a probable genus-level identification, and a score < 1.7 was considered unreliable.

All identified Salmonella isolates were serotyped using the conventional slide agglutination method [16]. Commercial polyvalent antisera O, Vi, and monovalent antisera A, B, C1, C2, D, E (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) were used to group the isolate and confirm NTS.

Two homologous suspensions were made, one test and one control, by suspending a pure isolate and the control strain in a drop of sterile physiological saline on a slide. O antisera was added to each, rocked gently for a minute, and examined for agglutination. A positive reaction was observed within a minute on the control slide, which was then used to confirm the test slide results. A delayed or partial agglutination was considered negative. Fresh Salmonella isolates, cultured overnight on Luria Bertani (LB) Agar (Oxoid, CM1018) at 37°C, were used for serotyping, with S. Typhimurium ATCC 14028 serving as a positive control.

The H antigen for flagella was determined as follows: All positive polyvalent O Salmonella isolates were tested for polyvalent H phase 1 and phase 2 antigens by Slide agglutination. Phase 1H and 2H antigens were detected using Salmonella polyvalent antiserum A–G and phase inversion (SG1 to SG6) (BIO-RAD, USA). Slide agglutination was performed using the same procedure described for O antigen testing. Isolates that tested positive for any of the polyvalent antiserum (A–G) were tested again with individual monovalent H antiserum. After phase 1 testing to identify the H antigen, a phase inversion was performed to allow the organism to express the dominant H phase and grow in phase 2 [16].

Isolates that exhibited agglutination with monovalent H antisera underwent phase inversion using the Sven Gard method. This involved adding phase inversion antisera to molten swarm agar in sterile Petri dishes, inoculating a colony at the center, and incubating at 37°C for 24 hours. Strains that displayed swarming were selected for phase 2 testing, which involved a slide agglutination test with cultures from the Swarm Agar periphery using phase 1 H polyvalent antisera. Isolates that did not agglutinate indicated a single phase, while those that did were further defined using specific monovalent antisera. Serotypes were assigned with reference to the Kauffman-White catalog [16].

Data was analyzed using Microsoft Excel 16 and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 18). Graphs were drawn using charts. Frequency of Salmonella spp. isolation between sample types was compared using Chi-square test. Differences in the proportion of samples positive for Salmonella spp., or Salmonella serotype per food type, or between districts were compared using a 95% confidence interval, and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A total of 26 Salmonella spp. were isolated from the 696 samples, representing an overall prevalence of 3.7% (p = 0.0374). A significantly higher prevalence of 5.71% (25/438) was observed in animal-source food (p = 0.0026) compared to 0.4% (1/208) observed in fecal samples. Among samples that were positive for Salmonella, the highest prevalence was observed in fresh pork (73.1%, 19/26), followed by raw milk, “wagashie” and egg (7.7%, 2/26 each). Similarly, among the animal-source foods, fresh pork recorded the highest prevalence of 13.6%. No Salmonella sp. was isolated from RTE, beef, raw chicken, and chicken feces (Table 1).

Salmonella spp. isolated from food and fecal samples.

| Sample | Specimen type | Number of samples | Number of samples positive for Salmonellan (%) | p-value (within groups) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food of animal origin | Raw cow milk | 40 | 2 (5) | 0.0026 (χ2 = 11.616) |

| Wagashie (local cottage cheese) | 36 | 2 (5.5) | ||

| Eggs | 185 | 2 (1.1) | ||

| Pork | 140 | 19 (13.6) | ||

| Beef | 16 | 0 | ||

| Chicken | 21 | 0 | ||

| RTE | Vegetable salad, grilled meat, rice meals, etc | 50 | 0 | |

| Animal faeces | Chicken | 70 | 0 | 0.0046 (χ2 = 6.650) |

| Pig | 138 | 1 (0.72) | ||

| Total | 696 | 26 (3.7%) |

χ2: Chi square score; RTE: ready-to-eat.

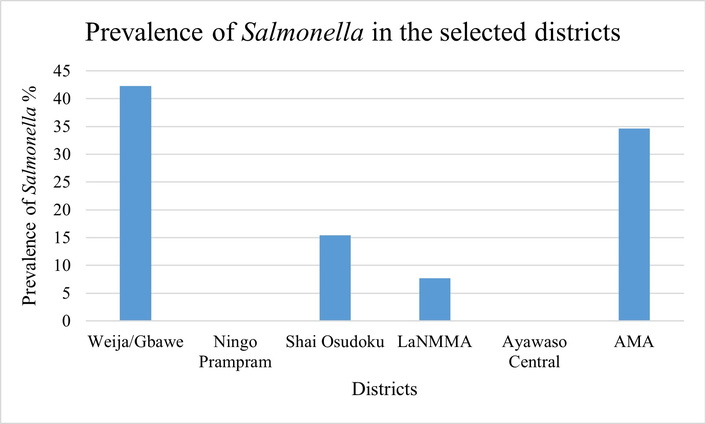

Salmonella spp. were isolated from samples from four out of the six districts surveyed in this study. These districts included the LaNMMA, Accra Metropolitan Area, Weija/Gbawe (all more urban), and Shai Osudoku (more rural). The prevalence was 42.3% in Weija/Gbawe, 34.6% in the Accra Metropolitan Area, 15.4% in Shai Osudoku, and 7.7% in LaNMMA (Figure 2). Notably, no Salmonella were isolated from samples collected from the Ayawaso Central (highly urbanized) and Ningo-Prampram (rural district that is undergoing rapid urban expansion).

Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in samples from the six districts in the Greater Accra Region. LaNMMA: La Nkwantanang Madina Municipal Assembly; AMA: Accra Metropolitan Area.

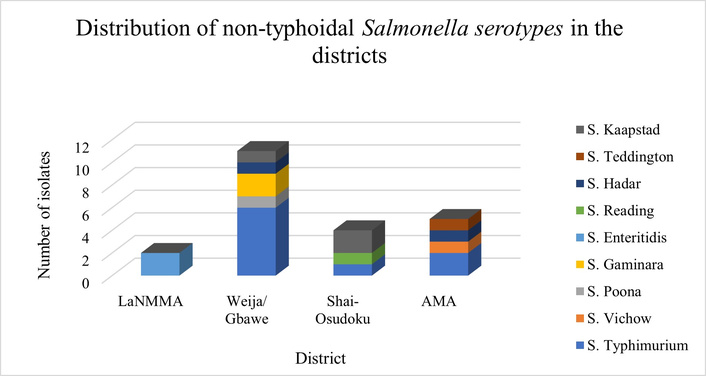

Of the 26 Salmonella isolates recovered, three isolates from pork and one from pig fecal samples were non-typeable. Among 22 typeable isolates, nine distinct serotypes were identified (Table 2). Majority of isolates belonged to serogroup B (63.6%, 14/22). Within this group, S. Typhimurium (40.9%), S. Kaapstad (13.6%), S. Reading (4.5%), and S. Teddington (4.5%) were detected. Serogroups C1 and G each accounted for 4.5% of isolates, represented by S. Virchow and S. Poona, respectively. Serogroups C2, D, and I each constituted 9.1% of isolates, comprising S. Hadar, S. Enteritidis, and S. Gaminara, respectively. Seven serotypes, including S. Typhimurium (8 isolates), S. Kaapstad (1), S. Gaminara (2), S. Virchow (1), S. Teddington (1), S. Hadar (2), and S. Poona (1), were detected from pork samples compared to two serotypes each: S. Kaapstad and S. Reading in raw milk, S. Kaapstad and S. Typhimurium in ‘wagashie’ and one serotype S. Enteritidis in raw table eggs (Table 2).

Serotype diversity and distribution of non-typhoidal Salmonella in animal source food/products.

| Serogroup | Serotype | Antigenic formula | Source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cow milk | Wagashie | Egg | Pork | Total | |||

| B | S. Typhimurium | 4:i:1,2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 9 (40.9%) |

| S. Kaapstad | 4:e,h:1,7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 (13.6%) | |

| S. Reading | 4:e,h:1,5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.5%) | |

| S. Teddington | 4:y:1,7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (4.5%) | |

| C1 | S. Virchow | 7:r:1,2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (4.5%) |

| C2 | S. Hadar | 8:z10:e,n | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (9.1%) |

| D | S. Enteritidis | 9:g,m | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (9.1%) |

| G | S. Poona | 13:z:1,6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (4.5%) |

| I | S. Gaminara | 16:d:1,7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (9.1%) |

| Total | 2 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 22 | ||

Isolates recovered from samples collected from the Weija/Gbawe district had the highest diversity of five out of the nine serotypes identified: S. Gaminara, S. Typhimurium, S. Hadar, S. Kaapstad, and S. Poona. This was followed by the Accra Metropolitan Area, where four serotypes were detected: S. Typhimurium, S. Virchow, S. Hadar, and S. Teddington (Figure 3). In contrast, samples from LaNMMA had the least diversity, with only one serotype, S. Enteritidis, identified. Of the six districts, these three have the highest population. Notably, S. Typhimurium was the most predominant serotype among isolates from Weija/Gbawe district, accounting for 66.7% of isolates in this district, which houses the largest abattoir exclusively for pigs, from where most of the pork samples were collected.

Distribution of non-typhoidal Salmonella serotypes within the selected districts of the Greater Accra Region. LaNMMA: La Nkwantanang Madina Municipal Assembly; AMA: Accra Metropolitan Area.

In sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Ghana, NTS is the leading cause of gastroenteritis and invasive salmonellosis [17, 18]. This study provides important epidemiological insights into the prevalence, serotype diversity, and distribution of NTS in animal source food, RTE foods, and animal fecal samples from various districts within the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. By sampling both raw and RTE foods, the study offered a more comprehensive picture of Salmonella prevalence across the food chain. This approach aligns with One Health surveillance principles, which emphasize integrated monitoring across food, environment, and human exposure pathways.

This study found an overall Salmonella prevalence of 3.7%, with 5.71% in unprocessed animal source food and 0.4% in animal feces. Salmonella was not isolated from any of the RTE foods sampled. Previous studies in Africa have reported comparable Salmonella prevalence in animal source food, ranging from 4.0% in Nigeria [19], 5.5% in Ethiopia [20], 7.3% in Ghana [21], and 8.8% in North Africa [22]. However, other studies have reported a much higher prevalence, including 16–20% in Ethiopia [23] and 34.2% in Bangladesh [24]. For food borne pathogens like Salmonella, prevalence could be influenced by several factors including cross-contamination and poor hygiene during food processing and handling. This notwithstanding, the findings support the existing knowledge that animal-source foods are an important vehicle for transmission of foodborne pathogens [2]. Although raw animal products are the primary reservoirs of Salmonella, consumers are ultimately exposed through foods that are eaten without further cooking. Therefore, evaluating both raw and finished products provides a more complete understanding of the food safety risks along the value chain and helps determine whether contamination occurs before or after processing. This inclusion strengthens the public health relevance of the study by capturing the actual risk to consumers.

Salmonella is a prominent foodborne pathogen globally, often associated with poultry products [25, 26]. However, in this study, no Salmonella sp. was isolated from either chicken carcasses or chicken fecal samples, which is consistent with previous findings in Egypt [27] but contrary to an earlier study in Ghana, where a higher Salmonella prevalence of 61% in chicken carcasses [28] and 6% in the poultry environment was reported [6]. The variability in findings could be due to different methodologies employed, study locations, poor hygiene and biosecurity, and cross-contamination [29]. This study employed well-established methods for sampling fecal matter, involving the collection of fresh droppings and homogenization. Laboratory techniques included enrichment in BPW, selenite broth, and tetrathionate broth. XLD agar, which is sensitive for isolating Salmonella even in heavily contaminated samples with other Enterobacteria [30], was the culture media. All presumptively identified bacteria were confirmed with MALDI–ToF Biotyping. The absence of Salmonella in the fecal samples may also be attributable to low-level or intermittent shedding by the birds at the time of sample collection, resulting in bacterial loads below the detectable threshold [29].

Salmonella spp. was detected in 1.1% of eggshells of raw table eggs sampled from retail markets, mirroring a similar prevalence reported in Chile [31]. This finding differs from a previous study in Ghana, which reported a prevalence of 4.9% in eggshells [4]. In comparison, some studies have reported higher prevalence rates, such as 7.4% in South Korea [32], 15.6% in India [33], 14% in Nigeria [34], and 88.6% in Cameroon [35]. In the present study, it was observed that the footwear and equipment of farmers and attendants were disinfected before entry and upon exiting the cages and pens. This practice was to prevent the transmission of bacteria and other microorganisms between poultry housing units and the external environment. Although we did not assess the effectiveness of hygiene practices at the farm level, the low Salmonella prevalence reported in this study, could be attributable to this practice as well as the use of disinfectants during egg handling by the farmers, Despite the possibility of contamination of both the eggshell and the content, the current study assessed the prevalence of Salmonella spp., from only the eggshell because of the link between contamination of the eggshell and the risk of cross-contamination during consumer handling in the environment.

In this study, the prevalence of Salmonella spp., in pork was 13.6% which is lower than the 29.1% prevalence reported in Ethiopia [36], 37% in China [37], and 40% in Uganda [38], but higher than the 2.7% in Europe [39]. In contrast, countries like Sweden, Finland, and Norway, that adhere to strict EU trade standards, have reported much lower prevalence rates, often below 0.04% [40]. Pigs are asymptomatic carriers of NTS and can shed the bacteria in the farm and abattoir during processing of the carcass. Poor sanitation practices in animal husbandry, coupled with substandard hygiene conditions in abattoirs, may contribute significantly to the deterioration of carcass quality. This problem was common within the framework of our research.

It is important to note that the high prevalence of Salmonella spp. in pigs reported in the Weija/Gbawe district, as observed in this study, may be influenced by the sampling approach. Specifically, all pork and pig fecal samples were collected exclusively from the two largest slaughterhouses in the district, which supply pork to vendors and consumers throughout the region [41]. Due to cultural differences, particularly among Muslim communities, Christian denominations, and other tribes that do not consume pork, not all slaughterhouses in the study area process pigs, which may affect the representativeness of the sampling. In general, the four districts where Salmonella spp. were isolated represented a mix of urban and rural districts; hence, no association could be established.

Salmonella prevalence of 5% and 5.5% was observed in raw cow milk and locally produced soft cheese (wagashie), respectively. These findings are comparable to the 6% recorded in Ethiopia [20] and 6% in Ghana [21] but higher than the 1% in studies in New York, USA [42] and 0% in Ghana [43]. All cattle farmers in this study were observed milking their cows in the kraals, with fecal matter on the floor and sometimes on the udder prior to hand milking. The unclean milking environment and equipment, poor udder preparation, and hygiene of milk handlers observed in the study area could account for the higher prevalence. It is important to note that the Salmonella prevalence in the raw cottage cheese “wagashie” was lower than the 24% reported in an earlier study [21]. This study did not sample fried “wagashie”, which is usually how it is sold in the informal markets. However, Adzitey et al. [29], whose work compared the levels of Salmonella contamination in fried and raw wagashie, reported a significant reduction in the level of contamination in fried wagashie [21]. Thus, frying or cooking milk products and pasteurization of raw milk significantly reduced the level of or eliminated harmful pathogens.

Thermal processing methods such as frying, grilling, and smoking are highly effective in eliminating foodborne pathogens like Salmonella spp., thereby ensuring the microbiological safety of food products [44]. This effectiveness likely explains the absence of Salmonella spp., in all RTE food products examined in this study, consistent with previous findings reported in South Africa [45] and Iran [46]. In contrast, other studies from Ghana [47] and Colombia [48] documented higher Salmonella prevalence rates of 60% and 52%, respectively, in similar RTE food matrices. These higher contamination levels were attributed primarily to direct and indirect cross-contamination resulting from inadequate handling practices by food handlers. Per the national and international standards for food safety, Salmonella should not be present in any 25 g of food; however, 5.71%, representing 25 out of the 438 food samples from animal sources, were contaminated. The presence of Salmonella spp. in the food samples analyzed in the present study may present a public health concern and a food safety issue, especially when food is eaten raw or undercooked, or when there is cross-contamination. This suggests non-compliance with food safety standards and practices in the country.

S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis are reported to be the most frequently occurring Salmonella serotypes in food commodities and human samples in Africa [22, 21, 28, 49]. These serotypes have been associated with invasive NTS (iNTS) infections in children and immunocompromised adults in sub-Saharan Africa [17] and Europe, where they were also responsible for over 70% of reported human salmonellosis [50].

In this study, nine serotypes were identified, with S. Typhimurium (40.9%) being the most predominant. This aligns with findings from previous studies in Ghana and Europe [28, 51]. S. Typhimurium and Enteritidis are generalist pathogens, infecting a wide range of hosts, including humans, pigs, and poultry. Their broad host range stems from virulence genes on Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs) and virulence plasmids, which enable bacterial invasion and immune evasion. Key SPIs, particularly SPI-1 and SPI-2, facilitate intracellular survival and enhance adaptability across species [52].

S. Enteritidis was detected only in egg samples, despite its generalist nature and ability to infect multiple hosts [22]. It is predominantly associated with poultry and eggs and is a major contributor to global outbreaks [53]. Archer et al. [4] identified five serotypes in table eggs from three regions in Ghana, mostly S. Chester and S. Hadar, with a few S. Enteritidis [4]. Our study, limited to only the Greater Accra Region, found lower serotype diversity in eggs (only S. Enteritidis), possibly reflecting regional variation. As a zoonotic strain, S. Enteritidis causes significant economic losses in animal husbandry and poses risks to public health and economic development [54].

The highest number of serotypes (7/9), S. Typhimurium, Kaapstad, Gaminara, Poona, Teddington, Virchow, and Hadar was found with pork samples. Yet this was far lower compared to studies in Malawi and Kenya, where 32 serotypes were identified in pigs and their environment [55]. Pigs can become asymptomatic carriers of the bacterium after infection and persist for up to 28 weeks in the tonsils and mesenteric lymph nodes until they are shed intermittently in their feces [56]. In the soil, they persist for up to 14 days, where they can infect piglets and handlers. In the present study, there was a higher prevalence of Salmonella in pigs’ than in the fecal samples. The low (0.4%) prevalence in fecal samples may reflect intermittent shedding or sampling limitations, as noted in a study [57].

The detection of Salmonella serotypes Poona, Germinara, and Teddington exclusively in pork samples is noteworthy, as these serotypes are generally regarded as environmental in origin and are more frequently implicated in the contamination of fresh produce, particularly fruits [53]. Their presence in pork may reflect indirect contamination routes rather than primary colonization in swine. Possible pathways include contact with contaminated water, soil, or surfaces during slaughter and processing, or cross-contamination from produce or feed ingredients within the production chain. The study found S. Virchow and S. Hadar only in pork, though these serotypes are typically linked to poultry outbreaks [53]. They have also been isolated from broiler farms and slaughterhouses in Ghana, Algeria, and Australia [7, 14]. It remains unclear whether contamination arose from pig lairage exposure or cross-contamination from poultry farms due to poor biosecurity.

S. Kaapstad, the most “unrestricted” serotype, was present in one pork sample, one raw wagashie, and one raw milk sample. Previous studies in Ghana have reported the isolation of this serotype from poultry, beef, and mutton [14, 58, 59]. This serotype was first isolated in 1973 from milk on a UK dairy farm, pig slaughterhouses, and consumers of unpasteurized milk from the farm [60]. It is known to cause mild gastroenteritis and invasive infections such as osteomyelitis in humans. There is limited data on its public health impact in Ghana, and it is not currently listed among globally recognized Salmonella serotypes of public health importance. However, its presence and diversity in foods of animal origin warrant a comprehensive investigation to inform surveillance purposes.

While we used a robust sample size, our study may be limited by selection bias inherent in a cross-sectional study design, warranting the need for a longitudinal study to fully capture trends in Salmonella prevalence across the seasons in Ghana. The sample size estimation was based on a 44% prevalence reported in an earlier study, which was derived from chicken and farm environment samples rather than the various animal-sourced foods that this study sampled from. While this represented the best available local estimate, it may not fully capture the true prevalence in the target population of this study. Nevertheless, the use of data from a different sampling frame introduces some uncertainty, and the findings should be interpreted within this context. Our study initially aimed to collect equal numbers of samples (20 per food category) across all sites. However, the final sample numbers reflect practical constraints and availability, rather than deliberate prioritization of food types. In several markets, meat products, especially beef and pork, were either unavailable at the time of sampling or vendors declined participation, limiting the number of meat samples we could obtain. Conversely, eggs were widely available, and vendors were generally more willing to participate, which allowed us to achieve a higher sample count in this category.

Insights into genetic diversity, risk factors, and transmission dynamics of Salmonella strains in food-producing animals were not explored in this study, but future studies could employ a molecular epidemiological approach using whole-genome sequencing.

The data collected between January 2020 and June 2022 provides a valuable baseline for understanding patterns of bacterial prevalence within the study period, particularly in settings where longitudinal surveillance is scarce.

This study provides critical insights into the prevalence and serotype diversity of NTS in animal source foods and selected RTE products in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. The significantly higher contamination rates observed in raw pork, soft cheese (‘wagashie’), and raw milk underscore the potential risk these products pose to consumers. The predominance of S. Typhimurium, a serotype frequently implicated in human salmonellosis, reinforces the zoonotic and foodborne transmission potential of NTS in the region. Although fecal samples showed low prevalence, the detection of diverse serotypes in food products highlights the need for enhanced surveillance across the food production and distribution chain. These findings support the implementation of targeted food safety interventions, improved hygiene practices, and integrated One Health approaches to mitigate the burden of NTS infections in Ghana.

BPW: buffered peptone water

LaNMMA: La Nkwantanang Madina Municipal Assembly

MALDI–ToF: matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight

NTS: non-typhoidal Salmonella

RTE: ready-to-eat

XLD: Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate

The authors sincerely thank the livestock farmers and abattoir staff who generously participated in this study. Their cooperation, openness, and support during sample collection were invaluable to the success of the research.

VYA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. GIM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. BTO: Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. TYA: Resources, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. KKA: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Validation. BB: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Scientific and Technical Committee and the Institutional Review Board of the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana (Reference number: NMIMR-IRB103/17-18).

All food samples were purchased at the point of sale, except for pork. Pork and pig fecal matter samples were collected from slaughterhouse owners who voluntarily provided informed consent for sampling.

Not applicable.

Data sets are available on request.

This study was funded by The Science for Africa Foundation to the Developing Excellence in Leadership, Training and Science in Africa (DELTAS Africa) program (Afrique One-ASPIRE), [Del-15-008 and Afrique One-REACH, Del-22-011] with support from Wellcome Trust and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office which is part of the EDCTP program supported by the European Union. The funding sources had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 766

Download: 78

Times Cited: 0