Affiliation:

Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-1170-2868

Affiliation:

Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia

Email: shori_7506@hotmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7557-3987

Explor Foods Foodomics. 2025;3:1010107 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eff.2025.1010107

Received: July 22, 2025 Accepted: December 05, 2025 Published: December 25, 2025

Academic Editor: Josep Rubert, Wageningen University, the Netherlands

Gut microbiota is critical for human immunity, metabolism, and overall well-being. Dysbiosis has been associated with a variety of diseases, including metabolic syndrome, inflammatory diseases, and neurodevelopmental issues. Kefir, a traditional fermented beverage produced with dairy or non-dairy substrates and kefir grains, contains probiotics and bioactive substances that may improve gut microbial composition. Current research indicates that kefir increases beneficial taxa such as Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., and Akkermansia spp., whereas decreasing pro-inflammatory microbes such as Enterobacteriaceae spp. and Clostridium spp. via antimicrobial metabolite production, competitive exclusion, prebiotic exopolysaccharides, short-chain fatty acid enhancement, immune modulation, and improved gut-barrier integrity. Furthermore, traditional kefir fermented with grains has higher microbial diversity and probiotic potential than kefir fermented with starting cultures. Despite these encouraging results, interpretation is constrained by variations in kefir production, dosage, intervention duration, and microbiota analysis methods; therefore, this review aims to evaluate how kefir modulates gut microbiota composition in human and animal models.

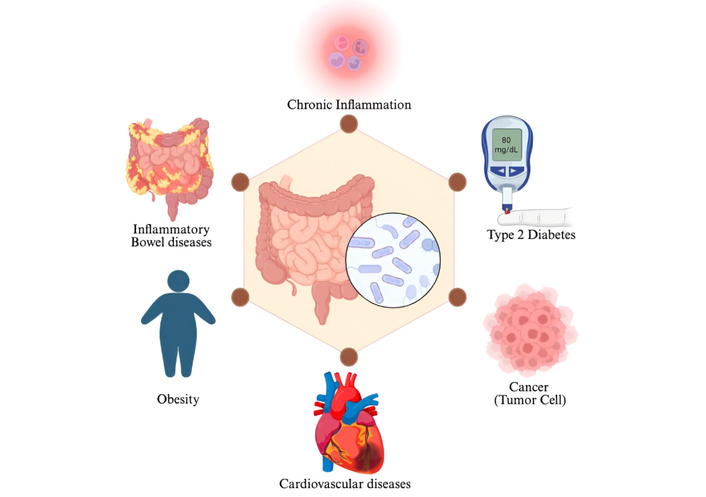

Alterations in gut microbiota composition have been strongly associated with numerous chronic disorders, including metabolic disorders, inflammatory bowel diseases, cardiovascular conditions, obesity, diabetes, and certain types of cancer [1–4]. The gut microbiota plays an essential role in immune maturation, nutrient metabolism, and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis [5, 6]. Disruption of this balance from eubiosis to dysbiosis has been associated with disease development via inflammation, decreased metabolic signaling, and changed microbial community structure (Figure 1) [7–9]. Several studies suggest that restoring microbial equilibrium through targeted dietary interventions may contribute to the prevention or mitigation of microbiota-related disorders [10].

Gut dysbiosis and its association with multiple diseases. Created in BioRender. Alali, MA (2025) https://BioRender.com/f3psomq

As global interest in evidence-based functional foods continues to grow, probiotics have garnered considerable attention due to their clinically demonstrated health benefits. The Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization (FAO/WHO) define probiotics as live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit to the host [11]. Among these, species of the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are the most commonly utilized because of their well-documented safety and compatibility with the gastrointestinal (GI) environment [12]. These characteristics support the therapeutic potential of fermented foods such as kefir, which naturally contains a variety of probiotic bacteria and yeasts.

Growing scientific interest has shifted from single-strain probiotics to complex fermented foods that naturally deliver diverse microbial communities. Kefir has attracted particular attention due to its unique combination of bacteria, yeasts, and bioactive metabolites, which distinguish it from other fermented dairy beverages. Unlike single-strain probiotics, kefir represents a dynamic ecosystem capable of modulating gut microbial composition and metabolic activity. However, clinical outcomes remain variable, partly due to differences in manufacturing processes, grain composition, dosage, and host-specific responses. These inconsistencies highlight the need for a comprehensive evaluation of current research on kefir’s effects on gut microbiota in both human and animal studies. Accordingly, this review aims to evaluate how kefir modulates gut microbiota composition in human and animal models.

Kefir is a naturally fermented beverage made by inoculating milk with kefir grains, which are a symbiotic matrix of bacteria and yeasts embedded in a polysaccharide network called kefiran [13, 14]. This multispecies community produces a diverse spectrum of bioactive metabolites, including organic acids, peptides, ethanol, carbon dioxide, and exopolysaccharides, which all contribute to kefir’s functional and physicochemical qualities [15]. Microbial metabolism during fermentation enhances the nutritional profile of the beverage by hydrolyzing lactose and releasing B vitamins (B1, B12, and folate), vitamin K, and essential minerals such as calcium [16, 17].

The production of kefir can be achieved using either dairy or non-dairy substrates, with milk-based versions being the most thoroughly studied [16]. Non-dairy kefir is gaining popularity as an alternative for individuals who are lactose intolerant, have milk allergies, or follow a plant-based diet [14, 18]. Although dairy and non-dairy kefir grains share broadly similar structural and microbiological characteristics, the composition and abundance of bacterial and yeast species vary markedly depending on the substrate type and its nutritional availability [14]. Typical production entails inoculating the chosen substrate with 1–20% (w/v) kefir grains and incubation for 18–24 hours at 20–25°C [13]. Microbial activity during fermentation increases grain biomass by 5–7% and produces organic acids, carbon dioxide, ethanol, and exopolysaccharides. After fermentation, the grains are separated and reused for subsequent fermentation cycles [13].

Kefir’s microbial composition, typically dominated by lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria, and yeasts, varies by geographical origin and is influenced by multiple factors, including the grain-to-substrate ratio, fermentation temperature and duration, and the degree of agitation [13]. Certain species, such as Lactobacillus spp., are prevalent across regions due to their ecological adaptability and recognized probiotic potential [15]. These microbial variations affect kefir’s sensory attributes, physicochemical characteristics, biological activities, and its associated health benefits.

The human small intestine is anatomically divided into three distinct regions: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Its primary physiological function is the digestion and absorption of nutrients [19]. Compared to the colon, the small intestine hosts a relatively lower microbial load, with an estimated density of 103 to 107 microbial cells per gram of intestinal content [20]. This reduced microbial abundance is largely attributed to its acidic pH, the presence of antimicrobial pancreatic enzymes, bile salts, and a rapid luminal transit, which limits microbial colonization and proliferation [20]. Despite these harsh conditions, certain microbial taxa have adapted to the small intestinal environment. The predominant phyla in this region are Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, which exhibit resilience against bile acids and fluctuating pH levels [21]. Genera such as Veillonella and Streptococcus thrive in the upper GI tract due to their metabolic flexibility and capacity to utilize available substrates [19].

In contrast, the large intestine, which includes the cecum, ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid segments of the colon, as well as the rectum, provides a highly favorable environment for microbial colonization due to its slower transit time and strictly anaerobic conditions [22]. This region harbors the densest microbial population in the human body, reaching up to 1012 microbial cells per gram [20]. The predominant bacterial phyla in the colon are Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, which together constitute approximately 90% of the total gut microbiota [22]. Notably, the relative abundance of these phyla, particularly the Bacteroidetes-to-Firmicutes ratio, can vary across different stages of life and has been associated with a range of health outcomes. At the genus level, the most prevalent taxa include Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Eubacterium, Clostridium, Propionibacterium, Peptostreptococcus, and Ruminococcus, all of which contribute significantly to gut homeostasis, fermentation processes, and host-microbe interactions [23].

Multiple clinical investigations have evaluated the effect of kefir consumption on gut microbiota across diverse human populations, health conditions, and kefir formulations (Table 1). Clinical studies by Bellikci-Koyu et al. [24], Öneş et al. [25], and Walsh et al. [26] have demonstrated that kefir intake increases beneficial taxa such as Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Roseburia, while decreasing potentially harmful groups including Proteobacteria and opportunistic species. In women with polycystic ovary syndrome, traditional kefir consumption promoted a more balanced microbial profile [27]. Likewise, critically ill intensive care unit (ICU) patients exhibited selective enrichment of Lactobacillus species after graded kefir administration [28].

Modulation of gut microbiota composition by kefir in human and animal models.

| Kefir preparation method | Sample type | Feeding dosage/administration | Experiment duration | DNA extraction | Organ used for microbial analysis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercially available kefir | Professional female soccer players, aged 18–29 years(n = 21) | 200 mL of kefir daily, through oral intake | 28 days | DiaRex® Stool Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Cat No.: SD-0323, Diagen, Ankara, Turkey) | Fecal samples | Öneş et al. [25] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| ↑ Akkermansia muciniphila, Bifidobacterium, SCFA-related genera (e.g., Roseburia)↓ Proteobacteria | ||||||

| Traditional kefir produced with grains by Danem, Inc. (kefirdanem.com, Suleyman Demirel University Technopark, Isparta, Turkey) | Women with PCOS, aged between 18 and 40 years(n = 17) | 250 mL/day of kefir, through oral administration | 8 weeks | DiaRex® Stool Genomic DNA Extraction Kit | Fecal samples | Çıtar Dazıroğluet et al. [27] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| ↑ Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Lactococcus-related taxa↓ Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Holdemania | ||||||

| Lifeway Foods® Kefir | ICU patients,(> 18 years)(n = 54) | 60 mL, followed by 120 mL after 12 h, then 240 mL of kefir daily, through oral or nasogastric administration | 4 weeks | Qiagen’s DNeasy 96 PowerSoil Pro QIA- cube HT Kit(QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA) | Fecal samples | Gupta et al. [28] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| ↑ Bacilli, Lactobacillus spp. (L. plantarum, L. reuteri, L. rhamnosus), Parvimonas and Dialister↓ Bifidobacterium longum | ||||||

| Kefir milk product (provided by Nourish Kefir) | Healthy volunteers, aged from 18 to 65(n = 9) | 247 mL/day of kefir, through oral intake | 28 days | QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN, UK) | Fecal samples | Walsh et al. [26] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| ↑ Lactococcus raffinolactis | ||||||

| Commercial kefir (the brand is not mentioned) | Angora cats, age: 3.3 ± 2.5 years old(n = 7; male: 5, female: 2) | 30 mL/kg/day of kefir, orally administered | 14 days | Selective media for total mesophilic aerobic bacteria, coliform bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus spp., Lactobacillus spp., Lactococcus spp., and yeast) | Fecal samples | Kabakçi et al. [31] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| ↑ Total mesophilic aerobic bacteria, Lactobacillus spp., Lactococcus spp., and yeast↓ Enterococcus spp. | ||||||

| Kefir grains were cultured in Irish whole full-fat cow’s milk | Male BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J mice, 5–6 months of age(n = 9) | 0.2 mL/day of kefir, through oral administration | 3 weeks | QiaAmp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | Cecal contents | van de Wouw et al. [29] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| ↑ Lachnospiraceae bacterium A2↓ Clostridiaceae and Clostridium | ||||||

| Kefir grains were independently cultured in Irish whole full-fat cow’s milk to prepare two distinct kefir types, Fr1 and UK4 | Male C57BL/6J mice, 8 weeks of age(n = 48) | 0.2 mL/day, through oral gavage | 3 weeks | Using QIAamp PowerFaecal DNA Kit | ileal, caecal, and faecal samples | van de Wouw et al. [30] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| Both kefir groups: ↑ Lactobacillus reuteri (caecum and faeces), Eubacterium plexicaudatum (faeces and caecum), Bifidobacterium pseudolongum (ileum and caecum)↓ Lachnospiraceae bacterium 3_1_46FAA (caecum), Propionibacterium acnes (faeces), Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (faeces)For Fr1 kefir group: ↑ Parabacteroides goldsteinii (caecum), Bacteroides intestinalis (faeces), Anaerotruncus spp. (faeces), Parabacteroides goldsteinii (faeces)For the UK4 kefir group: ↑ Alistipes spp. (caecum)↓ Candidatus Arthromitus spp. (ileum) | ||||||

| Kefir peptides (KPs), fermented goat milk with traditional kefir grains | Female C57BL/6J mice (ovariectomized model, simulating estrogen deficiency)(n = 6) | 0.1 mL/kg daily of KPs, through oral administration | 8 weeks | QIAamp PowerFecal DNA Kit (Qiagen, Redwood, CA, USA) | Cecal contents | Tu et al. [33] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| ↑ Alloprevotella, Anaerostipes, Parasutterella, Romboutsia, Ruminococcus, and Streptococcus | ||||||

| Sterilized milk was fermented with kefir grains | Healthy adult dogs, 5.17 ± 2.32 years old(n = 6; male: 4, female: 2) | 200 mL of kefir daily, through oral administration | 2 weeks | NucliSENS easyMAG instrument (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) | Fecal samples | Kim et al. [32] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| ↑ Prevotellaceae, Selenomonadaceae, Sutterellaceae, Catenibacterium mitsuokai, and LAB.↓ Clostridiaceae, Fusobacteriaceae, Ruminococcaceae, Bacteroides uniformis, Fusobacterium mortiferum, Pseudoflavonifractor capillosus, and Fusicatenibacter saccharivorans | ||||||

| Kefir was prepared using the culture of DC1500I (Danisco, Olsztyn, Poland) | Adults with metabolic syndrome, aged 18–65 years(n = 12) | 180 mL/day of kefir, consumed orally | 12 weeks | Qiagen Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) | Fecal samples | Bellikci-Koyu et al. [24] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| ↑ Firmicutes, Verrucomicrobia, Actinobacteria, Bacteroides, Clostridia, Lactobacillales, Bifidobacterium, and the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio↓ Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Prevotellaceae, Alistipes, and Veillonellaceae | ||||||

| Cow milk fermented with kefir grains vs. kefir starter culture | Male BALB/c mice(n = 30) | 0.3 mL/day of kefir, through oral gavage | 15 days | Selective culture media for Lactobacilli, LAB, lactic streptococci, yeasts/fungi, Bifidobacterium spp., and Enterobacteria | Fecal samples | Erdogan et al. [34] |

| Microbial changes result | ||||||

| Kefir grains group:↑ Lactobacillus spp., Streptococci, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium spp., and yeastKefir starter culture group: ↓ Lactobacillus spp., Streptococci, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium spp. | ||||||

↑: increase; ↓: decrease; ICU: intensive care units; LAB: lactic acid bacteria; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; SCFA: short-chain fatty acid; UK4 and Fr1: two types of kefirs made from different kefir grain communities.

Findings from animal models align with human data, showing that grain-fermented kefir enhances short-chain-fatty-acid-producing bacteria, such as Lactobacillus reuteri, Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, and members of the Lachnospiraceae family, while decreasing pro-inflammatory taxa, including Clostridium and Propionibacterium [29, 30]. In addition, studies in companion animals demonstrated that kefir supplementation increased beneficial taxa and lowered Enterococcus abundance in cats and dogs [31, 32]. Bioactive peptides derived from kefir have also been shown to enhance microbial diversity and community structure in ovariectomized mice, suggesting that kefir’s metabolites contribute directly to microbiota modulation [33]. Notably, traditional grain-fermented kefir induces more diverse and stable microbiota shifts than commercial or starter-culture formulations, likely due to its richer microbial composition and higher metabolic activity [34].

Kefir was administered in markedly different dosages, which contributed to the variability in microbiota responses. Human interventions typically utilize 180–250 mL/day administered orally, leading to consistent increases in beneficial taxa such as Bifidobacterium, Lactococcus, and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-related genera [24–27]. Similarly, higher or escalating regimens such as 60→120→240 mL/day in ICU patients, administered orally or via nasogastric tube, were also associated with marked increases in LAB populations [28]. On the other hand, animal trials used considerably smaller weight-adjusted dosages, typically 0.1–0.3 mL/day administered orally and nonetheless promoted taxa such as Lactobacillus reuteri and Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, while reducing Clostridium spp. [29, 30, 33, 34]. Studies on companion animals using 30 mL/kg/day orally in cats and 200 mL/day orally in dogs showed similar increases in LAB and yeasts [31, 32]. Overall, these findings indicated that kefir’s effects were consistently achieved through oral intake, whether by drinking, nasogastric administration, or oral gavage, with dosage magnitude greatly influencing the direction and extent of microbial modulation.

Previous studies have demonstrated that kefir can modulate gut microbial composition across diverse host species and health conditions by increasing beneficial taxa, suppressing dysbiosis-associated bacteria, and contributing to the overall balance of the microbial community. However, the extent and specificity of these effects vary considerably and appear to depend on several factors, including the type of kefir used, the fermentation conditions, the administered dosage, and the host’s baseline microbiota profile.

Kefir influences gut microbiota through a variety of interrelated antimicrobial and ecological mechanisms driven by its diverse community of LAB, acetic acid bacteria, and yeast [35]. During fermentation, these microorganisms produce lactic acid, acetic acid, ethanol, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins, thereby suppressing pathogenic bacteria such as Enterobacteriaceae, Clostridium spp., and Escherichia coli by lowering luminal pH and disrupting cell membranes [14, 36]. This direct antimicrobial pressure selectively inhibits harmful taxa while promoting the growth of commensal species. Kefir also enhances colonization resistance by enabling beneficial microorganisms, particularly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, to compete with pathogens for adhesion sites and nutrients, thereby boosting mucin synthesis and inhibiting pathogen invasion [37]. Together, these processes reduce pathogen burden and help create an ecological niche that promotes balanced microbial populations.

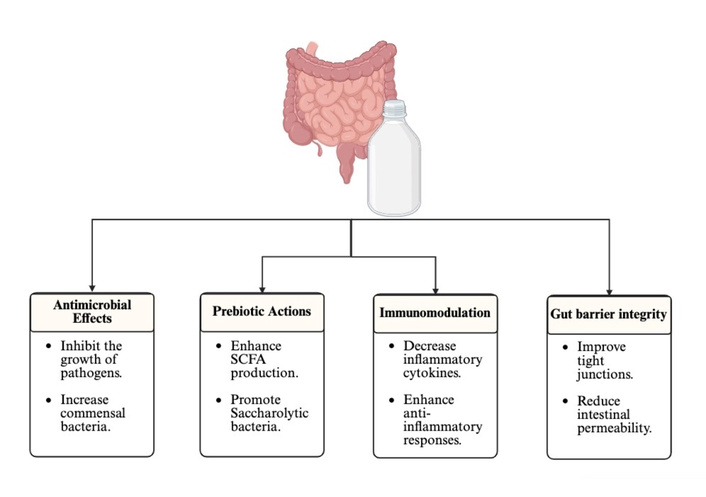

Beyond its antibacterial activity, kefir exerts strong prebiotic effects primarily through its exopolysaccharides, particularly kefiran, which act as fermentable substrates that promote the growth of saccharolytic bacteria [13]. Kefiran fermentation fosters cross-feeding interactions and increases the production of SCFA, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate [15]. These metabolites promote intestinal homeostasis by serving as energy sources for colonocytes, enhancing tight junction integrity, modulating glucose metabolism, and reducing inflammation (Figure 2) [38]. Butyrate, in particular, plays a central role in strengthening barrier function and regulating epithelial differentiation, which may explain why kefir consumption is consistently associated with increased SCFA-producing bacteria in both human and animal studies [37, 38].

Proposed mechanisms by which kefir modulates gut microbiota and host health, including antimicrobial effects, prebiotic actions, immunomodulation, and enhancement of gut barrier integrity. SCFA: short-chain fatty acid. Created in BioRender. Alali, MA (2025). https://BioRender.com/ty9i0ra

Kefir also modulates immune function through bioactive peptides, microbial cell-wall components, and polysaccharides that interact with host pattern-recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors [39]. These interactions suppress inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL-6) and increase anti-inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-10), creating an intestinal environment conducive to the expansion of beneficial taxa [17, 40]. In addition, kefir reduces oxidative stress in the GI mucosa through the generation of antioxidant peptides during fermentation, thereby limiting epithelial damage and supporting microbial stability [14]. The combination of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant actions helps counteract dysbiosis driven by metabolic and inflammatory disorders, providing a mechanistic explanation for the microbial shifts observed in intervention trials (Figure 2). A multi-strain probiotic consortium containing Limosilactobacillus fermentum BAB 7912 and Bacillus rugosus strains has demonstrated strong antioxidant activity (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP) and approximately 70–75% in vitro cholesterol reduction, highlighting how kefir-derived probiotics can influence oxidative stress and cholesterol metabolism [41]. Kefir-associated bacteria have functional probiotic characteristics such as acid and bile tolerance, strong auto-aggregation, high cell-surface hydrophobicity, bile-salt hydrolase activity, and antioxidant capacity that enhance their survival in the GI tract, adhere to the mucosa, and stabilize microbial communities [42].

Additional mechanisms contributing to kefir’s effects include improvements in gut-barrier integrity and overall host physiological control. Kefir-derived peptides increase tight-junction proteins, such as claudin-1 and occludin, thereby reducing intestinal permeability and limiting the translocation of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) that cause systemic inflammation [42]. Kefir fermentation also produces enzymes such as β-galactosidase that facilitate lactose digestion and support the proliferation of beneficial taxa [17]. Furthermore, previous research has suggested that kefir modulates the gut–brain axis by promoting bacteria such as Akkermansia, Lactobacillus, and other SCFA-producing taxa that influence neuroimmune pathways, stress responses, and neurotransmitter activity [36]. These integrated mechanisms account for the consistent enhancement of beneficial taxa and reduction of harmful or inflammation-associated microbes observed across multiple host models (Figure 2).

Kefir demonstrates substantial potential as a functional dietary intervention due to its complex and microbiologically rich composition. Evidence from human and animal studies consistently shows that kefir can beneficially modulate the gut microbiota by increasing taxa such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, and other SCFA-producing bacteria, while reducing inflammation-associated and opportunistic microorganisms. These effects arise from multiple mechanisms, including antimicrobial metabolite production, the prebiotic properties of kefiran, enhanced SCFA synthesis, immunomodulation, and improved gut-barrier integrity. Beyond microbial modulation, kefir’s diverse bioactive metabolites may support mucosal immunity, improve metabolic markers such as glycemic control and lipid profiles, and mitigate systemic inflammation. Its compatibility with both dairy and non-dairy substrates further positions kefir as a versatile platform for developing tailored probiotic or synbiotic formulations targeted to specific clinical needs. Continued mechanistic and clinical research could strengthen its role as a cost-effective and accessible strategy for promoting long-term gut and systemic health.

Despite these promising outcomes, several important limitations remain. Variations in kefir production methods, intervention dosages and durations, and analytical approaches contribute to inconsistent findings and hinder meaningful cross-study comparisons. Knowledge is limited regarding how grain-fermented kefir compares with starter-culture preparations in defined clinical populations. To advance the field, future investigations should adopt standardized production protocols, conduct long-term and well-controlled clinical trials, and employ comprehensive multi-omics approaches to elucidate underlying mechanisms and optimize efficacy across diverse populations. Overall, current evidence supports kefir as a promising dietary intervention for restoring gut microbial balance and improving GI and systemic health.

GI: gastrointestinal

ICU: intensive care unit

LAB: lactic acid bacteria

SCFA: short-chain fatty acid

MAA: Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Software, Writing—original draft. ABS: Conceptualization, Visualization, Project administration, Supervision, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 5354

Download: 109

Times Cited: 0