Affiliation:

1Centro de Diagnóstico de Osteoporosis y Enfermedades Reumáticas (CEDOR), Lima 15036, Perú

Email: maritzavw@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8494-5260

Affiliation:

2Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University of California at Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA 95817, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7578-8603

Explor Endocr Metab Dis. 2026;3:101456 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eemd.2026.101456

Received: September 02, 2025 Accepted: November 24, 2025 Published: January 09, 2026

Academic Editor: Silvano Bertelloni, University of Pisa, Italy

Osteoporosis is a disabling disease with a significant impact on the global population, particularly among older men and postmenopausal women. Several factors contribute to the increasing prevalence of osteoporosis, including greater life expectancy and the absence of symptoms in its early stages. The morbidity, mortality, and substantial economic burden associated with osteoporosis, especially due to hip fractures and related complications, constitute a major public health concern. Diagnosis should involve a comprehensive biochemical profile, along with additional tests to rule out secondary causes, which are often underdiagnosed and can influence the progression of the disease. Preventive measures and early diagnosis are essential to maintaining bone health and preventing fractures and disability. This review will focus on the definition, diagnostic approach, and key considerations prior to initiating treatment in patients with osteoporosis. Fracture risk prediction tools, including Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), and treatment strategies are not addressed, as this review focuses on the appropriate diagnostic evaluation of osteoporosis and the systematic exclusion of secondary causes.

Osteoporosis (OP) is a highly prevalent disease worldwide, characterized by increased bone fragility and alterations in bone microarchitecture, leading to low-impact fractures that significantly affect the physical, emotional, and social well-being of patients. The silent and progressive nature of OP highlights the importance of prevention and early diagnosis, for which a comprehensive evaluation is essential in the clinical assessment of OP, considering not only bone densitometry scores, but also factors related to bone loss [1, 2]. Several metabolic disorders can lead to reduced bone mass independent of OP and should be identified before initiating therapy. Failure to correct vitamin D deficiency and the underdiagnosis of comorbidities, particularly endocrinopathies, are common clinical oversights [1]. Moreover, concomitant medications should be carefully reviewed to prevent adverse pharmacological interactions. Ultimately, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans is fundamental for appropriate diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment monitoring. Properly performed and interpreted DXA assessments not only guide clinical decision-making but also play a pivotal role in preventing fractures, reducing healthcare costs, and improving long-term patient outcomes [3, 4].

OP is a major global health issue due to its high prevalence and serious complications. Because the disease remains asymptomatic until fractures occur, diagnosis is often delayed, and the resulting fragility fractures severely affect mobility, independence, and quality of life. With global life expectancy increasing, both OP and fracture rates continue to rise, posing a growing public health burden [2, 5].

Approximately 200 million people worldwide are affected, and prevalence has risen markedly in recent decades [1]. The International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) estimates that one in three women and one in five men over the age of 50 will experience an osteoporotic fracture [6–9]. In the United States, Naso et al. [10] reported increasing OP prevalence, particularly among females and non-Hispanic white individuals; notably, 69.12% of cases were undiagnosed, especially in men (86.88%) and individuals aged 50–59 years (84.77%). Global prevalence ranges from 18.3% (95% CI: 16.2–20.7) to 19.7% (95% CI: 18.0–21.4) [11, 12]. About 30% of postmenopausal U.S. women are affected, and 40% of them sustain fragility fractures, with a global prevalence estimated at 23.1% [11]. Rates are higher in developing than in developed countries (22.1% vs. 14.5%), likely due to nutritional deficiencies, limited healthcare access, and delayed diagnosis [12]. Reported prevalence varies widely, as described by Salari et al. [11], who found considerable geographic variation in OP rates among women. These differences likely reflect disparities in diagnostic criteria, population demographics, and environmental as well as socioeconomic factors influencing bone health [11].

Hip fractures are the most serious consequence, with 20–40% mortality within a year and a 10% risk of contralateral fracture in survivors [1, 13]. Furthermore, a 10% reduction in bone mass at the hip is associated with a 2.5-fold increase in the risk of hip fractures [14]. Notably, 23% of recurrent hip fractures occur during the first year [15]. Vertebral fractures are most frequent yet underdiagnosed, with about 70% going unrecognized, particularly in older individuals with degenerative conditions and chronic pain [16–19]. The estimated proportion of undiagnosed vertebral fractures reaches 46% in Latin America, 45% in North America and 29% in Europe, South Africa and Australia [20]. Patients with a history of vertebral fracture have a 2.3-fold increased risk of subsequent hip fracture and a 1.4-fold increased risk of distal forearm fracture [21]. Wrist fractures, often the earliest indicator of low bone mass, mainly affect women over 65 years [22, 23]. Only 15% of wrist fractures occur in men, with little increase in incidence observed with advancing age [23]. In Europe, the annual incidence of distal forearm fractures has been estimated at 1.7 and 7.3 per 1,000 person-years for males and females, respectively [24]. By 2030–2034, OP is projected to affect 263.2 million people (154.4 million women and 108.8 million men), underscoring the importance of early detection and prevention, particularly among women [25].

OP is a disease characterized by reduced bone mass and structural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to increased susceptibility to fractures [26]. This definition emphasizes the alteration of bone integrity, which is determined by two key factors: bone quantity and bone quality.

Bone quantity generally refers to the total volume of mineralized bone tissue and is often equated with bone mass, both of which are important predictors of fracture risk. Bone mass denotes the overall weight of bone tissue, encompassing both mineral components and the organic matrix. It is typically measured using DXA, which provides a two-dimensional assessment but does not capture detailed information about bone microarchitecture. In contrast, bone quantity is evaluated using imaging techniques such as quantitative computed tomography (QCT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or histomorphometry. These methods measure parameters including bone volume, thickness, and geometric structure, offering valuable insight into the three-dimensional quality and microstructural properties of bone [27–30].

Bone mineral density (BMD) and bone mineral content (BMC) are important indicators used to evaluate bone integrity. BMD refers to the concentration of mineral matter, primarily calcium and phosphate, within a specified area or volume of bone, whereas BMC describes the total amount of mineral present in a particular bone segment, reflecting both mineral density and bone size. BMD is commonly measured in two ways: areal BMD (aBMD), which is a two-dimensional value obtained through DXA and calculated by dividing BMC by the projected bone area, expressed in grams per square centimeter (g/cm2); and volumetric BMD (vBMD), which refers to the amount of mineral content per unit volume of bone tissue, representing the actual three-dimensional mineral density of bone tissue, measured in milligrams per cubic centimeter (mg/cm3), typically assessed by QCT, allowing distinction between trabecular and cortical bone compartments. The volumetric measure provides a more precise assessment of bone density by accounting for bone volume [31–34] (Table 1).

Definitions related to bone mass.

| Parameter | Definition | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Bone mineral density (BMD) | Reflects the total amount of minerals within a specific volume or area of bone tissue, serving as a key indicator of bone strength and structural integrity. Commonly measured by DXA. | g/cm2 |

| Bone mineral content (BMC) | Represents the total amount of mineral contained within a specific segment of bone, thus reflecting the absolute quantity of mineralized bone, serving as an indicator of bone strength and mass. | g |

| Areal BMD (aBMD) | A measure of the concentration of mineral content within a defined two-dimensional area of bone, widely used clinically to assess bone strength and fracture risk. Calculated by dividing the BMC by the two-dimensional projected bone area. | g/cm2 |

| Volumetric BMD (vBMD) | Represents the three-dimensional mineral density of bone tissue, enabling differentiation between trabecular and cortical bone compartments. | mg/cm3 |

DXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

BMD and BMC are among the most widely used metrics to assess bone mass. BMD is considered the gold standard for evaluating bone status in adults due to its strong correlation with fracture risk, whereas BMC is particularly valuable for monitoring bone growth in children or when assessing bone mass independent of bone size [35–37]. The term bone quality refers to characteristics of bone that contribute to its strength and resistance to fractures, beyond what is captured by BMD alone. These characteristics include bone microarchitecture, degree of mineralization, bone matrix composition (including collagen quality and mineral crystal size), accumulation of microdamage, and bone turnover rates [38–40] (Figure 1).

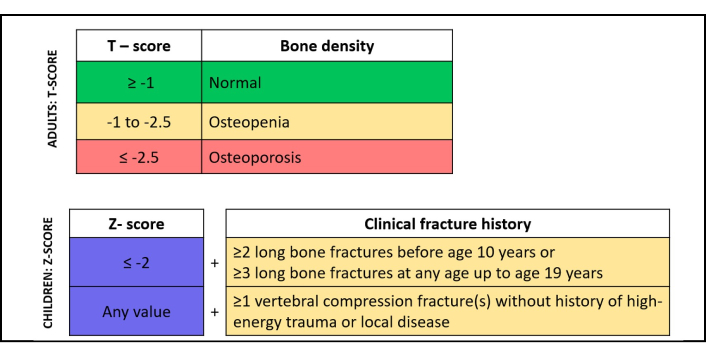

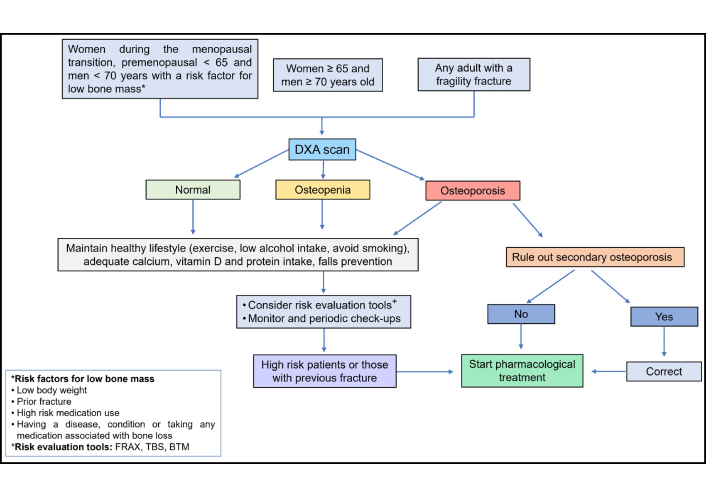

OP results from a decline in bone strength, which arises due to a reduction in bone mass and alterations in bone quality, ultimately increasing susceptibility to fractures [1]. Bone densitometry, a widely recognized and standardized diagnostic method endorsed by the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD), is recommended for women aged ≥ 65 years and men aged ≥ 70 years, as well as for younger individuals with risk factors that may compromise bone mass, such as early menopause, low body weight, conditions associated with bone loss, or a history of fractures suggestive of underlying OP. Bone density is assessed by comparing the individual’s BMD (g/cm2) to that of a reference population of the same sex, using two statistical scores: the T-score and the Z-score. The T-score compares an individual’s bone density to that of a healthy young adult and is primarily used for evaluating postmenopausal women and men aged ≥ 50 years. In contrast, the Z-score compares bone density to age-matched peers and is typically applied to premenopausal women, younger men (< 50 years), and children [43–45]. The T-score reference database is derived from measurements in young healthy white women of European ancestry, which may limit its generalizability across different ethnic groups and geographic populations [1, 2, 9, 26, 30, 31, 45].

In the adult population, OP is defined by a T-score of –2.5 or lower at the femoral neck or spine. T-scores between –2.5 and –1.0 indicate osteopenia, while values above –1.0 are considered normal. In younger individuals and premenopausal women, a Z-score of ≤ –2.0 is classified as “low bone mass” but should not be interpreted as “osteoporosis”. In children, the preferred terminology is “bone mineral density below the expected range for age”, which applies when a Z-score of ≤ –2.0 is found at key measurement sites such as the posterior-anterior (PA) spine and total body less head (TBLH), according to ISCD pediatric guidelines. The diagnosis of OP in children may be considered only when low bone mass is accompanied by a clinically significant fracture history [46] (Figure 2).

Definition of osteoporosis in adults and children (ISCD). ISCD: International Society for Clinical Densitometry.

OP can be classified according to its etiology and age of presentation as idiopathic, primary and secondary [44, 47, 48] (Table 2).

Classification of osteoporosis in children and adults.

| Population | Classification | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Children | Primary | Low bone mass caused by intrinsic skeletal defects and abnormal composition of bone tissue:

|

| Idiopathic juvenile | Transitory state of low bone mass of unknown etiology, characterized by pain in the back, hips and/or lower limbs; vertebral and long bone fractures. The onset of symptoms is insidious and starts before puberty. Patients show spontaneous improvement after puberty. | |

| Adults | Idiopathic | Osteoporosis of unknown etiopathogenesis occurring in young men and premenopausal women, might be associated with:

|

| Primary |

| |

| Children and adults | Secondary osteoporosis | Consequence of a disease or medications that impair bone metabolism or interfere with the absorption of calcium and/or vitamin D:

|

OP is uncommon in children, and low bone mass in this population is typically associated with genetic disorders that impair the collagen type I synthesis, as osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), hereditary or nutritional forms of rickets, and syndromes that disrupt bone mineralization, osteoblast or osteocyte function, and bone microarchitecture, such as hypophosphatasia (HPP), fibrous dysplasia, McCune-Albright syndrome, and various skeletal dysplasias [49–51]. These conditions, referred to as primary OP in children, differ significantly from the adult form. Clinical features are often identifiable early, either prenatally via ultrasound imaging or at birth based on physical characteristics. The consequences of these disorders commonly include reduced linear growth, recurrent fractures, bone deformities, delayed motor development, and long-term disability [50].

Idiopathic juvenile OP (IJO) is a rare, transient condition that typically affects children before the onset of puberty. It often presents with back pain resulting from vertebral compression fractures and limb fractures that may lead to altered gait. Radiological findings commonly reveal metaphyseal and vertebral fractures [52]. Interestingly, the clinical course of IJO tends to improve spontaneously over a period of 3 to 5 years, and many individuals go on to attain normal bone mass in adulthood. However, spinal deformities may persist [50, 53–55]. In adults, the term idiopathic OP is typically applied to young men and premenopausal women who develop low bone mass, with or without fragility fractures, in the absence of identifiable secondary causes. In many cases, affected individuals may have failed to achieve optimal peak bone mass, or they may present with modifiable risk factors such as poor nutrition, hormonal imbalances, or lifestyle factors contributing to bone loss that explain this condition [56, 57].

Transient idiopathic OP, such as that observed during pregnancy and lactation, may be classified within this group of temporary bone loss disorders. These periods are characterized by a heightened physiological demand for calcium to support fetal skeletal development and maternal milk production [58, 59]. To accommodate these needs, the maternal body undergoes physiological adaptations including increased intestinal calcium absorption and elevated bone turnover rates [58]. However, when calcium intake is insufficient, maternal bone resorption is upregulated to fulfill fetal calcium requirements, potentially leading to significant skeletal demineralization in the mother [58, 60]. Transient OP of the hip is another localized condition typically occurring during the third trimester of pregnancy or early postpartum. It is characterized by localized edema in one or both femoral heads without evidence of systemic bone resorption [60, 61]. The primary clinical manifestation is hip pain, often accompanied by decreased BMD in the affected region [60].

During lactation, increased trabecular bone resorption and transient maternal bone demineralization serve as the primary sources of calcium for daily breast milk production. Although renal calcium conservation mechanisms are activated during this period, the majority of skeletal deterioration affects the trabecular bone microarchitecture [58–60]. Women may be affected during pregnancy, the postpartum period, or lactation, commonly presenting with severe back or groin pain and radiological signs of osteopenia or OP, which increase their risk of fractures [62]. Importantly, bone loss associated with pregnancy and lactation is typically reversible, with recovery occurring after weaning. These phases represent critical windows during which ensuring adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, or implementing supplementation, when necessary, is essential [63–65].

Primary OP in adults is the most prevalent form and is generally classified into two types. Type I, or postmenopausal OP, occurs in women and is characterized by rapid bone loss due to hormonal changes, particularly reduced levels of estrogen and progesterone during menopause [44]. Type II, or senile OP, is seen in elderly individuals and is attributed to age-related skeletal degeneration. It involves loss of both trabecular and cortical bone and is commonly associated with hip and pelvic fractures [44]. It should be taken into account that calcium absorption tends to decline significantly in older adults, particularly beyond the age of 70, so ensuring an adequate intake might help to prevent additional bone mass [66].

Secondary OP results from underlying medical conditions or external factors that disrupt normal bone turnover. These include chronic inflammatory diseases, malignancies, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and prolonged immobilization. Conditions such as malabsorption syndromes and a history of bariatric surgery often contribute to vitamin D deficiency. Furthermore, several medications are known to impair bone metabolism and vitamin D pathways, including glucocorticoids (GC), anticonvulsants, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), thiazolidinediones, and aromatase inhibitors, among others as depicted in Table 2 [67–69].

Before initiating treatment for OP, several critical considerations must be addressed to optimize patient outcomes. First, it is essential to identify and manage any secondary causes of OP, as these may require specific interventions beyond standard bone-targeted therapies [70]. Correcting vitamin D deficiency is a foundational step, given its vital role in calcium homeostasis and bone metabolism. Ensuring adequate dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D, either through nutrition or supplementation, is equally important to support bone health and enhance therapeutic efficacy [71, 72]. Treatment selection should be individualized, taking into account the patient’s overall clinical profile, including comorbid conditions, concomitant medications, and potential contraindications, to maximize benefits and minimize risks. Additionally, awareness of technical factors and potential sources of error in BMD measurement by DXA is crucial for accurate diagnosis and monitoring; these issues will be explored further in the subsequent section (Table 3).

Considerations when diagnosing osteoporosis.

| Consideration | Implications for diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Rule out secondary causes for osteoporosis |

|

| Assure adequate nutrient intake and supplementation if needed |

|

| Consider comorbidities |

|

| Avoid mistakes related to DXA measurements |

|

BMD: bone mineral density; DXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Before starting treatment, it is important to ensure that secondary causes that could be associated with the patient’s low bone mass have been ruled out. A very common mistake is to consider that all older women have postmenopausal OP, and not to evaluate other causes that may coexist or even be the main cause of bone mass loss. Among the most frequent conditions that should be evaluated are vitamin D deficiency, hypercalciuria, endocrinopathies and concomitant medication associated with low bone mass that has not been evaluated. The first step to follow is to request additional tests to detect the presence of secondary causes of OP [68, 73]. Complete laboratory tests and a metabolic profile including 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD; or calcidiol), serum calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, intact parathormone (PTH), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and bone turnover markers such as collagen type I C-telopeptide (CTX) and procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) should be considered. Other tests should be requested to rule out subjacent diseases as celiac disease (CD), hypogonadism, primary hyperparathyroidism, CKD and malignancies according to the clinician’s criteria. The basic laboratory profile recommended is shown in Table 4.

Basic laboratory profile in patients with osteoporosis.

| Rationale for testing | Test |

|---|---|

| Basic profile |

|

| Bone turnover markers |

|

| Endocrinopathies |

|

| Other specific tests |

|

25OHD: 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

There are rare metabolic bone diseases that, underdiagnosed, might result in a treatment failure. Genetic conditions associated with OP such as HPP and X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) represent a challenge, because both require disease-specific treatment, beside bone agents, in order to manage the disease. Finding repetitive measures of low ALP levels adjusted for the patient’s age and sex should guide the clinician to consider HPP and confirm the diagnosis with genetic testing of the ALPL gene [74, 75]. In a patient with low serum phosphate along with elevated levels of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), XLH should be suspected, and a genetic study of the PHEX gene might be recommendable [76]. Individuals with milder or non-deforming forms of OI may go through life without noticeable physical abnormalities. OI types I, IV, and V often present with normal stature, minimal or no history of fractures, and no visible skeletal deformities, which can lead to delayed recognition or misdiagnosis. Many patients with these unusual conditions can be noticed during adulthood, without having been clearly diagnosed or appearing obviously ill in childhood, especially those with subtle forms of the disease and non-specific symptoms, such as joint pain, dental abscesses, fatigue and joint stiffness [77].

Certain conditions may present with distinctive physical findings that facilitate clinical recognition. For example, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome may be suspected in patients exhibiting joint hypermobility, blue sclerae, and fragile or hyperextensible skin. Adult patients have an increased risk of vertebral fractures independently of their BMD status [78–80]. Systemic signs such as weight loss, palpitations, tremor, and heat intolerance should raise suspicion for hyperthyroidism. Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) may exhibit normal BMD, yet face an elevated fracture risk due to compromised bone quality [81]. Similarly, in individuals with acromegaly, features such as coarse facial characteristics, enlarged hands and feet, and joint pain should prompt further investigation. Notably, although BMD may appear elevated in this group, bone quality is often impaired, predisposing them to fractures [82, 83]. Young adults and premenopausal women should be tested for hormonal alterations such as hypogonadism, hyperprolactinemia, hypercortisolemia and other subjacent endocrinopathies that might be underdiagnosed [84, 85].

Testing for infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis B and C should be considered in patients with associated risk factors, such as exposure to infected blood, unprotected sexual contact, sharing of needles, and unsafe medical or cosmetic procedures [86]. Patients who underwent bariatric surgery, or those with malabsorption usually develop hypovitaminosis and protein loss; and in these cases, is determinant to measure levels of vitamin D to prevent future bone mass loss. In older patients, CKD, inflammatory chronic conditions and malignancies can be easily ruled out by ordering complementary tests, and imaging in suspicious cases. Serum protein/immune-electrophoresis and free light chains in older men and women can be performed [68]. Bone turnover markers are specialized biochemical tests used to evaluate the rate of bone formation and resorption. They provide valuable information for assessing metabolic bone disorders and are particularly useful in conditions such as renal osteodystrophy and Paget’s disease [42, 55, 87]. In addition, they assist in the evaluation and monitoring of OP, hyperparathyroidism, thyrotoxicosis, glucocorticoid-induced bone loss, and other secondary causes of skeletal fragility [55, 68, 87]. Their use helps determine the activity of bone remodeling, assess treatment efficacy, and support clinical decision-making in a variety of metabolic and endocrine conditions [55, 68, 87]. Diagnosing a secondary cause of OP provides the opportunity to start an adequate treatment for controlling the disease and have a better outcome when OP treatment is started (Figure 3).

Vitamin D, a steroid hormone essential for calcium and phosphorus homeostasis, regulates bone mineralization and overall skeletal metabolism. Its deficiency, common and often underdiagnosed worldwide, causes rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults [88, 89]. Correction of deficiency is essential before initiating OP therapy; therefore, serum 25OHD measurement is recommended for all patients, as it represents the most reliable indicator of vitamin D status due to its abundance as a circulating metabolite, and longer half-life compared with calcitriol [1,25-(OH)2D3] [71, 88, 90, 91]. Optimal bone health requires maintaining serum 25OHD levels ≥ 30 ng/mL (75 nmol/L), while levels of 10–16 ng/mL (25–40 nmol/L) are associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism and OP, and < 8–10 ng/mL (20–25 nmol/L) with osteomalacia [71, 88, 89, 92, 93]. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ definitions of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency are summarized in Table 5 [88, 89, 94].

| Status | 25OHD (ng/mL) | 25OHD (nmol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity/Upper limit | ≥ 100 | ≥ 250 |

| Sufficiency | ≥ 30 | ≥ 75 |

| Insufficiency | 21–29 | 52.5–72.5 |

| Deficiency | ≤ 20 | ≤ 50 |

Most recommendations for correcting vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency are provided by international societies. In a general manner, patients at risk of vitamin D deficiency are recommended to receive doses of 800 IU to 1,000 IU daily along with calcium [88]. For rapid repletion, a loading dose of 25,000–50,000 IU/week for 4–6 weeks is suggested, adjusted to baseline 25OHD levels (< 20 ng/mL for 8 weeks; 20–30 ng/mL for 4 weeks), and indicated in severe deficiency (< 10 ng/mL), severe obesity, malabsorption, post-bariatric surgery, or when treatment with potent antiresorptive agents such as denosumab or intravenous bisphosphonates needs to be initiated [88, 95–97]. After this initial regimen, a maintenance dose varying from 800–2,000 IU daily or 50,000 IU per month can be prescribed in order to maintain the target blood level [88, 95, 96, 98–103]. High-dose vitamin D supplementation should be avoided, as excessive intake may elevate FGF-23, leading to inhibition of 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) activity, reduced circulating vitamin D metabolites, and activation of 24-hydroxylase pathways that catabolize calcitriol and calcidiol into less active compounds such as calcitroic acid. This process ultimately limits vitamin D receptor (VDR) activation and prevents excessive downstream signaling [88, 104–108]. The choice of initial and maintenance dosing should be individualized at the clinician’s discretion, tailoring therapy to each patient’s clinical profile and biochemical response.

Vitamin D is fat-soluble molecule with pleiotropic effects in bone, participating in calcium and phosphorus metabolism by acting on three main organs: intestine, bone and kidney. The main source of vitamin D in humans is the cutaneous synthesis after sun exposure, although it can also be obtained from vitamin D-rich foods, but in minor amounts. The two forms of vitamin D are cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) of animal origin, and ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) of vegetable origin; both share a common metabolic pathway that leads to the synthesis of calcitriol in the kidney, which constitutes the active form of vitamin D [1, 109]. The main causes of vitamin D deficiency are the lack of sun exposure, as in institutionalized patients or the use of sunscreen, especially for skin cancer prevention, or in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who must avoid solar exposure. The age-associated decline in cutaneous vitamin D synthesis, with older skin producing approximately 40% less vitamin D, contributes to diminished intestinal calcium absorption and subsequent reductions in bone mass and mineralization [1, 110, 111]. As calcium bioavailability varies by source, being highest in dairy products [112–114], adequate intake, together with vitamin D, is essential for skeletal integrity, with combined supplementation shown to reduce fracture risk [115]. Adequate intake is fundamental for OP prevention and should be carefully considered at the start of treatment to ensure optimal levels are maintained for the patient’s age. Recommended daily intakes of calcium and vitamin D by age are presented in Table 6.

| Age | Calcium (mg/day) | Vitamin D (IU/day) |

|---|---|---|

| 19–50 years | 1,000 | 600 |

| 51–70 years | 1,000*–1,200 | 600 |

| > 70 years | 1,200 | 800 |

*: Intake recommended for males.

Vitamin D and calcium supplementation remain cornerstone strategies for fracture prevention. In a two-year cluster randomized controlled trial of 7,195 institutionalized older adults (mean age 86 years) with adequate vitamin D levels but low calcium intake, Iuliano et al. [116] reported that achieving a calcium intake of 1,300 mg/day and < 1 g/kg protein/day through increased dairy consumption reduced the risk of all fractures by 33%, hip fractures by 46%, and falls by 11% (p = 0.04), with benefits evident as early as three to five months.

A review of 26 randomized clinical trials by Voulgaridou et al. [117] showed that combined calcium and vitamin D supplementation, but not vitamin D alone, significantly increased BMD. Similarly, Yao et al. [118] found that each 10 ng/mL (25 nmol/L) increase in serum 25OHD was associated with a 7% reduction in overall fracture risk and a 20% reduction in hip fracture risk. Vitamin D alone did not significantly reduce fracture incidence (RR = 1.06; 95% CI: 0.98–1.14), whereas combined supplementation reduced the risk of any fracture by 6% and hip fractures by 16% [118]. Consistent results were reported by Manoj et al. [119] in a meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials including 12,620 participants. Daily supplementation with vitamin D3 (800 IU) plus calcium significantly reduced hip fracture risk by 25% (p = 0.0003) and non-vertebral fracture risk by 20% (OR = 0.80; 95% CI: 0.72–0.89; p < 0.0001). The most effective regimen was 800 IU of vitamin D3 with 1,200 mg of calcium, which reduced hip fracture risk by 31% (OR = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.58–0.82; p < 0.0001) [119].

Vegetarian and particularly vegan diets are associated with lower BMD compared with omnivorous diets, likely due to reduced intake of calcium, vitamin D, protein, and lower body weight [120–122]. Lacto-ovo-vegetarians consume dairy and eggs, which provide higher calcium, vitamin D, and animal protein, favoring bone health. However, both vegetarian and vegan diets often fail to meet all nutrient requirements, making them more susceptible to low BMD and fractures [120, 123, 124]. In a Bayesian meta-analysis including 2,749 participants, vegetarians had about 4% lower BMD at the femoral neck and lumbar spine than omnivores, with a greater reduction in vegans [ratio of means (RoM) = 0.94; 95% CI: 0.91–0.98] than in lacto-ovo vegetarians (RoM = 0.98; 95% CI: 0.96–0.99) [122]. Vitamin B12 is crucial for bone metabolism through its role in taurine and IGF-1 synthesis, supporting bone mass and structure [124, 125]. Deficiency is observed in 11% of omnivores, 77% of lacto-ovo vegetarians, and up to 92% of vegans, leading to increased methylmalonic acid and homocysteine levels [126]. Low vitamin B12 is linked to reduced BMD, BMC, and impaired bone cell function [124]. In elderly Dutch women, vitamin B12 deficiency was associated with higher OP prevalence (37%) compared to those with normal levels (6%), with B12 contributing 1.3–3.1% to BMC and BMD variance [127]. Therefore, individuals following vegan or vegetarian diets should be advised to ensure adequate intake or supplementation of calcium, vitamins D and B12, and protein, with regular monitoring of bone health.

IBD is associated with low BMD and an increased risk of fractures, even among younger individuals [128]. Bone loss in IBD arises from nutrient malabsorption, malnutrition, chronic inflammation with elevated proinflammatory cytokines, and glucocorticoid therapy. Activation of osteoclastogenesis through receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK)/RANK ligand (RANKL) signaling further promotes bone resorption, while low BMI and sarcopenia contribute additional risk for OP, falls, and fractures. A meta-analysis of 261,829 IBD patients showed a higher fracture risk than controls (OR = 1.42; 95% CI 1.21–1.66; p < 0.001) [129], consistent with another meta-analysis of 24 studies reporting increased overall (RR = 1.38; 95% CI 1.11–1.73; p = 0.005) and vertebral fracture risk (OR = 2.26; 95% CI 1.04–4.90; p < 0.001) and lower BMD and Z-scores at all sites in IBD patients [130]. Bone deficits appear early, as demonstrated in children with IBD who showed lower lumbar spine and whole-body aBMD and BMC than controls (p < 0.001) and a higher vertebral fracture rate (11% vs. 3%; p = 0.02) [131]. These findings emphasize the need for early assessment and prevention of OP in IBD.

CD is an autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten exposure and has been increasingly recognized in recent decades. Regardless of age at onset, CD is associated with reduced BMD, impaired bone microarchitecture, and a higher fracture risk [132–135]. A meta-analysis reported a 69% higher risk of hip fracture and a 30% higher risk of any fracture in CD, with fractures being 1.92 times more frequent than in controls [135]. Similarly, a large Danish cohort study found greater risks of OP [hazard ratio (HR) = 5.39; 95% CI: 4.89–5.95] and fractures (major osteoporotic: HR = 1.37; 95% CI: 1.25–1.51; any fracture: HR = 1.27; 95% CI: 1.18–1.36) [133]. In children, CD leads to lower BMD, impaired bone health, and shorter stature [134]; a registry-based study showed higher fracture incidence (HR = 1.57 for any fracture; HR = 1.67 for multiple fractures) [132], and meta-analyses confirmed reduced BMC and aBMD compared with controls [134]. Adherence to a gluten-free diet improves bone parameters, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis of 28 studies showing significant BMD and BMC gains, though levels often remain below those of healthy peers [136, 137]. Early diagnosis and strict compliance with a gluten-free diet are therefore crucial to preserve bone health and minimize fracture risk.

CAG involves progressive loss of parietal cells, most often due to autoimmune mechanisms or HP infection, leading to hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria and impaired absorption of iron, calcium, and vitamin B12 owing to loss of intrinsic factor [138, 139]. Vitamin B12 deficiency adversely affects bone health and may increase fall risk through peripheral neuropathy [128]. HP infection is responsible for approximately 85% of gastric and 95% of duodenal ulcers and is a recognized risk factor for gastric cancer [128, 140, 141]. Current management includes antibiotic therapy combined with a PPI or histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA). Long-term use of these acid-suppressive agents has been linked to OP and fracture risk. In a Korean population-based case-control study, use of anti-peptic agents increased the risk of osteoporotic fractures [PPI (HR = 1.31), H2RA (HR = 1.44), muco-protective agents (HR = 1.33); all p < 0.001], with the highest risk seen with combined PPI and H2RA use (HR = 1.58; p = 0.010) or triple therapy (HR = 1.71; p = 0.001) [142]. Regular fracture risk assessment and bone mass monitoring are therefore advisable in these patients to prevent OP-related complications.

Chronic liver disease is associated with low bone mass and an increased risk of fractures, with prevalence estimates ranging from 6% to 40% [143–145]. Bone loss results from cytokine-mediated activation of the RANK/RANKL pathway, impaired osteoblast activity, and deficiencies in IGF-1, vitamin K, and vitamin D due to cholestasis and altered hepatic hydroxylation [143–145]. Reduced vitamin D synthesis due to altered liver function and further aggravated by jaundice contributes to reduced calcium absorption and impaired mineralization [144].

Meta-analyses show significant associations between alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and fracture risk (RR = 1.94; 95% CI: 1.35–2.79) [146] and between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and OP (OR = 1.46 in men and 1.48 in women), with higher odds of fractures compared with controls [147]. Cirrhosis was also linked to increased OP prevalence (34.7% vs. 12.8%; OR = 2.52; 95% CI: 1.11–5.69) [148], and a larger analysis confirmed higher odds of OP (OR = 1.93; 95% CI: 1.84–2.03) and fractures (OR = 2.30; 95% CI: 1.66–3.18), with reduced BMD at key skeletal sites [149]. Liver transplantation, which has risen globally by 20% since 2015, also increases bone fragility, with OP and fractures observed in 11.68% and 20.40% of recipients, respectively [150–152]. Routine bone and metabolic assessment is essential in these high-risk patients to prevent skeletal complications.

CKD is a well-established contributor to impaired bone health, OP, and an increased risk of fractures [153–156]. CKD-mineral and bone disorder (MBD) is a systemic condition characterized by disturbances in calcium, phosphate, PTH, and vitamin D metabolism, leading to abnormalities in bone turnover, mineralization, structure, and growth, as well as vascular and soft-tissue calcification [153, 154, 156]. According to the National Kidney Foundation/Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQI), CKD is classified into five stages based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), with advanced CKD (stages G4–G5, eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2) affecting 0.5–1% of the population [153]. Renal impairment is particularly prevalent in older adults, with only 26% of those aged ≥ 70 years maintaining normal kidney function [156]. In assessing OP, kidney function must be considered alongside traditional risk factors. A dynamic bone disease, characterized by low bone turnover, is frequent among dialysis patients [153, 154]. Phosphate retention, impaired vitamin D synthesis, and secondary hyperparathyroidism further exacerbate bone loss, even at early stages of CKD [153, 154, 156]. Epidemiological data demonstrate a twofold increase in hip fracture risk among patients with moderate to severe CKD [156]. NHANES III reported that participants with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 had higher odds of hip fracture (OR = 2.12; 95% CI: 1.18–3.80), and CKD prevalence was nearly three times greater among those with prior fractures aged 50–74 years (19.0% vs. 6.2%; p = 0.04) [157].

Patients on hemodialysis (HD) show markedly increased fracture risk, with Alem et al. [158] reporting a fourfold increase compared to the general population and up to a 10–100-fold increase among those < 65 years [156]. Meta-analyses confirm a graded relationship between declining eGFR and fracture risk, especially for hip fractures [155, 159]. Falls affect approximately 25% of patients with advanced CKD annually [160, 161], with risk factors including frailty, hypotension, malnutrition, anemia, and antidepressant use. In HD cohorts, fractures, most frequently ribs, affect roughly 25% of patients, with age, low hemoglobin, and high phosphorus as independent predictors [162]. A comprehensive assessment of renal function and bone health is essential to reduce fracture risk in this vulnerable population.

Bone metastases are a frequent and serious complication of advanced malignancies, particularly those originating in the breast, prostate, lung, thyroid, and kidney. Disseminated tumor cells disrupt the normal balance between bone formation and resorption, leading to skeletal-related events (SREs) such as bone pain, pathological fractures, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord or nerve root compression [163–168]. The metastatic process is driven by complex interactions between cancer cells, the bone microenvironment, immune mediators, and signaling pathways that promote tumor growth at distant sites. Depending on the tumor type, lesions may be osteolytic, osteoblastic, or mixed [163, 164, 167, 168]. Prostate and breast cancers show the highest propensity for bone involvement, affecting up to 65–75% of patients with advanced disease [168].

Lung cancer has been identified as the most frequent primary source of de novo bone metastases. In an analysis by Ryan et al. [169], lung cancer exhibited the highest incidence (8.7 per 100,000 in 2015), followed by prostate and breast cancer (3.19 and 2.38 per 100,000, respectively). Among younger patients (< 20 years), endocrine malignancies and soft-tissue sarcomas predominated, with a notable increase in bone metastasis incidence from prostate and gastric cancers [169]. Similarly, a retrospective series of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer reported bone metastases in 39% of patients [170]. The lumbar and thoracic vertebrae are the most common metastatic sites, followed by the cervical spine and sacrum [171].

Disruption of the balance between bone resorption and formation leads to three main patterns of metastases: osteolytic, osteoblastic, and mixed [168]. In multiple myeloma, 80–90% of patients develop osteolytic lesions driven by malignant plasma cells that stimulate osteoclast activation and suppress osteoblast function through mediators such as RANKL, interleukin 6 (IL-6), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), and stromal-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) [172, 173]. Similarly, osteolytic metastases in breast cancer are associated with tumor secretion of parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP), IL-1, IL-6, GM-CSF, and TNF-α, which enhance osteoclastogenesis while inhibiting osteoblast activity [164, 166, 168]. Tumor-derived inhibitors such as dickkopf-1 (DKK1) and sclerostin (SOST) further suppress osteoblast differentiation by blocking Wnt/β-catenin signaling, exacerbating bone destruction [166, 167]. Conversely, osteoblastic or sclerotic metastases, characteristic of prostate cancer, result from increased osteoblast activity driven by endothelin-1, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), TGF-β, Wnt proteins, and IGFs [167, 174]. Elevated osteoprotegerin (OPG) levels inhibit osteoclast differentiation, favoring bone formation [166, 175]. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) may further contribute by cleaving PTHrP, thereby reducing osteoclastic activity [166–168]. In certain breast and prostate cancers, mixed lesions arise through interactions mediated by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and endothelin-1 via PDGFRα/β and ETAR, along with β-catenin-dependent signaling that determines lesion phenotype [168, 174–177].

Assessing bone involvement at diagnosis is therefore crucial to prevent skeletal complications [164]. Bone pain is the most prevalent SRE, affecting 60–84% of patients with advanced cancer [164, 165, 168, 178]. It results from periosteal irritation, structural damage, inflammatory processes, and remodeling of sensory and sympathetic nerve fibers that sensitize nociceptors [165, 168]. Hypercalcemia, a common paraneoplastic syndrome, occurring in 5–10% of patients with advanced breast, lung, renal, or hematologic malignancies [164, 168]. It arises from focal or generalized osteolysis, humoral factors (notably PTHrP in ~80% of cases), increased tubular calcium reabsorption, and decreased glomerular filtration [168, 178, 179]. Clinical manifestations range from gastrointestinal and neurocognitive symptoms to cardiac arrhythmias due to QT shortening [168, 178]. Pathological fractures represent a late and debilitating complication, reported in 9–30% of patients with skeletal involvement [164, 168, 178]. They typically affect weight-bearing bones, particularly the vertebral column, often leading to spinal instability and neurologic compromise. Other common sites include the proximal femur, pelvis, humerus, and ribs, resulting in pain, reduced mobility, and frequent need for surgery [164, 168, 178, 180]. Spinal cord compression, most common in breast, prostate, and lung cancer, arises from vertebral collapse or direct tumor invasion. It presents as progressive, nocturnal pain often preceding neurological deficits and associated with microfractures [168, 178, 181, 182]. In suspected cases, bone scintigraphy is recommended to evaluate disease extent and exclude or confirm spinal cord involvement [168, 181, 182].

In chronic arthritic and autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the inflammatory pannus releases cytokines that disrupt bone homeostasis by stimulating osteoclast differentiation and inhibiting osteoblast maturation, leading to accelerated bone resorption and bone loss. Persistent inflammation exposes patients to multiple risk factors for low BMD and OP, including elevated cytokines, reduced physical activity, long-term glucocorticoid therapy, vitamin D deficiency, and postmenopausal status [183, 184]. In RA, chronic inflammation driven by IL-1, IL-6, IL-17, IL-23, and TNF-α enhances osteoclastogenesis through RANKL and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), contributing to bone erosion and systemic bone loss [183, 185]. Dysregulation of DKK1, a Wnt signaling inhibitor, also plays a key role: its overexpression in RA and multiple myeloma promotes bone resorption, while its downregulation in ankylosing spondylitis and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) leads to aberrant bone formation. TNF-α-mediated DKK1 upregulation provides a mechanistic link between chronic inflammation and bone loss [183, 186–190]. Vitamin D further influences bone and immune regulation by binding to VDR on T and B lymphocytes and dendritic cells, modulating cytokine production and immune activation. Deficiency is common in autoimmune and rheumatic diseases and correlates with increased inflammatory activity and disease severity. In RA and SLE, low vitamin D levels are associated with greater disease activity and flare risk, highlighting its potential as an adjunctive immunomodulatory factor in chronic inflammatory conditions [109].

OP, falls, and fractures are well-documented complications in individuals with cognitive impairment and dementia [191–201]. These patients have a markedly higher risk of falls, morbidity, and mortality, while those with fragility fractures face increased institutionalization and refracture rates, highlighting the need for early detection [191, 198]. Risk factors include cognitive and motor dysfunction, postural instability, autonomic impairment, sarcopenia, polypharmacy, environmental hazards, depression, sensory deficits, vitamin D deficiency, and frailty, a clinical state of diminished physiological reserve [192, 202, 203]. In a prospective study of 179 older adults with dementia, fall incidence was nearly eightfold higher than in controls, with prior falls and Lewy body dementia predicting recurrence; modifiable factors included orthostatic hypotension and depressive symptoms [191]. OP is also more prevalent in cognitive decline. A meta-analysis of 9,872 patients showed a higher risk of OP (RR = 1.56; 95% CI: 1.30–1.87) and an even greater risk in Alzheimer’s disease (RR = 1.70; 95% CI: 1.23–2.37) [194]. Jeon et al. [195] found dementia independently increased hip fracture risk (10.66% vs. 5.53% in controls), and Matsumoto et al. [196] reported elevated fracture risks even in early-onset dementia, with hip (OR = 8.79), vertebral (OR = 1.73), and major osteoporotic fractures (OR = 2.05). Interestingly, the use of cholinesterase inhibitors was associated with a reduced risk of hip fractures (OR = 0.28) [196]. Patients with OP may face further hip fracture risk, underscoring early cognitive assessment and preventive care [197]. Similarly, individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD) show an increased risk of OP and fractures, particularly hip fractures [193, 199]. Bone loss in PD is multifactorial, related to immobility, low body weight, reduced muscle strength, vitamin D deficiency, malnutrition, and levodopa-induced hyperhomocysteinaemia [199, 204–206]. Reduced BMD at the spine and femoral neck has been consistently reported [205, 206], and a meta-analysis confirmed lower BMD across skeletal sites [206]. Large cohort studies also demonstrate nearly doubled fracture risk in PD (adjusted HR = 1.89; 95% CI: 1.67–2.14) [200, 201]. Early identification of modifiable risk factors and integrated interventions—cognitive screening, fall prevention, and bone health optimization are essential to improve outcomes in these vulnerable populations.

Polypharmacy, defined as the concurrent use of five or more medications, is strongly associated with an increased risk of fragility fractures in older adults [207–209]. Cumulative drug exposure may heighten fracture susceptibility, underscoring the importance of regular medication review in aging populations [210, 211]. Although several medications independently increase fall and fracture risk, it remains unclear whether these risks are directly compounded by the concurrent use of multiple agents [208]. Beyond skeletal effects, polypharmacy has been linked to adverse outcomes such as cognitive and physical decline, hospitalizations, functional dependence, and higher mortality [212]. In a large cohort of osteoporotic women in South Korea, Park et al. [209] reported a dose-dependent relationship between medication number and hip fracture risk, which remained significant after adjustment for confounding factors. Similarly, a prospective cohort study of 2,023 patients followed for 5.6 years found that polypharmacy (≥ 5 medications) and hyperpolypharmacy (≥ 10 medications) were more prevalent among individuals with CKD, particularly those on dialysis. Fracture risk rose with medication count (HR = 1.32 for polypharmacy; HR = 1.99 for hyperpolypharmacy), accounting for 9.9% of all fractures and 42.1% among dialysis patients [211]. Comparable trends were observed in type 2 diabetes. In the Fukuoka Diabetes Registry, fracture incidence increased from 21.2 to 44.0 per 1,000 person-years across medication categories, with adjusted HRs of 1.34, 1.76, and 1.71 for 3–5, 6–8, and ≥ 9 drugs, respectively; each additional drug raised fracture risk by 5% (p < 0.001) [210]. In a population-based study of 2,328 elderly patients, Lai et al. [213] found that hip fracture risk rose sharply with medication count, patients taking ≥ 10 drugs had an OR = 8.42 (95% CI: 4.73–15.0) compared to those using 0–1. Among those aged ≥ 85 years, the risk increased 23-fold (OR = 23.0; 95% CI: 3.77–140) [213]. Post-fracture outcomes are also influenced by medication burden. Among 272 patients after hip replacement, 31.6% were readmitted and 13.2% died within six months. The number of discharged medications correlated with rehospitalization risk (OR = 1.08; 95% CI: 1.01–1.17; p = 0.030), particularly with the use of antiosteoporotic agents, SSRIs, vitamin K antagonists, thiazides, and tramadol [214]. Overall, polypharmacy represents a significant, potentially modifiable risk factor for fractures and adverse outcomes in older adults and individuals with chronic diseases.

Socioeconomic constraints and the lack of adequate caregiving infrastructure exert a substantial negative impact on the management and prognosis of OP. Financial hardship frequently delays diagnosis and restricts access to essential diagnostic modalities, such as bone densitometry, as well as pharmacologic therapy and nutritional supplementation, ultimately increasing the risk of preventable fractures and impeding recovery [1–4, 9]. The absence of structured caregiving systems, including nursing homes, rehabilitation centers, and home-based support, further exacerbates clinical outcomes by elevating fall risk and hindering functional recovery following fractures. Individuals lacking adequate caregiver support often experience reduced mobility, poor adherence to prescribed treatments, and limited engagement in rehabilitation programs, all of which contribute to accelerated bone loss and functional decline. These challenges are reflected in population-based studies demonstrating that social and economic disparities are strongly associated with increased fracture incidence, prolonged hospitalization, and higher mortality among individuals with OP [5, 9–12]. Addressing these inequities through improved access to healthcare services, nutritional support, and post-fracture rehabilitation is essential to enhance outcomes and quality of life in this vulnerable population.

DXA remains the gold standard for diagnosing OP, assessing fracture risk, and monitoring treatment. However, procedural and interpretative errors are frequent and may compromise diagnostic reliability and follow-up accuracy [3, 215–218]. Such errors may result from inappropriate clinical indications, poor image acquisition, analytical inaccuracies, or misinterpretation of results, as summarized in Table 7 [3, 219]. Quality control issues must also be considered, as they critically influence measurement validity [220, 221]. Meaningful DXA interpretation requires both precision and accuracy. Precision depends on factors such as equipment stability, standardized patient positioning, and consistent image analysis [4]. Errors in indication occur when scans are ordered for low-risk individuals without justification or omitted in high-risk patients, leading to unnecessary costs and missed diagnostic opportunities.

| Category | Common errors/issues |

|---|---|

| Quality control |

|

| Indication |

|

| Acquisition |

|

| Data analysis |

|

| Interpretation and reporting |

|

DXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; BMD: bone mineral density; ROI: region of interest.

Adherence to evidence-based guidelines is therefore essential to optimize patient selection [224]. Quality assurance procedures, including routine phantom scans, calibration, and determination of the least significant change (LSC), are key to maintaining consistency. Cross-calibration across scanners, as recommended by the ISCD, is equally important [4]. Failure to uphold these standards, such as neglecting calibration or monitoring variability, can compromise BMD accuracy and lead to inappropriate clinical decisions [4].

Incorrect patient positioning is a major source of DXA error, particularly in hip and lumbar spine scans. For accurate lumbar imaging, the patient should lie supine with hips and knees flexed at 90° to minimize lumbar lordosis and enhance vertebral visualization. Proper trunk and limb alignment reduces soft tissue variability, and consistent positioning across serial scans ensures measurement reproducibility. Positioning aids, such as foam blocks or head supports, facilitate alignment and image quality [4]. The lumbar spine region of interest (ROI) should include vertebrae L1 to L4 in PA view, analyzing only structurally intact segments free of artifacts. Vertebrae with abnormalities may be excluded if at least two remain for analysis; if only one is evaluable, another skeletal site should be used. Exclusion is also warranted when a vertebra’s T-score differs by > 1.0 from adjacent levels. The final T-score is calculated using the remaining valid vertebrae. The lateral spine is not recommended for diagnosis but may be used for follow-up [3, 4]. Vertebral Fracture Assessment (VFA), a densitometric lateral spine image, is indicated when the T-score is < –1.0 and at least one of the following criteria is met: women ≥ 70 years or men ≥ 80 years, historical height loss > 4 cm, prior unconfirmed vertebral fracture, or glucocorticoid therapy ≥ 5 mg prednisone (or equivalent) daily for ≥ 3 months [4, 45]. For hip DXA, bilateral measurement is recommended, as BMD is usually symmetrical but may differ due to immobilization or asymmetric loading. The total hip ROI should include the femoral neck, proximal femur, and trochanteric regions, excluding the greater trochanter. The patient’s legs should be straight and parallel, with 15–20° internal rotation to align the femoral neck with the scanning plane; minimal visibility of the lesser trochanter confirms proper positioning. Foot positioners and straps maintain alignment. Soft tissue misidentification and ischial overlap must be corrected. Both the total hip and femoral neck should be analyzed, using the same (typically non-dominant) hip for follow-up [4, 45]. Forearm DXA of the non-dominant arm is indicated when spine or hip sites are unsuitable due to artifacts (fractures, implants, severe degeneration) or when proper positioning is not possible. The diagnostic site is the one-third (33%) radius, mandatory in primary hyperparathyroidism, and useful when spine-hip discordance exceeds 1 T-score. The radius and ulna should be parallel to the table’s short axis, free of fractures or hardware. Manufacturer protocols differ: Hologic systems do not require a positioner, whereas GE systems do. For Hologic devices, forearm length from the styloid to the elbow must be entered manually. Correct positioner use is essential to prevent artifacts. Although scans are usually performed seated, a supine position may minimize motion artifacts in select cases [4, 45].

Errors in DXA interpretation arise from incorrect data analysis or clinical judgment, leading to misclassification of bone density status, inappropriate application of T- or Z-score criteria, or failure to recognize artifacts and anatomical abnormalities that distort measurements. Such inaccuracies can result in misdiagnosis, suboptimal treatment decisions, or failure to identify patients at high fracture risk. To ensure diagnostic reliability, clinicians should adhere to ISCD recommendations emphasizing appropriate staff training, routine equipment calibration, standardized scan acquisition, and interpretation within the broader clinical context. Reporting errors, in turn, involve inaccuracies or omissions in the communication of DXA findings, such as incorrect diagnostic categorization, misapplied T-score thresholds, or neglect of relevant clinical risk factors. These errors can lead to inappropriate management decisions and underscore the importance of standardized reporting practices [3, 219–223]. As noted, reporting inaccuracies are common in clinical practice, with studies showing that up to 90% of BMD reports contain at least one error [217]. Krueger et al. [216] assessed DXA-related errors in a U.S. clinical population referred for OP evaluation and analyzed their potential clinical impact. Major errors, defined as inaccuracies that could alter patient management, were observed in 42% of cases, while technical errors occurred in 90% and influenced interpretation in 13% of patients. The most frequent major errors involved incorrect reporting of BMD change (70%) and misdiagnosis (22%). Implementation of a standardized reporting template in the study’s second phase reduced major errors by 66%, highlighting the value of structured reporting systems [216]. Similar findings were reported in an analysis of densitometry procedures across imaging centers in Ecuador, where patient positioning errors, including improper centering or misalignment, occurred in 21.4% of cases. In 38.5% of scans, the assessed vertebral region did not correspond to L1–L4, while artifacts such as metallic implants were identified in 3.5%. The ROI was incorrectly defined in 24.1% of lumbar and 19.9% of femoral assessments [3]. Lewiecki et al. [223] evaluated perceptions of DXA quality among 3,488 clinicians and 2,362 technologists from the ISCD. Over half of technologists (55%) reported incorrect entry of patient demographic data at least monthly, and 71% of clinicians identified inaccurate interpretations with the same frequency; 27% noted errors more than once per week. Nearly all clinicians (98%) believed low-quality DXA reports negatively affected patient care, with 59% rating the impact as moderate or severe [223].

OP constitutes a major global health challenge, given its silent progression and the severe consequences of fragility fractures. Effective management extends beyond reliance on bone densitometry and requires a comprehensive approach that incorporates metabolic conditions, comorbidities, vitamin D status, and concomitant medication use. Addressing these factors is essential to minimize misdiagnosis, avoid inappropriate treatments, and prevent potentially serious complications. High-quality DXA scanning, conducted under rigorous quality assurance protocols and interpreted within the clinical context, remains central to accurate diagnosis and monitoring. Numerous comorbidities significantly influence bone health and fracture risk. For example, patients with IBD, chronic PPI use, liver disease, renal insufficiency, or rheumatic inflammatory disorders present with disease-related skeletal vulnerability compounded by the pharmacologic therapies required for treatment. Likewise, individuals with dementia or cognitive impairment are predisposed to falls, further amplifying fracture risk, while older adults exposed to polypharmacy warrant personalized evaluation due to the additive impact of multiple medications. Together, these considerations underscore the importance of an individualized, multidisciplinary approach to OP care, aimed at improving diagnostic accuracy, tailoring interventions, and ultimately reducing fracture incidence and its associated burden.

25OHD: 25-hydroxyvitamin D

aBMD: areal bone mineral density

ALD: alcoholic liver disease

ALP: alkaline phosphatase

BMC: bone mineral content

BMD: bone mineral density

BSAP: bone-specific alkaline phosphatase

CAG: chronic atrophic gastritis

CD: celiac disease

CKD: chronic kidney disease

CRP: C-reactive protein

CTX: collagen type I C-telopeptide

DGP: deamidated gliadin peptides

DISH: diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

DKK1: dickkopf-1

DM: diabetes mellitus

DXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate

ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate

FGF-23: fibroblast growth factor 23

GC: glucocorticoids

GnRH: gonadotropin-releasing hormone

H2RA: histamine-2 receptor antagonist

HD: hemodialysis

HP: Helicobacter pylori

HPP: hypophosphatasia

HR: hazard ratio

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease

IJO: idiopathic juvenile osteoporosis

IL-6: interleukin 6

IOF: International Osteoporosis Foundation

ISCD: International Society for Clinical Densitometry

LSC: least significant change

MBD: mineral and bone disorder

M-CSF: macrophage colony-stimulating factor

MIP-1α: macrophage inflammatory protein-1α

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

NKF/KDOQI: National Kidney Foundation/Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative

NTX: N-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen

OI: osteogenesis imperfecta

OP: osteoporosis

P1NP: procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide

PA: posterior-anterior

PD: Parkinson’s disease

PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor

PPIs: proton pump inhibitors

PSA: prostate-specific antigen

PTH: parathormone

PTHrP: parathyroid hormone-related peptide

QCT: quantitative computed tomography

RA: rheumatoid arthritis

RANK: receptor activator of nuclear factor κB

RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand

RDAs: recommended dietary allowances

ROI: region of interest

RoM: ratio of means

SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus

SREs: skeletal-related events

SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

TBLH: total body less head

TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone

tTG: tissue transglutaminase

vBMD: volumetric bone mineral density

VDR: vitamin D receptor

VFA: Vertebral Fracture Assessment

XLH: X-linked hypophosphatemia

MV and NEL: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Both authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1652

Download: 33

Times Cited: 0