Affiliation:

Department of Translational Research, College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, CA 91766, USA

Affiliation:

Department of Translational Research, College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, CA 91766, USA

Affiliation:

Department of Translational Research, College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, CA 91766, USA

Affiliation:

Department of Translational Research, College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, CA 91766, USA

Affiliation:

Department of Translational Research, College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, CA 91766, USA

Email: vrai@westernu.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6286-2341

Explor Endocr Metab Dis. 2026;3:101457 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eemd.2026.101457

Received: October 28, 2025 Accepted: December 23, 2025 Published: January 21, 2026

Academic Editor: Alister C. Ward, Deakin University, Australia

The article belongs to the special issue Role of Dysregulated Cytokine Signaling Pathways in Metabolic Disease

A pro-inflammatory state with elevated cytokines influenced by both environmental and genetic factors is a key characteristic of both type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Cytokines promote immune cell infiltration and degradation of the pancreatic islets, which play a direct role in the development of insulin resistance in T1DM. Cytokines also interfere with insulin signaling pathways and lead to metabolic dysfunction, contributing to the development of insulin resistance in patients with T2DM. In this narrative review, we have discussed the mechanisms of action and specific effects on insulin resistance of different cytokines, the influence of single-nucleotide polymorphisms and genetic factors that alter cytokine levels, and the development of insulin resistance. Further, we have discussed the complication of diabetes with a focus on diabetic foot ulcers, wounds, impaired wound healing, and reduced angiogenesis in association with the role of cytokines. Finally, the discussion addresses interventions for managing cytokines, such as Treg-based therapies, along with the various challenges presented by therapies targeting cytokine dysregulation and their effects on insulin resistance.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a complex metabolic disorder characterized by impaired glucose regulation, chronic inflammation, and progressive end-organ complications. Central to its pathophysiology is the role of cytokines, which are small signaling proteins that regulate immune responses, inflammation, and tissue repair [1]. Both type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) diabetes are influenced by cytokine imbalances driving disease initiation and progression. In T1DM, pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and IL-17, play critical roles in the immune-mediated destruction of pancreatic β cells. In T2DM, cytokines secreted by adipose tissue (IL-6, IL-1, and TNF-α), hepatocytes, and immune cells contribute to insulin resistance, impaired signaling, and β-cell dysfunction. Genetic variations in cytokine-related pathways increase susceptibility to diabetes and its complications [1]. Obesity is strongly associated with diabetes, with the link being driven by chronic, low-grade inflammation originating from hypertrophied adipose tissue. As fat cells grow to their storage limit, they attract inflammatory immune cells, particularly macrophages. These macrophages shift to a pro-inflammatory “M1” state and begin releasing a stream of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. These cytokines interfere with the body’s response to insulin, leading to insulin resistance. This disruption impairs the insulin-mediated process that moves glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) to the cell membrane. With less GLUT4 at the surface, cells cannot efficiently absorb glucose from the bloodstream, causing high blood sugar levels [1, 2]. Insulin resistance significantly increases pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, creating a vicious cycle where inflammation further impairs insulin signaling in fat, muscle, and liver, driving metabolic dysfunction, T2DM, and chronic low-grade inflammation throughout the body, involving immune cells like macrophages and T cells [3].

Beyond systemic glucose dysregulation with insulin resistance, cytokine imbalance also drives secondary pathologies such as diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), one of the most debilitating complications of diabetes. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-8, coupled with insufficient regulatory cytokines like IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, create a chronic inflammatory environment that prevents wound healing [4, 5]. This state is exacerbated by defective macrophage polarization, impaired angiogenesis, altered extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, and dysregulated crosstalk among key signaling pathways, such as nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB) and NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes, belonging to the NLR family. These mechanisms highlight how cytokines are not merely bystanders but active mediators in both the metabolic and immunological disturbances of DFUs [5]. Understanding the multifaceted roles of cytokines provides a crucial framework for exploring novel therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring immune balance, improving glycemic regulation, and accelerating tissue repair in diabetic patients. This review comprehensively summarizes the role of dysregulated cytokines in the pathophysiology of DM and DFU, followed by the potential of using cytokines as therapeutic targets.

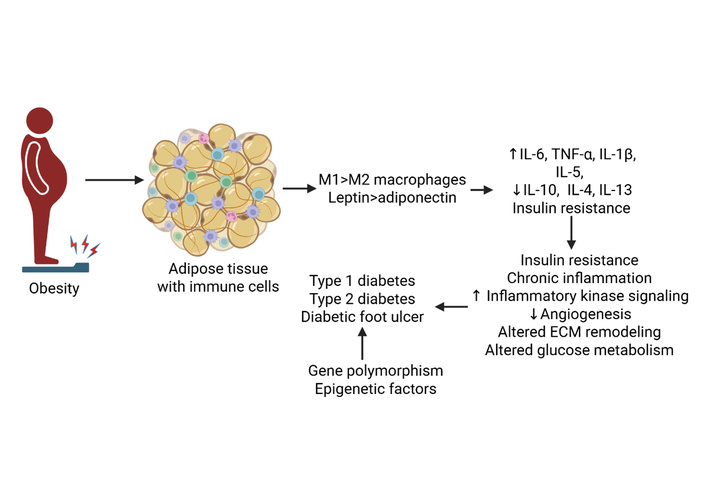

Diabetes is characterized by a chronic proinflammatory state, with elevated levels of circulating cytokines contributing to the disease’s development. This inflammatory link is further supported by genetic research linking variations in cytokine-related genes of inflammatory responses with complications of T2DM. Epidemiological studies reveal a greater prevalence and severity of periodontitis in people with diabetes, suggesting that a shared genetic susceptibility, such as polymorphisms in the gene IL-1, may be a factor in both conditions [6]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, are implicated in insulin resistance and complications like diabetic nephropathy. In contrast, anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-4 and IL-13 can have protective effects in T1DM, while others like adiponectin are beneficial in T2DM. Cytokines also serve as potential biomarkers for early detection and as targets for novel therapeutic strategies [7–9] (Figure 1).

Cytokines in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Increased proinflammatory and decreased anti-inflammatory cytokines contribute to chronic inflammation, decreased angiogenesis, impaired extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, and insulin resistance, leading to the development of type 1 and type 2 diabetes and diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). IL: interleukin; TNF: tumor necrosis factor. Created in BioRender. Rai, V (2025) https://BioRender.com/dotvw7w.

In T1DM, the immune system progressively destroys the insulin-producing β-cells in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans, leading to reduced insulin secretion and hyperglycemia. This β-cell destruction is driven largely by pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β. The involvement of IL-1β is not limited to T1DM; it also contributes to chronic inflammation and β-cell dysfunction in T2DM. In vitro studies have shown that exposure of pancreatic islets to IL-1β, either alone or in combination with other cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ, leads to β-cell damage and impaired insulin secretion. These findings suggest that IL-1β plays a central role in β-cell stress and apoptosis under inflammatory conditions. Additionally, IL-21 is an important cytokine in the development of T1DM, whereas IL-4 and IL-13 have been associated with delayed disease onset and β-cell protection, possibly due to their anti-inflammatory properties. In T2DM, pro-inflammatory cytokines are central to the development of insulin resistance. IL-6 is an independent predictor of T2DM, and a combined elevation of IL-1β and IL-6 significantly increases risk. Excessive adipose tissue secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6, but also beneficial adipokines like leptin and adiponectin can help prevent hepatic insulin resistance [9–12] (Figure 1).

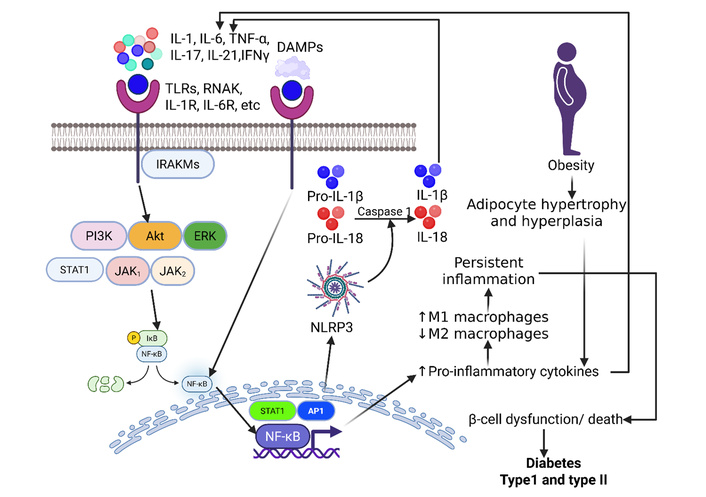

In T1DM, a process known as insulitis occurs, where immune cells infiltrate pancreatic islets, attacking and destroying the insulin-producing β cells. Cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, are key players, with some, like IL-1β and IFN-γ, promoting inflammation and others directly inducing β-cell death. This autoimmune destruction of β cells results in a lack of insulin and lifelong insulin dependence in affected individuals [13]. Immune system dysregulation can lead to β-cell destruction in T1DM through the action of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, IL-17, IL-21, and TNF-α, which promote the function and differentiation of immune cells that target β cells (Figure 2). These cytokines orchestrate the autoimmune response by activating harmful immune cells and contributing to the inflammatory environment that destroys these insulin-producing β cells [14–16]. However, regulatory T cells (Tregs) use suppressive cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β to dampen immune responses and maintain immune homeostasis. These cytokines inhibit the activation and proliferation of other immune cells, acting as a crucial mechanism to prevent autoimmune diseases and protect vital cells like β cells [17–19].

Chronic inflammation, β-cell dysfunction, and diabetes: ligand (cytokines)-receptor interaction activates cytoplasmic kinases leading to increased transcription of nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB), activator protein 1 (AP-1), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1). This results in increased production and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, perpetuating the inflammatory cascade and increased M1 macrophages. Chronicity of inflammation finally contributes to β-cell dysfunction or death. Interaction of damage-associated molecular proteins (DAMPs) with their receptors causes activation of NF-κB, followed by NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, contributing to increased IL-1β involving caspase 1. This results in the development of type I and type II diabetes. Akt: protein kinase B; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; IFN: interferon; IL: interleukin; IRAKM: interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 3; JAK: Janus kinase. PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; RANK: receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B; TLRs: toll-like receptors; TNF: tumor necrosis factor. Created in BioRender. Rai, V (2025) https://BioRender.com/soxbxwk.

While previous research, mainly from animal studies, had ambiguous or conflicting results about the role of IL-17, Arif et al. [20], using 50 human patients, reported the direct involvement of an immune protein called IL-17 in the destruction of insulin-producing β cells in humans. This study provides clear evidence that T-cells from T1DM patients secrete IL-17 in response to their own β cells [20]. The researchers found that this cytokine is present in the inflamed pancreas of patients at the onset of the disease, suggesting its key role in a multi-step process that leads to β-cell death. The study proposed a two-part pathway for β-cell death. It shows that other inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IFN-γ, act first to “prime” the β cells by making them highly susceptible to IL-17. This priming happens when the β cells, in response to these early inflammatory signals, increase their expression of the IL-17 receptor (IL-17RA). This leads to the activation of specific molecular pathways, such as signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and NF-κB, driving the destruction of β cells. This study fundamentally changes the understanding of β-cell destruction by showing that the β cells are not just passive victims; they actively participate in their own demise by becoming more vulnerable to the damaging effects of IL-17 [20]. The study also reported that the immune response involving IL-17-producing cells closely resembles that of TH1 cells. While the full scope of this β-cell-specific T-cell response is not yet fully understood, the study provides evidence that a prominent polarization toward the IL-17 pathway is actively promoted around the time of diagnosis. This finding is significant because the differentiation of these TH17 cells can be influenced by environmental factors, which align with evidence for non-genetic causes of the disease. Furthermore, since these cells are known to be more resistant to regulation by other immune cells, this could explain why the immune systems of T1DM patients are less “regulatable”. Given that human β cells are susceptible to IL-17, these findings provide a strong justification for developing new treatments that target the pathways of TH17 cells to halt their destructive activity [20].

Another study by Asif et al. [21], in their review, discussed how the innate immune system plays a crucial role in the development and progression of T1DM through complex cell-cell crosstalk. Various innate immune cells, including dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, contribute to the disease’s initiation and the destruction of insulin-producing β cells. For example, dendritic cells present β-cell antigens to T cells, activating the immune response, while pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages secrete destructive cytokines like IL-1β. However, these cells also possess the ability to regulate the immune system; for instance, some dendritic cells can promote immune tolerance, while M2 macrophages can support tissue repair. Other cells, like neutrophils and natural killer cells, contribute to β-cell destruction, but recent findings also highlight the potential of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) to protect β cells and promote immune regulation. Ultimately, the balance between these pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions shapes the pancreatic environment in T1DM, and strategies that shift this balance toward tolerance hold promise for future therapeutic interventions.

Like T1DM, pro-inflammatory cytokines also play a role in the pathogenesis of T2DM. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β are central to T2DM development, creating a chronic inflammatory state in fat tissue and elsewhere that worsens insulin resistance, impairs β-cell function, and drives disease progression by interfering with insulin signaling and recruiting more immune cells, forming a vicious cycle. In T2DM, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, often from visceral fat, trigger insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction. These pro-inflammatory signals interfere with insulin signaling pathways, contributing to the progression of T2DM and its complications. While some cytokines are pro-inflammatory, adipokines such as adiponectin can have beneficial effects, indicating a complex balance of these messengers in T2DM pathogenesis. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 directly interfere with the insulin signaling pathway by promoting the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates (IRS), which reduces insulin sensitivity [7, 12].

Pro-inflammatory cytokines disturb the insulin signaling pathway in many ways based on the cytokine/cytokine pathways and molecular mechanisms involved, which ultimately leads to the development of insulin resistance and progression to T2DM. Some cytokines, like TNF-α and IL-6, disrupt insulin signaling by affecting insulin receptors and preventing the tyrosine kinase cascade that leads to successful insulin signaling and glucose uptake via increased GLUT4 translocation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, contribute to insulin resistance by promoting the serine phosphorylation of IRS proteins, which impair insulin signaling and reduce glucose uptake in tissues like adipose tissue, muscle, and liver [22]. The c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway is activated by cytokines and plays a significant role in various inflammatory diseases through phosphorylation of a wide range of different substrates that lead to pathological processes [23]. The obesity and cytokine-induced JNK pathway can phosphorylate serine residues on IRS-1, which has an inhibitory effect on the receptor and prevents successful insulin signaling [24]. For example, TNF-α released by macrophages in adipose tissue promotes serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and is linked to increased insulin resistance in T2DM. Similarly, IL-6, secreted by adipocytes and macrophages, induces suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) expression, which degrades IRS proteins and disrupts insulin signaling, and IL-1β, secreted by activated macrophages, plays a significant role in inflammation-mediated insulin resistance [7].

In addition to serine phosphorylation, certain cytokines can also induce the production of nitric oxide-derived reactive nitrogen species, which can cause nitration of tyrosine residues on IRS proteins, further impairing signaling. Cytokines can also directly interfere with other signaling molecules further down the insulin pathway, like protein kinase B (Akt), contributing to insulin resistance [1, 25]. IL-6 plays a more indirect role in inhibiting the insulin signaling pathway by lowering IRS-1 expression and through other ways, instead of direct inhibition of the receptor. The cytokine IL-6 has different roles, including those relating to inflammation promotion. Chronic exposure to IL-6 has been shown to lead to decreased transcription of both IRS-1 and GLUT4, which are both critical to successful insulin signaling and responses [26]. Cytokines secreted in response to obesity also indirectly contribute to insulin resistance via lipotoxicity and increases in circulating free fatty acids (FFAs). Pro-inflammatory cytokines lead to adipocyte hypertrophy, increased lipolysis, and the release of FFAs, which affect the insulin signaling pathway [27]. These FFAs activate toll-like receptor (TLR)-4, which regulates the insulin signaling pathway and whose activation leads to increased insulin resistance [28].

Chronic and low-grade inflammation resulting from inflammatory cytokines can lead to insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction via decreased insulin secretion, disruption of normal glucose and lipid metabolism, and other mechanisms related to inflammation. These inflammatory cytokines interfere with the insulin receptor signaling cascade, inhibiting glucose uptake by cells, particularly in the liver and adipose tissue. Pro-inflammatory cytokines also contribute to lipid accumulation in organs like the liver and adipose tissue, further aggravating metabolic dysfunction [26, 29]. The β cells responsible for secreting insulin can be adversely affected by inflammatory states and immune cell infiltration stimulated by cytokines. For example, IL-1 cytokine signaling has been shown to impair β-cell proliferation and mass. IL-1 signaling promotes an inflammatory state that secondarily recruits macrophages that can potentially damage the β cells within pancreatic islets. Inflammation can also lead to amyloidosis, which is associated with β-cell apoptosis [30].

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and alterations in cytokines can also contribute to the risk of developing insulin resistance and T2DM. SNPs in cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α are commonly associated with the increased risk for the development of insulin resistance. Studies have shown that individuals with the IL-6 rs1800796 G allele are at higher risk for developing gestational DM. This allele results in increased IL-6 levels, which promote more inflammation and adverse effects on insulin signaling and innate immune cell proliferation, which can lead to insulin resistance. SNPs in the gene corresponding to TNF-α have also been shown to decrease insulin secretion via more effective binding of transcription factors and increased expression of TNF-α [31]. Further, IL-10-1082 A/G polymorphism is another key example where the G allele and GG genotype have been linked to T2DM in certain populations, suggesting a role in insulin resistance [32]. Variations in other cytokine genes, such as IL-1β, IL-18, TNF-α, and IL-4, have also been investigated for their potential association with T2DM and its related features, like obesity and hypertension [33]. Polymorphisms can alter cytokine levels, leading to an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines that promote insulin resistance. SNPs within the regulatory regions of cytokine genes can impact the amount of cytokine produced. This dysregulated expression can lead to variations in immune responses, which in turn affect the progression of T2DM.

Each cytokine plays a specific role in diabetes pathogenesis, and the overall outcome is determined by a complex balance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. In both T1DM and T2DM, this balance is disrupted, leading to inflammation that contributes to the destruction of insulin-producing β cells, promotes insulin resistance, and fuels related complications (Table 1).

Specific role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

| Cytokine | Mechanism of action | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α [34] | Via promotion of the JNK pathway and phosphorylation of the serine residues on the IRS-1 receptor. | Disruption of insulin signaling pathways, insulin resistance, and disrupted glucose uptake. |

| IL-6 [35] | IL-6 has been shown to reduce GLUT4 and IRS-1 expression, which can have potentially deleterious effects on insulin secretion. | IL-6 can counterintuitively promote glucose uptake in muscle cells and have a beneficial role in decreasing blood glucose. However, IL-6 levels are low in muscle cells in obese patients and those with type 2 diabetes. |

| IL-1 [30] | As previously mentioned, IL-1 cytokine signaling has been shown to impair β-cell proliferation and mass. IL-1 signaling promotes inflammation and amyloidosis. | Inflammation secondarily recruits macrophages, which can potentially damage the β cells within pancreatic islets. IL-1 also leads to amyloidosis of the islets, which is associated with β-cell apoptosis and decreased insulin secretion. |

| IL-18 [36] | IL-18 can act through the activation of the AMPK and STAT3 signaling pathways. | IL-18 normally has a positive role in blood glucose regulation via stimulation of glucose uptake and phosphorylation of STAT3. However, IL-18 levels are significantly increased in patients with type 2 diabetes, nonetheless. |

| Adiponectin [37] | Adiponectin plays a beneficial role in insulin signaling by acting as an insulin-sensitizing hormone, as it leads to the activation of the AMPK pathway. | Activation of the AMPK pathway increases glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation, which have positive effects in terms of managing blood glucose. Higher levels of Adiponectin are associated with insulin sensitivity, while lower levels are associated with type 2 diabetes. |

| Resistin [38] | Resistin promotes insulin resistance by increasing phosphorylation of the serine residues on the IRS-1 receptor. Resistin also binds to TLR4 and activates the JNK pathway. | IRS-1 inhibition leads to decreased downstream glucose uptake via decreased GLUT4 translocation.Activation of the JNK pathway leads to inflammation and ER stress that can exacerbate insulin resistance. Liver insulin sensitivity is also impaired, which can lead to increased liver gluconeogenesis and insulin resistance. |

| IL-27 [13] | Secreted by APCs like dendritic cells and macrophages, which results in activation of STAT family proteins and the MAPK pathway. | Promotes the infiltration and accumulation of T cells and APCs onto the pancreatic islets, which can potentially cause damage and subsequent insulin resistance. |

| IL-10 [19] | Acts as an anti-inflammatory TH2-type cytokine by inhibiting TNF-α and IL-6 secretion via the STAT3 signaling pathway. | It has been shown to increase β-cell functions and insulin secretion. Decreases macrophages and cytokine infiltration in muscle cells, which helps protect against insulin resistance. |

| IL-4 [17, 18] | Upregulates glucose uptake in adipocytes without activating the IRS-1 pathway and other normal insulin signaling pathways, but has been shown to decrease insulin secretion over the long term. | It has complex effects on insulin resistance, as it has been shown to have positive effects in managing glucose levels via adipocyte glucose intake, but it may also have detrimental effects over time, as long-term IL-4 decreases insulin secretion. |

| IL-5 [15, 16] | Helps promote eosinophilia and inflammation through activation of the JAK-STAT and Ras/Raf ERK signaling pathways. | IL-5 may have a protective role against insulin resistance, as IL-5 deficiency has been shown to decrease oxidative metabolism and increase adipose tissue growth and potential metabolic impairment. |

| IL-13 [14] | Produced by TH2 cells and activates the JAK/STAT signaling cascade and PI3K pathway. It acts as an anti-inflammatory cytokine by suppressing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α. | Limits adipose tissue inflammation and promotes the survival of β cells and IRS-2 expression, which have beneficial effects in stopping the development of insulin resistance. |

AMPK: 5’ AMP-activated protein kinase; APCs: antigen-presenting cells; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GLUT4: glucose transporter 4; IL: interleukin; IRS: insulin receptor substrates; JAK: Janus kinase; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; STAT: signal transducer and activator of transcription; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines (like TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) drive peripheral neuropathy by causing nerve damage (demyelination, axonal degeneration), activating immune cells (macrophages, T cells) to infiltrate nerves, disrupting the blood-nerve barrier, and sensitizing pain receptors (nociceptors), leading to chronic neuropathic pain in conditions like diabetes or chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, with these cytokines acting as key biomarkers and therapeutic targets for new anti-inflammatory treatments. Cytokines like IL-8 attract inflammatory cells (neutrophils, macrophages) to the nerve, which release more inflammatory mediators. TNF-α directly causes demyelination and axonal degeneration (Wallerian degeneration). IL-1β and IL-6 promote inflammation, oxidative stress, and dysfunction in Schwann cells. These mediators activate nerve endings (nociceptors) and central nervous system pathways, increasing pain sensitivity (allodynia/hyperalgesia). Cytokines like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) increase vascular permeability, allowing immune cells to enter the nerve. Elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β can predict neuropathy risk, as seen in diabetic patients [39–41]. Blocking these cytokines (e.g., with anti-cytokine agents) or their signaling pathways offers potential for new treatments for chronic neuropathic pain.

DFUs are chronic inflammatory diseases as a consequence of persistent and uncontrolled hyperglycemia. Chronic inflammation, decreased angiogenesis, and altered ECM contribute to the nonhealing of the DFU. This happens because chronic inflammation halts the healing of the wound in the inflammatory phase. Without progression into the resolving phase, increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-8, plays a critical role in the pathogenesis [4, 5].

Cytokine imbalance plays an important role in DFUs. Liu et al. [42], in their review, reported that an increase in TNF-α and a decrease in IL-10 lead to defects in the innate immune system, where macrophages that normally should switch from pro-inflammatory M1 pathway to M2 (pro-repair pathways) are defective in DFU patients. This leads to defective transient mechanisms through prolonged M1 phase with little to no M2 involvement (Table 2).

Role of various cytokines in the pathogenesis of diabetic foot ulcers.

| Cytokine/Pathway | Molecular and cellular effects | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8 [43] | Prolongs inflammation, decreases angiogenesis, and alters ECM remodeling. Persistent inflammation, disruption of normal healing. | Pro-M1 activation (promotes inflammation). |

| TNF-α (↑), IL-10 (↓) [42] | Imbalance leads to innate immune defects.IL-10 secreted from Treg cells plays a role in M2 activation.Defective transition, prolonged M1 phase, little to no M2 involvement. | Imbalance prevents the M2 pathway from becoming activated and prolongs M1 activation. |

| NF-κB [44] | Master-regulatory Inflammatory pathway.Activation leads to increased TNF-α secretion.Prolonged inflammation and ECM degradation. | Activated by hyperglycemia, AGEs, and oxidative stress.Upregulates TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and MMPs. |

| IFN-γ [45] | Prolongs inflammation Impaired wound healing | Stimulates TNF-α and IL-1β byMacrophages. |

| IFN-α/β [45] | Type I interferons are linked to impaired healing.Reduced angiogenesis and delayed granuloma formation. | Suppresses VEGF limits vascularization. |

| IFN-κ [46] | Promotes wound repair when restored.Accelerates closure in preclinical models. | Enhances re-epithelialization and collagen organization. |

| IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α [43] | Inflammatory mediators linked to chronicity.Restores normal inflammatory timing and reduces chronic inflammation. | Prolonged cytokine peaks; NPWT shifts peak earlier. |

| TNF-α, IL-β, IL-6 [43] | ChronicM1 activation, inflammation, and delayed healing. | Persistent elevation leads to ECM degradation and a repair block. |

| IL-10, TGF-β, IGF-1 [44] | M2-associated markers: impaired angiogenesis, repair, and Treg promotion. | Suppressed in DFUs. |

AGEs: advanced glycation end products; DFUs: diabetic foot ulcers; ECM: extracellular matrix; IFN: interferon; IGF: insulin-like growth factor; IL: interleukin; MMPs: matrix metalloproteinases; NPWT: negative pressure wound therapy; TGF: transforming growth factor; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

Increased pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in DFUs disrupt the normal healing process, creating a persistent inflammatory state that damages tissue and impedes re-epithelialization, fibroblast function, and angiogenesis. Impaired angiogenesis and reduced cell proliferation converge to prevent effective closure of DFUs. Persistent pro-inflammatory cytokines trap wounds in the inflammatory phase, preventing transition to tissue formation and remodeling [47]. Neutrophil and macrophage activity remains excessive, protease release is prolonged, and macrophages fail to shift from the inflammatory M1 to the reparative M2 phenotype. The impaired transition of macrophages disrupts the local signaling required for the appropriate production and release of growth factors needed for healing. Chronic inflammation in DFUs creates a detrimental wound microenvironment that disrupts the normal healing cascade by impairing the production and function of essential growth factors, impeding angiogenesis, and dysregulating immune cells like macrophages. Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 disrupt cellular processes, leading to insufficient growth factor signaling necessary for tissue repair, proliferation, and the timely formation of new blood vessels, which ultimately hinders DFU healing and contributes to chronicity [43]. With VEGF and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) suppressed, oxygen delivery and granulation remain inadequate [44, 48]. Diabetes-related neuropathy and vascular insufficiency exacerbate these effects, resulting in ulcers that may persist for months or years. Clinically, these wounds are resistant to therapy, promote biofilm growth, and significantly increase the risk of amputation [49]. Chronic inflammation, therefore, locks DFUs in a non-healing state, making cytokine rebalancing essential for recovery.

IFNs play a central role in antiviral immunity and influence wound repair. Elevated IFN signaling, particularly IFN-γ and type I IFN (IFN-α/β), has been implicated in impaired wound healing. IFN-γ prolongs inflammation by stimulating the production of TNF-α and IL-1β by macrophages, while IFN-α/β suppresses VEGF, thereby limiting vascularization [45]. Preclinical studies in diabetic wound models show that excessive IFN activity delays granulation tissue formation, whereas targeted modulation can improve outcomes. For instance, restoration of IFN-κ signaling has been shown to enhance re-epithelialization and collagen organization in murine models [46]. Although clinical evidence remains sparse, IFNs clearly act as a double-edged sword: chronic overexpression exacerbates ulcer chronicity, while carefully modulated application may accelerate closure.

NF-κB is often regarded as the central master inflammatory pathway activated by hyperglycemia, advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and oxidative stress, all seen in DFUs, leading to upregulation of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and increased matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Nrf2 is a transcription factor that checks NF-κB by promoting antioxidant protein production and downregulating NF-κB expression. Patients with DFUs cannot express Nrf2 as readily, leading to prolonged NF-κB expression. Furthermore, NLRP3 inflammasome amplifies IL-1β production. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and TLR signaling (especially TLR4) crosstalk with NF-κB, causing chronic activation and cytokine release. Dysregulated miRNAs cannot suppress cascades, drive continuous M1 pro-inflammatory states, decrease M2 transition, and impair Treg function [50]. With poor angiogenesis and increased MMPs (excess ECM remodeling/degradation) from chronic activation, therapeutic approaches should inhibit NF-κB, inflammasome activity, enhance Nrf2, or promote M2 polarization [50].

DFUs are marked by chronic inflammation and hyperglycemia. This leads to a profound cytokine imbalance. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) remain upregulated, while anti-inflammatory and pro-healing factors (IL-10, TGF-β, VEGF) are downregulated. This affects key pathways, like NF-κB and MAPK, disrupting mechanisms required for wound healing [48]. This disrupted cytokine environment has downstream effects on wound-healing cells [51]. For example, the increased presence of TNF-α and IL-1β inhibits both the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes, while continued activation of NLRP3 further impairs keratinocyte mobility. Consequently, the granulation tissue formed is weak and nonfunctional [46]. These cellular dysfunctions set the stage for subsequent complications affecting the vascular and structural aspects of wound repair. Building on this, endothelial dysfunction emerges as a major barrier to healing because angiogenesis is severely impaired. TNF-α and IL-1β drive reactive oxygen species (ROS) and protease activities while activating NF-κB, actions that inhibit VEGF signaling and induce endothelial apoptosis [45]. Additionally, p38 MAPK activation by IL-1β and decreased TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling further impede new vessel formation [46].

These changes in the vascular and inflammatory environments directly influence ECM remodeling in DFUs. The imbalance in cytokines increases MMPs (e.g., MMP-9) activity, leading to degradation of structural proteins such as collagen and fibronectin [44]. Simultaneously, fibroblasts in this pathogenic setting generate less ECM, which creates structural voids in the matrix and ultimately halts the tissue remodeling phase due to a lack of effective substrate for cell adhesion and growth factor signaling [46, 50]. The interconnectedness between cellular, vascular, and structural defects emphasizes the complexity of impaired wound healing in DFUs. A persistent presence of M1 macrophages and persistently high TNF-α, IL-β, IL-6, iNOS, and MMP-9 leads to inflammation, ECM degradation, and impaired repair [44].

The persistent inflammation mediated by TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in DFUs hinders the proliferation, migration, and functioning of critical cellular populations, including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes needed for key healing events such as collagen deposition, ECM formation, and re-epithelialization[52]. This results in MMPs-mediated collagen degradation and reduction in growth factors, eroding the repairing scaffold [42]. This leads fibroblasts toward senescence and reduced ECM production and compromises wound closure with fragile tissue. Fibroblasts’ heterogeneity and plasticity, regulated by cytokines, also play a role in impaired healing by affecting ECM production and angiogenesis [53]. Further mechanistic insights have described roles for cytokines such as TNF-α secreted from M1 macrophages, which upregulate keratinocyte expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP) -1, thereby restricting keratinocyte motility. Additionally, IL-1β drives ECM remodeling through p38 MAPK pathway activation, which upregulates MMP2 and MMP9 while downregulating TIMP1 and TIMP2 [54]. Long-term NLRP3 inflammasome activation also slows cell proliferation and migration throughout the healing process by increasing IL-1β secretion [55]. Together, these effects underscore how disrupted cellular dynamics are central to impaired wound repair and link to subsequent pathological features, such as impaired angiogenesis and altered ECM remodeling.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1β disrupt new blood vessel formation in DFUs. They induce more ROS and protease production, which degrade the ECM and destabilize new vessels [56]. Additionally, they suppress angiogenic growth factors, including VEGF and PDGF, which further decreases endothelial proliferation and vessel support [48]. These effects lead to hypoxia and reduce nutrient delivery to the wound, delaying healing. Excess pro-inflammatory cytokines turn the microenvironment anti-angiogenic. This imbalance blocks blood vessel formation and worsens tissue damage. TNF-α causes endothelial, keratinocyte, and fibroblast apoptosis, all crucial for healing and angiogenesis. Persistent IL-6 and IL-1β restrict endothelial cell migration and lower TGF-β, a key pro-angiogenic factor. Dominance of M1 macrophages and decreased transitions to M2 macrophages, which are essential for anti-inflammatory and pro-angiogenesis, also contribute to reduced angiogenesis. Further, the presence of more anti-angiogenic fibroblasts than pro-angiogenic types reduces angiogenesis and prevents wound healing in DFU [53, 57–60]. Studies show that boosting angiogenesis can improve DFU outcomes. For example, stem-cell-based therapies are promising [61]. Impaired angiogenesis keeps wounds chronically nonhealing by starving them of oxygen and nutrients. TGF-β signaling effect on angiogenesis in DFUs is complex and structure-dependent. For example, lower growth differentiation factor 10 (GDF-10), a TGF-β family member, inhibits TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling and impairs wound healing [62].

In DFUs, cytokine imbalance leads to chronic inflammation. This stops proper ECM remodeling and leaves wounds non-healing. High pro-inflammatory cytokines, like TNF-α, boost MMPs that break down collagen and fibronectin excessively [60]. The result is poor formation of stable new tissue. DFU fibroblasts produce less fibronectin and collagen [58], so a functional provisional matrix cannot form. This matrix is vital for cell migration and tissue restoration. Even new ECM proteins are poorly organized. The ECM layer is dysfunctional, hindering cell attachment, proliferation, and healing [60]. Cells, especially fibroblasts, respond weakly to growth factors like TGF-β, which normally regulate ECM production. In DFUs, wound fibroblasts show a weak or abnormal response to these signaling molecules [63].

Chronic inflammation causes delayed healing in DFUs by reducing epithelialization and creating a non-healing, hyper-inflammatory state [63]. Acute inflammation is needed for healing, but diabetes extends and disrupts this stage. Prolonged inflammation creates a cycle of tissue damage and blocks the proliferative phase, including re-epithelialization [52]. Persistently high inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, directly impair keratinocyte migration needed for wound closure [60]. Long-term pro-inflammatory immune cells boost MMP production. Normally, MMPs help remodel the ECM. In DFUs, their higher activity breaks down vital proteins and growth factors for epithelial cells. Glucose also forms AGEs, which block cell communication and damage keratinocytes and fibroblasts. This further impairs epithelial cell movement, causing slow epithelialization and wound closure [64]. Diabetes-related vascular disease compounds the problem by lowering blood flow. This creates hypoxia, which deprives cells of oxygen and energy essential for healing.

To regulate cytokine imbalance in DFUs, a shift is needed from a pro-inflammatory to a pro-regenerative state [65]. DFUs have high TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, and low anti-inflammatory and growth cytokines. In chronic DFUs, M1 macrophage accumulates and inhibit healing. Clinical therapies are designed to lessen this state and switch from pro-inflammatory to reparative M2 macrophage that releases growth factors. Therapeutic strategies, therefore, aim not simply to suppress inflammation but to restore appropriate immune balance and timing, allowing transition toward an M2-dominant, pro-regenerative environment.

Preclinical evidence has shown that engineered human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells that over-express IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 can modulate the macrophage phenotype to facilitate healing. The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-37 promotes healing in diabetic mice by inhibiting the MAPK/NLRP3 pathways and decreasing secretion of TNF-α and IL-1β [44]. Driver et al. [66], in a prospective, randomized clinical study with 17 patients, reported that increased oxygen therapy decreases IL-6 and IL-8 as well as MMPs. These points to M1 cytokine pathways, maintaining chronicity in ulceration, and oxygen therapy promote healing by attenuating cytokines. Yang et al. [67], using male C57BL/6J diabetic mice, offered the application of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells as a method for correcting immune dysregulation by promoting immunohomeostasis. Lin et al. [44] documented that ON101, which decreases M1 while stimulating M2 polarization, mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes, and miRNAs, may modulate NF-kB, STAT, and PI3/Akt signaling to elicit effects of NF-kB and STE4 activity. This may also increase IL-10 and VEGF pathways, promoting Treg and angiogenesis. Stem cell therapies, topical insulin, etc., could all provide IL-10 and VEGF to promote Tregs and potential angiogenesis, while antioxidants may block NF-kB activation. These works emphasize that correcting cytokine imbalance in DFUs is not just about suppressing inflammation but about reestablishing the appropriate timing and regulation of immune responses.

It should also be noted that the effects of IL-6 may be context-dependent. Increased IL-6 expression initially (acute inflammation) is beneficial, while chronicity (persistent and long-term chronic inflammation) is detrimental. An acute, physiological increase in IL-6 can be beneficial in DM and DFUs by improving glucose metabolism, stimulating insulin, and initiating wound healing, but chronic, high IL-6 levels, typical in diabetes, are detrimental, promoting inflammation and insulin resistance. Acute IL-6 acts like post-exercise signals, enhancing metabolic function, while chronic elevation drives disease pathology, though in DFU, acute IL-6 signals the start of healing, but excessive levels hinder repair. IL-6 initiates the inflammatory phase of healing, moving the wound toward repair. Elevated IL-6 signals the start of inflammation and infection in a wound, helping distinguish infected from non-infected ulcers [60, 68].

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been shown to modify inflammatory cytokine kinetics by advancing the peak of inflammation, decreasing chronic inflammation, and advancing the repair phase of inflammation [65]. Chiu et al. [65], using diabetic and obese male mice, highlighted the timing issue of cytokines during different phases of healing, with the notion that the persistent presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines is detrimental to the healing response. An early cytokine burst correlates with more favorable healing trajectories in DFUs. However, impaired immune crosstalk leads to the prolongation of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, leading to activated MMPs, leading to unfavorable chronic remodeling in DFU patients. The results suggested that NPWT reduced the time to peak cytokine production from 16 h to 2 h, in part returning to a more traditional inflammatory pattern and reducing overall inflammation. Therefore, it is not only critical to de-escalate inflammation but also to restore timing to bring about a successful immune response.

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have benefits beyond their glycemic control properties in decreasing circulating TNF-α and IL-6, which decreases systemic pro-inflammatory markers for a more favorable wound environment [69]. The process leading to this anti-inflammatory effect is quite complicated. In addition to improving hyperglycemia, SGLT2 inhibitors are thought to drive the body into a state of ketosis, which then inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome, a major initiator of IL-1β. Moreover, the medications can stimulate mitochondrial activity in endothelial cells and macrophages, thereby reducing oxidative stress and, subsequently, the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This scenario creates a less inflammatory environment throughout the body, which is no longer a candidate for chronic inflammation typical of DFU. Hence, the cellular processes necessary for repair are indirectly promoted. SGLT2 inhibitors have been proposed as a promising preventive and complementary strategy, as their multiple effects help address metabolic imbalance and inflammation simultaneously.

The literature shows that biologics used to manage cytokines, including TNF-α inhibitors (infliximab, etanercept) and IL-1 receptor antagonists (anakinra), enhance angiogenic processes, fibroblast function, and collagen deposition [70, 71]. The activity of these monoclonal antibodies and receptor antagonists is highly selective, as they target directly the cytokines responsible for the inflammatory phase and the death of cells related to healing. Take, for example, TNF-α inhibitors: the fibroblasts would then be responsive to growth factors, and the keratinocytes would not undergo TNFα-mediated apoptosis. Thus, re-epithelialization would continue. The increase in collagen deposition can be attributed to the liberation of fibroblasts from the inhibitory, catabolic state characteristic of the cytokine-rich environment [71]. On the other hand, Singh et al. [72], in their review, warn that this targeted immunosuppression, while very effective, will require the strictest patient selection and infection monitoring, because the very cytokines being blocked (for instance, TNF-α) are also vital for the body to be able to mount an effective immune response against pathogens.

Biologics in DFU infections involve using naturally derived or engineered substances (like growth factors, blood derivatives, or natural compounds) to speed healing, fight microbes, and reduce inflammation, often targeting persistent issues like bacterial biofilms and excessive oxidative stress that standard treatments miss, with approaches including autologous blood products, growth factor gels (like becaplermin), and novel topical agents that modulate inflammation and promote tissue regeneration. Recombinant human growth factors, such as PDGF (e.g., regranex), are delivered in a hydrogel to promote healing [73, 74]. Agents like WF10 (immunokine) include biologics (anti-TNF, anti-cytokines like IL-1, IL-12/23), small molecules [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, statins], and newer gene therapies (IL-10 gene therapy) that help regulate chronic inflammation [75, 76]. Though there is no direct evidence that these agents help in DFU healing, their role in other autoimmune diseases gives hope.

In DFU, the underlying cause of chronic inflammation is due to poor activity of Tregs. Pre-clinical studies suggest that cellular transfer or pharmacological stimulation to restore Treg activity can increase granulation tissue to heal wounds faster [47]. Tregs are the primary regulators of immune balance, and their impairment in diabetes leads to the activation of both T cells and macrophages, resulting in persistent inflammation that is difficult to resolve. Treatments aim to restore balance in the immune system by either supplying the patient with Tregs that have been expanded and tailored to the patient’s specific needs or by using drugs such as low-dose IL-2, which enhances the Treg population already present in the patient [77]. The significant increase in granulation tissue brought on by Tregs can be linked to the ability of this cell population to produce different factors, one of which is amphiregulin, while at the same time inhibiting the production of IFN-γ and other cytokines that are harmful to the growth of fibroblasts and endothelial cells [77]. Therefore, Treg-oriented therapy appears to be a major strategy that can not only suppress the inflammation but also invigorate the proliferative phase, thus assisting the healing process.

New approaches to treat inflammation are being developed while targeting inflammation more precisely. Decreasing IL-1β release through NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors, antioxidants to neutralize ROS, and growth factor-modulating agents through nanotechnology-based dressings can improve wound healing [45]. Having the ability to target the immune system without or less systemic immunosuppression will leave these therapies as a favorable option. Innovative strategies for anti-inflammatory treatments are being researched that target the site of inflammation with precision [78]. Among the possible approaches are the inhibition of IL-1β release with NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors, neutralization of oxidative damage with antioxidants, and the use of growth factor-modulating agents via nanotech-based dressings [78]. The NLRP3 inflammasome, a major intracellular sensor in chronic wounds, is triggered by damage-associated molecular proteins (DAMPs), and its blockade controls the potent IL-1β family of cytokines at the earliest stage [79]. At the same time, new antioxidant strategies take the process beyond simple antioxidant action; they can include the selective distribution of substances such as N-acetylcysteine to potentially interfere with the ROS-NF-κB inflammatory feedback loop. The introduction of nanotechnology in the form of dressings is a major milestone, as it not only provides the prolonged and site-specific release of these new agents (such as inflammasome inhibitors, growth factors, or antioxidants) at the wound site, thus maximizing the therapeutic effect while reducing the systemic exposure [80]. Such a precise, multi-targeted method, as the study suggests, not only selectively influences the immune system without the broad-spectrum immunosuppression side effects associated with regular biologics but is also a highly preferred future option [79].

A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial reported that Ladarixin, an inhibitor of the IL-8 receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2, blocked IL-8 binding to CXCR1/2 receptors, reducing inflammation around β cells and preserving insulin production (C-peptide) for up to a year, with fewer hypoglycemic events [81]. Studies suggest that intensive insulin therapy in T2DM lowers various inflammatory markers (IL-6R, RANTES, ICAM-1) and blocks IL-6 receptor or TNF-α in diabetes and related complications [82, 83]. Targeting the IL-12 family of cytokines shows significant promise for T1DM treatment, acting to reduce harmful inflammation, shield insulin-producing β cells from immune attack, and potentially halt or reverse disease progression by modulating T-cell responses and the overall immune environment within the pancreas. Studies in animal models and early human data suggest blocking IL-12 can protect β cells and shift the immune response, though complexities exist as some IL-12 family members can have dual roles, making precise targeting crucial for effective therapies [84].

Protective cytokines are signaling proteins that regulate immune responses, balancing inflammation to fight pathogens while preventing excessive damage. Omentin, an adipokine from visceral fat, plays a protective role against T2DM and its complications by boosting insulin sensitivity and reducing inflammation, but its levels decrease with obesity and insulin resistance. Omentin has anti-inflammatory, anti-atherogenic, and antioxidant effects, which are crucial for preventing diabetic complications. Low omentin is linked to diabetic complications, while higher levels are associated with better metabolic health, making it a potential biomarker for early detection and a promising therapeutic target for managing diabetic vascular issues [85, 86]. Studies involving human patients have suggested that lower omentin levels in patients with diabetes often signal a higher risk for complications, suggesting it could help clinicians monitor disease progression [87, 88].

Neuregulin-4 (Nrg4) is another protective cytokine. Nrg4 is a protein linked to metabolic health, acting as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for T2DM and related complications; studies show Nrg4 levels are often elevated in diabetics, correlating with poor glucose control, but also that lower levels can signal insulin resistance, while its beneficial effects in animal models suggest it helps improve glucose metabolism and protect against diabetic heart issues. It is produced by fat tissue, helps manage energy balance, and its dysregulation is tied to metabolic disorders, with research exploring it as a predictive marker for diabetes progression and vascular problems [89]. Wang et al. [90], using type I diabetic mice and in vitro studies, reported that Nrg4 attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy by regulating autophagy via the 5’ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway. Kocak et al. [91], in a cross-sectional cohort study including patients with T2DM aged over 18 years, reported that Nrg4 expression is associated with plasma glucose and increases the risk of type 2 DM. Akshay et al. [92] in a prospective study with 100 newly diagnosed T2DM patients and 100 age, sex, and BMI-matched controls reported significantly decreased levels of Nrg4 in diabetics. These findings suggest that increasing Nrg4 levels may be beneficial.

Although there have been strides made in the understanding of cytokine dysregulation in DFUs, applying this knowledge in clinical practice is still very limited. Barriers to clinical translation involve high cost, risk of infection associated with injectable therapies, and uncertainty surrounding the selection of patients who may be most likely to benefit from cytokine therapy. However, treatments with a more personalized medicine framework, such as cytokine profiling, may allow us to better match treatment options to the signature of the individual wound [93]. With regard to cytokine therapy using IFNs, what makes it difficult is trying to separate the beneficial responses from the harmful responses. Future therapies may include using IFN-γ neutralizing antibodies or topical IFN-based therapies that attempt to rebalance local wound immunity without systemic toxicity. Overall, both targeted cytokine strategies and IFN-based therapies represent an overarching theme guiding these immune therapies: to bridge DFUs from chronicity into effective repair, immune imbalance must be corrected in DFUs. With substantial funding in research, more work will be needed to develop adequate and safe therapies from mechanistic understandings of cytokines at the bench research to feasible, reliable, and scalable therapies to reduce the impact of diabetic ulcers globally.

Additionally, patient variability and the lack of predictive biomarkers make it challenging to identify responders, and economic considerations must be addressed to ensure broader accessibility. Treatments within a more personalized medicine framework, such as cytokine profiling, may allow us to better match treatment options to the individual wound’s signature. The challenges in translating clinical research findings into practice are significant and include core issues related to patient variability and cost-effectiveness, along with numerous systemic and practical barriers. Many clinical trials use highly selected patient populations (e.g., younger, healthier patients with few comorbidities), which makes the results difficult to apply to the general patient population encountered in real-world clinical practice. Real-world patients often have multiple health conditions (multimorbidity), making it difficult to follow guidelines developed for single conditions. Clinicians face significant time constraints and heavy workloads, leaving little time to keep up with the vast amount of new research, analyze it, and implement it in practice. Resistance to change, lack of leadership support, and a non-supportive organizational culture can significantly hinder the adoption of new practices. Clinicians face an overload of information and often have difficulty accessing full research articles due to paywalls or a lack of institutional library access [94–98]. Future directions in this field include the development of rapid, clinically feasible cytokine profiling assays, exploration of topical or localized delivery methods, combination therapies with standard-of-care approaches, identification of predictive biomarkers for patient stratification, cost-effectiveness analyses, and rigorous preclinical-to-clinical translation through well-designed trials. Longitudinal and real-world studies will also be essential to evaluate long-term efficacy, recurrence rates, and patient-centered outcomes.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α promote prolonged M1 pathways that are responsible for pro-inflammation while downregulated IL-10 promote M2 macrophages, continues to lead to exacerbation of DFU. Chronic inflammatory states promote insulin resistance and even β-islet pancreatic cell apoptosis in diabetes perpetuate a positive feedback in DM and DFUs. Thus, targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines can lead to improvement in patients with DFUs. Some potential therapeutic strategies include SGLT2 inhibitors, Treg-based interventions, and biologic agents, however, they face challenges in the clinical scenario. Challenges include cost and translating treatment modalities into clinical practice and given how every person has a unique cytokine profile, specific immunotherapies utilizing cytokine profiling can be a major key in treating cytokine imbalances in DFUs. Future research should focus on developing rapid, clinically feasible cytokine profiling assays (predictive biomarkers), patient stratification, exploration of topical or localized delivery methods, and combination therapies with standard-of-care approaches. Large-scale randomized clinical trials should focus on cost-effectiveness, preclinical-to-clinical translation, and long-term efficacy of these agents.

AGEs: advanced glycation end products

Akt: protein kinase B

DFUs: diabetic foot ulcers

DM: diabetes mellitus

ECM: extracellular matrix

FFAs: free fatty acids

GLUT4: glucose transporter 4

IFN: interferon

IL: interleukin

IRS: insulin receptor substrates

JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase

MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase

MMPs: matrix metalloproteinases

NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa beta

NLRP3: NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3

NPWT: negative pressure wound therapy

PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor

ROS: reactive oxygen species

SGLT2: sodium-glucose co-transporter 2

SNPs: single-nucleotide polymorphisms

SOCS: suppressor of cytokine signaling

T1DM: type 1 diabetes

T2DM: type 2 diabetes

TGF: transforming growth factor

TIMP: tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

TLI: toll-like receptor

TNF: tumor necrosis factor

Tregs: regulatory T cells

VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor

AA: Writing—original draft. SM: Writing—original draft. HR: Writing—original draft. OB: Writing—original draft. VR: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

As the corresponding author, I declare that this manuscript is original; that the article does not infringe upon any copyright or other proprietary rights of any third party; and that neither the text nor the figures have been reported or published previously. All the authors have no conflict of interest and have read the journal’s authorship statement.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 917

Download: 50

Times Cited: 0