Affiliation:

Department of Microbiology, Graphic Era (Deemed to be University), Dehradun 248002, Uttarakhand, India

Email: rahulkumar.phdmb@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-1323-2220

Explor Drug Sci. 2025;3:1008135 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2025.1008135

Received: October 08, 2025 Accepted: November 26, 2025 Published: December 09, 2025

Academic Editor: Ayman El-Faham, Dar Al Uloom University, Saudi Arabia, Alexandria University, Egypt

The article belongs to the special issue Bioactive Peptides: Pioneering Innovations in Latin American Research

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are a heterogeneous group of small, naturally occurring molecules that are an integral part of the innate immunity of nearly all life forms. Their amphiphilic nature, cationic character, and small size distinguish AMPs, which have a wide spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses. Their specific ability to selectively destroy microbial membranes, without harming host cells, makes them promising contenders to treat the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which has undermined the effectiveness of traditional antibiotics. The action mechanisms of AMPs are multifaceted, involving both membrane-disruptive mechanisms, like barrel stave pore formation, toroidal pore induction, and carpet-like membrane degradation, and non-membrane targeting mechanisms, like inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis, protein translation, and cell wall biosynthesis. AMPs are structurally diverse, from α-helices and β-sheets to cyclic and unstructured peptides, and are distributed abundantly in nature, being derived from mammals, amphibians, insects, plants, and microorganisms. Apart from antimicrobial activity, AMPs have immunomodulatory and regenerative activities, enabling their use in many therapeutic and industrial applications. These are for the construction of new anti-infective agents, wound healing compounds, medical device coatings to inhibit biofilm growth, natural food preservatives, adjuvants for vaccines, and possible anti-cancer drugs. Although they hold great promise, stability, toxicity, and production scale issues continue to hinder translation to the clinic. This review highlights the structural variability, modes of action, and novel uses of AMPs, with a focus on their status as next-generation therapeutics against multidrug-resistant microbes and for promoting biomedical innovation.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is now a major international public health concern that undermines the efficacy of traditional antibiotics and calls for the invention of novel treatment strategies [1–2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has continuously stressed the possibility of the rapid dissemination of multidrug-resistant organisms, killing millions each year, and compromising contemporary medical treatments like surgery, transplant, and cancer therapy [3]. In this respect, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are frontline candidates for the next generation of drugs. AMPs are a heterogeneous set of small, naturally occurring bioactive molecules that are an integral part of the innate immune defence of almost all living things [4]. Their wide-ranging activity against bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites, and their low potential for resistance emergence, render them potential substitutes or adjuncts to conventional antibiotics as antiviral agents against infectious diseases. Being generally made up of fewer than 100 amino acid residues, AMPs are also characterized by unique physicochemical features, including amphiphilicity and a net positive charge [5]. These attributes facilitate selective interaction with the negative membrane of microorganisms and spare mammalian cells, which tend to have less negatively charged outer membranes [6]. The amphiphilic character of AMPs, including both hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions, also makes them able to cross and disrupt lipid bilayers, leading to the quick destruction of microbes [7]. In contrast to conventional antibiotics, which typically act on discrete enzymes or pathways, AMPs utilize multidimensional modes of action that make microbial resistance more difficult to develop. Such mechanisms involve direct membrane-rupturing approaches, including pore formation via barrel stave, toroidal pore, or carpet-like models, and non-membrane targeting mechanisms, such as interference with nucleic acid synthesis, protein translation, and cell wall biogenesis [8]. The structural and functional diversity of AMPs is striking, an expression of their evolutionary function as universal host defence molecules. They can be grouped into a number of different structural types, such as α-helical peptides like magainins and cathelicidin LL-37, β-sheet peptides like defensins, extended or unstructured peptides that are rich in residues like proline or tryptophan, like indolicidin, and cyclic peptides like theta defensins that have increased stability [9]. Their origins are similarly varied, covering all kingdoms of life. Cathelicidins and defensins are AMP families in mammals, amphibians synthesize magainins from secretions in their skin, insects synthesize cecropins and attacins, plants synthesize thionins and defensins, and bacteria synthesize bacteriocins like nisin [10]. Such a broad natural occurrence reinforces the evolutionary conservation and importance of AMPs to innate immunity. Apart from their antimicrobial activities, AMPs are very multifunctional, which makes them useful for a wide range of biomedical and industrial uses. In the hospital, AMPs are also being engineered as new antimicrobial drugs that can target multidrug-resistant bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [11].

AMPs are under study for their wound healing potential since some of the peptides, including LL-37, exhibit not just antimicrobial functions but also stimulate immune reactions, angiogenesis, and epithelial restoration [12]. AMPs can also be incorporated into coatings of medical devices and implants to avoid biofilm-related infections. In the food sector, bacteriocins such as nisin have been successfully used as natural preservatives, promoting food safety with less dependency on artificial chemicals [13]. In addition, the immunomodulatory nature of AMPs makes them potential candidates as vaccine adjuvants, enhancing host immune response to vaccination. Other studies have also shown potential for AMPs to act as anti-cancer compounds since some of the peptides are capable of selectively destroying cancer cells while sparing normal cells through variations in cellular membrane composition [14]. Their clinical use is the ward by various challenges such as susceptibility to proteolytic degradation, compromised stability in physiological conditions, cytotoxicity at higher concentrations, and the high cost of peptide synthesis [15]. Nevertheless, extraordinary progress is being achieved to overcome these challenges. Advances in peptide engineering, nanotechnology-based delivery systems, recombinant expression technologies, and computational design are improving AMP stability, specificity, and scalability. These advancements are expected to enhance the pharmacological activity of AMPs and shorten their timeline for their entry into mainstream clinical and industrial applications [16]. This review aims to give a complete overview of AMPs, with special emphasis on their structural classification, mechanisms of action, sources, and therapeutic uses. It will highlight the unique characteristics that make AMPs active contenders in the fight against AMR and elucidate their new functions beyond infectious disease prevention, such as wound healing, cancer treatment, and vaccine production. In addition, the review will cover the major hindrances and challenges hindering AMP commercialization and present current approaches aimed at overcoming these problems. Through connecting core insights with translational views, this review emphasizes the importance of AMPs as multiple alternative bioactive compounds that can transform world health and biotechnology in the next few decades (Table 1).

Classification of antimicrobial peptides.

| Class | Peptide name | Source organisms | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Helical peptides | Magainins, LL-37, cecropins | Amphibians (frog skin), humans, insects | Unstructured in solution; adopts α-helical conformation upon membrane contact; amphipathic; disrupts membranes via pore formation (barrel stave/toroidal models). | [17] |

| β-Sheet peptides | Defensins (α-, β-defensins), tachyplesins | Mammals, plants, and horseshoe crabs | Stabilized by disulfide bonds; rigid structures; strong membrane binding; pore-forming activity. | [18] |

| Extended/unstructured peptides | Indolicidin, Bac5, Bac7 | Cattle, insects | Rich in specific amino acids (proline, tryptophan, glycine); flexible structure; can penetrate cells; target DNA, RNA, or ribosomes. | [19] |

| Cyclic peptides | Theta-defensins, Lantibiotics (nisin) | Primates (rare), bacteria | Backbone/head to tail cyclization; high stability against proteolysis; potent against Gram-positive bacteria; often inhibit cell wall biosynthesis. | [20] |

| Lipopeptides | Daptomycin, polymyxin B, surfactin | Bacteria (e.g., Streptomyces, Bacillus) | Peptides conjugated with lipid tail; insert into bacterial membranes; disrupt integrity; clinically used as last resort antibiotics. | [21] |

| Mammalian peptides | Cathelicidins (LL-37), defensins | Humans, cattle, other mammals | Crucial in innate immunity; immunomodulatory roles; involved in wound healing and inflammation regulation. | [22] |

| Amphibian peptides | Magainins, dermaseptins, esculentins | Frogs, toads | Rich source of diverse antimicrobial peptides (AMPs); mostly α-helical; highly potent against bacteria and fungi. | [23] |

| Insect peptides | Cecropins, attacins, defensins, melittin | Moths, flies, bees | Defense peptides secreted in hemolymph; active against Gram-negative bacteria and fungi; some (melittin) are cytolytic. | [24] |

| Plant peptides | Thionins, plant defensins, cyclotides | Wheat, barley, medicinal plants | Contribute to pathogen resistance; many are cysteine-rich; cyclic variants are highly stable. | [25] |

| Microbial peptides (bacteriocins) | Nisin, subtilin, pediocin | Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Lactococcus, Bacillus) | Ribosomally synthesized; potent, narrow or broad-spectrum antibacterial activity; widely used in food preservation. | [26] |

| Membrane-targeting | Cecropins, magainins, LL-37 | Insects, amphibians, humans | Disrupt membranes by pore formation (barrel stave, toroidal, carpet models); rapid killing. | [27] |

| Non-membrane-targeting | Indolicidin, buforin II, Bac7 | Cattle, frogs, insects | Inhibit nucleic acid synthesis, protein synthesis, or cell wall synthesis; intracellular activity without major membrane disruption. | [28] |

| Antibacterial peptides | Defensins, cathelicidins, nisin | Humans, amphibians, bacteria | Broad-spectrum antibacterial activity; kills Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. | [29] |

| Antifungal peptides | Histatins, dermaseptins | Humans (saliva), frogs | Disrupt fungal membranes; inhibit fungal enzymes and adhesion. | [30] |

| Antiviral peptides | LL-37, defensins, melittin | Humans, insects | Block viral entry, fusion, or replication; potential against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), influenza, and coronaviruses. | [31] |

| Antiparasitic peptides | Dermaseptins, cecropins | Frogs, insects | Active against protozoan parasites (e.g., Leishmania, Plasmodium). | [32, 33] |

| ACPs | Magainin II, lactoferricin, melittin | Frogs, humans, bees | Selectively disrupt cancer cell membranes due to higher negative charge; induce apoptosis. | [34] |

ACPs: anticancer peptides.

AMPs act mainly by direct interactions with microbial cell membranes. In most cases, attack-specific biochemical targets, AMPs take advantage of the natural structural distinctions between microbial and host cell membranes [35]. The majority of AMPs are cationic and amphipathic and thus have the capacity to associate electrostatically with negatively charged microbial surface molecules, including lipopolysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria and teichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria. When bound, AMPs insert into the lipid bilayer, leading to physical disruption that creates leakage of cytoplasmic contents and cell death in minutes [36]. Multiple models have been proposed to explain this mechanism. The barrel stave model assumes that peptides stack perpendicularly to create transmembrane pores similar to barrel staves. The toroidal pore model infers that peptides create bilayer curvature, leading to pore lining by peptides and lipid head groups [37]. In the carpet model, peptides blanket the membrane surface as a carpet until a critical concentration is attained, resulting in micellization and membrane disruption [38]. These mechanisms are rapid, thus preventing the emergence of microbial resistance. In general, the membrane targeting strategy confers potent, broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity to AMPs, highlighting their value as alternatives to traditional antibiotics [39]. Unlike conventional antibiotics, which normally target specific biochemical pathways such as protein synthesis or cell wall formation, AMPs exert a multi-mechanistic mode of action that makes the development of resistance by pathogens. This is more effective against multi-drug resistant (MDR) strains, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The Gram-negative bacteria are more effectively targeted by AMPs due to their outer membrane disruption ability, leading to the destabilization of the lipid bilayer; this is not common for a wide range of conventional antibiotics. The comparative studies further suggest that beyond an induction of more rapid bactericidal effects, AMPs exhibit immunomodulatory and anti-biofilm activity, which further distinguishes them from conventional antibiotics.

Barrel stave model is an established mechanism explaining how AMPs lyse microbial membranes. The model proposes that the peptides, which mostly comprise amphipathic α-helices, first interact with the microbial cell membrane through charge interactions between their basic amino acid residues and the acidic constituents of the pathogenic membrane [40]. The peptides, after binding, experience conformational changes that facilitate their perpendicular integration into the lipid bilayer. The hydrophobic faces of the peptides pair with the lipid tails of the membrane, while the hydrophilic faces face inward to associate with each other and create a pore [41]. The structure of this arrangement is that of staves of a barrel that gives rise to a cylindrical hole across the membrane. The formation of this pore leads to the uncontrolled loss of ions, metabolites, and crucial cytoplasmic factors, ultimately causing lysis and death of the cells [42]. The unique characteristic of this model is that the pore consists only of peptides with limited lipid molecules participating to line the tube. Some of the AMPs that act through this mechanism of action are alamethicin, a fungal peptide that has been widely characterized to have pore-forming activity [43]. The model is very efficient because the formation of stable, peptide-based pores quickly breaches microbial membrane integrity, thus minimizing the chance of pathogens developing resistance [44]. The accuracy of this mechanism in breaching microbial membranes with strict selectivity over mammalian cells shows that its exploitation can lead to the discovery of new-generation antimicrobial agents [45].

The toroidal pore model is a broadly accepted mechanism of action for AMPs that permeabilize microbial membranes. In this process, amphipathic and cationic peptides first bind to the negatively charged microbial membrane surface by electrostatic forces, targeting components like lipopolysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria or teichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria [45]. After reaching a threshold local concentration, these peptides self-associate on the membrane surface and cause curvature in the lipid bilayer. In contrast to the barrel stave model, where peptide molecules only line pores, both the inserted peptide molecules as well as the lipid head groups of the membrane itself cause a continuous curvature of the bilayer into a doughnut-shaped channel [46], line toroidal pores. Such cooperative membrane deformation allows the passage of ions, metabolites, and water molecules, eventually leading to a loss of membrane potential, leakage of cytoplasm, and cell death in microbes. The dynamic character of toroidal pore formation enables AMPs to rapidly adapt to heterogeneous lipid composition as an adaptation mechanism by making it difficult for cells to evolve effective resistance mechanisms [47]. Magainins, as well as melittin, are typical examples that use their action by this mechanism, showing broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, and even enveloped viruses [48]. The toroidal pore model highlights the complex interplay between peptide structure and membrane biophysics, placing a particular emphasis on amphipathicity as a dominant parameter as well as peptide concentration for pore formation [49]. Knowledge on this mechanism can provide clues toward the rational design of novel synthetic AMPs as well as peptide therapeutics that will exhibit enhanced specificity as well as enhanced antipathy against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

The carpet model outlines a characteristic mechanism by which AMPs disrupt microbial membranes without generating distinct transmembrane pores. In this model, amphipathic and cationic peptides first bind to the negatively charged microbial membrane surface by electrostatic forces, targeting molecules like Gram-negative bacteria’s lipopolysaccharides or Gram-positive bacteria’s teichoic acids. After binding, the peptides orient parallel to the membrane surface and cover it widely in a carpet-like manner. This accumulation on the surface increases peptide concentration locally and disrupts the lipid bilayer by collective effects [50]. Unlike pore-forming models like barrel stave or toroidal models, the carpet model does not require perpendicular peptide insertion into the membrane but instead operates in a detergent-like action that causes a generalized lipid packing disruption, leading to micellization or fragmentation of the membrane. The microbial membrane’s integrity thus becomes faulty, leading to uncontrolled leakage of ions, metabolites, and cytoplasmic content, leading rapidly to cell death [51]. The mechanism is against a broad range of bacteria since it utilizes membrane charge as well as lipid composition, as opposed to specific molecular targets. Representative examples of AMPs that utilize the carpet mechanism range from the traditional AMPs, such as cecropins, as well as dermaseptins, to some synthetic α-helical peptides [52]. The carpet model highlights the importance of amphipathicity of the peptide as well as surface density, as well as electrostatic interaction in antimicrobial action, and holds relevant lessons toward designing therapeutics based on peptides that can target efficiently drug-resistant pathogens with minimal host cell cytotoxicity [53, 54].

Besides direct disruption of microbial membranes, many AMPs employ non-membrane targeting modes of action for exerting their antimicrobial activity [55]. In contrast to membrane targeting AMPs, these AMPs can cross the lipid bilayer without inducing pronounced structural alterations, thus gaining access to intracellular targets. Once intracellularly localized, they can interfere with vital processes required for microbial survival and cell division. A typical mechanism of action involves the blockage of nucleic acid synthesis by peptides such as indolicidin or buforin II binding to DNA or RNA with the attendant prevention of transcription, replication, and other nucleic acid-dependent activities [56]. A further important target is protein synthesis; examples here include proline-enriched AMPs such as Bac7 that interact with ribosomal machinery, with translation being blocked and thus preventing cellular growth [57]. AMPs also inhibit cell wall biosynthesis as a mechanism; examples here include nisin, which binds lipid II, which is an important precursor during peptidoglycan assembly, such that eventually cell wall integrity can be compromised. Non-membrane targeting AMPs provide a multi-faceted approach towards microbial control by limiting the chances of resistance development as various intracellular pathways can be blocked concurrently [58]. The intracellular mechanism of action, coupled with selective targeting towards microbial cells, confers enhanced therapeutics on AMPs as next-generation antimicrobial molecules capable of combating multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Among the diverse modes of action employed by AMPs, the suppression of nucleic acid synthesis represents a central non-membrane targeting mechanism. Through this mechanism, such molecules can interfere with desirable intracellular processes without inducing massive membrane damage in microbes. Some cationic and amphipathic AMPs can insert across the microbial lipid bilayer by taking advantage of electrostatic forces as well as peptide conformational plasticity to reach the cytoplasm [59]. Once internalized, these molecules directly engage nucleic acids or nucleic acid-linked enzymes, thus blocking replication, transcription, and other vital processes required by microbial cells for survival. Indolicidin, a 13-residue tryptophan and proline-enriched AMP, for instance, binds strongly with bacterial DNA by inducing non-covalent forces that distort the double helix structure as well as inhibit replication and transcription [60]. In a similar manner, buforin II from histone H2A can enter microbial cells as well as bind with DNA as well as RNA, such that gene expression is blocked as enzymatic activities valuable for nucleic acid metabolism are inhibited. These engagements are frequently sequence nonspecific yet depend on structural complementariness as well as electrostatic attraction between the positive charge residues on the peptide as well as the negative charge phosphate backbone on nucleic acids [61]. In targeting intracellular nucleic acids, AMPs exhibit powerful antimicrobial action against a diverse range of pathogens that range including Gram-positive as well as Gram-negative bacteria as well as fungi as well and some viruses. This action has a distinct advantage in fighting multidrug-resistant organisms since this action avoids traditional targets such as cell wall synthesis or protein translation that often develop resistance mutations as targets for action. The molecular understanding of nucleic acid suppression by AMPs can thus provide useful guidelines in designing synthetic peptides or peptide mimetics that are more specific as well as more thermostable, such that they can emerge as next-generation antimicrobial drugs with wider prospects [62].

Proline-rich AMPs (PrAMPs) are a distinct group of non-membrane targeting AMPs that primarily act by blocking protein synthesis [63]. In contrast to membrane-disruptive peptides, PrAMPs are able to cross the microbial membrane without bringing about extensive structural destruction, thereby guaranteeing proper access to intracellular targets. On entering the cytoplasm, these peptides target ribosomal components and translation machinery attached to them, thereby inhibiting elongation of nascent polypeptide chains and effectively stopping protein synthesis. Bac7, a well-characterized PrAMP present in bovine neutrophils, is an excellent example of this action, where it targets the 70S bacterial ribosome, occupies the exit tunnel, and prevents transfer RNAs from their correct positioning, which is crucial for the translation process [64]. This selective inhibition not only inhibits the development of the microbe but also blocks the development of essential enzymes and structural proteins necessary for cellular survival. The protein synthesis inhibitory mechanism is particularly useful in combating drug-resistant bacteria because it bypasses the common targets, such as cell wall biosynthesis or DNA replication, which are frequently the focus of resistance mutations. Furthermore, PrAMPs are highly specific to bacterial ribosomes over eukaryotic ribosomes, making them decrease potential cytotoxicity towards host cells [65]. Acting against a crucial intracellular mechanism very conserved within bacteria, PrAMPs are a strong and selective antimicrobial strategy. Understanding this mechanism is of useful contribution to the development of novel synthetic peptides or analogs capable of selectively inhibiting microbial protein synthesis, thereby promoting next-generation drug development against drug-resistant pathogens.

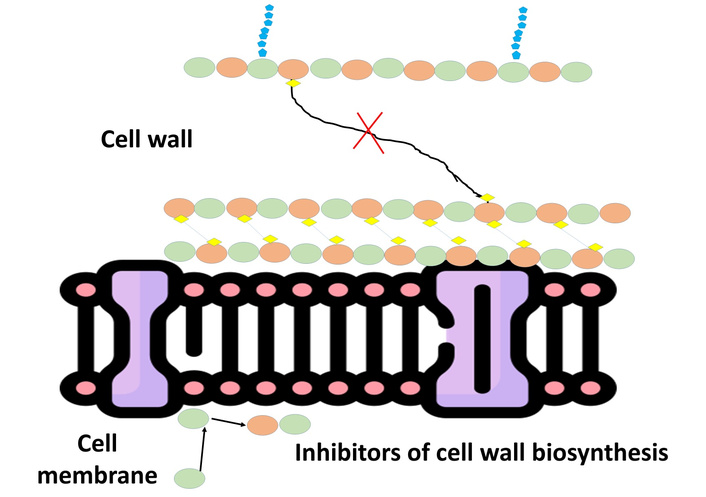

Besides interfering with membranes and intracellular processes, some AMPs aim mainly at bacterial cell wall biosynthesis as a mode of antimicrobial action. The peptidoglycan-based bacterial cell wall contributes structural integrity and osmotic stress protection, making it an important target for antimicrobial compounds. Peptides like nisin, a well-documented lantibiotic produced by Lactococcus lactis, inhibit cell wall synthesis through the specific binding of lipid II, a critical precursor during peptidoglycan biosynthesis [66]. Lipid II acts as a carrier molecule to ferry peptidoglycan subunits through the cytoplasmic membrane for incorporation into the expanding cell wall [67]. Sequestering lipid II, nisin prevents the polymerization and cross-linking of peptidoglycan strands effectively, resulting in a compromised cell wall structure. This disruption not only threatens cell wall integrity but also enhances sensitivity to osmotic pressure, leading to cell lysis and cell death. Along with inhibiting synthesis, nisin and related peptides can also cause pore formation in the membrane at the location of lipid II accumulation, thus integrating cell wall inhibition with membrane targeting activities [68]. This bimodal mechanism increases antimicrobial activity and decreases resistance potential. Cell wall biosynthesis targeting peptides are highly active against Gram-positive bacteria because of the availability of lipid II within the dense peptidoglycan layer. Knowledge of molecular interactions between AMPs and cell wall precursors provides important insights for the design of novel therapeutics based on peptides and antibiotic analogs with improved stability, selectivity, and clinical relevance against multidrug-resistant pathogens (Figure 1).

Mechanism of action of inhibitors of cell wall biosynthesis. That illustrates how antimicrobial agents disrupt peptidoglycan synthesis, blocking the linkage between cell wall precursors, weakening the cell wall integrity, ultimately causing microbial cell lysis.

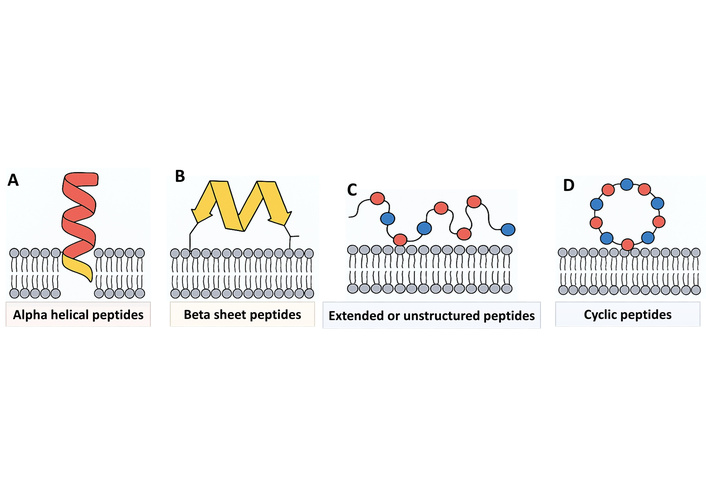

Alpha-helical AMPs are a well-studied group of AMPs characterized by the ability to form an α-helical structure when interacting with the microbial membrane [69]. When dissolved, they tend to be unstructured or form a random coil structure. However, on interacting with the lipid bilayer of microbial cells, their amphipathic character enables them to fold into an α-helix, and hydrophobic residues are oriented towards the lipid interior of the membrane while hydrophilic or cationic residues face the aqueous phase [70]. This amphipathic α-helical structure is critical for the interaction with the membrane by enabling the peptide to insert into and destabilize the microbial membrane efficiently. The major mode of action of α-helical peptides is membrane targeting, but others have intracellular activity as well. After binding to the membrane, peptides like magainins (from frog skin) and human cathelicidin LL-37 are deposited on the surface of the membrane [71]. Dependent on the membrane composition and peptide concentration, they are able to disrupt the membrane through one of a number of models: barrel stave pore formation, in which peptides insert perpendicularly to form transmembrane pores; toroidal pores, in which peptides and lipid head groups line the pore; or the carpet model, in which peptides coat the surface of the membrane and cause disintegration in a detergent like process. This leads to leakage of cytoplasmic contents, loss of membrane potential, and quick microbial cell death. Magainins, purified from Xenopus laevis skin, operate through toroidal pore formation, demonstrating broad-spectrum activity against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, fungi, and certain protozoa. LL-37, a human cathelicidin, not only forms α-helices to disrupt membranes but also has immunomodulatory activity and acts for wound healing [72]. The structural flexibility and broad-spectrum nature of α-helical AMPs make them very promising therapeutic candidates, especially against multidrug-resistant organisms (Figure 2).

Structural classes of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and their interactions with microbial membranes. The four major structural classes of AMPs: (A) α-helical peptides, which assume an amphipathic helical conformation upon interaction with lipid bilayers; (B) β-sheet peptides, whose rigidity is provided by disulfide bonds that stabilize a β-structure; (C) extended or unstructured peptides, which lack a defined secondary structure and are thus able to traverse the membrane and/or target intracellular molecules; and (D) cyclic peptides, containing covalent cyclization that confers stability, protease resistance, and often broad spectrum activity. These diverse structures provide the basis for different modes of membrane interaction and antimicrobial activity.

Beta-sheet AMPs are a structurally distinct class characterized by the presence of intramolecular disulfide bridges that stabilize their β-sheet structure. Unlike α-helical peptides, β-sheet AMPs have a preformed, rigid secondary structure even in solution, which accounts for their stability and resistance to proteolytic digestion [73]. The amphipathic character of β-sheet peptides allows for selective interaction with microbial membranes: positively charged residues interact with negatively charged elements of bacterial membranes, e.g., lipopolysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria or teichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria, and hydrophobic residues insert into the lipid bilayer. The major mode of action of β-sheet peptides is membrane targeting. After adhering to the microbial surface, these peptides may cause membrane permeabilization and pore formation, leading to the leakage of ions and vital cytoplasmic materials, ultimately causing cell death [74]. Certain β-sheet AMPs, including defensins, are also able to aggregate to create multimeric complexes that increase membrane disruption. Some β-sheet peptides are also immunomodulatory, inducing chemotaxis, cytokine release, and other host defence mechanisms. Defensins, in humans, mammals, and plants, are traditional β-sheet AMPs that are supported by three to four disulfide bridges [75]. Defensins have broad-spectrum antimicrobial action against bacteria, fungi, and certain viruses by causing membrane permeabilization. Their structural stability and multifunctionality make β-sheet peptides very potent as innate immune effectors and potential therapeutic agents, especially against multidrug-resistant pathogens (Figure 2) [76].

Long or disordered AMPs are a unique class of peptides that lack a stable secondary structure in solution. Unlike α-helical or β-sheet peptides, these molecules do not adopt a stable form until they engage with microbial membranes or intracellular targets. Their inherent flexibility facilitates them to conform to different environments and bind well to various molecular targets. Long peptides are often highly enriched in particular amino acids like proline, glycine, tryptophan, or arginine, which provide distinctive chemical characteristics [77]. Proline and glycine provide structural adaptability, and tryptophan provides favorable interactions with lipid membranes via aromatic stacking and hydrophobic forces. The mode of action of unstructured or extended peptides is intricate. Most of these peptides are non-membrane targeting in their activity through translocation through microbial membranes with minimal disruption and then interfering with essential intracellular processes. For example, indolicidin, a 13-residue peptide from bovine neutrophils, has the ability to penetrate bacterial membranes and interact directly with DNA and RNA to inhibit nucleic acid synthesis and transcription, and replication [78]. Besides intracellular delivery, some extended peptides also possess membrane-disruptive activity at higher doses, disrupting the lipid bilayer in a carpet fashion. The flexibility of extended peptides enables them to deliver a wide range of microorganisms, such as Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, and viruses. They are small in size, rich in positively charged residues, and have flexible conformations, which increase cell penetration and binding specificity. This dual mechanism, entailing intracellular targeting coupled with possible membrane disruption, makes extended or unstructured AMPs extremely effective against multidrug-resistant pathogens [79]. Elucidation of their structure-function relationships is important in designing synthetic analogues with improved stability, potency, and therapeutic utility. Indolicidin is a case in point, which exhibits robust antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities, as well as a model for the rational development of new peptide-based therapeutics (Figure 2) [80].

Cyclic AMPs are a unique class of peptides characterized by covalent cyclization, either through head-to-tail cyclization or through side chain linkages. This structural restriction imparts greater stability, proteolytic resistance, and enhanced bioavailability compared to linear peptides. The cyclic structure also allows the preservation of a structured amphipathic presentation, which is vital for selective interaction with microbial membranes and intracellular targets [81]. Most cyclic peptides are rich in hydrophobic and cationic residues, facilitating strong electrostatic attraction against negatively charged bacterial membranes with minimal toxicity against host cells. The mode of action of cyclic peptides is complex. They can lyse microbial membranes by pore formation or membrane disruption, similar to α-helical and β-sheet peptides. Additionally, some cyclic peptides, like lantibiotics, inhibit bacterial elements, such as lipid II, a vital precursor of peptidoglycan assembly, consequently slowing cell wall development [82]. Their stable conformation also allows them to penetrate microbial cells for intracellular target interference, such as nucleic acids and enzymes, thus improving antimicrobial activity. Theta defensins in some primates are a good example of cyclic AMPs. They show wide-spectrum action against bacteria, fungi, and enveloped viruses and are highly resistant to thermal and proteolytic degradation [83]. The structural stability, amphipathic nature, and multifunctional activity make cyclic peptides a prime choice for the discovery of next-generation antimicrobial therapeutics. Their peculiarity promises high potential in the fight against multidrug-resistant pathogens and the construction of new peptide-derived drugs that are more potent and stable (Figure 2).

AMP sources are extremely different and include fungi, insects, bacteria, plants, amphibians, and mammals. They play a crucial role in innate immunity. Their natural sources, modern biotechnological, and synthetic production techniques have significantly extended the possibility of obtaining AMPs for therapeutic application. Recombinant DNA technology, solid-phase peptide synthesis, and microbial fermentation are the most common methods for AMP production on an industrial scale, confirming high yield and purity. In direct comparison to conventional antibiotics, the production of AMPs has several advantages: simpler biosynthetic pathways often mean a lower environmental impact, and peptides can be optimized genetically or chemically in ways that reduce cytotoxicity while improving consistency. Cell-free expression systems and bioengineering techniques have moreover enabled the rapid generation of novel AMPs with tailored antimicrobial spectra and physicochemical properties. Taken together, these advances have improved the sustainability and flexibility of the AMP production process while opening perspectives for large-scale industrial production. Thus, feasibility and versatility in the AMP production processes represent promising alternatives to traditional drug development, enabling the solving of economic and resistance-related challenges in modern antimicrobial therapy.

Mammalian AMPs, including cathelicidins and defensins, are part of innate immunity, providing immediate and broad-spectrum protection against microbial pathogens. Cathelicidins, including human LL-37, and defensins (α- and β-defensins) are secreted on epithelial surfaces, within neutrophils, and other immune cells and represent the first line of defence against bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites [84]. These peptides are cationic and amphipathic in nature to a large extent, which allows them to selectively engage with the negatively charged microbial membranes without harming the host cells, whose membranes are mostly charge neutral. The major action mechanism of cathelicidins and defensins is membrane targeting. When exposed to microbial membranes, these peptides are able to adopt amphipathic conformations that allow them to insert into the lipid bilayer [85]. They destabilize the membrane through the mechanisms of pore formation (barrel-stave and toroidal pore models) or surface accumulation that causes disintegration of the membrane (carpet model), leading to leakage of the cytoplasmic contents, loss of membrane potential, and quick microbial cell death. In addition to direct membrane disruption, these peptides have non-membrane targeting mechanisms. They can import inside the microbial cells and inhibit intracellular functions such as nucleic acid and protein synthesis [86]. Some defensins also bind lipid II, a pivotal precursor in the synthesis of bacterial cell walls, inhibiting cell wall formation and aiding in microbial killing. Besides their antimicrobial action, mammalian AMPs are involved in modulating host immune responses. LL-37 and defensins have the ability to recruit immune cells, activate cytokine production, and improve wound healing, thus bridging innate immunity to adaptive responses [87]. The synergy of membrane disruption, intracellular targeting, and immunomodulatory activity makes cathelicidins and defensins extremely potent against multidrug-resistant pathogens and a solid platform for the design of new therapeutic approaches. Their structural flexibility, broad-spectrum activity, and immune-regulating functions mark them as promising next-generation antimicrobials (Table 2).

Mammalian antimicrobial peptides.

| Peptide type | Source | Structure | Mechanism of action | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cathelicidins | Humans, other mammals | α-Helical (unstructured in solution, helical upon membrane interaction) | Membrane disruption via pore formation; immunomodulation; chemoattraction of immune cells | LL-37 (human), CRAMP (mouse) | [88] |

| α-Defensins | Neutrophils, paneth cells | β-Sheet stabilized by disulfide bonds | Membrane permeabilization; inhibition of bacterial and viral entry | HNP-1, HNP-2 (humans) | [89] |

| β-Defensins | Epithelial cells | β-Sheet stabilized by disulfide bonds | Membrane disruption; immunomodulatory effects; chemoattraction of immune cells | hBD-1, hBD-2, hBD-3 | [90] |

| θ-Defensins | Some primates (e.g., rhesus macaque) | Cyclic β-sheet peptides | Membrane disruption; inhibition of viral replication; high stability | RTD-1, RTD-2 | [91] |

| Lactoferricin | Milk, neutrophils | Amphipathic α-helix | Membrane permeabilization; iron sequestration; anti-inflammatory effects | Human lactoferricin (hLFcin) | [92] |

| Protegrins | Pigs (porcine) | β-Hairpin stabilized by disulfide bonds | Membrane disruption; bacterial lysis | PG-1, PG-2 | [93] |

| Hepcidin | Liver | Cysteine-rich, β-sheet | Binds iron and disrupts bacterial iron homeostasis; membrane targeting | Human hepcidin | [94] |

Amphibians, especially frogs, produce a wide variety of AMPs from their skin secretions as an important defense mechanism to combat pathogens in wet, microbe-laden environments. Among these, magainins from Xenopus laevis are one of the best-characterized examples. Magainins are amphipathic, cationic peptides that are known to adopt an α-helical conformation when they interact with microbial membranes [95]. Their amphipathic character allows for selective action against negatively charged microbial membranes, for example, bacterial lipopolysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria or teichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria, with relative sparing of mammalian cells because of differences in membrane structure. Membrane targeting is the major mechanism of action of magainins. On binding to the microbial surface, magainins insert into the lipid bilayer and induce toroidal pore formation, where the peptides aggregate and force the membrane to curve inward, creating pores lined by both the peptides and lipid head groups [96]. This leads to leakage of ions, metabolites, and cytoplasmic contents, resulting in swift microbial cell killing. In other cases, at elevated concentrations, magainins are capable of disorganizing membranes through a carpet-like mechanism, in which the surface becomes coated and destabilized in a detergent-like fashion. In addition to direct membrane disruption, magainins can also display other immunomodulatory effects, including augmenting host immune responses and facilitating wound healing [97]. Their wide range of activity against bacteria, fungi, and some viruses, as well as low resistance-inducing capacity, makes magainins very useful templates for the design of synthetic peptides. Magainin structural versatility, membrane selectivity, and multifunctional activity highlight their clinical potential as second-generation antimicrobial drugs, especially against drug-resistant pathogens (Table 3).

Amphibian antimicrobial peptides.

| Peptide type | Source | Structure | Mechanism of action | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magainins | Frog skin (Xenopus laevis) | α-Helical, amphipathic | Membrane disruption via pore formation (barrel-stave, toroidal, or carpet models) | Magainin-1, magainin-2 | [98] |

| Brevinins | Frog skin (Rana spp.) | α-Helical, amphipathic | Membrane permeabilization; induction of cell lysis | Brevinin-1, brevinin-2 | [99] |

| Dermaseptins | Frog skin (Phyllomedusa spp.) | α-Helical, cationic | Membrane disruption; selective antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, and protozoa | Dermaseptin B2, dermaseptin S1 | [100] |

| Temporins | Frog skin (Rana temporaria) | Short α-helical peptides | Disruption of microbial membranes; broad-spectrum activity | Temporin A, temporin L | [101] |

| Esculentins | Frog skin (Rana esculenta) | α-Helical, amphipathic | Membrane permeabilization; inhibition of bacterial growth | Esculentin-1, esculentin-2 | [102] |

| Ranatuerins | Frog skin (Rana tigrina) | α-Helical, amphipathic | Membrane disruption; anti-bacterial and anti-fungal activity | Ranatuerin-1, ranatuerin-2 | [103] |

Insects generally exploit AMPs as a main defence strategy against microbial infection, due to the lack of an adaptive immune system [104]. Among the most well-studied insect-derived AMPs are cecropins and attacins, which possess broad-spectrum activity against bacteria and fungi. Cecropins are short, cationic, amphipathic α-helical peptides that act on bacterial membranes, while attacins are longer, glycine-rich peptides that mainly target bacterial outer membrane proteins [105]. The mode of action of cecropins is chiefly membrane targeting. The electrostatic interactions of cecropins with the anionic microbial membranes lead to the adoption of α-helical structures following contact. They embed in the lipid bilayer and cause the creation of transmembrane pores that disrupt membrane integrity. This leads to ion leakage and cytoplasmic contents leakage, depolarization, and eventually microbial cell death [106]. Depending on the concentration of peptide and the composition of the membrane, cecropins might also utilize a carpet mechanism, binding to the surface and destabilizing the lipid bilayer in detergent fashion. Attacins interfere with bacterial outer membrane protein synthesis, however. Through their binding to lipopolysaccharides and prevention of the synthesis of certain outer membrane proteins, attacins degrade the structure and permeability of the bacterial envelope, inhibiting growth and increasing sensitivity to host defence mechanisms [107]. Aside from direct antimicrobial action, insect AMPs have the ability to modulate the host immune system by initiating hemocyte recruitment and facilitating phagocytosis. The synergy between quick membrane disintegration (cecropins) and the disruption of crucial bacterial protein synthesis (attacins) makes insect AMPs very effective at regulating microbial numbers [108]. Structural variety, specificity, and low resistance-potentiating propensity all highlight their potential to serve as templates for the design of new antimicrobial drugs against multidrug-resistant pathogens (Table 4).

Insect antimicrobial peptides.

| Peptide type | Source | Structure | Mechanism of action | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cecropins | Silk moth (Hyalophora cecropia) | α-Helical, amphipathic | Membrane disruption via pore formation; broad-spectrum antibacterial activity | Cecropin A, cecropin B | [109] |

| Defensins | Insect hemolymph (e.g., Drosophila, beetles) | β-Sheet stabilized by disulfide bonds | Membrane permeabilization; inhibition of bacterial and fungal growth | Defensin A, defensin B | [110] |

| Attacins | Silk moth (Hyalophora cecropia) | Glycine-rich proteins | Inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis; effective mainly against Gram-negative bacteria | Attacin A, attacin B | [111] |

| Diptericins | Flies (Drosophila spp.) | Glycine-rich peptides | Inhibit bacterial growth by targeting outer membrane proteins | Diptericin A, diptericin B | [112] |

| Drosomycin | Drosophila melanogaster | Cysteine-rich, β-sheet peptide | Antifungal activity; disrupts fungal cell membranes | Drosomycin | [113] |

| Defensin-like peptides | Honeybee (Apis mellifera) | β-Sheet stabilized by disulfide bonds | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity; membrane permeabilization | Abaecin, apidaecin | [114] |

Plants produce a wide variety of AMPs as a part of their innate immunity to fight microbial pathogens. Thionins and plant defensins are noteworthy examples that protect plant tissues against bacterial, fungal, and viral infections. They are typically small in size, cationic, and cysteine-rich, which allows them to form a stable tertiary structure and selectively bind to microbial cell membranes. Thionins are amphipathic peptides that act primarily by targeting membranes. They electrostatically bind to negatively charged phospholipids in microbial membranes, inserting their hydrophobic ends into the lipid bilayer [115]. This binding disrupts membrane integrity by causing pore formation, leakage of cytoplasmic material, and eventually cell death. The quick mode of action of thionins makes them very potent against a wide range of microorganisms, especially fungi and Gram-positive bacteria. On the other hand, plant defensins have a dual mode of action. Aside from disintegrating microbial membranes like thionins, they also have a specific target within intracellular elements [116]. For example, some plant defensins suppress fungal cell wall biosynthesis by inhibiting glucosylceramide or other essential membrane-associated proteins, interrupting cell growth and division. Plant defensins can also induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation inside microbial cells to further augment antimicrobial activity. Plant AMPs are stabilized by disulfide bridges, which safeguard them against proteolytic degradation and stress conditions [117]. Their structural stability, broad-spectrum action, and multiplicity of mechanisms make plant AMPs extremely useful for biotechnological purposes, such as the engineering of resistant crops and antimicrobial agents of natural origin. The synergy between membrane disruption, intracellular disruption, and ROS induction highlights the evolutionary value and therapeutic opportunity of peptides from plants in the fight against pathogenic microorganisms (Table 5).

Plant antimicrobial peptides.

| Peptide type | Source | Structure | Mechanism of action | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thionins | Wheat, barley, barley seeds | Small, cysteine-rich, α/β structure | Membrane permeabilization; disruption of fungal and bacterial membranes | α-Thionin, β-thionin | [118] |

| Defensins | Seeds, leaves, roots | Cysteine-rich, β-sheet stabilized by disulfide bonds | Membrane disruption; inhibition of fungal and bacterial growth; broad-spectrum activity | Rs-AFP1, NaD1 | [119] |

| LTPs | Seeds, leaves | Small, α-helical, cysteine-rich | Membrane destabilization; binds lipids; inhibits bacterial and fungal growth | LTP1, LTP2 | [120] |

| Cyclotides | Clitoria ternatea, Viola spp. | Cyclic cystine knot peptides | Membrane disruption; high stability; broad antimicrobial activity | Kalata B1, cycloviolacin | [121] |

| Snakins | Potato, tomato | Cysteine-rich, helical structure | Membrane permeabilization; antifungal and antibacterial activity | Snakin-1, snakin-2 | [122] |

| Hevein-like peptides | Hevea brasiliensis, other plants | Small, cysteine-rich peptides | Bind chitin; disrupt fungal cell walls; antifungal activity | Hevein, Ac-AMP1 | [123] |

LTPs: lipid transfer proteins.

Microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, produce AMPs called bacteriocins as part of their competitive survival mechanisms under natural conditions. Bacteriocins are ribosomal produced peptides that have strong antimicrobial properties against closely related or rival microbial species [124]. Nisin, which is produced by Lactococcus lactis, Actinobacteria (Streptomyces), and Bacillus, is one of the most well-characterized bacteriocins and is used widely as a natural food additive preservative because of its wide-spectrum activity against Gram-positive bacteria [125]. The mechanism of action of nisin is through the inhibition of cell wall synthesis and membrane disruption. Nisin binds to the lipid II specifically, a precursor molecule in peptidoglycan biosynthesis [126]. Nisin sequesters lipid II, preventing peptidoglycan subunits from being incorporated into the growing bacterial cell wall and causing the loss of cell wall integrity. This inhibition is most lethal for Gram-positive bacteria, where a thick layer of peptidoglycan is essential for survival. Apart from inhibiting cell wall biosynthesis, nisin also causes the formation of membrane pores at regions where lipid II is present. Insertion into the cytoplasmic membrane is promoted by the peptide lipid II complex and results in transient pores that allow small molecules and ions to leak out, causing depolarization and cell death [127]. This two-pronged mechanism, acting on cell wall biosynthesis and membrane integrity, maximizes the bactericidal activity of nisin and reduces the chances of resistance emergence. Bacteriocins like nisin are highly specific and stable owing to post-translational processing and, in certain cases, cyclization. These properties make them prime candidates for therapeutic and commercial uses such as natural preservatives, antimicrobial coatings, and future alternatives to antibiotics [128]. Their multifunctionality, conformational stability, and capacity to hit critical cellular processes highlight the evolutionary and practical importance of microbial AMPs in modulating microbial communities and fighting multi-resistant pathogens (Table 6).

Microbial antimicrobial peptides.

| Peptide type | Source | Structure | Mechanism of action | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriocins | Lactococcus, Bacillus, Streptococcus spp. | Ribosomally synthesized, diverse (α-helical, β-sheet, cyclic) | Membrane permeabilization; inhibition of cell wall synthesis; target-specific bacteria | Nisin, pediocin, lactacin F | [129] |

| Lantibiotics | Lactococcus, Streptococcus spp. | Cyclic, thioether-containing peptides | Bind lipid II; inhibit peptidoglycan synthesis; induce pore formation | Nisin, subtilin | [130] |

| Microcins | E. coli, Enterobacteriaceae | Small, < 10 kDa, cationic peptides | Membrane disruption; inhibit essential enzymes; interfere with DNA/RNA synthesis | Microcin J25, microcin B17 | [131] |

| Gramicidins | Bacillus brevis | Linear α-helical peptides | Form transmembrane ion channels; disrupt the membrane potential | Gramicidin A, gramicidin D | [132] |

| Polymyxins | Paenibacillus polymyxa | Cyclic lipopeptides | Disrupt Gram-negative bacterial outer membranes by binding LPS | Polymyxin B, polymyxin E | [133] |

| Bacitracin | Bacillus subtilis | Cyclic peptide antibiotic | Inhibits cell wall biosynthesis by interfering with bactoprenol recycling | Bacitracin | [134] |

LPS: lipopolysaccharide.

AMPs are a potential new choice to replace traditional antibiotics, especially for the management of multidrug-resistant pathogens. The fast rise in antibiotic resistance, especially due to the overuse and abuse of traditional antibiotics, has made many bacterial infections more difficult to manage [135]. AMPs, by virtue of their novel mechanisms of action, constitute a viable remedy to this major global health challenge. In contrast to traditional antibiotics that frequently attack a single bacterial process, AMPs more often disrupt microbial membranes and, in some cases, affect intracellular activities like nucleic acid synthesis, protein synthesis, or cell wall biosynthesis. Not only does this multi-pronged strategy guarantee speedy eradication of the pathogen, but it also reduces the ability of microorganisms to develop resistance since microorganisms find it difficult to simultaneously develop defences for multiple mechanisms [136]. A number of AMPs are in clinical trials or under investigation for effectiveness against drug-resistant bacteria. For example, human cathelicidin LL-37 shows strong activity against MRSA and Escherichia coli. Defensins, such as α- and β-defensins, also show broad-spectrum activity towards both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Engineered synthetic or modified AMPs are also being developed to be more stable, less toxic, and with better pharmacokinetic properties, thus making them more effective for therapeutic use [137]. Beyond their immediate antimicrobial action, certain AMPs exhibit immunomodulatory activity, augmenting host defence through the recruitment of immune cells, induction of cytokine production, and resolution of inflammation. These two activities steer pathogen elimination and immune modulation further to make them promising candidates as next-generation antimicrobial agents [138, 139]. Overall, the promiscuity, wide spectrum effectiveness, and low resistance propensity make AMPs of great worth in the fight against multidrug-resistant infections and in meeting the acute need for new antimicrobial therapies in modern medicine [140].

AMPs are a part of both microbial defence and tissue repair facilitation and wound healing. This LL-37, a human cathelicidin, has been well studied for its antimicrobial activity and roles in immunomodulation [141]. In the process of wound generation, microbial invasion is a major source of infection risk, and this can potentially hinder healing. AMPs like LL-37 rapidly target and eliminate pathogens, such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses, thus avoiding infection and creating a milieu that supports tissue regeneration. In addition to their antimicrobial activity, AMPs also play an active role in immune cell recruitment and modulation. LL-37, for instance, recruits neutrophils, monocytes, and mast cells to the site of injury and promotes pathogen clearance and the inflammatory stage of healing [142]. It also activates keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, encouraging proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis, vital processes for re-epithelialization and tissue remodelling. AMPs are also able to modulate the production of cytokines, tipping the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory balance against excessive inflammation that could otherwise hinder healing [143]. The multi-functional nature of AMPs can be seen in chronic wounds and diabetic ulcers as well, where malfunctioning immune responses and microbial colonization hinder the process of recovery. The use of AMPs in topical products or hydrogel-based delivery systems has shown enhanced wound closure, diminished microbial load, and enhanced tissue regeneration in animal models [144]. In addition, synthetic and engineered AMPs are under development with increased stability, diminished proteolytic degradation, and optimized activity under difficult wound conditions. In general, the combined antimicrobial, immunomodulatory, and tissue regenerative functions of AMPs make them appealing therapeutic agents for the facilitation of wound healing. Their capacity both to suppress infection and actively induce tissue repair highlights their promise as multifunctional biotherapeutics of clinical medicine and regenerative health care [145].

Medical implants, catheters, and prosthetic devices are widely used in modern medicine but have a high risk of causing infection as a result of microbial colonization and biofilm formation [146]. Biofilms protect pathogens against host immune defences and standard antibiotics, often leading to chronic infections that are difficult to eradicate. AMPs prove to be an attractive option as functional coatings for medical devices with broad-spectrum antimicrobial efficacy and low resistance potential [147]. AMPs may be immobilized or loaded onto device surfaces using several methodologies, such as covalent attachment, layer-by-layer assembly, or encapsulation inside polymer matrices. After application, AMPs dynamically prevent bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation by disrupting microbial membranes upon contact. For instance, cationic and amphipathic peptides bind to negatively charged microbial membranes, promoting pore formation, membrane depolarization, and microbial killing [148]. Acting against early colonizers, AMPs significantly inhibit biofilm formation, ultimately decreasing the risk of device-associated infection, like catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) or prosthetic joint infection. In addition to their antimicrobial activity, some AMPs have immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activities that can promote tissue integration around the device and support host defence [149]. Coatings with LL-37, human defensins, or synthetic mimetics have been shown to have long-term antimicrobial activity, biocompatibility, and low cytotoxicity in preclinical models. The stability and diversity of AMPs also make it possible to tailor them to target specific devices, with controlled release and extended activity in clinical applications [150]. In general, AMP-based coatings are a novel means of diminishing healthcare-associated infections, enhancing implant safety, and prolonging device longevity. Their ability to integrate direct killing of microorganisms, inhibition of biofilms, and immunomodulation highlights their promise as next-generation products in biomedical device technology [151]. The incorporation of AMPs in medical devices represents an active means of combating multidrug-resistant bacteria and improving patient outcomes.

AMPs, specifically bacteriocins like nisin, are widely used as natural food preservatives in the food industry. The growing need for safe, efficient, and minimally processed foods has increased interest in AMPs because of their low toxicity and wide range of antimicrobial activity. Bacteriocins are ribosomally produced peptides from some bacteria, which may be lactic acid bacteria, to inhibit the growth of other competing microorganisms [151]. Nisin, which is derived from Lactococcus lactis, is perhaps the best characterized and most widely used AMP under these circumstances. The major mode of action of nisin is through disrupting cell membranes and inhibiting cell wall biosynthesis. Nisin interacts with lipid II, a critical precursor in peptidoglycan formation in bacteria, thus inhibiting cell wall development and leading to pore formation in the cytoplasmic membrane [152]. This two-way action leads to the quick killing of bacteria, especially against Gram-positive bacteria like Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus species. Its efficacy at low concentrations makes nisin a safe and effective preservative for foods of diverse nature, ranging from dairy foods to canned vegetables and processed meats [153]. Besides antimicrobial action, AMPs such as nisin possess some beneficial features over conventional chemical preservatives. They are non-toxic to humans, biodegradable, and are considered generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by regulatory authorities. Their application can minimize the dependence on synthetic preservatives, which tend to be linked with negative health impacts and consumer acceptance issues. Moreover, AMPs can be used with other preservation methods, i.e., mild heat treatment or packaging changes, to enhance synergistic effects and shelf life [154]. In general, AMPs are a natural, efficient, and safe method for food preservation with quality and safety, responding to consumer needs for clean-label products. Their broad activity, low potential for resistance, and synergy with current food processing technologies make them priority bio-preservatives in the changing food industry.

AMPs are also direct antimicrobial agents and powerful immunomodulators with the potential to boost vaccine efficacy [155]. Some AMPs, like human cathelicidin LL-37 and defensins, act as vaccine adjuvants through immune-modulating effects on the host immune system, thus augmenting antigen-specific responses. Such functionality makes AMPs especially promising for the prevention of infectious diseases and therapeutic vaccine development [156]. The immunomodulatory action of AMPs is through several mechanisms, involving the recruitment and activation of numerous immune cells, e.g., dendritic cells, macrophages, and T lymphocytes, to the site of antigen exposure [157–159]. The recruitment facilitates antigen uptake and presentation and consequently triggers the innate and adaptive immune responses. Furthermore, AMPs also induce the release of cytokines and chemokines, including interleukins and interferons, which further augment immune signalling and coordinate an appropriate inflammatory response. Through a regulation of the immune environment, AMPs allow for the induction of a stronger, more durable, and more precise immune response towards the injected antigen [160]. When employed as vaccine adjuvants, AMPs can enhance the immunogenicity of traditional vaccines, such as subunit or inactivated vaccines that otherwise induce poor immune responses. For example, co-administration of LL-37 with protein antigens has been demonstrated to augment antibody responses, T-cell stimulation, and protective immunity in model systems. Additionally, AMPs are of low toxicity and have very low chances of causing adverse reactions, making them safer options compared to conventional adjuvants like aluminium salts [161]. In conclusion, the combination of antimicrobial properties, recruitment of immune cells, and cytokine modulation makes AMPs multifunctional molecules with much potential for vaccine development. Their capacity to boost both innate and adaptive immunity highlights their potential to serve as the next generation of vaccine adjuvants, with innovative treatments for fighting infectious diseases and enhancing global public health outcomes.

AMPs have shown great promise as anti-cancer medicines since they can specifically kill tumor cells while leaving normal healthy cells intact [162]. Cancer cell membranes tend to possess different biochemical properties than normal cells, such as greater negativity in charge, greater membrane fluidity, and greater expression of anionic molecules such as phosphatidylserine and sialic acid. These properties make cancer cells vulnerable to cationic and amphipathic AMPs, which are able to preferentially interact with and destabilize cancer cell membranes [163]. Membrane disruption is the main mechanism of AMP-induced anti-cancer activity. Cationic peptides, including magainins, LL-37, and derivatives of defensin, react with the negatively charged cancer cell membranes, resulting in pore formation, depolarization of the membranes, and leakage of cellular content. This leads to the quick death of cells, usually through necrosis or apoptosis [164]. Certain AMPs also have intracellular actions, such as interference with mitochondrial function, generation of ROS, and disruption of nucleic acid or protein synthesis, which add to selective tumor cell cytotoxicity. Apart from the direct cytotoxicity, AMPs are also capable of altering the tumor microenvironment. Specific peptides also augment anti-tumor immune responses by enlisting immune cells, inducing cytokine secretion, and activating antigen presentation, resulting in synergistic enhanced tumor clearance [165]. The combined activity of AMPs, direct membrane-targeted cytotoxicity, and immunomodulation presents a benefit over traditional chemotherapeutic agents, which tend to have poor specificity and induce systemic toxicity. Synthetic and engineered AMPs are in development with enhanced stability, bioavailability, and target specificity, and they are promising candidates for cancer treatment [166]. Selective killing of cancer cells, a remote chance of resistance occurrence, and multi-targeting mechanisms highlight the therapeutic potential of AMPs as new cancer drugs [167]. Their incorporation into future oncology approaches could serve as add-on treatments to current therapies, providing safer and more effective options in cancer treatment.

AMPs are measured as capable antiviral agents because they can affect several steps of viral infection, including viral entry, replication, and assembly. Unlike typical antivirals, which act by inhibiting some specific enzyme or replication pathways, AMPs work either through direct virucidal action, disruption of viral membranes, or through immune modulation, thus using broad-spectrum antiviral activity. The peptides LL-37, defensins, and lactoferricin have been confirmed to have strong inhibitory actions against both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses [168]. For example, LL-37 disrupts the viral envelope and inhibits attachment to the host cells of influenza and herpes simplex virus, while human β-defensins interfere with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) replication by blocking viral fusion and reverse transcription [169]. Similarly, indolicidin and magainin-2 exhibit virucidal activity against hepatitis and respiratory viruses. Besides this, AMPs can enhance antiviral immunity by induction of cytokine release and improvement of interferon-mediated defence mechanisms [170]. Structural flexibility agrees modification for increased selectivity and reduced cytotoxicity, important features for therapeutic use. Synthetic and recombinant AMPs are being used as adjuvants in vaccine formulations and topical antiviral agents, mainly in infections at mucosal sites. Low propensity for resistance growth further improves their likely over straight antiviral. Overall, the antiviral effectiveness of AMPs places them as promising candidates for broad-spectrum antiviral therapy, offering new perspectives against emerging and drug-resistant viral pathogens [171].

AMPs have exposed antiparasitic activity against protozoan and helminthic parasites by targeting different modes of action: membrane disruption, inhibition of nutrient uptake, and interference with intracellular signalling pathways. Due to their amphipathic and cationic nature, AMPs can bind negatively charged parasitic membranes, leading to pore formation and following cell lysis [172]. Thus, the best known examples of AMPs are cecropins and magainins, showing strong activity against Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of malaria [173]. Dermaseptins isolated from frog skin were found to lyse Leishmania donovani and Trypanosoma cruzi. Other AMPs, such as temporins, act against Giardia lamblia and Toxoplasma gondii [174]. Moreover, AMPs like defensins interact with the host immune response through the induction of macrophage activation, leading to enhanced parasite killing. Their selective toxicity toward parasites over host cells arises from structural differences in the membrane composition and thus discusses a therapeutic advantage. The direct parasiticidal action of AMPs interferes with parasite transmission by targeting vector stages like mosquito gut parasites or helminth larvae and prophylactic potential [175]. Synthetic analogs and logically engineered AMPs are being developed for improved stability and bioavailability under physiological conditions, which would overcome some limitations forced by the degradation of peptides by proteases. Compared to conventional antiparasitic drugs, AMPs exhibit broader activity spectra, rapid action, and reduced likelihood of resistance. Accordingly, AMPs are strong candidates for next-generation antiparasitic drugs against infections whose global burden has recently increased due to drug-resistant malaria, leishmaniasis, and trypanosomiasis [176].

Antifungal properties of AMPs are gaining interest due to the increasingly irritating problem of resistance to conservative antifungal drugs such as azoles and echinocandins. AMPs exert antifungal effects by causing membrane permeabilization, inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis, or interfering with intracellular targets and eventually inducing fungal cell death. For example, histatins derived from human saliva target mitochondria in Candida albicans and induce ROS formation [177]. Defensins and thionins from plants have a wide antifungal spectrum, which encompasses species belonging to Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Cryptococcus [178]. The fungus-derived plectasin interferes with cell wall biosynthesis by binding to lipid II, using a mode of action different from that utilized by the traditional antifungals. The magainins and lactoferricin disrupt fungal membranes by forming transient pores, leading to the leakage of cellular contents [179]. AMPs are also active against biofilms developed by fungal pathogens during device or mucosa-linked infections. More significantly, AMPs were often shown to act synergistically with existing antifungal agents, with fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) catalogs indicating lower concentrations of the drugs necessary to inhibit growth and hence less toxicity [180]. Immunomodulatory volumes also enhance host defence by employing immune cells and inducing antifungal cytokine production [181]. Multifunctional and adaptable AMPs with their very low tendency to develop resistance represent an excellent class of antifungal therapeutics; systemic and topical formulations can be developed for the treatment of life-threatening, multiresistant fungal infections.

The direct antimicrobial actions of AMPs play an increasingly important role as modulators of the host immune system. They act as immune regulators, bridging innate and adaptive immunity by activating immune cells, modulating cytokine expression, and regulating inflammatory responses. For instance, its antimicrobial properties LL-37 induce chemotaxis of neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells and promotes the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 [182]. Similarly, defensins increase dendritic cell maturation and antigen presentation, thereby contributing to adaptive immune activation. AMPs like hepcidin and cathelicidins regulate iron metabolism and oxidative stress pivotal for maintaining immune homeostasis. Their ability to modulate TLR signalling pathways enables them to finely inflammatory responses and avoid excessive tissue damage [183]. The synthetic analogs of AMPs are being examined in autoimmune and inflammatory disorders based on their ability to suppress hyperinflammation and promote tissue repair. Additionally, AMPs have been reported to have wound healing and angiogenic properties, thus supporting tissue regeneration in chronic wounds and burns. Unlike other immunomodulators, AMPs have the advantage of directly clearing pathogens and enhancing immune responses without leading to immunosuppression [184]. Their multifunctionality and low resistance potential make them attractive candidates for immunotherapeutic development. The immunomodulatory properties of AMPs extended their role from a mere antimicrobial agent to that of an endogenous regulator of immune balance and tissue homeostasis, opening new avenues for innovative anti-inflammatory and immune supportive therapies [185].

AMPs are regarded as one of the most promising and versatile classes of bioactive molecules in modern biomedical research, being recognized not only as important components of innate immunity in a wide range of species but also as powerful candidates for therapeutic and industrial applications. Unique structural features, small molecular size, cationic charge, and amphipathic topology enable selective interaction with negatively charged microbial membranes, ensuring potent, broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, viruses, and even parasites [186]. Unlike traditional antibiotics that are usually associated with single and specific cellular targets, multifaceted mechanisms that include both membrane-disruptive and non-membrane targeting pathways are involved in the action of AMPs [187]. Whereas the barrel stave, toroidal pore, and carpet mechanisms are included in the membrane-disruptive models, which rapidly destabilize and lyse pathogen membranes, other non-membrane targeting activities are used to interfere with nucleic acid replication, protein synthesis, enzyme activity, and cell wall biosynthesis [188]. The probability of resistance development by microbes is significantly reduced by this duality of action, making AMPs particularly valuable in the era of multidrug resistance. The evolutionary conservation of AMPs from mammalian defensins and cathelicidins, amphibian magainins, insect cecropins and attacins, plant thionins and defensins, to microbial bacteriocins like nisin is illustrated in their crucial biological roles and adaptive importance [189]. Specialized structural motifs and mechanisms have evolved in each category, tailored to its ecological niche, thereby offering an extensive molecular reservoir for rational drug design and peptide engineering [190].

Biomedical application of AMPs has been extended far beyond antimicrobial action by recent research, and remarkable roles of AMPs in immunomodulation, wound healing, anti-inflammatory regulation, antiviral defense, and anticancer therapy have been highlighted [191]. In cancer treatment, selective cytotoxicity toward malignant cells is displayed by the subclass of AMPs called anticancer peptides (ACPs) due to differences in membrane composition, including higher negative charge, increased membrane fluidity, and altered lipid distribution in cancer cells [192]. This selectivity allows for tumor cell membranes to be disrupted, apoptosis to be induced, angiogenesis to be inhibited, and immune responses within the tumor microenvironment to be modulated by ACPs. Conventional chemoresistance mechanisms can be bypassed by their ability, which further strengthens their significance as adjuncts or alternatives to traditional cancer therapeutics [193]. Immunotherapeutic properties are also exhibited by many AMPs through the enhancement of antigen presentation, stimulation of cytokine production, and bridging of innate and adaptive immunity; thus, interest is generated for vaccine adjuvancy and immunotherapy applications. In wound healing, the proliferation of keratinocytes, migration of fibroblasts, deposition of collagen, and angiogenesis are promoted by AMPs while infection at the wound site is prevented [194]. A place in regenerative medicine, particularly in tissue engineering scaffolds and advanced wound dressings, is offered to them by this multi-functionality.

Advancements in peptide engineering and chemical modifications, as well as progress in nanotechnology, have considerably widened AMP translational perspectives. Peptide modification strategies, such as cyclization, substitution with D-amino acids, PEGylation, and lipidation, are used to improve peptide stability, reduce susceptibility to proteolytic degradation, and assure better bioavailability [195]. Nanocarrier-based delivery systems, including liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, hydrogels, and dendrimers, are employed to enable controlled release, targeted delivery, and reduced cytotoxicity, further addressing some major challenges of AMP clinical application. Computational modeling, combined with artificial intelligence and machine learning, facilitated the accelerated identification, optimization, and de novo design of AMPs with improved potency, selectivity, and physicochemical properties [196]. Enhanced efficacy and a reduction of therapeutic doses, with minimal toxicity and the potential to overcome persistent resistance, have been displayed by synergistic approaches, in which conventional antibiotics or antifungal drugs are combined with AMPs.