Affiliation:

Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, The University of Bamenda, Bambili P.O. Box 39, Cameroon

Affiliation:

Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, The University of Bamenda, Bambili P.O. Box 39, Cameroon

Affiliation:

Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, The University of Bamenda, Bambili P.O. Box 39, Cameroon

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0488-841X

Affiliation:

Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, The University of Bamenda, Bambili P.O. Box 39, Cameroon

Email: knavti@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2982-8007

Explor Drug Sci. 2025;3:1008136 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2025.1008136

Received: September 24, 2025 Accepted: November 26, 2025 Published: December 15, 2025

Academic Editor: Weilin Jin, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, China

Aim: Diabetes mellitus is a serious public health problem, and the condition is managed using herbal medicine by many African traditional healers. This study aimed to provide scientific evidence on the effects of aqueous and ethanol extracts of Xymalos monospora (X. monospora) leaves on some biochemical parameters in diabetic rats.

Methods: This experiment included 63 male Wistar rats. Diabetes was induced for 10 days by intraperitoneal injection of dexamethasone (16 mg/kg) in overnight fasted rats. The diabetic rats were treated with aqueous (100 and 200 mg/kg) and ethanol (100 and 200 mg/kg) extracts of X. monospora leaves and metformin (40 mg/kg) for 15 days. Fasting blood glucose, serum lipid profile, atherogenicity indices (Castelli’s Risk Index, Atherogenic Coefficient, Atherogenic Index of Plasma), tumor necrosis factor alpha, and hepatic glycogen were evaluated.

Results: Treatment with the aqueous extracts at 100 and 200 mg/kg significantly reduced fasting blood glucose by 29.2% (p = 0.016) and 35.9% (p = 0.009), respectively. Also, the ethanol extracts at 100 and 200 mg/kg significantly reduced fasting blood glucose by 20.7% (p = 0.038) and 31.2% (p = 0.027), respectively. The aqueous extract (200 mg/kg) significantly reduced total cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations by 31.5% (p = 0.017) and 30.7% (p = 0.023), respectively. There was a significant reduction in atherogenicity indices (p < 0.05), and liver glycogen levels improved. The extracts reduced the levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha, but this was not significant (p > 0.05). However, histopathological studies were not carried out, and the above findings may not directly translate to clinical efficacy.

Conclusions: These findings demonstrate that the oral administration of aqueous and ethanol extracts of X. monospora leaves has significant antidiabetic effects, including a decrease in fasting blood glucose, improvement of serum lipid profile, and increased glycogen storage.

Diabetes mellitus is a long-term endocrine disorder characterized by disturbances in carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, and currently remains a major global public health problem. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) report of 2025 indicates that by 2050, the number of people with diabetes in Africa is going to increase by 142% [1]. There has been a slight decline in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus among adults in Cameroon from 6.5% in 2015 [2] to 5.8% in 2018 [3] and then to 5.6% in 2024 [1]. This decline could be attributed to increasing sensitization and awareness of long-term complications of the disease, which have led to changes in lifestyle among people living with diabetes.

There are many commercially available antidiabetic drugs, which belong to various classes (biguanides, thiazolidinediones, sulphonylureas, and meglinides) that are used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. However, these drugs exhibit different side effects, can affect other organs in the body, and interfere with other non-antidiabetic drugs when used for a long duration [4, 5]. Also, the economic burden of the disease on those affected is immense. For instance, the estimated direct medical cost of diabetes for an individual in a month in Cameroon has been rising steadily from $123 in 2015 [2] to $148 in 2019 [6] and then to $252 in 2024 [1]. In order to avoid side effects and minimize cost, some patients are now considering the use of herbal medicine in the treatment of diabetes [7].

There has been a growing interest in the use of herbal medicine globally [8], and it is no different in Cameroon [9]. Recent evidence reveals that herbal medicine is a safer alternative and can minimize complications associated with diabetes [7, 10]. Herbal medicine from different plants has been shown to affect biochemical parameters that are associated with diabetes mellitus. For instance, previous reports on extracts of Vincor major [11] and Euphorbia thymifolia [12] significantly reduced fasting blood glucose (FBG) concentration and improved dyslipidemia in diabetic rats. The Euphorbia thymifolia extract was shown to increase hepatic glycogen concentration and decrease the HbA1c level in diabetic rats [12]. Also, an herbal formula (Mathurameha) in Thailand that included 26 medicinal plants was found to improve total cholesterol (TC) concentration and other biochemical parameters in diabetic rats. However, the rats had increased triglyceride (TG) levels, and the authors suggested that the formula may not be beneficial in lipid homeostasis [13]. In addition, extracts of Cornus mas L. significantly improved dyslipidemia and reduced the levels of atherogenic indices [Castelli’s Risk Index (CRI), Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP), Atherogenic Coefficient (AC)] in diabetic rats, thus reducing cardiovascular risk [14]. Moreover, the aqueous extract of Pterocarpus marsupium significantly decreased the elevated level of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in a diabetic rat model [15]. Previous reports have indicated that leaf extracts of Adenanthera pavonina [16] and some Nepalese medicinal plants (Acacia catechu, Dioscorea bulbifera, and Swertia chirata) [17] exhibited α-amylase inhibitory activity.

In Cameroon, many plants have been documented for the treatment of diabetes mellitus and its complications. For example, a previous ethnomedical survey revealed one hundred and three (103) plant species that are used in the treatment and management of diabetes mellitus [18]. Other reports had identified eighty-five, forty-one, and forty-nine plant species used in the treatment of diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and cardiovascular ailments in the South [19], Littoral [20], and West [21] regions of Cameroon, respectively. In the North West Region of Cameroon, Xymalos monospora (X. monospora) is used by some traditional practitioners in the treatment of diabetes and its complications. There is a paucity of data on the scientific exploitation of this plant. However, a recent study revealed that green tea produced from the leaves of X. monospora has comparable nutritional properties to commercially available green tea [22].

To the best of our knowledge, there is no scientific evidence on the use of X. monospora in the treatment of diabetes mellitus and its complications, and it does not feature amongst the enlisted plant species in the above ethnomedical studies in Cameroon. The aim of this study, therefore, is to investigate the effect of oral administration of aqueous and ethanol extracts of X. monospora leaves on some biochemical parameters in dexamethasone-induced diabetes in male Wistar rats.

Metformin tablets (500 mg, Chemical Abstracts Service—CAS number 657-24-9, manufacturer’s name: Aetos Pharma Private Limited, purity: ~ 99%), dexamethasone (4 mg/mL, CAS number 50-02-2, manufacturer’s name: Jeil Pharma, purity: ≥ 98%), diazepam (5 mg/mL, CAS number 439-14-5, manufacturer’s name: Pfizer, purity: ≥ 98%), and ketamine hydrochloride (50 mg/mL, CAS number 6740-88-1, manufacturer’s name: Pfizer, purity: > 99%) were purchased from a pharmacy in Bamenda, North West Region of Cameroon.

The fresh leaves of X. monospora were harvested from Oshie in Njikwa sub-Division, North West Region of Cameroon, and authenticated by a botanist in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Bamenda. A sample of the plant material was forwarded to the Natural Herbarium Center in Yaoundé, Cameroon, and authenticity was confirmed as Xymalos monospora (Harv.) Baill ex Warb with reference number 50557/HNC.

Three kilograms (3 kg) of fresh leaves were weighed using a weighing balance, washed with clean tap water, and chopped into smaller pieces using a knife. The chopped leaves were ground using a domestic mixer (Philips, HL7505, India). Distilled water was added to the ground leaves, and the mixture was allowed to soak for 24 h. After 24 h, the mixture was filtered through Whatman No. 1. The extract was dried in an oven (Memmert UF, Germany) for 24 h at a temperature of 50°C to obtain 60.4 g of powder. The extract was kept in an air-tight container and stored in a laboratory refrigerator (Fison, FM-LRF-A203, UK) at 4°C until use [13].

Three kilograms (3 kg) of fresh leaves were processed as mentioned above. This was followed by the addition of 70% ethanol, and the whole was allowed to macerate for 24 h. After 24 h, the mixture was filtered through Whatman No. 1, and the extract was concentrated using a vacuum in a rotatory evaporator (Buchi Rotavapor R-300, Switzerland) at 50°C [17]. The extract obtained was 57.9 g and was kept in an air-tight container and stored in a laboratory refrigerator at 4°C until use.

The experimental rats used in this study included 63 healthy eight-week-old male Wistar albino rats of body weight ranging from 190 to 220 g. The rats were obtained from the animal house of the Faculty of Science, the University of Bamenda. The rats were kept in plastic cages that were covered with mesh and included facilities for food and water. The rats were monitored under standard conditions (ambient temperature 25 ± 2°C) and a 12-hour light/dark cycle in a well-ventilated section of the animal house of the Faculty of Science, the University of Bamenda. The rats also had free access to food and water ad libitum under good hygienic conditions. The rats were acclimatized for two weeks before the experiment.

After the acclimatization period, type 2 diabetes was induced for 10 days by daily intraperitoneal injection of dexamethasone (16 mg/kg b.w.) [23] to overnight fasted experimental rats. Wistar rats with FBG concentration > 200 mg/dL) were considered to be type 2 diabetic [24].

The 63 rats were randomly assigned into seven groups of 9 rats each, and oral treatment was carried out for 15 days, as shown in Table 1 below:

Description of experimental animal groups and treatment.

| Groups | Description with dose |

|---|---|

| Group 1 | Normal control: non-diabetic rats receiving distilled water (10 mL/kg b.w.) |

| Group 2 | Diabetic control: diabetic rats receiving distilled water (10 mL/kg b.w.) |

| Group 3 | Standard drug control: diabetic rats treated with metformin (40 mg/kg b.w.) |

| Group 4 | Diabetic rats treated with X. monospora aqueous leaf extract—XMAq (100 mg/kg b.w.) |

| Group 5 | Diabetic rats treated with X. monospora aqueous leaf extract—XMAq (200 mg/kg b.w.) |

| Group 6 | Diabetic rats treated with X. monospora ethanol leaf extract—XMEt (100 mg/kg b.w.) |

| Group 7 | Diabetic rats treated with X. monospora ethanol leaf extract—XMEt (200 mg/kg b.w.) |

b.w.: body weight; X. monospora: Xymalos monospora; XMAq: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora aqueous leaf extract; XMEt: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora ethanol leaf extract.

The above doses of the extracts were chosen based on previous studies on the antidiabetic activity of extracts of leaves from different plants, in which the doses ranged from 20 mg/kg b.w. to 250 mg/kg b.w. [25].

Blood samples were collected from overnight fasted rats the day before commencement of treatment (day 0), and during treatment days (day 1, day 5, day 10, and day 15), and FBG was determined. At the end of the 15 days of treatment, the rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of diazepam (10 mg/kg b.w.) combined with ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg b.w.). Following anesthesia, the animals were sacrificed humanely by cervical dislocation [26]. Blood samples were collected from each rat by cardiac puncture and transferred into non-heparinized centrifugal tubes. The blood samples were kept for 30 min to clot. Centrifugation was later carried out at 1,005 × g for 30 min to obtain the serum fraction. The serum was separated, preserved in a deep freezer at –20°C, and subsequently used for analysis of biochemical parameters. The liver was also collected after appropriate dissection, washed in cold saline, dried with filter paper, weighed, and preserved at –20°C for subsequent analysis.

FBG: FBG was determined using a glucometer and diagnostic strips (Accu-Check Performa, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany). The readings were recorded in triplicate.

Serum lipids and atherogenicity indices: The serum lipid profile [TC; TG; and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)] was determined enzymatically with test kits using an automated biochemical analyzer (Randox Laboratories, England). Also, the Friedewald equation [27] was used to calculate the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration. Atherogenicity indices were calculated as follows: CRI-I = TC/HDL-C; CRI-II = LDL-C/HDL-C; AC = (TC – HDL-C)/HDL-C [28], and AIP = log (TG/HDL-C) [29].

TNF-α: The concentration of TNF-α in serum was estimated by using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELIZA) technique, which employs the Rat ELISA kit (R&D Systems, USA). The procedure indicated by the manufacturer was followed, and the readings were recorded in pg/mL.

Hepatic glycogen: For hepatic glycogen content, 50 mg of each liver sample was placed in centrifuge tubes containing 1 mL of 30% potassium hydroxide. The tubes were closed and placed in a boiling water bath for 20 min. The tubes were allowed to cool, and 1.5 mL of 95% ethanol was added to each tube and stirred using a stirring rod. The solution in the tube was gently brought to a boil in a boiling water bath. The tubes were allowed to cool and then centrifuged at 1,005 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was decanted, and the centrifuge tubes were well drained. The precipitate in each tube was re-dissolved in 2 mL of distilled water, reprecipitated by adding 1.5 mL of 95% ethanol, centrifuged, and supernatant decanted. The pellet in each tube was dissolved in 2 mL of distilled water, and the tubes were agitated, and glycogen was measured using the anthrone reagent [30]. Glycogen content was expressed as milligrams per gram of liver tissue (mg/g).

Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM-SPSS for Windows version 27.0 (Armonk, New York, USA). Continuous data has been presented using mean ± standard error of the mean. Differences in means of body weight gain, atherogenicity indices, TNF-α, liver glycogen, and serum lipid concentrations were compared between experimental groups using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons. The comparison of mean FBG between the different animal groups and across the treatment days was carried out using a univariate general linear model followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

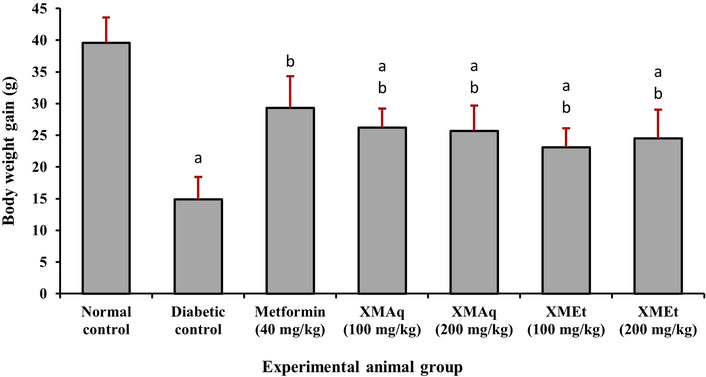

Body weight was monitored during treatment, and the mean weight gain in each group is presented in Figure 1. Weight gain in the diabetic control group (14.9 g) was significantly (p < 0.05) lower than the normal control group (39.6 g). There was no significant difference in weight gain between the metformin group and the normal control group. The rats that received metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 mg/kg), XMAq (200 mg/kg), and XMEt (100 mg/kg) significantly gained more weight (ranging from 23.1–29.3 g) than those in the diabetic control group (14.9 g). However, the weight gain was still lower than the normal control group. Weight gain was not significantly different between the metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 mg/kg), XMAq (200 mg/kg), XMEt (100 mg/kg), and XMEt (200 mg/kg) groups.

Effects of aqueous (XMAq at 100 and 200 mg/kg) and ethanol (XMEt at 100 and 200 mg/kg) extracts of X. monospora leaves and metformin (40 mg/kg) on weight gain in dexamethasone-induced diabetes in rats. ap < 0.05 compared to the normal control group, bp < 0.05 compared to the diabetic control group. XMAq: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora aqueous leaf extract; XMEt: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora ethanol leaf extract.

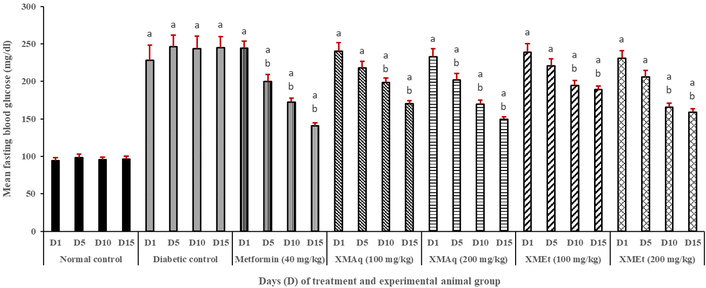

Figure 2 shows that rats in all groups (except those in the normal control group) were diabetic on day 1, at the commencement of treatment. The FBG remained high in the diabetic control group, ranging from 228.1–246.1 mg/dL throughout the experiment when compared to the corresponding treatment days in the normal control group (94.3–98.1 mg/dL). Also, FBG significantly (p < 0.05) reduced from 244.3 mg/dL to 200.1, 172.1, and 140.6 mg/dL on days 5, 10, and 15, respectively, in the metformin group when compared to the corresponding days of the diabetic control group. A similar decline in FBG was observed in the XMAq (200 mg/kg) group (from 232.9 mg/dL to 149.2 mg/dL). In the XMAq (100 mg/kg) and XMEt (100 and 200 mg/kg) groups, a significant decrease in FBG was observed on days 10 and 15 when compared to the corresponding days in the diabetic control group. However, the values remained significantly higher than those in the normal control group. During the experiment, animals in the metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 mg/kg), XMAq (200 mg/kg), XMEt (100 mg/kg), and XMEt (200 mg/kg) groups experienced a significant decrease in FBG, with p-values for trends: 0.002, 0.016, 0.009, 0.038, and 0.027, respectively.

Effects of aqueous (XMAq at 100 and 200 mg/kg) and ethanol (XMEt at 100 and 200 mg/kg) extracts of X. monospora leaves and metformin (40 mg/kg) on fasting blood glucose in dexamethasone-induced diabetes in rats. ap < 0.05 compared to the normal control group, bp < 0.05 compared to the diabetic control group. XMAq: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora aqueous leaf extract; XMEt: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora ethanol leaf extract.

The changes in TC, TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C concentrations in the different groups are presented in Figure 3. TC was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the diabetic control group (141.2 mg/dL) compared to the normal control group (88.6 mg/dL). There was a significant decrease in the concentrations of TC in the metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 and 200 mg/kg), and XMEt (100 and 200 mg/kg) groups when compared to the diabetic control group. Similarly, in diabetic rats, the concentrations of TG (136.7 mg/dL) and LDL-C (86.8 mg/dL) were significantly increased when compared to rats in the corresponding normal control groups (87.6 and 30.6 mg/dL, respectively). Treatment with metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 and 200 mg/kg), and XMEt (100 and 200 mg/kg) resulted in a significant decrease in TG and LDL-C when compared to the diabetic control groups. The untreated rats had a significantly lower HDL-C concentration (32.9 mg/dL) when compared to the normal rats (60.2 mg/dL). After treatment of diabetic rats with metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 mg/kg), XMAq (200 mg/kg), XMEt (100 mg/kg) and XMEt (200 mg/kg), the HDL-C concentrations increased to 53.8, 47.3, 52.1, 45.4 and 46.8 mg/dL respectively when compared to rats in the diabetic control group (32.9 mg/dL).

Effects of aqueous (XMAq at 100 and 200 mg/kg) and ethanol (XMEt at 100 and 200 mg/kg) extracts of X. monospora leaves and metformin (40 mg/kg) on serum lipids in dexamethasone-induced diabetes in rats. ap < 0.05 compared to the normal control group, bp < 0.05 compared to the diabetic control group. XMAq: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora aqueous leaf extract; XMEt: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora ethanol leaf extract.

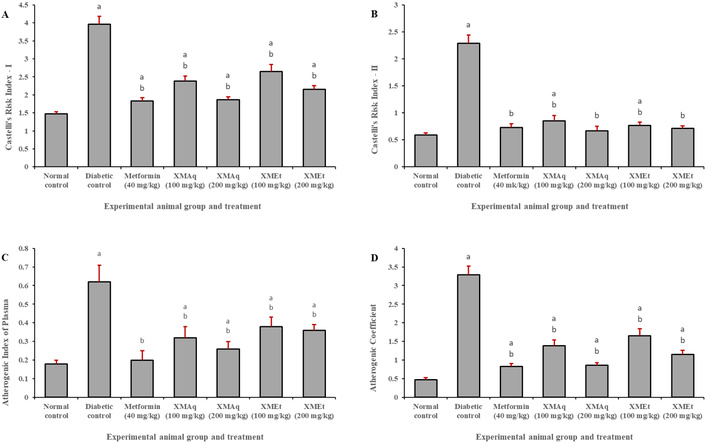

The value of the CRI-I was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in untreated diabetic rats (3.96) when compared to rats in the normal control group (1.47). A similar finding was observed for CRI-II. The diabetic rats that received metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 and 200 mg/kg), and XMEt (100 and 200 mg/kg) had significantly lower CRI values when compared to untreated diabetic rats (Figure 4A and 4B). Similarly, a significant decrease in AIP and AC was observed in rats treated with metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 and 200 mg/kg), and XMEt (100 and 200 mg/kg) when compared to the corresponding diabetic control groups (Figure 4C and 4D). However, the values remained significantly higher in the groups of rats that received extracts of X. monospora than the corresponding values in the normal control groups.

Effects of aqueous (XMAq at 100 and 200 mg/kg) and ethanol (XMEt at 100 and 200 mg/kg) extracts of X. monospora leaves and metformin (40 mg/kg) on atherogenicity indices (A, Castelli’s Index I; B, Castelli’s Index II; C, Atherogenic Index of Plasma and D, Atherogenic Coefficient) in dexamethasone-induced diabetes in rats. ap < 0.05 compared to the normal control group, bp < 0.05 compared to the diabetic control group. XMAq: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora aqueous leaf extract; XMEt: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora ethanol leaf extract.

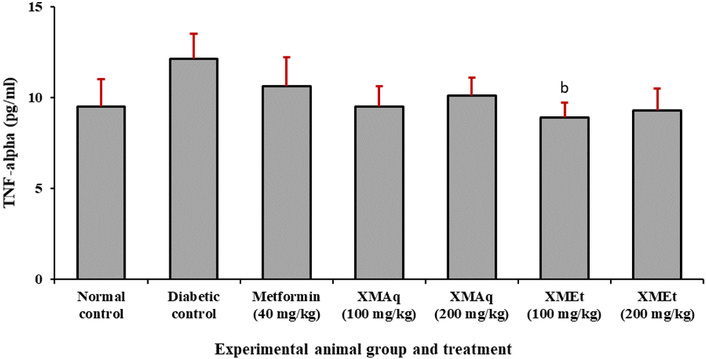

Figure 5 indicates that TNF-α was higher in the diabetic control group (12.1 pg/mL) when compared to the normal control group (9.5 pg/mL). However, this difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). A decrease in TNF-α concentration was observed in rats treated with metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 and 200 mg/kg), and XMEt (100 and 200mg/kg) when compared to untreated rats. However, the decrease (8.9 pg/mL) was statistically significant only in animals treated with XMEt (100 mg/kg).

Effects of aqueous (XMAq at 100 and 200 mg/kg) and ethanol (XMEt at 100 and 200 mg/kg) extracts of X. monospora leaves and metformin (40 mg/kg) on TNF-α in dexamethasone-induced diabetes in rats. ap < 0.05 compared to the normal control group, bp < 0.05 compared to the diabetic control group. XMAq: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora aqueous leaf extract; XMEt: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora ethanol leaf extract.

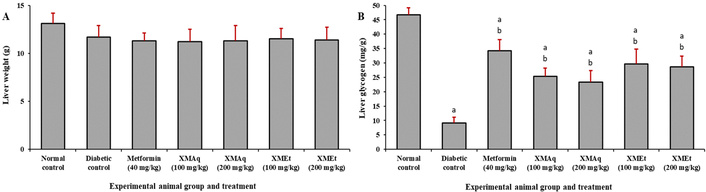

There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in liver weight of rats in all experimental groups (Figure 6A). The liver glycogen in untreated diabetic rats was significantly (p < 0.05) lower (9.2 mg/g) than that of the normal control rats (46.7 mg/g). The liver glycogen level in rats that received metformin (40 mg/kg), XMAq (100 and 200 mg/kg), and XMEt (100 and 200 mg/kg) significantly increased when compared to the diabetic rats that were not treated. However, these values remained significantly lower than the normal control group (Figure 6B).

Effects of aqueous (XMAq at 100 and 200 mg/kg) and ethanol (XMEt at 100 and 200 mg/kg) extracts of X. monospora leaves and metformin (40 mg/kg) on liver weight (A) and liver glycogen (B) in dexamethasone-induced diabetes in rats. ap < 0.05 compared to the normal control group, bp < 0.05 compared to the diabetic control group. XMAq: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora aqueous leaf extract; XMEt: diabetic rats treated with X. monospora ethanol leaf extract.

This study set out to investigate the effects of aqueous and ethanol extracts of X. monospora leaves on some biochemical parameters in diabetic rats. The study reveals that the extracts of X. monospora have the potential to significantly reduce hyperglycemia and improve body weight, dyslipidemia, atherogenicity indices, and liver glycogen levels in dexamethasone-induced diabetic rats. The extracts also reduced the levels of TNF-α, but this was not statistically significant.

Previous reports indicate that dexamethasone induces diabetes in rats primarily through mechanisms that cause insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. It reduces insulin sensitivity by disrupting insulin signaling pathways, including downregulating insulin receptors in skeletal muscle, resulting in decreased glucose uptake [31]. Also, dexamethasone increases hepatic gluconeogenesis and alters lipid metabolism, contributing to elevated glucose levels and dyslipidemia [32]. In addition, chronic administration can lead to changes in glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) levels and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) activity, aggravating hyperglycemia [33].

In this study, the rats that received the extracts of X. monospora significantly gained more weight than the rats in the diabetic control group. This is similar to the findings of a report in which rats treated with Perila fructescens seed residue extract gained more weight than untreated rats, which progressively lost weight [34]. The decrease in body weight observed in this study could be because the administration of dexamethasone was associated with muscle atrophy, leading to weight loss or reduced weight gain [35], especially in the untreated diabetic rats.

This study reveals that the administration of dexamethasone resulted in hyperglycemia in rats. However, the treatment with metformin and the X. monospora extracts resulted in a significant decrease in FBG. Similar findings were obtained with extracts of Vincor major [11] and Euphorbia thymifolia [12]. Metformin reduces blood glucose levels in diabetes mainly by inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis and reducing intestinal glucose absorption. It decreases glucose production in the liver while enhancing insulin sensitivity [36] by increasing the expression and translocation of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) to the plasma membrane, facilitating glucose uptake in peripheral tissues [37]. In addition to the above, it is possible that treatment of rats with the extracts of X. monospora activated adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which plays a crucial role in insulin signaling pathways, improving insulin-mediated glucose disposal and reducing hepatic glucose production [38].

The results in Figure 3 indicate that the administration of dexamethasone resulted in abnormal serum lipid concentrations (dyslipidemia) in diabetic rats. The increase in TC, TG, and LDL-C observed in this study could be due to an increase in cholesterolgenesis, fatty acid absorption, and deposition as TG in the liver [39]. However, the treatment with metformin and X. monospora leaf extracts showed significant lipid-lowering activity, and these findings are consistent with previous studies on different plant extracts [12, 13]. The improvement in dyslipidemia observed in this study can be explained by different mechanisms. For instance, it may be due to the fact that metformin and the extracts modulate cholesterol metabolism via the carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP), linking glucose and lipid homeostasis [40]. It is also possible that the reduction in TG and LDL-C is mediated by the modulation of lipid metabolism pathways, including the suppression of the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), a key regulator of LDL-C receptors, thereby increasing the absorption of LDL-C [41]. In addition, treatment with metformin and the X. monospora leaf extracts could enhance the clearance of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL).

TG by promoting their uptake in adipose tissue, thus increasing lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation [42]. Moreover, the treatments could positively affect HDL-C levels in diabetic rats by inhibiting glycation and oxidative modification of HDL-C, thus improving its functionality [40]. However, the reduction in TG levels observed was slight.

The treatments with X. monospora leaf extracts significantly decreased the atherogenicity indices, which are important predictors of the risk of atherosclerosis and cardiac complications. For instance, the CRI-I and CRI-II were significantly decreased, reflecting a reduction in coronary plagues in diabetes [14]. Also, the AIP decreased significantly after treatment with extracts, and this reflects a reduction in the risk of hypertension and coronary events [43]. In addition, the AC decreased after treatment, and this could contribute to a reduction of the atherogenic potential of the lipoprotein fraction in blood [14]. Although all atherogenicity indices reduced after the 15 days of treatment, the values remained significantly higher than those of the diabetic control group. This suggests that treatment for a longer duration may reduce the atherogenicity indices to acceptable levels.

In this experiment, the levels of TNT-α in the diabetic rats were numerically elevated but statistically not significant when compared to rats in the normal control group. A study carried out by Lestari et al. [44] on Phaleria macrocarpa (Scheff.) Boerl leaf extract resulted in similar results. A previous report showed that TNF-α plays a crucial role in the development of insulin resistance and inflammation in diabetes. Elevated levels of TNF-α have been linked to obesity-induced insulin resistance, mainly through mechanisms that alter insulin signaling pathways, such as increased serine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) and the reduction of GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue [45, 46]. Treatment of the rats with metformin and extracts of X. monospora leaves resulted in reduced levels of TNF-α, though not significantly. This can be explained by the fact that metformin and the extracts decreased the secretion of TNF-α from adipose tissue, which is often elevated in diabetes, thus improving insulin sensitivity [44]. Also, the treatments could counteract the TNF-α-induced serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, thus restoring the function of the insulin receptor [45].

Rats that received metformin and the extracts had significantly higher liver glycogen than untreated diabetic rats. Previous studies found similar results with the extracts from Euphorbia thymifolia [14] and Lithocarpus polystaachyus Rehd [47]. This could be because the treatments upregulate the expression of the insulin receptor β (IRβ) and improve the phosphorylation of IRS-2, leading to an increase in glycogen synthase activity and a decrease in glycogen phosphorylase activity. Additionally, the treatments could inhibit hepatic gluconeogenesis via AMPK and mitochondrial inhibition, which alters the cellular energy state to favor glycogen synthesis over glucose production [38, 48]. However, experiments are needed to determine if the extracts exhibit the above mechanisms.

It is worth noting that liver glycogen improved but remained below normal in all treatment groups. This partial restoration of glycogen had been observed in a previous study, which used ethanol extract of Grewia asiatica Linn. bark [49]. The extracts used in the current study may not have fully restored normal insulin function or all pathways of glycogen synthesis. It is also possible that the dose of the extracts and duration of treatment could explain this partial restoration of liver glycogen. No significant difference in liver weight was observed between the experimental groups.

This study has some limitations worth mentioning. The small sample may affect the variability of parameters assessed, and the selected doses and duration of treatment may not capture the long-term effects of the extracts. Also, histopathological studies were not carried out, and this limits direct clinical extrapolation of the findings.

In conclusion, this study has revealed that the aqueous and ethanol extracts of X. monospora leaves have the potential to reduce FBG, improve dyslipidemia, reduce atherogenicity indices, and increase hepatic glycogen storage in dexamethasone-induced diabetes in rats. Further investigations need to exploit different doses as well as the histopathological activities of the extracts.

AC: Atherogenic Coefficient

AIP: Atherogenic Index of Plasma

AMPK: adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

CRI: Castelli’s Risk Index

FBG: fasting blood glucose

GLUT4: glucose transporter type 4

HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

TC: total cholesterol

TG: triglyceride

TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha

The authors are grateful to the staff of the Animal House and Laboratory of the Faculty of Science at the University of Bamenda for their technical contributions to the realization of this study.

AAA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. MAG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. BUSF: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. LKN: Validation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

All the animals used in this study were treated in accordance with the ‘Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’. Approval for this study was granted by the Ethical Review Committee/Institutional Review Board of the University of Bamenda (Ref. No. 2024/0113H/UBa/IRB).

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The datasets generated/analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 880

Download: 22

Times Cited: 0