Affiliation:

1Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200011, China

Email: lzr_0108@sjtu.edu.cn

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4923-0088

Affiliation:

1Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200011, China

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3277-8920

Affiliation:

1Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200011, China

†These authors contributed equally to this work.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8400-4356

Affiliation:

2Shanghai Stomatological Hospital & School of Stomatology, Fudan University, Shanghai 200001, China

Email: jingj1031@163.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5528-7583

Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2025;5:1004131 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2025.1004131

Received: September 20, 2025 Accepted: December 17, 2025 Published: December 22, 2025

Academic Editor: Antonio Ibarra, Anahuac University, Mexico; Rafael Franco, Universidad de Barcelona, Spain

The article belongs to the special issue Role of Microbiota in Neurological Diseases

The oral microbiome has been increasingly implicated in the development and progression of neurological disorders. This narrative review synthesizes contemporary literature on alterations of oral microbial communities in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and migraine and evaluates their potential contribution to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. We first outline the core oral taxa that maintain microbial homeostasis and summarize evidence that patients with these neurological conditions exhibit dysbiosis characterized by reduced diversity and enrichment of periodontal pathogens. Proposed mechanisms include hematogenous or neural translocation of oral bacteria and their virulence factors, amplification of systemic inflammation, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, altered production of neuroactive metabolites, and bidirectional signaling along the ‘oral-gut-brain’ axis. On this mechanistic basis, microbiome-targeted strategies, particularly probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation, have been explored as adjunctive approaches to restore microbial balance and potentially improve neurological outcomes, although available clinical data remain preliminary and heterogeneous. Current evidence is further limited by small samples, methodological variability in microbiome profiling, and a paucity of longitudinal and interventional studies, which hampers causal inference. Future research should adopt standardized sampling and multi-omic approaches and prioritize well-designed clinical trials to determine whether modulation of the oral microbiome can be translated into preventive or therapeutic strategies for neurological diseases.

The oral microbiome is a diverse and complex ecosystem comprising numerous microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea, which inhabit the oral cavity. This microbial community plays a crucial role in maintaining oral health and overall physiological balance. The oral microbiome is involved in various essential functions, such as the metabolism of nutrients, regulation of immune responses, and protection against pathogens. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in the composition of the oral microbiome, can lead to various health issues, including oral diseases like periodontitis and dental caries, as well as systemic conditions that extend beyond the oral cavity. Recent studies have highlighted the significance of the oral microbiome in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, suggesting that changes in oral microbial composition may influence neurological health and disease outcomes [1].

In recent years, an increasing body of research has uncovered potential links between the oral microbiome and various neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). The mechanisms underlying these associations are complex and multifaceted, involving interactions between the oral microbiome, systemic inflammation, and neuroinflammatory processes. For instance, oral pathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) have been implicated in the progression of AD through mechanisms that promote neuroinflammation and disrupt the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Additionally, dysbiosis in the oral microbiome may lead to the production of metabolites that further exacerbate neuroinflammation and cognitive decline [2]. As our understanding of the oral-gut-brain axis evolves, it becomes increasingly clear that the oral microbiome may serve as a critical player in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders.

The etiology of neurological diseases is inherently complex, involving a myriad of factors, including genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and lifestyle choices. While genetic factors provide a foundational risk for conditions such as multiple sclerosis and AD, environmental influences, including dietary habits and exposure to toxins, play a significant role in disease manifestation and progression. This interplay between genetic and environmental factors underscores the importance of a holistic approach to understanding neurological health [3]. In this context, the oral microbiome emerges as a modifiable factor that may offer therapeutic opportunities for intervention in neurological diseases. By exploring the relationships between oral health, microbial diversity, and neurological outcomes, researchers aim to identify novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies that could improve patient care and outcomes.

This review aims to synthesize current knowledge regarding the role of the oral microbiome in neurological diseases, focusing on the underlying mechanisms of dysbiosis and its clinical implications. By examining the interplay between oral microbial communities and neurological health, we seek to provide insights into the potential for microbiome-targeted interventions in the prevention and management of neurodegenerative diseases. This comprehensive overview will serve as a valuable reference for researchers and clinicians interested in the emerging field of microbiome research and its implications for neurological health. Understanding the oral microbiome’s contributions to systemic health and disease may pave the way for innovative therapeutic approaches aimed at restoring balance and promoting overall well-being [4].

We hypothesize that alterations in oral microbial composition can initiate systemic inflammation and propagate neuroinflammatory cascades, compromising BBB integrity and modulating microglial activation, which collectively accelerate neuronal dysfunction and degeneration through the ‘oral-gut-brain’ axis. In addition, we propose that profiling the salivary microbiome could serve as a non-invasive diagnostic tool for early detection of neurological diseases, providing valuable biomarkers for identifying individuals at risk for these conditions.

This narrative review was conducted to synthesize current evidence regarding the association between oral microbiome dysbiosis and neurological diseases. A comprehensive literature search was performed using PubMed/MEDLINE and Web of Science databases for studies published between January 2015 and November 2025. The search strategy combined keywords and MeSH terms, including “oral microbiome,” “oral microbiota,” “periodontitis,” “Alzheimer’s disease,” “Parkinson’s disease,” “migraine,” “multiple sclerosis,” “neuroinflammation,” and “neurodegeneration.”

Studies were included if they (1) investigated the composition, diversity, or function of the oral microbiome in relation to neurological diseases; (2) involved human, animal, or in vitro experimental data relevant to oral microbial dysbiosis; and (3) were published in English. Exclusion criteria included conference abstracts, single case reports, studies lacking clear methodology, and non-peer-reviewed sources. Reference lists of selected articles were screened to identify additional relevant studies.

Data were organized by disease type (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, migraine) and mechanistic focus (inflammatory and immune pathways, microbial metabolites). EndNote 21 and Microsoft Excel 365 were used for literature management and data synthesis. This methodological framework enhances transparency, reproducibility, and scientific rigor consistent with narrative review standards.

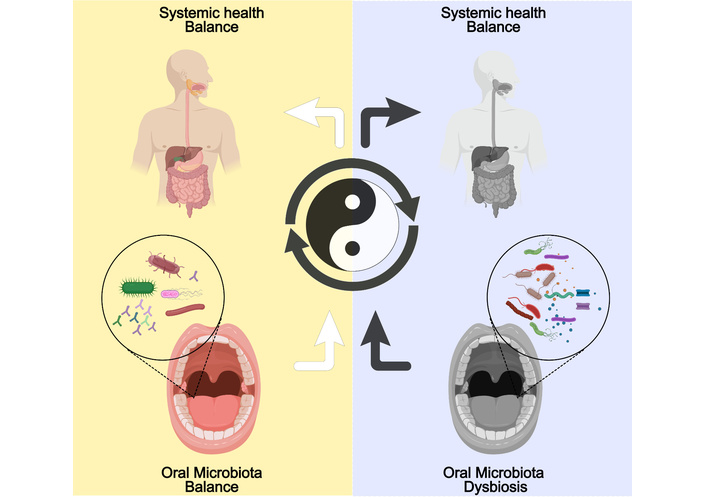

The oral microbiome is a complex ecosystem comprising a diverse array of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses, which inhabit various niches within the oral cavity. This microbial community is essential for maintaining oral health and plays a significant role in the overall well-being of the host (Figure 1). Among the microbial inhabitants, bacteria dominate the oral microbiome, with over 700 species identified to date. The primary bacterial genera include Streptococcus, Actinomyces, Veillonella, and Prevotella, which are integral to the oral environment. Streptococcus, particularly the Streptococcus mitis group, is often one of the first colonizers of the oral cavity, establishing a foundation for subsequent microbial communities [5]. Anaerobic bacteria, such as those from the genera Fusobacterium and Porphyromonas, thrive in the deeper layers of dental plaque and play crucial roles in periodontal disease and other oral health conditions. Additionally, the presence of Actinobacteria, including species of Actinomyces, contributes to the complex interplay of microbial interactions that can either promote health or lead to dysbiosis, a state linked with various diseases, including dental caries and periodontitis [6]. The composition of the oral microbiome is influenced by several factors, including diet, oral hygiene practices, and systemic health conditions, which can lead to significant variations in microbial diversity and abundance across individuals. Understanding the basic composition of the oral microbiome is vital for elucidating its role in health and disease, as well as for developing targeted interventions aimed at restoring microbial balance in dysbiotic states [7].

Oral microbiota balance and dysbiosis in health and disease. Created with MedPeer (medpeer.cn).

Recent research has highlighted significant alterations in the oral microbiota of patients suffering from neurological disorders, particularly AD and PD. In individuals diagnosed with AD, studies have demonstrated a marked decrease in the diversity of the oral microbiota, alongside an increased abundance of specific pathogens, notably P. gingivalis, a keystone pathogen associated with periodontal disease and systemic inflammation. This dysbiosis may contribute to the neuroinflammatory processes observed in AD, potentially exacerbating cognitive decline through mechanisms such as the systemic spread of inflammatory mediators and neurotoxic metabolites produced by pathogenic bacteria [8]. Furthermore, the relationship between oral health and neurological conditions is underscored by findings that suggest oral pathogens can infiltrate the central nervous system (CNS) via the bloodstream or cranial nerves, establishing a direct link between oral dysbiosis and neurodegenerative processes [9]. In contrast, patients with PD exhibit a distinct composition of oral microbiota when compared to healthy controls, characterized by a significant reduction in beneficial microbial taxa and an increase in pro-inflammatory bacteria. This shift is thought to be associated with heightened levels of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, which are known to contribute to the neurodegenerative pathways in PD [10]. Moreover, inflammatory markers have been shown to correlate with the abundance of specific microbial taxa in PD patients, such as Prevotella, Neisseria, and Fusobacterium, suggesting that the oral microbiota may play a role in modulating disease severity and progression [11]. Collectively, these findings indicate that alterations in the oral microbiota are not merely incidental but may actively participate in the pathophysiology of neurological disorders, highlighting the importance of maintaining oral health as a potential therapeutic strategy in managing these complex diseases.

In summary, the changes in the oral microbiota observed in both AD and PD underscore the intricate relationship between oral health and neurological function. The dysbiosis characterized by reduced microbial diversity and increased pathogenic bacteria may contribute to the inflammatory milieu associated with neurodegeneration. These insights not only enhance our understanding of the microbiota-gut-brain axis but also pave the way for novel therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring microbial balance as a means of mitigating the progression of neurological disorders. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific mechanisms through which oral microbiota influence neurodegenerative processes and exploring the potential for microbiota-targeted therapies, such as probiotics or dietary modifications, to improve outcomes for patients with these debilitating conditions.

To facilitate cross-disease comparison before the disease-specific sections, we summarize representative studies on oral microbiota in AD, PD, and migraine in Table 1 (Figure 2), highlighting sampling niches and methods, key microbial taxa, principal findings, and relevant clinical outcomes.

Summary of studies investigating the oral microbiota in neurological diseases.

| Disease | Study/Design | Oral niche and method | Key microbial taxa (↑/↓) | Main findings | Clinical outcomes/readouts | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Mixed (saliva, subgingival plaque); 16S or targeted PCR | ↑ Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, ↓ commensal streptococci | Oral dysbiosis is consistently associated with AD/MCI; it links to systemic inflammation and neuroinflammatory pathways | Worse cognitive performance; higher dementia risk signals | [12] |

| AD | Mechanism-oriented human/experimental evidence | Saliva/gingival sources; targeted detection of virulence factors | ↑ P. gingivalis; gingipains | P. gingivalis and virulence factors promote Aβ accumulation and impaired clearance; amplify neuroinflammation | Association with amyloid burden and AD pathology surrogates | [14] |

| AD | Clinical association studies | Periodontal status + oral microbiota; 16S | ↑ Periodontal pathogens; ↑ inflammatory signatures | Periodontitis/oral dysbiosis associated with ↑ Aβ and tau phosphorylation | Worse cognition; AD-related biomarker shifts | [15] |

| PD | Case-control/cross-sectional | Saliva; 16S rRNA gene profiling | Shift toward pro-inflammatory genera (e.g., Prevotella, Neisseria in selected cohorts), ↓ beneficial taxa | Distinct oral dysbiosis pattern in PD; correlations with systemic inflammation | Associations with motor symptom severity/progression markers | [24] |

| PD | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Mixed oral niches; 16S | ↓ α-diversity; compositional instability | Lower diversity and specific taxa changes correlate with PD severity | Links to motor decline; candidate oral biomarkers proposed | [25] |

| Migraine | Case-control | Saliva; 16S | Differential abundance across ~20+ genera; ↑ Veillonella, ↓ beneficial taxa (e.g., Faecalibacterium) | Distinct oral microbial signatures vs. controls; altered α/β diversity | Headache frequency/intensity associations in subgroups | [12, 29, 30] |

| Migraine | Multimodal biomarker study | Oral sampling + clinical phenotyping | Oral microbial “signatures.” | Oral dysbiosis proposed as an adjunctive biomarker for migraine stratification | Diagnostic/prognostic utility under evaluation | [34] |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; PD: Parkinson’s disease; Aβ: amyloid-beta; ↑/↓: microbial abundance increases/decreases.

The oral-gut-brain axis in neurological disorders. Created with MedPeer (medpeer.cn).

Acetate, propionate, and butyrate, primarily produced by microbial fermentation of dietary fibers, influence neuroimmune homeostasis [12, 13]. SCFAs activate G-protein-coupled receptors (FFAR2/GPR43, FFAR3/GPR41, GPR109A) on immune and endothelial cells, reducing systemic inflammation and supporting microglial homeostasis [14]. Butyrate, acting as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, enhances BBB integrity, supporting microglial maturation to a homeostatic state [15, 16]. These metabolites reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative damage, with concentration, receptor expression, and diet modulating their effects [17].

TMAO, produced by gut/oral microbiota from choline and carnitine, is linked to endothelial dysfunction and neuroinflammation. Elevated TMAO levels promote ROS generation, inflammasome activation, and microglial polarization towards a pro-inflammatory state [18–20]. These mechanisms contribute to BBB disruption and neuroinflammatory cascades. Though observational data suggest a link to cognitive decline, further research is needed to establish causal relationships.

LPS from oral pathogens such as P. gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum can translocate into the bloodstream during periodontal inflammation. LPS activates systemic inflammation through TLR4/CD14 signaling and Mfsd2a/Caveolin1 signaling, which compromises the BBB and induces neuroinflammation [21–24]. The periodontal-to-brain trafficking of LPS and other virulence factors links oral dysbiosis to CNS inflammation.

Periodontal pathogens such as P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum release various virulence factors, including LPS, gingipains, and peptidoglycans, which activate pattern-recognition receptors (TLR2/TLR4, NOD-like receptors) on gingival cells and immune cells [25, 26]. This triggers downstream signaling pathways, including NF-κB and MAPK activation, which induce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) and chemokines, amplifying local inflammation [26, 27]. These inflammatory signals can translocate to systemic circulation and influence the gut microbiota, contributing to neuroinflammation through the oral-gut-brain axis [2].

Cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α can disrupt the BBB, promoting increased permeability and facilitating the trafficking of immune cells into the brain [28]. Within the brain, these cytokines activate microglia, triggering a pro-inflammatory state and exacerbating neuroinflammation [29]. This oral-driven inflammation, via the oral-gut-brain axis, contributes to the pathogenesis of neurological disorders by enhancing oxidative stress, neuronal damage, and disruption of neurotrophic support.

Research indicates that dysbiosis of the oral microbiota has been associated with the pathogenesis of AD, likely through inflammatory responses. However, it is important to note that most studies suggest correlations rather than causal relationships. The oral cavity harbors a diverse microbial community, and an imbalance in this microbiota, termed dysbiosis, has been associated with various systemic diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders. A systematic review highlighted that specific oral pathogens, such as P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum, are consistently linked to AD and mild cognitive impairment, suggesting their potential role in neurodegeneration [30]. These pathogens can induce chronic inflammation, which is a critical factor in the development of AD. Inflammation in the oral cavity can lead to systemic inflammatory responses that may affect the CNS through several pathways, including the hematogenous route via the BBB. Dysbiosis in the oral microbiota may also exacerbate the inflammatory milieu, promoting neuroinflammation and neuronal damage, which are hallmarks of AD pathology [12]. But these mechanisms require further longitudinal and mechanistic studies to confirm causal pathways. It is also essential to consider that neurological diseases themselves might lead to poor oral hygiene, which in turn could exacerbate oral dysbiosis, creating a feedback loop that complicates the interpretation of causality in this context.

Moreover, the presence of oral pathogens has been shown to facilitate the deposition of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides, a key pathological feature of AD. Studies have demonstrated that P. gingivalis can directly influence the accumulation of Aβ in the brain by triggering inflammatory pathways that lead to increased production and reduced clearance of these neurotoxic peptides [31]. The interaction between oral bacteria and the host immune system can create a feedback loop where inflammation not only promotes dysbiosis but also enhances the neurodegenerative process. This is further supported by findings that individuals with periodontal disease, characterized by oral dysbiosis, exhibit higher levels of Aβ and tau phosphorylation, which are critical in the development of neurofibrillary tangles associated with AD [32].

The implications of these findings are profound, as they suggest that oral health may play a crucial role in the prevention and management of AD. Interventions aimed at restoring a balanced oral microbiota could potentially mitigate the inflammatory responses associated with dysbiosis, thereby reducing the risk or progression of AD. Oral health care strategies, including regular dental check-ups and the use of probiotics, may serve as preventive measures against cognitive decline [12]. Furthermore, understanding the complex relationship between oral microbiota and neuroinflammation could lead to novel therapeutic approaches targeting the microbiota-gut-brain axis to improve cognitive health in aging populations. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific mechanisms by which oral dysbiosis contributes to neurodegeneration and exploring the potential of microbiota modulation as a therapeutic strategy in AD [33].

The oral microbiota plays a significant role in influencing neuroinflammation and metabolic pathways through the oral-gut-brain axis. This axis refers to the complex network of communication between the oral cavity, gut, and brain, with interactions that can affect neurological health. However, it is crucial to note that the direct neuroprotective effects of SCFAs, which are primarily produced by gut microbiota through the fermentation of dietary fibers, are often confused with the influence of oral microbiota. Dysbiosis in the oral cavity may contribute to the translocation of pathogenic bacteria and their metabolites into systemic circulation, which may trigger inflammatory responses in the CNS [34]. For instance, periodontal pathogens such as P. gingivalis have been identified in the brains of AD patients, suggesting a direct link between oral health and neurodegenerative conditions [35]. The inflammatory cytokines released during periodontal disease can cross the BBB, exacerbating neuroinflammation and contributing to cognitive decline. Furthermore, the gut microbiota, influenced by oral health, can modulate the immune response and alter neurotransmitter levels, thereby impacting brain function and behavior [36]. This intricate relationship underscores the importance of maintaining oral health to mitigate neuroinflammatory processes that may lead to or worsen neurological disorders.

Additionally, the metabolic byproducts of oral microbiota can affect neuronal function by crossing the BBB. For example, SCFAs produced by the fermentation of dietary fibers by gut microbiota, have been shown to possess neuroprotective properties and can influence the expression of genes involved in neuroinflammation [37]. These metabolites can enhance the integrity of the BBB and modulate neuroinflammatory pathways, thus playing a crucial role in maintaining cognitive health [38]. Moreover, oral bacteria can produce neurotransmitters such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and serotonin, which are vital for regulating mood and cognitive functions [39]. Dysbiosis in the oral microbiota can disrupt the production of these neurotransmitters, potentially leading to mood disorders and cognitive decline [40]. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms by which oral microbiota influence neuroinflammation and neuronal function is essential for developing therapeutic strategies aimed at preventing or treating neurodegenerative diseases. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific pathways and interactions involved in the oral-gut-brain axis to identify potential biomarkers and intervention points for clinical applications.

The oral microbiome of patients with PD exhibits significant compositional changes, including an increase in certain pathogenic bacteria. While these changes have been associated with the disease progression, it is important to highlight that most evidence indicates a correlation rather than a direct causal role in neurodegeneration. Research has shown that individuals with PD often present with a specific dysbiosis in their oral microbiota, which may contribute to the disease’s progression and severity. For instance, studies have identified a notable increase in bacteria such as Prevotella and Neisseria in the saliva of PD patients compared to healthy controls, indicating a shift towards a more pathogenic microbial profile [41]. The alteration in the oral microbiome may be linked to systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation, but more longitudinal and mechanistic studies are needed to clarify the nature of these relationships. Furthermore, it is critical to acknowledge the possibility that PD-related factors, such as impaired motor function or medication use, could contribute to oral hygiene issues, which in turn might worsen oral dysbiosis [25].

Recent studies have also highlighted the relationship between oral microbiome dysbiosis and the decline in motor functions among PD patients. For example, a systematic review indicated that the diversity of oral microbiota is significantly lower in individuals with PD, which correlates with the severity of motor symptoms [42]. This suggests that a healthy and diverse oral microbiome may play a protective role against the deterioration of motor functions. The mechanisms behind this association could involve the modulation of systemic inflammation and the maintenance of the BBB integrity by the oral microbiome. Dysbiosis may lead to increased permeability of the BBB, allowing neurotoxic substances and inflammatory mediators to enter the CNS, thereby exacerbating neurodegenerative processes [43].

Moreover, the impact of lifestyle factors on the oral microbiome composition in PD patients cannot be overlooked. Factors such as diet, oral hygiene, and medication can significantly influence the microbial balance in the oral cavity [44]. For instance, the consumption of a diet high in sugars and carbohydrates has been associated with an increase in pathogenic bacteria and a decrease in beneficial species, further contributing to dysbiosis [45]. Additionally, the use of certain medications, including antibiotics, can disrupt the microbial balance, leading to a decline in oral health and potentially worsening PD symptoms.

In conclusion, the specific changes in the oral microbiome composition observed in PD patients highlight the intricate relationship between oral health and neurological function. The increase in pathogenic bacteria and the decrease in microbial diversity are not only indicative of oral dysbiosis but may also reflect underlying neuroinflammatory processes that contribute to the progression of PD. Future research should focus on exploring the therapeutic potential of modulating the oral microbiome as a strategy to improve clinical outcomes in PD patients, potentially through dietary interventions, probiotics, or other microbiome-targeted therapies. Understanding these dynamics may pave the way for novel approaches to manage and mitigate the effects of PD on motor function and overall health.

The oral microbiota is increasingly recognized for its potential role in exacerbating neuronal damage through pro-inflammatory pathways. Dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance in the oral cavity, can lead to the overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, such as P. gingivalis, which is associated with periodontal disease. These pathogens can release virulence factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to systemic inflammation. For instance, periodontal pathogens can translocate into the bloodstream, triggering an immune response that affects distant organs, including the brain. This inflammatory response is particularly concerning in neurodegenerative diseases, where chronic inflammation may exacerbate neuronal injury and cognitive decline. Research has shown that the presence of oral bacteria in the CNS correlates with increased neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, suggesting a direct link between oral health and neurological conditions such as AD and PD [8, 36]. Furthermore, studies indicate that oral bacteria can influence the production of inflammatory mediators, which may further contribute to neuronal damage. For example, the activation of microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain, can be triggered by systemic inflammation originating from oral pathogens, leading to a cascade of neuroinflammatory processes that impair neuronal function and survival [37, 39]. The interplay between oral microbiota and neuroinflammation underscores the importance of maintaining oral health as a potential strategy for mitigating neurodegenerative disease progression.

Additionally, the metabolic byproducts of oral microbiota may significantly influence dopamine synthesis and metabolism, further linking oral health to neurological outcomes. The oral microbiome produces various metabolites, including SCFAs and neurotransmitter precursors, which can have profound effects on brain function. For instance, certain bacterial species in the oral cavity are capable of producing metabolites that can cross the BBB and modulate neurotransmitter systems, including dopamine pathways. Dysbiosis may alter the balance of these metabolites, potentially leading to dysregulation of dopamine synthesis and metabolism. This dysregulation has been implicated in various psychiatric and neurological disorders, including depression and schizophrenia, where dopamine signaling is critically involved [34]. Moreover, the oral microbiota can influence the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication pathway between the gut and the CNS, which is essential for maintaining neurological health. The metabolites produced by oral bacteria can affect gut microbiota composition, which in turn can influence brain function and behavior through neuroendocrine and immune pathways [38, 40]. Thus, the relationship between oral microbiota, their metabolic products, and neurological health is complex and multifaceted, highlighting the need for further research to elucidate these mechanisms and their clinical implications. Understanding these interactions may pave the way for novel therapeutic strategies targeting the oral microbiome to improve neurological outcomes and overall brain health.

Research has increasingly focused on the relationship between oral microbiota and migraine, revealing significant differences in the microbiota composition of migraine patients compared to healthy individuals. A study utilizing 16S rRNA gene sequencing found that migraine patients exhibited distinct microbial communities characterized by altered alpha and beta diversity indices. Specifically, the alpha diversity, which reflects the richness of microbial species, was found to be higher in migraine patients than in controls, suggesting a more complex microbial environment [46]. Furthermore, the study identified 23 genera that were differentially abundant between the two groups, highlighting specific microbial taxa that may play a role in migraine pathophysiology. For instance, genera such as Veillonella were found to be more abundant in migraine patients, while beneficial taxa like Faecalibacterium were reduced [47]. These findings suggest that particular shifts in microbial composition may be linked to the frequency and intensity of migraine attacks. Additionally, another study indicated that the abundance of certain genera, such as Lachnospiraceae, was associated with lower headache frequency, implying a potential protective role against migraine [48]. The dysbiosis observed in migraine patients may contribute to the inflammatory processes that are thought to underlie migraine attacks, as alterations in gut microbiota can influence systemic inflammation and neuroinflammatory pathways [49]. Overall, these studies suggest that the oral microbiota not only differs significantly in migraine patients but may also correlate with clinical features of the condition, indicating a complex interplay between microbial health and migraine susceptibility. However, it is essential to emphasize that these differences are only correlational, and further research, particularly longitudinal studies, is needed to distinguish whether dysbiosis is a consequence of migraine or a contributor to its development. The association between microbial shifts and migraine characteristics, such as frequency and intensity, suggests a complex interplay, but direct causal mechanisms are not yet well-established. Future research should aim to elucidate the mechanisms by which these microbial changes impact migraine pathophysiology and explore the potential for microbiota-targeted therapies in managing this prevalent condition.

The relationship between oral microbiota and neurological disorders, particularly migraine, is an emerging area of research that highlights the potential mechanisms through which oral bacteria may influence the pathophysiology of this debilitating condition. Recent studies suggest that oral microbiota can affect the production of neurotransmitters and modulate inflammatory responses, both of which are critical in the context of migraine. For instance, dysbiosis of the oral microbiome has been associated with increased systemic inflammation, which can exacerbate migraine attacks [50]. Oral pathogens, such as P. gingivalis, have been implicated in the inflammatory response, potentially leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that may trigger or worsen migraine episodes [50]. Furthermore, alterations in the composition of the oral microbiota can influence the gut-brain axis, thereby impacting CNS functions and contributing to the pathogenesis of migraines [40]. The interplay between the oral microbiome and the neurological pathways involved in migraine suggests that oral health may play a critical role in the management and prevention of this condition.

In addition to the potential pathophysiological mechanisms, probiotic interventions represent a promising avenue for migraine treatment. Probiotics, which are live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host, have been shown to restore microbial balance in the gut and oral cavity, potentially alleviating migraine symptoms [50]. The administration of specific probiotic strains may enhance the production of beneficial metabolites and neurotransmitters, such as GABA and serotonin, which are known to play roles in mood regulation and pain perception. Moreover, probiotics can exert anti-inflammatory effects, thereby reducing the systemic inflammation associated with migraine attacks [51]. Recent clinical trials have indicated that probiotic supplementation may lead to a reduction in the frequency and severity of migraine episodes, suggesting that targeting the oral microbiota could be an effective strategy for migraine management [52]. This emerging evidence underscores the need for further research into the specific strains of probiotics that may be most beneficial for individuals suffering from migraines, as well as the underlying mechanisms that facilitate these effects. Overall, the connection between oral microbiota, neurotransmitter modulation, and inflammatory responses presents a compelling framework for understanding the complex interplay between oral health and neurological disorders, particularly migraine.

Probiotics have emerged as a promising therapeutic approach for modulating the oral microbiota, potentially alleviating symptoms associated with various neurological disorders. The oral microbiome plays a crucial role in maintaining systemic health, and its dysbiosis has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several neurological conditions, including AD, PD, and even conditions like migraine and stroke [53]. Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts, can help restore the balance of the oral microbiota. This can lead to improvements in both oral health and overall neurological well-being, potentially alleviating symptoms of these neurological conditions.

This bidirectional communication is believed to influence neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter production, and overall brain health [54–57]. Clinical trials exploring the efficacy of probiotics in neurological disorders are gaining traction, demonstrating varying degrees of success. For instance, studies have shown that specific probiotic strains, such as Bifidobacterium breve, can protect dopaminergic neurons and reduce neuroinflammation in preclinical models of PD [27]. Furthermore, the administration of probiotics has been associated with improved cognitive function and reduced symptoms in patients with AD, suggesting that these interventions may modulate neuroimmune pathways critical for disease progression.

In addition to cognitive benefits, research has shown that oral probiotics can impact other neurological aspects such as mood and motor function [58]. Furthermore, the stability and viability of probiotics during gastrointestinal transit pose additional challenges for effective delivery [59]. These studies will help clarify the role of probiotics in modulating the oral and gut microbiota, potentially leading to innovative strategies for the prevention and treatment of neurological disorders. Overall, the integration of probiotics into therapeutic protocols for neurological diseases represents a significant advancement in our understanding of the gut-brain axis and highlights the importance of microbiota in maintaining neurological health [60].

Localized therapeutic strategies targeting oral dysbiosis are also being explored as potential interventions for neurological diseases. These treatments focus on directly restoring a healthy oral microbiome by addressing factors such as oral hygiene, diet, and the use of oral probiotics or antimicrobial agents. Regular dental check-ups, professional cleanings, and the use of oral rinses containing probiotics or antimicrobial agents could help reduce the burden of pathogenic bacteria in the oral cavity, thereby preventing the translocation of oral pathogens and their inflammatory byproducts to the CNS.

For instance, mouthwashes containing probiotics such as Lactobacillus strains or Bifidobacterium may help rebalance the oral microbiota, reducing the levels of harmful periodontal pathogens like P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum. These interventions could not only improve oral health but also reduce neuroinflammation associated with oral dysbiosis, providing a novel approach to mitigate the progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and PD.

Localized treatments such as these may offer an effective and non-invasive means to modulate the oral microbiota in the early stages of neurological diseases, preventing further damage and improving patient outcomes. Future clinical trials will be essential to evaluate the efficacy and safety of these strategies, as well as to establish clear protocols for their use in clinical practice.

The exploration of the oral microbiome’s role in neurological disorders represents a burgeoning field of research that holds significant promise for understanding and potentially mitigating conditions such as AD, PD, and migraines. This review has highlighted the intricate mechanisms through which oral microbiota may influence neurodegenerative processes and neurological health, suggesting that these microorganisms could serve as novel therapeutic targets. While several recent reviews have explored oral dysbiosis in individual neurological conditions, this review distinguishes itself by integrating research across multiple diseases, providing a more holistic view of the potential role of the oral microbiome in various neurodegenerative diseases. Additionally, we critically examine the existing literature to highlight gaps and underexplored areas, such as the cross-condition microbial signatures that could inform early diagnostics.

As we delve deeper into the interplay between the oral microbiome and the CNS, it becomes increasingly clear that a multifaceted approach is necessary to balance the diverse research perspectives and findings in this domain. The complexity of the microbiome itself, with its vast array of microbial species and their interactions, necessitates a comprehensive understanding of how these organisms can affect neurological health. For instance, the pathways through which oral bacteria may contribute to neuroinflammation or the production of neurotoxic metabolites are still being elucidated. While current studies predominantly focus on one disease at a time, our review proposes that a comparative approach across diseases may yield valuable insights into shared microbiome characteristics that influence disease progression.

Moreover, the implications of these findings extend beyond mere academic interest; they present a paradigm shift in how we approach the prevention and treatment of neurological diseases. The potential for oral microbiome modulation—whether through probiotics, dietary interventions, or other therapeutic means—opens up new avenues for intervention that could complement existing treatment strategies. However, translating these insights into clinical practice remains challenging. Rigorous clinical trials will be essential to validate the efficacy and safety of such interventions, ensuring that they can be integrated into standard care protocols. We also highlight how emerging studies on early diagnostic tools, particularly those based on salivary microbiome profiling, could significantly advance our ability to detect neurological diseases at their onset.

Future research must also address the methodological challenges inherent in studying the microbiome. The variability in individual microbiomes, influenced by factors such as genetics, diet, and environmental exposures, complicates the establishment of definitive causal relationships. Large-scale, longitudinal studies are needed to capture these dynamics over time and to identify specific microbial signatures associated with various neurological conditions. Additionally, multidisciplinary collaboration among microbiologists, neurologists, and epidemiologists will be crucial to foster a holistic understanding of the microbiome’s role in neurological health. Future research should particularly focus on elucidating microbial biomarkers that could be used for early detection, especially in high-risk populations.

As we look ahead, it is imperative that we remain cautious yet optimistic about the potential of the oral microbiome as a therapeutic target. The balance between enthusiasm for new findings and the rigor of scientific validation must be maintained. While the prospect of manipulating the microbiome to enhance neurological health is enticing, it is essential to ground our expectations in evidence-based research.

In conclusion, the oral microbiome represents a promising frontier in the study of neurological disorders. As research progresses, it is vital to continue exploring the complex relationships between microbial communities and neurological health, while also developing effective intervention strategies. By embracing a balanced perspective that integrates diverse research findings, we can pave the way for innovative approaches to the prevention and treatment of neurological diseases, ultimately improving patient outcomes and enhancing our understanding of the human body’s intricate systems. Furthermore, the integration of early diagnostic tools based on microbiome profiling holds great potential for advancing clinical practice in neurology.

The oral microbiome plays a pivotal role in the onset and progression of neurological disorders, including AD, PD, and migraine. Dysbiosis in oral microbial communities has been associated with systemic inflammation, BBB disruption, and neuroinflammatory cascades that contribute to cognitive and motor decline. Specific pathogens, such as P. gingivalis, have been directly implicated in amyloid deposition and neurodegeneration, while broader microbial shifts correlate with symptom severity and disease progression. Mechanistically, the oral-gut-brain axis provides a framework to explain how microbial metabolites, immune responses, and neurotransmitter modulation influence brain health. These insights underscore the importance of oral health as both a diagnostic indicator and a modifiable risk factor for neurological conditions. Emerging therapeutic strategies, including probiotics, dietary modulation, and fecal microbiota transplantation, show promise in restoring microbial balance and alleviating neurological symptoms. However, variability in microbial composition, host response, and treatment protocols highlights the need for standardized, large-scale clinical trials. In conclusion, advancing our understanding of the oral microbiome offers a novel avenue for the prevention and management of neurological diseases. By integrating microbiome research into clinical practice, it may be possible to improve diagnostic precision and develop innovative therapeutic strategies.

AD: Alzheimer’s disease

Aβ: amyloid-beta

BBB: blood-brain barrier

CNS: central nervous system

GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid

LPS: lipopolysaccharide

PD: Parkinson’s disease

SCFAs: short-chain fatty acids

ZL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. YS: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft. J Liu: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. J Li: Validation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1296

Download: 23

Times Cited: 0

Adnan Akhtar Shaikh ... Niveditha Nair

Salomón Páez-García ... Miguel Germán Borda