Affiliation:

1Department of Biochemistry, Federal University of Technology, Akure 340252, Nigeria

Email: agunloye.odunayo9@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8835-0472

Affiliation:

1Department of Biochemistry, Federal University of Technology, Akure 340252, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0262-6256

Affiliation:

2Department of Physiology, Federal University of Technology, Akure 340252, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-9337-7610

Affiliation:

2Department of Physiology, Federal University of Technology, Akure 340252, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-0671-0159

Affiliation:

1Department of Biochemistry, Federal University of Technology, Akure 340252, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5167-9779

Explor Neurosci. 2026;5:1006123 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/en.2026.1006123

Received: June 30, 2025 Accepted: January 05, 2026 Published: February 01, 2026

Academic Editor: Marcello Iriti, Milan State University, Italy

The article belongs to the special issue Medicinal Plants and Bioactive Phytochemicals in Neuroprotection (Vol II)

Aim: Male infertility resulting from neurological disorders, oxidative stress, and hormonal imbalance is a growing health concern. This study, therefore, investigated the effects of Aframomum melegueta and Aframomum danielli-supplemented diets on sperm quality and testicular oxidative damage in a scopolamine-induced rat model.

Methods: Adult male rats were randomly allocated into seven groups: normal group; scopolamine-induced group; donepezil-treated scopolamine group and four treatment groups receiving 4% or 8% dietary supplementation of Aframomum melegueta or Aframomum danielli, respectively. Sperm motility, count, and morphology were evaluated. In addition, serum testosterone and follicle stimulating hormone levels, testicular oxidative stress markers, inflammatory cytokines, and antioxidant activities were assessed to determine reproductive and biochemical responses. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) profiling was also conducted to identify the major phenolic compounds in both seeds.

Results: Scopolamine administration impaired sperm quality, decreased hormonal levels, promoted oxidative stress, and altered inflammatory responses. These alterations were, however, reversed by diets supplemented with Aframomum melegueta and Aframomum danielli in a dose-dependent manner. The 8% supplementation produced better outcomes than 4% supplementation and donepezil treatment in most parameters, indicating protective effects on sperm quality and other reproduction-related indices. HPLC profiling revealed bioactive compounds that may collectively account for the observed restorative effects of the seeds.

Conclusions: These findings demonstrate that Aframomum melegueta and Aframomum danielli seeds effectively reversed the adverse reproductive alterations caused by scopolamine-induced neurotoxicity. Both species significantly improved sperm quality and testicular function, which may suggest their possible development as plant-based nutraceuticals for protecting male reproductive health in future studies. Their phytochemical abundance further supports their potential as plant-based nutraceuticals.

A recent and growing subject of health concern globally is the problem of male infertility, a condition caused by sexual and reproductive impairments, and associated with psychological and emotional distress in families [1]. Shifting the focus from the female gender, recent studies show a rising trend in male infertility since 1990, accounting for up to 50% infertility cases among couples [2]. In a well-functioning body, neurological mechanisms are fundamental for maintaining sexual and reproductive functions, and any disruption to these mechanisms can result in reproductive problems leading to infertility [3, 4]. Underlying neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease have been associated with the onset of semen abnormalities, testosterone deficiency, and impaired ejaculation [5–9]. Furthermore, cognitive outcomes such as dementia and depression further compromise male reproductive health [10, 11].

Management of neurological disorders often requires the continuous use of antidepressants, particularly serotonin reuptake inhibitors (selective) and other monoamine reuptake inhibitors (non-selective), which have been associated with decreased testosterone concentrations and impaired sperm concentration, morphology, and motility despite their therapeutic advantages [12–15]. Experimental models of neurotoxicity, such as scopolamine administration, which mimics cholinergic dysfunction and oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s disease, have been linked with adverse effects on sexual and reproductive functions in male rats [16, 17], largely due to reduced spermatogenic activity and oxidative testicular damage [18, 19]. Although drugs like donepezil can attenuate cognitive symptoms, their effect on related infertility may be limited, and side effects, including hepatotoxicity, insomnia, anorexia, weight loss, and vomiting, restrict their safety [20–22]. These challenges highlight the need for safer, natural alternatives that have neuroprotective and reproductive benefits.

Aframomum melegueta (AFM) and Aframomum danielli (AFD) seeds are two plant species commonly used as spices, native to West Africa and belonging to the Zingiberaceae family. As medicinal plants, they have been used traditionally and validated scientifically for their neuroprotective [23], antioxidants [24], anti-inflammatory [25], and aphrodisiac [26] properties. Phytochemical investigations reveal that AFM and AFD seeds contain bioactive compounds such as alkaloids, flavonoids (quercetin, naringenin, kaempferol), phenolic compounds (ferulic acid, caffeic acid), terpenoids (β-caryophyllene), and gingerol (6-gingerol, paradol, shogaol), which have demonstrated antioxidants and fertility-enhancing capacities [27, 28]. These compounds are known to improve sperm quality, enhance testosterone levels, and protect testicular tissue from oxidative stress [29].

Despite the well-documented antioxidant and aphrodisiac effects of AFM and AFD, there remain limited studies on their potential to mitigate male infertility associated with neurological disorders or neurotoxic exposure. This study therefore sought to evaluate the protective effects of AFM- and AFD-supplemented diets on sperm quality; testosterone and gonadotropin concentrations, and testicular antioxidant status in scopolamine-administered male rats. We hypothesized that dietary supplementation with AFM and AFD seeds would mitigate scopolamine-induced (SID) reproductive impairments in this rat model through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

AFM and AFD seeds were manually removed from their pods, rinsed, air-dried at room temperature, and ground into a fine powder. Dietary formulations were prepared by incorporating 4% and 8% AFM or AFD powders into diets containing skimmed milk powder, corn starch, dietary oil, and nutrient premix. The 4% and 8% inclusion levels were selected as safe supplementation levels, consistent with previous studies that reported no adverse effects following dietary incorporation of Aframomum species in animal diets within the range of 1.5–15 g [30–33]. Diet supplementation is shown in Table 1 according to Agunloye and Oboh [34]. The diet recipes were thoroughly mixed using automated mixer to ensure an even mixture. Thereafter, the mixture was pelleted, dried and stored.

Formulation of diets given to experimental rats in each group per 100 g.

| Treatment (g) | Group 1Basal diet | Group 2Scopolamine | Group 3Donepezil | Group 44% AFM | Group 58% AFM | Group 64% AFD | Group 78% AFD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skim milk | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| Oil | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Premix | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Corn starch | 58 | 58 | 58 | 54 | 50 | 54 | 50 |

| AFM | - | - | - | 4 | 8 | - | - |

| AFD | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 8 |

AFM: Aframomum melegueta; AFD: Aframomum danielli.

Adult male Wistar rats (190–200 g) were obtained and housed under baseline laboratory conditions, including a fixed 12-hour light/dark cycle, an environmental temperature of 22 ± 2°C, and continuous access to food and water. Ethical clearance (Approval number FUTA/23/027) was granted by the Institutional Committee for Animal Welfare and Use, and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011).

Group 1: Normal rats; received basal diet only, no scopolamine.

Group 2: SID rats; received 3 mg/kg body weight (BW) of scopolamine.

Group 3: SID + donepezil rats; received 5 mg/kg BW donepezil and scopolamine.

Group 4: SID + AFM (4%) rats; received 4% AFM supplemented diet and scopolamine.

Group 5: SID + AFM (8%) rats; received 8% AFM supplemented diet and scopolamine.

Group 6: SID + AFD (4%) rats; received 4% AFD supplemented diet and scopolamine.

Group 7: SID + AFD (8%) rats; received 8% AFD supplemented diet and scopolamine.

The experiment lasted for 14 days. Using a computerized number generator, animals were assigned randomly into groups (four animals per group) and received dietary supplementation consecutively for the 14-day experimental period. Groups 4–7 were pre-treated with diets supplemented with AFM or AFD at 4% and 8% inclusion, respectively. To avoid confounding factors, diet intake was monitored daily and normalized to BW and no significant differences were observed during the experimental period (see Table S1), ensuring consistent and complete consumption of the supplemented diets.

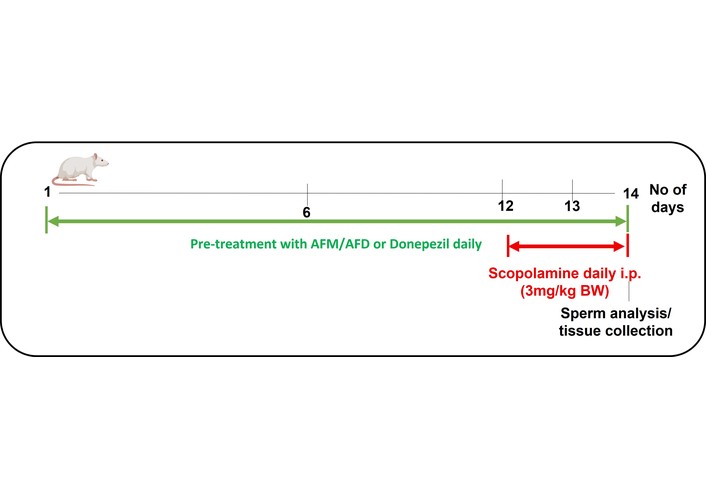

Donepezil, which was utilized as the positive reference, was orally administered at 5 mg/kg BW once daily, while scopolamine was administered intraperitoneally at 3 mg/kg BW once daily at the same time each day (~ 09:00 h) on the last 3 days of the experiment. The application of scopolamine followed the methodologies of Akomolafe et al. [16] and Agunloye et al. [17]. See Figure 1 below for the experimental timeline.

Experimental timeline for dietary supplementation, scopolamine administration and tissue collection. Green bar: AFM/AFD supplemented diets or donepezil for 14 days. Red bar: scopolamine injections (day 12–14, i.p., 9:00 h after diet). AFM: Aframomum melegueta; AFD: Aframomum danielli.

The rats were decapitated via cervical dislocation by trained personnel, after which the left testis tissue of each rat was immediately isolated, minced with scissors, and homogenized in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4). Centrifugation of the homogenates was carried out for 10 min at 12,000 × g, and the supernatant fraction was used for subsequent biochemical analysis [16].

All outcome assessments, including sperm concentration and other quality analyses, were performed by investigators who were blinded to the treatment groups. The groups were masked using letter codes (A–G) to minimize potential bias. Spectrophotometric readings were obtained using a visible spectrophotometer (V-5000 model, manufactured by A & E Lab UK CO., LTD).

The caudal epididymis collected was minced in normal saline, and the epididymal sperm were pipetted on a pre-sterilized microscopic slide. Sperm concentration was determined using a Neubauer counting chamber (hemocytometer), as described by Yokoi et al. [35]. Sperm mobility and morphology were evaluated using the method described by Nwanna et al. [36]. Progressive motility was classified into fast, slow, and non-motile sperm, and expressed as a percentage of total sperm observed. Morphology was categorized based on the percentage of sperm cells with normal morphology (NM) and those with abnormalities, further grouped into head defects (HD), neck defects (ND), and tail defects (TD). The percentage of fast motility and NM was prioritized for better comparative analysis and graphical representation.

The concentration of testosterone and FSH in the serum homogenate of experimental rats was determined following the instructions outlined in the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit manufacturer’s manual (Elabscience Biotechnology Inc., Texas, USA).

The levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) produced in the testis homogenate were measured as described by Ohkawa et al. [37]. To 0.15 mL homogenate, 0.15 mL of 8.1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulphate, 0.25 mL of acetic acid/HCl and 0.25 mL of 0.6 % thiobarbituric acid were added. Mixture incubation was done at 100°C for 1 h, after which the absorbance of MDA produced was spectrophotometrically measured at 532 nm and expressed as mmol of MDA/mg protein.

ROS generation was estimated and expressed as equivalents of H2O2 as described by Oboh et al. [38]. The reacting medium includes 0.1 mL N-N-diethyl-para-phenylenediamine reagent, and 0.14 mL of pH 4.84 acetate buffer, which was added to the 0.01 mL aliquot tissue homogenate. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes, and absorbance was taken at 505 nm.

Serum concentrations of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) were quantified according to instructions provided in the ELISA kit manufacturer’s manual (Elabscience Biotechnology Inc., Texas, USA). Colour intensity, indicative of cytokine concentrations, was measured spectrophotometrically with a microplate-ELISA reader.

TSH levels and NSH levels were determined following the method of Ellman [39]. For TSH measurement, reaction mixtures containing testis tissue homogenate and Ellman’s reagent were incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes, and absorbance was read at 412 nm. For NSH measurement, tissue homogenate was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and subsequently centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to obtain a clear protein-free supernatant read at 412 nm, after addition of Ellman’s reagent and further incubation at 37°C.

The activity of SOD was measured as outlined by Misra and Fridovich [40]. Tissue homogenates (0.1 mL) were resuspended in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. An aliquot of the prepared tissue homogenate (0.05 mL) was introduced to 1 mL of (pH 10.2, 0.05 M) carbonate buffer to equilibrate in a cuvette, and the reaction was measured at 480 nm at 30-second intervals for 3 minutes after the addition of 0.017 mL of adrenaline.

The activity of CAT in the testis homogenate was evaluated by the method reported by Oboh et al. [38] and Sinha [41]. Typically, 0.05 mL of tissue homogenate was incubated with 0.2 mL of 0.2 M H2O2 and 0.5 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Potassium dichromate-glacial acetic acid (1:3; 1 mL) was added at the point of absorbance reading for 3 minutes at 1 minute intervals with a wavelength of 620 nm. CAT activity was quantified as the amount of H2O2 degraded per minute per mg of protein.

Phenolic compounds in the empirical samples were identified and quantified using HPLC coupled with a DAD (Shimadzu). The dried samples (10 g) were extracted with 20 mL of a 1:1 acetonitrile/methanol solution, shaken vigorously for 30 min, and the organic extracts were collected into 25 mL standard flasks after separation of the aqueous fraction using methyl acetate. Standard solutions of the target phenolics were first injected into the HPLC to generate retention times and peak areas. Subsequently, a 10 μL aliquot of the extracted test sample was injected at a 1 mL/min flow rate to obtain corresponding chromatographic peak areas and retention times of the phenolic contents.

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.1. Replicate results were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Group differences and comparisons were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test, and a significant difference was considered at P < 0.05.

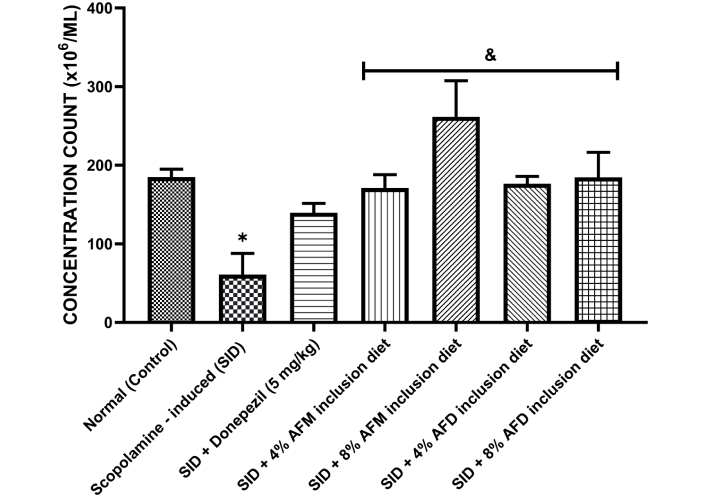

Figure 2 shows the effect of scopolamine and dietary treatments on sperm concentration in male rats. The untreated SID group exhibited a significant reduction in sperm concentration (53.0 ± 5.56 × 106/mL) compared to the control group (185.80 ± 4.52 × 106/mL, P < 0.05). Treatment with donepezil (126.30 ± 4.69 × 106/mL) showed a modest, non-significant increase in sperm concentration relative to the SID group. In contrast, dietary supplementation with 4% AFM (165.0 ± 5.48 × 106/mL), 8% AFM (285.3 ± 7.41 × 106/mL), 4% AFD (177.8 ± 4.03 × 106/mL), and 8% AFD (184.5 ± 6.48 × 106/mL) significantly improved sperm concentration compared to the SID group (P < 0.05). Post-hoc analysis showed that all dietary treatment groups achieved significantly (P < 0.05) higher sperm concentrations than the donepezil group, with 8% AFM producing the highest recovery.

Effect of AFM and AFD seeds dietary inclusion on sperm concentration count in SID male rats. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of replicate determinations (n = 4). Significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. normal (control); & P < 0.05 vs. SID rats. AFM: Aframomum melegueta; AFD: Aframomum danielli; SID: scopolamine-induced.

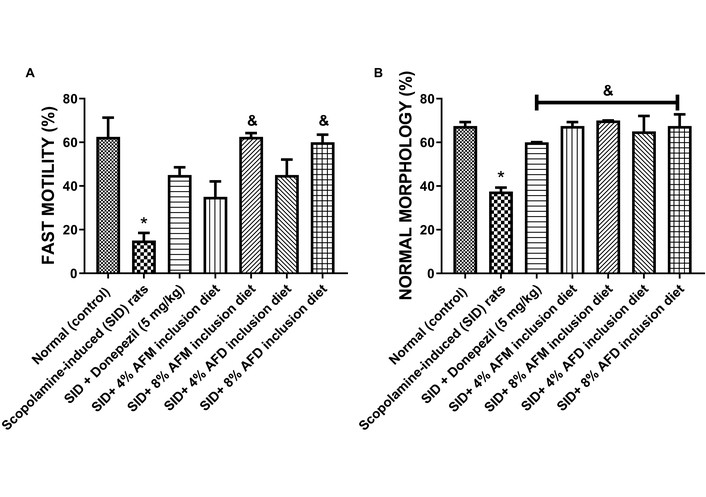

Figure 3 presents sperm quality parameters for fast motility (A) and NM (B) across the experimental groups. Untreated SID rats exhibited significantly (P < 0.05) reduced fast motility (15.00 ± 4.95%) and NM (37.50 ± 2.50%) compared to the normal control (62.50 ± 12.50% and 67.50 ± 2.53%, respectively). Donepezil treatment produced slight but non-significant improvements in fast mobility (45.00 ± 5.01%) compared with the SID group. However, treatment with AFM and AFD significantly (P < 0.05) improved both sperm quality parameters in a concentration-dependent manner. The 8% AFM (62.50 ± 2.47%) and 8% AFD (60.00 ± 4.95%) treated groups showed the greatest improvement in morphology, with values ranging from 67.50% to 70.00%. Detailed data are presented in Table S2.

Effects of AFM and AFD seed dietary inclusion on (A) sperm progressive fast motility and (B) normal morphology in the epididymis of SID male rats. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of replicate determinations (n = 4). Significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. normal (control); & P < 0.05 vs. SID rats. AFM: Aframomum melegueta; AFD: Aframomum danielli; SID: scopolamine-induced.

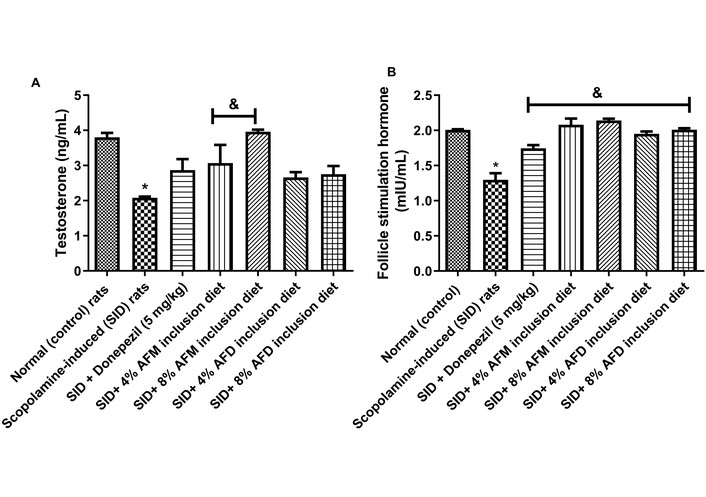

Figure 4 depicts the impact of AFM- and AFD-supplemented diets on serum (A) testosterone and (B) FSH concentrations in experimental rats. Testosterone level in the untreated SID rats (2.08 ± 0.05 ng/mL) was significantly (P < 0.05) lower than that in the normal control group (3.80 ± 0.18 ng/mL). Pre-treatment with donepezil (2.87 ± 0.44 ng/mL) resulted in a mild but statistically non-significant improvement compared with the SID rats, while 4% AFM (3.07 ± 0.55 ng/mL) and 8% AFM (3.96 ± 0.12 ng/mL) supplemented diets significantly (P < 0.05) elevated testosterone levels. Meanwhile, 4% AFD (2.66 ± 0.30 ng/mL) and 8% AFD (2.75 ± 0.47 ng/mL) produced an apparent increase in testosterone levels, although these changes were not statistically significant relative to the SID group. Among the treatment groups, 8% AFM produced the highest testosterone levels, exceeding both 8% AFD and 4% AFM.

Effects of AFM and AFD seed dietary inclusion on testosterone and FSH concentrations in the serum of SID male rats. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of replicate determinations (n = 4). Significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. normal (control); & P < 0.05 vs. SID rats. AFM: Aframomum melegueta; AFD: Aframomum danielli; SID: scopolamine-induced; FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone.

For FSH, the untreated SID rats (1.30 ± 0.13 mIU/mL) showed significantly (P < 0.05) lower levels than the normal control group (2.00 ± 0.02 mIU/mL). Administration of donepezil (1.74 ± 0.07 mIU/mL), 4% AFM (2.08 ± 0.14 mIU/mL), 8% AFM (2.14 ± 0.03 mIU/mL), 4% AFD (1.95 ± 0.08 mIU/mL), and 8% AFD (2.00 ± 0.02 mIU/mL) significantly restored FSH levels relative to the SID rats. Comparisons of AFM and AFD treated groups with the donepezil-treated group revealed significantly (P < 0.05) higher FSH levels in the treatment groups. Data are presented in Table S3.

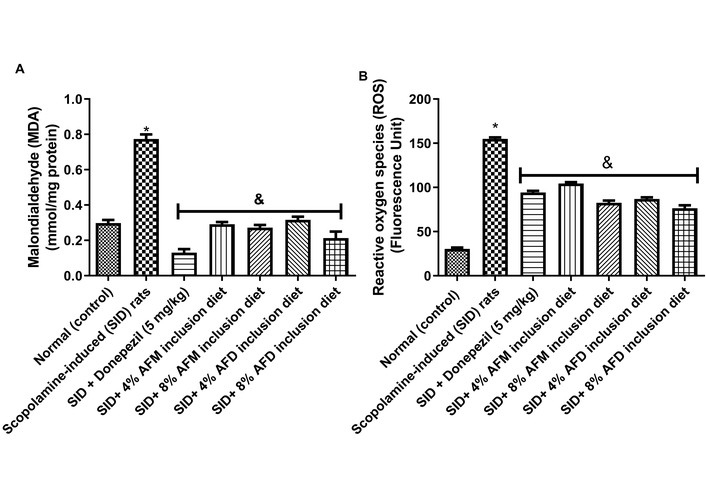

Figure 5 represents MDA (A) and ROS (B) levels in the testes of the experimental rats. SID rats showed elevated (P < 0.05) MDA (0.77 ± 0.05 mmol/mg protein) and ROS (154.90 ± 3.34 fluorescence unit) levels compared with the normal rats (0.30 ± 0.03 and 30.42 ± 2.86 mmol/mg protein, respectively). However, dietary supplementation with 4% AFM (MDA = 0.29 ± 0.02 mmol/mg protein; ROS = 104.40 ± 3.08 fluorescence unit), 8% AFM (MDA = 0.27 ± 0.03 mmol/mg protein; ROS = 82.60 ± 4.81 fluorescence unit), 4% AFD (MDA = 0.32 ± 0.03 mmol/mg protein; ROS = 86.85 ± 3.94 fluorescence unit), and 8% AFD (MDA = 0.21 ± 0.06 mmol/mg protein; ROS = 76.47 ± 6.66 fluorescence unit) significantly (P < 0.05) reduced when compared with untreated SID rats, with the higher doses generally showing better improvement. Comparisons between AFM and AFD at equivalent doses showed no significant differences. Donepezil (0.13 ± 0.04 mmol/mg protein; 94.30 ± 3.60 fluorescence unit) also lowered MDA and ROS levels, but without a consistent advantage over the AFM- and AFD-supplemented groups. Data are presented in Table S4.

Effects of AFM and AFD seed dietary inclusion on (A) malondialdehyde (MDA) level and (B) reactive oxygen species (ROS) level in the testis of SID male rats. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of replicate determinations (n = 4). Significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. normal (control); & P < 0.05 vs. SID rats. AFM: Aframomum melegueta; AFD: Aframomum danielli; SID: scopolamine-induced.

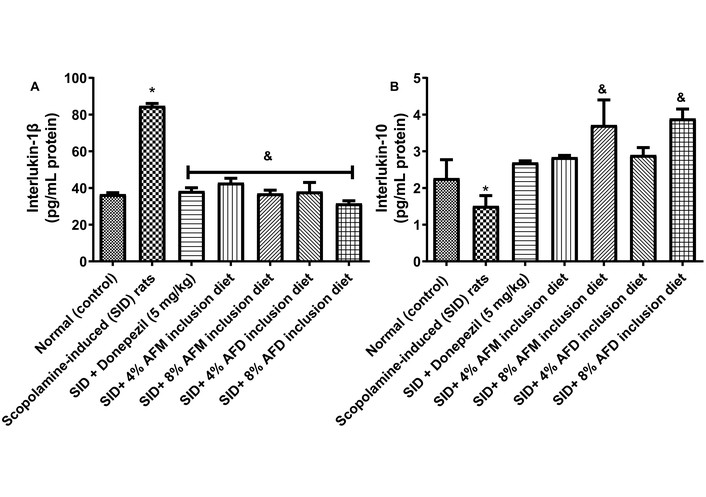

Figure 6 shows serum IL-Iβ (A) and IL-10 (B) concentrations in normal rats, untreated SID rats, donepezil-treated SID rats, and SID rats fed with diets supplemented with AFM or AFD (4% and 8% respectively). IL-1β concentrations were significantly elevated (P < 0.05) in SID rats (84.72 ± 1.865 pg/mL protein) compared with the normal control group (36.62 ± 1.13 pg/mL protein). Treatment with donepezil (39.32 ± 2.53 pg/mL protein), 4% AFM (42.84 ± 3.48 pg/mL protein), 8% AFM (36.52 ± 2.57 pg/mL protein), 4% AFD (38.04 ± 6.826 pg/mL protein), and 8% AFD (31.55 ± 2.11 pg/mL protein) significantly (P < 0.05) reduced IL-1β levels relative to untreated SID rats, with no significant differences observed between AFM and AFD at similar inclusion levels. In contrast, the IL-10 concentration declined significantly in SID rats (1.510 ± 0.40) when compared with the normal control group (2.27 ± 0.71). Treatment with donepezil (2.70 ± 0.06), 4% AFM (2.84 ± 0.07), 8% AFM (3.71 ± 0.58), 4% AFD (2.90 ± 0.29) and 8% AFD (3.89 ± 0.37) mildly increased IL-10 concentrations relative to the SID group. However, only the 8% AFM and 8% AFD diets produced statistically significant (P < 0.05) increases compared with the untreated SID rats.

Effects of AFM and AFD seed dietary inclusion on (A) interleukin-1β and (B) interleukin-10 concentrations in the serum of SID male rats. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of replicate determinations (n = 4). Significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. normal (control); & P < 0.05 vs. SID rats. AFM: Aframomum melegueta; AFD: Aframomum danielli; SID: scopolamine-induced. Adapted with permission from [23]. © 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH. The reuse occurred because the data were directly relevant to the mechanistic interpretation of the present study.

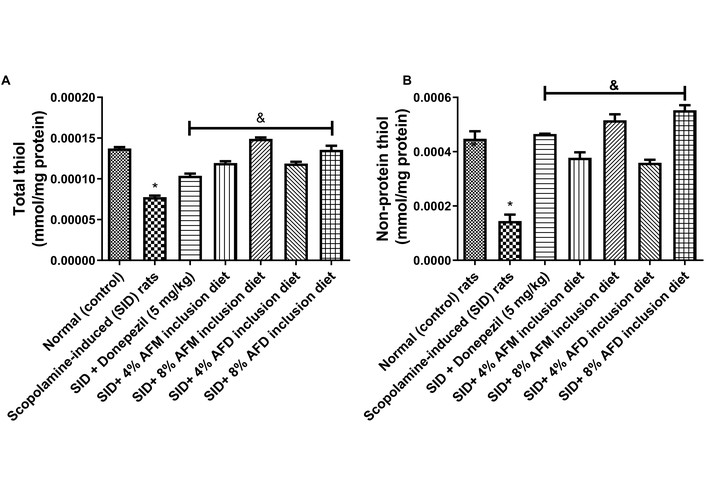

TSH and NSH concentrations (mmol/mg protein) in the testes of the experimental rats are illustrated in Figure 7. The untreated SID rats exhibited significantly (P < 0.05) lower TSH levels (0.000076 ± 0.000004) and NSH levels (0.000145 ± 0.000041) compared to the normal control group (0.000137 ± 0.000003; 0.000448 ± 0.000048). Pre-treatment with donepezil (0.000104 ± 0.000005), 4% AFM (0.000119 ± 0.000004), 8% AFM (0.000149 ± 0.000003), 4% AFD (0.000119 ± 0.000004), and 8% AFD (0.000136 ± 0.000010) were produced (P < 0.05) elevated TSH concentration when compared with the untreated SID group. While same-dose AFM and AFD inclusions revealed no significant variation, significant (P < 0.05) differences were observed between donepezil and the treatment groups. Similarly, NSH concentration was significantly increased in treatment with donepezil (0.000465 ± 0.00002), 4% AFM (0.000378 ± 0.000035), 8% AFM (0.000516 ± 0.000038), 4% AFD (0.000359 ± 0.000019), and 8% AFD (0.000553 ± 0.000032), relative to the untreated SID rats, although no significant difference was observed between AFM and AFD at similar inclusion doses.

Effects of AFM and AFD seed dietary inclusion on (A) TSH level and (B) NSH level in the testis of SID male rats. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of replicate determinations (n = 4). Significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. * P < 0.05 vs. normal (control); & P < 0.05 vs. SID rats. AFM: Aframomum melegueta; AFD: Aframomum danielli; SID: scopolamine-induced; TSH: total thiol; NSH: non-protein thiol.

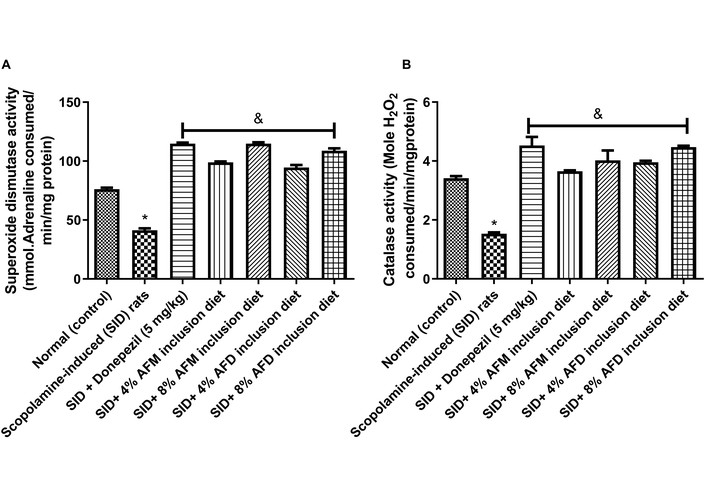

Figure 8 represents SOD (mmol/mg protein) and CAT (min/mg protein) activities measured in the testes of the experimental rats. The untreated SID rats showed significantly reduced (P < 0.05) SOD (41.37 ± 2.64) and CAT (1.53 ± 0.08) activities compared with the normal (control) group (76.19 ± 2.06 and 3.42 ± 0.12, respectively). Dietary inclusions of 4% and 8% AFM or AFD significantly (P < 0.05) enhanced SOD and CAT activities when compared with the untreated SID group. A clear dose-related effect was observed, with 8% AFM (114.90 ± 1.88; 4.02 ± 0.58, respectively) and 8% AFD (108.80 ± 3.50; 4.47 ± 0.08) producing the greatest improvements compared with 4% AFM (98.91 ± 1.30; 3.65 ± 0.05) and 4% AFD (94.60 ± 3.68; 3.96 ± 0.09). Differences between AFM and AFD at equivalent doses were not statistically significant. Donepezil (114.80 ± 1.47; 4.53 ± 0.50) also enhanced SOD and CAT activities compared to SID rats.

Effects of AFM and AFD seed dietary inclusion on (A) SOD and (B) CAT activities in the testes of SID male rats. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of replicate determinations (n = 4). Significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. AFM: Aframomum melegueta; AFD: Aframomum danielli; SID: scopolamine-induced; SOD: superoxide dismutase; CAT: catalase.

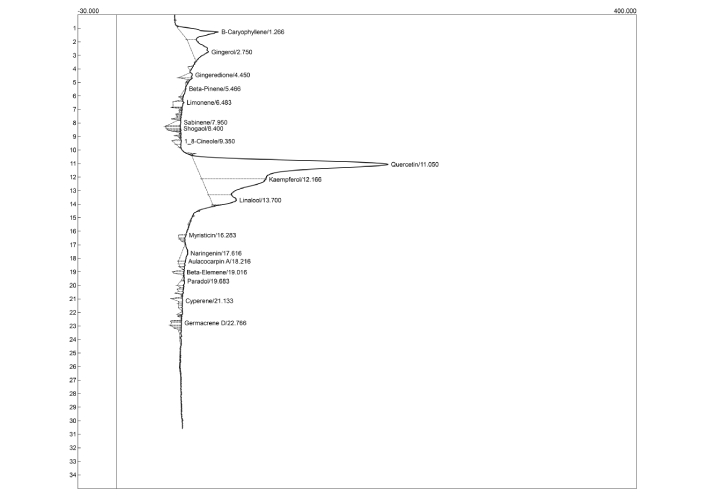

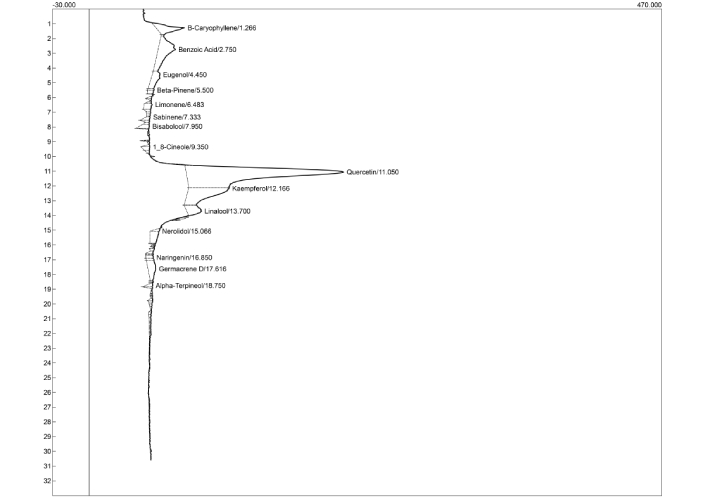

Figures 9 and 10 and Tables 2 and 3 represent the HPLC chromatograms and quantified concentrations of important bioactive compounds identified in AFM and AFD seeds, respectively. The chromatographic profile revealed the presence of important phytoconstituents, including β-caryophyllene, gingerol, gingeredione, β-pinene, limonene, sabinene, shogaol, quercetin, and kaempferol among others.

HPLC-DAD chromatographic profile of Aframomum melegueta seed extract. HPLC-DAD: high performance liquid chromatography diode array detector.

HPLC-DAD chromatographic profile of Aframomum danielli seed extract. HPLC-DAD: high performance liquid chromatography diode array detector.

Identification of phenolic compounds and/or derivatives present in AFM seeds using HPLC-DAD.

| Compounds | Retention time (min) | Concentration (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|

| β-caryophyllene | 1.27 | 0.64 |

| Gingerol | 2.75 | 0.59 |

| Gingeredione | 4.45 | 0.07 |

| β-Pinene | 5.47 | 0.04 |

| Limonene | 6.48 | 0.14 |

| Sabinene | 7.95 | 0.11 |

| Shogaol | 8.40 | 0.07 |

| 1,8-cineole | 9.35 | 0.07 |

| Quercetin | 11.05 | 5.98 |

| Kaempferol | 12.17 | 1.74 |

| Linalool | 13.70 | 0.56 |

| Myristicin | 16.28 | 0.05 |

| Naringenin | 17.62 | 0.21 |

| Aulacocarpin A | 18.22 | 0.05 |

| Beta-elemene | 19.02 | 0.04 |

| Paradol | 19.68 | 0.06 |

| Cyperene | 21.13 | 0.07 |

| Germacrene-D | 22.77 | 0.08 |

AFM: Aframomum melegueta; HPLC-DAD: high performance liquid chromatography diode array detector.

Identification of phenolic compounds and/or derivatives present in AFD seeds using HPLC-DAD.

| Compounds | Retention time (min) | Concentration (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|

| β-caryophyllene | 1.27 | 0.40 |

| Benzoic acid | 2.75 | 0.81 |

| Eugenol | 4.45 | 0.30 |

| β-Pinene | 5.50 | 0.05 |

| Limonene | 6.48 | 0.10 |

| Sabinene | 7.33 | 0.06 |

| Bisabolool | 7.95 | 0.09 |

| 1,8-cineole | 9.35 | 0.06 |

| Quercetin | 11.05 | 4.57 |

| Kaempferol | 12.17 | 1.11 |

| Linalool | 13.70 | 0.30 |

| Nerolidol | 15.07 | 0.21 |

| Naringenin | 16.85 | 0.05 |

| Germacrene-D | 17.62 | 0.31 |

| Alpha-tocopherol | 18.75 | 0.05 |

AFD: Aframomum danielli; HPLC-DAD: high performance liquid chromatography diode array detector.

With the growing global concern about male infertility and the multiple factors contributing to its prevalence [19, 42], this study investigated the impact of neurological disturbance on male reproductive health and explored the protective effects of AFM and AFD seeds supplemented diet on sperm quality, hormonal levels, inflammation, and oxidative status. HPLC profiling of AFM and AFD seeds revealed diverse flavonoids and phenolic compounds present in them, including but not limited to gingerol, quercetin, shogaol, naringenin, caffeic acid, paradol, eugenol, kaempferol, and β-caryophyllene. These compounds are known for antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, androgen regulation, and other reproductive protective activities. They have been reported to protect sperm viability [43] and suppress NF-κB-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokine release [44], among other pharmacological effects. Their presence provides biochemical justification for the findings reported in this study.

Sperm concentration reflects the number of sperm cells per milliliter of semen and remains a key determinant of male fertility, as reduced concentration lowers the probability of successful fertilization [45]. Sperm motility and morphology are equally critical, indicating the ability of sperm to traverse the female reproductive tract and fertilize an ovum. Healthy sperm are characterized by rapid progressive motility and NM (oval head and intact tail). In contrast, a high proportion of sluggish or non-motile sperm and structural abnormalities in the head, neck, or tail reflect impaired fertility.

The present findings confirm that scopolamine administration compromises or impairs sperm quality, as evidenced by significant reductions in sperm concentrations, motility, and morphology consistent with earlier reports that oxidative stress and cholinergic dysfunction adversely affect spermatogenesis [16]. These reductions likely arise from neuroendocrine disruption and oxidative injury affecting testicular germ-cell function, sperm motility, and epididymal maturation. However, dietary supplementation with AFM and AFD significantly improved sperm concentration, motility and NM in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Figures 2 and 3. Although 8% AFM yielded the most pronounced recovery, statistical comparisons showed comparable efficacy between AFM and AFD across sperm parameters. Meanwhile, donepezil produced mild, non-significant improvements, especially in fast motility, which may reflect its central cholinesterase-inhibitory action with limited peripheral reproductive effects [16], highlighting the broader advantages of AFM and AFD in neurotoxic conditions.

The observed improvements may be attributed to the effects of the phytochemicals identified in both seeds. High levels of quercetin, gingerol, naringenin, β-caryophyllene, and kaempferol enhance sperm viability, motility, and mitochondrial protection from free radicals [43, 46]. Additional compounds such as caffeic acid and shogaol—though less abundant—are potent antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents [16, 27], capable of neutralizing ROS, stabilizing sperm membranes, and preserving morphology. By supporting mitochondrial function, these bioactives may act synergistically to sustain the energy-dependent processes required for sperm viability [47].

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis governs male reproductive physiology: gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulates luteinizing hormone (LH) and FSH release, ultimately promoting testosterone synthesis and spermatogenesis [48–51]. In this study, untreated SID rats exhibited significantly reduced serum testosterone (Figure 4), suggesting endocrine disruption linked to neurological stress and oxidative damage [17, 52]. Similarly, the observed reduction in FSH concentration could be linked to the impaired Sertoli cell signaling and spermatogenic activity.

FSH regulates spermatogenesis by promoting spermatogonia proliferation, germ-cell survival, and completion of spermiogenesis, resulting in mature spermatozoa with intact structural integrity [53]. Dietary supplementation with AFM and AFD effectively restored reproductive hormone balance. However, both supplements significantly elevated FSH concentrations, indicating a positive stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, physiologically beneficial for the maturation of Sertoli cells and improved overall testicular function. Furthermore, higher testosterone concentrations were evident in the AFM treatment groups, suggesting greater steroidogenic potential compared with AFD. Although. AFD produced a milder, non-significant rise in testosterone levels, the trend toward improvement suggests possible benefits at higher inclusion levels. Donepezil showed only modest hormonal effects, consistent with its limited role in endocrine modulation.

These hormonal restorations suggest that AFM and AFD may act beyond cholinergic modulation reported earlier [23], extending to steroidogenic support via saponins, flavonoids, phenolics, and glycosides that neutralize ROS, regulate steroidogenic enzyme genes, and stabilize Leydig-cell function. Quercetin has been shown to upregulate StAR and CYP11A1 expression [54], while naringenin, caffeic acid, and eugenol improve FSH responsiveness and Sertoli cell antioxidant status [55–57]. Saponins and glycosides further support androgen and gonadotropin regulation [28], collectively contributing to protection against SID infertility.

Oxidative stress arises when excessive ROS overwhelm intrinsic antioxidant defenses, causing cellular and molecular injury [58]. The testes and spermatozoa are particularly vulnerable due to high polyunsaturated lipid content and limited antioxidant capacity, making oxidative stress a major contributor to male infertility [59, 60]. It is a major contributor to male infertility, acting synergistically with inflammation to impair spermatogenesis and sperm function. SID rats exhibited elevated testicular ROS and MDA levels (Figure 5), indicating lipid peroxidation, alongside increased IL-1β and decreased IL-10 (Table S4), reflecting inflammation and compromised testicular integrity [61]. These findings support the concept that SID neurotoxicity extends peripherally, promoting oxidative and inflammatory disturbances in the testes. Elevated IL-1β levels can stimulate the activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase and free radicals, leading to mitochondria depolarization, DNA fragmentation, and death of germ cells. IL-10, on the other hand, is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that suppresses inflammatory mediators and conserves spermatogenic integrity. Thus, the findings from this study agree with previous evidence linking neuro-disorder to testicular oxidative damage and inflammation [16].

Pre-treatment with donepezil, AFM, and AFD significantly reduced ROS and MDA while down-regulating IL-1β and elevating IL-10 in a dose-dependent manner, consistent with their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [62, 63]. Bioactives such as kaempferol, quercetin, naringenin, β-caryophyllene, eugenol, and 6-gingerol likely mediated these effects by suppressing NF-κB activation, cyclooxygenase-2, iNOS, and lipid peroxidation while activating Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathways [44, 64–68]. Collectively, these actions preserved testicular integrity. However, endogenous antioxidant mechanisms, including thiol compounds, SOD, and CAT, form the first line of defense against oxidative stress [69–71].

Decreased total and NSH in SID rats indicate depleted antioxidant capacity, increasing vulnerability to oxidative injury. Restoration of thiol levels in AFM- and AFD-treated rats (Figure 7) underscores their role in redox stabilization. Enhanced SOD and CAT activities in supplemented groups, as seen in Figure 8 and detailed in Table S5, further demonstrate improved endogenous defense. Mechanistically, SOD converts superoxide radicals to hydrogen peroxide, which CAT subsequently decomposes, preventing oxidative injury to sperm. AFM and AFD seeds contain potent antioxidant phytochemicals paradol, quercetin, kaempferol, 6-gingerol, naringenin, and β-caryophyllene that neutralize free radicals and stabilize membranes [72–76]. These bioactives also upregulate antioxidant genes, supporting sperm motility and mitochondrial integrity.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that scopolamine impairs sperm quality and testicular function. While AFM- and AFD-supplemented diets confer significant protective effects by improving sperm parameters, restoring hormonal balance, and modulating oxidative and inflammatory pathways. Donepezil showed only partial reproductive benefits, suggesting the need for complementary strategies that target both neural and testicular dysfunction. AFM and AFD seeds may therefore represent promising nutraceutical interventions for male infertility associated with oxidative and neurodegenerative disorders. Nevertheless, limitations including modest sample size, a single neurotoxic model, and the absence of histological and molecular validation limit generalizability. Future work should incorporate larger cohorts, immunohistology and gene-expression analyses, broader hormonal profiling, and pharmacokinetic/safety evaluations to advance translation toward preclinical and clinical applications.

AFD: Aframomum danielli

AFM: Aframomum melegueta

BW: body weight

CAT: catalase

DAD: diode array detector

ELISA: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone

HD: head defects

HPLC: high performance liquid chromatography

IL-10: interleukin-10

IL-1β: interleukin-1β

MDA: malondialdehyde

ND: neck defects

NM: normal morphology

NSH: non-protein thiol

ROS: reactive oxygen species

SID: scopolamine-induced

SOD: superoxide dismutase

TD: tail defects

TSH: total thiol

The supplementary materials for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1006123_sup_1.pdf.

The authors sincerely acknowledge Mr Olugboyega Jeremiah Akinniyi and Mr Ojo Olajide Raymond for their technical assistance throughout the course of the research.

OMA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. EAO: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. IAO: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources. SOA: Formal analysis, Investigation. GO: Supervision, Methodology, Resources. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The Animal research study was approved by the “Animal Experiment Ethical Committee of Federal University of Technology Akure”, with reference number FUTA/23/027.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

This research received no external funding.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 417

Download: 24

Times Cited: 0