Affiliation:

1Department of Neurology, 1st Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin 150001, Heilongjiang, P.R. China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6395-7625

Affiliation:

2School/Hospital of Stomatology, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu, P.R. China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3721-4915

Affiliation:

2School/Hospital of Stomatology, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu, P.R. China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-0768-0777

Affiliation:

2School/Hospital of Stomatology, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu, P.R. China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-2437-3575

Affiliation:

3Qingdao Jiazhi Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Qingdao 266100, Shandong, P.R. China

4Department of Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, 17177 Stockholm, Sweden

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9885-4159

Affiliation:

5Department of Clinical Dentistry, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Bergen, 5020 Bergen, Norway

Email: tie-jun.shi@uib.no; tjstenshi@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8736-0329

Explor Neurosci. 2026;5:1006124 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/en.2026.1006124

Received: September 29, 2025 Accepted: January 05, 2026 Published: February 05, 2026

Academic Editor: Giustino Varrassi, President of the Paolo Procacci Foundation, Italy

Aim: Tissue transglutaminase [transglutaminase 2 (TG2)] is implicated in central neuronal apoptosis and is expressed in the peripheral nervous system; however, its role in sensory neuron survival and neuropathic pain after nerve injury remains poorly defined. This study examined whether TG2 knockout (KO) affects dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neuron survival and pain-related behaviors following sciatic nerve injury.

Methods: TG2 KO mice and wild-type (WT) controls underwent complete sciatic nerve transection (axotomy). Pain-related behavior was evaluated using detailed autotomy scoring over 14 days. DRG neuron survival was assessed using unbiased stereological counts.

Results: TG2 KO resulted in a distinct, previously unreported “atypical autotomy” pattern, with lesions localized mainly to the midplantar paw region. In contrast, WT mice exhibited typical autotomy directed primarily at the toes. Despite this clear difference in pain phenotype, stereological analysis revealed that TG2 KO did not alter neuronal counts in intact or axotomized DRGs, with both groups showing comparable, significant neuronal loss after injury.

Conclusions: These findings indicate that TG2 functions as an important modulator of neuropathic pain but is not required for neuronal survival in the adult DRG following nerve injury.

Transglutaminase 2 (TG2) is a ubiquitously expressed, calcium-dependent enzyme that catalyzes protein cross-linking and is involved in diverse cellular processes, including cell adhesion, differentiation, and apoptosis [1, 2]. In the nervous system, TG2 contributes to neuronal development and synaptic regulation [3, 4]. Notably, TG2 upregulation is a hallmark of several neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease, and its genetic deletion can prevent neuronal loss in corresponding animal models [5, 6]. These observations have established TG2 as a key mediator of cell death in the central nervous system (CNS).

In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), TG2 is also involved in injury responses. Elevated TG2 activity has been observed in sensory and sympathetic ganglia after nerve damage [7, 8], and TG2 antibody reactivity is reported in patients with peripheral neuropathies [9]. Peripheral nerve injury consistently triggers sensory neuron death in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) [10–12], a key component of the resulting pathophysiology. Despite these connections, a significant knowledge gap persists. Although TG2’s pro-apoptotic role is well-established in the CNS, its specific function in adult sensory neuron survival following peripheral nerve injury remains unclear. It is often assumed that TG2 functions similarly across nervous system domains, yet its influence on neuropathic pain behaviors remains poorly characterized.

This study investigated the consequences of TG2 knockout (KO) in models of peripheral nerve injury. We tested the hypothesis that TG2 KO would protect DRG neurons from axotomy-induced death. Concurrently, we examined the role of TG2 in the development and expression of neuropathic pain, an area where its effects were less predictable. Using TG2 KO mice, we demonstrate that TG2 is not required for sensory neuron survival but acts as a critical modulator of neuropathic pain phenotypes.

Twenty-week-old male TG2 KO mice, generated as previously described [6], and age-matched C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) controls were used. All procedures were approved by the Northern Stockholm Animal Ethics Committee (Norra Djurförsöksetiska Nämnd; approval number N150/11) and conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Every effort was made to minimize animal use and suffering.

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg), consistent with institutional guidelines in effect during the experimental period (1994–2010). To assess distinct components of neuropathic pain, two complementary nerve injury models were employed. (1) In the axotomy model, the left sciatic nerve was exposed at the mid-thigh, transected, and a 5-mm segment was excised [12]. This model was used to study spontaneous pain behavior (autotomy) and neuronal survival. Animals were maintained for 14 days post-surgery (n = 10 or 15 for WT behavior, n = 16 for KO behavior; n = 6 for stereology). (2) In the spared nerve injury (SNI) model, the peroneal and tibial nerves were ligated and transected (2–4 mm removed), while the sural nerve was left intact [13]. This model, which partially preserves sensory innervation, was used to assess evoked pain behaviors (allodynia, hyperalgesia). Animals survived for 7 days post-surgery (n = 6 per group for behavior).

Predefined humane endpoints were strictly enforced. Mice were scheduled for immediate euthanasia if they met any of the following criteria: (1) severe autotomy, defined as a score exceeding 6 on the Wall scale [14]; (2) loss of > 20% of initial body weight; or (3) signs of severe distress (e.g., profound lethargy, dehydration, or inability to access food or water). No animals met these criteria before the planned experimental endpoint.

For terminal tissue collection at the planned study endpoint, mice were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium. Tissue collection was performed by trained personnel via decapitation or transcardial perfusion with fixative [12]. In the event an animal met a predefined humane endpoint requiring immediate intervention, euthanasia was performed via CO2 inhalation followed by decapitation.

In the SNI model, evoked pain hypersensitivity was assessed bilaterally using standard sensory tests: tactile allodynia (von Frey filaments), mechanical hyperalgesia (pinprick), and cold allodynia (acetone) [15].

To quantify spontaneous neuropathic pain in the axotomy model, autotomy behavior was monitored daily for 14 days. We developed a unified autotomy severity score to capture both the location and severity of self-mutilation, encompassing both classic (toe-focused) and atypical (mid-plantar) patterns observed in this study. This 0–5 scale (Table 1) was adapted from principles of the Wagner staging system for tissue damage, a framework also endorsed in the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes [16, 17]. The scale focuses on objective anatomical features such as skin integrity and depth of tissue involvement. The score assigned to each mouse at a given time point corresponded to the highest severity stage present on the ipsilateral paw. Autotomy incidence and scores were recorded on postoperative days 3 and 14 [14, 18, 19].

Unified autotomy severity scoring system (0–5 scale).

| Severity stage | Unified score | Classic autotomy (toe damage) | Atypical autotomy (plantar damage) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No autotomy | 0 | No visible damage. | No visible damage. |

| Stage 1 | 1 | Only superficial skin scratches/erosion on the toe(s). | Epidermis intact; mild localized redness/swelling. |

| Stage 2 | 2 | Partial loss of a toe, or significant damage to the epidermis/dermis of multiple toes. | Partial-thickness skin loss involving the epidermis and extending into the dermis (superficial ulcer). |

| Stage 3 | 3 | Full loss of 1–2 toes, or damage reaching the bone of a single toe. | Full-thickness skin loss involving the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (deep ulcer). |

| Stage 4 | 4 | Full loss of toes, or damage reaching the bone (osteolysis) in multiple toes. | Full-thickness skin loss with extensive damage reaching the bone/fascia. |

| Stage 5 | 5 | Self-amputation of the entire distal paw, or massive necrosis/infection, making the wound unstageable. | Extensive necrosis or unstageable wound covering a large plantar area. |

This scoring system quantifies pain-related tissue damage by lesion depth on a single 0–5 scale, regardless of location (toe or mid-plantar). The assigned score corresponds to the highest observed severity stage on the paw and serves as the dependent variable for two-way repeated measures ANOVA. Application example: If a mouse has a stage 4 lesion on its toe and a stage 2 lesion on its mid-plantar region, the unified score is 4. If it has a stage 3 mid-plantar lesion and no toe damage, the unified score is 3.

Lumbar (L) 5 DRGs and L4–5 spinal cord segments were sectioned at 12 μm (DRG) or 20 μm (spinal cord) thickness. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies against Iba1 (1:2,000; #01-1974; Wako Pure Chemical Industries) or phospho-p38 MAPK (p-p38; 1:400; Thr180/Tyr182; #9211; Cell Signaling Technology). Immunoreactivity was visualized using a tyramide signal amplification (TSA) Plus kit (#NEL741001KT; PerkinElmer) [15] and analyzed by Sarastro 1000 confocal laser scanning system. Specificity was confirmed by preadsorption controls.

The total number of L5 DRG neurons was estimated using unbiased stereology (the optical fractionator) [12]. Perfused DRGs from TG2 KO and WT mice (n = 6 per group) were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) medium and serially sectioned at 30 μm. Every third section was systematically sampled after a random start. Neurons were identified by morphology and propidium iodide (PI) counterstaining (0.001%) and counted using a confocal laser scanning system (Leica TCS SPE). Ganglion volume was estimated using the Cavalieri principle [20].

For p-p38 positive neuronal profile (NP) counts, 12 μm-thick sections were used with every fifth section selected. The percentage of p-p38-immunoreactive (IR) NPs was calculated as: (p-p38-IR NPs/total PI-stained NPs) × 100. Four to eight sections per DRG were analyzed (n = 5 mice per group), with 900–2,100 NPs counted per ganglion. Iba1 immunoreactivity in the L5 DRG and spinal dorsal horn (laminae I–IV) was semi-quantitatively assessed by measuring the mean fluorescence intensity using ImageJ software (version 1.54g).

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9, with significance set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Neuronal and cellular analyses:

Body weight: Unpaired Student’s t-test (WT vs. KO, n = 10 per group).

DRG neuron counts: Two-way ANOVA with factors genotype (WT, KO) and side (contralateral, ipsilateral; n = 6 per group). Post-hoc comparisons used paired t-tests (ipsilateral vs. contralateral within genotype) and unpaired t-tests (WT vs. KO for each side).

p-p38 immunoreactivity: Two-way ANOVA with factors genotype (WT, KO) and condition (control, axotomy 3d, axotomy 14d, SNI 7d; n = 5 per group). Sidak’s test was used for post-hoc comparisons.

Microglial activation (Iba1): Two-way ANOVA with factors genotype (WT, KO) and side (contralateral, ipsilateral; axotomy 14d; n = 6 per group for DRG, n = 7 per group for spinal dorsal horn). Sidak’s test was used for post-hoc comparisons.

Autotomy analyses:

Autotomy incidence and pattern: Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportion of mice exhibiting classic (toe-directed) vs. atypical (mid-plantar) autotomy between genotypes at days 3 (n = 10 per group) and 14 (WT n = 15, KO n = 16) post-axotomy. Mice with mixed patterns were classified as atypical.

Autotomy severity scores: Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with genotype (between-subjects; WT n = 10, KO n = 16) and time (within-subjects; days 3 and 14). Data were analyzed as paired measurements across time.

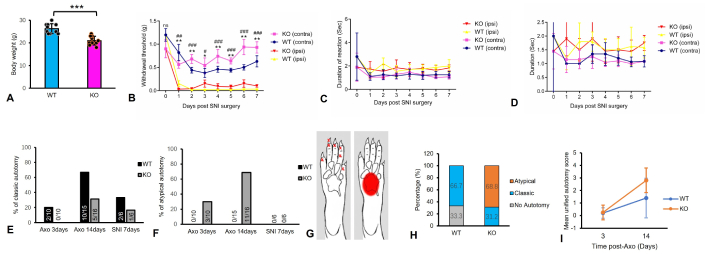

TG2 KO mice had a significantly lower body weight than WT controls (21.0 ± 1.9 g vs. 26.3 ± 2.2 g; n = 10, p < 0.001, unpaired t-test; Figure 1A). Baseline mechanical sensitivity (von Frey threshold: KO, 0.92 ± 0.19 g vs. WT, 1.16 ± 0.14 g; p > 0.05) and responses to cold or punctate stimuli did not differ between genotypes. Following SNI, both WT and KO mice developed comparable mechanical allodynia in the ipsilateral paw from day 1 to 7 (two-way ANOVA, effect of injury: p < 0.001; effect of genotype: p > 0.05). No significant genotypic differences in hypersensitivity were detected at any time point (Figure 1B–D). Under baseline conditions, TG2 KO mice displayed no overt motor deficits or alterations in general grooming compared to WT littermates.

TG2 KO induces a unique atypical autotomy behavior after sciatic nerve injury. (A) Body weight of 20-week-old TG2 KO and WT mice (n = 10 per group; ***: p < 0.001, unpaired t-test). (B) Mechanical allodynia assessed by von Frey test in the contralateral (contra) and ipsilateral (ipsi) hind paw after SNI (n = 6 per group; * or #: p < 0.05, ** or ##: p < 0.01, ###: p < 0.001 vs. contralateral paw, two-way ANOVA). (C, D) Mechanical hyperalgesia (pinprick test, C) and cold allodynia (acetone test, D) show no significant difference between WT and KO mice after SNI (n = 6 per group; two-way ANOVA). (E) Proportion of mice exhibiting any classic autotomy (toe-directed) after axotomy or SNI. (F) Proportion of mice exhibiting atypical autotomy (mid-plantar lesions) after axotomy or SNI. (G) Schematic of mouse hind paw indicating locations of typical (toes, red cross) and atypical (mid-plantar pad, red square) autotomy. (H) Incidence of classic and atypical autotomy patterns. At 3 days post-axotomy, patterns differed significantly between genotypes (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0476). This difference was highly significant at 14 days (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001; n = 15 WT, 16 KO). (I) Autotomy severity quantified using the unified autotomy score (0–5 scale) and analyzed by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (genotype × time). A significant genotype × time interaction (p = 0.0025) indicates a divergent progression of severity, which increased more in KO mice than in WT mice over time (n = 10 WT, 16 KO). WT: wild-type; KO: knockout; ns: not significant; Axo: axotomy; SNI: spared nerve injury; TG2: transglutaminase 2.

To assess spontaneous neuropathic pain, autotomy was monitored for 14 days after sciatic nerve axotomy. A profound phenotypic difference emerged between genotypes. WT mice developed classic autotomy, with lesions beginning around day 3 and directed primarily at the toes. In contrast, while the onset of autotomy in TG2 KO mice was similarly early, it manifested as a distinct atypical pattern with lesions confined to the mid-plantar paw surface. The impact of TG2 KO on autotomy pattern was statistically from the earliest stages. At 3 days post-axotomy (n = 10 per group), all autotomizing WT mice exhibited the classic pattern (2/2), while all autotomizing KO mice showed the atypical pattern (3/3) (Figure 1E and F; Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0476). By day 14, this divergence became even more pronounced. In WT mice (n = 15), 66.7% (10/15) developed autotomy, all of which followed the classic pattern. Conversely, 100% of TG2 KO mice (n = 16) developed autotomy by day 14 (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0177). Within this KO group, the majority of mice exhibited the atypical pattern (68.8%, 11/16), whereas classic autotomy was observed in only 31.2% (5/16). The shift from a classic to an atypical behavioral phenotype in the absence of TG2 was highly significant (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0007; Figure 1E–H). Notably, autotomy was rare following SNI, and no atypical behavior was observed in either genotype in that model (Figure 1E and F).

To quantify severity, we applied a unified autotomy score (0–5 scale). A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (genotype × time) revealed a significant main effect of time [F(1, 24) = 20.90, p < 0.0001] and a significant genotype × time interaction [F(1, 24) = 11.28, p = 0.0025]. The main effect of genotype was also significant (p = 0.016). At day 3, severity scores were low and comparable between KO (0.25 ± 0.58) and WT mice (0.20 ± 0.42). However, by day 14, autotomy severity increased significantly more in KO mice (2.81 ± 0.98) than in WT littermates (1.40 ± 1.58) (p < 0.01, post-hoc test) (Figure 1I). These results demonstrate that the absence of TG2 leads to an accelerated and more severe progression of spontaneous neuropathic pain behavior following nerve injury.

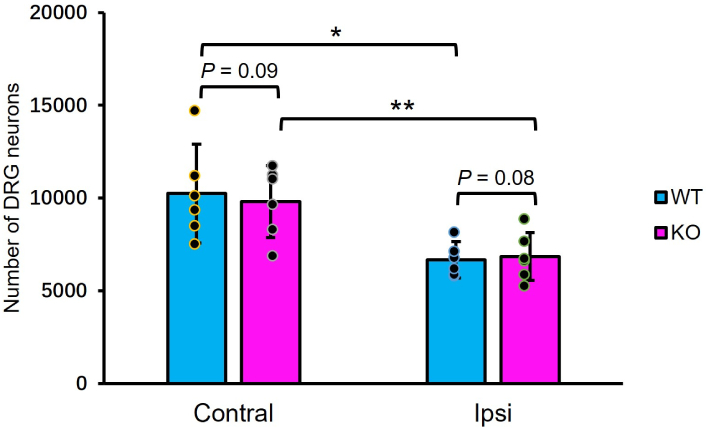

Sensory neuron survival in the L5 DRG was evaluated using unbiased stereology (Figure 2). In the contralateral DRG, neuronal counts did not differ between TG2 KO and WT mice (KO: 9,822 ± 1,911 vs. WT: 10,212 ± 2,577; n = 6, p > 0.05, unpaired t-test). Axotomy induced a significant loss of approximately 30% of neurons in the ipsilateral DRG of both WT (6,668 ± 903 vs. contralateral 10,212 ± 2,577; p < 0.05, paired t-test) and KO mice (6,848 ± 1,289 vs. contralateral 9,822 ± 1,911; p < 0.01, paired t-test). Critically, the magnitude of this loss was not different between genotypes, as the number of surviving neurons in the ipsilateral DRG was similar in KO and WT mice (6,848 ± 1,289 vs. 6,668 ± 903; p > 0.05, unpaired t-test).

TG2 KO does not affect sensory neuron survival in the DRG. Stereological counts of L5 DRG neurons 14 days after sciatic nerve axotomy. A significant loss of neurons is observed ipsilateral to the injury in both WT and TG2 KO mice. The number of neurons does not differ between genotypes in either the contralateral (intact) or ipsilateral (axotomized) DRG. Data are mean ± SD (n = 6 per group; *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ipsilateral vs. contralateral within genotype, paired t-test; not significant for KO vs. WT on either side, unpaired t-test). DRG: dorsal root ganglion; WT: wild-type; KO: knockout; TG2: transglutaminase 2; L5: lumbar 5; Contral: contralateral; Ipsi: ipsilateral; SD: standard deviation.

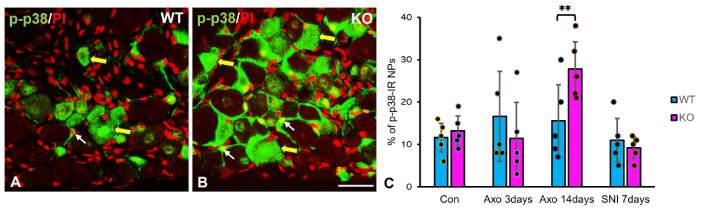

We next examined whether TG2 KO alters stress kinase signaling by quantifying p-p38-IR NPs in the L5 DRG (Figure 3). Under control conditions, the percentage of p-p38-IR NPs did not differ between WT and KO mice. Similarly, no genotypic differences were observed at 3 days post-axotomy or 7 days after SNI. In contrast, at 14 days post-axotomy, TG2 KO mice exhibited a significantly higher percentage of p-p38-IR NPs (27.8 ± 6.2%) compared to WT littermates (15.6 ± 8.5%; p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc test) (Figure 3C). This indicates that TG2 deficiency leads to a specific and prolonged enhancement of p-p38 activation in the later phase of axotomy-induced injury (Figure 3A and B).

Enhanced p-p38 activation in axotomized DRGs of TG2 KO mice. (A, B) Immunohistochemical micrographs showing p-p38-IR (green) in the ipsilateral L5 DRGs of WT (A) and TG2 KO (B) mice 14 days post-axotomy. Nuclei are counterstained with propidium iodide (PI, red). Large yellow arrows indicate p-p38-IR neurons; small white arrows indicate p-p38-IR satellite cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Quantification of the percentage of p-p38-IR NPs in L5 DRGs after sciatic nerve axotomy or SNI. The increase in p-p38-IR NPs at 14 days post-axotomy was significantly greater in KO mice than in WT mice (n = 5 per group; **: p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc test). Data are mean ± SD. p-p38: phospho-p38 MAPK; WT: wild-type; KO: knockout; IR: immunoreactive; NPs: neuronal profiles; SNI: spared nerve injury; Con: control; Axo: axotomy; DRGs: dorsal root ganglia; TG2: transglutaminase 2; L5: lumbar 5; SD: standard deviation.

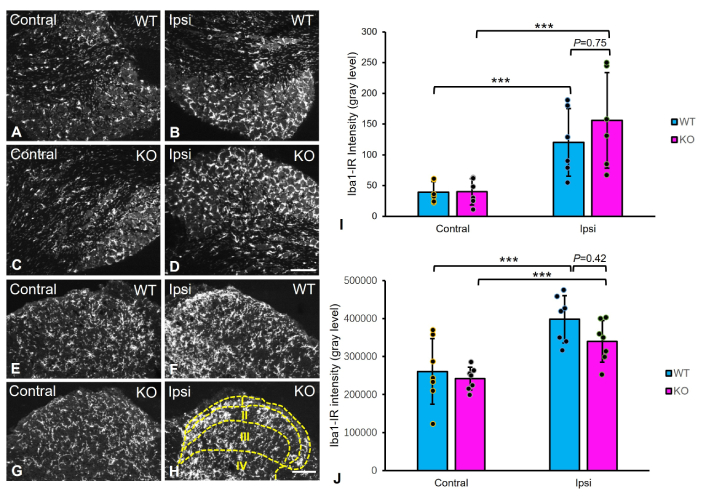

To determine if TG2 KO alters microglial activation in response to nerve injury, we quantified Iba1 immunofluorescence intensity in the L5 DRG (Figure 4A–D) and the L4–5 spinal dorsal horn segments 14 days post-axotomy (Figure 4E–H). Nerve injury induced a robust upregulation of Iba1 immunofluorescence on the ipsilateral side in both the DRG and spinal dorsal horn of WT and KO mice (Figure 4I and J; two-way ANOVA, p < 0.001).

Microglial activation in the DRGs and spinal dorsal horn of WT and TG2 KO mice after sciatic nerve axotomy. (A–D) Representative micrographs of Iba1 immunoreactivity in the contralateral (Contral) and ipsilateral (Ipsi) L5 DRGs. (E–H) Representative micrographs of Iba1 immunoreactivity in the lumbar spinal dorsal horn. (I and J) Semi-quantitative analysis of Iba1 immunoreactivity intensity in the ipsilateral and contralateral DRGs (I) and spinal dorsal horn (laminae I–IV; dotted lines represent boundaries of the four dorsal horn laminae) (J). While axotomy induced a strong microglial activation in both ipsilateral DRGs and spinal cord, no significant difference in activation level was observed between WT and TG2 KO mice (DRG: n = 6 per group; spinal cord: n = 7 per group; ***: p < 0.001 for ipsilateral vs. contralateral within genotype, two-way ANOVA; not significant for WT vs. KO on the ipsilateral side, Sidak’s post-hoc test). Data are mean ± SD. Scale bars: 200 μm (A–D); 100 μm (E–H). WT: wild-type; KO: knockout; IR: immunoreactive; DRGs: dorsal root ganglia; TG2: transglutaminase 2; L5: lumbar 5; SD: standard deviation.

In the DRG, Iba1 intensity on the ipsilateral side showed a non-significant trend toward being higher in KO mice (156.0 ± 79.5) than in WT mice (120.3 ± 55.5) (p = 0.75, Sidak’s post-hoc test). Similarly, in the spinal dorsal horn, the magnitude of microglial activation on the ipsilateral side did not differ significantly between genotypes (KO: 3.31 × 105 ± 5.8 × 104 vs. WT: 3.98 × 105 ± 6.0 × 104; p = 0.42). These results indicate that TG2 KO does not significantly modulate injury-induced microglial activation in either the DRG or spinal cord at this time point.

To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first direct evidence that TG2 plays dissociated roles in the PNS after nerve injury, acting as a critical modulator of neuropathic pain behavior while being dispensable for sensory neuron survival.

A central finding is that TG2 KO did not affect the number of sensory neurons in the DRG under baseline conditions or after axotomy. This stands in clear contrast to the established pro-apoptotic role of TG2 in models of central neurodegeneration, where its genetic ablation prevents neuronal loss [5, 6]. Our results demonstrate that the mechanisms governing neuronal vulnerability are not uniform and differ significantly between the central and PNSs. Therefore, TG2 is not a universal mediator of neuronal death. Adult sensory neurons do not require TG2 for their development or maintenance, nor is it a critical executor of injury-induced apoptosis in the PNS.

The most striking observation was the emergence of a unique “atypical autotomy” phenotype in TG2 KO mice. Autotomy is a behavioral correlation of spontaneous neuropathic pain, and its anatomical distribution is thought to reflect the perceived source of dysesthesias [14, 21, 22]. In TG2 KO mice, lesions were consistently localized to the mid-plantar paw surface, a pattern scarcely reported in the literature, suggesting a fundamental alteration in how spontaneous pain is processed or perceived. This phenotype cannot be attributed to a generalized change in nociceptive sensitivity, as baseline thresholds and injury-induced hypersensitivity were comparable between genotypes. Instead, it points to a specific role for TG2 in shaping the spatial or qualitative experience of neuropathic pain.

A plausible mechanism may involve TG2’s established role in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and cell-matrix interactions [23, 24]. As a critical mediator of ECM assembly and stability, TG2 KO could disrupt the precision of post-injury sensory reinnervation or central synaptic reorganization [25, 26]. We hypothesize that in the absence of TG2, subtle alterations in the morphology, connectivity, or topographic patterning of regenerating sensory fibers, or their central terminals in the dorsal horn, could remodel the spatial representation of pain signals, leading to the distinct autotomy topography observed. This represents a compelling hypothesis for future ultrastructural and neural tracing studies.

The enhanced p-p38 activation observed in the DRGs of TG2 KO mice provides a potential molecular link to the altered pain phenotype. p38 MAPK is a well-established signaling molecule, activated in both neurons and glia, that mediates inflammatory and neuropathic pain [27, 28]. Its heightened activity in TG2 KO animals suggests that TG2 normally modulates this pathway, and its absence leads to dysregulated p38 signaling in response to injury, contributing to the distinct pain behavior. While microglial activation (Iba1 expression) was unaffected by TG2 status, the specific mechanism by which TG2 influences p38, potentially through integrin-ECM interactions or regulation of upstream kinases, warrants further investigation.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The observation period was restricted to 14 days post-injury, longer-term effects of TG2 KO remain unexplored. As only male mice were used, the generalizability of the findings to females is uncertain, given established sex differences in pain processing. Although sample sizes were sufficient for key behavioral outcomes, they were modest for some cellular analyses. Finally, while the constitutive KO model establishes a clear phenotype, developmental or compensatory adaptations cannot be ruled out. Complementary pharmacological studies using selective TG2 inhibitors in adult animals would help determine if acute TG2 inhibition can modify established neuropathic pain, thereby strengthening its translational relevance as a therapeutic target.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that TG2 is dispensable for sensory neuron survival in the PNS but is a critical determinant of neuropathic pain behavior. This dissociation suggests that therapeutic strategies targeting TG2 may hold greater promise for pain management than for neuroprotection following peripheral nerve injury.

CNS: central nervous system

DRG: dorsal root ganglion

ECM: extracellular matrix

IR: immunoreactive

KO: knockout

L: lumbar

NP: neuronal profile

PI: propidium iodide

PNS: peripheral nervous system

p-p38: phospho-p38 MAPK

SNI: spared nerve injury

TG2: transglutaminase 2

WT: wild-type

We thank Profs. Tomas Hökfelt and Sandra Ceccateli (Department of Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden) for their generous supply of antibodies and valuable advice. We also express our gratitude to Prof. George Melino and his group (Laboratory of Biochemistry, Department of Experimental Medicine and Biochemical Sciences, University of Rome, Italy) for generously providing the transgenic mice and technical assistance.

GWL: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft. XQP: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis. LH: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis. XHM: Methodology, Formal analysis. CL: Conceptualization, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft. TJSS: Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

All procedures were approved by the Northern Stockholm Animal Ethics Committee (Norra Djurförsöksetiska Nämnd; approval number N150/11).

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

This work was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council, the China Scholarship Council (CSC) awarded to Dr. Chuang Lyu (HIT, 2013), the H. Monrad-Krohn og hustru Alette Monrad-Krohns legat Foundation to Dr Tie-Jun Sten Shi, Lanzhou University Research Start-up Fund (2020) to Dr. Tie-Jun Shi, and Heilongjiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation [PL2025H075] to Dr. Gong-Wei Lyu. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 204

Download: 15

Times Cited: 0