Affiliation:

NGO Praeventio, Tartu 50407, Estonia

Email: katrin.sak.001@mail.ee

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0736-2525

Explor Neurosci. 2026;5:1006122 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/en.2026.1006122

Received: November 24, 2025 Accepted: January 06, 2026 Published: January 22, 2026

Academic Editor: Weilin Jin, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, China

The article belongs to the special issue Current Approaches to Malignant Tumors of the Nervous System

Flavonoids are a large class of natural polyphenolic substances ubiquitously synthesized in the plant kingdom. When entering the human body, these compounds can exert a wide range of biological activities, including immunomodulatory, antiinflammatory, and anticancer effects. Over the recent years, the mechanisms underlying these actions have become increasingly clear, also indicating the important involvement of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), such as adenosine receptors, in signal transduction networks. In this perspective article, the potential role of flavonoids as adenosine receptor antagonists on the development, progression, and spread of glioblastoma is discussed, blocking the tumor-promoting and immunosuppressive actions of elevated levels of endogenous adenosine. Therefore, flavonoids can be considered as structural leads for developing novel antiglioblastoma agents, applied either alone or as boosters of chemo- or immunotherapy to improve the quality of life and outcome of patients. The importance of these studies is, in turn, emphasized by the current lack of effective treatment strategies for this highly aggressive and fast-growing brain tumor, associated with poor prognosis.

Although brain tumors constitute 1.6% of all diagnosed cancers worldwide, over the last decades, a progressive increase in their incidence has been reported [1, 2]. Glioblastoma is the most common, aggressive, and malignant form of primary brain tumors, characterized by rapid growth and invasion into adjacent brain regions, resulting in a high relapse rate [2–5]. The mean survival time of this grade IV tumor has remained just around 15 months, with a five-year survival rate of about 5%, showing no significant improvements during the last 30 years [2–5].

Due to its poor prognosis, several efforts have been made to better understand the mechanisms underlying glioblastoma pathogenesis [4]. This heterogenous tumor consists of both genetically diverse tumor cells and cancer stem cells [2, 5]. Tumor microenvironment also plays an important role in the development of glioblastoma, characterized by hypoxic niches where the oxygen deficiency promotes production of various proangiogenic and growth factors, stimulating the progression, migration, and invasion of malignant cells [2, 4, 5]. In fact, whereas in the normal brain tissue, oxygen concentrations range between 2.5% to 12.5%, in malignant tumors, these levels remain at only 0.1–2.5% [5]. Moreover, glioblastoma microenvironment is also characterized by its immune-escaping nature, due to the production and release of various immunosuppressive cytokines and chemokines by various inflammatory components [2, 4].

Unfortunately, there are currently no efficient therapeutic approaches for glioblastoma. The standard of care consists of surgical excision and radiotherapy in conjunction with temozolomide, a DNA-alkylating drug, often administered in a chronotherapeutic regimen [2, 3, 5]. Although several new chemotherapeutic agents have recently been developed, none of them have yet entered routine clinical practice [3]. There are some unique challenges that make treating glioblastoma particularly difficult, including the critical roles of the central nervous system in maintaining quality of life and the presence of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which is only poorly permeable or impermeable to most chemotherapeutic drugs [2, 3].

One of the newest glioblastoma treatment strategies still under development focuses on targeting adenosine receptors (ARs), thereby preventing the effects of extracellular adenosine [2]. In the present perspective, AR antagonism is highlighted as a possible mechanistic link between plant-derived flavonoids and their potential antiglioblastoma effects, proposing these phytochemicals as both dietary modulators and structural leads for future therapeutic development.

Adenosine is an endogenous purine nucleoside composed of an adenine base linked to a ribose sugar moiety. Its structural formula is depicted in Figure 1. This small autacoid is capable of performing multiple physiological actions in different systems and organs following binding to its receptors, A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 ARs [2, 6–8]. As an extracellular messenger, adenosine can regulate various processes such as neurotransmission, vascular function, immune responses, and inflammation, being involved in neurodegenerative diseases, psychiatric disorders, heart issues, lung injuries, eye diseases, and cancers [2, 6, 9, 10].

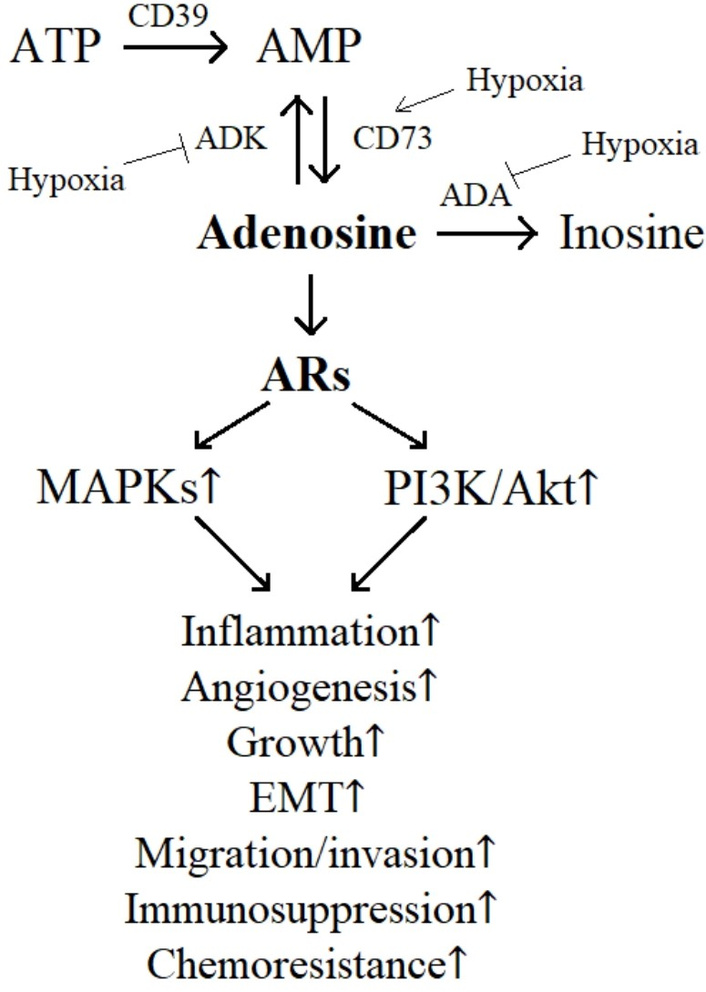

Adenosine is produced in the extracellular environment through the breakdown of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by a cascade driven by two ectoenzymes, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 (CD39) and ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) [2, 4–6]. When adenosine levels become excessive, the body can reduce them by activating adenosine kinase (ADK) that converts adenosine back to adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and/or adenosine deaminase (ADA) that deaminates adenosine into inosine. Both of these processes require sufficient levels of oxygen to function efficiently [6, 7]. However, in hypoxic areas characteristic to tumor microenvironment, these two enzymes, ADK and ADA, may not work properly leading to the accumulation of extracellular adenosine, supporting the growth and survival of neoplasms [2, 6]. In this way, the oxygen-dependent regulation of adenosine metabolism plays an important role in malignant progression [5, 6]. Moreover, elevated levels of both CD39 and CD73 expression have been detected in several cancer types, including glioma and glioblastoma, correlating with a poor prognosis of patients [2, 4, 6]. The regulation of adenosine turnover is briefly illustrated in Figure 2. Other factors also contributing to the adenosine production around tumors include the inflammatory microenvironment and tissue damage [2, 6]. As a result, the concentrations of adenosine in areas surrounding tumors can reach up to high micromolar levels, compared to only 30–200 nM in normal tissues [4, 5].

Effects of extracellular adenosine on glioblastoma progression. ADA: adenosine deaminase; ADK: adenosine kinase; Akt: protein kinase B; AR: adenosine receptor; CD39: ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1; CD73: ecto-5′-nucleotidase; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; MAPKs: mitogen-activated protein kinases; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Among the four AR subtypes, A1AR and A2AAR are known as high-affinity receptors being activated by physiological levels of adenosine. However, the activation of low-affinity A2BAR and A3AR requires significantly higher (micromolar) concentrations of adenosine, available at tumor microenvironment [2, 4, 5, 11]. All these receptors are expressed in different cell types within the central nervous system, including both glial cells and neurons but also immune cells, with an increased expression level in malignant conditions, such as glioblastoma [2, 5–7, 10].

ARs are GPCRs which bind to different G proteins and modulate different intracellular signaling cascades, i.e., A2AAR and A2BAR couple to Gs protein leading to stimulation of adenylate cyclase, whereas A1AR and A3AR couple to Gi/0 protein inducing inhibition of adenylate cyclase [2, 6]. Nevertheless, these pathways ultimately converge towards increased phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) [2, 4–7] (Figure 2). As a result, high levels of extracellular adenosine under hypoxic conditions can promote the growth, aggressiveness, and spread of glioblastoma by activating the processes of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), migration, and invasion of malignant cells [2, 4–7]. In addition, adenosine can also encourage the growth of endothelial cells and the formation of new blood vessels through its proangiogenic action, thereby in turn boosting the progression of cancerous neoplasm [2, 4, 6]. Moreover, adenosine can act on immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, making them less effective at targeting and destroying malignant cells, i.e., inducing immunosuppression, further supporting the glioblastoma growth and metastasis [2, 4, 6, 7]. Indeed, adenosine has been shown to inhibit the function of natural killer cells and cytotoxic T cells in the microenvironment of glioblastoma, helping the tumor to evade the immune system [2]. Therefore, suppressing the action of extracellular adenosine through blocking its membrane receptors may exhibit both direct antitumor activities but also antiangiogenic, antiinflammatory, and immunotherapeutic effects, possibly improving prognosis of glioblastoma patients [2, 4–7, 12].

Increasing evidence about the involvement of adenosine signaling in brain tumors has encouraged research into the development of ARs antagonists as novel potential agents for the treatment of glioblastoma, applied either alone or in combination with standard chemotherapeutic or immunotherapeutic drugs [2, 6, 7]. The currently available antagonists for ARs can be broadly divided into two groups: xanthine derivatives and non-xanthine derivatives [2, 9, 11]. The first group includes compounds obtained from modifications of the two main natural alkaloids, caffeine and theophylline, showing some affinity for all AR subtypes [2, 7, 9, 11–13]. The second group contains structurally diverse substances, such as nitrogen heterocycles and non-nitrogen heterocycles, that are designed to selectively bind to specific AR subtypes and inhibit downstream signaling pathways [2, 7, 11]. However, developing highly potent AR-targeting drugs has still remained a significant challenge, due to the weak photostability and poor water solubility of xanthines, as well as a relatively low selectivity and/or specificity of many non-xanthine antagonists, besides concerns related to their safety [6, 9, 12, 14, 15].

Interestingly, in addition to xanthines, representatives of another large class of plant-derived compounds, flavonoids, have also been found to exert considerable inhibitory activities on different AR subtypes. Flavonoids are low-molecular-weight polyphenolic substances synthesized by plants in response to different biotic and abiotic stresses, providing defense against various pathogens, pests, and harmful environmental conditions [16, 17]. Their basic skeleton is presented in Figure 1. The roles of these phytochemicals in the human body are also well accepted, exerting a wide range of biological activities, including antioxidant, immunomodulatory, antiinflammatory, neuroprotective, and anticancer effects [18, 19]. In recent years, understanding of molecular mechanisms of intracellular processes regulated by different flavonoids has significantly increased, indicating the involvement of GPCRs, such as ARs, in signal transduction networks [12, 20, 21]. It is just a surprising historical coincidence that the Hungarian biochemist Albert Szent-Györgyi, who first identified the biological actions of adenosine in 1929, also discovered the biological effects of flavonoids in humans in the 1930s [9, 22]. The main data on the ability of flavonoids to compete for ARs radioligand binding using subtype-selective ligands are summarized in Table 1. In these studies, different experimental models have been used, measuring the affinity of flavonoids to both human, rat and guinea pig ARs [9–12, 21, 23, 24]. It is evident that some species-specific differences may appear when comparing the corresponding results [9, 11, 25]. Also, despite several attempts to present structure-activity relationships, there is still too little data to draw definitive universal conclusions about the impact of specific structural features on the activity of flavonoids in inhibiting AR subtypes [9, 11, 12, 21, 24]. Nevertheless, it is evident that several common natural flavonoids, such as flavonols galangin and kaempferol, may have antagonistic properties towards ARs even at their low micromolar levels.

Affinities of a set of flavonoids in radioligand binding assays at A1, A2A, and A3 ARs.

| Flavonoid | pKi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1AR | A2AAR | A3AR | |||

| vs [3H]-DPCPX | vs [3H]-PIA | vs [3H]-NECA | vs [3H]-CGS21680 | vs [125I]-AB-MECA | |

| 3-methoxyflavone | 6.04a | 5.29b | |||

| 3′,4′-dihydroxyflavonol | 5.57a | 6.33b | |||

| 3,5,6,7,8,3′,4′-heptamethoxyflavone | 4.80c | 4.40d | |||

| 3,5,7,3′,4′-pentamethoxyflavone | 4.76c | 4.34d | |||

| 5,7-dimethoxyflavone | 5.51a | ||||

| Apigenin | 5.52c | 5.12d | |||

| Biochanin A | 4.46c | ||||

| Cirsimarin | 5.49e | ||||

| Cirsimaritin | 5.92c | 5.52d | 5.76f | ||

| Daidzein | 4.63c | ||||

| Flavanone | < 4.00g | 4.49c | 4.30f | ||

| Flavone | 5.16g | 5.48c | 5.46d | 4.77f | |

| Galangin | 6.05a | 6.06c | 6.02d | 5.50f, 4.37h | |

| Genistein | 4.67g | 4.90c | > 4.00f | ||

| Hexamethylmyricetin | > 6.00c | 4.79f | |||

| Hispidulin | 5.79c | 5.19d | |||

| Kaempferol | 5.81a, 4.94g | 6.00b | |||

| Morin | 4.86c | 4.76d | > 4.00f | ||

| Naringenin | 4.53g | ||||

| Nobiletin | 5.43c | 4.67d | |||

| Pentamethylmorin | 4.56c | 4.33d | 5.58f | ||

| Prunetin | > 4.00c | ||||

| Quercetin | 5.33g | 5.61c | 5.16d | ||

| Rhamnetin | 5.86f | ||||

| Sakuranetin | 5.09c | 4.45d | 5.47f | ||

| Sinensetin | 6.06c | 4.94d | |||

| Swertisin | 4.10i | ||||

| Tangeretin | 5.35c | 4.63d | |||

| Taxifolin | > 5.00c | 4.47f | |||

| Tetramethylkaempferol | 6.03a | 5.97c | 5.47f | ||

| Tetramethylscutellarein | 5.84c | 4.84d | 5.35f | ||

| Trimethoxyflavone | 6.29c | 5.19d | 5.92f | ||

a Rat whole brain membranes [12]. b Rat striatal membranes [12]. c Rat brain membranes [9, 11, 24]. d Rat striatal membranes [9, 11, 24]. e Rat forebrain membranes [23]. f Human brain A3AR expressed in HEK-293 cells [9, 11]. g Guinea-pig cerebral cortex particulate preparations [21]. h Rat brain A3AR expressed in CHO cells [9, 11]. i Human A1AR expressed in CHO cells [10]. AB-MECA: N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-(N-methyluronamide); AR: adenosine receptor; CGS21680: 2-[[4-(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl]ethylamino]-5′-(N-ethylcarbamoyl)adenosine; DPCPX: 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine; NECA: 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine; PIA: N6-phenylisopropyladenosine.

As flavonoids form an integral part of the human diet, these plant-derived compounds represent an important source of ARs antagonists. The plasma levels achieved after the oral intake of these phytochemicals can reach the high nanomolar range [26, 27]. Considering the submicromolar affinities of some dietary flavonoids towards AR subtypes (Table 1), there is no doubt that these substances may be involved in the regulation of ARs, blocking the effects of endogenous adenosine. In other words, it is evident that ARs antagonism may be an important mechanism in the biological activities reported for flavonoids, including their anticancer effects [9, 24]. Given the critical role of ARs in glioblastoma, as described above, the regular intake of food products rich in specific flavonoids may be valuable in the prevention of this devastating disease, suppressing its progression and spread. In this context, it is very important to emphasize the ability of flavonoids to penetrate the BBB, an absolutely necessary condition for their activities on brain tumors [12, 13]. Moreover, specific flavonoids could be considered also as molecular leads for developing novel drug candidates for the treatment of glioblastoma, applied either alone or as boosters of chemotherapy (temozolomide), immunotherapy or even radiotherapy, or nanotechnology therapy approach [2, 6, 7, 28–30]. Therefore, in the future, research into this large group of polyphenolic compounds should definitely be continued to identify new structures with higher antiglioblastoma potential. In parallel, the bottlenecks related to the use of flavonoids, i.e., their poor water solubility and low bioavailability in the human body must also be resolved before initiating clinical trials in glioblastoma patients. The urgency of these works is further underscored by the increasing mortality rate of glioblastoma, despite the implementation of current standard treatments.

ADA: adenosine deaminase

ADK: adenosine kinase

AR: adenosine receptor

BBB: blood-brain barrier

CD39: ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1

CD73: ecto-5′-nucleotidase

GPCRs: G protein-coupled receptors

KS: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. The author read and approved the submitted version.

Katrin Sak, who is the Editorial Board Member and Guest Editor of Exploration of Neuroscience, had no involvement in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 398

Download: 14

Times Cited: 0

Zohreh Khosravi Dehaghi

Maria Ciscar-Fabuel ... Andreu Gabarros-Canals

Maria Ciscar-Fabuel ... Andreu Gabarros-Canals

Julius Mulumba ... Yong Yang

Adam H. Lapidus, Malaka Ameratunga