Affiliation:

1Department of Meat and Dairy Technology, Kazan National Research Technological University, 420015 Kazan, Russian Federation

Email: hrustik@yandex.ru

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3428-967X

Affiliation:

2Department of Food Biotechnology, Kazan National Research Technological University, 420015 Kazan, Russian Federation

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2211-8742

Affiliation:

3Department of Food Production Technology, Kazan National Research Technological University, 420015 Kazan, Russian Federation

Affiliation:

4Bakery development department, Puratos group Russia, 142121 Podolsk, Russian Federation

Explor Foods Foodomics. 2026;4:1010112 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eff.2026.1010112

Received: November 05, 2025 Accepted: January 03, 2026 Published: February 09, 2026

Academic Editor: Filomena Nazzaro, CNR, Italy

Aim: Probiotic microorganisms, primarily lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and bifidobacteria, are able to solve most of the problems of animal by-products that hinder their use in the food industry. The most important property of LAB is their antagonistic activity against pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms. The aim of the study is to compare the antimicrobial activity of microorganisms from commercial starters, medicinal preparations, and newly isolated strains. It is important to evaluate two alternative methods for determining antimicrobial activity in terms of their interchangeability.

Methods: A total of 11 microorganisms and consortia from various sources were studied, including five newly isolated strains. Their antagonistic activity against 8 strains of pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms was evaluated by two in vitro methods: agar diffusion and co-cultivation. Their interchangeability was assessed using the linear Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results: The 12th hour of cultivation, corresponding to the maximum specific growth rate of the studied newly isolated strains and consortia were determined and used to take a supernatant sample for co-cultivation with test pathogens. Of the studied cultures, lactobacilli and pediococci showed the greatest antagonistic activity against the tested pathogens, while Staphylococcus spp. showed minimal activity.

Conclusions: The highest inhibition index was observed in consortia containing Lactobacillus and Pediococcus. The antagonistic activity of the newly isolated strains is lower than that of meat starter cultures and medicinal products. The evaluation of the comparability of analytical methods for determining antimicrobial activity demonstrates a high positive correlation of the results, but requires further research to resolve the issue of their interchangeability.

An urgent global problem is the effective and rational management of secondary meat processing resources, the number of which in 2024 amounted to about 155 million tons [1, 2]. They are considered as raw materials for the production of food, medicines, animal feed, cosmetics [3, 4], pharmaceuticals, and biologically active peptides with antihypertensive, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antimicrobial [5, 6], opioid, and antithrombotic effects [7–9]. Preference is given to technologies for products with high demand, low costs, and minimal environmental impact, which ensure the sustainable development of the meat industry and the transition to bioeconomics, and lagging behind in this issue leads to resource loss, increased recycling costs, and environmental problems [10, 11]. Similar programs are being developed in China [10] and Kazakhstan [11]. Meat by-products have a high content of protein, essential amino acids, lipids, biologically available iron, potassium, phosphorus, sulfur, and sodium [12, 13], so they can be used to overcome malnutrition and anemia [14, 15].

The main problem with the use of by-products is their high microbial contamination, which is observed in 15–40% of carcasses of slaughtered animals and can range from 1.42 to 1.82 Lg CFU/g [16].

The authors note certain obstacles to the use of by-products related to their appearance and smell. The characteristics “unsightly appearance”, “viscous”, “fluffy texture”, and “unpleasant odor” were used to describe the sensations, especially in relation to raw offal. Negative olfactory characteristics have a stronger effect on food perception than on taste [17, 18]. This odor is created by 16 characteristic volatile compounds, which include E,E-2,4-nonadienal, E,E-2,4-decadienal-1-al, hexanal, (E)-2-octenal and decyl aldehyde found in the heart; 1-nonanol, ethyl hexanoate, 2-octanone and dodecyl aldehyde in the liver; 3-heptylacrolein in the lungs; heptaldehyde, octanal, p-cresol and 1-nonanal in the rumen; and 1-octen-3-ol and E-2-nonenal in the intestine [17]. To eliminate unpleasant odors in by-products, they are cleaned, boiled, soaked in alkaline or phosphate buffer solutions, and washed [19], soaked in mustard solution, fermented with kefir grains [20].

The main component of by-products is collagen, which has both positive biological and functional properties (high moisture-binding, moisture-retaining and texturizing properties, as well as the content of biologically active peptides) and an unbalanced composition of amino acids with an excess of glycine, proline and hydroxyproline, but with a lack of methionine, isoleucine, threonine, cysteine and tryptophan [21]. Thus, collagen has a low ratio of essential and nonessential amino acids [22, 23] and a low digestibility index, which limits its use in food systems [24]. This can be improved by moving the pH value away from its isoelectric point (pH 6.0 to 6.75), which improves water binding and facilitates fermentolysis.

After disinfection, deodorization, increased digestibility, drying, and grinding it is proposed to obtain and use lyophilized powders from the spleen, lungs and heart, which increase moisture binding and emulsification of meat systems, increase the content of copper and zinc, reduce fat content, improve texture and stability, and also increase the shelf life of meat products without deterioration of taste. These technologies make meat offal a promising additional raw material for the production of fermented sausages, cutlets, emulsified products, minced meat, and pastes [13, 25–29].

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are able to solve the problems of by-products due to their adaptability, safety, biological activity, biotechnological value, and high antagonistic activity; therefore, they are used in food and agricultural biotechnology for the production of fermented meat products and animal feed with functional and probiotic properties [30, 31]. Bifidobacteria are also known as probiotics; they are resistant to acids and bile, synthesize vitamins and amino acids, and have antianemic, anti-rickety, and anti-allergic effects. In addition, they produce neuroactive compounds such as gamma-aminobutyric acid, which improve mental health by reducing anxiety, depression, and stress [32–35].

The antagonistic activity of LAB and bifidobacteria is manifested in their ability to suppress the growth of technically harmful and pathogenic microorganisms by such methods as pH reduction, synthesis of organic acids, antibiotics, hydrogen peroxide, diacetyl, reuterin, and bacteriocins [33–40].

Effective multi-strain probiotics not only suppress pathogenic microorganisms more effectively and balance the intestinal microflora [41], but also have anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, hypoglycemic, and hypocholesterolemic effects, and improve the quality of the final meat product by synthesizing metabolites that form a favorable taste and aroma (acids, aromatic substances, polysaccharides) [42–45].

These achievements confirm the ability of lactic acid fermentation to enhance the safety, biological value, and sensory properties of meat offal.

This article presents the results of comparing a number of bacterial strains of various genera and origin according to one of the important indicators—antagonistic activity against opportunistic and pathogenic microorganisms. Another unresolved task is to select simple and affordable methods for measuring antagonistic activity from a large number of possible alternatives, and to justify their interchangeability.

Meat starters were freeze-dried bacterial commercial starter cultures for the production of sausages: mono-strain starter Christian Hansen Safe Pro B-LL-20, multi-strain starters Christian Hansen Bactoferm F-SC-111, Schaller Start Star, and Danisco Texel DCM-1. Declared composition of meat starters tested is shown in Table 1.

Declared composition of meat starters tested.

| Name of meat starters | Composition |

|---|---|

| Christian Hansen Safe Pro B-LL-20 | 100% Pediococcus acidilactici |

| Christian Hansen Bactoferm F-SC-111 | Staphylococcus carnosus, Latilactobacillus sakei |

| Schaller Start Star | Latilactobacillus curvatus, Pediococcus pentosaceus, Staphylococcus carnosus |

| Texel DCM-1 | Staphylococcus carnosus, Staphylococcus xylosus |

Medicinal preparations Lactobacterin and Bifidobacterin are Russian probiotic preparations used to restore intestinal microflora. They are lyophilized biomass of live bacteria Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, respectively, and are produced in accordance with regulatory documents [46]. Their declared composition is shown in Table 2.

Declared composition of medicinal preparations Lactobacterin and Bifidobacterin.

| Name of medicinal preparations | Composition |

|---|---|

| Lactobacterin | 100% Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 8P-A3 |

| Bifidobacterin | 100% Bifidobacterium bifidum |

Five new strains were isolated from fermented dairy products and silage and are stored in the collection of the Department of Food Production Technology at Kazan National Research Technological University: Lacticaseibacillus casei 1, Lactiplantibacillus fermentum 13, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum (L. plantarum) 1, Lactobacillus acidophilus 9, Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. tolerans 6.

Bacterial opportunistic and pathogenic test-strains were provided by the Kazan Scientific Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology (KNIIEM) of the Russian Federal Service for Supervision of Consumer Rights Protection and Human Welfare (Rospotrebnadzor): gram-positive bacteria Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes; gram-negative bacteria Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella L1, Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium.

In this study, we used recommended elective nutrient media as well as media common in industrial practice:

Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) medium of the following composition (g/L): peptone: 10, yeast extract: 4, glucose: 20, tween-80: 1, potassium phosphate: 2, sodium acetate: 5, triammonium citrate: 2, magnesium sulfate: 0.2, manganese sulfate: 0.05, distilled water :1 liter for the cultivation of LAB;

Blaurock elective medium of the following composition (g/L): glucose: 5.0, sodium chloride: 5.0, soluble starch: 1.0, peptone: 23.0, cysteine: 0.3, agar-agar: 15.0, distilled water: 1 liter for the cultivation of bifidobacteria;

Whey-based medium for the cultivation of LAB and bifidobacteria;

Skim milk medium for the cultivation of LAB and bifidobacteria. The pH of the media was adjusted to the optimal value of 6.8 ± 0.2 by adding 0.1 N NaOH;

Meat peptone broth (MPB) for the cultivation of the opportunistic and pathogenic bacteria under aerobic conditions at a temperature of 37 ± 2°C;

Meat peptone agar (MPA) for the cultivation of continuous culture of the opportunistic and pathogenic bacteria under aerobic conditions at a temperature of 37 ± 2°C;

Isotonic solution for the freeze-dried starter cultures rehydration.

The concentration of biomass X (CFU/mL) in the nutrient medium was determined by direct counting on selective media. LAB cultures were sown on MRS agarized medium, bifidobacteria on Blaurock agarized medium [47, 48]. The optical-density-based method of biomass determination was used in the case of co-cultivation [49].

The specific growth rate µ, h–1, was calculated using Equation 1:

where µ is the specific growth rate, h–1; X is biomass concentration (CFU/mL) at time t. The integral form of Equation 1 allows us to determine the average specific growth rate over a period of time from t1 to t2 [50], as shown in Equation 2:

where µaver is the average specific growth rate, X1 and X2 are the concentrations of biomass at the time moments t2 and t1.

The main methods for assessing antagonistic activity include agar diffusion [51–53], co-cultivation [44, 52, 53], transverse stripes or strokes, poisoned medium, inhibition kinetics, agar and broth dilution, resazurin assay [54–57], gradient diffusion [44, 50], bioautography [58, 59, 60], flow cytometry [60], bioluminescence [61, 62], and impedance analysis [63, 64]. The latter methods are modern, rapid, and reliable but costly and equipment-dependent [60].

In this work, the antagonistic activity of microbial strains and meat starters cultures was evaluated by two in vitro methods: agar diffusion (disk agar diffusion) and co-cultivation in liquid media.

Using the agar diffusion method, the studied bacterial cultures were seeded in Petri dishes by a deep method into an agarized MRS medium and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. Then, an agar block with a grown culture of LAB and bifidobacteria was cut out with a sterile cork drill and installed in another Petri dish on the surface of the agar medium seeded with a continuous culture of the opportunistic and pathogenic bacteria in aerobic conditions at 37°C. The cup was kept in a refrigerator for 1 h to diffuse inhibitory compounds from the block into the agar layer and avoid premature growth of the test culture. Further incubation was carried out at a temperature of 37°C for 24 h. The degree of antagonistic activity of the tested starter cultures was judged by the size of the growth inhibition zone around the agar block.

The antagonistic activity index (AAI) was calculated to compare the antagonistic activity of strains according to the following criteria: the diameter of the growth suppression zone of more than 24.1 mm corresponds to very strong suppression and AAI is estimated at 4 points; 16.1–24 mm: strong suppression, 3 points; 8.1–16 mm: moderate suppression, 2 points; 0–8 mm: weak suppression or absence of suppression, 1 point [50, 51, 65].

Using the co-culture method, all probiotic bacteria were cultured in 3 mL of MRS liquid medium at 37°C until reaching the exponential growth phase. The time to achieve it is determined experimentally, in a preliminary series of experiments.

The grown probiotics in the exponential growth phase were treated with chloroform (0.1 mL per sample) for 40 minutes. Bacterial cells were precipitated by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 3,000 g, 0.4 mL of the aqueous phase was taken from the upper part of the supernatant, and introduced into tubes with 0.1 mL of a daily suspension of cultures of pathogenic microorganisms. A MRS medium (0.4 mL) pretreated with chloroform (0.1 mL) was used as a control. The experimental and control samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation, 2.5 mL of MPB was added to each sample and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The biomass concentration was determined as indicated above. The antagonistic activity of all studied microbial cultures was judged by a decrease in the optical density of the culture of pathogenic microorganisms compared with the control variant, in which the studied objects were absent. The degree of growth inhibition of pathogens was expressed as the growth inhibition index (GII), which was calculated using Equation 3:

where Xcontr and Xexp are the concentrations of biomass under control conditions (without antagonists) and under experimental conditions (in the presence of antagonists), respectively.

Data were subjected to statistical analysis by using Statistica 7.0 software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Each experiment was performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. A group of data was considered homogeneous if its standard deviation σ did not exceed 13% with significance of P < 0.05. To assess the correspondence of the antagonistic activity indicators obtained by two alternative methods, the linear correlation between the two data sets was determined in the form of the Pearson correlation coefficient.

The antagonistic activity of the tested probiotic microorganisms is determined by their contact with strains of pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms, either directly in the method of co-cultivation, or indirectly through diffusion in agar. It is important that probiotics are in an active state, which is observed in the exponential growth phase. To determine the time limits of the exponential growth phase, we conducted preliminary periodic cultivation on the above-mentioned nutrient media (section “Nutrient media”). The results are shown in Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4.

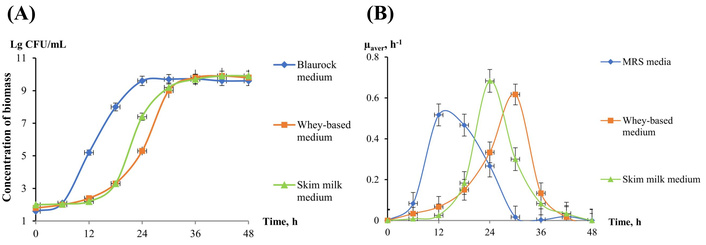

Dynamics of B. bifidum (Bifidobacterin) growth in the different liquid media. (A) Concentration of biomass, CFU/mL; (B) average specific growth rate µ, h–1. MRS: Man-Rogosa-Sharpe; B. bifidum: Bifidobacterium bifidum.

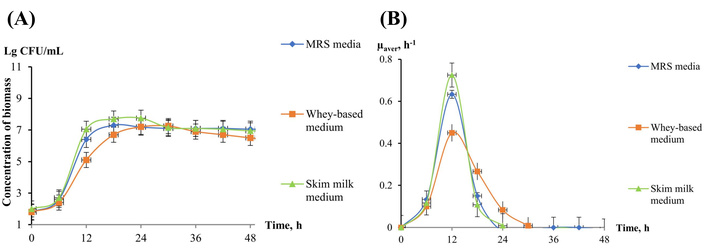

Dynamics of L. plantarum 8P-A3 (Lactobacterin) growth in the different liquid media. (A) Biomass concentration, CFU/mL; (B) average specific growth rate µ, h–1. MRS: Man-Rogosa-Sharpe; L. plantarum: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum.

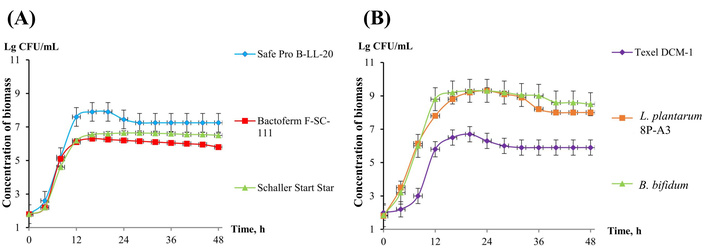

Dynamics of biomass of meat starter and medicinal preparations biomass X, CFU/mL, when cultured in the Whey-based medium. (A) Christian Hansen Safe Pro B-LL-20, Christian Hansen Bactoferm F-SC-111, Schaller Start Star; (B) Texel DCM-1, L. plantarum 8P-A3, B. bifidum. B. bifidum: Bifidobacterium bifidum; L. plantarum: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum.

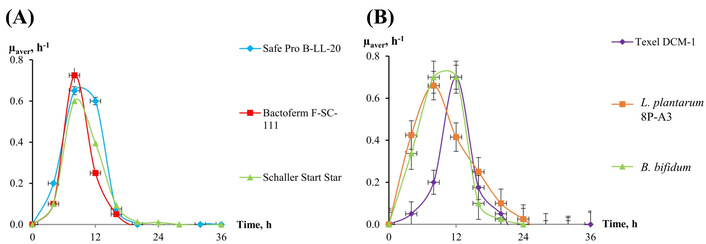

Average specific growth rates µ, h–1, of meat starters and medicinal preparations biomass in the Whey-based medium. (A) Christian Hansen Safe Pro B-LL-20, Christian Hansen Bactoferm F-SC-111, Schaller Start Star; (B) Texel DCM-1, L. plantarum 8P-A3, B. bifidum. B. bifidum: Bifidobacterium bifidum; L. plantarum: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum.

Bacteria from the medicinal preparations Bifidobacterium bifidum (B. bifidum) and L. plantarum 8P-A3 were grown on three different media. The data show that the duration of the exponential phase of their growth depends on the type of nutrient medium. For B. bifidum, it lasts from 12 to 30 h of cultivation (Figure 1A), for L. plantarum 8P-A3, from 6 to 18 h of cultivation (Figure 2A).

The maximum specific rate of their growth also varied. For B. bifidum, the highest specific growth rate was 0.68 h–1 on Skim milk medium, 0.62 h–1 on Whey-based medium, and 0.57 h–1 on MRS medium, and the time to reach the maximum growth rate was 24, 30, and 12 h, respectively (Figure 1B). For L. plantarum 8P-A3, the maximum growth rate was 0.73, 0.45, and 0.63 h–1 on Skim milk medium, Whey-based medium, and MRS medium, respectively (Figure 2B), and the time to reach the maximum growth rate did not depend on the nutrient medium and was 12 h.

Whey-based medium was chosen as the most acceptable one, and bacterial biomass from meat starters was grown only in this medium. The duration of the exponential phase is quite close, ranging from 0 to 16 h (Figure 3), and the maximum rate is observed at 6–12 h of growth (Figure 4).

Based on the results obtained, subsequent experiments to determine antagonistic activity by co-cultivation were carried out on an identical MRC medium for all bacterial cultures, and biomass samples were taken after 12 h of cultivation.

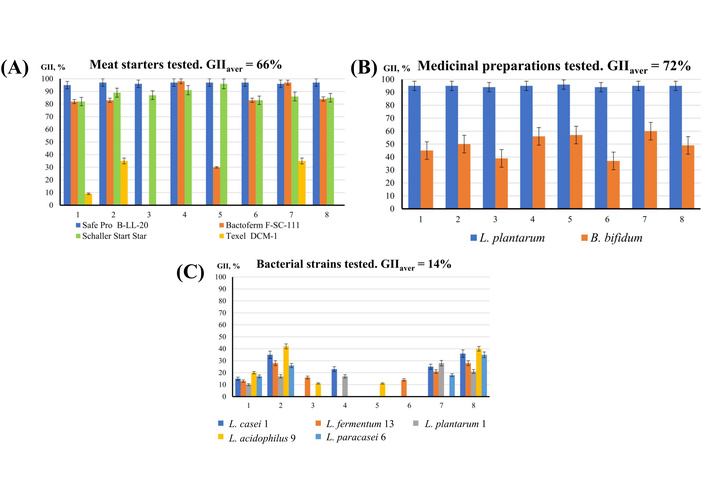

The results of co-cultivation and determination of the GII, calculated as described in the section “Antagonistic activity determination”, are shown in Figure 5.

Growth inhibition index (GII). (A) GII of the meat starters (method of co-cultivation); (B) GII of the medicinal preparations Lactobacterin and Bifidobacterin (method of co-cultivation); (C) GII of the newly isolated strains (method of co-cultivation). Pathogens tested: 1: Serratia marcescens; 2: Escherichia coli; 3: Klebsiella L1; 4: Staphylococcus epidermidis; 5: Staphylococcus aureus; 6: Listeria monocytogenes; 7: Bacillus сereus; 8: Salmonella typhimurium. L. plantarum: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 8P-A3; B. bifidum: Bifidobacterium bifidum; L. casei 1: Lacticaseibacillus casei 1, L. fermentum 13: Lactiplantibacillus fermentum 13; L. plantarum 1: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 1; L. acidophilus 9: Lactobacillus acidophilus 9; L. paracasei 6: Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. tolerans 6.

The total GII values are shown in Table 3, the cells of which are colored in a three-color range (red-yellow-green) in accordance with the GII value. The best samples with maximum activity are highlighted in green, and the worst samples with minimum activity are highlighted in red.

The growth inhibition index (GII) of newly isolated strains, preparations, and starters (method of co-cultivation).

| Starters, preparations, and newly isolated strains | Test cultures | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serratia marcescens | Escherichia coli | Klebsiella L1 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Staphylococcus aureus | Listeria monocytogenes | Bacillus сereus | Salmonella typhimurium | Average | |

| Meat starters | |||||||||

| Safe Pro B-LL-20 | 95 | 97 | 96 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 96 | 97 | 97 |

| Bactoferm F-SC-111 | 82 | 83 | 0 | 98 | 30 | 83 | 97 | 84 | 70 |

| Schaller Start Star | 82 | 89 | 87 | 91 | 96 | 83 | 86 | 85 | 87 |

| Texel DCM-1 | 9 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 10 |

| Medicinal preparations | |||||||||

| Lactobacterin | 95 | 95 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 94 | 95 | 95 | 95 |

| Bifidobacterin | 45 | 50 | 39 | 56 | 57 | 37 | 60 | 49 | 49 |

| Newly isolated strains | |||||||||

| L. casei 1 | 15 | 35 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 36 | 17 |

| L. fermentum 13 | 13 | 28 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 15 |

| L. plantarum 1 | 10 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 21 | 12 |

| L. acidophilus 9 | 20 | 42 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 16 |

| L. paracasei 6 | 17 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 35 | 12 |

| Average | 44 | 54 | 31 | 43 | 35 | 37 | 51 | 52 | |

L. casei 1: Lacticaseibacillus casei 1; L. fermentum 13: Lactiplantibacillus fermentum 13; L. plantarum 1: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 1; L. acidophilus 9: Lactobacillus acidophilus 9; L. paracasei 6: Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. tolerans 6.

As can be seen from the data in Figure 5 and Table 3, all the bacterial cultures studied inhibited the growth of test strains to one degree or another. The maximum activity was observed in starter Safe Pro B-LL-20 and preparation Lactobacterin. They suppressed the growth of all the test strains by 95–97% and 94–96%, respectively. Schaller Start Star starter culture also showed a high degree of inhibition of the test strains, by an average of 87%. Bactoferm F-SC-111 starter did not inhibit the growth of Klebsiella L1 and inhibited Staphylococcus aureus only by 30%. Texel DCM-1 starter culture showed minimal antagonistic activity. It suppressed Bacillus сereus and Escherichia coli by only 35% and showed almost no antagonistic activity against other tested microorganisms.

The antagonistic activity of the newly isolated strains, which averaged from 12 to 17, was significantly lower than that of most active meat starter cultures, excluding Texel DCM-1 (the average GII ranges from 70 to 97) and medicinal preparations Lactobacterin and Bifidobacterin (the average GII is 95 and 49, respectively).

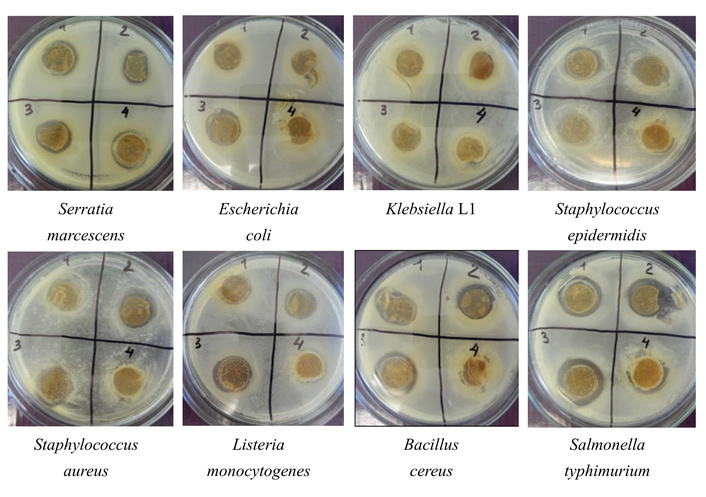

View of Petri dishes with examined samples by the agar diffusion method is shown in Figure 6.

View of Petri dishes with continuous test cultures in the presence of meat starter cultures. 1: Safe Pro B-LL-20, 2: Bactoferm F-SC-111, 3: Schaller Start Star, 4: Texel DCM-1.

The AAI of test cultures, calculated as described in the section “Antagonistic activity determination”, is presented in Table 4. The cells in Table 4 are colored according to the numerical value of AAI, similar to those in Table 3.

Antagonistic activity index (AAI) of tested meat starters, preparations, and newly isolated strains (agar diffusion method).

| Starters, preparations, and newly isolated strains | Test cultures | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serratia marcescens | Escherichia coli | Klebsiella L1 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Staphylococcus aureus | Listeria monocytogenes | Bacillus сereus | Salmonella typhimurium | Average | |

| Meat starters | |||||||||

| Safe Pro B-LL-20 | 3.3 | ||||||||

| Bactoferm F-SC-111 | 2.9 | ||||||||

| Schaller Start Star | 3.1 | ||||||||

| Texel DCM-1 | 1.5 | ||||||||

| Medicinal preparations | |||||||||

| Lactobacterin | 3.3 | ||||||||

| Bifidobacterin | 2.8 | ||||||||

| Newly isolated strains | |||||||||

| L. casei 1 | 2.9 | ||||||||

| L. fermentum 13 | 2.4 | ||||||||

| L. plantarum 1 | 2.5 | ||||||||

| L. acidophilum 9 | 2.5 | ||||||||

| L. paracasei 6 | 2.5 | ||||||||

| Average | 3.5 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.7 | |

L. casei 1: Lacticaseibacillus casei 1; L. fermentum 13: Lactiplantibacillus fermentum 13; L. plantarum 1: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 1; L. acidophilus 9: Lactobacillus acidophilus 9; L. paracasei 6: Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. tolerans 6.

An analysis of the data presented in Figure 6 and Table 4 indicates that almost all the bacteria studied had antagonistic activity against test microorganisms. The bacterial strain of Lactobacterin—L. plantarum 8P-A3—had the maximum antagonistic activity against almost all test cultures studied. Starters Safe Pro B-LL-20 and Schaller Start Star, which actively suppressed the growth of test cultures, had high inhibitory activity. Minimal antagonistic activity was detected for Texel DCM-1 starter culture, and it was active only against Salmonella typhimurium and Serratia marcescens. The antagonistic activity of the newly isolated strains (the average value of AAI is 2.4–2.9) is clearly inferior to that of meat starters (AAI varies from 1.5 to 3.3) and medicinal preparations Lactobacterin and Bifidobacterin (AAI is 3.3 and 2.8, respectively).

The presented article examines the antagonistic activity of bacterial strains, both included in commercial meat starter and medicinal preparations, as well as newly isolated from silage and fermented dairy products. Two in vitro methods, agar diffusion (disk agar diffusion) and co-cultivation in liquid media, demonstrated their significant antimicrobial activity against 8 strains of pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms. The results obtained highlight the high antimicrobial potential of these strains, especially L. plantarum 8P-A3. This strain, and especially the medicinal drug Lactobacterin created on its basis, is widespread in Russia, its large-scale production has been established, and it is widely used to treat a number of health disorders, which once again confirms its effectiveness. Strains and poly-strain compositions included in commercial meat starter cultures, for example, Pediococcus acidilactici, part of Christian Hansen Safe Pro B-LL-20, Staphylococcus carnosus, and Latilactobacillus sakei, part of Christian Hansen Bactoferm F-SC-111, composition Latilactobacillus curvatus, Pediococcus pentosaceus, Staphylococcus carnosus, part of Schaller Start Star, have also shown high efficiency. The effectiveness of these commercial starter cultures has also been confirmed.

It is clear from experimental data that the strength of antagonistic activity is primarily determined by the genus and type of microorganisms that make up the preparation or starter culture. For example, Texel DCM-1 starter culture, which has the lowest antibacterial activity, contains only Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus, while all other starter cultures (except Safe Pro B-LL-20) contain Lactiplantibacillus. This gives us reason to believe that it is the representatives of the genus Lactiplantibacillus that most actively inhibit the growth of pathogenic microorganisms.

Our approaches to the isolation of new active LAB strains from various sources, including fermented dairy products, such as yoghurts, are well in line with the approaches presented in the previously published work [41].

However, this study has certain limitations, primarily because the antagonistic activity of the newly isolated strains is clearly inferior to that of commercial meat starters and medicinal preparations. Additional screening of active strains from various natural sources will be required. It is more effective to produce microorganisms with high antagonistic activity, active synthesis of bacteriocins, and tolerance to stress through mutagenesis, directed evolution, and genetic engineering methods [66, 67]. Productivity will be ensured by high-performance approaches described earlier [60], such as microplates (microtiters) and co-cultivation in liquid media, which allow testing hundreds of strains while simultaneously determining the GII. Screening based on hydrogel emulsions in oil with FACS sorting and bacteriological cytological profiling (BCP) has proven itself well [68, 69].

The second limitation of the presented article is the fact that antagonistic activity is not the only requirement for microorganisms to be used as a commercial starter culture. There are other important requirements specific to different product groups. Thus, for meat products, the key properties are the reduction of nitrites and nitrates (to increase the safety of the finished product), antioxidant activity (to prevent lipid peroxidation and color stabilization during storage), proteolytic and lipolytic activity (to improve taste), and acid-forming ability (to accelerate coloring and increase moisture loss during fermentation). In Russia, the microorganisms Staphylococcus carnosus, Latilactobacillus sakei, and Pediococcus pentosaceus are widely used as starter cultures for fermented sausages and dried foods.

For fermented milk products, the preferred growing temperature (mesophilic 28–32°C, thermophilic 40–46°C), maximum acidity (95–350°T), milk protein coagulation activity, and probiotic properties are important criteria. The most common are Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis/cremoris, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgarian and bifidobacteria.

Baking strains are selected based on their ability to form sensoric properties, accumulate acid, and be active against potato bread disease; L. plantarum and Pediococcus in combination with Saccharomyces yeast with high acidity best meet these criteria.

This information suggests the following promising areas of our work related to the experimental determination of the presence and severity of these desired abilities in both strains included in commercial starter cultures and newly isolated strains.

It is also useful to study the antimicrobial properties of strains in relation not only to pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms that can be considered models, but also those present in real samples of meat offal from various animal species.

It is also interesting to study the mechanisms of the antagonistic activity of LAB, which may be based on their ability to synthesize different organic compounds useful for food technologies and pathogen control [70]. The inhibitory and anti-biofilm efficacy of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus casei against Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes were investigated. Two control mechanisms have been identified and studied: co-adhesion on surfaces and protection against pathogens by biofilm formation from LAB cells [71]. Finally, it is relevant to study the spectrum of synthesized metabolites, including organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins that inhibit the growth of pathogens [72–74].

An important aspect of the study is to address the issue of the interchangeability of various methods for determining the antagonistic activity of microorganisms. To assess the comparability of antagonistic activity data obtained by two alternative methods, the Pearson linear correlation coefficient r between the two datasets is used. The overall correlation is r = 0.43, which indicates an average positive correlation.

When estimating the correlation of the average values across the columns, i.e., when comparing the sensitivity of the tested pathogenic and opportunistic strains, the correlation is 0.71, which corresponds to a strong positive relationship. Similarly, the correlation of the average values across the lines, reflecting the assessment of the effectiveness of the studied newly isolated strains, starter cultures, and preparations, is also high and amounts to 0.75.

These results indicate that these methods are not completely interchangeable, and further research is required.

The highest inhibition index was observed in starters containing representatives of the genus Lactobacillus. The antagonistic activity of the newly isolated strains is clearly inferior to that of commercial meat starters and medicinal preparations.

The advantages of the agar diffusion method include visibility, the possibility of simultaneous evaluation of the activities of a set of antagonist strains, and the advantage of the co-cultivation method is higher differentiation.

To compare the two alternative methods for determining antagonistic activity used in the presented work, the Pearson linear correlation coefficient r between the sets of results obtained by these two methods was used. A more correct assessment of the results was obtained when comparing not two complete sets of experimental data for each method, but when comparing the results in columns (then the sensitivity of the tested pathogens was evaluated) and in rows (then the antimicrobial activity of the studied strains was compared). In terms of the sensitivity of the tested pathogenic strains, the correlation between the two methods is 0.71, and in terms of the activity of the probiotic strains isolated from different sources, the correlation coefficient was 0.75. This indicates a strong positive relationship. These results suggest that these methods are not completely interchangeable, which requires further research.

AAI: antagonistic activity index

B. bifidum: Bifidobacterium bifidum

GII: growth inhibition index

L. plantarum: Lactiplantibacillus plantarum

LAB: lactic acid bacteria

MPB: meat peptone broth

MRS: Man-Rogosa-Sharpe

RK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. SK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft. OR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. SV: Investigation, Writing—original draft. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The author, Rustem Khabibullin [hrustik@yandex.ru], will make the data of this research available to any researcher.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 475

Download: 30

Times Cited: 0