Affiliation:

Department of Endocrinology, Faculty of Medicine, Georgian National University SEU, Tbilisi 0144, Georgia

Email: ninoturashvili88@yahoo.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8432-7569

Explor Endocr Metab Dis. 2025;2:101452 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eemd.2025.101452

Received: August 10, 2025 Accepted: November 19, 2025 Published: December 18, 2025

Academic Editor: Charlotte Steenblock, University Clinic Carl Gustav Carus, Germany

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and dual incretin agonists have demonstrated significant potential in improving adipose tissue function beyond their established effects on appetite suppression and weight loss. These agents not only reduce overall fat mass but also induce favorable changes in fat distribution and adipose tissue quality. Notably, they enhance brown adipose tissue (BAT) activity and promote the browning of white adipose tissue (WAT), thereby increasing energy expenditure. They are associated with reductions in adipocyte size, particularly within visceral fat depots, alongside improvements in metabolic health markers. The aim of this publication is to provide a literature review on the effects of GLP-1RAs and dual incretin agonists on adipocyte type and size, adipose tissue functional remodeling, and their implications for obesity management. These findings highlight the capacity of incretin-based therapies to modulate adipose tissue biology, offering metabolic benefits that extend beyond weight reduction.

Obesity is a chronic, relapsing, and progressive disease with complex causes, including genetic, metabolic, sociocultural, behavioral, and environmental factors [1]. It is associated with a wide range of clinical complications, such as cardiovascular diseases (e.g., ischemic heart disease and heart failure), metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, knee osteoarthritis, mental health disorders, and certain types of cancer [2, 3]. Obesity is becoming increasingly common in the world. Since gaining weight raises the risk of serious health problems, there is a strong interest in creating medications to help treat obesity. Current approaches to treating obesity include lifestyle modifications, pharmacological therapies, and endoscopic or surgical interventions [4].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone secreted by L-cells in the small intestine. It lowers blood glucose levels by stimulating insulin secretion and suppressing glucagon (GCG) release from the pancreatic islets in a glucose-dependent manner [5]. GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are antidiabetic drugs that help control blood glucose levels and support weight loss in people with or without type 2 diabetes [3, 6–17]. Although their weight loss effects are well known, the exact mechanism behind these effects remains unclear. The GLP-1RAs have been shown to reduce food intake, promote weight loss, and improve metabolic function in both animals and humans. These effects are thought to occur through GLP-1’s influence on both peripheral (vagal) and central pathways, including the hindbrain, hypothalamus, and brain regions involved in motivation and reward, which help regulate appetite and metabolism [8, 14, 18]. The precise mechanisms through which GLP-1RAs exert their effects on adipose tissue remain incompletely understood. A potentially key mechanism through which GLP-1RAs act against obesity may involve the modification of adipocyte phenotype and function.

There are different types of adipose cells: White, beige, and brown adipocytes exhibit distinct lipid metabolism and thermogenic potential, which contribute to variations in their size and morphology. White adipose tissue (WAT) is distributed across various distinct anatomical sites in the bodies of mammals. The primary depots are generally classified as subcutaneous or intra-abdominal. In addition to these major depots, smaller amounts of WAT are present in other regions, including the bone marrow, subdermal areas, around blood vessels (perivascular), around the heart (epicardial), and in peri- and intermuscular spaces [19]. WAT serves as a reservoir that helps manage excess energy intake and reduces energy expenditure during obesity development. This leads to fat buildup in visceral and ectopic regions. These fat stores are closely linked to persistent systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and increased cardiometabolic risks associated with obesity [20].

On the other hand, brown and beige adipocytes are characterized by a high mitochondrial content and possess the ability to dissipate energy as heat. Brown adipose tissue (BAT), which plays a key role in thermogenesis, is present in smaller depots located at specific anatomical sites. In both mice and humans, these include the anterior cervical, supraclavicular, interscapular, perirenal, and perivascular regions [19, 21].

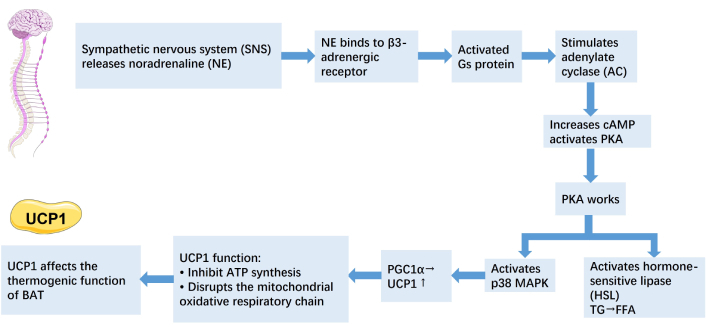

As obesity progresses, WAT expands abnormally in regions such as the omentum, mesentery, and retroperitoneum, which together make up visceral WAT. This type of fat is metabolically very active and consistently releases free fatty acids into the portal vein, contributing to the development of metabolic syndrome characteristics [22]. Brown fat cells are different from white ones. The large number of mitochondria and their iron content give brown fat its darker color. They have many small fat droplets, lots of mitochondria, and high levels of a special protein—uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) [23]. The thermogenic function of BAT depends on UCP1, a fatty acid anion transporter located in the inner mitochondrial membrane. UCP1 disrupts the mitochondrial oxidative respiratory chain by preventing adenosine diphosphate (ADP) from synthesizing adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which leads to the release of energy as heat. This process is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system. In mature adipocytes, noradrenaline (NE) released by the sympathetic nervous system binds to β3-adrenergic receptors, activating the guanine nucleotide-binding protein (Gs), which in turn stimulates adenylate cyclase (AC). Activated AC converts intracellular ATP into cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), increasing cAMP levels and activating protein kinase A (PKA). PKA then activates hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), which accelerates the breakdown of triglycerides into glycerol and free fatty acids. PKA also activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), which then activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC1α) and ATF-2. PGC1α helps increase UCP1 gene activity by working with PPAR, leading to more UCP1 production [24]. It is estimated that when fully activated, just 50 g of BAT can account for up to 20% of the body’s basal energy expenditure [25]. When activated by fatty acids, UCP1 increases the flow of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane without generating ATP. Instead, this process produces heat. Since it consumes energy without storing it, BAT functions as an energy-expending organ [26] (Figure 1).

Mechanism of thermogenesis in BAT. The icon is provided by Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com), licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PKA: protein kinase A; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; PGC1α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha; UCP1: uncoupling protein 1; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; BAT: brown adipose tissue.

BAT activation may help improve metabolic issues such as high blood sugar and abnormal lipid levels, suggesting it could be a useful therapeutic target for obesity and related metabolic disorders [24]. Studies have shown that exposure to cold or β-adrenergic stimulation can induce the appearance of brown-like adipocytes, known as beige cells, within the subcutaneous WAT of mice. Over the last decade, an increasing number of studies have found that activating BAT and browning of WAT can protect against obesity and obesity-related metabolic disease.

BAT functions as an essential thermoregulatory organ during early life and is abundant in infants and young children. In adults, BAT at the scapular region largely disappears, with only small amounts remaining in areas such as the clavicle, around the carotid arteries, and near the heart. As individuals age, the likelihood of detecting BAT in the body decreases. PET/CT imaging studies have shown that BAT was detected three times more often in individuals under the age of 50 compared to those aged 64 and above. Besides age, the distribution of BAT also differs between men and women. PET/CT scans have shown that females tend to have higher detection rates and greater amounts of BAT compared to males [27]. The (re)discovery of active BAT in adults renewed scientific interest in its potential as a new treatment option for obesity [28]. Some studies emphasize an important challenge in using BAT activation as therapy, since patients need to have sufficient BAT mass and activity to benefit. Therefore, increasing the amount of functional BAT is likely necessary to achieve meaningful improvements in metabolic health. BAT can be activated by cold exposure, diet, and physical activity [24]. For instance, people working outdoors in colder climates tend to have more BAT compared to those who work indoors [29]. Brown and beige adipocytes rely on sustained β-adrenergic stimulation to maintain their functional activity. Patients with catecholamine-secreting tumours (phaeochromocytomas) often have substantial BAT mass and function, which regress upon surgical removal of the tumour [30].

Caloric restriction (CR) induces the browning of WAT, promotes the development of functional beige fat, and enhances both the type 2 immune response and the expression of silent information regulator type 1 (SIRT1) [31]. Modulation of SIRT1 may improve mitochondrial function and promote BAT formation [32, 33]. The browning of WAT could be a potential strategy to expand the thermogenic potential of adipose tissue mass. BAT activation is also debated as a potential therapeutic target for weight loss. When BAT is denervated, it loses its thermogenic and oxidative capacity, accompanied by a morphological transformation known as “whitening”, characterized by the appearance of white-like unilocular adipocytes [34]. Several studies have shown that exercise training—such as swimming, voluntary wheel running, and treadmill running—promotes the browning of WAT in rodents through multiple mechanisms. In early overfed male Wistar rats, moderate exercise increased sympathetic nervous system activity and upregulated the expression of β3-adrenergic receptors and UCP1 in BAT, thereby enhancing its thermogenic function and increasing energy expenditure [35, 36].

Beige adipocytes serve as an intermediate form between white and brown adipocytes. They typically contain multiple lipid droplets, which are generally larger than those found in brown adipocytes. While they possess more mitochondria than white adipocytes, their mitochondrial content is less than that of brown adipocytes. Beige adipocytes also express UCP1 [23].

The different sizes of adipocytes are a separate and important issue. Variation in the size of adipocytes is observed in conditions such as insulin resistance, diabetes, obesity, and during dietary interventions [37]. In general, large hypertrophic adipocytes are considered metabolically unfavorable and are associated with various pathophysiological conditions. Some studies on human adipocytes demonstrated that increased fat cell size correlates with impaired whole-body metabolic regulation and systemic insulin resistance. It was found that an average adipocyte size of 115 μm correlated with normal glucose tolerance test (GTT) results; 121 μm with impaired GTT; and 125 μm with diabetes [38].

Accordingly, pharmacological agents capable of reducing WAT and promoting its transdifferentiation into beige or BAT, as well as decreasing adipocyte size, may play a significant role in the therapeutic management of obesity.

In healthy individuals, GLP-1 enhances insulin secretion and suppresses GCG release in response to nutrient intake. Additionally, GLP-1 delays gastric emptying and promotes satiety. In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), supraphysiological doses of GLP-1 can normalize endogenous insulin responses during hyperglycemic clamp studies. Due to the short plasma half-life of native GLP-1, several GLP-1RAs with extended half-lives have been developed for the treatment of T2DM. GLP-1 receptors are expressed in various tissues, including pancreatic beta cells and the central nervous system [39]. Treatment with GLP-1 analogs induces weight loss, primarily through mechanisms such as enhanced satiety, reduced appetite, and decreased caloric intake. This weight reduction may consequently lead to a decrease in adipose tissue volume. However, studies have shown that GLP-1 may improve insulin sensitivity, activate BAT and reduce adipose tissue inflammation and GCG secretion [40–43]. In addition, GLP-1 contributes to weight loss, primarily through mechanisms such as appetite suppression, reduced food intake, and delayed gastric emptying [44]. However, the direct effects of GLP-1RAs on fatty acid synthase expression and lipid metabolism remain unclear. Chen et al. [45] confirmed the presence of GLP-1 receptors in both preadipocytes and differentiated adipocytes. A recent review of all these pharmaceutical agents highlights their therapeutic potential and safety profiles in the management of obesity [46]. The known mechanisms underlying its effects on weight loss include appetite suppression and reduced food intake, mediated through hypothalamic and parasympathetic pathways [47]. The GLP-1RA exenatide has been shown to reduce hyperactivation in brain regions associated with appetite and reward in response to food cues in both obese individuals with type 2 diabetes and obese normoglycemic subjects, thereby normalizing neural activation patterns to resemble those observed in lean individuals [48]. However, little is known about the effects of GLP-1RAs on adipose tissue.

Liu et al. [49] (2022) described that GLP-1RA treatment resulted in a greater reduction in visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) in the subgroup with a greater reduction in body weight. The absolute area reduction in VAT was significantly correlated with the reduction in body weight [49]. A short course of GLP-1RA treatment not only promotes weight loss but also appears to redistribute fat deposits, which may help improve cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes [50]. Liraglutide, a GLP-1RA, may influence body fat distribution by regulating lipid metabolism in various fat tissues [51]. The results showed that liraglutide reduced visceral fat while relatively increasing subcutaneous fat. In visceral WAT, lipogenesis was decreased, whereas it was elevated in subcutaneous WAT. The expression of browning-related genes was upregulated in subcutaneous WAT. These findings suggest that liraglutide may redistribute body fat and promote browning in subcutaneous WAT, thereby contributing to the improvement of metabolic disorders. Liraglutide improved hepatic steatosis and decreased adipocyte size in fat depots [52]. GLP-1 reduced the expression of lipogenic genes during in vitro differentiation of human adipocytes derived from morbidly obese patients. Treatment with exenatide or liraglutide also decreased the expression of adipogenic and inflammatory markers in the adipose tissue of obese individuals with T2DM [53]. Liraglutide induced browning of WAT, which was noticeable 24 hours after its injection. Levels of UCP1 protein were significantly increased in the WAT of mice treated with intracerebroventricular liraglutide [54]. Both liraglutide injections and food restriction significantly decreased hepatic lipid accumulation in rats. Additionally, liraglutide markedly increased UCP1 protein expression in the inguinal and cluneal WAT, and this effect was dose-independent. These findings suggest that liraglutide promotes browning and remodeling of subcutaneous WAT, similar to the effects observed with food restriction [52].

Exendin-4 is a peptide agonist of the GLP receptor that promotes insulin secretion and browning of WAT. SIRT1 plays a vital role in the regulation of lipid metabolism. In vitro studies have shown that exendin-4 enhances lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation by upregulating SIRT1 expression and activity in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Some studies highlight that a GLP-1RA promotes the browning of WAT in a SIRT1-dependent manner, which may represent one of the mechanisms contributing to its weight loss effects [55].

Semaglutide significantly promotes weight loss mainly by reducing food intake. However, the study found that semaglutide also affects body fat distribution and adipocyte characteristics: semaglutide led to a reduction in adipocyte size and macrophage infiltration, an increase in molecular markers of adipocyte browning along with improved mitochondrial biogenesis, and a decrease in endoplasmic reticulum stress. It increased multilocularity and enhanced UCP1 expression in obese mice. Therefore, semaglutide exerts effects beyond merely reducing food intake [56].

Semaglutide enhances BAT thermogenesis and WAT browning mainly through the GLP-1/GLP-1R pathway by activating adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a key protein that regulates cellular energy. AMPK activates SIRT1, which helps cells develop into brown and beige fat cells and increases the levels of UCP1, a protein essential for heat production [57, 58] (Tables 1 and 2).

Effects of GLP-1RAs on WAT/BAT (animal study).

| Study/Author (year) | Study type/model | GLP-1RA used | Biological effects of WAT/BAT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ding et al. [58], 2006 | Ob/ob mice (preclinical) | Exendin-4 | ↓ Liver fat accumulation; improves insulin sensitivity; indirect WAT benefits |

| Beiroa et al. [54], 2014 | Rodents | Liraglutide | ↑ BAT thermogenesis, ↑ energy expenditure, ↓ fat mass |

| Xu et al. [56], 2016 | Obese mice, translational | Exendin-4 | Browning of WAT, ↑ mitochondrial activity, ↑ UCP1 expression |

| Zhao et al. [52], 2019 | Animal study | GLP-1RA (liraglutide) | Redistribution of fat: ↓ VAT, ↑ SAT browning, and fatty acid oxidation |

| Martins et al. [55], 2022 | Obese mice | Semaglutide | ↓ Inflammation in VAT, ↑ browning of subcutaneous WAT |

BAT: brown adipose tissue; GLP-1RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SAT: subcutaneous adipose tissue; UCP1: uncoupling protein 1; VAT: visceral adipose tissue; WAT: white adipose tissue.

Effects of GLP-1RAs on WAT/BAT (human study).

| Study/Author (year) | Study type/model | GLP-1RA used | Biological effects of WAT/BAT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morano et al. [50], 2015 | Human clinical (ultrasound, 3 months) | Liraglutide, exenatide | ↓ Abdominal subcutaneous and deep fat thickness |

| El Bekay et al. [53], 2016 | Human adipose tissue explants (in vitro) | Liraglutide | ↓ Lipogenesis, ↑ lipolysis in SAT; anti-inflammatory effects |

| Chaudhury et al. [51], 2017 | Clinical review | Liraglutide | ↓ Body weight, ↓ fat mass, and potential adipose redistribution |

| Liu et al. [49], (2022) | Meta-analysis of 17 RCTs in T2D patients (n = 924) | GLP-1RAs | ↓ Visceral and SAT area |

| Papakonstantinou et al. [57], 2024 | Molecular review | Semaglutide | Highlights the impact of semaglutide on adipose metabolism and energy homeostasis |

BAT: brown adipose tissue; GLP-1RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SAT: subcutaneous adipose tissue; WAT: white adipose tissue.

Therefore, GLP-1RAs (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide, exendin-4) not only promote weight loss but also improve fat distribution and induce browning of WAT. These effects involve reductions in visceral fat, adipocyte size, and inflammation, as well as activation of thermogenic pathways such as AMPK/SIRT1 and UCP1 expression.

Tirzepatide is a dual agonist of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 receptors that has shown better glycemic control and greater weight loss compared to selective GLP-1RAs in patients with type 2 diabetes [59]. GIP is the main incretin hormone in healthy individuals and stimulates insulin secretion. Unlike GLP-1, GIP also promotes GCG release in a glucose-dependent way. When blood glucose is high, GIP increases insulin release, which lowers GCG levels. However, when blood glucose is normal or low, GIP raises GCG levels [60]. Frías et al. [61] noted that tirzepatide showed a significant reduction in body fat mass and adipocyte size, and improved insulin sensitivity. In participants who underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, tirzepatide led to a mean reduction in total body fat mass of 33.9%, compared to 8.2% with placebo. Additionally, the ratio of total fat mass to lean mass decreased more with tirzepatide than with placebo [62] (Table 2). Compared to other anti-obesity medications (e.g., dulaglutide and semaglutide) administered over the same duration, tirzepatide demonstrated a superior reduction in body fat compartments, including total fat mass, VAT, and waist circumference [63]. According to Xia et al. [64], tirzepatide effectively reduced VAT inflammation by inhibiting M1-type macrophage infiltration in the visceral fat of obese mice (Table 3).

Tirzepatide effects on WAT and BAT.

| Parameter | Tirzepatide |

|---|---|

| WAT browning | Enhances WAT browning; upregulates thermogenic genes even at low doses [59] |

| BAT thermogenesis | Increases BAT activity and BCAA catabolism, promoting energy expenditure [59] |

| Body composition | Reduced total body fat mass of 33.9%, compared to 8.2% with placebo [63] |

| Inflammatory markers in WAT | It may reduce inflammation indirectly via improved insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism [64] |

| Adipocyte lipid metabolism | GIP regulates adipocyte lipid metabolism by enhancing lipolysis and lipoprotein lipase activity [65] |

| Induction of lipolysis | Dual incretin agonists exert additional effects through modulation of glucagon signaling [66] |

BAT: brown adipose tissue; GIP: glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide; WAT: white adipose tissue; BCAA: branched chain amino acids.

The exact mechanisms underlying the greater weight loss observed with dual incretin agonists compared to GLP-1RAs alone remain incompletely understood. Some studies suggest that GIP plays a significant role in regulating lipid metabolism in adipocytes by promoting lipolysis and increasing lipoprotein lipase activity [65]. Additionally, GIP facilitates fatty acid re-esterification. It is also possible that dual incretin agonists exert additional effects through modulation of GCG signaling. However, the role of GCG in WAT has not been thoroughly investigated. Existing evidence indicates that GCG can induce lipolysis in isolated adipocytes in vitro. Since dual incretin agonists increase circulating GCG levels, this mechanism may also contribute to the enhanced weight loss and adipocyte-related effects observed with these agents [66].

Obesity is characterized by both an increase in fat mass and pathological alterations in adipocyte function. GLP-1RAs and dual incretin agonists have been shown to reduce adipocyte hypertrophy and stimulate the activation of BAT, thereby enhancing energy expenditure and metabolic function. Studies have demonstrated that agents such as liraglutide and semaglutide upregulate browning-associated gene expression in subcutaneous WAT. Furthermore, dual incretin agonists like tirzepatide exhibit superior efficacy, not only in reducing adipocyte size and visceral fat volume, but also in promoting BAT thermogenesis.

This dual effect—shrinking adipocytes and enhancing thermogenic capacity—suggests a functional shift in adipose tissue from energy storage toward energy dissipation. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of GLP-1RAs and dual incretin agonists as metabolic modulators that target both quantitative and qualitative aspects of adipose tissue remodeling. Individual variation in BAT mass may influence clinical response, highlighting the need to consider patient-specific factors when evaluating treatment efficacy. The long-term safety of GLP-1/GIP combination therapy remains insufficiently verified.

While further research is warranted, current evidence supports their use as promising interventions to improve metabolic health beyond mere weight loss. Additional research is required to develop pharmacological agents capable of inducing the transdifferentiation of WAT into BAT tissue, thereby offering a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of obesity.

AC: adenylate cyclase

ADP: adenosine diphosphate

AMPK: adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

ATP: adenosine triphosphate

BAT: brown adipose tissue

BCAA: branched chain amino acids

cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate

CR: caloric restriction

GCG: glucagon

GIP: glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1

GLP-1RAs: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

Gs: guanine nucleotide-binding protein

GTT: glucose tolerance test

HSL: hormone-sensitive lipase

MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase

NE: noradrenaline

PGC1α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha

PKA: protein kinase A

PPAR: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

SAT: subcutaneous adipose tissue

SIRT1: silent information regulator type 1

T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus

UCP1: uncoupling protein 1

VAT: visceral adipose tissue

WAT: white adipose tissue

NT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. The author read and approved the submitted version.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 3416

Download: 54

Times Cited: 0