Affiliation:

Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Systems Medicine for Inflammatory Diseases & Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, Shenzhen 518107, Guangdong, China

Email: zhaozw5@mail2.sysu.edu.cn

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6731-0474

Explor Endocr Metab Dis. 2026;3:101453 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eemd.2026.101453

Received: August 21, 2025 Accepted: November 13, 2025 Published: January 05, 2026

Academic Editor: Esma R Isenovic, University of Belgrade, Serbia

The global prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)—the most common metabolic disorders—has reached epidemic proportions over the past half-century, with obesity being a key driver of insulin resistance and T2DM development. These disorders are characterized by metaflammation (chronic low-grade inflammation across multiple metabolic organs like adipose tissue, liver, muscle, and the gut), which disrupts metabolic homeostasis, exacerbates insulin resistance, impairs insulin secretion, and links to other comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases. A major advance in understanding inflammation resolution is the identification of specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), a family of lipid mediators including resolvins, lipoxins, protectins, and maresins. Derived from polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g., EPA, DHA), SPMs actively regulate inflammation resolution by constraining pro-inflammatory cell infiltration (e.g., neutrophils), promoting anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization (M2), enhancing efferocytosis (clearance of apoptotic cells), and preserving tissue barrier integrity—without inducing immunosuppression. This review summarizes evidence from human and animal studies on obesity-related metaflammation in metabolic tissues and the role of SPMs in resolving this inflammation. It details SPM mechanisms (e.g., maintaining adipose tissue homeostasis, improving insulin sensitivity, alleviating hepatic steatosis) and highlights their dysregulation in obesity (e.g., impaired biosynthesis, reduced receptor expression) as a critical driver of metabolic dysfunction. Finally, the review discusses the therapeutic potential of SPM-targeted strategies (e.g., ω-3 PUFA supplementation, SPM receptor activation) for alleviating obesity, T2DM, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MAFLD), and other metabolic disorders, along with future research directions in this field.

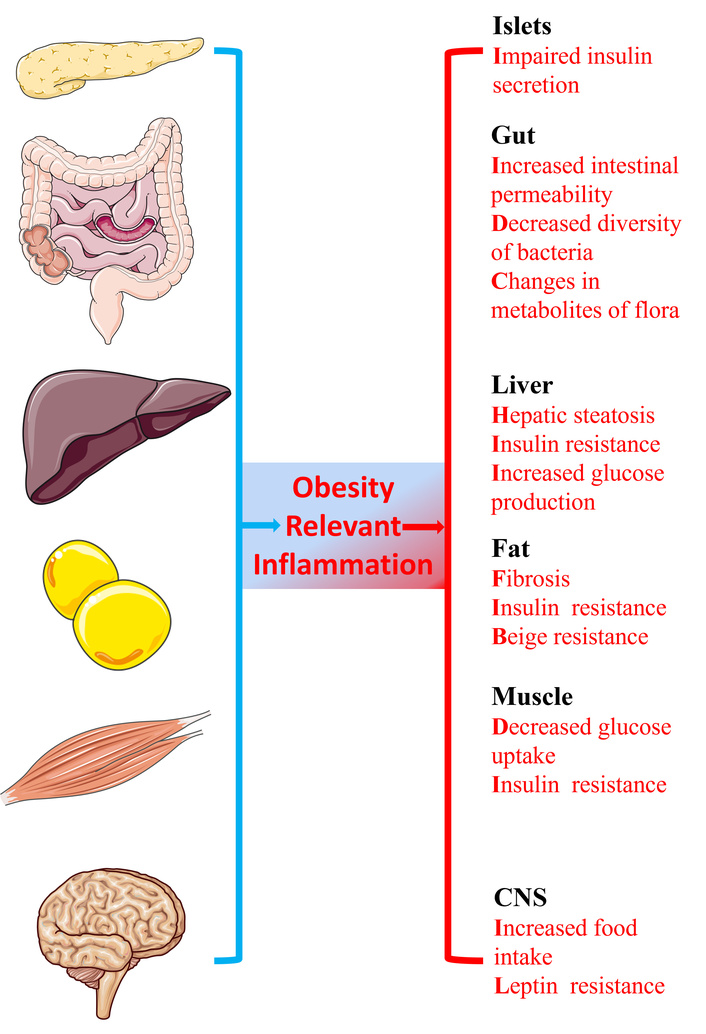

In the last half-century, the prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been rapidly increasing on a global scale and has now reached epidemic proportions [1–4]. Obesity is the crucial cause of insulin resistance and a driver of the global epidemic of type 2 diabetes [5]. As a well-recognized underlying abnormality, insulin resistance stems from an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure—one that favors the pathways of nutrient storage. These pathways evolved to promote energy conservation (rather than utilization) during periods of scarcity, but in the modern context of excess energy, they exacerbate the development of obesity [6]. At the outset of the energy imbalance, lesions of white adipose tissue and circulating metabolites modulate tissue communication and insulin signaling [7, 8]. When it sinks into persistent state, obesity-related chronic inflammation accelerates these abnormalities [9]. Obesity-induced chronic tissue inflammation underlines the predominant role of dysmetabolism under these circumstances [9, 10]. Chronic tissue inflammation exerts a series of effects on adipose tissue, muscle, liver, pancreatic islets, the gut, and hypothalamus [5]. These inflammatory shifts conduce to insulin resistance (fat, muscle, liver) [11, 12], reduced insulin secretion (islets) [13], gut microbial dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability (gut) [14], and increased food intake (hypothalamus) [15].

Obesity-induced excessive inflammation is diffusely appreciated to be a unifying element in many chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [16], cancer [17], and metabolic syndrome [18], and thus is a public health issue. Comprehending endogenous monitoring points within the inflammatory response will inspire us with novel perspectives on pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches to dysmetabolism. The acute inflammatory response is divided into initiation and resolution by pathologists. After the identification of lipid mediators with pro-resolving competence that could be biosynthesized from Ω-3 essential fatty acids, some reports demonstrated that resolution of self-limited acute inflammation is an active, programmed reaction but not merely a process of passive fluxing of chemoattractant cytokines [19, 20]. For these metabolites to play the role of resolution, they have to be synthesized in ample amounts in vivo to evoke bioactions. The Ω-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA, found in deep-sea fish oils, have been thought to have anti-inflammatory capabilities for a long while [21]. Resolving inflammatory exudates are comprised of structurally different families of signaling molecules—resolvins, protectins, and maresins, collectively termed specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) [22]. SPMs are agonists with the potential to evoke key cellular resolution processes, namely restricting the infiltration of neutrophils and promoting macrophage to devour apoptotic cells [23].

Here, we focus on the mechanisms of SPMs in resolution that may work in metabolic disease, as it deals with the effects of chronic inflammation on metabolic disorders. We also aim to present a balanced view by addressing existing controversies in the field and briefly discussing prospective orientation in this gradually growing field.

Over the past few decades, there has been a great body of studies exploring the underlying cellular and physiologic mechanisms of how obesity-related inflammation initiates and aggravates insulin resistance and glucose intolerance (Figure 1). The effective mechanistic link that was established for the first time between inflammation and insulin resistance is focused on tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [24, 25]. Activation of other inflammatory signals, such as Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNKs), inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappaB kinase (IKKβ), and nuclear factor k-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), are the characteristics of chronic tissue inflammation induced by obesity, and genetic knockout or activity inhibition of these factors also results in protection from obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance [12, 15, 26–28].

The metabolic consequences of obesity on distinct organs. Obesity relevant chronic tissue inflammation is one of the key mechanisms of dysmetabolism. The effects on the liver, adipose tissue, muscle, islets, the gut, and the central nervous system (CNS) induced by chronic tissue inflammation are listed.

Metabolic inflammation, first mentioned in adipose tissue, has been evaluated at great length with numerous studies [25, 29–33]. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that adipose tissue is neither the only site of metabolic inflammation nor could it be considered as the sole participant in metabolic homeostasis or relevant lesion. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that pro-inflammatory signals also increase in the other two classical insulin target tissues (liver [12, 28, 34], and muscle [11, 27, 35]), as well as in islets [13], the hypothalamus [15], and the gastrointestinal tract [14]. Metaflammation, regarded as chronic metabolic inflammation in multiple organs, is involved in metabolic disease (Figure 1). The interactions between inflammatory cells with themselves and their stromal components in the adipose tissue, liver, muscle, and other metabolic organs are a critical determinant of metabolic homeostasis and pathogenesis of metabolic disease [36]. Hence, the bidirectional interactions between inflammatory cells and their stromal components, as well as the systemic impact of metabolic inflammation, are crucial factors in determining physiological and pathological events of metabolism. Given the critical role of metaflammation in disrupting metabolic homeostasis across multiple organs and driving metabolic diseases, identifying effective regulators to modulate this chronic low-grade inflammation has become a key focus in related research. These regulators, which can target the bidirectional interactions between inflammatory cells and stromal components while mitigating the systemic impact of metaflammation, are essential for intervening in the pathogenesis of conditions like obesity, and SPMs emerge as prominent candidates in this context.

SPMs, including resolvins, lipoxins, protectins, and maresins (Table 1), play a pivotal regulatory role in the pathogenesis of obesity by modulating metaflammation—the low-grade, chronic inflammation that characterizes obesity and links it to metabolic disorders [37–39].

Summary of SPMs: classification, precursors, and functions.

| Class | Subtypes/Structures | Precursors | Key functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolvins | E-series (RvE1, RvE2): 18-carbon, 3 double bonds;D-series (RvD1–D6): 22-carbon, 4 double bonds | E-series: EPA;D-series: DHA | Inhibit neutrophil migration and pro-inflammatory cytokine release; Promote macrophage phagocytosis and resolution of inflammation; Enhance epithelial barrier function; Reduce atherosclerosis by suppressing endothelial adhesion molecules |

| Lipoxins | LXA4, LXB4: 20-carbon, 4 double bonds;15-epi-LXA4: Isomer with distinct receptor affinity | Arachidonic acid (AA) | Block neutrophil recruitment and adhesion molecule expression; Induce apoptosis of pro-inflammatory macrophages; Protect against oxidative stress in tissues; Reduce airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma |

| Protectins | PD1 (Neuroprotectin D1): 22-carbon, 5 double bonds;PDX: Modified structure with enhanced stability | DHA | Protect neurons from excitotoxicity and oxidative damage; Modulate microglial polarization toward anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype; Improve cognitive function in Alzheimer’s models; Reduce hepatic steatosis by enhancing fatty acid oxidation |

| Maresins | MaR1, MaR2: 22-carbon, 4 double bondsMCTRs (maresin-coupled tissue repair molecules): Peptide-lipid conjugates | DHA | Promote macrophage clearance of apoptotic cells; Inhibit Th1/Th17 cell differentiation while enhancing Treg cell function; Accelerate skin and corneal wound healing |

SPMs: specialized pro-resolving mediators; EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA: docosahexaenoic acid.

Under physiological conditions, SPMs maintain adipose tissue homeostasis by constraining inflammatory amplification [40, 41]. They inhibit the migration of monocytes to visceral adipose tissue and their differentiation into pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, while promoting the polarization of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages [40, 42, 43]. This reduces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, preventing adipocyte dysfunction and preserving insulin sensitivity—for instance, maresin 1 enhances adipocyte glucose and fatty acid uptake by activating insulin signaling pathways [44, 45]. Additionally, SPMs protect intestinal barrier integrity, limiting lipopolysaccharide (LPS) translocation and subsequent toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated systemic inflammation, which indirectly suppresses aberrant adipose tissue expansion [46–48].

In obesity, however, SPM function is severely impaired, fueling disease progression [49–53]. Nutrient excess and adiposity disrupt SPM biosynthesis: insufficient ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) intake (the precursor of resolvins/protectins) and elevated oxidative stress reduce the activity of lipoxygenases (key enzymes for SPM production) [54–56]. Concurrently, adipocytes and immune cells downregulate SPM receptors (e.g., ALX/FPR2, GPR32), diminishing SPM-mediated anti-inflammatory signaling [57, 58]. This “synthesis deficit plus functional resistance” breaks inflammatory resolution: persistent pro-inflammatory cues induce adipocyte insulin resistance, impair glucose uptake, and promote leptin resistance—creating a vicious cycle of inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and further fat accumulation [50, 52, 59, 60].

Notably, reduced SPM levels correlate with obesity-related comorbidities [e.g., metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MAFLD), atherosclerosis], as impaired inflammation resolution exacerbates hepatic lipid deposition and vascular endothelial damage [61–63]. Clinical data confirm lower serum SPM concentrations (e.g., resolvin E1) in obese individuals, with SPM levels inversely associated with body weight and inflammatory markers [51, 52, 64].

It is noteworthy that a large body of current research is primarily correlational. Although reduced SPM levels are associated with obesity-related comorbidities, such as MAFLD and atherosclerosis, this is because impaired resolution of inflammation exacerbates hepatic lipid deposition and vascular endothelial damage. Clinical data also confirm that obese individuals have lower serum SPM concentrations (e.g., resolvin E1), and SPM levels are negatively correlated with body weight and inflammatory markers. However, these studies only demonstrate a correlation between SPM and obesity; they cannot confirm that SPM is a causative factor of obesity, and the causal relationship between the two remains unclear.

Multiple laboratories have reported difficulties in detecting SPMs in physiological samples (e.g., serum, tissue homogenates) at concentrations sufficient to evoke the proposed bioactions [65, 66]. Potential explanations for this discrepancy include technical limitations (e.g., loss of SPMs during sample extraction, lack of highly specific antibodies for immunoassays) and tissue-specific localization (e.g., SPMs may act locally in tissues at high concentrations but dilute rapidly in circulation). A number of studies have challenged the responsiveness of proposed SPM receptors to their ligands [65, 67, 68]. These findings suggest that either SPMs require co-receptors or accessory molecules to exert their effects, or that some reported receptor-ligand interactions may be context-dependent (e.g., cell-type specific).

A few studies have even questioned the existence of endogenously produced SPMs with functional relevance [69]. However, these results may be attributed to compensatory mechanisms (e.g., upregulation of other anti-inflammatory pathways) or the use of experimental conditions that do not fully mimic physiological inflammation [54, 70, 71].

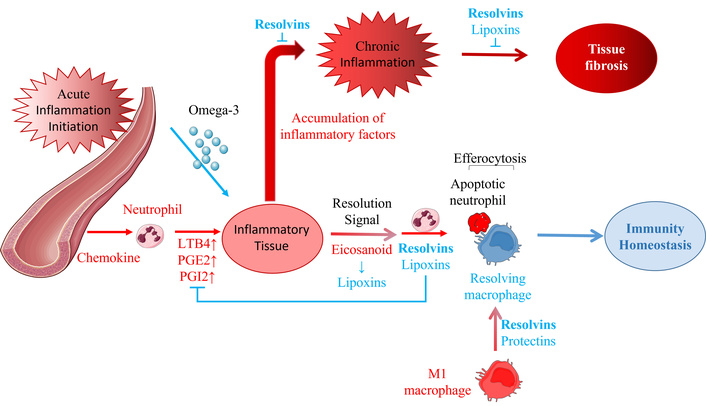

SPMs are lipid micromolecules that include lipoxins, resolvins, protectins, and maresins that are biosynthesized from distinct PUFAs at the onset of inflammation (Table 1) [65, 72, 73]. As part of the inflammatory initiation phase, Ω-6 fatty acid arachidonic acid transforms into lipoxins to begin the resolution of the acute inflammatory response [74], whereas resolvins, protectins, and maresins are derived from the Ω-3 essential fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [19, 75, 76]. Limited to the length, lipoxins aren’t described next, but we have to emphasize that this doesn’t mean that lipoxins are trivial in metabolic diseases. SPMs evoke the active resolution processes of inflammation by restraining the infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) into tissues, inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, regulating the apoptosis of PMN and the efferocytosis of macrophages, and promoting the dilution of chemokine [22, 23]. In general, these SPMs commence resolution and regeneration programs through regulation of innate immunocytes in an inflammatory environment. Here, we cover the resolving functions of SPMs and focus on SPMs’ actions in metabolic disease on the basis of their inflammatory pathogenesis (Figure 2).

The role of SPMs in the initiation, resolution, and chronic progression of acute inflammation.

SPMs play crucial roles in the vascular response and neutrophil trafficking, from acute inflammation initiation to resolution or continuation. The SPMs, lipoxins, resolvins, protectins, and maresins are produced during this self-limited process. When acute inflammation occurs in local tissues, a large number of chemokines (PGE2, PGI2 (vasodilation), and LTB4 (chemotaxis and adhesion) are released to make the neutrophils chemotactic to the tissue. As one of the initiating parts of resolution, eicosanoids are converted to lipoxins, signaling and beginning the end of the acute inflammatory response [74, 77, 78]. Lipoxins and resolvins limit the infiltration of polynuclear neutrophils and promote their apoptosis. Resolving macrophages induced by resolvins and protectins then clear the apoptotic neutrophils in a process known as efferocytosis, which restores the immunity homeostasis of the inflammatory tissue. Resolution failure leads to the continued accumulation of various inflammatory factors, the development of chronic inflammation (which can be suppressed by resolvins), and fibrosis (which can be inhibited by resolvins and lipoxins). Figure 2 shows that resolvins play a key role in different resolution processes for acute and chronic inflammation, suggesting that they may be the most potent of the SPMs.

Resolvins, including the D, E, and T series, are endogenous lipid metabolites biosynthesized during the resolution phase of acute inflammation from the ω-3 PUFAs (Table 1), primarily EPA, DHA, and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) [79–81]. Their anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving properties have been confirmed with great evidence from multiple animal inflammatory models [82–86]. Resolvins have been evaluated to evoke the resolving process not only in acute inflammation but also in chronic inflammation. Sima et al. [87] summarized the role of RvE1 in inflammation resolving and focused on its function in type 2 diabetes in light of its inflammatory pathogenesis (Figure 1). In population-based research on the association between resolvin E1 (RvE1) and adiposity, univariate analysis has linked obesity to reduced RvE1, and multiple regression analysis has further shown plasma RvE1 to be negatively correlated with various adiposity metrics (BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-height ratio, abdominal subcutaneous fat volume, skinfold thicknesses) in both genders [51]. Recent studies have demonstrated that resolvins have the function of treating metabolic diseases and their complications, mainly diabetes, which illustrates the therapeutic potential of resolvins in the field of metabolic disorders [52, 88–94].

Protectin D1 (PD1), currently the most active protectin, also referred to as neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1), which in vivo possesses a potent anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective activity in its localized tissues (Table 1) [83, 95]. The main PD1 precursor, DHA, exists mainly in tissues such as the retinal synapses, photoreceptors, the lungs, and the brain, implying that PD1 are supposed to protect these tissues most possibly and less likely to participate in metabolism [96–98]. However, PD1 exerts a protective effect against metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) in mice by suppressing the activation of TLR4-mediated downstream signaling pathways [99]. Moreover, protectin DX (PDX), an isomer of PD1, has been demonstrated to alleviate insulin resistance in db/db mice and simultaneously optimize core parameters linked to the diabetic condition in T1DM mouse model [100, 101]. In addition, White et al. [102] reported that both PD1 and PDX were capable of modulating PPARγ transcriptional activity, which showed their potential of anti-obesity and anti-diabetes.

At present, there are mainly three kinds of maresins found, namely maresin 1, maresin2, and maresin-Ls (can be divided into maresin-L1 and maresin-L2), which all derive from DHA, and possess robustly anti-inflammatory, pro-resolving, protective, and pro-healing properties similar to other SPMs (Table 1) [72, 103, 104]. Martínez-Fernández et al. [105] suggested that treatment with maresin 1 can improve insulin sensitivity and attenuate adipose tissue inflammation in ob/ob and diet-induced obese mice. In addition to the anti-inflammatory effects of maresin 1, some studies believe that the ability to regulate FGF21 contributes to its beneficial metabolic effects [106]. Jung et al. [107] confirmed that maresin 1 can ameliorate liver steatosis by decreasing lipogenic enzymes in ob/ob and diet-induced obese mice, which showed that maresin 1 may be a practical therapeutic strategy to treat MAFLD [107, 108]. In addition, maresin 1 modulates the basal expression levels of adipokines in human adipocytes and mitigates the TNF-α-induced aberrations in adipokine expression under in vitro conditions, and such regulatory effects may underlie the metabolic advantages exerted by this lipid mediator [109].

Current insights into SPMs provide a clear roadmap for developing clinical treatment strategies that address the root of metabolic disorders—metaflammation—while avoiding the limitations of traditional anti-inflammatory therapies. These strategies prioritize restoring SPM function, leveraging their ability to resolve inflammation without immunosuppression, and can be tailored to target obesity, T2DM, and MAFLD specifically. SPMs have emerged as latent regulators in physiological pathways of resolution and chronic inflammation that can improve obesity, T2DM, MAFLD, and other metabolic diseases [87, 107, 110] beyond the roles of their precursors in metabolism and membrane dynamics. In view of the ability of SPMs to initiate inflammation resolution without immunosuppression, it is promising that therapeutic delivery of lipid agonists in the form of SPMs may be a prospective strategy for alleviating the resolving failure and remodeling homeostasis in chronic metabolic diseases, including obesity, T2DM, MAFLD, as well as CVD, and so on [87, 90, 107]. Here, we can imagine a future where SPMs are well understood, play a role in distinct metabolic diseases, and serve as supplements to existing therapeutic strategies.

The global epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes are fundamentally fueled by a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation known as metaflammation, which disrupts metabolic health across multiple organs. SPMs, such as resolvins and maresins, represent the body's own sophisticated system for actively shutting down this inflammation, which goes beyond mere suppression to orchestrate complete resolution and tissue repair. In obesity, this natural defense is compromised; a combination of impaired SPM production and tissue resistance creates a resolution deficit, allowing inflammation to persist and drive metabolic deterioration. While human data primarily show correlation, animal studies robustly demonstrate that restoring specific SPM levels can directly improve insulin sensitivity, reduce liver fat, and calm adipose tissue inflammation. This reveals a profound therapeutic potential: instead of broadly suppressing immune responses, we can aim to treat metabolic disease by replenishing these native resolution signals. The future lies in leveraging these findings to develop strategies that reignite the body’s innate ability to resolve inflammation, thereby restoring metabolic equilibrium from within.

CVDs: cardiovascular diseases

DHA: docosahexaenoic acid

EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid

MAFLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

PD1: protectin D1

PDX: protectin DX

PMN: polymorphonuclear neutrophil

PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acid

SPMs: specialized pro-resolving mediators

T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus

TLR4: toll-like receptor 4

TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α

Images in Figure 1 and Figure 2 are provided by Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/) and are licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

ZWZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. The author read and approved the submitted version.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 698

Download: 26

Times Cited: 0