Affiliation:

1Peptide Science Laboratory, School of Chemistry and Physics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

Email: Sharmaa@ukzn.ac.za

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1282-5838

Affiliation:

2Department of Math and Sciences, College of Humanities and Sciences, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh 11586, Saudi Arabia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7988-7358

Affiliation:

1Peptide Science Laboratory, School of Chemistry and Physics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

3School of Laboratory Medicine and Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5632-2293

Affiliation:

3School of Laboratory Medicine and Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8521-9172

Affiliation:

1Peptide Science Laboratory, School of Chemistry and Physics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

4Department of Inorganic and Organic Chemistry, University of Barcelona, 08193 Barcelona, Spain

Email: Albericio@ukzn.ac.za

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8946-0462

Affiliation:

5Department of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Dar Al Uloom University, Riyadh 11512, Saudi Arabia

6Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Alexandria University, Alexandria 21321, Egypt

Email: ayman.a@dau.edu.sa

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3951-2754

Explor Drug Sci. 2026;4:1008149 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2026.1008149

Received: December 09, 2025 Accepted: February 01, 2026 Published: February 11, 2026

Academic Editor: Kamal Kumar, Smartbax GmbH, Germany

The article belongs to the special issue The Role of Triazine Scaffolds in Modern Drug Development

The s-triazine scaffold has emerged as a privileged heterocyclic nucleus/moiety in pharmaceutical discovery and development, owing to its presence in several natural products and clinically relevant therapeutic agents, including enasidenib, gedatolisib, bimiralisib, atrazine, indaziflam, and triaziflam. s-Triazine derivatives are not only economically accessible and synthetically versatile, but they also exhibit a broad spectrum of noteworthy biological activities, encompassing anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antidiabetic, anticonvulsant, antitubercular, and antimicrobial properties. Their widespread utility is further supported by the ease of synthesis from inexpensive precursors such as amidines or the readily available 2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine (cyanuric chloride), which enables sequential functionalization and the rapid generation of diverse analogues. The heightened reactivity and modularity of the s-triazine core have facilitated the development of structurally rich heterocyclic hybrids with enhanced potency and improved pharmacological profiles. These multitarget-directed systems offer exciting opportunities for addressing various forms of cancer. Considering the increasing pace of innovation in this field, a comprehensive overview of recent advancements in s-triazine-based hybrid molecules is both timely and necessary. This review highlights current progress, key design strategies, and emerging perspectives to inspire continued efforts toward the identification of promising s-triazine-based lead candidates for future drug development as anticancer agents.

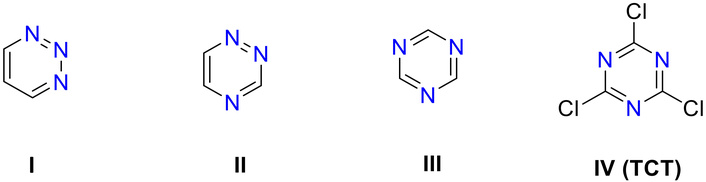

Triazines constitute an important class of heterocyclic scaffolds exhibiting diverse biological activities [1–4]. Depending on the arrangement of nitrogen atoms, three structural isomers exist, namely 1,2,3-triazine (I), 1,2,4-triazine (II), and 1,3,5-triazine (III). Among these, 1,3,5-triazine (s-triazine; III) occupies a distinctive position in medicinal chemistry, attributed to its symmetrical framework and the facile accessibility of a wide variety of derivatives [5, 6]. These derivatives can be obtained either directly from simple precursors or indirectly from commercially available intermediates such as cyanuric chloride [2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine (TCT), IV] (Figure 1).

Isomeric structures of triazine moiety (I–III) and structure of cyanuric chloride (IV), a main precursor for the synthesis of biologically active compounds. TCT: 2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine.

The s-triazine nucleus is a six-membered aromatic heterocycle containing three symmetrically positioned nitrogen atoms [7]. This symmetrical arrangement not only imparts remarkable chemical stability but also provides multiple sites for functional modification. A key advantage of this scaffold lies in its availability from cyanuric chloride (TCT), a low-cost and commercially accessible intermediate [1, 8–10]. Cyanuric chloride possesses three reactive chlorine atoms that undergo sequential substitution at different temperatures, enabling the stepwise introduction of diverse nucleophiles such as amines, alcohols, and thiols [10–12]. This synthetic versatility makes the s-triazine core an attractive platform for the design and optimization of bioactive molecules with tailored physicochemical and pharmacological profiles.

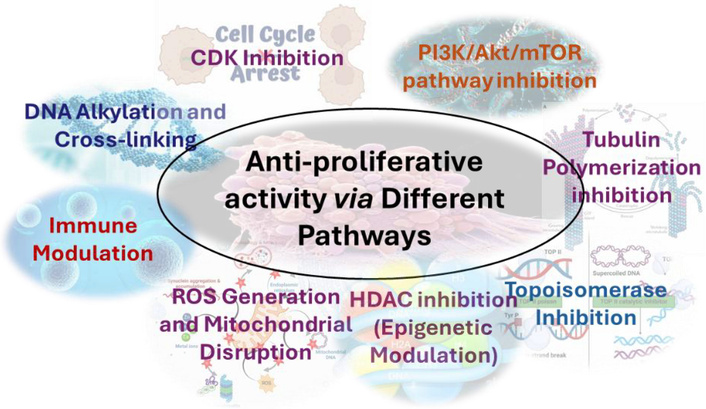

In pharmaceuticals, s-triazine derivatives have been extensively explored for antiviral, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities, with notable examples including clinically and agriculturally relevant agents such as atrazine and related analogues. Beyond drug discovery, s-triazines play a pivotal role in agriculture as herbicides and crop-protection agents, while their electron-deficient aromatic core has enabled broad applications in materials science, including high-performance polymers, organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), dyes, and textile finishes [13–17]. Additionally, the strong coordination ability of nitrogen-rich triazine frameworks has been exploited in chelating agents and metal-decorated triazine systems, which have recently emerged as promising platforms for hydrogen storage and transport [16, 17]. The substitution flexibility of the s-triazine ring allows the conjugation of multiple pharmacophores, facilitating the development of multifunctional agents that can target various pathways involved in tumor progression. s-Triazine derivatives have emerged as a versatile class of heterocyclic compounds with significant promise in anticancer drug development [18]. The structural adaptability of the s-triazine nucleus allows for fine-tuning of lipophilicity, hydrogen bonding, and electronic effects, enabling selective targeting of key oncogenic pathways [18]. Consequently, s-triazine derivatives continue to serve as promising scaffolds for designing multi-target anticancer therapeutics. Their substituted s-triazine scaffold allows for extensive structural modifications, enabling targeted inhibition of key oncogenic pathways such as phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and tyrosine kinases [18–22]. In the context of oncology, the s-triazine scaffold has attracted significant attention owing to its ability to generate compounds with potent cytotoxic and antiproliferative activities. Figure 2 depicts various pathways by which the s-triazine scaffold can lead to apoptosis/anti-proliferative activity.

Various targets of the s-triazine scaffold for potent anticancer activity. CDK: cyclin-dependent kinase; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinases; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; HDAC: histone deacetylases.

Figure 3 shows the most common s-triazine ring-containing and FDA-approved drugs containing the s-triazine core. Table 1 enlists some FDA-approved drugs and some biologically active molecules containing the s-triazine core. Clinically, the most notable example is altretamine (Hexalen®), an alkylating agent approved for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer, which underscores the therapeutic relevance of this scaffold [23, 24]. Other triazine derivatives have advanced into clinical and preclinical studies, further validating their role as a privileged heterocycle in anticancer therapy. Clinically approved agents like altretamine, gedatolisib, and enasidenib exemplify their therapeutic relevance across ovarian cancer, metastatic breast cancer, and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [19, 25, 26]. Unfortunately, ZSTK474 has been withdrawn from clinical trials due to its resistance and on-target/off-tumor side effects [27]. Recent studies highlight the potent cytotoxicity of symmetrical di-substituted phenylamino-s-triazines against breast and colon cancer cell lines, with IC50 values in the sub-micromolar range [22]. In silico docking analyses further support their high affinity for cancer-related targets including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), and mTOR, underscoring their potential as multi-targeted anticancer agents [22]. The ease of synthesis, particularly via microwave-assisted methods, and their broad-spectrum activity position s-triazine derivatives as promising candidates for next-generation chemotherapeutics [28].

Some drugs are FDA-approved and some active s-triazine biologically active species.

| Compound/Code | Clinical status | Cancer type/target | Key features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altretamine (Hexalen®) | 1990; FDA-approved | Recurrent ovarian cancer | Alkylating agent; induces DNA damage leading to apoptosis | [23] |

| Tretamine (Persistol) | Not FDA-approved | Anti-neoplastic | Alkylating agent induces cross-linking of DNA, thus inhibiting DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis | [29, 30] |

| Azacitidine (Vidaza) | 2004; FDA-approved | Anti-neoplastic agent | Hypomethylation of cytosine residues in newly synthesised DNA by inhibiting DNA methyltransferase | [31] |

| Almitrine (Duxil) | Not FDA-approved | Respiratory stimulant | Acting as an agonist of peripheral chemoreceptors located on the carotid bodies | [32] |

| Enasidenib (Idhifa) | 2017; FDA-approved | Refractoryacute myeloid leukemia (AML), anti-leukemia | Isocitrate dehydrogenase-2 (IDH2) inhibitor | [26] |

| Gedatolisib | Not FDA-approved | Anti-breast cancer | PI3K/mTOR inhibitor by blocking the PI3K/Akt/mTOR (PAM) pathway | [19] |

| Bimiralisib | Not FDA-approved | Anti-breast cancer | Dual inhibitor of the PI3K and mTOR signaling pathways | [18] |

| ZSTK474 | Not FDA-approved | Anti-cancer | PI3K inhibitor that targets signal transduction pathways | [27, 33] |

| Zandelisib | Not FDA-approved | Indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (iB-NHL) | Inhibitor of the PI3K delta pathway | [34] |

| Melarsoprol (Arsobal) | Not FDA-approved | Anti-trypanosomiasis | Inhibits parasitic glycolysis | [35] |

| Tretazicar (Prolarix) (CB1954 prodrug activator) | Not FDA-approved | Anticancer prodrug, anti-Leishmanial | s-Triazine derivative used as an enzyme-activated prodrug system, inhibits DNA replication after activation | [36] |

| Bendamustine-triazine hybrids (Treanda) | 2008; FDA-approved | Leukemia, lymphoma | Combines alkylating function with triazine core for enhanced cytotoxicity | [37, 38] |

PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinases; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin.

Given the increasing prominence of s-triazine derivatives, substantial research efforts have focused on the design of novel drug candidate libraries through the hybridization of the s-triazine core with a diverse array of well-established heterocyclic scaffolds. In this context, a timely and comprehensive overview of recent developments is essential not only to engage the drug discovery community but also to highlight existing gaps and opportunities that may steer the rational design of more potent s-triazine-based hybrid molecules.

s-Triazine derivatives can be prepared either using cheap and readily available reagents or from cyanuric chloride as a starting point. The section below describes both procedures: Section Synthesis of s-triazine derivatives from cheap and readily available reagents enlists the common procedures used for the synthesis of s-triazine derivatives, while section Synthesis of s-triazine derivatives from cyanuric chloride showcases the derivatives prepared from cyanuric chloride.

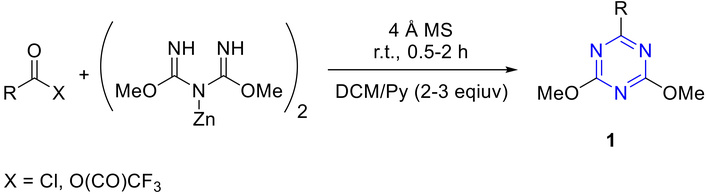

Diverse synthetic methodologies enable the preparation of s-triazine derivatives from inexpensive, readily available precursors [1]. The following section discusses the trisubstituted and disubstituted triazine derivatives. For instance, from zinc dimethyl imidodicarbonimidic by reacting it with activated acid derivatives in a mixture of solvents, dichloromethane (DCM) and pyridine, in the presence of 4 Å molecular sieves (4 Å MS) to give 3,5-dimethoxy-s-triazine derivatives 1 as described in Figure 4 [39].

Synthesis of 3,5-dimethoxy-s-triazine derivatives (1). 4 Å MS: 4 Å molecular sieves; r.t.: room temperature; DCM: dichloromethane.

Pinner [40] reported the synthesis of 2-hydroxy-4,6-diaryl-s-triazine derivatives (2 and 3). These derivatives were obtained through the interaction of phosgene with aryl amidines and halogenated aliphatic amidines, respectively (Figure 5).

Shie and Fang [41] described the synthesis of s-triazine derivatives using microwave irradiation (MW). In this process, primary alcohols or aldehydes react with iodine in aqueous ammonia to produce intermediate nitriles. These nitriles subsequently interacted with dicyandiamide and NaN3 to yield the corresponding s-triazines (4) with good yield (Figure 6).

Simons and Saxton [42] reported the synthesis of diamino-s-triazine derivatives 5 from the reaction of cyanamide or cyanogen chloride with benzonitrile, as shown in Figure 7.

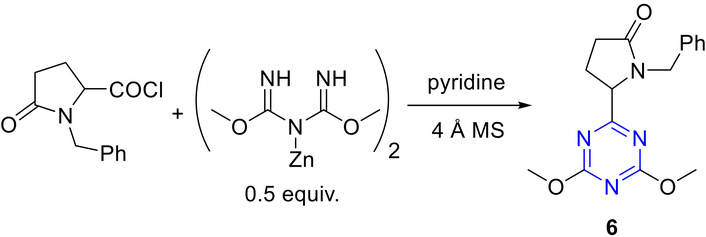

Oudir et al. [39] reported the synthesis of 6-substituted 2,4-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazines (6) through the reaction of activated carboxy groups, such as acid chlorides, anhydrides, acylimidazolides with zinc dimethyl imidodicarbonimidates (Figure 8). Notably, good yields were achieved when a very large excess of the carboxylic acid derivative was utilized. Under similar experimental conditions, the reaction of acid chloride with zinc salt resulted in the corresponding triazine, yielding a moderate 53%. Enhanced yields were obtained when the acid chloride was condensed with the salt in the presence of 4 Å MS and pyridine as the solvent.

Synthesis of 6-substituted 2,4-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazines (6). 4 Å MS: 4 Å molecular sieves.

A series of 2,4,6-trisubstituted triazines (7) was synthesized and evaluated for antiproliferative activity against HEK-293 and IMR-32 cell lines, along with their binding affinity toward the histamine H4 receptor (H4R). The synthetic route to these novel compounds is outlined in Figure 9 [43]. The target triazines were synthesized through the reaction of the corresponding esters with biguanidine dihydrochloride, which itself was generated by heating cyanoguanide with 4-methylpiperazine dihydrochloride in n-butanol.

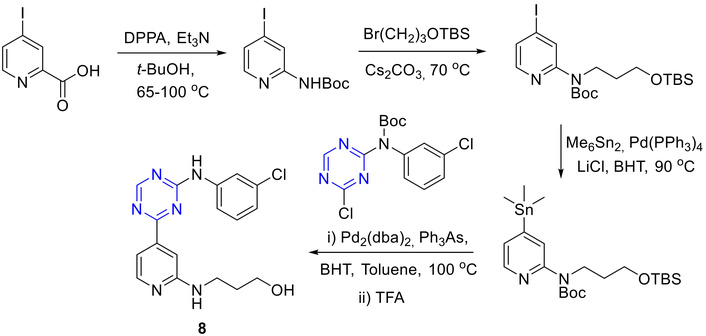

Other derivatives of s-triazine are also reported using commercially available materials [1, 26]. Disubstituted s-triazine derivatives were prepared from readily available starting materials. Kuo et al. [44] reported the synthesis of 8 wherein the Curtius rearrangement followed by alkylation was conducted. The intermediate was then subjected to organostannane formation. The following reactions were palladium-catalyzed Stille coupling reactions with respective chloride and then followed by trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) deprotection to afford final product 8 as shown in Figure 10.

Synthesis of triazine-4-pyridine analogue (8). DPPA: diphenyl phosphorazidate; BHT: butylated hydroxytoluene; TFA: trifluoroacetic acid.

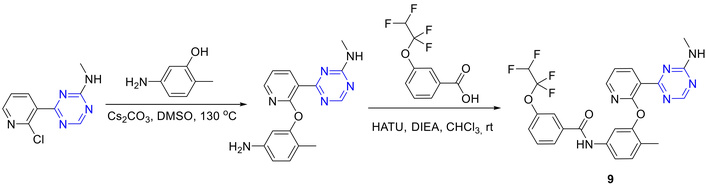

Hodous et al. [45, 46] reported the ‘reversed-amide’ synthesis wherein coupling was performed of respective carboxylic acid using hexafluorophosphate azabenzotriazole tetramethyl uronium (HATU) as condensing agent to afford 9 over two steps (Figure 11).

Synthesis of pyridinyl pyrimidine analogue (9). HATU: hexafluorophosphate azabenzotriazole tetramethyl uronium; DIEA: diethylisopropoyamine; rt: room temperature.

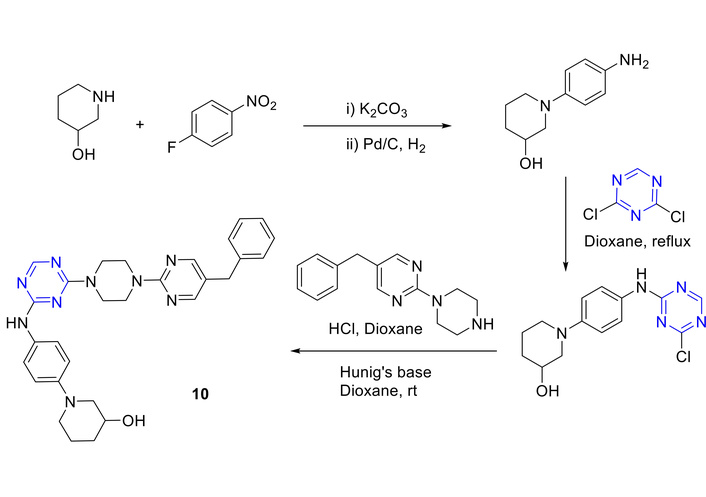

The 4-fluoronitrobenzene was reacted with piperidin-3-ol in the presence of potassium carbonate, followed by reduction using Pd/C and hydrogen, to form 1-(4-aminophenyl)piperidin-3-ol. This was further reacted with dichlorotriazine to form 1-(4-((4-chloro-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)amino)phenyl)piperidin-3-ol. Upon reaction with 5-benzyl-2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyrimidine, the final product 1-(4-((4-(4-(5-benzylpyrimidin-2-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)amino)phenyl)piperidin-3-ol (10) was obtained as shown in Figure 12 [46].

Synthesis of disubstituted s-triazine-pyrimidine analogue (10). rt: room temperature.

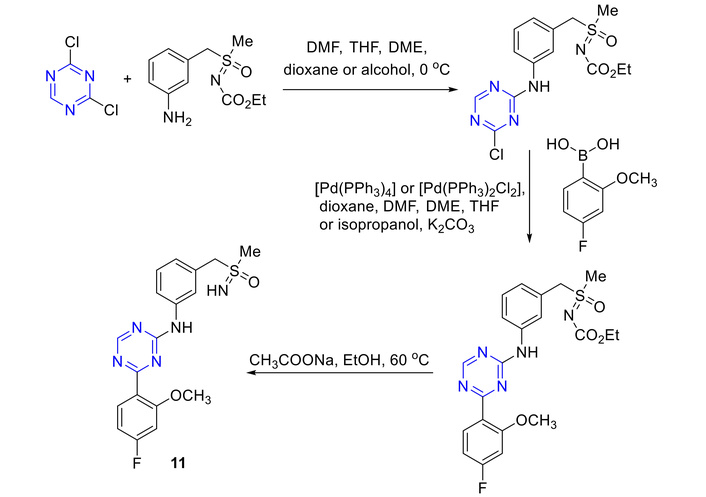

The disubstituted s-triazine 11 synthesis commenced with the reaction of 2,4-dichloro-s-triazine with a substituted aniline to afford the corresponding intermediate. This intermediate subsequently underwent a Pd-catalyzed coupling with a boronic acid to yield the s-triazine derivatives, which upon deprotection furnished triazine 11, as depicted in Figure 13 [47, 48].

Synthesis of disubstituted s-triazine (11) for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide; THF: tetrahydrofuran; DME: dimethoxyethane.

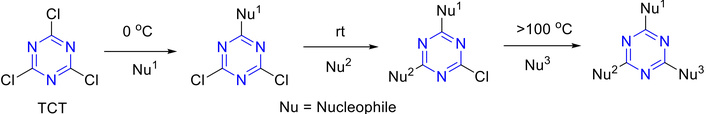

As illustrated in Figure 14, s-triazine derivatives can be efficiently synthesized from the inexpensive and commercially available cyanuric chloride (TCT). The three electrophilic chlorine atoms of TCT render it an adaptable platform for the assembly of biologically active leads, multitopic molecules, and molecular hybrids that contain an s-triazine core. Nucleophilic species (N-, O-, or S-based) readily displace the chlorine atoms via an SNAr mechanism; by tuning base and temperature, stepwise selective substitution can be achieved [1]. As TCT is readily accessible and allows for selective functionalization on the aromatic ring, this approach has been widely adopted across medicinal chemistry and material science research, as well as in the production of various commercial products [1].

Nucleophilic substitution reaction of TCT. TCT: 2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine; rt: room temperature.

The protocol has been successfully applied to the preparation of trisubstituted s-triazines, while uncondensed analogues featuring one or more amino substituents at the 2, 4, or 6 positions have likewise been extensively investigated as anticancer compounds, exhibiting a variety of mechanisms of action [1].

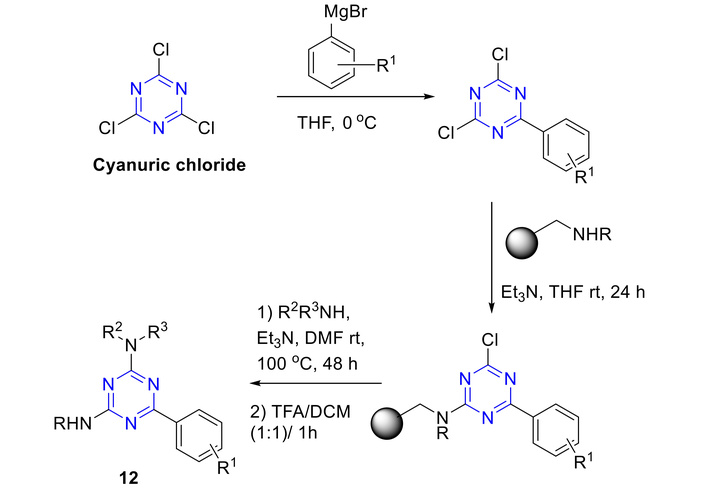

Amino-s-triazine derivatives have also been accessed using combinatorial chemistry strategies. In particular, 2,4-diamino-6-aryl-s-triazines (12) were synthesized via a solid-supported method, wherein mono-aryl-substituted triazines were directly obtained from the crude reaction mixture using resin-bound amines, as illustrated in Figure 15 [49]. The treatment of TCT with aryl-magnesium bromide resulted in the formation of a mixture of mono- and di-aryl-substituted s-triazine derivatives. The mono-aryl-substituted triazine was selectively attached to the resin via nucleophilic substitution to yield the resin-bound intermediate, which was then heated at 100°C with amines in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) to afford the disubstituted triazine. 2,4-Diamino-6-aryl-s-triazines (12) have been released by treatment with TFA in DCM (1:1).

Synthesis of amino diaryl s-triazine derivatives (12). THF: tetrahydrofuran; rt: room temperature; DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide; TFA: trifluoroacetic acid; DCM: dichloromethane.

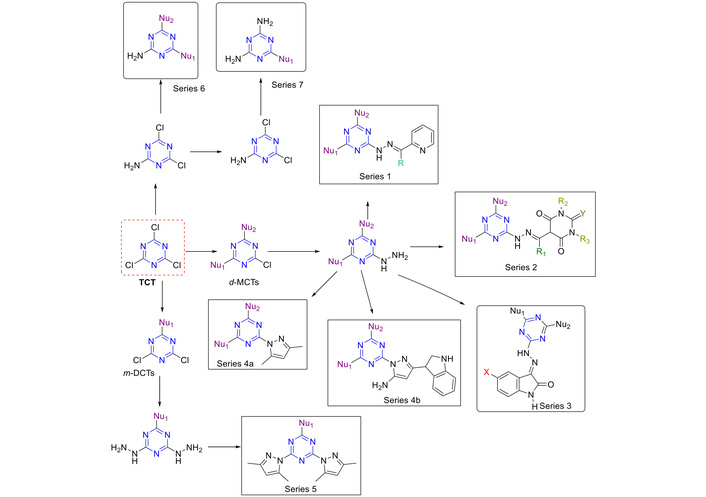

Figure 16 depicts several approaches to prepare trisubstituted s-triazine derivatives. Hydrazone containing s-triazine hybrid derivatives (Figure 16, series 1, 2, and 3) were synthesized [50–53]. Disubstituted monochloro s-triazines (d-MCTs) were synthesized using different nucleophiles (such as piperidine and morpholine or aniline) with NaHCO3 as the base. The first Cl atom was replaced at 0°C. The second one was replaced in situ by performing the reaction at room temperature overnight. The obtained product was then reacted with hydrazine using ethanol as the solvent to afford the desired product (hydrazinyl s-triazine derivatives). A Schiff base was made using carbonyl derivatives (aldehydes or ketones) in ethanol and acetic acid as a catalyst to afford the product of interest (Figure 16, series 1, 2, and 3).

Synthesis of s-triazine derivatives via different routes affording a library of compounds as part of different series. TCT: 2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine; d-MCTs: disubstituted monochloro s-triazines; m-DCTs: monosubstituted dichloro s-triazines.

Pyrazole derivatives (Figure 16, series 4 and 5) were synthesized as previously reported [51, 54], where initially, monosubstituted dichloro s-triazines (m-DCTs) and d-MCTs derivatives bearing ammonia, piperidine, benzyl amine, morpholine, or aniline derivatives were prepared as explained above. Hydrazine, upon reaction with m-DCTs/d-MCTs afforded di/mono-hydrazinyl trisubstituted s-triazine. These compounds were dissolved in DMF and acetylacetone in the presence of triethylamine (TEA), or reacted with acetylacetone in aqueous HClO4 [51], or reacted with acetylacetone in ethanol-acetic acid mixture (20%) to afford the desired products (Figure 16, series 4 and 5) [54]. Among the above-mentioned methods, the reaction in 20% acetic acid in ethanol afforded a higher yield and purity [54].

To enhance interactions with the N-terminal of the enzyme, Lee and Seo [55] synthesized novel 2-amino-1,3,5-triazines (Figure 16, series 6 and 7, and Figure 17, series 8, 9, and 10) by retaining a chlorine atom at the 4-position and introducing hydrophobic aryl groups such as benzyl ethers, aryl ethers, and aryl amines at the 6-position. The resulting 2-amino-4-chloro-6-substituted-s-triazines were prepared as outlined in Figure 17.

First, TCT reacted with derivatives of benzyl alcohol, anilines, and phenols in the presence of 2,6-lutidine as a base at room temperature, yielding the corresponding 2,4-dichloro-6-substituted-s-triazines. This was followed by reaction with ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) in acetone/H2O at room temperature, which led to the formation of the target 2-amino-4-chloro-6-substituted-s-triazines (Figure 17, series 8, 9, and 10) [56, 57]. These series could be used for the synthesis of 2-amino-disubstituted-s-triazine derivatives [57].

The heterocycle 1,3,5-triazine, which features nitrogen atoms in its core structure, has been reported to exhibit diverse biological activities, including anticancer effects. The substituents attached to the 2-, 4-, and 6-positions of the ring significantly influence the compound’s activity [1, 6].

Compound 8 exhibited potent antiproliferative activity both in vitro and in vivo. In vitro studies indicated its ability to inhibit the growth of multiple cancer cell lines, including HeLa, U937, HCT-116, and A375, with IC50 values ranging from 23 to 33 nM. In vivo, Compound 8 showed efficacy in a human melanoma (A375 xenograft model). In U937 cells, 8 induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner via caspase activation. Notably, 8 demonstrated comparable activity against the drug-sensitive MES-SA cell line and the multidrug-resistant, P-glycoprotein-overexpressing MES-SA/Dx5 cells indicating that it is not a substrate for the P-glycoprotein drug efflux pump. When evaluated against a panel of kinases, 8 exhibited broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against CDKs, showing high potency toward CDK1, CDK2, and CDK5, and submicromolar activity against CDK4, CDK6, and CDK7. Additionally, 8 displayed strong inhibition of GSK-3β (IC50 = 0.020 µM) while exhibiting weak or no activity against 12 non-CDK kinases [44]. Compound 9 inhibited the phosphorylation of the serine/threonine kinase (p38α) and the non-receptor tyrosine kinase (Lck), with IC50 values of 47 nM and 146 nM, respectively. Furthermore, it displayed favorable pharmacokinetic properties in rats, including a half-life of 1.7 h and a clearance rate of 889 mL/h/kg [45, 46]. Compound 10 also shows observable antitumor activity against the mouse mastocytoma cancer model P815 [46]. Compound 11, the (þ) enantiomer of (3-((4-(4-fluoro-2-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)amino)benzyl)(imino)(methyl)-λ6-sulfanone, is currently being evaluated in clinical development for treatment of AML [47, 48]. The 2,4-diamino-6-aryl-1,3,5-triazines (12) exhibited potent antiproliferative activity against tumor cell lines K562, PC-3, and HO8910. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis showed the influence of the presence of a piperazine moiety in the substituents, which enhanced the inhibition of tumor cell growth.

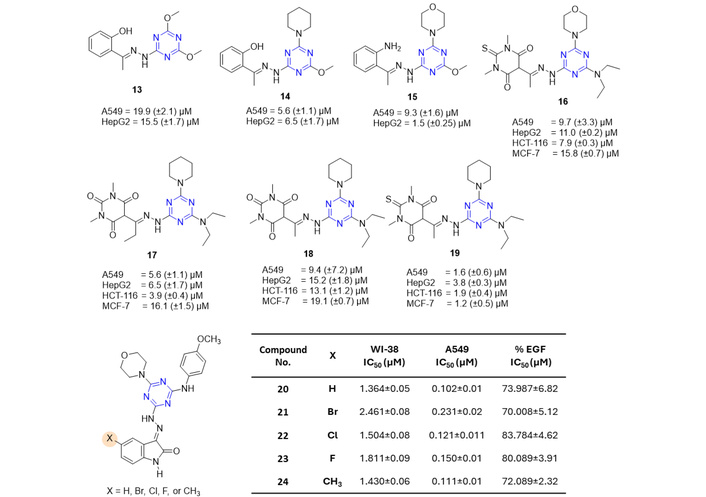

Figure 18 showed various hydrazone derivatives with their promising anticancer activities (a total of twelve compounds from series 1, 2, and 3, as shown in the scheme in Figure 16) [50, 52]. These series were evaluated for anticancer activity against various cell lines, including lung carcinoma cell line (A549), the hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cell line, breast carcinoma cell line (MCF-7), and human colorectal carcinoma (LoVo, HCT-116). Out of all tested compounds from series 1, three derivatives (13–15, Figure 18) showed anticancer activity against A549 and HepG2. None of the compounds showed activity against MCF-7. Further from series 2, four derivatives (16–19, Figure 18) displayed anticancer activity against all the cell lines.

Hydrazone linker-based s-triazine derivatives (13–24), which are active against the tested anticancer strains. EGF: epidermal growth factor.

Another class of hydrazone-based linkers, comprising hybrid s-triazine-isatin derivatives (series 3; comprising 50 compounds based on several substitutions on the s-triazine core and on the isatin unit, as shown in Figure 16), exhibited cytotoxic effects against Human Caucasian foetal lung (WI-38) and A549 cell lines. Out of all the tested 50 compounds, five compounds (20–24, Figure 18) showed notable anticancer activity. Most derivatives demonstrated activity and safety indices comparable to or exceeding those of sorafenib, with the compounds displaying the highest selectivity indices also showing greater potency than sorafenib. Additionally, all compounds exhibited broad-spectrum anti-trypsin activity. SAR analysis revealed that the nature of substituents on both the s-triazine and isatin cores significantly influenced cytotoxicity, selectivity index (SI), and inhibition of trypsin, factor Xa, and EGF [53].

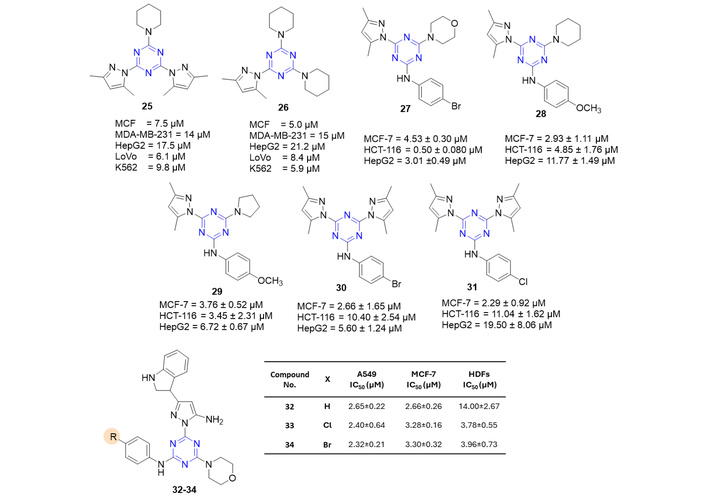

Pyrazole derivatives from series 4a, series 4b, and series 5 (scheme shown in Figure 16) [54, 58] were evaluated against human chronic myeloid leukemia cells (K562), human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7), human breast adenocarcinoma (MDA-MB-231), human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), and human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (LoVo) [58]. Compounds 25 and 26 (Figure 19) were found to be active in inhibiting the cell survival of MCF-7, HepG2, LoVo, and K562. These two compounds further caused a delay in embryonic development observed in zebrafish. Cell cycle analysis in K562 cells suggested that they exert their action by causing S and G2/M phase cell cycle arrest. The reason for the activity could be attributed to the presence of piperidinyl moieties in their structure.

Pyrazolyl-s-triazines trisubstituted derivatives (25–34), which are active against the tested anticancer strains. HDFs: human dermal fibroblast.

In another report, out of all eleven pyrazole derivatives, 27–31 (Figure 19) showed potent activity against MCF-7 cells, showing an IC50 between 2.29 and 5.53 µM [59]. Amongst, 27 exhibited EGFR inhibition activity, with an IC50 value of 61 nM. Additionally, for the downstream pathway of PI3K/Akt/mTOR, 27 showed notable inhibitory activity, reducing the expression of these genes 0.18, 0.27, and 0.39-fold, respectively. Compound 27 was reported to induce apoptosis in HCT-116 cells by upregulating the proapoptotic genes p53, Bax, and caspase-3, -8, and -9, while it downregulated the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2 [59]. Another pyrazole series (series 4b), containing an indole moiety, was also synthesized [54]. Among the eleven derivatives, only three 32–34 (structures shown in the last part of Figure 19) were found to be active against cell lines A549, MCF-7, and non-cancerous human dermal fibroblast (HDFs).

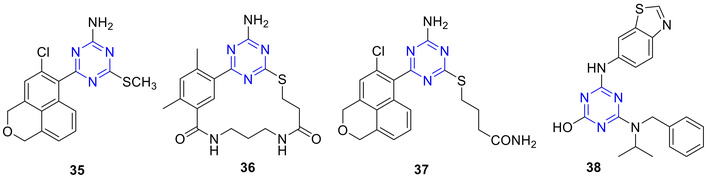

Several 2-amino-1,3,5-triazines (Figure 20) were synthesized as adenine mimics of ATP. Through a blend of fragment-based screening, virtual screening, and structure-based drug design, Miura et al. [56] identified novel orally active 2-amino-s-triazines as heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) inhibitors. Compound 35, featuring a 2-amino-s-triazine core with an S-methyl group at C-4 and an ortho-chloro-substituted tricyclic group at C-6 (Figure 20), inhibited the in vitro growth of HCT-116 and HER2-overexpressing National Cancer Institute (NCI)-N87 cells with IC50 values of 0.46 and 0.57 µM, respectively. In vivo, oral administration of 35 (400 mg/kg) resulted in 54% tumor volume inhibition in an NCI-N87 xenograft model. Furthermore, it induced dose-dependent downregulation of Hsp90 client proteins, including Her2, Raf1, and pERK [56, 60]. To further optimize the structure of 35, Suda et al. [61] synthesized a new macrocyclic series of 2-amino-6-aryl-s-triazines incorporating a pyrimidine (36), replacing the sulfur methyl group with H-bond acceptors capable of Lys58 interaction, a residue involved in H-bonding with the natural Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin. Among the synthesized compounds, 37 exhibited the most potent in vitro and in vivo antiproliferative activity along with the highest enzyme affinity (Kd = 0.48 nM). Moreover, 37 showed an improved pharmacokinetic profile and greater systemic exposure compared with 35.

Amino-s-triazine derivatives (35–38), which are active against HCT-116 and HER2-overexpressing NCI-N87 cells, and 38 as a potent inhibitor of VEGF-R2 tyrosine kinase (flk-1/KDR).

The 2-hydroxy-4,6-diamino-s-triazines (38) (Figure 20) demonstrated potent inhibitory activity against VEGF-R2 tyrosine kinase (flk-1/KDR) [62]. Among them, 4-(benzothiazol-6-ylamino)-6-(benzyl-isopropylamino)-s-triazin-2-ol (38) exhibited the strongest in vitro activity, with an IC50 of 0.018 µM against KDR. Compound 38 also showed good selectivity toward Tie-2 (IC50 = 0.18 µM), a profile that could be advantageous in developing dual KDR/Tie-2 inhibitors with enhanced in vivo antiangiogenic efficacy.

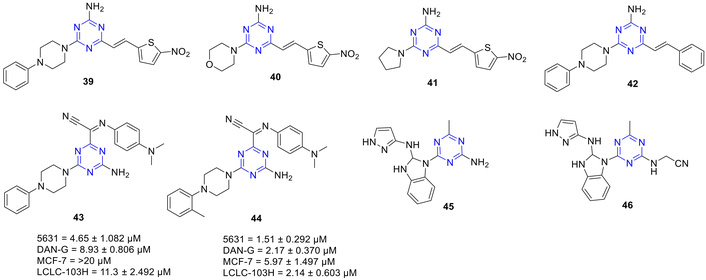

Saczewski and Bułakowska [63] demonstrated that compound 39 (Figure 21) exhibited better than average selectivity towards renal cancer cell lines (A498) and melanoma cell lines (SKMEL-5), whereas compounds 40 and 41 showed selective potency against colon cancer cell line (COLO 205) and melanoma cell line (LOXIMVI) [63]. Further, nine derivatives containing amino-s-triazines were synthesized and evaluated against human bladder cancer [5637 (HTB-9)], MCF-7, human pancreatic cancer (DAN-G), and human non-small cell lung cancer (LCLC-103H). Among the 6-alkenyl-s-triazines obtained via Wittig olefination of aldehydes, 42 exhibited selective antiproliferative activity against the renal cancer cell line A498 (IC50 = 0.074 µM), while 41 (Figure 21) demonstrated particular potency against the colon cancer cell line COLO 205 (IC50 = 95 nM) [64]. Of nine derivatives evaluated, compounds 43 and 44 were the most active [64]. Compound 43 showed notable efficacy against the MALME-3M cell line (IC50 = 0.033 µM) and IC50 values of 4.65–20 µM across 5637 (bladder), MCF-7 (breast), DAN-G (pancreatic), and LCL-103H (lung) cell lines. The highest antiproliferative activity was observed for 44 with IC50 values of 1.51–5.97 µM in the same cell lines. These results highlight the importance of a lipophilic, weakly electron-donating substituent at the 2-position of the phenyl ring for enhancing antiproliferative activity [64].

Amino-s-triazine derivatives (39–46), which are active against the tested anticancer strains.

Numerous studies have reported anticancer amino-s-triazines that act as mTOR kinase inhibitors. mTOR is a critical downstream regulator in growth factor signaling and the PI3K/Akt pathway, controlling key cellular processes including autophagy, apoptosis, cell cycle progression, and cytoskeleton organization [65]. Dysregulated mTOR activity has been observed in various human diseases, particularly multiple cancer types, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target [65]. Using this insight, Peterson et al. [66] identified benzimidazolyl-s-triazines (45 and 46; Figure 21) as a promising scaffold for the development of selective mTOR inhibitors. Compound 45 demonstrated the best combination of potency and selectivity with an IC50 = 0.027 µM for the inhibition of mTOR and was found to be 30-fold selective over PI3Kα. However, its therapeutic potential was found to be significantly compromised by extensive glucuronidation, which led to the rapid clearance and poor systemic exposure [66]. To optimize activity, substitutions on the amine group were explored, and 46 was found to be the most potent and selective, with an IC50 of 0.031 µM. It exhibited 200-fold and 100-fold selectivity over PI3Kα and other PI3K isoforms, respectively. Remarkably, 46 demonstrated exceptional mTOR specificity, showing no binding to any of the 402 kinases tested in an Ambit binding assay at 1 µM, except for TGFBR2 [66].

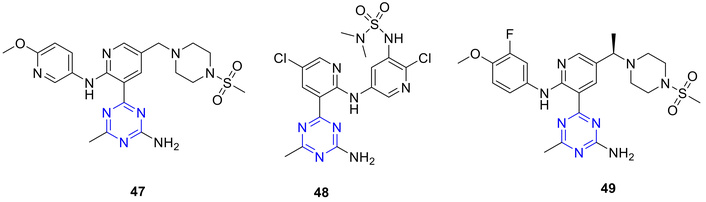

The PI3K family aids in the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate. Substantial evidence indicates that the PI3K/Akt pathway plays a central role in tumor development and in determining tumor response to anticancer therapies [67]. In this context, a series of 4-amino-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazine sulfonamides (47–49; Figure 22) were synthesized, followed by evaluation as dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors, exhibiting improved pharmacokinetic profiles and oral bioavailability [68, 69].

4-Amino-6-methyl-s-triazine sulphonamides (47–49), which were evaluated as dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors. PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinases; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin.

Compound 47 exhibited exceptional selectivity against 98 kinases tested by showing minimal inhibition at 1 µM. It displayed high selectivity within the PI3K family, including class II PI3Ks (PIK3C2α IC50 > 10 µM; PIK3C2β IC50 = 29 nM), class III PI3K VPS34 (IC50 > 9 µM), PI4-kinases (PIK4α IC50 > 10 µM; PIK4β IC50 = 5.2 µM), and PI3K-related protein kinase DNA-PK (IC50 > 10 µM), confirming its selectivity for class I PI3Ks [68]. Additionally, 47 demonstrated favourable oral exposure in mice, resulting in significant inhibition of PI3K/Akt signalling and antitumor efficacy in a U-87 MG xenograft model. Compound 47 demonstrated favorable oral exposure in mice, resulting in significant inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling and antitumor efficacy in a U-87 MG xenograft model [68]. In contrast, the hybrid class of N-(5-amino-2-chloropyridin-3-yl)sulfonamide inhibitors (48) showed only modest selectivity for PI3K over mTOR and limited selectivity against the class III PI3K hVps34 [69]. Nevertheless, 48 was effective in a U-87 tumor pharmacodynamic model, with a plasma EC50 of 0.193 µM [69]. Another derivative 49, potently inhibited the PI3K pathway in a mouse liver pharmacodynamic model, with an EC50 of 228 ng/mL, and demonstrated strong antitumor activity in a U-87MG glioblastoma xenograft model (ED50 = 0.6 mg/kg) [70]. Based on its favorable in vivo efficacy and pharmacokinetic profile, 49 was selected for further development as a clinical candidate (AMG 511) for cancer therapy [70].

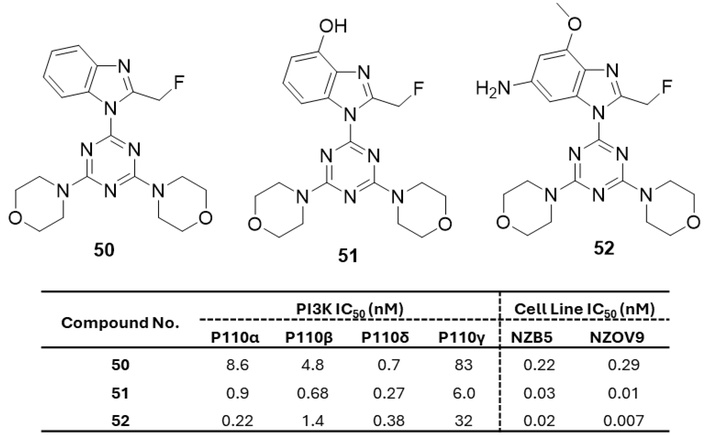

Compound 50 [2-(2-difluoromethylbenzimidazol-1-yl)-4,6-dimorpholino-s-triazine] (Figure 23) was the orally administered PI3K inhibitor with influential anticancer activity and no observed in vivo toxicity [71]. Treatment with 1 µM of 50 reduced PI3K activity to 4.7% of the untreated control. It acted as an ATP-competitive inhibitor across all four PI3K isoforms, showing the highest potency against PI3Kδ (IC50 = 4.6 nM) [72]. Compound 50 demonstrated in vivo antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts and has entered phase I clinical trials as ZSTK474 [73–75]. Introduction of substituents on the benzimidazole ring led to a series of analogues, among which compounds 51 and 52 (Figure 23) were the most potent [75]. While 51 exhibited poor pharmacokinetics, likely due to rapid glucuronidation, 52 achieved more favorable drug levels. In U-87MG human glioblastoma xenografts, 52 significantly reduced tumor growth at the MTD; however, its poor solubility limited tolerability in vivo [75].

s-Triazine derivatives (50–52), which are active against the tested strains as a potent inhibitor of PI3K. PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinases.

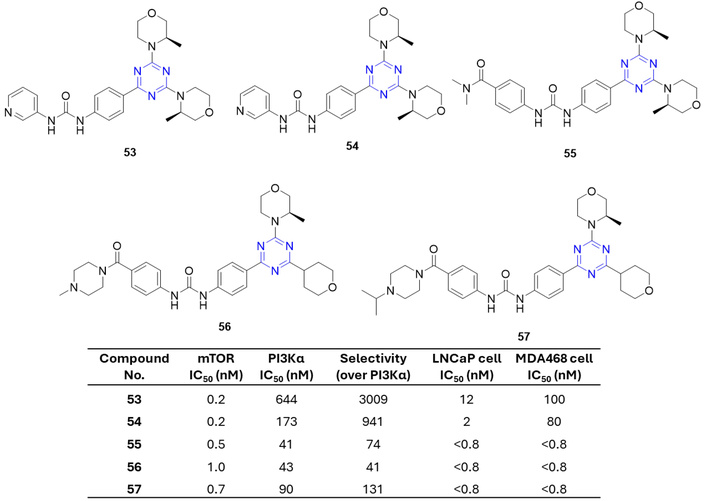

To develop effective mTOR inhibitors, a series of bis-(R)-3-methylmorpholine triazines bearing a ureidophenyl moiety (53–57) (Figure 24) were synthesized [76]. Compounds containing the (R)-3-methylmorpholine (53) and a pyridylureidophenyl group (54), compared to related lipid kinase PI3Kα, displayed the highest selectivity for mTOR. In contrast, introduction of amines at the 4-position of the ureidophenyl ring (55–57) reduced selectivity toward PI3Kα but enhanced antiproliferative activity against prostate LNCaP and breast MDA-MB-468 cancer cells, characterized by hyperactive PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling [76].

s-Triazine containing methyl-morpholine and ureido derivatives (53–57), which are active against the tested anticancer strains. mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinases.

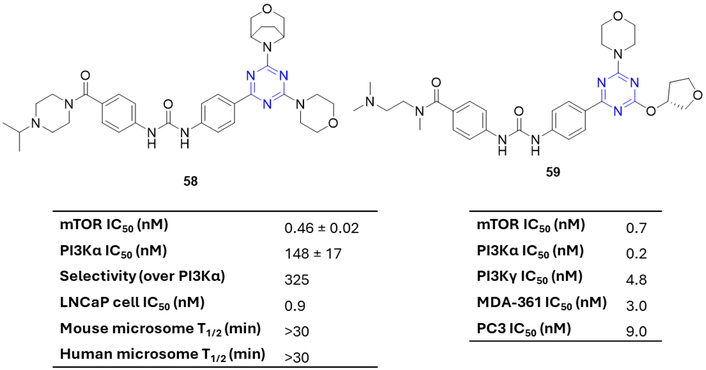

Verheijen et al. [77] reported a series of highly potent 2-arylureidophenyl-4-(3-oxa-8-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-8-yl)-s-triazines as selective ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors. Among these, 58 (Figure 25) exhibited a strong balance of mTOR inhibitory activity (IC50 = 0.46 nM), high selectivity over PI3Kα [IC50 (PI3Kα)/IC50 (mTOR) = 325], and favorable microsomal stability (T1/2 > 30 min), and also in the human glioblastoma xenograft model induced significant tumor growth arrest [77]. Subsequent efforts to optimize PKI-587 (gedatolisib) led to 59 (Figure 25), which combined potent PI3Kα inhibitory activity with improved biological and pharmacokinetic profiles [78, 79].

mTOR activity of 2-arylureidophenyl-4-(3-oxa-8-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-8-yl)-s-triazine derivatives (58 and 59), which are active against the tested strains. mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinases.

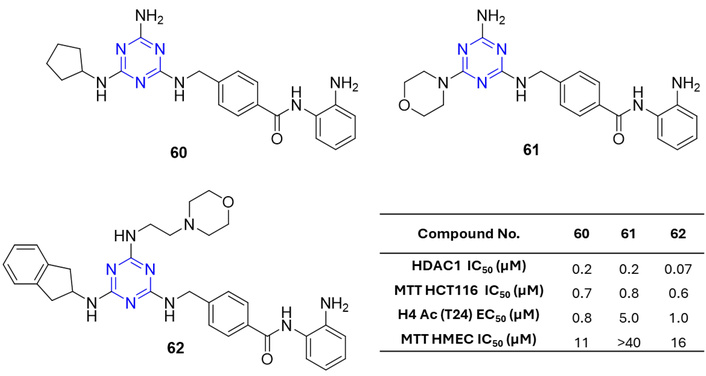

Paquin et al. [80] synthesized a series of 4-[(s-triazin-2-ylamino)-methyl]-N-(2-aminophenyl)-benzamides (60–62; Figure 26) that exhibited potent HDAC1 inhibitory activity, with IC50 values below 0.2 µM, and strong in vitro antiproliferative effects against the human colon cancer cell line HCT-116. Structure-activity analysis indicated that optimal HDAC1 inhibition was achieved with the presence of an indanyl-2-amino group and an amino/alkylamino substituent. Compounds 60–62 also demonstrated significant anticancer efficacy in HCT-116 xenograft models in mice.

4-[(s-triazin-2-ylamino)methyl]-N-(2-aminophenyl)-benzamides analogues (60–62), which are active against the tested anticancer strains.

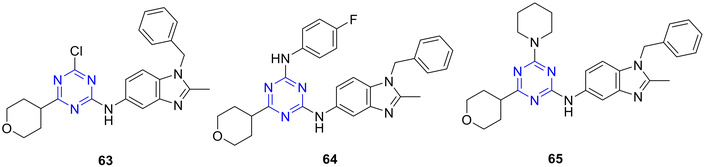

Various s-triazines bearing an aminobenzimidazole, morpholino group, and an amine at the 2-, 4-, and 6-position, respectively (Figure 27), were synthesized and evaluated for antiproliferative activity across the 60 cancer cell lines from the NCI panel [81]. Among these, compounds 63–65 (Figure 27) exhibited notable cytotoxicity, with MG-MID GI50 values of 9.79, 2.58, and 3.81 µM, respectively. Mechanistic studies revealed that 63 and 65 significantly inhibited DHFR (IC50 = 1.05 and 2.09 µM, respectively) and demonstrated strong DNA-binding capability [81].

s-Triazine-benzimidazole hybrids (63–65), which are active against the National Cancer Institute (NCI) panel of 60 cancer cell lines.

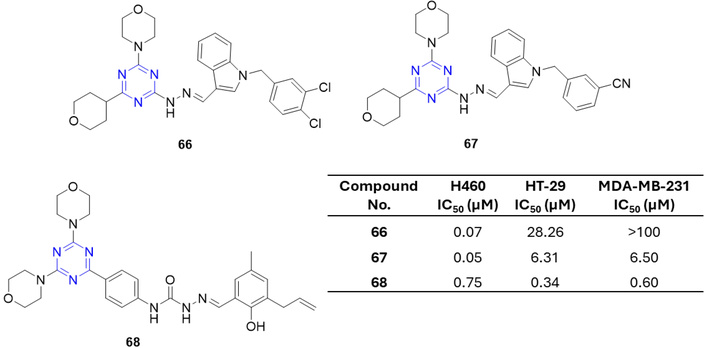

In the pursuit of new anticancer agents, two series of 2,4-bis-morpholino-s-triazine derivatives were synthesized and evaluated against human lung (H460, H1975), colon (HT-29), breast (MDA-MB-231), and glioblastoma (U87MG) cell lines [82]. Among these, hydrazinyl derivatives 66 and 67 exhibited potent activity against H460 cells, with IC50 values of 0.07 and 0.05 µM, respectively (Figure 28). Preliminary SAR analysis indicated that the 1-benzyl-1H-indol-3-yl-methylene moiety is critical for antiproliferative activity, and the size of substituents on the benzene ring strongly influenced potency, with smaller groups favoring higher activity [82]. Huang et al. [83] further evaluated a series of bis(morpholino-s-triazine) derivatives bearing an arylmethylene hydrazine moiety against H460, HT-29, and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Structure-activity analysis revealed that both the arylmethylene group and the N-phenylmethanamide linker were critical for anticancer activity. The most promising compound, derivative 68, exhibited IC50 values of 0.75, 0.34, and 0.60 µM against H460, HT-29, and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively. mTOR kinase assays confirmed that these compounds do not exert their effects via mTOR inhibition [82, 83].

Structure of s-triazine morpholino derivatives (66–68), which are active against the human lung, colon, breast, and glioblastoma cell lines.

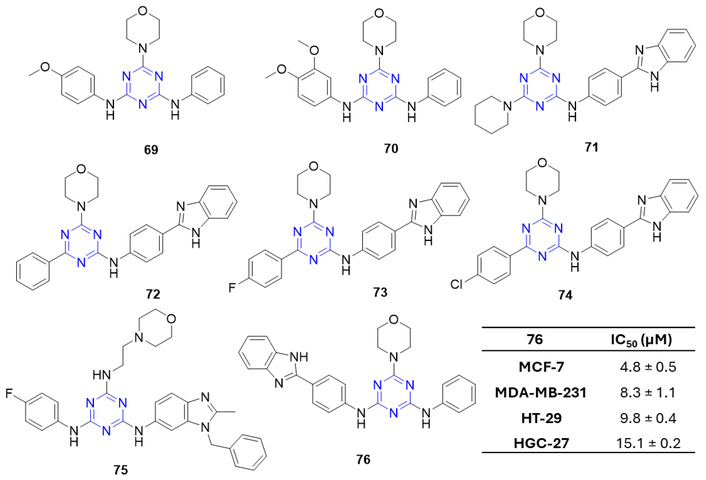

Zheng et al. [84] reported a new class of N-morpholino triamino-s-triazines, which demonstrated significant antiproliferative effects against HCT-116 and HT-29. Compounds 69 and 70 (Figure 29) showed IC50 values of 0.76 and 0.92 µM against HCT-116, respectively. Compound 69 was further assessed for pharmacokinetic and in vivo antitumor activity, demonstrating rapid oral absorption with 30.9% bioavailability and moderate antitumor efficacy in the Sarcoma 180 mouse model, achieving 40.7% tumor inhibition at 200 mg/kg/day [84]. In a separate study, additional N-morpholino 1,3,5-triazine derivatives were evaluated against 60 human cancer cell lines at 10 µM [85]. Among these, compounds 71–74 (Figure 29) were highly active against HL-60 and SR leukemia cell lines and the RXF393 renal cancer line in the nanomolar range. HL-60 (TB) cells were most sensitive to 71 (GI50 = 31 nM; TGI = 601 nM), while 71–74 inhibited SR leukemia cells with GI50 values of 731, 125, 539, and 31 nM, respectively. These compounds showed activity against RXF393 cells (GI50 = 808, 501, 459, and 222 nM, respectively) and demonstrated the ability to bind bovine serum albumin (BSA), facilitating targeted delivery [85]. Further, the same group identified a s-triazine derivative, 75 (Figure 29), bearing benzimidazole and morpholine groups, which exhibited potent DHFR inhibition (IC50 = 2 nM) [86]. DHFR inhibition by such derivatives depletes intracellular reduced folate, crucial for RNA, DNA, and protein synthesis [87]. Compound 75 also displayed strong ct-DNA intercalation, as shown by UV-visible and fluorescence spectroscopy, and exhibited broad-spectrum antitumor activity against leukemia, melanoma, CNS, colon, and breast cancers, with IC50 values ranging from 1.91 to 2.72 µM [86].

N-morpholino triamino-s-triazine derivatives (69–76), which are active against the tested anticancer strains.

Kumar et al. [88] reported the synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of two classes of s-triazine derivatives. Within these series, compounds bearing a benzimidazole moiety were significantly more potent than the corresponding benzothiazole analogs. Notably, the benzimidazole derivative bearing a morpholine group (76; Figure 29) exhibited the highest antiproliferative efficacy against cell lines MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, HT-29, and HGC-27 with IC50 values in the range 4.8 to 15.1 µM [88].

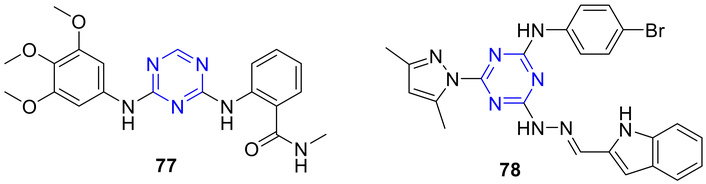

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a non-receptor tyrosine-protein kinase that is broadly distributed, highly conserved, and localized at focal adhesions. Its activation occurs when integrins interact with the extracellular matrix (ECM) or in response to growth factors like VEGF. FAK is essential for angiogenesis during development, as demonstrated by the early embryonic death observed in mice lacking FAK specifically in endothelial cells. Elevated expression or activity of FAK is frequently seen in many types of human cancers, making FAK a promising target for the development of new anti-cancer therapies [89, 90]. FAK is a key signaling protein in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), regulating cell adhesion, survival, migration, and angiogenesis. To develop FAK kinase inhibitors, a novel series of diarylamino-s-triazine derivatives was synthesized and evaluated for antiangiogenic activity in HUVECs [91]. FAK inhibitory potency was measured using a time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) assay [91, 92]. Among the derivatives, 77 (Figure 30) exhibited the highest FAK inhibitory activity (IC50 = 0.4 µM) and the strongest antiproliferative effect against HUVEC cells (IC50 = 2.5 µM). Furthermore, 77 significantly reduced FAK autophosphorylation in HUVECs, suggesting that these compounds inhibit cancer cell proliferation by targeting the FAK signaling pathway [91].

s-Triazine derivatives (77 and 78), which are active against the tested strains with high potency towards FAK kinase. FAK: focal adhesion kinase.

Hsp90 is a vital molecular chaperone required for the survival of eukaryotic cells. Working together with various cochaperones, Hsp90 utilizes its ATPase activity to assist in the proper folding, activation, and stabilization of numerous client proteins. Many of these clients are oncogenic proteins, such as tyrosine kinase receptors, signaling molecules, and transcription factors that play key roles in cancer initiation and progression. Because cancer cells heavily depend on Hsp90 to preserve the stability of their mutated or overexpressed oncoproteins, targeting Hsp90 has emerged as an attractive strategy for anticancer therapy [93]. Zhao et al. [94] further reported the antiproliferative activity of 4-(2-((1H-indol-3-yl)methylene)hydrazinyl)-N-(4-bromophenyl)-6-(3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)-s-triazin-2-amine (78; Figure 30) as a potent Hsp90 inhibitor. In vitro studies demonstrated that 78 (X66) inhibited the proliferation of SK-BR-3, BT-474, A549, K562, and HCT-116 cells with IC50 values of 8.9, 7.1, 7.5, 8.6, and 6.7 µM, respectively, inducing cell cycle arrest followed by apoptosis. In vivo, 78 suppressed tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner in a BT-474 xenograft model. Compound 78 does not trigger a heat shock response (HSR); rather, it counteracts the HSF-1 activator-induced HSR. This unique property suggests that 78 could be used in combination therapies and may help overcome resistance to Hsp90 inhibitors in clinical settings.

Finally, the clinical success of several s-triazine-based anticancer agents still poses significant challenges in optimizing their selectivity, overcoming drug resistance, and improving pharmacokinetic properties.

The development of s-triazine-based anticancer compounds presents several challenges that researchers must address to enhance their therapeutic potential. These challenges span various aspects of drug development, including chemical synthesis, biological activity, drug delivery, and mechanisms of action. Below is a detailed discussion of these challenges, supported by insights from relevant research papers.

One of the primary challenges in developing s-triazine-based anticancer compounds is optimizing their potency and selectivity. While s-triazines have shown promise as anticancer agents, their effectiveness can vary significantly depending on their structural modifications. For instance, the substitution pattern on the triazine ring plays a critical role in determining their anticancer activity. Researchers have found that certain substituents, such as o-hydroxyphenyl groups, can enhance the potency of these compounds, which exhibited IC50 values comparable to cisplatin [95]. However, achieving the optimal balance between potency and selectivity remains a challenge, as some derivatives may exhibit off-target effects or lack sufficient activity against specific cancer cell lines.

Another significant challenge is the effective delivery of s-triazine-based compounds to cancer cells. The anticancer potency of these compounds often depends on their ability to reach the target site in sufficient concentrations. To address this, researchers have explored the use of drug delivery systems, such as calcium citrate nanoparticles (CaCit NPs), which can encapsulate triazine derivatives and release them in a controlled manner under acidic conditions, mimicking the cancer microenvironment [95, 96]. Despite these advancements, optimizing the drug delivery system to ensure high bioavailability and minimal systemic toxicity remains a critical challenge.

Understanding the precise mechanism of action of s-triazine derivatives is essential for overcoming drug resistance, a major hurdle in cancer therapy. These compounds often target specific molecular pathways, such as the EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling cascades [52]. However, cancer cells can develop resistance to these agents through various mechanisms, such as mutations in target proteins or alterations in signaling pathways. Overcoming resistance requires the design of compounds that can modulate multiple targets or act on alternative pathways, as well as a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying resistance.

Although the synthesis of the simpler s-triazine derivatives could be affordable, the synthesis of more complex derivatives, particularly when introducing specific substituents or hybridizing the triazine core with other pharmacophores, could be a challenge. For example, the synthesis of chalcone-tethered triazine hybrids involves multiple steps, including Claisen-Schmidt condensation and cyclocondensation reactions [97]. Additionally, the use of green chemistry approaches, such as microwave-assisted synthesis, has been explored to simplify the process and reduce environmental impact [98]. Despite these efforts, the synthetic complexity of certain derivatives should be solved, particularly when scaling up production for clinical applications.

Ensuring safety and reducing the toxicity of s-triazine-based compounds is another critical challenge. While these compounds have shown promising anticancer activity, some derivatives may exhibit cytotoxic effects on normal cells, limiting their therapeutic window. For instance, certain triazine derivatives have been evaluated for phototoxicity, which could pose safety risks in clinical settings [98]. Addressing these concerns requires careful optimization of the chemical structure to minimize off-target effects and improve the therapeutic index.

Establishing clear SAR is crucial for the rational design of s-triazine-based anticancer agents. The biological activity of these compounds is highly dependent on the nature and position of substituents on the triazine ring. For example, the introduction of oligopeptide moieties has been shown to enhance the cytotoxicity of triazine derivatives, which induced apoptosis in colon cancer cell lines [99]. However, the complexity of these relationships often requires extensive SAR studies, which can be resource-intensive and time-consuming.

While many s-triazine-based compounds have shown promising activity in vitro, translating this efficacy to in vivo models and clinical settings remains a significant challenge. Factors such as pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and systemic toxicity must be carefully evaluated to ensure that these compounds are suitable for clinical use. For example, the approved s-triazine derivative gedatolisib has demonstrated clinical efficacy in treating metastatic breast cancer, but its development required extensive pre-clinical and clinical studies [18, 20]. Accelerating the clinical translation of promising s-triazine-based compounds is essential to bring these agents to patients in need.

The development of s-triazine-based anticancer compounds also faces challenges related to intellectual property and regulatory approval. Securing patents for novel derivatives can be competitive, as the field is highly active, with multiple research groups exploring similar chemical spaces. Additionally, navigating the regulatory landscape to ensure compliance with safety and efficacy standards can be a lengthy and costly process. These hurdles highlight the need for collaborative efforts between academia and industry to advance the development of these compounds.

While some derivatives, such as those synthesized from commercially available starting materials like TCT, may be cost-effective, others may require specialized reagents or complex synthesis procedures, increasing production costs. Scaling up the synthesis of these compounds while maintaining high purity and yield is essential for their widespread adoption as anticancer agents.

The extensive collection of chemically diverse s-triazine-based heterocyclic hybrid molecules highlighted in this review underscores their substantial promise as next-generation therapeutic agents. Many of these hybrids have demonstrated superior in vitro anticancer activity compared to currently used drugs, indicating their strong potential for further advancement into preclinical and clinical stages. The tunable electronic and steric properties of the s-triazine core allow for fine structural optimization, and the incorporation of different substituents or bioactive pharmacophores has shown a remarkable influence on both potency and target selectivity. These observations emphasize s-triazine as a highly privileged scaffold in medicinal chemistry.

Given its structural versatility and presence in several approved drugs, s-triazine can be considered an ideal central nucleus/moiety for rational drug design. In particular, the development of multitarget-directed ligands (MTDLs) can be engineered to simultaneously modulate multiple disease-relevant pathways. MTDLs represent a growing and transformative strategy in tackling complex diseases such as cancer, neurodegeneration, and microbial infections. Hybrid molecules that combine s-triazine with other pharmacologically relevant heterocycles embody this concept excellently, offering opportunities to enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects and drug resistance.

Looking ahead, future research on hybrid s-triazine derivatives should focus on gaining a deeper understanding of their molecular mechanisms and validated biological targets to enable more precise and rational design strategies. Concurrently, optimization of selectivity, pharmacokinetic behavior, and safety profiles through systematic SAR and computational modeling will be crucial to minimizing off-target effects while maintaining potency. In the context of anticancer activity, developing multitarget-directed s-triazine hybrids offers an attractive avenue to combat drug resistance and tumor heterogeneity, challenges that often limit the effectiveness of single-target agents. Moreover, advancing these promising molecules from in vitro studies to in vivo pharmacological and toxicity evaluations will be essential for identifying true lead compounds with strong translational potential, ultimately paving the way for their clinical development.

In conclusion, s-triazine-based heterocyclic hybrids are poised to play a pivotal role in the discovery of safe, effective, and multitargeted therapeutics. With continued innovation in chemical design and biological evaluation, this scaffold holds the potential to contribute significantly to the development of breakthrough drugs for complex and challenging diseases.

4 Å MS: 4 Å molecular sieves

AML: acute myeloid leukemia

CDKs: cyclin-dependent kinases

DCM: dichloromethane

d-MCTs: disubstituted monochloro s-triazines

DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide

EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor

FAK: focal adhesion kinase

HSP90: heat shock protein 90

HSR: heat shock response

HUVECs: human umbilical vein endothelial cells

m-DCTs: monosubstituted dichloro s-triazines

MTDLs: multitarget-directed ligands

mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin

NCI: National Cancer Institute

PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinases

SAR: structure-activity relationship

TCT: 2,4,6-trichloro-1,3,5-triazine

TFA: trifluoroacetic acid

VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor

The author Ihab Shawish would like to acknowledge Prince Sultan University for the support.

AEF, FA, and BGT: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. IS and AK: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Fernando Albericio, who is the Editor-in-Chief and Guest Editor of Exploration of Drug Science; Beatriz G. de la Torre, who is the Associate Editor of Exploration of Drug Science; Ayman El-Faham, who is the Associate Editor and Guest Editor of Exploration of Drug Science, had no involvement in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 662

Download: 42

Times Cited: 0