Affiliation:

1Ningyang Institute, Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital, Xining 810001, Qinghai, China

†These authors share the first authorship.

Affiliation:

2Breast Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Center, Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital & Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Qinghai University, Xining 810001, Qinghai, China

†These authors share the first authorship.

Affiliation:

1Ningyang Institute, Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital, Xining 810001, Qinghai, China

Affiliation:

1Ningyang Institute, Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital, Xining 810001, Qinghai, China

Affiliation:

2Breast Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Center, Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital & Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Qinghai University, Xining 810001, Qinghai, China

Affiliation:

2Breast Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Center, Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital & Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Qinghai University, Xining 810001, Qinghai, China

Affiliation:

3Oncology Ward 1, Qinghai Red Cross Hospital, Xining 810000, Qinghai, China

Email: zhongguo7002@126.com

Affiliation:

2Breast Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Center, Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital & Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Qinghai University, Xining 810001, Qinghai, China

Email: jiudazhao@126.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1266-8943

Explor Drug Sci. 2026;4:1008148 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2026.1008148

Received: October 31, 2025 Accepted: December 29, 2025 Published: February 02, 2026

Academic Editor: Ayman El-Faham, Dar Al Uloom University, Saudi Arabia, Alexandria University, Egypt

Aim: To evaluate the real-world effectiveness of prophylactic metoclopramide in preventing opioid-induced nausea and vomiting (OINV) during the initial phase of strong opioid therapy in opioid-naïve patients with cancer-related pain.

Methods: This retrospective, single-center observational cohort study included adult patients with pathologically confirmed malignancies who initiated strong opioid therapy between January 2023 and December 2024. Patients were categorized into a prophylactic metoclopramide group or a no-prophylaxis control group. Complete control (CC) of OINV during the first 7 days was defined as the absence of nausea, vomiting, and rescue antiemetic use. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors associated with CC, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, cancer subtype, cancer stage, comorbidity status, and morphine-equivalent daily dose (MEDD). Subgroup analyses were conducted based on age, sex, and cancer subtype.

Results: A total of 244 patients were included, of whom 199 received prophylactic metoclopramide, and 45 received no prophylaxis. The prophylactic group achieved significantly higher CC rates than the control group (74.9% vs. 37.8%, p < 0.001). Multivariate logistic regression confirmed that prophylactic metoclopramide was independently associated with higher odds of achieving CC (adjusted OR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.10–0.40; p < 0.001). Similar improvements were observed for nausea and vomiting control. Subgroup analyses demonstrated consistent benefits across age and sex groups, with particularly notable effects in patients with gastrointestinal cancers.

Conclusions: Prophylactic metoclopramide significantly improves OINV control in opioid-naïve patients with cancer-related pain during the initiation of strong opioids. These findings support the rational use of early antiemetic prophylaxis in routine clinical practice. Prospective randomized trials are warranted to validate these real-world results and assess long-term safety.

Pain is highly prevalent among patients with advanced malignancies, and a substantial proportion experience moderate to severe pain with significant impact on daily life, particularly among those with pancreatic, head and neck, genitourinary, gastrointestinal, breast, and uterine cancers [1–4]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder, opioids remain the cornerstone of cancer pain management [1].

Despite their analgesic efficacy, opioids frequently cause adverse effects, among which opioid-induced nausea and vomiting (OINV) is one of the most common and distressing [1, 5, 6]. During morphine therapy, nausea occurs in 40% of patients, and vomiting in 15–25% [7]. OINV typically emerges early in treatment and may lead to therapy discontinuation, reduced adherence, and complications such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and malnutrition [1, 5, 6]. Prevention is thus vital for maintaining patient quality of life and treatment outcomes [8].

While antiemetics are sometimes used prophylactically in clinical practice [5], strong evidence supporting their routine use for OINV prevention in patients with cancer remains lacking. To date, only two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have specifically evaluated this strategy in patients with cancer-related pain initiating strong opioid therapy [9, 10]. In one study involving patients starting oral oxycodone, prochlorperazine failed to outperform placebo and was associated with increased sedation [10]. Another RCT compared metoclopramide with haloperidol in patients newly treated with oral morphine. Although metoclopramide was more effective in preventing vomiting, both agents had similar effects on nausea. However, small sample sizes and limited generalizability underscore the need for further real-world research in opioid-naïve patients with cancer [9].

Currently, no major clinical guidelines recommend the routine prophylactic use of antiemetics for OINV. Nonetheless, some clinicians empirically administer metoclopramide for prevention, though findings remain inconsistent. A meta-analysis in acute care settings found that prophylactic metoclopramide did not significantly reduce nausea and vomiting incidence, although it slightly alleviated nausea severity [11]. In contrast, another randomized trial in trauma patients receiving tramadol showed significant benefits from prophylactic metoclopramide. These discrepancies highlight the need for real-world evidence specific to oncology populations to clarify its preventive value [12].

Pathophysiologically, OINV results from multiple mechanisms, including stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), delayed gastric emptying, and vestibular hypersensitivity, with dopamine D2 receptor activation playing a central role [1, 7, 13]. Hence, metoclopramide, which has both dopamine D2 receptor antagonism and prokinetic effects, is considered a rational candidate for the prevention of OINV.

The present study was designed as a retrospective, single-center cohort analysis to assess the real-world effectiveness of prophylactic metoclopramide in preventing OINV in patients with cancer-related pain who were initiating strong opioid therapy for the first time.

This retrospective, single-center observational cohort study was conducted at Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital (China) to evaluate the real-world effectiveness of prophylactic metoclopramide in reducing the incidence of OINV among patients with cancer-related pain. This was an observational study without randomization. The unequal group sizes (199 vs. 45) reflect real-world prescribing patterns: during the study period, prophylactic metoclopramide gradually became common practice in our department, resulting in more patients receiving metoclopramide at opioid initiation. Patient data were extracted from electronic medical records between January 2023 and December 2024. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital (Approval No. AF-RHEC-0018-01) under institutional protocol 2018-SF-113. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and anonymized data handling.

Inclusion criteria: ability to take oral medications; patients aged ≥ 18 years with pathologically confirmed malignancies who initiated strong opioid therapy (morphine, oxycodone, or fentanyl) for cancer-related pain for the first time at our institution; moderate to severe baseline pain (Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) ≥ 4); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0–3; and absence of nausea, vomiting, bowel obstruction, or gastrointestinal bleeding at baseline.

Exclusion criteria: patients who had started strong opioid therapy before the observation period or at another hospital, and those with impaired oral intake.

Patients were categorized into two groups based on whether they received prophylactic metoclopramide. The prophylactic group received metoclopramide 10 mg orally three times daily for 7 consecutive days, starting 30 minutes before the first opioid dose. The control group did not receive any prophylactic antiemetics unless clinically indicated. In both groups, strong opioids were initiated according to standard practice, and the morphine-equivalent daily dose (MEDD) was consistent with those reported in prior retrospective studies evaluating OINV prophylaxis (15 mg/day) [14].

In our clinical practice, metoclopramide was the only prophylactic antiemetic used during the study period. No other antiemetic agents (such as ondansetron, tropisetron, granisetron, dexamethasone, or olanzapine) were used as routine prophylaxis at opioid initiation. Rescue antiemetics were not routinely prescribed and, when used, were documented as part of the outcome definition rather than as baseline covariates. Because detailed information on all other concomitant medications was not consistently available from the electronic medical record, such medications could not be incorporated into the multivariable models.

The primary outcome was the complete control (CC) rate during the first seven days following the initiation of strong opioid therapy, defined as the simultaneous absence of nausea, vomiting, and the need for rescue antiemetic medications. Secondary outcomes included the nausea control rate (no reported nausea) and the vomiting control rate (no reported vomiting). All outcomes were recorded as binary variables.

Clinical data, including demographic characteristics, cancer diagnosis, opioid regimens, and antiemetic use, were extracted from electronic medical records. Nausea and vomiting were documented by clinical staff during routine inpatient monitoring and assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Pain intensity was recorded using the NRS.

Additional variables included in regression analyses—such as body mass index (BMI), cancer subtype (gastrointestinal vs. non-gastrointestinal), cancer stage, and the presence of underlying comorbidities—were obtained from structured admission records and clinical documentation.

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the independent-samples t-test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Univariate logistic regression was first performed to examine the association between each baseline variable and study outcomes. Subsequently, multivariate logistic regression was used to identify factors independently associated with the primary and secondary outcomes, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, cancer subtype, cancer stage, and comorbidities. MEDD was also included as a covariate to assess its potential association with OINV. Comorbidity status, recorded in the dataset as “underlying diseases” (0 = no underlying disease, 1 = presence of ≥ 1 chronic condition), was included as an independent variable in both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on age, sex, and cancer subtype to explore the consistency of treatment effects across patient subgroups. Results from logistic regression models were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to quantify the strength of association between prophylactic metoclopramide and outcome measures. Bar charts were used to display outcome proportions across groups, while forest plots were employed to visually summarize the effect sizes (ORs and 95% CIs) from logistic regression analyses, including subgroup comparisons.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.2.2), and a two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 244 patients with pathologically confirmed malignancies who initiated strong opioid therapy were included in the analysis. Among them, 199 patients received prophylactic metoclopramide, while 45 received no prophylactic antiemetic treatment. The study flowchart is shown in Figure 1. Baseline characteristics were comparable between the two groups in terms of age, sex, BMI, cancer type, cancer stage, and MEDD. Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without prophylactic metoclopramide use.

| Characteristic | Without metoclopramide(n = 45) | With metoclopramide(n = 199) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 70.91 ± 9.80 | 69.99 ± 9.30 | 0.120 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 20.08 ± 2.20 | 19.98 ± 1.69 | 0.140 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 21.0 (46.7) | 85.0 (42.7) | 0.800 |

| Male | 24.0 (53.3) | 114.0 (57.3) | |

| Cancer subtype, n (%) | |||

| Respiratory system | 9.0 (20.0) | 30.0 (15.1) | 0.055 |

| Digestive system | 17.0 (37.8) | 119.0 (59.8) | |

| Urogenital system | 12.0 (26.7) | 33.0 (16.6) | |

| Others | 7.0 (15.6) | 17.0 (8.5) | |

| Stage, n (%) | |||

| I–III | 13.0 (28.9) | 40.0 (20.1) | 0.300 |

| IV | 32.0 (71.1) | 159.0 (79.9) | |

| Underlying diseases, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 13.0 (28.9) | 81.0 (40.7) | 0.200 |

| 1 | 32.0 (71.1) | 118.0 (59.3) | |

| Past history, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 10.0 (22.2) | 69.0 (34.7) | 0.200 |

| 1 | 35.0 (77.8) | 130.0 (65.3) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD. BMI: body mass index (measured in kilograms per square meter (kg/m²)); 0: no underlying disease; 1: presence of ≥ 1 chronic condition.

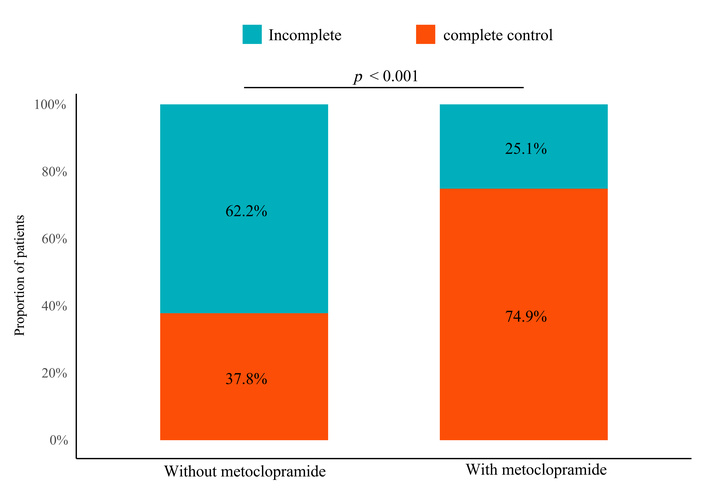

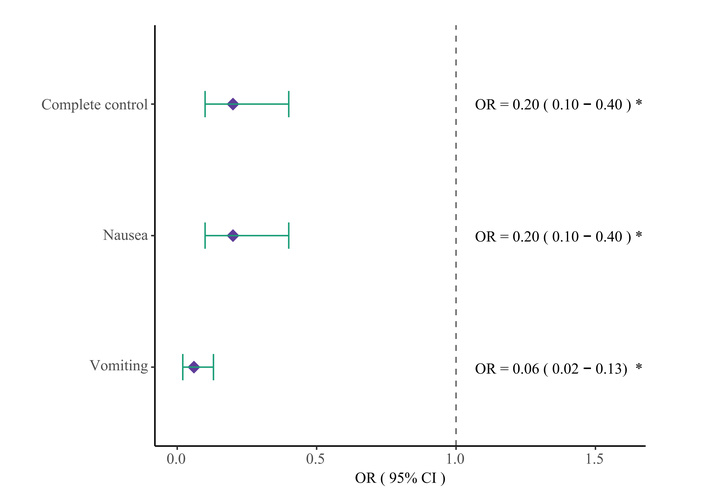

The CC rate during the first seven days was significantly higher in the metoclopramide group (74.9%) than in the control group (37.8%) (p < 0.001), as shown in Figure 2. Although no significant baseline differences were observed in Table 1, multivariate logistic regression was performed to minimize residual confounding. After adjusting for age, sex, BMI, cancer subtype, cancer stage, comorbidity status, and MEDD, prophylactic metoclopramide remained strongly and independently associated with a higher likelihood of achieving CC (adjusted OR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.10–0.40; p < 0.001) (Figure 3). MEDD was not significantly associated with CC after adjustment. Consistent results were observed in univariate analysis, where metoclopramide remained the only variable significantly associated with CC (Figure S1).

Distribution of complete control (CC) outcomes with and without prophylactic metoclopramide.

Forest plot of multivariate analysis for primary and secondary endpoints. OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; *: indicates statistical significance with p < 0.05.

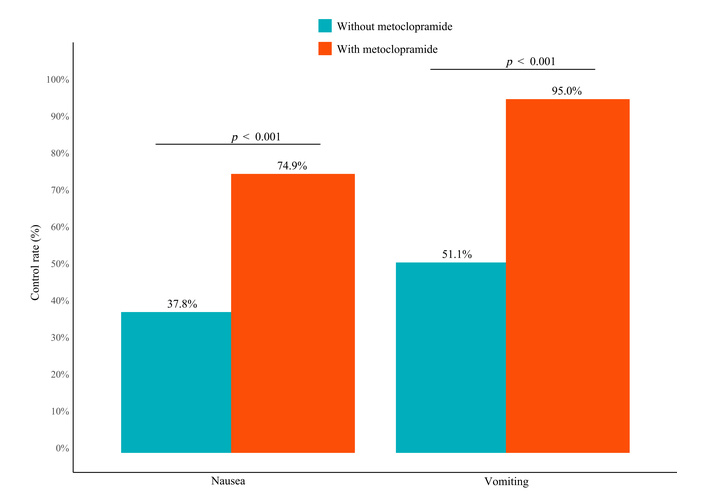

Nausea control was achieved in 74.9% of patients receiving prophylactic metoclopramide, compared to 37.8% in the control group (OR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.10–0.40; p < 0.001). Vomiting control was observed in 95.0% vs. 51.1%, respectively (OR = 0.06, 95% CI: 0.02–0.13; p < 0.001). These differences are visualized in Figure 4. Multivariate logistic models confirmed the associations, and univariate analyses yielded consistent findings (Figures S2 and S3).

Comparison of nausea and vomiting control rates between patients with and without metoclopramide prophylaxis.

Subgroup analyses demonstrated consistent benefits of prophylactic metoclopramide across age, sex, and cancer type strata. The stratified CC rates are shown in Figure 5. In patients aged < 70 years, the CC rate was 92.9% with prophylaxis versus 41.2% without. In those ≥ 70 years, it was 97.7% vs. 57.1%, respectively (p < 0.001). Among male patients, the CC rate was 94.7% vs. 45.8%, and in female patients, 95.3% vs. 57.1% (p < 0.001 for both). In patients with gastrointestinal cancers, the CC rate was 95.0% vs. 11.8% (p < 0.001), whereas no significant difference was seen in non-gastrointestinal cancers.

Stratified results for nausea and vomiting control also supported the robustness of the prophylactic effect. In Figure S4, nausea control rates were significantly higher across all subgroups in the metoclopramide group. Similarly, Figure S5 shows that vomiting control rates were substantially improved with prophylaxis across the same subgroups.

This retrospective cohort study represents one of the largest real-world investigations to date evaluating prophylactic metoclopramide for the prevention of OINV in opioid-naïve patients with cancer-related pain [9]. Our findings indicate that the use of prophylactic metoclopramide during the first week of strong opioid initiation was associated with significantly higher rates of CC, as well as improved control of both nausea and vomiting, compared to no prophylaxis. These results contribute meaningful real-world evidence in support of early antiemetic intervention during the initial phase of opioid therapy.

Compared with previous studies, our findings add important clarity to the ongoing debate surrounding the effectiveness of metoclopramide in preventing OINV. A RCT by Singhal et al. [9] compared prophylactic metoclopramide to haloperidol in patients receiving morphine and found a reduction in vomiting, though nausea control remained similar across arms. In contrast, a recent meta-analysis conducted in acute care settings concluded that prophylactic metoclopramide had minimal impact on nausea and vomiting incidence [11]. Conversely, a randomized trial by Choo et al. [12], conducted in trauma patients receiving intravenous tramadol, reported significant reductions in both symptoms. However, all three studies were limited by either a small sample size, a short follow-up period, or the inclusion of non-cancer populations. In contrast, our study focuses specifically on patients with malignancies and opioid-naïve status, a group for whom prophylactic strategies may have the greatest clinical relevance. The inclusion of a well-balanced control group and standardized opioid dosing further enhances the robustness of our findings.

Recent attention in the field has predominantly focused on treating established OINV, while prophylactic strategies remain underexplored [15]. Although antiemetics such as metoclopramide are commonly used in practice, their prophylactic use is not currently supported by high-level evidence, and no major international guidelines recommend their routine use in opioid-naïve patients without a prior history of OINV [16]. Notably, two RCTs in cancer pain populations—the only such studies to date—offered limited and somewhat inconsistent findings. In this context, our results fill an important gap by providing retrospective, real-world data suggesting that early intervention with metoclopramide may meaningfully improve symptom control and reduce the need for rescue medications.

Multivariate logistic regression confirmed that prophylactic metoclopramide use was independently associated with improved OINV control. After adjusting for potential confounders, including age, sex, cancer type, baseline performance status, and MEDD, the association remained statistically significant. None of the other baseline covariates demonstrated a significant relationship with the primary or secondary outcomes. This suggests that the observed benefit was not merely due to favorable patient characteristics but likely attributable to the pharmacologic effect of metoclopramide. These findings strengthen the internal validity of our results and highlight the robustness of the antiemetic benefit across diverse clinical contexts.

Subgroup analysis confirmed that the benefit of prophylactic metoclopramide was consistent across age and sex strata. Notably, in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies, the improvement in vomiting control was particularly pronounced. This may be attributed to metoclopramide’s dual mechanism of action—as a central dopamine D2 receptor antagonist and a peripheral prokinetic agent—which could offer enhanced benefit in patients with tumor-related gastrointestinal dysmotility or delayed gastric emptying [17, 18]. As this was a single-center study, generalizability may be limited. Future research involving multiple institutions and more diverse populations is needed to validate our findings.

Compared with other antiemetics, metoclopramide offers practical advantages for OINV prevention [19, 20]. Serotonin-receptor antagonists, such as ondansetron, are highly effective for chemotherapy-induced nausea [19], but have limited evidence supporting their prophylactic use in opioid-related settings [21, 22], and may exacerbate opioid-related constipation. Phenothiazines and butyrophenones may reduce nausea and vomiting but are associated with higher rates of sedation and extrapyramidal symptoms [23]. Metoclopramide combines dopamine D2-receptor antagonism with prokinetic activity, which may be particularly advantageous in patients with impaired gastric emptying or gastrointestinal malignancies [24–26]. Nevertheless, head-to-head comparative trials are lacking, underscoring the need for future research [14, 21]. To facilitate rapid clinical interpretation, key head-to-head evidence is summarized below. Available evidence remains limited and heterogeneous. In a RCT comparing metoclopramide with haloperidol (n = 90), metoclopramide was associated with a lower incidence of vomiting, while nausea control was similar between groups [9]. In contrast, placebo-controlled evidence in cancer pain populations has mainly evaluated other prophylactic antiemetics rather than metoclopramide; for example, the prophylaxis for oxycodone-induced nausea and vomiting trial (POINT) compared prophylactic prochlorperazine with placebo during oxycodone initiation (n = 120) [10]. In a randomized trial conducted in non-cancer opioid-related settings (n = 191), prophylactic metoclopramide significantly reduced both nausea and vomiting in trauma patients receiving intravenous tramadol [12]. Meta-analytic evidence from acute care and emergency settings (5 trials, > 527 patients) suggests an uncertain prophylactic benefit for OINV, with substantial heterogeneity across studies [11].

It is also important to note that our study focused on the first 7 days of opioid initiation, a period during which OINV is most likely to occur [27, 28]. Whether prophylactic metoclopramide provides sustained benefits beyond the acute phase remains unclear [29]. Long-term observational data suggest that nausea can persist during chronic opioid therapy in a subset of patients, highlighting the uncertainty regarding longer-term prophylactic benefit [30]. Future prospective studies with longer follow-up are needed to evaluate ongoing symptom control, opioid adherence, and potential late-onset gastrointestinal or neurologic adverse effects [31].

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective nature of the study precludes causal inference and may introduce unmeasured confounding. Second, although baseline characteristics were generally balanced between groups, the non-random allocation may have introduced selection bias. Although multivariate regression was applied to reduce confounding, residual bias may persist due to unmeasured factors such as physician preference, anticipated OINV risk, and subtle clinical characteristics not captured in the medical record. For example, physicians may have preferentially prescribed prophylactic metoclopramide to patients perceived to be at higher risk of OINV, a factor not fully captured in the electronic medical records, which could have biased the observed effect estimates toward the null direction. Third, data on adverse effects such as sedation, extrapyramidal symptoms, or fatigue were not systematically recorded, and their incidence remains unclear. In addition, detailed information on specific opioid types was incomplete in the electronic medical records and, therefore, could not be included in the analysis. Lastly, this was a single-center study, and findings may not be generalizable to other settings with differing patient populations or practice patterns. Taken together, these limitations highlight the potential impact of confounding by indication and residual group imbalance inherent to observational designs, and caution against overinterpretation of the observed associations as causal effects.

From a clinical perspective, our findings support the proactive use of metoclopramide during the initiation of strong opioids, particularly in settings where OINV prevention is not routinely implemented. By reducing early nausea and vomiting, prophylactic treatment may improve opioid adherence, patient comfort, and overall pain management outcomes [27]. Clinically, based on the observed absolute increase of 37% in CC in our cohort, this corresponds to an approximate number needed to treat (NNT) of 3 to achieve one additional case of CC during the first week of opioid initiation. As current guidelines offer limited recommendations regarding routine prophylactic antiemetic therapy in opioid-naïve patients [32], our real-world data contribute meaningful evidence that may help inform future guideline development and institutional protocols.

In conclusion, prophylactic metoclopramide significantly improves OINV control in opioid-naïve patients with cancer-related pain. The consistent benefits observed across patient subgroups support its rational clinical use during opioid initiation. Prospective randomized studies are needed to confirm these findings, assess long-term safety, and inform guideline-based prophylactic strategies.

BMI: body mass index

CC: complete control

CI: confidence interval

MEDD: morphine-equivalent daily dose

NRS: Numerical Rating Scale

OINV: opioid-induced nausea and vomiting

OR: odds ratio

RCTs: randomized controlled trials

The supplementary figures for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1008148_sup_1.pdf.

The supplementary materials for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1008148_sup_2.pdf.

The authors would like to thank the clinical staff at the Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital for their support in data collection.

XM: Methodology, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Resources. YY: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. LS: Formal analysis, Visualization. LZ: Investigation, Data curation. DR: Visualization. YL: Investigation. ZL: Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Resources. JZ: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital (Approval No. AF-RHEC-0018-01). The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of anonymized data.

Not applicable.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

This study was supported by the Kunlun Talent and Plateau Famous Doctor Project of Qinghai Province. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 489

Download: 17

Times Cited: 0