Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Lusaka Apex Medical University, Lusaka 31909, Zambia

2School of Medicine, Mulungushi University, Livingstone 80415, Zambia

Email: csilumbwe72@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9071-4212

Affiliation:

3Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, Jiangsu, China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-9572-3810

Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Lusaka Apex Medical University, Lusaka 31909, Zambia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6235-1194

Affiliation:

1Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Lusaka Apex Medical University, Lusaka 31909, Zambia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-4790-1156

Affiliation:

2School of Medicine, Mulungushi University, Livingstone 80415, Zambia

4Emergency Medicine Department, Livingstone General Hospital, Livingstone 20100, Zambia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-4810-7352

Affiliation:

5Department of Surgery, University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka 51337, Zambia

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3035-2053

Explor Drug Sci. 2026;4:1008143 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eds.2026.1008143

Received: October 03, 2025 Accepted: December 23, 2025 Published: January 14, 2026

Academic Editor: Fernando Albericio, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, Universidad de Barcelona, Spain

Background: Vascular aging is a major driver of cardiovascular, metabolic, and degenerative diseases, characterized by oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, endothelial senescence, and impaired proteostasis. Emerging data show that anti-infective drugs can influence these aging pathways beyond antimicrobial activity. However, their capacity to accelerate or slow vascular ageing has not been clearly defined. This review summarizes current evidence on how anti-infective agents modulate vascular ageing mechanisms.

Methods: A systematic review was conducted following PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Studies from 2000 to 2024 were searched in major indexed databases. Eligible studies included in vitro, animal, and human research evaluating the effects of anti-infective agents on endothelial function, vascular senescence markers (p16INK4a, p21, SA-β-gal), oxidative stress, mitochondrial activity, inflammation, or proteostasis, key determinants of vascular ageing. Studies lacking mechanistic aging endpoints were excluded. Extracted data included drug class, model type, study design, and age-related outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed using SYRCLE, RoB-2, ROBINS-I, and narrative appraisal for in vitro studies.

Results: Ninety-eight studies were identified; after removing six duplicates, ninety-two met the criteria. Macrolides, tetracyclines, and selected antivirals exerted anti-ageing effects by suppressing senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), preserving mitochondrial integrity, reducing oxidative stress, and enhancing autophagy. Aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones accelerated vascular ageing by generating reactive oxygen species, inducing DNA damage, and disrupting proteostasis. Antiviral protease inhibitors worsened endothelial dysfunction and metabolic aging. Antifungals such as itraconazole and amphotericin B impaired mitochondrial activity and angiogenesis, contributing to ageing phenotypes. Antiparasitic drugs showed mixed aging outcomes: chloroquine promoted autophagy and longevity, whereas thiabendazole impaired vascular stability. Broad-spectrum antibiotics disrupted the gut-vascular axis, increasing trimethylamine N-oxide, a mediator of inflammatory vascular aging.

Discussion: Anti-infective drugs display diverse, class-specific effects on vascular aging. Recognizing these age-related actions is essential for safer prescribing and for repurposing anti-infective agents to target pathological vascular aging mechanisms.

Ageing is the major risk factor for many chronic and fatal human diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, various cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which are collectively known as age-related diseases [1]. By definition, vascular aging is the gradual structural and functional decline of blood vessels that manifests with age. This phenomenon serves as a critical determinant of various chronic degenerative diseases, ranging from neurological to cardiovascular impairment, which contribute to elevated global mortality rates. In contrast to chronological ageing, vascular ageing exerts distinct effects on endothelial integrity, arterial compliance, microcirculatory function, and the responsiveness of blood vessels to metabolic and physiological stimuli [2–4].

Central to vascular aging is endothelial dysfunction, characterized by diminished nitric oxide (NO), increased oxidative stress, and increased inflammatory signaling. These alterations culminate in impaired vasodilation, increased arterial stiffness, and increased susceptibility to atherogenesis, thrombosis, and ischemic injury [5].

Cellular senescence, defined as a state of irreversible cell-cycle arrest, is widely recognized as a fundamental hallmark of aging [2, 6]. While senescence plays essential physiological roles in embryonic development, tissue repair, and tumor suppression, its persistent accumulation becomes detrimental to human health and contributes to the progression of cancer and multiple age-related diseases [7]. In the vascular system, senescent endothelial cells (ECs) and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) progressively accumulate within the arterial wall during ageing and in response to cardiovascular stressors, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and oxidative injury [8].

These senescent cells (SCs) not only lose their ability to maintain vascular homeostasis but also secrete a complex pro-inflammatory mixture called the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which amplifies local inflammation, impairs tissue remodeling, and promotes disease progression [9, 10]. In addition, SCs are potent sources of low-grade chronic inflammation, often referred to as the “senescence-associated secretory phenotype” (SASP). Through SASP, they secrete: cytokines: interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-1β, TNF-α; chemokines: CCL2, CXCL8; matrix metalloproteinases (MMP): MMP-1, MMP-9; growth factors: VEGF, TGF-β. These factors recruit immune cells, promote tissue remodeling, and induce paracrine senescence in neighboring cells. The result is a feed-forward loop where inflammation begets more senescence, and vice versa [11].

Senolytics are a class of pharmacological agents designed to selectively eliminate SCs. The first senolytic compounds, including Dasatinib, Quercetin, Fisetin, and Navitoclax, were identified through a hypothesis-driven strategy based on the selective vulnerability of SCs. These agents were subsequently confirmed using the same hypothesis-driven approach [12]. In contrast, senomorphics do not induce SC death but instead modulate the senescent phenotype by suppressing SASP signaling, thereby attenuating the detrimental effects of senescence without direct cell clearance [13]. Several signaling pathways mediate the interplay between senescence and inflammation in vascular tissues (Table 1).

Molecular pathways linking cellular senescence and chronic inflammation in vascular aging.

| Pathway | Role in senescence & inflammation |

|---|---|

| NF-κB | Central regulator of SASP transcription and inflammatory gene expression [14, 15] |

| p53/p21 | Initiates senescence in response to DNA damage [16] |

| p16/Rb | Maintains senescence and suppresses proliferation [17] |

| NLRP3 inflammasome | Activated by SASP, promotes IL-1β and IL-18 secretion [18] |

| mTOR | Modulates SASP and autophagy, influencing senescence phenotype [19] |

mTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin; SASP: senescence-associated secretory phenotype; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NLRP3: NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3; Rb: retinoblastoma protein.

Recent evidence demonstrates that anti-infective agents modulate the same biological pathways that drive vascular aging, creating a clinically significant mechanistic intersection. Human epidemiological evidence also supports a potential link between cumulative anti-infective exposure and vascular aging trajectories. A recent nationwide retrospective cohort study involving 2.16 million adults aged 40–79 years from the Korean National Health Insurance Service demonstrated that increasing cumulative antibiotic use over a 5-year exposure window was associated with a dose-dependent elevation in incident cardiovascular disease risk during a 10-year follow-up period. Compared to non-users, individuals with ≥ 365 cumulative exposure days exhibited a 10% higher hazard of developing CVD (aHR 1.10; 95% CI 1.07–1.13), whereas shorter exposures (1–180 days) showed either negligible or modest risk increments [20]. In a prospective birth-cohort study of approximately 2,996 children (the WHISTLER cohort), recent systemic anti-infective agent exposure was associated with measurable preclinical vascular alterations at age 5. Each antibiotic prescription within the 3 months preceding vascular assessment resulted in an increase of 18.1 µm in carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT; 95% CI: 4.5–31.6; p = 0.01), while prescriptions within the prior 6 months were associated with a 10.7 µm increase in CIMT (95% CI: 0.8–20.5; p = 0.03). Additionally, each antibiotic prescription in the preceding 6 months was linked to a reduction of 8.3 mPa–1 in carotid artery distensibility (95% CI: –15.6 to –1.1; p = 0.02) [21]. Although these absolute differences are modest and don’t measure vascular-aging biomarkers (e.g., arterial stiffness, endothelial senescence), increased CIMT and reduced arterial distensibility are well-established early biomarkers of arterial stiffening and adverse vascular remodeling. Another notable study by Snell et al. [22] (2018) examined the effects of bactericidal antibiotics, such as erythromycin (macrolide) and ivermectin (antiparasitic), in a rotifer model. The study found that these drugs significantly extended lifespan (by 8–42%) and improved healthspan by enhancing mitochondrial activity and mobility during aging. Interestingly, the study demonstrated that lifespan extension could occur even when drug treatment was initiated in middle age, suggesting that some of these agents may target aging mechanisms independent of their antimicrobial properties [22].

In a study using the Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS, progeria) mouse model (Zmpste24–/–), compelling evidence shows that anti-infective agents can modulate fundamental hallmarks of vascular aging. Chronic doxycycline (DOX) administration significantly increased median survival by approximately 20–25% compared with untreated HGPS mice (p < 0.01), while improving multiple age-related phenotypes, including bone mineral density (↑ 18%), tissue mass retention (p < 0.05), colon length preservation, and exercise endurance (running time ↑ 30%). DOX reduced systemic and vascular inflammation, with IL-6 serum concentrations reduced by nearly 50% (p < 0.001), and normalized pathological α-tubulin K40 acetylation in aortic tissue, a modification driven by NAT10 that contributes to nuclear envelope fragility and vascular degeneration in HGPS. DOX also lowered senescence burden across tissues, reducing SA-β-gal accumulation and DNA damage foci [γ phosphorylated form of the histone H2AX (γH2AX)] in vascular cells. These findings demonstrate that an anti-infective drug can directly modulate vascular-aging pathways, including inflammation, cytoskeletal remodeling, and senescence, even in a severe premature-aging model. Although HGPS represents an extreme form of accelerated vascular aging rather than physiological aging, these data support a hypothesis-generating framework in which certain antibiotics may exert senomorphic or vasculo-protective actions beyond their antimicrobial role [23].

Equally, fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides, for example, directly impair mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, increase proton leak, and elevate reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in human cell models, replicating hallmark features of aging and oxidative stress [24, 25]. Some antibiotics have been shown to trigger mitochondrial stress, increase ROS production, impair oxidative phosphorylation, and dysregulate proteostasis processes, all of which parallel those observed during vascular aging and endothelial senescence.

Some broad-spectrum antibiotics disrupt key gut microbial species, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Akkermansia muciniphila, reducing short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production and increasing pro-inflammatory metabolites, including trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which accelerate endothelial senescence and vascular inflammation [26]. However, ceftriaxone a third generation cephalosporin, has been extensively studied for its neuroprotective activities in [27]. Furthermore, antibiotics with antitumor activity, such as anthracyclines, are also implicated in drug-induced vascular dysfunction [28, 29]. Conversely, other anti-infective classes exhibit protective or senomorphic properties. Macrolides, rifampicin, and tetracyclines have been shown to suppress SASP mediators, reduce IL-6 and IL-1β signaling, stabilize mitochondrial function, and enhance autophagy, thereby attenuating cellular senescence in human inflammatory conditions [30, 31].

In a mixed in vivo and in vitro study, Hu et al. [32], 2022 showed that the antiviral nucleoside analogue acyclovir (10 mg/kg/day) improved multiple metabolic hallmarks linked to vascular aging in HFD/STZ-induced diabetic C57BL/6N mice (n = 6 per group). Acyclovir significantly lowered fasting blood glucose and HbA1c, improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, and attenuated diabetic dyslipidaemia by reducing serum triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL-C, with no change in HDL-C. In parallel, hepatic oxidative stress was alleviated, with increased total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD) activity and reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. In HepG2 insulin-resistant, oxidative and glycative stress models, low-nanomolar acyclovir (10–100 nM) increased cell viability, enhanced glucose consumption, and lowered ROS and AGE accumulation. Mechanistically, acyclovir directly activated pyruvate kinase M1 (PKM1), leading to increased AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation and SIRT1 expression in liver tissue and HepG2 cells; PKM1 knockout abolished these effects [32]. These findings provide rare human evidence that even anti-infective exposure may leave detectable structural imprints on the vasculature, supporting the broader hypothesis that cumulative anti-infective exposure contributes to long-term vascular aging trajectories.

In an extensive human cohort analysis, people living with HIV (PLWH) demonstrated a significantly higher burden of clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), a genomic hallmark of ageing and cardiovascular risk. Using data from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (n = 600; median age 44 years), the study found a CHIP prevalence of 7% in PLWH, compared with approximately 3% in matched controls (propensity-score-matched ARIC cohort, n = 8,111; p = 0.005). Notably, the most frequently mutated gene was ASXL1, a CHIP driver mutation strongly associated with inflammation and vascular disease. Although the study did not identify specific antiretroviral drugs as direct drivers of CHIP, all participants were receiving lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART), and the authors highlight that chronic HIV infection, persistent immune activation, and long-term ART exposure together create a pro-inflammatory milieu that may accelerate acquisition of CHIP-associated somatic mutations. These findings support the concept that chronic infection and its treatment environment contribute to premature biological aging, providing human-level evidence linking infectious disease history, hematopoietic aging, and downstream vascular risk [33, 34].

These contrasting effects highlight the “Janus-faced” nature of anti-infective agents, where some drugs mitigate vascular-aging mechanisms while others exacerbate them. Explicitly introducing these mechanistic links early provides the biological rationale for examining anti-infective drugs as modulators, both harmful and protective of the vascular aging pathway.

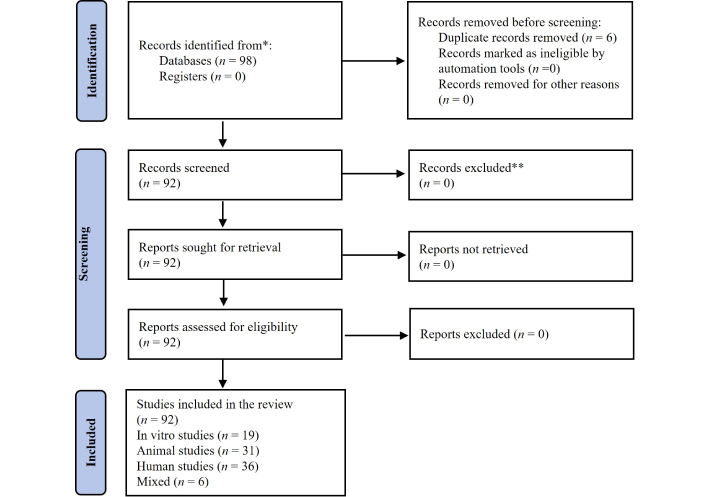

This review was conducted to identify, screen, and synthesize mechanistic and translational evidence linking anti-infective drugs to vascular aging pathways. Studies were stratified by evidence level. We categorized the studies into human observational studies, animal models, and in vitro models based on the methodologies used and study population. The majority of the included studies were in vitro or animal studies, whereas human observational studies comprised a smaller proportion. We emphasize that the mechanistic inferences in this review are primarily based on preclinical models, which provide valuable insights into potential mechanisms but have limitations in directly translating to human vascular aging. Hence, a total of 98 records were initially retrieved from indexed scientific databases, of which 6 duplicates were removed, leaving 92 unique records that were assessed in full and included in the final synthesis. These were categorized into in vitro (n = 19), animal (n = 31), human (n = 36), and mixed (n = 6) studies, as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

PRISMA-based methodological workflow of the systematic review. A structured search in indexed scientific databases identified 98 records, of which 92 met the inclusion criteria. Studies were categorized into in vitro (n = 19), animal (n = 31), human (n = 36), and mixed (n = 6). Data were extracted and assessed for risk of bias using SYRCLE (animal), RoB-2 (clinical trials), ROBINS-I (observational), and narrative evaluation (in vitro). Results were synthesized narratively due to heterogeneity across models and outcomes. Adapted from Page et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019.

We systematically searched peer-reviewed literature published between 2000 and 2024. Eligible studies were required to examine the effects of any anti-infective drug class, including antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, and antiparasitics, on vascular-aging hallmarks, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, endothelial senescence, inflammation, proteostasis disruption, or vascular functional decline. Studies were included if they contained mechanistic or outcome-level data relevant to these domains. In vitro studies were included if they used endothelial, vascular smooth muscle, or mammalian cell models to quantify senescence markers, mitochondrial respiration, ROS production, autophagy, angiogenesis, or SASP-associated effects. Animal studies were eligible if they used mammalian models [e.g., ApoE−/− mice, deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt rats] to assess vascular stiffness, plaque burden, endothelial function, vascular inflammation, or gut-vascular axis disruption following anti-infective exposure. Human studies included randomized trials, observational cohorts, and clinical investigations assessing vascular or metabolic dysfunction in populations exposed to anti-infectives [e.g., macrolides, protease inhibitors (PI)]. We excluded studies lacking vascular-aging endpoints, non-mechanistic commentaries, studies without full text, and those focusing solely on antimicrobial resistance without reporting host biological outcomes.

Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts. No records were excluded during full-text review, as all 92 studies met prespecified criteria. Extracted variables included:

Study design and model type.

Anti-infective class, dose, and duration.

Vascular-aging biomarkers (p16INK4a, p21, SA-β-gal, ROS, mitochondrial function, etc.).

Mechanistic pathways involved (e.g., SASP, gut-vascular axis changes, mitochondrial injury).

Vascular effects.

All human studies meeting mechanistic vascular-aging endpoints were included regardless of design.

Risk of bias was assessed using validated tools matched to the study design:

SYRCLE for animal studies (e.g., randomization, blinding, attrition).

RoB-2 for clinical trials.

ROBINS-I for observational human studies.

Narrative appraisal of in vitro studies with emphasis on dose relevance, replication, and endpoint validity.

Due to heterogeneity across experimental models, drug classes, outcome definitions, and biomarker reporting, meta-analysis was not feasible. Evidence was synthesized narratively, stratified by study type and drug class, consistent with PRISMA 2020 recommendations. This systematic review was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD420251156088).

Antibiotics are a diverse group of chemical substances, either naturally derived or synthetically produced, that are primarily used to treat bacterial infections. Since the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928, antibiotics have revolutionized modern medicine, saving countless lives and enabling complex medical procedures such as surgeries, organ transplants, and chemotherapy by effectively controlling infectious complications [35]. Anti-infective agents exert their antimicrobial activity through diverse molecular mechanisms, including inhibition of bacterial cell wall biosynthesis (e.g., β-lactams), suppression of protein synthesis (e.g., tetracyclines and macrolides), disruption of nucleic acid replication and transcription (e.g., fluoroquinolones), and interference with essential metabolic pathways (e.g., sulfonamides) [36].

Historically, the focus on antibiotics has centered on their antimicrobial properties. However, azithromycin and roxithromycin have recently been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as macrolide antibiotics with senolytic activity [22]. Therefore, evidence suggests that these compounds can exert significant off-target effects on mammalian cells, independent of their bactericidal or bacteriostatic functions. This includes modulation of mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, inflammation, and even cellular senescence, an area of increasing interest in the fields of ageing and age-related diseases [31, 37]. These off-target effects have significant implications beyond infection control, particularly in the context of age-related pathologies [38]. For instance, antibiotic treatment with the fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin has been shown to magnify Ang II-induced VSMC senescence via AMPK/ROS interactions in vitro, suggesting that antibiotics can potentiate the deleterious effects of Ang II signaling (a hallmark of ageing) in vascular cells [39]. Angiotensinogen is a well-documented neurohormone implicated in various cardiovascular and inflammation-dependent diseases [40, 41].

Casagrande Raffi et al. [42] (2024) identified the mitochondrial calcium transporter SLC25A23 as a selective vulnerability in senescent cancer cells. The cationic ionophore antibiotic salinomycin phenocopied SLC25A23 suppression, disrupting calcium homeostasis and oxidative phosphorylation, increasing ROS, and triggering multiple parallel death pathways (apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis). Importantly, salinomycin induced IL-18 secretion, which recruited NK and CD8⁺ T cells to further eliminate senescent tumor cells. When combined with a death receptor-5 (DR5) agonist antibody, salinomycin exhibited potent and synergistic senolytic activity in vitro and in vivo, underscoring a promising strategy of pairing pro-senescence therapies with senolytics to prevent the detrimental accumulation of senescent cancer cells [42].

The gut microbiome is now recognized as a central regulator of vascular aging and age-related cardiovascular disease [43]. Commensal taxa such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Akkermansia muciniphila, and Roseburia spp. are major producers of SCFAs, notably butyrate, propionate, and acetate, which exert vasculoprotective effects by maintaining gut-barrier integrity, dampening nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)-driven inflammation, enhancing regulatory T-cell (Treg) function, and supporting endothelial NO bioavailability and mitochondrial homeostasis [44]. Antibiotic exposure, particularly with broad-spectrum agents, reduces the abundance of these SCFA-producing genera and overall microbial diversity, thereby lowering SCFA levels and predisposing to systemic low-grade inflammation and endothelial dysfunction [45].

In parallel, dysbiosis can favor the expansion of pro-inflammatory taxa, including certain Proteobacteria and Bacteroides species, which increase production of trimethylamine (TMA), especially in Desulfovibrio and Clostridium species, which harbor TMA and endotoxin (LPS) in Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis species. TMA is converted in the liver to TMAO, a metabolite that promotes age-like endothelial dysfunction, vascular oxidative stress, and arterial stiffness in both preclinical models and humans. Elevated circulating TMAO levels and LPS activate TLR4/NF-κB signaling, increase ROS generation, and impair eNOS-mediated NO production, thereby accelerating vascular aging phenotypes [46].

Bile acids (BAs), which are amphipathic metabolites derived from cholesterol synthesized in the liver, are modified by gut microbiota, including Clostridium, Bacteroides, and Lactobacillus species. These bacteria convert primary BAs into secondary BAs, such as deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA), which play a substantial role in the process of vascular aging [44]. Emerging evidence indicates that microbial-host metabolic networks beyond direct mitochondrial or oxidative stress may also mediate vascular aging. In particular, BAs, beyond their conventional role in lipid absorption, act as metabolic regulators influencing vascular homeostasis via signaling through receptors such as Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and TGR5. Dysregulation of the BA network has recently been linked to pathological vascular calcification (VC), a major determinant of arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events. The review by Wang et al. [47] (2023) documents how alterations in BA metabolism and signaling can drive VSMC transdifferentiation, oxidative stress, inflammation, and calcium-phosphate deposition in the vascular wall, all processes that overlap mechanistically with antibiotic-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, redox imbalance, and senescence.

Multiple mechanisms connect BAs to vascular dysfunction, mainly via inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular injury [47]. In ECs, BAs like chenodeoxycholic acid stimulate ROS generation, which activates NF-κB and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, resulting in elevated adhesion molecule expression and inflammatory responses. Hydrophobic BAs intensify oxidative stress in VSMCs, contributing to tissue damage and remodeling. Interestingly, recent metabolomics-based research shows that the bile-acid metabolite LCA, which increases during caloric restriction, can by itself recapitulate key anti-ageing effects across species, including activation of AMPK, enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis and function, improved muscle regeneration, and extended healthspan in mice, flies, and worms. The study by Qu et al. [48] (2025) found that LCA treatment induces AMPK activation at physiological concentrations similar to those observed under caloric restriction, inhibits mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, promotes autophagy and cellular energy homeostasis, and reduces age-associated decline in physiological performance. These findings imply that changes in bile-acid metabolism, a facet potentially influenced by antibiotic- or anti-infective-induced gut microbiome perturbation, may contribute substantially to vascular and systemic ageing, beyond classical mitochondrial toxicity or ROS-driven damage [48].

Recent studies have highlighted the microbiota’s impact on cellular senescence, a key hallmark of aging characterized by irreversible cell cycle arrest and a proinflammatory secretory profile known as the SASP. Disruptions in the gut microbiome, particularly through the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, can disrupt this delicate balance and accelerate senescence in distant tissues, including the vasculature [49].

Antibiotics, while life-saving, are nondiscriminatory in their action and often cause collateral damage to the gut microbiota. This dysbiosis alters microbial diversity and depletes beneficial commensals’ metabolites, including SCFAs such as butyrate and propionate. These SCFAs are known to possess anti-inflammatory and anti-senescent properties, in part by modulating histone acetylation, immune regulation, and mitochondrial function [50]. The decline in SCFA has been linked to increased oxidative stress and systemic inflammation, two major inducers of cellular senescence, particularly in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Furthermore, the reduction in microbial metabolites impairs intestinal barrier function, resulting in the translocation of microbial products, such as LPS, into circulation, which can trigger chronic low-grade inflammation (inflammaging) and potentiate senescent phenotypes in peripheral tissues [51].

Additionally, antibiotic-induced disruption of the microbiome has been shown to affect mitochondrial function, a central regulator of cellular energy and redox homeostasis. Antibiotics such as kanamycin, ampicillin, and ciprofloxacin have been shown to impair mitochondrial translation and bioenergetics, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, a known trigger of senescence through activation of the DNA damage response (DDR) and accumulation of ROS [52]. These alterations not only contribute to tissue degeneration but may also exacerbate vascular aging by promoting endothelial dysfunction and reducing NO bioavailability. Importantly, a dysfunctional gut-mitochondria axis, as influenced by both microbiome alterations and antibiotic exposure, can synergize to induce premature vascular senescence.

Moreover, the gut microbiota modulates host epigenetics, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA (ncRNA) expression. Antibiotics that perturb microbiota composition may therefore have downstream effects on the epigenetic regulation of genes involved in cell cycle control and stress responses. For instance, butyrate, a microbial metabolite, functions as a histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi), thereby influencing chromatin structure and gene expression patterns that may suppress or delay the onset of senescence [53]. The loss of this regulatory influence following antibiotic treatment may promote unchecked cellular stress signaling and senescence-related transcriptional programs.

There is also growing evidence that the gut microbiota influences nutrient-sensing pathways, including the insulin/IGF-1 signaling axis, AMPK, and mTOR [54, 55]. Alterations in microbiota composition following antibiotic exposure can shift nutrient signaling, possibly by altering microbial metabolites that serve as cofactors or regulators of host enzymes. Disruption of these pathways has been associated with regenerative capacity in vascular and other tissues [56].

In ageing models, antibiotic-induced dysbiosis has been shown to blunt neurogenesis, alter immunity, and increase systemic inflammation, all of which are closely coupled to accelerated cellular senescence [57]. It is worth noting that although certain antibiotics have been explored for their potential senolytic properties, such as azithromycin or DOX, their systemic impact on the gut microbiome and downstream pro-senescent signaling often outweigh these benefits in the context of chronic or repeated exposure [58–61].

For instance, DOX reinstated the levels of key aging-related proteins, such as lamin B1 and the DNA repair factors KU70 and KU80. Moreover, it mitigated cellular senescence and dampened the SASP, leading to reduced inflammation in ethanol-exposed human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) [62]. In ApoE−/−/OVX mouse models, DOX treatment reduced ROS levels and decreased both the expression and activity of MMP-2, which correlated with a significant attenuation of inflammation-driven atherosclerotic lesion formation [63]. In DOCA salt-treated rats, DOX lowered systolic blood pressure, ameliorated endothelial dysfunction, and attenuated aortic oxidative stress and inflammation. DOX also reduced lactate-producing gut bacteria and circulating lactate levels, strengthened gut barrier integrity, corrected endotoxemia and elevated plasma noradrenaline, and restored Treg abundance in the aorta. Collectively, these findings indicate that DOX, via modulation of the gut microbiota alongside its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions, mitigates endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in this low-renin hypertensive model [64].

Additionally, in cystic fibrosis patients, lung inflammation and fibrosis are classic, resulting in lung stiffening and an inability to breathe. Fibrosis is an age-related disorder associated with increased numbers of myofibroblasts (SCs) [65]. Azithromycin has been shown to act as an anti-inflammatory drug and reduce SASP mediators, such as IL-1β and IL-6, by targeting senescent myofibroblast cells [66]. Equally, senescent biomarkers have been identified in progressive endometriosis. For instance, in endometrial stromal cells with endometriosis (eESCs), and ovarian endometriosis OE cyst-derived stromal cells CSCs, senescent biomarkers such as SA-β-gal, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A locus (p16INK4a), and lamin B1 are significantly elevated. Azithromycin impaired cell proliferation (Ki67), fibrosis, and IL-6 (SASPs) levels [67].

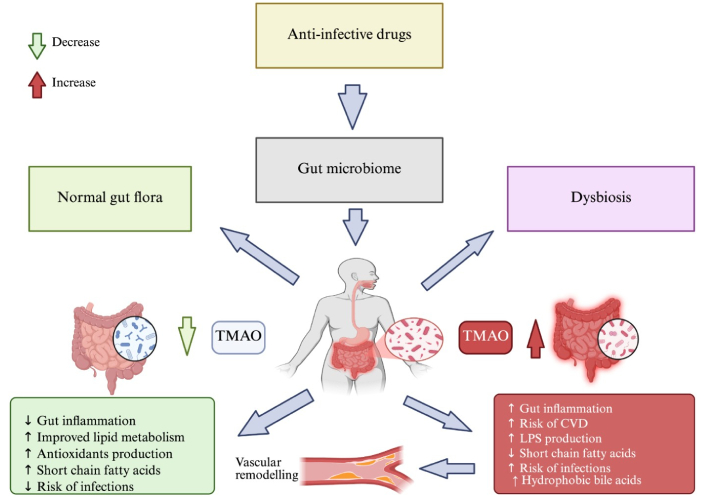

However, broad-spectrum antibiotics such as ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, vancomycin, and metronidazole significantly deplete beneficial gut bacteria like Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Faecalibacterium, leading to compromised epithelial integrity and increased gut permeability. This allows microbial products, such as LPS, to enter systemic circulation, stimulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, central mediators of inflammaging. Persistent inflammation induces cellular stress responses, resulting in oxidative damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and activation of senescence pathways, as evidenced by elevated p16INK4a, p21, and SA-β-gal expression. These SCs further propagate inflammation through their SASP output, establishing a feedback loop that accelerates age-related tissue degeneration and functional decline [50, 51]. Interestingly enough, these broad-spectrum antibiotics have demonstrated beneficial effects in lowering TMAO (Figure 2), forming bacteria when used for only limited durations. TMAO is directly correlated to inflammation and senescence [68, 69].

Diagram of the gut-vascular axis illustrating how antibiotics disrupt microbial balance (dysbiosis), leading to SCFA depletion, TMAO accumulation, immune activation, and altered microbial metabolites. These pathways converge to promote vascular senescence, with protective (green) and harmful (red) mechanisms highlighted. SCFA: short-chain fatty acid; TMAO: trimethylamine N-oxide. Created in BioRender. Silumbwe, C. (2026) https://BioRender.com/2vmlldy.

While bacterial dysbiosis is widely recognized in various age-related diseases, emerging evidence highlights the essential role of the gut mycobiome, the fungal component of the microbiota, in vascular homeostasis [70]. The gut mycobiome, though constituting a minor fraction of total microbiota biomass, engages in extensive cross-kingdom interactions with bacteria, modulating immune tone, barrier integrity, and metabolic yields relevant to vascular health. Fungal dysbiosis, whether from antifungal therapy (e.g., fluconazole, voriconazole) [71, 72], long-term antiviral regimens (e.g., tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, efavirenz) in HIV patients [73], or certain broad antimicrobials with antifungal activity, can disrupt this balance [74, 75].

Overgrowth of pro-inflammatory fungi, such as Candida albicans and Candida glabrata, along with loss of beneficial taxa, such as Saccharomyces boulardii, alters epithelial tight junction expression and increases intestinal permeability. This facilitates the translocation of fungal cell wall components, such as β-glucans and mannans, into the circulation, activating pattern recognition receptors (e.g., Dectin-1, TLR2) on specific immune cells [76]. Effects include NF-κB-driven cytokine release, oxidative stress, and endothelial activation, all of which are specific to the current hallmarks of vascular ageing [77].

Moreover, fungal dysbiosis can exacerbate bacterial dysbiosis effects by altering SCFA availability and shifting BA metabolism, both of which influence vascular tone, mitochondrial efficiency, and nutrient-sensing pathways (AMPK/mTOR) [78]. In aging individuals, this compounded microbial disruption accelerates VSMC senescence, promotes a pro-thrombotic endothelium, and impairs reparative angiogenesis. Thus, mycobiome disruption should be considered alongside bacterial dysbiosis as a parallel and synergistic pathway by which anti-infective agents contribute to endothelial dysfunction, vascular stiffening, and reduced regenerative capacity in the ageing vasculature [79].

Maintaining a functional proteome relies on proper protein folding, quality control, and clearance systems, principally the UPS and autophagy-lysosome pathways. Ageing causes deterioration in both systems, leading to the accumulation of misfolded or aggregated proteins. This proteostatic failure is a recognized hallmark of aging and is implicated in disorders ranging from neurological, metabolic, and cardiovascular diseases [2, 80–83]. Conceptual and experimental studies further suggest that certain antibiotics can perturb proteostasis and inter organelle stress signaling, linking anti-infective exposure to senescence-related pathways. Taken together, these data justify discussing epigenetic and proteostasis mechanisms as biologically plausible axes through which anti-infective agents might influence vascular aging, while acknowledging that direct vascular evidence remains limited and largely hypothesis-generating [84].

In a rat model of chemically induced liver fibrosis, treatment with the antimalarial agent dihydroartemisinin (DHA) led to a marked accumulation of senescent activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) along fibrotic scars: more than 80% of p16-positive cells co-expressed p53, while fewer than 9% remained Ki-67 positive, indicating effective cell-cycle arrest and senescence rather than proliferation (Zhang et al. [85], 2017). Concurrently, DHA treatment significantly reduced collagen deposition and histological fibrosis scores in a dose-dependent manner compared with untreated fibrotic controls (p < 0.05). In vitro, DHA shifted HSCs toward G2/M cell-cycle arrest and increased SA-β-gal positivity, alongside upregulation of senescence regulators (p53, p16, p21, HMGA1), confirming senescence induction by DHA. Mechanistically, this senescence induction required activation of autophagy and accumulation of transcription factor GATA6; knockdown of GATA6 abolished the effect, demonstrating a causal link. These findings suggest that DHA can suppress fibrogenic cell activation via induction of senescence, thereby limiting extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation, a process conceptually analogous to ECM remodeling and fibrosis in vascular aging. Thus, anti-infective agents such as DHA may, under specific conditions, modulate cell homeostasis and tissue remodelling in a way that could impact vascular aging trajectories [85].

In a landmark proteomics study, antibiotic exposure (aminoglycosides) induced frequent clustered translation errors, up to four consecutive amino-acid misincorporations per peptide, with downstream error probability reaching 0.25–0.40 under drug-bound ribosome conditions, and an overall error-cluster frequency up to 10,000-fold above stochastic expectation. The resulting error-laden proteins triggered proteotoxic stress, protein aggregation, heat-shock response activation, and impaired cell viability, even at sub-lethal drug concentrations. Given that proteostasis failure, protein misfolding, and aggregation are established drivers of endothelial senescence, mitochondrial dysfunction, and vascular remodeling, this evidence provides a plausible mechanistic link between aminoglycoside exposure and accelerated vascular ageing, albeit currently restricted to bacterial models [86–88].

Kalghatgi et al. [52] demonstrated that fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and β-lactams trigger mitochondrial dysfunction in mammalian cells, causing profound reductions in basal and maximal respiration and a surge in mitochondrial ROS and H2O2 production. This oxidative stress environment is a potent inducer of protein misfolding, oxidation of cysteine and methionine residues, protein carbonylation, and aggregation of damaged polypeptides, classical markers of proteostasis failure. In their study, bactericidal antibiotics increased oxidized DNA (8-OHdG), protein carbonyls, and lipid peroxidation by 2–4-fold (p < 0.01) in human epithelial cells, while mice exposed for 2–16 weeks showed systemic increases in ROS, protein nitration, and upregulation of antioxidant genes such as Sod2 and Gpx1 (≥ 2-fold, p < 0.05). Chronic oxidative stress and accumulation of misfolded or oxidized proteins are recognized triggers of the unfolded protein response (UPR), ER stress activation (PERK-eIF2α, ATF4, CHOP pathways), and impaired autophagy, all of which are well-established drivers of cellular senescence and aging phenotypes. Within vascular tissues specifically, proteostasis decline promotes endothelial dysfunction, reduced nitric-oxide bioavailability, heightened inflammatory signaling, and ECM remodeling, contributing to arterial stiffening and vascular aging. Thus, although the study did not directly examine vascular cells, its finding that bactericidal antibiotics induce widespread oxidative damage and protein-level injury provides a mechanistic foundation for the hypothesis that anti-infective agents may accelerate vascular aging via proteostasis collapse, particularly when mitochondrial injury, ROS generation, and impaired protein quality control converge in long-lived vascular endothelial or smooth-muscle cells. Fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and β-lactams have been shown to induce mitochondrial dysfunction and increased ROS in mammalian cells. This oxidative damage affects proteins, lipids, and DNA, creating additional substrates for UPS removal and eventually saturating its capacity [52]. This could alternatively activate AMPK. However, sustained dysfunction may lead to metabolic inflexibility, chronic mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) activation, organelle accumulation, and impaired autophagy, similar to observations in nutrient-starved cells [89]. This consequently leads to senescence and the expression of pro-inflammatory signals, typically observed in inflammation-dependent disorders [60, 89].

Some antibiotics, particularly macrolides such as azithromycin and erythromycin, can interfere with autophagic flux. They increase lysosomal pH or disrupt autophagosome-lysosome fusion, leading to the accumulation of undegraded proteins and damaged organelles [88]. In cystic fibrotic patients, where azithromycin has demonstrated significant clinical outcomes, experimental data from Renna et al. [90], 2011 showed that it inhibited autophagosome-lysosome fusion in human epithelial and macrophage models, increasing LC3-II accumulation by 2.5–4.0-fold, elevating p62/SQSTM1 and ubiquitinated protein aggregates by 2–3.5-fold, and reducing lysosomal acidification by 40–60% (p < 0.001). These defects reflect a profound blockade of autophagic flux, leading to impaired clearance of misfolded proteins and damaged mitochondria. Classically, persistent autophagy inhibition triggers ER stress, UPR activation (PERK-eIF2α-ATF4/CHOP), and redox imbalance, canonical pathways that drive proteostasis collapse, mitochondrial dysfunction, senescence, and chronic inflammation. This was further associated with an increased non mycobacteria tuberculosis (NMT) infection susceptibility [90].

Mitochondrial damage triggers a dysfunctional mitophagy response, leading to inefficient clearance of damaged mitochondria. This failure leads to persistent ROS and DNA damage, further promoting inflammation and senescence [33]. Interestingly, long-term administration of the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (50 mg/kg) to middle-aged mice paradoxically extended both median lifespan (786 vs. 689 days; 11.8% increase, p = 0.0002) and maximum lifespan (11.4%) despite evidence of impaired autophagic flux, proteasome inhibition, and altered glycogen metabolism according to Doeppner et al. [91], 2022. Treated animals displayed 30–40% accumulation of autophagosomes (↑ LC3B-II), a 25–35% reduction in proteasome activity, and decreased hepatic glycogenolysis, together indicating a profound shift in nutrient and proteostasis pathways. In the context of vascular ageing, these findings suggest that partial inhibition of canonical pro-longevity pathways (autophagy, proteasome activity) may still yield lifespan benefits by inducing compensatory metabolic reprogramming and stress adaptation, possibly via altered AMPK-mTOR and NAD⁺/sirtuin nutrient-sensing axes. Such paradoxical benefits highlight the complexity of targeting autophagy and proteostasis in vascular endothelium, where low-grade stressors may mimic hormesis, enhancing resilience to oxidative stress and delaying senescence [91].

Currently, no published study directly demonstrates that infections or anti-infectious agents can cause epigenetic modifications. However, both anti-infectious agents and infections may alter the expression profiles of microRNAs (miRNAs) and long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), which, in turn, regulate key epigenetic enzymes such as DNA methyltransferases (DNMT) and histone-modifying proteins [92, 93]. Crimi et al. [94] (2020) review offers important, necessary clinical evidence that bacterial infections, often managed with antimicrobial therapy, can induce substantial and persistent epigenetic remodeling in human tissues. Across multiple patient-derived samples, they documented alterations in DNA methylation patterns, histone acetylation and deacetylation states, and differential expression of ncRNAs, all of which regulate inflammatory signaling, immune activation, and tissue remodeling. These host-directed epigenetic changes, observed in epithelial and immune cells exposed to multidrug-resistant organisms, demonstrate that infection and its treatment can reprogram chromatin architecture in vivo [94].

Clinical and experimental evidence indicates that bacterial infections, often involving drug-resistant strains, can leave lasting epigenetic marks in host cells. For example, infection with Helicobacter pylori is associated with hypermethylation of key epithelial genes such as CDH1, WW domain-containing oxidoreductase (WWOX), and mutL homolog-1 (MLH1), while Listeria monocytogenes and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have been shown to induce histone hyperacetylation or deacetylation, respectively, in human endothelial or immune cells; these chromatin changes alter gene expression programs long-term. Moreover, circulating miRNAs (e.g., miR-361-5p, miR-889, miR-576-3p) are consistently upregulated in patients with chronic or drug-resistant bacterial infections. Such epigenetic reprogramming may create persistent changes in host cell phenotype, potentially contributing to tissue remodeling, chronic inflammation, impaired repair, and, over time, accelerated vascular aging [95–98]. Although evidence in vascular cells is still lacking, these findings provide a biologically plausible epigenetic axis by which repeated infections or anti-infective treatments might accelerate vascular aging. While this review does not investigate vascular or endothelial tissue specifically, the pathways affected, including chronic inflammation, oxidative stress responsiveness, resolution of injury, and immune memory, are central to the biology of endothelial senescence and vascular aging. Thus, the study provides mechanistic plausibility that anti-infective exposures may influence long-term vascular aging trajectories through epigenetic drift or maladaptive chromatin remodeling, even though direct vascular evidence has not yet been established [94].

Ciprofloxacin has been shown to directly modulate host epithelial gene expression via epigenetic mechanisms, independent of its antibacterial activity. In HT-29 human colon epithelial cells, butyrate treatment normally induces strong upregulation of endogenous antimicrobial peptides, LL-37 and β-defensin-3, but co-exposure to ciprofloxacin significantly suppressed this induction in a dose-dependent manner, reducing LL-37 mRNA expression by approximately 45–60% at 20–40 µg/mL (p < 0.01), and β-defensin-3 expression by 40–55% in the same range (p < 0.05). These transcriptional changes were accompanied by a corresponding reduction in LL-37 protein levels, confirmed by western blot analysis. Mechanistically, ciprofloxacin exposure induced dephosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser10, a known regulatory mark associated with transcriptional activation, indicating that the antibiotic suppresses host defense gene expression through epigenetic modification rather than cytotoxicity. Importantly, in vivo validation using a rabbit model showed that ciprofloxacin reduced butyrate-induced mucosal cathelicidin (CAP-18) expression by 50%, reinforcing the physiological relevance of these findings. Hence, the authors argue that the modulation of host gene expression, including key innate immunity peptides, by ciprofloxacin (and clindamycin) occurs via epigenetic mechanisms, likely mediated by histone modifications, rather than purely via microbiota killing or direct bacterial effects [99]. However, because the study was conducted in colon epithelial cells and focused solely on innate-immunity endpoints, showing only a single histone modification (H3-Ser10 dephosphorylation) without broader epigenetic or vascular markers, its relevance to vascular aging remains speculative.

Recent evidence further supports the concept that antibiotics can disrupt host chromatin regulation and epigenetic homeostasis in a manner relevant to aging biology. Ljubić et al. [100] (2025) demonstrated that exposure to widely used antibiotics, geneticin, hygromycin B, and rifampicin, induces robust transcriptional activation of normally silenced pericentromeric α-satellite DNA in human cell lines, with transcription increasing by 1.6–3.0-fold in A-1235 cells and up to 4.9-fold in HeLa cells in a dose-dependent manner (all p < 0.02). This derepression was accompanied by a significant loss of the heterochromatin mark H3K9me3 and a reciprocal gain of the active chromatin mark H3K18ac, revealing antibiotic-induced erosion of heterochromatin integrity. Because satellite DNA activation and heterochromatin relaxation are tightly linked to genomic instability, DNA double-strand breaks, R-loop formation, chromosomal missegregation, and activation of the DDR, these findings are mechanistically important: heterochromatin breakdown is a central hallmark of both cellular senescence and vascular aging. Vascular endothelial and smooth-muscle cells rely on stable heterochromatin to maintain genome integrity, mitochondrial homeostasis, and controlled inflammatory signaling; thus, persistent heterochromatin destabilization is known to accelerate endothelial senescence, increase SASP cytokine release, impair nitric-oxide signaling, and promote arterial stiffening. Although the study did not directly assess vascular cells, the demonstration that clinically relevant antibiotics can alter host chromatin architecture and activate normally silenced repetitive elements provides a biologically plausible pathway by which anti-infective agents might influence vascular-aging trajectories. If similar epigenetic de-repression occurs in endothelial or vascular smooth-muscle cells, it could potentiate genomic instability-driven mitochondrial dysfunction, increase oxidative burden, enhance NF-κB-mediated inflammation, and ultimately accelerate the transition toward a senescent vascular phenotype [100].

Equally, by modulating ncRNA activity, this could indirectly reshape chromatin structure and gene expression, thereby contributing to ageing and disease course. This ncRNA-epigenetic axis highlights a novel and underexplored pathway through which antibiotics might influence long-term cellular functions. For example, Miravirsen, an antisense oligonucleotide targeting miR-122, has shown antiviral efficacy against hepatitis C virus (HCV) [101, 102]; lncRNA 9708-1 enhances antifungal defense in murine models of vulvovaginal candidiasis by upregulating FAK and strengthening epithelial barriers [103]; and emerging antiviral miRNA therapies, such as miRNA mimics or inhibitors, are being investigated to block viral replication or boost immune responses, particularly in SARS-CoV-2 [104].

Crimi et al. [94] (2020) reported that hypermethylation of DNA at the E-cadherin (CDH1), upstream transcription factor-1/2 (USF1/2), WWOX, and MLH1 loci in gastric mucosa was associated with malignant transformation, suggesting their potential as early disease biomarkers. In addition, miR-361-5p, miR-889, and miR-576-3p were found to be upregulated in tuberculosis patients. Similarly, Listeria monocytogenes indirectly promoted histone H3 hyperacetylation, triggering inflammatory responses in human ECs. In contrast, Pseudomonas aeruginosa secreted the quorum-sensing molecule 2-aminoacetophenone (2-AA), which directly induced H3 deacetylation and facilitated bacterial persistence in human monocytes. Together, these findings underscore the substantial role of infectious pathogens in modulating epigenetic mechanisms, a key hallmark of ageing [94].

In a whole-genome sequencing study of HSPCs from HSCT donors and recipients, de Kanter et al. [105] identified a subset of transplant recipients in whom multiple HSPC clones exhibited several-fold higher age-adjusted mutation burdens and a distinctive single-base substitution signature (SBSA) dominated by C>A transversions. In vitro exposure of human CD34⁺ HSPCs to ganciclovir (5 µM) significantly increased γ-H2AX signal and single-base substitutions compared with untreated cells. It recapitulated the SBSA mutational profile, thereby causally linking this nucleoside-analog antiviral to enhanced mutagenesis. Machine-learning analysis further detected SBSA in therapy-related leukemias and solid tumors of transplant recipients, where it contributed a substantial fraction of total mutations, including cancer driver events. These data provide strong mechanistic evidence that prolonged antiviral therapy can impose a persistent mutational “scar” on human stem cells, reinforcing genomic instability as a potential route through which anti-infective exposure may accelerate biological and vascular ageing in vulnerable populations [105]. Other mechanisms through which anti-infectious agents may modulate epigenetic response may include the following.

Bactericidal antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, kanamycin) impair mitochondrial function and increase ROS production in mammalian cells, causing oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins [52]. Kalghatgi et al. [52] (2013) provided compelling mechanistic evidence that clinically relevant concentrations of bactericidal antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, and kanamycin, induce significant mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in human epithelial and fibroblast cells. These agents caused sharp increases in intracellular ROS, mitochondrial superoxide, and H2O2 release (p < 0.01), accompanied by inhibition of electron transporter chain (ETC) complexes I (↓ 16–25%) and III (↓ 30–40%). Resulting oxidative injury was evident through elevated γ-H2AX foci, 8-OH-dG, protein carbonyls, and MDA. In vivo, antibiotic-treated mice exhibited parallel systemic oxidative stress, demonstrating physiological relevance. Importantly, antioxidant co-treatment (NAC) fully rescued mitochondrial and oxidative abnormalities without reducing antimicrobial efficacy [52]. Elevated ROS levels activate the DDR and deplete NAD⁺, a cofactor critical for SIRTUIN activities. Loss of sirtuin-mediated histone deacetylation (notably H4K16ac and H3K9ac) disrupts heterochromatin structure, impairs DNA repair pathways such as non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR), and exacerbates genomic instability and inflammation-induced senescence in vascular cells [106].

Krautkramer et al. [107] (2016) found that the gut microbiota profoundly influenced global histone post-translational modifications across multiple tissues. In germ-free mice, histone acetylation/methylation states differ markedly from those of conventionally colonized mice. However, supplementation with SCFAs, especially butyrate and propionate, restores histone modification patterns to those seen in colonized animals. Broad-spectrum antibiotics can reduce SCFA-producing bacteria by up to 70%, thus reducing SCFA availability [107]. Since SCFAs act as endogenous HDACi, their depletion skews chromatin toward hyper-repression of anti-inflammatory genes and expression of pro-inflammatory SASP gene programmes. In addition, altered microbiota affect the activity of DNMT and ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, contributing to site-specific DNA methylation changes that favor senescence and vascular inflammation [107, 108]. The compounding effects of mitochondrial dysfunction and epigenetic dysregulation, characterized by NAD⁺ depletion, histone hyperacetylation, and DNA methylation changes, lead to genomic instability, including increased γ-H2AX foci, telomere shortening, activation of retrotransposons, and DNA repair deficiency. In both ECs and VSMCs, these insults induce a senescent phenotype characterized by elevated p16INK4a/p21CIP1 expression, SASP secretion, oxidative stress, and dysfunctional ECM production. Senescent VSMCs shift towards a synthetic, pro-inflammatory phenotype, promoting arterial stiffening and plaque progression. ECs exhibit reduced NO bioavailability, increased permeability, impaired angiogenesis, and elevated inflammatory gene expression, all of which are signatures of vascular aging [2, 81, 83].

Beyond the well-documented off-target effects of antibiotics, emerging evidence suggests that other anti-infectious agents, including antivirals, antiparasitics, and antifungals, may significantly influence vascular ageing processes. These agents, through mechanisms such as mitochondrial toxicity, oxidative stress generation, and disruption of angiogenic and nutrient-sensing pathways, have the potential to induce endothelial dysfunction, accelerate vascular senescence, and impair tissue repair dynamics [106, 109, 110].

In primary human coronary artery ECs (HCAECs), PI (ritonavir and lopinavir) accelerated premature senescence, increased ROS, increased cell cycle inhibitors (p16INK4a, p21CIP1), reduced proliferation, and triggered SASP-associated inflammation. Senescence markers were also elevated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HIV patients receiving PI therapy [111–113].

Broad-spectrum antivirals (e.g., tenofovir, zidovudine, remdesivir), in cultured human aortic ECs (HAECs), caused mitochondrial membrane depolarization, elevated ROS, altered lysosomal content, reduced vWF expression, and signs of autophagy dysregulation and micronuclei formation, hallmarks of endothelial aging and dysfunction [112, 114–116]. In a study by Auclair et al. [117] to delineate which molecular pathways (especially SIRT1, USP18, inflammation, insulin signaling) are modulated by ART (dolutegravir, maraviroc, and ritonavir-boosted atazanavir) in HCAECs, and examine how ART influences vascular aging phenotypes, dolutegravir and maraviroc appeared to have protective or neutral effects (reducing inflammation, suppressing senescence) in coronary ECs; atazanavir/r, in contrast, promoted endothelial senescence and inflammation [117]. Other studies show that antiviral and ART stress converge on the miR-34a-SIRT1 axis to accelerate vascular aging [118–120]. In vitro, HIV-Tat protein (100 nM) or PI such as lopinavir/ritonavir (102 µM) significantly increased senescence in ECs, with SA-β-gal positivity increasing by 40% and SIRT1 protein decreasing by 40% (n = 6, p < 0.01); these effects were rescued by antagomiR-34a, confirming a causal role [118]. In vivo, mice exposed to NRTI (AZT, stavudine) displayed impaired acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation, accompanied by increased vascular superoxide; scavenging with tiron restored endothelial responses, implicating ROS-mediated NO quenching as the proximate mechanism of dysfunction [121]. Human data reinforce these findings: ECs from HIV-positive patients receiving ART exhibited elevated miR-34a levels and reduced SIRT1 levels compared with uninfected controls (n = 6–9, p < 0.05), correlating with vascular stiffness and endothelial dysfunction [118]. More broadly, induction of miR-34a under chronic antiviral stress has been associated with both cardiovascular disorders (atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction) and neurological complications (cerebrovascular ageing, BBB impairment), highlighting its role as a stress-responsive hub in vascular senescence [122, 123]. Additionally, in HIV-1 infected patients on highly active ART (HAART), the prognosis has significantly improved, but was associated with significant side effects such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular complications, and miR-34/SIRT1-dependent epigenetic modifications [124]. A surge in oxidative stress and, consequently, inflammation in human mononuclear cells, which are a type of white blood cell, was noted. This process is often linked to the development of inflammation-dependent disorders such as atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases [125, 126].

In human microvascular ECs (HMEC-1 or HUVEC), itraconazole inhibited VEGFR2 glycosylation and signaling, blocked endothelial proliferation, and suppressed in vivo angiogenesis. Impaired angiogenic capacity contributes to vascular aging and repair deficits. However, these cellular effects have shown benefits in antitumor therapy [127–129]. Head et al. [127] demonstrated that the antifungal itraconazole directly targets VDAC1 in ECs, disrupting a critical mitochondrial gatekeeper of metabolic flux. By binding to VDAC1, itraconazole reduced mitochondrial membrane potential by 30–40% and suppressed oxygen consumption by 25–35%, while simultaneously increasing mitochondrial ROS nearly twofold and reducing endothelial proliferation by 40%. In the context of nutrient sensing and vascular aging, these effects mirror age-associated impairments in mitochondrial nutrient utilization and redox signaling: reduced adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-linked respiration compromises energy sensing via AMPK-mTOR pathways, while excess ROS disturbs the balance of NAD⁺/sirtuin signaling. Collectively, itraconazole’s off-target action on VDAC1 illustrates how pharmacological disruption of mitochondrial nutrient sensing accelerates hallmarks of vascular aging, including bioenergetic decline, oxidative stress, and impaired endothelial repair [127, 128].

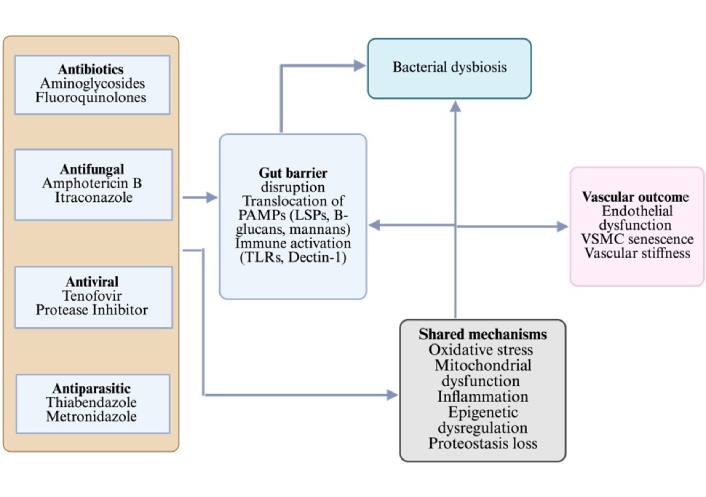

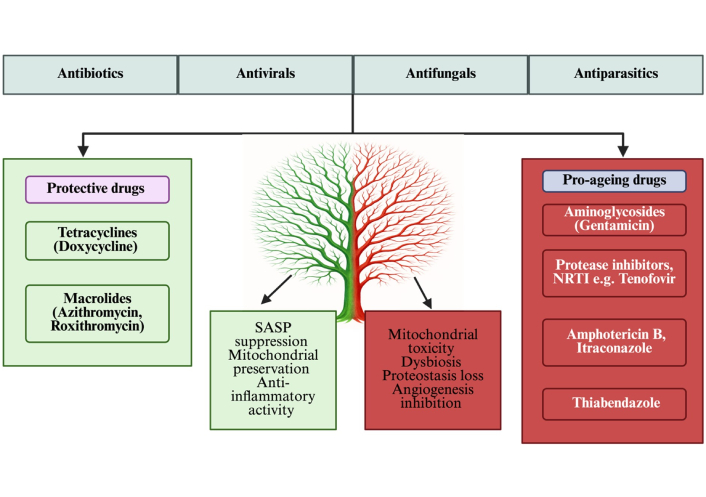

Furthermore, in a recent preclinical study, miconazole significantly reduced cellular senescence in colonic epithelial cells and improved colitis outcomes in a murine colitis model. Specifically, treatment reduced the proportion of SA-β-gal-positive cells and downregulated p16/p21 expression in DSS-injured colonic cells. In vivo, miconazole ameliorated weight loss, reduced bloody stools, and restored colonic mucosal integrity, concomitant with suppression of NF-κB inflammatory signaling and modulation of gut microbiota. These data suggest that miconazole might exert a senomorph-like effect under inflammatory stress [130]. In a vascular EC line (EA.hy926), amphotericin B (a polyene antifungal) induced membrane depolarization, decreased Ca2⁺ signaling, and reduced the cellular ATP/adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ratio by more than 30%, indicating mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired energy metabolism, both potential triggers for endothelial senescence and vascular dysfunction [131]. Interestingly, Ciclopirox (CPX), a topical antifungal agent and iron chelator, has been shown to induce senescence in HPV-positive cervical cancer lines, suppressing viral oncogenes and arresting proliferation even when mTOR signalling is impaired. With longer treatment, apoptosis follows. This suggests that specific antifungal agents may promote positive senescence and could be repurposed for cancer or aging interventions [132]. Repurposed from its antiparasitic use, thiabendazole has been shown to disrupt established blood vessels in animal models, acting as a vascular disrupting agent. It reversibly dismantles vascular structures and reduces angiogenesis in preclinical tumor models, suggesting potential effects on vascular homeostasis if applied chronically [133, 134]. A summary describing the implications of anti-infectious agents on vascular aging and a possible conceptual framework are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. They address study heterogeneity by introducing a multilayered, pathway-centric framework that integrates diverse findings across mitochondrial dysfunction, microbiome signaling, proteostasis failure, and senescence/SASP, enabling mechanistic synthesis without overstating direct clinical causality (Figures 3 and 4).

Flow chart showing the dual impact of anti-infectious agents on vascular ageing. Antibiotics disrupt the gut microbiota, leading to dysbiosis that, in turn, contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, and epigenetic deregulation. Antivirals (e.g., tenofovir, efavirenz), antifungals (e.g., itraconazole), and antiparasitics (e.g., thiabendazole) directly converge on shared mechanisms. Together, these pathways accelerate vascular aging outcomes, including endothelial dysfunction and impaired vascular repair. Created in BioRender. Silumbwe, C. (2026) https://BioRender.com/cqjy6qr.

Dual role of anti-infective drugs in vascular ageing. Protective agents such as tetracyclines (e.g., doxycycline) and macrolides (e.g., azithromycin) exert vasculoprotective actions by suppressing SASP, preserving mitochondrial function, and reducing inflammation. On the contrary, pro-ageing agents, including aminoglycosides (gentamicin), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin), antivirals (protease inhibitors), antifungals (itraconazole), and antiparasitics (thiabendazole), promote mitochondrial toxicity, proteostasis disruption, angiogenesis inhibition, and dysbiosis, thereby accelerating vascular ageing. SASP: senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Created in BioRender. Silumbwe, C. (2026) https://BioRender.com/2k1v3di.

This review highlights a potential paradigm shift in our understanding of anti-infectious agents not merely as anti-infectious agents, but as modulators of host cellular processes that intersect with ageing biology. Evidence suggests that certain antibiotics, particularly macrolides and tetracyclines, possibly possess senolytic or senomorphic properties that can influence vascular ageing through mechanisms such as SASP suppression, mitochondrial modulation, and epigenetic remodeling [135, 136]. Conversely, broad-spectrum antibiotics may exacerbate vascular senescence by disrupting the microbiome, inducing oxidative stress, and causing proteostatic collapse [137–139]. The vascular system, being susceptible to inflammatory and metabolic cues, is particularly vulnerable to antibiotic-induced off-target effects. These interactions have profound implications for ageing populations, where antibiotic exposure is frequent and vascular resilience is already compromised. Understanding the dualistic nature of antibiotics, both therapeutic and potentially pro-senescent, offers novel opportunities for drug repurposing. Despite increased attention to the role of anti-infectious agents in vascular aging and cellular senescence, several key research gaps remain unresolved. Much of the current evidence comes from in vitro and animal studies, with a striking paucity of human trials that evaluate vascular biomarkers, SASP profiles, and long-term outcomes. The effects of anti-infectious compounds are notably cell-type specific, differing across ECs, VSMCs, and other vascular compartments. Yet, the mechanistic dissection of these differences is limited. Species differences, supraphysiologic drug concentrations, short exposure durations, and model-specific triggers, such as toxin-induced injury or high-fat diets, limit the generalizability of these results to clinical populations [140–142]. Consequently, the proposition that anti-infective drugs modulate human vascular aging trajectories remains biologically plausible but not yet conclusively demonstrated. Human studies included in this review typically relied on surrogate cardiometabolic or inflammatory markers rather than direct vascular-aging endpoints.

Fluoroquinolones, for example, show direct mitochondrial toxicity characterized by inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation, increased ROS production, mtDNA destabilization, and impaired mitophagy in human endothelial and mammalian cells. Aminoglycosides similarly induce oxidative injury, mitochondrial swelling, and apoptotic signaling in vascular and renal tissues [143]. These findings provide strong mechanistic anchors for their pro-aging classification. In contrast, microbiome-mediated pathways, such as antibiotic-induced loss of SCFA-producing species (Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Akkermansia muciniphila) and expansion of TMA- and LPS-producing taxa (Proteobacteria, Bacteroides fragilis), are supported by correlative human and mechanistic animal data but lack interventional human studies that directly link antibiotic-driven dysbiosis to measurable vascular aging outcomes. Similarly, although tetracyclines demonstrate robust inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9, reduction of oxidative stress, and stabilization of ECM architecture in preclinical systems, their direct anti-senescent or vasculoprotective effects in humans remain unproven. Macrolides exhibit apparent anti-inflammatory effects, including suppression of IL-6, IL-8, and NF-κB signaling, yet their long-term effects on vascular aging trajectories remain unknown [135, 136]. Direct epigenetic or proteostasis evidence in vascular tissue is missing; current associations are inferred from non-vascular models. See Table 2.

Evidence-tier classification of anti-infective agents based on the strength, type, and translational relevance of available data across mechanistic, animal, and human studies.

| Tier | Evidence types | Examples of drug classes | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1: In vitro mechanistic evidence | Direct effects of ROS, mitochondrial potential, senescence markers, SASP | Fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, macrolides, tetracyclines | High mechanistic specificity | Non-physiologic doses; lacks systemic physiology |

| Tier 2: In vivo animal evidence | Effects on vascular inflammation, stiffness, mitochondrial injury, and ECM remodeling | Tetracyclines, macrolides, antiretrovirals | Enables causal inference | Species differences: acute or artificial disease models |

| Tier 3: Human observational evidence | Endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, inflammatory/metabolic shifts | Antiretrovirals, broad-spectrum antibiotics | Clinically meaningful | Confounding, heterogeneous endpoints; insufficient vascular-aging biomarkers |

ECM: extracellular matrix; ROS: reactive oxygen species; SASP: senescence-associated secretory phenotype.

Furthermore, the microbiome/vascular axis, which anti-infectious therapies may disrupt, is poorly understood. At the same time, dysbiosis is associated with systemic inflammation and vascular dysfunction; the precise microbial taxa and metabolites involved remain largely uncharacterized. Epigenetic modulation, potentially driven by SCFA depletion or NAD⁺ loss following anti-infectious exposure, is hypothesised but not directly demonstrated in vascular tissues. Furthermore, the impact of anti-infectious agents on proteostasis, particularly autophagic flux and proteasome function, within the context of vascular aging is underexplored, underscoring the need for integrative, mechanistically driven human studies. Nevertheless, alongside mechanistic deficiencies, many methodological and translational constraints impede a thorough comprehension of the impact of anti-infectious medicines on vascular ageing. Publication bias persists as research demonstrating the beneficial or novel effects of antibiotics is more frequently published, possibly distorting the evidence base. Experimental heterogeneity, encompassing variations in model systems, antibiotic doses, and endpoints, complicates cross-study comparisons and constrains repeatability. The majority of current research focuses on acute exposures, lacking longitudinal data to clarify the vascular long-term impact of chronic anti-infective use in humans. Equally, the duration, cumulative dose, and reversibility of antibiotic effects on vascular health remain poorly understood, particularly in aging populations with comorbidities.

In clinical settings, confounding variables, including comorbidities, polypharmacy, and the severity of underlying diseases, further complicate the causal links between anti-infective use and senescence-related outcomes. The richness and uniqueness of the gut microbiome pose considerable challenges; in the absence of an individualized microbial profile, it is arduous to generalize findings or discern consistent patterns linking microbiome disruption to vascular aging. Additionally, chronic or repeated antibiotic use is strongly associated with dysbiosis and increased cardiovascular risk in large human cohorts, likely mediated via microbiome-metabolite pathways such as TMAO and LPS. Furthermore, long-term exposure to macrolides or fluoroquinolones can cause off-target toxicities (e.g., QT prolongation, tendinopathy, mitochondrial injury) that may offset potential benefits in older, comorbid populations. Precautionary, any expansion of antibiotic use outside of infectious indications must be carefully weighed against the global threat of antimicrobial resistance, which is a major public health concern [139, 144].

Overcoming these restrictions is crucial for clinical applications. Furthermore, although risk-of-bias tools (SYRCLE, RoB-2, ROBINS-I, and narrative appraisal for in vitro) were applied, the predominance of preclinical studies and variability in outcome reporting limited standardization [145, 146]. Equally, no quantitative meta-analysis was feasible due to marked heterogeneity across study designs, drug classes, and outcome measures, and findings were therefore synthesized narratively. The number of high-quality human trials was relatively small compared to the preclinical evidence, limiting the generalizability of the conclusions.

Comprehensive research programs are required to enhance the understanding of the impact of anti-infectious medicines on vascular ageing and senescence, integrating mechanistic insights with translational applications. Clinical trials that include aging biomarkers, such as pulse wave velocity, endothelial function, and p16INK4a expression, should be prioritized to assess vascular effects in patients undergoing antibiotic treatment. High-throughput screening tools are crucial for categorizing antibiotics based on their senolytic, senomorphic, or senogenic characteristics across various vascular cell types, thereby facilitating tailored therapeutic approaches. Considering the impact of microbiome disruption on inflammaging, the co-administration of probiotics, prebiotics, or postbiotics merits examination as a strategy to restore microbial equilibrium and alleviate negative vascular consequences. Epigenetic mapping by methods such as ChIP-seq and methylation arrays can clarify antibiotic-induced alterations in chromatin and methylation within vascular tissues, providing mechanistic insight. Systems biology methodologies that integrate transcriptomic, metabolomic, and proteomic data will be essential for modeling antibiotic-senescence interactions and forecasting long-term vascular trajectories. Personalized senotherapy, guided by pharmacogenomic profiles and tailored microbiome data, has the potential to enhance antibiotic utilization in elderly populations. Ultimately, comparative analyses of macrolides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and aminoglycosides should be performed to delineate distinct ageing-modulatory profiles, thereby informing safer and more effective anti-infective prescribing strategies. We therefore advocate integrating ageing-modulatory profiles into antibiotic classification systems, enabling clinicians and researchers to anticipate vascular outcomes and design targeted interventions for age-related diseases.

An integrative conceptual framework mapping anti-infective agents to the dominant biological pathways they influence, mitochondrial integrity, oxidative stress, endothelial senescence, ECM remodeling, and microbiome-mediated inflammation could be proposed. Drugs with substantial mitochondrial toxicity (fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides) cluster toward pro-aging outcomes; drugs with anti-inflammatory or MMP-inhibitory activity (macrolides, tetracyclines) cluster toward neutral or potentially protective effects; and drugs that strongly disrupt microbial ecology (broad-spectrum antibiotics) align with microbiome-mediated inflammaging (Figure 4). This framework clarifies how drug-class characteristics translate into directional effects on vascular-aging biology and helps identify candidates for future mechanistic or clinical testing (see Table 3).

Risk-of-bias assessment of preclinical animal studies (murine and rat models) investigating antibiotics and vascular ageing.

| Ref # | Study type | Drug/Class | Model/Population | Tools used | Key bias domains (summary) | Overall risk | Ageing effects (biomarkers) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [63] | Animal | Doxycycline | ApoE−/−, ovariectomized mice | SYRCLE | Randomization not reported/unclear; no blinding; attrition not described | Some concerns | ↓ Aortic lesion area; ↓ MMP-2 activity; ↓ macrophage infiltration; modest ↑ eNOS (endothelial function) |