Affiliation:

Division of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, Department of Radiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, 27599 NC, USA

Email: hyeon_yu@med.unc.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4318-2575

Explor Dig Dis. 2026;5:1005109 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edd.2026.1005109

Received: November 20, 2025 Accepted: January 11, 2026 Published: January 18, 2026

Academic Editor: Han Moshage, University of Groningen, The Netherlands

The article belongs to the special issue Advances in Hepato-gastroenterology: Diagnosis, Prognostication, and Disease Stratification

Interventional radiology (IR) is an ideal domain for artificial intelligence (AI) due to its data-intensive nature. This review provides a targeted guide for clinicians on AI applications in liver interventions, specifically focusing on hepatocellular carcinoma and portal hypertension. Key findings from recent literature demonstrate that AI models achieve high accuracy in predicting the response to transarterial chemoembolization and in non-invasively estimating the hepatic venous pressure gradient. Furthermore, emerging deep learning architectures, such as Swin Transformers, are outperforming traditional mRECIST criteria in longitudinal treatment monitoring. Despite these technical successes, the transition from “code to bedside” is hindered by limited external validation and the “black box” nature of complex algorithms. We conclude that the future of IR lies in the “AI-augmented” interventional radiologist paradigm, in which AI serves as a precision tool for patient selection and procedural safety rather than as a replacement for clinical judgment.

Liver cancer is a global health challenge, with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) being its most common form, and its management is a cornerstone of modern interventional radiology (IR) practice [1, 2]. Similarly, portal hypertension (PHT), a major sequela of chronic liver disease, often requires complex, image-guided interventions, such as the placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) [3–5]. The treatment of these conditions has been revolutionized by a growing arsenal of minimally invasive procedures, including transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), radioembolization (TARE), thermal ablation, and portal vein embolization (PVE) [6–10].

The modern management of liver disease now generates an overwhelming amount of disparate data, from advanced multimodality imaging and radiomics to clinical, laboratory, and genomic information [11]. Managing this complex data to make personalized treatment decisions presents a significant challenge. Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a powerful tool to meet this challenge, and the field of IR is exceptionally well-suited for its application [12]. Unlike other interventional specialties, IR is an inherently data-rich field where entire image-guided procedures are recorded in a standardized digital format, creating an ideal ecosystem for AI-powered innovation [13]. This positions interventional radiologists not just as consumers of AI technology, but as potential leaders in developing groundbreaking tools for the entire interventional community [13].

In routine practice, interventionalists rely primarily on qualitative visual assessments of imaging and static staging systems, such as the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) criteria, to guide therapeutic decisions [14]. However, these conventional methods often fail to account for the complex biological micro-heterogeneity of liver tumors or the highly variable hemodynamics of PHT [15]. This leads to a “one-size-fits-all” approach in which, for example, up to 40% of patients may not achieve the predicted response to TACE or may develop unforeseen complications, such as overt hepatic encephalopathy (OHE) after TIPS placement [16–18]. AI offers a transformative solution to these shortcomings by extracting sub-visual “radiomic” features and processing multidimensional datasets that exceed human cognitive capacity, enabling a shift from generalized protocols to truly personalized medicine [15].

The path to clinical integration is not without obstacles. Advanced deep learning (DL) models require vast amounts of high-quality data, yet IR datasets are often smaller and less standardized than those in diagnostic radiology, influenced by operator variability, diverse patient conditions, and specific procedural contexts [19]. Furthermore, a lack of formal training in AI among clinicians can create a barrier to understanding, trusting, and effectively participating in the development and deployment of these powerful new tools [19, 20]. This gap is underscored by the fact that while the total number of FDA-cleared AI algorithms has surged to over 1,250, the share specifically dedicated to interventional procedures remains minimal, highlighting the specialty’s continuous unmet need for a clear roadmap from “code to bedside” [21].

The objective of this review is to offer a comprehensive guide for practicing interventional radiologists, bridging the gap between foundational AI concepts and their real-world clinical applications in the management of liver disease. We will first review a concise primer on essential AI terminology, frameworks, and life cycles. The core of the manuscript will then survey the current and emerging applications of AI in the management of HCC and PHT. Finally, we will discuss overarching challenges and outline the future of the field, guided by the research priorities established by major international IR societies [21, 22].

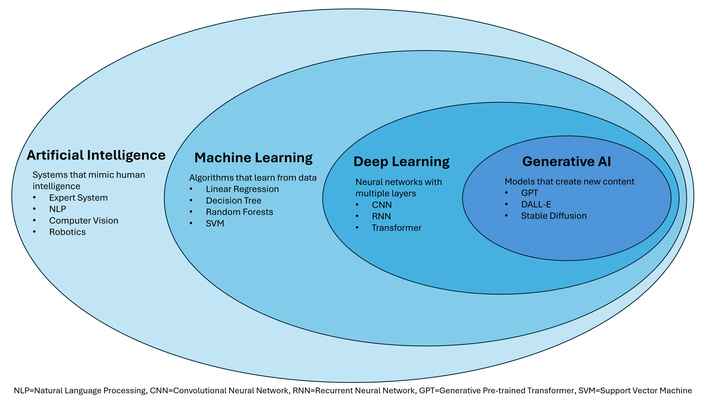

To critically evaluate and integrate AI into clinical practice, a foundational understanding of its core concepts is essential [20]. AI is a broad, umbrella term for computer-based systems that perform tasks requiring human-like intelligence, such as pattern recognition and problem-solving [11, 23]. Within this field, machine learning (ML) is a key subset where algorithms are not explicitly programmed but instead learn complex, non-linear relationships directly from data [11, 20]. DL is a further specialization of ML that uses advanced architectures, including artificial neural networks (ANNs) with many layers, to automatically extract and learn features from complex data (e.g., medical images) with minimal human intervention [11, 20, 24] (Figure 1).

The foundational hierarchy and examples of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, deep learning, and generative AI.

The way a model learns is defined by its training data. In supervised learning, the most common approach in medicine, the model is trained on a dataset where inputs are labeled with the correct outputs (e.g., CT images labeled with the presence or absence of PHT) [11, 20]. In contrast, unsupervised learning uses unlabeled data, and the model’s task is to find hidden patterns or relationships on its own [20]. There are two types of DL architecture particularly relevant to the interventional management of liver disease.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs): For years, CNNs have been the workhorse of medical imaging [11, 25]. Inspired by the human visual cortex, they are exceptionally good at processing grid-like data, such as images, to perform tasks including the classification and segmentation of liver tumors [23, 25–27].

Transformers: Originally developed for natural language processing (for example, the models behind ChatGPT), Transformers are now achieving state-of-the-art results in medical imaging [19, 28]. Architectures such as the Swin Transformer hierarchically capture both global and local features, making them highly effective for analyzing high-resolution, 3D medical images (e.g., CT and MRI scans) for tasks such as prognostic modeling in HCC [28–32].

Specific DL models, categorized by their interventional task—such as ProgSwin-UNETR for monitoring TACE response or the aHVPG Model for non-invasive pressure estimation—are detailed in Table 1.

Example deep learning models and their interventional relevance.

| Model name | Primary architecture/Type | Core clinical task | Relevant IR procedure/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProgSwin-UNETR | Swin Transformer/DL | Longitudinal prognosis stratification | Monitoring HCC response after TACE |

| aHVPG Model | AutoML/CNN | Non-invasive prediction of HVPG (pressure gradient) | PHT diagnosis; TIPS candidacy |

| Swin-UNETR | CNN/Transformer Hybrid | 3D segmentation of tumors and organs at risk | Y-90 dosimetry planning; ablation simulation |

| Neuro-Vascular Assist | Real-Time AI System | Real-time safety monitoring (detects migrating embolic agents) | Visceral or neuro-embolization |

| ChatGPT (GPT-4) | Large Language Model (LLM) | Statistical analysis and data interpretation | Accelerating clinical research and protocol design |

| K-Net/MobileViT | CNN/Transformer Hybrid (Dual-Stage) | High-accuracy segmentation and classification | Nodule/Lesion triage and feature analysis |

IR: interventional radiology; DL: deep learning; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; TACE: transarterial chemoembolization; ML: machine learning; CNN: convolutional neural network; HVPG: hepatic venous pressure gradient; PHT: portal hypertension; TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; AI: artificial intelligence.

A key process enabling AI in radiology is radiomics, which involves the high-throughput extraction of a large number of quantitative features from medical images [3, 13]. This process converts images into mineable data, capturing characteristics of tumor shape, intensity, and texture that are often imperceptible to the human eye [24, 25]. This is particularly well-suited for characterizing the heterogeneity of HCC from CT and MRI scans [24]. These radiomic features can then be fed into ML models to build tools that predict diagnosis, treatment response, or prognosis [1, 13, 24].

To help clinicians better understand and evaluate different AI tools, several classification frameworks have been proposed. One pragmatic approach categorizes AI systems based on their complexity and interpretability, distinguishing between simple, fully explainable models and complex, non-interpretable black-box models that require more scrutiny [20]. More recently, specific frameworks were developed to score the level of technological integration for robotic and navigation systems [33, 34]. These include the Levels of Autonomy in Surgical Robotics (LASR) scale, which rates a system’s ability to act independently, and the novel Levels of Integration of Advanced Imaging and AI (LIAI2) scale, which assesses how deeply AI is embedded into the procedural workflow [33, 35]. As will be discussed, a systematic review of currently available systems in IR found that most remain at a low level on both of these scales [33] (Table 2).

Levels of autonomy (LASR) and AI integration (LIAI2) classification scales.

| Scale | Purpose | Range | Core concept at the highest level |

|---|---|---|---|

| LASR (autonomy) | Classifies the robot’s degree of independence from human control | 0 (no autonomy) to 5 (full autonomy) | Full autonomy: The system performs the entire procedure based on predefined objectives without human intervention. |

| LIAI2 (integration) | Classifies the sophistication and depth of integration of AI and advanced imaging within the workflow | 1 (guided assistance) to 5 (full autonomous navigation) | Full autonomous navigation: The system fully integrates advanced imaging and AI to independently perform and navigate the intervention. |

AI: artificial intelligence; LASR: Levels of Autonomy in Surgical Robotics; LIAI2: Levels of Integration of Advanced Imaging and AI.

The process of building and implementing an AI model follows a rigorous, multi-stage lifecycle (Table 3). For interventional radiologists, understanding this pipeline—from initial data acquisition to final deployment—is essential for interpreting research and ensuring clinical relevance.

The AI project lifecycle: from data to clinical deployment.

| Stage | Key steps | Activities | IR relevance and goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conception & Data | Define problem | Identify a clear clinical question (e.g., predicting TACE response) | The goal is to obtain sufficient, high-quality data despite scarcity challenges in IR |

| Acquisition | Gather multimodal data, including imaging, labs, and clinical records | ||

| Preprocessing & Curation | Labeling | Assign a “ground truth” to the data (e.g., manual tumor segmentation or classifying patient outcome | Clinician expertise is required to perform accurate labeling and to ensure features reflect meaningful pathology |

| Feature extraction | Transform images into quantitative data (e.g., radiomic features from HCC texture) | ||

| Validation & Testing | Split data | Separate the dataset into training, validation, and untouched testing sets | This stage establishes rigor: models must prove accuracy on unseen patients to be considered trustworthy for clinical decision-making |

| External validation | Test the final model on data from a different center to prove generalizability | ||

| Mitigate overfitting | Ensure the model performs well on new data and does not fail due to over-memorization | ||

| Deployment & Integration | Evaluation | Quantify performance using clinical metrics such as AUC, sensitivity, and specificity | The goal is to achieve genuine clinical benefit by overcoming practical barriers and securing clinician trust before routine use |

| Workflow integration | Ensure the tool fits seamlessly into the IR suite and minimizes disruption to existing protocols |

AI: artificial intelligence; TACE: transarterial chemoembolization; IR: interventional radiology; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; AUC: Area Under the Curve.

The life of an AI model begins with defining a clinically relevant problem (e.g., predicting TACE non-response) and identifying the necessary data inputs. In IR, this involves synthesizing multimodal data, including imaging, laboratory values, and clinical records, which is critical given IR’s inherent multimodal nature [11]. The goal is to develop instruments for image segmentation, simulation, registration, and multimodality image fusion [21]. Given that IR datasets are often limited, acquiring high-quality, ethically sourced data is the primary logistical hurdle [19, 36].

Once acquired, raw data must be preprocessed. This crucial step includes image registration, normalization, and labeling. For supervised models, labeling is the labor-intensive process of assigning a ground truth to the input data (e.g., manually segmenting a tumor or labeling a patient as a one-hot encoding responder) [11]. This labeling often requires the expertise of interventional radiologists [37]. Preprocessing also involves feature extraction, transforming images into quantitative radiomics data. Radiomic features capture characteristics of tumor shape, intensity, and texture that are often imperceptible to the human eye, particularly in HCC [1].

The available dataset is split into three distinct sets to ensure robust evaluation. The training set is used to adjust the model’s internal parameters (weights) iteratively. The validation set is used during training to fine-tune model hyperparameters and prevent overfitting (when the model memorizes the training data but fails to generalize). The testing set is a portion of the original data kept entirely separate and used only once, at the end, to assess final real-world performance. Crucially, modern high-quality research also requires external validation—testing the model on data collected from a different institution or population to confirm generalizability. Studies that fail to perform external validation risk a significant drop in accuracy in clinical practice, a phenomenon known as overfitting, in which a model performs well on its training data but fails on new, unseen data.

Model performance is quantified using key metrics relevant to clinical risk, such as the Area Under the Curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. However, the process does not end with high metrics. The final stage is deployment—the envisioned pathway from a lab algorithm to routine clinical use. This requires mitigating ethical biases and ensuring the AI tool seamlessly integrates into existing workflows, minimizing disruption to the IR suite [37]. Deployment is the ultimate safeguard for determining whether the AI tool can provide a genuine clinical benefit.

AI demonstrates significant potential across the full spectrum of interventional liver disease management. Current research and early clinical applications can be organized by the primary clinical problems they aim to solve: managing HCC, assessing and treating PHT, and optimizing patients for surgical resection (Table 4).

AI applications in liver interventions: from routine shortcomings to AI solutions.

| Phase | Clinical application | Conventional method | AI methodology | AI advantage | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-procedural | Predicting TACE response | Visual CT/MRI & BCLC staging. High inter-observer variability; fails to capture sub-visual tumor heterogeneity. | Multimodal models using radiomics, DL, and clinical data (ALBI, BCLC, AFP). | AUROC > 0.85. Improves patient selection and avoids futile procedures. | [6, 28, 37, 38] |

| Non-invasive PHT assessment | Invasive HVPG measurement. Procedural risk and requirement for highly specialized expertise. | Radiomics and DL models (e.g., aHVPG) are analyzing CT features of the liver and spleen. | Non-invasively estimate HVPG to stratify risk and guide TIPS candidacy. | [1, 4, 53] | |

| Predicting post-TIPS complications | Clinical scores (MELD, Child-Pugh). Limited predictive power for post-TIPS OHE. | Radiomics, ANNs, and various ML models. | Accurately forecast the risk of OHE for counseling. | [3, 4] | |

| Predicting PVE success | 2D/3D CT volumetry. Volume does not always equal function; difficult to predict actual hypertrophy kinetics. | Multimodal models using Statistical Shape Models to quantify 3D liver anatomy. | Forecast FLR hypertrophy to optimize surgical planning. | [7] | |

| Intra-procedural | Treatment simulation | Standard anatomical landmarks. Fails to account for heat-sink effects or perfusion-based boundaries. | DL models to predict ablation zones and simulate Y-90 radioembolization dosimetry. | Optimize probe placement and increase quantitative accuracy of dosimetry. | [24, 39–41] |

| Image quality improvement | Conventional imaging filters. High radiation dose or poor visualization due to artifacts. | DLR for dose reduction; DL to reduce metal artifacts or generate synthetic DSA. | Lower radiation dose; improve visualization and safety during procedures. | [19, 24, 47] | |

| Post-procedural | Longitudinal monitoring of HCC | mRECIST criteria. Does not account for dynamic metabolic changes or internal necrosis patterns. | DL (Transformers) using multi-time-point MRI data to track tumor changes. | More accurate prognostic stratification than diameter-based criteria. | [28] |

| Detecting tumor recurrence | Manual surveillance review. Potential for human error in identifying subtle early progression. | ML, radiomics, and CNNs. | Automated and early detection of LTP after ablation. | [24, 46] |

AI: artificial intelligence; TACE: transarterial chemoembolization; BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; DL: deep learning; ALBI: albumin-bilirubin; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; AUROC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; PHT: portal hypertension; HVPG: hepatic venous pressure gradient; TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; MELD: model for end-stage liver disease; OHE: overt hepatic encephalopathy; ANNs: artificial neural networks; ML: machine learning; FLR: future liver remnant; Y-90: Yttrium-90; DLR: DL reconstruction; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; mRECIST: Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; CNNs: convolutional neural networks; LTP: local tumor progression.

As a primary focus of interventional oncology, HCC has become a key use case for AI development, with a particular emphasis on predicting patient response to locoregional therapies [21].

TACE is a cornerstone therapy for intermediate-stage HCC, but patient response is highly variable [6, 37]. Consequently, the most studied application of AI in interventional oncology is the development of models to predict which patients will benefit from TACE before the procedure is performed [24, 37]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that these AI models demonstrate strong predictive performance. One meta-analysis of 11 studies found that AI models achieved high pooled area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUROC) values of 0.89 on internal validation and 0.81 on external validation, confirming their robustness [38].

A consistent theme is that multimodal models that integrate different data types yield the best results. Systematic reviews involving 23 studies with 4,486 patients have found that models combining clinical variables [including albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade, BCLC stage, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level] with radiologic features (including tumor diameter, distribution, and peritumoral arterial enhancement) achieve higher predictive performance than models using clinical or imaging features alone [6, 37]. However, a recent meta-analysis added nuance, finding no statistically significant performance difference between advanced DL models and traditional handcrafted radiomics (HCR) models, nor between models with and without added clinical data [38]. The authors suggested that AI models may be able to implicitly learn clinical information directly from imaging data [38].

AI is also advancing beyond static, single-time-point assessments to perform longitudinal analysis that tracks tumor changes over time. A state-of-the-art study by Yao et al. [28] developed a DL model, ProgSwin-UNETR, to predict the long-term prognosis of HCC patients by analyzing a series of arterial-phase MRI scans taken at three different time points: before treatment, after the first TACE, and after the second TACE. By learning from these dynamic changes, the model stratified patients into four distinct risk groups with high accuracy (AUC of 0.92) and significantly outperformed both traditional radiomics models and the standard Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) criteria in predicting patient survival [28].

Beyond TACE, AI tools are being developed for other liver-directed therapies.

AI for Y-90 dosimetry and planning: Segmentation of organs at risk and tumors is a critical, labor-intensive step in Y-90 TARE dosimetry planning. CNNs have been successfully developed for the automated segmentation of lungs, liver, and tumors on Tc-99m MAA SPECT/CT images, drastically reducing operator time [39]. AI is also being used to improve the technical accuracy of the dosimetry itself. A DL framework that employs CNNs for scatter correction and absorbed dose-rate estimation was developed to mitigate the impact of poor image quality from bremsstrahlung SPECT. This model was found to outperform the conventional Monte Carlo (MC) dosimetry method in virtual patient studies by 66% in Normalized Mean Absolute Error (NMAE), offering faster computation and higher accuracy [40]. Crucially, advanced AI tools that incorporate multimodal data are necessary because standard anatomical segmentation is insufficient for Y-90 TARE planning. Using contrast-enhanced Cone-Beam CT (CBCT) to define liver perfusion territories (LPTs), one study found that using standard anatomical landmarks instead of perfusion-based boundaries could lead to dosimetric errors of up to 21 Gy in the left liver lobe, highlighting the critical value of AI-assisted image registration and segmentation of functional territories [41].

Treatment simulation and image quality: For thermal ablation, AI-driven treatment simulation models can predict the size and shape of an ablation zone before the procedure, accounting for real-world factors such as the heat-sink effect from nearby blood vessels [24, 42, 43]. For radioembolization, AI can be used to automate the segmentation of the liver and tumors on planning scans for dosimetry and to simulate the biodistribution of Y-90 microspheres [24, 39–41, 44]. For follow-up, AI models are demonstrating high accuracy (AUC up to 0.99) in detecting local tumor progression (LTP) on surveillance CT scans after thermal ablation [24, 45, 46].

Image quality improvement: AI enhances the quality of the images that guide interventions. DL reconstruction (DLR) algorithms reduce image noise and enable significant reductions in radiation dose during CT-guided procedures while maintaining image quality [24, 47]. Another application involves DL models that generate high-quality, artifact-free synthetic digital subtraction angiography (DSA) images for abdominal angiography, overcoming motion-related misregistration and potentially reducing radiation exposure [19, 24, 47].

Dynamic video analysis and real-time AI: While most current AI applications in IR rely on static pre-procedural imaging, significant progress involves the analysis of dynamic, video-based data generated during fluoroscopy and angiography. Unlike static CT or MRI, procedural video requires AI models capable of temporal reasoning—understanding how structures or tools move over time. Methodologies developed in adjacent fields, such as real-time polyp detection in colonoscopy, provide a valuable roadmap for IR [48–50]. In gastroenterology, DL models (e.g., CNNs combined with temporal filtering) have reached high levels of accuracy in identifying lesions on live video feeds, reducing “miss rates” significantly. Transferring these approaches to IR could enable real-time “computer-aided detection” of subtle findings, such as the early detection of liquid embolic migration or the automated tracking of catheter tips during complex navigation [51, 52]. Such tools could shift the role of AI from a pre-procedural planning aid to an active, “over-the-shoulder” safety monitor during live interventions.

AI is developing powerful, non-invasive tools to assist in diagnosing and managing PHT and its complications.

Non-invasive diagnosis and risk stratification: The gold standard for assessing the severity of PHT is the invasive measurement of the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) [4, 53]. To overcome this, an automated AI model (aHVPG) was developed that uses radiomics from CT scans of the liver and spleen to accurately estimate the HVPG, significantly outperforming conventional non-invasive tools [53]. Another multimodal model combined clinical data (portal vein diameter, Child-Pugh score) with radiomic and DL features extracted from the non-tumorous liver parenchyma to predict the presence of PHT [1].

Predicting post-TIPS complications: For patients undergoing TIPS, a major concern is the risk of post-procedural OHE. Several AI approaches—including CT-based radiomics, ANNs, and other ML models—have been successfully used to predict the risk of post-TIPS OHE, with models consistently achieving high AUROCs greater than 0.80 [3, 4].

AI is also being applied to PVE, a critical IR procedure performed to induce hypertrophy of the future liver remnant (FLR) before a major hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases [7]. The success of the subsequent surgery depends on achieving adequate liver growth. A recent state-of-the-art, multicenter study developed an ML model to predict post-PVE outcomes, including the final FLR percentage [7]. This study is a benchmark for advanced AI methodology, as it integrated multimodal data (clinical, laboratory, and radiomic features) and introduced a novel Statistical Shape Model to mathematically quantify the 3D shape of the liver as a predictive feature. Critically, the study validated its model on an external dataset from a separate institution, demonstrating strong generalizability and addressing a common limitation in AI research [7].

Beyond oncology and PHT, AI is increasingly relevant in the management of biliary obstructive diseases and metabolic liver conditions. In biliary interventions, DL models, such as CNNs, are being developed to assist in the automated mapping of the biliary tree from magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) [54]. These tools can accurately detect common bile duct stones (90.5%) and distinguish between benign and malignant biliary strictures with high sensitivity (82.4%), potentially guiding complex interventions, such as percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), by reducing the reliance on extensive ductal opacification on fluoroscopy [54, 55]. Furthermore, novel augmented reality (AR) navigation systems are emerging that automatically register the biliary anatomy to 3D CT coordinates, allowing for precise real-time tracking of interventional instrument tips during biliary procedures [56].

In the context of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD), AI-powered ultrasound and CT tools now facilitate the non-invasive quantification of liver fat and fibrosis [57]. DL algorithms applied to non-enhanced CT scans can automatically measure liver attenuation and convert it to a fat fraction, achieving high correlation with manual measurements and traditional MRI-PDFF (r2 = 0.92) [58]. This capability is critical for IR when assessing procedural safety; for instance, quantifying the degree of steatosis or fibrosis in the non-tumorous liver is essential for predicting the risk of post-embolization liver failure or evaluating the quality of the FLR after PVE [57, 58].

The integration of AI into the interventional management of liver disease is rapidly moving from a theoretical possibility to a clinical reality. The evidence demonstrates that AI is poised to enhance every phase of the IR workflow. In the pre-procedural phase, AI models are showing robust performance in predicting treatment outcomes for core liver-directed procedures, including TACE and TIPS [3, 6]. Intra-procedurally, advanced imaging techniques are reducing radiation dose and improving image quality [24, 46]. Post-procedurally, AI automates the labor-intensive tasks of surveillance and follow-up, offering a level of consistency that can surpass human performance [59]. However, the path from a promising algorithm to a fully integrated and trusted clinical tool is paved with significant challenges (Table 5).

Key challenges and future directions for AI in liver interventions.

| Category | Key points | Description | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges | Data-related hurdles | Scarcity of large, high-quality, and standardized IR datasets.“Garbage in, garbage out”: poor image quality leads to AI failure.Ethical issues surrounding data privacy, ownership, and security. | [19, 23, 36, 59, 60] |

| Methodological barriers | The “black box” problem and the need for explainable AI (XAI).Lack of external validation, leading to overfitting.High heterogeneity across studies makes comparing results difficult. | [1, 20, 23, 28, 37, 38, 61, 62] | |

| Clinical & ethical dilemmas | Risk of amplifying existing societal biases (algorithmic bias).Unclear accountability for AI-related adverse events.Difficulty with practical workflow integration.Risk of “futile technologization” (expensive tech with marginal benefit). | [19, 35, 37, 60] | |

| Future directions | A guided research agenda | The SIR Foundation has prioritized HCC as a key use case.Immediate research needs include tools for segmentation, simulation, and navigation.A top priority is creating shared data commons to accelerate research. | [21] |

| Emerging technologies | Shift toward powerful, adaptable foundation models.Use of generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT) as a research tool.Creation of “synthetic cohorts” to serve as control arms in clinical trials. | [19, 20, 64] | |

| Ensuring quality & trust | Widespread adoption of standardized reporting guidelines, such as the iCARE checklist, is essential to ensure future research is reproducible, transparent, and trustworthy. | [19, 63] |

AI: artificial intelligence; IR: interventional radiology; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; iCARE: Interventional Radiology Reporting Standards and Checklist for Artificial Intelligence Research Evaluation.

The performance of any AI model is fundamentally dependent on the data used to train it. A primary challenge in IR is the relative scarcity of large, high-quality, and standardized datasets compared to diagnostic radiology, which can limit the development of robust models [19, 36]. This is compounded by the “garbage in, garbage out” principle; AI models can fail if the input data is of poor quality, as demonstrated in studies where data heterogeneity and quality issues are a primary concern [36].

Furthermore, the use of patient data raises profound ethical questions about data privacy, ownership, and security [23, 60]. A proposed framework suggests treating de-identified patient data for secondary research as a “public good” that can be shared to advance medicine but not sold for profit, a concept that requires broad consensus and strong governance to implement [60].

A common concern among clinicians is the “black box” nature of many DL models, where the reasoning behind a prediction is not easily understood [20, 23]. This lack of interpretability can be a major barrier to clinical trust. Consequently, a key area of modern AI research is explainable AI (XAI), which aims to open this black box and provide insights into the model’s decision-making process [61]. Techniques such as Grad-CAM++, which generate heatmaps to visualize the image regions an AI is focusing on, are a practical example of XAI in action [28].

The field is also challenged by a lack of methodological rigor. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found significant heterogeneity across studies, with different research groups using varied algorithms and datasets, making it difficult to compare results directly [38, 62]. Many studies are single-center and lack external validation, raising questions about their generalizability and sometimes leading to overfitting, where a model performs well on its training data but fails on new, unseen data [1, 37].

Beyond the data and methods, several ethical and practical issues must be addressed.

Algorithmic bias: AI models trained on historical healthcare data can inadvertently learn and amplify existing societal biases related to race, socioeconomic status, or geography, potentially worsening healthcare disparities [19, 60]. For example, an AI trained on data where disadvantaged patients have worse outcomes might learn to recommend against treating them [60].

Accountability for errors: A critical question is who is responsible when an AI-related adverse event occurs. A reasonable framework approaches this similarly to medical device litigation, where fault could lie with the developer for a flawed product or with the clinician for its improper use [60].

Workflow integration: Many AI tools developed in a research setting are difficult to integrate into complex clinical workflows. Cumbersome requirements, such as the need for manual tumor segmentation before a model can be used, are a major barrier to practical adoption [37].

Futile technologization: Finally, there is a risk of developing expensive, sophisticated technologies that provide only marginal clinical benefit, a phenomenon termed “futile technologization” [35]. Experts caution that innovation must be rigorously evaluated to ensure it is driven by clinical relevance and improves patient outcomes, rather than by commercial pressure [35].

The findings of this narrative review underscore a pivotal shift in the interventional management of liver disease. Traditional clinical decision-making relies on a diverse yet often subjective set of data modalities that are frequently prone to inter-observer variability and high cognitive load [23]. The integration of AI, particularly DL and radiomics, represents a paradigm shift from qualitative visual assessments to a quantitative, data-driven approach that extracts diagnostic and prognostic information often imperceptible to the human eye [15, 24].

In the management of HCC, AI models have demonstrated an ability to stratify patient risk with an accuracy that matches or, in some cases, surpasses that of expert radiologists, particularly in predicting response to locoregional therapies, such as TACE [6, 38]. Similarly, the development of non-invasive tools for PHT assessment addresses a critical clinical need by providing support for early intervention and personalized treatment strategies without the risks associated with invasive HVPG measurement [4, 53]. Beyond oncology and cirrhosis, the emerging use of AI in biliary obstructive diseases and automated fatty liver quantification further broadens the scope of the “AI-augmented” interventionalist, allowing for more precise procedural guidance and comprehensive risk assessment [54, 55].

The clinical impact of these tools lies in their potential to standardize diagnostic quality and optimize outcomes [13]. While currently most advanced in diagnostic and post-processing tasks, interventional applications are beginning to mature, offering measurable gains in catheter navigation, probe placement, and ablation success [33, 52].

Despite the transformative potential of AI in hepatology and IR, several significant hurdles remain that impede its widespread clinical adoption (Table 5).

Methodological and data barriers: Most current AI research is retrospective and limited by small, single-center datasets, which raises concerns regarding the generalizability and robustness of models across different clinical environments [19, 36].

Interpretability and trust: The “black box” nature of complex DL architectures erodes clinician trust, as the rationale behind AI-generated recommendations is often opaque [20, 61].

Workflow integration: Practical implementation faces logistical hurdles, including the need for institutional support, interoperability with existing electronic health records, and clinician training [22, 37].

Ethical and regulatory issues: Algorithmic bias, data privacy concerns, and the lack of clear legal liability frameworks for AI-driven errors remain critical issues needing resolution [19, 60].

Moving forward, the field must be guided by the research priorities established by the SIR Foundation Research Consensus Panel, which emphasized the creation of “shared data commons” and prioritized HCC as the primary use case for personalized, AI-driven algorithms [21]. Future research must prioritize multicenter, prospective validation and the development of XAI to improve model transparency [28, 63]. Technological paradigms are already shifting toward foundation models and generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT) to accelerate clinical research and statistical analysis [20, 64]. Furthermore, innovative concepts such as “synthetic cohorts” of virtual patients may soon mitigate the difficulties of clinical trial recruitment [19]. Ultimately, the successful and responsible integration of AI will depend on the adoption of standardized reporting guidelines, such as the Interventional Radiology Reporting Standards and Checklist for Artificial Intelligence Research Evaluation (iCARE) checklist, to ensure future research is reproducible and trustworthy [19, 63].

AI is no longer a futuristic concept, but an active force poised to revolutionize the interventional management of liver disease. By extracting sub-visual radiomic features and processing complex datasets, AI provides a measurable advantage over routine qualitative methods in predicting TACE response, non-invasively assessing PHT, and forecasting surgical outcomes. However, the transition from “code to bedside” requires the IR community to lead efforts in data standardization and methodological rigor. AI will not replace the interventionalist but will instead create an “AI-augmented” paradigm, where clinicians are empowered by precision tools to deliver safer, personalized, and more effective care for patients with liver disease.

AI: artificial intelligence

ANNs: artificial neural networks

AUC: Area Under the Curve

AUROC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

CNNs: convolutional neural networks

DL: deep learning

FLR: future liver remnant

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma

HVPG: hepatic venous pressure gradient

IR: interventional radiology

ML: machine learning

OHE: overt hepatic encephalopathy

PHT: portal hypertension

PVE: portal vein embolization

TACE: transarterial chemoembolization

TARE: transarterial radioembolization

TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

XAI: explainable artificial intelligence

HY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. The author read and approved the submitted version.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest or competing financial interests to disclose.

As this is a narrative review of previously published literature and does not involve original human or animal research, ethical approval from an Institutional Review Board (IRB) was not required.

Not applicable.

Not applicable; this manuscript does not contain individual patient data or identifying information.

No new datasets were generated or analyzed during the preparation of this narrative review. All information presented is derived from cited, publicly available literature.

No external funding was received for this study.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 883

Download: 23

Times Cited: 0

Amedeo Lonardo

Amar Tebaibia ... Nadia Oumnia

Cristina Felicani ... Pietro Andreone

Rudy El Asmar ... Samer AlMasri

Ralf Weiskirchen

Vincenzo Giorgio Mirante