Affiliation:

1Department of Nutritional Sciences, Molecular Nutritional Science, University of Vienna, A-1090 Vienna, Austria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3356-4115

Affiliation:

2Department of Liver and Digestive Diseases, Groupe Hospitalier Public du Sud de l’Oise, 60100 Creil, France

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8442-4526

Affiliation:

3Qidong Liver Cancer Institute, Qidong 226200, Jiangsu, China

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4102-8934

Affiliation:

4Department of Pharmacology, Toxicology & Therapeutics, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3167-5073

Affiliation:

5Center for Cancer Research, Medical University of Vienna, A-1090 Vienna, Austria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6074-7144

Affiliation:

6Department of Molecular and Cellular Medicine, Institute of Biomedical Research of Barcelona (IIBB), CSIC, 08036 Barcelona, Spain

7Liver Unit, Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona, Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Spain

8Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red (CIBEREHD), 28029 Madrid, Spain

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2652-6102

Affiliation:

4Department of Pharmacology, Toxicology & Therapeutics, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8695-6980

Affiliation:

9Department of Medical Imaging, Groupe Hospitalier Public du Sud de l’Oise, 60100 Creil, France

Affiliation:

10Department of Internal Medicine, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena, 41100 Modena, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9886-0698

Affiliation:

11Biosciences Institute, University of Newcastle, NE2 4HH Newcastle, United Kingdom

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0950-243X

Affiliation:

12Liver Research Unit, Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation, Mexico City 14050, Mexico

13Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City 04360, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5257-8048

Affiliation:

14Department of Laboratory, Groupe Hospitalier Public du Sud de l’Oise, 60100 Creil, France

Affiliation:

15Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, 9713 GZ Groningen, The Netherlands

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4764-0246

Affiliation:

16Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, 50134 Florence, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2473-3535

Affiliation:

17Research Laboratory in Translational Gastroenterology, University Hospital Aachen, 52074 Aachen, Germany

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7122-6379

Affiliation:

18Institute of Biochemistry, Food Science and Nutrition, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot 7610001, Israel

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5407-0440

Affiliation:

2Department of Liver and Digestive Diseases, Groupe Hospitalier Public du Sud de l’Oise, 60100 Creil, France

Affiliation:

6Department of Molecular and Cellular Medicine, Institute of Biomedical Research of Barcelona (IIBB), CSIC, 08036 Barcelona, Spain

7Liver Unit, Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona, Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Spain

8Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red (CIBEREHD), 28029 Madrid, Spain

19Department of Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033, USA

Email: checa229@yahoo.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3422-2990

Explor Dig Dis. 2026;5:1005110 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edd.2026.1005110

Received: November 28, 2025 Accepted: January 18, 2026 Published: February 09, 2026

Academic Editor: Jae Youl Cho, Sungkyunkwan University, South Korea

Digestive diseases comprise a diverse range of illnesses, which are prevalent worldwide and represent an important health issue. This is particularly relevant for the impact of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) due to its close association with the obesity pandemic, contributing to the escalation of MASLD as the most common form of chronic liver disease, and the main cause of liver cancer. Not only does MASLD reflect the deterioration of liver health, but it also has far-reaching consequences for the development of extrahepatic digestive diseases. Along with the progression of liver and digestive diseases to liver, colorectal and pancreatic cancer, the onset of inflammation in diseases of the digestive tract, drug-induced liver injury, and cholestasis, drives and contributes to the rise of these diseases in the future, which merit the attention of clinical and translational research to increase our understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying these disorders in order to improve the diagnosis, management, and treatment. With this goal in mind, the current collaborative review gathers experts in a wide range of liver and digestive diseases to provide an up-to-date overview of the mechanisms of disease and identify novel strategies for the improvement of these important health issues.

Digestive diseases are very common worldwide and account for considerable health care use and represent a high social impact and economic burden to Western countries. Since 2000, the increase in diseases of the digestive tract has been exponential and alarming. Approximately 40% of the adult global population is estimated to suffer from gastrointestinal disorders, which implies a serious economic impact and significant social cost. A substantial disparity in the burden of digestive diseases exists among countries with different developmental levels. A recent study has shown that in the US, the digestive disease burden has escalated, with higher rates of mortality in men versus women, especially higher in Blacks compared to Whites, while Hispanics show lower rates [1]. In a recent report from the United European Gastroenterology, more than 350 million people are believed to live with digestive disorders in Europe, with higher burdens in central and eastern Europe than in western and southern European countries. Although limited data is available for low to middle-income countries, the 2019 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study [2] provides a comprehensive overview to understand the state of digestive diseases.

Epidemiological studies show that the main risk factors for digestive diseases are the use of alcohol or drugs, smoking, and high body mass index. In fact, obesity is a major driver of digestive diseases, including metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), causing an increased burden of associated digestive disorders, such as gastrointestinal, kidney, and cardiovascular events, with poor prognosis and low survival rates of patients with obesity-associated cancers.

The cost of billions of US dollars associated with gastrointestinal health is not the worst scenario of the impact of the disease in society, but rather this spectrum of diseases extends beyond the financial and physical burden on patients, health care professionals, and the overall healthcare system. In order to reverse these alarming trends, there is an urgent need to address these burdens through basic, clinical, and epidemiological research, as well as health education of populations with digestive disorders to avoid poor lifestyles and prolong survival time.

In this collaborative, expert-driven review, we summarize the most common forms of digestive diseases, from chronic liver disease to gastrointestinal disorders, and provide insightful suggestions for future developments for the design of strategies aimed at preventing the onset of these diseases and providing a more efficient treatment for the public health concern related to liver and digestive diseases.

The historical definition of NAFLD, created in the 1980s, was widely used until 2022 [3] when Eslam turned the negative definition (i.e., nonalcoholic) into a positive diagnostic criterion: MAFLD [4]. This development was continued in 2023, when a novel definition was coined: MASLD, which requires concurrent steatosis and at least one cardio-metabolic criterion [5]. This effort also accounts for the patients with MASLD, who consume moderate amounts of alcohol. This condition is termed metabolic dysfunction-associated alcohol-related liver disease (MetALD) [6].

Several scholars have highlighted the limitations of the MASLD [7, 8] and MetALD definitions [9] while supporting head-to-head comparative studies [10]. When comparisons have been made, they often suggested that MAFLD may more selectively identify patient populations at risk of severe liver-related and extra-hepatic outcomes [11]. Conversely, MASLD is more inclusive and captures larger strata of patients [11].

MASLD affects 38% of adults and up to 14% of children and adolescents, and the prevalence rate in adults is projected to exceed 55% by 2040 [12]. Groups at high risk of MASLD comprise those with obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), and other features of the metabolic syndrome [13]. The fact that MASLD often develops secondary to specific endocrinopathies is increasingly being recognized [14].

MASLD is modified by gender and hormonal status. It is more common in men than in premenopausal women while postmenopausal women’s MASLD rates are similar to men’s [15]. On the other hand, women have a higher risk of advanced fibrosis than men, especially after the age of 50 years [16].

Currently, in the US, MASLD is the leading indication for liver transplantation in women and subjects with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [12]. However, only a subset of subjects with MASLD will progress to advanced forms of liver disease, and the leading cause of mortality among MASLD patients is cardiovascular disease (CVD) [12]. Like other liver disease etiologies, surveillance for early detection of HCC is warranted among those with MASLD and advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, or portal hypertension [17].

Further to liver-related outcomes and to CVD, accumulating data suggest that MASLD may be associated with certain extra-hepatic cancers, such as those of the gastrointestinal tract and of the urinary system [18, 19]. The stage of liver fibrosis and gender modulate the risk of hepatic and extra-hepatic outcomes [20, 21]. A growing body of studies supports chronic kidney disease as another extra-hepatic outcome whose risk parallels the severity of MASLD [22]. The presence of both conditions also increases the risk of CVD [23].

Although Mendelian-randomization studies do not invariably support a cause-and-effect relationship between MASLD and these extra-hepatic outcomes [24, 25], clinicians should be aware of the risks of CVD and extra-hepatic cancers among those with MASLD as a part of a holistic approach to this systemic disorder [13, 26].

Hepatocytes are the central hub of lipid metabolism of the human body since they take up and secrete lipids into the bloodstream, carry out de novo lipogenesis as well as degrade lipids via β-oxidation. An imbalance in these pathways results in intrahepatic accumulation of neutral fat that becomes evident as steatosis [27] and can be detected histologically as well as by multiple imaging methods [28]. While ultrasound is most widely used in the clinical routine, magnetic resonance imaging with assessment of proton density fat fraction is the most accurate non-invasive method [28].

Unlike the adipose tissue, the liver is not physiologically devoted to the accumulation of fat and the accumulation of intrahepatic fat has the potential for triggering lipotoxic phenomena such as cell degeneration (i.e., ballooning) and cell death. The ongoing stress may trigger pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cascades and thereby lead to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), an advanced form of MASLD, and subsequently to MASH-fibrosis or MASH-cirrhosis [29]. MASLD results from an intricate organ crosstalk with adipose tissue and the intestinal tract playing key roles [30]. The former acts as a supplier of free fatty acids (FFAs) and of hormonal substances, such as leptin and adiponectin that affect the hepatocellular lipid handling [31]. The intestinal tract is tightly connected to the liver via portal circulation and both organs work closely in the digestion and handling of nutrients. However, MASLD patients often display an increased gut permeability and intestinal dysbiosis that leads to portal circulation of gut-derived toxins and hepatic inflammation [32].

Steatogenic and fibrotic progression of MASH are intimately and bi-directionally associated with insulin resistance (IR) in the context of systemic metabolic dysfunction in subjects with either features or the full-blown metabolic syndrome [33]. Additionally, age, sex, reproductive status, hormonal influxes, and lifestyle factors (diet, smoking, alcohol, physical exercise, sedentary behavior) are key modifiers of the distribution of body fat, of intrahepatic balance of pro- and anti-lipogenic, inflammatory, and profibrogenic pathways [34]. Notably, MASLD displays a strong heritable trait, and genetic studies shaped our understanding of MASLD pathogenesis [35]. On a population level, a variant in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) constitutes the strongest genetic contributor to MASLD and highlights the importance of lipid droplet handling within hepatocytes, which is supported by other MASLD-related variants such as MBOAT7 [35]. In particular, the PNPLA3 I148M seems to accumulate on lipid droplets and to impair their degradation [36]. However, genetic studies also highlight the complexity of the condition with processes like secretion of very low-density lipoproteins (TM6SF2, ERLIN1), lipogenesis (GCKR, ApoE), diversion of triglycerides (MTARC1), and many others being affected [35].

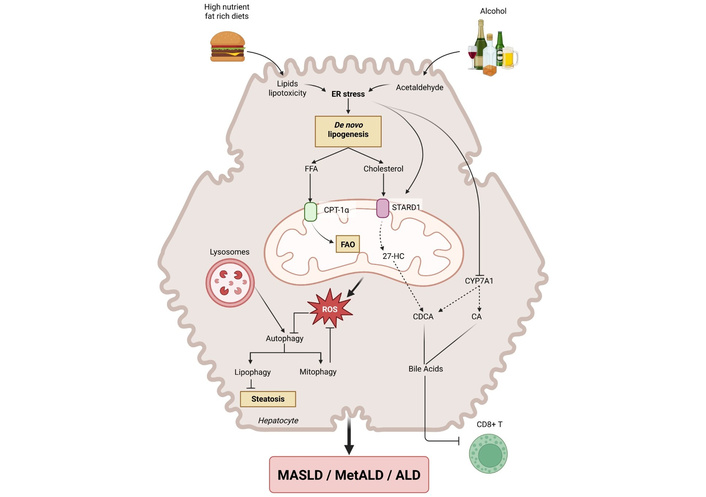

Bile acids (BAs), produced from cholesterol in hepatocytes, are involved not only in bile formation and fat digestion, but also serve as signaling molecules involved in metabolic processes such as lipid and glucose homeostasis [37, 38]. Disruption of BA homeostasis leads to the progression of MASLD and development of MASLD-HCC [39]. Recent studies have found that interleukin-1 receptor 1 (IL1R1), gut microbiota, and BA changes synergistically contribute to the development of MASLD [40], suggesting pathogenic cross-talks between BA metabolism, gut dysbiosis, and “metaflammation”, i.e., sterile metabolic inflammation, in MASH. BAs are elevated in MASLD, particularly ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), taurocholic acid (TCA), chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TCDCA), and glycocholic acid (GCA). However, BA profiles vary owing to geographic regions or disease severities [41]. Notably, TCA, TCDCA, taurolithocholic acids, and glycolithocholic acids exhibit a potential ability to identify MASH [41]. Trafficking of cholesterol to mitochondria through steroidogenic acute regulatory protein 1 (STARD1), the rate-limiting step in the alternative pathway of BA generation, not only promotes the progression from steatosis to MASH by sensitizing hepatocytes to inflammatory cytokines-induced cell injury [42] but also plays a key role in the pathogenesis of MASLD-HCC (Figure 1) [37]. This is particularly relevant for MASH and HCC development as the synthesis of BA through the classic pathway controlled by CYP7A1 is repressed by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Finally, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 21, a potent regulator of glucose and lipid homeostasis, acts as a negative regulator of BA synthesis [43], paving the way for targeted pharmacological interventions in MASLD/MASH arena, as discussed below. Another pathogenically and therapeutically relevant alteration in MASLD/MASH is dysfunctional farnesoid X receptor (FXR)-FGF19 feedback signaling. This leads to elevated BA production, higher pericentral biliary pressure, and pericentral micro-cholestasis that may account for raised GGT serum concentrations in a proportion of MASLD/MASH individuals [38, 44, 45].

Interplay of players involved in the progression of MASLD and ALD. Consumption of high-nutrient diets and alcohol converges in common mechanisms that synergize to induce the overall phenotypic changes of MASLD and ALD, as well as MetALD. The ingestion of dietary fats and the oxidative metabolism of ethanol alter ER inducing ER stress, which emerges as a critical trigger to cause increased de novo lipogenesis, including free fatty acids (FFAs) and cholesterol via activation of transcription factors SREBP1c and SREBP2, respectively, with the ultimate impact in the onset of hepatic steatosis. ER stress in turn induces STARD1 expression, which translocates cholesterol to the mitochondrial inner membrane for metabolism by CYP27A1 to generate the oxysterol 27-hydroxycholesterol that acts as the precursor of the primary bile acid, chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA). ER stress blocks the expression of CYP7A1, the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of bile acids through the classic pathway, causing the reprogramming of bile acid metabolism from the classic to the alternative pathway. Besides the stimulation of CDCA, the translocation of cholesterol to mitochondria impairs mitochondrial function and antioxidant defense stimulating the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Defects in autophagy by alterations of the function of lysosomes in part by changes in their physico-chemical properties lead to impairment of lipophagy and mitophagy, perpetuating the induction of steatosis and mitochondrial dysfunction. In addition, the increase in cholesterol content impairs the function of immune cells particularly CD8+ lymphocytes. The figure was generated by BioRender under the agreement number SN298QD1XP. “Interplay of players involved in the progression of MASLD and ALD” created in BioRender. Fernández-Checa, J. C. (https://BioRender.com/8wflzpu) is licensed under CC BY 4.0. ER: endoplasmic reticulum; CPT-1: carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1; STARD1: steroidogenic acute regulatory protein 1; FAO: fatty acid β-oxidation; CA: cholic acid; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; MetALD: metabolic dysfunction-associated alcohol-related liver disease; ALD: alcohol-related liver disease; SREBP: sterol regulatory element binding proteins.

Obesity, unhealthy diet and sedentary lifestyle are key contributors to both T2D and MASLD. In line with that, lifestyle interventions aiming at dietary changes and increased physical activity constitute an established therapeutic approach [46]. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that weight loss of 5–7% can reverse steatosis while higher weight loss can reverse fibrosis. However, many participants undergoing lifestyle intervention fail to lose weight, and many regain weight after the end of the study [46]. Because of that, many advocate for bariatric surgery as the more reliable method to achieve long-term weight loss [47]. While this invasive method is associated with potential side effects such as dysphagia, abdominal discomfort, or nutritional deficiencies, large studies with long-term follow-up demonstrated that it decreases the overall mortality as well as the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and major adverse liver outcomes [48, 49]. As an alternative approach, several weight-reducing drugs have been recently developed. Among them, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and sodium-glucose co-transport 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) are commonly used in individuals with diabetes and are associated with reduced MACEs and overall mortality [50–52]. Among GLP-1 RAs, semaglutide was tested in a phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (RCT), showing a higher rate of resolution of MASH than placebo [53]. These results were strengthened by a phase 3 RCT where semaglutide improved liver histology in more patients than the placebo arm [54]. Similarly, encouraging results were reported for SGLT2is, in that dapagliflozin outperformed placebo in improvement of histological MASH in a recent RCT [55]. While GLP-1 RAs remain the best studied class of drugs leading to weight loss due to decreased food intake, their effect can be strengthened by combination with glucagon receptor and/or glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonists. Among such drugs, the dual agonists tirzepatide and survolutide were able to resolve MASH without worsening fibrosis in the corresponding phase 2 RCTs [56, 57]. These data remarkably demonstrate the usefulness of weight-reducing approaches in MASLD. While these drugs show beneficial extrahepatic effects, none of these agents are currently approved for treatment of MASLD and their prescription is currently reimbursed only in patients with diabetes in most countries.

As the leading liver disease worldwide, MASLD became a coveted pharmaceutical target and yielded unprecedented insights into the relevance of several signaling cascades. Recently, resmetirom, a liver-directed, thyroid hormone receptor beta (THR-β)-selective agonist, became the first FDA-approved MASH agent and highlighted the importance of endocrine signaling in MASLD [58]. Earlier studies demonstrated impaired THR-β function and the corresponding decrease in β-oxidation of fatty acids in MAFLD. The approval of resmetirom is based on a phase 3 RCT where it was superior to placebo in both MASH resolution and improvement of liver fibrosis [59]. FGF21 is another hormone regulating glucose and lipid metabolism as well as insulin sensitivity. While FGF21 agonist pegozafermin led to improvement in liver fibrosis in a phase 2b RCT, the FGF21 agonist efruxifermin did not reduce fibrosis in subjects with MASH-related cirrhosis [60, 61]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) belong to widely studied nuclear receptors that play an important role in liver metabolism, inflammation, and fibrogenesis. Their broad hepatoprotective effects are substantiated by recent clinical trials that led to approval of two PPAR agonists for treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) [62, 63]. In a phase 2b RCT, the pan-PPAR agonist lanifibranor significantly improved a histological MASH score without worsening liver fibrosis [64].

The advancement of liver-directed RNA silencing approaches (RNAi) [65] opened the possibility of personalized treatment of MAFLD directed at the key genetic risk factors. In that sense, the treatment with the PNPLA3 RNAi JNJ-75220795 resulted in decreased liver steatosis in two independent phase 1 RCTs [66], while the HSD17β13 RNAi associated with improved alanine aminotransferase levels [67]. Finally, a repurposing of FDA-approved drugs might also be beneficial in MASLD as shown in a recent RCT that reported a decreased steatosis in subjects treated with low-dose aspirin for 6 months [68].

Finally, since existing findings indicated that the type rather than the amount of fat emerged as an instigator of lipotoxicity and sensitization to advanced stages of MASLD, with cholesterol playing a key role [42, 69, 70], it has been shown that statins may be another pharmaceutical approach for MASH. In this regard, Yun et al. [71] reported that statins are significantly associated with reduced liver-related event risk in patients with MASLD, especially among those with elevated alanine aminotransferase levels, suggesting a viable preventive strategy for such a population.

Until recently there was a clear distinction between patients suffering from MASLD and patients with ALD, which was mainly based on the average daily or weekly alcohol intake (old definitions: NAFLD: women < 10 g of pure ethanol per day; men < 20 g of pure ethanol per day; ALD: women > 50 g of pure ethanol per day; men > 60 g of pure ethanol per day) [13]. However, this differentiation excluded a large group of (overweight) patients showing clear signs of steatotic liver disease, who were not consuming alcohol in amounts that would be considered ALD patients, but who were ingesting an amount of alcohol that would exceed the criteria for MASLD (women: 20–50 g, men: 30–60 g) [5]. Indeed, it is rather common for high-calorie foods to be consumed alongside moderate and even higher alcohol intake. Moreover, it has been suggested that surveys on self-reported alcohol consumption may be similar to energy reporting in overweight and obese individuals [72–74]. Together, this may result in misleading estimations of intake and subsequently of the prevalence of MetALD. Therefore, the recent estimates of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2017–2020 consider that steatotic liver disease was prevalent in 37.85% of individuals, of whom 32.45% were diagnosed with MASLD, 1.17% with ALD, and 2.56% with MetALD [75]. Also, data from the NHANES 2017–2018 have revealed marked disparities in the prevalence of MetALD and ALD in the US, which were related to ethnicity and living circumstances, e.g., food safety, suggesting the involvement of other factors [76, 77]. Using data from the UK Biobank, Schneider et al. [78] reported that 10.8% of SLD cases could be attributed to MetALD, indicating that the prevalence of MetALD may be higher in Europe than in the US. Interestingly, the average alcohol intake per person in individuals over 15 years has been reported to be rather similar between UK (9.7–10.7 L in 2024–2025) and the US (8.7–9.97 L in 2024–2025) [79, 80], while the prevalence of overweight or obesity seems to be even higher in the US than in the UK [81]. Stockwell et al. [82, 83] demonstrated in several studies that self-completed questionnaires using quantity-frequency and graduated-frequency methods may be subject to significant underreporting, which can be partially overcome by combining these assessments with an evaluation of beverage-specific yesterday consumption (BSY). However, it needs to be noted that the latter methods do not capture long-term drinking patterns. Taken together, further studies assessing the prevalence of MetALD among patients with MASLD are needed using other, more objective tools to complement 24-h recalls, food frequency questionnaires, and CAGE and AUDIT-C assessments of alcohol intake, in order to achieve a better overview of prevalence and related risk factors. Indeed, in recent years, biomarkers of alcohol intake such as phosphatidylethanol, ethyl glucuronide, ethyl sulfate, and fatty acid ethyl esters have become widely available and have been reported to be useful additions when assessing alcohol ingestion [84–86]; however, they, too, may only reflect alcohol intake in the recent past.

As the amount of alcohol consumed differs markedly between patients with ALD (alcohol intake women: > 350 g/week, men: > 420 g/week) and patients with MetALD (alcohol intake women: > 140 g/week, men: > 210 g/week), there is an ongoing discussion as to whether these patients require a different treatment, especially since patients with ALD may suffer from the condition without additional cardiometabolic risk factors while these are present in patients with MetALD [87]. Indeed, while MetALD and ALD are both chronic, progressive, and potentially terminal liver diseases, they are also markedly different. For instance, acute alcohol-associated steatohepatitis, which is found in heavy and long-term drinkers, is characterized by significant inflammation, deranged liver function, and high mortality rates (20–50% at 28 days in severe cases) [88, 89]. Data on the prevalence of acute steatohepatitis in MetALD patients and its outcome are scarce. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that in women, MetALD is associated with a higher hazard for all-cause mortality (+83%), which is thought to stem from their greater susceptibility to developing more severe ALD at lower levels of alcohol intake [90]. This has been linked to differences in gastric alcohol metabolism by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), lower body water, and estrogen-related differences in the susceptibility to intestinal barrier dysfunction and macrophage activation by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [91–94]. Moreover, excessive alcohol intake in MASLD patients has been shown to be associated with a higher mortality risk than in non-drinkers [95]. Furthermore, especially extended binge drinking (at least 13 days/year) has been found to be related to a higher risk of mortality in a survey in the US [96]. However, as the number of studies on MetALD patients and models is still limited, no specific treatment besides abstaining from alcohol and changing lifestyle is currently available for the treatment of MetALD.

As acknowledged in many publications, MASLD and ALD are two clearly different pathological conditions (for an overview, see [97, 98]). It has also been suggested by the results of many studies that MASLD and ALD share several clinical and mechanistic features [97, 98]. For instance, disturbances in lipid metabolism resulting in intracellular lipid accumulation in hepatocytes have been shown to be integral in both MASLD and ALD [99]. Furthermore, in both diseases, this accumulation of lipids has been associated with ER stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately resulting in cell damage and death (Figure 1) [100]. The activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) triggers not only further inflammatory alterations but also enhances collagen synthesis and deposition, which has been linked to hepatocellular damage in both diseases [101]. Additionally, alongside the observed alterations in the liver lipid synthesis and subsequent stellate cell activation, both MASLD and ALD have also been associated with changes in intestinal microbiota composition and intestinal barrier dysfunction, subsequently leading to increased translocation of bacterial toxins as well as viral compounds [102, 103]. The latter have been linked to an activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-dependent signaling cascades, which lead to inflammation but also promote lipid accumulation and stellate cell activation in liver tissue. Indeed, in model organisms, the treatment with antibiotics has been shown to diminish both the development of MASLD and ALD [104, 105]. Whether a combination of a lifestyle/genetic factor promoting the development of MASLD and ALD exacerbated the different alterations, e.g., the disturbance of lipid metabolism, ER stress, and intestinal barrier dysfunction through additive or synergistic effects remains to be determined. The results of recent studies suggest that in the setting of IR, which is frequently found in MASLD patients, alcohol metabolism via ADH-dependent metabolism is impaired [106, 107]. Indeed, in these studies, it was shown that through TNFα- and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-dependent signaling cascades, the phosphorylation status of ADH in liver tissue is altered, subsequently leading to a loss of enzyme activity. It was further shown that in mice with MASLD, alcohol clearance was significantly lower than in MASLD-free control mice, further suggesting that alcohol is maintained longer in the system, which could evoke further damage [106]. This needs to be determined in larger human studies, as it may also have implications not only with respect to organ damage but also cognition and subsequently the use of machinery and behavior in traffic. Although gastric ADH may be an important player in alcohol metabolism and hence a determinant of the availability of alcohol in the circulation, once reaching the liver, the oxidative metabolism of alcohol is accounted for by cytochrome P450 2E1, whose expression is induced by alcohol consumption. Nevertheless, the implication of the impaired alcohol metabolism via ADH in MetALD in humans deserves further investigation.

In summary, the interaction of MASLD and alcohol consumption is still poorly understood, despite affecting a large yet unknown number of patients with steatotic liver diseases in many countries. Further studies are needed to assess the number of individuals affected using better, more reliable tools. Studies in patients and animals with MASLD have reported impaired ADH activity; however, the impact of this impairment on alcohol elimination in humans remains to be determined. Furthermore, there is limited data assessing the interaction between MASLD and elevated alcohol consumption at the organ and cellular levels. As our understanding of the molecular mechanisms is still limited, there are few therapies beyond lifestyle interventions such as abstinence and weight reduction.

Universally recognized as the powerhouse of cells, mitochondria generate ATP in the respiratory chain to accomplish myriad cell functions. Despite this ancestral function, they are highly dynamic organelles that act as metabolic hubs, regulating calcium homeostasis, heme synthesis, and the genesis of crucial intermediary metabolites in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, some of which act as the building blocks for the synthesis of lipids required for membrane assembly [108–111]. Therefore, it is not surprising that alterations in mitochondrial function play a determinant role in the pathogenesis of metabolic liver diseases, such as ALD and MASLD. Although the etiology of ALD and MASLD is different, they share common biochemical characteristics, including not only liver injury, oxidative stress, steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis, as discussed in the preceding section Metabolic liver diseases, but also mitochondrial dysfunction. Indeed, alterations in mitochondrial function are a common and determinant event for ALD and MASLD, opening the perspective that both could be considered as mitochondrial diseases [112, 113]. An emerging aspect to keep in mind is that besides the prevalence of ALD, alcohol consumption also occurs in the context of obesity and MASLD, leading to a new paradigm where alcohol intake coexists with metabolic alterations and cardiovascular risks, coined MetALD and covered in the section Metabolic liver diseases, which accounts for most cases of chronic metabolic liver disease and alcohol consumption. An additional open question sparked by the contrast of findings between human and mouse is whether the loss of mitochondrial function is a cause or a consequence of disease progression. In this narrative, we will briefly summarize the link between mitochondria and lipid metabolism and its involvement in the onset of steatosis and progression towards advanced stages, including alcohol-mediated steatohepatitis and MASH.

The imbalance between the availability of lipids in the liver and their metabolism (e.g., catabolism and transport) contributes to hepatic steatosis, a reversible condition that occurs in both ALD and MASLD that can progress to advanced stages, such as alcoholic steatohepatitis and MASH that ultimately can culminate in HCC [114–116]. Adipose tissue lipolysis and hepatic de novo lipogenesis triggered by IR can overwhelm compensatory mechanisms to cope with the excess of fat present in hepatocytes, mainly the packaging of triglycerides into lipoproteins for excretion, and impaired fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) in mitochondria. Fatty acids can be oxidized at different carbons (α, β, and γ), with the β-oxidation being the process that takes place in mitochondria through the respiratory chain, which requires the assistance of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 (CPT-1) for the import of long-chain fatty acids through the mitochondrial inner membrane (MIM) for catabolism in the respiratory chain [117]. In this regard, mitochondrial dysfunction has been described in patients with IR, and impaired mitochondrial respiratory chain components have been described in human MASH [118, 119]. In support of the contribution of impaired mitochondrial β-oxidation to hepatic steatosis, inhibition of CPT-1 by malonil-CoA contributes to fatty acid accumulation as triglycerides in hepatocytes [120, 121]. Although IR is a hallmark and a driver of MASLD pathogenesis and the onset of hepatic steatosis as the initial stage of the disease, whether impaired β-oxidation contributes to IR is controversial. For instance, increased hepatic FAO by adenovirus-mediated CPT-1 overexpression in diabetic db/db mice has been recently reported as a molecular therapy for obesity and IR [122]. However, CPT-1 inhibition in skeletal muscle has been shown to improve insulin signaling in diet-induced obese mice, and unchanged CPT-1 activity has been reported in MASH patients [123, 124]. In analogy to MASLD, alcohol oxidative metabolism disrupts mitochondrial function and hence impairs oxidative phosphorylation both in experimental models and patients with ALD, contributing to the onset of alcohol-mediated hepatic steatosis [113, 114, 125]. Thus, in addition to mechanisms leading to increased de novo lipogenesis triggered by ER stress, impaired mitochondrial FAO and decreased CPT-1 expression can further contribute to fatty acid accumulation and steatosis both in ALD and MASLD (Figure 1) [126, 127]. A remaining question is whether the decreased FAO is a specific process or reflects a general impairment in mitochondrial function, which needs to be clearly established vis-à-vis the species-dependent alterations in mitochondrial function in ALD [113], and the opposing outcome of mitochondrial dysfunction between experimental models and patients with MASLD (see below).

Besides different morphology (macro vs. microvesicular), steatosis reflects the accumulation of a variety of lipids, including triglycerides, fatty acids, and cholesterol (free and esterified). Pioneering studies using nutritional and genetic models of liver steatosis established that the accumulation of free cholesterol, particularly in mitochondria sensitized hepatocytes to inflammatory cytokines, promoting the transition from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis [42]. The trafficking of cholesterol to mitochondria is governed by STARD1, the founding member of a family of proteins with cholesterol binding domain, whose inactivation results in fatal adrenal lipoid hyperplasia and inability to synthesize steroid hormones, illustrating the critical role of this protein in steroidogenic tissues to metabolize cholesterol in the MIM to pregnenolone, the precursor of steroid hormones and neurosteroids in hypothalamic neurons [128, 129]. The basal levels of STARD1 in the liver are low, but under alcohol intake leading to ALD and ER stress underlying the nutritional overload of MASLD, STARD1 expression is markedly overexpressed leading to mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking to the MIM, where it is metabolized by CYP27A1 to 27-hydroxycholesterol [37, 69, 130]. Besides the increase of this oxysterol, which acts as a precursor of CDCA, the primary BA synthesized in the mitochondrial alternative pathway, STARD1-mediated cholesterol trafficking results in accumulation of cholesterol in the MIM, which results in far-reaching consequences, such as disruption of mitochondrial physical properties, leading to decreased membrane fluidity that impairs mitochondrial antioxidant defense, illustrated by the depletion of mitochondrial glutathione (GSH) [131–135]. In addition, cholesterol accumulation in MIM interferes with the assembly of respiratory supercomplexes, underlying the impairment in the respiratory capacity, stimulates the generation of superoxide anion resulting in oxidative stress, and stabilizes hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), leading to metabolic reprogramming with impaired oxidative phosphorylation and stimulated glycolysis [136]. In support of the role of STARD1 in metabolic liver disease, increased expression of STARD1 at the mRNA and protein levels has been described in models and patients with ALD and MASH [37, 69, 130]. The pool of cholesterol in mitochondria plays a multifactorial role in fostering the transition from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, namely by promoting hepatocellular injury and oxidative stress, inflammation, and liver fibrogenesis secondary to the activation of HSCs, underlying the onset of MASH. Mitochondrial cholesterol also contributes to the MASH-driven HCC not only by inducing the reprogramming of BA metabolism, but also by switching the synthesis of BAs from the classic pathway to the alternative mitochondrial pathway, which unlike the former is insensitive to BA-mediated repression of CYP7A1 [37]. While STARD1-dependent BA synthesis stimulates carcinogenesis through the induction of transcription factors involved in the stemness, self-renewal, and inflammation, the enrichment of mitochondria in cholesterol and subsequent impact on mitochondrial membrane fluidity impairs chemotherapy that targets the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway by restraining the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and subsequent engagement of the apoptosome [135]. Interestingly, the expression of CYP7A1 decreases in ALD, but patients with alcoholic hepatitis exhibit increased levels of BAs, which correlate with the clinical score [137]. These results imply that alcohol-induced STARD1 expression mediates the cholestasis accompanying the progression of alcohol-induced steatosis to alcoholic hepatitis. Furthermore, acute-on-chronic model of ALD disclosed not only an early induction of STARD1 preceding the onset of hepatic steatosis and liver injury, but the overexpression of STARD1 exhibited a zonal pattern, with a predominant expression in perivenous (PV) hepatocytes, coinciding with the area where CYP2E1 is mostly expressed that correlates with the depletion of mitochondrial GSH and the onset of oxidative stress [130]. These findings indicate that chronic alcohol feeding caused a zone-dependent morphological change in the shape and number of mitochondria, inducing an increase in the number of mitochondria in the PV area with respect to the periporal (PP) zone. Thus, while steatosis is characterized by the accumulation of different types of lipids, the increase in cholesterol and its trafficking to mitochondria has emerged as a key player in both ALD and MASLD.

As succinctly described above, the impairment of mitochondrial function described in patients with ALD and MASLD has been associated with disease progression, suggesting that loss of mitochondrial function is a cause of the disease. However, this concept has been challenged in both diseases by the availability of experimental studies using genetic models of mitochondrial dysfunction. For instance, mice with liver or muscle specific deletion of apoptosis inducing factor, a mitochondrial protein originally described as a crucial player in apoptosis, and later shown to play a pivotal role in the maintenance of a functional respiratory chain, exhibited impaired oxidative phosphorylation activity, as expected, with defects in Complex I and IV of the respiratory chain, that upon high fat diet consumption, exhibited increased insulin sensitivity, a leaner phenotype, and resistance to steatosis and MASH progression compared to control littermates [138]. Similar findings were reported in mice with deletion of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, exhibiting generalized defects in mitochondrial function, expected from the crucial role of TFAM in mitochondrial physiology, that was accompanied by increased glucose uptake in skeletal muscle due to increased glucose transporter 1, while deletion in adipose tissue resulted in resistance to diet-induced obesity, IR, and hepatosteatosis [139, 140]. Taken together, these findings suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction and defects in the respiratory chain are protective against diet-induced obesity, IR, and MASLD. In the context of ALD, intriguing studies have shown that chronic alcohol intake, either orally or intragastrically in mice, caused increased state III respiration associated with enhanced levels of Complex I, IV, and V incorporated into the respiratory chain that reflected the effects of alcohol in the expression of PGC1α, the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [141]. These findings imply that enhanced mitochondrial respiration in mice fed an alcohol-containing diet stimulated the replenishment of NAD+ from NADH oxidation to accelerate the oxidative metabolism of ethanol. These findings contrast with the pioneering studies in rats, which show depression of mitochondrial respiratory capacity with defects in the synthesis of subunits of the main respiratory complexes such as NADH dehydrogenase, cytochrome b-c1 (Complex III), and the ATP synthase complex (Complex V). Interestingly, the increased susceptibility of mice vs. rats to alcohol-induced liver damage implies that the stimulation of the mitochondrial respiratory capacity contributes to enhanced alcohol metabolism and subsequent induction of oxidative stress and recruitment of downstream players involved in ALD. Thus, further research will be required to establish whether the impairment of mitochondrial function described in patients with ALD and MASLD contributes to the onset of disease or is a consequence of the disease progression.

BAs were historically regarded as detergents required for the emulsification and absorption of dietary lipids. This simplistic view has dramatically evolved over the past two decades, with BAs now recognized as multifunctional signaling molecules that participate in systemic metabolic regulation, immune homeostasis, and host-microbiome interactions [142, 143]. BAs act not only as digestive surfactants but also as hormones that regulate glucose and lipid metabolism, energy expenditure, inflammation, and fibrosis through nuclear and membrane-bound receptors such as FXR, Takeda G-protein receptor 5 (TGR5), vitamin D receptor (VDR), pregnane X receptor (PXR), and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 (S1PR2).

The relevance of BA biology to clinical hepatology and gastroenterology has grown substantially. Dysregulated BA metabolism contributes to bile acid diarrhea (BAD), cholestatic liver disorders, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), colorectal neoplasia, and MASLD, as mentioned above (see section Metabolic liver diseases). Evidence indicates that changes in BA quantity and quality are closely linked to MASLD severity and fibrosis progression.

Beyond their detergent role, BAs are potent signaling molecules. FXR senses BA levels in hepatocytes and enterocytes. In the ileum, FXR induces FGF19, which acts in the liver to suppress CYP7A1, limiting BA synthesis. FXR also regulates lipid metabolism and inflammation. TGR5 is expressed in enteroendocrine L-cells, where it induces GLP-1 release, linking BAs to glucose homeostasis. It also reduces inflammation in macrophages. VDR and PXR regulate detoxification and immune responses, with PXR being particularly important for xenobiotic metabolism. S1PR2 mediates direct BA signaling in HSCs, linking BAs to fibrosis [144].

The gut microbiota diversifies the BA pool through deconjugation, dehydroxylation, and epimerization reactions. Bile salt hydrolases (BSHs), expressed by Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium spp., deconjugate taurine- and glycine-conjugated BAs. The 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria such as Clostridium scindens convert CA to DCA and CDCA to LCA. Other taxa epimerize CDCA to UDCA, a therapeutically important hydrophilic BA [145]. These microbial conversions alter BA hydrophobicity, cytotoxicity, and receptor affinity.

The gut microbiota and BAs exist in a dynamic, bidirectional relationship that influences host physiology. On the one hand, intestinal microbes modify BAs through enzymatic transformations; on the other hand, BAs act as antimicrobial agents that shape the composition of the microbiota. This mutual regulation is increasingly recognized as a critical factor in digestive and metabolic diseases.

As mentioned, BSHs modify primary BAs driven by Clostridium scindens and related taxa [145–147]. Secondary BAs influence immune cell differentiation. For instance, isoallolithocholic acid promotes regulatory T cell development, while taurine-conjugated BAs can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, driving inflammation. BA signaling through FXR in intestinal epithelial cells maintains barrier integrity by regulating tight junction proteins and antimicrobial peptide production. TGR5 activation in macrophages reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine release, linking BA signaling to mucosal immunity [147, 148].

In health, balanced BA-microbiome interactions support homeostasis. In disease, dysbiosis leads to altered BA pools. Patients with IBD exhibit reduced microbial diversity and decreased secondary BA levels, weakening FXR/TGR5 signaling and perpetuating inflammation [149]. In MASLD, dysbiosis favors taurine-conjugated BAs and reduces FXR agonists, promoting metabolic dysfunction and fibrosis [150, 151]. Importantly, fecal BA signatures are being investigated as noninvasive biomarkers to stratify disease activity in IBD, MASLD, and colorectal cancer (CRC) [152, 153].

BAD occurs when BA reabsorption in the ileum is defective or feedback regulation via the FXR-FGF19 axis is impaired. Primary BAD, often underdiagnosed, is linked to inadequate FGF19 signaling, leading to unchecked CYP7A1 activity and hepatic BA overproduction [154]. Secondary BAD results from ileal resection, Crohn’s disease, or cholecystectomy.

Diagnostics include serum 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (C4), with values > 48 ng/mL suggestive of BAD, and fasting FGF19 < 145 pg/mL. The SeHCAT retention test has excellent sensitivity and specificity. Fecal BA quantification remains a gold standard but is cumbersome [155].

First-line therapy is BAs sequestrants, though tolerability is limited. FXR agonists and FGF19 analogs represent emerging therapies that target the underlying pathophysiology [156].

Cholestasis results in the intrahepatic retention of hepatotoxic BAs. In PBC, UDCA is standard, but many patients are incomplete responders [157]. Obeticholic acid is approved as a second-line therapy but is limited by pruritus. In primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), norUDCA showed significant benefit in a 2025 phase 3 trial [158]. Recent findings indicated an increased expression of STARD1 in patients with PBC, suggesting that the mitochondrial alternative pathway of BA synthesis could play a role in PBC pathogenesis [159].

In pediatric cholestasis, ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT) inhibitors such as maralixibat and odevixibat are approved, reducing pruritus and serum BA levels [160].

IBD is characterized by altered BA pools with reduced secondary BAs, weakening FXR/TGR5 signaling. This contributes to barrier dysfunction and inflammation. Experimental studies show that BA supplementation or intestine-restricted FXR agonists restore epithelial barrier integrity and modulate immunity [149, 161]. Microbiome-targeted therapies are also under investigation [162].

Primary conjugated BAs such as taurocholate stimulate spore germination, while secondary BAs such as DCA and LCA inhibit growth. Antibiotic-induced dysbiosis reduces secondary BAs, predisposing to CDI. Fecal microbiota transplantation restores BA profiles and reduces recurrence [146, 162].

Secondary BAs, particularly DCA, promote tumorigenesis by inducing oxidative stress, DNA damage, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling [163]. Epidemiological studies show higher fecal BA load in Western diets and CRC patients [152]. Loss of FXR in colonic tissue amplifies tumorigenesis.

As mentioned above, in MASLD, BA metabolism is profoundly altered, with elevated conjugated and 12α-hydroxylated BAs. Dysregulated FXR-FGF19 signaling leads to excessive BA synthesis, while taurocholate activates stellate cells via S1PR2, promoting fibrosis [150, 164, 165]. Dysbiosis shifts microbial BA metabolism toward pro-fibrogenic profiles, worsening inflammation [151].

Serum conjugated BAs (GUDCA, GCDCA, TCDCA) correlate with histologic severity and fibrosis. Therapeutics including FXR agonists, FGF19 analogs, and resmetirom (THR-β agonist approved in 2024), illustrate how BA modulation is central to MASLD management [166–168].

Multiple serum, fecal, and imaging-based biomarkers have emerged to quantify BA metabolism. Serum C4 and FGF19 are useful for diagnosing BAD, while serum BA panels predict fibrosis in MASLD [150, 151, 155]. Fecal BA profiling characterizes IBD, CRC, and CDI, while SeHCAT is highly sensitive for BAD diagnosis [155, 165].

BA-targeted therapies range from UDCA to novel small molecules, biologics, and microbiome interventions. NorUDCA showed benefit in PSC, while obeticholic acid, cilofexor, and tropifexor reduce fibrosis but are limited by side effects [157, 158, 167]. FGF19 analogs and engineered mRNA restore BA signaling but raise safety concerns. IBAT inhibitors are approved in pediatric cholestasis [160]. Microbiome-directed therapies, including FMT, restore secondary BA production in CDI. Resmetirom, a THR-β agonist, was FDA-approved in 2024 for MASH [168], but whether this agent affects BA homeostasis or not remains to be established.

Challenges include assay standardization, balancing therapeutic efficacy with safety, and addressing patient heterogeneity [167–169]. Microbiome therapy outcomes remain variable, and long-term safety of FXR agonists and FGF19 analogs requires further study. Future directions include plasma BA panels in clinical practice, approval of norUDCA, development of microbiome-based BA modulators, and AI-driven BA modeling for personalized therapy.

BAs have emerged as central modulators of digestive and metabolic diseases. Advances in mechanistic understanding, biomarker discovery, and targeted therapies highlight their dual role as pathogenic drivers and therapeutic opportunities. In MASLD, specific BA signatures contribute to fibrogenesis, making them attractive diagnostic and therapeutic targets. The next decade promises integration of BA-focused strategies into precision hepatology and gastroenterology.

DILI is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the USA and European countries [170]. Most cases of acute liver failure in the US are caused by acetaminophen (APAP) overdose [171]. APAP is considered safe at therapeutic doses. However, an overdose of APAP can lead to the accumulation of APAP protein adducts, resulting in mitochondrial damage, DNA fragmentation, hepatocyte necrosis, sterile inflammation, and potentially liver failure [172]. Many adaptive and survival mechanisms can counteract these adverse effects, but the failure or insufficiency of these mechanisms can ultimately lead to liver failure [172].

One of these adaptive and protective mechanisms is autophagy. Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved intracellular degradation pathway involving lysosomes that break down proteins, lipids, and organelles such as excess ER, ribosomes, and damaged mitochondria [173, 174]. Autophagy is often activated and serves as an adaptive response to adverse stresses such as starvation or exposure to xenobiotics, functioning as a cell survival mechanism by providing nutrients and building blocks to maintain cellular homeostasis [175–178].

There are three main types of autophagy: macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy), microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). These types differ in how cargoes are delivered to lysosomes [179]. Autophagy involves the formation of a double-membrane autophagosome that encloses the autophagic cargo and transports it to a lysosome, where the membranes fuse to create an autolysosome that degrades the autophagic cargo with lysosomal acidic hydrolytic enzymes [173]. Microautophagy involves lysosomes directly engulfing autophagic cargos, bypassing the formation of autophagosomes [180, 181]. CMA involves the recognition of cellular proteins that contain the pentapeptide motif (KFERQ) by cytosolic chaperones such as the heat shock cognate protein of 70 kDa (HSC70). These chaperone proteins then bind to lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A (LAMP-2A), which triggers LAMP-2A multimerization. This results in the formation of a translocation complex that transports CMA substrates across the lysosomal membrane for degradation [182–184]. Microautophagy and CMA have been previously reviewed for their mechanisms and role in liver pathophysiology [185, 186]. However, their link to DILI has not been thoroughly studied. Below, we will focus on the current understanding of autophagy mechanisms and their possible roles in DILI, specifically in APAP-induced liver injury (AILI).

Autophagy provides several mechanisms to protect against AILI. First, autophagy can help remove the APAP-AD likely through the autophagy receptor protein SQSTM1/p62 because genetic deletion of p62 slows down the clearance of APAP protein adducts in hepatocytes [187, 188]. Pharmacological inhibition of autophagy/lysosomal functions by chloroquine delays lysosomal clearance of APAP protein adducts and increases liver injury in mice [187, 188]. In contrast, activating autophagy pharmacologically safeguards against AILI in mice. However, it is important to recognize that after a single, severe overdose of APAP, autophagy can rescue cells at the periphery of the necrotic area [188], leading to a reduced area of necrosis [187–189]. In contrast, after multiple low doses of APAP, autophagy can completely prevent liver injury [189], suggesting that the protective effect of autophagy is dose-dependent.

While pharmacological manipulation of autophagy has led to a clear conclusion regarding the protective role of autophagy against AILI, results from studies using genetic deletion of essential autophagy-related genes in mice are complex. Liver-specific Atg5 knockout mice are resistant to AILI due to the compensatory activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway and repletion of hepatic glutathione pools, while unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1 and 2 (Ulk1/2) double knockout mice inhibit JNK activation to protect against AILI [190, 191]. The difference between the results from genetic autophagy-deficient mouse models and the pharmacological manipulation of autophagy on AILI may be due to chronic versus acute autophagy deficiency. Increased Nrf2 activation is likely a secondary effect of long-term autophagy inhibition in mouse livers, serving as an adaptive response driven by the activation of non-canonical Nrf2 pathways. Second, mitochondrial damage is an early key event leading to hepatocyte death after APAP overdose [192]. Autophagy can assist in removing damaged mitochondria induced by APAP via selective mitophagy, likely through the PINK1-PARKIN pathway [193]. Third, APAP impairs hepatic transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of gene expression of autophagy-related genes and lysosomal biogenesis genes. Genetic or pharmacological activation of TFEB promotes the clearance of APAP-AD and protects against AILI in mice [194, 195]. Fourth, APAP-induced hepatocyte necrosis can lead to the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which further activate Kupffer cells (KCs), resulting in the release of cytokines and chemokines that recruit immune cells, such as neutrophils and circulating monocytes. The role of inflammation in AILI remains debatable, as both protective and harmful effects have been reported, depending on the dose of APAP and the stage of AILI (early phase vs. late phase) [196]. Restricting the expansion of necrotic areas and removing necrotic cells are crucial for liver repair and recovery from AILI [197]. Increasing evidence suggests that activated macrophages and neutrophils play a crucial role in removing necrotic cells and promoting liver repair and regeneration. The expression of ATG5 decreased in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) in aged mice, and these mice were more susceptible to thioacetamide (TAA)-induced liver injury compared with young mice. Restoration of ATG5 in BMDM protects against TAA-induced liver injury in mice [198]. Moreover, myeloid-specific Atg5 knockout mice also had increased liver injury and inflammation after alcohol exposure [199]. In addition, macrophage ATG16L1 deletion inhibits liver regeneration by promoting and sustaining cGAS-STING pathway activation in mice [200]. While these findings suggest a protective role of immune cells (in particular macrophage autophagy) against AILI, future studies are needed to investigate the role of macrophage autophagy in AILI using these macrophage-specific autophagy-deficient mice. In conclusion, current evidence clearly supports a protective role of autophagy against AILI. Future studies to determine whether and how activating autophagy would promote necrosis resolution and liver regeneration, and to identify new potent autophagy activators, are important for translating these findings to clinical applications.

The pancreas is a unique organ that has both endocrine and exocrine functions. Pancreatitis is characterized by increased necrosis of acinar cells, the exocrine cells in the pancreas, followed by a local and systemic inflammatory response, which can have a varied clinical presentation and course of progression. Acute pancreatitis is a common gastrointestinal condition with an annual incidence of 34 per 100,000 person-years in developed countries without successful treatments. Chronic alcohol consumption accounts for 17% to 25% of acute pancreatitis cases worldwide, although hypertriglyceridemia, hypercalcemia, viral infections, genetics, and autoimmune diseases may also contribute to pancreatitis [201–203].

Pancreatic exocrine acinar cells have high rates of protein synthesis to produce and secrete large numbers of digestive enzymes during the feeding process. To meet the demand for protein synthesis and secretion, acinar cells have a highly enriched ER and vesicle trafficking system. Maintaining the ER, other organelles, and protein homeostasis is thus crucial for regulating acinar cell functions. When the regulation of organelle and protein homeostasis is disrupted, it can cause ER stress, mitochondrial damage, and improper intracellular trypsinogen activation, ultimately leading to acinar cell death and the onset of pancreatitis. As a cellular organelle and protein quality control mechanism, autophagy is therefore vital for maintaining organelle homeostasis and adaptation to protect the acinar cells. Below, we briefly review the current understanding of autophagy and its role in maintaining acinar cell homeostasis and function in pancreatitis.

Accumulation of large vacuoles in acinar cells has been frequently observed in human and experimental pancreatitis. These large vacuoles are LC3 positive and morphologically identified as large autolysosomes, likely resulting from impaired autolysosomal functions. The expression levels of both LAMP-1 and LAMP-2, two lysosomal membrane proteins, decreased in five different rat and mouse models of pancreatitis [204]. More importantly, genetic deletion of LAMP-2 in mouse acinar cells causes impaired autophagy in the exocrine pancreas, leading to the accumulation of large vacuoles in acinar cells and spontaneous pancreatitis [204]. Deletion of Atg7 in pancreatic epithelial cells (likely both acinar cells and endocrine cells) using Pdx-Cre in mice leads to chronic pancreatitis with increased inflammation and fibrosis [205]. In another mouse model, systemic deletion of Atg7 using a doxycycline (DOX) inducible mechanism in mice also led to pancreatic damage resembling mild acute pancreatitis [206]. Deletion of Atg5 specifically in acinar cells using Elastase-Cre in mice only leads to mild pancreatic injury, but these mice are more susceptible to pancreatitis induced by cerulein or Lieber-Decarli liquid diet [207]. Ethanol exposure also impaired autophagy by stabilizing ATG4B to promote alcohol-associated pancreatitis [208]. Vacuole membrane protein 1 (VMP1) is an ER phospholipid scramblase that is crucial for regulating autophagosome closure and the secretion of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) proteins [209–213]. An early study shows a correlation between increased VMP1 expression and acinar cell vacuolization in arginine-induced acute pancreatitis in rats [214]. Subsequent studies showed that the loss of acinar cell VMP1 in mice led to spontaneous pancreatitis associated with increased ER stress and Nrf2 activation [215]. It is unclear, however, whether overexpression of VMP1 also impairs autophagy in acinar cells, but deleting VMP1 in these cells indeed severely impairs autophagy, as shown by increased pancreatic LC3-II levels and p62, probably due to impaired autophagosome closure [215]. Further research will be required to dissect the causal role of VMP1 in pancreatitis. TFEB is a master regulator for the gene expression of autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis. TFEB is downregulated in human pancreatitis and experimental pancreatitis induced by either cerulein or alcohol. More importantly, pharmacological or genetic activation of TFEB protects against cerulein or alcohol-induced pancreatitis in mice [207, 216].

Autophagy may help protect against the development of pancreatitis through several mechanisms. First, due to the high translational capacity of acinar cells, increased protein synthesis can lead to the accumulation of misfolded proteins and ER stress. These misfolded proteins can be efficiently removed by autophagy, which helps alleviate ER stress. Second, trypsinogen is stored in zymogen granules within acinar cells, but these granules can become fragile, resulting in their release into the cytosol and subsequent activation of trypsinogen. This activation can cause acinar cell death. Autophagy can selectively remove these zymogen granules via zymophagy, thereby preventing trypsin activation and cell death. While the specific receptor for selective zymophagy has not been identified, increased VMP1 has been associated with zymophagy in AR42J cells [217]. Third, excess ER material can be removed through ER-phagy to reduce ER stress. Though specific ER-phagy receptors have not yet been identified for pancreatitis, VMP1 has several potential LIR domains that may serve as ER-phagy receptors and warrant further investigation. Fourth, damaged mitochondria contribute to acinar cell death and pancreatitis, but these organelles can be removed via selective mitophagy. The increased accumulation of damaged mitochondria, resulting from impaired autophagy, promotes experimental pancreatitis [218]. Mitophagy is regulated by the well-known PINK1-PARKIN pathway and involves a group of specific mitophagy receptor proteins [219, 220], although whether the PINK1-PARKIN pathway and these mitophagy receptor proteins play a role in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis remains unclear.

In conclusion, autophagy protects acinar cells from adverse conditions by maintaining organelle and protein homeostasis through multiple quality control pathways. Future research should aim to identify the specific receptors involved in these forms of autophagy and determine whether pharmacological targeting of these pathways could be beneficial against pancreatitis.

One of the most fundamental questions in the study of metabolic disease progression is how triglyceride accumulation—classically considered a “safe” mechanism for energy storage—can ultimately sensitize hepatocytes to cell death and promote tissue damage. Steatotic liver disease encompasses a wide pathological spectrum, ranging from simple steatosis, defined by excess triglyceride deposition in hepatocytes, to more advanced stages characterized by necroinflammation, fibrosis, and eventual hepatic failure [221–224].

Lipotoxicity is defined as the exposure of cells to increased levels of (toxic) lipid species, often in the context of metabolic liver diseases such as MASLD (often in combination with IR, which can aggravate the lipotoxicity and/or dyslipidemia). The primary target cell of lipotoxicity in the liver is the hepatocyte, although non-parenchymal cell types in the liver also respond to exposure to increased levels of lipids [225, 226].

Lipotoxicity is often discussed in the context of hepatocyte damage. The effects of (excess) lipids on non-parenchymal liver cells, such as HSCs, KCs, and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), have been less studied. FFAs can activate KCs via their TLRs. HSCs lose their lipid content during activation, potentially aggravating the exposure of other liver cell types to lipids. In contrast, direct effects of FFAs on HSCs have not been explored in detail yet. LSECs may very well be the first target of excessive lipid content in the liver [227]. The response of LSECs to FFAs is different from hepatocytes: The unsaturated fatty acid (UFA) oleate is protective in hepatocytes but toxic in LSECs. The response to FFAs also varies with the type of endothelial cells: LSECs respond differently to FFAs than vascular endothelial cells [228]. Finally, lipotoxic cell death of hepatocytes may lead to secondary activation (inflammation, fibrogenesis) of KC and HSCs. Lipids may also induce hepatocyte senescence, leading to the induction of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype, contributing to an inflammatory response of the non-parenchymal cells [229].

Recent studies demonstrate that the deleterious effects induced by lipids are partially regulated by the interaction of saturated fatty acids (SFAs) with LPS. Obesity increases sensitivity to endotoxin-mediated liver injury, which is manifested in fatty liver sensitivity to acute inflammation and injury [230–232]. Therefore, a better understanding of the direct and indirect effects of lipids (and lipotoxicity) on non-parenchymal cells, and the interplay between hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells, is needed.

In addition to increased levels of lipids in metabolic liver diseases, the role of altered lipid profiles should also be investigated in more detail: It has been shown that UFAs like oleate can mitigate the toxic effects of SFAs like palmitate. In addition, the effects of UFAs/SFAs may be different in non-parenchymal cells like LSECs [228]. This observation suggests that modifying the lipid profile in patients with metabolic diseases may be a target for intervention, although results have been disappointing until now. This may be due to a lack of targeting and/or attaining sufficient levels of ‘beneficial’ lipids in the target cells. In this regard, targeted delivery to liver cells, using nanocarriers, may be an option to explore in the future.

Another interesting finding in in vitro studies is that lipotoxicity in hepatocytes is characterized by a lack of lipid droplet accumulation rather than an excessive accumulation of lipid droplets [225, 226]. This is counterintuitive given the observation of excessive accumulation of lipid droplets in hepatocytes in MASLD. The SFA palmitate is lipotoxic to hepatocytes but does not induce lipid droplet accumulation, whereas the UFA oleate is not toxic and induces lipid droplet accumulation. Moreover, oleate attenuates the lipotoxic effect of palmitate and increases lipid droplet accumulation. A possible explanation is that increased lipid accumulation initially is a protective mechanism to sequester toxic lipid species. However, prolonged and excessive exposure to lipids, as in MASLD patients, may exceed the limit of ‘safe’ lipid droplet storage, leading to changes in lipid droplet dynamics and metabolism resulting in lipotoxicity. More studies are needed to elucidate the role of lipid droplets in the pathogenesis of MASLD, focusing on size, distribution, composition, and dynamics [226, 233]. Another aspect is that not all UFAs behave equally in terms of the mechanisms of lipotoxicity. For instance, myristic acid, another UFA, is not lipotoxic by itself but potentiates palmitic acid-induced lipotoxicity by sustaining the synthesis of ceramide through the myristoylation of ceramide desaturase [234]. In this regard, diets enriched in myristic and palmitic acid markedly induce MASH by channeling the use of palmitic acid in the generation of ceramide de novo. Thus, different lipotoxic lipids may induce cell death through specific pathways.

The exposure of hepatocytes to excessive amounts of lipids induces stress in various organelles, such as mitochondria and the ER, and oxidative stress. The effects of excessive lipid exposure, particularly FFAs, on mitochondria have been described extensively in recent reviews [225, 226, 229]. Impairment of mitochondrial function, in particular β-oxidation and ATP production, increases the generation of ROS and depletes cellular antioxidants. At the early stage of MASLD, exposure to a high influx of lipids increases mitochondrial oxidation; however, this oxidation is incomplete, and increases the production of ROS and oxidized (toxic) lipid intermediates [125, 235], leading to the further impairment of mitochondrial function and, eventually, cell death [236, 237]. Diminished mitochondrial function itself also increases ROS generation, thus creating a vicious cycle of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress.

Another target of (toxic) lipids in the context of metabolic diseases is the ER. The initial, protective response to lipid exposure of the ER is activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR). However, sustained activation of the UPR leads to ER stress. The UPR is composed of three branches: the transmembrane proteins RNA-dependent protein kinase-like ER eukaryotic initiation factor-2α kinase (PERK), the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and the inositol-requiring ER-to-nucleus signaling protein-1 (IRE1α). The activation of these branches of the UPR counteracts ER stress, but sustained activation of these pathways leads to a pro-inflammatory response and, eventually, cell death. The role of the ER in lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity is complex and bidirectional: Not only is the ER a target for lipotoxicity, but the ER is also involved in lipid homeostasis.

De novo lipogenesis takes place in the ER, where excess free SFAs are incorporated into phospholipids of the ER membrane, leading to Ca2+ release, mitochondrial permeability impairment, and activation of pro-inflammatory and cell death pathways [225, 226, 238]. This causes ER stress and compromises normal ER function, triggering the UPR [225, 226, 238]. Activation of the UPR and ER stress can also increase lipogenesis: ER stress activates the transcription factor sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs), leading to enhanced lipid synthesis [239–242]. SREBP transcription factors are master regulators of hepatic lipid metabolism [239–242]. In normal conditions, they are attached to ER membranes as inactive precursors. Upon activation, e.g., by low sterol levels, these precursors are cleaved, and a water-soluble fragment then translocates to the nucleus [239–242]. Activation of the PERK-p-eIF2α signaling pathway promotes lipid accumulation via SREBP activation [241–243]. In addition, ATF4 and ATF6 can activate SREBPs and play an important role in lipid homeostasis during ER stress, mainly by increasing hepatic lipogenesis [243–246].

The excessive incorporation of SFAs into ER membranes in conditions of lipid overload reduces the presence of other lipid species in the ER membranes, such as sphingomyelin and cholesterol [247]. Moreover, SFA overload in the ER increases the ratio of phosphatidylcholine (PC)/phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), resulting in the inhibition of sarco/ER calcium ATPase (SERCA) activity and disrupting ER calcium homeostasis. In normal conditions, the ER is characterized by a very high Ca2+ concentration, maintained by the SERCA-ATPase. This regulation is important for ER function since many chaperone proteins and enzymes involved in protein folding and maturation processes are dependent on high Ca2+ levels [238].

Lipotoxicity, caused by the accumulation of FFAs, cholesterol, ceramides, and other toxic lipid intermediates, is a central driver of hepatocyte injury in steatotic liver disease and steatohepatitis. The hepatotoxic effects of lipids converge on regulated cell death (RCD) pathways, including apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis, autophagy-dependent death, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis. These processes interact, shaping inflammation, fibrosis, and disease progression.

Apoptosis is the most extensively studied RCD pathway in the liver and is strongly driven by lipotoxicity. SFAs such as palmitate induce ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative injury, activating the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. This involves mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, cytochrome c release, apoptosome formation, and caspase-9/-3/-7 activation. The extrinsic pathway, mediated by death receptors (e.g., TNFR, FAS), is also sensitized by lipotoxicity: FFAs upregulate death ligands and decrease anti-apoptotic proteins, enhancing caspase-8 activation. In hepatocytes (type II cells), mitochondrial amplification via BID cleavage is required, again highlighting the lipid-mitochondria connection. Apoptosis contributes directly to inflammation and fibrosis by releasing apoptotic bodies that activate Kupffer and stellate cells [248–250].

Toxic lipids induce mitochondrial overload, ROS production, and calcium imbalance, all of which favor mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT). In lipotoxic hepatocytes, sustained opening of the MPT pore collapses the membrane potential and leads to necrotic rupture, releasing DAMPs. Free cholesterol and SFAs destabilize mitochondrial membranes, lowering the threshold for pore opening. This necrosis amplifies sterile inflammation in steatohepatitis and may synergize with apoptosis to drive mixed injury patterns.

Lipotoxic conditions frequently create an environment that favors necroptosis. Inhibition of caspase-8 by lipotoxic stress (via oxidative modifications or c-FLIP regulation) allows receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) and RIPK3 to form the necrosome, which phosphorylates MLKL to disrupt membranes. Experimental models have shown that SFAs increase RIPK3 expression in non-parenchymal cells and sensitize hepatocytes to necroptotic injury. Necroptosis contributes to inflammatory amplification in MASH, since ruptured cells release pro-inflammatory lipids and DAMPs that further activate immune pathways.

Autophagy normally serves a protective role in lipotoxicity, clearing lipid droplets (lipophagy) and damaged mitochondria (mitophagy). However, excessive lipid load can overwhelm autophagy or impair lysosomal function, shifting the balance toward injury. In some models, blocking autophagy exacerbates lipotoxic apoptosis and necrosis, while in others, dysregulated or excessive autophagy contributes to hepatocyte loss. For example, impaired autophagic flux in steatohepatitis worsens lipotoxic stress by preventing the clearance of lipid peroxides and damaged mitochondria. Thus, autophagy in the lipotoxic liver is double-edged: protective under moderate stress but potentially death-promoting when overloaded.