Affiliation:

1Experimental and Translational Medicine, Health Sciences Department, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Mexico City 09340, Mexico

2Graduate Program in Experimental Biology, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Mexico City 09340, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8991-8533

Affiliation:

3Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908, U.S.A.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7773-9848

Affiliation:

4Basic Research Division, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Mexico City 14080, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3906-4493

Affiliation:

5Laboratory of Translational Cardiology, Translational Medicine Laboratory, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez, Mexico City 14080, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8671-3367

Affiliation:

5Laboratory of Translational Cardiology, Translational Medicine Laboratory, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez, Mexico City 14080, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4688-8271

Affiliation:

1Experimental and Translational Medicine, Health Sciences Department, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Mexico City 09340, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2372-5405

Affiliation:

1Experimental and Translational Medicine, Health Sciences Department, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Mexico City 09340, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6963-2642

Affiliation:

1Experimental and Translational Medicine, Health Sciences Department, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Mexico City 09340, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3923-6278

Affiliation:

1Experimental and Translational Medicine, Health Sciences Department, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Mexico City 09340, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8249-7257

Affiliation:

1Experimental and Translational Medicine, Health Sciences Department, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Mexico City 09340, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0501-7226

Affiliation:

1Experimental and Translational Medicine, Health Sciences Department, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Mexico City 09340, Mexico

Email: bioexpp22@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1353-260X

Affiliation:

1Experimental and Translational Medicine, Health Sciences Department, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, Mexico City 09340, Mexico

Email: legq@xanum.uam.mx

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5704-5985

Explor Dig Dis. 2025;4:1005108 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/edd.2025.1005108

Received: September 27, 2025 Accepted: November 12, 2025 Published: December 30, 2025

Academic Editor: Matias Avila, University of Navarra, Spain

Aim: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 90% of liver tumors and is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Current treatments have poor outcomes for HCC, highlighting the urgent need for new and effective therapies. Growth differentiation factor 11 (GDF11), a member of the TGF-β superfamily, regulates differentiation, proliferation, and migration processes, effects observed in cancer, including HCC. In this study, we aimed to investigate the chemosensitizing effects on human liver cancer cells.

Methods: We pre-treated Huh7 and Hep3B cells with GDF11 50 ng/mL for 72 h in the presence of sorafenib (Sfb) or cisplatin (CDDP) and evaluated cellular response.

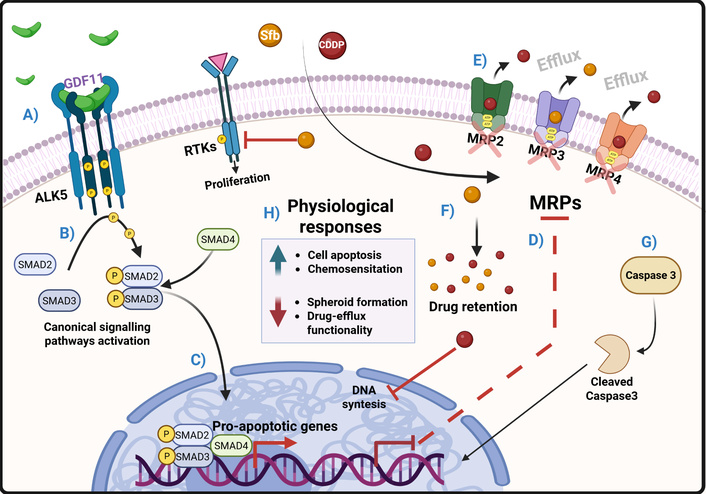

Results: Pre-treatment with GDF11 lowered the IC50 of CDDP and Sfb in Huh7 cells. Similar effects were observed in Hep3B cells. Additionally, combining GDF11 with CDDP or Sfb significantly reduced cell viability and decreased the size and number of spheroids. Furthermore, we found that the chemosensitizing effect is initiated by GDF11 binding to the type I receptor ALK5. Inhibition of ALK5 abolished SMAD2 activation, impacting the chemosensitizing effects. Finally, GDF11, combined with Sfb or CDDP, reduced the activity of drug transporters MRP2, MRP3, and MRP4, which explains its chemosensitizing properties.

Conclusions: GDF11 increases the sensitivity of HCC-derived cell lines to Sfb and CDDP by modulating the drug-efflux transporters MRP2, MRP3, and MRP4.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 90% of liver cancers [1, 2] and is the fourth most common cancer worldwide, with the highest mortality rate [3]. Alcohol consumption, hepatitis B and C infections, high-fat, and high-cholesterol diets are the main risk factors for HCC [1, 2]. Regardless of the cause of damage, the progression of liver disease is well known, beginning with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), fibrosis, and cirrhosis, which can develop into HCC; however, the etiology determines the pathobiology of the HCC, making it a really heterogeneous type of cancer [4, 5].

HCC is much more complex than other types of cancer and is highly aggressive due to poor differentiation, which leads to a high metastatic capacity and drug resistance [4]. It depends heavily on abnormal metabolism, especially involving lipids like cholesterol, resulting in a poor prognosis and a herculean task to treat it [6].

Treatments for HCC depend on the stage of the disease. However, potentially curative options such as radio ablation, percutaneous ethanol injection, hepatectomy, and liver transplantation are only suitable in the early stages (i.e., stages 0 and A) of the disease, according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system [7]. Unfortunately, these early stages account for less than 30% of cases due to diagnostic challenges [4]. The five-year overall survival (OS) rate with these treatments is approximately 90%. Still, disease recurrence occurs in 70–80% of treated cases [4].

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is a treatment used for intermediate and advanced stages of the disease (i.e., BCLC B or C), involving the local delivery of chemotherapeutic agents such as cisplatin (CDDP) or doxorubicin [8]. This therapy typically results in a median OS of 26 months [4, 9]. In more advanced stages, such as BCLC C, systemic therapies are available, including sorafenib (Sfb), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), which generally offers a median OS of 2.8 months [4, 10]. Another recently FDA-approved treatment for HCC is the combination of bevacizumab and atezolizumab, anti-angiogenesis and immune checkpoint monoclonal antibodies, respectively; this new therapy has demonstrated superior efficacy to Sfb, with an OS of approximately 10 months [4, 10]. Therefore, developing new strategies of treatment to improve patients’ quality of life and longevity is essential. In recent years, biotechnology drugs such as atezolizumab and bevacizumab have attracted significant interest in HCC treatment due to their promising efficacy and safety profiles. These treatments include antibodies, oncolytic viruses, and recombinant proteins, such as cytokines, growth factors, and hormones, demonstrating their potential in biomedicine [11].

As previously noted, Sfb and cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (CDDP or cisplatin) demonstrated limited efficacy in treating HCC [12, 13]. Nonetheless, it continues to serve as a therapeutic option in scenarios where atezolizumab combined with bevacizumab is either unavailable or unfeasible. Consequently, the development of an adjuvant therapy that improves the efficacy of Sfb could confer significant benefits to patients with HCC.

One of the cytokines that has recently attracted considerable attention regarding its impact on tumor biology is growth differentiation factor 11 (GDF11), which is a member of the TGF-β superfamily and the bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) subfamily [14]. GDF11 exerts a relevant biological function in the early stages of embryonic development, particularly directing the differentiation of the anterior/posterior axes [15, 16]. In adults, various tissues produce GDF11; the highest level of transcripts has been identified in the brain’s hippocampal region, whereas the liver exhibits the lowest expression of GDF11 [15], suggesting a poor relevance in well-differentiated hepatic cells. In the adult stage, GDF11 plays multiple roles in muscle and neurological processes, erythropoiesis, aging, and cancer [15, 16].

GDF11, like other members of the TGF-β family, transduces its signal through the canonical pathway using type II and I receptors, which are responsible for ligand binding and signal internalization, respectively. GDF11 binds to activin receptors type II A (ActRIIA) and ActRIIB, which possess serine/threonine kinase activity; these recruit and phosphorylate type I receptors and activate activin-like kinase (ALK) 4, 5, or 7. ALK 4, 5, and 7 also possess serine/threonine kinase activity and phosphorylate R-SMAD proteins, mainly 2 and 3, although some reports suggest the involvement of SMAD 1, 5, and 8 [14–16]. The protein Co-SMAD (SMAD4), which contains a nuclear localization sequence, binds to the phosphorylated SMAD2/3 dimer, allowing it to translocate into the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, the trimer binds to consensus regions of other transcription factors, chromatin modifiers, co-repressors, and coactivators, which will initiate the expression of the target genes of the pathway, depending on the interacting factors [14–16].

In 2019, Gerardo-Ramírez and colleagues [17] reported that GDF11 can decrease the aggressiveness of several HCC-derived cell lines (Huh7, Hep3B, SNU-182, and Hepa 1-6); GDF11 reduced cell proliferation, metastatic potential, colony formation, spheroid formation, and invasiveness. These results showed that GDF11 treatment causes transcriptional repression of cyclins D1 and A, along with overexpression of p27. Additionally, GDF11 treatment increased the expression of epithelial markers such as E-cadherin and occludin. At the same time, it decreased mesenchymal markers like N-cadherin and Snail, confirming that GDF11 induces a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) [17]. Later, we reported that GDF11 also reduces abnormal lipogenesis by inhibiting cholesterol and triglyceride synthesis through a mechanism involving the downregulation of the Akt signaling pathway in the Huh7 and Hep3B cell lines [18].

Additionally, we reported that GDF11 alters mitochondrial ultrastructure and functionality. Another reported effect was a negative regulation of glycolytic capacity (Warburg effect) in these models (Hernandez et al., 2021 [18]). Other works have demonstrated the antitumoral effects of GDF11 in other cancer cells. For example, Liu and collaborators observed similar effects to those described in HCC, but in pancreatic cancer cells (Liu et al., 2018 [19]). We have also reported similar findings in leukemia cells [20]. In the case of breast cancer, reports have shown the ability of GDF11 to reduce tumor cell aggressiveness, functioning as a tumor suppressor [21].

Therapies available for treating HCC are effective in the early stages of the disease (BCLC 0 and A); however, in most cases, HCC is diagnosed in advanced stages, where therapeutic options are limited to chemoembolization and systemic therapies [4].

Although systemic agents such as Sfb and bevacizumab/atezolizumab remain mainstays for advanced HCC, rapidly evolving clinical trials and molecular insights are offering new hopes [4, 22]. There is now a strong rationale for investigating molecular adjuvants that enhance current therapies while minimizing toxicity. GDF11 may sensitize tumors to chemotherapy or immunotherapy, further improving efficacy and quality of life, an approach that aligns with the latest international strategies to personalize and optimize HCC management.

Cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) and maintained in William’s medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. W4125-10X1L, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Cat. SH30910.03, Marlborough, MA, USA) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco, Cat. 15240062, Waltham, MA, USA) in an atmosphere of > 90% humidity, 5% CO2, and 37°C. Cell lines were mycoplasma-free; we performed the mycoplasma detection protocol as previously reported [23]. Cell line authentication was confirmed using short tandem repeat analysis.

Cells were pretreated with human recombinant GDF11 (Peprotech, Cat. 120-11, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) at 50 ng/mL in complete growth media, every 24 h for 72 h [17, 18]. Cells were treated with CDDP (Accord, Cat. 7506335700217, Worli, Mumbai, India) or Sfb (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. SML2633-50MG) at different concentrations. After 72 h, cells previously treated with GDF11 were incubated for 48 h. Cell viability assays were performed. We used SB-431542 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. S4317-5MG) for the inhibition of ALK5 receptor at different concentrations. We put the treatment with SB-431542 30 min before GDF11 treatment.

Huh7 cells were treated with a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Cat. CK04-20, Rockville, MD, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The IC50 was calculated using Prism GraphPad 8 with the function log(inhibitor) vs. normalized response,

A total of 1 × 103 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate precoated with 2% low-gelling temperature agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. A9045-25G, St. Louis, MO, USA) in complete medium for 14 days. Spheroids were counted and measured using an inverted microscope Axiovert A1 FL-LED (Carl Zeiss, Cat. 12838065, Jena, Germany). For multicellular spheroids, 2.5 × 103 cells per well were seeded in Nunclon-Sphera U-shape-bottom 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. 174925, Waltham, MA, USA), and cells were centrifuged for 7 min at 250 g for three days. Spheroids were treated with 50 ng/mL GDF11 every 24 h up to 72 h.

A Western blot was performed following the previously reported protocol [17]. Protein quantification was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) kit (Invitrogen, Cat. 23225, Waltham, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Proteins were loaded onto precast 4–20% gels (Bio-Rad, Cat. 4561094, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to PVDF membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. 88520, Waltham, MA, USA). Specific antibodies were used as described in Table 1. Immunoreactive bands were identified with PierceTM ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate (Invitrogen, Cat. 32134). Images were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Primary antibodies were used in this study.

| Protein | Catalog number | Company | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-SMAD2 | 138D4 | Cell Signaling Technologies | 1:1,000 |

| SMAD2 | D43B4 | Cell Signaling Technologies | 1:1,000 |

| β-actin | A3854 | Sigma-Aldrich | 1:10,000 |

| MRP2 | sc-59611 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | 1:200 |

| MRP3 | 14182 | Cell Signaling Technologies | 1:1,000 |

| MRP4 | 12705 | Cell Signaling Technologies | 1:1,000 |

An apoptosis assay was performed as described previously [24]. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with methanol and acetic acid (3:1) for 15 min. Cells were stained with 2 μg/mL of propidium iodide/RNAse solution (R&D Systems, Cat. 4817-60-04, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 15 min. Images were obtained using a fluorescence microscopy Axiovert A1 FL-LED (Carl Zeiss). Apoptotic cells were counted.

Drug-efflux pumps assay was performed using Calcein-AM (Invitrogen, Cat. C1430) and Rhodamine-123 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. 83702-10MG), both of which are MDR and MRP substrates. Cells were seeded in a black 96-well plate with a clear bottom and treated with 50 ng/mL GDF11 every 24 h for 72 h. Cells were incubated with Calcein-AM 0.25 μM or Rhodamine-123 5 μM, and the fluorescence was measured in a multimode reader Cytation 3 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) every 5 min for 60 min. Calcein and Rhodamine are substrates of drug transporters, so, in the case of drug-efflux transporter inhibition, the fluorescence within the cell will diminish over time.

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Data are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, was used to compare means between groups. GraphPad Prism 8.02 software (Dotmatics, CA, USA) for macOS was utilized. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

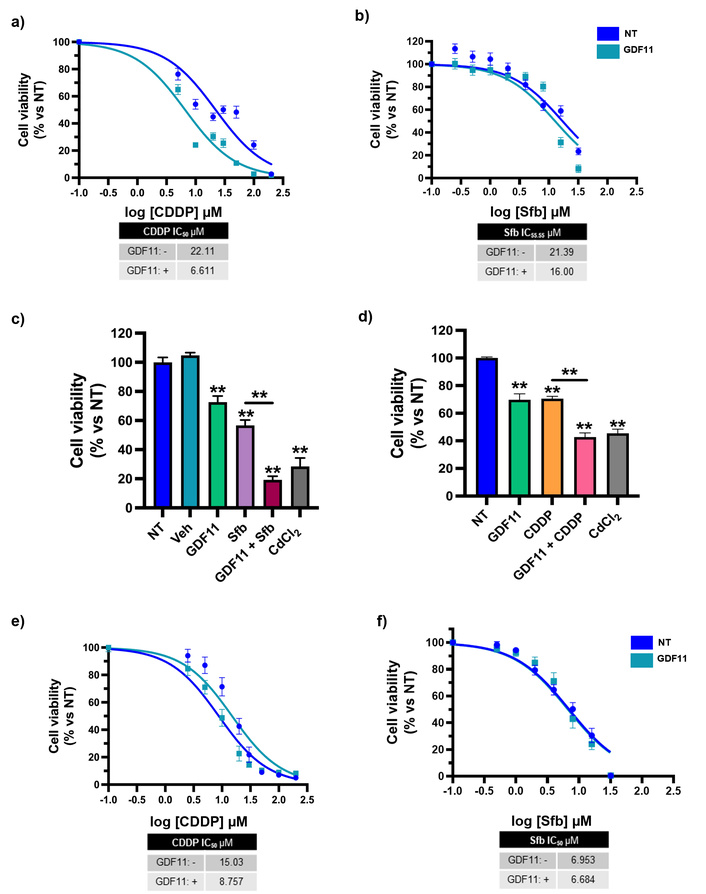

Huh7 cell lines were pretreated with 50 ng/mL GDF11 every 24 h over a period of 72 h. Subsequently, cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of cisplatin (CDDP: 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, 100, and 200 µM) or sorafenib (Sfb: 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 µM) for an additional 48 h; for Hep3B treatment we used CDDP: 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, 100, and 200 µM or Sfb: 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 µM for 48 h. In Huh7 cells, co-treatment with GDF11 and CDDP led to a pronounced reduction in the IC50 value from 22.11 to 6.611 µM. We didn’t find a significant difference at the Sfb IC50, but we did observe the IC55.55 reduction from 21.39 to 16.00 µM following GDF11 co-administration (Figure 1a–b). These results were mirrored in cell viability assays, which showed a significantly greater reduction in cell viability for the combination treatments compared to either drug alone (Figure 1c–d). Comparable trends were observed in Hep3B cells: GDF11 pretreatment reduced the CDDP IC50 from 15.03 to 8.757 µM, whereas Sfb co-treatment did not yield a significant difference in any point of the curve (Figure 1e–f). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that GDF11 sensitizes HCC cells to CDDP and, to a lesser extent, to Sfb, as evidenced by reduced IC50 values and enhanced cytotoxicity in vitro.

GDF11 sensitizes HCC-derived cell lines to CDDP and Sfb. (a) Cell viability dose-response curves of Huh7 cells pre-treated with GDF11 for 72 h, followed by CDDP, or (b) Sfb treatment for 48 h. (c) Cell viability assays of the Sfb IC55.55 (16.00 µM) and (d) CDDP IC50 (6.611 µM), obtained from the dose-response curves of Huh7 cells. We used CdCl2 at 10 µM as a positive control for cytotoxicity. Cell viability dose-response curves of Hep3B cells pre-treated with GDF11 (72 h), followed by (e) CDDP or (f) Sfb treatment for 48 h. Cell viability was determined by the CCK-8 assay. **p < 0.01. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. GDF11: growth differentiation factor 11; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; CDDP: cisplatin; Sfb: sorafenib; CCK-8: Cell Counting Kit-8; SEM: standard error of the mean.

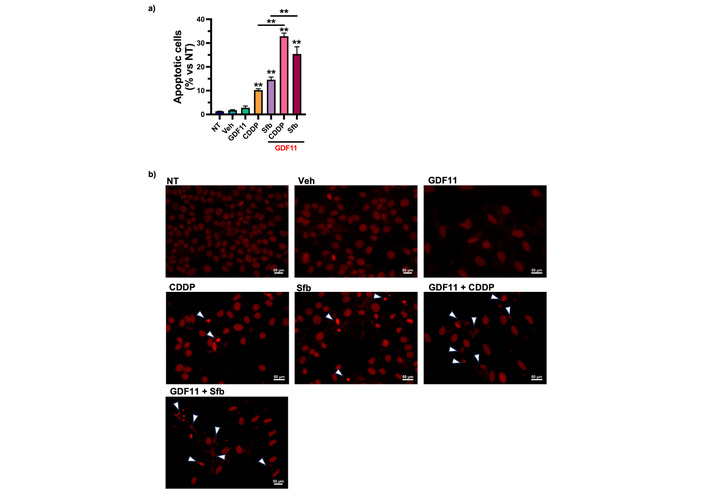

Huh7 cells were treated with GDF11 for 72 h and then treated with CDDP IC50 (6.611 µM) or Sfb IC55.55 (16.00 µM) for 24 h. We evaluated the apoptotic nuclear morphology of the cells, finding that the co-treatment increased the percentage of apoptotic cells treated with GDF11 plus Sfb or CDDP. This result suggests that GDF11 sensitized the cells, increasing apoptosis and exacerbating drug-induced effects (Figure 2).

The GDF11 pre-treatment sensitizes the Huh7 cells to apoptosis in combination with Sfb and CDDP. (a) Percentage of apoptotic cells stained with propidium iodide after pre-treatment with GDF11 for 72 h and subsequent treatment with Sfb IC55.55 (16.00 µM) and CDDP IC50 (6.611 µM) for 24 h. (b) Apoptotic nuclear morphology of the cells. White arrows indicate apoptotic cells. **p < 0.01. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. GDF11: growth differentiation factor 11; CDDP: cisplatin; Sfb: sorafenib; SEM: standard error of the mean.

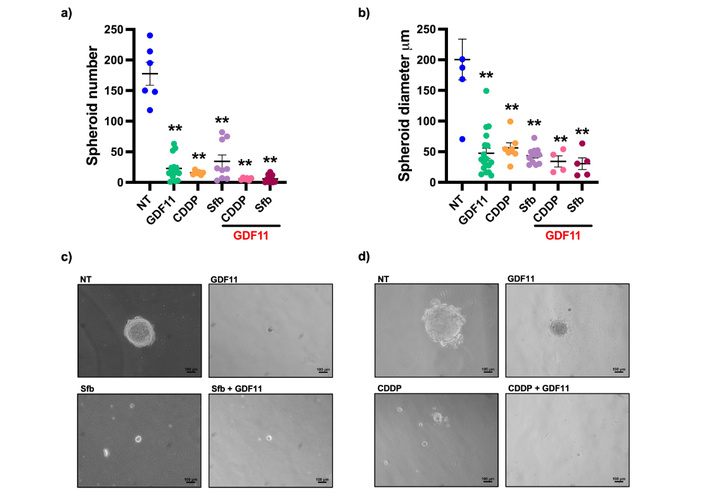

A spheroid formation assay was performed using the agarose-based method to analyze the antitumorigenic capacity induced by GDF11 and the drugs. Huh7 cells were treated with GDF11 as previously described. CDDP (6.611 µM) or Sfb (16.00 µM) was administered to the cells for 48 h. Cells were harvested, and a spheroid formation assay was performed. Results showed that GDF11 alone significantly reduced the spheroid number from 177.50 ± 46.28 (non-treated) to 22.73 ± 19.38 (Figure 3a). In comparison, Sfb alone was decreased to 34.22 ± 32.04. However, the GDF11 plus Sfb co-treatment reduced the spheroid number to 8.5 ± 6.37 (Figure 3a). The effect of CDDP on the number of spheroids was also analyzed, and it was observed that the co-treatment reduced the number to 5.66 ± 1.96, compared with CDDP alone, which resulted in 15.66 ± 3.20 (Figure 3a). GDF11 decreased the spheroid diameter to 47.31 ± 35.73 µm compared with the control 200.54 ± 81.82 µm. Sfb treatment reduced the diameter to 43.42 ± 12.71 µm, and the co-treatment reduced it to 28.26 ± 19.64 µm (Figure 3b). Similar results were obtained with the CDDP treatment; the diameter was reduced after the co-treatment to 34.05 ± 18.44 μm, compared with the CDDP alone, 56.08 ± 22.37 μm (Figure 3b). We show the micrographies of the spheroids treated with Sfb (Figure 3c) or CDDP (Figure 3d).

The GDF11 treatment reduced the number and diameter of spheroids. (a) Number of spheroids and (b) diameter of Huh7 cells treated with GDF11 + Sfb IC55.55 (16.00 µM) or CDDP IC50 (6.611 µM). (c) Phase contrast representative micrographies of spheroids treated with GDF11 + Sfb (16.00 µM) or (d) CDDP (6.611 µM). **p < 0.01. Mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. GDF11: growth differentiation factor 11; CDDP: cisplatin; Sfb: sorafenib; SEM: standard error of the mean.

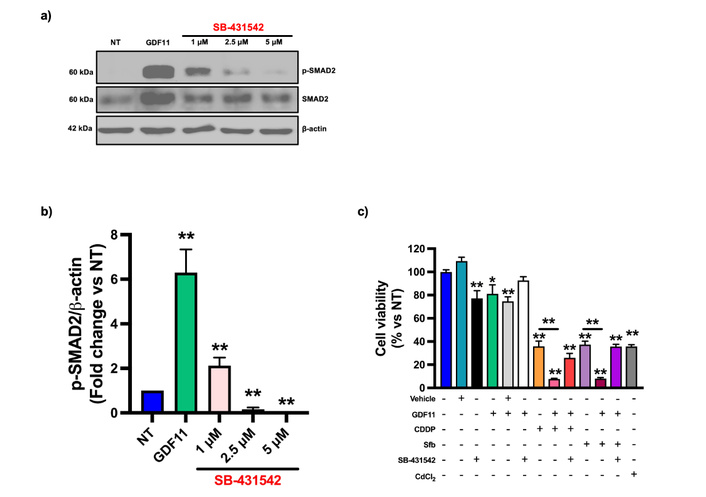

Huh7 cells were treated with 1, 2.5, and 5 μM [25] of SB-431542, an ALK5 inhibitor, for 30 min; then, cells were treated with GDF11 for 30 min. A Western blot was performed to detect the phosphorylation of SMAD2. SB-431542 reduced the activation of SMAD2; this reduction in the protein content was similar to that of the non-treated group (Figure 4a–b). To corroborate whether the chemosensitizing effect was mediated by ALK5 receptor, Huh7 cells were treated with the ALK5 inhibitor at 5 µM during GDF11 pre-treatment for 72 h. The inhibition of the receptor reversed the chemosensitizing effect induced by GDF11, restoring the cell viability to the same level as Sfb or CDDP treatments alone (Figure 4c).

The GDF11 chemosensitizing effects are mediated through ALK5. (a) Western blot of p-SMAD2 from Huh7 cell lysates treated with GDF11 or GDF11 + ALK5 selective inhibitor SB-431542. (b) Densitometry analysis from Western blot. (c) Cell viability assays of Huh7 cells treated with GDF11, SB-431542, and CDDP (6.611 µM) or Sfb (16.00 µM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. GDF11: growth differentiation factor 11; CDDP: cisplatin; Sfb: sorafenib; SEM: standard error of the mean.

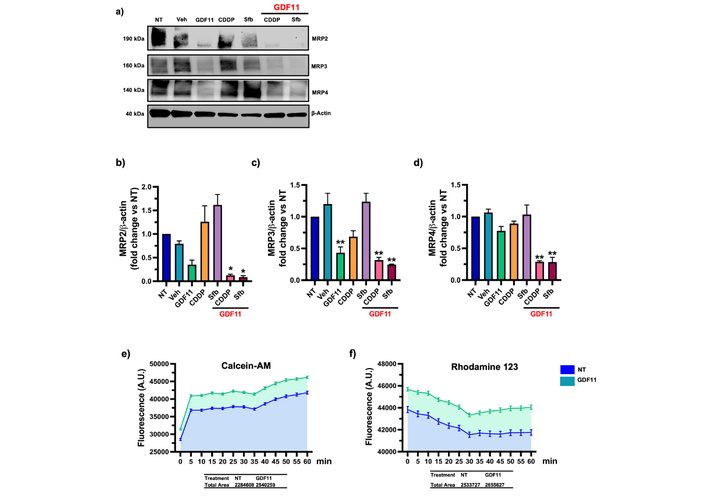

We evaluated the drug-efflux transporters to elucidate the mechanism of chemosensitivity to GDF11, which is known to be a primary mechanism of chemoresistance in cancer cells. Huh7 cells were pre-treated with GDF11 for 72 h, then treated with Sfb (16.00 µM) and CDDP (6.611 µM) for 24 h. We assessed the protein content of drug efflux transporters MRP2, MRP3, and MRP4. The co-treatment with GDF11 and Sfb or CDDP was found to reduce the protein levels of these drug-efflux transporters (Figure 5a–d). Next, we evaluated the functionality of drug-efflux transporters using Calcein-AM and Rhodamine-123 (MDR and MRP substrates, respectively). We found that treatment with GDF11 for 72 h increased intracellular fluorescence and the area under the curve of the corresponding graphs, suggesting that GDF11 reduces the cells’ capacity to extrude drugs (Figure 5e–f). These results strongly prove a chemosensitization mechanism mediated by GDF11-regulated drug transporter activity.

The GDF11 co-treatment with CDDP and Sfb reduced the content of drug efflux transporters in the Huh7 cells. (a) MRP2, MRP3, and MRP4 protein levels of Huh7 cells pre-treated with GDF11 for 72 h and CDDP (6.611 µM) and Sfb (16.00 µM) for 24 h. (b–d) Densitometry of MRP2, MRP3, and MRP4 protein content. (e) Drug efflux transporters functionality assay with Calcein-AM and (f) Rhodamine 123, area under the curve is represented as colored fill. A.U., arbitrary units. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. GDF11: growth differentiation factor 11; CDDP: cisplatin; Sfb: sorafenib; SEM: standard error of the mean.

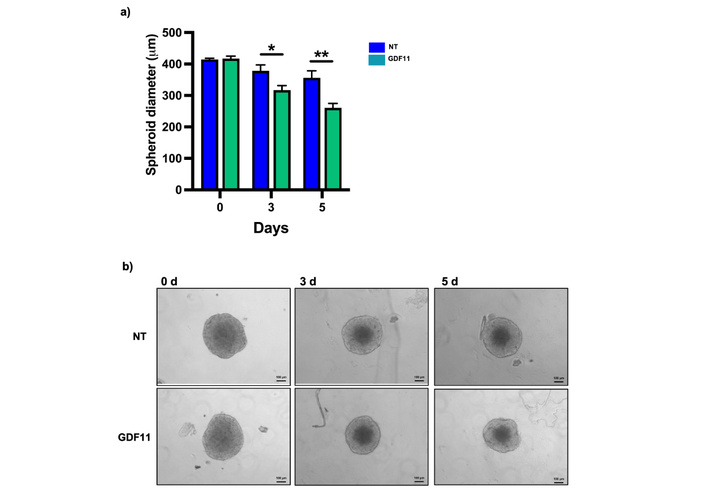

We performed a spheroid formation assay to evaluate the effect of GDF11 in a 3D model. The treatment with GDF11 reduced the size of the spheroids by 40% on day 5 of treatment, consistent with the in vitro results suggesting the antiproliferative effects of GDF11 (Figure 6). This finding validates the anti-tumoral activity of GDF11 reported in 2D cell line experiments.

GDF11 treatment reduces the diameter of Huh7 spheroids. (a) Diameter of spheroids on days 0, 3, and 5 of GDF11 treatment. (b) Micrography of Huh7 spheroids at the indicated treatment time, magnification 100×. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Each bar represents the median ± SEM of two independent experiments. GDF11: growth differentiation factor 11; SEM: standard error of the mean.

One of the principal challenges in HCC chemotherapy is the development of chemoresistance, which severely limits the efficacy of current treatments [26]. Overcoming this obstacle is critical to achieving more durable therapeutic responses and improving patient outcomes. GDF11 has recently garnered attention in cancer research due to its demonstrated anti-tumoral properties across multiple malignancies, including HCC, pancreatic, and breast cancers. Emerging evidence suggests that GDF11 not only inhibits tumor cell proliferation and invasiveness but may also sensitize resistant cancer cells to chemotherapy, highlighting its potential role as a therapeutic adjuvant to overcome chemoresistance in HCC [17–19, 21]. We provide strong evidence of GDF11’s chemosensitizing effects in an HCC in vitro model, combined with CDDP and Sfb, which reduced the drug concentrations needed to achieve a significant cytotoxic response in cancer cells.

We present evidence that a possible mechanism is mediated by the canonical signaling pathway of GDF11, specifically through the ALK5/SMAD2 axis. There are reports of the chemosensitizing effects of BMP subfamily members, to which GDF11 belongs, particularly in breast cancer, where the canonical SMAD2/3 pathway mediates these effects [27]. Reports suggest that the canonical pathway may induce cell cycle arrest by expressing p15, p27, and p21 through the FOXO transcription factors [28]. Previous reports proved that GDF11 induces the expression of p27 in HCC cells [17]. Additionally, SMAD2/3 can induce the expression of apoptotic proteins, such as TIEG, DAPK, and Bim. In some studies, this pathway is more likely to have anti-tumoral effects than the non-canonical pathway; however, this effect depends on several cellular factors [29]. Other reports suggest that SMADs may induce the expression of SLUG, a transcription factor associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and drug resistance [30]. Yao et al. (2010) [31] reported that the expression of IL-6 by TGF-β enhances STAT3 activation and reduces the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy.

It is essential to consider the opposing effects of the same signal pathway in other cancer models [31]. Additionally, TGF-β ligands can activate the non-canonical pathway through the TGF-β-associated kinase 1 (TAK1), which interacts with other signaling pathways, including Erk1/2, p38, JNK, NF-κB, WNT/β-catenin, and Akt/mTOR [29]. As we mentioned, our data suggest a chemosensitizing effect of GDF11 through the ALK5/SMAD2 signaling; these results are similar to those reported in non-cancer GDF11 models [32–34]. It is well established that drug-efflux transporters significantly contribute to the chemotherapy resistance observed in cancer cells by extruding chemotherapeutic agents, thereby reducing the efficacy of drugs such as CDDP and Sfb. It is well known that the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are remarkable inducers of chemoresistance, including MDR1, MRP2, MRP3, MRP4, and BCRP [35]; these proteins are particularly regulated by Nrf2, PXR, FXR, TGF-β, β-catenin, and Erk1/2; however, the exact mechanisms are still not fully understood [35–37]. Some studies have reported the effects of TGF-β on drug resistance via TAK1 [38]. Taking this into account, we could hypothesize that the chemosensitizing effects of GDF11 may be achieved by dysregulating Erk1/2 activation through alterations in TAK1 activity or SMAD2 [38]. Additionally, Erk1/2 is also a regulator of drug transporters [38]. We found that GDF11 reduced the content of drug-efflux transporters MRP2, MRP3, and MRP4, which are highly described as chemoresistance promoters in HCC, and also reduced the activity of MDR1 and MRP1 drug transporters by Calcein-AM and Rhodamine-123 assays, which could explain the chemosensitizing effects of GDF11 to CDDP and Sfb [36, 39]. Also, we hypothesize that SMAD2 could be repressing the transcription factors involved in the expression of chemoresistance drug transporters based on the anti-EMT effects of the GDF11 [17]. EMT induces the expression of these kinds of drug transporters by transcription factors as SNAIL, SLUG, and ZEB2 [39].

Another possible mechanism of chemosensitization by GDF11 could involve a metabolic shift and mitochondrial impairment, as demonstrated by our previous research [18]; there is strong evidence that impairment of cell metabolism, especially in mitochondria, correlates with chemosensitivity in HCC [18, 40–42]. In our model, GDF11 may also increase the expression of antitumoral genes; for example, the RNA-seq analysis from our research group showed a downregulation of the gene UCA1 [18], which encodes a lncRNA reported as pro-tumoral and related to chemoresistance, metastasis, and cell proliferation [43]. Due to its low expression in healthy tissues, UCA1 has non-oncogenic features and provides advantages to cancerous cells; it could be considered a cancer fitness gene and is a promising target in HCC [44]. This may partly explain the results we obtained, but further validation is needed. Additionally, we are testing the anti-tumoral effects of GDF11 in Huh7 spheroids. This validation is important because 3D models better recapitulate tumor characteristics than 2D models. Spheroids are positioned between 2D cell line culture and organoids in terms of complexity [45]. Our results are strong predictors of GDF11’s effects in more complex models like organoids or in vivo systems.

As limitations of this study, our results are based on experiments conducted with cell lines, which may not fully capture the complexity and heterogeneity of in vivo models. We must perform experiments with in vivo models to validate our in vitro results. Additionally, since cell lines may not reflect the diversity of HCC found in patients, validating our findings with human HCC samples is important to enhance the clinical relevance of our study.

In conclusion, our findings provide compelling evidence that GDF11 significantly enhances the sensitivity of HCC cells to two frontline chemotherapeutic agents by mechanisms involving modulation of key drug transporter expression and consequent reduction of the effective cytotoxic concentrations required for tumor cell inhibition. This chemosensitizing effect not only potentiates the therapeutic efficacy of CDDP and Sfb but also holds promise for reducing the doses needed to achieve antitumor activity, thereby mitigating the dose-limiting toxicities and adverse effects commonly associated with these treatments. Mechanistically, GDF11 activation of the canonical SMAD2/3 signaling pathway may underlie alterations in drug transporter expression and apoptotic regulation, consistent with its role as a tumor suppressor in HCC and other malignancies. These insights position GDF11 as a promising molecular adjunct to conventional therapies, offering a dual benefit of improved clinical outcomes and enhanced patient quality of life through reduced treatment-associated morbidity. Further preclinical and clinical investigations are warranted to elucidate its full therapeutic potential and optimize strategies for its integration into existing HCC treatment regimens.

ActRIIA: activin receptors type II A

ALK: activin-like kinase

BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

BMPs: bone morphogenic proteins

CCK-8: Cell Counting Kit-8

CDDP: cisplatin

EMT: epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

GDF11: growth differentiation factor 11

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma

OS: overall survival

Sfb: sorafenib

TAK1: transforming growth factor-β-associated kinase 1

We thank Dr. Alejandro Escobedo-Calvario for supporting the preparation of the manuscript and the graphical abstract. Secretaria de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI) [scholarship 2022-000018-02NACF-16729]. The SECIHTI wasn’t involved in any role related to this study; it only provided Natanel German-Ramirez with the scholarship for his Ph.D. studies.

NGR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. MGR: Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. GIDG: Writing—review & editing. VSA, LBO, BPA, and RUML: Methodology, Writing—review & editing. FMR and APA: Resources, Methodology. MCGR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing. ASN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. LEGQ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Luis E. Gomez-Quiroz, a member of the Editorial Board of Exploration of Digestive Diseases, was not involved in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

This work was supported by Fundación Mexicana para la Salud Hepática [Antonio Ariza Cañadilla grant 2022]. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 775

Download: 24

Times Cited: 0