Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Parakou, Parakou BP123, Benin

2Pulmonology Unit, Army Training and Teaching Hospital, Parakou 02BP1324, Benin

Email: efiomarianopp@yahoo.fr

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-4242-6442

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Parakou, Parakou BP123, Benin

3Pulmonology Unit, Borgou Regional and Teaching Hospital, Parakou BP02, Benin

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6504-7625

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Parakou, Parakou BP123, Benin

4Occupational Health Unit, Borgou Regional and Teaching Hospital, Parakou BP02, Benin

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9649-0232

Affiliation:

5Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Abomey Calavi, Cotonou 01BP188, Benin

6National Hospital and University Center for Pulmology and Phthisiology of Cotonou, Cotonou 01BP321, Benin

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1024-9665

Affiliation:

5Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Abomey Calavi, Cotonou 01BP188, Benin

6National Hospital and University Center for Pulmology and Phthisiology of Cotonou, Cotonou 01BP321, Benin

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7374-5546

Explor Asthma Allergy. 2026;4:1009108 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eaa.2026.1009108

Received: December 05, 2025 Accepted: January 13, 2026 Published: February 02, 2026

Academic Editor: Hae-Sim Park, Ajou University Medical Center, Korea (the Republic of)

Aim: Woodworking exposes carpenters to a higher risk of developing asthma or worsening pre-existing asthma. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of and factors associated with work-related asthma (WRA) among carpenters in Parakou in 2024.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical study with prospective data collection conducted from June to September 2024. Following a voluntary survey, the included carpenters were interviewed using the Occupational Asthma Screening Questionnaire-11 (OASQ-11) to assess the relationship between asthma symptoms and the occupational environment. Peak expiratory flow (PEF) variability and spirometry were also measured. Data were analyzed using R software version 4.4.1. Factors associated with WRA were identified using simple and multiple logistic regression analyses.

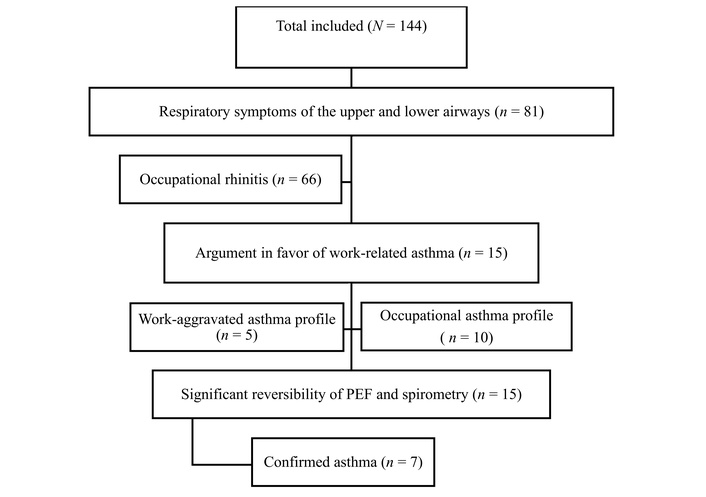

Results: Out of 153 carpenters/apprentices in 117 workshops, 144 (94.1%) were included, all of whom were male. The mean age was 35.9 ± 12.1 years. Among them, 15 (10.4%) had a WRA profile, including 10 (6.9%; 95% CI: 3.8–12.3) with occupational asthma and 5 (3.5%; 95% CI: 1.5–7.9) with work-aggravated asthma. Asthma was confirmed in 7 of the 15 carpenters suspected of having WRA through PEF variability measurement and spirometry. Simple and multiple logistic regression analyses identified a history of allergic rhinitis (aOR = 3.90; p = 0.033) and urticaria (aOR = 8.21; p = 0.002) as factors significantly associated with WRA.

Conclusions: The prevalence of WRA among carpenters in Parakou is not negligible, particularly occupational asthma. Awareness campaigns, education for carpenters, regular monitoring of working conditions, and systematic medical follow-up of exposed workers could help preserve their respiratory health.

Asthma is a common and heterogeneous respiratory disease with a complex pathophysiology, characterized by chronic inflammation of the bronchi, variable airway smooth muscle hyperresponsiveness, and bronchial hypersecretion [1]. Its prevalence is a major public health concern, affecting individuals of all ages, although it is more common in children and adolescents [2]. In 2019, nearly 262 million people worldwide were living with asthma, and approximately 455,000 deaths were attributed to the disease [3].

Asthma is the most common occupational respiratory disease, and nearly one quarter of adult cases are believed to be work-related [4]. It therefore represents a major cause of disability, with significant health and socio-economic consequences. Work-related asthma (WRA) refers to asthma symptoms that are associated with occupational exposure in individuals with pre-existing asthma, whether or not the condition is aggravated by work [work-aggravated asthma (WAA)], as well as occupational asthma (OA) [5].

The main occupational sectors affected by WRA include healthcare and early childhood education, the wood industry, the chemical, pharmaceutical, textile, and metallurgical industries, hairdressing, livestock farming, agriculture, baking, and painting [5]. In the wood industry, particularly in carpentry, workers are exposed not only to high concentrations of wood dust during cutting and sanding processes, but also to chemicals used in finishing, such as glues and varnishes. These exposures increase the risk of respiratory diseases, including asthma.

In Parakou, Benin, the prevalence of WRA in the workplace was reported to be 12.63% among bakers [6] and 11.29% among healthcare professionals [7].

In order to strengthen available data on WRA in Benin, this study was conducted to better assess the extent of this condition among carpenters, who represent a significant proportion of the workforce in the city of Parakou in northern Benin.

This was a cross-sectional, descriptive study with an analytical component, involving prospective data collection conducted from June 1, 2024, to September 30, 2024.

The study was conducted in carpentry workshops in Parakou, a city located in north-central Benin, 407 km from the economic capital, Cotonou. Parakou is the regional capital of northern Benin and had a population of 255,478 inhabitants in 2013, with a surface area of 441 km2.

The study population consisted of all certified carpenters and apprentices working in the city of Parakou who were geographically accessible. Professionals who were present on the day of the survey and who provided free and informed consent were included. For participants under 18 years of age, additional informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian.

The sample size was calculated using Schwartz’s formula:

where n is the sample size, p = 0.065, corresponding to the proportion of WRA among carpenters in Nigeria [8], q = (1 – p) = 0.935, α = 0.05 (type I error risk), corresponding to a Zα value of 1.96 from the standard normal distribution, and i = 0.05 (acceptable margin of error). After adding a 10% allowance for non-response, the minimum required sample size was 102 carpenters.

Due to the absence of a comprehensive list of carpenters in Parakou, the study was systematically proposed to all workers encountered in carpentry workshops on the days of data collection. In order to make sure that we can meet the carpenters at the workshops, we went there between 8 AM and 2 PM.

The dependent variable was the diagnosis of WRA. It was defined based on the worker’s asthma status according to the following criteria: i) No asthma: no history of asthma and no asthma attacks triggered by carpentry work; ii) OA profile: no history of asthma prior to starting carpentry work, with asthma attacks occurring in the workplace and improving during periods away from work; iii) WAA profile: a history of asthma prior to starting carpentry work, with worsening symptoms at work and improvement during periods of inactivity; iv) Asthma unrelated to carpentry: no history of asthma before entering the profession, with onset of asthma after starting carpentry work, but with symptoms triggered by environmental factors unrelated to the workplace.

The WRA clinical profile included workers with either OA or WAA. These participants subsequently underwent peak expiratory flow (PEF) variability measurement and spirometry to confirm the asthma diagnosis. PEF variability was considered significant when there was an increase of PEF of at least 20% after bronchodilator administration compared to the pre-bronchodilator value [9]. Spirometry findings were consistent with asthma when a post-bronchodilation forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) increased by at least 12% and at least 200 mL in absolute value.

The independent variables included sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, place of residence, marital status, and level of education); medical history and lifestyle habits; occupational factors (exposure to wood dust, varnishes and glues used, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), presence of a mechanical ventilation system); asthma symptoms (cough, chest tightness, shortness of breath, wheezing) during the previous 12 months; symptoms of allergic rhinitis; findings from the pleuropulmonary examination (respiratory rate, prolonged expiratory phase, decreased vesicular breath sounds, wheezing, snoring rales); findings from the ENT examination (anterior rhinorrhea, including quantity and appearance, nasal mucosal edema, and inferior turbinate hypertrophy); level of asthma control; results of respiratory function tests (PEF variability and spirometry); and the impact of asthma on carpenter’s quality of life.

Data were collected through anonymous individual interviews using a structured questionnaire. Asthma symptoms were assessed using the Occupational Asthma Screening Questionnaire-11 (OASQ-11) items [10]. Measurements of PEF variability and spirometry were performed only in workers with a WRA clinical profile.

Data collected using the survey forms were double-entered into Epi Data software version 4.7.0.0 and analyzed using R software version 4.4.1. Quantitative variables were described using means (standard deviations) or medians (with interquartile ranges), depending on their distribution. Qualitative data were described using frequencies and percentages. Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, was used to identify associations with the dependent variable. Crude odds ratios (cOR) with their 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-values were estimated using simple logistic regression. Variables with a p-value < 0.20 in bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression model to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aOR), their 95% CI, and the p-values. The level of significance was set at 5%.

The study protocol was submitted to the Local Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of the University of Parakou, which granted prior approval (REF: 776/2024/CLERB-UP/P/SP/R/SA). Authorizations were obtained from the Borgou Departmental Health Directorate and the Parakou Town Hall. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion, and data confidentiality was strictly respected.

Overall, of the 153 carpenters or apprentices that were identified in 117 workshops, 144 (94.1%) consented to participate in the survey. Of the participants, 103 (71.5%) were certified carpenters, and 41 (28.5%) were apprentice carpenters.

The mean age of the participants was 35.9 ± 12.1 years, with ages ranging from 16 to 60 years. The mean age was 41.5 ± 9.4 years among certified carpenters and 22.1 ± 4.1 years among apprentices, with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001). All participants were male. A total of 102 (70.8%) carpenters were under 45 years of age, and 69 (47.9%) had attained secondary-level education (Table 1).

Distribution according to sociodemographic characteristics of carpenters surveyed in Parakou in 2024 (N = 144).

| Variables | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (year) | ||

| < 45 | 102 | 70.8 |

| ≥ 45 | 42 | 29.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 88 | 61.1 |

| Single | 56 | 38.9 |

| Education level | ||

| Secondary | 69 | 47.9 |

| Primary | 48 | 33.3 |

| University | 4 | 2.8 |

| No schooling | 23 | 16.0 |

| Nationality | ||

| Beninese | 137 | 95.1 |

| Other nationality* | 7 | 4.9 |

| Ethnic group | ||

| Fon and related | 69 | 47.9 |

| Ditamari and related | 23 | 16.0 |

| Bariba | 21 | 14.6 |

| Nago and related | 19 | 13.2 |

| Others** | 12 | 8.3 |

*: Togolese (4), of Niger (1), Nigerian (1), Burkinabe (1); **: Dendi (4), Gourmantche (2), Peuhl (1), Haoussa (1), Lokpa (1), Mina (1), Ewe (1), Yoruba (1).

A personal atopy was found in 61 (42.4%) carpenters, including 42 (29.2%) with a history of allergic rhinitis and 23 (16.0%) with urticaria (Table 2). A family atopy was reported by 15.3% of them. A family history of asthma was reported by 24 (16.7%) carpenters, and 5 (3.5%) were known to have asthma before entering the profession.

Distribution of carpenters surveyed according to background (N = 144).

| Variables | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Personal atopy | 61 | 42.4 |

| History of allergic rhinitis | 42 | 29.2 |

| History of urticaria | 23 | 16.0 |

| History of allergic conjunctivitis | 20 | 13.9 |

| History of eczema | 2 | 1.4 |

| Family atopy | 22 | 15.3 |

| Personal history of asthma | 5 | 3.5 |

| Family history of asthma | 24 | 16.7 |

| Smoking | ||

| Non-smoker | 128 | 88.9 |

| Daily smoker | 13 | 9.0 |

| Occasional smoker | 2 | 1.4 |

| Ex-smoker | 1 | 0.7 |

In 94.4% (136/144) of cases, varnish was used as a finishing product, adhesives in 93.8% (135/144) of cases, and paints in 70.1% (101/144). Of the 144 carpenters surveyed, 103 (71.5%) worked in an environment considered confined, while 41 (28.5%) worked in a well-ventilated environment. Among them, 14.6% (21/144) always wore a mask, 19.4% (28/144) often wore one, 38.9% (56/144) sometimes wore one, and 27.1% (39/144) never wore one. There were 101 (70.1%) workers who wore surgical masks, whereas only 4 (2.8%) wore filtering facepiece particles (FFP3).

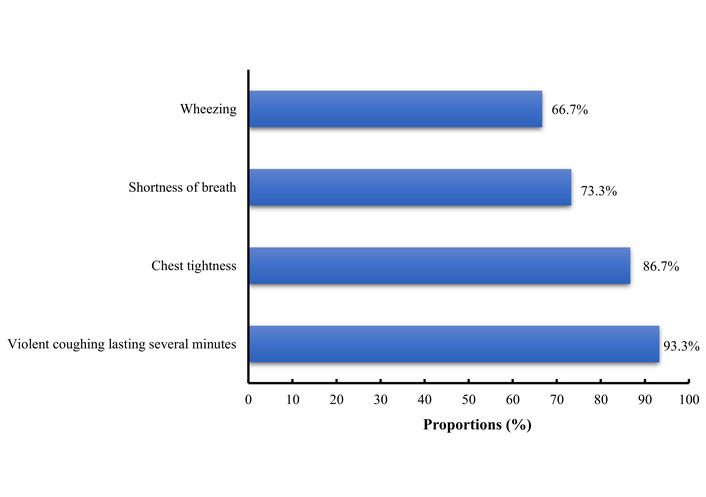

A WRA profile was identified in 10.4% of cases (15/144), including 10 cases of OA (95% CI: 3.8–12.3) and 5 cases of WAA (95% CI: 1.5–7.9), representing 6.9% and 3.5% of carpenters, respectively (Figure 1). Violent coughing fits lasting several minutes, and chest tightness were reported in 93.3% and 86.7% of cases, respectively (Figure 2).

Flowchart of carpenters surveyed from June to September 2024. PEF: peak expiratory flow.

Main respiratory symptoms suggestive of ALT among carpenters surveyed in Parakou in 2024 (N = 15).

The median duration of symptoms was 66 months [interquartile interval (IQR): 12–216] among certified carpenters and 24 months (IQR: 12–120) among apprentices. These symptoms were preceded by occupational rhinitis in all 15 workers with a WRA profile. After assessment of PEF variability and spirometry, asthma was confirmed in 7 (46.7%) of the 15 workers who presented clinical signs suggestive of WRA.

After simple and then multiple logistic regression, the factors associated with WRA were a history of allergic rhinitis (aOR = 3.90; p = 0.033) and urticaria (aOR = 8.21; p = 0.002) (Table 3).

Factors associated with work-related asthma among carpenters surveyed in 2024 in Parakou.

| Variables | n/N | % | Bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR | 95% CI | p-value | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | |||

| Age | 0.97 | 0.93–1.02 | 0.266 | - | - | - | ||

| Allergic rhinitis | ||||||||

| No | 6/101 | 5.9 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 9/43 | 20.9 | 4.19 | 1.41–13.3 | 0.011 | 3.90 | 1.13–14.5 | 0.033 |

| Urticaria | ||||||||

| No | 7/121 | 5.8 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 8/23 | 34.8 | 8.69 | 2.76–28.3 | 0.0002 | 8.21 | 2.24–31.9 | 0.002 |

| Family atopy | ||||||||

| No | 9/122 | 7.4 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 6/22 | 27.3 | 4.7 | 1.42–14.9 | 0.009 | 1.27 | 0.08–26.2 | 0.9 |

| Family asthma | ||||||||

| No | 9/120 | 7.5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 6/24 | 25.0 | 4.11 | 1.25–12.9 | 0.016 | 2.74 | 0.12–39 | 0.5 |

| Current smoker | ||||||||

| No | 13/129 | 10.1 | 1 | - | - | - | ||

| Yes | 2/15 | 13.3 | 1.32 | 0.33–5.31 | 0.48 | - | - | - |

| Seniority | 0.9 | 0.92–1.02 | 0.225 | - | - | - | ||

| Work environment | ||||||||

| Well-ventilated | 2/41 | 4.9 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Confined | 13/103 | 12.6 | 2.82 | 0.73–18.6 | 0.178 | 3.09 | 0.66–23.9 | 0.2 |

| Use of varnishes | ||||||||

| No | 1/8 | 12.5 | 1 | - | - | - | ||

| Yes | 14/136 | 10.3 | 0.8 | 0.13–15.6 | 0.8 | - | - | - |

| Use of paint | ||||||||

| No | 6/43 | 14.0 | 1 | - | - | - | ||

| Yes | 9/101 | 8.9 | 0.6 | 0.20–1.91 | 0.4 | - | - | - |

cOR: crude odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

None of the carpenters with a clinical profile of WRA had medical follow-up, and the costs associated with management were covered by the workers themselves. Asthma was well controlled in 53.3% (8/15) of cases, partially controlled in 26.7% (4/15), and uncontrolled in 20% (3/15).

Among the 103 certified carpenters surveyed, 6 (5.8%) were registered with the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), and 5 (83.3%) of them had paid their contributions.

Regarding the impact of the disease, it was considered to have a strong impact on productivity and periods of distraction in the same proportion, namely 13.3% (2/15). A moderate impact was reported in 40% (6/15) of cases for productivity, 26.7% (4/15) for periods of distraction, and 20% (3/15) for quality of social life.

This study, one of the few addressing this topic in sub-Saharan Africa, aims to strengthen the literature in Benin on the condition known as WRA. One of its strengths lies in the use of the validated OASQ-11 questionnaire for the diagnostic approach to WRA, as well as adherence to international recommendations for asthma diagnosis. The questionnaire was translated into local languages and tested to facilitate administration among carpenters who were not fluent in French. Measuring PEF variability and performing spirometry to confirm asthma were also major strengths of this study.

The main limitation was the lack of technical resources, which prevented the measurement of dust levels in workshops and the identification of other sensitizers and triggers in the carpenters’ work environment through appropriate tests (skin tests and bronchial provocation tests). It would also be appropriate to highlight the possibility of information bias. Indeed, the diagnosis of the clinical profile of WRA was based essentially on workers’ self-reported symptoms as collected through the questionnaire.

Some professionals refused to participate, either due to a lack of awareness or because previous surveys had not led to any improvement in working conditions. Others mistook the investigators for tax collection agents, which made them reluctant to take part in the survey or even led them to deny their own professional status.

The prevalence of a clinical profile suggestive of WRA among carpenters in Parakou was 10.4%. Laraqui Hossini et al. [11] in Morocco reported a prevalence of 14.5% among all carpenters in Marrakech. These figures are significant and highlight the need to strengthen diagnostic capacity and facilitate access to care for asthma patients in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as Benin. It is also important to raise awareness among woodworkers to change their behavior, particularly regarding the use of PPE, to reduce the frequency of attacks and limit the disease’s impact. In this study, less than one in five carpenters (14.6%) regularly wore masks, while more than a quarter (27.1%) never wore them. This may explain the significant impact on productivity reported by more than one-third (40%) of individuals with a WRA profile.

Regarding the two components of WRA, the prevalence was 6.9% for OA and 3.5% for WAA. Aguwa et al. [8] in Nigeria found a prevalence of 6.5% for OA among 591 carpenters. These results indicate that, in addition to the risk of disease exacerbation due to woodworking, exposure to wood dust and other occupational factors also increases the risk of developing asthma. This highlights the need to formalize this largely informal sector, raise awareness about registering workers with the NSSF for better care, and implement preventive measures to bring carpentry workshops up to standard.

The link between atopy and asthma development is well established. Atopy plays a major role in asthma onset [12]. In OA, however, symptoms are not solely related to atopic predisposition. Exposure to wood dust, poor ventilation, and lack of PPE also place workers at risk [13]. In this study, urticaria and allergic rhinitis increased the risk of WRA among carpenters. Gounongbe et al. [14] reported allergic rhinitis symptoms in nearly 20.5% of woodworkers in Parakou in 2014, while Laraqui Hossini et al. [11] found that rhinitis was indicative of WRA. Belabed et al. [15] reported that 61% of carpenters exhibited signs of rhinitis. This high frequency aligns with the fact that nearly three-quarters (72.9%) of the carpenters in their study did not use PPE.

Individuals with atopic predisposition should be informed and given special attention before starting high-risk occupations. It seems appropriate to implement reforms in this sector to facilitate the role of occupational health professionals in the prevention and management of work-related diseases such as WRA.

Seniority in the profession has also been identified by other authors as a factor increasing the risk of WRA among carpenters [8, 16]. Chronic bronchial inflammation associated with prolonged exposure to irritants and wood dust could explain this finding.

One in five carpenters with a WRA profile reported that asthma significantly affected their work performance, potentially leading to repeated absences and even dismissal if the link with asthma is not promptly recognized. Beyond this, the literature notes a deterioration in quality of life, which may lead to psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety and depression [5]. This condition compromises job retention and negatively impacts workers’ well-being. In this study, WRA was also found to moderately affect leisure activities in more than a quarter of carpenters with WRA. This may be exacerbated by the persistence of respiratory symptoms even outside the workplace. Indeed, it is known that symptoms occur both at work and outside the workplace when the disease worsens.

During our investigation, all carpenters with a clinical WRA profile or confirmed asthma through pulmonary function tests were referred to specialized care facilities, namely, pulmonology and occupational health clinics. Similarly, all carpenters were encouraged to register with the NSSF to facilitate occupational health care.

This prospective study of carpenters working in the city of Parakou showed that one in ten workers had a profile suggestive of WRA. The frequency of clinical findings consistent with OA was twice that of WAA. Measurement of instantaneous PEF variability and spirometry confirmed the diagnosis of asthma in nearly half of the carpenters with suggestive symptoms. The risk of having a clinical presentation suggestive of WRA was significantly higher in individuals with a history of allergic rhinitis or urticaria, as well as a family history of atopy or asthma, according to bivariate analysis. Symptomatic carpenters mainly reported a moderate impact of their symptoms on work performance and leisure activities. None of them were under medical supervision, and self-medication was common practice.

CI: confidence interval

IQR: interquartile interval

NSSF: National Social Security Fund

OA: occupational asthma

OASQ-11: Occupational Asthma Screening Questionnaire-11

PEF: peak expiratory flow

PPE: personal protective equipment

WAA: work-aggravated asthma

WRA: work-related asthma

The authors thank all the carpenters in Parakou, Benin, who participated in this study.

ME: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. SA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. IMC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. DA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft. APW: Validation, Writing—review & editing. GA: Validation, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The protocol was submitted to the Local Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research at the University of Parakou, which granted prior approval (REF: 776/2024/CLERB-UP/P/SP/R/SA). Authorizations were obtained from the Borgou Departmental Health Directorate and the Parakou Town Hall. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The anonymity and confidentiality of collected data were strictly maintained.

Informed consent to publication was obtained from all participants.

Data are kept confidential by the first author and can be made available upon reasonable request.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 255

Download: 12

Times Cited: 0