Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, SO17 1BJ Southampton, United Kingdom

2Department of Paediatric Allergy, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, SO16 6YD Southampton, United Kingdom

Email: melvin.qiyu@uhs.nhs.uk

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2476-960X

Affiliation:

2Department of Paediatric Allergy, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, SO16 6YD Southampton, United Kingdom

Affiliation:

2Department of Paediatric Allergy, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, SO16 6YD Southampton, United Kingdom

Affiliation:

3Department of Paediatrics, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, NW3 2QG London, United Kingdom

Affiliation:

4Faculty of Medicine, KU Leuven, 3000 Leuven, Belgium

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5710-5570

Affiliation:

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, SO17 1BJ Southampton, United Kingdom

2Department of Paediatric Allergy, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, SO16 6YD Southampton, United Kingdom

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1982-1397

Explor Asthma Allergy. 2026;4:1009106 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eaa.2026.1009106

Received: November 19, 2025 Accepted: January 08, 2026 Published: January 22, 2026

Academic Editor: Herberto J. Chong Neto, University of Parana, Brazil

The article belongs to the special issue Practical Issues in Pediatric Allergy

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is one of the most common food allergies in infancy, with a prevalence of up to 7.5%. However, accurate diagnosis in primary care remains difficult due to overlapping symptoms with common infant behaviours and limited access to specialist allergy testing. Consequently, CMA is frequently over diagnosed, leading to unnecessary elimination diets, nutritional deficiencies, and increased parental anxiety. This paper introduces the EATERS-X framework, an enhanced, structured approach to obtaining an allergy-focused clinical history (AFCH) that aims to improve diagnostic precision and clinical decision-making in CMA. The tool expands upon the traditional EATERS method—comprising Environment, Allergen, Timing, Exposure, Reproducibility, and Symptoms—by incorporating an additional element, X, denoting treatment and healthcare response. Through clinical scenarios, we demonstrate how EATERS-X can be applied to distinguish between IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated, and mixed-type CMA, including subtypes such as food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES). While EATERS-X provides a practical and systematic framework for history-taking, its effectiveness is dependent on clinician training and appropriate clinical interpretation. In addition, the framework has not yet undergone formal validation against gold-standard diagnostic tests such as oral food challenges. Future prospective studies should evaluate the diagnostic reliability, inter-observer consistency, and clinical impact of EATERS-X across different healthcare settings. Integration of the EATERS-X approach in primary care aligns with current BSACI and EAACI guidelines and promotes structured, evidence-based, and patient-centred care. Future research should focus on validating the framework’s diagnostic reliability and exploring its applicability across a wider spectrum of allergic conditions.

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is one of the most common food allergies in early childhood. The prevalence of CMA by one year of age is estimated to range between 1.8% and 7.5% [1]. Data from a UK birth cohort study revealed an adjusted incidence of CMA in children up to two years of age in the UK at approximately 2.4%, with non-IgE-mediated CMA accounting for half of diagnosed cases, around 1.7% [2]. However, there is a marked discrepancy between self-reported CMA and formally diagnosed cases, with diagnostic assessments indicating a much lower prevalence of just 0.6–1% [3, 4], compared to 16.1% based on parent reports and 11.3% from primary care records [4].

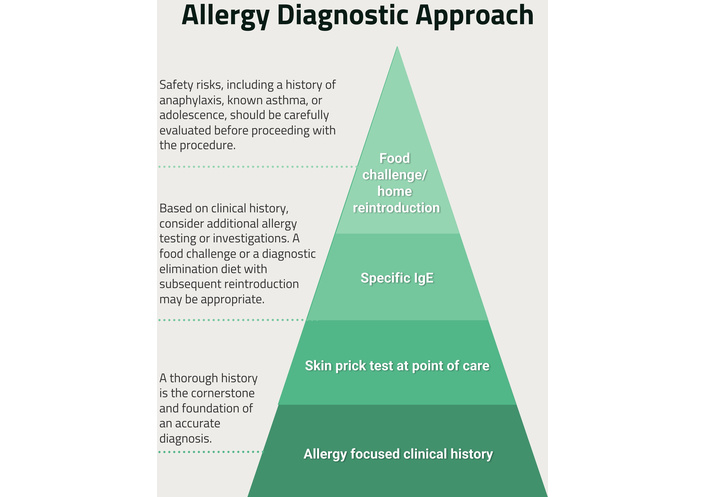

Accurate diagnosis of CMA relies on a high-quality allergy-focused clinical history (AFCH), which remains the cornerstone of food allergy assessment, particularly in primary care where access to diagnostic testing is limited [5]. Allergy tests are applied in a stepwise diagnostic approach based on the AFCH (Figure 1).

Allergy diagnostic approach for food allergies. This figure illustrates how EATERS-X aligns with a stepwise diagnostic approach, reinforcing that structured history-taking underpins decisions regarding testing, elimination diets, and referral. The pyramid emphasises that accurate AFCH precedes investigation and escalation, particularly in primary care settings.

Distinguishing between the various types of CMA can be challenging. This article explores different clinical presentations of CMA applying the EATERS-X tool, to support AFCH and provide clarity (Table 1).

Explanation of the EATERS-X tool.

| EATERS-X abbreviations | Explanation |

|---|---|

| E—Environment | Assess the reaction settings (home, restaurant, on holiday, party, childcare) to identify exposure risks. The majority of the allergic reactions in infancy happen during weaning when new foods are introduced. |

| A—Allergen | Identify the suspected allergen (e.g., cow’s milk, egg, peanut). Assess cross-reactivity or rare allergens for comprehensive evaluation. |

| T—Timing | Evaluate the time from exposure to symptoms. IgE-mediated reactions occur within minutes to two hours; non-IgE-mediated reactions are delayed, appearing hours to days later. |

| E—Exposure | Identify the exposure route—ingestion, skin contact, or inhalation. |

| R—Reproducibility | IgE-mediated allergies can occur on first contact, while non-IgE reactions typically develop or worsen with repeated exposure. FPIES may present as early as the first or second ingestion. |

| S—Symptoms | Document reaction severity, systems involved, and timing. IgE allergies cause acute hives, angioedema, or anaphylaxis, while non-IgE allergies present delayed gastrointestinal or skin symptoms, often with multisystem involvement. |

| X—Treatment | Treatment given, how carers and professionals responded to the reaction. |

FPIES: food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome.

The EATERS framework is a structured, user-friendly tool for diagnosing food allergies recommended by international guidelines [6]. It can be applied by any healthcare professional, regardless of clinical experience, and maps well to the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergies.

EATERS emphasises six key elements of the history found in all allergic reactions: Environment, Allergen, Timing, Exposure, Reproducibility, and Symptoms [6]. While the EATERS framework is effective in structuring the temporal and symptomatic characteristics of allergic reactions, it does not explicitly capture how symptoms evolve following treatment or healthcare intervention. In routine clinical practice, response to interventions such as antihistamines, acid suppression, elimination diets, or escalation to emergency care often provides critical diagnostic information. The addition of “X” (Extra/Rx) in EATERS-X formalises this overlooked dimension of the AFCH. By systematically capturing treatment response and healthcare interaction, EATERS-X enhances diagnostic discrimination between allergic and non-allergic conditions, improves recognition of disease severity, supports triage decisions, and facilitates earlier identification of red flags such as treatment-resistant symptoms or evolving IgE-mediated disease. By incorporating both parental and healthcare professional responses, EATERS-X reduces reliance on symptom reporting alone and introduces an internal severity check: reported symptom severity should align with the level of treatment and observation provided. This represents a qualitative advancement beyond the original EATERS framework, strengthening causal inference and pre-test probability assessment rather than merely extending the mnemonic.

EATERS-X is a practical tool for conducting quick and efficient AFCH in busy clinic settings. It can be applied broadly across allergy types—including IgE- and non-IgE-mediated allergies, adverse drug reactions, venom allergies, and various food allergies. However, previous validation of the EATER method focused solely on IgE-mediated food allergies [5]. Therefore, interpreting the collected history for other allergy types requires appropriate clinical guidance. For example, histories related to CMA could be assessed using diagnostic frameworks such as the Allen et al. [7] algorithm to guide further investigation and management.

CMA is classified into IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated, and mixed IgE/non-IgE-mediated types [5, 8]. IgE-mediated CMA involves rapid Type I hypersensitivity with mast cell degranulation, while non-IgE-mediated CMA arises from delayed Type IVb hypersensitivity driven by Th2 cells. Mixed IgE/non-IgE CMA combines immediate and delayed reactions [8].

IgE-mediated CMA is a Type I hypersensitivity reaction driven by IgE antibodies, which trigger mast cell degranulation and release mediators like histamine, causing immediate allergic responses [9, 10]. Diagnostic tests such as skin prick tests (SPT) and specific IgE measurements typically confirm the diagnosis.

Prevalence studies vary; the EuroPrevall study in Europe estimates a prevalence of 0.59% [11], while U.S. studies report rates as high as 1.6% [10]. Differences arise due to varying definitions and methodologies.

Presentation of IgE-mediated CMA is immediate, generally within 2 hours [12], and usually involves the skin, respiratory, and gastrointestinal systems [9]. Common symptoms are acute urticaria, angioedema, flushing, allergic rhino-conjunctivitis, acute bronchospasm, gastrointestinal spasm, and anaphylaxis [13] (see Table 2). IgE-mediated CMA typically presents in breastfed infants before they are 6 months old on direct exposure to cow’s milk during the introduction of solids or formula feeds [14].

Scenario 1: IgE-mediated CMA.

| EATERS-X abbreviation | Information from the history taking |

|---|---|

| E (Environment) | A 5-month-old infant was breastfed at home during routine feeding. Otherwise well, no eczema. |

| A (Allergen) | Cow’s milk protein in formula feed. |

| T (Timing) | Symptoms developed within 10 minutes of ingestion. |

| E (Exposure) | Orally given 30 mL of cow’s milk formula for the first time. |

| R (Reproducibility) | Often, the first known exposure is with no prior direct ingestion (although many will have had infant formula in the first 2 weeks of life to support the establishment of breastfeeding). |

| S (Symptoms) | Facial urticaria, angioedema, and coughing that resolved with a large vomit. |

| X (Extra/Rx) | Parents administered an antihistamine; emergency services were called. The paramedic assessed, and the child was observed in the emergency department for 4 hours. No further treatment given. |

CMA: cow’s milk allergy.

Non-IgE-mediated CMA is a cell-mediated immune response to cow’s milk proteins, primarily involving T-lymphocytes, eosinophils, and various cytokines [8]. In some cases, it is also associated with epithelial barrier dysfunction and increased intestinal permeability [10]. Its exact prevalence is unclear due to varying criteria and definitions, with self-reported cases often exceeding clinical diagnoses.

Non-IgE-mediated CMA typically presents with gastrointestinal symptoms that progress over time [14]. In the first 24 hours after exposure to an offending allergen, infants may exhibit acute vomiting and abdominal discomfort, often accompanied by persistent crying and unsettled behaviour. In other cases, symptoms may take longer to develop and take several days. Symptoms then may include intermittent vomiting, diarrhoea or constipation, abdominal discomfort, bloating, and sometimes the presence of blood in the stool. Occasionally, if unrecognised, this may lead to faltering growth, hypoalbuminaemia, and iron deficiency anaemia. Feeding difficulties are also commonly reported as presenting symptoms in children with non-IgE-mediated CMA [15].

Non-IgE-mediated CMA encompasses several distinct subtypes, including food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE), food protein-induced enteropathy (FPE), and food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP) [16].

FPIES is a part of non-IgE-mediated food allergies, though its precise mechanism remains unclear [17]. In acute presentations, symptoms typically appear within 1–4 hours, relatively soon rather than truly delayed, and primarily affect infants, characterized by severe gastrointestinal manifestations. The prevalence of FPIES varies globally, ranging from 0.015% to 0.7% [17], with an estimated rate of 0.006% in the United Kingdom [18]. Common triggers in children include rice/oats, meat, fish, and eggs, with milk being the most frequent cause [19].

Non-IgE-mediated cow’s CMA encompasses several subtypes, each presenting with distinct clinical features (Tables 3 and 4) [16]. FPIES (Table 5) typically manifests with repetitive vomiting and lethargy occurring 1 to 4 hours after ingestion of cow’s milk, and may progress to dehydration and shock in severe cases. EoE presents with feeding difficulties, vomiting, abdominal pain, and, in older children, dysphagia. FPE is characterized by chronic diarrhoea, malabsorption, and faltering growth [16]. FPIAP commonly presents in infants with blood-streaked stools but typically without significant systemic symptoms [16].

Scenario 2: non-IgE CMA in a breastfed infant.

| EATERS-X abbreviation | Information from the history taking |

|---|---|

| E (Exposure) | Breastfeeding a 3-week-old infant. |

| A (Allergen) | Cow’s milk protein via maternal diet is secreted in breast milk. |

| T (Timing) | Increasing symptoms over several weeks. |

| E (Environment) | An exclusively breastfed infant with a mother who consumes dairy regularly. |

| R (Reproducibility) | Symptoms improved with maternal dairy exclusion and reappeared on accidental reintroduction. |

| S (Symptoms) | Persistent vomiting after feeds, diarrhoea, abdominal bloating, and blood-streaked stools. |

| X (Extra/Rx) | Sought advice from GP who made a referral to paediatric dietician to support breastfeeding on maternal exclusion diet. |

CMA: cow’s milk allergy.

Scenario 3: non-IgE CMA in a formula-fed infant.

| EATERS-X abbreviation | Information from the history taking |

|---|---|

| E (Environment) | 6-week-old formula-fed infant. |

| A (Allergen) | Cow’s milk protein in infant formula. |

| T (Timing) | Increasing symptoms over several weeks. |

| E (Exposure) | Oral exposure by formula feed. |

| R (Reproducibility) | Symptoms improved with a change to an extensively hydrolysed formula (EHF) and returned when the CM formula was reintroduced 4 weeks later as a therapeutic trial. |

| S (Symptoms) | Persistent vomiting after feeds, unsettled, poor sleep, unable to be laid flat, loose, frequent stools, and atopic dermatitis. |

| X (Extra/Rx) | Primary care prescribed EHF and monitored improvement of symptoms, undertaking a reintroduction 4 weeks later to confirm the diagnosis. |

CMA: cow’s milk allergy.

Scenario 4: non-IgE CMA-FPIES.

| EATERS-X abbreviation | Information from the history taking |

|---|---|

| E (Environment) | Breastfed infant at 6 months old when cow’s milk was introduced directly (*). |

| A (Allergen) | Cow’s milk protein in formula and milk in solid foods. |

| T (Timing) | Symptoms occurred 2 to 4 hours after consuming cow’s milk. |

| E (Exposure) | Three oral direct exposures. Mum had been breastfeeding with cow’s milk in her diet since birth, with no symptoms; they only started when direct cow’s milk was introduced to the child. |

| R (Reproducibility) | Three episodes of increasing severity, symptoms improved with CM exclusion (home reintroduction is not recommended if FPIES—if suspected, refer for specialist advice). |

| S (Symptoms) | Persistent vomiting after feeds, effortless and profuse, the child became pale and floppy, with delayed diarrhoea 12–18 hours later on 2 occasions. No fever or rash on any occasion. |

| X (Extra/Rx) | First episode observed at home, thought may have had gastroenteritis. Second episode, contacted GP for advice. In the third episode, the child became floppy and unresponsive and presented to the emergency department. An oral fluid trial was performed, and observed. Diagnosis made by staff, although the parent had suspicions based on an internet diagnosis. |

*: FPIES also occurs in formula-fed infants, where symptoms can be protracted. CMA: cow’s milk allergy; FPIES: food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome.

Diagnosis is often delayed due to nonspecific symptoms mimicking disorders of gut-brain interaction, previously known as functional gastrointestinal disorders, leading to repeated physician visits [16]. Limited diagnostic tools, unfamiliarity with guidelines, and reliance on elimination diets further complicate timely diagnosis [20].

Mixed CMA encompasses both IgE- and non-IgE-mediated allergic responses, and some infants have both. Immediate reactions are attributed to IgE, whereas delayed reactions involve T cells and eosinophils [21]. Although the presence of mixed IgE and non-IgE symptoms in CMA patients is acknowledged in literature and clinical practice, a clear definition remains unspecified. Prevalence data for mixed CMA are scarce, likely due to the overlapping symptoms between IgE- and non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergies.

A clinically important phenomenon is the transition from non-IgE-mediated CMA to IgE-mediated allergy, often referred to as “switched CMA” [22]. Mechanistically, this represents progression from a predominantly cell-mediated immune response to IgE sensitisation with subsequent clinical reactivity, rather than asymptomatic sensitisation alone. Prolonged avoidance of cow’s milk protein—particularly in early infancy—may increase the risk of IgE sensitisation, with immediate allergic reactions occurring on re-exposure. Clinical predictors include persistent non-IgE symptoms, prolonged elimination diets, and co-existing atopic dermatitis [22, 23]. Recognition of this transition is essential to guide safe reintroduction and ongoing monitoring.

Emerging evidence supports baked milk as a safe and effective form of immunotherapy for CMA, with the potential to promote tolerance [24]. In patients who can tolerate baked milk, this strategy may also help prevent the development of ‘switched CMA’. Rarely, IgE-mediated CMA may transition to non-IgE forms like FPIES, with symptoms shifting as IgE levels decline. This bidirectional relationship suggests complex immune mechanisms linking IgE and non-IgE milk allergies [25].

A prospective CMA study [26] identified patients with positive specific immunoglobulin E (sIgE) and SPT who experienced intermediate (1–24 hours) and/or delayed (24–72 hours) reactions after milk exposure (Table 6). Intermediate symptoms included vomiting, diarrhoea, dermatitis, and wheezing, while delayed reactions often involved dermatitis, constipation, and wheezing.

Scenario 5: mixed IgE and non-IgE-mediated CMA.

| EATERS-X abbreviation | Information from the history taking |

|---|---|

| E (Exposure) | 7-month-old infant receiving cow’s milk formula for the first time. |

| A (Allergen) | Direct Cow’s milk protein (IgE) and also indirect through breast milk (non-IgE). |

| T (Timing) | Immediate perioral erythema and vomiting within 10 minutes of CM formula; eczema flare and increased vomiting and loose stools 12–48 hours later. |

| E (Environment) | Breastfed infant with generalised atopic dermatitis and chronic gut symptoms from 6 weeks old. |

| R (Reproducibility) | Immediate symptoms recurred with subsequent direct cow’s milk exposure. |

| S (Symptoms) | Acute urticaria and vomiting (IgE) followed by delayed eczema worsening and diarrhoea (non-IgE). |

| X (Extra/Rx) | The previous skin prick test was positive. Skin and gut symptoms cleared when the mother removed milk from her own diet (non-IgE). |

CMA: cow’s milk allergy.

Another subgroup exhibited symptoms like cough, wheezing, atopic dermatitis, and diarrhoea over 20 hours post-exposure, with IgE sensitization frequently linked to atopic dermatitis [27].

Atopic dermatitis, characterized by a defective skin barrier, increases allergen permeability, facilitating sensitization to food allergens, particularly through damaged skin exposed to environmental allergens [28].

CMA remains one of the most prevalent food allergies in early childhood, yet accurate diagnosis, particularly in primary care settings, remains a considerable challenge.

The BEEP trial highlighted significant overdiagnosis of CMA in the community: 16.1% had parental reports of milk hypersensitivity, 11.3% had hypersensitivity recorded in primary care, and 8.7% received prescriptions for hypoallergenic formula—yet only 1.4% were formally diagnosed with CMA [4]. Diagnosing CMA in primary care is challenging because of limited access to allergy testing [4] and symptoms that commonly overlap with those of unsettled infants [29].

The EATERS-X framework presents a structured, practical tool that supports clinicians—particularly non-specialists—in navigating the complex diagnostic landscape of CMA (Table 7). By emphasizing exposure, allergen identification, timing, environment, reproducibility, symptoms, and treatment (or healthcare response), this approach enables a comprehensive AFCH that aligns with the latest European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) guidance. This is especially valuable in differentiating between IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated, and mixed-type CMA, each of which presents with distinct pathophysiology and timelines and requires a different management approach.

Simplified EATERS-X history: focus on different categories of CMA.

| Category | IgE-mediated CMA | Non-IgE-mediated CMA | Mixed IgE-mediated CMA | FPIES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | Infants < 12 months | Infants < 6 months | Infants < 12 months, often with eczema | Infancy, usually < 12 months |

| Feeding | Breast or formula fed | Breast or formula fed | Formula or solids | Formula or solids |

| Allergen | Cow’s milk protein | Cow’s milk protein (direct or via breast milk) | Cow’s milk protein | Cow’s milk protein |

| Timing | Immediate (< 2 hours) | Delayed (up to 48 hours) | Immediate and/or delayed | 1–4 hours (up to 6 hours) |

| Exposure | Direct ingestion | Direct or indirect (breast milk) | Direct ingestion | Direct ingestion |

| Reproducibility | Symptoms resolve on exclusion and recur on re-exposure | Symptoms resolve on exclusion and recur on re-exposure | Symptoms resolve on exclusion and recur on re-exposure | Symptoms worsen with repeated exposure; re-challenge supervised |

| Symptoms | Acute allergic symptoms | Delayed gastrointestinal and skin symptoms | A combination of acute and delayed symptoms | Severe gastrointestinal ± systemic symptoms |

| Extra (Treatment) | Managed as an IgE allergy | Managed by dietary exclusion | Managed by dietary exclusion | Acute management; specialist follow-up |

CMA: cow’s milk allergy; FPIES: food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome.

This table outlines the simplified clinical presentations of CMA, categorized using the EATERS-X allergy-focused history framework. A detailed table of explanation of each domain can be found in Table S1.

Non-IgE-mediated CMA, in particular, poses unique diagnostic difficulties due to its delayed symptom onset and presentation across a spectrum of gastrointestinal conditions, from FPIES to controversial entities like food protein-induced dysmotility disorders [16]. This article also draws attention to the phenomenon of “switched CMA”, where patients initially presenting with non-IgE-mediated reactions may later develop IgE-mediated responses, further underscoring the need for structured history-taking and ongoing reassessment [16].

Using specific IgE or SPT for cow’s milk protein alone provides limited sensitivity and specificity without a thorough AFCH [5]. Specific IgE food allergen panels have poor sensitivity, and multiplex IgE technologies should be requested cautiously and interpreted only by allergy specialists, as they require expert knowledge to avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary dietary restrictions.

Importantly, many children with suspected CMA undergo dietary elimination without formal diagnostic confirmation, potentially leading to unnecessary dietary restrictions, nutritional deficiencies, and increased parental anxiety. The application of the EATERS-X framework in primary care could facilitate earlier recognition of red flags, promote timely management or referral to allergy services, and reduce unwarranted exclusion diets.

Once a diagnosis is established using this approach, management of each CMA subtype can be effectively guided by established national and international guidelines, including those from the British Society for Allergy & Clinical Immunology (BSACI) and EAACI. In cases where the allergy status remains uncertain, the EAACI recommendations for both IgE- and non-IgE-mediated food allergies provide valuable direction for further investigation and clinical decision-making [5, 16].

The EATERS-X framework offers several strengths, notably its structured and standardised approach to allergy-focused history-taking, which reduces subjective interpretation and supports more reproducible and clinically precise diagnosis of CMA across IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated, and mixed presentations. The inclusion of treatment and healthcare response (“X”) strengthens causal inference by linking symptom evolution to interventions, particularly in settings with limited access to objective testing. However, the framework has not yet undergone formal validation to determine its diagnostic accuracy, inter-observer reliability, or impact on clinical outcomes. Importantly, EATERS-X is intended to complement—not replace—objective testing and guideline-based diagnostic pathways.

Although the mnemonic is already a useful teaching aid, the future validation of EATERS-X should be an integral component of its proposed clinical utility rather than an adjunct consideration. Prospective, multi-centre studies across a range of healthcare settings are required to evaluate its diagnostic accuracy against reference standards such as oral food challenges and expert-confirmed diagnoses. Key outcomes should include sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and inter-observer reliability across clinicians with varying levels of allergy expertise. In addition, studies should assess whether inclusion of the “X” component improves discrimination between allergic and non-allergic conditions compared with the original EATERS framework alone. Secondary outcomes may include impact on referral rates, reduction in unnecessary elimination diets, nutritional outcomes, and parental anxiety. Such validation would clarify whether structured capture of treatment response meaningfully enhances diagnostic precision and clinical decision-making.

CMA is frequently over diagnosed in community settings, largely due to nonspecific symptoms and limited access to allergy diagnostics. The EATERS-X framework offers a practical and systematic method to improve diagnostic accuracy by guiding structured history-taking.

By reducing subjective interpretation and standardising key diagnostic variables, EATERS-X provides an unbiased and reproducible approach that enhances precision in differentiating IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated, and mixed forms of CMA.

When applied within guideline-based care pathways, EATERS-X has the potential to significantly reduce unnecessary elimination diets, optimise referral decisions, and improve patient-centred outcomes. While further validation is required, this framework represents a robust and scalable advance in the accurate diagnosis of CMA, particularly in primary care and non-specialist settings.

AFCH: allergy-focused clinical history

BSACI: British Society for Allergy & Clinical Immunology

CMA: cow’s milk allergy

EAACI: European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

EHF: extensively hydrolysed formula

EoE: eosinophilic oesophagitis

FPE: food protein-induced enteropathy

FPIAP: food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis

FPIES: food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome

SPT: skin prick tests

The supplementary table for this article is available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1009106_sup_1.pdf.

MLQ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. IR, AMON, and SAD: Resources, Writing—review & editing. MG and RM: Writing—review & editing. MEL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2026.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1079

Download: 16

Times Cited: 0

Martín Bedolla-Barajas ... Jaime Morales-Romero