Affiliation:

1Department of Chemical Pathology, School of Medical Laboratory Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Sokoto 2346, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1875-7098

Affiliation:

2Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Nigerian Defence Academy, Kaduna 2109, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2375-6375

Affiliation:

3Department of Immunology, School of Medical Laboratory Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Sokoto 2346, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3657-7541

Affiliation:

4Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Sokoto 2346, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2435-9870

Affiliation:

5Interdisciplinary graduate program in Immunology, University of Iowa, Iowa, IA 52242, United States

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0855-1005

Affiliation:

6Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan 200132, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1406-8359

Affiliation:

7Integrated Germline Biology Group Laboratory, Osaka University, Osaka 565-0871, Japan

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6807-7248

Affiliation:

8Department of Medicine and Surgery, Faculty of Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Nigeria Enugu Campus, Enugu 400241, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0464-4167

Affiliation:

9Department of Medical Microbiology, University College Hospital, Ibadan 200212, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6247-5840

Affiliation:

10Department of Public Health and Maritime Transport, Faculty of Medicine, University of Thessaly, 38221 Volos, Greece

11Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Chrisland University, Abeokuta 110101, Nigeria

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3809-4271

Affiliation:

12Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SIMAD University, Mogadishu 252, Somalia

Email: momustafahmed@simad.edu.so

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5991-4052

Explor Immunol. 2025;5:1003202 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2025.1003202

Received: January 20, 2025 Accepted: June 10, 2025 Published: July 11, 2025

Academic Editor: Nitin Saksena, Victoria University, Australia

The global socioeconomic and health impacts of microbial diseases cannot be overemphasized. The emergence of the coronavirus in 2019 and the ongoing threat of infectious diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and hepatitis, remind us of the impact these infections have on economic stability and global health. Gaps in the treatment of microbial infections and their contribution to increased mortality necessitate holistic and long-term solutions, as opposed to antibiotics, which were previously relied upon. Immunotherapy is becoming increasingly promising for the treatment of microbial infections. This study reviews recent advances in immunotherapeutic strategies, particularly cytokine-based therapies, adoptive cell therapy, monoclonal antibodies, and immune checkpoint inhibitors, for the control of antimicrobial resistance. New inventive approaches, such as chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy and mucosal-associated invariant T cells, have been discussed in the context of bacterial and viral infections, highlighting promising results from clinical trials and addressing the challenges of toxicity, immune evasion, and therapy resistance that are inherent in these diseases. Future priorities include optimizing combination therapies and exploring new immunomodulatory targets to improve the effectiveness of these interventions in treating antimicrobial resistance and other infectious diseases.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the most significant public health challenges of the twenty-first century, driven by genetic mutations that diminish the efficacy of antimicrobial drugs [1]. Emerging almost immediately after the introduction of antimicrobials, AMR has accelerated in recent years, posing a serious threat to modern medicine [2]. In 2019, bacterial AMR was directly responsible for approximately 1.27 million fatalities worldwide and contributed to over 5 million deaths [3, 4]. The number of deaths directly linked to AMR is expected to increase dramatically, with an estimated 39 million deaths between 2025 and 2050, corresponding to almost three deaths per minute [5]. The emergence of drug-resistant pathogens has spurred unwavering scientific interest in the development of new antimicrobials, leaving a dwindling arsenal against bacterial and viral diseases [6]. However, the misuse and overuse of these drugs have expedited the emergence of new resistant strains, rendering once-treatable infections increasingly untreatable. Resistance compromises treatment efficacy, necessitating the urgent development and implementation of novel strategies to counteract this global dilemma [1]. Clinically significant viral DNA and RNA diseases, such as HIV, hepatitis C, and SARS-CoV-2, and bacterial infections, such as gram-positive pathogens (e.g., Staphylococcus and Streptococcus spp., Mycobacterium spp.) and gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Actinobacter spp.), exemplify the grave concerns posed by AMR. Diverse resistance patterns exhibited by viruses and bacteria to currently available antimicrobial agents have become a critical public health issue, complicating the diagnosis and treatment of an expanding range of diseases that were once treated with conventional therapies [2]. This underscores the need for robust preventive surveillance and control measures.

Antimicrobial compounds have been employed since ancient times, and natural extracts have been used historically for their therapeutic properties [7]. Numerous antibacterial drugs have been produced since Fleming discovered penicillin in 1929, which had a significant impact on global human mortality and health [8]. In recent decades, microbial pathogens such as HIV-1 and HIV-2, the 1918 influenza virus, the Middle East respiratory disease coronavirus, and SARS-CoV-2 have repeatedly emerged in human populations from domestic and wild animal reservoirs [9]. These emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases have exposed vulnerabilities in healthcare systems, particularly in underdeveloped regions, and emphasize the urgent need to develop innovative therapeutic strategies against them. In pursuit of universal health coverage and improved life expectancy, a novel treatment modality is revolutionizing healthcare. Immunotherapy offers an innovative solution, particularly for immunocompromised patients, by enhancing host defense against opportunistic infections. Recent advancements in immunotherapeutic strategies have proven instrumental in managing infectious diseases that affect humans. These approaches are pivotal in the broader context of disease prevention and control in humans, with a wider approach to One Health.

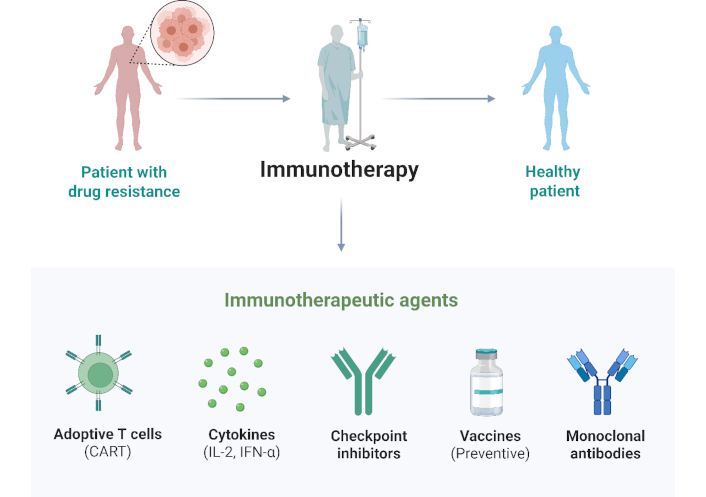

Immunotherapy is becoming increasingly popular for treating various diseases by efficiently modulating the host’s innate and adaptive immune responses, thereby assisting in the management of several harmful microbial diseases [10]. These agents have diverse mechanisms of action, ranging from enhancing host immunity [cytokine therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and vaccines], targeting pathogenic determinants (monoclonal antibodies), and modifying immune cells [invariant killer T cells (iNKTs), mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAITs), and adoptive T cell therapy], which shows a promising prospect in the fight against microbes. This review explores the recent advances, challenges, and future perspectives of immunotherapeutic strategies for clinically important bacterial and viral diseases. By analyzing the current state of the field and identifying areas for further research, we hope to shed light on the role of immunotherapy in combating the growing threat of AMR and new infectious illnesses (Figure 1).

Conceptual pathway of immunotherapy. IFN-α: interferon-α. Created in BioRender. Ahmed, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/5vsqipu

Cytokines are small proteins that are essential for cell signaling within the immune system. These proteins play critical roles in the regulation of immune responses, inflammation, and hematopoiesis [11]. The primary cytokines used in these therapies include interleukins (ILs), interferons (IFNs), tumor necrosis factors (TNFs), and colony-stimulating factors (CSFs). Cytokine-based therapies are powerful tools for treating bacterial and viral diseases. Despite challenges such as toxicity and delivery issues, recent advances and combination strategies offer promising solutions. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) has been shown to be effective in stimulating the activation and proliferation of granulocytes and macrophages, thus boosting the immune response against bacterial pathogens. Currently, it is undergoing clinical trials for sepsis and bacterial pneumonia with promising initial outcomes [12]. For instance, an in vivo study revealed that a newly developed albumin-fused GM-CSF exhibited improved biostability and increased dendritic cell populations, which are key to initiating a strong immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) [13]. Moreover, recombinant human interleukin-2 (rhIL-2) has been tested as adjunctive immunotherapy in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) to improve treatment efficacy and shorten treatment duration [14]. Additionally, the cytokine IL-7, which supports immune hematopoiesis, has been evaluated in several clinical trials for treating lymphopenia in patients with sepsis suffering from excessive inflammation, known as cytokine storms [15].

IFN-based therapies have shown significant promise in the treatment of viral diseases. IFN-α has been extensively used to treat chronic viral infections such as hepatitis B and C [16]. Recent clinical studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in significantly reducing viral load and improving liver function, thereby offering substantial therapeutic benefits. IFN-β, traditionally used in the management of multiple sclerosis, is currently being investigated for its potential use in treating COVID-19 [17]. Early clinical trials have indicated that IFN-β may reduce viral replication and modulate inflammatory responses, providing a promising therapeutic avenue for SARS-CoV-2 infections. Similarly, IL-7 has emerged as a potent therapeutic agent for viral infections, primarily because of its ability to enhance T cell recovery and function. Current clinical trials are evaluating its efficacy in treating HIV and post-viral fatigue syndromes, suggesting broader applications in viral immunotherapy [18].

The efficacy of cytokine therapies can be significantly enhanced by combining them with other therapeutic strategies. For example, the combination of IFN-α with ribavirin has substantially improved the treatment of hepatitis C, demonstrating the synergistic effects of cytokines and antiviral combinations [19]. Similarly, IFN-β combined with remdesivir has been investigated for its synergistic potential against SARS-CoV-2, presenting a promising therapeutic strategy for COVID-19 [20–22]. Furthermore, cytokines are paired with monoclonal antibodies or ICIs to amplify antitumor and anti-infective responses. These combinations are being examined in various clinical settings to optimize immunotherapy effectiveness. IL-6 inhibitors, such as tocilizumab, have also shown potential in managing severe bacterial infections by regulating inflammatory responses [23]. This highlights the therapeutic versatility of cytokine inhibitors in the treatment of complex bacterial diseases.

However, cytokine therapies present several challenges. High doses of cytokines can result in severe side effects, including systemic inflammation, cytokine release syndrome, and organ damage. Efficient delivery of cytokines to target tissues is challenging because of their rapid degradation and off-target effects. Additionally, prolonged cytokine use can lead to immune tolerance or resistance, diminishing their efficacy over time [24]. Possible solutions to these challenges include the development of nanoparticle-based delivery systems to protect cytokines from degradation and enhance their targeted delivery. These advanced delivery systems have the potential to significantly improve the efficacy of cytokine therapy. Efforts are also being made to design modified cytokines with enhanced stability and reduced toxicity. These engineered cytokines offer promising solutions to the challenges associated with cytokine therapies [25]. Ongoing research is aimed at determining the optimal dosing and timing of cytokine administration to maximize efficacy while minimizing the side effects. Optimizing these regimens is crucial for improving therapeutic outcomes. Additionally, combining cytokines with other immunomodulatory agents or therapies can enhance their efficacy and reduce the required dose, thereby mitigating side effects. This combination approach offers a promising strategy to overcome the limitations of current cytokine therapies [26]. Continued research and clinical trials are essential to fully harness the potential of cytokines for the treatment of infectious diseases.

Over the years, ICIs have shown remarkable efficacy in treating hematological malignancies and solid tumors. Checkpoint inhibition therapy utilizes monoclonal antibodies to disrupt the interactions between immunosuppressive receptors and their ligands. They primarily target proteins such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM3), and programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) [27], thereby improving effector T cell activation. However, their use in the treatment of microbial diseases, including HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and HCV, is poorly understood [28].

One of the unique features through which several chronic viral infections, such as HIV, hepatitis, and SARS-CoV-2, bypass immune responses is T cell exhaustion, resulting from the loss of T-cell effector function [29]. In addition, infectious agents possess pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [30]. Understanding the function of immune checkpoint molecules is crucial for reversing T cell exhaustion and mounting strong immune responses. Blockade of PD-1 has prompted T cell exhaustion to be redeemable via restoration of CD8+ T cell function by reducing the viral load in a murine model of induced chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis viral infection [31]. Cao et al. [32] demonstrated that the activity of HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in the peripheral and intrahepatic niches could be boosted by inhibiting the CTLA-4 checkpoint molecule in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Nonetheless, PD-1 inhibition can improve host immune alertness by promoting the production of IFN-γ in HIV- and HBV-specific cytotoxic T cells [33]. However, in preclinical studies, blocking PD-1 activity in vitro or ex vivo has been shown to potentiate latent HIV reversal [34, 35]. Another murine study indicated a potential adjuvant role for anti-CTLA-4, as CTLA-4 blockade during HIV immunization in mice led to increased CD4+ T cell activation, expansion of HIV-specific follicular helper T cells (Tfh), altered HIV-specific B-cell responses, and significantly increased anti-HIV antibodies with higher avidity and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity [36]. In addition, only three published studies on checkpoint inhibitors have focused on people living with HIV in the absence of malignancy and antiretroviral therapy. Of these, two were abruptly dismissed owing to toxicities and complications in the study population [27]. These immune-related adverse effects pose a major setback to the clinical use of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. In the case of COVID-19, several studies have suggested the benefits of ICI therapy [37]. Clinical trials on the safety and efficacy of ICIs in COVID-19 patients are still being explored [38], with no published results validating ICIs’ antiviral properties.

MTB remains a public health concern among all clinically important bacterial infections. ICIs have not been effective against tuberculosis (TB) in recent years. A group of researchers using a 3D microsphere model of human TB indicated that PD-1 inhibition promotes MTB growth and survival by enhancing cytokine production and TNF-α levels [39]. In a recent case report on a child, active TB development was correlated with an inherited PD-1 deficiency [40]. The emergence of TB has also been reported in patients with cancer who receive anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy [41]. To resolve this, combining ICIs with other treatment regimens could potentially curb TB pathogenesis and improve patient outcomes [29]. In a previous study, the combination of antibodies against LAG-3, CTLA-4, and TIGIT exhibited an additive effect on stimulating cytokine production by HIV-specific T cells. However, combinations with anti-PD-1 therapy did not yield the same outcomes [42]. In the treatment of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated tumors, different clinical trials have emphasized the clinical importance of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. First, a phase Ib clinical trial (NCT02054806) of pembrolizumab documented a partial remission (PR) in seven of 27 patients and stable disease in 14 patients with recurrent or metastatic NPC after a 20-month follow-up, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 25.9% [43]. In another clinical trial, camrelizumab (NCT02721589 and NCT03121716) was used both as a mono and combination therapy with chemotherapeutic agents (gemcitabine + cisplatin) in similar patients, yielding an ORR of 34% in the monotherapy group and an impressive 91% in the combination therapy group [44]. Recent findings also indicate the significant impact of avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 agent, on EBV-positive cases (NCT02335411) [45].

Several limitations affect the clinical use of ICIs, including safety due to immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and immune checkpoint expression on other immune cell types, such as gamma delta T cells, Tregs, NK cells, and monocytes [27, 46]. Other immune checkpoint molecules, such as A2AR, B7-H4, BTLA, KIR, NOX2, HO-1, and SIGLEC7 [47], could be extensively explored for the treatment of acute and chronic microbial infections, in addition to the commonly explored immune checkpoints. Given the impact of microbial diseases on global health, exploring the interactions between gut microbiota and microbial infections is of utmost importance. Reports have shown that the gut microbiota also has specific characteristics that improve the therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapeutic drugs in various cancers [48]. Optimizing the usefulness of fecal microbiota transplantation can help enhance several immune-related limitations of ICI clinical use [49]. Therefore, exploring the beneficial role of gut microbiota in immunotherapy for bacterial and viral infections is crucial for achieving complete patient remission outcomes, especially as an adjunctive therapy to enhance the efficacy of ICIs [49]. Ongoing research is focused on the development of ICIs with higher immunity profiling using gut microbiota-assisted technology.

The effectiveness and efficacy of vaccines against viral and bacterial infections can be enhanced by adding adjuvants. Therefore, adjuvants are important in vaccine production. They are usually added to bolster immune responses and improve protection against disease. To achieve this, it is necessary to understand the different types of adjuvants and their mechanisms of action. Adjuvants are proteins or polysaccharides, such as tiny substances in vaccines, that facilitate the elicitation of robust immune responses in inactivated vaccines and may have lower immunogenicity than live-attenuated or whole-killed vaccines [50]. Adjuvants are classified into several classes based on their mode of action and composition. The most widely used adjuvant is aluminum salt, which has been used for more than seven decades. It functions by eliciting local immune responses that enhance antigen presentation [51]. Other classes of bacterial adjuvants, such as lipopolysaccharides and toxins, effectively stimulate immune responses. Bacterial toxins have been studied as effective adjuvants that can improve mucosal immune responses [52, 53]. Unlike traditional vaccines that rely on external adjuvants, mRNA vaccines function as self-adjuvants by stimulating innate immune receptors. The single-stranded RNA in these vaccines is recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), triggering a strong immune response [54]. This inherent adjuvant-like property enhances antigen presentation and cytokine production, leading to potent and durable immune responses. The success of mRNA vaccines, particularly in combating the COVID-19 pandemic, underscores their transformative role in vaccinology [55]. Moreover, advancements in lipid nanoparticle (LNP) formulations not only aid in mRNA delivery but also contribute to immunostimulatory effects, further optimizing the efficacy of vaccines.

Recent adjuvants, such as CpG motifs, precisely target immune cells to enhance the immune response by mimicking bacterial DNA. Matrix-M is included in the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine, which boosts the immune system by combining lipids and saponins [51]. Another special adjuvant, MF59, used in the influenza vaccine, boosts the immunological response using a distinctive formulation that enhances antigen delivery and immune cell absorption [56]. Adjuvants work by provoking immunological responses at the innate level, which then influence or steer the adaptive immune system. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) are activated, and cytokines are produced by targeting PRRs on immune cells. This mechanism enhances vaccine antigen recognition and boosts a powerful, targeted, and focused immune response [52, 53]. The incorporation of adjuvants is vital in vaccine production, especially for certain diseases for which conventional vaccines do not offer effective and sufficient immunity. Adjuvants offer several benefits in vaccine production but must be used with caution to reduce potential side effects.

Current developments in adjuvants have substantially improved the prevention of infectious diseases and led to the production of efficient vaccines that offer robust and long-lasting immune responses. For example, TLR agonists, such as monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL), are a potential class of adjuvants that activate innate immunity, thereby enhancing the immune response against viral antigens [57]. They have been used in hepatitis B and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, substantially improving both antibody and T cell responses [57]. Similarly, TLR7/8 agonists, such as imiquimod, are promising adjuvants in HIV and influenza vaccines that evoke a strong cellular immune response, thereby making them efficient in producing a powerful and long-lasting immune response [57].

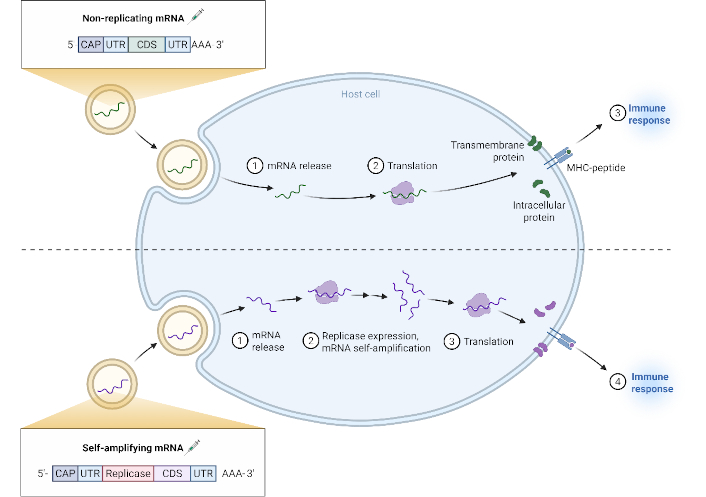

Vaccines against infections such as diphtheria, whooping cough, TB, meningitis, tetanus, and other microbial infections are already in clinical use; however, their effectiveness does not cover all age groups and disease stages (Table 1). The promising nature of mRNA vaccines in cancer treatment has prompted research into the design of mRNA vaccines against bacterial and viral infections (Figure 2). Nonetheless, the biology of microbes and their interactions with host immunity require further investigation [58]. Unlike live-attenuated or inactivated vaccines, mRNA vaccines offer the flexibility of selecting antigen types that can achieve a well-balanced interaction between humoral and cellular immunity [58]. In addition to classic adjuvants, genetic adjuvants have shown effectiveness in disease prevention and treatment [59], alongside multi-epitope vaccines that encode only individual epitopes of target antigens, thereby minimizing potential adverse effects [60].

Summary of mRNA vaccines for the prevention and therapy of bacterial and viral infections

| mRNA vaccine | Infection type | References |

|---|---|---|

| M72/AS01 | Tuberculosis | [61] |

| BNT162b2 (Comirnaty) | COVID-19 | [62] |

| mRNA-1215 | Nipah virus | [63] |

| ID91* | Tuberculosis | [64] |

| 19ISP | Lyme disease | [65] |

| mRNA-1273 (Spikevax) | COVID-19 | [66–68] |

| VAL-506440 | Influenza | [69] |

* Tested in animal models

Mechanism of non-replicating versus self-amplifying mRNA vaccines. Created in BioRender. Ahmed, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/89asvgv

In the development of bacterial vaccines, the WHO has listed virulent multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens as top-priority threats, collectively known as ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species). MTB remains a major public health concern that requires novel therapeutic approaches [58]. Before 2023, research on mRNA vaccines for MTB was conducted without the use of delivery systems, administering the vaccine in an unmodified form [58]. However, vaccination with ID91 saRNA encapsulated in a nanostructured lipid carrier elicited both cellular and humoral immune responses [64]. The vaccine also provided prophylactic protection by reducing the bacterial load in the lungs of immunized mice infected with a low dose of MTB H37Rv. Moreover, using an mRNA vaccine in a prime-protein boost format significantly reduced bacterial load in the lungs [64].

Another study by Wang et al. [70] investigated mRNA vaccine variants against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: (i) PcrV antigen, a component of the type III secretion system (TSS3), and (ii) a fusion protein OprF-I, composed of outer membrane proteins OprF and OprI. Their findings showed that the PcrV antigen vaccine stimulated adaptive immune responses more effectively than OprF-I. Furthermore, immunization with both mRNA vaccine types generated a more pronounced immune response, exhibited fewer side effects, and increased survival rates [70]. The efficacy of PcrV as an antigen in mRNA vaccines has been further validated in subsequent studies [71]. Other studies have focused on mRNA vaccines against bacterial infections of public health significance. One study formulated mRNA into cationic LNPs combined with the glycolipid α-GC as an adjuvant. This mRNA delivery system, tested in animal models, improved both innate and adaptive immune responses against Listeria monocytogenes [72].

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated mRNA vaccine development, demonstrating their potential for infectious disease control. A study on mRNA-1273 revealed a robust type 1 helper T cell (Th1)-biased CD4 T cell response but weak Th2 and CD8 T cell responses. The efficient neutralizing antibodies produced indicate strong protection against SARS-CoV-2 [67, 73]. mRNA vaccines are typically administered intramuscularly, intradermally, or subcutaneously, facilitating antigen presentation to immune cells. This process induces CD8+ T cell responses, polyfunctional Th1 cells, and antibodies that inhibit viral replication [74]. Similarly, an mRNA vaccine against chikungunya virus (CHIKV) encoded a potent neutralizing human monoclonal antibody, proving effective for CHIKV treatment [75].

In the treatment of EBV infection, a vaccine amalgamating the glycoprotein 350 and a multi-epitope vaccine antigen (EBVpoly) with an amphiphilic (AMP)-modified CpG DNA adjuvant (AMP-CpG) augmentation was developed to promote a continuing antibody and cell-mediated immunity, assessed in different human leukocyte antigen-typed multiple sclerosis mouse models [76]. This approach was vital in eliciting lasting EBV-specific neutralizing antibodies and multifunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in the models [77]. In addition, an mRNA-1189 vaccine that encodes four EBV proteins: gp350, gH/gL, gB, and gp42, is currently undergoing phase I clinical trials at Moderna in an attempt to avert EBV infection. At the West China Hospital of Sichuan University, a similar study is being performed by improving an mRNA vaccine that encodes EBV-LMP2 integrated with the MHC-I molecule’s intracellular sequence to optimize immune presentation and processing (NCT05714748) [78]. Furthermore, a novel multimeric EBV gp350-ferritin nanoparticle vaccine with a saponin-based Matrix-M adjuvant (NCT04645147) has been evaluated by the National Institute of Health, demonstrating an attempt to utilize mRNA vaccine technology to combat infections and illnesses linked to EBV [79].

Immunoinformatic has also revolutionized mRNA vaccine design [80]. Advances in artificial intelligence and bioinformatics have facilitated the development of machine learning tools and neural network platforms for antigen prediction and analysis [81, 82]. These in silico approaches enable the selection of epitopes that elicit optimal cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL), helper T lymphocyte (HTL), and B-cell responses [80, 83]. However, designing mRNA vaccines for viral infections remains more challenging than for bacterial infections because of the complexity of selecting appropriate target antigens.

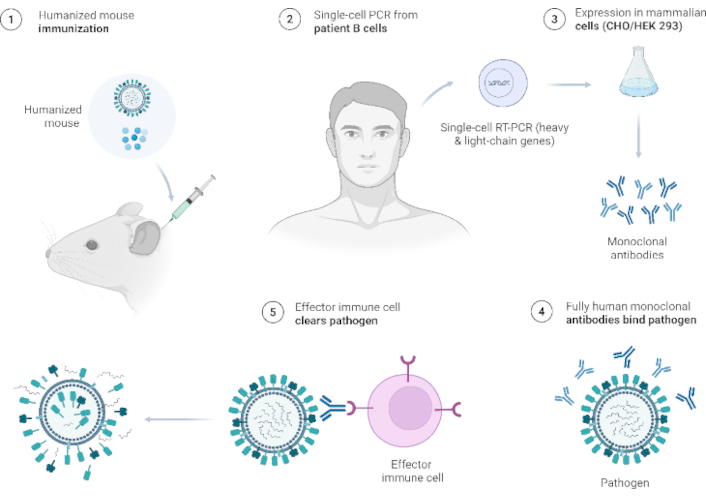

Antibodies are naturally present in human blood and cells. Another type of immunity is invasive immunity, which is imposed using synthetically manufactured antibodies that mimic the body system, known as monoclonal antibodies (Figure 3). Some monoclonal antibodies are used as immunotherapeutic agents that function synchronously with cells to attack foreign bodies and treat diseases (Table 2). They can equally target and block signals that cause abnormal multiplication or division of cells, as observed in cancer [84]. Several monoclonal antibodies effective against viral or bacterial infections have been developed, although only a few have been approved for clinical practice [85], while others are progressing through clinical trials with great prospects, particularly those with altered structures to provide optimal advantages [86]. This approach can help overcome the limitations of serum-derived immunoglobulin G (IgG) preparations [85]. Monoclonal antibodies are more effective than polyclonal antibodies because of their consistent characteristics and immunity profile, which relates to the ease of production in large quantities in most immunotherapeutic remedies [87]. This result was attributed to their affinity for specific antigens. Based on the structure (composition), monoclonal antibodies are classified as murine (fully mouse-derived), chimeric (mouse variable regions fused to human constant regions), humanized [only the mouse monoclonal antibody complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) are grafted onto a human framework], and human (entirely human-derived antibody) [88]. Although antibodies have been used to treat a wide variety of diseases, only a few can be used to treat viral and bacterial infections [89]. The repeated use of mouse monoclonal antibodies as therapeutics in humans leads to the generation of anti-mouse antibodies, thereby reducing the therapeutic window of these immunotherapeutic agents. To address this issue, a chimeric antibody was developed to suppress the immunogenicity of monoclonal antibodies in humans [90].

Workflow for fully human monoclonal antibodies. Created in BioRender. Ahmed, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f6460ol

Summary of monoclonal antibodies for the prevention and treatment of bacterial and viral infections

| mAbs | Infection type | References |

|---|---|---|

| Palivizumab | Respiratory syncytial virus | [91] |

| Anti-PhtD | Streptococcus pneumoniae | [92] |

| MEDI3902 (Gremubamab) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [93] |

| AR-301 (Salvecin) | Bacterial infection | [94] |

| 514G3 | Staphylococcus aureus | [95] |

| Nirsevimab | Respiratory syncytial virus | [96] |

| Clesrovimab | Respiratory syncytial virus | [97] |

| Bebtelovimab | COVID-19 Omicron variant | [98] |

| Raxibacumab | Anthrax | [99] |

| Bezlotoxumab | Clostridium difficile | [100] |

| Oblitoxaximab | Anthrax | [101] |

| Twinrab™ | Rabies | [102] |

| Rabishield | Rabies | [103] |

| Ibalizumab | HIV | [104, 105] |

mAbs: monoclonal antibodies

The curbing of SARS-CoV-2 entry was remedied through an immunotherapeutic mechanism to identify the interaction between angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and viral spike glycoprotein, which could be blocked by antibodies targeting the spike viral domain, thereby inhibiting viral infection [89]. Monoclonal antibody-based immunotherapy effectively targets tumor cells and promotes long-lasting antitumor immune responses, thereby improving cancer treatment strategies [106]. These protective effects can be employed against bacterial and viral pathogens, as observed in tumor cells. A previous study demonstrated that evaluating antibody-coated bacteria (ACB) in endotracheal aspirate samples significantly improves the specificity of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) diagnosis by ensuring a clear distinction between viral colonization and non-infectious conditions, thereby reducing overtreatment and resulting in antibody resistance [107].

Monoclonal antibodies offer several advantages over traditional serum-derived immunoglobulin treatments, including greater specificity and potency by targeting specific epitopes, reduced risk of pathogen transmission, more consistent antibody content between batches, and the ability to engineer an extended half-life. Human antibodies with unprecedented activities could become the principal tools for managing future viral and bacterial epidemics, with potential applications in preventing and treating severe human infections [108].

Adoptive cell therapy involves boosting the number of immune cells or modifying their function to treat disease conditions. This is achieved by expanding autologous or allogeneic immune cell numbers and infusing genetically engineered immune cells to enhance their function [109]. Adoptive cell therapy, particularly chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, has gained popularity in the treatment of hematological malignancies. To date, six CAR T cell therapies have been approved by the US FDA [39]. The relative success of adoptive cell therapy in hematological malignancies has prompted the feasibility of adopting this strategy for chronic infectious diseases, infections due to a dysfunctional or suppressed immune system, and MDR infections [110]. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is used as a treatment option for various disorders, but it comes at the cost of an immune-deficient phase in which the patient is susceptible to opportunistic viral infections, such as cytomegalovirus, EBV, and adenovirus infections [111]. Transfusion of virus-specific T cells (VSTs) is effective in treating these infections, as evidenced by approximately 20 completed phase I/II clinical trials and over 30 ongoing clinical trials [111, 112]. VSTs are currently in clinical use against post-transplantation viral infections on a compassionate use basis; posoleucel was expected to receive FDA approval; however, it failed to satisfy the primary endpoints of a phase III clinical trial [113]. Tabelecleucel for patients with EBV-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease is another VST in phase III clinical trials (NCT03394365), and its enthusiasts hope to obtain FDA approval [114]. Genetic engineering of VSTs with CAR to increase their lifespan and efficacy is already underway in studies targeting the HIV, HBV, HCV, and coronaviruses [115]. CAR T cell strategies have gained more prominence in HIV studies than in studies of other viruses, considering the formidable challenge of developing a cure for HIV [116]. Preclinical and clinical trials (NCT04648046 and NCT03240328) targeting viral proteins, mainly gp-120, employing CD4 and/or CD8 CAR T cells showed significant suppression of HIV replication and destruction of HIV-infected cells; however, total elimination of HIV-infected cells has not yet been achieved with this approach because of low surface HIV antigen expression on the infected cell membrane and poor CAR T cell infiltration [117, 118]. Intermittent co-administration with vaccine peptides or APCs has been shown to sustain CAR T cell expansion and boost immune responses, considering their poor persistence in tissues [119]. Schreiber et al. [120] reported the efficacy of CAR T cells transduced with HBV-specific antibody fragments in murine studies, demonstrating the potential of CAR T cell therapy for treating infectious diseases. Kalinina et al. [121] transduced naïve T cells with a TCR targeting S. typhimurium antigen; the T cells demonstrated a higher capacity for bacterial elimination after transfer into infected mice when compared to normal T cells. Similar outcomes were observed when monocyte-derived macrophages were used to treat MDR bacterial infections in murine models [122] and when macrophages were loaded with photosensitizers to treat MDR Staphylococcus aureus and Acinetobacter baumannii in mice [123]. CAR T cell therapy for MTB infections is currently being evaluated, considering the increased number of cases of drug resistance and chronic proclivities [110]. Adoptive T cell therapy has been widely explored, and scientists have begun to pay more attention to the adoptive transfer of other immune cell types as a treatment option in the past few years. Chung et al. [124] showed an increase in the antibody population and a decrease in viral load when virus-specific B cells targeting lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus were infused into mice. The variety of microbial antigens and their potential for mutation, which dampens CAR efficacy, the cost of CAR T cell production, and safety concerns, are some drawbacks of this strategy that are being addressed with better sequencing tools and gene editing technologies [119]. The increase in superbugs, chronic infections, and therapy-induced immunosuppression makes adoptive cell therapy a viable alternative to other less effective therapeutic strategies [39].

Immune system cells are conventionally cells of innate or adaptive immunity [125], although some cells are better prepared to switch between the two functions of innate and adaptive immunity, and one of the best-equipped cells is the iNKT [126]. iNKTs, also known as cytotoxic innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), are a subset of cells endowed with molecular memory of surface markers [127]. An invariant αβ TCR associated with the class I major histocompatibility complex, class I-related protein CD1d, reacts with glycolipid antigens on the surface of APCs [128]. They are activated in many infectious diseases and inflammatory conditions and rapidly produce large amounts of cytokines that influence other immune cells [129].

iNKTs recognize lipid-derived determinants on the cell surface, supporting their weaponization for antitumor, viral, and bacterial therapies [130]. They are also explicitly equipped with compact exosomes that package and express eomesodermin (Eomes) [131]. These Eomes-containing exosomes exhibit antitumor properties comparable to those of NK cells and respond to various intracellular pathogens such as bacteria and viruses [132, 133]. Exosomes found in iNKTs are also rich in cytotoxic proteins, such as perforin and granzymes, as well as death receptor ligands, such as FasL and TRAIL [134], which enable exosomes to induce apoptosis in cancer cells and cells infected by viral or bacterial pathogens, such as MTB [135] and SARS-CoV-2 [136], effectively mimicking the cytotoxic and cell-dissolving effects of NK cells, but without requiring direct cell-to-cell contact [137]. Advantageously, the use of NK cell-derived exosomes in immunotherapy helps generate a broader network of immune responses that can penetrate tissues and dissipate deep tumor cells or tissue-invading pathogens with systemic effects [138, 139]. Therefore, more giant cells cannot reach this area without the risk of an autoimmune reaction [140]. This property is a revolutionary point for the use of iNKT cells in immunotherapy and allows pre-administration, re-administration, and re-dosing of cellular components in clinical trials until therapeutic interventions are achieved [141].

Previously, the effector cells that mediated antitumor, viral, and bacterial therapy immunity were αβ T cells and iNKTs [142]. Recently, it has been shown that γδ T cells are the complementary element by which tumor cells are rejected and adapted to defend against the invasion of highly pathogenic organisms into cells and tissue systems [143]. The limitations of iNKTs are due to their inability to enhance the ability of γδ T cells in antigen presentation, regulatory functions, and induction of antitumor responses to excessively malignant tumors, as well as in the treatment of inflammatory conditions caused mainly by pathogen invasion [144]. The weaponization of iNKTs by molecular mechanisms allows them to express the functions of γδ T cells by switching intracellularly and producing compact cytokines that enable them to express the functions of both iNKTs and γδ T cells, demonstrating their potential use in immunotherapy, molecular immunology, and vaccinology [145].

MAITs represent a significant subset of unconventional T lymphocytes, forming the largest cadre of innate-like T cells in humans [146]. They are uniquely positioned at the nexus of innate and adaptive immunity, largely due to their semi-invariant TCR, primarily Vα7.2-Jα33 in humans, which enables them to recognize vitamin B metabolites, such as 5-OP-RU, produced via the riboflavin (vitamin B2) biosynthetic pathway in bacteria, viruses, and fungi [147, 148]. Unlike conventional T cells, which rely on the presentation of peptide antigens by highly polymorphic MHC molecules, MAITs interact with antigens via the evolutionarily conserved MHC class I-related protein, MR1, found on diverse APC [146]. While early investigations suggested that the conserved nature of both MR1 and semi-invariant TCR might limit the scope of antigen recognition, emerging research has revealed a surprising degree of TCR diversity within the MAIT population [148]. This broader repertoire enables the detection of a wider array of microbial metabolites and the mounting of clonotype-dependent responses against various pathogens [146]. Upon activation, MAITs rapidly unleash robust effector functions, marked by the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-17, and the deployment of potent cytotoxic mediators, such as granzyme B and granulysin [149, 150]. Their abundant distribution across mucosal tissues, including the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory tract, underscores their essential role as vigilant sentinels, orchestrating localized immune responses against drug-resistant bacteria, fungi, and emerging viral threats [151].

As immunotherapeutic strategies continue to evolve in response to AMR and complex infectious challenges, the potential of MAITs as therapeutic targets is increasingly recognized [152]. Their rapid responsiveness to microbial antigens, coupled with their extraordinary capacity to mobilize both innate and adaptive immune mechanisms, renders them particularly attractive for novel treatment strategies [146]. A pivotal advance in MAIT research was the development of MR1 tetramers, which allow for the precise identification and characterization of these cells across diverse tissues and disease states [153]. Promising approaches, such as ex vivo expansion, antibody opsonization, IL-7 treatment, and the use of artificial APCs (aAPCs), have demonstrated the feasibility of enhancing MAIT responses, while synthetic MR1 ligands and engineered MAIT populations offer innovative avenues to enhance antimicrobial efficacy [154–157]. These strategies are particularly compelling given the cells’ ability to recognize conserved microbial metabolic signatures, an attribute that may circumvent the limitations of conventional antibiotic therapies against resistant strains, such as MTB and antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli [152].

In parallel, the emerging field of immuno-antibiotics, which integrates direct antimicrobial actions with the targeted modulation of MAIT responses, represents a promising avenue for overcoming the limitations of traditional antibiotics, particularly against drug-resistant bacteria [152]. However, translating these findings into clinical practice requires overcoming challenges, such as MAIT exhaustion observed in chronic infections, managing potential off-target effects, and unraveling the complex interplay between MAITs and other immune components [146, 158]. Future research is poised to optimize combination therapies by integrating MAIT modulation with monoclonal antibodies, cytokine-based interventions, and even CAR T cell approaches to enhance overall immune responsiveness [159]. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of MAIT biology, their interactions within the tissue microenvironment, and the sophisticated strategies some microbes employ to evade immune detection will be pivotal in realizing their full therapeutic potential, offering a transformative strategy against the escalating threat of infectious diseases and AMR.

Immunotherapeutic strategies offer promising alternatives to address the growing threat of AMR and other infectious diseases in humans. Advances in cytokine-based therapies, adoptive cell therapy, monoclonal antibodies, and ICIs have shown significant potential for modulating immune responses and improving patient outcomes. However, challenges such as toxicity, delivery mechanisms, and immune resistance remain. Leveraging novel technologies, such as nanoparticle-based delivery systems and genetic modifications, can enhance the therapeutic efficacy of these approaches. Future research should focus on optimizing combination therapies and exploring novel immunomodulatory targets to develop more effective and durable treatments for AMR and emerging infectious diseases.

AMR: antimicrobial resistance

APCs: antigen-presenting cells

CAR: chimeric antigen receptor

CHIKV: chikungunya virus

CSFs: colony-stimulating factors

CTLA-4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

EBV: Epstein-Barr virus

Eomes: eomesodermin

GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

HBV: hepatitis B virus

ICIs: immune checkpoint inhibitors

IFNs: interferons

ILs: interleukins

iNKTs: invariant killer T cells

LNP: lipid nanoparticle

MAITs: mucosal-associated invariant T cells

MDR: multidrug-resistant

MTB: Mycobacterium tuberculosis

ORR: overall response rate

PD-L1: programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

PRRs: pattern recognition receptors

TB: tuberculosis

TLR7: Toll-like receptor 7

TNFs: tumor necrosis factors

VSTs: virus-specific T cells

AIA and OAA: Conceptualization, Visualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Validation. AMI, CMIA, and PKF: Investigation, Validation, Writing—original draft. II, BIO, and EOD: Investigation, Writing—original draft. PYN: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—original draft, Investigation. OJO: Writing—review & editing, Validation, Supervision. MMA: Writing—review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Visualization. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.