Affiliation:

Clinical and Basic Immunology Research Department Biochemical Sciences Faculty, Universidad Autónoma “Benito Juárez” de Oaxaca, Oaxaca City 68120, Mexico

Email: qbhonorio@hotmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2853-4891

Affiliation:

Clinical and Basic Immunology Research Department Biochemical Sciences Faculty, Universidad Autónoma “Benito Juárez” de Oaxaca, Oaxaca City 68120, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4785-9088

Affiliation:

Clinical and Basic Immunology Research Department Biochemical Sciences Faculty, Universidad Autónoma “Benito Juárez” de Oaxaca, Oaxaca City 68120, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2920-7422

Affiliation:

Clinical and Basic Immunology Research Department Biochemical Sciences Faculty, Universidad Autónoma “Benito Juárez” de Oaxaca, Oaxaca City 68120, Mexico

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5851-3130

Explor Immunol. 2025;5:1003201 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/ei.2025.1003201

Received: December 04, 2024 Accepted: June 05, 2025 Published: June 30, 2025

Academic Editor: Jinming Han, Capital Medical University, China

The article belongs to the special issue Immunology of Transplantation

The mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) is a pivotal in vitro assay for evaluating T-cell responses stimulated by allogeneic antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most efficient stimulatory cells. However, the scarcity of circulating DCs in peripheral blood limits their isolation for research or clinical use. In contrast, monocytes, which are abundant and easily accessible, can be differentiated into monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs) in vitro and have emerged as the most practical and efficient stimulatory cells for MLR due to their accessibility and robust allostimulatory capabilities. This review aims to describe the scientific rationale and evidence for using moDCs in MLR assays to assess T-cell alloreactivity. Its methodology outlines the protocols for experimental, preclinical, and biosafety assays that have demonstrated the practicality of moDCs in evaluating and quantifying the alloresponse of naïve and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as the effects of immunomodulatory factors, immune monitoring, and tolerogenic strategies in the context of transplantation. Additionally, it illustrates how moDC-mediated MLRs have provided critical insights into understanding alloimmunity processes and antigen-specific T-cell responses in cancer immunotherapy, autoimmune diseases, and vaccine development, with potential implications for personalized medicine and immunotherapy optimization. In conclusion, despite ongoing challenges such as standardization and scalability in massive cell production, the current understanding and reproducible results of moDC applications in MLRs highlight their potential to develop innovative strategies focused on immune monitoring.

Under steady-state conditions, dendritic cells (DCs) take up commensal microbes and apoptotic cells to maintain immunologic tolerance. Conversely, when DCs are exposed to an inflammatory environment, this exposure triggers DC activation, transforming them into specialized cells that process, present, and activate pathogen-derived antigen-specific T cells [1]. This process strengthens the immune response and facilitates the induction of antibody-producing plasma cells [2].

Surface molecule expression and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have characterized various DC subsets in human blood and other tissues [3]. Nevertheless, blood-circulating DCs are sparse, exhibiting a semi-mature state or migrating toward their final location and differentiation [4]. Therefore, isolating them from peripheral blood may yield insufficient numbers, rendering them ineffective as stimulatory antigen-presenting cells (APCs) for in vitro assays. Fortunately, the bloodstream contains monocytes that can differentiate into DCs [3]. In vivo, monocytes serve as a continuous reserve of precursors for tissue-resident macrophages and monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs) [5]. Since the method for obtaining in vitro-produced moDC was described in 1994 by Sallusto and Lanzavecchia [6], numerous variations of this method have emerged, demonstrating successful moDC production for both research and clinical applications.

As efficient APCs, in vitro-produced moDCs have been evaluated in preclinical strategies where the immune system requires antigen-specific stimulation [e.g., tumor-specific antigens (TSA) in cancer] [7] or inactivation (e.g., alloantigens before transplantation) [8]. Given their accessibility and efficiency as stimulatory cells, moDCs have been utilized in mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) assays, which represent an effective in vitro strategy for quantifying T cell allo- and antigen-specific responses, as well as the effects of immunomodulatory agents [9–15].

The success and efficiency of an MLR in evaluating the potential T cell response against specific alloantigens depend on selecting the appropriate APCs. Blood is the most readily available source of human mononuclear cells, including monocytes and B cells [16]. However, while these cells can effectively present alloantigens, their numbers vary among individuals and may not represent the most suitable APCs involved in graft rejection [17, 18]. DCs are specialized APCs known to be the most efficient cells at inducing T cell alloresponse; however, their numbers in peripheral blood are limited [4]. This section analyzes the characteristics of moDCs that render them the most suitable and efficient APC for MLR.

The immune system’s functional complexity depends on maintaining homeostasis with the commensal microbiota, regulating opportunistic microbes, preventing pathogenic microorganisms, and aiding in tissue regeneration in the event of injury [19]. To this end, in a steady state, tissue-resident immature DCs exhibit high phagocytic capacity, facilitating the uptake of commensal microbes and apoptotic self-cells resulting from normal tissue repair. Under these conditions, DCs show low expression of costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86, and CD40), inflammatory and migratory chemokine receptors such as CC chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7), major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, while also displaying constitutive expression of immune control molecules (PD-L1, ILT2, and TIM3) [20–22]. Therefore, the homeostatic migration of these DCs toward secondary lymphoid tissues to present innocuous microbe-derived or self-antigens to T cells induces an unresponsive state (anergy) or generates regulatory T cells (Tregs), maintaining immune tolerance and avoiding potentially harmful chronic inflammation [23].

On the other hand, an inflammatory milieu caused by tissue damage provokes the maturation of DCs due to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) present in microorganisms and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) derived from injured cells [20]. This alarming environment activates metabolic, cellular, and genetic transcription signaling pathways that, beyond a microbicidal function, enable DCs to specialize in processing pathogen-derived proteins into antigenic peptides and loading them onto MHC molecules [24]. In addition, due to an overexpression of CCR7 induced by inflammation, DCs accelerate their migration toward secondary lymphoid tissues [21], where changes in cytokines and costimulatory profiles result in antigen presentation and the recognition by specific T cells that produce effector lymphocytes, thereby strengthening the immune response [25] and working together to stimulate antibody-producing plasma cells [26].

The expression of cytokines, along with the profiles of costimulatory and inhibitory molecules, varies among resident and migrating DCs across different tissues [27]. Similarly, each DC subset responds differently to pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory stimuli, reflecting its unique functionality and heterogeneity [28]. Due to the limited availability of human tissues, researchers have mainly characterized the DC subpopulations using mouse models [29]. In humans, peripheral blood DCs and certain tissue-resident DCs from experimentally accessible organs, such as the skin, tonsils, and spleen, are well characterized. However, our understanding of most human DC subsets has evolved from phenotypic, molecular, and functional correlations with mouse DCs [30].

Various human DC classifications have been established based on the expression of surface molecules. Additionally, scRNA-seq technology, which assesses the transcriptomic and functional profiles, has enabled the description of six DC groups in human peripheral blood: DC1 to DC6. Each subset is endowed with specific transcription factors and markers [3]. However, the traditional classification defines two main groups in human peripheral blood: conventional DCs (cDCs), which include cDC1 and cDC2, and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs). All of these can migrate to different tissues. Interestingly, in peripheral blood, there are also monocytes capable of differentiating into DCs [21].

In peripheral blood, monocytes are a heterogeneous group of immune cells derived from the myeloid lineage in the bone marrow, transiently circulating in the bloodstream, and representing about 2–10% of the total white blood cell count. These partially differentiated cells have short half-lives in blood circulation, approximately one day. Currently, three subsets of blood monocytes have been identified in humans based on the differential expression of CD14 (Toll-like receptor 4 coreceptor) and CD16 (Fcγ receptor III). CD14++/CD16– classical monocytes exhibit high phagocytic abilities, making up 80–90% of total monocytes. In contrast, CD14++/CD16+ or intermediate monocytes and CD14+/CD16++ or non-classical monocytes together account for around 10% of total monocytes. Due to their location in the marginating pool within blood vessels and their primary role in tissue remodeling, they are referred to as “patrolling” monocytes [31].

Given their high numbers and functional properties, classical monocytes serve as a rapid and continuous reserve of precursors for tissue-resident macrophage populations during homeostasis and inflammation, and potentially, for moDCs [32]. However, exploring moDC in human tissues has posed a significant challenge due to ethical and logistical difficulties. It has become clear that, in vivo, most DCs originate from a specific blood-circulating precursor called pre-DC, which is distinct from monocytes [33]. For instance, the study of patients with mutations in the IRF8 and GATA2 genes revealed a deficiency in blood monocyte numbers and functions, a lack of certain dermal DC subtypes, and a reduced number of macrophages, while the numbers of Langerhans cells (epidermal DCs) remained intact [34]. This evidence indicates that, under homeostatic conditions, certain dermal DCs are derived directly from circulating monocytes (steady-state moDCs). On the other hand, under inflammatory conditions, cells recruited to the skin due to monocyte extravasation maintain phenotypic characteristics of DCs and lack the macrophage markers CD16 and CD163. They have received various designations such as moDCs, inflammatory DCs, monocyte-like inflammatory cells (Infl mo-like), inflammatory macrophages (Inf mac), or monocyte-derived macrophages (Monomac) [35]. Additionally, strong evidence from animal models, human transplantation, marker analysis, and disease contexts shows that monocytes differentiate into DCs and macrophages in vivo, particularly during inflammation. While some tissue-resident macrophages originate from embryonic sources, monocytes serve as crucial responders in dynamic or pathological conditions [3, 15, 36].

In addition to describing the significant role of DCs in modulating the immune system, experimental strategies have emerged to harness their potential for clinical applications [7]. However, being aware of the limited numbers (0.1% to 1.0% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells) [37], the challenges of isolating blood-circulating DCs [38], and the impossibility of separating them from other human tissues [39], in vitro differentiated DCs derived from blood monocytes have served as the primary source of human DCs for research and cellular therapy [8, 40].

Sallusto and Lanzavecchia first described the methodology for differentiating monocytes into cells with the morphological, phenotypic, and functional features of DCs in 1994 by culturing monocytes in the presence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin (IL)-4 [6]. Since then, numerous alternatives to DC precursors, purification methods, culture mediums, differentiation factors, cytokine concentrations, maturation stimuli, and phenotypic characterization have been successfully developed [41, 42].

The primary challenge in generating moDCs for biomedical research or applying them to cellular therapy is establishing and validating viable production procedures that meet good manufacturing practice requirements to produce functional APCs capable of priming quantifiable T-cell-mediated responses [9]. The consensus reveals that obtaining antigen-loaded mature moDC may take a time-consuming protocol of 7–9 days (at least five days to differentiate immature moDC with high phagocytic abilities, one day to allow uptake of the antigen and processing, and followed by two additional days to obtain mature moDC). Although some proposals suggest reducing the entire production time to 48–36 hours with encouraging experimental evidence, they still leave the expectation of obtaining reproducible results and clinical applications [43].

The immunotherapy concept encompasses clinical strategies focused on modulating the immune system. Under this premise, DCs are the most efficient immune cells when antigen-specific activation (e.g., against TSAs in cancer or pathogen-specific antigens in infection) or inactivation (e.g., against autoantigens in autoimmune disease (AD) or alloantigens before transplantation) is desired to induce either immune overactivation or immunosuppression, respectively [44].

As described above, the in vitro production of moDCs allows for the harnessing of their functional plasticity by using pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory factors during their differentiation and maturation to obtain immunogenic (Imm-moDCs) or tolerogenic (Tol-moDCs) moDCs [7]. In this regard, Imm-moDCs have been used in interventional clinical trials for conditions such as melanoma, bladder cancer, primary advanced carcinoma of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, and HIV infection, among others (https://clinicaltrials.gov/). On the other hand, Tol-moDCs have been evaluated to assess the effects of intervention in multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, musculoskeletal diseases, type 1 diabetes, and joint disease (https://clinicaltrials.gov/), as well as kidney transplant rejection [40]. Nevertheless, despite the vast amount of information, the first and only U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved moDC-based cellular therapy is a vaccine, sipuleucel-T, or Provenge, which has been in use since 2010 [45].

Monocytes are continuously produced in the bone marrow, where they differentiate into DCs or macrophages in various tissues. As a result, they constantly migrate toward injured tissues, drawn by inflammatory chemokines (CCL2, CCL7, CCL5, CCL20, CX3CL1) across the endothelium. Their migration is influenced by maturation stimuli, including TNF-α, IL-1, microbial products, and CD40L on activated T cells, platelets, and mast cells. Additionally, they can take up both self- and pathogen-derived antigens [5, 36]. However, while monocytes have high phagocytic abilities to capture dead cells, they primarily degrade ingested proteins instead of correctly processing them to produce appropriate peptides for antigen presentation. Nevertheless, their differentiation into moDCs enhances processing capacities for presenting proteins derived from dead cells [46].

Therefore, although performed under sterile conditions, transplantation itself—due to the inflammatory environment produced by tissue damage—causes the maturation and migration of both the donor (embedded in the allograft) and the recipient (in adjacent tissues) DCs, including moDCs attracted by the chemokines and induced by the differentiation factors produced in the inflammatory milieu [47]. Hence, T cells from the graft recipient may recognize allogeneic MHC molecules via two pathways mediated by DCs. A) Through a so-called “direct pathway” involving the recognition of unprocessed MHC molecules in the graft. Donor DCs are instigated to migrate toward the recipient’s secondary lymphoid tissues. Because positive T cell selection restricts them to recognizing only self-MHC molecules, there is a high frequency of alloantigen-specific recipient naïve and memory T cells that recognize allogeneic MHC molecules expressed on donor DCs [48]. B) The “indirect pathway,” although described as less significant for graft rejection, involves the entry of recipient DCs into the grafted organ. After taking up and processing donor MHC and other alloantigens from dead cells, these DCs migrate toward recipient secondary lymphoid tissues to activate alloantigen-specific recipient cytotoxic T cells, which attack the graft, along with helper T cells that collaborate to induce alloantibody-producing plasma cells [49, 50]. moDCs are also implicated in chronic rejection, resulting in fibrosis and the development of chronic allograft injury in liver transplantation through their interactions with T cells and other immune cells [51].

Conventional immunosuppressive therapies focus on affecting the functionality of T and B cells [52]. However, counteracting the immune responses that lead to graft rejection becomes a significant challenge once these cells have been activated [53]. Therefore, it is anticipated that DC depletion in the graft and DC inactivation in the host may impede alloantigen presentation [18], and therapeutic strategies to modify DC functions to harness their tolerogenic properties would enhance the efficiency of organ transplantation [40, 54]. However, considering their inter-tissue location, depleting DCs in the grafted organ is not feasible, and depleting DCs in the host could lead to immunodeficiency [55]. Although specific strategies to modulate DC activation have been developed, their ineffectiveness in exclusively affecting in vivo DCs limits their clinical application [56, 57]. Therefore, using DCs to prevent graft rejection is regarded as cell therapy through the production of autologous Tol-moDCs [58].

Tol-moDCs can be produced in vitro using protocols that require immunomodulatory agents and genetic technology, such as anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β) [59], approved immunosuppressive drugs [60], experimental inhibitory molecules (vitamin D3) [61], genetic engineering (antisense oligonucleotides targeting costimulatory molecules or promoting anti-inflammatory factors) [62–64], or a combination of several strategies. Yet, no consensus exists on the best procedure to produce therapeutic-grade Tol moDCs [65, 66].

The hallmark of Tol moDCs is low expression of costimulatory molecules (mainly CD40) and proinflammatory factors (IL-12p70) [67]. Tol-moDC can induce T cell tolerance by promoting anergy, enhancing T regs, facilitating apoptosis, or skewing phenotypes through cell-cell contact-dependent mechanisms or soluble factors [8, 23, 40].

Currently, autologous Tol-moDCs have been used in phase I/II monocentric clinical trials to evaluate biosafety for patients with renal insufficiency receiving a kidney transplant (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT06243289 and NCT02252055), aiming to induce transplant tolerance. Further clinical trials are needed to assess doses, frequency, and administration routes, among other clinical parameters. The preclinical assays in rhesus monkeys indicate that the tolerogenic effect of Tol moDC is mediated by the induction of Treg [68].

Before a transplant, a patient must undergo several tests to maximize the safety of the procedure. These evaluations include blood group and HLA typing, as well as the search for unexpected allospecific antibodies. Currently, increasing graft compatibility primarily relies on HLA matching performed through molecular methods [69]. Nevertheless, despite those theory-matching tests, the existence of donor alloantigen-specific T cells in the receptor signifies an enormous challenge in transplantation. The above is because given the T cell restriction to recognize just self-MHC molecules—even in the absence of previous events of allogenic stimulation (transfusion, transplants, or pregnancies)—each person possesses a high frequency of alloreactive naïve and, even worse, memory helper (CD4+) and cytotoxic (CD8+) T cells with the potential to become activated and instigate graft rejection [17, 70, 71]. Since the MLR serves as an in vitro assay to analyze effective T-cell responses primed for alloantigen recognition [72–74]. Therefore, in addition to the theory matching tests mentioned, MLR may be conducted to assess the functional histocompatibility of the donor-recipient pair.

Several biosafety and preclinical trials have demonstrated the feasibility of moDCs for evaluating and quantifying the alloresponse of preexisting memory T cells prior to a transplant, along with the impact of inhibitory factors, such as suppressive drugs, on T cell responses (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03726307, NCT06243289, NCT00495755, NCT00213707).

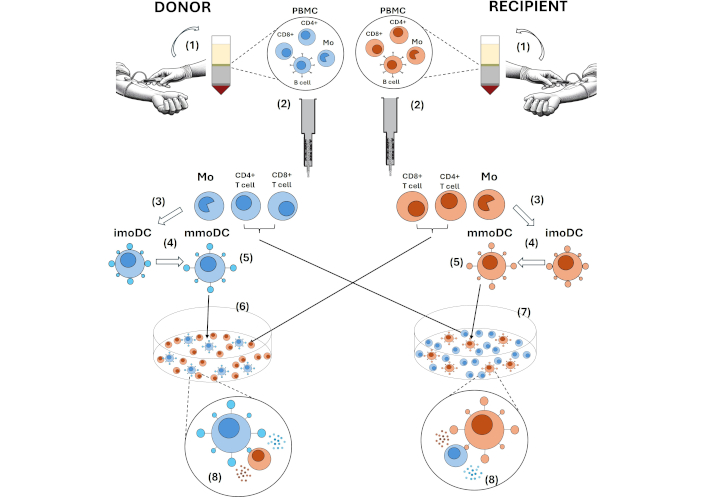

Applying the MLR to evaluate the alloresponse involves assessing the likelihood of graft rejection by coculturing recipient-derived T cells, purified from peripheral blood, as responders stimulated with donor-derived moDCs [11]. On the other hand, the procedure may involve coculturing peripheral blood-purified donor-derived T cells primed with recipient-derived moDCs to analyze the possibility of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) [75–78] (Figure 1).

Methods using moDC for evaluating T cell responses in MLR. (1) PBMC are obtained by centrifugation gradients, such as Ficoll, from peripheral blood or leukapheresis products. (2) In the MACS system, monocyte and T cell populations are purified by positive selection using anti-CD14-, anti-CD4-, or anti-CD8-conjugated magnetic microbeads. (3) Monocytes are differentiated in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 for 4 to 7 days to obtain imoDCs. (4) mmoDCs are obtained by inducing their maturation with PAMPs (e.g., LPS, Poly I: C) or inflammatory stimuli (e.g., LPS, TNF, IL-6, PGE2) for an additional 2 days. (5) The efficiency of the obtained moDC can be analyzed by flow cytometry, which includes differentiation (CD1a, CD83) and maturation (CD80, CD86, CD40) markers. (6) An MLR can evaluate the likelihood of graft rejection through coculturing recipient-derived T cells stimulated with donor-derived moDCs. (7) A second MLR may analyze the possibility of graft-versus-host disease, incorporating donor-derived T cells primed with recipient-derived moDCs. (8) In the MLRs, T cells recognize alloantigens processed and presented on allogeneic MHC molecules by allogeneic APCs. The highest quantifiable T cell proliferation is observed around days 5–8, with proliferation and activation state analyzed by flow cytometry using the CFSE-dilution method and measuring CD25 and CD69 expression, respectively. Additionally, analyzing soluble factors (cytokines and chemokines) in supernatants provides information about the alloresponse intensity. moDC: monocyte-derived dendritic cells; MLR: mixed leukocyte reaction; PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cells; GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; imoDCs: immature moDCs; mmoDCs: mature monocyte-derived dendritic cells; PAMPs: pathogen-associated molecular patterns; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; APCs: antigen-presenting cells; CFSE: carboxy fluorescein succinimidyl ester

MLR can be performed using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) purified by differential centrifugation with Ficoll from the whole blood of the donor and recipient [79]. However, under these conditions, APC function is performed by monocytes and B cells, whose numbers may vary among patients. These cells do not represent the most suitable APCs involved in graft rejection and for MLR with effective results. A high density of costimulatory and MHC class II molecules is crucial to triggering an efficient MLR. Although monocytes and B cells possess these molecules, their expression levels are low, which provides them with weak allostimulatory capabilities [16].

Depending on the specific transplanted tissue, responder cells for an MLR may be obtained from different sources, albeit with certain limitations. For example, conducting a one-way MLR with bone marrow-derived responder cells indicates that, within this tissue, most cells are not T cells, and many others demonstrate persistent basal proliferation [80]. On the other hand, purifying lymphocytes from the thymus, lymph nodes, or spleen as responder cells is appropriate for MLR in animal models [81, 82]. However, it is not feasible in human assays, and stimulator cells must be obtained from PBMC or induced in vitro [10–12, 83].

The MLR can be two-way when both T cell populations, from the donor and recipient, proliferate [84] or one-way, when only one of those lymphocyte populations can respond [85]. Although the first provides a general view of the donor-recipient’s histocompatibility, it does not allow for the evaluation of each response. Therefore, the latter is preferable because it enables the evaluation of the likelihood of graft rejection by quantifying the proliferation of only recipient-derived T cells as responders or the possibility of GvHD by analyzing donor-derived T cells. This is achieved by abolishing the proliferative ability of stimulator cells through irradiation [86] or treating them with mitomycin C [85].

Some recipients of stem cells or kidney allografts—because of their inherent condition—are often immunocompromised, and their peripheral blood T cells may be affected. Therefore, in this case, to evaluate whether these cells have the potential to proliferate, the inclusion of HLA-DR mismatched controls should be analyzed. Then, the response in the MLR between donor and recipient is compared with the reaction toward the health controls [83].

MLR application in immunosuppressive drug testing involves using moDCs in preclinical studies to evaluate the in vitro effect of immunosuppressive drugs on alloreactivity, such as calcineurin and mTOR inhibitors, as well as co-stimulatory blockade agents on both DC stimulatory abilities and T cell activation, proliferation, and cytokine profiles [51, 87–91]. On the other hand, in addition to methods such as flow cytometry for analyzing T cell activation, monitoring donor-specific antibodies, and using specific radiotracers to visualize T cell trafficking, among others [92], moDC can be used in immune monitoring in clinical settings to track specific T cell responses to alloantigens during the post-transplant phase. This procedure assesses the frequency and intensity of T-cell alloresponse, providing insights into the risk of rejection or tolerance [93].

moDCs are widely used to assess the immune responses triggered by cancer immunotherapies, such as allogeneic tumor cell-based vaccines or adoptive tumor-specific T-cell transfer. In these clinical interventions, moDCs are utilized in vivo to present TSA to T cells and subsequently in vitro through an MLR to monitor the resulting immune activation toward TSA, allo, and autoantigens [9, 10, 94–100].

The MLR can evaluate the strength of tumor-specific T-cell responses. This is accomplished by mixing T cells from the patient with moDCs previously loaded with TSA or tumor-derived lysates. The resulting cellular events—proliferation, activation, and cytokine profiling—provide information about tumor immunogenicity and the immune system’s ability to recognize and trigger a tumor-specific immune response or even the risk of autoimmunity [100].

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) involves the infusion of autologous, tumor-specific T-cells that have been expanded ex vivo or genetically engineered to target cancer cells. In this immunotherapy, MLR is used to measure whether these transferred cells recognize, proliferate, and kill tumor cells [101]. However, in allogeneic ACT, MLR may also predict the risk of unwanted immune alloresponse, such as donor T cell rejection by the recipient’s immune system or GvHD mediated by donor T cells that damage recipient cells. This could compromise the therapy’s success, which depends on the compatibility and persistence of donor T cells that must recognize and destroy host tumor cells [102].

Additionally, including moDCs loaded with different TSAs in various MLR assays allows for the identification of the most immunogenic TSA that elicits strong T-cell responses as potential candidates for developing targeted immunotherapies, such as personalized cancer vaccines or ACT [98–100]. Likewise, the likely alterations of T-cell activation mediated by the tumor microenvironment (TME) can be evaluated by adding tumor-derived factors (e.g., soluble components or immune cells from the tumor) to the MLR, providing insights into how immunotherapies could counteract these effects [98, 100]. Finally, the MLR can be developed for personalized immunotherapy approaches tailored to the specific immune reactivity of the tumor, utilizing autologous moDCs pulsed with their tumor-derived antigens [94].

ADs are characterized by the pathological activation of preexisting low-affinity T cells that recognize self-antigens. Depending on their maturation state, DCs have been involved as both instigators and protectors of AD [103]. Therefore, as the best APC, moDCs-based MLR provides a suitable tool to investigate the presence and contributions of autoreactive T cells for the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of these diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, etc.).

Self-antigen-loaded moDCs (e.g., myelin in multiple sclerosis, GAD65 in type 1 diabetes, β2GPI in antiphospholipid syndrome, or joint proteins in rheumatoid arthritis) are utilized in MLR to quantify the presence of autoreactive T cells and analyze their activation state and cytokine profile (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17) in autoimmune patients, as well as assess the functionality of Tregs in maintaining immune tolerance [59, 103–105].

moDCs-based MLR enables the distinction of each specific T cell polarization contribution (e.g., Th1, Th17, or Treg cells) to autoimmune pathology. MLR can also be employed to examine the Th1/Th17 dominance. In many ADs, IL-17 (Th17 cells) or IFN-γ (Th1 cells) are critical cytokines driving chronic inflammation and tissue damage [106].

MLR can also be applied to analyze the role of individual pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, environmental factors (e.g., toxins), pathogen-derived antigens, immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., corticosteroids, methotrexate), biologic agents (e.g., TNF inhibitors), drugs targeting specific immune checkpoints (such as CTLA-4 or PD-1), tolerance-inducing vaccines, or peptide-based therapies in the beginning, progression, and counteraction of the autoimmune process [107] and simultaneously investigate the signaling pathways activated in T cells, such as the NF-kB, JAK/STAT, and MAPK pathways, which are frequently dysregulated in autoimmune conditions [108]. Therefore, since the immune response can differ among AD patients, the MLR can be used to predict how a specific AD patient might respond to a particular treatment in order to create tailored therapeutic strategies for that individual [109, 110].

The MLR applications in vaccine development encompass evaluating antigen immunogenicity, biosafety, and personalized vaccine design. This allows for the simultaneous assessment of T cells and cytokine profiles to optimize vaccine formulations [94].

moDC-based MLR can be used to analyze T cell activation and proliferation, as well as polarization [CD4+ helper T cells (Th1, Th2, Th17), CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, Tregs], and cytokine secretion (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α) against specific candidate antigens for a vaccine. Given this, the immune balance will determine whether this antigen may induce an immune response with cell memory and antibody production, while avoiding excessive immune tolerance or even autoimmunity [111].

Likewise, in combination with vaccine antigens, MLR may be applied to optimize vaccine formulations, test different adjuvants, evaluate various vaccine delivery systems such as liposomes, nanoparticles, or viral vectors, assess cross-reactivity (i.e., whether T cells might respond to similar antigens), identify the most immunodominant epitopes within a vaccine antigen, and measure the recall response of memory T cells to subsequent doses [112–114].

Since the MLR involves human moDC-T cell interactions, it represents a better humanized preclinical model than animal models. This assay may provide more accurate predictions of how a vaccine would perform in humans. The MLR can be adapted to assess immune responses under different genetic backgrounds or in individuals with immunocompromised conditions (e.g., elderly subjects or patients with cancer), chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, obesity), co-infections (HIV), or even specific T cell responses in children. These variations ensure that vaccine formulations can be adjusted for different immune system profiles, enhancing safety and efficacy across all populations [114–116].

A better approach to assessing a preexisting T-cell response should consider that several DC subsets, with specific functions and tissue distribution near the inflammatory process, may contribute differentially to antigen presentation [18]. However, due to their accessibility and efficiency, only in vitro-produced moDCs have been extensively used as the best APCs (stimulatory cells) in MLR assays [9–12, 83].

The most common source for obtaining monocytes is peripheral blood or leukapheresis products—centrifugation gradients (Ficoll) separate PBMC. Monocytes are purified by magnetic cell sorting (MACS), which achieves high purity rates above 95%. Monocytes are differentiated in vitro by culturing them with GM-CSF and IL-4 for 4 to 7 days, generating immature moDCs (imoDCs). Then, maturation is induced by adding stimuli such as LPS, TNF, Poly I: C, IL-6, and PGE2, either alone or in different combinations, for 2 more days to obtain mature moDCs (mmoDCs). The status of the obtained cells is assessed by measuring the expression balance of differentiation/maturation and inhibitory markers such as CD1a, CD83, CD86, CD40, Tim-3, PD-L1, and HLA-DR using flow cytometry.

Responder cells can be represented by whole PBMC or partially purified naïve or CD3+ T cells. However, the alloresponse can be analyzed in greater detail by purifying CD4+, CD8+, and CD45RA-memory T cells using MACS.

The moDC: T cell cocultures are performed in a 1:10 ratio for 4 to 7 days. The balance between cell proliferation and death can be measured using simple methods such as cell counting and viability assessments through light microscopy and trypan blue staining in the Neubauer chamber, although these may yield indefinite and unquantifiable results [117]. Cell proliferation can be quantified by integrating radioactive tritium [3H]-labeled thymidine [118] into the MLR culture. Still, this method does not evaluate cell death or activation and requires a scintillation counter. Therefore, flow cytometry represents an advanced technology for cell analysis and data acquisition, enabling the simultaneous analysis and quantification of cell proliferation [e.g., CFSE-dilution method, 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU), Ki-67 expression, WST-8/CCK8 tetrazolium assay] related to CD4- or CD8-specific responses, cytokine expression (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-2), cell death (e.g., annexin V, propidium iodide, 7AAD), activation (e.g., CD25, CD69), and the induction of Tregs (e.g., Foxp3, CTLA-4) [13, 59, 104] and coculture supernatants can be utilized to quantify cytokines and chemokines related to the alloresponse intensity and T cell migratory abilities, such as IFN-γ, IL-12, CCL2, CCL3, CXCL9, and CXCL10 (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Methods to analyze T cell responses using moDCs as stimulatory cells in an MLR

| Responder cells | Source of moDCs | Days of stimulation | Proliferation method | Application | Reference and year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells purified by MACS | Peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes purified by MACS | 5 days | CD25 and Ki-67 expression | To evaluate phenotypic changes associated with lymphocyte responsiveness | [9]2024 |

| Peripheral blood naïve T cells purified by MACS | Peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes purified by MACS | 7 days | CFSE dilution | To evaluate the effect of Sulfavant A in an MLR | [10]2023 |

| PBMC | Monocytes from leukapheresis products | 5 days | CFSE dilution | To evaluate recipient T cell responses facing donor-derived moDC before liver transplantation | [11]2021 |

| Peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells purified by MACS | Peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes purified by MACS | 5 days | WST-8/CCK8 tetrazolium assay | To evaluate the effect of IL-35 on moDCs differentiation and stimulatory capability | [12]2018 |

| Peripheral blood CD4+CD45RA– T cells purified by MACS | Peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes purified by MACS | 5 days | CFSE dilution | To analyze tolerance induction on effector/memory T cells | [13]2010 |

| Peripheral blood CD2+ T cells purified by MACS | Peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes purified by MACS | 4 days | [3H]-thymidine | To assess theimpact of stably immature, donor-derived DC on alloimmune reactivity | [119]2007 |

| CD4+ peripheral blood T cells purified by MACS | Peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes purified by MACS | 7 days | CFSE dilution and [3H]-thymidine | To evaluate alloreactive T-cell responses before and after depletion of alloantigen-specificT cells | [14]2004 |

| CD3+ cells obtained from the peripheral blood | Peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes purified by MACS | 5 days | [3H]-methyl-thymidine | To monitor immunological and clinical response to DC vaccination | [15]2004 |

moDCs: monocyte-derived DCs; MLR: mixed leukocyte reaction; MACS: magnetic cell sorting; CFSE: carboxy fluorescein succinimidyl ester; 3H: tritium; DC: dendritic cells; PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cells

In the MLR, T cells recognize alloantigens processed and presented on allogeneic MHC molecules by allogeneic APCs. This cell interaction (immunological synapse) induces that, among the entire T cell repertoire, only alloantigen-specific naïve and memory T cells become activated and proliferate. The highest measurable cellular proliferation occurs around 5–8 days [9, 10, 12, 83].

Given their feasibility for in vitro generation and high allostimulatory capability, moDCs are the most efficient stimulatory cells in a mixed lymphocyte reaction. These properties support their application in evaluating preexisting memory T-cell alloresponse to analyze the likelihood of transplant success and the effects of immunomodulatory factors, immune monitoring, and tolerogenic strategies. Furthermore, the use of moDC in MLRs has provided critical insights into alloimmunity processes relevant to cancer immunotherapy, ADs, and vaccine development, facilitating the optimization of immunotherapeutic interventions.

AD: autoimmune disease

APCs: antigen presenting cells

CCR7: CC chemokine receptor 7

cDCs: conventional dendritic cells

DCs: dendritic cells

GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

GvHD: graft-versus-host disease

Imm-moDCs: immunogenic monocyte-derived dendritic cells

MACS: magnetic cell sorting

MHC: major histocompatibility complex

MLR: mixed leukocyte reaction

moDCs: monocyte-derived dendritic cells

PAMPs: pathogen-associated molecular patterns

PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cells

scRNA-seq: single-cell RNA sequencing

Tol-moDCs: tolerogenic monocyte-derived dendritic cells

Tregs: regulatory T cells

TSA: tumor-specific antigens

The authors thank the Laboratorio Nacional de Citometría (LabNalCit), Oaxaca for their support for the moDCs-based MLR analysis from our laboratory, which has provided results for the writing of this review. During the preparation of this work, the authors utilized GitMind AI to create the hand elements of Figure 1. After using the tool, authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and will take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

HTA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. SASL, AAA, WdJRR: Data curation, Investigation, Writing—original draft. All authors have read and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by the Clinical and Basic Immunology Research Department Biochemical Sciences Faculty, Universidad Autónoma “Benito Juárez” de Oaxaca. A.A.A. has doctoral fellowships of CONAHCyT number 799779. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 4985

Download: 82

Times Cited: 0