Affiliation:

1Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (IRAD), Yaoundé 2123, Cameroon

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3892-8950

Affiliation:

2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Sciences, University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé 812, Cameroon

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-2638-4047

Affiliation:

3Laboratory of Systematics and Plant Ecology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé 812, Cameroon

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6567-3431

Affiliation:

4International Center for Tropical Agriculture, Nairobi 823-00621, Kenya

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6859-0962

Affiliation:

1Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (IRAD), Yaoundé 2123, Cameroon

Email: josianembassi@yahoo.fr

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6893-6065

Explor Foods Foodomics. 2025;3:1010103 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37349/eff.2025.1010103

Received: June 24, 2025 Accepted: October 30, 2025 Published: December 10, 2025

Academic Editor: Andrea Gomez-Zavaglia, Center for Research and Development in Food Cryotechnology (CIDCA CONICET), Argentina

Aim: This study examined the influence of coffee parchment (CP) particle size on growth, yield, morphology, and color quality of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus citrinopileatus, aiming to optimize the valorization of agro-industrial coffee waste through mushroom cultivation.

Methods: Three CP particle size classes, raw CP (RCP), medium CP (MCP), and fine CP (FCP), were prepared and tested as substrates under controlled conditions. Growth traits (spawn running, primordial initiation, fruiting time), morphological parameters (pileus number, diameter, stipe length), yield indices [total yield, biological efficiency (BE), and production rate (PR)], and cap color (L*, a*, b*) were assessed. Data were analyzed using ANOVA and Duncan’s test at p < 0.05.

Results: Particle size significantly affected all parameters. MCP and FCP accelerated colonization and primordia initiation by up to 7–8 days compared with RCP. Mushrooms cultivated in the FCP achieved the highest yields (377.2 ± 18.5 g for P. ostreatus; 355.0 ± 17.0 g for P. citrinopileatus), BE (75.2% and 72.0%), and PR (156.7% and 150.5%). Morphological traits were also improved, with larger and more abundant fruiting bodies on MCP and FCP. Color analysis indicated darker caps and a higher red hue on MCP substrates, suggesting enhanced pigment biosynthesis. Overall, P. ostreatus outperformed P. citrinopileatus, though both species responded positively to substrate refinement.

Conclusions: CP particle size is a critical determinant of Pleurotus cultivation performance. Finer substrates improved yield, efficiency, and crop earliness, while enhancing commercial quality. These findings demonstrate the potential of physical substrate engineering to promote circular bioeconomy strategies and valorize lignocellulosic residues in coffee-producing regions.

The growing global demand for sustainable food systems and the need for efficient waste management have stimulated interest in mushroom cultivation as a biotechnological strategy aligned with the circular bioeconomy paradigm. Among the edible fungi, Pleurotus spp. are widely cultivated due to their rapid growth, adaptability to lignocellulosic substrates, low production costs, and high biological efficiency (BE) [1–3]. These fungi are increasingly valued not only as nutritious food but also as a sustainable method of valorizing agricultural residues into functional products. From a nutritional and functional standpoint, Pleurotus mushrooms are rich in high-quality protein, dietary fiber, essential minerals (e.g., calcium, iron, phosphorus), and B-complex vitamins, while remaining low in fat. They also contain a diverse range of bioactive compounds, including β-glucans, phenolics, ergothioneine, and lovastatin, which confer antioxidant, immunomodulatory, cholesterol-lowering, and anti-inflammatory properties [4–8]. These attributes have led to their classification as functional or medicinal foods with growing market demand. Biotechnologically, Pleurotus spp. play a significant role in the degradation of recalcitrant lignocellulosic materials through their secretion of oxidative and hydrolytic enzymes such as laccases, peroxidases, cellulases, and xylanases. This enzymatic machinery allows them to efficiently convert various agro-industrial residues, such as wheat straw, sawdust, sugarcane bagasse, and notably, coffee by-products, into valuable biomass [3, 5, 9].

Coffee (Coffea spp.), one of the world’s most consumed beverages and the second most traded commodity globally, generates over 10 million tons of solid waste annually [10, 11]. These by-products include pulp, husk, silverskin, spent grounds, and coffee parchment (CP), the fibrous endocarp comprising ~18% of the cherry dry weight. CP is particularly rich in cellulose (40–49%), hemicellulose (25–32%), and lignin (33–35%), yet it is underutilized and often discarded, leading to pollution and loss of valuable biomass [11, 12]. Efforts to valorize coffee waste have expanded in recent years, with applications ranging from biofuels, organic acids, bioplastics, and animal feed to functional foods and mushroom substrates [3, 5, 6, 8, 11]. Among these, mushroom cultivation is particularly attractive because it combines waste valorization with protein production. However, while coffee pulp and husk have been studied, the use of CP as a substrate, particularly regarding its physical properties such as particle size, remains insufficiently explored.

Substrate particle size is a key determinant in mushroom cultivation, influencing physical characteristics like porosity, aeration, water retention, and enzymatic accessibility, which in turn affect mycelial colonization, enzymatic activity, yield, and fruiting body morphology [1–3, 7, 13]. In addition to yield and BE, substrate properties affect market-relevant morphological and quality traits, pileus diameter, stipe length, coloration (L*, a*, b*), and texture, all of which are critical for consumer acceptance [8, 14]. These features are modulated not only by species genetics but also by environmental and nutritional factors, including substrate structure and composition [6, 15].

Despite the ecological and economic relevance, few studies have systematically assessed the effects of CP particle size on Pleurotus cultivation. Such insights are essential to optimize agro-waste use, promote food security, and develop low-cost biotechnological solutions in coffee-producing regions. Therefore, this study evaluates the impact of three CP particle size classes: raw CP (RCP), medium CP (MCP), and fine CP (FCP), on the growth performance, BE, productivity, morphological parameters, and colorimetric attributes of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus citrinopileatus. The findings aim to support the development of sustainable cultivation systems through effective substrate structuring and valorization of coffee-processing residues.

The study was conducted at the Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (IRAD), Nkolbisson, Yaoundé, Cameroon. Spawn cultures of P. ostreatus and P. citrinopileatus were obtained from the Mushroom Project, Obala-Cameroon. CP, the primary lignocellulosic substrate, was collected from the Food Processing Laboratory of the Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (IRAD), Yaoundé, Cameroon.

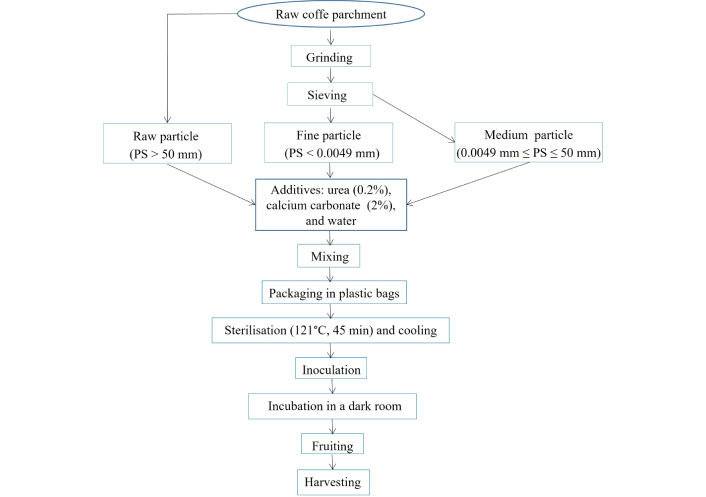

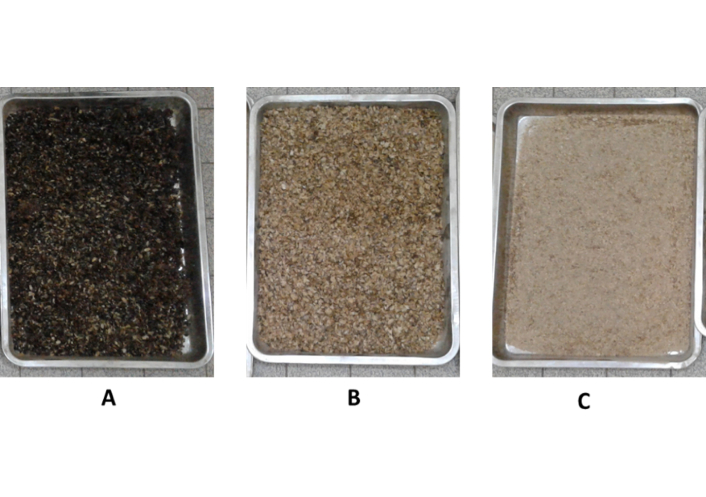

The preparation of CP substrates followed a standardized multi-step protocol to ensure sterility, optimal moisture content, and physical structure conducive to mycelial (P. ostreatus and P. citrinopileatus) colonization and fruiting. The detailed workflow of substrate processing, from initial collection and cleaning to particle size fractionation and sterilization, is illustrated in Figure 1. The process begins with the collection of RCP from the Food Processing Laboratory at IRAD. The material undergoes cleaning thrice with tap water and thoroughly with distilled water to eliminate impurities, followed by drying at 60°C to stabilize its moisture content. The cleaned and dried parchment was then categorized into two groups based on particle size (Figure 2). The first group, designated as RCP, maintains its coarse, unprocessed form with particles exceeding 50 mm. The second group is mechanically ground and sieved to produce two finer particle sizes: MCP, with particles between 0.0049 mm and 50 mm, and FCP, comprising particles smaller than 0.0049 mm. This classification follows standard approaches used in substrate particle size characterization for mushroom cultivation [16, 17]. No additional substrates (e.g., wheat straw) were included, as the purpose of the study was to specifically assess the potential of CP as a sustainable alternative. The unprocessed RCP treatment was considered the internal control for comparative analysis.

Schematic workflow for the preparation and processing of coffee parchment substrates for the cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus citrinopileatus.

Visual representation of coffee parchment particle size categories used as cultivation substrates. (A) raw coffee parchment (RCP); (B) medium coffee parchment (MCP); (C) fine coffee parchment (FCP).

Each substrate type was adjusted to approximately 65% moisture content by adding water in a controlled manner to create optimal conditions for mycelial colonization. The prepared substrates were packed into plastic bags, sterilized at 121°C for 45 minutes, and allowed to cool under aseptic conditions. The cooled substrates are then inoculated with mycelium and incubated at a controlled temperature (25° ± 1°C) and relative humidity (80–85%) to facilitate colonization. This preparation protocol was designed to assess the impact of substrate particle size on the growth, yield, and overall cultivation performance of P. ostreatus and P. citrinopileatus, offering a standardized and scalable method for valorizing coffee industry by-products.

Spawn was prepared using polished paddy rice as the carrier medium. The rice grains are washed thoroughly, soaked overnight, and steamed for 30 to 45 minutes to gelatinize the starches. After cooling, urea (0.2%) and calcium carbonate (CaCO3, 2%), supplied by the Mycology Laboratory of IRAD, were added to adjust the nitrogen content and pH, creating optimal conditions for mycelial growth [18]. The prepared substrate was distributed into sterilized 500 mL glass bottles, which were sealed with cotton plugs and aluminum foil. The glass bottles were sterilized at 121°C for 45 minutes. Once cooled, the substrate was inoculated aseptically with 10% (w/w) actively growing mycelium cultivated on potato dextrose agar (PDA). The inoculated bottles were incubated in darkness at 25° ± 1°C until complete colonization of the substrate by the mycelium.

Four replicates of 2 kg of sterilized CP were distributed equally into four polypropylene bags of 40 cm × 60 cm size. In total, 24 cultivation bags (3 particle size treatments × 2 Pleurotus species × 4 replicates) were used in the experiment. Bags were aseptically inoculated with 20 g of spawn, corresponding to approximately 10% (w/w) of the wet substrate, and mixed thoroughly to facilitate rapid and uniform mycelial growth. The mouths of the bags were tied using a cotton plug and thread. Holes were made in the polypropylene bags for aeration. The bags were incubated in the dark room at 25° ± 1°C with relative humidity maintained at 80–85% using ultrasonic humidifiers. Daily monitoring continued until full substrate colonization.

Upon completion of substrate colonization, the bags were transferred to a fruiting chamber where environmental conditions were carefully controlled. Lighting was provided through diffused daylight supplemented with LED lamps, offering a 12-hour photoperiod at an intensity of 800 to 1,000 lux. Ventilation was facilitated by a passive air exchange system supplemented by mechanical exhaust fans to maintain CO2 concentrations below 1,000 ppm. Mature fruiting bodies were harvested manually to minimize substrate damage. Each cultivation bag produced three successive flushes. Between flushes, the substrates were rehydrated by immersing the bags in clean water for 12 hours.

Pre-fruiting parameters included spawn running time (the period from inoculation to full mycelial colonization), primordial initiation time (the interval from inoculation to the appearance of primordia), and fruiting time (the duration from primordial formation to harvestable maturity). Morphological measurements collected during harvest included the number of pilei, pileus diameter, and stipe length. Productivity was evaluated by measuring the total yield (cumulative fresh weight of harvested mushrooms), BE, and production rate (PR). BE was calculated as the percentage ratio of the fresh weight of mushrooms to the dry weight of the substrate. PR was determined by integrating yield and cropping duration, expressed as a percentage. BE and PR were calculated using Equations 1 and 2 as follows:

Total cultivation days were defined as the number of days from substrate inoculation to the final harvest, including both the incubation (spawn running) and fruiting phases, in line with previous studies [18, 19].

Pileus color was measured using a colorimeter, recording L* (lightness), a* (red-green axis), and b* (yellow-blue axis) values. The color value was estimated using a Hunter’s Lab color analyzer (Hunter Lab scan XE, Reston, VA, USA). In the Hunter colorimeter, the color of a sample is designated by the three dimensions, L*, a*, and b*. This color was measured by placing the aperture of the equipment on the sample with white paper as the reference. The color of the samples was measured after placing the samples in front of the tiniest opening [20]. In order to obtain data reflecting the color of samples, different points were taken into consideration for each sample. All data were collected with three replications.

A completely randomized design (CRD) was employed, comprising three substrate treatments (RCP, MCP, and FCP) for each Pleurotus species. Each treatment was replicated three times. For each replicate, four polypropylene bags (40 cm × 60 cm) were filled with 2 kg of sterilized CP substrate, resulting in a total of 12 bags per treatment and 36 bags per species. Thus, 72 cultivation units were established across the two Pleurotus species, providing sufficient replication for statistical robustness.

All experiments followed a CRD with three replicates per treatment. Data collected included growth parameters (number of pilei, pileus diameter, stipe length, cap number), developmental milestones (spawn running time, primordial initiation, fruiting time), productivity indices (total yield, BE, PR), and quality attributes (color parameters L*, a*, b*). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three replicates. One-way ANOVA assessed the effects of substrate particle size (RCP, MCP, FCP) on all variables. When significant differences were observed (p < 0.05), means were separated using Duncan’s multiple-range test. Values in a column bearing different superscript letters differ significantly at the 5% level.

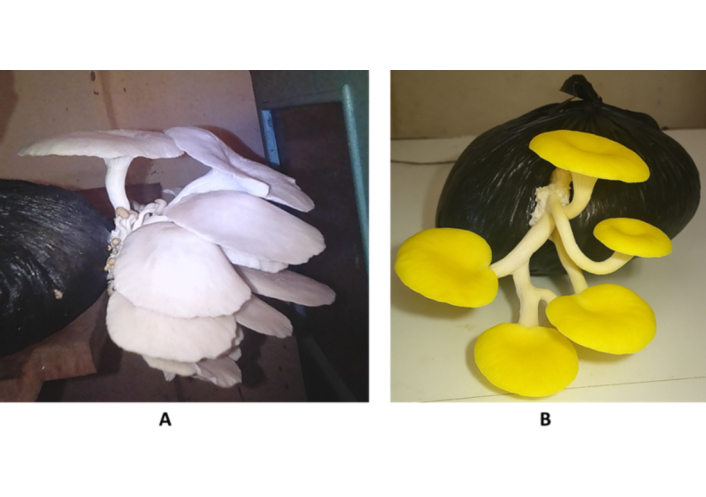

As shown in Figure 3, both P. ostreatus (Figure 3A) and P. citrinopileatus (Figure 3B) formed fruiting bodies on CP substrates, yet differed notably in color, cap curvature, and structural density. P. ostreatus formed compact clusters with overlapping caps, whereas P. citrinopileatus displayed more spaced and bright yellow pilei.

Morphological comparison between Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus citrinopileatus cultivated on coffee parchment substrates under similar conditions. (A) P. ostreatus (white oyster mushroom); (B) P. citrinopileatus (yellow oyster mushroom).

The size of substrate particles significantly influenced the developmental morphology of mushrooms, impacting all assessed characteristics, including pileus number, pileus diameter, and stipe length (Table 1). Medium-sized particles (MCP) consistently yielded the most advantageous outcomes for both fungal species investigated. P. citrinopileatus exhibited the production of 30.00 ± 2.80 pilei, with an average pilei diameter of 8.00 ± 1.50 cm and stipe length of 11.50 ± 1.20 cm. A comparable pattern was observed in P. ostreatus, which demonstrated 28.20 ± 3.12 pilei, an average pilei diameter of 9.50 ± 2.22 cm, and a stipe length of 13.15 ± 1.33 cm. These beneficial effects are attributed to the inherent physical properties of MCP, specifically its balanced porosity, adequate airflow, and effective moisture retention capacity. This confluence of factors creates a conducive environment that promotes robust colonization and consistent fruiting body formation.

Effects of particle size of coffee parchment on growth parameters of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus citrinopileatus.

| Particle size | Species | Number of pileus | Diameter of pileus (cm) | Stipe length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCP | P. ostreatus | 9.55 ± 1.22 c | 5.50 ± 0.00 c | 7.42 ± 0.99 b |

| MCP | P. ostreatus | 28.20 ± 3.12 a | 9.50 ± 2.22 a | 13.15 ± 1.33 a |

| FCP | P. ostreatus | 26.00 ± 1.66 b | 7.80 ± 0.14 a | 8.40 ± 0.22 b |

| RCP | P. citrinopileatus | 11.50 ± 1.50 c | 4.80 ± 0.20 c | 6.80 ± 0.90 c |

| MCP | P. citrinopileatus | 30.00 ± 2.80 a | 8.00 ± 1.50 a | 11.50 ±1.20 a |

| FCP | P. citrinopileatus | 28.00 ± 2.00 b | 7.00 ± 0.25 b | 7.50 ± 0.50 b |

RCP: raw coffee parchment; MCP: medium coffee parchment; FCP: fine coffee parchment. Values are mean ± SD from three replicates. Values in a column with different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) at 5% level of significance using Duncan’s multiple-range test. Repeated superscript letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). SD: standard deviation.

The physical structure of the substrate, especially its particle size, significantly shaped the timing of key developmental stages in both P. ostreatus and P. citrinopileatus (Table 2). The effect was most pronounced during the early colonization and initiation phases.

Spawn running, primordial initiation, and fruiting time of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus citrinopileatus cultivated on coffee parchment of different particle sizes.

| Particle size | Species | Spawn running (days) | Primordial initiation (days) | Fruiting (days after primordia) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCP | P. ostreatus | 17.0 ± 1.0 a | 37.0 ± 1.2 a | 6.0 ± 0.5 a |

| MCP | P. ostreatus | 15.0 ± 0.9 b | 30.0 ± 1.0 b | 6.0 ± 0.4 a |

| FCP | P. ostreatus | 15.0 ± 0.8 b | 30.0 ± 0.9 b | 6.0 ± 0.4 a |

| RCP | P. citrinopileatus | 18.0 ± 1.0 a | 38.5 ± 1.3 a | 6.5 ± 0.5 a |

| MCP | P. citrinopileatus | 16.0 ± 1.1 b | 31.0 ± 1.1 b | 6.2 ± 0.4 a |

| FCP | P. citrinopileatus | 16.0 ± 1.0 b | 31.0 ± 1.0 b | 6.1 ± 0.4 a |

RCP: raw coffee parchment; MCP: medium coffee parchment; FCP: fine coffee parchment. Values are mean ± SD from three replicates. Values in a column with different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) at 5% level of significance using Duncan’s multiple-range test. Repeated superscript letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). SD: standard deviation.

Spawn running was fastest on medium (MCP) and fine (FCP) particles. P. ostreatus completed colonization in 15.0 ± 0.9 and 15.0 ± 0.8 days, respectively, compared to 17.0 ± 1.0 days on raw coarse parchment (RCP). P. citrinopileatus showed the same pattern: 16.0 ± 1.1 days on MCP and 16.0 ± 1.0 days on FCP, but 18.0 ± 1.0 days on RCP. These reductions indicate improved substrate accessibility. Smaller particles offer more contact points, better moisture retention, and consistent oxygenation, conditions favorable to rapid hyphal extension.

Primordial initiation followed a similar trend. On MCP and FCP, primordia emerged by day 30.0–31.0. On RCP, delays were significant: 37.0 for P. ostreatus and 38.5 for P. citrinopileatus. This lag reflects structural limitations, lower porosity, reduced internal aeration, and uneven nutrient diffusion, impeding the metabolic signals that trigger fruiting body formation.

Fruiting time, measured from primordia emergence to harvestable maturity, remained stable across treatments. For both species, values ranged from 6.0 to 6.5 days, with no significant differences. This suggests that once developmental cues are activated, cap maturation depends more on environmental factors than on substrate configuration.

Yields varied sharply with substrate structure. Among all treatments, fine particles (FCP) produced the highest values for both species (Table 3). P. ostreatus yielded 377.2 ± 18.5 g in total; P. citrinopileatus reached 355.0 ± 17.0 g. In both cases, flush 1 contributed most, over 36% of the total, reflecting a robust initial metabolic response. These high outputs are directly linked to better porosity, higher surface-to-volume ratio, and consistent substrate hydration. In contrast, raw particles (RCP) limited performance. P. ostreatus produced just 203.6 ± 12.0 g, while P. citrinopileatus dropped further to 186.5 ± 11.2 g. Both species showed a typical flush pattern: high initial yield, followed by a gradual decline. However, RCP narrowed that first peak and steepened the fall. Likely causes: limited enzyme-substrate contact, lower aeration, and poor moisture diffusion. The structure was too coarse to support sustained mycelial activity.

Flush-wise yield, BE, and production rate (PR) of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus citrinopileatus cultivated on coffee parchment substrates with different particle sizes.

| Particle size | Pleurotus species | Flush 1 (g) | Flush 2 (g) | Flush 3 (g) | Total yield (g) | BE (%) | PR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCP | P. ostreatus | 82.8 ± 10.3 e | 80.0 ± 8.2 c | 40.8 ± 3.5 e | 203.6 ± 12.0 d | 42.2 ± 3.1 d | 93.8 ± 5.2 e |

| MCP | P. ostreatus | 95.0 ± 10.6 c | 59.9 ± 6.9 e | 57.6 ± 4.3 c | 212.5 ± 13.0 c | 45.0 ± 3.4 c | 107.1 ± 5.8 c |

| FCP | P. ostreatus | 138.2 ± 16.7 a | 126.6 ± 13.1 a | 112.4 ± 10.1a | 377.2 ± 18.5 a | 75.2 ± 4.5 a | 156.7 ± 6.5 a |

| RCP | P. citrinopileatus | 76.0 ± 9.5 f | 72.0 ± 7.8 d | 38.5 ± 3.1 f | 186.5 ± 11.2 e | 39.0 ± 2.8 e | 85.0 ± 4.8 f |

| MCP | P. citrinopileatus | 90.0 ± 9.8 d | 58.0 ± 5.9 f | 53.0 ± 4.0 d | 201.0 ± 12.5 d | 43.5 ± 3.0 c | 102.0 ± 5.5 d |

| FCP | P. citrinopileatus | 130.0 ± 15.0 b | 120.0 ± 11.5 b | 105.0 ± 9.5b | 355.0 ± 17.0 b | 72.0 ± 4.0 b | 150.5 ± 6.0 b |

RCP: raw coffee parchment; MCP: medium coffee parchment; FCP: fine coffee parchment. Values are mean ± SD from three replicates. Values in a column with different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) at 5% level of significance using Duncan’s multiple-range test. Repeated superscript letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). SD: standard deviation; BE: biological efficiency.

BE follows the same gradient. On FCP, P. ostreatus achieved 75.2% and P. citrinopileatus reached 72.0%. These values meet or exceed industry thresholds for intensive systems. On RCP, BE dropped to 42.2% and 39.0%, respectively, barely viable for commercial production. Medium particles (MCP) gave intermediate results, confirming that particle refinement enhances enzymatic access and biomass conversion.

PR, which accounts for time, highlighted another advantage. FCP enabled fast, dense output: 156.7% for P. ostreatus, 150.5% for P. citrinopileatus. RCP lagged far behind (93.8% and 85.0%). PR integrates yield with cycle length. Faster colonization and early fruiting, as seen with FCP and MCP, boost daily productivity, a crucial factor in commercial viability.

Between species, P. ostreatus consistently outperformed P. citrinopileatus in total yield, BE, and PR. This trend reflects their greater physiological robustness and broader enzymatic activity. Yet under optimized FCP conditions, P. citrinopileatus approached parity, suggesting strong potential under controlled cultivation.

Color is not just visual, it signals chemical content, physiological state, and market value. In both Pleurotus species, substrate particle size shaped color outcomes in terms of lightness (L*), red-green balance (a*), and yellow-blue intensity (b*) (Table 4).

Color parameters (L*, a*, b*) of fruiting bodies of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus citrinopileatus cultivated on coffee parchment substrates with different particle sizes.

| Particle size | Pleurotus species | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCP | P. ostreatus | 59.96 ± 4.34 a | 10.33 ± 2.56 b | 26.86 ± 3.38 b |

| MCP | P. ostreatus | 41.40 ± 2.53 d | 14.00 ± 1.30 a | 25.06 ± 0.96 b |

| FCP | P. ostreatus | 49.96 ± 4.63 c | 9.00 ± 2.87 c | 24.00 ± 2.77 c |

| RCP | P. citrinopileatus | 57.50 ± 4.00 b | 11.80 ± 2.20 b | 28.50 ± 3.00 a |

| MCP | P. citrinopileatus | 39.80 ± 2.80 d | 15.50 ± 1.50 a | 26.00 ± 1.00 b |

| FCP | P. citrinopileatus | 47.20 ± 4.50 d | 10.50 ± 2.70 b | 25.20 ± 2.50 b |

RCP: raw coffee parchment; MCP: medium coffee parchment; FCP: fine coffee parchment. Values are mean ± SD from three replicates. Values in a column with different superscript letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) at 5% level of significance using Duncan’s multiple-range test. Repeated superscript letters indicate that the means were not significantly different (p > 0.05). SD: standard deviation.

Lightness (L*) dropped markedly on finer substrates. Mushrooms grown on RCP were the lightest: P. ostreatus reached 59.96, P. citrinopileatus 57.50. On MCP, values fell sharply, to 41.40 and 39.80, respectively. This decline suggests higher pigment deposition, possibly due to more intense metabolic activity and moisture retention. Lower L* values often reflect greater phenolic content and antioxidant accumulation. FCP showed intermediate lightness, indicating that partial compaction may still support pigment synthesis, though less efficiently than MCP.

The red-green component (a*) peaked on MCP. P. ostreatus reached 14.00; P. citrinopileatus, 15.50. These high a* values imply strong activation of the phenylpropanoid pathway, likely linked to improved oxygen flow and enzymatic conditions within MCP substrates. On FCP and RCP, red tones faded. Compact substrates limit oxygen; coarse ones disperse it unevenly. In both anthocyanin and phenolic pigment synthesis may drop.

Yellow-blue axis (b*) followed species-specific patterns. P. citrinopileatus showed the highest values overall, especially on RCP (28.50), in line with its inherent golden pileus phenotype. However, b* declined slightly on MCP and more noticeably on FCP, which may be related to reduced flavonoid or carotenoid biosynthesis under altered moisture-oxygen regimes. P. ostreatus maintained stable b* values across all treatments, with no major shifts.

The present study demonstrates that CP, when physically optimized into fine and medium particle sizes, provides a highly suitable substrate for P. ostreatus and P. citrinopileatus. The positive effects observed on mycelial colonization, fruiting dynamics, and BE align with the broader understanding that both the chemical composition and physical architecture of substrates regulate mushroom growth and morphology [21–23]. By focusing on particle size, our work illustrates how a seemingly simple adjustment can translate into measurable improvements in yield and quality, echoing similar outcomes reported for olive mill residues, humic acid-enriched substrates, and other agro-industrial by-products [24–26].

Morphological distinctions between the two Pleurotus species underline the substrate-driven effects. P. ostreatus formed dense, overlapping clusters, while P. citrinopileatus produced lighter, more vivid pilei, a contrast consistent with studies attributing pigmentation and texture to substrate structure and heterogeneity [27–29]. These visual traits are not merely cosmetic. They often correlate with changes in nutritional and antioxidant profiles, as particle size can influence phenolic accumulation and bioactive compound synthesis [8, 27]. In our case, the darker coloration and enhanced redness observed on medium particles resonate with recent reports linking substrate architecture to antioxidant potential, suggesting functional food value [30].

The BE values obtained here, which exceeded 70% on FCP, place CP among the most promising lignocellulosic substrates. Comparable or even lower performances have been reported for wheat straw, sawdust, and other commonly used residues [21, 31, 32]. In contrast, coarse particles reduced efficiency below practical thresholds, confirming that limited surface contact and weak oxygen diffusion constrain fungal metabolism [33, 34]. These findings support the notion that substrate refinement is as critical as chemical supplementation for yield optimization. Furthermore, high efficiency directly enhances economic viability, a key factor for smallholders in tropical regions where mushrooms are both a food and an income source [35, 36].

Quality traits observed in this study reinforce the added value of CP as a substrate. Beyond yield, the influence of particle size extended to coloration, texture, and likely nutritional enrichment. Similar findings have been documented in Pleurotus eryngii and Pleurotus djamor, where agro-industrial residues enhanced mineral content and antioxidant activity [29, 36]. The accumulation of valuable bioactive compounds has been emphasized in recent valorization studies, highlighting how substrate management can elevate mushrooms from staple foods to functional ingredients [8, 27, 37]. Such improvements meet the growing demand for nutritionally enriched foods that address both health and sustainability.

From a broader perspective, our results strengthen the argument for incorporating CP into circular bioeconomy strategies. Coffee processing generates millions of tons of parchment annually, much of which is discarded through burning or landfilling, creating environmental costs. Transforming this residue into mushroom substrate not only mitigates waste but simultaneously produces nutritious food [34, 37, 38]. Comparable approaches have been advanced with spent mushroom substrate (SMS), which, after cultivation, can be valorized into biochar, biogas, compost, and soil improvers [37–41]. This cascading use extends the life cycle of biomass, ensuring that nearly nothing is wasted, and aligns with zero-waste production principles [30, 42].

The environmental benefits are not trivial. Life cycle assessments show that integrating mushroom residues into agroecosystems reduces greenhouse gas emissions, improves soil fertility, and enhances overall resource efficiency [43–45]. For example, SMS-derived biochar has been shown to act both as a carbon sink and a soil conditioner [46], while composted SMS supports seed germination and horticultural growth [47–49]. Together, these cascading applications integrate mushroom cultivation into circular farming systems where outputs of one stage become valuable inputs for another.

At the same time, sustainability narratives must consider social and economic realities. In countries like Tanzania, mushroom cultivation has proven a reliable supplementary income source for rural households [23]. Similar experiences in China and Malaysia confirm that mushrooms can drive rural development and food security when combined with technological dissemination and efficient waste management [27, 50]. For coffee-producing regions in Africa and Asia, embedding CP-based substrates into mushroom production could provide a dual livelihood opportunity: reducing disposal costs for coffee producers and generating income and protein for small farmers.

Our findings also resonate with the challenges posed by climate change. Shifting environmental conditions are altering plant-microbe interactions and require more resilient cultivation systems [51, 52]. By improving resource-use efficiency and lowering dependency on conventional resources, CP-based substrates offer a low-cost adaptation pathway. They diversify local food systems and contribute to resilience, particularly in regions where climatic shocks already undermine staple production.

This study demonstrates that the particle size of CP critically influences the growth dynamics, yield performance, and phenotypic quality of P. ostreatus and P. citrinopileatus. Medium and fine particles enhanced spawn colonization, accelerated primordia initiation, and significantly increased total yield, BE, and PR, especially for P. ostreatus. Improved porosity and moisture dynamics in these substrates likely facilitated enzymatic activity and nutrient diffusion, promoting consistent fruiting. Moreover, colorimetric changes, particularly in L* and a* values, suggest that substrate structure modulates pigment biosynthesis, potentially via stress-induced metabolic pathways. These findings not only confirm the biological value of optimized CP but also underscore its potential as a biotechnological input within circular economy strategies, offering scalable, low-cost alternatives for sustainable mushroom production and agro-waste valorization.

BE: biological efficiency

CP: coffee parchment

CRD: completely randomized design

FCP: fine coffee parchment

MCP: medium coffee parchment

P. citrinopileatus: Pleurotus citrinopileatus

P. ostreatus: Pleurotus ostreatus

PR: production rate

RCP: raw coffee parchment

SMS: spent mushroom substrate

BZZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. EYM: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. MN: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. EBN: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—review & editing. JEGM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

No human participants or animals were involved in this study. All cultivation practices complied with institutional and national guidelines for environmental sustainability and agro-industrial waste management.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

© The Author(s) 2025.

Open Exploration maintains a neutral stance on jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliations and maps. All opinions expressed in this article are the personal views of the author(s) and do not represent the stance of the editorial team or the publisher.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1188

Download: 83

Times Cited: 0